Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common infectious cause of infant brain damage and post-transplant complications worldwide. Despite the high global burden of disease, vaccine development to prevent infection remains hampered by challenges in generating protective immunity. The most efficacious CMV vaccine tested to-date is a soluble glycoprotein B (gB) subunit vaccine with MF59 adjuvant (gB/MF59), which achieved 50% protection in multiple historical phase II trials. The vaccine-elicited immune responses that conferred this protection has remained unclear. We investigated the humoral immune correlates of protection of CMV acquisition in populations of CMV-seronegative adolescent and postpartum women receiving the gB/MF59 vaccine. We found that gB/MF59 immunization elicited distinct CMV-specific IgG binding properties and IgG-mediated functional responses in adolescent and postpartum vaccinees, with heterologous CMV strain neutralization observed primarily in adolescent vaccinees. Using penalized multiple logistic regression analysis, we determined that protection against primary CMV infection in both cohorts was associated with serum IgG binding to gB present on a cell surface but not binding to the soluble vaccine antigen, suggesting that IgG binding to cell-associated gB is an immune correlate of vaccine efficacy. Supporting this, we identified gB-specific monoclonal antibodies that differentially recognized soluble or cell-associated gB, suggesting that structural differences in cell-associated and soluble gB are important for the generation of protective immunity. Our results indicated the importance of the native, cell-associated gB conformation in future CMV vaccine design.

One Sentence Summary:

Protection against CMV correlates with gB/MF59 vaccine-elicited IgG that binds cell-associated gB.

Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a ubiquitous viral pathogen and a leading cause of post-transplant and congenital infections worldwide (1, 2). In the United States alone, each year, 40,000 infants are born with congenital CMV infection, with nearly a third of these children developing permanent hearing loss, brain damage, or neurodevelopmental delays (3–5). A vaccine to prevent congenital CMV has been a “Tier 1 priority” for the U.S. National Academy of Medicine for almost 20 years (6), yet no CMV vaccines are currently licensed for clinical use.

CMV vaccine development remains hindered in part by limited knowledge of the immune responses that protect against CMV infection (7). Pre-existing immunity to CMV does not always prevent reinfection nor in utero transmission and congenital disease (8, 9). Therefore, development of an efficacious CMV vaccine requires rational vaccine design (10, 11). To address this need, we aimed to identify the humoral immune correlates of protection, defined as immune markers measured in vaccinees that are statistically associated with the rate of the clinical end point used for measuring vaccine efficacy (11, 12), for the most efficacious CMV vaccine candidate tested to-date. Identification of immune correlates of protection can be used as immunologic endpoints, which are important for evaluation of future CMV vaccine candidates.

Glycoprotein B (gB) is an CMV envelope glycoprotein highly conserved across the herpesvirus family and is essential for viral entry into all cells, making it an attractive target for vaccination (13, 14). Up to 70% of total serum antibodies specific to CMV are directed against gB (15), yet most antibodies generated against gB are non-neutralizing, that is they do not inhibit viral infection of cells (16). The recombinant CMV gB subunit combined with MF59 adjuvant (Sanofi Pasteur) conferred approximately 50% protection in Phase II clinical trials of CMV-seronegative adolescent girls (17) and postpartum women (18). In the gB/MF59 vaccine, the gB sequence was derived from the CMV Towne strain (genotype 1) and modified by mutagenesis of the furin cleavage site and removal of the transmembrane domain, such that the truncated gB continued in-frame with the downstream carboxyl-terminus cytoplasmic component (19). The gB vaccine was thus expressed as a secreted polypeptide (19). Although the gB/MF59 vaccine showed partial protection against primary CMV acquisition, the immune responses that conferred this protection remain unclear.

Previous studies suggested that non-neutralizing antibody responses may have contributed to the partial efficacy of the gB/MF59 vaccine. In CMV-seronegative transplant recipients, gB/MF59 vaccination reduced the duration of CMV viremia and antiviral therapy; however, vaccination did not elicit neutralization of heterologous CMV strains (20, 21). Similarly, in CMV-seronegative postpartum women, vaccination elicited limited neutralization of the autologous Towne strain and negligible neutralization of heterologous strains (22). By contrast, antibody-dependent cell-mediated phagocytosis (ADCP), a non-neutralizing function of antibodies, was measurable in nearly all postpartum vaccinees (22). These studies implicated non-neutralizing antibody responses in protection against CMV primary infection but lacked the statistical power to identify the immune responses associated with protection from primary CMV infection (“immune correlates of protection”) for the gB/MF59 vaccine (11).

In this study, we assessed serum IgG-mediated immune responses in the Phase II gB/MF59 clinical trials in postpartum women (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT00125502) and adolescent girls (NCT00133497) to identify associations between vaccine-elicited humoral immune responses with risk of primary CMV acquisition. The results of this study will guide CMV vaccine design and candidate selection.

Results

Comparison of vaccine-elicited antibody responses in adolescent vaccinees (AV) and postpartum vaccinees (PV)

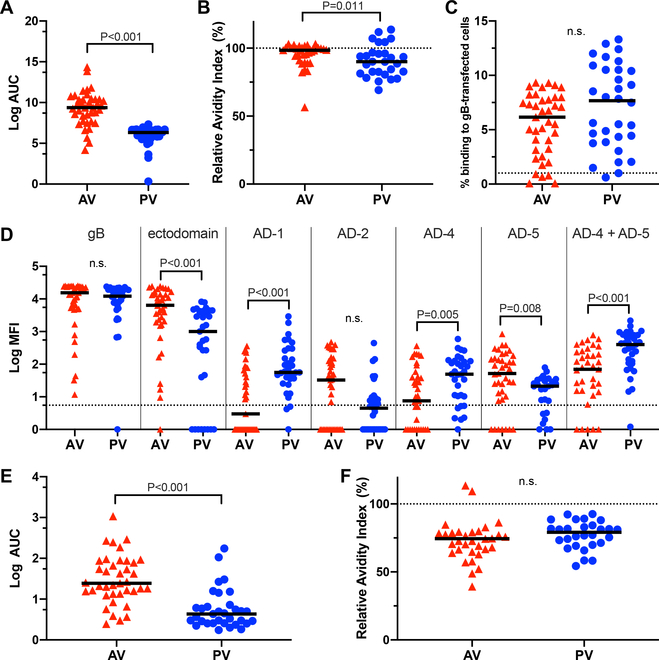

To determine whether the datasets of immune responses from the AV and PV vaccination cohorts (table S1) could be combined for immune correlate regression analyses, we first compared the vaccine-elicited sera IgG binding profiles and IgG-mediated functional responses between AV and PV. We found that gB/MF59 vaccination elicited unique IgG binding profiles for each cohort (table S2). Compared to PV, AV demonstrated higher IgG binding to and avidity for the gB vaccine immunogen (Fig. 1A, B), but the IgG from each cohort bound similarly to full-length gB presented in a cellular context on epithelial cells (Fig. 1C, fig. S1). By mapping IgG binding to specific antigenic domains (AD), we found that AV had higher IgG binding to the gB ectodomain and gB AD-5, whereas PV had higher binding to gB AD-1, AD-4, and AD-4 + AD-5 (Fig. 1D). In AV, the dominant linear gB epitope for IgG binding was in the AD-3 region expressed in the cytosol of infected cells (fig. S2), as previously reported in PV (22). AV demonstrated higher magnitude IgG binding to whole CMV virions (Fig. 1E), but IgG binding avidity for whole virions was similar between the cohorts (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1. Sera from adolescent and postpartum vaccine cohorts exhibited distinct CMV and gB-specific IgG binding responses.

(A) Log area under the curve (Log AUC) for IgG binding to full-length gB by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in AV and PV. Log AUC median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). (B) Relative IgG binding avidity to gB by ELISA, calculated as the ratio of antibody binding in the presence or absence of urea. Log AUC median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). (C) Frequency of IgG binding to gB-transfected HEK293T cells. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with separate plasmids encoding gB and GFP. Cells positive for IgG binding were detected by flow cytometry and were defined as the % of live singlet cells positive for both GFP and anti-human IgG Fc PE. Dotted line indicates the threshold for detection of gB-transfected cell IgG binding, defined as 1% using the average binding of CMV-seronegative sera (n = 11) + 2x the standard deviation. Median % binding to gB-transfected cells is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 32 PV). (D) Log mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IgG binding to full-length gB, gB ectodomain, AD-1, AD-2, AD-4, AD-5, and AD-4 + AD-5 as detected by binding antigen multiplex assay (BAMA). Dotted line indicates the threshold for positivity, defined by the average of CMV-seronegative samples (n = 28) + 2x the standard deviation. Log MFI median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). (E) Log AUC for IgG binding to TB40/E strain whole virus by ELISA. LogAUC median (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). (F) Relative IgG binding avidity to whole TB40/E virions by ELISA, calculated as the ratio of antibody binding in the presence or absence of urea. Log AUC median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). For all assays, samples were run in duplicate, and statistical significance was determined by Mann Whitney U test. n.s., not significant; red triangles, adolescent vaccinees (AV); blue circles, postpartum vaccinees (PV).

