Abstract

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an immune-mediated demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS). We have previously demonstrated that CNS-specific CD8 T cells possess a disease-suppressive function in MS and variations of its animal model, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), including the highly clinically relevant relapsing-remitting disease course (RR-EAE). Regulatory CD8 T cell subsets have been identified in EAE and other autoimmune diseases, but studies vary in defining phenotypic properties of these cells. In RR-EAE, PLP178–191 CD8 T cells suppress disease, while PLP139–151 CD8 T cells lack this function. In this study, we utilized this model to delineate the unique phenotypic properties of CNS-specific regulatory PLP178–191 CD8 T cells vs. non-regulatory PLP139–151 or OVA323–339 CD8 T cells. Using multiparametric flow cytometric analyses of phenotypic marker expression, we identified a CXCR3+ subpopulation amongst activated regulatory CD8 T cells, relative to non-regulatory counterparts. This subset exhibited increased degranulation and IFNγ and IL-10 co-production. A similar subset was also identified in C57BL/6 mice within autoregulatory PLP178–191 CD8 T cells, but not within non-regulatory OVA323–339 CD8 T cells. This disease-suppressing CD8 T cell subpopulation provides better insights into functional regulatory mechanisms, and targeted enhancement of this subset could represent a novel immunotherapeutic approach for MS.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS), an immune-mediated demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS), is characterized by T cell-mediated immunopathology. The majority of immunologic studies in MS focus on CD4 T cells, as they are widely believed to potentiate disease pathogenesis (1, 2). While fewer studies have focused on CD8 T cells, evidence suggests an important role for these T cells, as they are predominant and oligoclonally expanded within MS lesions (3).

In prior studies, we have demonstrated a regulatory role for myelin-specific CD8 T cells in MS and various forms of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the murine model of MS (4–9). In previous EAE studies, we have observed that myelin-specific regulatory CD8 T cells require MHC Class I presentation and production of IFNγ, and perforin (10). Furthermore, these effector molecules act at distinct time frames to mediate suppression of disease (11). Though regulatory CD8 T cells have been observed by several groups in the context of EAE as well as other autoimmune diseases, there is no current consensus on defining phenotypic markers for these CD8 T cells (12–16). Recently, we have demonstrated the disease-ameliorating function of activated CD25+ CD8 T cells in the context of relapsing-remitting EAE (RR-EAE) (9). Collectively, these studies support evidence that myelin-specific autoregulatory CD8 T cells are activated effector-like cells that target autoreactive mediators in demyelinating disease.

In RR-EAE, we have shown that both myelin proteolipid protein PLP178–191 (hereinafter referred to as P178) and myelin basic protein MBP84–104 (referred to as MBP84)-reactive CD8 T cells are able to ameliorate cognate disease (9). P178 CD8 T cells are even potent enough suppressors to ameliorate non-cognate disease when used in conjunction with P178-expressing Listeria monocytogenes (LM) infection to boost their induction (7, 8). Interestingly, PLP139–151 (hereinafter referred to as P139) CD8 T cells are unable to ameliorate P139 disease (9). Thus, the RR-EAE model presents a unique platform for further phenotypic delineation of regulatory autoreactive CD8 T cells.

Here, we set out to understand the underlying phenotypic and mechanistic distinctions between non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells and regulatory P178 CD8 T cells using the RR-EAE model. We show that non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells are similar to autoregulatory P178 CD8 T cells in activation status following antigenic restimulation. However, we identify a subset of activated CD8 T cells expressing CXCR3 that exhibited increased IL-10, IFNγ, and Granzyme B production within the regulatory P178 CD8 T cell group. Furthermore, this CXCR3+ subpopulation of regulatory CD8 T cells strikingly ameliorate RR-EAE. The divergence of these specific cell types allows us to more directly assess the function of regulatory myelin-specific CD8 T cells and may lead to improvements in strategies to target and enhance the function of these cells in MS therapies.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All experiments used 6–8-week-old female SJL/J or C57BL/6 mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed in a climate-controlled specific pathogen-free animal facility under the supervision of certified veterinarians, maintained on twelve-hour lights on/off cycle, and allowed food and water ad libitum. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Iowa’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All methods were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978).

Induction of EAE

SJL/J mice were immunized s.c. with 50μg of either PLP178–191 (NTWTTCQSIAFPSK) or PLP139–151 (HSLGKWLGHPDKF) peptide emulsified in 1:1 volume with complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) supplemented with 4mg/ml Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which was distributed over two sites on the flank. Mice immunized with P178 received 50ng pertussis toxin (ptx) administered on day 0 and 200ng ptx on day 2. C57BL/6 mice were similarly immunized using 100μg of PLP178–191 and given 250ng ptx on days 0 and 2 post-immunization. For adoptive RR-EAE, donor mice were immunized with PLP139–151 in CFA. At day 14, spleens and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested and reactivated with recombinant human IL-2 (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics) and cognate antigen for 72hr in culture as previously described (7, 10, 11). CD4 T cells were magnetically isolated using CD4 L3T4 microbeads (Miltenyi) and 3–5×106 blasting cells were transferred i.v. into recipient mice at times indicated (17). Clinical scores were assessed daily in a blinded manner, and animals were scored using the previously defined criteria (5): 0-normal mouse, 1-limp tail, 2- mild hind limb weakness, 3- moderate hind limb weakness/partial paralysis, 4- bilateral complete hind limb paralysis, and 5-moribund.

Adoptive transfer of CD8 T cells

Naïve mice were immunized with 50μg of PLP peptide (either P178 or P139) or OVA323–339 in CFA. At day 14, spleens and inguinal lymph nodes were collected and reactivated in culture with cognate antigens and hIL-2 for 72hr as previously described (4, 7–11, 18). At the end of culture, cells were collected, and CD8 T cells were magnetically isolated using Ly-2 microbeads (Miltenyi) and 10×106 live cells were transferred to recipient mice. Mice received CD8 T cell transfers i.v. prior to disease induction (d-1) or during the acute phase of disease (d11).

CNS cell-trafficking assay

One group of cells was suspended at a 1×106/ml concentration in PBS and incubated for 7 min with 0.25 mM CFSE. The competing group of cells was suspended at the same concentration in PBS but incubated for 15min with 680nM CMTPX. Each group of cells was then washed twice with serum-containing media. The two groups of cells were then mixed at a 1:1 ratio, resuspended in PBS, and injected i.v. into d11 immune mice so that each mouse received 10×106 cells total. The CNS, spleen, and inguinal lymph nodes of mice were harvested 48hr later and analyzed via flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry and multiparametric phenotypic analysis

Splenocytes and inguinal lymph node cells of P178- , P139-, or OVA-immunized donor mice were activated in culture for 72hr as described above. Cells were analyzed ex vivo and/or after 72hr restimulation with rIL-2 and cognate antigen. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were washed with FACs buffer and incubated with cell surface marker antibodies specific for Thy1.2 (30-H12), CD8α (53–6.7), CD25 (PC61), CD11a (2D7), and CD107a (1D4B), followed by permeabilization and fixation (eBioscience™ Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set) and staining for intracellular cytokines IFNγ (XMG1.2), IL-10 (JES5–16E3), and Granzyme B (GB11). For multiparametric flow cytometric analysis, cells were stained with the following panel of CD8 T cell activation markers: CXCR3 (CXCR3–173), CD27 (LG.3A10), CD103 (2E7), CD69 (H1.2F3), CX3CR1 (SA011F11), CD25 (PC61), NKG2D (C7), CD11a (2D7), CD122 (TM-β1), CD127 (SB/199), CD8a (53–6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), KLRG1 (2F1-KLRG1), and Thy1.2 (30-H12). All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences or Biolegend. All samples processed for flow cytometric analysis were run on a BD LSR II flow cytometer using FACSDiva5.0 software. Multiparametric single-cell data was processed through a cloud-based platform (Cytobank© PMID: 19933864) Spanning-tree Progression Analysis of Density-normalized Events (SPADE) followed by visualization of t-distributed Stocastic Neighbor Embedding (viSNE) algorithms of pre-gated activated CD8 T cells (Thy1.2+CD8α+CD11a+CD25+).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (La Jolla, CA). Single comparisons of two means were analyzed using Welch’s t test. For multiple comparisons, a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test was used. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

