Abstract

Context:

The role of the rotator cuff is to provide dynamic stability to the glenohumeral joint. Human and animal studies have identified sarcomerogenesis as an outcome of eccentric training indicated by more torque generation with the muscle in a lengthened position. Objective: The authors hypothesized that a home-based eccentric-exercise program could increase the shoulder external rotators’ eccentric strength at terminal internal rotation (IR).

Design:

Prospective case series.

Setting:

Clinical laboratory and home exercising.

Participants:

10 healthy subjects (age 30 ± 10 y).

Intervention:

All participants performed 2 eccentric exercises targeting the posterior shoulder for 6 wk using a home-based intervention program using side-lying external rotation (ER) and horizontal abduction.

Main Outcome Measures:

Dynamic eccentric shoulder strength measured at 60°/s through a 100° arc divided into 4 equal 25° arcs (ER 50–25°, ER 25–0°, IR 0–25°, IR 25–50°) to measure angular impulse to represent the work performed. In addition, isometric shoulder ER was measured at 5 points throughout the arc of motion (45° IR, 30° IR, 15° IR, 0°, and 15° ER). Comparison of isometric and dynamic strength from pre- to posttesting was evaluated with a repeated-measure ANOVA using time and arc or positions as within factors.

Results:

The isometric force measures revealed no significant differences between the 5 positions (P = .56). Analysis of the dynamic eccentric data revealed a significant difference between arcs (P = .02). The percentage-change score of the arc of IR 25–50° was found to be significantly greater than that of the arc of IR 0–25° (P = .007).

Conclusion:

After eccentric training the only arc of motion that had a positive improvement in the capacity to absorb eccentric loads was the arc of motion that represented eccentric contractions at the longest muscle length.

Keywords: exercise therapy, muscle strength, isokinetic dynamometer, sarcomerogenesis

The innate function of skeletal muscle is determined by its cell structure (fiber morphology) and how these cells are arranged (muscle architecture). Fortunately, the plasticity of skeletal muscle permits modifications to morphology and architecture when the fibers are subjected to altered biochemical and mechanical stress during exercise-induced loss of homeostasis.1 The subsequent architectural and structural adaptations attenuate these stresses, thereby modifying fiber and muscle function.2,3 For example, chronic-training-induced fiber-type transitions reduce the biochemical stresses produced by cell metabolism,4 whereas fiber-specific hypertrophy attenuates mechanical stresses.5 Arguably, the most clinically recognizable exercise-induced adaptation in skeletal muscle is hypertrophy, or the cumulative effect of increased muscle-fiber size. At the cellular level, muscle fibers can increase their size through mechanisms of myofibrillogenesis and/or sarcomerogenesis.

Myofibrillogenesis is muscle-fiber hypertrophy in the axial direction and increases the cross-sectional area of the fiber, because sarcomeres are added in parallel. Sarcomeres are force-producing elements, and the forces produced by them are additive in parallel. Therefore, increases in muscle cross-sectional area are a good predictor of peak isometric force,6 which is easily tested in the clinic and used as an objective criterion for return to play after injury.7 Muscle-fiber activation and the production of internal forces are essential stimuli to optimize exercise-induced myofibrillogenesis.8-10 However, if a muscle fiber is also subjected to an external load that results in positive strain or stretch of the fiber, hypertrophy will also occur in the longitudinal direction, increasing fiber length due to sarcomerogenesis.11,12

Sarcomerogenesis, or the addition of sarcomeres in series within a muscle fiber, has been studied extensively with in vitro, 13,14 in situ, 15,16 and in vivo 12,17-23 models. Although immobilizing a muscle in a lengthened position results in an increase in serial sarcomere number, 21,22,24,25 this addition is reversed if the stimulus is removed. Subsequently, the lack of tension sensing in the sarcomeres returns the serial sarcomere number to prestretch numbers within weeks and demonstrates the plasticity of sarcomere number and its relationship to joint angle and muscle tension.

Serial sarcomere number within individual fibers demonstrates a high correlation to joint angle26 and signifies a mechanical advantage produced through the gain of sarcomeres in series. Increased serial sarcomere number would be of benefit in a static contraction, improving the muscle function by shifting the force–length relationship to the right, producing peak isometric force at a longer muscle length or greater torque at a greater joint angle. During a dynamic contraction, this would reduce sarcomere strain for a given joint angle during eccentric contractions.3,12 Further adaptations to function would be manifested as increases in contractile velocity,27 muscle power,28 and extensibility.11 Clinically, this functional adaptation in serial sarcomere number may also prevent injury when the muscle consistently works eccentrically at longer lengths.11,22,29 These dynamic adaptations have been demonstrated in animal models using freely walking rats20,23,30 and controlled eccentric-exercise protocols in rabbits.12,15,31

The adaptation of sarcomere addition in series after chronic eccentric exercise supports a previously proposed mechanism whereby sarcomere length is optimized for the muscle length at which force exerted on the tendon is the greatest.32 Therefore this adaptation in serial sarcomere number has clinical implications as a potential injury-preventing mechanism, due to the shift of the force–length (torque–joint angle) relationship to produce greater force (torque) at longer muscle lengths.11 Although sarcomeres have not been counted in human subjects after eccentric-exercise training, recent studies have demonstrated indirect evidence of sarcomerogenesis in human subjects, including adaptations in muscle function33,34 and morphology35,36 focused primarily on thigh35-39 and brachial34,35 muscles. To date, there are no data available as to the effectiveness of an eccentrically biased training protocol on the function of the external rotators of the glenohumeral joint. Because these muscles are integral to the deceleration of the humerus during throwing,40 training protocols that produce a rightward shift of the torque–joint angle relationship may prove beneficial. Therefore, the purpose of this study was examine the effectiveness of a 6-week home-based eccentric exercise program to enhance isometric and eccentric external-rotation (ER) strength in lengthened positions.