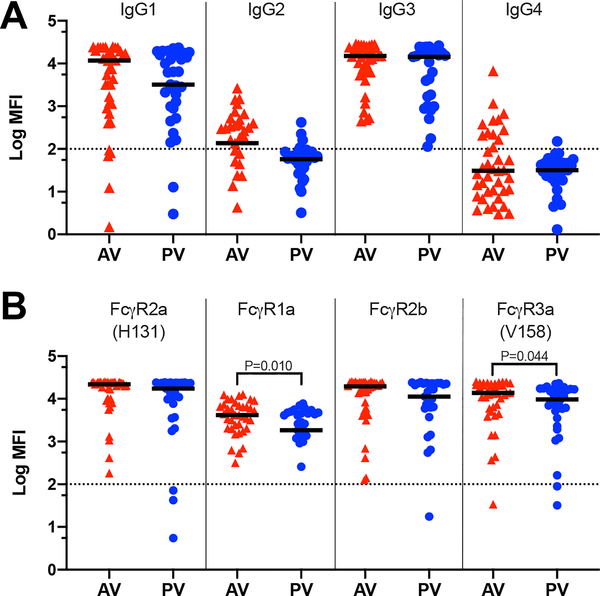

Between the AV and PV cohorts, vaccination also elicited differential gB-specific IgG Fc region features and Fc-mediated functions. The cohorts had similar gB-specific IgG subclass profiles with dominant responses of IgG1 and IgG3 (Fig. 2A), as expected in response to vaccination with a viral antigen (23). Engagement of vaccine-elicited IgG to Fcγ receptors (FcγR) was similar between the cohorts for FcγR2a (H131) and FcγR2b (Fig. 2B); however, IgG from the AV exhibited higher engagement to FcγR3a (V158) and FcγR1a (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Properties of vaccine-elicited IgG Fc regions were distinct between the adolescent and postpartum cohorts.

(A) Log MFI for gB binding by IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4 subclass antibodies, as measured by BAMA. Log MFI median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). (B) Log MFI for gB-specific IgG engagement by FcγR2a (H131), FcγR1a, FcγR2b, and FcγR3a (V158) as measured by BAMA. Log MFI median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). All samples were run in duplicate, and dotted lines indicate the thresholds for positivity, defined as 100 MFI. Statistical significance was determined by Mann Whitney U test; those lacking P values were determined not significantly different. Red triangles, adolescent vaccinees (AV); blue circles, postpartum vacinees (PV).

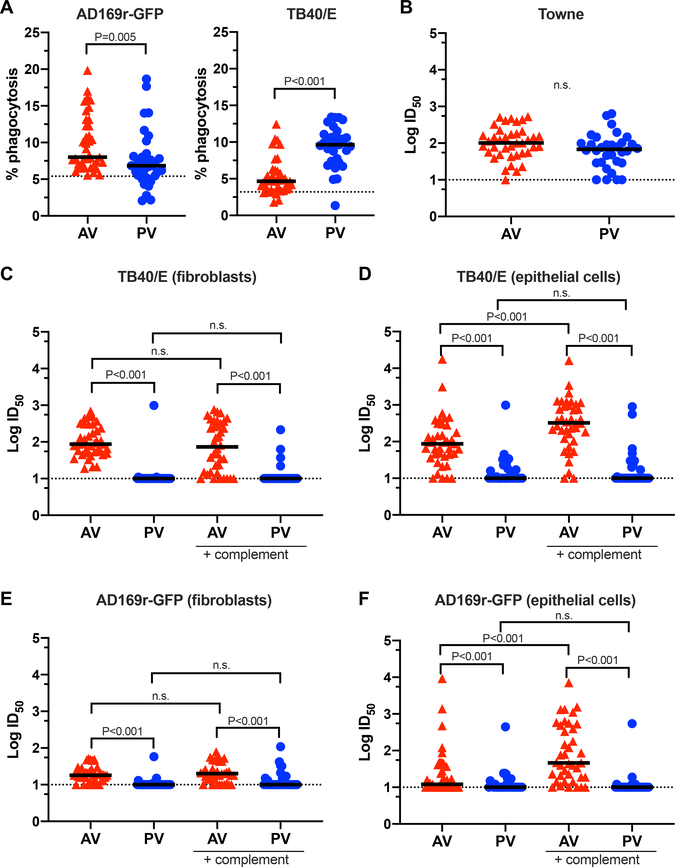

FcγR1a is the high-affinity FcR involved in effector cell activation and ADCP (24). Both cohorts mediated ADCP for heterologous CMV strains, but they demonstrated CMV strain-specific differences in phagocytosis (Fig. 3A). Consistent with previous reports of poor antibody-dependent cellular toxicity (ADCC) responses in PV (22), this response was also poorly elicited in AV (fig. S3).

Fig. 3. Vaccine-elicited functional antibody responses were distinct between the adolescent and postpartum cohorts.

(A) Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) by THP-1 monocytes of fluorescently labeled AD169r-GFP strain or TB40/E strain virus. Dotted line indicates the threshold for positivity, as defined by the average of CMV-seronegative samples run simultaneously (n = 6) + 2x the standard deviation. Median % phagocytosis is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). (B) Autologous neutralization of Towne strain virus, reported as the log-transformed dilution that prevented 50% infection of MRC-5 fibroblasts by the virus (LogID50). For all neutralization assays, dotted lines indicate the threshold of detection (starting sera dilution). LogID50 median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). (C) Neutralization of TB40/E strain virus on BJ5T-a fibroblasts in the presence or absence of rabbit complement. LogID50 median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). (D) Neutralization of TB40/E strain virus on ARPE epithelial cells in the presence or absence of rabbit complement. LogID50 median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). (E) Neutralization of AD169r-GFP strain virus on BJ5T-a fibroblasts in the presence or absence of rabbit complement. LogID50 median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). (F) Neutralization of AD169r-GFP strain virus on ARPE epithelial cells in the presence or absence of rabbit complement. LogID50 median is indicated (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV). For all assays, samples were run in duplicate. Statistical significance was determined by Mann Whitney U test. n.s., not significant; red triangles, adolescent vaccinees (AV); blue circles, postpartum vacinees (PV).

We explored the vaccine-elicited neutralization responses against the autologous vaccine strain (Towne) and heterologous CMV strains in AV and PV. Immunization with gB/MF59 induced neutralization against the autologous Towne strain similarly in the AV and PV cohorts (Fig. 3B). Only AV generated robust heterologous virus neutralization responses. AV sera neutralized strains TB40/E and AD169r on both fibroblasts and epithelial cells, with complement-mediated enhancement on epithelial cells, whereas heterologous virus neutralization was negligible in PV (Fig. 3C–F). To determine if subject age was associated with the elicitation of CMV-neutralizing responses, we performed linear regression analyses between subject ages and neutralizing responses for each virus strain. We found that heterologous virus neutralization inversely correlated with subject age across most CMV strains (table S3).

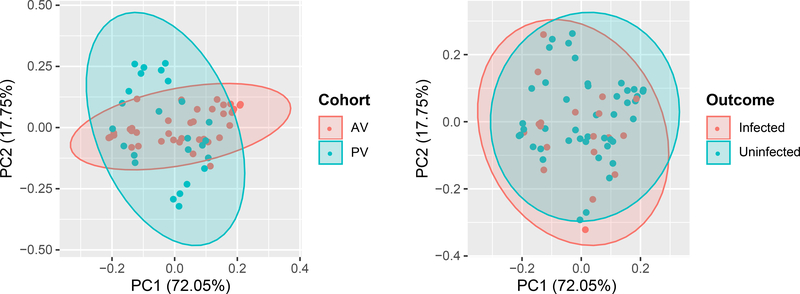

To visualize the overlap in vaccine-elicited immune responses between AV and PV, we compared these cohorts by principal component analysis (PCA) across all measured features, excluding heterologous virus neutralization due to the negligible responses in PV. Projected onto the first two principal components, the datasets show a high degree of overlap in the location and covariance structure by subject infection status (Fig. 4). In contrast, the immune responses by treatment cohort show overlap in location but different covariance structures (Fig. 4). Thus, we performed subsequent immune correlate analyses both with the cohorts combined and independently.

