Abstract

Differential local adaptation restricts gene flow between populations inhabiting distinct environments, resulting in isolation by adaptation. In addition to the statistical inferences of genotype–environment associations, an integrative approach is needed to investigate the effect of local adaptation on population divergence at the ecological, genetic and genomic scale. Here, we combine reciprocal transplant, genome–environment association and QTL mapping to investigate local adaptation in Boechera stricta (Drummond's rockcress). With reciprocal transplant experiment, we found local genetic groups exhibit phenotypic characteristics corresponding to the distinct selection forces from different water availability. At the genetic level, the local allele of a major fitness QTL confers higher and sturdier flowering stalks, maximizing the fecundity fitness component under sufficient water supply, and its genetic variation is associated with precipitation across the landscape. At the genomewide scale, we further showed that multiple loci associated with precipitation are highly differentiated between genetic groups, suggesting that local adaptation has a widespread effect on reducing gene flow. This study provides one of the few comprehensive examples demonstrating how local adaptation facilitates population divergence at the trait, gene and genome level.

Keywords: local adaptation, reciprocal transplant, Boechera stricta, population genomics, landscape mapping

1. Introduction

Heterogenous environments impose distinct selection forces on organisms and may result in local adaptation, causing local populations to perform better in their native environments than foreign populations do [1–4]. The reduction of gene flow between such populations facilitates genetic differentiation, resulting in ‘isolation by adaptation’ [5,6] in addition to the neutral patterns of ‘isolation by distance’. Most studies have employed statistical tests for the contribution of environmental factors on genetic variation after accounting for neutral forces [7–10]. With the ease of genome re-sequencing, recent studies have employed the same logic to identify genetic variants associated with local environments [11–17], further expanding the breadth and depth of the genomic investigation of local adaptation. However, in addition to showing the patterns of gene–environment association (‘isolation by environment’ [9]), one has to integrate phenotypic and genetic studies both in the field and controlled environments to fully understand ‘isolation by adaptation’, the process during which local adaptation decreases gene flow and facilitates divergence [18,19].

Association-based studies must be supported by experimental works (figure 1). At the organismal level, one has to demonstrate local adaptation and identify the environmental factors causing differential local adaptation between populations (‘key environmental factors’ hereafter [5]), the types of natural selection in distinct environments, as well as the divergence of quantitative traits responding to these selection forces [20–22]. After establishing the ecological connections among organism, environment, and trait, one could further strengthen the connections by incorporating genetic mapping for loci associated with both fitness and traits in the field [11,17]. Further, one should be able to observe that genetic variation of the major QTL is associated with the key environmental factors across the landscape. At the genomic level, instead of focusing on a few candidate loci, one should demonstrate that most loci associated with the key environment (but not loci associated with other environmental factors) are highly diverged between genetic groups, consistent with the expectation that local adaptation to a key environmental factor promotes divergence of genomewide adaptive loci rather than a few major-effect genes.

Figure 1.

A three-way approach for investigating the genomic architecture of local adaptation. On the ecology side (orange), niche analysis first identifies differences in the niche spaces of genetically differentiated groups and the crucial environmental factors. Different environments result in distinct types of natural selection, and one can further identify important traits under selection. Genetic mapping (blue) then identifies major quantitative trait loci (QTL) controlling traits under selection. Landscape genomics (green) directly identifies loci associated with environmental factors under the assumption that wild species are locally adapted to their collection sites. In this study, we used all these approaches to study the genomic architecture of local adaptation in Boechera stricta. (Online version in colour.)

While several large-scale genetic mapping studies have been conducted, for example, between Sweden and Italy [23] and between Germany and Spain [24] for Arabidopsis thaliana, and between Montana and Colorado USA for Boechera stricta [25–27], they employed parental accessions and experimental gardens spanning large geographical areas, differing in many environmental factors. In order to specifically address isolation by adaptation, we advocate focusing on the admixture zone between genetic groups. With isolation by adaptation, reduced fitness of immigrants or hybrids causes genetic differentiation, and the counteracting forces of selection and migration within an admixture zone allows the identification of key environmental factors and loci. By contrast, the comparison between distant populations has the risk of incorporating factors not directly associated with isolation by adaptation.

Boechera stricta is an ecological model plant, occupying diverse and relatively undisturbed habitats in North America [28]. Previous studies separated this species first into east and west genetic groups, and the east group was further divided into north and south groups [5,20]. Recently, the south group was further separated based on population genome resequencing [29], resulting in a total of four genetic groups, WES, NOR, UTA and COL. While WES and the other groups diverged at about 179 K years ago [29], currently an admixture zone between WES and NOR exists in Idaho, USA. Lee & Mitchell-Olds [5] first showed that the divergence between WES and the eastern groups involves isolation by environment (especially factors related with soil water content), while evidence for isolation by distance was identified among the eastern groups (between NOR, COL and UTA). Consistent with the predicted direction of niche divergence, NOR accessions have rapid phenology, typical for drought escape, as well as more succulent leaves [20]. The connections among distinct environments, types of natural selection, organismal phenotypes, the underlying loci, as well as the patterns of adaptive genetic variation across the landscape, have yet to be made.

In this study, we profiled the genomic architecture of local adaptation by connecting these essential factors (figure 1). With field experiments, we first established the connection among distinct field environments, the respective selection agents and the target traits under selection. Genomic investigation supported our hypothesis that adaptation to the key environmental factor is associated with high divergence. Multiple genetic mapping experiments were then conducted to identify loci associated with fitness in the field, potentially adaptive traits and environments across the landscape.

