Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Is anti-androgen treatment during adolescence associated with an improved probability of spontaneous conception leading to childbirth in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Early initiation of anti-androgen treatment is associated with an increased probability of childbirth after spontaneous conception among women with PCOS.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

PCOS is the most common endocrinopathy affecting women of reproductive age. Hyperandrogenism and menstrual irregularities associated with PCOS typically emerge in early adolescence. Previous work indicates that diagnosis at an earlier age (<25 years) is associated with higher fecundity compared to a later diagnosis.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

This population-based study utilized five linked Swedish national registries. A total of 15 106 women with PCOS and 73 786 control women were included. Women were followed from when they turned 18 years of age until the end of 2015, leading to a maximum follow-up of 10 years. First childbirth after spontaneous conception was the main outcome, as identified from the Medical Birth Registry.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Participants included all women born between 1987 and 1996 with a diagnosis of PCOS in the Swedish Patient Registry and randomly selected non-PCOS controls (ratio 1:5). Information on anti-androgenic treatment was retrieved from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry with the use of Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) codes. Women with PCOS who were not treated with any anti-androgenic medication were regarded as normo-androgenic, while those treated were regarded as hyperandrogenic. Women were further classified as being mildly hyperandrogenic if they received anti-androgenic combined oral contraceptive (aaCOC) monotherapy, or severely hyperandrogenic if they received other anti-androgens with or without aaCOCs. Early and late users comprised women with PCOS who started anti-androgenic treatment initiated either during adolescence ( 18 years of age) or after adolescence (>18 years), respectively. The probability of first childbirth after spontaneous conception was analyzed with the use of Kaplan–Meier hazard curve. The fecundity rate (FR) and 95% confidence interval for the time to first childbirth that were conceived spontaneously were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression models, with adjustment for obesity, birth year, country of birth and education level.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

The probability of childbirth after spontaneous conception in the PCOS group compared to non-PCOS controls was 11% lower among normo-androgenic (adjusted FR 0.68 (95% CI 0.64–0.72)), and 40% lower among hyperandrogenic women with PCOS (adjusted FR 0.53 (95% CI 0.50–0.57)). FR was lowest among severely hyperandrogenic women with PCOS compared to normo-androgenic women with PCOS (adjusted FR 0.60 (95% CI 0.52–0.69)), followed by mildly hyperandrogenic women with PCOS (adjusted FR 0.84 (95% CI 0.77–0.93)). Compared to early anti-androgenic treatment users, late users exhibited a lower probability of childbirth after spontaneous conception (adjusted FR 0.79 (95% CI 0.68–0.92)).

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

We lacked direct information on the intention to conceive and the androgenic biochemical status of the PCOS participants, applying instead the use of anti-androgenic medications as a proxy of hyperandrogenism. The duration of anti-androgenic treatment utilized is not known, only the age at prescription. Results are not adjusted for BMI, but for obesity diagnosis. The period of follow-up (10 years) was restricted by the need to include only those women for whom data were available on the dispensing of medications during adolescence (born between 1987 and 1996). Women with PCOS who did not seek medical assistance might have been incorrectly classified as not having the disease. Such misclassification would lead to an underestimation of the true association between PCOS and outcomes.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Early initiation of anti-androgen treatment is associated with better spontaneous fertility rate. These findings support the need for future interventional randomized prospective studies investigating critical windows of anti-androgen treatment.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This study was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (18-671), the Swedish Society of Medicine and the Uppsala University Hospital. Evangelia Elenis has, over the past year, received lecture fee from Gedeon Richter outside the submitted work. Inger Sundström Poromaa has, over the past 3 years, received compensation as a consultant and lecturer for Bayer Schering Pharma, MSD, Gedeon Richter, Peptonics and Lundbeck A/S. The other authors declare no competing interests.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

N/A

Keywords: PCOS, fertility, childbirth, anti-androgen, adolescence

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrinopathy affecting women of reproductive age with a reported prevalence ranging from 5 to 25% (March et al., 2010; Rosenfield and Ehrmann, 2016; Wolf et al., 2018). PCOS is characterized by clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism, menstrual irregularities and ultrasonographic polycystic ovarian morphology (Rosenfield and Ehrmann, 2016). Symptoms typically emerge during early adolescence (Driscoll, 2003; Ryan et al., 2018) and may persist into adulthood. The common denominator for PCOS development appears to be ovarian and/or adrenal hyperandrogenism in synergy with tissue-selective insulin-resistant hyperinsulinism (Ibáñez et al., 2017; Witchel et al., 2019). The disorder is multifactorial and heterogeneous, implicating both intrauterine and postnatal environmental factors, as well as endocrinological, genetic and epigenetic factors (Rosenfield and Ehrmann, 2016). PCOS pathogenesis likely results from the combination of a prenatal predisposing factor (referred to as a ‘first hit’) with an activating postnatal factor (referred to as the ‘second hit’) (Rosenfield, 2020). For example, genetically susceptible girls or those exposed to androgen excess in utero develop hyperandrogenism prepubertally through hyperactivation of their hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis; that, in addition to the normal physiological or obesity-related hyperinsulinism during adolescence, potentiates the hyperandrogenic state and accelerates the syndrome’s clinical manifestations and/or aggravates the syndrome’s clinical course (Bremer, 2010). A more recent evolution of this idea suggests that a mismatch between prenatal and postnatal weight gain, resulting in greater hepatovisceral fat, drives accelerated body growth and maturation, which in turn establishes persistent PCOS features (de Zegher et al., 2018).