Fig. 4. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to visualize humoral immunogenicity variables by vaccination cohort and outcome.

Principal components 1 and 2 (PC1 and PC2), along which the antibody immune responses have the largest variance (n = 39 AV, n = 33 PV, including n = 24 infected, n = 48 uninfected vaccinees).

Combined immune correlate analysis of the gB/MF59 vaccine

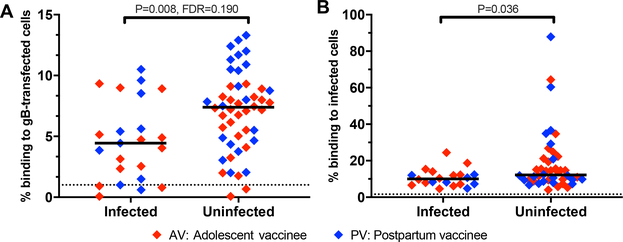

To identify immune correlates of protection for the gB/MF59 vaccine, we performed a univariate logistic regression for CMV infection status in the clinical trial follow-up period. This analysis was performed across 23 measured vaccine-elicited humoral immune responses, excluding heterologous virus neutralization because this response was poorly elicited in PV. We adjusted for the vaccination cohort and performed Benjamini-Hochberg correction with an a priori significance cut-off of < 0.2, as applied in an immune correlate analysis of the HIV vaccine RV144 trial (25). By logistic regression analysis, we found that only IgG binding to gB-transfected cells correlated with decreased risk of CMV acquisition (P = 0.008, FDR = 0.190. Table 1, Fig. 5A). This immune response remained significantly associated with reduced risk of infection after adjustment for cohort, timepoint, and subject age (P = 0.003, FDR = 0.080, table S4). When assessed in the AV and PV cohorts independently, this immune response maintained a trend towards statistical significance (P = 0.11 in AV, P = 0.053 in PV, by Mann Whitney U).

Table 1. In gB/MF59 vaccinees, IgG binding to cell-associated gB was identified as the only humoral immune correlate of protection from CMV acquisition.

Logistic regression analysis on 23 measured vaccine-elicited antibody responses (blue), excluding heterologous neutralization responses and adjusted for vaccination cohort, by univariate logistic regression analysis to determine P and FDR, which was calculated with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. CMV-infected cell binding was measured as a follow-up assay to the primary univariate logistic regression analysis. To calculate receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curves, LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) regression analysis was performed for parameter selection.

| Assay | P | FDR | For primary analysis, included in univariate logistic regression | Selected by LASSO regression analysis for inclusion in ROC modeling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | gB-transfected cell IgG binding (% binding) | 0.008 | 0.190 | + | + |

| 2 | gB immunogen IgG binding (LogMFI) | 0.04 | 0.307 | + | − |

| 3 | gB AD-4 + AD-5 IgG binding (LogMFI) | 0.04 | 0.307 | + | − |

| 4 | gB ectodomain IgG binding (LogMFI) | 0.058 | 0.334 | + | − |

| 5 | ADCP of AD169r-GFP (% phagocytosis) | 0.115 | 0.385 | + | + |

| 6 | ADCP of TB40/E (% phagocytosis) | 0.122 | 0.385 | + | + |

| 7 | gB AD-4 IgG binding (LogMFI) | 0.135 | 0.385 | + | + |

| 8 | gB immunogen IgG binding (Log AUC) | 0.146 | 0.385 | + | + |

| 9 | gB-specific IgG1 subclass (LogMFI) | 0.151 | 0.385 | + | − |

| 10 | gB AD-5 IgG binding (LogMFI) | 0.169 | 0.389 | + | + |

| 11 | Whole virion (TB40/E) IgG avidity (RAI) | 0.205 | 0.395 | + | + |

| 12 | FcγR3a V158 binding to gB-specific IgG (LogMFI) | 0.206 | 0.395 | + | − |

| 13 | FcγR1a binding to gB-specific IgG (LogMFI) | 0.294 | 0.507 | + | + |

| 14 | FcγR2b binding to gB-specific IgG (LogMFI) | 0.309 | 0.507 | + | − |

| 15 | Whole virion (TB40/E) IgG binding (LogAUC) | 0.354 | 0.513 | + | + |

| 16 | FcγR2a H131 binding to gB-specific IgG (LogMFI) | 0.357 | 0.513 | + | − |

| 17 | gB IgG avidity (RAI) | 0.451 | 0.610 | + | + |

| 18 | gB AD-1 IgG binding (LogMFI) | 0.529 | 0.677 | + | + |

| 19 | gB-specific IgG3 subclass (LogMFI) | 0.559 | 0.677 | + | + |

| 20 | Neutralization of Towne virus on MRC-5 (LogID50) | 0.728 | 0.837 | + | + |

| 21 | gB-specific IgG2 subclass (LogMFI) | 0.809 | 0.887 | + | + |

| 22 | gB-specific IgG4 subclass (LogMFI) | 0.93 | 0.948 | + | + |

| 23 | gB AD-2 Site 1 IgG binding (LogMFI) | 0.948 | 0.948 | + | + |

| 24 | CMV-infected cell IgG binding | − | − | − | + |

Fig. 5. Immune correlates of protection of primary CMV acquisition elicited by the gB/MF59 vaccine.

(A) Frequency of IgG binding to gB-transfected HEK293T cells by flow cytometry. Dotted line indicates the threshold for gB-transfected cell IgG binding, as defined by the average of CMV-seronegative samples run simultaneously (n = 11) + 2x the standard deviation. Median % binding to gB-transfected cells is indicated (n = 23 infected vaccinees, n = 48 uninfected vaccinees). Statistical significance was determined by univariate logistic regression analysis with Benjamini-Hochberg correction. (B) Frequency of IgG binding to MRC-5 fibroblasts infected with TB40/E strain virus, measured by flow cytometry. Dotted line indicates the threshold for CMV-infected cell binding by the average of CMV-seronegative samples run simultaneously (n = 8) + 2x the standard deviation. Median % binding to CMV-infected cells is indicated (n = 20 infected vaccinees, n = 44 uninfected vaccinees). Statistical significance was determined by Mann Whitney U test.

We anticipated that IgG binding to cell-associated gB was a surrogate measure for an antibody function that was protective against primary CMV infection, such as neutralization or ADCP. However, this IgG binding response was not significantly associated with any functional antibody response measured in our study (fig. S4). We then explored whether this binding response was a surrogate for IgG binding to CMV-infected cells. In a follow-up experiment, IgG binding to CMV-infected cells was associated with protection in both cohorts (P = 0.036. Fig. 5B, fig. S5), but this measure did not correlate with the magnitude of IgG binding to gB-transfected cells (fig. S4).

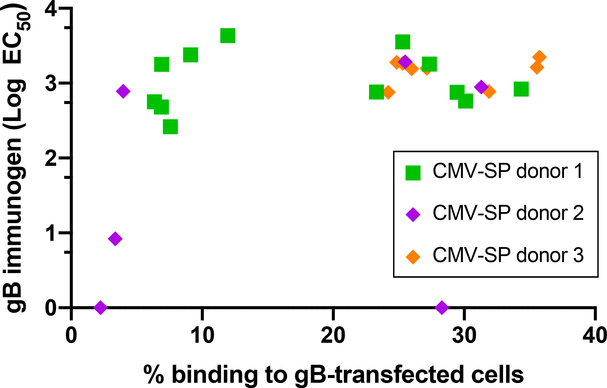

We aimed to validate that IgG recognition of gB-transfected cells was distinct from that of the soluble gB immunogen. We hypothesized that soluble gB and cell-associated gB have unique structures and therefore unique epitopes available for antibody binding. Accordingly, we anticipated that only a subset of gB-specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) would recognize both cell-associated gB and soluble gB. Using gB-specific mAbs isolated from three naturally CMV-infected individuals, we compared the binding strength of the mAbs to soluble and cell-associated gB. We found that most of these gB-specific mAbs exhibited relatively similar magnitude binding to soluble gB, but they had a bimodal distribution of IgG binding to gB-transfected cells (Fig. 6 and fig. S6A, B). These results indicated that cell-associated gB and soluble gB have unique structures resulting in distinct epitope accessibility, which are detectable at the mAb level.

