Abstract

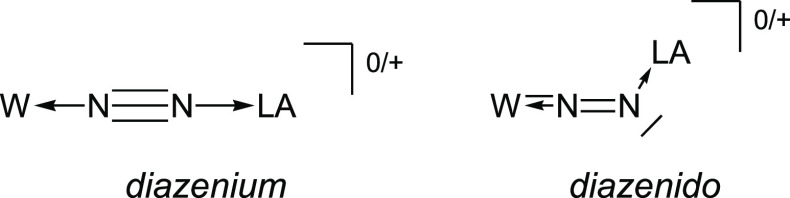

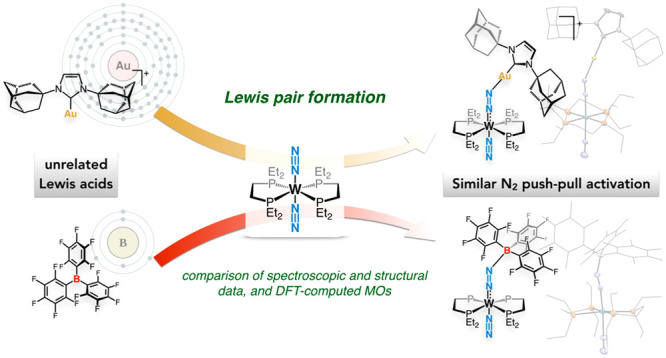

We have prepared and characterized a series of unprecedented group 6–group 11, N2-bridged, heterobimetallic [ML4(η1-N2)(μ-η1:η1-N2)Au(NHC)]+ complexes (M = Mo, W, L2 = diphosphine) by treatment of trans-[ML4(N2)2] with a cationic gold(I) complex [Au(NHC)]+. The adducts are very labile in solution and in the solid, especially in the case of molybdenum, and decomposition pathways are likely initiated by electron transfers from the zerovalent group 6 atom to gold. Spectroscopic and structural parameters point to the fact that the gold adducts are very similar to Lewis pairs formed out of strong main-group Lewis acids (LA) and low-valent, end-on dinitrogen complexes, with a bent M–N–N–Au motif. To verify how far the analogy goes, we computed the electronic structures of [W(depe)2(η1-N2)(μ-η1:η1-N2)AuNHC]+ (10W+) and [W(depe)2(η1-N2)(μ-η1:η1-N2)B(C6F5)3] (11W). A careful analysis of the frontier orbitals of both compounds shows that a filled orbital resulting from the combination of the π* orbital of the bridging N2 with a d orbital of the group 6 metal overlaps in 10W+ with an empty sd hybrid orbital at gold, whereas in 11W with an sp3 hybrid orbital at boron. The bent N–N–LA arrangement maximizes these interactions, providing a similar level of N2 “push–pull” activation in the two compounds. In the gold case, the HOMO–2 orbital is further delocalized to the empty carbenic p orbital, and an NBO analysis suggests an important electrostatic component in the μ-N2–[Au(NHC)]+ bond.

Short abstract

Dinitrogen-bridged group 6−gold(I) heterobimetallic complexes have been prepared and characterized. The extent of push−pull activation of the bridiging N2 ligand has been measured according to spectroscopic and structural parameters. A similarity with adducts of group 6 dinitrogen complexes with the B(C6F5)3 Lewis acid (LA) has been observed. Computationnal studies have shown that the bent N−N−LA motifs arise from interaction with π* orbitals of N2. In the gold case, d orbitals and electrostatic forces are involved in N−Au bonding.

Introduction

Activation of dinitrogen through its binding to a transition or f-block metal has attracted constant attention from coordination and organometallic chemists for more than 50 years.1 Beyond the inherent challenge posed by the high stability of the N2 molecule, investigations on dinitrogen activation have been motivated by the quest for sustainable anthropogenic nitrogen fixation methods that could potentially replace the Haber–Bosch process.2 In this perspective, the nitrogen-fixing enzymes, the nitrogenases,3 have inspired chemists as they allow dinitrogen reduction to take place under ordinary pressure and temperature thanks to binding and stepwise reduction of N2 at an iron-containing active site. The understanding of the nitrogenases’ mechanism has been in continual progression, but the complexity of the enzyme coupled to the difficulty of its study during substrate consumption leaves the whole mechanistic picture partly speculative. Yet, since the advent of the 2000s, many synthetic N2-to-NH3 catalysts based on transition metals (TMs) have been devised.4 Thanks to in-depth mechanistic investigations made possible by the relative simplicity of the catalytic systems, the design of improved catalysts has recently led to high turnover numbers.5 In the vast majority of homogeneous nitrogen fixation systems (including the nitrogenases), the N2 molecule is proposed to bind an in situ-generated low-valent metal complex in an end-on fashion as the first step prior to its protonation. When steric hindrance of the ligand sphere allows it, the diatomic N2 molecule can bridge two metals with μ-η1:η1 hapticity, resulting in homobimetallic complexes. N2-bridged heterobimetallic complexes of the transition elements are more scarcely encountered among the literature and only a handful have been completely characterized. Generally, the synthesis of μ-η1:η1-N2-bridged heterobimetallic complexes has been aimed at devising original reactivities for the N2 ligand since in such a coordination environment, dinitrogen may be polarized to an extent that is not reached with other coordination modes as a result of “push–pull” activation.6 Starting from a mononuclear end-on dinitrogen complex, two synthetic approaches can be envisioned to prepare a N2-bridged heterobimetallic compound, and both take advantage of the basicity imparted to the terminal nitrogen atom of the N2 ligand upon coordination: (i) formation of a Lewis acid–base adduct with a Lewis acidic TM complex and (ii) halide substitution at a high valent TM complex (Scheme 1). The team of Chatt has systematically investigated the coordination of various early d-block Lewis acids through dative bonding with the terminal N of the N2 ligand of trans-[ReCl(N2)(PMe2Ph)4] and recorded more or less important bathochromic shifts of the ν(N2) elongation frequency in IR spectroscopy.7 The enhanced N2 activation was rationalized according to a push–pull effect, and its magnitude was correlated to the electronic configuration of the acceptor metal. Sellmann et al. have reported the isolation of [Cp(CO)2Mn–(μ-N2)–Cr(CO)5] from the reaction of [CpMn(CO)2N2] with [Cr(CO)5(THF)].8 Later, the team of Hidai synthesized a series of heterobimetallic N2-bridged complexes by taking advantage of the nucleophilic nature of the N2 ligand in Mo0 and W0 dinitrogen complexes, which substitutes a chloride ligand in high-valent organometallic compounds of groups 4 and 5.9 The group of Seymore has characterized an adduct of the trans-[ReCl(N2)(PMe2Ph)4] compound with a cationic MoIV complex while studying heterolytic N2 splitting.10 As far as late transition metal acceptors are concerned, stable heterobimetallic complexes were obtained by the formation of Lewis pairs between a low-valent Mo, Re, or Fe dinitrogen complex and an electrophilic FeII complex.11 All but one11b,11c of these structurally characterized N2-bridged complexes show a linear M–N≡N–M′ arrangement as a result of d orbitals mixing with the π molecular orbitals (MOs) of N2.

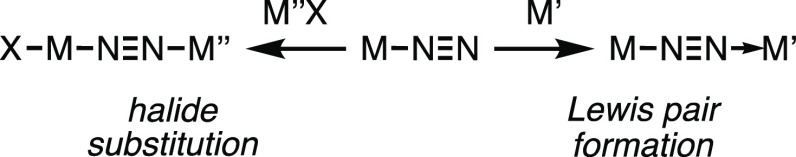

Scheme 1. Syntheses of N2-Bridged Heterobimetallic Complexes.

The formation of B(C6F5)3 (1) adducts with trans-[M(dppe)2(N2)2] [M = Mo, 2Mo, M = W, 2W, dppe = 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane] and [Fe(depe)2(N2)] [depe = 1,2-bis(diethylphosphino)ethane] has been reported by us12 and the team of Szymczak,11e respectively. Characterization of these adducts revealed that N2 activation became significant upon coordination to the strong boron Lewis acid (LA), with a bent N–N–B motif. The Szymczak group rationalized the push–pull effect with the help of DFT calculations and showed that the boron vacant orbital interacts with a π* one of the N2 ligand, resulting in a bent structure. Interestingly, these combinations of dinitrogen complexes with main group LA13 have shown unprecedented reactivities toward N2 protonation11e or functionalization.12 We now wish to extend this N2 complex–LA cooperation paradigm and would like to report herein our studies regarding the formation of stable adducts between zerovalent group 6 dinitrogen complexes and cationic gold(I) complexes. With the purpose of exploiting the reactivity of cationic gold(I) compounds toward unsaturated organic molecules14 for N2 functionalization (which turned out to be unproductive), we have, as an interdependent study, examined how AuI and Mo0 or W0 complexes interact in the condensed phase. We wanted to answer the following questions: are undesirable redox events likely to occur, and if not, would gold coordinate to the N2 ligand and how? As mentioned above, reactions of early to-mid LA-TMs with N2 complexes have been explored thoroughly and mainly resulted in the formation of adducts. By contrast, and to the best of our knowledge, nothing is known with late, beyond group 8 LA–TMs, with the exception of CuII and AgI salts, which have been reported to quantitatively oxidize the ReI–N2 complex trans-[ReCl(N2)(PMe2Ph)4].7a Structural, theoretical, and stability data are thus desirable for who wishes to exploit the reactivity of late TMs for the cooperative activation of N2. Moreover, the isolobal relationship existing between Au+ and H+15 makes the putative adducts relevant models to assess the effect of acidic residues on ligating N2 within the active site of the nitrogenases and would come to complement the studies carried out by the Szymczak group,11e,16 whereas the paucity of reports of stable, genuine gold–N2 complexes in the literature17 provides further incentive to such investigations. Finally, the above-mentioned B(C6F5)3-dinitrogen complexes can be well viewed as mixed metal/main group frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs)18 activating the N2 molecule. Replacing boron with gold would introduce an “all-metal” FLP system19 for N2 activation.20,21 In this Article, we wish to report on the synthesis and structural, spectroscopic, and electronic characterization of [M–N≡N–Au]+ adducts of AuI cations bearing N-heterocyclic carbene ligands (NHC) with group 6 (Mo, W) N2 complexes.

Experimental Section

Computational Details

Calculations were carried out using the Gaussian 09 package22 at the DFT level by means of the hybrid density functional B3PW91.23 Polarized all-electron double-ζ 6-31G(d,p) basis sets were used for H, C, N, P, B, and F atoms. For the W and Au atoms, the Stuttgart–Dresden pseudopotentials were used in combination with their associated basis sets24 augmented by a set of polarization functions (f-orbital polarization exponents of 0.823 and 1.05 for the W and Au atoms, respectively).25 The nature of the optimized stationary point has been verified by means of analytical frequency calculation at 298.15 K and 1 atm. The geometry optimizations have been achieved without any geometrical constraints and include dispersion with the D3 version of Grimme’s dispersion with Becke–Johnson damping.26 Energy data are reported in the gas phase. The electron density and partial charge distribution were examined in terms of localized electron-pair bonding units using the NBO program.27

General Considerations

All reactions were performed in flame- or oven-dried glassware with rigorous exclusion of air and moisture, using a nitrogen filled Jacomex glovebox (O2 < 0.5 ppm, H2O < 1 ppm). Solvents used were predried (toluene and n-pentane by passing through a Puresolv MD 7 solvent purification machine; n-hexane and hexamethyldisiloxane (HMDSO) by distillation over CaH2), degassed by freeze–pump–thaw cycles, dried over molecular sieves, and stored in the glovebox. C6D6, C6D5Cl, and THF-d8 (purchased from Eurisotop) were degassed by freeze–pump–thaw cycles, dried over molecular sieves, and stored in the glovebox. The Mo/W dinitrogen complexes 2M–4M,2815N–3W,28 [Au(NTf2)(Me2Idipp)] (6bNTf2),29 and B(C6F5)3 (1)30 were prepared according to reported procedures and stored in the glovebox. The [Au(Cl)(NHC)] complexes 6a–eCl, dimethylphenylphosphine (PMe2Ph), 1,2-bis(diphenylphosphino)ethane (dppe), 1,2-bis(diethylphosphino)ethane (depe), and NaB(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4 were purchased from TCI, Sigma-Aldrich, or Strem Chemicals and used as received. 1H, 11B, 13C, 19F, and 31P NMR spectra were recorded using NMR tubes equipped with J. Young valves on a Bruker Avance III 400 spectrometer. Chemical shifts are in parts per million (ppm) downfield from tetramethylsilane and are referenced to the most upfield residual solvent resonance as the internal standard (C6HD5: δ reported = 7.16 ppm; C6HD4Cl: δ reported = 6.96 ppm; THF-d7: δ reported = 1.72 ppm for 1H NMR; C6D5Cl: δ reported = 125.96 ppm for 13C NMR). 11B, 19F, and 31P NMR spectra were calibrated according to the IUPAC recommendation using a unified chemical shift scale based on the proton resonance of tetramethylsilane as primary reference.31 Data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (br = broad, s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, p = quintet, hept = heptuplet, m = multiplet), coupling constant (Hz), and integration. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded in a nitrogen filled Jacomex glovebox (O2 < 0.5 ppm, H2O < 1 ppm) on an Agilent Cary 630 FT-IR spectrophotometer equipped with ATR or transmission modules and are reported in wavenumbers (cm–1) with (s) indicating strong absorption. Elemental analyses were performed on samples sealed in tin capsules under Ar or N2 by the Analytical Service of the Laboratoire de Chimie de Coordination; results are the average of two independent measurements.