In population-based studies (Koivunen et al., 2008; West et al., 2014; Persson et al., 2019), we and others have previously demonstrated that women with PCOS, especially those with obesity, need a longer time to achieve childbirth and give birth to a lower number of children compared to non-PCOS counterparts. A novel finding was the fact that PCOS diagnosis at an earlier age (<25 years) was associated with higher fecundity rate (FR) compared to a later diagnosis (Persson et al., 2019). Since symptoms appear to be progressive in women with PCOS, timely interventions that improve hyperandrogenism, either directly or indirectly through lowering insulin levels, have been recommended (Bremer, 2010). Therefore, whether specific interventions, such as pharmacological treatment during a specific therapeutic window, i.e. during adolescence, can decrease androgen actions and mitigate the future adverse effects of PCOS remains unknown.

Clinical and animal-based evidence indicates that long-term anti-androgen therapy can restore impaired reproductive function. Long-term AR blockade is associated with improved testosterone levels and ovulatory function in adult women with PCOS (De Leo et al., 1998; Paradisi et al., 2013), and a restoration of normal steroid hormone feedback to the reproductive axis (Eagleson et al., 2000). In addition, in prenatally androgenized mice that model PCOS in adulthood (Sullivan and Moenter, 2004; Moore et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2015; Silva et al., 2018), anti-androgen therapy restores estrous cyclicity (Sullivan and Moenter, 2004; Silva et al., 2018). In addition, continuous androgen blockade from an ‘adolescent’ period following puberty is associated with improved ovarian morphology and a reversal of brain wiring changes induced by prenatal androgen exposure (Silva et al., 2018).

Therefore, our study hypothesizes that the probability of childbirth after spontaneous conception among PCOS women improves if preceded by anti-androgen therapy during adolescence. The aim of the current study was therefore to explore whether treatment with anti-androgen medications initiated during adolescence is associated with a higher probability of childbirth after spontaneous conception in women with PCOS.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

The study has been approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (Diary number 2017/309). The need for written or oral informed consent for the participating women in our study was weaved since all data received from the Swedish registries were anonymized.

Study design

The current study is part of a larger population-based project performed in Sweden on 45 395 women with PCOS and 217 049 non-PCOS controls. The study design has been previously presented by Persson et al. (2019). In summary, the data were assembled after linkage of five Swedish national registries, by utilizing the unique personal identification number that individuals are assigned at birth or immigration (Ludvigsson et al., 2009). National registries comprise prospectively collected information from all inhabitants residing in the country and are maintained by Swedish government agencies such as the National Board of Health and Welfare and Statistics Sweden. The provided data in the present study arise from the Patient Registry, the Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry, the Medical Birth Registry, the Education Registry and the Total Population Registry (Ludvigsson et al., 2009).

The Swedish Patient Registry comprises nationwide information on visiting dates and given diagnoses on both psychiatric and somatic care recorded during inpatient and outpatient visits. The visits include visits to gynecologists or fertility specialists. After 1997, diagnoses were classified according to the ICD-10 (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, version 10) (Ludvigsson et al., 2011).

The Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry contains information on Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification codes for prescribed and dispensed drugs, substances, brand names, formulations and daily dosages, together with the date of dispensing since 2005.

The Swedish Medical Birth Registry contains information on prenatal, delivery and neonatal care covering practically all births in Sweden since it was established in 1973. Information recorded includes prospectively collected demographic data, such as maternal age, reproductive history and assisted reproduction, and complications during pregnancy, delivery and the neonatal period.

The Swedish Education Registry, founded in 1985, contains data on demographics and educational attainment of the population.

The Total Population Registry, founded in 1968, contains data on life events including birth, death, place of residence and country of birth. It allows for identification of general population controls and estimation of follow-up time.

Exposure

We defined PCOS as presence of the ICD-10 diagnosis of PCOS (E282) or anovulatory infertility (N970) in the Swedish Patient Registry. The PCOS diagnosis during the study period in Sweden was made mainly according to the 2003 Rotterdam criteria for PCOS, but according to National Guidelines, stricter criteria were in use for adolescents. The revised Rotterdam criteria demanded two out of the following three features, that include the following: (i) oligo-/anovulation, (ii) clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism and (iii) polycystic ovarian morphology on ultrasound, together with exclusion of other etiologies (The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-SPCWG, 2004). In adolescence, PCOS diagnosis was made according to the NIH PCOS criteria which required the presence of both clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism and chronic anovulation, after other etiologies were excluded (such as androgen-secreting tumors, Cushing's syndrome and congenital adrenal hyperplasia) (Zawadski and Dunaif, 1992; Rosenfield, 2020). Women diagnosed with anovulatory infertility were also included in our study population based on the fact that 90% of them have PCOS, according to the Rotterdam criteria (Broekmans et al., 2006; Teede et al., 2010).

