Abstract

Purpose

To provide evidence-based recommendations to practicing physicians and others on the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma.

Methods

ASCO convened an Expert Panel of medical oncology, thoracic surgery, radiation oncology, pulmonary, pathology, imaging, and advocacy experts to conduct a literature search, which included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and prospective and retrospective comparative observational studies published from 1990 through 2017. Outcomes of interest included survival, disease-free or recurrence-free survival, and quality of life. Expert Panel members used available evidence and informal consensus to develop evidence-based guideline recommendations.

Results

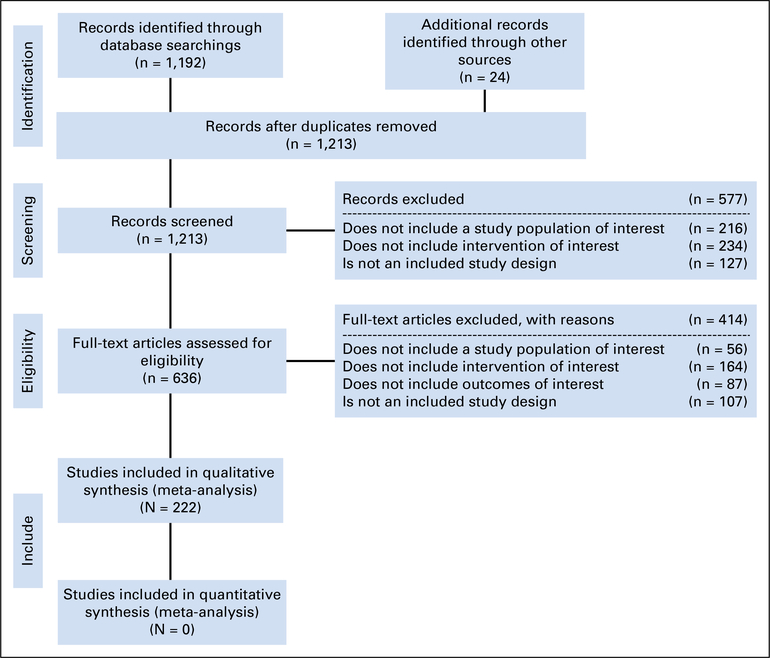

The literature search identified 222 relevant studies to inform the evidence base for this guideline.

Recommendations

Evidence-based recommendations were developed for diagnosis, staging, chemotherapy, surgical cytoreduction, radiation therapy, and multimodality therapy in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma.

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this guideline is to provide recommendations for the management of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM), an aggressive tumor with a poor prognosis. In the United States, about 3,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. The median overall survival of patients with advanced surgically unresectable disease is about 12 months.1 Given the rarity of this malignancy, there have been few large randomized trials, especially for surgical management of this disease. In general, a minority of patients are candidates for surgical resection at time of presentation; thus, the mainstay of treatment is systemic chemotherapy. For patients who are surgical candidates, surgery is performed as part of multimodality therapy involving chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy. The aim of this clinical practice guideline is to outline the management of patients with MPM, including diagnosis, pathologic confirmation, and surgical and medical management.

GUIDELINE QUESTIONS

This clinical practice guideline addresses five overarching clinical questions: (1) What is the optimal approach to obtain an accurate diagnosis of mesothelioma? (2) What initial assessment is recommended before initiating any therapy for mesothelioma? (3) What is the appropriate first- and second-line systemic treatment of patients with mesothelioma? (4) What is the appropriate role of surgical cytoreduction in the management of mesothelioma? (5) When should radiation be recommended for mesothelioma?

METHODS

Guideline Development Process

This systematic review-based guideline product was developed by a multidisciplinary Expert Panel, which included a patient representative and ASCO guidelines staff with health research methodology expertise (Appendix Table A1, online only). The Expert Panel, co-chaired by H.L.K and R.H., met via teleconference and/or webinar and corresponded through e-mail. Based upon the consideration of the evidence, the authors were asked to contribute to the development of the guideline, provide critical review, and finalize the guideline recommendations. Members of the Expert Panel were responsible for reviewing and approving the penultimate version of the guideline, which was then circulated for external review and submitted to Journal of Clinical Oncology for editorial review and consideration for publication. All ASCO guidelines are ultimately reviewed and approved by the Expert Panel and the ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Committee prior to publication. All funding for the administration of the project was provided by ASCO.

The recommendations were developed by an Expert Panel with multidisciplinary representation using a systematic review (1990 to 2016), which included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective and retrospective comparative observational studies, and clinical experience. Articles were selected for inclusion in the systematic review of the evidence based on the following criteria:

Population: Patients diagnosed with MPM.

Interventions that focused on diagnosis, staging, imaging, chemotherapy, radiation, and surgical cytoreduction of patients with MPM.

Study designs included were systematic reviews, meta-analyses, RCTs, and prospective and retrospective comparative observational studies. Some phase II studies were included to address some of the clinical questions for chemotherapy management.

A minimum sample size of 20.

Articles were excluded from the systematic review if they were meeting abstracts not subsequently published in peer-reviewed journals; editorials, commentaries, letters, news articles, case reports, or narrative reviews; or published in a non-English language.

The guideline recommendations are crafted, in part, using the Guidelines Into Decision Support methodology and accompanying BRIDGE-Wiz software.2 In addition, a guideline implementability review is conducted. Based on the implementability review, revisions were made to the draft to clarify recommended actions for clinical practice. Ratings for the type and strength of recommendation, evidence, and potential bias are provided with each recommendation.

Detailed information about the methods used to develop this guideline is available in the Methodology Supplement at www.asco.org/thoracic-cancer-guidelines, including an overview (eg, panel composition, development process, and revision dates), literature search and data extraction, the recommendation development process (Guidelines Into Decision Support and BRIDGE-Wiz), and quality assessment.

The ASCO Expert Panel and guidelines staff will work with co-chairs to keep abreast of any substantive updates to the guideline. Based on formal review of the emerging literature, ASCO will determine the need to update. The Methodology Supplement (available at www.asco.org/thoracic-cancer-guidelines) provides additional information about the Signals approach.

This is the most recent information as of the publication date. Visit the ASCO Guidelines Wiki at www.asco.org/guidelineswiki to submit new evidence.

In some selected cases where evidence is lacking, but there was a high level of agreement among the Expert Panel, informal consensus is used (as noted with the Recommendations).

Guideline Disclaimer

The Clinical Practice Guidelines and other guidance published herein are provided by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Inc. (ASCO) to assist providers in clinical decision-making. The information herein should not be relied upon as being complete or accurate, nor should it be considered as inclusive of all proper treatments or methods of care or as a statement of the standard of care. With the rapid development of scientific knowledge, new evidence may emerge between the time information is developed and when it is published or read. The information is not continually updated and may not reflect the most recent evidence. The information addresses only the topics specifically identified therein and is not applicable to other interventions, diseases, or stages of diseases. This information does not mandate any particular course of medical care. Further, the information is not intended to substitute for the independent professional judgment of the treating provider, as the information does not account for individual variation among patients. Recommendations reflect high, moderate, or low confidence that the recommendation reflects the net effect of a given course of action. The use of words like “must,” “must not,” “should,” and “should not” indicates that a course of action is recommended or not recommended for either most or many patients, but there is latitude for the treating physician to select other courses of action in individual cases. In all cases, the selected course of action should be considered by the treating provider in the context of treating the individual patient. Use of the information is voluntary. ASCO provides this information on an “as is” basis and makes no warranty, express or implied, regarding the information. ASCO specifically disclaims any warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular use or purpose. ASCO assumes no responsibility for any injury or damage to persons or property arising out of or related to any use of this information, or for any errors or omissions.