Spectroscopic Characterization of [W(dppe)2(N2)(μ-N2)Au(Idipp)][B(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4] (7aWBArF)

NMR characterization: C6D5Cl (0.5 mL) was added at room temperature to a vial containing [Au(Cl)(Idipp)] (7.4 mg, 12 μmol), NaB(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4 (10.6 mg, 12 μmol, 1 equiv), and [W(dppe)2(N2)2] (2W, 12.4 mg, 12 μmol, 1 equiv). The deep orange suspension was then stirred vigorously for 5 min during which the mixture turned to a dark red solution upon formation of the gold adduct. The mixture was then immediately transferred to an NMR tube equipped with a J. Young valve and analyzed via NMR spectroscopy. IR characterization: the same process was conducted with C6H5Cl and transferred into an IR transmission cell for measurement of the N2 ligand region (2400–1600 cm–1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 8.27 (br, 8H, o-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 7.61 (br, 4H, p-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 7.42 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, p-Ar dipp), 7.20 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H, m-Ar dipp), 7.14–7.04 (m, 8H, Ar dppe), 7.04–6.91 (m, 16H, Ar dppe), 6.87–6.78 (m, 10H, Ar dppe, CH imidazole), 6.67 (br, 8H, Ar dppe), 2.38 (hept, J = 7.0 Hz, 4H, CH(CH3)2), 2.28 (br, 4H, CH2CH2 dppe), 1.98 (br, 4H, CH2CH2 dppe), 1.10 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 24H, CH(CH3)2) ppm. 11B NMR (128 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −6.0 ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 166.8 (C carbene), 162.5 (q, JCF = 49.9 Hz, o-C, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 145.6 (CAr dipp), 136.7 (t, JCP = 9.3 Hz, Aripso dppe), 135.3 (br s, o-C, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 135.0 (t, JCP = 9.1 Hz, Aripso dppe), 133.7 (CAr dipp), 132.8 (t, JCP = 2.7 Hz, o-Ar dppe), 132.1 (t, JCP = 2.4 Hz, o-Ar dppe), 131.3 (CHAr dipp), 129.8 (m, o-C, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 129.4 (s, p-Ar dppe), 128.3 (s, p-Ar dppe), 128.2 (hidden, p-Ar dppe), 125.0 (q, JCF = 272.4 Hz, CF3), 124.6 (CHAr dipp), 124.2 (C(CH3) imidazole), 117.8 (br, p-C, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 31.1–30.5 (m, CH2CH2 dppe), 28.9 (CH(CH3)2), 24.6 (CH(CH3)2), 23.6 (CH(CH3)2) ppm. 19F NMR (376 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −62.0 ppm. 31P NMR (162 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 45.5 (JPW = 306.1 Hz) ppm. IR (C6H5Cl, 2400–1600 cm–1 range), ν/cm–1: 2085 (N2), 1851 (μ-N2).

Spectroscopic Characterization of [W(dppe)2(N2)(μ-N2)Au(Me2Idipp)][B(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4] (7bWBArF)

C6D5Cl (0.5 mL) was added at room temperature to a vial containing [Au(Cl)(Me2Idipp)] (7.8 mg, 12 μmol), NaB(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4 (10.6 mg, 12 μmol), and [W(dppe)2(N2)2] (2W, 12.4 mg, 12 μmol). The deep orange suspension was then stirred vigorously for 5 min during which the mixture turned to a dark purple solution upon formation of the gold adduct. The mixture was then immediately transferred to an NMR tube equipped with a J. Young valve and analyzed via NMR spectroscopy. FTIR characterization: the same process was conducted with C6H5Cl and transferred into an IR transmission cell for measurement of the N2 ligand region (2400–1600 cm–1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 8.26 (br, 8H, o-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 7.61 (br, 4H, p-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 7.41 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, p-Ar dipp), 7.27–7.10 (m, 8H, m-Ar dipp, Ar dppe), 7.10–6.91 (m, 20H, Ar dppe), 6.86 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 8H, Ar dppe), 6.62 (br, 8H, Ar dppe), 2.36–2.20 (m, 8H, iPr dipp, CH2CH2 dppe), 1.96 (br, 4H, CH2CH2 dppe), 1.61 (s, 6H, Me imidazole), 1.10 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 12H, iPr dipp), 1.07 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 12H, iPr dipp) ppm. 11B NMR (128 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −6.0 ppm. 13C NMR (100 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 162.5 (C carbene), 162.5 (q, JCF = 49.6 Hz, o-C, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 146.0 (CAr dipp), 137.3 (t, JCP = 9.8 Hz, Aripso dppe), 135.3 (br s, o-C, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 134.9 (t, JCP = 9.8 Hz, Aripso dppe), 133.0 (t, JCP = 2.7 Hz, o-Ar dppe), 132.1 (CAr dipp), 132.1 (t, JCP = 2.7 Hz, o-Ar dppe), 131.2 (CHAr dipp), 129.6–129.7 (m, o-C, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 129.3 (s, p-Ar dppe), 128.4–128.2 (hidden, p-Ar dppe), 127.6 (C(CH3) imidazole), 124.6 (CHAr dipp), 125.0 (q, JCF = 272.5 Hz, CF3), 117.8 (br, p-C, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 31.0 (t, JCP = 10.7 Hz, CH2CH2 dppe), 28.8 (CH(CH3)2), 25.2 (CH(CH3)2), 23.1 (CH(CH3)2), 9.1 (C(CH3) Imidazole) ppm. 19F NMR (376 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −62.1 ppm. 31P NMR (162 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 46.2 (JPW = 307.4 Hz) ppm. IR (C6H5Cl, 2400–1600 cm–1 range), ν/cm–1: 2085 (N2), 1851 (μ-N2).

General Method for the Preparation of [W(depe)2(N2)(μ-N2)Au(NHC)][B(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4] Adducts (10b–eWBArF)

PhF (1.5 mL) was added at room temperature to a vial containing [Au(Cl)(NHC)] (46 μmol), NaB(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4 (41 mg, 46 μmol), and [W(depe)2(N2)2] (3W, 30 mg, 46 μmol). The red suspension was then stirred vigorously for 5 min, during which the mixture turned to a purple (10bWBArF) or dark red (10c–eWBArF) solution upon formation of the adducts. The mixture was then poured in precooled pentane (15 mL, −40 °C) and stored overnight at −40 °C to induce the precipitation of purple or dark red mixtures of the adduct and NaCl recovered by decantation. The fine NaCl powder was then stirred up and removed with pentane washes (3 × 5 mL) to recover the complexes as red or purple crystals after brief drying under a N2 stream.

[W(depe)2(N2)(μ-N2)Au(Me2Idipp)][B(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4] (10bWBArF)

Recovered as a purple microcrystalline powder (78 mg, R = 80%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 8.26 (br, 8H, o-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 7.62 (br, 4H, p-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 7.26 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, p-Ar dipp), 7.08 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H, m-Ar dipp), 2.27 (hept, J = 6.9 Hz, 4H, iPr dipp), 1.71–1.47 (m, 16H, PCH2CH3), 1.59 (s, 6H, Me imidazole), 1.23–1.05 (m, 8H, CH2CH2 depe), 1.20 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 12H, iPr dipp), 1.09 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 12H, iPr dipp), 0.89 (m, 12H, PCH2CH3), 0.74 (m, 12H, PCH2CH3). 11B NMR (128 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −6.1 ppm. 19F NMR (376 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −62.1 ppm. 31P NMR (162 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 34.2 (JPW = 296.2 Hz) ppm. IR (C6H5Cl, 2400–1600 cm–1 range), ν/cm–1: 2044 (N2), 1796 (μ-N2). IR (ATR, powder), ν/cm–1: 2960, 2936, 2065(s, N2), 1763(s, μ-N2), 1647, 1610, 1595, 1495, 1461, 1416, 1395, 1353(s), 1279(s), 1218, 1165, 1117(s), 1092, 1060, 1043, 887, 867, 839, 805, 785, 753, 716, 682, 668. Elem. anal. calcd. for C81H100AuBF24N6P4W (%): C, 45.69; H, 4.73; N, 3.95. Found: C, 45.46; H, 4.73; N, 3.35.

[W(depe)2(N2)(μ-N2)Au(IMes)][B(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4] (10cWBArF)

Recovered as a dark red microcrystalline powder (75 mg, R = 85%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 8.26 (br, 8H, o-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 7.62 (br, 4H, p-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 6.81 (s, 4H, Ar Mes), 6.57 (s, 2H, CH imidazole), 2.30 (s, 6H, Me Mes), 2.01–1.82 (m, 8H, PCH2CH3), 1.87 (s, 12H, Me Mes), 1.80–1.48 (m, 14H, PCH2CH3, PCH2CH3), 1.13–1.05 (m, 8H, CH2CH2 depe), 1.05–0.91 (m, 12H, PCH2CH3), 0.81–0.72 (m, 6H, PCH2CH3). 11B NMR (128 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −6.0 ppm. 19F NMR (376 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −62.1 ppm. 31P NMR (162 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 32.6 (JPW = 283.8 Hz) ppm. IR (C6H5Cl, 2400–1600 cm–1 range), ν/cm–1: 2052 (N2), 1767 (μ-N2). IR (ATR, powder), ν/cm–1: 2969, 2938, 2885, 2057 (s, N2), 1741 (s, μ-N2), 1610, 1487, 1458, 1416, 1377, 1352 (s), 1271 (s), 1161, 1118 (s), 1029, 980, 931, 885, 868, 852, 839, 804, 744, 715, 682, 668 (s). Elem. anal. calcd. for C73H84AuBF24N6P4W (%): C, 43.47; H, 4.20; N, 4.17. Found: C, 43.21; H, 4.07; N, 3.21.

[W(depe)2(N2)(μ-N2)Au(ItBu)][B(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4] (10dWBArF)

Recovered as small dark red crystals (69 mg, R = 81%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 8.25 (br, 8H, o-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 7.62 (br, 4H, p-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 6.64 (s, 2H, CH imidazole), 2.54–2.40 (m, 2H, PCH2CH3), 2.17–2.01 (m, 4H, PCH2CH3), 1.96–1.81 (m, 4H, PCH2CH3), 1.73–1.18 (m, 18H, PCH2CH3, PCH2CH3), 1.57 (s, 18H, tBu), 1.18–1.01 (m, 17H, CH2CH2 depe, PCH2CH3, PCH2CH3), 1.00–0.88 (m, 3H, PCH2CH3). 11B NMR (128 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −6.1 ppm. 19F NMR (376 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −62.1 ppm. 31P NMR (162 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 34.4 (JPW = 284.6 Hz) ppm. IR (C6H5Cl, 2400–1600 cm–1 range), ν/cm–1: 2050 (N2), 1775 (μ-N2). IR (ATR, powder), ν/cm–1: 2970, 2937, 2881, 2063 (s, N2), 1726 (s, μ-N2), 1609, 1487, 1459, 1409, 1379, 1351(s), 1272(s), 1212, 1158, 1116(s), 1037, 898, 885, 866, 838, 805, 744, 710, 681(s), 667(s). Elem. anal. calcd. for C63H80AuBF24N6P4W (%): C, 39.98; H, 4.26; N, 4.44. Found: C, 39.56; H, 4.19; N, 3.53.

[W(depe)2(N2)(μ-N2)Au(IAd)][B(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4] (10eWBArF)

Recovered as dark brown crystals (78 mg, R = 83%). This method allowed the recovery of crystals fit for X-ray diffraction analysis. 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 8.24 (br, 8H, o-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 7.61 (br, 4H, p-H, C6H3-3,5-(CF3)2), 6.78 (s, 1H, CH imidazole), 6.72 (s, 1H, CH imidazole), 2.53–2.22 (m, 6H, Ad), 2.17 (s, 8H, Ad), 2.12–1.83 (m, 14H, PCH2CH3, Ad), 1.83–1.66 (m, 8H, PCH2CH3, PCH2CH3), 1.66–1.45 (m, 14H, Ad, PCH2CH3), 1.43–1.27 (m, 6H, PCH2CH3), 1.15–0.88 (m, 22H, PCH2CH3, CH2CH2 depe, Ad). 11B NMR (128 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −6.1 ppm. 19F NMR (376 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −62.1 ppm. 31P NMR (162 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ 34.6 (JPW = 295.3 Hz) ppm. IR (C6H5Cl, 2400–1600 cm–1 range), ν/cm–1: 2048 (N2), 1783 (μ-N2). IR (ATR, powder), ν/cm–1: 2915, 2859, 2048 (N2), 1762 (s, μ-N2), 1610, 1457, 1353 (s), 1274 (s), 1160, 1122 (s), 1038, 1027, 899, 887, 867, 839, 807, 744, 724, 716, 693, 682(s), 669(s). Elem. anal. calcd. for C75H92AuBF24N6P4W (%): C, 43.96; H, 4.53; N, 4.10. Found: C, 43.40; H, 4.63; N, 3.17. [W(depe)2(15N2)(μ-15N2)Au(IAd)][B(C6H3-3,5-{CF3}2)4] (15N-10eWBArF). 15N NMR (60 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −40.1 (s, 1N, μ-Nα), −42.9 (s, 1N, Nβ), −76.1 (s, 1N, Nα), −119.0 (s, 1N, μ-Nβ) ppm. 31P{1H}/183W HMQC-NMR (25 MHz, C6D5Cl): δ −2031.1 ppm. IR (ATR, powder), ν/cm–1: 2914, 1977 (N2), 1703 (s, μ-N2), 1458, 1352 (s), 1303, 1274 (s), 1197, 1161, 1122 (s), 1104, 1038, 1027, 930, 899, 887, 866, 838, 807, 755, 743, 724, 715, 710, 693, 681 (s), 668 (s), 607.