Outcome

The outcome measure was first childbirth after spontaneous conception which was considered as a proxy for restoration of normal fertility. Information on fertility surgery, ovulation induction, assisted reproduction, IVF and other infertility treatments were recorded at the first antenatal visit by use of check boxes and were retrieved from the Medical Birth Registry. Information on first childbirth was collected and classified as spontaneous conception if no form of assisted reproduction had been recorded. Time to childbirth is estimated in years from the time a participant turned 18 until the year of first childbirth or the end of the follow-up period.

Study population

The initial population included women born between 1971 and 1997 according to the presence or absence of PCOS or anovulatory infertility diagnosis (Persson et al., 2019). The control group comprised five control individuals per each woman with PCOS, matched by year of birth and residential area, randomly chosen from the Total Population Registry. All women of the study or control group with hyperprolactinemia (E221), congenital adrenal hyperplasia (E25), premature ovarian insufficiency (E283) or Turner syndrome (Q96) were excluded from the population. Lastly, women with one or more prior births before the first recorded birth in the Medical Birth Registry were also excluded.

Due to limitations in data availability from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry (i.e. registry founded in 2005), we further restricted our population to women with access to data regarding the dispensing of medications during adolescence, i.e. born between 1987 and 1996. Since the aim of the study was to explore the incidence of the outcome occurring after the intervention (definition follows), all participants with births registered before 18 years of age were excluded from the population (Morgan, 2019). In the end, 15 106 women with PCOS and 73 786 control women were eligible for inclusion in the study.

Intervention

The intervention of interest regarded the early use of commonly prescribed anti-androgenic treatment (Bremer, 2010; Ibáñez et al., 2017; Witchel et al., 2019) comprising certain combined oral contraceptives (COCs) and/or other anti-androgens (detailed description follows). Anti-androgenic medications were promoted in adolescents and adults with PCOS and hirsutism during the study period, based on Swedish National Guidelines (Swedish Medical Products Agency (Läkemedelsverket), 2014). Notably, this is no longer the case (Teede et al., 2018). Information on anti-androgenic treatment was retrieved from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Registry with the use of ATC codes. The medications of interest included the following: (i) selected COCs advocated against hyperandrogenism by the Swedish contraceptive policy guidelines (referred to as anti-androgenic COCs in the study or aaCOCs) (Swedish Medical Products Agency (Läkemedelsverket), 2014), such as ethinylestradiol (EE) and dienogest (G03AA16), EE and drosperinone (G03AA12), EE and desogestrel (G03AA09); and/or (ii) prescription of other anti-androgenic medications such as spironolactone (C03DA01), finasteride and dutasteride (G04CB), finasteride and eflornithine (D11AX), flutamide and bikalutamide (L02BB), EE and cyproterone acetate (G03HB01). Women classified as treated received at least two filled prescriptions of any of the medications listed above during or after adolescence.

Due to the ‘registry-based’ study design, data on the clinical or biochemical androgen status of PCOS women (Lizneva et al., 2016) are lacking. Instead, the prescription of anti-androgenic medications was used as a proxy for evidence of hyperandrogenism. Women with PCOS who were not treated with any anti-androgenic medication were regarded as normo-androgenic, while those treated were regarded as hyperandrogenic. We further classified hyperandrogenic women as being mildly hyperandrogenic if they received aaCOC monotherapy, or severely hyperandrogenic if they received other anti-androgens with or without aaCOCs. Early anti-androgenic treatment was defined as during adolescence (18 years of age) (referred to as early users) or after adolescence (>18 years) (referred to as late users). A flow diagram of the study design is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Covariates

Data on obesity were retrieved from the Swedish Patient Registry and concerned the presence of the ICD-10 diagnosis on obesity (E66) (i.e. BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Data on year and country of birth, as well as maternal education in 2017, were retrieved from the Total Population Registry and the Education Registry, respectively. Maternal country of birth was categorized as Nordic (including Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Norway and Iceland), European (excluding Nordic countries), Middle Eastern, South Asian (India, Bangladesh and Pakistan), African and remaining countries. Maternal education was categorized as <12 or ≥12 years.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA, Version 26). The probability of first childbirth after spontaneous conception was analyzed with the use of Kaplan–Meier hazard curve. Using the Cox proportional hazards regression test with time-dependent covariates, we ensured that the assumption of proportional hazards was fulfilled. The average time to childbirth, calculated only among women with the end-point event, was presented with both mean and median calculated values, and statistical comparisons were made with the use of the log-rank test. When a participant reached the end of the observation period, censoring was applied. We used the landmark analysis (Morgan, 2019), restricting the results to those women still at risk at the landmark time (i.e. 18 years of age) and ignoring all those with the event prior to the landmark. In order to avoid bias, the landmark was chosen based on clinical relevance, prior to the data analysis. We estimated the FR and 95% confidence interval for the time to first childbirth after spontaneous conception, using Cox proportional hazards regression models. FR below 1.0 (< 1.0) denotes reduced fecundity for the group of interest compared to the reference group. The Cox regression analyses were adjusted for obesity, birth year, country of birth and education level. The Cox regression analyses concern comparisons between the study and control group, as well different PCOS subcategories (normo-androgenic, mildly hyperandrogenic or severely hyperandrogenic women, and early users or late users). A subgroup analysis among hyperandrogenic PCOS women in relation to the timing of treatment initiation (early versus late) was performed after stratification on the severity of hyperandrogenism. Lastly, sensitivity analyses were performed restricting the study population to (i) women with PCOS diagnosis only (ICD-10 code E282), (ii) women with PCOS of Nordic origin only, as well as (iii) women with PCOS on COCs.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

