Preclinical studies have suggested that transplanted human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte (hPSC-CM) grafts expand due to proliferation.1 This knowledge came from cell cycle activity measurements that cannot discriminate between cytokinesis or DNA synthesis associated with hypertrophy. To refine our understanding of hPSC-CM cell therapy, we genetically engineered a cardiomyocyte-specific fluorescent barcoding system into an hPSC line. Since cellular progeny have the same color as parental hPSC-CMs, we could identify subsets of engrafted hPSC-CMs with greater clonal expansion.

HPSC lines were generated by knocking four copies of the Cre-dependent Brainbow 3.2 lineage reporter2 into WTC11 cells (Figure A). These rainbow hPSCs were transduced with cardiac troponin T (cTnT)-driven Cre, which restricts expression of the rainbow barcoding system to committed cardiomyocytes (Figure A). Rainbow-labeling was observed after 7 days of differentiation, and immunostaining confirmed that labeled cells express cTnT (Figure B). A sparse labeling strategy was used to avoid expression of the same color code in neighboring cells, hence permitting single cell tracking over time (Figure C). Cre-mediated recombination elicited all eighteen of the possible hues (Figure D).

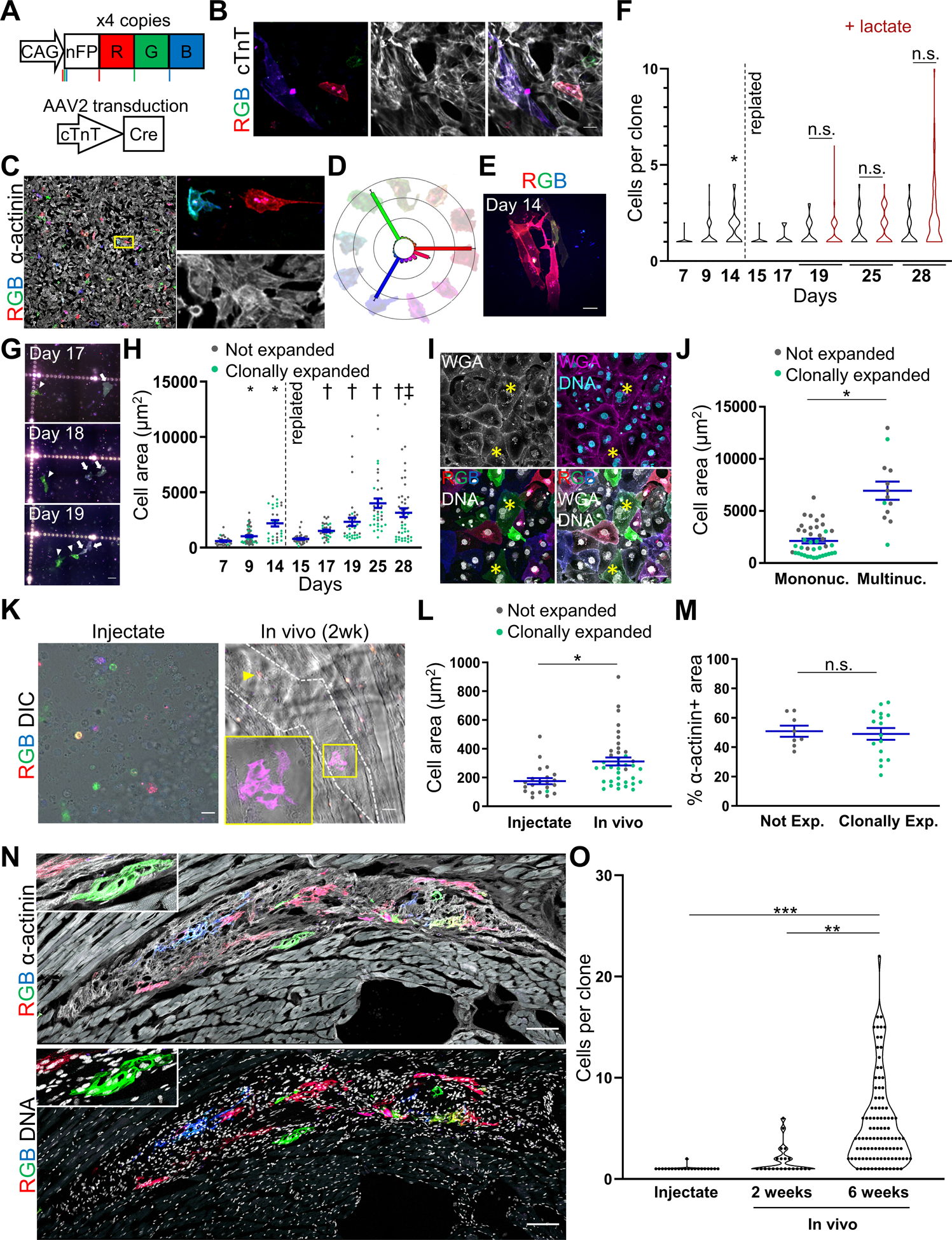

Figure. Select cardiomyocytes clonally expand in vitro and in vivo.

(A) Schematic of rainbow hPSC WTC11 line with four copies of the rainbow construct and cTnT-activated labeling. Before expression of Cre recombinase, rainbow hPSCs express a non-fluorescent GFP mutant (nFP). By means of the Cre-lox recombination system, gene excision may occur randomly at either the loxP (red vertical bars), lox2 (green vertical bars), or loxN (blue vertical bars) sites, resulting in expression of one of three fluorescent proteins: mOrange2 (shown as red), eGFP (shown as green), and mKate2 (shown as blue). Cells were labeled after they committed to the cardiomyocyte lineage by using an AAV plasmid (Addgene 69916) with ITR sequences flanking a cardiac troponin T promoter upstream of the Cre and TdTomato genes. TdTomato was excised by NotI digestion and the resulting construct used for AAV serotype 2 (AAV2) production. AAV2 was added to rainbow hPSCs on differentiation day 0 of a modified directed differentiation protocol.1 (B) Rainbow-labeled hPSC-CMs express cTnT protein, scale bar is 20 μm. On day 14, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and stained for cTnT (ThermoFisher MA5–12960). Imaging was performed on a Nikon TiE equipped with Yokogawa W1 spinning disk confocal system and high sensitivity EMCCD camera. (C) Representative image of sparsely labeled rainbow hPSC-CMs on day 9 and stained for α-actinin (Sigma A7811), scale bar is 200 μm. AAV2 was serially diluted to determine optimal dose for sparse labeling. Images were collected on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope with fixed laser lines and a spectral detector. (D) Images were analyzed on a per pixel basis and binned by the eighteen possible hues using a custom generated MATLAB code. Examples of rainbow hPSC-CMs expressing different hues are shown around the color wheel. (E) Clonally expanded rainbow hPSC-CMs at day 14 in the differentiation, scale bar is 10 μm. (F) Quantification of rainbow hPSC-CM clonal expansion over time and after replating on day 14. Cultures that were lactate selected on Days 18–22 are colored in red. At least 24 clones were analyzed per condition. * indicates p < 0.05 versus Day 7. (G) Time lapse imaging of cells