Guideline and Conflicts of Interest

The Expert Panel was assembled in accordance with ASCO’s Conflict of Interest Policy Implementation for Clinical Practice Guidelines (“Policy,” found at http://www.asco.org/rwc). All members of the Expert Panel completed ASCO’s disclosure form, which requires disclosure of financial and other interests, including relationships with commercial entities that are reasonably likely to experience direct regulatory or commercial impact as a result of promulgation of the guideline. Categories for disclosure include employment; leadership; stock or other ownership; honoraria, consulting or advisory role; speaker’s bureau; research funding; patents, royalties, other intellectual property; expert testimony; travel, accommodations, expenses; and other relationships. In accordance with the Policy, the majority of the members of the Expert Panel did not disclose any relationships constituting a conflict under the Policy.

RESULTS

Two hundred twenty-two studies met the eligibility criteria and form the evidentiary basis for the guideline recommendations.1,3–223 The identified trials focused on the diagnosis, staging, chemotherapy treatment, surgical cytoreduction, and radiation therapy treatment of patients with MPM. The primary outcomes reported in studies on therapeutic interventions included overall survival, progression-free survival, response rate, toxicity, quality of life (QoL), and peri- and postoperative complications, while the studies on diagnosis and staging reported primary outcomes on diagnostic accuracy, correlations, and tumor response. Table 1 gives a summary of the study designs of the included studies; details on the study characteristics are included in Data Supplement 1. The systematic review flow diagram is also shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Details of Study Design of the Included Studies

| Study Design |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sections | Systematic Reviews/Meta-Analysis | Randomized Controlled Trial | Prospective Study | Retrospective Study | Prospective Retrospective | Total |

| Diagnosis | 5 | 2 | 15 | 5 | 2 | 29 |

| Staging | 3 | 1 | 14 | 11 | 4 | 33 |

| Chemotherapy | 2 | 10 | 9 23 phase II studies |

5 | 0 | 49 |

| Surgical cytoreduction | 11 | 3 (1 overlap with staging) | 16 1 phase II study |

31 | 1 | 63 |

| Radiation therapy | 6 | 4 | 15 (1 overlap with surgery) 7 phase II studies |

15 | 48 | |

| Total | 27 | 20 | 100 | 67 | 8 | 222 |

Fig 1.

Study flow diagram.

Study Quality Assessment

Study design aspects related to individual study quality, strength of evidence, strength of recommendations, and risk of bias were assessed. Refer to the Methodology Supplement for more information and for definitions of ratings for overall potential risk of bias.

RECOMMENDATIONS

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Question 1

What is the optimal way to make a diagnosis of pleural mesothelioma? Options include: (a) thoracentesis, (b) core needle biopsy, (c) thoracoscopic biopsy, and (d) open pleural biopsy

Recommendation 1.1.

Clinicians should perform an initial thoracentesis when patients present with symptomatic pleural effusions and send pleural fluid for cytologic examination for initial assessment for possible mesothelioma (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.2.

In patients for whom antineoplastic treatment is planned, it is strongly recommended that a thoracoscopic biopsy should be performed. This will: (a) enhance the information available for clinical staging; (b) allow for histologic confirmation of diagnosis; (c) enable more accurate determination of the pathologic subtype of mesothelioma (epithelial, sarcomatoid, biphasic); and (d) make material available for additional studies (eg, molecular profiling) (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.2.1.

When performing a thoracoscopic biopsy, the minimal number of incisions (two or fewer) is recommended and should ideally be placed in areas that would be used for subsequent definitive resection to avoid tumor implantation into the chest wall (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.3.

In patients with suspected mesothelioma in whom treatment is planned, an open pleural biopsy should be performed if the extent of tumor prevents a thoracoscopic approach. The smallest incision possible is encouraged (generally 6 cm or less is recommended) (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 1.4.

In patients who are not candidates for thoracoscopic biopsy or open pleural biopsy, who also have a nondiagnostic thoracentesis or do not have a pleural effusion, clinicians should perform a core needle biopsy of an accessible lesion (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

The diagnosis of MPM can be quite difficult from a pathologic perspective, as there are several different cell types (epithelioid, sarcomatoid, and mixed [biphasic]), and rarer subtypes (ie, desmoplastic, deciduoid), which can be challenging to distinguish from other primary tumors of the pleura, metastatic malignancy to the pleural surfaces, and benign, inflammatory or fibrotic abnormalities of the pleural space. Given the potential for diagnostic dilemmas, it is critical to have sufficient tissue for immunohistochemical staining utilizing standard antibody panels that aid in distinguishing mesothelioma from carcinoma and sarcoma. Biopsies should be of sufficient depth to be able to confirm the presence of invasion, one of the hallmarks that distinguish malignant mesothelioma from benign mesothelial proliferation.

When a patient with suspected MPM presents with a pleural effusion, the diagnostic work-up should begin with an ultrasound-guided thoracentesis with pleural fluid sent to cytopathology for analysis. Although less than one third of MPM can be diagnosed accurately on pleural fluid cytology,114 thoracentesis is a safe and reliable initial intervention that can also transiently alleviate the common presenting symptoms of dyspnea and chest discomfort. The diagnostic utility of thoracentesis is principally limited to the epithelioid subtype; sarcomatoid and biphasic mesothelioma are rarely detected in pleural fluid specimens.116

More definitive diagnosis necessitates performing thoracoscopy with multiple pleural biopsies, ideally from several different locations throughout the ipsilateral hemithorax. This approach is particularly important in patients for whom further treatment is planned. Biopsies should be of sufficient size and depth to allow for all requisite testing by surgical pathology. The diagnostic yield of thoracoscopy in mesothelioma is > 95%.100,113,114

In patients who present with nodular pleural thickening without a pleural effusion, computed tomography (CT)–guided core biopsy of pleural-based masses is a reasonable diagnostic alternative to more invasive surgical interventions. CT-guided biopsy of pleural nodules under local anesthesia may also be a reasonable option in patients who are poor candidates for thoracoscopy.12,33 Open pleural biopsy, a relatively limited and generally low-risk surgical alternative, can also be considered for these patients, as well as for those without an effusion or a patent pleural space to allow for safe thoracoscopy.

Uncommon variants of MPM may evade diagnostic confirmation even with large thoracoscopic or open pleural biopsies. The classic example is desmoplastic mesothelioma, in which the malignant cells are rare and interspersed within a large volume of densely fibrotic stroma. Sometimes this variant can only be diagnosed either from a large surgical specimen or at autopsy.

Clinical Question 2

Is cytology of pleural fluid as sensitive and specific as histology in making a diagnosis of pleural mesothelioma?

Recommendation 2.0.

Cytologic evaluation of pleural fluid can be an initial screening test for mesothelioma, but it is not a sufficiently sensitive diagnostic test. Whenever definitive histologic diagnosis is needed, biopsies via thoracoscopy or CT guidance offer a better opportunity to reach a definitive diagnosis (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

Cytologic examination of pleural fluid is not sufficiently sensitive to make a diagnosis of mesothelioma. This may be attributed to the difficulty of differentiating mesothelioma tumor cells from reactive mesothelial cells, sample preparation, or the extent of disease.26,114 In a study of 75 patients with mesothelioma, 82% of patients with positive pleural fluid cytology had visceral pleural involvement, whereas only 30% of patients with negative pleural fluid cytology had disease involving the visceral pleura.26

Immunohistochemical studies are of limited value to differentiate mesothelioma from benign mesothelial cells.211 Recent studies suggest that the loss of the BRCA1-associated protein (BAP1) and deletion of p16 seen in mesothelioma but not reactive mesothelial cells could be useful adjuncts for cytologic diagnosis of mesothelioma.224,225 Immunohistochemical staining of pleural fluid cytology specimens may help differentiate mesothelioma from adenocarcinoma, however. In a study of 159 malignant pleural effusions, Claudin-4 immunohistochemistry staining was positive in 83 of 84 adenocarcinoma cases and negative in all 64 mesothelioma samples, thereby differentiating adenocarcinoma from mesothelioma with high sensitivity and specificity.158

Clinical Question 3

What panel of immunohistochemistry stains is required to make a diagnosis of mesothelioma?