2. Material and methods

(a). Species distribution modelling

We first performed niche modelling separately for the NOR and WES groups to investigate the finer-scale niche separation within their contact zone. Using the genetic and location information of accessions in Wang et al. [29], we extracted all bioclimatic variables in an area ranging from longitude −117.5 to −112 and latitude 43–46.6 in 30 arc-second resolution (average for 1960–1990) [30]. Highly correlated bioclimatic variables were removed (correlation > 0.8), resulting in 10 bioclimatic variables in this study: annual mean temperature (BIO1), mean diurnal range (BIO2), isothermality (BIO3), temperature seasonality (BIO4), mean temperature of wettest quarter (BIO8), mean temperature of driest quarter (BIO9), annual precipitation (BIO12), precipitation of driest month (BIO14), precipitation seasonality (BIO15), precipitation of warmest quarter (BIO18). We estimated species distributions using MaxEnt [31] separately for the NOR and WES groups. All parameters were as default except three modifications for optimization: regularization multiplier was 3, maximum iterations were 5000 and cross-validation was 10 runs. In addition, we calculated Schoener's D to assess the niche overlap between populations using the R package ecospat [32,33].

(b). Population genetics analyses

To investigate which among the 10 aforementioned environmental factors are associated with local adaptation between NOR and WES at the genomic scale, we first used SNP–environment association analyses to detect loci associated with environmental adaptation, followed by comparing the between-population FST of candidate SNPs and genomic background. Genome resequencing data were downloaded from NCBI SRA (all the SRA numbers were requested from Wang et al. [29] with additional SRA number SRR396758 for LTM accession), including 98 NOR and 57 WES accessions (electronic supplementary material, table S1). The reads were mapped to the reference genome v 1.2 [34] with bwa after adapter trimming and quality check [35]. SNPs were called following GATK Best Practices [36]. We filtered out sites with missing data proportion more than 0.1, resulting in about 420 K SNPs. Latent factor mixed models (LFMM) were used to identify SNPs associated with environmental adaptation with the R package LEA [37].

The divergence of candidate SNPs between NOR and WES groups were estimated following and modifying a recent method that took into account local linkage disequilibrium (LD) and allele frequency [38]. We used PLINK 1.9 to perform SNP LD-pruning, extracting SNPs with r2 < 0.8 through 50-SNP sliding window and within 1 Mb [39]. A total of 36 K SNPs were kept after these filtering steps. To control for allele frequency, SNPs were allocated into 20 bins of allele frequency, and separately for each environmental factor, we assigned the top 0.1% SNPs with the highest LFMM scores to each bin according to their allele frequency. In each bin, we randomly sampled the same number of genome-wide SNPs (including the top SNPs) as the top SNPs and calculated median FST of these background SNPs. The random sampling was repeated 1000 times to obtain a distribution of FST representing genomic background divergence.

(c). Test of local adaptation

We performed reciprocal transplants to investigate the patterns of local adaptation of the NOR and WES genetic groups in their native environments: Jackass Meadow (JAM, 44.966317 N, 114.085350 W, 2646 m altitude) and Alder Creek (ALD, 44.790833 N, 114.251967 W, 1980 m), where local accessions belong to the NOR and WES groups, respectively. A total of 24 accessions (12 NOR and 12 WES; electronic supplementary material, tables S2–S3) were used. A randomized complete block (RCB) design with 12 blocks in each garden was employed, with blocks containing two individuals from each accession. Each block therefore had 48 plants, with 576 plants transplanted to each garden. Boechera stricta is a naturally self-fertilizing species, and we further self-fertilized each accession in the greenhouse for at least two generations with single seed descent to minimize maternal effects. Due to the high seedling-stage mortality and the remoteness of the field sites, direct seeding in the field results in a low final sample size. Following all previous field experiments in this species [25,26,40], plants were grown in greenhouse to 10-weeks old during summer and then transplanted to the field in the autumn of 2010, allowing plants to undergo vernalization in natural environments. In the summer of 2011, plant stages were recorded every 7–10 days through the entire growing season and coded as: rosette (R), bolting (B), flower-only (FO), flower-silique stage 1 (FS1, more flowers than fruits), flower-silique stage 2 (FS2, more fruits than flowers) and siliques-only (SO). We also recorded fruit number and silique length while available.

Boechera stricta is a short-lived perennial species; plants that survived for two years in the field gardens had small rosettes with very low reproductive output. We therefore used only the first year of data to represent the reproductive output in this study. We decomposed the reproductive output with the following: whether an individual survived after winter (survival rate), whether it bolted during the growing season (bolting rate), and its fecundity if it flowered (number of fruits and number of seeds per fruit). The bolting rate was used as a fitness component since it signifies whether a plant went through the transition from vegetative to reproductive stages, and a low bolting rate suggests a mismatch between plant genotype and transplantation environments in terms of the cues to initiate bolting or an overall unsuitable environment limiting plant size. Ideally, fecundity should be quantified as the total seed number of an individual, which is difficult to characterize in the field. We therefore used the longest silique length of a plant as an approximation for seed number per fruit, since the longest silique is most likely fully matured. Silique length and seed number are highly correlated [41]. Therefore, fecundity of a reproductive individual is the product of its fruit number and longest silique length, while fecundity of a non-fruiting individual is recorded as missing. Meanwhile, reproductive output of a fruiting individual is the same as its fecundity, but reproductive output of a non-fruiting individual is zero.

To confirm the correlation between seed number and silique length again, we performed an independent experiment using six repeats of 48 accessions in the greenhouse (electronic supplementary material, table S4–S5), with each repeat containing two siliques.