P139 CD8 T cells are neither regulatory nor pathogenic

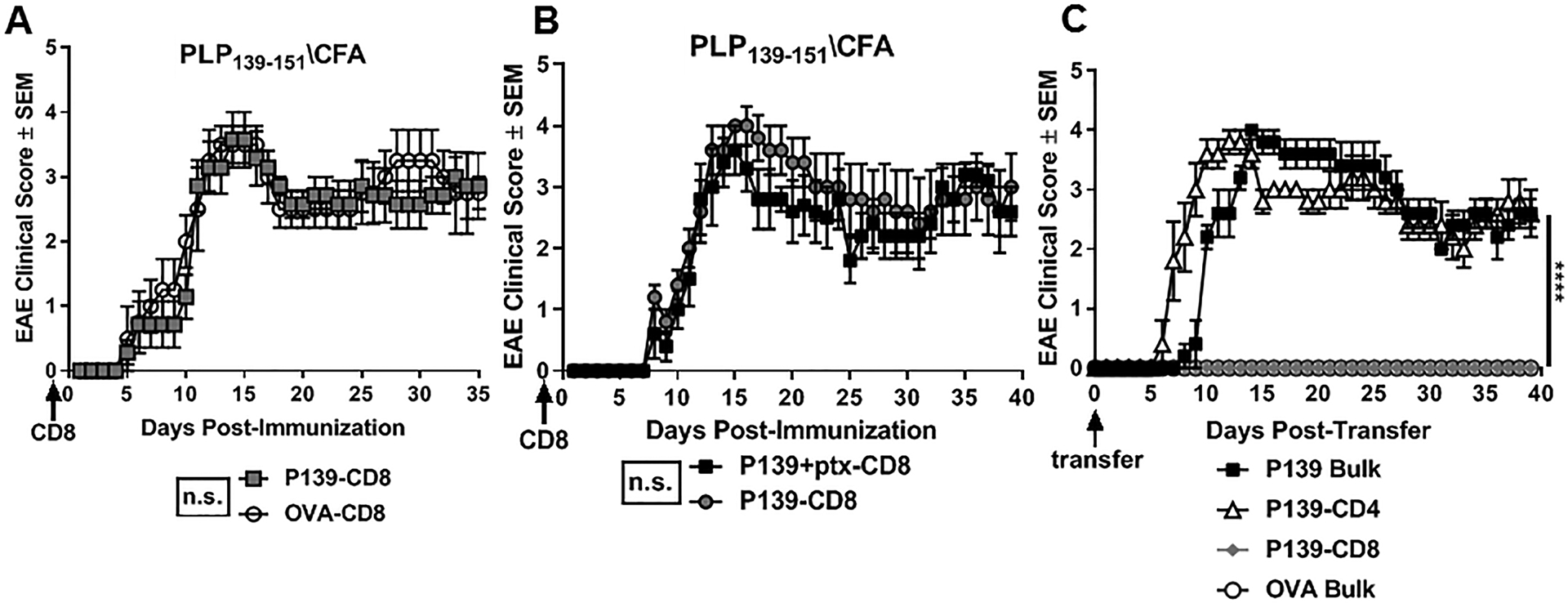

Previously, we have demonstrated that myelin-specific CD8 T cells can ameliorate disease in multiple models of EAE (4, 7–10). Recently, we showed that P178 CD8 T cells were able to ameliorate relapsing remitting disease in SJL/J mice, while P139 CD8 T cells neither suppressed nor exacerbated disease (confirmed in Fig. 1A). This discrepancy in regulatory potential prompted us to investigate the phenotypic and functional differences between “regulatory” P178 and “non-regulatory” P139 CD8 T cells. A few key differences between the P139 and P178 model of RR-EAE induction have been described in the literature (19). The SJL/J mouse strain has a higher precursor frequency of P139 CD4 T cells compared to P178 CD4 T cells, partly due to lack of thymic deletion to P139 (20), and thus P139 immunization does not require pertussis toxin (ptx) for induction. Ptx has long been used in EAE to facilitate trafficking of lymphocytes to the sites of inflammation and demyelination in the CNS (21, 22). To rule out whether ptx was required for regulatory CD8 T cell induction, donor mice were immunized with P139 and half were given ptx. P139 CD8 T cells were isolated from restimulation cultures as described above and transferred to naïve recipients. The following day, mice were immunized with P139/CFA without ptx. Mice that received P139 CD8 T cells from donors administered ptx exhibited no difference in disease course compared to those mice that received normal (non-ptx) P139 CD8 T cells (Fig. 1B), suggesting ptx is not sufficient to induce regulatory CD8 T cells.

Figure 1: P139-CD8 T cells are neither regulatory nor pathogenic.

SJL/J donor mice were immunized with P139/CFA (or OVA/CFA as a control). Splenocytes and inguinal lymph node cells (LNCs) were harvested on day 14 and cultured for 72hrs with cognate antigens and rIL-2. (A) P139- or OVA-CD8 T cells were sorted and transferred into naïve SJL/J recipient mice (d-1), followed by immunization the next day (d0) with P139/CFA. (B) On d-1, naïve mice received P139 CD8 T cells derived from donor mice immunized with either P139 alone or P139 with ptx. On day 0, EAE was induced with P139/CFA immunization and mice were monitored for clinical disease. (C) P139-CD4 T cells, P139-CD8 T cells, or bulk cells from PLP139- or OVA-stimulated cultures were adoptively transferred to naïve SJl/J recipient mice (d0), followed by monitoring for EAE. Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments with 3–5 mice per group per experiment. ****p<0.001 and ns=not significant.

Next, to directly test whether P139 CD8 T cells might harbor pathogenic potential, we adoptively transferred these cells into naïve recipients and monitored for signs of clinical disease (23, 24). Donor mice were immunized with P139/CFA (or OVA (OVA323–339)/CFA). At day 14, splenocytes and lymph node cells (LNCs) were harvested and restimulated in vitro for 72hrs with cognate antigen. Bulk cells from these cultures vs. sorted CD4 T cells vs. CD8 T cells were then adoptively transferred into different groups of naïve recipients. Non-relevant OVA-stimulated bulk cultures were transferred as a negative control. While mice that received P139 bulk or P139 CD4 T cells exhibited typical RR-EAE, mice that received P139 CD8 T cells alone never developed disease (Fig. 1C), suggesting that though P139 CD8 T cells are not regulatory, they are likewise non-pathogenic. The earlier onset of disease in mice given P139 CD4 T cells compared to P139 bulk cells is likely explained by a larger overall number of pathogenic CD4 T cells transferred, rather than suggestive of a protective role for P139 CD8 T cells. This interesting deviation of CD8 T cells in the P139 RR-EAE model from other models of EAE in SJL and B6 mice (4, 7–9) provides a platform to delineate phenotypic differences between regulatory and non-regulatory CD8 T cells in RR-EAE.

No distinct activation differences between regulatory P178 CD8 T cells and non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells

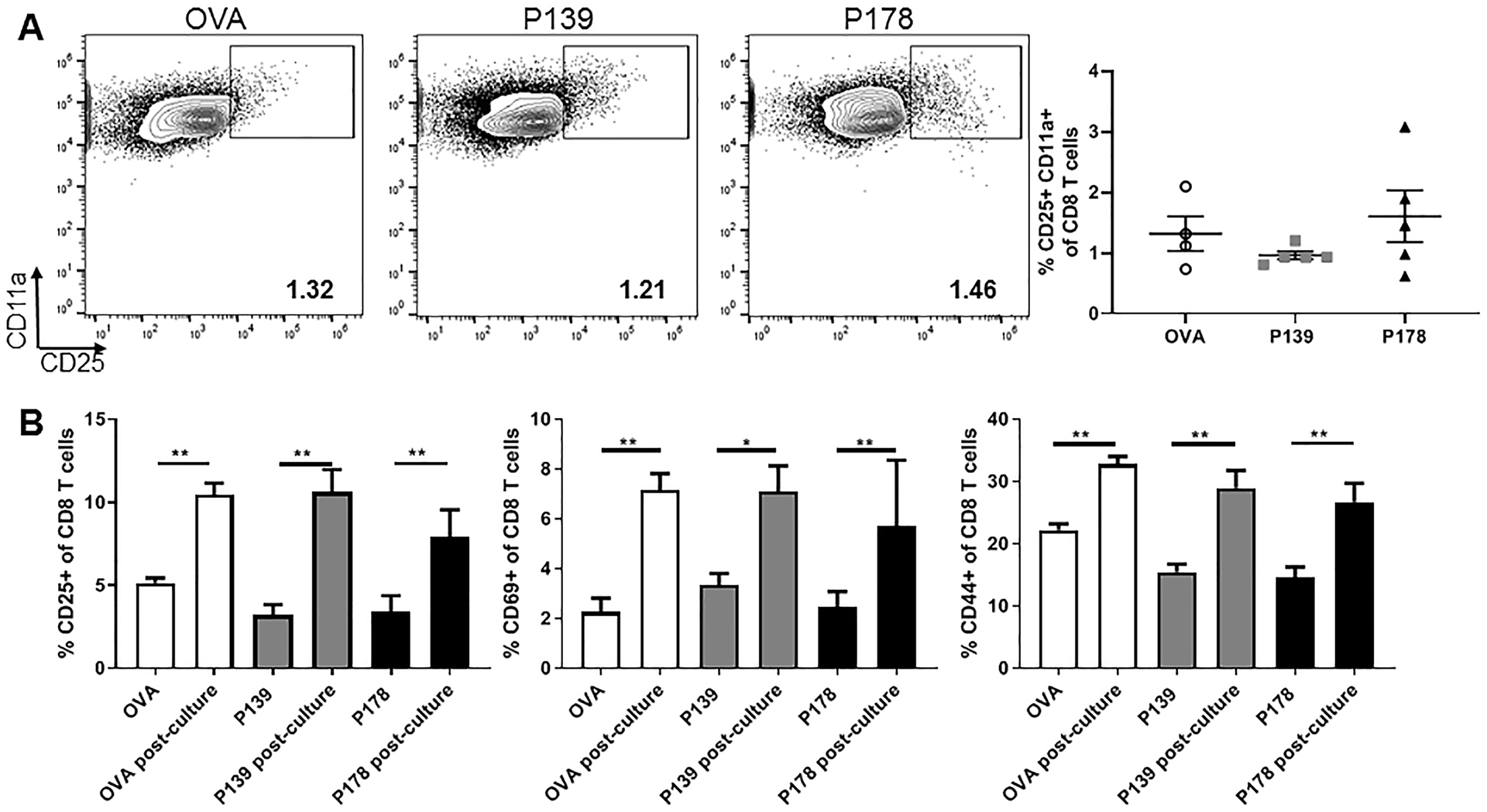

In a recent study from our group, we demonstrated an enrichment for regulatory function among activated CD25+ subset of CD8 T cells (9). Given these findings, we next asked whether a disparity in activation status could account for the functional difference between regulatory vs. non-regulatory CD8 T cells. Using flow cytometry, we compared regulatory P178 CD8 T cells to non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells and control OVA CD8 T cells following 72hr culture. Frequency of activated CD8 T cells as defined by CD25+CD11a+ were not different post-culture between the regulatory P178 or non-regulatory P139 groups (Fig. 2A). Both bulk P178 CD8 T cells and P139 CD8 T cells equally upregulated activation makers CD25, CD69, and CD44 during the 72hr culture, even compared to control OVA CD8 T cells (Fig. 2B). Together, these data indicate that P139 CD8 T cells are not defective in activation in response to antigen stimulation.

Figure 2: P178 CD8 T cells and P139 CD8 T cells are equally activated post-culture.

LNCs and splenocytes from P178- , P139-, or OVA-immunized SJL/J donor mice were harvested on day 14 and activated in vitro with cognate antigen and IL-2 for 72hr. Post-culture cells were first gated on Thy1.2+ CD8 T cells. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots are shown for CD25+ CD11a+ expression on CD8 T cells for each group. Frequency of these activated cells is shown. (B) Cell samples were taken before culture (ex vivo) and post-culture. Frequency of CD8 T cells expressing CD25, CD69, or CD44 is shown. Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments each with 5 mice per group. **p<0.01

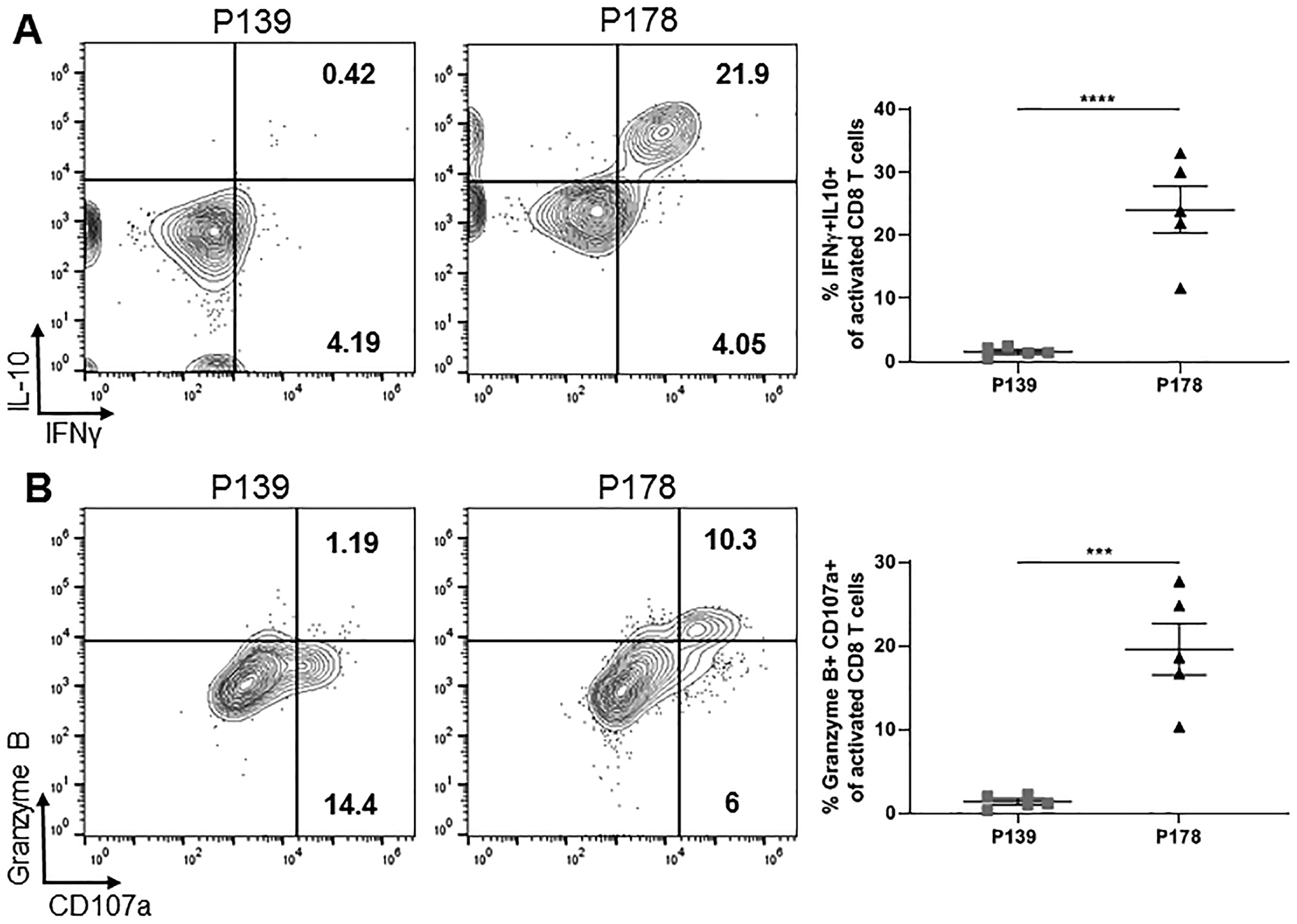

To explore functional differences between activated regulatory vs. non-regulatory CD8 T cells, we looked for distinctions in cytokine production between P178 and P139 groups following our 72hr restimulation. Focusing on activated CD25+CD11a+ CD8 T cells, we found a that regulatory P178 CD8 T cells displayed increased IL-10 and IFNγ production (Fig. 3A). Additionally, activated regulatory P178 CD8 T cells displayed increased expression of degranulation marker CD107a (LAMP1) and Granzyme B secretion post-culture compared to activated non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells (Fig. 3B). These data suggest that activated regulatory CD8 T cells have a distinct functional profile compared to non-regulatory CD8 T cells.

Figure 3: Activated regulatory P178 CD8 T cells are functionally distinct from non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells.

LNCs and splenocytes from P178- or P139-immunized SJL/J donor mice were harvested on day 14 and activated in vitro with cognate antigen and IL-2 for 72hr. Post-culture cells were first gated on Thy1.2+ CD8 T cells and then CD25+CD11a+ activated cells. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots are shown for IL-10- and IFNγ-producing activated CD8 T cells for each group and frequency is shown. (B) Representative flow cytometry dot plots are shown for CD107a+ and Granzyme B-producing activated CD8 T cells for each group and frequency is shown. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments each with 4–5 mice per group. ***p<0.001 and ****p<0.0001

