Abstract

Peer specialists, or individuals with lived experience of mental health conditions who support the mental health recovery of others, often work side-by-side with traditional providers (non-peers) in the delivery of treatment groups. The present study aimed to examine group participant and peer provider experiences with peer and non-peer group co-facilitation. Data from a randomized controlled trial of Living Well, a peer and non-peer co-facilitated intervention for medical illness management for adults with serious mental illness, were utilized. A subset of Living Well participants (n = 16) and all peer facilitators (n = 3) completed qualitative interviews. Transcripts were coded and analyzed using a general inductive approach and thematic analysis. The complementary perspectives of the facilitators, teamwork between them, skillful group pacing, and peer facilitator self-disclosure contributed to a warm, respectful, and interactive group atmosphere, which created an environment conducive to social learning. Guidelines for successful co-facilitation emerging from this work are described.

Keywords: Seriousmental illness, Peer support, Group co-facilitation, Group process

Peer specialists are individuals with a lived experience of a mental health condition who support the recovery of other individuals with mental health conditions [1]. Peers can effectively deliver individual and group-based psychosocial interventions, and facilitate treatment engagement, self-efficacy, and community integration [2, 3]. To address high rates of chronic medical conditions among adults with mental illness, peer specialists can also successfully promote medical illness self-management, weight management, and smoking cessation [4–10].

Peer specialists are increasingly being employed as members of interdisciplinary care teams in mental health care systems, with peer specialists and traditional providers (non-peers) working side-by-side in the delivery of mental health services [11]. When working as employees in health care systems, peer specialists share their lived experience of recovery, serve as role models, instill hope, and build strong rapport with mental health service users. A significant barrier to the successful integration of peer specialists into mental health care settings is a lack of understanding on the part of non-peer providers regarding this role [12].

Treatment groups are a common mode of service delivery in mental health settings, which rely on group cohesion and social learning to deliver information, teach skills, and provide support. In a recent national survey of peer specialists employed in paid positions in the United States, respondents reported spending approximately 25% of their time providing group support [11]. Decades of research have examined techniques of group facilitation to promote positive group processes; however, this research has solely focused on facilitation of groups by licensed providers [13]. To our knowledge, there is no research examining group co-facilitation by a licensed provider and peer facilitator together. Guidelines regarding how peer and non-peer facilitators can successfully co-facilitate group sessions are needed.

There is evidence that peer and non-peer co-facilitated groups can be effective. In a recent randomized controlled trial, Living Well, a group-based peer and non-peer co-facilitated intervention adapted from Lorig’s Chronic Disease Self-Management Program [14], improved medical illness self-management for adults with mental illness. Compared to an active control condition, Living Well participants achieved better self-management self-efficacy, patient activation, internal health locus of control, self-management behaviors, and mental health-related quality of life [8]. The present study examined qualitative interviews with Living Well participants and peer facilitators to examine how the peer and non-peer co-facilitation model affected group processes, with the aim of producing a set of recommendations for successful delivery of peer and non-peer co-facilitated groups.

Methods

Procedures

The present study utilized data from qualitative interviews from a subset (n = 16) of participants and all peer facilitators (n = 3) from a randomized controlled trial of Living Well [8]. For the larger trial, participants (N = 242) were recruited via chart review, clinician referral, and self-referral at three Mid-Atlantic Veterans Affairs Medical Centers in the United States between January 2014 and April 2016. Eligibility criteria included a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder with psychotic features, or post-traumatic stress disorder; a co-occurring chronic medical condition; engagement in mental health services at a study site; and capacity to consent. Interested and eligible participants completed written informed consent and were randomized to Living Well or an active control condition. Upon completion of the intervention, a subset of Living Well participants (n = 16) completed one-time 1–1.5 h qualitative interviews. Participants were purposefully chosen for variability in demographics, intervention attendance, and group cohort. All study procedures were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards.