Recommendation 3.0.

Histologic examination should be supplemented by immunohistochemistry using selected markers expected to be positive in mesothelioma (eg, calretinin, keratins 5/6, and nuclear WT1) as well as markers expected to be negative in mesothelioma (eg, CEA, EPCAM, Claudin 4, TTF-1). These markers should be supplemented with other markers that address the differential diagnosis in that particular situation (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

Numerous studies summarized in reviews226,227 suggest immunohistochemical panels to include markers that positively identify mesothelioma. The most important ones are calretinin, keratins 5/6, Wilms tumor protein 1 (WT1), and podoplanin. None is entirely specific for mesothelioma, but together, when interpreted in the context of histologic features, they are all useful. Also recommended are markers expected to be negative in mesothelioma but positive in adenocarcinoma (especially pulmonary adenocarcinoma). Most important are carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EPCAM, for which two antibodies are commonly used: MOC31, and BerEP4), blood group 8, and Claudin 4. Additional markers typically positive in lung adenocarcinoma and negative in mesothelioma are napsin A and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1). Positive markers for other tumor types should be used for differential diagnosis of mesothelioma and metastatic carcinomas from various sources, metastatic melanoma, or lymphoma as clinically applicable.226,227 Fluorescent in situ hybridization studies for detection of hetero- or homozygous loss of p16/CDKN2A locus at 9p21202 could be used to support the diagnosis of MPM over a benign process. Loss of BRCA1-associated protein (BAP1) expression is also emerging as an immunohistochemistry marker for MPM and may augur a better prognosis.64

Clinical Question 4

Do the pathologic subtypes of mesothelioma have prognostic significance? What is the optimal way to report histologic composition?

Recommendation 4.1.

Mesothelioma should be reported as epithelial, sarcomatoid, or biphasic, because these subtypes have a clear prognostic significance (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 4.2.

In surgical, thoracoscopic, or open pleural biopsies with sufficient tissue, further subtyping and quantification of epithelial versus sarcomatoid components of mesothelioma may be undertaken (Type of recommendation: informal consensus; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

It is insufficient to report the pathologic diagnosis of this disease simply as malignant mesothelioma. The histologic subtype—epithelial, sarcomatoid, or biphasic—should be documented, as it has significant prognostic and therapeutic implications for patients with MPM. Patients with sarcomatoid histology have a much shorter survival than the other subtypes, fail to benefit from surgery, and are less likely to respond to systemic therapy. Biphasic tumors have an intermediate prognosis between epithelial and sarcomatoid.

In the SEER database, the median survival in patients with epithelial, biphasic, and sarcomatoid disease who underwent surgery was 19, 12, and 4 months, respectively (P < .01). Surgery improved survival in patients with epithelioid, but not biphasic or sarcomatoid, histology.79 Thus, surgery is not recommended in patients with sarcomatoid MPM. Emerging evidence also suggests that the percentage of epithelioid differentiation is an independent predictor of survival in patients with biphasic MPM.78 Patients with epithelioid differentiation of 100%, 51% to 99%, and < 50% had median overall survivals of 20.1, 11.8, and 6.62 months, respectively (P < .001) in a 144-patient series.78 A systematic review of 30 MPM trials that reported tumor response rates by histologic subtype documented fewer responses in patients with sarcomatoid histology than in the other subtypes.198

Clinical Question 5

Are there any non–tissue-based biomarkers that can be used to diagnose patients with mesothelioma, to predict outcome, or to monitor tumor response?

Recommendation 5.0.

The non–tissue-based biomarkers that are under evaluation at this time do not have the sensitivity or specificity to predict outcome or monitor tumor response and are therefore not recommended (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

None of the non–tissue-based biomarkers being evaluated at this time for MPM have sufficiently rigorous prospective/blinded validation to recommend their use.

Despite a high-risk, asbestos-exposed population that could be an ideal cohort for the development of diagnostic biomarkers for MPM, the gold standard, soluble mesothelin-related protein (SMRP), has a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of only 32%. Multiple single-institution cohort studies of serum SMRP have compared levels in patients with MPM to (1) asbestos-exposed non–cancer-bearing controls, (2) healthy controls, (3) non-MPM malignant controls, and (4) controls with inflammatory diseases.203 At a common diagnostic threshold of 2.00 nmol/L, the sensitivities and specificities of SMRP ranged widely (19% to 68% and 88% to 100%, respectively). The utility of SMRP in early diagnosis was evaluated in 217 patients with stage I or II epithelioid and biphasic MPM and 1,612 controls. The resulting area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.73 to 0.81). At 95% specificity, SMRP yielded a sensitivity of 32% (95% CI, 26% to 40%).203 In the United States, SMRP measurements are only available through a reference laboratory.

SMRP has been compared with other biomarkers, including osteopontin (OPN) and Fibulin-3 (FBLN3). OPN lacked the specificity for MPM demonstrated by SMRP when nonmesothelioma cohorts were used. Low baseline OPN levels were independently associated with favorable progression-free and overall survival in two studies, while SMRP was not prognostic.97,164 The original publication153 describing FBLN3 reported 100% sensitivity and 94% specificity for stage I or II MPM compared with individuals with asbestos exposure or nonmesotheliomas with pleural effusions; a blinded validation of 48 MPMs and 96 asbestos-exposed controls achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.87. Validation of these data has not been consistent.90 Effusion FBLN3 was an independent significant prognostic factor for survival in patients with MPM153 (hazard ratio [HR], 2.08; P = .017). Patients with MPM with effusion FBLN3 levels below the median survived significantly longer than those above (14.1 v 7.9 months; P = .012). The diagnostic value of FBLN3 for MPM was recently validated89 (sensitivity 93.0%, specificity 90.0%), though a prognostic effect was not observed. The reliability of the FBLN3 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is under active investigation and could account for these disparate findings.

Clinical Question 6

Is there a role for tumor genomic sequencing in mesothelioma?

Recommendation 6.0.

While tumor genomic sequencing is currently done on a research basis in mesothelioma and may become clinically applicable in the near future, it is not recommended at this time (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

The current role of genomic sequencing in MPM is limited to research studies. The most comprehensive genomic analysis to date228 describes the exome and transcriptome sequencing of 216 tumor and control specimens of patients with MPM. BAP1, NF2, TP53, SETD2, DDX3X, ULK2, RYR2, CFAP45, SETDB1, and DDX51 were frequently mutated. Many other genes were additionally silenced by copy number changes and chromosomal deletions. Through integrated analyses, alterations in Hippo, mammalian target of rapamycin, histone methylation, RNA helicase, and p53 signaling pathways were identified. Four consensus clusters defined through RNA sequencing correlated with survival and the degree of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. The frequencies of mutations of TP53, SETD2, and NF2 were different in the four clusters. BAP1 mutations were present in at least a quarter of each cluster type; these may aid in the diagnosis of MPM and in identifying some familial cases.

STAGING

Clinical Question 1

What are the optimal tests required to stage patients with mesothelioma? (a) CT, (b) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, (c) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), (d) mediastinoscopy, (e) thoracoscopy, (f) laparoscopy, and (g) endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS).

Recommendation 1.1.

A CT scan of the chest and upper abdomen with IV contrast is recommended as the initial staging in patients with mesothelioma (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.2.

An FDG PET/CT should usually be obtained for initial staging of patients with mesothelioma. This may be omitted in patients who are not being considered for definitive surgical resection (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.3.

If abnormalities that suggest metastatic disease in the abdomen are observed on a chest and upper abdomen CT or on a PET/CT, then consideration should be given to perform a dedicated abdominal (+/− pelvic) CT scan, preferably with IV and oral contrast (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.4.