Preparation of [Mo(depe)2(N2)(μ-N2)B(C6F5)3)] (11Mo)

Toluene (0.6 mL) was added to a 10 mL flask containing trans-[Mo(depe)2(N2)2] (3Mo, 34 mg, 60 μmol, 1.0 equiv) and B(C6F5)3 (1, 31 mg, 60 μmol, 1.0 equiv). After stirring for 10 min at room temperature, the orange-brown mixture was filtered, layered slowly with pentane (6 mL), and stored at −40 °C. After 2 days, orange crystals of 11Mo were recovered and dried under a vacuum (34 mg, 53% yield). Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained from the same crop. 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6): δ 1.76–1.28 (m, 17H), 1.17 (m, 6H), 1.03–0.83 (m, 13H), 0.83–0.69 (m, 10H), 0.67–0.55 (m, 1H), 0.53–0.41 (m, 1H) ppm. 11B NMR (128 MHz, C6D6): δ −10.1 ppm. 19F NMR (376.5 MHz, C6D6), maj (84%): δ −131.9 (d, J = 21.6 Hz, 2F), −158.7 (t, J = 20.4 Hz, 1F), −164.4 (t, J = 18.2 Hz, 2F) ppm. 19F NMR (376.5 MHz, C6D6), min (16%): δ −132.3 (d, J = 19.5 Hz, 2F), −159.5 (t, J = 20.7 Hz, 1F), −165.0 (t, J = 19.1 Hz, 2F) ppm. 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, C6D6): δ 53.0 ppm. IR (ATR), ν/cm–1: 2965, 2939, 2909, 2881, 2120 (N2), 1789 (μ-N2), 1642, 1512, 1461, 1379, 1279, 1081, 1028, 973, 867, 802, 748, 735, 674, 666, 603, 522. Elem. anal. calcd. for C38H48BF15MoN4P4 (%): C, 42.40; H, 4.49; N, 5.20. Found: C, 42.60; H, 4.25; N, 4.47.

Preparation of [W(depe)2(N2)(μ-N2)B(C6F5)3)] (11W)

Toluene (1.5 mL) was added to a 10 mL flask containing trans-[W(depe)2(N2)2] (3W, 65 mg, 100 μmol, 1.0 equiv) and B(C6F5)3 (1, 51 mg, 100 μmol, 1.0 equiv). After stirring for 10 min at room temperature, the orange-brown mixture was filtered, layered slowly with pentane (10 mL), and stored at −40 °C. After 1 week, purple crystals of 11W were recovered and dried under a vacuum (72 mg, 62% yield). Single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained from the same crop. 1H NMR (400 MHz, toluene-d8): δ 1.67–1.28 (m, 20H), 1.22–1.08 (br, 4H), 0.94–0.84 (m, 12H), 0.84–0.70 (m, 12H) ppm. 11B NMR (128 MHz, C6D6): δ −11.1 ppm. 19F NMR (377 MHz, toluene-d8): δ −132.0 (d, J = 23.8 Hz, 6F), −159.1 (t, J = 20.7 Hz, 3F), −164.6 (td, J = 22.8, 7.4 Hz, 6F) ppm. 31P{1H} NMR (162 MHz, C6D6): δ 34.7 (JPW = 294 Hz) ppm. IR (ATR), ν/cm–1: 2967, 2934, 2910, 2076 (N2), 1767 (μ-N2), 1641, 1512, 1461, 1378, 1279, 1081, 1028, 973, 868, 802, 749, 693, 675, 612, 525. Elem. anal. calcd. for C38H48BF15WN4P4 (%): C, 39.20; H, 4.16; N, 4.81. Found: C, 39.59; H, 4.09; N, 4.08. [W(depe)2(15N2)(μ-15N2)B(C6F5)3)] (15N-11W). The preparation is identical to that for 11W. 15N NMR (60 MHz, C6D6): δ −37.4 (s, 1N, Nβ), −55.0 (s, 1N, μ-Nα), −73.9 (s, 1N, Nα), −152.6 (s, 1N, μ-Nβ) ppm. 31P{1H}/183W HMQC-NMR (25 MHz, C6D6): δ −1914.2 ppm. IR (ATR), ν/cm–1: 2007 (N2), 1767 (μ-N2), 1641, 1512, 1461, 1378, 1279, 1081, 1028, 973, 867, 801, 748, 693, 675, 612.

Results and Discussion

Coordination of Au(I) Cations to Dinitrogen Complexes

Our study commenced by investigating the formation of heterobimetallic [M–N≡N–Au]+ adducts between the group 6 (Mo, W) dinitrogen complexes [M(dppe)2(N2)2] (2M), [M(depe)2(N2)2] (3M), and [M(PMe2Ph)4 (N2)2] (4M) and Au(I) cations supported by NHC ligands. Due to their strong σ-donor character and their steric profiles, NHCs are well-known to provide both excellent stabilization of Au(I) complexes and enhancement of their catalytic activities.32 Independently of the ligand, monoligated cationic Au(I) complexes are notoriously unstable and tend to readily decompose to colloidal gold, precluding their isolations.33 Thus, we elected to assess two strategies: (i) reaction of the N2 complexes on [Au(Cl)(NHC)] to form μ-N2 heterobimetallic complexes by displacement of the chloride ligand or (ii) generation of monoligated Au(I) cations in situ in the presence of the N2 complexes (Scheme 2). Considering that H+ and Au+ are isolobal, the first approach could be regarded as analogous to reactions of group 6 N2 complexes with HCl, which are known to afford the protonated products [M(Cl)(NNH2)(L)4]Cl.34 The second strategy requires generation of the Au(I) cation. The standard approach to prepare [Au(NHC)]+ is through the treatment of [Au(Cl)(NHC)] complexes with the corresponding Ag+ salt to form AgCl. However, the exact nature of [Au(NHC)]+ complexes in the presence of Ag+ has recently been questioned in view of the Ag+ effect on catalytic activity and NMR analytic data of some Au(I) complexes.35 Moreover, the redox potential of Ag/AgCl (0.22 V vs SHE) lies above the redox potentials of the dinitrogen complexes considered (2M ≈ 0.09 V, 3M ≈ −0.2 V vs SHE),36 and adventitious remains of AgI could lead to undesired redox reactions that would compromise the analysis of the reaction’s outcome. A more suitable strategy is to form Au(I) cations by salt metathesis between a sodium salt of an adequate counteranion and Au(Cl)(NHC) complexes. To avoid competition between the anion and dinitrogen for coordination to the gold center, we used the noncoordinating anion tetrakis(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl) borate ([BArF]−). Cationic gold complexes with anions showing low gold affinity such as BArF– have been observed in some cases to have increased catalytic efficiency and equal robustness than salts of more coordinating anions.35,37

Scheme 2. Synthetic Strategies to Probe the Formation of [M–N≡N–Au] Heterobimetallic Complexes.

Reaction of [Au(Cl)(NHC)] with 2W

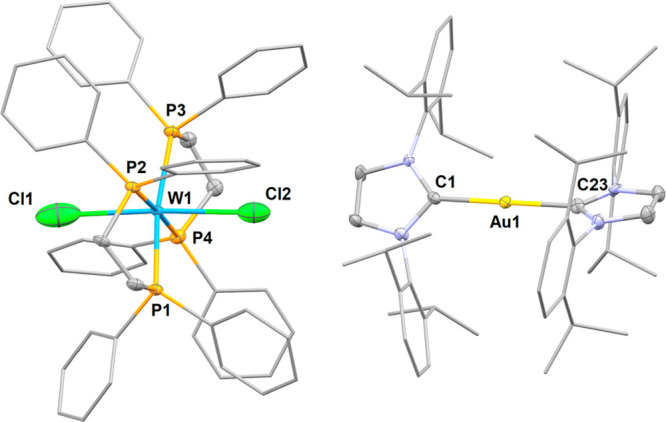

In tetrahydrofuran-d8 (THF-d8), 2W was reacted with 1 equiv of [Au(Cl)(Idipp)] (see SI for details; Idipp: 1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazolin-2-ylidene). Over 18 h at 75 °C, the 1H NMR signature of 2W slowly disappeared concomitantly with the formation of a well-defined new set of signals for the Idipp moiety and clear markers of the buildup of paramagnetic species such as numerous broad signals in 1H NMR and a loss of signals in 31P NMR. X-ray diffraction study on dark red crystals that precipitated out of the solution allowed to characterize the W(I), Au(I) salt [W(Cl)2(dppe)2][Au(Idipp)2] (5W) as one of the products of the reaction (isolated in 32% yield relative to W content; Figure 1). Further heating of the reaction mixture led to the deposition of the W(II) complex [W(Cl)2(dppe)2] as bright red crystals (up to 18% yield relative to W content after 3 days at 75 °C).

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of complex 5W in the solid state (ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level, ligand substituents are drawn with wireframe, and hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg): C1–Au1 2.033(4), C23–Au1 2.026(4), Cl1–W1 2.732(3), Cl2–W1 2.6674(19), P1–W1 2.4108(11), P2–W1 2.4188(11), P3–W1 2.4308(11), P4–W1 2.4408(11), C1–Au1–C23 179.36(18), Cl1–W–Cl2 176.41.

The [W(Cl2)2(dppe)2]− anion of 5W lies in a slightly distorted octahedral geometry with two chloride ligands in a trans relationship. The formal +I oxidation state of the tungsten is inferred from charge balance and from the dimension of the WCl2P4 core, which follows the tendency established between the isostructural neutral complex of W(II) and the cationic complex of W(III) (shorter W–P distances and longer W–Cl distances for decreasing oxidation states).38 The structural parameters of the cation are comparable to those reported for [Au(Idipp)2][BF4].39 The gold(I) center bears two Idipp ligands in a linear geometry, arranged with a 47.95° torsion angle between the imidazolyl planes to minimize the steric repulsion between the carbene fragments. Evidently, two equivalents of [Au(Cl)(Idipp)] are necessary for the formation of 5W and [W(Cl)2(dppe)2], the former producing a Au(0) species that has not been identified. However, reacting 2W with 2 equiv of [Au(Cl)(Idipp)] does not increase the yield of these complexes significantly, indicating that there are multiple pathways to the formation of paramagnetic species and decomposition of the Au(I) cation. No reaction takes place at room temperature or in a less coordinating solvent (in the latter case owing to the poor solubility of [Au(Cl)(Idipp)]). Thus, even if a reactivity similar to HCl could take place to form complexes such as [W(Cl)(dppe)2(μ-N2)(Au(Idipp)], the harsh conditions necessary to form them favors in fine electronic transfer reactions.

Generation of Monoligated Au(I) Cation in Situ

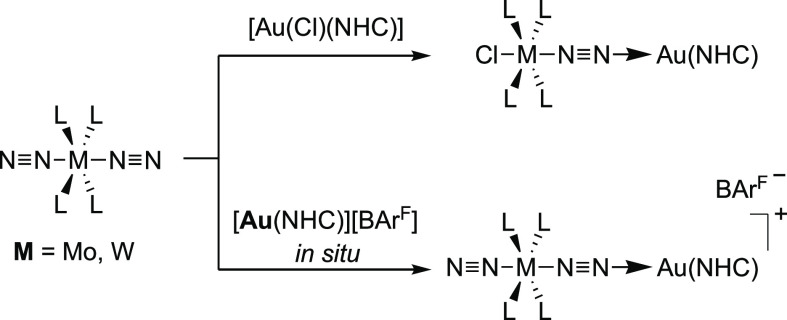

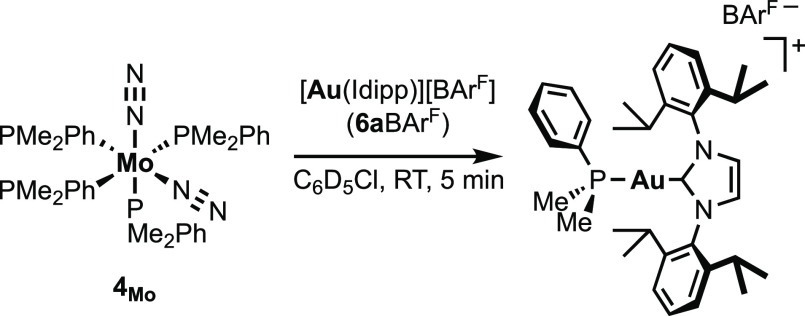

We then investigated a series of [Au(NHC)]+ cations (6+; Scheme 3) for their coordination to N2 complexes 2M, 3M, and [M(PMe2Ph)4 (N2)2] [M = Mo, 4Mo (80:20 cis/trans mixture); M = W, 4W (only cis)].

Scheme 3. Group 6 Dinitrogen Complexes Surveyed (Top, M = Mo or W) and Formation of [Au(NHC)][BArF] Salts and Selection of the NHCs Used in This Work (Bottom).