Participants

A majority of the 16 Veteran participants were male (N = 15), with an average age of 58 years (range 47–75 years). Half (N = 8) identified as Black, with the remainder identifying as White (N = 6) or multi-racial (N = 2). Participant psychiatric diagnoses included psychotic disorders (N = 7), mood disorders (N = 8), and PTSD (N = 3), with two participants having more than one chart diagnosis. Most participants self-reported more than one medical diagnosis (N = 10), including lipid disorders (N = 10), cardiovascular disorders (N = 15), pulmonary disorders (N = 4), diabetes (N = 4), and arthritis (N = 2). The majority (n = 12) attended 7 or more out of 12 Living Well group sessions, with three participants attending between 3 and 6 sessions, and one participant attending only one session.

Peer facilitators (n = 3), two male and one female, were Veterans with a lived experience of mental illness and paid employees at the investigators’ research center, with varying educational backgrounds and experience in providing peer support. Facilitators were not certified peer specialists, though two out of three were pursuing certification. Peer facilitators completed written informed consent before participating in the interviews. All peer facilitators were interviewed after their first round of facilitating Living Well, and two of the peers were interviewed a second time approximately one year later. The other peer exited VA employment after his first interview.

Interview Process

Participant interviews focused on Veterans’ experiences with participating in the Living Well intervention, including their impressions of the quality of facilitation, with questions such as, “What did you think about having, [name], who is a peer, co-facilitate the group?”. Peer facilitator interviews focused on the peers’ experiences delivering the intervention, including training, co-facilitation, and supervision, with questions such as, “How was it working as a pair with a co-facilitator?”. Interviews were semi-structured, utilizing an interview guide to ensure that key topics were explored. All interviews were audio recorded with interviewees’ permission, professionally transcribed verbatim, and proofread for accuracy. Preliminary analysis of the first five interviews (with three participants and two peer facilitators) allowed for the identification of new questions and topics of interest, resulting in modification of the interview guides to address these topics.

Intervention

Living Well is a manualized, 12-session psychoeducational group intervention, adapted from the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program [14], that promotes medical illness self-management among adults with serious mental illness through didactics and skills training. Living Well groups were closed groups; approximately 4–6 Veterans were randomized to Living Well in each cohort. Groups were co-facilitated by a non-peer provider (a Masters-level research assistant, typically with a background in psychology) and a peer provider (a Veteran with lived experience of co-occurring mental health and medical conditions). Facilitators were trained by the study PI (RWG) through in-person workshops which included didactics, review of the manual and intervention materials, and role-play with feedback and repetition. Peer and non-peer facilitators were instructed to equally share group facilitation. Peer facilitators were instructed to engage in self-disclosure around relevant illness management experiences. Group sessions were video recorded for fidelity. Peer and non-peer group facilitators of both conditions were supervised by the study PI (RWG) in weekly 60-min supervision sessions, which consisted of review of select clips from group session video, verbal report from facilitators, and feedback and reinforcement from the study PI.

Data Analysis

Coding of Living Well Participant Interviews

Interview transcripts with Living Well participants were analyzed using a general inductive approach [15]. A codebook was iteratively developed with a combination of a priori and inductive codes. Final coding of each interview was completed independently by two members of the analysis team, in rotating pairs; each pair then met to reconcile coding. All coding was entered into NVivo 11 [16]. Relevant to the present analyses were the codes “Group Dynamics” (defined as the social dynamics of the group sessions, including feelings of (dis)comfort, camaraderie between Veterans and/or peer specialists, etc.) and “Facilitation” (defined as how the group was run (e.g., professionalism, tone-setting by facilitators) and the process of group delivery).

Summarizing Peer Facilitator Interviews

Because the group participant and peer interviews had different foci, we did not approach analysis of their interviews in the same way. Rather than coding, peer interview transcripts were summarized using an analytical memo template. The template was developed through review of the peer interview guide and the first two peer facilitator interviews to identify key domains [17, 18]. Templated memos were completed following each peer’s first interview by at least two members of the analysis team, who then met to reconcile and finalize the memo. Memos were updated following the second interviews to reflect additional experiences, again with at least two analysis team members coming to consensus on the final version, resulting in one memo for each peer facilitator.