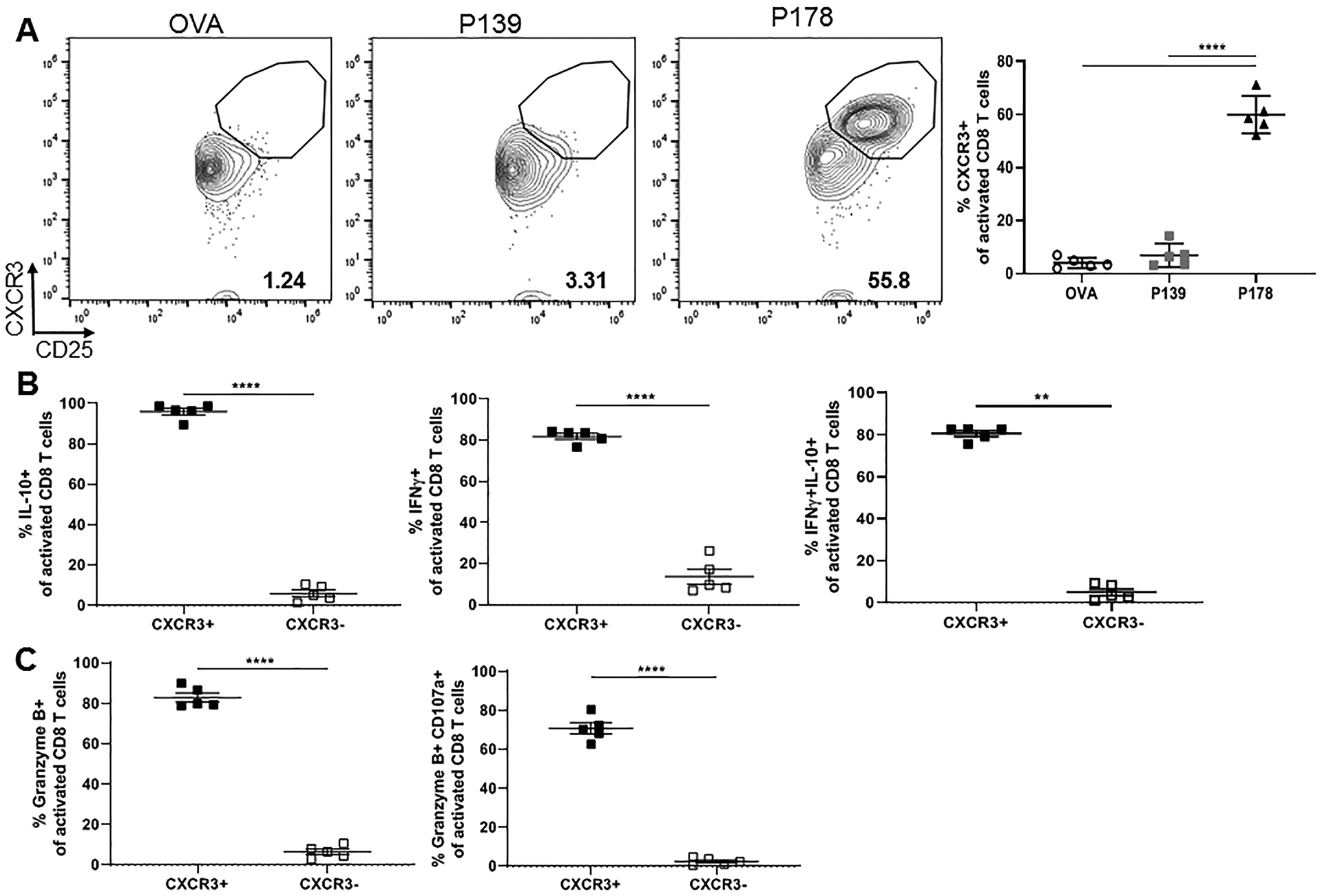

A functionally distinct CXCR3+ subpopulation is identified within regulatory P178 CD8 T cells that is absent in non-regulatory P139 or OVA CD8 T cells

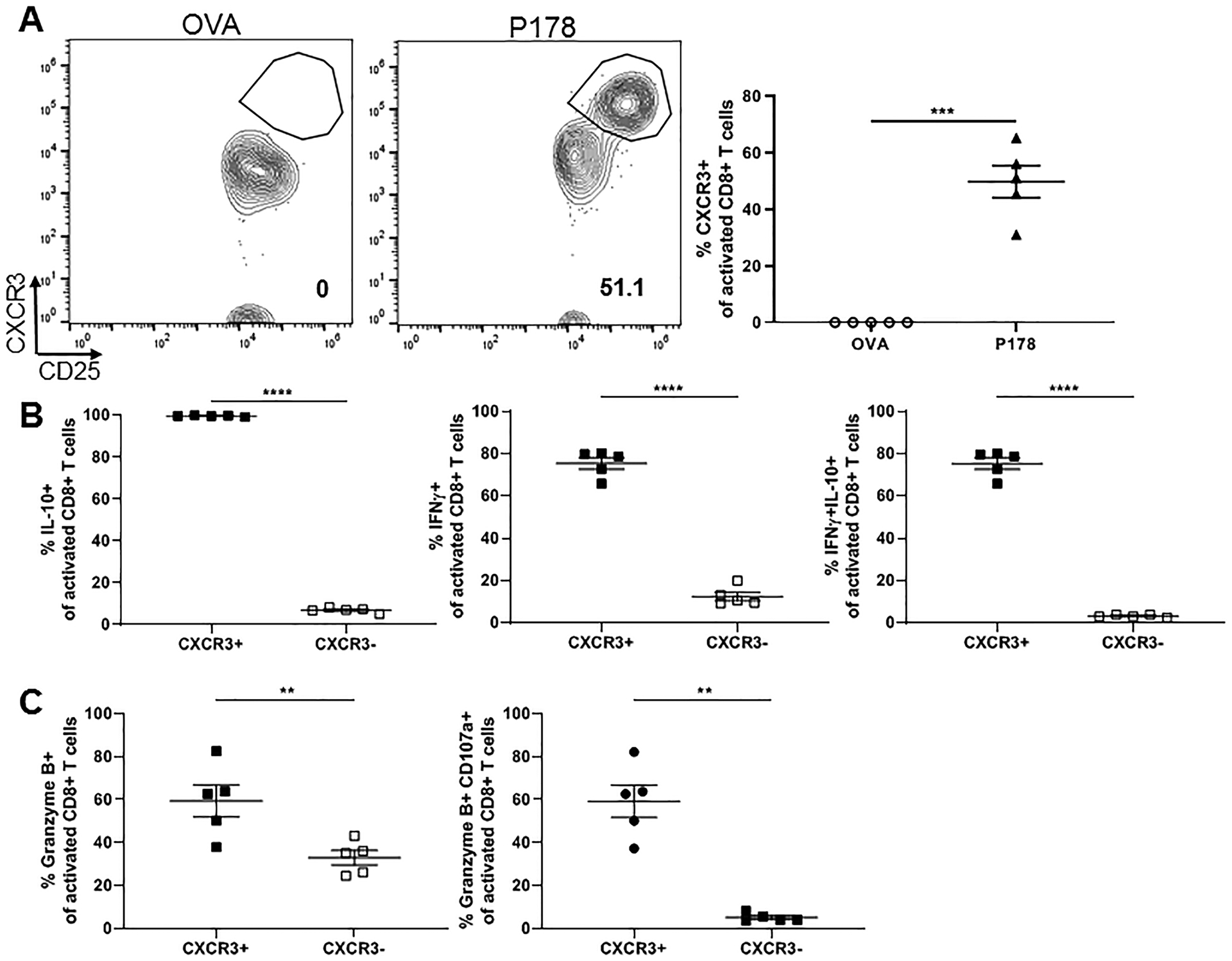

We have shown previously that IFNγ production is a required feature of autoregulatory CD8 T cells (10, 18). Recently, we have also demonstrated that lack of IFNγ responsiveness correlated with decreased CXCR3 expression in chronic EAE , suggesting decreased motility (18). To determine if CXCR3 expression might distinguish regulatory from non-regulatory CD8 T cells in RR-EAE, we compared CXCR3 expression in activated P178 vs. P139 CD8 T cells following 72hr restimulation. Indeed, we found a high frequency of CXCR3+ cells among activated CD8 T cells in the regulatory P178 group that was mostly absent in the non-regulatory P139 and OVA groups (Fig. 4A). To determine whether this CXCR3+ subpopulation was primarily responsible for the distinct functional phenotype observed earlier, we compared cytokine production between CXCR3+ and CXCR3- fractions within the activated P178 CD8 T cell population. As shown in Figure 4B, the CXCR3+ subset accounts for nearly all IL-10+, IFNγ+, and double-producing activated P178 CD8 T cells. Furthermore, the CXCR3+ subset accounts for the increased expression of degranulation marker CD107a and Granzyme B secretion (Fig. 4C). Together, these data suggest that activated regulatory P178 CXCR3+ CD8 T cells are a functionally distinct population from activated non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells.

Figure 4: Subpopulation of CXCR3+ identified among activated regulatory P178 CD8 T cells.

LNCs and splenocytes from P178- , P139-, or OVA-immunized SJL/J donor mice were harvested on day 14 and activated in vitro with cognate antigen and IL-2 for 72hr. Post-culture cells were first gated on Thy1.2+ CD8 T cells and then CD25+CD11a+ activated cells. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots are shown for CXCR3 expression on activated CD8 T cells for each group and frequency is shown. (B) Frequency of IL-10- and IFNγ-producing CXCR3+ vs CXCR3- activated P178 CD8 T cells is shown. (C) Frequency of CD107a+ and Granzyme B-producing CXCR3+ vs CXCR3- activated P178 CD8 T cells is shown. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments each with 3–5 mice per group. **p<0.01 and ****p<0.0001

Our group has previously shown a regulatory role for CD8 T cells in multiple models of EAE, including P178-induced chronic disease in C57BL/6 mice (7, 8, 11). To confirm the functional phenotype of this CXCR3+ subpopulation of regulatory CD8 T cells in the chronic EAE model, we analyzed LNCs and splenocytes from P178-immunized C57BL/6 mice following 72hr restimulation with cognate antigen and IL-2. We again found an increased population of CXCR3+ activated CD8 T cells in the P178 group that was absent in the OVA control group (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, this CXCR3+ subpopulation of activated CD8 T cells exhibited a similar phenotype of increased IL-10 and IFNγ production (Fig. 5B) and increased degranulation (Fig. 5C) observed in relapsing-remitting mice. These data suggest that CXCR3 could distinguish an IFNγ and IL-10-producing regulatory CD8 T cell population across multiple models of EAE.