We used linear mixed models to test for local adaptation between the NOR and WES groups. Reproductive output and fitness components were the response variables; the fixed effects included genetic group, garden and their interaction, and accession was treated as a random effect nested within group. Survival and bolting rate were transformed by the natural log of the odds ratio. We used the R package lme4 for these calculations [42].

(d). F3 population

We prepared a F3 mapping population derived from two parents in the admixture zone: one from Parker Meadow (Parker, NOR genetic group, 44.61667 N, 114.51670 W) and the other from Ruby Creek (Ruby, WES genetic group, 45.55000 N, 113.76670 W). The F1 was self-fertilized to produce F2 plants, and subsequent generations were propagated by single-seed descent to create 153 F3 families. In all experiments, the traits of multiple F4 progenies of the same F3 family were measured to obtain the mean trait values of each F3 family. The details of Genotyping-by-Sequencing, genotype calling and linkage map construction are described in Lee et al. [34]. In brief, reduced-representation sequencing was performed and reads aligned to the B. stricta v. 1.2 genome [34]. The genotype of each 100 kb window in each family was called via estimating the proportion of reads with either parental alleles. Using each 100 kb window as a marker, the linkage map was constructed with MSTmap [43].

(e). Phenotyping the F3 population

In addition to the field transplantation of natural accessions, we performed a reciprocal transplant experiment of the F3 population also in the NOR (JAM) and WES (ALD) gardens to map loci associated with fitness components in the field. Multiple F4 progeny of each F3 family were planted in a RCB design with six blocks, with each block containing one plant from each family. Transplantation was performed in the autumn of 2011 and traits including survival, bolting, fruit number, silique length, and the width and height of flowering stalks were surveyed during the 2012 growing season (electronic supplementary material, tables S6–S8). We also measured the rate of change among sequential plant stages (transition speed): the plant stages of R, B, FO, FS1, FS2, SO were transformed to 1–6, and the slope of linear regression (regressing numeric plant stages onto days) estimates the transition speed per day from one stage to the next.

We performed the same experiment in the greenhouse with three blocks for leaf and rosette morphology as in Lee & Mitchell-Olds [20] (leaf area measurement requires sacrificing individuals), and nine blocks for fecundity, phenology and stalk morphology (electronic supplementary material, tables S8–S10). Leaf and rosette morphology were measured when plants were 11 weeks old. When plants were 12 weeks old, they were vernalized in 4°C for six weeks and then returned to the same greenhouse condition. All traits were measured as described in [20].

(f). Contribution of fitness components

We used a multiple regression framework to estimate the relative contribution of distinct fitness components to overall reproductive output in the NOR and WES environments. Mean fitness component values of each F3 family were used instead of individual measurements to avoid biases from the micro-environment each individual inhabits [44]. Theoretically, reproductive output is equal to the continued multiplication of fitness components. Thus, the log-transformed reproductive output is a linear combination of these log-transformed fitness components, allowing the use of a standard multiple regression framework to estimate the proportional contribution of each fitness component to reproductive output. For the least-square mean trait values, we first added a constant to each trait so that the minimum value of each trait is one. After natural log transformation, the minimum value of each trait is zero. Within each garden, reproductive output was used as the response variable, while survival rate, bolting rate, fruit number of fruited plants, and the length of the longest silique were the predictor variables. The R2 from each predictor variable was used as the proportional contribution to reproductive output.

(g). QTL mapping of the F3 population

The genetic map from Lee et al. [34] was used in QTL mapping. In brief, we used family LSMEANS of all traits and fitness components measured in both field environments and the greenhouse. We used the ‘scanone’ and ‘fitqtl’ functions to fit a multiple-QTL model by Haley–Knott regression [45] in the R/qtl package [46], and continued drop-one-term analysis until no more QTL were identified. We used α = 0.05 and 1000 permutations to determine the significance threshold. The confidence interval of QTL was estimated by the ‘bayesint’ function.

(h). Selection coefficients

For the F3 population in the field, we calculated the selection coefficient (s) for each marker [25]. For each fitness component, the LSMEAN of each family was first calculated for each marker genotype as absolute fitness. Let w11, w12 and w22 be the relative fitness of the NOR homozygotes, heterozygotes and WES homozygotes, respectively; fij refers to frequency of the ijth genotype; the population mean fitness is defined as . Hence, [25]. Positive values indicate that selection favoured NOR genotypes and negative indicates that selection favoured WES genotypes. One thousand permutations between genotype and fitness were performed to obtain a null distribution for computing p-values.

(i). Association between fitness QTL and natural environments

After identifying the QTL affecting major life-history components, we investigated whether genetic variation at each QTL is associated with environmental factors across the landscape. We first obtained all 100 kb windows covered by the 1-LOD confidence interval of a QTL as its physical extent. We performed multiple regression analyses comparing the full model Env ∼ QTL.PC1 + QTL.PC2 + QTL.PC3 + GEM.PC1 + GEM.PC2 + GEM.PC3 with the reduced model Env ∼ GEM.PC1 + GEM.PC2 + GEM.PC3, where Env is one of the ten bioclimatic variables, QTL.PC1 to QTL.PC3 are the first three principal components from SNPs within the QTL, and GEM.PC1 to GEM.PC3 are the first three principal components from genomewide SNPs. A significant improvement of the full over the reduced model represents a significant association of genetic variation at that QTL with environment after controlling for neutral factors.