Thematic Analysis

For the purposes of the present study, two sources of data were utilized: text data from participant transcripts coded under “Facilitation” and “Group Dynamics”, and peer facilitator memos and corresponding quotes from peer facilitator transcripts. Three authors (AM, ADP, KLF) engaged in thematic analysis [19] through a multi-step process of data review, note-taking, discussion, drafts, feedback, and consensus, to create a set of themes/subthemes, theme definitions/interrelationships, and a thematic map. These outputs were shared with another author (SMH), who independently reviewed and checked the data against the thematic map; feedback from this data check was incorporated into the final version.

Results

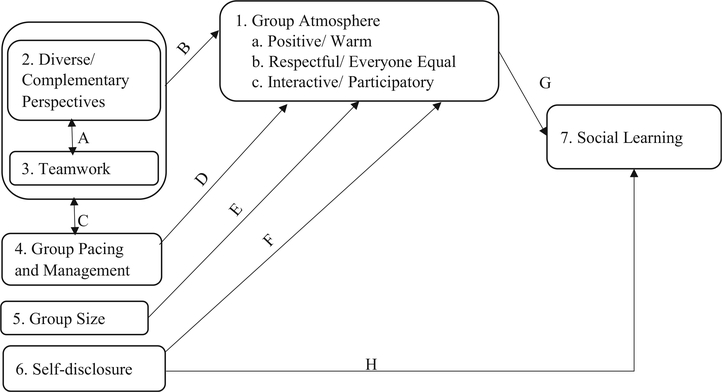

Seven interrelated themes were identified. Participants commented about the (1) “Group Atmosphere”, which was described as warm, respectful, and interactive. Thematically, there were five main contributors to this positive group atmosphere: the (2) “Diverse and Complementary Perspectives” of the co-facilitators, (3) “Teamwork” between the facilitators, (4) “Group Pacing and Management”, (5) “Group Size”, and peer facilitator and participant (6) “Self-Disclosure”. “Group Atmosphere” and “Self-Disclosure” both contributed to an environment conducive to (7) “Social Learning”.

A thematic map of theme interrelationships is presented in Fig. 1. Supporting quotes are presented in Table 1, arranged and labeled according to the lettered and numbered elements of Fig. 1. The narrative below maps on to numbered themes presented in both the table and the figure, and refers to theme interrelationships or “paths” in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A thematic map of theme interrelationships

Table 1.

Living well participant and peer facilitator example quotes regarding group facilitation and dynamics

| 1. Group atmosphere |

| a. Positive/ Warm |

| - P14: [B]y going to those classes and being with my peers, and the two ladies were wonderful. They were the type of ladies that you can talk to. They weren’t mechanical, you know… So it affects how I interact with you, you know. I’m a free spirit… And they made me feel comfortable. They made me feel comfortable in my own skin, you know. |

| b. Respectful/Everyone equal |

| - P6: What I liked about it, when we had our first group, they said, everybody in here, they wanted us to be respectful. That’s what I liked about the group. That’s what I liked about the facilitators. And I never did have a situation when I was there, and my concern was everybody was just respectful… And it was great. |

| - P9: We had one guy in the group… you couldn’t understand nothing he said… And they never once made him feel uncomfortable. They really, really respected his position on where he was. That’s why it was so cool, because it drove me nuts! It drove me nuts. And then, and I think they kind of saw my frustration. And they started paraphrasing for me… It was like he had a translator, you know, so yeah. |

| c. Interactive/ Participatory |

| - P7: I was a little surprised by how much participation we had in the group. Now, a lot of the groups that they hold here it can be a real quiet room. A lot people don’t want to contribute to it. |

| - P8. …everybody was, you know, was able to contribute. You can be late and contribute. You can be early and contribute…. and definitely [the facilitators], they were constantly just getting people, all of us, just to open up, and say, you know open up and hear the good news… and it worked quite well. It worked quite well. |