Methods

Setting and Participants

Ten participants volunteered for this study from a sample of convenience at a university (age 30 ± 10 y, height 164 ± 10 cm, mass 79 ± 18 kg). Subjects were excluded from participation if they reported a history of shoulder or neck pathology, previous shoulder or neck surgery, or shoulder or neck pain within the previous 6 months. All healthy subjects not excluded and willing to participate read and signed a University of Kentucky institutional review board–approved informed consent before participation in the study.

Subjects filled out the Penn Shoulder Score before testing to evaluate level of shoulder function before participating. The Penn Shoulder Score ranges from 0 to 100, with 100 representing highest level of function. The score has been found to be a reliable and valid measure of shoulder function.41 The Penn Shoulder Score averaged 97 with a range of 85 to 100, indicating that current participants demonstrated near-normal function at the onset of the study. All testing was completed at the musculoskeletal laboratory at the University of Kentucky, with a single unblinded investigator performing all testing.

Study Design

This prospective case-series investigation was designed to investigate the effectiveness of home-based eccentric exercises for the posterior shoulder to improve ER strength and improve ability of the posterior shoulder to absorb dynamic internal-rotation (iR) forces. Three days of familiarization with 1 week of rest between testing episodes were used to establish baseline values and evaluate reliability of testing procedures. A 6-week exercise intervention incorporating 2 exercises was carried out by all participants. The same testing procedures were repeated after the program to evaluate changes from the intervention. Participants were asked to not start a new exercise program during the study; however, they could continue to perform their normal exercise and activities of daily living during the study. The independent variable is time identified as preexercise and postexercise tests. There are 2 dependent variables (isometric torque at 5 angles and dynamic eccentric shoulder ER angular impulse) that were measured at every time point.

Isometric and Isokinetic Testing Procedures

Before shoulder testing all participants completed 3 shoulder stretches (cross-body, sleeper stretch, and corner-wall shoulder stretch) for 2 sets of 30 seconds each. They then warmed up with 2 active range-of-motion exercises with no load, consisting of side-lying ER and side-lying horizontal shoulder abduction and adduction. Each exercise was performed for approximately 1 minute. The same warm-up occurred before each day of testing.

Next, shoulder-strength testing was performed using an isokinetic dynamometer (Cybex Norm, Ronkonkoma, NY) as previously reported.42 Participants were seated with their dominant shoulder in 60° of abduction and 30° of horizontal adduction. This was defined as the scapular plane in the Cybex Norm user manual. Both positions were confirmed using a handheld goniometer on all subjects. isometric testing was always performed first; isometric shoulder ER strength was determined from the average of 2 trials taken at 5 test positions (45° iR, 30° IR, 15° IR, 0°, and 15° ER). The order of the test position was randomly assigned using a random-number generator with Microsoft Excel on each testing day to minimize length-change biases related to the length-dependent and time-dependent properties of muscle.43,44

In each test position, subjects performed 1 sub-maximal practice repetition for 3 seconds, rested for 20 seconds, and then performed 2 maximal repetitions for 3 seconds with a 60-second rest between efforts as previously established.33 Standardized verbal encouragement was given during isometric strength testing for maximal repetitions to attempt to maximize the subject’s effort and strength potential.45 Peak torque was recorded for both isometric contractions at every angle and averaged to represent angle-specific torque. The excellent reliability of these testing procedures between days (ICC ≥ .85) has been previously reported.42

After the collection of isometric-torque data, dynamic eccentric shoulder-ER torque data were collected, while maintaining the shoulder in the same test position and through a 100° arc of motion from 50° of ER to 50° of IR. The continuous-passive-motion mode was used with Humac software (Computer Sports Medicine Inc, Stoughton, MA) on the Cybex Norm with an IR velocity set at 60°/s. From the start position of 50° ER, the subject was instructed to maximally contract into ER to initiate IR. The subject was instructed to maximally resist IR through the entire range of motion to evaluate dynamic eccentric ER torque production. The subject was asked to relax his or her arm as the isokinetic dynamometer passively returned the arm into the ER starting position at 15°/s. This process removed all concentric activity during testing. Participants were given 3 minutes to rest after the familiarization phase and then performed 6 maximal efforts in a row, with 7 seconds of recovery during the passive return to 50° of ER between trials. Standardized verbal encouragement was given during eccentric testing. The middle 4 trials were averaged together to determine angular impulse, later used for data reduction and statistical analyses. A total of 3 baseline testing sessions, 1 week apart, were collected before initiating the home eccentric-exercise program to reduce the effect of motor learning during a novel task.46,47 Postintervention testing occurred at 6 weeks after the start of the home exercise program and consisted of the same procedures described herein. The reliability of the dynamic eccentric shoulder-ER strength as determined by angular impulse is excellent (ICC ≥ .97) as previously reported.42