Figure 5: CXCR3+ subpopulation of regulatory CD8 T cells is present in multiple EAE models.

LNCs and splenocytes from P178 or OVA-immunized C57BL/6 donor mice were harvested on day 14 and activated in vitro with cognate antigen and IL-2 for 72hr. Post-culture cells were first gated on Thy1.2+ CD8 T cells and then CD25+CD11a+ activated cells. (A) Representative flow cytometry dot plots are shown for CXCR3 expression on activated CD8 T cells for each group and frequency is quantified. (B) Frequency of IL-10- and IFNγ-producing CXCR3+ vs CXCR3- activated CD8 T cells is shown. (C) Frequency of CD107a+ and Granzyme B-producing CXCR3+ vs CXCR3- activated CD8 T cells are shown. Data are representative of 2–3 independent experiments each with 3–5 mice per group. **p<0.01

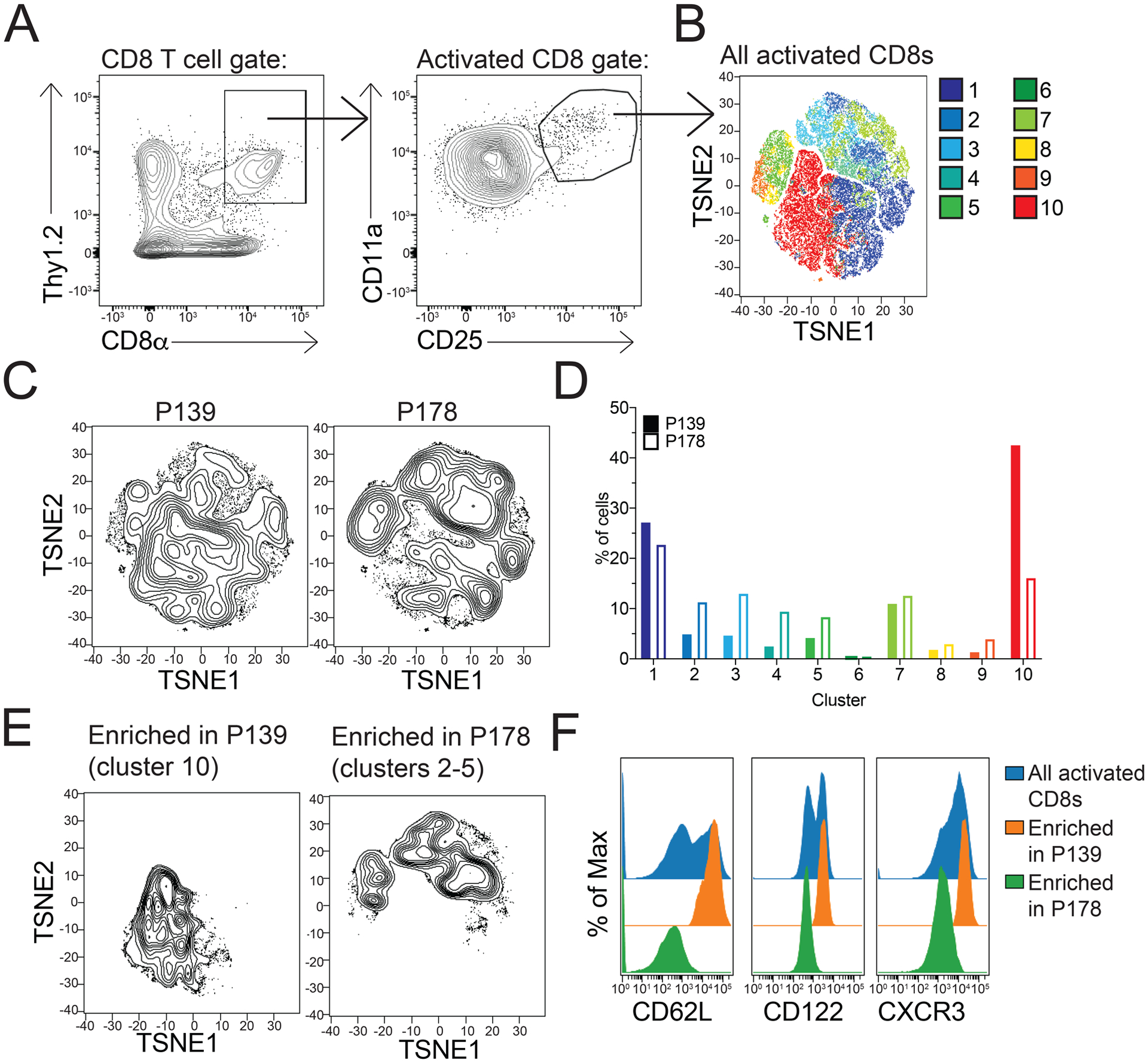

Given the dramatic difference in frequency of CXCR3+ activated CD8 T cells between regulatory and non-regulatory CD8 T cells post-activation, we asked whether this subpopulation could be visualized ex vivo based on surface immunophenotypic features without any in vitro activation. To address this, we utilized the non-biased clustering analyses SPADE and viSNE. SPADE clusters cells with similar phenotypic expression and viSNE then reduces high-parameter data down to two dimensions (25). This allows visualization of highly specific subset differences between P178 and P139 CD8 T cells. To this end, splenocytes and LNCs were harvested on day 14 from P178- and P139-immunized mice and stained ex vivo with a panel of CD8 T cell differentiation markers and flow cytometry was performed. In order to assess phenotypic subset differences by surface marker expression, we specifically gated on the CD11a+CD25+ activated populations of CD8 T cells prior to intricate subset analysis (Fig 6A). SPADE analysis identified the clustering motifs overlaid in the viSNE analysis displayed in Figure 6B. Notably, there was a differential distribution of the activated CD8 T cells between the P139 and P178 groups indicating differences in the representation of subsets of CD8 T cells (Fig 6C). This led to differences in the representation of cells within the clusters identified via SPADE analysis (Fig 6D). In particular, cluster 10 was enriched in P139 cells while clusters 2–5 exhibited similar enrichment in P178 cells (visualized in Fig 6E). Remarkably, analysis of the defining factors for these clusters revealed CXCR3 expression as one of the greatest differences between these clusters, along with CD62L and CD122 (Fig 6F). Thus, CXCR3 expression is distinct in regulatory P178 CD8 T cells compared to non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells, even prior to 72hr restimulation.

Figure 6: P178-immunized mice harbor distinct populations of CD8 T cells ex vivo compared to P139-immunized mice.

Splenocytes and draining LNCs from P178- , P139-, or OVA-immunized SJL/J donor mice were harvested on day 14 and activated in culture with cognate antigen and IL-2 for 72hr. Post-culture cells were stained with a panel of CD8 T cell activation markers, and viSNE analysis was performed. (A) Gating strategy for Thy1.2+CD11a+CD25+ activated CD8 T cells. (B) Representative TSNE plot for all samples indicating clusters of differentiation. (C) Representative TSNE showing differential cluster enrichment in P139 CD8 T cells compared to P178 CD8 T cells. (D) Frequency of cells in each cluster for P139 and P178 CD8 T cell samples. (E) Representative TSNE plots of only the enriched clusters for P139 and P178 CD8 T cell samples. (F) MFI of CD62L, CD122, and CXCR3 expression in P139 and P178 CD8 T cell samples. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments each with 3–5 mice per group. *p<0.05.

Regulatory and non-regulatory CD8 T cells traffic in similar frequency to the CNS during RR-EAE