3. Results

(a). Isolation by environment in boechera stricta

Using more samples, we first investigated whether the NOR and WES genetic groups inhabit divergent environments, as previously concluded (figure 2) [5,20]. Indeed, environmental niche modelling predicts distinct suitable regions for the two groups (electronic supplementary material, figure S1) even within this small contact zone, with the niche similarity index Schoener's D at 0.28 (0 represents no niche overlap and 1 represents identical niche space) [32]. However, the two groups differ in mean annual temperature (p < 0.001) but not significantly for annual precipitation (p = 0.336, electronic supplementary material, table S11). While this seems contradictory to previous conclusions that water availability is important, we note this is mainly due to the differences in elevation: in addition to local precipitation, lower-elevation regions receive part of the precipitation from high-elevation as water runoff, but not vice versa. Controlling for topographical factors is therefore important. Precipitation is significantly higher in WES than NOR habitats (p < 0.001, electronic supplementary material, table S12) after controlling for elevation.

Figure 2.

The collection sites (a, yellow for WES, blue for NOR) and typical habitats of WES (b) and NOR (c) genetic groups of Boechera stricta in the admixture zone. In panel a, squares are the locations of the reciprocal transplant gardens; triangles are for parents of the F3 population; crosses are for 24 wild accessions. In the admixture zone, WES accessions mostly inhabit low-elevation riparian regions (b) while NOR accessions occupy high-elevation mountain slopes (c). (Online version in colour.)

(b). Patterns of local adaptation

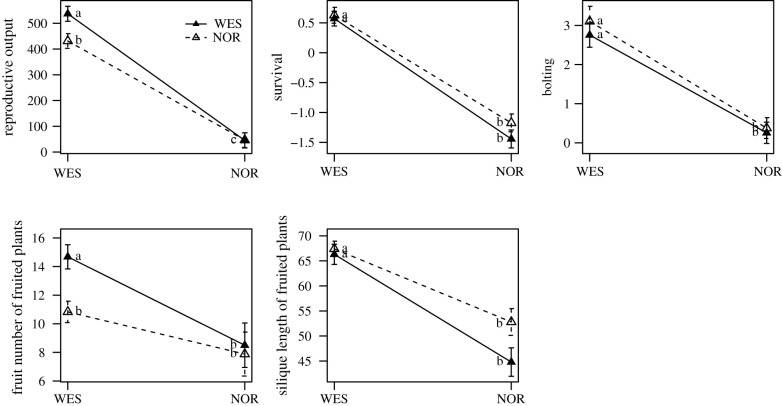

To examine if the NOR and WES groups were locally adapted to their native environments, we prepared a reciprocal transplant experiment between NOR and WES environments (electronic supplementary material, table S3). We partitioned the reproductive output of individuals into four fitness components: survival rate, bolting rate, fruit number of fruited plants and seed number of the longest silique of fruited plants. We used silique length as an approximation for seed number since they are highly correlated (Pearson's correlation coefficient r = 0.80, p-value < 0.001; electronic supplementary material, table S5). Overall, we observed a strong pattern of local adaptation in the WES environment, where local accessions had higher reproductive output, mainly caused by their higher fruit number (figure 3; electronic supplementary material, table S13). On the other hand, all fitness components in the NOR environment are much lower than in the WES environment (figure 3; electronic supplementary material, table S13), reflecting the overall harsh conditions at high-elevation NOR sites. Local NOR accessions appeared to have slightly higher survival rate and silique length, although not statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Reproductive output and fitness components of NOR and WES accessions in reciprocal transplant experiments. The open and solid triangles indicate the NOR and WES genetic groups, respectively. The lower-case letters refer to significance levels from Tukey's HSD test.

We performed another experiment to estimate the importance of each fitness component to reproductive output in these environments. Instead of focusing on natural accessions, we used the F3 population from the cross between NOR and WES parents, using recombination in this cross to break potential LD among loci controlling these fitness components. The proportional contribution of the fecundity component (the combined effect of fruit number and silique length of reproductive plants) to overall fitness is large (about 77% in NOR and 73% in WES gardens; table 1). Survival rate appears to be more important for fitness in the NOR than the WES environment, while bolting rate (proportion of plants that bolted) exhibits the opposite pattern. However, we cannot conclude that fruit number is the most important factor in both environments, as its heritability in the NOR environment is zero (table 1). Since local adaptation results from the synergistic effects of selection pressure and organismal genotypes, a heritability of zero implies no genetic control of this fitness component and therefore no local adaptation, despite its importance to reproductive output at the phenotypic level. After taking contribution and heritability of each fitness component into account, our results suggest survival and bolting rate to be important in NOR, while bolting rate and fecundity are important factors for local adaptation in the WES environment.

Table 1.

The contribution of each fitness component to reproductive output estimated from family means of the F3 cross.a

| traitb | NOR garden |

WES garden |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| variation explained (%) | heritability | variation explained (%) | heritability | |

| survival rate | 14.85 | 0.09 | 3.83 | 0.00 |

| bolting rate | 2.67 | 0.18 | 16.61 | 0.67 |

| fecundity: fruit number of fruited plants | 59.28 | 0.00 | 56.95 | 0.06 |

| fecundity: silique length of fruited plants | 17.26 | 0.01 | 16.41 | 0.15 |

aReproductive output was defined as fruit number multiplies silique length, approximating the total seed produced and individuals that did not survive or flower had a value of zero.

bFor the two fecundity fitness components, individuals that did not survive or flower were denoted as missing data.