Exercise Procedures

The home-based exercise program consisted of 2 eccentrically biased exercises: side-lying horizontal adduction and side-lying ER. This exercise protocol is modified from Blackburn et al48 and has been shown to be an excellent position to activate the posterior shoulder musculature. Participants were all given the same exercise instructions for performing 2 sets of each exercise with 15 repetitions per set, 4 times a week. To focus on the eccentric component of the exercise and minimize the concentric portion, specific instructions were provided and initially performed with investigator supervision. To bias the exercises for eccentric contractions, subjects removed the weight from their own hand at the end of the eccentric-contraction phase and rotated to a supine position to allow gravity to externally rotate the humerus back to the starting position to minimize concentric activity. They then placed the weight back in the hand of the experimental side and rotated back to side-lying for the next repetition. All participants had to demonstrate proper form with both eccentric-exercise maneuvers. Form was deemed proper when subjects could effectively eliminate concentric contractions from both exercise regimens and perform eccentric contractions through the full range of motion at the correct speed as per the instructions (see the Appendix). To support the clinical instruction, detailed written methods and pictures were given to participants to take home (Appendix). All eccentric exercises were performed at a slow pace of 8 seconds for lowering the weight to emphasize the eccentric load to the posterior rotator cuff. Participants returned weekly to progress their resistance loads and ensure proper exercise form.

Starting resistance for the eccentric exercise was determined from the highest dynamic eccentric shoulder-ER average peak torque generated on 1 of the 3 baseline testing days. Average peak torque (Nm) was divided by the length of the subject’s forearm (m) to estimate the force (N), which was then converted to pounds and multiplied by 0.2 to determine the weight used for the first week of training. Subjects were progressed on a weekly basis using a linear progression of increasing loads while repetitions were held constant. After the first week, the initial load was increased 20% and then subsequently increased by 25% weekly for the next 5 training weeks. Subjects were given a log to track their weight, sets, and repetitions that was returned at the end of the study. In addition, a modified Borg perceived-exertion scale was used to record level of difficulty when performing exercise. The scale ranged from 0 to 10, with 10 representing maximal effort during an exercise. This allowed the researchers to monitor exercise progress so that resistance loads could match perceived exertion during exercise.

Data Reduction and Statistical Analysis

The 2 isometric trials for each day of testing were averaged together to represent ER torque at each shoulder angle. The postexercise test data were subtracted from the preexercise test data for each subject to determine the change score. The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality revealed that the isometric data were not normally distributed. Nonparametric analysis was carried out using a Friedman test to determine if change scores differed across the 5 positions (IR 45°, IR 30°, IR 15°, neutral, ER 15°) for isometric data, with alpha level set at P ≤ .05. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare individual differences between positions if appropriate, with alpha level corrected for 10 comparisons (P ≤ .005).

Raw data from each dynamic eccentric testing day for each subject were extracted from the Cybex. The raw data provided time, speed, angle, and torque at a rate of 100 Hz. These data were imported into an Excel (Microsoft, Redwood, CA) template to calculate angular impulse. Angular impulse was calculated using the trapezoidal equation for area {∑(1/2[θ at point A + torque at point B] × 0.01)} for the entire trial. The 4 middle efforts of the 6 trials were averaged together. The average total angular impulse was further divided into 4 equal 25° arcs of motion to clearly represent work production through the range of motion. The postexercise test data were subtracted from the preexercise test data for each subject to determine the change score. The Shapiro-Wilk test for normality revealed that the dynamic eccentric data were not normally distributed. Nonparametric analysis was carried out using a Friedman test to determine if change scores differed across the 4 arcs (ER 50–25°, ER 25–0°, IR 0–25°, IR 25–50°) for dynamic eccentric data, with alpha level set at P ≤ .05. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare individual differences between arcs if appropriate, with alpha level corrected for 6 comparisons (P ≤ .0083).