Fig. 6. CMV gB-specific mAbs isolated from naturally CMV-infected individuals bind with similar strength to full-length gB yet bind with a bimodal distribution to cell-associated gB.

Binding by gB-specific mAbs (5 μg/mL) to gB-transfected cells, measured by flow cytometry, as compared to binding to full-length gB, measured by ELISA. n = 26 anti-gB mAbs recombinantly produced from gB-specific memory B cells isolated from three naturally infected CMV-seropositive (SP) individuals. Samples were run in duplicate.

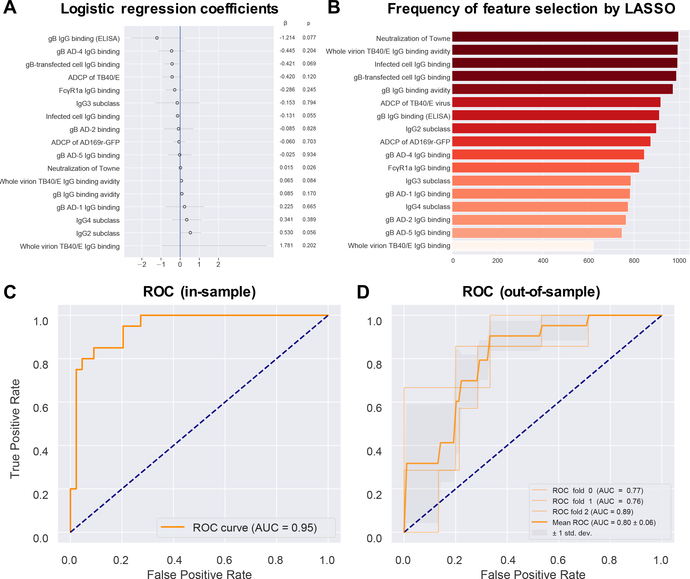

Finally, we built a predictive model of CMV infection outcomes using a subset of measured immune responses. We first removed variables that were highly correlated with one another because these can result in numerical instability and are essentially the weighted sum of the dependent variables. To remove the redundant variables, we set a threshold for the variance inflation factor (VIF) of <10. VIF is a generalization of the correlation for more than two variables (26). When models have many predictors, as in our study, the data may be over-fitted, resulting in a model that is more complex than warranted given the data. Overfitting and excess complexity can result in poor generalization. We thus selected 17 of the 24 possible variables to include in the regression analysis by least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) (Fig. 7A, Table 1). LASSO is a strategy to penalize model complexity by setting the coefficients of weakly informative variables to zero, effectively removing variables from the model and permitting automatic feature selection (26).To evaluate the features of variables selected by LASSO, we constructed 1,000 bootstrapped samples (i.e. sampled with replacement) and performed 1,000 regressions on these bootstrapped samples. IgG binding to gB-transfected and infected cells, as well as autologous Towne strain neutralization and whole virion TB40/E IgG binding avidity, had non-zero correlations in >95% of these bootstrap LASSO regressions (Fig. 7B), indicating a high consistency for selection by LASSO. Using only the 17 LASSO-selected variables, we calculated an receiver-operator-characteristic (ROC) curve that was moderately predictive of CMV infection in gB/MF59 vaccines (AUC = 0.80 ± 0.06 for out-of-sample testing) (Fig. 7C, D).

Fig. 7. To predict the infection outcome of combined vaccine cohorts, in-sample and out-of-sample receiver operator characteristic curves for a penalized multiple logistic regression model were generated using humoral immunogenicity features.

(A) Logistic regression coefficients from a LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) regression analysis. LASSO regression analysis was performed to generate the feature coefficients and was run after exclusion of heterologous neutralization results and collinear variables [variance inflation factor (VIF) > 10]. (B) Frequency of feature selection by LASSO techniques, which was applied to 1000 bootstrapped samples to evaluate the robustness of feature selection. Stability selection plot indicates the number of times that each feature had non-zero coefficients from performing LASSO on each bootstrapped sample. (C) Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve for in-sample data and the corresponding area under the curve (AUC), with 1 indicating perfect discriminatory value and 0.5 or less indicating no discriminatory value. (D) ROC curves and the corresponding AUCs for out-of-sample data. Out-of-sample results were obtained by 3-fold stratified cross-validation, including a nested cross-validation within each fold for selection of the inverse regularization strength hyperparameter. ROC ± 1 SD are displayed.

Discussion

This study reveals an immune correlate of protection for the most efficacious CMV vaccine candidate trialed to-date. We compared 32 gB/MF59 vaccine-elicited humoral immune responses in adolescent and postpartum cohorts and identified differences in vaccine-elicited immune responses between cohorts. In particular, heterologous virus neutralization responses were higher in the adolescent cohort. The immune correlate analysis in the combined cohort identified that serum IgG binding to cell-associated gB, but not to the soluble vaccine immunogen or CMV-neutralizing responses, was associated with protection. Moreover, we identified gB-specific mAbs that differentially bind to cell-associated conformations of gB despite equivalent binding to soluble gB. These findings indicated that antibodies recognize distinct epitopes on cell-associated and soluble gB and that cell surface epitopes of gB may more closely represent those present on viral particles, wherein gB is in its native conformation as a fusogenic protein for CMV. Therefore, a cell-associated conformation of gB may be important for eliciting protective gB-specific antibodies, a finding with a major implication for future CMV gB vaccine design.

CMV gB mediates membrane fusion for viral entry and is thought to exist in two distinct conformations: prefusion and postfusion. The crystal structure of the soluble trimeric postfusion gB used in the gB/MF59 vaccine has been described (27, 28). However, the prefusion structure of gB, which has fusogenic function on viral particles and is therefore potentially more relevant to the induction of protective antibodies (29), remains to be determined. Our results suggested that transient transfection of human cells with full-length gB-encoding mRNA can be used to present gB in a structural form that is distinct from that of soluble gB and contains unique epitopes for gB antibodies that are associated with protection. Thus, we hypothesize that the conformation of gB on the surface of transfected cells is likely to be similar to that found on the surface of virions, with a majority in the prefusion conformation and a smaller fraction in the postfusion conformation (30). The stabilization of cell-associated gB or its macromolecular complex might represent a strategy to define the prefusion gB structure. Supporting this, the gB mRNA used in this assay encodes the full-length gB, including major regions that are expected to undergo large-scale refolding during the prefusion-to-postfusion transition, structural Domain III (also known as the core domain) and Domain V located at the N terminus (27). By contrast, the soluble gB used in the gB/MF59 vaccine studies is primarily monomeric and may not adequately mimic either the prefusion or postfusion state (31). Our data showed that gB-specific mAbs with equivalent, high binding to soluble gB have distinct abilities to bind to cell-associated gB, suggesting that a subset of epitopes are available for antibody binding on cell-associated gB compared to soluble gB. Our results further support that the prefusion gB structure is worth pursuing, because it is likely directly relevant to development of an efficacious gB-based CMV vaccine.

In the adolescent and postpartum populations, the gB/MF59 vaccine conferred similar rates of protection against CMV primary infection but elicited unique antibody profiles in each cohort. We investigated the relationship between vaccine-elicited antibody responses and the subject characteristics of each cohort. We found that heterologous virus neutralization responses inversely correlated with subject age. The human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine, HPV-16/18 and AS04 adjuvant, also elicits higher titers of classical neutralizing antibodies against HPV-16 and HPV-18 in adolescent girls compared to young women (32, 33), suggesting that there are distinct immune landscapes in these age groups.

Despite these age differences, in our study the variance in neutralization was better explained by vaccination cohort, indicating that factors other than age, such as recent pregnancy, contribute to vaccine immunogenicity. Pregnancy is characterized by immunological changes that include downregulation of Th1 (cellular) immune responses and upregulation of Th2 (humoral) immune responses, along with aspects of exaggerated inflammation (34). Indeed, some effects of pregnancy on T, B, and Natural Killer (NK) lymphocyte subset frequencies and function may persist as long as one year after the birth (35–38). Previous studies have described increased frequencies in circulating naïve B cells and regulatory B cells in postpartum mothers compared to those in nonpregnant women, which may suggest that the postpartum state is one of lymphopoiesis recovery and B cell activation (38). In our study, one of the inclusion criteria for the postpartum cohort was delivery of a newborn infant within the prior 12 months. Thus, there may have been differences between the immune repertoires of the postpartum and nulliparous adolescent subjects that underlie the unique vaccine-elicited antibody profiles in each cohort. Our results identified differences in vaccine-elicited immune responses between these cohorts that require further study and consideration in future CMV vaccine trial design.