| 2. Diverse/ Complementary perspectives |

| - P3: You had [Peer] on one side. And you had [non-Peer] on the other side. So those were two different perspectives on what they’re going to throw out there to you. Whereas [non-Peer] might not understand, [Peer] would… You know, especially with the mental health issue. I mean, unless you’ve been there and done that, you don’t have a clue. |

| - F10: …having somebody with like book knowledge and lived knowledge, it’s great to combine the two together. |

| 3. Teamwork |

| - P9: And another thing that I really liked was… how well the staff and the peer counselors worked together, I liked that. And one thing I’ve learned, when you have more than one presenter, often times they will leave the room while the other person is presenting… And they all attended, they all stayed for all the sessions and they worked together as a group. And sometimes I even saw them kind of overlapping each other… they got so comfortable where they started kind of just blending. But it was seamless. |

| - F4: So she knew kind of the ins and outs of everything that she was doing and if I had any questions I could go to her. And then it was nice just to be able to depend on someone if you got stuck in a group and you were like, uh, uh, what do I say. |

| A. Diverse/Complementary perspectives ←→ Teamwork |

| - P14: …they worked hand in hand. And it was really interesting….[B]ecause one of them had a lot of funny ha, ha humor. And the other one had sort of a dry humor. So they complemented each other. |

| - F4: And [the non-peer staff] were able to jump in or provide another voice at times. And I thought it was nice to share because I could go in depth on some of the things that are peer-related and other. And she could go to other things. So I was kind of dedicated to that as—and we split it about half and half… almost exactly—the modules in terms of what we presented. |

| B. Diverse/Complementary perspectives + Teamwork → Group atmosphere |

| - P15: One thing I liked, they each had each other’s backs, and it’s probably a good thing to have two of them… so they can tag-team on each other and pass it back and forth. So it wasn’t like dead silence… I think it’s good that they can pair up and keep going… They talked about certain discussions and not very personal ones, just good discussions, like just good comments and questions about some places they grew up, like nice things in the beginning before they got into the class…. They kind of talked well with each other. Then they would ask us how we were doing and relax us a bit before we got into it… |

| - P16: Having two people to actually run the group was helpful. They rely on each other a lot to go back and forth and they help us start talking by bringing things up first and then made myself more open to bring things out that was wrong that I was fighting. |

| 4. Group pacing and management |

| - P12: Even those conversations that drift off …. It was efficiently used, I must say, from when it started, to when it finished…. There again, no matter how intricate or how intimate it got, personal, it was about the group, and the facilitators kept it contained within that, drift off a little bit, …but nonetheless, it stayed in the group. It stayed in the circle, on the subject. One subject might lead to another type of thing, and then we get right back on where we were, by, the facilitators did accommodate it. |

| C. Diverse/ Complimentary perspectives + Teamwork → Group pacing/ Management |

| - P7: …you got to have one facilitator to run the group, and to have a peer facilitator to help egg the group along, you know, and get some participation out of the group members and all. So I think you need both of them. |

| - F10: Because we come and practice every Monday and, pretty much, we’ve got it down…. there are some places, which even though it’s in the book, that says, “This is where the peer can make a comment about this.” … I found that she fits better, and there are other places outside of that that I fit better. Sometimes [non-Peer] looks at me and she says, “Well, [Peer], I think you might want to field this one,” and it’s nice to have that balance with what we’re teaching. |

| D. Group pacing/Management → Group atmosphere |

| - P12: And the facilitators were great in leading us into that discussion. So, you know, where everybody wasn’t just sitting around and, you know, just keeping what they were thinking in their head. They were great in leading us into where we can get it out there, you know. Everybody got a good idea by the time it was over with, and that’s with any particular situation… it was a smooth flow. |

| 5. Group size |

| - P9: I think more than eight or nine would be, maybe 10 would be too much, but two or three is not enough… You know, you don’t want 100 people. But you don’t want two people either. And sometimes our groups was only two people. |

| - P16: …it was nice to have a small group. It didn’t have to be three. Maybe six or eight. |