Results

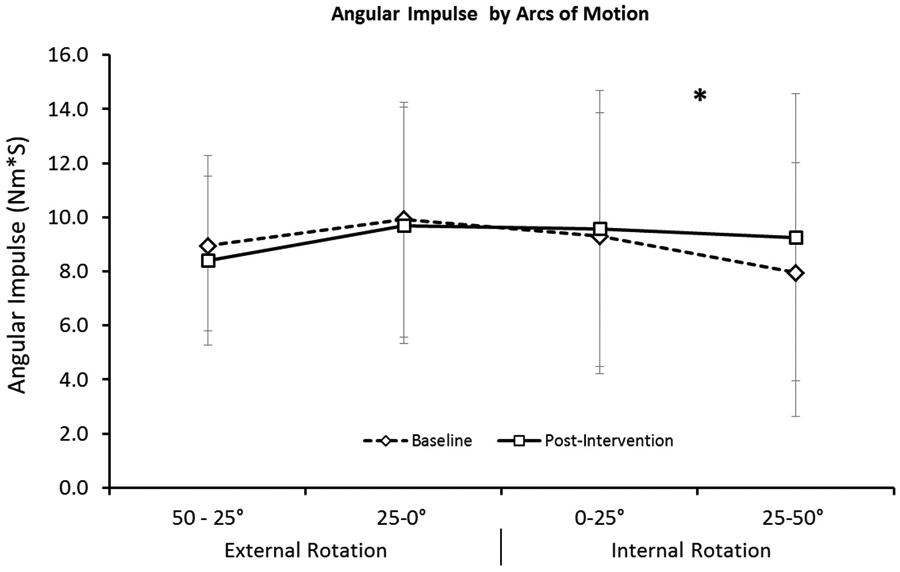

The isometric data analysis is presented using median values and interquartile ranges as nonparametric analysis was performed, which revealed no significant differences between the 5 positions (P = .56, Table 1). The dynamic eccentric data analysis revealed a significant difference between arcs (P = .02, Figure 1). Correcting for multiple comparisons between the 4 arcs, there was only 1 pairwise comparison with reach significant difference. The arc of IR 25–50° percentage-change score was found to be significantly greater than the arc of IR 0–25° (P = .007, Table 2). After eccentric training the only arc of motion that had a positive improvement in the capacity to absorb eccentric loads was the arc of motion that represented eccentric contractions at the longest muscle length.

Table 1.

Isometric Change Scores

| Median change score |

Interquartile range | |

|---|---|---|

| ER 15° | 4.79 | −5.6% to 11.4% |

| Neutral 0° | 1.18 | −5.1% to 21.6% |

| IR 15° | 7.75 | −10.4% to 26.5% |

| IR 30° | −1.91 | −2.9% to 17.8% |

| IR 45° | 1.64 | −1.2% to 17.4% |

Note: ER, external rotation; IR, internal rotation. – indicates that the isometric strength decreased from baseline.

Figure 1.

Mean eccentric angular impulse for the posterior shoulder muscles on day 1 (open diamonds) and after an eccentrically biased training program (open squares) for 4 arcs of motion. Eccentric contractions began with the posterior shoulder muscles at their shortest length (50° of external rotation), and the muscles were lengthened during contraction to their longest lengths (50° internal rotation). After eccentrically biased training, the area under the eccentric torque–angle curve (angular impulse) was significantly greater (*) for the arc of motion that represented the longest muscle lengths (25–50° internal rotation).

Table 2.

Dynamic Eccentric Percentage-Change Scores Compared With the Longest Position of the IR Arc 25–50°

| Short |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER 50–25° | ER 25–0° | IR 0–25° | Long, IR 25–50° | |

| Median change scores | −3.49 | −3.0 | +0.4 | +9.5 |

| Interquartile range | −21.8 to 12.79 | −14.1 to 7.9 | −8.9 to 12.9 | 2.2–31.0 |

| Significance compared with long IR 25–50° | P = .059 | P = .017 | P = .007* | |

Note: ER, external rotation; IR, internal rotation. – indicates that the angular impulse decreased from baseline.

Significantly different from IR 25–50°.

Discussion

Although Fridén et al, in 1984,49 were the first to propose sarcomerogenesis as a beneficial, functional adaptation to eccentric exercise, direct mechanistic evidence of increased serial sarcomere number after chronic training with eccentrically biased contractions has only been demonstrated in animal models to date. By training rats to walk on a treadmill, Lynn and Morgan30 were the first to show an exercise-specific adaptation in serial sarcomere number in the vastus intermedius muscle. Although fiber strains were not directly measured, it was reasonably assumed that the quadriceps operated eccentrically during daily bouts of downhill walking, and eccentric training was associated with a significant increase in fiber length and serial sarcomere number and, therefore, greater force at longer lengths.20,30 By directly measuring fiber dynamics, Butterfield et al23 associated positive active fiber strains to subsequent serial sarcomere number increases of ~10% in the vastus intermedius after 10 days of eccentrically biased exercise. Subsequently it was shown that higher positive fiber strains during eccentric exercise resulted in greater serial sarcomere number adaptations, and this could be accomplished by exercising the muscle through excursions involving long muscle lengths near or at terminal ranges of motion.12,50

Serial sarcomere number measurements, and therefore direct measurements of sarcomerogenesis, are impractical if not impossible in human subjects. Therefore, architectural and functional measures previously associated with sarcomerogenesis in animal models are used as indirect measures of a beneficial adaptation to eccentric exercise in humans, including a rightward shift in the muscle’s torque–joint angle relationship,34,37 adaptations in muscle architecture such as longer muscle fibers35,36,51 and/or increased fiber pennation angles.52

In this study, by training the posterior shoulder muscles eccentrically, we were interested to see if changes in both isometric and dynamic eccentric strength of the shoulder external rotators would increase the ability of the posterior shoulder musculature to absorb eccentric loads at the end range of the eccentric motion. We found that our eccentrically biased training program for the posterior shoulder muscles did not have an effect on their isometric torque–joint angle relationship. Although a rightward shift after repeated bouts of eccentric exercise training has been associated with serial sarcomerogenesis in human muscle,37 there is evidence that sarcomere number adaptations can also occur without a significant shift in this relationship. Chen et al34 found a direct association between training load and torque–angle shift after eccentric-exercise training in human subjects. In their study, only subjects who performed eccentric exercises at 100% of maximal voluntary contraction exhibited a rightward shift of the torque–angle curve on the biceps brachii, despite additional groups that trained submaximally exhibiting other beneficial training adaptations such as the repeated-bout effect, or resistance to subsequent eccentric-exercise-induced injury.34