(c). QTL of fitness components and related traits

We used the same F3 population to locate QTL influencing fitness components and related traits in both natural environments and the greenhouse (electronic supplementary material, tables S8 and S14). In brief, a bolting proportion QTL in ALD (the WES garden) was mapped on chromosome 7 with the NOR allele having a higher bolting rate (figure 4a). A fecundity-related QTL in ALD was located on chromosome 5, and the WES allele showed higher fecundity (figure 4a). Fecundity-related QTL in the greenhouse, including fruit number, fecundity, mature fruit number and silique length, were located on chromosome 1, 2 and 7 (figure 4a). While the fecundity QTL in the greenhouse overlap those of flowering time in the greenhouse and ALD, they do not overlap any fitness-related QTL in the field. Finally, no significant QTL were detected in the JAM garden likely due to the high initial mortality and therefore low sample size.

Figure 4.

Effects of markers across the B. stricta genome on (a) quantitative traits and (b) selection coefficients. Each row refers to a trait (a) or fitness component (b); each column refers to a marker and is ordered by genetic position (from left to right). Chromosomes were separated by vertical black lines. (a) QTL mapping results. The blue and red bars indicate that the significant markers have higher trait values for the NOR and WES genotypes, respectively. The light blue and pink segments represent confidence intervals. (b) For each marker, blue represents that NOR genotype was favoured by natural selection, and red for WES. Dark colours represent significant selection coefficients over genomewide permutation at the significance threshold α = 0.001. Light colours indicate those at α = 0.05. (Online version in colour.)

To investigate which genomic regions were under selection in the field, we calculated the selection coefficient of fitness components for every 100 kb window in the genome. A total of 481 windows (about 48%) showed significant selection coefficients in one environment but not in the other (figure 4b). The genomic region under strongest selection during our experiment was for fecundity in the ALD garden at 73 cM on chromosome 5 (figure 4b), where the local allele conferred longer silique length and more fruits. While it was expected that traits under selection would have QTL co-localizing with a fitness QTL, we did not see strong overlap between this fecundity QTL and those of other traits in the greenhouse, except rosette number (figure 4). In addition to the genotype-by-environment interactions making QTL in the field not necessarily detected in the greenhouse, such lack of QTL overlap might also be caused by our stringent genome-wide QTL significance threshold. Among the F3 families, those homozygous for the NOR or WES genotypes in this QTL differed significantly in silique length and several stalk-related traits in ALD, especially stalk width, main stalk height, and stalk height with branch (the upper part of stalk with flowers) (electronic supplementary material, table S15). Indeed, the peak of this fecundity QTL co-localizes with the sharp peaks of these stalk traits, which are slightly below our QTL significance threshold (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). In these traits, the ALD genotype of this QTL confers longer silique as well as higher and wider stalks (electronic supplementary material, table S15), consistent with the higher fecundity. Higher stalks allow more flowers and fruits, and sturdier stalks sustain higher reproductive output without collapsing under high fruit or seed weight. Finally, the peak for rosette number in the greenhouse is quite broad and the highest point does not co-localize with our fecundity QTL, and we therefore exclude this trait from further discussion (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

(d). Association between fitness QTL and natural environments

We showed that the WES habitat, with sufficient water supply, imposed fecundity selection on local accessions and might select for the allele producing sturdy flowering stalks, maximizing reproductive output. We further examined the association between genetic variation at this QTL and environmental factors across the landscape while controlling for genomic background. Indeed, natural genetic variation at this QTL had the strongest association with precipitation of the driest month (BIO14, p = 0.02; electronic supplementary material, table S16) and weaker associations with mean temperature of the wettest quarter (BIO8, p = 0.07) and annual precipitation (BIO12, p = 0.07). After controlling for elevation, precipitation of the driest month remained significant (p = 0.018). The conclusion remained the same when we used more (five) genomic PCA axes as background control (p < 0.001).

(e). Genomewide effects of isolation by adaptation

After establishing the link among local environments, selection forces, traits, and major-effect QTL, we aimed to investigate the effect of local adaptation on divergence in the genomic scale. We searched for SNPs associated with environmental factors within the NOR–WES admixture zone and investigated their magnitude of between-group divergence. We observed higher FST for top candidate SNPs than the genomic background for precipitation of the driest month (BIO14), and other factors including annual mean temperature (BIO1) and temperature seasonality (BIO4) (electronic supplementary material, figure S3). Candidate SNPs of other bioclimatic variables showed FST no higher than genomic background, implying that although adaptation to these environmental factors might have a genetic basis, the top candidate polymorphisms did not contribute to NOR–WES local adaptation since they mostly segregated within genetic groups (electronic supplementary material, figure S3).

4. Discussion

While the statistical association between genetic variation and environmental differences was often used to demonstrate effects of local adaptation on population divergence, statistical patterns of isolation by environment [9] could also be generated by factors such as sexual selection against immigrants or biased dispersal [9]. Here using Boechera stricta as model, we focused on isolation by adaptation [18,19], the process during which local adaptation to distinct environments facilitates divergence in the ecological, genetic and genomic scale. We provided one of the few comprehensive examples connecting key concepts of local adaptation (figure 1) that were often investigated in separate studies.