| E. Group size → Group Atmosphere |

| - P18: Well it was good because, like I say, for me there were never more than six people…. [I]t gave everyone a chance to get involved and…some of the groups in [mental health program] are so large that it was a challenge for everyone to actually feel relaxed and sharing….[T]hat was definitely the opposite, there was more than ample time and I felt relaxed. |

| 6. Self-disclosure |

| - P18: [Peer] spent a bit of time sharing with the group… Because she applied some of the techniques to her own life. And how… those techniques helped her. And she did bring up the fact that there’s an opportunity here for you. |

| F. Self-disclosure → Group atmosphere |

| - P9: I’ve learned over the years that a lot of times the people who are supposed to be teaching you about stuff, don’t have a clue, or insight, about what you should be doing, or how your life got to this point or whatever. … [Peer] brought some very, very, very personal anecdotes to the class that she didn’t have to. And that really made the group a more cohesive group, because she ripped a veil, for lack of a better word, she ripped a veil and allowed us to kind of open ourselves up because she put her stuff on the table too. |

| - P16: [Peer] helped… by the things he would say about himself and his problem. He had back problems and he had some mental problems. He had stuff. Would instantly group us altogether as a group… |

| 7. Social learning |

| - P2: Yeah, I thought it was great, especially learning from other people, yeah… How they deal with their mental health and physical health, and things that they do, you know, that helped me, that kind of stuff. |

| - P17: Sometimes it was a situation I was in. And that person had already been through it … and they mentioned something they did or experience that came out of it. And I said, oh wow, I could try that, too…. And that’s the really good part about the program is that everybody’s together – it’s individual but it’s also collective. So we can learn from each other. From the facilitator, also from each veteran, each of the veterans, and our network also. |

| G. Group atmosphere→ Social learning |

| - P17: Yeah, we were all very engaged because they made it interesting. And they made it so that we tried these things. If it didn’t work out for us… They didn’t kill you because you didn’t do it right or you didn’t work it out all the way. And if you almost made it and fell short, you’d just – you’d just be like I tried, I’ll try again next week. Persistence. You see?… Everyone had a chance to participate and like I said you hear so much that’s familiar… from each veteran… he’s saying something that you thought about or you heard before so you’re laughing. And that’s how this program ran. |

| H. Self-disclosure → Social learning |

| - P19: But you know some people go in there [group] with a little lack of confidence and self-esteem and you know they’re a little bit reserved. So when … you have a peer like that, they’re discussing things, it kind of opens them up a little bit more…. [Peer] would, every, every, every discussion that was started, the first example was always [Peer]. Okay? So he gave us his example to relate it to what we were talking about, whether it was getting more physical or eating better or whatever. And then they started around the table. So I think that helped out a lot. |

Quotations are arranged and labeled according to the lettered and numbered elements of Fig. 1. Living Well participants and peer facilitators were numbered 1 through 19. Group participants are noted with a “P” and peer facilitators are noted with an “F”

Theme 1: Group Atmosphere

The plurality of participant comments was about the atmosphere of the group, which fell into three subthemes: (a) Positive/warm, (b) Respectful/everyone equal, and (c) Interactive/participatory. More important than the peer versus non-peer distinction, or any demographic characteristic, was that the facilitators created a positive group atmosphere in which participants felt comfortable and safe. Facilitators treated each group member with dignity and respect, including group members whose symptoms made it difficult for them to communicate. Group facilitators also encouraged self-determination, making suggestions but emphasizing that the final decision was up to each participant. In addition, the group was interactive: participants felt comfortable opening up and facilitators encouraged participation and answered questions.

Themes 2 and 3: Diverse and Complementary Perspectives and Teamwork

Diverse and Complementary Perspectives

Interviewees generally reacted positively to the co-facilitation model, stating that each type of facilitator brought a different perspective to the group. The peer facilitator brought lived experience and helped them connect with the material presented, while the non-peer facilitator brought “book learning” and a fresh point of view. Diversity on characteristics like race and gender was also appreciated.

