Abstract

The notion that the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may lead to adverse outcomes upon acquisition of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) should be discredited with a review of the real-life evidence. We aimed to perform a meta-analysis to summarize the risk of mortality with the preadmission/pre-diagnosis use of NSAIDs in patients with COVID-19. A systematic literature search was performed to identify eligible studies in electronic databases. The outcome of interest was the development of a fatal course of COVID-19. Adjusted hazard ratio or odds ratio/relative risk and the corresponding 95% confidence interval from each study were pooled using a random-effects model to produce pooled hazard ratio and pooled odds ratio, along with 95% confidence interval. The meta-analysis of 3 studies with a total of 2414 patients with COVID-19 revealed no difference in the hazard for the development of a fatal course of COVID-19 between NSAID users and non-NSAID users (pooled hazard ratio = 0.86; 95% confidence interval 0.49–1.51). Therefore, NSAIDs should not be avoided in patients who are appropriately indicated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Kelleni (2020) reviewed the evidence surrounding the notion that the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ibuprofen, may lead to adverse outcomes upon acquisition of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), due to their potential to increase the expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the entry receptor of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). While the author had argued conscientiously to discredit such a claim, it may not be convincing without a review of the real-life evidence. We aimed to perform a meta-analysis to summarize the risk of mortality with the preadmission/pre-diagnosis use of NSAIDs in patients with COVID-19.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed to identify eligible studies in electronic databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and preprint servers (medRxiv, Research Square, SSRN) with no language restriction published up to April 05, 2021. The search strategy was built based on the following keywords and their MeSH terms: “COVID-19”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “non-steroidal”, “NSAID”, and “ibuprofen”. Two investigators (CSK and SSH) independently performed the systematic literature screening. The reference lists of relevant articles were also manually searched for additional studies. Studies eligible for inclusion were studies with any design that investigated the preadmission/pre-diagnosis of the use of NSAIDs on the risk of a fatal course of COVID-19 and reported adjusted measures of association. We excluded editorials or narrative reviews without original data. In addition, studies that provided no adjusted estimation were also excluded. Two investigators (CSK and SSH) independently evaluated the quality of observational studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (Wells et al. 2013), with a score of > 7 indicating high quality.

The outcome of interest was the development of a fatal course of COVID-19. Each included trial was independently evaluated by two investigators (CSK and SSH) who extracted the study characteristics. Data collected included authors, study design, country, patients’ age, the total number of included patients, mortality events, and adjusted mortality estimate. The disagreement between the two investigators related to the inclusion of studies, extraction of data, and quality appraisal of included studies was resolved through mutual discussions. Adjusted hazard ratio or odds ratio/relative risk and the corresponding 95% confidence interval from each study were pooled using a random-effects model to produce pooled hazard ratio and pooled odds ratio, along with 95% confidence interval. We examined the heterogeneity across studies using the I2 statistics and the χ2 test, with 50% and P < 0.10, as the respective threshold for statistically significant heterogeneity. All analyses were performed using Meta XL, version 5.3 (EpiGear International, Queensland, Australia).

Results and discussion

Our literature search yielded 435 unique abstracts. After application of the eligibility criteria, nine relevant articles underwent full-text examination for potential inclusion. Of these, three studies were excluded, since they did not report adjusted measures of association or they did not report mortality outcomes. Two studies utilized the same data set; we included the study with the most recent record. Therefore, five studies (Abu Esba et al. 2020; Bruce et al. 2020; Imam et al. 2020; Lund et al. 2020; Park et al. 2021) were included for this meta-analysis; three studies (Imam et al. 2020; Lund et al. 2020; Park et al. 2021) were retrospective in design, with one multicentered study (Imam et al. 2020) and two database reviews (Lund et al. 2020; Park et al. 2021); the remaining two studies (Abu Esba et al. 2020; Bruce et al. 2020) were prospective in design. Each of the included studies was originated from different countries: the United Kingdom (Bruce et al. 2020), the United States (Imam et al. 2020), Saudi Arabia (Abu Esba et al. 2020), Denmark (Lund et al. 2020), and South Korea (Park et al. 2021), and they are deemed moderate-to-high quality with a Newcastle–Ottawa Scale of 8 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristic of included studies

| Study | Country | Design | Total number of patients | Age (median/mean unless otherwise specified) | Mortality | Covariates adjustment | NOS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSAID users (n/N; %) |