An MRI (preferably with IV contrast) may be obtained to further assess invasion of the tumor into the diaphragm, chest wall, mediastinum, and other areas (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

Two systematic reviews,208,209 seven prospective cohort studies,104,119,122,124,136,138,152 and five retrospective studies19,31,63,68,157 were identified. One systematic review included 15 studies on PET; another included 14 studies on CT, PET, combination PET/CT and MRI. The prospective studies focused on preoperative CT scan104 [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT scan,104,136 mediastinoscopy,119 bilateral thoracoscopy,119 laparoscopy,119 MRI,122,124 extended surgical staging,138 and cervical mediastinoscopy.152 The retrospective studies19,31,63,68,157 addressed the potential of both volumetric CT scanning and pleural thickness measurements to determine the T stage of the primary tumor; these remain research questions at present.

CT scan of the chest and upper abdomen with intravenous (IV) contrast is the standard initial imaging study for the clinical staging of MPM. Although CT delineates the overall extent of the primary tumor, it may not precisely define some areas of tumor invasion. The coronal and sagittal CT views are sometimes more helpful than axial cuts in this regard, but interpretation of chest wall or diaphragm invasion can still be problematic. It may also be difficult to distinguish mediastinal adenopathy from adjacent mediastinal pleural tumor on CT, particularly in the subcarinal space. MRI sometimes provides better definition of tumor involvement of the chest wall and diaphragm, but it is not performed in most institutions because it does not routinely add enough information to CT to warrant the additional cost and complexity.

FDG PET/CT scanning identifies metastatic disease not seen on CT in about 10% of patients, and the degree of FDG uptake (as measured by the maximum standardized uptake value) on PET is prognostic of outcome. PET is sometimes used to assess treatment response in patients receiving chemotherapy; however, PET can be problematic to interpret in patients who have received a talc pleurodesis.

Invasive staging techniques can supplement the information obtained from these imaging studies. Mediastinoscopy can confirm the presence of paratracheal and subcarinal lymph node metastases, while EBUS and endoscopic ultrasound also allow access to aortopulmonary window, hilar, and some lower mediastinal and para-esophageal nodes. Unlike primary lung cancers, pleural mesotheliomas often metastasize preferentially to mediastinal rather than hilar lymph nodes, and regional lymph node involvement has consistently been associated with a poor prognosis. Thus, mediastinoscopy, EBUS, and EUS can provide important staging information, but up to half of involved mediastinal lymph nodes are located in areas not accessible with these procedures, including the anterior mediastinum, pericardial fat pad, and peridiaphragmatic and posterior intercostal regions, and may only be diagnosed at exploratory thoracotomy. While some institutions routinely perform mediastinoscopy or EBUS/EUS for staging, others use these procedures selectively, depending on findings from imaging studies and the overall plans for multimodality treatment.

Laparoscopy can clarify whether transdiaphragmatic tumor invasion is present. Bulky tumor in the lower hemithorax often involves and depresses the hemidiaphragm, making it difficult to determine whether T4 or M1 disease is present. Laparoscopy can identify tumor directly extending through the diaphragm (T4) or peritoneal metastases. While some institutions routinely perform staging laparoscopy, most use it selectively to supplement information available from imaging studies.

Recommendation 1.5.

For patients being considered for maximal surgical cytoreduction, a mediastinoscopy and/or endobronchial US should be considered if enlarged and/or PET-avid mediastinal nodes are present (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.6.

In the presence of contralateral pleural abnormalities detected on initial PET/CT or chest CT scan, a contralateral thoracoscopy may be performed to exclude contralateral disease (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 1.7.

In patients with suspicious findings for intra-abdominal disease on imaging and no other contraindications to surgery, it is strongly recommended that a laparoscopy be performed (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

The proper staging of MPM requires a combination of imaging studies (CT/MRI/PET), lymph node sampling (mediastinoscopy, EBUS, EUS), and surgical exploration to determine the extent of involvement of the pleural space. Chest and upper abdomen CT scan with IV contrast is the standard-of-care initial staging modality that allows determination of: involvement of ipsilateral visceral and parietal pleural surfaces; invasion of chest wall, lung parenchyma, and ipsilateral hemidiaphragm; enlargement of mediastinal and/or hilar nodes; presence of metastases in contralateral pleura and/or lung parenchyma; and transdiaphragmatic spread of tumor into the peritoneal cavity. Chest CT is also the basis for monitoring of response to therapy, as the accepted standard of modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) requires calculation of a sum of tumor measurements based upon three separate chest CT scan slices.163

[18F]FDG PET/CT scan can be a valuable adjunct to chest CT scan to help distinguish benign from malignant pleural abnormalities, to assess the likelihood of malignant involvement of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes, and to detect distant metastases.208,209 Findings on PET/CT scan need to be confirmed by obtaining tissue, especially in surgical candidates. It is important to recognize that the inflammation caused by talc pleurodesis renders subsequent PET images unreliable for the detection of pleural abnormalities.

MRI of the chest with IV contrast, particularly coronal sections, can also serve as an adjunct to chest CT scan in initial staging. MRI is particularly useful for aiding in the determination of chest wall, diaphragmatic, and/or mediastinal invasion/involvement by tumor.122 As with PET/CT, however, findings on MRI should be confirmed with additional interventions (ie, thoracoscopic examination of the pleural space to determine the extent of chest wall invasion), particularly in those patients who are slated to undergo maximal surgical cytoreduction.

Patients who are being assessed for maximal surgical cytoreduction should be considered for minimally invasive staging of mediastinal and hilar nodes. EBUS-guided fine-needle aspiration is more sensitive and specific for determining nodal involvement than standard cervical mediastinoscopy.31 There may also be a role for endoscopic ultrasound for biopsy of subdiaphragmatic and/or paraesophageal lymph nodes. If baseline imaging studies suggest involvement of the contralateral pleural space, this can have significant prognostic and therapeutic implications. For this reason, patients with these findings should undergo a contralateral thoracoscopy with pleural examination and biopsy to confirm the presence of mesothelioma. Similarly, those patients—particularly surgical candidates—who have imaging evidence of transdiaphragmatic invasion and/or involvement of abdominal organs should undergo laparoscopy and biopsy to pathologically confirm intraperitoneal spread of disease.119,152

Clinical Question 2

What are the limitations of the current staging system for surgical and clinical staging of pleural mesothelioma? (a) What are the key discrepancies between clinical and pathologic staging? (b) What are the limitations of staging in predicting prognosis?

Recommendation 2.0.

The current AJCC/UICC staging classification remains difficult to apply to clinical staging with respect to both T and N components and thus may be imprecise in predicting prognosis. Physicians should recognize that in patients with clinical stage I/II disease, upstaging may occur at surgery (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

One prospective cohort study135 and eight retrospective studies25,30,59,63,66–68,157 were identified. The prospective study assessed resected specimen weight and volume, while six of the retrospective studies25,30,59,66–68 focused on the MPM staging system, proposed adjustments to TNM staging criteria, and supplementary prognostic variables. Two papers63,157 evaluated the potential of CT-based assessment of tumor volume as a means of clinical T staging.

Clinical staging of MPM is challenging because, unlike many solid tumors, the anatomic characteristics of the primary tumor (irregular spread along the pleural surface) do not permit simple uni- or bidimensional measurements on imaging studies. The rarity of this malignancy has also made it difficult to generate data to support a widely accepted staging system. The recent development of a large multinational database through the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) and the International Mesothelioma Interest Group (IMIG) has generated sufficiently robust analyses of T, N, and M categories in relationship to overall survival to recommend revisions of the staging system for the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control (AJCC/UICC) staging manuals.

Clinical T staging of MPM currently depends on an assessment of the extent and depth of primary tumor involvement in the pleural space. This can be difficult to define accurately on CT or MRI imaging, which explains the frequent discrepancy between clinical and pathologic staging, especially in early-stage disease. Although recent analyses of the IASLC database suggest that this approach is still valid (with some revisions) for the 8th edition of the staging system, there is increasing evidence that measurement of pleural tumor thickness and/or volume may provide an easier and clinically more meaningful assessment of T category, though this approach remains experimental.