The background characteristics of the total population are presented in Table I. Greater proportions of women originating from Europe, the Middle East and South Asia, as well as women with lower education level (below 12 years) were observed in the PCOS study group. Furthermore, the rate of obesity was higher in women with PCOS compared to the non-PCOS controls (13.3% versus 3.4%, P < 0.001). Women with PCOS also had a significantly lower incidence of childbirth after spontaneous conception (14.2% versus 18.9%, P < 0.001) compared to the non-PCOS controls. More than half of the women with PCOS (n = 7 949, 52.6%) had been dispensed anti-androgenic medications. The most commonly prescribed anti-androgenic medications in women with PCOS were aaCOCs, either as monotherapy (n = 5 456, 36.1%) or in combination with plain anti-androgens (n = 1 533, 10.1%). Plain anti-androgen monotherapy was less common (n = 960, 6.4%). The medications were most commonly prescribed after adolescence (late users) (71.4%) compared to during adolescence (early users) (28.6%). A higher proportion of normo-androgenic women with PCOS gave birth following a spontaneous conception compared to hyperandrogenic women with PCOS (17.1% versus 11.6%, respectively) (Table II).

Table I.

Background characteristics of the total population (N = 88 892) including women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

| Women with PCOS (n = 15 106) | Non-PCOS controls (n = 73 786) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity | <0.001 | ||

| No | 13 102 (86.7) | 71 302 (96.6) | |

| Yes | 2004 (13.3) | 2484 (3.4) | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

| <12 years | 7701 (51.7) | 35 812 (49.6) | |

| 12 years | 7181 (48.3) | 36 368 (50.4) | |

| Missing data (1830, 2.1) | |||

| Country of Birth | <0.001 | ||

| Nordic countries | 11 500 (76.1) | 61 318 (83.1) | |

| Europe | 1087 (7.2) | 4526 (6.1) | |

| Middle East | 1425 (9.4) | 2872 (3.9) | |

| South Asia | 260 (1.7) | 540 (0.7) | |

| Africa | 263 (1.7) | 1706 (2.4) | |

| Remaining countries | 571 (3.8) | 2824 (3.8) | |

| Birth year | NS | ||

| 1987 | 2361 (15.6) | 11 401 (15.5) | |

| 1988 | 2210 (14.6) | 10 738 (14.6) | |

| 1989 | 2084 (13.8) | 10 153 (13.8) | |

| 1990 | 1951 (12.9) | 9523 (12.9) | |

| 1991 | 1704 (11.3) | 8304 (11.3) | |

| 1992 | 1408 (9.3) | 6936 (9.4) | |

| 1993 | 1141 (7.6) | 5642 (7.6) | |

| 1994 | 940 (6.2) | 4648 (6.3) | |

| 1995 | 760 (5.0) | 3745 (5.1) | |

| 1996 | 547 (3.6) | 2696 (3.7) | |

| First spontaneous childbirth | <0.001 | ||

| No | 12 961 (85.8) | 59 856 (81.1) | |

| Yes | 2145 (14.2) | 13 930 (18.9) |

Data are presented as n (%).

Table II.

Treatment characteristics of the study group of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) women.

| Women with PCOS (n = 15 106) | |

|---|---|

| Hyperandrogenic status | |

| Normo-androgenic PCOS women | 7157 (47.4%) |

| Hyperandrogenic PCOS women | 7949 (52.6%) |

| Combinations of aa medications used | |

| No anti-androgenic medications | 7157 (47.4%) |

| aaCOCs only | 5456 (36.1%) |

| aaCOCs and plain anti-androgens combined | 1533 (10.1%) |

| Plain anti-androgens only | 960 (6.4%) |

| Hyperandrogenic status | |

| Normo-androgenic PCOS women | 7157 (47.4%) |

| Mildly hyperandrogenic PCOS women | 5456 (36.1%) |

| Severely hyperandrogenic PCOS women | 2493 (16.5%) |

| Timing of any anti-androgenic medications** | |

| Early users | 2276 (15.1%) |

| Late users | 5673 (37.6%) |

| Non users | 7157 (47.4%) |

| aaCOCs | |

| Early users | 1939 (12.8%) |

| Late users | 5050 (33.4%) |

| Non users | 8117 (53.7%) |

| Plain anti-androgens | |

| Early users | 514 (3.4%) |

| Late users | 1979 (13.1%) |

| Non users | 12 613 (83.5%) |

Early and late users comprise PCOS women with anti-androgenic treatment initiated up to or above 18 years of age, respectively.

aaCOCs, anti-androgenic combined oral contraceptives.