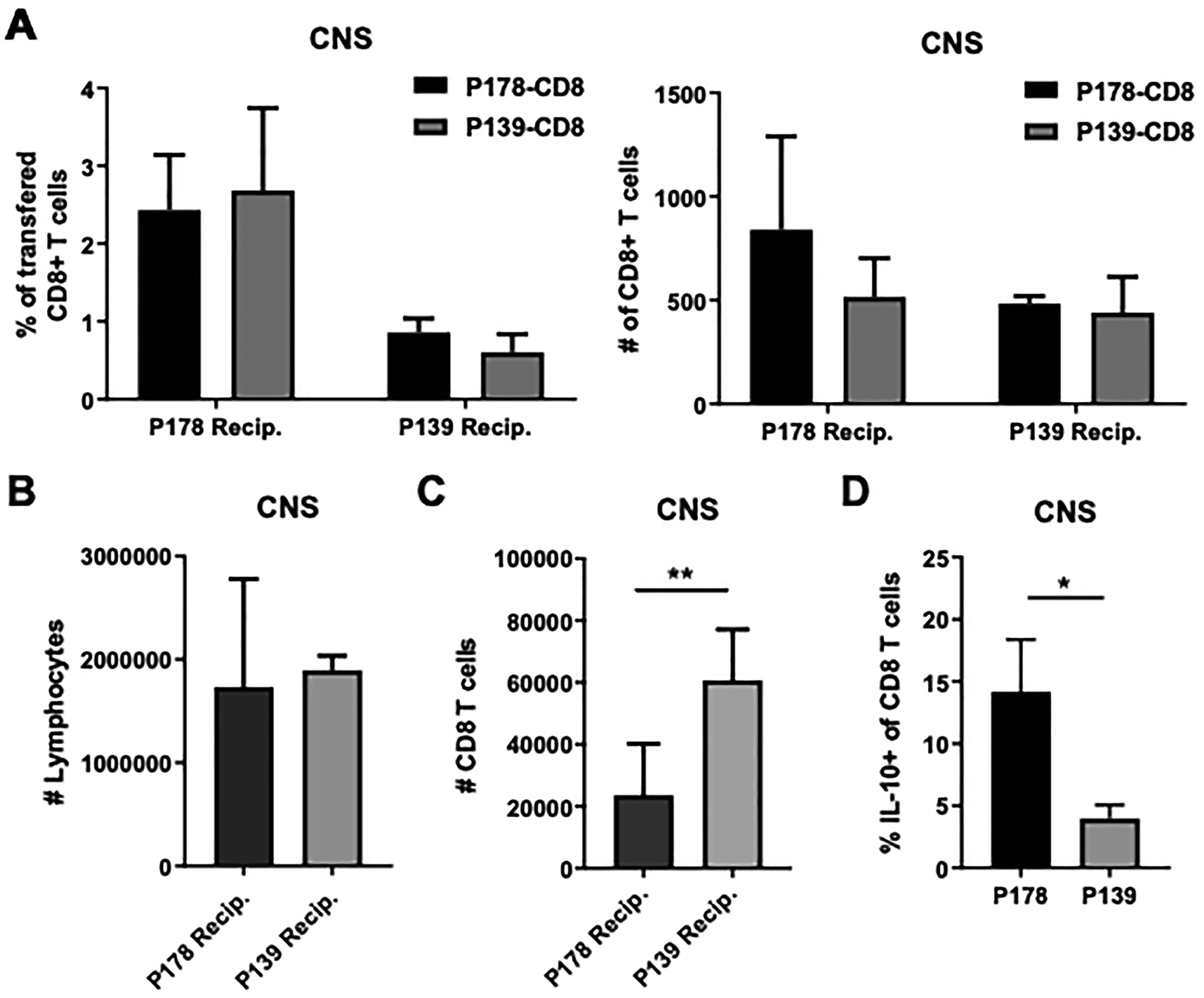

Chemokine receptor CXCR3 is important for immune cell migration to the CNS, particularly for Th1 cells (22, 26–28). Given that non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells express little CXCR3, we addressed the possibility that non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells may not traffic as efficiently to the CNS as regulatory P178 CD8 T cells. For this, we utilized cell tracer dyes to track movement of each cell type in vivo. Prior work has demonstrated that P178 CD8 T cells are able to suppress ongoing P178 disease within days of adoptive transfer (9), while P139 CD8 T cells lack this function. Therefore, P139- or P178-immunized donors were used to obtain in vitro-activated CD8 T cells, as described above. P178 CD8 T cells were stained with CFSE (a cytoplasmic dye detected in the 494/521 nm spectrum) and P139 CD8 T cells with CMPTX (a different colored cell tracer dye detected in the red 577/602 nm spectrum) and transferred at a 1:1 ratio into recipient mice that had been immunized for EAE induction 11 days prior. After 48hr, the CNS, spleen, and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested from these recipients, and flow cytometry was used to quantify the population of transferred CD8 T cells in these organs. Surprisingly, a similar frequency and absolute number of P178 and P139 CD8 T cells were found in both the CNS (Fig. 7A) and spleens and lymph nodes (data not shown) of P178-immunized recipient mice. Similarly, there was no difference in frequency or absolute number of P178 and P139 CD8 T cells found in the CNS of P139-immunized recipient mice, suggesting that P178 and P139 CD8 T cells traffic similarly within the host (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7: P178 CD8 T cells and P139 CD8 T cells traffic similarly to the CNS.

CD8 T cells were isolated from P178-immunized SJL/J donor mice and stained with CFSE. P139 CD8 T cells were isolated from donor mice and stained with CMPTX. Stained P178 CD8 T cells and P139 CD8 T cells were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and 10×106 total cells were transferred into d11 recipient mice (either immunized with P178 or P139). After 48hrs, the brain and spinal cord were harvested from recipients, and frequency and number (A) of transferred CD8 T cells were determined using flow cytometric analysis. Total number of lymphocytes (B) and CD8 T cells (C) within recipients is shown. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with 4–6 mice per group per experiment. ns=not significant. In Panel D, P178- and P139-immunized mice were evaluated for presence of IL-10+ CD8 T cells in the CNS.

When comparing the P178- to the P139-immunized recipients overall, there appeared to be a lower frequency of recovered CD8 T cells in the CNS of P139 mice, which may indicate a lack of CD8 T cell trafficking altogether in these recipients (left panel Fig. 7A). However, there was an equal number of recovered CD8 T cells from both P178 and P139 donor mice, and an equal number of total lymphocytes in the CNS of these mice (Fig. 7B). The total number of CD8 T cells was increased in the CNS of P139 recipients, indicating that the frequency of recovered CD8 T cells in P139 is a smaller proportion of these CD8 T cells (Fig. 7C). Overall, little difference in trafficking ability was detected between non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells compared to regulatory P178 CD8 T cells.

We next asked whether the subpopulation that was characteristic of regulatory P178 CD8 T cells could also be detected in the CNS. For this analysis, we used IL-10 positivity as a surrogate marker for the regulatory subset (based on data in Figs. 3–4). Indeed, we found that IL-10+ CD8 T cells were readily detected at an increased frequency in the P178 context compared to P139 (Fig. 7D), indicating that these cells do reach the CNS and suggesting that part of the action could happen at the site of pathology.