Clinical evaluation of nodal involvement (N category) is also problematic because lymph nodes are often difficult to distinguish from the adjacent abnormal pleura on CT, MRI, or PET and because there is no direct correlation between lymph node size and tumor involvement. In addition, the anatomic pattern of metastatic lymphatic disease in MPM differs from lung cancer, with predominant involvement of mediastinal nodes, including those in unusual locations such as the internal mammary, cardiophrenic, and even intercostal regions. Many of these nodes are also outside the reach of staging procedures such as mediastinoscopy or endobronchial and esophageal ultrasound, further reducing the accuracy of clinical staging. Recent analyses of the IASLC database have led to the recommendation to consider all ipsilateral intrathoracic lymph node involvement as N1 disease.

Most MPMs are diagnosed before distant metastases develop, because symptoms such as shortness of breath due to pleural effusion or chest pain prompt evaluation when the tumor is still confined to the chest. Most also tend to remain confined to the ipsilateral hemithorax for much of their clinical course. Although metastases often involve the peritoneum and the contralateral pleura, they can occur in other solid organs. Unlike lung adenocarcinoma, CNS metastases are uncommon, and thus evaluation of M stage is adequately achieved through CT of the chest and upper abdomen and PET imaging; imaging the brain is not required unless the patient has symptoms suggestive of brain metastasis.

Clinical Question 3

What is the optimal approach to radiologic-based tumor measurement and response classification (RECIST 1.1, modified RECIST for mesothelioma, volumetrics)?

Recommendation 3.1.

The optimal approach to mesothelioma measurement requires the expertise of a radiologist to identify measurement sites on CT as per modified RECIST for mesothelioma. This approach requires calculating the sum of up to six measurement sites with at least 1 cm thickness, measured perpendicular to the chest wall or mediastinum, with no more than two sites on each of three CT sections, separated by at least 1 cm axially (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 3.2.

Assessment of tumor volume by CT scan may enhance clinical staging and provide prognostic information but remains investigational and thus is not recommended (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 3.3.

It is recommended that tumor response classification be determined based on RECIST criteria from the comparisons of these sums across serial CT scans (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

Image-based measurements of mesothelioma are critical for decisions regarding patient enrollment on clinical trials, tumor response assessment, and patient surveillance. The morphology and growth pattern of mesothelioma differ substantively from other solid tumors,112 thus requiring an alternative to the clinically accepted measurement approach of RECIST.213,229 Modified RECIST,163 despite being published as a research study to investigate a known problem in the mesothelioma clinical research community, was quickly adopted as the standard for tumor measurement on the CT scans of patients with MPM.123 The modified RECIST approach requires acquisition of up to six measurements of tumor thickness, each at least 1 cm in extent, measured perpendicularly to the chest wall or mediastinum, with no more than two measurement sites on each of three separate CT sections separated axially by at least 1 cm.163

The acquisition of MPM tumor thickness measurements is conceptually a multistep process, with interobserver variability compounded at each of these steps.230 To mitigate measurement variability, measurements should be performed by a radiologist familiar with modified RECIST and mesothelioma. The same radiologist or radiologists preferably should acquire all measurements from all CT scans for all patients.231 Measurement consistency across the multiple CT scan time points for a patient is important, so measurements should be stored electronically and displayed as annotations superimposed on prior images as a reference for the radiologist acquiring measurements from a current image.154

Modified RECIST did not alter the tumor response classification criteria (the actual numeric values) that separate response categories (partial response, stable disease, and progressive disease); in fact, with the exception of the measurement acquisition approach previously described, modified RECIST implicitly adopted all other aspects of RECIST (and, by extension, the more recent RECIST 1.1).232 Accordingly, the sum of these up-to-six measurements of tumor thickness at each follow-up CT scan are compared with the corresponding sum from all previous scans of the patient to assess tumor response based on the RECIST criteria.

Computer-based extraction of tumor volume from imaging has been investigated65 in the context of staging,63 prognosis,43,133 and response to therapy in MPM,131,132,160,161 but only a modest correlation between CT-based tumor volume and gross tumor specimen volume has been observed.130 While assessment of tumor volume by CT may enhance clinical staging and provide prognostic information, it remains investigational at this time.

CHEMOTHERAPY

Clinical Question 1

In patients with newly diagnosed pleural mesothelioma, is there a role for chemotherapy and does it improve survival and QoL? (a) Who should receive supportive care instead of chemotherapy? (b) Is there a role for additional modalities in these patients?

Recommendation 1.1.

Chemotherapy should be offered to patients with mesothelioma because it improves survival and QoL (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 1.2.

In asymptomatic patients with epithelial histology and minimal pleural disease who are not surgical candidates, a trial of close observation may be offered prior to the initiation of chemotherapy (Type of recommendation: informal consensus; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 1.3.

Selected patients with a poor performance status (PS 2) may be offered single-agent chemotherapy or palliative care alone. Patients with a PS of 3 or greater should receive palliative care (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

Chemotherapy improves survival and QoL in previously untreated patients with MPM. In the pivotal study by Vogelzang et al,1 the combination of pemetrexed plus cisplatin improved the response rate, progression-free and overall survival compared with cisplatin alone. Using the Lung Cancer Symptom Scale instrument to evaluate QoL, the trial demonstrated statistically significant improvements in dyspnea and pain with combination chemotherapy. A similar study with raltitrexed/cisplatin showed that doublet chemotherapy improved overall survival compared with cisplatin alone. Global health-related QoL (HRQoL) was comparable on both arms (P = .848), and both treatments yielded improvements in dyspnea. Few clinically significant differences between treatment arms were observed using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) or Lung Cancer 13.10,17 In the MAPS (Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study) trial, the addition of bevacizumab to standard pemetrexed/cisplatin chemotherapy improved progression-free and overall survival. Chemotherapy improved QoL above baseline in both arms.20

The MS01 phase III trial compared active symptom control (ASC) to mitomycin/vinblastine/cisplatin or vinorelbine in 409 previously untreated patients with MPM. Median overall survival was 7.6 months for ASC and 8.5 months for the combined chemotherapy arms, which was not statistically significant (HR, 0.89; P = .29). There were no differences in the QoL subscales of physical functioning, pain, dyspnea, and global health status between arms. Exploratory analyses suggested a survival advantage for vinorelbine compared with ASC alone, which did not reach statistical significance since the study was underpowered (HR, 0.80; P = .08).6

Epithelial MPM can sometimes be quite indolent. In asymptomatic patients with epithelial histology and minimal pleural disease who are not surgical candidates, a trial of close observation may be offered prior to the initiation of chemotherapy. A 43-patient randomized trial compared immediate chemotherapy with mitomycin/vinblastine/cisplatin to chemotherapy at the time of symptomatic progression. Early chemotherapy provided an extended period of symptom control and a trend toward a survival improvement that was not statistically significant.18 The SWAMP (South West Area Mesothelioma and Pemetrexed) trial assessed HRQoL using the EQ-5D, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30, and LC-13 in 73 consecutive patients who were fit for first-line pemetrexed/platin chemotherapy; 58 patients received chemotherapy and 15 chose best supportive care (BSC). Patients who received chemotherapy maintained their QoL better than the BSC group (P = .006); the latter experienced a decline in their HRQoL, with worse dyspnea and pain. Patients receiving chemotherapy who had radiographic improvement or a decline in serum mesothelin also had a better HRQoL at 16 weeks.88

It is reasonable to offer selected patients with PS 2 single-agent chemotherapy with pemetrexed,126,129 vinorelbine,6 or gemcitabine.180 Response rates are expected to be quite low. Patients with a PS of 3 or greater should receive palliative care.