Non-NSAID users (n/N; %) |

Adjusted estimate (95% CI) |

|||||||

| Imam et al. (2020) | United States | Retrospective, multicenter | 1305 | All patients = 61.0 (16.3) | N/A | N/A |

OR = 0.57 (0.40–0.82) |

Age, race, body mass index, renin-angiotensin system inhibitor use, Charlson Comorbidity Index, comorbidities | 8 |

| Park et al. (2021) | South Korea | Retrospective database review | 794 | N/A | 16/397 (4.0) | 12/397 (3.0) |

HR = 1.33 (0.63–2.88) |

Age, comorbidities | 8 |

| Abu Esba et al. (2020) | Saudi Arabia | Prospective, multicenter | 453 |

NSAID users = 57 (38.5–67.5) Non-NSAID users = 36 (27.0–49.0) |

6/96 (6.3) | 11/357 (3.1) | HR = 0.39 (0.13–1.16) | Age, sex, comorbidities | 8 |

| Lund et al. (2020) | Denmark | Retrospective database review | 1120 |

NSAID users = 54 (43–64) Non-NSAID users = 54 (41–66) |

14/224 (6.3) | 55/896 (6.1) |

RR = 1.02 (0.57–1.82) |

Age, sex, comorbidities, use of prescription drugs, phase of the outbreak | 8 |

| Bruce et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | Prospective, multicenter | 1167 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

HR = 0.89 (0.52–1.53) |

Age, sex, smoking status, C-reactive protein level, comorbidities, estimated glomerular filtration rate | 8 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, NOS Newcastle–Ottawa Scale NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, OR odds ratio, RR risk ratio

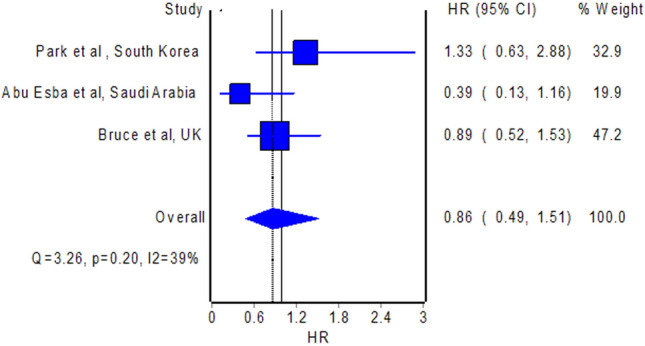

The meta-analysis of 3 studies with a total of 2414 patients with COVID-19 (Abu Esba et al. 2020; Bruce et al. 2020; Park et al. 2021) which presented effect measure as hazard ratio revealed no difference in the hazard for the development of a fatal course of COVID-19 between NSAID users and non-NSAID users (Fig. 1; pooled hazard ratio = 0.86; 95% confidence interval 0.49–1.51). Likewise, we observed no difference in the odds for the development of a fatal course of COVID-19 between NSAID users and non-NSAID users when we pooled the 2 studies with a total of 2425 patients with COVID-19 (Imam et al. 2020; Lund et al. 2020) which reported effect measure as odds ratio/risk ratio (pooled odds ratio = 0.73; 95% confidence interval 0.41–1.28). These preliminary findings are consistent with the findings of no increased risk of severe illness in the available studies to date. For instance, Kragholm et al. (2020) reported in their retrospective database review that patients with pre-diagnosis use of NSAIDs had no increased risk for a composite outcome of severe disease, intensive care unit admission, or death, relative to non-use of NSAIDs (risk ratio = 0.96; 95% confidence interval 0.72–1.23).

Fig. 1.