that were dissociated into single-cell suspensions and replated rainbow hPSC-CMs showing cell proliferation, scale bar is 40 μm. Arrow points to a hPSC-CM that divides between day 17 and 18, arrowhead points to a hPSC-CM that divides between day 18 and 19. (H) Cell area in non-expanded (i.e., singlets) and clonally expanded hPSC-CMs (i.e., ≥ 2 cells) are color coded gray or green, respectively. * indicates p < 0.05 versus Day 7, † indicates p < 0.05 versus Day 15, and ‡ indicates p < 0.05 Not expanded versus Clonally expanded at Day 28. (I) Rainbow hPSC-CMs stained for wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) and DNA show instances of multinucleation, indicated by asterisks, scale bar is 20 μm. (J) Quantification of cell area as a function of the number of nuclei per cell for rainbow hPSC-CMs on day 28. Non-dividing and clonally expanded hPSC-CMs are labeled in gray or green, respectively, * indicates p < 0.05. (K) Left, image of the injectate 2 hours after preparation shows sparse labeling of rainbow hPSC-CMs, scale bar is 20 μm. Right, imaging of host rat heart with engrafted hPSC-CMs 2-weeks after injection, graft region is marked by dashed lines. Arrowhead points to a singlet rainbow hPSC-CM, box and inset show clonally expanded hPSC-CM, scale bar is 40 μm. On day 14, sparsely labeled rainbow hPSC-CMs were resuspended in Matrigel plus a prosurvival cocktail (50 million cells/mL). Athymic male Sprague Dawley rats (rnu-rnu, 250–300 g, Harlan) were administered 5 mg/kg cyclosporin for seven days, starting a day prior to the engraftment procedure. Animals received 1 mg/kg sustained-release buprenorphine, were induced with inhaled isoflurane, and mechanically ventilated during lateral thoracotomy to expose the left ventricle where three injections were preformed to deliver 5 million cells in total. Hearts were perfused with KB cardioplegia buffer followed by 4% PFA, additionally fixed with 4% PFA overnight, washed with PBS, mounted in OCT (Tissue-Tek) for cryosectioning of 10 μm thick specimens that were stained and analyzed as described above. (L) Quantification of cell area in engrafted rainbow hPSC-CMs 2 weeks after engraftment and comparison to injectate. * indicates p < 0.05. (M) Quantification of α-actinin content normalized by cell area for engrafted rainbow hPSC-CMs that did not divide or clonally expanded. Images were analyzed in ImageJ to quantify the area of α-actinin and then dividing by the total cell area. (N) Image of rainbow reporter hPSC-CMs 6 weeks after engraftment costained with, α-actinin (top), and DNA (bottom). Inset shows higher magnification. Scale bars are 100 μm. (O) Quantification of clonal expansion at 2 weeks and 6 weeks after engraftment. ** indicates p < 0.001, *** p < 0.0001. Statistics: scRNAseq analysis and quantification was performing using 10x Genomics Cell Ranger, Loupe Browser, and Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple tests. GraphPad Prism V8 was used for two-tailed unpaired t-tests (Figures H (Clonally expanded versus not expanded at Day 28) J, M, and N), one-Way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc tests (Figure O), and one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey Test (Figures F and H). A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Each quantification was derived from a minimum of 3 independent experiments (different passages for in vitro experiments or different animals in in vivo studies). All average values described in the text and figures are mean values and error bars represent standard error of the mean.