Clinical Question 2

What is the best chemotherapy regimen for patients with newly diagnosed pleural mesothelioma who are not candidates for surgery?

Recommendation 2.0.

The recommended first-line chemotherapy for patients with mesothelioma is pemetrexed plus platinum. However, patients should also be offered the option of entering in a clinical trial (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

Systemic chemotherapy consisting of a platinum plus pemetrexed with folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation is the recommended first-line systemic therapy for patients with MPM with a good (≤ 2) performance status. The trial that led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of this regimen in MPM was a single-blind, placebo-controlled randomized phase III trial that compared cisplatin (75 mg/m2) with or without pemetrexed (500 mg/m2) in 456 previously untreated patients with MPM. The combination achieved a superior median overall survival (12.1 v 9.3 months; P = .020; HR, 0.77) and progression-free survival (5.7 v 3.7 months; P = .001) and a higher response rate (41.3% v 16.7%; P < .001) when compared with single-agent cisplatin. Vitamin supplementation was instituted after the first 117 patients enrolled, resulting in a significant reduction in toxicity without impairing survival. Toxicity was, of course, greater with the combination, producing grade 3/4 neutropenia, leukopenia, and nausea in 27.9%, 17.7%, and 14.6% of patients, respectively.

A phase III trial that compared the antifolate raltitrexed (80 mg/m2) plus cisplatin (80 mg/m2) to cisplatin alone in 250 patients similarly demonstrated higher response rates (23.6% v 13.6%) and a superior median overall (11.4 v 8.8 months) and 1-year survival (46% v 40%), for the antifolate/platinum combination compared with cisplatin alone. In this study there was no difference in HRQoL between the two arms.10,17

Clinical Question 3

What is the role of adding bevacizumab to the chemotherapy regimen of pemetrexed and cisplatin? Are there patients with mesothelioma who should not get bevacizumab?

Recommendation 3.1.

The addition of bevacizumab to pemetrexed-based chemotherapy improves survival in select patients and therefore may be offered to patients with no contraindications to bevacizumab. The randomized clinical trial demonstrating benefit with bevacizumab used cisplatin/pemetrexed; data with carboplatin/pemetrexed plus bevacizumab are insufficient for a clear recommendation (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: high; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 3.2.

Bevacizumab is not recommended for patients with PS ≥ 2, substantial cardiovascular comorbidity, uncontrolled hypertension, age > 75, bleeding or clotting risk, or other contraindications to bevacizumab (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

MAPS, an open-label randomized phase III trial in 448 patients with MPM compared standard pemetrexed/cisplatin with or without the addition of bevacizumab, 15 mg/kg every 21 days.20 Eligible patients were age 75 years or younger, with no cardiovascular comorbidity or uncontrolled hypertension, who were not receiving antiaggregant, antivitamin K, low-molecular-weight heparin, or nonsteroidal agents. The three-drug combination produced a longer median overall survival compared with pemetrexed/ cisplatin (18.8 v 16.1 months; P = .0167; HR, 0.77). The superior overall survival in the control arm (which was 12.1 months in the Vogelzang et al1 trial) was attributed in part to the rigorous eligibility criteria for bevacizumab treatment. Progression-free survival was also superior with the triplet (9.2 v 7.3 months; P < .001; HR, 0.61).

As expected, the addition of bevacizumab increased the rate of grade 3/4 toxicity (71% v 62%) especially hypertension (25% v 0%) and thrombosis (6% v 1%); grade 1/2 epistaxis was also more frequent (37.4% v 6.3%). More patients stopped treatment because of toxic effects in the bevacizumab arm than in the control group (24.3% v 6%; P < .001). There was no detriment to QoL with the addition of bevacizumab.

On the basis of these data, it is recommended that the triplet regimen of bevacizumab, pemetrexed, and cisplatin may be offered to patients with no contraindications to bevacizumab. Given the high frequency of cardiovascular comorbidity and hypertension among patients with MPM, however, it is important to carefully select patients who might benefit from the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy.

The data for bevacizumab with carboplatin/pemetrexed are insufficient for a clear recommendation. A phase II trial of pemetrexed, carboplatin (AUC 5), plus bevacizumab in 76 previously untreated patients with MPM achieved a partial response rate of 34.2%, with manageable toxicity. The median progression-free and overall survival was 6.9 and 15.3 months, respectively.184 There are no randomized data for this combination.

Clinical Question 4

When should carboplatin be used instead of cisplatin in patients with pleural mesothelioma?

Recommendation 4.0.

In patients who may not be able to tolerate cisplatin, it is recommended that carboplatin may be offered as a substitute for cisplatin (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

Carboplatin is generally better tolerated and easier to administer than cisplatin. Although no randomized studies in MPM directly compare carboplatin to cisplatin, data from multiple phase II series and the pemetrexed Expanded Access Program suggest that they are likely equivalent in this disease. In phase II studies,174,176,185 carboplatin (AUC 5) combined with pemetrexed achieved response rates ranging from 19% to 29%, median progression-free survival of 7 to 8 months, and median overall survival of 13 to 14 months,46,185 similar to the pivotal phase III trial of cisplatin and pemetrexed.1 In a retrospective pooled analysis, patients > 70 years of age who were treated with pemetrexed and carboplatin achieved similar outcomes as their younger counterparts, though they experienced more frequent hematologic toxicity.46

Among 1,704 previously untreated patients with MPM in the international Expanded Access Program, comparable response rates (26.3% v 21.7%), time to progression (7 v 6.9 months) and 1-year survival (63.1 v 64%) were reported for treatment with pemetrexed plus cisplatin or carboplatin, respectively. Grade 3/4 neutropenia was greater in patients who received pemetrexed plus carboplatin than pemetrexed plus cisplatin: 36.1% v 23.9%, respectively.127

Based on the available nonrandomized data, substituting carboplatin for cisplatin is an acceptable first-line option for patients with unresectable MPM.

Clinical Question 5

What is the most effective second-line therapy for patients with pleural mesothelioma? Can patients who have previously received pemetrexed be treated again with pemetrexed?

Recommendation 5.1.

Retreatment with pemetrexed-based chemotherapy may be offered in pleural mesothelioma patients who achieved durable (> 6 months) disease control with first-line pemetrexed-based chemotherapy (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 5.2.

Given the very limited activity of second-line chemotherapy in patients with mesothelioma, participation in clinical trials is recommended (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 5.3.

In patients for whom clinical trials are not an option, vinorelbine may be offered as second-line therapy (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

There are few active treatment options for previously treated patients with MPM. A phase III trial in 243 patients who had not received prior pemetrexed demonstrated higher response rates (18.7% v 1.7%; P < .001), superior disease control (59.3% v 19.2%; P < .0001), and longer progression-free survival (3.6 v 1.5 months; P = .0148) in those who received single-agent pemetrexed compared with BSC. This did not translate into an improvement in overall survival, however (8.4 v 9.7 months; P = .74) due to the greater use of subsequent chemotherapy in the BSC arm.7

Retreatment with pemetrexed-based chemotherapy is a reasonable option for patients who achieve durable disease control with first-line pemetrexed-based chemotherapy. A single-center retrospective review reported an overall response rate of 19% and a disease control rate of 48% among 31 patients who achieved disease control with front-line pemetrexed-based chemotherapy for at least 3 months and were then retreated with pemetrexed, alone or with a platinum.184 A multi-institution retrospective analysis of 30 patients documented a 66% disease control rate and decreased pain when patients who had at least 6 months of disease control with front-line pemetrexed/platin were rechallenged with a pemetrexed-based regimen. Time to progression was 5.1 months, and median overall survival was 13.6 months.41 A multicenter retrospective analysis showed that patients with MPM who experienced a time to progression of at least 12 months after first-line therapy had a greater likelihood of disease control with pemetrexed-based rechallenge.28

Vinorelbine is widely used as a second-line therapy in MPM, though there are limited data to support its efficacy. A single-center phase II trial of vinorelbine in 63 patients achieved a response rate of 16% and a median overall survival of 9.6 months. Similarly, a single-center retrospective review in 59 patients reported a 15% response rate and a disease control rate of 49%.233 In contrast, a retrospective review of 60 patients who received either vinorelbine or gemcitabine in the second- or third-line setting documented infrequent responses (none for vinorelbine and 2% for gemcitabine). Median progression-free survival was 1.7 and 1.6 months for vinorelbine and gemcitabine, respectively.60

Given the paucity of active agents in this setting, participation in clinical trials is highly recommended.