Pooled hazard ratio of mortality in patients with COVID-19 with pre-diagnosis use of NSAIDs versus non-use of NSAIDs

Nevertheless, the studies included in our meta-analysis are mostly of retrospective design, and thus, generalizability of the findings may be limited and should be substantiated by further large-scale prospective studies. In addition, it is not known with certainty whether our findings could be extrapolated to discredit the effectiveness of NSAIDs in patients with COVID-19, since the continued use of NSAIDs upon COVID-19 diagnosis could not be confirmed by the design of included studies. Three studies (Abu Esba et al. 2020; Martínez-Botía et al. 2021; Sahai et al. 2020) thus far investigated the acute use of NSAIDs during the course of COVID-19, but reported no mortality benefits. While the in-vitro inhibition of the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB by NSAIDs with potential interference in cytokine release (Smart et al. 2020) was further substantiated by the findings in a mouse model of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Chen et al. 2021), where NSAID treatment reduced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, it seems that such effects may not translate into mortality benefits, though clinical trials may be needed to confirm such effect.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abu Esba LC, Alqahtani RA, Thomas A, Shamas N, Alswaidan L, Mardawi G (2021) Ibuprofen and NSAID use in COVID-19 infected patients is not associated with worse outcomes: a prospective cohort study. Infect Dis Ther 10:253–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bruce E, Barlow-Pay F, Short R, Vilches-Moraga A, Price A, McGovern A, Braude P, Stechman MJ, Moug S, McCarthy K, Hewitt J, Carter B, Myint PK. Prior routine use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and important outcomes in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2586. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JS, Alfajaro MM, Chow RD, Wei J, Filler RB, Eisenbarth SC, Wilen CB (2021) Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs dampen the cytokine and antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Virol JVI.00014-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Imam Z, Odish F, Gill I, O'Connor D, Armstrong J, Vanood A, Ibironke O, Hanna A, Ranski A, Halalau A. Older age and comorbidity are independent mortality predictors in a large cohort of 1305 COVID-19 patients in Michigan, United States. J Intern Med. 2020;288:469–476. doi: 10.1111/joim.13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleni MT. ACEIs, ARBs, ibuprofen originally linked to COVID-19: the other side of the mirror. Inflammopharmacology. 2020;28:1477–1480. doi: 10.1007/s10787-020-00755-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kragholm K, Gerds TA, Fosbøl E, Andersen MP, Phelps M, Butt JH, Østergaard L, Bang CN, Pallisgaard J, Gislason G, Schou M, Køber L, Torp-Pedersen C. Association between prescribed ibuprofen and severe COVID-19 infection: a Nationwide Register-Based Cohort Study. ClinTranslSci. 2020;13:1103–1107. doi: 10.1111/cts.12904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund LC, Kristensen KB, Reilev M, Christensen S, Thomsen RW, Christiansen CF, Støvring H, Johansen NB, Brun NC, Hallas J, Pottegård A. Adverse outcomes and mortality in users of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2: a Danish nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Botía P, Bernardo Á, Acebes-Huerta A, Caro A, Leoz B, Martínez-Carballeira D, Palomo-Antequera C, Soto I, Gutiérrez L. Clinical management of hypertension, inflammation and thrombosis in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: impact on survival and concerns. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1073. doi: 10.3390/jcm10051073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Lee SH, You SC, Kim J, Yang K. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent use may not be associated with mortality of coronavirus disease 19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5087. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84539-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahai A, Bhandari R, Koupenova M, et al (2020) SARS-CoV-2 Receptors are expressed on human platelets and the effect of aspirin on clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Preprint. Research Square rs.3.rs-119031/v1.

- Smart L, Fawkes N, Goggin P, Pennick G, Rainsford KD, Charlesworth B, Shah N. A narrative review of the potential pharmacological influence and safety of ibuprofen on coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19), ACE2, and the immune system: a dichotomy of expectation and reality. Inflammopharmacology. 2020;28:1141–1152. doi: 10.1007/s10787-020-00745-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P (2013) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 13 Mar 2021