Data are presented as n (%).

Non-PCOS controls have a greater probability of spontaneous childbirth after spontaneous conception than normo-androgenic and hyperandrogenic women with PCOS

In comparison with non-PCOS controls, the probability of childbirth after spontaneous conception was 11% lower among normo-androgenic women with PCOS, and 40% lower among hyperandrogenic women with PCOS (unadjusted FR 0.89 (95% CI 0.84–0.95) and unadjusted FR 0.60 (95% CI 0.56–0.64), respectively). The estimates remained unchanged after adjustment for obesity, year of birth, country of birth and education level (Fig. 1). The calculated mean and median time to childbirth after spontaneous conception were shortest in normo-androgenic women with PCOS (mean 5.51 years, SD 2.35/median 6.0 years, IQR 3.0) compared to non-PCOS controls (mean 5.60 years, SD 2.37/median 6.0 years, IQR 3.0) and hyperandrogenic women with PCOS (mean 5.84 years, SD 2.34/median 6.0 years, IQR 4.0) (P = 0.005).

Figure 1.

Probability of first childbirth by spontaneous conception in the entire population. Cum, cumulative; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome.

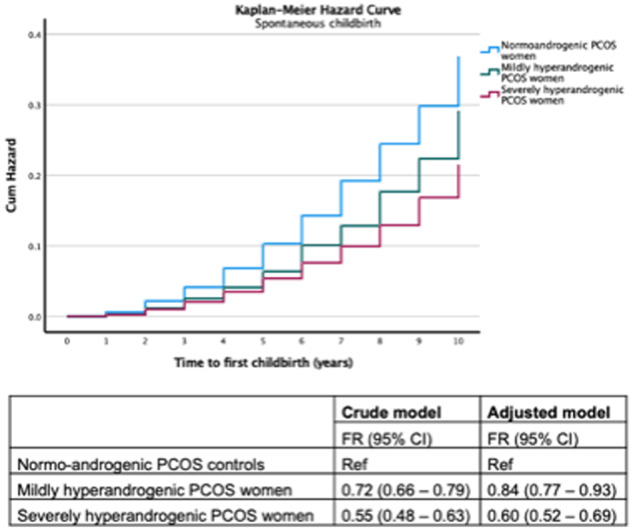

Severely hyperandrogenic women with PCOS have a lower probability of childbirth after spontaneous conception compared to mildly hyperandrogenic women with PCOS

Compared to normo-androgenic women with PCOS, we observed that the FR was lowest among severely hyperandrogenic women with PCOS (unadjusted FR 0.58 (95% CI 0.51–0.66)), followed by mildly hyperandrogenic women with PCOS (unadjusted FR 0.72 (95% CI 0.65–0.79)) (Fig. 2). The above estimates did not change after adjustment for obesity, year of birth, country of birth and education level. Mean and median time to first childbirth after spontaneous conception was significantly longer in severely hyperandrogenic women with PCOS (mean 5.87 years, SD 2.36/median 6.0 years, IQR 4.0) compared to mildly hyperandrogenic women with PCOS (mean 5.83 years, SD 2.34/median 6.0 years, IQR 4.0) and normo-androgenic women with PCOS (mean 5.51 years, SD 2.35/median 6.0 years, IQR 3.0) (P = 0.007).

Figure 2.

Probability of first childbirth by spontaneous conception among polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) women in relation to the anti-androgenic potential of medication used.

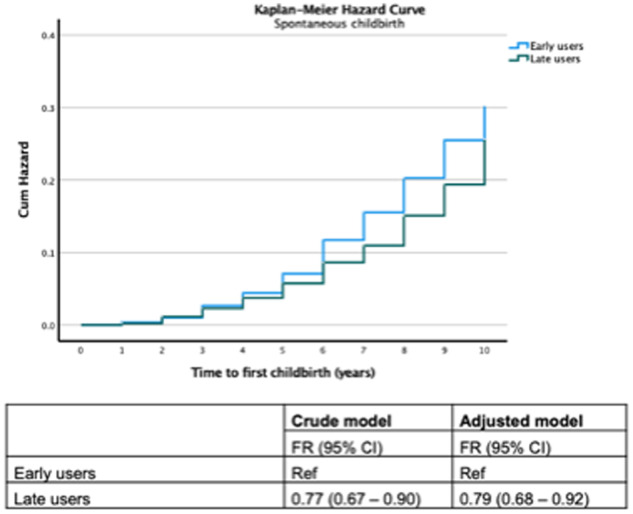

Early anti-androgenic treatment in women with PCOS is associated with a higher probability of childbirth after spontaneous conception compared to late anti-androgenic treatment