From an ecological viewpoint, distinct local environments can impose divergent selection favouring contrasting phenotypic characteristics. One therefore expects highly differentiated habitats and traits between genetic groups, as shown in our previous [5,20] and present studies. Here, we further performed empirical field experiments demonstrating that contrasting environments impose distinct types of selection, favouring trait divergence: the fecundity fitness component is important in WES habitats which have greater water availability, where local WES accessions have higher and sturdier flowering stalks, more rapid rosette growth and less-conservative water usage, resulting in higher reproductive output. By contrast, the survival fitness component is important in the drier NOR habitats, with local NOR accessions possessing more succulent leaves. In contrast to research systems where the key environmental factors, selection forces and traits for isolation by adaptation could only be inferred [47–49], our empirical field experiments demonstrate how environmental differences facilitate trait divergence due to ecological factors, a much-needed approach to validate isolation by environment [9]. Similar examples exist not only in plants. For example, in the insect Timema cristinae, predation load on distinct host plants requires host-specific crypsis, resulting in widespread phenotypic and genetic divergence of ecotypes on different host plants [50].

After establishing the connection among environments, fitness components and traits, we took a genetic approach, testing whether a major QTL is associated with these crucial components. As we have shown, in the mesic WES environment a major fecundity QTL is associated with stalk morphology, a trait previous identified to have higher QST than FST [20]. The local WES allele produces higher and sturdier flowering stalks, resulting in higher fecundity, and the genetic variation of this QTL is associated with precipitation-related factors across the landscape. In the JAM garden, however, we did not observe a strong QTL for leaf and rosette morphology, another set of potentially locally adaptive traits with high QST [20]. Due to the high seedling mortality in the field and the remoteness of our field sites, in order to have sufficient samples to assess reproductive output, plants were reared to rosettes in the greenhouse to ensure transplant success. We hypothesize that the survival fitness component from seed to rosette, which is logistically difficult to measure in this study, might be important in the JAM garden and associated with the leaf- and rosette-related traits.

The combination of biparental genetic mapping and large-scale reciprocal transplant experiments has been performed in several systems. For example, Prasad et al. [27] investigated Boechera stricta between Montana and Colorado (more than 1000 km apart), and Ågren et al. [23] studied Arabidopsis thaliana between Italy and Sweden (more than 2000 km apart). As we emphasized, however, such experimental design could not appropriately address the question of isolation by adaptation, where natural selection in local environments, not geographical distance, acts as the antagonistic forces against gene flow. In addition, large-scale transplantation and GWAS studies have been conducted in several species [24,51], which also focused on adaptation to environments in the continental scale but not distinct habitats in vicinity. By contrast, the parents and gardens in our study are located within 50 km in the same admixture zone (figure 2a). While transplantation experiments have been conducted also in a smaller spatial scale in Boechera stricta [41,52], these studies focused on natural variation within the same genetic group and therefore did not address how differential local adaptation prevents gene flow between spatially nearby populations inhabiting distinct niches. Our experimental design therefore specifically captures the geographical, environmental and genetic scales suitable for investigating isolation by adaptation in nature. Our design and conclusion mirror a series of studies in the coastal perennial and inland annual groups of Mimulus guttatus. Inhabiting Californian coastal regions, the two genetically diverged groups differentiate in several ecologically important traits, and reciprocal transplants in geographically adjacent but environmentally distinct habitats identified soil moisture and flowering time as the most important selective agents and traits [53,54]. Similarly, follow-up genetic mapping identified a major-effect QTL (chromosomal inversion) contributing to the reproductive isolation of these groups [55].

While large fitness effects exist for only a few major QTL, we further investigated the effect of potential environmental adaptation on the divergence of multiple loci. By investigating levels of between-population differentiation in multiple candidate loci for specific traits, previous studies used this method to identify traits under divergent selection in human [38] and plants [56]. With similar logic, rather than reporting a list of environmentally associated loci, here we investigate which environmental factors are associated with genome-wide loci that are highly divergent between genetic groups. On the other hand, if adaptive genetic variation for an environment mainly segregates within rather than between genetic groups, such environment would not act as the main factor limiting gene flow. With this analysis, we confirm the importance of precipitation in driving isolation by adaptation in our system.

5. Conclusion

In addition to the statistical association between genetic variation and environmental differences, here we emphasize the importance of investigating the effect of local adaptation on genetic differentiation from multiple perspectives. At the organismal level, we identified a key environmental factor (water availability), distinct types of selection forces, as well as candidate traits driving differential local adaptation. At the genetic level, the most important QTL for field fitness affects traits maximizing reproductive output in one water regime, and genetic variation at this QTL is associated with water availability across the landscape. Finally at the genomic level, we showed that many SNPs associated with water availability are highly differentiated between genetic groups, suggesting that adaptation to distinct water regimes facilitated divergence of many loci across the genome, in addition to the major-effect QTL. Using Boechera stricta as model, our previous and present studies together provide a comprehensive case of isolation by adaptation and demonstrate the influence of local adaptation on population differentiation in the phenotypic, genetic and genomic scale.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for comments. We thank Jill Anderson, Rob Colautti, Michael Ellis, Rose Keith, Marshall McMunn, Sara Mitchell-Olds, Tim Park, Katharine Putney, Evan Raskin, Catherine Rushworth, Hui-Ju Tsai, Maggie Wagner, Ash Zemenick and Kathryn Springer-Ghattas for assistance of field and greenhouse experiments. We also thank Willie and Connie Heald, Dick Finlayson and the Salmon-Challis National Forest for providing logistic support and field experiment sites. We are grateful to the support from National Taiwan University's Computer and Information Networking Center for high-performance computing facilities.

Ethics

Permits were obtained from United States Forest Service Regions 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6, as well as Grand Canyon, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon National Parks.

Data accessibility

All plant phenotype data and codes are available in electronic supplementary material, tables.