It is therefore possible that our training program was not long enough or the resistive load may not have been adequate to facilitate a measureable muscle adaption in isometric torque. This is supported, in part, by the aforementioned eccentric-training studies in rabbits, whereby higher evoked forces during 8 weeks of eccentric training resulted in greater rightward shift of the torque–angle curves.12,50 In addition, the lack of a shift in the isometric torque–angle relationship may be associated with the methodology in calculating the angle of isometric peak-torque production.53 By necessity, the isometric torque measures in our study are discreet data points, measured at every 15° of glenohumeral rotation. Therefore, it is possible that changes in isometric peak torque may have occurred between 2 discrete measurements. Finally, the torque–angle relationship is a measurement that is sensitive to several factors and easily altered by factors such as reduced effort, fatigue, alterations in series compliance, and/or changes in muscle/tendon stiffness.53

Therefore, we also measured the dynamic eccentric torque–angle relationship as a more robust indicator of the muscle’s capacity for energy absorption.54,55 The mechanism of force production during an eccentric contraction differs significantly from the traditional mechanism of cross-bridge-produced force during isometric and concentric contractions.56-60 Therefore, forces produced eccentrically are independent of fiber type,61 and although fiber transitions can modify the muscle’s contractile velocity, power, and rate of force development during concentric contractions, their influence on force is essentially eliminated during isometric contractions, when the velocity is zero.62 However, exercise-induced alterations in the elastic elements of the muscle and/or tendon can modify force production.63,64 Elastic energy storage is an essential component of the shoulder musculature for throwing activities,65 and stiffening of the parallel elastic component of the muscle by itself or in conjunction with sarcomerogenesis could explain our results. The increase in angular impulse at the longest muscle length is a significant adaptation to eccentrically biased exercise. It can be produced by increasing the length of the muscle fibers,20 is indicative of serial sarcomere number increases,11,12 and increases the amount of energy that the external rotators can absorb while actively lengthening3,66 and reduces the potential for eccentric-exercise-induced strain damage and injury.11,20,29,33,34,36,37,39,51,52,54

It is well documented that the posterior shoulder needs to act eccentrically to decelerate the arm during the termination of a baseball pitch, tennis serve, or similar movement.67-70 We believe that the ability to effectively activate the posterior shoulder musculature eccentrically through the full range of motion is critical for avoiding injuries in the shoulder, specifically for overhead-throwing athletes. Although our subjects performed the testing and exercise procedures with the shoulder in a different position than a throwing motion, we propose that the functional adaptations measured in this study are translatable. The posterior shoulder musculature must decelerate the shoulder during both the deceleration phase and the follow-through phase of pitching, as the loads are dissipated. Fleisig et al69 calculated a significant IR torque at the shoulder that was still evident at terminal IR. At the time of ball release, Werner et al71,72 calculated high distraction forces that were dissipated over the following 200 milliseconds, as the shoulder continues to internally rotate to approximately 0° of glenohumeral rotation.73

Limitations

We used 2 different positions for exercising and testing the muscles of the posterior shoulder. It is reasonable to expect exercise-induced adaptations in skeletal muscle to be specific to function, that is, contraction type and muscle length. Therefore, it is possible that the exact magnitude of the adaptations was not measured due to the different position of testing. However, we did find an improved eccentric impulse at long muscle lengths for the posterior shoulder musculature in a disparate shoulder position (and muscle position), which indicates the robustness of the adaptation at the tissue level. Future studies will use a laboratory setting to test and measure in identical positions.

It is possible that adaptations in motor-unit recruitment occurred in our subjects over the course of the study. However, the lack of a significant training effect in the isometric torque data in conjunction with the systematic improvement in eccentric torque production in only the terminal arc of motion makes this less likely. In addition, muscle morphological and functional adaptations to eccentric loading are evident earlier compared with adaptations from isometric and concentric training, which supports fiber adaptation after an eccentrically biased 4-week training program.74 In future studies measuring eccentric-exercise-induced adaptations in our laboratory, we will include longer exercise durations and higher intensities, incorporate methods such as EMG to assess muscle activation, and measure rate of torque development and muscle stiffness to further separate viable mechanisms underlying the functional adaptations in skeletal muscle.

Conclusion

In this pilot study, we have shown for the first time that an eccentrically biased home exercise program can improve the energy-absorption capacity of the posterior shoulder muscles by increasing the eccentric torque production at terminal IR. The exercises performed in this study can be translated easily for clinical use by overhead athletes. While these exercises do not approach the velocity seen in overhead sports, they could be good options for training program for overhead athletes or during rehabilitation to facilitate eccentric strengthening of the posterior shoulder musculature. The 2 posterior-shoulder eccentric exercises used during this 6-week intervention appear to support the concept of specific adaptation to imposed-demand principle and increase the ability to absorb forces with the muscle in a lengthened position.

Appendix

Side-Lying Eccentric Horizontal Adduction

Lie on your back near the edge of a firm surface, preferably the floor or a firm mattress (Appendix Figure 1).