By day 14, hPSC-CMs had clonally expanded (Figure E). On average, the number of cardiomyocytes per clone went from 1.03 to 1.71 (day 7 versus 14, p<0.03, Figure F). While most rainbow hPSC-CMs had not proliferated, some were highly proliferative and a subset of hPSC-CMs continued to proliferate after replating at day 14 (Figure F), including hPSC-CMs that were lactate selected. Repeat imaging of replated hPSC-CMs over days 15–28 confirmed that neighboring cells had unique hues and daughter cardiomyocytes inherited the parental fluorescent-barcode (Figure G), definitively demonstrating these clusters arise from clonal expansion. We observed that hPSC-CM displayed limited cell migration (Figure G) and underwent hypertrophic growth as measured by cell area (Figure H). At day 28, clonally expanded hPSC-CMs were 4.07-fold smaller than non-dividing hPSC-CMs (p<0.0001, Figure H). Staining confirmed rainbow labeling demarcated cardiomyocytes and showed multinucleation in non-dividing, hypertrophied hPSC-CMs (Figures I and J). Consistent with the subset of clonally expanded hPSC-CMs, we conducted unbiased graph-based clustering on raw single cell RNA sequencing data3 from isogenic day 15 and day 30 WTC11 hPSC-CMs and found a unique subset (686 of 18073 cells) with increased mitosis and cytokinesis gene expression (AURKB, CDK1, CCNB1, 5.54 to 6.18-fold increase versus all cells, p<0.0001). These results suggest the heterogeneity in hPSC-CM proliferation may be regulated transcriptionally.

For the transplantation studies, sparsely labeled day 14 hPSC-CMs were dissociated, resuspended in Matrigel with prosurvival cocktail, and transplanted into the hearts of immune-compromised athymic rats.1 All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institute of Health and was approved by the University of Washington institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC protocol # 4376–01). TUNEL staining demonstrated 17.8 ± 2.6% of hPSC-CMs underwent apoptosis 24-hours post injection. Two weeks after engraftment, most hPSC-CMs hypertrophied (1.75-fold increase versus injectate, p<0.002) while some subsets clonally expanded (Figures K and L). To ensure that the results were not driven by false positives, the cell injectate was imaged to confirm that neighboring hPSC-CMs did not express the same barcode at the time of transplantation (Figure K). Differences in proliferative potential among engrafted hPSC-CMs was not due to differences in sarcomere content, as the proportion of α-actinin+ area was the same in both clonally expanding and non-expanding groups (p>0.77, Figure M). After 6 weeks of engraftment, cumulative clonal expansion increased further, demonstrating hPSC-CMs continue to proliferate in vivo at later timepoints, with the average number of cells per clone being 1.05 (injectate), 1.77 (2 weeks), and 5.41 (6 weeks, p < 0.001 versus 2 weeks, p < 0.0001 versus injectate, Figures N and O). Notably, the heterogenous amount of clonal expansion among engrafted hPSC-CMs would not have been observed without the rainbow single-cell reporter.