Clinical Question 6

What is the optimal duration of front-line chemotherapy for mesothelioma? Is there a role for pemetrexed maintenance therapy in pleural mesothelioma?

Recommendation 6.1.

In select asymptomatic patients with epithelial mesothelioma and a low disease burden who are not surgical candidates, a trial of expectant observation, with close monitoring, may be offered before initiation of systemic therapy (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 6.2.

Front-line pemetrexed-based chemotherapy should be given for four to six cycles. For patients with stable or responding disease, a break from chemotherapy is recommended at that point (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: moderate).

Recommendation 6.3.

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of maintenance chemotherapy and thus it is not recommended (Type of recommendation: evidence-based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Recommendation 6.4.

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of pemetrexed maintenance in mesothelioma patients and thus it is not recommended (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: low; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

In asymptomatic patients with epithelial histology and minimal pleural disease who are not surgical candidates, a trial of close observation may be considered before the initiation of chemotherapy. A small, 43-patient randomized trial that compared immediate chemotherapy to treatment when symptoms developed demonstrated that early chemotherapy provided a longer period of symptom control and a trend toward superior survival.18 Of the patients randomized to the delayed treatment group, 23% had a performance status deterioration that precluded subsequent chemotherapy. While it is reasonable to delay chemotherapy for patients with low disease burden and few symptoms, such patients should be monitored closely to ensure timely intervention.

In the pivotal study of pemetrexed/cisplatin that led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of this combination, patients received a median of six chemotherapy cycles, with a range of one to 12. The percentage of patients who completed at least four, six, or eight cycles was 71%, 53%, and 5%, respectively.1 Since patients with durable disease control with front-line chemotherapy can respond to retreatment with a pemetrexed-based regimen, a break from chemotherapy after four to six cycles of treatment is recommended.

There is insufficient evidence to support single-agent pemetrexed maintenance in MPM, and thus it is not recommended. A nonrandomized feasibility study in 27 patients demonstrated that maintenance pemetrexed was safe and that responses could be achieved after six cycles of induction chemotherapy. But the heterogeneous patient population (untreated and previously treated), the different induction regimens (pemetrexed/carboplatin or pemetrexed alone), the small number of patients who actually received maintenance therapy (13, only eight of whom had received front-line doublet induction chemotherapy), and the nonrandomized nature of this trial preclude any conclusions about the efficacy of this approach.234 A randomized study of maintenance pemetrexed following induction pemetrexed/platin (Cancer and Leukemia Group B 30901) closed due to poor accrual; preliminary data on this study have not yet been reported.

SURGICAL CYTOREDUCTION

Clinical Question 1

What is the role of surgical cytoreduction in mesothelioma: does it improve survival or QoL? (a) Is surgery for pleural mesothelioma ever curative, and does it prolong survival compared with chemotherapy alone? (b) Is there a role for additional modalities in these patients? (c) Which patient should not be considered for surgical cytoreduction?

Recommendation 1.1.

In selected patients with early stage disease, it is strongly recommended that a maximal surgical cytoreduction should be performed (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

Surgical therapy of MPM has evolved since the first description of extrapleural pneumonectomy (EPP) for this disease. The goal, a maximal cytoreduction or a macroscopic complete resection (MCR), is defined as residual tumor after resection of < 1 cm. Surgeons experienced with lung-sparing techniques and EPP continue to debate about which operation does a better job of achieving this goal. Patient selection is key in deciding whether a patient with early disease should have surgery. Patients with less bulky disease measured by CT volumetrics survive longer than those with bulkier disease,19,63,157 including patients with minimal solid disease and those who only have a pleural effusion. These are the ideal candidates for MCR; their median survival can be as long as 48 months.

Nevertheless, it is impossible to predict the biology of an epithelial MPM, even when it presents at an early stage or with minimal bulk. No randomized study comparing surgery for early-stage MPM with favorable prognostic indices to observation or chemotherapy has been performed, and systematic surgical reviews rarely address this issue. An analysis of 14 retrospective studies evaluating EPP, chemotherapy, or palliative surgery reported a 13-month median survival and 37% major morbidity with EPP. In patients with epithelial disease, survival was 19 months with EPP and 7 months for palliative resection.206 Similar studies of patients who could have surgery compared with those who had biopsy only or were unresectable reveal trends toward increasing overall and recurrence-free survival with surgery.32,115 A six-center retrospective analysis reviewed 1,365 consecutive patients with MPM from 1982 to 2012. Median survival for patients who received medical therapy (chemotherapy or BSC), pleurectomy/decortication (P/D), or EPP was 11.7 months, 20.5 months, and 18.8 months, respectively. Patients who underwent resection with adjuvant therapy survived significantly longer than those who received chemotherapy alone (19.8 v 11.7 months; P < .001).24 Age < 70 years, epithelial histology, and receipt of chemotherapy were favorable prognostic factors on multivariate analysis. In patients with all three favorable prognostic factors, median survival was 18.6, 24.6, and 20.9 months for medical therapy, P/D, and EPP, respectively (P = .596). Despite the limits of a retrospective analysis, these data suggest a modest benefit observed with surgery combined with systemic therapy. These data are similar to the most recent edition of the IASLC MPM staging project, which reported a 21-month median survival for patients with pathologic T1 disease.68 Future studies must extend staging supplemental variables with validation of already available clinical prognostic indices (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer trials and Cancer and Leukemia Group B prognostic scoring systems) along with laboratory parameters59 or novel biomarkers164 to define the best surgical candidates.

Recommendation 1.2.

Maximal surgical cytoreduction as a single modality treatment is generally insufficient; additional antineoplastic treatment (chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy) should be administered. It is recommended that this treatment decision should be made with multidisciplinary input involving thoracic surgeons, pulmonologists, medical and radiation oncologists (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

The futility of surgery alone for MPM results from the near impossibility of a complete microscopic resection and the high propensity for local recurrence. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy along with surgery as a multimodality approach evolved rapidly after demonstration of the efficacy of pemetrexed/cisplatin.1 Concurrently, data on extended survival with the use of postoperative adjuvant hemithoracic radiation therapy after EPP181 led to novel delivery approaches after MCR, including intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT).235,236

Systematic reviews have demonstrated a median overall survival of 13 to 23.9 months for patients treated with multimodality therapy.215 The neoadjuvant approach has been hampered by attrition rates for the various treatment stages, so it is important to report outcomes both as intent to treat and in patients receiving all planned therapy. In the larger phase II series of induction chemotherapy followed by surgery, with or without postoperative radiation therapy, the intent-to-treat survival ranged from 14 to 18.4 months, while the survival in those select patients who were able to receive all planned therapies ranged from 20.8 to 59 months.162,190,237 Patients who had a radiographic response to induction chemotherapy also had an improved survival (26.0 v 13.9 months; P = .05).172 In a review of supplementary prognostic variables in 2,141 resected patients from the IASLC staging project, adjuvant therapy was significantly associated with survival in both univariate (HR, 1.7; P < .001) and multivariate analyses (HR, 1.56; P < .001). Whether chemotherapy should be delivered before, during, or after surgery is an unresolved question that is the subject of planned trials. Other unanswered issues being evaluated in ongoing trials include the efficacy of IMRT after pleurectomy and the role of induction radiation therapy before EPP.194,238

Recommendation 1.3.