Extend the nonexercising arm straight up in the air while holding the weight (Appendix Figure 2).

Extend your exercising arm straight up in the air, transfer the weight to the opposite (exercising) hand, and drop your nonexercising hand to your side (Appendix Figures 3–5).

Roll onto your nonexercising side keeping the weight still extended straight up in the air (Appendix Figure 6).

Now, using an 8-count, slowly lower the weight, keeping your thumb pointing toward the ceiling, your arm straight, and your arm in line with your mouth (Appendix Figures 7 and 8).

Let the weight lower as far as the surface will permit, hanging off if possible (Appendix Figure 8).

Once the weight has been fully lowered, roll onto your back (Appendix Figure 9) and assume the starting position (Appendix Figure 1). Repeat the steps for 2 sets of 15 repetitions.

Side-Lying Eccentric External Rotation

Lie on your side on a firm surface, with a rolled-up towel or bolster placed under your arm and the weight held by your nonexercising arm as shown (Appendix Figure 10).

Roll onto your back and bring the weight up to your exercising arm, making sure to keep the towel under your arm (Appendix Figure 11).

Roll back onto your side; your arm should rotate up toward the ceiling (Appendix Figure 12).

Slowly lower the weight toward the surface, keeping the elbow bent at a right angle (Appendix Figures 13–15).

Once you have gone through your available range of motion, drop the weight to the surface (Appendix Figure 16).

With the nonexercising arm, pick up the weight (Appendix Figure 17) and position your arm back in the starting position to repeat the exercise for the given number of repetitions (Appendix Figures 18, 10).

Contributor Information

Timothy L. Uhl, Div of Athletic Training, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY.

Thomas Rice, Dept of Athletics, Louisiana Tech University, Rushton, LA..

Brianna Papotto, Div of Athletic Training, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY..

Timothy A. Butterfield, Div of Athletic Training, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY.