We first explored the reaction of the in situ generated [(Idipp)Au][BArF] (6aBArF) with 1 equiv of trans-[Mo(N2)2(dppe)2] 2Mo at room temperature in chlorobenzene-d5. Within a few minutes, a mixture of several compounds formed according to NMR spectroscopy. During the first hour of the reaction, the major product (≈ 60%) was presumed to be the heterobimetallic adduct trans-[Mo(N2)(dppe)2(μ-N2)Au(Idipp)][BArF], 7aMoBArF. This complex was identified by a singlet in 31P{1H} NMR at δ 63.5 ppm, shifted upfield compared to 2Mo (δ 65.7 ppm), and by two bands in IR spectroscopy at 1865 and 2127 cm–1 assignable to the elongated bridging Mo–N2–Au moiety and the N2 in trans position, respectively (vs. 1974 cm–1 for 2Mo). The mixture evolved rapidly, since after 3 h at RT, 7aMoBArF only amounted to ≈20% of the mixture and had disappeared after 18 h. Decomposition of 7aMoBArF occurred predominantly through the abstraction of a phosphine ligand by 6a+ to yield the new complex [(dppe)Mo(μ-η1:η1:η6-dppe)Au(Idipp)][BArF] 8Mo (≈80%; Figure 2). Bright red single crystals fit for X-ray diffraction analysis of 8Mo could be recovered among polycrystalline materials upon slow diffusion of pentane into the crude mixture; however, efforts to isolate or recover single crystals of 7aMoBArF were unsuccessful.

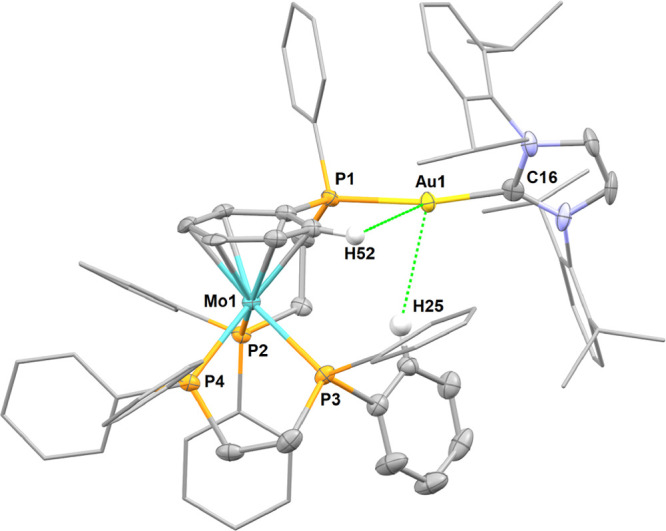

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of complex 8Mo in the solid state (ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level, some ligand substituents are drawn with wireframe, all hydrogen atoms not interacting with the gold center and the BArF anion are omitted for clarity). Selected distances (Å) and angles (deg): Mo1–P2 2.471(2), Mo1–P3 2.444(2), Mo1–P4 2.446(2), Au1–P1 2.283(2), Au1–C16 2.034(7), Au1–H25 2.881, Au1–H52 2.878, P1–Au1–C16 169.5(2).

The Mo center adopts a three-legged piano stool geometry with a dppe unit coordinated classically with two phosphorus atoms and the other dppe unit chelating through one phosphorus atom and a phenyl substituent of the other phosphorus atom in a η6 coordination mode. The second phosphorus is coordinated to the gold center of 6a, which lies in a distorted linear geometry (169.5°) to accommodate for agostic interactions with hydrogen atoms of the Mo coordinated phenyl ring and a second phenyl substituent. NMR analysis of the mixture containing 8Mo is coherent with the conservation of this structure in solution. The 1H NMR spectrum shows a set of five protons at δ 3.26, 3.49, 3.73, 4.58, and 4.63 ppm diagnostic of an η6-phenyl on the Mo center, in line with the chemical shifts of η6-phenylphosphine ligands found on comparable Mo complexes.40 The agostic interaction between the gold center and the two ortho protons of one phenyl substituent is corroborated by a particularly upfield signal at 5.46 ppm in 1H NMR. All phosphine ligands are inequivalent: in 31P{1H} NMR, three resonances show coupling to each other at δ = 76.6, 75.1, and 41.9 ppm, the fourth signal for the phosphine coordinated to the gold cation being found at δ 26.7 ppm.

Attempts to produce crystals of 7aMoBArF and 8Mo led on some occasions to the formation of minute amounts of dark yellow crystals identified by X-ray diffraction analysis as [Mo(Cl)(N2)(dppe)2] (9Mo, Figure 3). The MoI center in 9Mo is stabilized by a chloride ligand presumably sourced from the NaCl formed by salt metathesis between NaBArF and [Au(Cl)(Idipp)]. 9Mo has an octahedral geometry with dinitrogen and chloride ligands in a trans position, both statistically disordered within the crystal lattice.41 The formation of MoI species can reasonably be attributed to electronic transfers between Mo0 and AuI even though the nature of the accompanying Au0 species has not been determined.

Figure 3.

Molecular structure of complex 9Mo in the solid state (ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level, hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg): Mo1–Cl1 2.396(7), Mo1–N2 2.15(5), P1–Mo1 2.4796(19), P2–Mo1 2.5083(18), P3–Mo1 2.4622(19), P4–Mo1 2.5032(18), Cl1–W–N2 177.1(12).

Reaction of trans-[W(N2)2(dppe)2] (2W) with 6aBArF and [Au(Me2Idipp)][BArF] (6bBArF, Me2Idipp: 1,3-bis[2,6-bis(1-methylethyl)phenyl]-1,3-dihydro-4,5-dimethyl-2H-imidazol-2-ylidene) produced very similar results, which is unsurprising given the structural closeness between the two NHC ligands. 2W was reacted with 1 equiv of 6aBArF or 6bBArF at room temperature in chlorobenzene-d5. Analyses of the reaction mixtures by NMR and IR spectroscopies were indicative of the immediate formation of the heterobimetallic adducts [W(N2)(dppe)2(μ-N2)Au(Idipp)][BArF] (7aWBArF) and [W(N2)(dppe)2(μ-N2)Au(Me2Idipp)][BArF] (7bWBArF; Scheme 4). The 31P{1H} NMR spectra of the adducts display a single peak shifted upfield compared to 2W (δ = 46.2 ppm) at 45.5 ppm (JPW = 320.3 Hz, 7aWBArF) or 46.2 ppm (JPW = 307.4 Hz, 7bWBArF). The 1H NMR spectrum showed two inequivalent sets of methylene protons indicating a decreased symmetry at the W center. There is a single set of signals for the NHCs, and 7aWBArF presents a slight downfield shift for the protons of the backbone of the imidazole fragment. This was attributed to a decrease of electronic density due to the delocalization of the π-electrons toward the more acidic gold center. This increased acidity is also corroborated by the significant upfield shift of the carbenic carbons in 13C NMR at 166.6 ppm (7aWBArF) and 162.5 ppm (7bWBArF) vs 176.8 and 172.8 ppm for the corresponding [Au(Cl)(NHC)] complexes. The 13C NMR carbenic carbon chemical shift of 7aWBArF is comparable to that of isolated acetonitrile adducts of [Au(NCMe)(Idipp)]+ salts.42 The spectral signatures in 11B and 19F NMR are typical of the BArF anion.

Scheme 4. Synthesis and Proposed Identity of 7aWBArF and 7bWBArF.

Adducts 7aWBArF and 7bWBArF retain both N2 ligands in solution according to infrared measurements in chlorobenzene that showed two broad, intense bands at 1851 and 2085 cm–1 assignable to the elongated bridging W–N2–Au moiety and the mono ligated N2, respectively (vs. 1947 cm–1 for 2W in PhCl). The shift to higher wavenumbers in the IR spectra (vs. 2W) of the N2 in trans position is diagnostic of decreased N2 activation. Accordingly, 7aWBArF and 7bWBArF are unreactive toward a second equivalent of [Au(NHC)]+. After in situ formation in chlorobenzene-d5, the adducts are stable for hours, but 2W is slowly recovered over a period of days. Attempts to remove the solvent under a vacuum or to precipitate 7aWBArF and 7bWBArF by treatment of the solution with pentane or hexamethyldisiloxane yielded predominantly 2W (>50%) as well as multiple uncharacterized W complexes and several sets of signals for the NHC moieties are observed in 1H NMR. The instability of 7aWBArF and 7bWBArF generated in this manner precluded their isolation and characterization by X-ray diffraction techniques. Recovery of 2Mo/2W from adducts 7aWBArF and 7bWBArF suggests that the free gold cations are in equilibrium with the gold cations coordinated to the N2 complex. The inherent instability of monoligated gold cations in solution might then result in their decomposition. These equilibria are evidenced by the presence of a small band corresponding to the N2 ligands of 2Mo/2W in the infrared measurement of the adducts in chlorobenzene (1947 cm–1 for 2W). There is no interaction between 2W and 6a+ in THF-d8, the latter forming the THF adduct [Au(THF)(Idipp)]+ already reported in the literature.42 The weak gold coordination to N2 in 7aWBArF and 7bWBArF could stem from the steric bulk of both the gold NHCs and the N2 complexes’ phosphine ligands.

We then explored the formation of adducts with [Au(IMes)]+ (6c+, IMes: 1,3-bis(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene) and [Au(ItBu)]+ (6d+, ItBu: 1,3-ditert-butylimidazol-2-ylidene) that present a reduced steric hindrance at the gold center (vs. 6a+ and 6b+). 2Mo reacted with 6cBArF or 6dBArF in chlorobenzene-d5 at RT to yield complex mixtures upon solvation of the gold cations. The main products visible within the first hour (>60% in both cases) showed spectroscopic signatures similar to 8Mo, diagnostic of η6-phenyl coordination to the Mo center with a set of five broad signals in 1H NMR (Figures S67 and S69). Phosphine coordination to the gold centers is characterized by signals in 31P{1H} NMR at δ = 29.8 and 29.3 ppm for 6c+ and 6d+, respectively. The lower steric hindrance at the gold center seemingly favors abstraction of the phosphine ligand as no putative N2 adduct could be observed, contrary to the reaction of 2Mo with 6aBArF. The reaction of 2W with 1 equiv of 6cBArF or 6dBArF in chlorobenzene-d5 at RT allowed immediate observation of the putative adducts [W(N2)(dppe)2(μ-N2)Au(NHC)][BArF] characterized by singlets in 31P{1H} NMR at δ = 44.4 and 45.8 ppm for 7cWBArF and 7dWBArF, respectively, that are upfield-shifted compared to 2W (δ 46.2 ppm). Infrared analysis of aliquots taken immediately after the mixing of 2W and 6cBArF (or 6dBArF) in chlorobenzene also supports adduct formation with the presence of two vibrations at 1865 cm–1 (7dWBArF: 1855 cm–1) and 2077 cm–1 (7dWBArF: 2077 cm–1) corresponding to the bridging W–N2–Au moiety and the N2 in trans relationship, respectively (vs 1947 cm–1 for 2W in PhCl). These adducts are short-lived, as they represented approximatively 60% of the mixture after 30 min at room temperature and had completely decomposed after 4 h to yield an intractable mixture of paramagnetic compounds and complexes issued from phosphine abstractions. Due to their instability, these putative adducts could not be further characterized or isolated. As 2W is not recovered, their decomposition process stands in contrast with the decomposition of 7aWBArF and 7bWBArF. This can be rationalized by a stronger gold coordination to the dinitrogen ligand owing to the reduced steric strain, which is however balanced by an increased aptitude to engage in phosphine abstraction reaction (presumably driven by steric relief at the W center). The formation of paramagnetic complexes as testified to by broad signals in 1H NMR could also be favored by the reduced steric congestion, offering easier pathways for electronic transfers to take place (vs 7aWBArF and 7bWBArF).

To assess the influence of the steric congestion of the N2 complex, we explored the coordination of 6a+ to complexes [M(PMe2Ph)4(N2)2] (4M), which offer reduced steric hindrance and increased flexibility of the ligand spheres compared to the dppe complexes. We reacted a cis/trans mixture of [Mo(N2)2(PMe2Ph)4] (4Mo) with 1 equiv of 6aBArF in chlorobenzene-d5 at room temperature, and we observed that the orange solution rapidly turned dark red upon solvation of the gold salt. The heteroleptic complex [Au(Idipp)(PMe2Ph)][BArF] was obtained quantitatively within minutes, characterized by a signal at δ 11.5 ppm in 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy (Scheme 5) and identified by its isolation from the reaction mixture (see SI). Under the same conditions as with cis-[Mo(N2)2(PMe2Ph)4] (4Mo), the phosphine abstraction on cis-[W(N2)2(PMe2Ph)4] (4W) by 6a+ proceeded at a much slower rate, allowing for 6a+ to engage in electron transfer reactions with the thus-formed unsaturated W complex, producing uncharacterized paramagnetic compounds.

Scheme 5. Phosphine abstraction on 4Mo to form [Au(Idipp)(PMe2Ph)][BArF].