Teamwork

Participants commented that the two facilitators worked well together, treated each other with respect, split facilitation evenly, and “had each other’s backs”. The peer facilitators commented that they worked closely with the non-peer facilitators to review materials ahead of time and debrief afterwards. The peer facilitators felt comfortable asking the non-peer facilitators questions.

Interaction and Contribution to Group Atmosphere

Complementary perspectives were put to the best possible use when there was smooth and efficient teamwork. Because neither co-leader dominated the discussion, each was able to share information from his/her area of expertise, and group members could benefit from this diversity of input (path A). Diversity among the facilitators and teamwork between them also led to an environment that was comfortable for everyone, which positively impacted the group atmosphere (path B). The mutual respect between peer and non-peer facilitators set a tone for mutual respect among all group members, with everyone’s perspective acknowledged as equally valuable.

Theme 4: Group Pacing and Management

Most participants felt that the facilitators effectively managed the group, balancing discussion with covering important information. Facilitators worked together to divide up session material, with each facilitator bringing their point of view to the task (path C). Based on peer facilitator input, peer and non-peer facilitators had different roles in terms of group management. Non-peer facilitators were more focused on covering session material, and peer facilitators were more focused on participant narratives. Skillful group facilitation contributed positively to the atmosphere of the group (path D).

Theme 5: Group Size

Groups tended to be small (between 2 and 6 people). Some participants appreciated the small group size, saying it encouraged participation (path E); others, especially those who participated in more poorly-attended groups, said they wished the groups were bigger.

Theme 6: Self-Disclosure

Based on both participant and peer facilitator report, peer facilitator self-disclosure in the group occurred around various experiences, including Veteran status, mental illness, and health behaviors. Peer facilitator disclosure positively affected the group dynamic (path F), bringing diverse people together around common experiences, encouraging participant self-disclosure and vulnerability.

Theme 7: Social Learning

Participants emphasized that having a space to learn from each other was an important aspect of the group. The nonjudgmental and interactive group atmosphere facilitated discussion and brainstorming, which promoted learning and enhanced motivation (path G). Peer self-disclosure may have been the catalyst for others to self-disclose, prompting social comparison and learning from each other (path H).

Discussion

The present study examined the perspectives of peer facilitators of and participants in Living Well, a peer and non-peer co-facilitated group intervention to promote medical illness self-management for adults with serious mental illness. Overall, the co-facilitation model was positively received. Because the peer and non-peer facilitators brought diverse perspectives to the group and worked well together, the co-facilitation model and peer self-disclosure contributed positively to the group atmosphere, which was described as warm, respectful, and interactive. These factors also contributed to a space in which participants could share and learn from one another.

Participants spoke positively about the added benefit of a non-peer facilitator contributing a fresh perspective. Participants labeled the perspective of the non-peer facilitator as the “diverse”, outsider perspective, suggesting that participants perceived ownership of the group as a space for Veterans like themselves. This appears to be the key ingredient for the success of the co-facilitation model: establishing the norm that group participants and facilitators are equals, sharing and learning together.

Specific strategies for establishing this norm emerged from this work. First, the group atmosphere appears to mirror the relationship between the peer and non-peer facilitator. The two facilitators worked together as equals, splitting responsibilities evenly, and maintained respect for the unique perspectives everyone brought to the table. This teamwork was noted by group participants and signaled that if the peer facilitator was an equal to his/her colleague, then the group participants too, were equals in the space. A clear example of this parallel process: peer facilitators felt comfortable asking questions of the non-peer facilitators, just as Living Well participants felt comfortable asking questions of facilitators. A respectful collegial relationship between these two types of facilitators may be vital to the success of the co-facilitation model.