In comparison with women with PCOS who started anti-androgenic treatment in adolescence, late users exhibited a lower FR (unadjusted FR 0.78 (95% CI 0.67–0.90)) with similar estimates even after adjustment (Fig. 3). Mean and median time to first childbirth after spontaneous conception was shorter in hyperandrogenic women with PCOS who started anti-androgenic treatment early (mean 5.40 years, SD 2.15/median 6.0 years, IQR 3.0) compared to women who started late (mean 6.00 years, SD 2.39/median 6.0 years, IQR 4.0) (P = 0.001). Similar results regarding the effect of early or late treatment initiation could be seen even after stratifying the PCOS population on the severity of hyperandrogenism. Early treatment was especially effective among mildly hyperandrogenic PCOS women (unadjusted FR 0.72 (95% CI 0.61–0.86)), and to a lesser degree in severely hyperandrogenic women (unadjusted FR 0.89 (95% CI 0.67–1.19)).

Figure 3.

Probability of first childbirth by spontaneous conception among hyperandrogenic polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) women in relation to the timing of medication used.

Numbers at risk over time in each model are shown in Supplementary Table SI.

Sensitivity analyses regarding all three models/scenarios presented above were performed among women with PCOS diagnosis (ICD-10 code E282) (i.e. without taking into account whether women were also diagnosed with anovulatory infertility) as well as PCOS women of Nordic origin or women on aaCOCs, and none of them altered the estimates presented previously.

Discussion

Main findings

As expected, non-PCOS controls had a higher probability of childbirth after spontaneous conception than normo-androgenic and hyperandrogenic PCOS women. Among women with PCOS, severe hyperandrogenism (characterized by the higher anti-androgenic potential of treatment) was associated with lower FR, while the initiation of anti-androgenic treatment at an earlier age was associated with ameliorated severity of PCOS-related subfertility.

The need for anti-androgenic treatment likely corresponds to individuals with more severe hyperandrogenic clinical manifestations. It is therefore not surprising that PCOS-diagnosed women who received anti-androgen treatment (at some point in life) required more time to first childbirth after a spontaneous conception and had a lower FR in comparison with non-PCOS controls and normo-androgenic women with PCOS. Initiation of anti-androgenic treatment at an earlier stage (i.e. during adolescence rather than later in life) suggests early awareness of PCOS, which, in turn, may affect reproductive choices and family planning. However, we consider anti-androgenic treatment at an earlier age as an unlikely marker of a deliberate attempt at achieving pregnancy since anti-androgenic drugs either are contraceptives or are teratogenic (Eibs et al., 1982; Kim and Del Rosso, 2012). One could therefore wonder whether the higher FR among early users observed in our study could be attributed to a long-lasting pharmacological effect of the anti-androgens, extending even after the period of use.

Comparison to other studies

While there is a paucity of clinical data on the long-term impact of anti-androgen treatment of women with PCOS, the present findings are in agreement with what is reported. Long-term androgen receptor blockade is associated with improved testosterone levels and ovulatory function in adult women with PCOS (De Leo et al., 1998; Paradisi et al., 2013). Additionally, long-term anti-androgen therapy is reported to restore normal steroid hormone feedback to the reproductive axis (Eagleson et al., 2000). However, there is a lack of prospective clinical data reporting the FR of PCOS women taking anti-androgens.

Anti-androgen administration in animals that mimic the PCOS phenotype following prenatal exposure to androgen excess can restore normal estrous cyclicity (Sullivan and Moenter, 2004; Silva et al., 2018). Endogenous hyperandrogenism increases in this model at 40 days, shortly after pubertal onset (Silva et al., 2018). Flutamide treatment from 40 to 60 days rescues estrous cyclicity, improves ovarian morphology and also reverses aberrant GABA wiring in the brain associated with impaired steroid hormone feedback of PCOS (Moore et al., 2015; Silva et al., 2018). It remains to be determined whether these improvements are the same if treatment is delayed beyond this ‘adolescent’ period.

Pathophysiology

These data suggest that by ‘hindering or impairing’ the ‘second hit’ of androgen action that develops at puberty, particularly through early pharmacological intervention, PCOS-related subfertility may be attenuated. The critical site of androgen action in the development and maintenance of clinical PCOS features remains unclear, but several lines of evidence in preclinical animal models point toward the importance of androgen signaling in the female brain (Coutinho and Kauffman, 2019; Ruddenklau and Campbell, 2019). Given the multifactorial nature of PCOS pathogenesis, early interventions of ‘second hits’ are likely to be most effective when guided by known predisposing contributors, or ‘first hits’(Ibáñez et al., 2017).

One possibility in women with PCOS is that the ‘first hit’ (i.e. genetic predisposition, prenatal androgen excess) shapes hypothalamic circuitry in a particular way that establishes the emergence of PCOS features, including aberrant gonadotrophin regulation and hyperandrogenism, and that a ‘second hit’ is then required to maintain those pathophysiological changes. Of interest, changes in GABA brain wiring and activity associated with prenatal androgen excess in rodent models develop prior to hyperandrogenism and PCOS-like features (Berg et al., 2018; Silva et al., 2018). However, these ‘programmed’ changes in neuroendocrine circuits can be rewired with androgen blockade (Silva et al., 2018).