The facile abstraction of the monodentate phosphine highlighted the need to use chelating phosphine ligands able to limit phosphine abstraction while presenting a reduced steric profile compared to dppe. To this end, we then explored the coordination of gold cations to 3W. The depe ligand presents the double advantage of being less encumbered and more electron donating than dppe. The reduced steric bulk should allow for a closer proximity of the gold center to the N2 ligand and prevent phosphine abstraction by mitigating the steric relief driving force. The increased electron donating ability of depe also provides stronger phosphine metal bonds, although an increased electronic density at the metal center should also favor electron transfer reactions. In chlorobenzene-d5 at RT, 3W reacted immediately with 1 equiv of 6b+, 6c+, 6d+, and 6e+ to form the corresponding heterobimetallic adducts [W(N2)(depe)2(μ-N2)Au(NHC)][BArF] 10b–eWBArF as the main product, along with minor, unidentified paramagnetic compounds. Under the same conditions, the reaction of 6aBArF with 3W immediately gave an intractable mixture of products. The reactivity difference between 6a+ and 6b+ could originate from the electron donation of the methyl groups to the imidazole ring of 6b+, the resulting increased electronic density at the gold center in turn disfavoring electronic transfers from the W center. Adducts 10b–eWBArF share similar spectroscopic signatures of which key parameters are summarized in Table 1. In 1H NMR, adducts 10b–dWBArF are characterized by a single set of signals for the NHC ligand along with inequivalent methylene and ethyl fragments, indicative of a loss of symmetry at the W center. On the contrary, the NHC ligand of 10eWBArF shows differentiated signals in 1H NMR for the substituents and the imidazole ring, which could be related to steric interactions between the depe ligand and the adamantyl moieties hindering free rotation on the NMR time scale. In all adducts, the phosphine ligands display a single, well resolved peak in 31P{1H} NMR, shifted upfield compared to 3W (Δδ: −1.6 to −3.6 ppm). As with adducts of dppe-supported complexes, the solution IR spectra of 10b–eWBArF display two broad bands corresponding to the elongated bridging dinitrogen in the 1700–1800 cm–1 region and the trans dinitrogen ligand in the 2000–2100 cm–1 region.

Table 1. Key NMR Chemical Shifts and Vibrational Modes of Adducts 10b–eWBArF in Solution.

| complex | δ 31Pa | Δδ 31P vs 3Wa | νNNb | ΔνNN vs 3Wb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10bWBArF | 34.2 | –2.0 | 1796 | –113 |

| 2044 | +135 | |||

| 10cWBArF | 34.4 | –1.8 | 1775 | –134 |

| 2050 | +141 | |||

| 10dWBArF | 32.6 | –3.6 | 1767 | –142 |

| 2052 | +143 | |||

| 10eWBArF | 34.6 | –1.6 | 1783 | –126 |

| 2048 | +139 |

C6D5Cl, expressed in ppm.

C6H5Cl solution in transmission cell, expressed in cm–1.

Isolation of Heterobimetallic Complexes 10b–eWBArF

Complexes 10b–eWBArF decomposed within hours in solution as evidenced by the formation of broad signals along with multiples set of signals for the NHC ligands in 1H NMR and the disappearance of 31P NMR signals, both diagnostics of the formation of paramagnetic compounds (vide infra), presumably formed by W(0) → Au(I) electronic transfers. Nevertheless, 10b–eWBArF can be precipitated by pouring concentrated PhF solutions of the freshly formed adducts in precooled pentane (−40 °C) to afford purple to dark brown NaCl/10b–eWBArF mixtures, recovered by decantation. The fine NaCl precipitate can then be suspended with pentane washes of the solids, allowing for the isolation of 10b–eWBArF as purple or brown microcrystalline powders in good yields (80–85%; Scheme 6). The isolated adducts decompose slowly at room temperature and rapidly under a vacuum but can be stored indefinitely at −40 °C. Characterization by elemental analysis gave a lower-than-expected N content; however, this is likely the result of degradation during the analytical process as FTIR-ATR analysis confirmed the retention of the second N2 ligand in the solid state.

Scheme 6. Isolation of Heterobimetallic Complexes 10b–eWBArF with Relevant Vibrational Modes (ATR).

The bridging dinitrogen ligand is moderately activated in complexes 10b–eWBArF as evidenced by shifts in the vibrational frequencies ranging from −123 to −160 cm–1 (vs 3W). Evaluation of the Lewis acidity of cations 6a+ to 6e+ yielded similar acceptor numbers (from 6a+ to 6e+, ANs = 87.3, 86.4, 87.5, 85.6, 85.3, see Table S2) for all NHC ligands, revealing that the variations of N2 activation were mostly due to sterics. The percent buried volume (%Vbur) is a good indication of the steric hindrance in the proximity of the gold center for symmetrical NHC ligands. According to the measured %Vbur on a series of [Au(Cl)(NHC)] complexes, cations 6+ can be ordered as 6d+ < 6e+ ≈ 6c+ < 6b+ by increasing steric hindrance (%Vbur = 44.4, 36.5, 39.8, and 39.6% from 6b+ to 6e+, respectively).43 However, the highest μ-N2 ligand activation is achieved in the adduct 10dWBArF and differs significantly from adduct 10eWBArF, which indicates that long-range steric hindrance has more impact than that in the gold center proximity. Indeed, the bulky, far-reaching adamantyl and diisopropylphenyl substituents of 6e+ and 6b+ translate to lower N2 activation than when the planar mesityl or the smaller tert-butyl substituents found in 6c+ or 6d+, respectively, are present. No correlations were found between ΔνNN and either the ANs of the cations or the %Vbur.

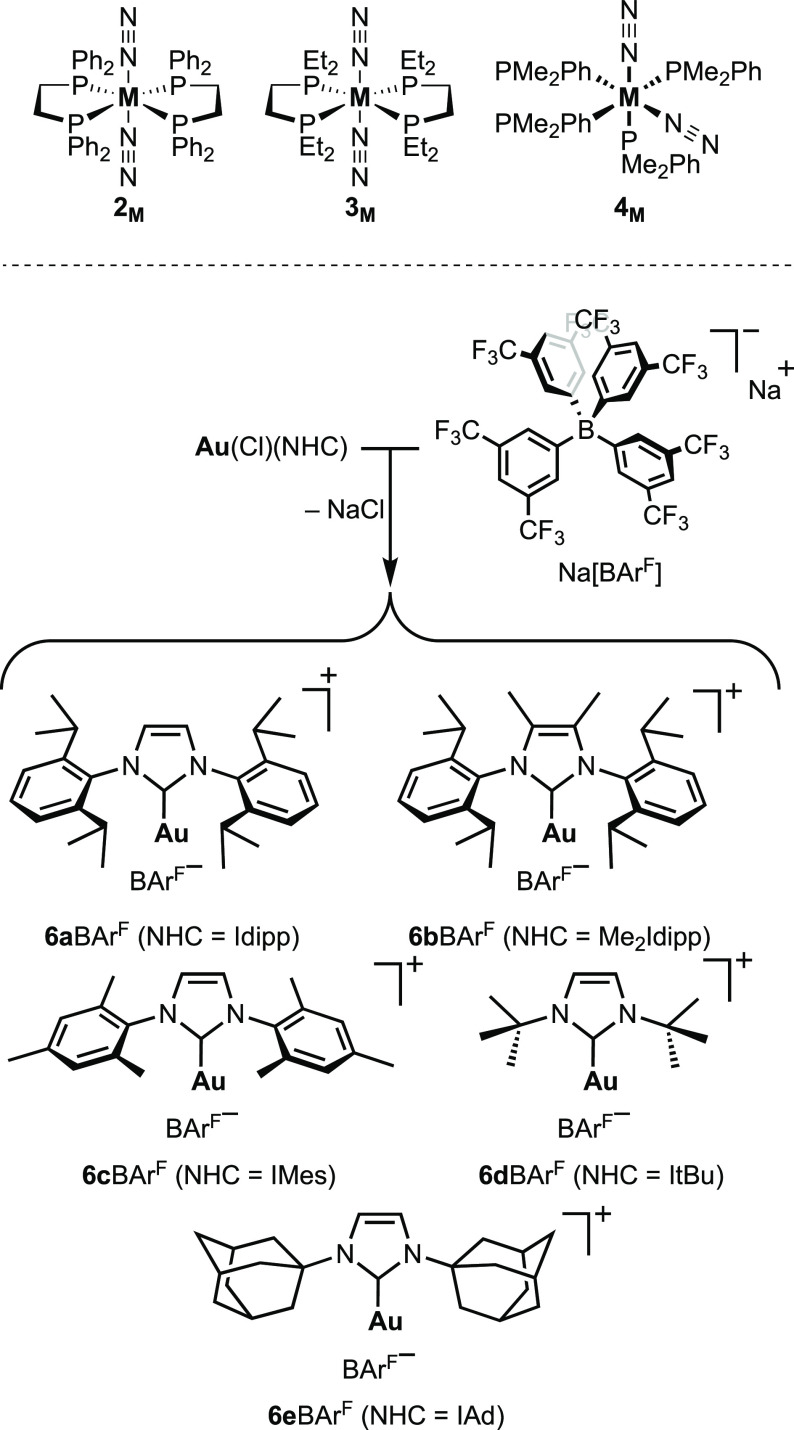

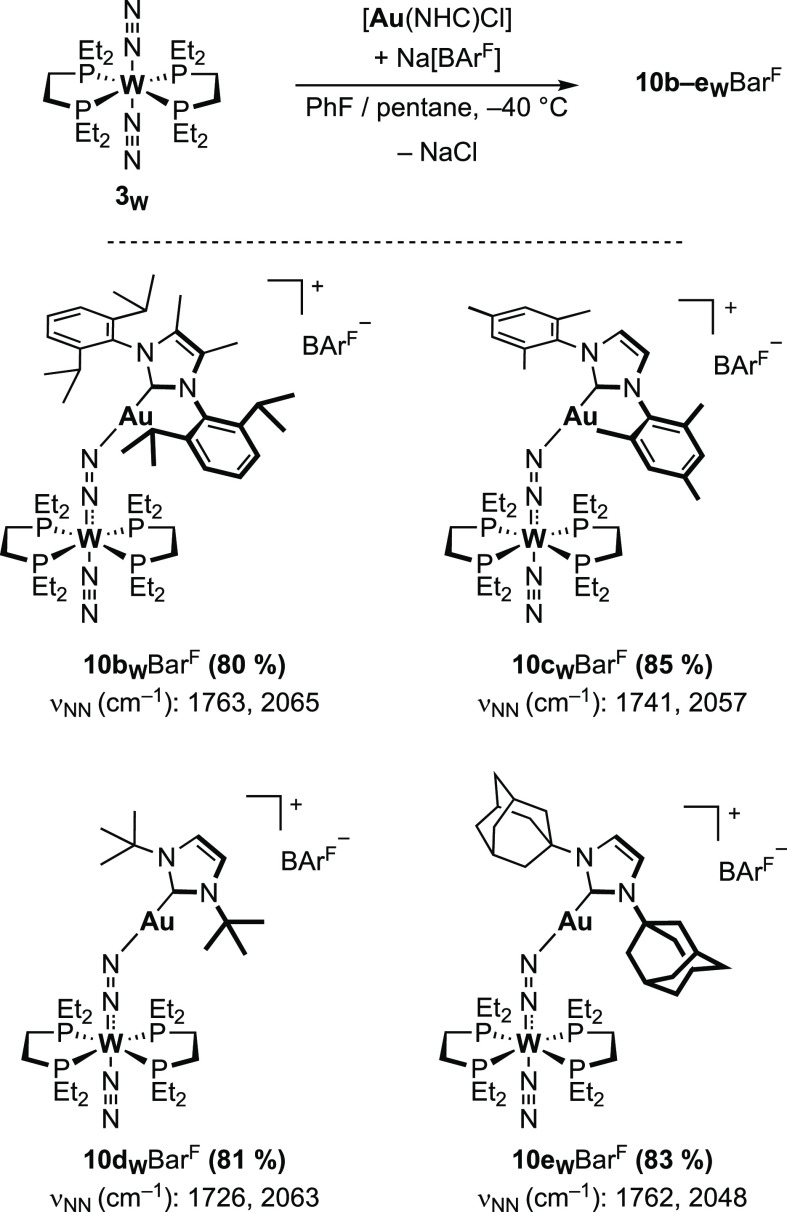

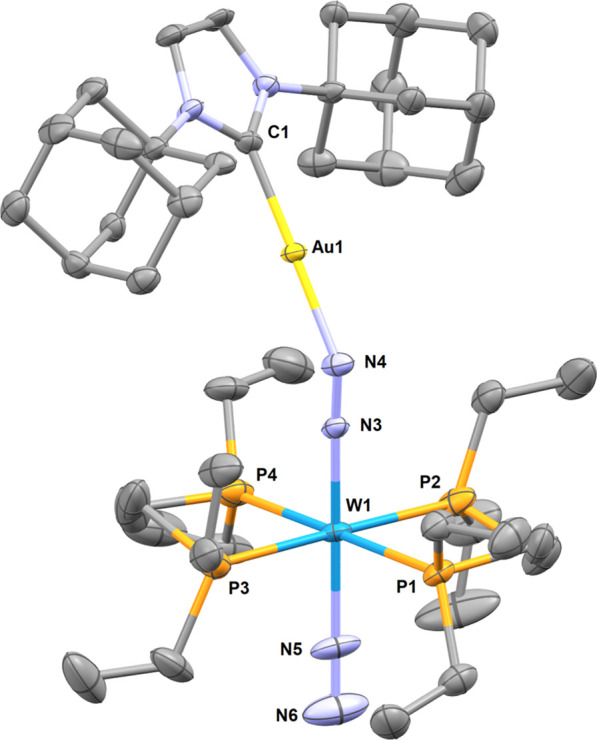

The structure of 10eWBArF could be determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first structural characterization of an N2-bridged heterobimetallic complex featuring a group 11 metal. It features an octahedral ligand sphere around the W center with two depe ligands included almost perfectly in the equatorial plan (Figure 4). The N2 and μ-N2 ligands are in an axial position with a slight deformation to accommodate for the coordination of [Au(IAd)]+ (N–W–N = 178.2(3) °). The W(μ-N2)(Au{NHC}) motif presents a shortened W–N bond (1.896 Å vs 2.0154(11) Å for 3W) and a lengthened N–N bond (1.179 Å vs 1.096 Å for free N2 and 1.123(2) Å for 3W). The bond orders are ambiguous with a W–N distance falling within simple and double bonds and the N–N distance within double and triple bonds.44 The gold(I) complex unsurprisingly shows linear geometry with a N–Au bond distance of 2.015 Å, matching with the few examples of [Au(NHC)]+ coordination to nitrogen bases (e.g., 2.016 Å for [(MeCN)Au(Idipp*)][BF4]) with structural characterization.45 The N–N–Au angle of 142.6° suggests a similar bonding situation as the one found in main group adducts of end-on dinitrogen complexes.11e,12,46

Figure 4.