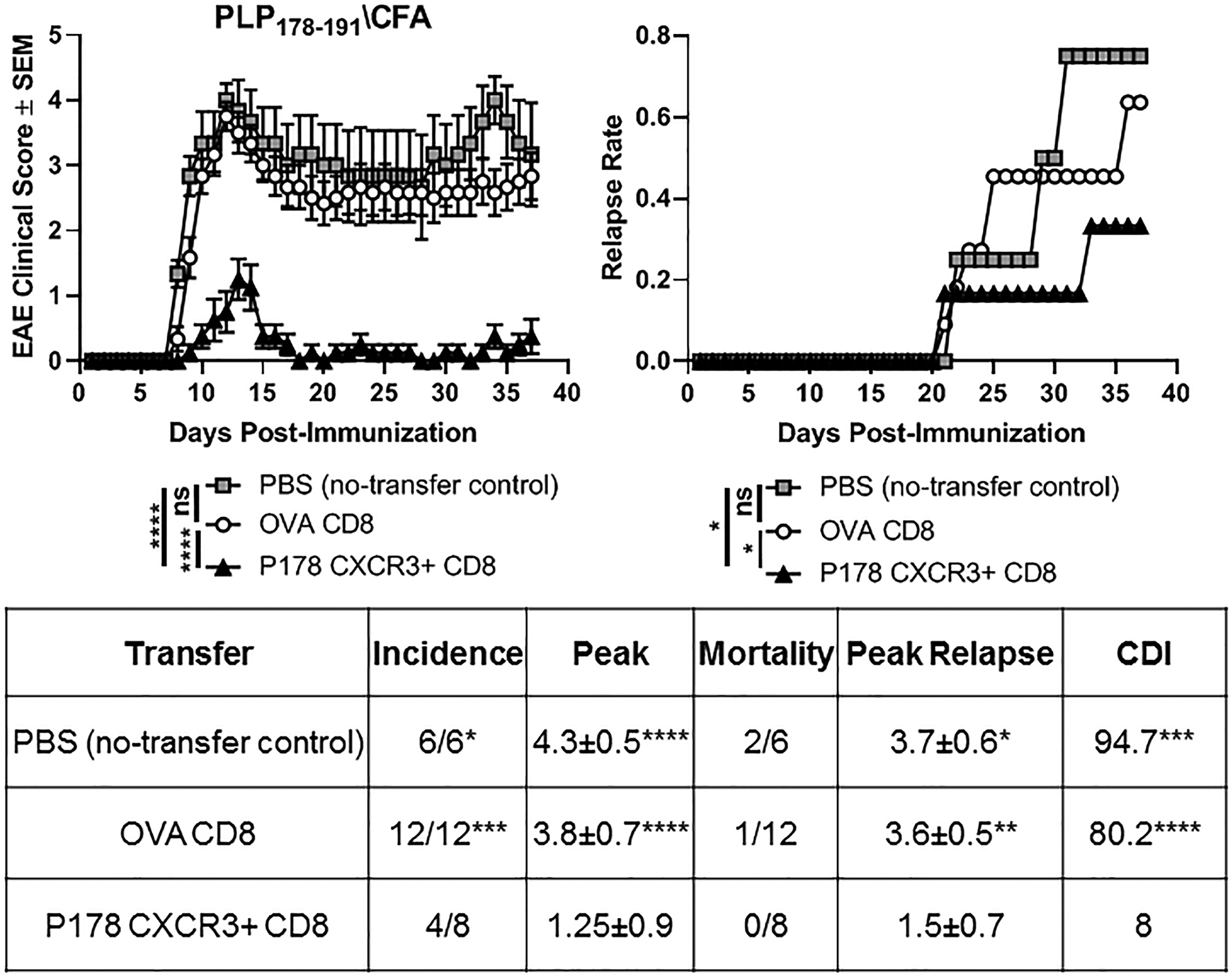

P178 CXCR3+ CD8 T cells ameliorate relapsing disease

While CXCR3 is largely implicated in cell migration, expression on CD8 T cells is also associated with enhance effector differentiation (29). Therefore, it is possible that regulatory CD8 T cell disease-supressing function takes place in the periphery, rather than the CNS. To determine whether just the CXCR3+ subset of CD8 T cells can suppress RR-EAE, donor mice were immunized with P178/CFA (or OVA/CFA as a control) and at day 14, splenocytes and LNCs were harvested and restimulated in vitro for 72hrs with cognate antigen. CXCR3+ CD8 T cells were enriched by bead-sorting and adoptively transferred into naïve recipients, and recipients were immunized the following day. Mice that received CXCR3+ P178 CD8 T cells experienced little to no clinical disease symptoms compared to OVA CD8 T cells and the no-transfer controls (Fig. 8 left panel). Furthermore, those CXCR3+ CD8 T cell recipients that did show clinical symptoms had fewer relapses and a reduced peak relapse score compared to control mice (Fig. 8 right panel). This data suggests that the CXCR3+ subpopulation of CD8 T cells are not only sufficient, but potent suppressors of relapsing autoimmune demyelinating disease.

Figure 8: CXCR3+ P178 CD8 T cells radically suppress RR-EAE.

SJL/J donor mice were immunized with P178/CFA (or OVA/CFA as a control). Splenocytes and LNCs were harvested on day 14 and cultured for 72hrs with cognate antigens and rIL-2. P178 or were sorted via negative selection followed by a positive selection CXCR3 sort. CXCR3+ P178 or OVA CD8 T cells were adoptively transferred into naïve SJL/J recipient mice (d-1), followed by immunization the next day (d0) with P178/CFA followed by monitoring for EAE. PBS was used as a no-transfer control. Mean clinical scores (left panel) and relapse rates (right panel) are shown. Data representative of 6–12 mice per group. **p<0.05, **p<0.01, **p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, ns=not significant.

Discussion

The key to stopping the progression of MS lies in understanding the different components of the immune processes underlying its pathogenesis and regulation. One such component that remains underappreciated is the function of CD8 T cells in MS. We have now demonstrated many instances in which myelin-specific CD8 T cells protect and suppress EAE, rather than contribute to disease progression (4, 7, 9–11). Furthermore, we have observed that CD8 T cells from MS patients undergoing disease exacerbation (relapse) have diminished suppressive capacity (6, 30, 31), indicating CD8 T cells may be indispensable in mitigating relapse biology.

Several groups have now observed regulatory CD8 T cells not only in the context of EAE, but in other autoimmune diseases as well (14–16). The phenotypic distinction of regulatory CD8 T cells in MS and EAE has not been agreed upon (12). Previously, we showed that disease-ameliorating CD8 T cells reside within the activated CD25+ population (9). Other groups have also shown regulatory CD8 T cells within the CD25+, CD122+, or CD28- fractions, amongst other phenotypes (32–34). In this study we found a similar frequency of CD25+CD11a+ activated CD8 T cells in P139- and P178-immunized mice (Fig 2A). Furthermore, non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells upregulate activation markers CD25, CD69, and CD44 equally compared to regulatory P178 CD8 T cells after antigen stimulation in culture (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cell activation status (based on single expression of activation markers) is indistinguishable from regulatory P178 CD8 T cells.

Based on previous studies demonstrating suboptimally suppressive CD8 T cells express less CXCR3 (18), we hypothesized that regulatory CD8 T cells had increased CXCR3 expression. Indeed, we found a distinct CXCR3+ subpopulation within activated regulatory CD8 T cells that was absent in non-regulatory CD8 T cell groups (Figs. 4 & 5). Using non-biased clustering analyses, we were able to identify CXCR3 expression as distinct between non-regulatory P139 and regulatory P178 CD8 T cells even prior to antigenic restimulation (Fig 6) (35). Interestingly, we demonstrated that non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells are not inhibited from access to CNS and traffic to this site of inflammation in similar number and frequency as regulatory P178 CD8 T cells (Fig 7). Rather, P178 CD8 T cells are qualitatively different in their cytokine expression (IFNγ+/IL-10+ dual positive) and this IL-10+ subset is also found in the CNS. This might suggest that this function at the site of pathology might account for their regulation of disease. On the other hand, despite CXCR3 expression not contributing to preferential CD8 migration to the CNS, CXCR3+ CD8 T cells are still able to robustly ameliorate relapsing demyelinating disease (Fig. 8). This could also suggest that while regulatory CD8 T cells do migrate to the CNS, this may not be an absolute necessity for their regulatory function. CXCR3 is highly expressed by both effector and memory CD8 T cells (29, 36), and is important not only in T cell migration to sites of inflammation but also return to lymphoid tissue for memory formation (26–28, 37). Rather than distinguishing an importance in trafficking, perhaps CXCR3 expression indicates enhanced effector differentiation in regulatory CD8 T cells compared to non-regulatory CD8 T cells (29). However, the studies here only tracked the short-term migration of CD8 T cells into the CNS. It is possible that while non-regulatory P139 CD8 T cells initially traffic at similar frequency to regulatory P178 CD8 T cells, they may not persist in the CNS long-term. Future studies tracking the kinetics of regulatory CD8 T cell migration and persistence in the CNS as well as addressing the absolute requirement of such migration may help us better understand their mechanism.

In previous studies, our group has shown that autoregulatory CD8 T cells are MHC Class Ia-restricted and require the production of IFNγ and perforin (10, 11). This is somewhat distinct from non-myelin autoreactive populations of CD8 Tregs described in other studies. For example, one group showed CD8+CD122+ Treg depletion prolonged EAE symptoms while transfer of these cells was able to ameliorate disease (33, 34, 38) primarily by producing IL-10 (12, 13). In agreement with our previous findings (10, 11, 18), we demonstrate increased production of effector cytokines IFNγ and Granzyme B, as well as increased degranulation marker CD107a expression in the CXCR3+ subpopulation of activated regulatory CD8 T cells (Fig. 3, 4 & 5). In the current study, we also observed that the activated CXCR3+ subpopulation of regulatory CD8 T cells had significant IL-10 production. Regulatory CD8+ IL-10-producing cells expressing CXCR3 have also been observed to have suppressive activity in both mice and humans during homeostasis (39). However, in previous studies we have not observed the dependence of autoregulatory function on IL-10, in that IL-10-deficient CNS-CD8 were able to suppress disease (10). At the same time, IL-10 expression was required in the host, specifically in the dendritic cell population (5). It is therefore possible that IL-10-defiicent CNS-CD8 may be capable of receiving necessary IL-10 signals from their surroundings, whereas in the wildtype situation they produce this IL-10 themselves. In addition, IL-10 production by highly activated CNS-CD8 T cells may serve to minimize their inflammatory effects and immunopathology within the CNS (40). Further studies will be necessary to elucidate the exact role and intercellular dynamics of IL-10 production during EAE and its suppression. Enhancing this CXCR3+/IFNγ+/IL-10+ subset of CNS-CD8 appears to be a promising avenue for a potential immunotherapeutic intervention.

To summarize, here we offer important insights into the fundamental characteristics differentiating regulatory from non-regulatory CD8 T cells in CNS autoimmune demyelinating disease. For the first time, we identify a functionally distinct subpopulation of CXCR3+ CD8 T cells enriched in regulatory P178 CD8 T cells and confirm their robust disease-ameliorating function in vivo. Future studies elucidating the trafficking patterns and mechanism of action of this subpopulation will be critical for future endeavors to enhance the regulatory function of these cells as a potential immunotherapeutic for MS patients.

Key Points:

Autoregulatory CD8 T cells contain a CXCR3+/IL-10+/IFNγ+ subset

CXCR3+ CNS-specific CD8 T cells can suppress EAE

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Sushmita Sinha, Ashutosh Mangalam, Scott Lieberman, and Ali Jabbari, for insightful discussions and critical evaluations of the data presented. We particularly thank Dr. Chakrapani Vemulawada for help with the revised manuscript.