Authors' contribution

C.-R.L. and T.M.-O. designed the study and performed the field experiments with help from the field crew. C.-R.L. performed greenhouse and molecular biology experiments and revised the manuscript. C.-R.L. and Y.-P.L. analysed the data. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by grants to T.M.-O. (US National Science Foundation, grant no. EF-0723447) and C.-R.L. (Duke Biology Grant-in-Aid, SigmaXi, US National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement, grant no. 1110445, and Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology, grant no. 108-2636-B-002-004).

References

- 1.Kawecki TJ, Ebert D. 2004. Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecol. Lett. 7, 1225-1241. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell-Olds T, Willis JH, Goldstein DB. 2007. Which evolutionary processes influence natural genetic variation for phenotypic traits? Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 845-856. ( 10.1038/nrg2207) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colautti RI, Lee CR, Mitchell-Olds T. 2012. Origin, fate, and architecture of ecologically relevant genetic variation. Curr. Opin Plant Biol. 15, 199-204. ( 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.01.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savolainen O, Lascoux M, Merilä J. 2013. Ecological genomics of local adaptation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 807-820. ( 10.1038/nrg3522) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee CR, Mitchell-Olds T. 2011. Quantifying effects of environmental and geographical factors on patterns of genetic differentiation. Mol. Ecol. 20, 4631-4642. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05310.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin Y-P, Lu C-Y, Lee C-R. 2020. The climatic association of population divergence and future extinction risk of Solanum pimpinellifolium. AoB Plants 12, 1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hämälä T, Mattila TM, Savolainen O. 2018. Local adaptation and ecological differentiation under selection, migration, and drift in Arabidopsis lyrata. Evolution 72, 1373-1386. ( 10.1111/evo.13502) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Böndel KB, Lainer H, Nosenko T, Mboup M, Tellier A, Stephan W. 2015. North-south colonization associated with local adaptation of the wild tomato species Solanum chilense. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 2932-2943. ( 10.1093/molbev/msv166) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang IJ, Bradburd GS. 2014. Isolation by environment. Mol. Ecol. 23, 5649-5662. ( 10.1111/mec.12938) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edelaar P, Alonso D, Lagerveld S, Senar JC, Björklund M. 2012. Population differentiation and restricted gene flow in Spanish crossbills: not isolation-by-distance but isolation-by-ecology. J. Evol. Biol. 25, 417-430. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02443.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier-Level A, Korte A, Cooper MD, Nordborg M, Schmitt J, Wilczek AM. 2011. A map of local adaptation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 334, 86-89. ( 10.1126/science.1209271) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang Z, Gonzales AM, Clegg MT, Smith KP, Muehlbauer GJ, Steffenson BJ, Morrell PL. 2014. Two genomic regions contribute disproportionately to geographic differentiation in wild barley. G3 Genes, Genomes, Genet. 4, 1193-1203. ( 10.1534/g3.114.010561) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoder JB, Stanton-Geddes J, Zhou P, Briskine R, Young ND, Tiffin P. 2014. Genomic signature of adaptation to climate in Medicago truncatula. Genetics 196, 1263-1275. ( 10.1534/genetics.113.159319) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abebe TD, Naz AA, Léon J. 2015. Landscape genomics reveal signatures of local adaptation in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Front Plant Sci. 6, 813. ( 10.3389/fpls.2015.00813) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ariani A, Mier Teran JCB, Gepts P. 2018. Spatial and temporal scales of range expansion in wild Phaseolus vulgaris. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 119-131. ( 10.1093/molbev/msx273) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahony CR, MacLachlan IR, Lind BM, Yoder JB, Wang T, Aitken SN. 2020. Evaluating genomic data for management of local adaptation in a changing climate: a lodgepole pine case study. Evol Appl. 13, 116-131. ( 10.1111/eva.12871) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah N, et al. 2020. Extreme genetic signatures of local adaptation during Lotus japonicus colonization of Japan. Nat. Commun. 11, 1-15. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-14213-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nosil P, Vines TH, Funk DJ. 2005. Perspective: Reproductive isolation caused by natural selection against immigrants from divergent habitats. Evolution 59, 705-719. (doi: 10.1554/04-428) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orsini L, Vanoverbeke J, Swillen I, Mergeay J, De Meester L. 2013. Drivers of population genetic differentiation in the wild: isolation by dispersal limitation, isolation by adaptation and isolation by colonization. Mol. Ecol. 22, 5983-5999. ( 10.1111/mec.12561) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee CR, Mitchell-Olds T. 2013. Complex trait divergence contributes to environmental niche differentiation in ecological speciation of Boechera stricta. Mol. Ecol. 22, 2204-2217. ( 10.1111/mec.12250) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leinonen T, McCairns RJS, O'Hara RB, Merilä J. 2013. QST –FST comparisons: evolutionary and ecological insights from genomic heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 179-190. ( 10.1038/nrg3395) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Josephs EB, Berg JJ, Ross-Ibarra J, Coop G. 2019. Detecting adaptive differentiation in structured populations with genomic data and common gardens. Genetics 211, 989-1004. ( 10.1534/genetics.118.301786) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ågren J, Oakley CG, McKay JK, Lovell JT, Schemske DW. 2013. Genetic mapping of adaptation reveals fitness tradeoffs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 21 077-21 082. ( 10.1073/pnas.1316773110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Exposito-Alonso M, 500 Genomes Field Experiment Team, Burbano HA, Bossdorf O, Nielsen R, Weigel D. 2019. Natural selection on the Arabidopsis thaliana genome in present and future climates. Nature 573, 126-129. ( 10.1038/s41586-019-1520-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson JT, Lee CR, Mitchell-Olds T. 2014. Strong selection genome-wide enhances fitness trade-offs across environments and episodes of selection. Evolution 68, 16-31. ( 10.1111/evo.12259) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson JT, Lee CR, Rushworth CA, Colautti RI, Mitchell-Olds T. 2013. Genetic trade-offs and conditional neutrality contribute to local adaptation. Mol. Ecol. 22, 699-708. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05522.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasad KVSK, et al. 2012. A gain-of-function polymorphism controlling complex traits and fitness in nature. Science 337, 1081-1084. ( 10.1126/science.1221636) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rushworth CA, Song BH, Lee CR, Mitchell-Olds T. 2011. Boechera, a model system for ecological genomics. Mol. Ecol. 20, 4843-4857. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05340.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang B, et al. 2019. Ancient polymorphisms contribute to genome-wide variation by long-term balancing selection and divergent sorting in Boechera stricta. Genome Biol. 20, 1-15. ( 10.1186/s13059-018-1612-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A. 2005. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1965-1978. ( 10.1002/joc.1276) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips SJ, Dudía M. 2008. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 31, 161-175. ( 10.1111/j.0906-7590.2008.5203.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoener TW. 1968. The Anolis lizards of bimini: resource partitioning in a complex fauna. Ecology 49, 704-726. ( 10.2307/1935534) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Broennimann O, Cola V Di, Guisan A. 2018. ecospat: spatial ecology miscellaneous methods. See https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ecospat.