As in group therapy with two licensed providers, for the peer and non-peer facilitator to work well together, an agreed upon understanding of roles is needed. In the present study, facilitators prepared for groups beforehand, dividing up which sections each person would cover. In addition, there appeared to be an implicit understanding that the non-peer facilitator, typically with a formal training background in psychology, would focus on covering psychoeducational material, while the peer facilitator would focus on eliciting and sharing lived experiences; each facilitator was playing to his/her strengths and expertise. This may be a natural and complementary way to facilitate structured psychoeducational groups using the co-facilitation model, depending on the unique facilitation styles of the peer and non-peer facilitators in question. Explicit discussion of facilitator roles, as well as how each facilitator can contribute to successful group pacing, is recommended.

Peer self-disclosure was clearly an important component of the co-facilitation model and contributed significantly to positive group dynamics, as has been found previously in peer-facilitated health and wellness groups for this population [4]. Self-disclosure occurred across a variety of identities; peer facilitators should not feel beholden to only share their experiences as a mental health service user. In addition, we would recommend that as peer and non-peer facilitators discuss the content of a group session, facilitators could talk together about intentionally making space for peer self-disclosure. In advance, facilitators could decide together where in the session the peer might self-disclose on a particular topic. Strategies to make space for spontaneous, unplanned self-disclosure (e.g., as it is relevant to a topic brought up by a group member) should also be discussed – e.g., does the peer feel comfortable jumping in with that disclosure themselves? Should the peer facilitator signal in some way to the non-peer facilitator that they would like to add something? The strategies chosen will depend on the styles of the facilitators.

This study is not without limitations. Notably, the present study was conducted in the VA, with a structured intervention, and with peer facilitators who were early in their careers as peers. Exploration of co-facilitation outside the VA system, with larger groups, less structured interventions, non-male and non-Veteran participants, and more experienced or certified peers, are needed to further illuminate this topic. The present analysis also would have benefitted from input from the non-peer facilitators regarding their experiences. In addition, the original purpose of the qualitative interviews in the present study was to obtain general feedback on the Living Well intervention; therefore, the sample size was not selected with the present analysis in mind and we are unable to state whether data saturation was reached. Given that 12 interviews is generally sufficient to reach data saturation [20], the sample size in the present study is likely adequate.

Implications for Behavioral Health

In summary, the present study identified key strategies to promote the successful implementation of the peer and non-peer group co-facilitation model; see Table 2. This is the first study, to our knowledge, examining group co-facilitation by non-peer and peer facilitators together. Notably, it is not the intent of the authors to unnecessarily create a false dichotomy between peer and non-peer providers. Clearly, peer providers frequently have formal educational backgrounds and clinical training, and non-peer providers frequently have lived experience of mental health conditions. It is our hope that the guidelines delineated here will be flexibly applied as they make sense for each peer/non-peer facilitator pairing, thereby contributing to a shared understanding of respective roles and group processes that are positive, recovery-oriented, and effective.

Table 2.

Recommendations for peer and non-peer co-facilitated groups

| (1) Promote perceived ownership of the space by group members |

| (2) Encourage an atmosphere where group facilitators and members are equals |

| (3) Foster a respectful, collegial relationship between the peer and non-peer facilitator |

| (4) Set aside time for the peer and non-peer facilitator to explicitly discuss their respective roles in facilitating the group |

| (5) Assign the non-peer facilitator the role of keeping the group on task and covering all the necessary material and the peer facilitator the role of eliciting participation, if this is in keeping with their respective strengths |

| (6) Explicitly create space for peer self-disclosure, both structured and spontaneous, during group sessions. |

Acknowledgments

Funding Information This research was supported by the VA Health Services Research and Development Service (IIR 11–216; Dr. Goldberg, principal investigator), the VA Rehabilitation Research and Development Service (CDA IK2RX002339, Dr. Muralidharan, principal investigator; CDA IK2RX001836, Dr. Klingaman, principal investigator; and CDA IK2 RX002159, Dr. Hack, principal investigator), and the VISN 5 MIRECC. Dr. Fortuna was funded by a K01 award from the National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH117496).

Biography

Anjana Muralidharan is a clinical psychologist and researcher at the Veterans Capitol Healthcare Network (VISN 5), Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) in Baltimore, MD. The focus of her work is the promotion of holistic wellness and recovery among individuals with mental illness, the intersection of mental illness and aging, and the role and mechanisms of peer support for mental health recovery.