The function mediated by cell-associated gB IgG engagement as an immune correlate of protection from CMV acquisition remains to be identified. In our study, the neutralizing and non-neutralizing functions ADCC and ADCP did not predict CMV acquisition risk and did not strongly correlate with IgG binding to cell-associated gB. Furthermore, heterologous virus neutralization was elicited in AV, but not PV; however, this response did not confer additional vaccine efficacy. Thus, our study indicated that, although neutralization is the most common immunologic endpoint used in viral vaccine development, this may not be a comprehensive measure to assess experimental CMV vaccines.

There are limitations to our study. This study focused on vaccine immunogenicity at single timepoint, but the timing and duration of anti-CMV responses are important in other contexts, including congenital transmission and posttransplant (39, 40). gB has five highly homologous genotypes, and whether the gB/MF59 vaccine conferred genotype-specific protection remains unclear (41, 42). Our study focused on anti-gB IgG sera responses, but the immune recognition of other CMV glycoproteins, such as the CMV gH/gL/gO trimer and pentameric complex that generate potently neutralizing responses, and IgA responses may also contribute to protection (43). Indeed, this immune correlate may be one of many relevant to developing an efficacious vaccine, and future studies should also investigate the cellular immune responses and immune correlates of other CMV vaccine antigens. Furthermore, although this study has implicated IgG binding to cell-associated gB in defense against primary infection, its role against secondary infection or reactivation has yet to be studied.

Limitations also exist for the statistical methods applied. Our univariate regression analysis indicated that IgG binding to cell-associated gB is positively associated with protection, but it cannot identify a specific binding threshold correlated with protection. Furthermore, the ROC curves generated from a select subset of measured immune responses had only moderate predictive ability. However, as a hypothesis-generating study, these results provide future directions for assays that can measure a threshold for protection against CMV infection.

Our study indicated that vaccine-elicited IgG binding to gB-transfected cells is an important immunologic endpoint for vaccine development and evaluation. This response could serve as a surrogate for an antibody-mediated antiviral function. Immunologic endpoints with established relationships to CMV acquisition will aid in vaccine evaluation in preclinical and early phase clinical trials and should continue to be evaluated in ongoing late phase CMV vaccine development.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The primary objective of our research study was to define the humoral immune responses elicited by the CMV gB/MF59 vaccine that protected against primary infection in two historical cohorts of adolescent and postpartum vaccinees. This study utilized biobanked samples from a total of 24 vaccinees who acquired infection during the course of the gB/MF59 phase II clinical trial matched 1:2 to 48 vaccinees who remained uninfected from the AV (n = 39) and PV (n = 33) cohorts. The cohort size was determined based on sample availability and confirmed to be sufficient based on a power calculation for neutralization responses. In serum from AV and PV, we measured 32 total CMV- and gB-specific serum IgG binding responses, Fc region properties, and neutralizing and non-neutralizing functions against Towne and heterologous CMV strains. All responses were measured in duplicate, except for the gB linear epitope IgG binding responses, which were run in triplicate. Researchers who performed the assays were blinded to the infection status of the vaccinees. Statistician Cliburn Chan performed the immune correlate analysis, at which point the researchers were unblinded. To identify if there were cohort-specific differences in vaccine immunogenicity, we assessed the IgG responses in AV and PV by PCA and compared their responses by Mann Whitney U tests. Using data from the AV and PV cohorts, we performed immune correlate regression analyses to define the immune responses associated with protection from primary CMV infection in two distinct populations (“immune correlate of protection”). We subsequently performed subgroup analyses in each AV and PV cohort to validate the identified immune correlate of protection. For the secondary analysis, we performed predictive modeling on the same dataset. To do so, we used a VIF cutoff < 10 to remove colinear features then LASSO logistic regression analysis for variable selection and regularization. The stability of LASSO-selected variables was evaluated on 1,000 bootstrapped samples, generating out-of-sample ROC curves using stratified 3-fold cross-validation. For all analyses, neutralization titer and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) variables were log-transformed to normalize the distribution of the data. Primary data are reported in the Supplementary Materials (data file S1).

Study population

The study population included AV and PV who participated in two historical prospective Phase II, randomized, double-blind placebo controlled clinical trials of an CMV gB subunit protein (Sanofi Pasteur) with MF59 adjuvant (Novartis) vaccine (table S1) (17, 18). Trial participants were CMV-seronegative women vaccinated with gB/MF59 on an identical schedule of 0, 1, and 6 months and followed for seroconversion to non-vaccine CMV antigens for 2 years in AV and 3 years in PV. The current study utilized biobanked samples from 24 gB/MF59 vaccinees (13 adolescent, 11 postpartum) who were infected with CMV during follow-up and who were 1:2 matched based on race and number of vaccine doses to 48 vaccinees (26 adolescent, 22 postpartum) who remained uninfected. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained for the PV and AV cohorts from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, respectively. All subjects signed an approved consent form. The Duke IRB determined that the analysis of de-identified sera samples did not meet the definition of human subjects. All sera assayed were obtained prior to CMV infection, as confirmed by the absence of serum binding to CMV pentameric glycoprotein complex. Samples were drawn at peak immunogenicity, which was one month after the third vaccine dose for AV and two weeks after the third dose for PV (17, 18). For the 8 PV subjects lacking available samples at this timepoint, we assayed available sera drawn three months (n = 4) or six months (n = 4) after the third dose. Missing assay results were only due to low sample volume. Based on the hypothesis that neutralization titers would be lower in the 24 infected vaccinees compared to the 48 uninfected vaccinees, this study had 80% power to measure a 1.6-fold difference in neutralization titer between the groups at the two-sided alpha 0.05 level by t test.

IgG binding and avidity measurement by ELISA

To measure the magnitude of the gB-specific and CMV-specific sera IgG response, 384-well ELISA plates were coated overnight at 4°C with 30ng gB or 33 PFU TB40/E-mCherry per well then blocked in assay diluent (1× PBS pH 7.4 containing 4% whey, 15% normal goat serum, and 0.5% Tween-20). Sera were plated in an 8-point 3-fold serial dilution starting at a dilution of 1:40, in duplicate. mAbs were plated in an 8-point 3-fold dilution starting at a concentration of 5 μg/mL, in duplicate. Binding was detected by goat-anti human HRP-conjugated IgG secondary (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Plates were develop using the SureBlue Reserve tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) peroxidase substrate (KPL). Data are reported as log10 AUC (area under the curve) values for the area under the sigmoidal sera dilution versus the optical density (OD) curve. AUC was selected because some sera samples did not demonstrate full sigmoidal binding curves, complicating determination of an ED50. Antibody avidity was measured by treatment of duplicate wells with 7M or 1× PBS for 5 minutes after sera incubation. Sera dilutions that resulted in an OD value between 0.6 and 1.2 with PBS treatment (dilution range = 1:30 – 1:1000) were used to determine the relative avidity index (RAI). RAI was calculated as the OD ratio of urea-treated to PBS-treated wells.

gB linear peptide microarray

A PepStar multiwell array (JPT Peptide) was coated 15-mer synthesized peptides covering the open reading frame of Towne strain gB with overlapping peptides of 10 residues (for a total of 180 peptides), plated in triplicate. Per manufacturer’s instructions, arrays were first blocked with blocking buffer (PBS pH 7.4 with 1% milk blotto, 5% normal goat serum, and 0.05% Tween-20) for 1.5 hours. Then, vaccinee sera diluted at 1:250 in blocking buffer were incubated for 1.5 hours, and anti-human IgG conjugated to AF647 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted in blocking buffer (0.75 μg/mL) was added for 45 minutes. Between incubation steps, arrays were washed 5× in wash buffer (1× Tris-buffered saline (TBS) buffer + 0.1% Tween) with an automated plate washer (BioTec ELX50). In the final wash, arrays were washed 2× with 0.1× saline sodium citrate (SSC) buffer, then plates were dried by centrifugation in 50 mL conical tubes. Arrays were scanned in an Axon Genepix 4300 scanner (Molecular Devices) at a photomultiplier tubes (PMT) setting of 580 and 100% laser power. Images were analyzed using Genepix Pro 7 software (Molecular Devices) for peptide identification and fluorescence intensity. Correct peptide identification was confirmed manually. The median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each of the 3 replicates on the array was reported as binding intensity of sera to each peptide with subtraction of surrounding background fluorescence (data file S8).