- 34.Lee CR, et al. 2017. Young inversion with multiple linked QTLs under selection in a hybrid zone. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 119. ( 10.1038/s41559-017-0119) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754-1760. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Depristo MA, et al. 2011. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 43, 491-501. ( 10.1038/ng.806) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frichot E, François O. 2015. LEA: An R package for landscape and ecological association studies. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6, 925-929. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.12382) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo J, Wu Y, Zhu Z, Zheng Z, Trzaskowski M, Zeng J, Robinson MR, Visscher PM, Yang J. 2018. Global genetic differentiation of complex traits shaped by natural selection in humans. Nat. Commun. 9, 1-9. ( 10.1038/s41467-017-02088-w) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaunt TR, Rodríguez S, Day INM. 2007. Cubic exact solutions for the estimation of pairwise haplotype frequencies: implications for linkage disequilibrium analyses and a web tool ‘CubeX’. BMC Bioinf. 8, 1-9. ( 10.1186/1471-2105-8-428) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson JT, Lee CR, Mitchell-Olds T. 2011. Life-history qtls and natural selection on flowering time in Boechera stricta, a perennial relative of arabidopsis. Evolution 65, 771-787. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01175.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wadgymar SM, Daws SC, Anderson JT. 2017. Integrating viability and fecundity selection to illuminate the adaptive nature of genetic clines. Evol. Lett. 1, 26-39. ( 10.1002/evl3.3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bates D, Machler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1-48. ( 10.18637/jss.v067.i01) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Y, Bhat PR, Close TJ, Lonardi S. 2008. Efficient and accurate construction of genetic linkage maps from the minimum spanning tree of a graph. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000212. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000212) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rausher MD. 1992. The measurement of selection on quantitative traits: biases due to environmental covariances between traits and fitness. Evolution 46, 616-626. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1992.tb02070.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haley CS, Knott SA. 1992. A simple regression method for mapping quantitative trait loci in line crosses using flanking markers. Heredity 69, 315-324. ( 10.1038/hdy.1992.131) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Broman KW, Wu H, Sen S, Churchill GA. 2003. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics 19, 889-890. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg112) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moreira LR, Hernandez-Baños BE, Smith BT. 2020. Spatial predictors of genomic and phenotypic variation differ in a lowland Middle American bird (Icterus gularis). Mol. Ecol. 29, 3085-3102. ( 10.1111/mec.15536) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manthey JD, Moyle RG. 2015. Isolation by environment in white-breasted nuthatches (Sitta carolinensis) of the Madrean Archipelago sky islands: a landscape genomics approach. Mol. Ecol. 24, 3628-3638. ( 10.1111/mec.13258) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bond MH, Crane PA, Larson WA, Quinn TP. 2014. Is isolation by adaptation driving genetic divergence among proximate Dolly Varden char populations? Ecol Evol. 4, 2515-2532. ( 10.1002/ece3.1113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nosil P. 2007. Divergent host plant adaptation and reproductive isolation between ecotypes of Timema cristinae walking sticks. Am. Nat. 169, 151-162. ( 10.1086/510634) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lovell JT, et al. 2021. Genomic mechanisms of climate adaptation in polyploid bioenergy switchgrass. Nature 590, 438-444. ( 10.1038/s41586-020-03127-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keith RA, Mitchell-Olds T. 2019. Antagonistic selection and pleiotropy constrain the evolution of plant chemical defenses. Evolution 73, 947-960. ( 10.1111/evo.13728) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hall MC, Willis JH. 2006. Divergent selection on flowering time contributes to local adaptation in Mimulus guttatus populations. Evolution 60, 2466. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01882.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lowry DB, Rockwood RC, Willis JH. 2008. Ecological reproductive isolation of coast and inland races of Mimulus guttatus. Evolution 62, 2196-2214. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00457.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lowry DB, Willis JH. 2010. A widespread chromosomal inversion polymorphism contributes to a major life-history transition, local adaptation, and reproductive isolation. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000500. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000500) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsumura H, et al. 2020. Long-read bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) genome and the genomic architecture of domestication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 14 543-14 551. ( 10.1073/pnas.1921016117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All plant phenotype data and codes are available in electronic supplementary material, tables.