References

- 1.Vanrenterghem J, Nedergaard NJ, Robinson MA, Drust B. Training load monitoring in team sports: a novel framework separating physiological and biomechanical load-adaptation pathways [published online ahead of print March 10, 2017]. Sports Med. PubMed doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0714-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarkson PM, Nosaka K, Braun B. Muscle function after exercise-induced muscle damage and rapid adaptation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24(5):512–520. PubMed doi: 10.1249/00005768-199205000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butterfield TA. Eccentric exercise in vivo: strain-induced muscle damage and adaptation in a stable system. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2010;38(2):51–60. PubMed doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181d496eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simoneau JA, Lortie G, Boulay MR, Marcotte M, Thibault MC, Bouchard C. Human skeletal muscle fiber type alteration with high-intensity intermittent training. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1985;54(3):250–253. PubMed doi: 10.1007/BF00426141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fry AC. The role of resistance exercise intensity on muscle fibre adaptations. Sports Med. 2004;34(10):663–679. PubMed doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434100-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blazevich AJ, Gill ND, Zhou S. Intra- and intermuscular variation in human quadriceps femoris architecture assessed in vivo. J Anat. 2006;209(3):289–310. PubMed doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00619.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen W, Taheri P, Forkel P, Zantop T. Return to play following ACL reconstruction: a systematic review about strength deficits. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(10):1417–1428. PubMed doi: 10.1007/s00402-014-1992-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fluck M, Waxham MN, Hamilton MT, Booth FW. Skeletal muscle Ca2+-independent kinase activity increases during either hypertrophy or running. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2000;88(1):352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nader GA, McLoughlin TJ, Esser KA. mTOR function in skeletal muscle hypertrophy: increased ribosomal RNA via cell cycle regulators. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289(6):C1457–C1465. PubMed doi: 10.1152/ajp-cell.00165.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esser K Regulation of mTOR signaling in skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2008;8(4):338–339. PubMed [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Proske U, Morgan DL. Muscle damage from eccentric exercise: mechanism, mechanical signs, adaptation and clinical applications. J Physiol. 2001;537(Pt 2):333–345. PubMed doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00333.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Butterfield TA, Herzog W. The magnitude of muscle strain does not influence serial sarcomere number adaptations following eccentric exercise. Pflugers Arch. 2006;451(5):688–700. PubMed doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1503-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Deyne PG. Formation of sarcomeres in developing myotubes: role of mechanical stretch and contractile activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279(6):C1801–C1811. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann WW. Mechanisms of muscular hypertrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1980;45(2-3):205–216. PubMed doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(80)90166-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koh TJ, Herzog W. Eccentric training does not increase sarcomere number in rabbit dorsiflexor muscles. J Biomech. 1998;31(5):499–501. PubMed doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(98)00032-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh TJ, Herzog W. Excursion is important in regulating sarcomere number in the growing rabbit tibialis anterior. J Physiol. 1998;508(Pt 1):267–280. PubMed doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.267br.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burkholder TJ. Age does not influence muscle fiber length adaptation to increased excursion. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2001;91(6):2466–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burkholder TJ, Lieber RL. Sarcomere number adaptation after retinaculum transection in adult mice. J Exp Biol. 1998;201(Pt 3):309–316. PubMed [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams PE, Goldspink G. Longitudinal growth of striated muscle fibres. J Cell Sci. 1971;9(3):751–767. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynn R, Talbot JA, Morgan DL. Differences in rat skeletal muscles after incline and decline running. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1998;85(1):98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabary JC, Tabary C, Tardieu C, Tardieu G, Goldspink G. Physiological and structural changes in the cat’s soleus muscle due to immobilization at different lengths by plaster casts. J Physiol. 1972;224(1):231–244. PubMed doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabary JC, Tardieu C, Tabary C, Lombard M, Gagnard L, Tardieu G. Neural regulation and adaptation of the number of sarcomeres of muscle fiber to the length imposed on it [in French]. J Physiol (Paris). 1972;65(Suppl 1):168A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butterfield TA, Leonard TR, Herzog W. Differential serial sarcomere number adaptations in knee extensor muscles of rats is contraction type dependent. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005;99(4):1352–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tardieu C, Tabary JC, Gagnard L, Lombard M, Tabary C, Tardieu G. Change in the number of sarcomeres and in isometric tetanic tension after immobilization of cat anterior tibialis muscle at different lengths [in French]. J Physiol (Paris). 1974;68(2):205–218. PubMed [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams PE, Goldspink G. The effect of immobilization on the longitudinal growth of striated muscle fibres. J Anat. 1973;116(Pt 1):45–55. PubMed [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabary JC, Tardieu C, Tardieu G, Tabary C, Gagnard L. Functional adaptation of sarcomere number of normal cat muscle. J Physiol (Paris). 1976;72(3):277–291. PubMed [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woledge RC, Curtin NA, Homsher E. Energetic aspects of muscle contraction. Monogr Physiol Soc. 1985;41:1–357. PubMed [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldspink G Malleability of the motor system: a comparative approach. J Exp Biol. 1985;115:375–391. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fridén J Changes in human skeletal muscle induced by long-term eccentric exercise. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;236(2):365–372. PubMed doi: 10.1007/BF00214240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynn R, Morgan DL. Decline running produces more sarcomeres in rat vastus intermedius muscle fibers than does incline running. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1994;77(3):1439–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butterfield TA, Best TM. Stretch-activated ion channel blockade attenuates adaptations to eccentric exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(2):351–356. PubMed doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318187cffa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herring SW, Grimm AF, Grimm BR. Regulation of sarcomere number in skeletal muscle: a comparison of hypotheses. Muscle Nerve. 1984;7(2):161–173. PubMed doi: 10.1002/mus.880070213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Philippou A, Bogdanis GC, Nevill AM, Maridaki M. Changes in the angle-force curve of human elbow flexors following eccentric and isometric exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;93(1-2):237–244. PubMed doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1209-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen TC, Nosaka K, Sacco P. Intensity of eccentric exercise, shift of optimum angle, and the magnitude of repeated-bout effect. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007;102(3):992–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lau WY, Blazevich AJ, Newton MJ, Wu SS, Nosaka K. Reduced muscle lengthening during eccentric contractions as a mechanism underpinning the repeated-bout effect. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2015;308(10):R879–R886. PubMed doi: 10.1152/ajp-regu.00338.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potier TG, Alexander CM, Seynnes OR. Effects of eccentric strength training on biceps femoris muscle architecture and knee joint range of movement. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;105(6):939–944. PubMed doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0980-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brockett CL, Morgan DL, Proske U. Human hamstring muscles adapt to eccentric exercise by changing optimum length. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(5):783–790. PubMed doi: 10.1097/00005768-200105000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brughelli M, Nosaka K, Cronin J. Application of eccentric exercise on an Australian Rules football player with recurrent hamstring injuries. Phys Ther Sport. 2009;10(2):75–80. PubMed doi: 10.1016/j.ptsp.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McHugh MP, Tetro DT. Changes in the relationship between joint angle and torque production associated with the repeated bout effect. J Sports Sci. 2003;21(11):927–932. PubMed doi: 10.1080/0264041031000140400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kibler WB, Kuhn JE, Wilk K, et al. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology-10-year update. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(1):141–161.e126. PubMed doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leggin BG, Michener LA, Shaffer MA, Brenneman SK, Iannotti JP, Williams GR Jr. The Penn Shoulder Score: reliability and validity. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36(3):138–151. PubMed doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.36.3.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papotto BM, Rice T, Malone T, Butterfield T, Uhl TL. Reliability of isometric and eccentric isokinetic shoulder external rotation. J Sport Rehabil. 2016;Technical Report; 21. 10.1123/jsr.2015-0046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maganaris CN, Baltzopoulos V, Sargeant AJ. Repeated contractions alter the geometry of human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2002;93(6):2089–2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rassier DE. The effects of length on fatigue and twitch potentiation in human skeletal muscle. Clin Physiol. 2000;20(6):474–482. PubMed doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.2000.00283.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McNair PJ. Verbal encouragement of voluntary muscle action: reply to commentary by Roger Eston. Br J Sports Med. 1996;30(4):365. PubMed doi: 10.1136/bjsm.30.4.365-a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lagassé PP, Katch FI, Katch VL, Roy MA. Reliability and validity of the Omnitron hydraulic resistance exercise and testing device. Int J Sports Med. 1989;10(6):455–459. PubMed doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1024943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayer F, Horstmann T, Kranenberg U, Rocker K, Dickhuth HH. Reproducibility of isokinetic peak torque and angle at peak torque in the shoulder joint. Int J Sports Med. 1994;15(Suppl 1):S26–S31. PubMed doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blackburn TA, MacLeod WD, White B, Wofford L. EMG analysis of posterior rotator cuff exercises. J Athl Train. 1990;25:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fridén J, Seger J, Sjostrom M, Ekblom B. Adaptive response in human skeletal muscle subjected to prolonged eccentric training. Int J Sports Med. 1983;4(3):177–183. PubMed doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1026031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Butterfield TA, Herzog W. Effect of altering starting length and activation timing of muscle on fiber strain and muscle damage. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2006;100(5):1489–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baroni BM, Geremia JM, Rodrigues R, De Azevedo Franke R, Karamanidis K, Vaz MA. Muscle architecture adaptations to knee extensor eccentric training: rectus femoris vs. vastus lateralis. Muscle Nerve. 2013;48(4):498–506. PubMed doi: 10.1002/mus.23785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blazevich AJ, Cannavan D, Coleman DR, Horne S. Influence of concentric and eccentric resistance training on architectural adaptation in human quadriceps muscles. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007;103(5):1565–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Butterfield TA, Herzog W. Is the force-length relationship a useful indicator of contractile element damage following eccentric exercise? J Biomech. 2005;38(9):1932–1937. PubMed doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lindstedt SL, LaStayo PC, Reich TE. When active muscles lengthen: properties and consequences of eccentric contractions. News Physiol Sci. 2001;16:256–261. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaminski TW, Wabbersen CV, Murphy RM. Concentric versus enhanced eccentric hamstring strength training: clinical implications. J Athl Train. 1998;33(3):216–221. PubMed [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herzog W The role of titin in eccentric muscle contraction. J Exp Biol. 2014;217(Pt 16):2825–2833. PubMed doi: 10.1242/jeb.099127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herzog W Mechanisms of enhanced force production in lengthening (eccentric) muscle contractions. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014;116(11):1407–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herzog W, Leonard T, Joumaa V, DuVall M, Panchangam A. The three filament model of skeletal muscle stability and force production. Mol Cell Biomech. 2012;9(3):175–191. PubMed [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoppeler H, Herzog W. Eccentric exercise: many questions unanswered. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014;116(11):1405–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schappacher-Tilp G, Leonard T, Desch G, Herzog W. A novel three-filament model of force generation in eccentric contraction of skeletal muscles. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0117634. PubMed doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hortobágyi T, Zheng D, Weidner M, Lambert NJ, Westbrook S, Houmard JA. The influence of aging on muscle strength and muscle fiber characteristics with special reference to eccentric strength. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(6):B399–B406. PubMed doi: 10.1093/gerona/50A.6.B399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Komi PV. Training of muscle strength and power: interaction of neuromotoric, hypertrophic, and mechanical factors. Int J Sports Med. 1986;7(Suppl 1):10–15. PubMed doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1025796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Magnusson SP, Narici MV, Maganaris CN, Kjaer M. Human tendon behaviour and adaptation, in vivo. J Physiol. 2008;586(1):71–81. PubMed doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Urlando A, Hawkins D. Achilles tendon adaptation during strength training in young adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(7):1147–1152. PubMed doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31805371d1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roach NT, Venkadesan M, Rainbow MJ, Lieberman DE. Elastic energy storage in the shoulder and the evolution of high-speed throwing in Homo. Nature. 2013;498(7455):483–486. PubMed doi: 10.1038/nature12267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garrett WE Jr, Safran MR, Seaber AV, Glisson RR, Ribbeck BM. Biomechanical comparison of stimulated and nonstimulated skeletal muscle pulled to failure. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15(5):448–454. PubMed doi: 10.1177/036354658701500504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ellenbecker TS, Davies GJ, Rowinski MJ. Concentric versus eccentric isokinetic strengthening of the rotator cuff: objective data versus functional test. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(1):64–69. PubMed doi: 10.1177/036354658801600112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Escamilla RF, Andrews JR. Shoulder muscle recruitment patterns and related biomechanics during upper extremity sports. Sports Med. 2009;39(7):569–590. PubMed doi: 10.2165/00007256-200939070-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(2):233–239. PubMed doi: 10.1177/036354659502300218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jobe FW, Tibone JE, Perry J, Moynes D. An EMG analysis of the shoulder in throwing and pitching: a preliminary report. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11(1):3–5. PubMed doi: 10.1177/036354658301100102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Werner SL, Guido JA, Delude NA, Stewart GW, Greenfield JH, Meister K. Throwing arm dominance in collegiate baseball pitching: a biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(8):1606–1610. PubMed doi: 10.1177/0363546510365511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Werner SL, Suri M, Guido JA Jr, Meister K, Jones DG. Relationships between ball velocity and throwing mechanics in collegiate baseball pitchers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):905–908. PubMed doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dillman CJ, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR. Biomechanics of pitching with emphasis upon shoulder kinematics. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1993;18(2):402–408. PubMed doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.18.2.402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Douglas J, Pearson S, Ross A, McGuigan M. Eccentric exercise: physiological characteristics and acute responses. Sports Med. 2017;47(4):663–675. PubMed [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]