Molecular structure of complex 10eWBArF in the solid state (ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level, hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg): W1–N4 1.896(6), N4–N3 1.179(8), N3–Au1 2.015(6), W1–N5 2.071(7), N5–N6 1.09(1), W1–N4–N3 176.3(5), N4–N3–Au1 142.6(5), W1–N5–N6 177.4(7), N4–W1–N5 178.2(3), C1–Au1–N3 179.2(3).

Comparison with Relevant N2-Bridged Adducts

To the best of our knowledge, there is only one example of a group 6 N2 complex reacting with a Lewis acidic, d-block metal compound in the literature, to lead to the Mo(0)/Fe(II) heterobimetallic complex [(toluene)(PPh3)2Mo(μ-N2)Fe(Cp)(dmpe)][BF4] (dmpe = 1,2-bis(dimethylphosphino)ethane).47 Its structure is however very similar to the numerous LA–TMs adducts reported with the d6trans-[ReCl(N2)(PMe2Ph)4]6 complex, and they contrast strikingly with the [Au(NHC)]+ adducts of 2W and 3W. In typical adducts with a Lewis acidic metal M′, the M–(μ-N2)–M′ core is essentially linear owing to the implication of empty or partially filled d orbitals of M′ in a four-center π molecular orbital.48 Conversely, the structure of 10eWBArF has a bent W–(μ-N2)–Au motif. Since this bonding situation is typically found with main group Lewis acids,12 comparison of [Au(NHC)]+ coordination to N2 with boranes such as 1 is especially relevant. To this end, we have carried out the reaction of trans-[M(depe)2(N2)2] (M = Mo, 3Mo; M = W, 3W), with the strong LA tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane (B(C6F5)3, 1) in a similar fashion as reported previously with trans-[M(dppe)2(N2)2] (2).12 Upon treatment of complexes 3Mo and 3W with 1 in toluene-d8 at room temperature, immediate formation of a dark brown solution was observed. The major product formed in both cases (>75% for 3Mo and >90% for 3W according to 31P NMR) is the adduct trans-[Mo(depe)2(N2)(N=N–B{C6F5}3)] (11Mo) or trans-[W(depe)2(N2)(N=N–B{C6F5}3)] (11W) according to 1H, 11B, 19F, and 31P NMR spectroscopy. The two compounds show similar spectroscopic signatures with two sets of signals for the ethyl groups and ethane backbone in 1H NMR. The phosphines are equivalent as evidenced by a single peak in 31P{1H} NMR at δ 52.9 ppm for 11Mo and δ 34.7 ppm for 11W (JPW = 293 Hz), upfield-shifted compared to 3Mo and 3w (δ 55.9 and 36.2 ppm, respectively). Diagnostic signals of borane coordination are seen in 11B and 19F NMR. Layering pentane over toluene solutions of the complexes at −40 °C allows for their recovery as orange (11Mo) or purple (11W) crystals in 53% and 62% yield, respectively. The structures of complexes 11Mo and 11W were confirmed by X-ray diffraction (Figure 5). The M(μ-N2)(B{C6F5}3) moiety features ambiguous bond orders with M–N distances falling within simple and double bonds [1.894(4) Å for 11Mo and 1.908(7) Å for 11W vs 2.031 Å for 3Mo and ≈ 1.70–1.80 Å for M = N]49 and N–N distances for the bridging N2 ligand falling within double and triple bonds [1.174(5) Å for 11Mo and 1.180(9) Å for 11W vs 1.117 Å for 3Mo and 1.096 Å for free N2]. The B–N bonds are comparable to adducts of 1 with other nitrogen bases [1.561(6) Å for 11Mo and 1.549(11) Å for 11W].50 The dinitrogen ligand in trans position shows longer M–N bonds [2.128(5) Å for 11Mo and 2.093(11) Å for 11W] and shorter N–N distances [1.092(7) Å for 11Mo and 1.082(11) Å for 11W] consistent with a decreased activation. The tetrahedral character of the boron atoms is 85% (11Mo) and 89% (11W).51 FTIR-ATR spectra of the crystals feature two strong absorptions in the 2400–1600 cm–1 region, one corresponding to the stretching of the N–N bond of the bridging N2 at 1789 cm–1 (11Mo) and 1767 cm–1 (11W; vs 1914 cm–1 for 3Mo and 1890 cm–1 for 3W); the second vibration corresponds to the stretching of the N–N bond of the monoligated N2 ligand at 2120 cm–1 (11Mo) and 2076 cm–1 (11W).

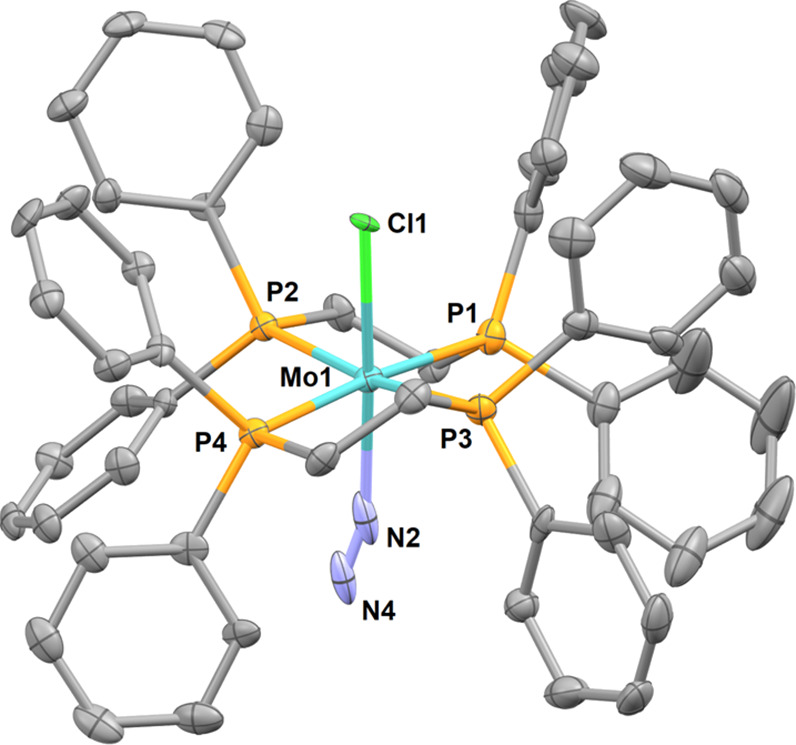

Figure 5.

Molecular structure of complexes 11Mo (left) and 11W (right) in the solid state (ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level; hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg), 11Mo: Mo1–N1 1.894(4), N1–N2 1.174(5), N2–B1 1.561(6), Mo–N3 2.128(5), N3–N4 1.092(7), Mo1–N1–N2 169.9(3), N1–N2–B1 150.9(4), Mo1–N3–N4 177.9(5), N1–Mo1–N3 176.26(16), C24–B1–C36 117.8(3), C24–B1–C30 111.4(3), C36–B1–C30 104.6(4), C24–B1–N2 105.1(3), C36–B1–N2 109.8(4), C30–B1–N2 107.8(4). 11W: W1–N1 1.908(7), N1–N2 1.180(9), N2–B1 1.549(11), W–N3 2.093(8), N3–N4 1.082 (11), W1–N1–N2 168.9(5), N1–N2–B1 148.3(7), W1–N3–N4 177.9(8), N1–W1–N3 175.7(3), C31–B1–C41 112.7(7), C31–B1–C21 104.3(6), C41–B1–C21 114.9 (7), C21–B1–N2 109.8(7), C31–B1–N2 108.1(6), C41–B1–N2 106.9 (7).

The retention of the second N2 ligand contrasts with the previously reported12 structures of [Mo(dppe)2(N=N–B{C6F5}3)] (12Mo) and [W(dppe)2(N=N–B{C6F5}3)] (12W) for which the formation of the Lewis pair induced the dissociation of the second N2 ligand. This retention is likely due to the electron richness of the depe ligand compared to the dppe ligand, which increases the electronic density available at the metal center for π-backbonding. The bridging N2 ligand is slightly less elongated in complexes 11M than in 12M as evidenced by shorter N–N distances (−0.02 to −0.03 Å). These differences correlate with the lower shift of the N–N stretching vibrations for 11M compared to 12M (vs dinitrogen complexes 3M) observed by IR spectroscopy. Such a difference in N2 activation can be attributed to the influence of the retained N2 ligand, as d electrons involved in back-bonding are delocalized over two N2 units in complexes 11M.

Adducts of 1 or 6e+ with 3W show similar N–N–LA angles (148.3° for 11W, 142.6° for 10eWBArF), elongations of the μ-N–N distance (1.180 Å for 11W, 1.179 Å for 10eWBArF), and shortening of the W–N bond (1.908 Å for 11W, 1.896 Å for 10eWBArF). This closeness in N2 push–pull activation is in line with the ANs of LAs 1 and 6a–e+, all being found between 79 and 88. The structural similarity between 11W and [Au(NHC)]+ adducts of 3W is also reflected by their similar μ-N2 vibrational frequencies, especially when compared to 10bWBArF and 10eWBArF (ΔνNN ≤ 5 cm–1). Although 1 and cation 6e+ are poorly related in terms of structure, charge, and electronegativity of their central element, their push–pull activation is comparable. Adducts 10cWBArF and 10dWBArF with the less bulky NHC substituents at gold afford greater N2 activation than in 11W. In regard to the similar properties of these 3W adducts, the predominant steric effect over the coordination of [Au(NHC)]+ to N2 complexes is unveiled by the considerable differentiation between 12W and the related gold adducts. Indeed, 12W presents a higher N2 activation (ΔνNN = −233 cm–1 vs 2W) than 11W, whereas [Au(NHC)]+ coordination on 2W leads to weaker N2 activations than with 3W (e.g., ΔνNN = −95 cm–1 vs 2W for 7bWBArF and −124 cm–1 vs 3W for 10bWBArF). This difference of behaviors likely stems from the shape of the LAs as the NHCs’ substituents expand toward the dppe ligands, which increases considerably the steric repulsion with the phenyl groups of the phosphine compared to the outward extending borane substituents. In addition, IR analyses of 2W-gold adduct solutions point to a retention of the second N2 ligand which, as mentioned above, has an influence on the activation of the bridging N2 ligand.

15N-Labeling Experiments

The 15N-labeled complexes 15N-10eWBArF and 15N-11W were synthesized from [W(15N2)2(depe)2] (15N-3W) following the same aforementioned procedures. FTIR-ATR analysis of the labeled complexes confirmed the identification of the N2 ligands’ vibration in the 14N analogues with bathochromic shifts of −71 cm–1 (N2) and −58 cm–1 (μ-N2) for 15N-10eWBArF (vs 14N-10eWBArF, bands at 1977 and 1704 cm–1) and shifts of −69 cm–1 (N2) and −58 cm–1 (μ-N2) for 15N-11W (vs 14N-11W, bands at 2076 and 1767 cm–1). The 15N NMR chemical shifts of 15N-10eWBArF and 15N-11W are reported in Table 2.

Table 2. NMR Chemical Shifts of Adducts 15N-10eWBArF and 15N-11W.

| complex | solvent | δ 15Nα (μ-N2)a | δ 15Nβ (μ-N2)a | δ 15Nα (N2)a | δ 15Nβ (N2)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15N-2W | C6D6 | –63.1 | –52.0 | ||

| 15N-10eWBArF | C6D5Cl | –40.1 | –119.0 | –76.1 | –42.9 |

| 15N-11W | C6D6 | –55.0 | –152.6 | –73.9 | –37.4 |

Nα = Atom adjacent to W. Nβ = distal nitrogen. Expressed in ppm.

Upon coordination of the Lewis acids, the terminal nitrogen (Nβ) of the bridging N2 is significantly shielded (−67 and −100.6 ppm for 15N-10eWBArF and 15N-11W, respectively) while the tungsten bound nitrogen (Nα) is slightly deshielded (−23 and −8.1 ppm for 15N-10eWBArF and 15N-11W, respectively) compared to 15N-2W. A similar trend was observed by Donovan-Mtunzi et al.52 upon coordination of AlMe3 on various dinitrogen complexes, which contrasts with transition-metal acceptors that typically induce a deshielding of Nβ.