Antigen-specific IgG binding measurement by binding antibody multiplex assay (BAMA)

Binding of IgG specific to gB, gB epitopes, and pentameric complex (PC) were measured as previously described (44). Carboxylated fluorescent beads (Luminex) were covalently coupled to purified CMV antigens then incubated with sera in assay diluent (PBS pH 7.4, 5% normal goat serum, 0.05% Tween-20, and 1% blotto milk). IgG binding to gB (Sanofi-Pasteur), gB AD-5, gB AD-4 + AD-5, and PC at a 1:50 sera dilution and peptides gB AD-1 (myBiosource), biotinylated linear gB AD-2 (biotin-NETIYNTTLKYGD), and gB AD-4 at a 1:500 sera dilution. These dilutions were previously determined as within the linear range of the assay. IgG specific to CMV glycoproteins were detected with goat anti-human IgG conjugated to PE (2 μg/mL, Southern Biotech). Beads were washed, and fluorescence was acquired on a Bio-Plex 200 (Bio-Rad), and results were expressed as MFI. Blank beads were used in all assays to measure nonspecific binding, and inter-assay variation was tracked by serial dilution of CMV hyperimmunoglobulin (Cytogam) and charting of Levy-Jennings curves ((45)). Samples were reported if they met preset assay criteria: bead counts of ≥ 100 for each sample and a coefficient of variation per sera duplicate of ≤ 20% for each sample. Background sera binding was calculated by performing the assay with CMV-seronegative sera from vaccinees prior to gB/MF59 vaccination. The threshold for positivity of BAMA was defined as the mean value of CMV-seronegative, pre-vaccine control sera (n = 28) + 2× standard deviation.

gB-specific IgG subclass characterization

IgG subclass distribution of gB-specific IgG in sera was measured by BAMA as previously described (44). For measurement of IgG1, sera were diluted 1:500, and for measurement of IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4, sera were diluted 1:40. Sera were then co-incubated with gB covalently coupled to Luminex beads. In separate assays for each IgG subclass, binding was detected by biotin-conjugated subclass-specific antibodies at a concentration of 4 μg/mL: IgG1-biotin (BD Pharmingen; clone G17–1), IgG2-biotin (BD Pharmingen; G18–21), IgG3-biotin (Calbiochem; clone HP6047), and IgG4-biotin (BD Pharmingen; clone G17–4). The plates were washed, then binding was detected by addition of phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated streptavidin (2 μg/mL, Southern Biotech). Data acquisition, data analysis, and quality control criteria were as described above for BAMA. The lower limit of positivity was defined as 100.

IgG Fc receptor binding characterization

FcR binding by gB-specific IgG in vaccinee serum was measured by BAMA as previously described (44). Sera were diluted 1:500 then coincubated with gB covalently coupled to Luminex beads. In separate assays for each FcR, FcR binding to sera IgG was detected by biotin-conjugated IgG-specific FcR at a concentration of 0.5 μg/mL: FcγR1a, FcγR2a (clone H131), FcγR2b, and FcγR3a (clone V158). All FcγR were produced at the Duke Protein Production Facility. The plates were washed, then binding was detected by addition of PE-conjugated streptavidin (2 μg/mL, Southern Biotech). Data acquisition, data analysis, and quality control criteria were as described above for BAMA. The lower limit of positivity was defined as 100.

gB-transfected cell binding

HEK293T cells at 50% confluency in a T75 flask were cotransfected using the Effectine Transfection Reagent (Qiagen) with DNA plasmids expressing GFP (gift of Maria Blasi, Duke University) with or without plasmids expressing the full-length gB ORF from the autologous Towne strain (SinoBiological). After incubation for 2 days at 37°C and 5% CO2, transfected cells were washed with Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS) pH 7.4 (Gibco) then removed from the flask by gently rinsing with Trypsin-EDTA 0.05% with phenol red (ThermoFisher). Cells were resuspended in wash buffer [DPBS pH 7.4 + 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS)] then enumerated for count and viability using a Muse Count and Viability kit (Millipore). Cells were plated in 96-well V-bottom plates (Corning) at 100,000 live cells/well, then centrifuged at 1200g for 5 minutes. Supernatant was discarded. Cells were co-incubated with sera at point dilutions of 1:6250 dilution, gB mAbs at 5 μg/mL, or gB mAbs in serial dilution (8-point 3-fold dilution starting at 120 μg/mL) in duplicate for 2 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were washed and resuspended in live/dead Aqua cell stain (ThermoFisher) diluted to 1:1000 for 20 minutes incubation at room temperature. Cells were washed then coincubated with PE-conjugated mouse anti-human IgG Fc (Southern Biotech) diluted to 1:200 for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed twice and fixed with 1% formalin for 15 minutes. Cells were washed twice then resuspended in PBS pH 7.4. Events were immediately acquired on an LSR II (BD Biosciences) using the high-throughput sampler (HTS). The % PE-positive cells was calculated from the live, GFP-positive cell population and reported as the average for each sample run in duplicate. For sera, the threshold for PE detection was defined at 99% of the binding of three CMV-seronegative samples. The threshold for positivity was defined as the average of CMV-seronegative samples (n = 10) + 2 standard deviations. For mAbs, the threshold for PE positivity was defined as 99% of the binding of Zika mAb at 5 μg/mL.

CMV-infected cell binding

MRC-5 fibroblasts were grown to ~50% confluency in a T175 flask, then infected with TB40/E-mCherry at MOI of 2.0 at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 2 hours. Media was changed, then cell-cell spread of infection was allowed to proceed for 46 hours. Infected cells were washed with DPBS pH 7.4 (Gibco) then gently dissociated by rinsing with Trypsin-EDTA 0.05% with phenol red (ThermoFisher). Cells were enumerated with a Muse Count and Viability kit (Millipore) then washed and resuspended at 106 viable cells/mL. Cells were stained with live/dead Aqua (ThermoFisher) diluted to 1:1000 for 20 minutes incubation at room temperature then fixed in 10% formalin for 10 minutes at room temperature. After two washes, cells were plated in 96-well V-bottom plates (Corning) at 20,000 live cells per well, then pelleted by centrifugation at 1200g for 5 minutes. After supernatant was discarded, cells were resuspended in sera diluted to 1:1250 in cell media in duplicate and incubated for 2 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were washed then stained with goat anti-human IgG (Abcam) at 1:200 in PBS pH 7.4 + 1% FBS for 25 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then washed and resuspended in PBS pH 7.4. Events were acquired on an LSR II (BD Biosciences) using the HTS. The % IgG binding to infected cells was calculated from the % FITC-positive cells of the live, mCherry-positive singlet population and reported for each sample. The cutoff for sample positivity was defined as the mean value of CMV-seronegative controls (n = 8) + 2 standard deviations.

Neutralization

Neutralization by patient sera was measured by high-throughput Cellomics bioimaging and fluorescence as previously described (22). In brief, BJ-5Ta fibroblasts, MRC-5 fibroblasts, or ARPE epithelial cells were seeded in 384-well clear, flat-bottom plates then incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 until ~80% confluent. Human CMV strains Towne, AD169r-GFP, or TB40/E virus strains at an MOI = 1.0 were co-incubated with vaccinee sera in 3-fold serial dilution (1:10 to 1:30,000) in respective cell media for a total volume of 50 μL for 2 hours at 37°C. For complement neutralization assays, rabbit complement (CedarLane) was added in a 1:2 ratio to cell media prior to diluting sera + virus in the cell media (46). Cells were co-incubated with sera + virus for 42–48 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2, then fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Plates that had been infected with Towne or TB40/E virus were stained with mouse anti-human CMV IE1 (MAB810, Millipore) then goat anti-mouse IgG-AF488 (Millipore). Nuclear staining was performed in all plates by DRAQ5 (ThermoFischer Scientific). Plates were imaged using a Cellomics fluorescent reader to determine the percentage of infected cells per well. For each vaccinee, the 50% inhibitory dilution (ID50) of serum was determined according to the Reed and Muench method comparing the serum dilution resulting in a 50% reduction in fluorescence signal to control wells infected with virus only. In each assay, complement-mediated enhancement of neutralization was calculated per vaccinee by Wilcoxon paired signed rank test, with a significance value defined as p < 0.05.

Antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) of whole CMV virions

Concentrated, sucrose gradient-purified TB40/E-mCherry virus or AD169r-GFP was conjugated to fluorochrome AF647 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, approximately 107 plaque forming units (PFUs) of whole virus was buffer exchanged with PBS to a final volume of 100 μL using a 100,000 kDa Amicon filter (Millipore). Virus was transferred to an opaque centrifuge tube, then 10 μg AF647 NHS ester reconstituted in DMSO and 20 μL of 1 M sodium bicarbonate were added. This reaction mixture was co-incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with constant agitation then quenched with 80 μL of 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Labelled virus was diluted 25× in wash buffer (PBS pH 7.4 + 0.1% FBS) then plated at 10 μL per well in a 96-well round-bottom plate. Sera samples diluted 1:10 in PBS were added in duplicate. Sera and virus were co-incubated at 37°C for 2 hours, then 25,000 THP-1 cells (ATCC) in 200 μL growth media were added to each well. In a spinoculation step, plates were centrifuged at 1200g at 4°C for 1 hour, then incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Cells were transferred to a 96-well V-bottom plate, then washed twice and fixed in DPBS pH 7.4 + 1% formalin. Events were acquired on an LSR II (BD Biosciences) using the HTS. The % of AF647-positive cells was calculated from the full THP-1 cell population. The cutoff for sample positivity was defined as the mean value of CMV-seronegative controls (n = 6 for AD169r-GFP, n = 3 for TB40/E) + 2 standard deviations.

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)

Natural killer (NK) cell degranulation was measured by cell-surface abundance of CD107a (47). ARPE cells were plated at 3 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plate, then after 24-hour incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, cells were infected with TB40/E-mCherry at an MOI of 1.0 for 48 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Infected cells were washed with R10 media (RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, 100mM HEPES (Invitrogen), 100 μM Gentamicin (Invitrogen), and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin-Glutamine (Invitrogen)) before addition of primary human NK cells. Primary NK cells were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) by negative magnetic separation (Human NK cell isolation kit, Miltenyi Biotech) after overnight rest in R10 media with 10 ng/mL IL-15 (Miltenyi Biotech). To each well of ARPE-19 cell monolayers, 5 × 104 NK cells were added with sera samples at 1:25 dilution or mAbs at 25 μg/mL in R10, plated in duplicate. Brefeldin A (GolgiPlug, 1 μl/ml, BD Biosciences), monensin (GolgiStop, 4μl/6mL, BD Biosciences), and CD107a-FITC (BD Biosciences, clone H4A3) were added to each well and co-incubated for 6 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. NK cells were then gently resuspended, while avoiding disturbance of the ARPE-19 cell monolayer, then NK cells were collected and transferred to 96-well V-bottom plates. NK cells were washed with PBS pH 7.4 then resuspended in live/dead Aqua dead cell stain (ThermoFisher) diluted to 1:1000 for 20-minute incubation at room temperature. Cells were washed with PBS + 1% FBS and stained with the following antibodies in PBS + 1% FBS for 20 minutes at room temperature: CD56-PECy7 (BD Biosciences, clone NCAM16.2), CD16 PacBlue (BD Biosciences, clone 3G8), and CD69-BV785 (BioLegend, Clone FN50). Cells were washed again then fixed and permeabilized for 20 minutes at 4°C with the BD Fixation/Permeabilization solution, then washed with BD Perm/Wash, and stained for intracellular interferon (IFN)-γ-BV711 (BioLegend, clone 4S.B3) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF)-α BV650 (BD Biosciences, clone Mab11) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed twice then resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde fixative. Events were acquired on a BD LSR Fortessa and data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (v9.9.6). Data are reported as the % of CD107a-positive live NK cells (singlets, lymphocytes, aqua blue–, CD16+, CD107+). The threshold for positivity is defined as the mean of CMV-seronegative, pre-vaccinated controls (n = 39) + 2 standard deviations.

Statistical Analysis

To identify differences in vaccine immunogenicity in PV and AV, the cohorts were first compared across antibody binding or functional responses by Mann-Whitney U t test, with an a priori statistical significance defined as P < 0.05 with a two-tailed test. The cohorts were then compared by PCA across 24 antibody features, excluding heterologous virus neutralization due to negligible responses in PV and including the 23 features measured for the primary analysis and the follow-up assay measuring infected cell IgG binding. A univariate dendrogram for immune responses measured was created and ranked by Pearson correlation coefficient. Full results from significance tests, including confidence intervals, are provided in table S2.

For the primary analysis, immune correlates of protection of CMV infection were identified by univariate logistic regression across 23 measured immune responses, excluding heterologous virus neutralization and infected cell IgG binding, which was measured in a follow-up assay to the primary analysis, and were adjusted for cohort only or cohort, timepoint sampled, and subject age. A priori statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 with a two-tailed test and Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.2, as applied in an immune correlate analysis of the HIV vaccine RV144 trial (25). Missing data were not imputed, and outliers were not excluded. For the secondary analysis, we performed predictive modeling on the same dataset using VIF cutoff < 10 to remove colinear features, followed by LASSO logistic regression analysis for variable selection and regularization. Cross-validation, a resampling procedure that evaluates a machine learning model on a limited data sample set in order to estimate the accuracy of the model on new data, was used to optimize the inverse regularization strength parameter, which applies a sparsity-inducing penalty to large magnitude coefficients to reduce overfitting the model to the data. We used stratified 3-fold cross-validation to evaluate the out-of-sample receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) curves. The stability of LASSO-selected variables was evaluated on 1000 bootstrapped samples and the frequency with which each variable was selected by the LASSO procedure reported. For all analyses, neutralization titer and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) variables were log-transformed to normalize the distribution of the data

Univariate tests and PCA analysis were conducted using the R language and environment for statistical computing version 3.51, and penalized multiple logistic regression was conducted using Python 3.7 and scikit-learn version 0.21.2. Reproducible Jupyter notebooks for all analysis performed are provided (data files S4, S6).

Supplementary Material

Data File S7. CMV Pentameric Complex IgG binding.xlsx

Data File S9. CMV gB-specific mAb binding.xlsx

Data File S8. CMV gB linear peptide array binding by sera IgG from AV.xlsx

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis Plan

Fig. S1. Gating strategy for measurement of gB/MF59 vaccine-elicited IgG binding to gB-transfected cells.

Fig. S2. Sera IgG binding to gB linear epitopes in AV following gB/MF59 immunization.

Fig. S3. CMV-specific ADCC responses were poorly elicited by gB/MF59 vaccination in adolescent vaccinees.

Fig. S4. Univariate dendrogram of gB/MF59 vaccine-elicited humoral immune responses.

Fig. S5. Vaccine-elicited IgG binding to CMV-infected cells.

Fig. S6. gB-specific mAb binding to soluble gB and gB-transfected cells.

Table S1. Characteristics of gB/MF59 trial vaccinees and the sample timepoints available for the immune correlate study.

Table S2. Comparison of vaccine-elicited immune responses in adolescent and postpartum cohorts by Mann Whitney U test.

Table S3. Linear regression of neutralization responses.

Table S4. Humoral immune correlate of CMV acquisition risk of gB/MF59 vaccinees with adjustment for cohort, timepoint sampled, and subject age.

Data File S6. Analysis in Python.ipynb

Data File S3. Analysis in R.html

Data File S5. Analysis in Python.html

Data File S2. stats_stability.csv

Data File S1. Compiled gBMF59 dataset.xlsx

Data File S4. Analysis in R.ipynb

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to acknowledge Sanofi Pasteur, Merck, Trellis Biosciences, Dr. Thomas E. Shenk, and Dr. Nathaniel J. Moorman for the generous gift of research materials and the Duke Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Units for their assistance in study coordination. Furthermore, we would like to thank the subjects who participated in these clinical trials and clinical and research staff at the participating sites. Editorial services were provided by Nancy R. Gough (BioSerendipity, LLC, Elkridge, MD).