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of the study is its large sample size which enabled us to perform analyses of rare outcomes, as well as stratify according to different variables. Furthermore, information was retrieved from highly valid registries and evolved over a period of 10 years.

Unfortunately, we lacked information on smoking or possible comorbidities of the study participants. In addition, since the BMI of study participants is not available unless they give birth, we employed the presence of obesity diagnosis instead. While the dependence on ICD diagnosis will likely under-report obesity rates among this cohort, this enabled us to account for obesity in the adjusted Cox regression models to overcome the limitation of not having access to BMI data. Furthermore, it would have been desirable to have accurate and direct information on the androgenic biochemical status of the PCOS participants; we employed instead use of anti-androgenic medications as a proxy of hyperandrogenism. Moreover, we do not know the duration of anti-androgenic treatment utilized or the number of study participants that actively attempted a pregnancy during the study period. In addition, we did not censor for death or immigration, and all participants were followed up until the ending date. Lastly, it has been demonstrated that foreign-born families residing in Sweden utilize healthcare services with increased frequency compared to natives, increasing the chance that a PCOS diagnosis is posed and thereby treatment initiated at an earlier stage (Swedish Public Health Agency (Folkhälsomyndigheten), 2019). Furthermore, women with a foreign background attempt pregnancy at an earlier age compared to Swedish-born women (National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen), 2020). Both observations could indicate that the differences noted may be due to social reasons and not only biological reasons. However, our results remained unaltered, even after the sensitivity analysis performed restricting our population to women of Nordic origin, strengthening the biological component of the intervention.

Lastly, women with PCOS, especially those with more severe clinical features of the syndrome such as the obese and/or hyperandrogenic women, often report distorted self-perceived body image which in turn affects their sexuality and social well-being (Alur-Gupta et al., 2019; Kogure et al., 2019). Whether body dissatisfaction results in a deliberate delay in childbearing is unknown and difficult to tease apart from the PCOS-associated impairments in the reproductive axis. The possibility of bias cannot therefore be entirely ruled out, but it is deemed nevertheless to be limited since the effect of hyperandrogenism on childbirth is not attenuated after adjustment for obesity.

Conclusions

Our study findings suggest that early initiation of anti-androgenic treatment during adolescence could promote the prevention of fertility-related morbidity among PCOS women. Although reproductive endocrinologists should exercise caution in assigning PCOS diagnosis prematurely, they should however not stall early treatment initiation when indicated. These findings support the need for future interventional randomized prospective studies investigating critical windows of anti-androgen treatment.

Data availability

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available and cannot be uploaded at any website due to the risk of compromising the individual privacy of participants.

Authors’ roles

All authors have equally contributed to the design of the study, data collection, interpretation of the results, drafting of the manuscript, as well as critical revision of the final version submitted.

Funding

This study was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (18-671), the Swedish Society of Medicine and the Uppsala University Hospital.

Conflict of interest

Evangelia Elenis has over the past year received lecture fee from Gedeon Richter outside the submitted work. Inger Sundström Poromaa has over the past three years received compensation as a consultant and lecturer for Bayer Schering Pharma, MSD, Gedeon Richter, Peptonics and Lundbeck A/S. The other authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Supplementary Material