Patients with transdiaphragmatic disease, multifocal chest wall invasion, or histologically confirmed contralateral mediastinal or supraclavicular lymph node involvement should undergo neoadjuvant treatment before consideration of maximal surgical cytoreduction. Contralateral (N3) or supraclavicular (N3) disease should be a contraindication to maximal surgical cytoreduction (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

Clinical staging of MPM is dependent on radiologic findings as well as signs and symptoms of the disease. Diffuse chest wall or transdiaphragmatic involvement represent T4 disease, classically characteristic of a locally advanced, technically unresectable tumor. Suspected T4 disease should be confirmed with sensitive imaging techniques, including MRI. Diffuse chest wall involvement may be physically palpable or seen by PET/CT and is associated with chest wall pain. Suspected transdiaphragmatic extension should be confirmed by staging laparoscopy to avoid unnecessary thoracotomy. The most recent revisions of the IASLC Mesothelioma Staging Project confirm the poor survival for this category; median overall survival was 13.4 and 16.7 months, respectively, for clinical and pathologic stage T4 tumors.68

Surgical intervention after neoadjuvant treatment of T4 disease depends on the response to chemotherapy; rates of completion of all predefined approaches range between 33% and 71%.238 About 25% of patients have radiographic disease progression on chemotherapy, while significant pathologic responses in the resected specimens are rarely observed.238

If studies are suspicious for contralateral mediastinal or supraclavicular lymph node involvement, histologic confirmation must be obtained by EBUS, mediastinoscopy, or direct needle/core biopsy. Clinical evaluation of mediastinal adenopathy is notoriously inaccurate.

The new proposal for revisions of the N descriptors in the forthcoming 8th edition of the TNM classification separates lymph node stations into two categories: N1, metastases in the ipsilateral bronchopulmonary, hilar, or mediastinal (including internal mammary, peridiaphragmatic, pericardial fat pad, or intercostal) lymph nodes; and N2, metastases in the contralateral bronchopulmonary, hilar, or mediastinal lymph nodes or ipsilateral or contralateral supraclavicular lymph nodes.67

With the new classification, the median, 24-month, and 60-month survival of N2 disease is 13.9 months, 27%, and 0%, respectively. This new N2 category needs validation, however, as it only represented 2.3% of the IASLC registry participants. Notably, the poor survival observed with surgery for N2 disease is similar to that reported for pemetrexed/cisplatin chemotherapy without surgery.1 Chemotherapy should be delivered before any consideration of surgery in these patients, since the chances for satisfying MCR criteria are slim. For patients with N2 disease, the brief median survival and the absence of long-term survivors mandates against an initial surgical approach.

Clinical Question 2

Does histology and mediastinal lymph node status affect selection of patients for surgery?

Recommendation 2.1.

Patients with histologically confirmed sarcomatoid mesothelioma should not be offered maximal surgical cytoreduction (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

The importance of obtaining adequate tissue to ascertain the histology is paramount in deciding whether surgery is indicated. In a systematic review of studies with data on prognostic factors in patients who underwent EPP, nonepithelial histology was a significant prognostic factor in 11 of 17 reports; it was a trend in the remaining studies.221 A retrospective analysis of 663 patients treated at three institutions identified nonepithelioid histology as a significant prognostic factor for survival (HR, 1.3; P < .001).106 In a review of 1,183 patients in the SEER database, median survival in patients with epithelial, biphasic, and sarcomatoid disease who underwent surgery was 19, 12, and 4 months, respectively (P < .01). Surgery was associated with improved survival in patients with epithelioid disease, but not in those with biphasic or sarcomatoid histology.79

The percentage of epithelioid differentiation is an independent predictor of survival, which should be carefully considered when recommending surgery for patients with biphasic MPM.78 In a 144-patient series from a single center, patients with epithelioid differentiation of 100%, 51% to 99%, and < 50% had median overall survivals of 20.1, 11.8, and 6.62 months, respectively (P < .001).78

Recommendation 2.2.

Patients with ipsilateral, histologically confirmed mediastinal lymph node involvement should only undergo maximal surgical cytoreduction in the context of multimodality therapy (neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy). Optimally, these patients should be enrolled in clinical trials (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.

Lymph node involvement is observed in 35% to 50% of patients with MPM undergoing an MCR239 and is a poor prognostic indicator. A retrospective review of 348 surgical patients reported a median survival of 19 months in those with N0 or N1 disease, compared with 10 months for patients with positive N2, N2/N1, or internal thoracic nodes. Survival was also significantly worse when two or more N2 stations were affected (P < .001).57 In a systematic review of prognostic factors for surgery in MPM, 11 of 14 studies that described nodal involvement found it associated with poor prognosis.221 In a 529-patient retrospective series of EPP for epithelioid MPM, in which N1 disease was defined as within the visceral envelope and N2 as mediastinal, patients with N0, N1, N2, and N3 disease achieved median survivals of 26, 17, 13, and 7 months, respectively. Survival was shorter for patients with concurrent N1/N2 disease (13 months) than those with only N1 or N2 disease (17 and 16 months, respectively).73

The most recent edition of the IASLC Mesothelioma Staging Project recommendations evaluated 2,432 cases, including 851 with pathologic N category information. Survival was significantly inferior in patients with pathologically staged N1 or N2 tumors compared with N0 tumors (HR, 1.51; P < .001). Concurrent N1/N2 involvement portended a worse survival than N2 disease alone. There was no survival difference between N1 and N2 tumors.239 These data form the basis of the recommendation for the 8th edition of the staging system to merge N1 and N2 disease into one N category. N1 disease would refer to all ipsilateral intrathoracic nodal metastases. N3 nodes in the prior system would now be considered N2.

The impact of multimodality therapy on outcomes in patients with ipsilateral nodal disease in MPM is difficult to decipher. The median survival of 10 to 13 months for patients with ipsilateral lymph node involvement who undergo MCR appears no different from outcomes observed with systemic therapy alone. Other contributing factors include histology and T status, response to induction chemotherapy, and whether the patient completes all aspects of multimodality treatment. In a single-center retrospective review of 60 patients who received a variety of neoadjuvant chemotherapies followed by EPP and hemithoracic radiation therapy, the median survival of patients with no involved mediastinal lymph nodes was significantly better if they completed all three treatment modalities (59 v 8 months; P < .001); in patients with pathologic N2 involvement, however, there was no difference in survival (12 v 14 months; P = .9) whether all modalities were completed.162 In contrast, in a 77-patient multicenter phase II trial of neoadjuvant pemetrexed/cisplatin, EPP, and radiation therapy, median overall survival in patients with N1 or N2 disease was 16.6 months, but it was 29.1 months in patients with positive lymph nodes who completed all therapy.172 A single-center retrospective series of 186 patients with MPM who received induction cisplatin with gemcitabine or pemetrexed followed by EPP and radiation therapy reported that response to induction chemotherapy, but not lymph node status, was an independent prognostic factor for survival.133

Recommendations for the treatment of fit individuals with MPM in ipsilateral mediastinal nodes are limited by the lack of prospectively treated patients in randomized trials. Surgery alone is not appropriate in these patients, and a multimodality approach, preferably as part of a clinical trial, should be considered.

Clinical Question 3

What should surgeons consider when deciding the extent of maximal cytoreductive surgery (lung sparing v non–lung sparing)? What are the differences in outcomes (morbidity, QoL, survival) between lung-sparing and non–lung-sparing maximal cytoreductive surgery?

Recommendation 3.0.

Maximal surgical cytoreduction involves either EPP or lung-sparing options (P/D, extended P/D). When offering maximal surgical cytoreduction, lung-sparing options should be the first choice, due to decreased operative and long-term risk. EPP may be offered in highly selected patients when performed in centers of excellence (Type of recommendation: evidence based; Evidence quality: intermediate; Strength of recommendation: strong).

Literature review and clinical interpretation.