Funding: This work was supported by NIH/NIAID R21 to S.R.P. (R21AI136556), NIH/NIAID P01 to S.R.P. (1P01AI129859), NIH/NICHD F30 grant to C.S.N. (F30HD089577), and Medearis CMV Scholars Program to J.A.J. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, decision to publish, or the preparation of this manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Data and materials availability:

The complete immunogenicity datasets and reproducible Jupyter notebooks for all analysis performed are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

References

- 1.Manicklal S, Emery VC, Lazzarotto T, Boppana SB, Gupta RK, The “silent” global burden of congenital cytomegalovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev 26, 86–102 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramanan P, Razonable RR, Cytomegalovirus infections in solid organ transplantation: a review. Infect Chemother 45, 260–271 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson J, Anderson B, Pass RF, Prevention of maternal and congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Clin Obstet Gynecol 55, 521–530 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fowler KB et al. , The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N Engl J Med 326, 663–667 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boppana SB, Pass RF, Britt WJ, Stagno S, Alford CA, Symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus infection: neonatal morbidity and mortality. Pediatr Infect Dis J 11, 93–99 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.in Vaccines for the 21st Century: A Tool for Decisionmaking, Stratton KR, Durch JS, Lawrence RS, Eds. (Washington (DC), 2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schleiss MR, Searching for a Serological Correlate of Protection for a CMV Vaccine. J Infect Dis 217, 1861–1864 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto AY et al. , Congenital cytomegalovirus infection as a cause of sensorineural hearing loss in a highly immune population. Pediatr Infect Dis J 30, 1043–1046 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boppana SB, Rivera LB, Fowler KB, Mach M, Britt WJ, Intrauterine transmission of cytomegalovirus to infants of women with preconceptional immunity. N Engl J Med 344, 1366–1371 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderholm KM, Bierle CJ, Schleiss MR, Cytomegalovirus Vaccines: Current Status and Future Prospects. Drugs 76, 1625–1645 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plotkin SA, Gilbert PB, Nomenclature for immune correlates of protection after vaccination. Clin Infect Dis 54, 1615–1617 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin L, Gilbert PB, Corey L, McElrath MJ, Self SG, A framework for assessing immunological correlates of protection in vaccine trials. J Infect Dis 196, 1304–1312 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isaacson MK, Compton T, Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B is required for virus entry and cell-to-cell spread but not for virion attachment, assembly, or egress. J Virol 83, 3891–3903 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper RS, Heldwein EE, Herpesvirus gB: A Finely Tuned Fusion Machine. Viruses 7, 6552–6569 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Britt WJ, Vugler L, Butfiloski EJ, Stephens EB, Cell surface expression of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) gp55–116 (gB): use of HCMV-recombinant vaccinia virus-infected cells in analysis of the human neutralizing antibody response. J Virol 64, 1079–1085 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Speckner A, Glykofrydes D, Ohlin M, Mach M, Antigenic domain 1 of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B induces a multitude of different antibodies which, when combined, results in incomplete virus neutralization. J Gen Virol 80 (Pt 8), 2183–2191 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein DI et al. , Safety and efficacy of a cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B (gB) vaccine in adolescent girls: A randomized clinical trial. Vaccine 34, 313–319 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pass RF et al. , Vaccine prevention of maternal cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med 360, 1191–1199 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pass RF et al. , A subunit cytomegalovirus vaccine based on recombinant envelope glycoprotein B and a new adjuvant. J Infect Dis 180, 970–975 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baraniak I et al. , Protection from cytomegalovirus viremia following glycoprotein B vaccination is not dependent on neutralizing antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 6273–6278 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths PD et al. , Cytomegalovirus glycoprotein-B vaccine with MF59 adjuvant in transplant recipients: a phase 2 randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 377, 1256–1263 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson CS et al. , HCMV glycoprotein B subunit vaccine efficacy mediated by nonneutralizing antibody effector functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 6267–6272 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrante A, Beard LJ, Feldman RG, IgG subclass distribution of antibodies to bacterial and viral antigens. Pediatr Infect Dis J 9, S16–24 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes JM, Wormald MR, Rudd PM, Davey GP, Fc gamma receptors: glycobiology and therapeutic prospects. J Inflamm Res 9, 209–219 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haynes BF et al. , Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med 366, 1275–1286 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tibshirani R, Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. J Roy Stat Soc B Met 58, 267–288 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke HG, Heldwein EE, Correction: Crystal Structure of the Human Cytomegalovirus Glycoprotein B. PLoS Pathog 11, e1005300 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chandramouli S et al. , Structure of HCMV glycoprotein B in the postfusion conformation bound to a neutralizing human antibody. Nat Commun 6, 8176 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schleiss MR, Recombinant cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B vaccine: Rethinking the immunological basis of protection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, 6110–6112 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Si Z et al. , Different functional states of fusion protein gB revealed on human cytomegalovirus by cryo electron tomography with Volta phase plate. PLoS Pathog 14, e1007452 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui X et al. , Novel trimeric human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B elicits a high-titer neutralizing antibody response. Vaccine 36, 5580–5590 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petaja T et al. , Long-term persistence of systemic and mucosal immune response to HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in preteen/adolescent girls and young women. Int J Cancer 129, 2147–2157 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Block SL et al. , Comparison of the immunogenicity and reactogenicity of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in male and female adolescents and young adult women. Pediatrics 118, 2135–2145 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Challis JR et al. , Inflammation and pregnancy. Reprod Sci 16, 206–215 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe M et al. , Changes in T, B, and NK lymphocyte subsets during and after normal pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol 37, 368–377 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wegienka G et al. , Within-woman change in regulatory T cells from pregnancy to the postpartum period. J Reprod Immunol 88, 58–65 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le Gars M et al. , Pregnancy-Induced Alterations in NK Cell Phenotype and Function. Front Immunol 10, 2469 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lima J et al. , Characterization of B cells in healthy pregnant women from late pregnancy to post-partum: a prospective observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16, 139 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lilleri D et al. , Fetal human cytomegalovirus transmission correlates with delayed maternal antibodies to gH/gL/pUL128–130-131 complex during primary infection. PLoS One 8, e59863 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baraniak I et al. , Epitope-Specific Humoral Responses to Human Cytomegalovirus Glycoprotein-B Vaccine With MF59: Anti-AD2 Levels Correlate With Protection From Viremia. J Infect Dis 217, 1907–1917 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson CS et al. , Intrahost Dynamics of Human Cytomegalovirus Variants Acquired by Seronegative Glycoprotein B Vaccinees. J Virol 93, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murthy S et al. , Detection of a single identical cytomegalovirus (CMV) strain in recently seroconverted young women. PLoS One 6, e15949 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu TM, An Z, Wang D, Progress on pursuit of human cytomegalovirus vaccines for prevention of congenital infection and disease. Vaccine 32, 2525–2533 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bialas KM et al. , Maternal Antibody Responses and Nonprimary Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection of HIV-1-Exposed Infants. J Infect Dis 214, 1916–1923 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levey S, Jennings ER, The use of control charts in the clinical laboratory. 1950. Arch Pathol Lab Med 116, 791–798; discussion 799–803 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li F et al. , Complement enhances in vitro neutralizing potency of antibodies to human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B (gB) and immune sera induced by gB/MF59 vaccination. NPJ Vaccines 2, 36 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alter G, Malenfant JM, Altfeld M, CD107a as a functional marker for the identification of natural killer cell activity. J Immunol Methods 294, 15–22 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liao HX et al. , Initial antibodies binding to HIV-1 gp41 in acutely infected subjects are polyreactive and highly mutated. J Exp Med 208, 2237–2249 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xia L et al. , Active evolution of memory B-cells specific to viral gH/gL/pUL128/130/131 pentameric complex in healthy subjects with silent human cytomegalovirus infection. Oncotarget 8, 73654–73669 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data File S7. CMV Pentameric Complex IgG binding.xlsx

Data File S9. CMV gB-specific mAb binding.xlsx

Data File S8. CMV gB linear peptide array binding by sera IgG from AV.xlsx

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis Plan

Fig. S1. Gating strategy for measurement of gB/MF59 vaccine-elicited IgG binding to gB-transfected cells.

Fig. S2. Sera IgG binding to gB linear epitopes in AV following gB/MF59 immunization.

Fig. S3. CMV-specific ADCC responses were poorly elicited by gB/MF59 vaccination in adolescent vaccinees.

Fig. S4. Univariate dendrogram of gB/MF59 vaccine-elicited humoral immune responses.

Fig. S5. Vaccine-elicited IgG binding to CMV-infected cells.

Fig. S6. gB-specific mAb binding to soluble gB and gB-transfected cells.

Table S1. Characteristics of gB/MF59 trial vaccinees and the sample timepoints available for the immune correlate study.

Table S2. Comparison of vaccine-elicited immune responses in adolescent and postpartum cohorts by Mann Whitney U test.

Table S3. Linear regression of neutralization responses.

Table S4. Humoral immune correlate of CMV acquisition risk of gB/MF59 vaccinees with adjustment for cohort, timepoint sampled, and subject age.

Data File S6. Analysis in Python.ipynb

Data File S3. Analysis in R.html

Data File S5. Analysis in Python.html

Data File S2. stats_stability.csv

Data File S1. Compiled gBMF59 dataset.xlsx

Data File S4. Analysis in R.ipynb

Data Availability Statement

The complete immunogenicity datasets and reproducible Jupyter notebooks for all analysis performed are provided in the Supplementary Materials.