Amanda D. Peeples is a research health scientist and the Director of the Qualitative Research Unit at the VISN 5 MIRECC. Her research interests include mental health and illness among older adults, the role of peer support specialists, and long-term care.

Samantha M. Hack is a research health scientist at the VISN 5 MIRECC. Her research focuses on patient activation, patient-centered care, and identity-informed mental health care.

Karen L. Fortuna is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. She holds a doctorate in Social Welfare and a master’s degree in Social Work.

Elizabeth A. Klingaman is a psychologist and clinical researcher specializing in promoting the recovery of individuals with serious mental illness. She was awarded a VA Career Development Award in 2015 and is currently leading her research studies at the VA Maryland Health Care System.

Naomi F. Stahl is a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology at American University. She will complete her internship at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System, where she will focus her clinical work and research on Veterans with serious mental illness.

Peter Phalen is a clinical psychologist and post-doctoral research fellow at the VISN 5 MIRECC. His research interests include suicide, psychosis, and community mental health.

Alicia Lucksted is a clinical-community psychologist, research investigator at the VISN-5 MIRECC and Associate Professor in the University of Maryland School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry. Her work focuses on psychosocial intervention development and testing in mental health, internalized stigmatization regarding mental illnesses, and qualitative research in health services.

Richard W. Goldberg is the Director of the VISN 5 MIRECC and a Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and the University of Maryland, School of Medicine. His research portfolio includes both VA and NIH funded studies focusing on the quality of psychiatric and medical care for people living with serious mental illnesses and clinical intervention research focusing on improving the physical health status of mentally ill consumers.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the VA, the U.S. government, or other affiliated institutions.

Ethics Approval All study procedures were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards.

Consent to Participate All participants completed written informed consent.

Consent for Publication As part of the written informed consent process, participants were informed that data from the study may be published.

Code Availability N/A

Availability of Data and Material

Data will not be deposited.

References

- 1.Solomon P Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27:392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chinman M, George P, Dougherty RH, et al. Peer support services for individuals with serious mental illnesses: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(4):429–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson L, Bellamy C, Guy K, et al. Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry. 2012;11:123–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bochicchio L, Stefancic A, Gurdak K, et al. “We’re all in this together”: Peer-specialist contributions to a healthy lifestyle intervention for people with serious mental illness. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2019;46(3):298–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickerson FB, Savage CL, Schweinfurth LA, et al. The use of peer mentors to enhance a smoking cessation intervention for persons with serious mental illnesses. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2016;39:5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Druss BG, Singh M, von Esenwein SA, et al. Peer-led self-management of general medical conditions for patients with serious mental illnesses: a randomized trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;69:529–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fortuna KL, DiMilia PR, Lohman MC, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness of a peer-delivered and technology supported self-management intervention for older adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatry Q. 2018;89:293–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muralidharan A, Brown CH, Peer JE, et al. Living well: an intervention to improve medical illness self-management among individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;70:19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muralidharan A, Niv N, Brown CH, et al. Impact of online weight management with peer coaching on physical activity levels of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:1062–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young AS, Cohen AN, Goldberg RW. Improving weight in people with serious mental illness: the effectiveness of computerized services with peer coaches. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salzer MS, Schwenk E, Brusilovskiy E. Certified peer specialist roles and activities: results from a national survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:520–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinman M, Salzer M, O’Brien-Mazza D. National survey on implementation of peer specialists in the VA: implications for training and facilitation. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2012;35:470–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yalom ID. The theory and practice of group psychotherapy. 4th ed. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorig K Chronic disease self-management program: insights from the eye of the storm. Front Public Health. 2015;2:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27:237–46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.QSR International Pty Ltd: NVivo [computer software]. Doncaster. Australia: Victoria; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton A Qualitative methods in rapid turn-around health services research. Health services Research & Development. Available online at. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=780.. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will not be deposited.