These studies were supported by grants to NJK from the National Institutes of Health (R01AI092106) and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (I01BX003677). AAB and IJJ were supported on NIH training grant T32AI007485. IJJ was also supported by T32AI007511.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Duffy SS, Lees JG, and Moalem-Taylor G. 2014. The contribution of immune and glial cell types in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis international 2014: 285245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compston A, and Coles A. 2002. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 359: 1221–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babbe H, Roers A, Waisman A, Lassmann H, Goebels N, Hohlfeld R, Friese M, Schroder R, Deckert M, Schmidt S, Ravid R, and Rajewsky K. 2000. Clonal expansions of CD8(+) T cells dominate the T cell infiltrate in active multiple sclerosis lesions as shown by micromanipulation and single cell polymerase chain reaction. The Journal of experimental medicine 192: 393–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.York NR, Mendoza JP, Ortega SB, Benagh A, Tyler AF, Firan M, and Karandikar NJ. 2010. Immune regulatory CNS-reactive CD8+T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of autoimmunity 35: 33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kashi VP, Ortega SB, and Karandikar NJ. 2014. Neuroantigen-specific autoregulatory CD8+ T cells inhibit autoimmune demyelination through modulation of dendritic cell function. PloS one 9: e105763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baughman EJ, Mendoza JP, Ortega SB, Ayers CL, Greenberg BM, Frohman EM, and Karandikar NJ. 2011. Neuroantigen-specific CD8+ regulatory T-cell function is deficient during acute exacerbation of multiple sclerosis. Journal of autoimmunity 36: 115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itani FR, Sinha S, Brate AA, Pewe LL, Gibson-Corley KN, Harty JT, and Karandikar NJ. 2017. Suppression of autoimmune demyelinating disease by preferential stimulation of CNS-specific CD8 T cells using Listeria-encoded neuroantigen. Scientific reports 7: 1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortega SB, Kashi VP, Cunnusamy K, Franco J, and Karandikar NJ. 2015. Autoregulatory CD8 T cells depend on cognate antigen recognition and CD4/CD8 myelin determinants. Neurology(R) neuroimmunology & neuroinflammation 2: e170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brate AA, Boyden AW, Itani FR, Pewe LL, Harty JT, and Karandikar NJ. 2019. Therapeutic intervention in relapsing autoimmune demyelinating disease through induction of myelin-specific regulatory CD8 T cell responses. Journal of translational autoimmunity 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortega SB, Kashi VP, Tyler AF, Cunnusamy K, Mendoza JP, and Karandikar NJ. 2013. The disease-ameliorating function of autoregulatory CD8 T cells is mediated by targeting of encephalitogenic CD4 T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of immunology 191: 117–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyden AW, Brate AA, and Karandikar NJ. 2018. Early IFNgamma-Mediated and Late Perforin-Mediated Suppression of Pathogenic CD4 T Cell Responses Are Both Required for Inhibition of Demyelinating Disease by CNS-Specific Autoregulatory CD8 T Cells. Frontiers in immunology 9: 2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinha S, Boyden AW, Itani FR, Crawford MP, and Karandikar NJ. 2015. CD8(+) T-Cells as Immune Regulators of Multiple Sclerosis. Frontiers in immunology 6: 619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinha S, Itani FR, and Karandikar NJ. 2014. Immune regulation of multiple sclerosis by CD8+ T cells. Immunologic research 59: 254–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang H, Canfield SM, Gallagher MP, Jiang HH, Jiang Y, Zheng Z, and Chess L. 2010. HLA-E-restricted regulatory CD8(+) T cells are involved in development and control of human autoimmune type 1 diabetes. The Journal of clinical investigation 120: 3641–3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carvalheiro H, da Silva JA, and Souto-Carneiro MM. 2013. Potential roles for CD8(+) T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmunity reviews 12: 401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brimnes J, Allez M, Dotan I, Shao L, Nakazawa A, and Mayer L. 2005. Defects in CD8+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of immunology 174: 5814–5822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karandikar NJ, Eagar TN, Vanderlugt CL, Bluestone JA, and Miller SD. 2000. CTLA-4 downregulates epitope spreading and mediates remission in relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of neuroimmunology 109: 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyden AW, Brate AA, Stephens LM, and Karandikar NJ. 2020. Immune Autoregulatory CD8 T Cells Require IFN-gamma Responsiveness to Optimally Suppress Central Nervous System Autoimmunity. Journal of immunology 205: 359–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanderlugt CL, and Miller SD. 2002. Epitope spreading in immune-mediated diseases: implications for immunotherapy. Nature reviews. Immunology 2: 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson AC, Nicholson LB, Legge KL, Turchin V, Zaghouani H, and Kuchroo VK. 2000. High frequency of autoreactive myelin proteolipid protein-specific T cells in the periphery of naive mice: mechanisms of selection of the self-reactive repertoire. The Journal of experimental medicine 191: 761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Procaccini C, De Rosa V, Pucino V, Formisano L, and Matarese G. 2015. Animal models of Multiple Sclerosis. European journal of pharmacology 759: 182–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller SD, Karpus WJ, and Davidson TS. 2010. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the mouse. Current protocols in immunology Chapter 15: Unit 15 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson AP, Harp CT, Noronha A, and Miller SD. 2014. The experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of MS: utility for understanding disease pathophysiology and treatment. Handbook of clinical neurology 122: 173–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuchroo VK, and Awasthi A. 2012. Emerging new roles of Th17 cells. European journal of immunology 42: 2211–2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Maaten L, and Hendriks E. 2012. Action unit classification using active appearance models and conditional random fields. Cognitive processing 13 Suppl 2: 507–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sporici R, and Issekutz TB. 2010. CXCR3 blockade inhibits T-cell migration into the CNS during EAE and prevents development of adoptively transferred, but not actively induced, disease. European journal of immunology 40: 2751–2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christensen JE, Nansen A, Moos T, Lu B, Gerard C, Christensen JP, and Thomsen AR. 2004. Efficient T-cell surveillance of the CNS requires expression of the CXC chemokine receptor 3. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 24: 4849–4858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comerford I, Kara EE, McKenzie DR, and McColl SR. 2014. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of autoimmune disorders: focus on chemokines and lymphocyte trafficking. British journal of haematology 164: 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Simone G, Mazza EMC, Cassotta A, Davydov AN, Kuka M, Zanon V, De Paoli F, Scamardella E, Metsger M, Roberto A, Pilipow K, Colombo FS, Tenedini E, Tagliafico E, Gattinoni L, Mavilio D, Peano C, Price DA, Singh SP, Farber JM, Serra V, Cucca F, Ferrari F, Orru V, Fiorillo E, Iannacone M, Chudakov DM, Sallusto F, and Lugli E. 2019. CXCR3 Identifies Human Naive CD8(+) T Cells with Enhanced Effector Differentiation Potential. Journal of immunology 203: 3179–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunnusamy K, Baughman EJ, Franco J, Ortega SB, Sinha S, Chaudhary P, Greenberg BM, Frohman EM, and Karandikar NJ. 2014. Disease exacerbation of multiple sclerosis is characterized by loss of terminally differentiated autoregulatory CD8+ T cells. Clinical immunology 152: 115–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biegler BW, Yan SX, Ortega SB, Tennakoon DK, Racke MK, and Karandikar NJ. 2006. Glatiramer acetate (GA) therapy induces a focused, oligoclonal CD8+ T-cell repertoire in multiple sclerosis. Journal of neuroimmunology 180: 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Najafian N, Chitnis T, Salama AD, Zhu B, Benou C, Yuan X, Clarkson MR, Sayegh MH, and Khoury SJ. 2003. Regulatory functions of CD8+CD28- T cells in an autoimmune disease model. The Journal of clinical investigation 112: 1037–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu P, Bamford RN, and Waldmann TA. 2014. IL-15-dependent CD8+ CD122+ T cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by modulating IL-17 production by CD4+ T cells. European journal of immunology 44: 3330–3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee YH, Ishida Y, Rifa’i M, Shi Z, Isobe K, and Suzuki H. 2008. Essential role of CD8+CD122+ regulatory T cells in the recovery from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of immunology 180: 825–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin MD, and Badovinac VP. 2018. Defining Memory CD8 T Cell. Frontiers in immunology 9: 2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, and Mackay CR. 1998. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in T-cell priming and Th1/Th2-mediated responses. Immunology today 19: 568–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groom JR, Richmond J, Murooka TT, Sorensen EW, Sung JH, Bankert K, von Andrian UH, Moon JJ, Mempel TR, and Luster AD. 2012. CXCR3 chemokine receptor-ligand interactions in the lymph node optimize CD4+ T helper 1 cell differentiation. Immunity 37: 1091–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mangalam AK, Luckey D, Giri S, Smart M, Pease LR, Rodriguez M, and David CS. 2012. Two discreet subsets of CD8 T cells modulate PLP(91–110) induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in HLA-DR3 transgenic mice. Journal of autoimmunity 38: 344–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi Z, Okuno Y, Rifa’i M, Endharti AT, Akane K, Isobe K, and Suzuki H. 2009. Human CD8+CXCR3+ T cells have the same function as murine CD8+CD122+ Treg. European journal of immunology 39: 2106–2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trandem K, Zhao J, Fleming E, and Perlman S. 2011. Highly activated cytotoxic CD8 T cells express protective IL-10 at the peak of coronavirus-induced encephalitis. Journal of immunology 186: 3642–3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]