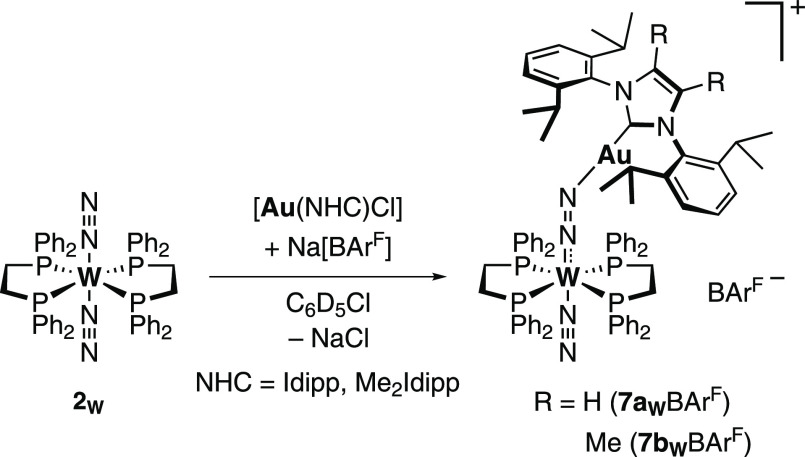

Computational Studies

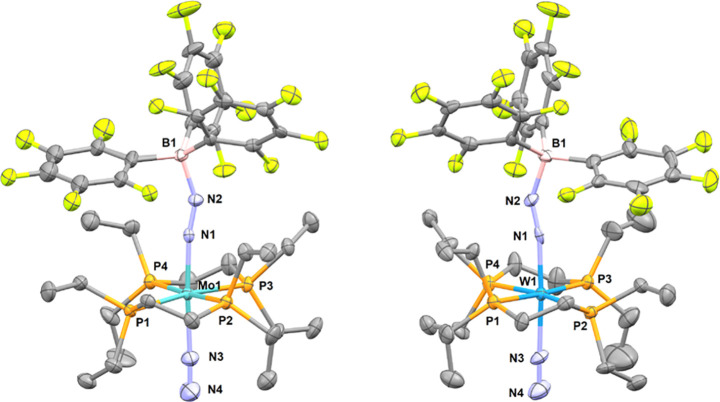

In order to get insight into the nature of the μ-N2–B(C6F5)3 and μ-N2–[Au(NHC)]+ bonds and into the impact of the exogenous LAs on the electronic structure of the M(group 6)-N2 unit, we carried out a DFT computational study at the B3PW91 level of theory on the trans-[W(depe)2(N2)(N=N–B{C6F5}3)] (11W) and trans-[W(depe)2(N2)(μ-N2)Au(IAd)][BArF] (10eWBArF) complexes. The optimized structures of 11W (11W-opt) and 10eWBArF (10eWBArF-opt) are shown in Figure 6. Their corresponding bond distances and angles are listed in Table 3 and compared with those observed experimentally for 11W and 10eWBArF as well as with those of the [W(depe)2(N2)2] precursor (3W and 3W-opt).

Figure 6.

DFT-optimized molecular structures of complexes 11W-opt (left) and 10eWBArF-opt (right). The hydrogen atoms and the [BArF]− anion have been omitted for the sake of clarity.

Table 3. Significant Bond Distances (Å) and Angles (deg) for 10eWBArF, 10eWBArF-opt, 11W, 11W-opt, 3W, and 3W-opt.

| W–N2 | N2–N1 | N1–LA | W–N2b | N2b–N1b | W–N2–N1 | N2–N1–LA | W–N2b–N1b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11W | 1.908 | 1.179 | 1.550 | 2.094 | 1.082 | 169.0 | 148.4 | 177.9 |

| 11W-opt | 1.892 | 1.169 | 1.552 | 2.055 | 1.128 | 170.7 | 145.5 | 179.1 |

| 10eWBArF | 1.896 | 1.179 | 2.015 | 2.071 | 1.093 | 176.3 | 142.6 | 177.4 |

| 10eWBArF-opt | 1.905 | 1.169 | 2.002 | 2.048 | 1.129 | 178.4 | 148.8 | 177.4 |

| 3W | 2.015 | 1.123 | 2.015 | 1.123 | 178.6 | 178.6 | ||

| 3W-opt | 1.999 | 1.139 | 2.000 | 1.138 | 178.3 | 178.3 |

As shown in Table 3, the computed bond distances and angles accurately reproduce the values obtained experimentally with variations that fall within the error of the DFT method. In accordance with the experimental results, the W(μ-N2)–(LA) motif presents a shortened W–N bond (1.892 and 1.905 Å for 11W-opt and 10eWBArF-opt, respectively, compared to 2.000 Å for 3W-opt) and a lengthened N1–N2 bond (1.169 Å for both 11W-opt and 10eWBArF-opt, compared to 1.139 Å for 3W-opt). The N2–N1–LA angles, in addition, measure 145.5° for 11W-opt and 148.8° for 10eWBArF-opt, reproducing well the bent structure observed in the corresponding crystallized complexes. In order to discard the possible implication of solely steric effects in the formation of these bent structures, such as, in particular, the steric constraint between the LA ligands and the diphosphine substituents, we computed the 11W-opt compound by replacing the pentafluorophenyl groups with trifluoromethyl ones (13W-opt) and the 10eW-opt+ complex, by replacing the adamantyl groups with methyl ones (14W-opt+). As shown in Figure S94, both the new structures display acute N–N–LA angles (139.0° for 13W-opt and 131.8° for 14W-opt), pointing out that the main reason for the observed bent geometry must not be attributed to sterically induced repulsions but rather to electronic factors. The computed Wiberg bond indexes (Table S12) are in accordance with the experimental and computed geometrical parameters. While for the N2–N1 bond the Wiberg indexes decrease from 2.52 (3W-opt) to 2.10 (10eWBArF-opt) to 2.04 (11W-opt), for the W–N2 bond, on the other hand, they increase, from 0.97 (3W-opt) to 1.28 (10eWBArF-opt) to 1.33 (11W-opt). This LA-induced N2 activation correlates well with the lower energies found for the computed μ-N–N asymmetric stretching vibrations of 11W-opt and 10eWBArF-opt (1904 and 1880 cm–1, respectively) compared to 3W-opt (2011 cm–1).

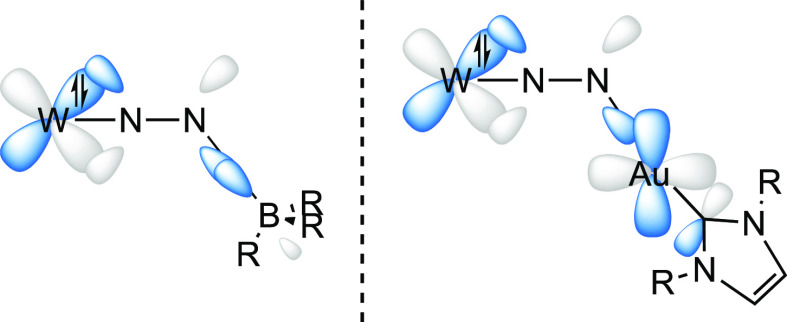

Considering a valence bond approach, the bonding situation in complexes 11W-opt and 10eWBArF-opt falls between two extremes, that are on one side a linear W–N2–N1–LA geometry with the N1 atom sp hybridized in a borata- or auryl-diazenium ligand and on the other side a W–N2–N1–LA bent geometry with the N1 atom sp2-hybridized in a borata- or auryl diazenido ligand (Figure 7).53

Figure 7.

Lewis structures extrema for 11W and 10eW+: diazenium vs diazenido ligand.

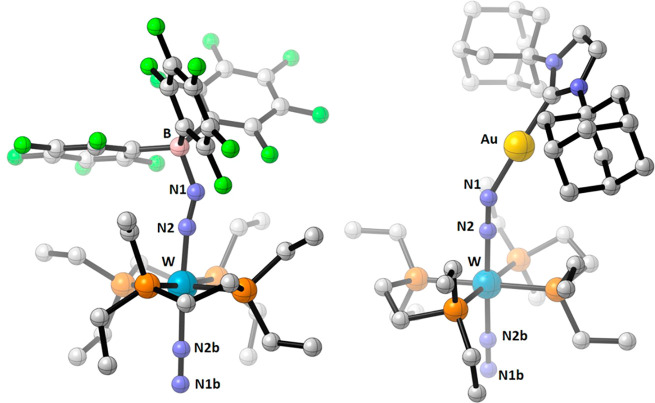

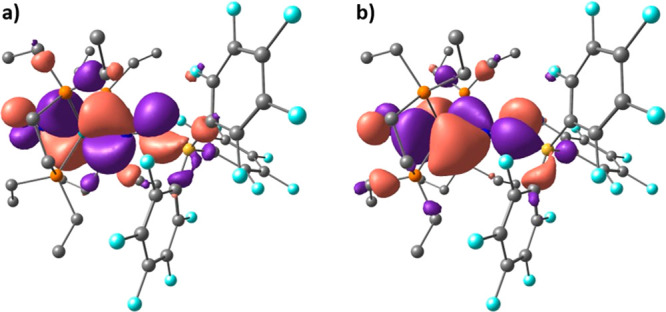

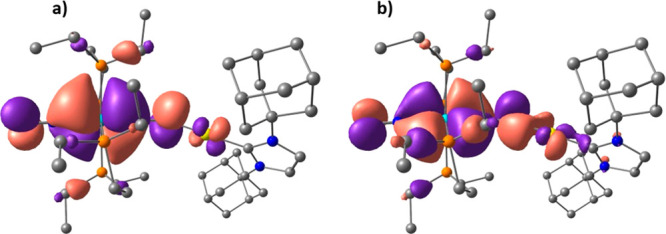

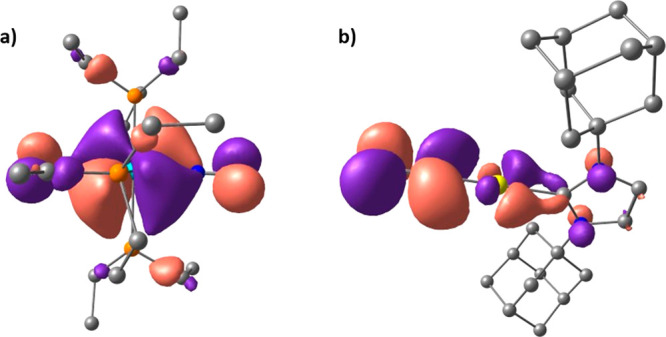

To shed light on this ambiguous situation, we computed the molecular orbitals of compounds 11W-opt and 10eWBArF-opt. For complex 11W-opt, while the HOMO is essentially nonbonding at tungsten (Figure S95), the energetically close HOMO–1 and HOMO–2 orbitals show a strong back-bonding donation from a filled W(depe)2 d orbital to an unfilled N2 π* orbital, displaying a significant W–N π-bonding character, indicative of a multiple bonding between the W and the N2 atom (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

DFT-computed molecular orbitals of complex 11W-opt: (a) HOMO–1; (b) and HOMO–2.

While in the HOMO–1 orbital, the back-bonding donation involves the W(depe)2d and the N2 π* orbitals which are perpendicular to the N2–N1–B plane, in the HOMO–2 orbital, on the other hand, the back-bonding donation involves the W(depe)2 d and N2 π* orbitals which are coplanar to the N–N–B plane. In both the HOMO–1 and HOMO–2 molecular orbitals, interestingly, an overlap between a μ-N2 π* lobe and a B sp3 orbital is observed. As described by Szymczak et al.,11e this interaction is likely to lower the energy of the π* orbital in N2, leading to an augmented back-bonding donation from the W(depe)2 fragment. In compound 11W, therefore, the presence of a bent rather than linear N2–N1–B bond angle (148.4° and 145.5° in 11W and 11W-opt, respectively) maximizes the overlap between the B sp3 orbital and a lobe of the μ-N2 π* orbital, the extent of the N2–N1–B bending being likely correlated with the steric properties of the boron substituents. Akin to 11W-opt, the HOMO of 10eWBArF-opt is essentially a tungsten-localized nonbonding orbital (Figure S95), whereas the HOMO–1 and HOMO–2 show the back-bonding donation from the W(depe)2 to the N2 unit, with a significant W–N π-bonding character reflecting a multiple bonding between the W and the N2 centers (Figure 9). It is worth underlining here that the nonbonding nature of the HOMO d orbital in both 10eWBArF-opt and 11W-opt strongly evokes the electronic structure of the SiMe3+ adduct of the iron(0) dinitrogen complex [Fe(N2)(depe)2] computed by the group of Ashley.46 Like in compound 11W-opt, the HOMO–1 and HOMO–2 orbitals of complex 10eWBArF-opt (Figure 9) involve the W(depe)2 d and the N2 π* orbitals which are perpendicular and coplanar to the N2–N1–Au plane, respectively. In the HOMO–2 orbital, interestingly, one lobe of the μ-N2 π* orbital overlaps with a lobe of the Au+ sd vacant orbital, partially contributing to the N1–Au+ bond interaction. In contrast with compound 11W-opt in which both the HOMO–1 and HOMO–2 orbitals are bonding with respect to the N1–LA bond, in 10eWBArF-opt this is the case for only the HOMO–2 since the HOMO–1 orbital displays an antibonding N1–Au+ interaction (Figure S96). This, added to the fact that the overlap between the Au+ sd orbital with the π* orbital of μ-N2 is not optimal, may account for the experimentally observed higher lability of the N2 gold adduct compared to the N2 boron analogue.

Figure 9.

DFT calculated molecular orbitals of complex 10eWBArF-opt: (a) HOMO–1 and (b) HOMO–2. The [BArF]– anion has been omitted for clarity.