References

- Alur-Gupta S, Chemerinski A, Liu C, Lipson J, Allison K, Sammel MD, Dokras A.. Body-image distress is increased in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and mediates depression and anxiety. Fertil Steril 2019;112:930–938.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg T, Silveira MA, Moenter SM.. Prepubertal development of GABAergic transmission to gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons and postsynaptic response are altered by prenatal androgenization. J Neurosci 2018;38:2283–2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer AA. Polycystic ovary syndrome in the pediatric population. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2010;8:375–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekmans FJ, Knauff EA, Valkenburg O, Laven JS, Eijkemans MJ, Fauser BC.. PCOS according to the Rotterdam consensus criteria: change in prevalence among WHO-II anovulation and association with metabolic factors. BJOG 2006;113:1210–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho EA, Kauffman AS.. The role of the brain in the pathogenesis and physiology of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Med Sci (Basel) 2019;7:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo V, Lanzetta D, D’Antona D, la Marca A, Morgante G.. Hormonal effects of flutamide in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zegher F, Lopez-Bermejo A, Ibanez L.. Central obesity, faster maturation, and ‘PCOS’ in girls. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2018;29:815–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll DA. Polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescence. Semin Reprod Med 2003;21:301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagleson CA, Gingrich MB, Pastor CL, Arora TK, Burt CM, Evans WS, Marshall JC.. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: evidence that flutamide restores sensitivity of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator to inhibition by estradiol and progesterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:4047–4052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eibs HG, Spielmann H, Jacob-Muller U, Klose J.. Teratogenic effects of cyproterone acetate and medroxyprogesterone treatment during the pre- and postimplantation period of mouse embryos. II. Cyproterone acetate and medroxyprogesterone acetate treatment before implantation in vivo and in vitro. Teratology 1982;25:291–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez L, Oberfield SE, Witchel S, Auchus RJ, Chang RJ, Codner E, Dabadghao P, Darendeliler F, Elbarbary NS, Gambineri A. et al. An international consortium update: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of polycystic ovarian syndrome in adolescence. Horm Res Paediatr 2017;88:371–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ.. Oral spironolactone in post-teenage female patients with acne vulgaris: practical considerations for the clinician based on current data and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2012;5:37–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogure GS, Ribeiro VB, Lopes IP, Furtado CLM, Kodato S, Silva de Sa MF, Ferriani RA, Lara L, Maria Dos Reis R.. Body image and its relationships with sexual functioning, anxiety, and depression in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Affect Disord 2019;253:385–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivunen R, Pouta A, Franks S, Martikainen H, Sovio U, Hartikainen AL, McCarthy MI, Ruokonen A, Bloigu A, Jarvelin MR.. Fecundability and spontaneous abortions in women with self-reported oligo-amenorrhea and/or hirsutism: Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966 Study . Hum Reprod 2008;23:2134–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizneva D, Suturina L, Walker W, Brakta S, Gavrilova-Jordan L, Azziz R.. Criteria, prevalence, and phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2016;106:6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C, Heurgren M, Olausson PO.. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A.. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March WA, Moore VM, Willson KJ, Phillips DI, Norman RJ, Davies MJ.. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod 2010;25:544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AM, Prescott M, Campbell RE.. Estradiol negative and positive feedback in a prenatal androgen-induced mouse model of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Endocrinology 2013;154:796–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AM, Prescott M, Marshall CJ, Yip SH, Campbell RE.. Enhancement of a robust arcuate GABAergic input to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in a model of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112:596–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CJ. Landmark analysis: a primer. J Nucl Cardiol 2019;26:391–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Board of Health and Welfare [Socialstyrelsen]. Statistics on pregnancies, childbirths and infants born 2018. [Statistik om graviditeter, förlossningar och nyfödda barn 2018], 2020.

- Paradisi R, Fabbri R, Battaglia C, Venturoli S.. Ovulatory effects of flutamide in the polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol 2013;29:391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson S, Elenis E, Turkmen S, Kramer MS, Yong EL, Sundstrom-Poromaa I.. Fecundity among women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)-a population-based study. Hum Reprod 2019;34:2052–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield RL. Current concepts of polycystic ovary syndrome pathogenesis. Curr Opin Pediatr 2020;32:698–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield RL, Ehrmann DA.. The pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): the hypothesis of PCOS as functional ovarian hyperandrogenism revisited. Endocr Rev 2016;37:467–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddenklau A, Campbell RE.. Neuroendocrine impairments of polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocrinology 2019;160:2230–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan GE, Malik S, Mellon PL.. Antiandrogen treatment ameliorates reproductive and metabolic phenotypes in the letrozole-induced mouse model of PCOS. Endocrinology 2018;159:1734–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva MS, Prescott M, Campbell RE.. Ontogeny and reversal of brain circuit abnormalities in a preclinical model of PCOS. JCI Insight 2018;3:e99405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan SD, Moenter SM.. Prenatal androgens alter GABAergic drive to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: implications for a common fertility disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:7129–7134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Medical Products Agency [Läkemedelsverket]. Constraception – treatment recommendations. [Antikonception – behandlingsrekommendation]. 2014;25:14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Public Health Agency [Folkhälsomyndigheten]. Health, socioeconomic, and lifestyle factors among foreign born individuals in Sweden. [Hälsa hos personer som är utrikes födda – skillnader i hälsa utifrån födelseland. 2019.

- Teede H, Deeks A, Moran L.. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a complex condition with psychological, reproductive and metabolic manifestations that impacts on health across the lifespan. BMC Med 2010;8:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, Dokras A, Laven J, Moran L, Piltonen T, Norman RJ, Andersen M, Azziz R, International PCOS Network et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2018;33:1602–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-SPCWG. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2004;81:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West S, Vahasarja M, Bloigu A, Pouta A, Franks S, Hartikainen AL, Jarvelin MR, Corbett S, Vaarasmaki M, Morin-Papunen L.. The impact of self-reported oligo-amenorrhea and hirsutism on fertility and lifetime reproductive success: results from the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966. Hum Reprod 2014;29:628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witchel SF, Oberfield SE, Pena AS.. Polycystic ovary syndrome: pathophysiology, presentation, and treatment with emphasis on adolescent girls. J Endocr Soc 2019;3:1545–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf WM, Wattick RA, Kinkade ON, Olfert MD.. Geographical prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome as determined by region and race/ethnicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawadski J, Dunaif A.. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome; towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens J, Haseltine F (eds). Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Boston, MA: Black-Well Scientific, 1992, 377–384. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available and cannot be uploaded at any website due to the risk of compromising the individual privacy of participants.