As hPSC-CM therapy is rapidly approaching clinical use, it is critical to understand how these cells behave in vivo. Single cell transcriptomics assays3 and DNA content analysis4 have revealed profound molecular heterogeneity among hPSC-CMs. By generating a cTnT lineage rainbow reporter longitudinal tracking of the hypertrophic and proliferative growth of individual hPSC-CMs is now possible. This approach demonstrated that hPSC-CMs have heterogeneous levels of proliferation in vitro and after engraftment in host myocardium. By examining the generation of newly formed cardiomyocytes, rather than utilizing proxies for cell proliferation, this study distinguished bona fide cardiomyocyte division versus incomplete cell cycle activation. The heterogenous proliferative capacity among hPSC-CMs is consistent with findings that demonstrated only a few clonally dominant cardiomyocytes generate most of the adult zebrafish heart5, suggesting a similar mechanism may underlie hPSC-CM graft expansion. Proliferative hPSC-CM express normal levels of sarcomere contractile elements, suggesting increased hPSC-CM clonal expansion could efficiently repopulate myocardium lost to injury. This is in line with cardiac cell therapy optimizations, such as co-transplantation of hPSC-CMs with epicardial cells1, demonstrating improved outcomes from stimulating grafted hPSC-CM proliferation, though graft cell function and clinical relevance remains uncertain. Thus, controlling engrafted hPSC-CM clonal expansion holds promise for improving cardiac regenerative therapies. With respect to data sharing, all data and materials will be available from the corresponding author by request.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by NIH HL141187 & HL142624 (J.D.), NSF CMMI-1661730 (N.J.S.), NIH F32HL143851 (D.E.), NIH T32AG066574 (D.B.), Gree Family Gift (J.D./N.J.S./C.E.M.). C.E.M. was also supported by NIH grants R01HL128362, U54DK107979, R01HL128368, R01HL141570, R01HL146868, and a grant from the Foundation Leducq Transatlantic Network of Excellence.

Footnotes

Disclosures

C.E.M. is a founder and equity holder in Sana Biotechnology. C.E.M. and D.E. hold patents related to heart regeneration technology. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bargehr J, Ong LP, Colzani M, Davaapil H, Hofsteen P, Bhandari S, Gambardella L, Le Novère N, Iyer D, Sampaziotis F, Weinberger F, Bertero A, Leonard A, Bernard WG, Martinson A, Figg N, Regnier M, Bennett MR, Murry CE, Sinha S. Epicardial cells derived from human embryonic stem cells augment cardiomyocyte-driven heart regeneration. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:895–906. DOI: 10.1038/s41587-019-0197-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai D, Cohen KB, Luo T, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR. Improved tools for the Brainbow toolbox. Nat Methods. 2013;10:540–7. DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman CE, Nguyen Q, Lukowski SW, Helfer A, Chiu HS, Miklas J, Levy S, Suo S, Han J-DJ, Osteil P, Peng G, Jing N, Baillie GJ, Senabouth A, Christ AN, Bruxner TJ, Murry CE, Wong ES, Ding J, Wang Y, Hudson J, Ruohola-Baker H, Bar-Joseph Z, Tam PPL, Powell JE, Palpant NJ. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Cardiac Differentiation from Human PSCs Reveals HOPX-Dependent Cardiomyocyte Maturation. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:586–598. DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lundy SD, Zhu W-Z, Regnier M, Laflamme MA. Structural and Functional Maturation of Cardiomyocytes Derived from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:1991–2002. DOI: 10.1089/scd.2012.0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta V, Poss KD. Clonally dominant cardiomyocytes direct heart morphogenesis. Nature. 2012;484:479. DOI: 10.1038/nature11045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]