In the HOMO–2 orbital of 10eWBArF-opt, in addition, the same Au+ sd orbital which overlaps with the N2 π* orbital is in turn involved in a π-backbonding donation with the p orbital of the carbenic carbon atom. Over recent years, the π-acceptor ability of NHCs in gold(I) complexes has received considerable attention with several experimental and theoretical studies aimed at characterizing it.54 As shown in Figure 10, indeed, the vacant Au+ sd orbital is likely to interact at the same time with (i) the π* orbital of the bridging N2 molecule and (ii) the p orbital of the carbon atom of the NHC ligand. In the HOMO–2 orbital, interestingly, the bent N–N–Au geometry (142.6° and 148.8° in 10eWBArF and 10eWBArF-opt respectively) allows the Au+ sd orbital to improve the overlap with a lobe of the μ-N2 π* orbital, providing a push–pull force in the N2 activation process.

Figure 10.

Simplified frontier orbital depiction accounting for the W–N–N–LA bonding interaction with localized MOs.

In order to get a deeper insight into the nature of this μ-N2 π*–Au+ sd interaction, we decided to compare the molecular orbitals of 10eWBArF-opt with those of the corresponding [W(depe)2(N2)2] (3W-opt) and [(N2)Au(IAd)]+ fragments. As shown in Figure 11, the HOMO–2 orbital of 3W-opt displays a strong back-bonding donation from a filled W(depe)2 d orbital to an unfilled N2 π* orbital, like the one observed in the HOMO–2 orbital of the 10eWBArF-opt complex. The [(N2)Au(IAd)]+ fragment, on the other hand, displays a linear N–N–Au+ geometry, which reflects the presence in its LUMO of an unfilled N2 π* orbital. A careful analysis of this LUMO orbital shows an antibonding interaction between the unfilled N2 π* orbital and the vacant Au+ sd coplanar orbital. When the [W(depe)2(N2)2] and [(N2)Au(IAd)]+ fragments interact, the W(depe)2 d orbital may fill by back-bonding donation the N2 π* orbital of the [(N2)Au(IAd)]+ cation, inducing a bend in the N–N–Au+ angle. This N–N–Au+ bent geometry may thus allow a partial overlap of the filled N2 π* and the vacant Au+ sd orbitals, the N2 π*–Au+ sd interaction switching from antibonding to partially bonding.

Figure 11.

DFT calculated molecular orbitals of the [W(depe)2(N2)2] and [(N2)Au(IAd)]+ fragments: (a) HOMO–2 of the [W(depe)2(N2)2] moiety. (b) LUMO of the [(N2)Au(IAd)]+ cation.

The frontier orbitals reflect therefore a partial sp2 hybridization of the N1 atom, underlining the predominance of the borata- or auryl diazenido form in Figure 9, due to the LA-induced push–pull effect. A careful analysis of the deeper orbitals has shown that other types of orbital overlaps also account for the N1–LA bond (Figures S97 and S98). These interactions, however, do not allow an understanding of the origin of the N2–N1–LA distortion, which is mainly related to the filling of the μ-N2 π* orbital occurring in the frontier orbitals. Another proof of the LA-induced N2 activation is given by the increase of μ-N2 polarization as attested by the natural charges computed via an NBO analysis (Table S13). Importantly, and in line with the results of Szymczak and co-workers,11e the negative charge of the μ-N2 terminal nitrogen (N1) increases from −0.1 in 3W-opt to −0.19 in 11W-opt to −0.35 in 10eWBArF-opt, and so does the N1–N2 charge difference from ΔN1–N2 = 0.015 in 3W-opt to 0.31 in 11W-opt to 0.45 in 10eWBArF-opt. In the latter compound, interestingly, the much higher negative charge on the μ-N2 terminal nitrogen (N1) suggests that an electrostatic contribution may also account for the N1–Au+ interaction. We have therefore embarked on the calculation of the natural charge of the entire LA acceptor fragment for complexes 11W-opt and 10eWBArF-opt, and we have estimated the force of the electrostatic interaction by comparing the charge separation between the μ-N2 terminal atom (N1) and the whole LA acceptor group. While the natural charge of the B(C6F5)3 group in complex 11W-opt amounts to −0.44, that of the Au+–NHC unit in complex 10eWBArF-opt measures 0.63, providing in the latter a charge separation between the terminal N1 atom and the Au+–NHC moiety of ΔN1–LA = 1.00. This high level of polarization indicates that the μ-N2–Au+ bond has an important electrostatic component, which may in part explain the undesired redox events that have led in some instances to Au(0) and paramagnetic W species (vide supra).

Reactivity Study of [W(N2)(depe)2(μ-N2)Au(NHC)]+ Adducts in Solution and Isolation of a Tungsten Decomposition Product

To assess whether the rapid decomposition of complexes 10b–eWBArF precluded their use in dinitrogen transformation reactions, we formed the adducts in situ in chlorobenzene-d5 and added immediately 1 equiv of unsaturated organic substrates of various natures at RT, having in mind to exploit the carbophilic properties of gold to promote N2 functionalization via N–C bond formation. According to NMR and GC-MS analysis of the solution, 2-butyne, 3-methyl-1,2-butadiene, or diisopropylcarbodiimide did not react while the adducts decomposed to mixtures of paramagnetic materials. Surprisingly, under the same conditions, we observed a deuteration of the olefinic protons of 1-octene with full deuteration of the hydrogen atom in the 2-position and partial deuteration at the 1-position after 18 h at RT with 10dWBArF, as evidenced by 1H NMR spectroscopy and GC-MS analysis (most abundant ion: 113.13 m/z = 1-octene +1). Up to 20 equiv of 1-octene can be deuterated in the presence of 10dWBArF at RT in cholorobenzene-d5, with 90% and 35% conversion of the 2- and 1-positions, respectively, after 5 days. While neither 3W nor gold cations alone react with 1-octene, the H/D exchange is unlikely to be catalyzed by the adducts considering that the activity of the reaction is unrelated to the evolution of the adducts’ concentration as they decompose.

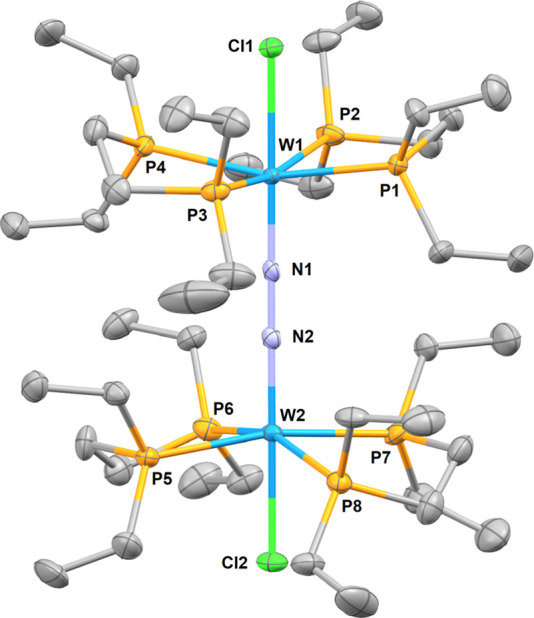

Attempts to isolate or characterize the species formed from the decomposition of the gold adducts in the presence of the organic substrate have been mostly unsuccessful at the exception of the dinuclear salt [{W(Cl)(depe)2}2(μ-N2)][BArF]2 formed in ca. 40% yield (relative to W content) as deep green crystals precipitating out of the reaction solutions over a period of days in the presence of 3-methyl-1,2-butadiene or diisopropylcarbodiimide. While sufficient to identify this species with good confidence, the low quality of these crystals did not allow for a full structural resolution by X-ray diffraction analysis and their very poor solubility in usual solvent hindered recrystallization attempts. In the presence of organic substrates, isolated adduct 10dWBArF solubilized in chlorobenzene at RT afforded the W(II) complex in similar yield to that for adducts formed in situ from the reaction of 3W with Na[BArF] and [Au(Cl)(NHC)]; such a result would suggest that the chloride atoms originate from chlorobenzene. To strictly rule out the sourcing of the chloride ligand from a trace amount of NaCl, we synthesized [Au(NTf2)(Me2Idipp)] (6bNTf2), following a literature procedure.30 This complex reacts immediately with 1 equiv of 3W at RT in chlorobenzene-d5 to afford [W(N2)(depe)2(μ-N2)Au(Me2Idipp)][NTf2] 10bWNTf2, characterized in solution by almost identical 1H and 31P NMR and IR (νNN = 1796 cm–1 in PhCl) spectroscopic signatures to those of 10bWBArF. By contrast, reaction of 6bNTf2 with 2W affords only a minor quantity of the putative adduct [W(N2)(dppe)2(μ-N2)Au(Me2Idipp)][NTf2], as the displacement of the more coordinating NTf2 anion by 2W is very slow (<20% after 24 h) and evolves to a mixture of paramagnetic materials upon longer reaction times or a temperature increase to 45 °C.

In chlorobenzene, 10bWNTf2 decomposes to an intractable mixture from which deep green crystals had formed after 2 days at RT. Structural determination by X-ray diffraction allowed the identification of these green crystals as the complex [{W(Cl)(depe)2}2(μ-N2)][NTf2]2 (15W[NTf2]2). In contrast with its [BArF]− counterpart, decomposition of 10bWNTf2 led to the formation of these characteristic green crystals even in absence of organic substrates; the weakly coordinating NTf2 anion is therefore assumed to play a similar role to the weakly coordinating organic substrates in the decomposition process. The homobimetallic dication [{W(Cl)(depe)2}2(μ-N2)]2+ depicted in Figure 12 features a linear (Cl–W)2(μ-N2) motif with short W–N distances (1.815(5), 1.804(5) Å) and a long N–N bond length (1.273(7) Å) that are almost identical to the dimension of the previously reported {Cp*W[N(iPr)C(Me)N(iPr)]}2(μ-N2)55 and consistent with an electronic configuration lying somewhere between a pair of W(II) centers bridged by an activated (N2)0 ligand and a pair of W(IV) centers bridged by a (N2)4– group.

Figure 12.

Molecular structure of [{W(Cl)(depe)2}2(μ-N2)]2+ (15W2+) in the solid state (ellipsoids are drawn at the 50% probability level, hydrogen atoms, and NTf2 anions are omitted for clarity). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg): W1–Cl1 2.4550(16), W1–N1 1.816(5), N1–N2 1.272(7), W2–N2 1.805(5), W2–Cl2 2.4663(16), Cl1–W1–N1 179.34(18), N2–W2–Cl2 178.93(18), W1–N1–N2 179.0(5), W2–N2–N1 179.3(5).

Evidently, the formation of 15W[NTf2]2 from 10bWNTf2 results from the activation of chlorobenzene; this assumption can be confirmed by GC-MS analysis of the mixture after the formation of 15W[NTf2]2 allowing the identification of the major organic residue present in solution as isomers of chlorobenzene coupling compounds Ph–Ph, Ph–C6H4Cl, and C6H4Cl–C6H4Cl (see the Supporting Information, pp 8–9). A plausible explanation for such observation could be the initial oxidation of the W center by the gold cation followed by the generation of aryl radicals. However, the formation of multiple paramagnetic materials resisting the characterization attempts and Au(0) propensity to form nanoparticles did not allow us to make any meaningful proposition regarding the mechanism responsible for the formation of biaryls and 15W[NTf2]2.

Summary and Conclusions

To assess whether gold’s well-known carbophilicity could be exploited to promote new transformation of N2, the coordination properties and electronic compatibility of [AuI(NHC)] cations with zerovalent group 6 dinitrogen complexes trans-[M(dppe)2(N2)2] (2M), trans-[M(depe)2(N2)2] (3M), and [M(PMe2Ph)4(N2)2] (4M) were explored (M = Mo or W). Unprecedented M(μ-N2)–Au+ Lewis pairs have been observed by spectroscopic methods. Heterobimetallic complexes [W(N2)(dppe)2(μ-N2)Au(NHC)][BArF] [NHC = Idipp (7aWBArF); Me2Idipp (7bWBArF)] and [W(N2)(depe)2(μ-N2)Au(NHC)][BArF] [NHC = Me2Idipp (10bWBArF); IMes (10cWBArF); ItBu (10dWBArF); IAd (10eWBArF)] have been obtained from the reaction of the N2 complex with the appropriate [Au(NHC)] cation generated in situ from [Au(Cl)(NHC)] and Na[BArF] and could be isolated in satisfying yields and purity, while the adducts formed with the Mo complexes have shown poor solution stability, precluding isolation. Indeed, the formation of the targeted gold adducts have been shown to be in competition with multiple side reactions, resulting in short-lived adducts in most conditions and an extreme sensitivity of the few characterizable heterobimetallic complexes discussed in this study. Gold coordination to N2 is weaker than that to phosphines, which results readily in phosphine abstraction to form heteroleptic gold complexes driven by either the relief of steric crowding or weak coordination to the group 6 metal and favored when the gold center bears low steric bulk. These reactions can be mitigated by the use of chelating phosphines and/or bulky NHCs but are responsible nevertheless for the lack of long-lived characterizable molybdenum complexes, whose coordination by phosphines is weaker than tungsten. The use of a bulky substituent at gold’s NHC ligand can lead to weak N2 coordination as seen with 7aWBArF and 7bWBArF that readily decompose to trans-[W(dppe)2(N2)2] as a result of gold dissociation and subsequent decomposition. Likewise, the use of the more electron donating depe ligands for the dinitrogen complex prevents gold dissociation as a result of a more electron-rich N2 ligand. However, this also favored electron transfers from the group 6 metal to the gold cations to lead gradually to mixtures of paramagnetic materials. In the sufficiently long-lived adducts 7a—bWBArF and 10a–eWBArF, the push–pull activation of the bridging N2 ligand is weak to moderate as characterized by the ΔνNN ranging from −95 cm–1 to −160 cm–1, with higher degrees of N–N bond weakening found when the least hindered gold cation was employed.