Abstract

While speech and language do not fossilize, they still leave traces that can be extracted and interpreted. Here, we suggest that the shape of the hard structures of the vocal tract may also allow inferences about the speech of long-gone humans. These build on recent experimental and modelling studies, showing that there is extensive variation between individuals in the precise shape of the vocal tract, and that this variation affects speech and language. In particular, we show that detailed anatomical information concerning two components of the vocal tract (the lower jaw and the hard palate) can be extracted and digitized from the osteological remains of three historical populations from The Netherlands, and can be used to conduct three-dimensional biomechanical simulations of vowel production. We could recover the signatures of inter-individual variation between these vowels, in acoustics and articulation. While ‘proof-of-concept’, this study suggests that older and less well-preserved remains could be used to draw inferences about historic and prehistoric languages. Moreover, it forces us to clarify the meaning and use of the uniformitarian principle in linguistics, and to consider the wider context of language use, including the anatomy, physiology and cognition of the speakers.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Reconstructing prehistoric languages’.

Keywords: vocal tract, phonetics, osteology, language change

1. Introduction

Obviously, the dead cannot speak: we cannot listen to Shakespeare reading A Midsummer Night's Dream, we cannot elicit verb conjugations from Cicero, and we cannot even get Tutankhamun to say ‘aaah’ … The furthest we could get—which is incontestably a tour de force—was to CT-scan the mummified body of an Egyptian scribe and priest, Nesyamun, from about 3000 years ago, print a three-dimensional reconstruction of his vocal tract, and produce a creepy sounding [æ:::] [1]. That, and the various attempts to simulate Neanderthal vowels based on debatable reconstructions and assumptions, leading to endless debates about their capacity (or lack thereof) to articulate the ‘full modern’ vowel space, with a particular focus on [u] [2–6]. While we are far from a general consensus, language and speech go back at least to the origins of modern humans a few hundred thousands of years ago [7,8] but, most probably (given recent evidence), at least to the last common ancestor of modern humans and our closest evolutionary relatives, the Neanderthals and the Denisovans, about half a million years ago [9,10].

But our limits in what concerns the speech and language of long-gone people run deeper than this: there seems to a widespread assumption in linguistics that, on the one hand, there are precious few traces left by speech and language (writing goes back not more than a few thousand years) and, on the other, living (and attested) languages are very poor at retaining information about their earlier stages. Taken together, these seem to impose a ‘time horizon’ beyond which we cannot really know much [11], a time horizon that is usually placed at most 10 000 years ago, and rooted in the breakdown of the ‘standard’ historical linguistic comparative method of information recovery and inference ([12–15]; see also [16]). This breakdown results in the reluctance to connect established language families into larger (and, presumably, deeper) constructs such as ‘Nostratic’ [17,18], ‘Eurasiatic’ [19] or ‘Altaic’/’Transeurasian’ [20,21]. While this reluctance is clearly justified [11,17,22] by the daunting methodological and data availability issues, which make it very hard to distinguish biases and a priori stances from actual inferences from the data, it also makes it very hard to study these issues.

Nevertheless, there are intriguing hints that language might not be as bad at retaining information after all, especially when combined with external sources of evidence, such as (ancient) genetics [23–25] and archaeology [26], but accessing it requires the development and application of new methods, cross-disciplinary collaborations and, most importantly, the willingness to accept that false positives will inevitably be generated, but that the scientific process will weed (most of) them out. In this context, it is interesting to note that quantitative methods borrowed from evolutionary biology (especially Bayesian phylogenetics) have not only helped refine the internal structure of established language families (such as Indo-European, Austronesian, Uralic or Pama-Nyungan), but also, especially combined with external evidence, suggested ideas about their origins and spread [27–30], pushing the boundaries to 5000–8000 years ago. The same class of methods, however, has been used to explore even ‘deeper’ connections between languages, producing exciting but highly controversial results. Some of these results include: the apparent support for something akin to Eurasiatic (about 15 000 years ago) from phylogenetic methods applied to cognacy judgments [31] and to the alignments of actual Automated Similarity Judgment Program (ASJP; [32]) transcriptions [33]; the proposed Bayesian phylogenetic evidence for Transeurasian [20]; the very indirect finding that the stability of structural features of language might conserve continent-wide deep signals of shared ancestry and/or contact, suggesting connections between the language families of the Americas and north-eastern Eurasia going back approximately 15 000 years or so [34]; and, the bold claim that phonological systems might retain a signal of the modern human expansion from Africa some tens of thousands of years ago [35,36]. However, besides being currently unclear how reliable these findings are [22,37,38], they only push our knowledge back but a sliver of the half million years or so of human speech and language [9,10], and remain, in general, fairly abstract and ‘high level’. Can we do better?

Here we suggest that we might be able to infer fairly concrete information about past phonetics and phonologies, going back as far as the fossil record of the Neanderthals and other ‘archaic humans’ (half a million—or even more—years ago). To do so, we will use the links between aspects of the vocal tract anatomy, and the articulation and acoustics of speech which are uncovered by recent investigations into the patterns of inter-individual variation in the anatomy of the speech organs. Besides allowing us to make informed guesses about Neanderthals lacking labiodentals and the persistence of clicks in sub-equatorial Africa, this approach also questions the indiscriminate application of a strong uniformitarian principle to speech and language, arguing instead for a much more nuanced inferential framework that takes into account the wider context of language, which includes, among others, the physical environment and human biology [39,40].

2. Variation everywhere

Due to space constraints and the specific focus of this paper, we will only briefly summarize here points discussed at length in other publications (e.g. [39–41]). Recent advances in several scientific fields (including medicine, human genetics, anthropology and psychology), the availability of large computer-readable databases, the democratization of computing power, data analysis and statistics, and wider changes in how society at large, and science in particular, sees variation, have allowed a renewed interest in understanding how people vary, how this inter-individual variation is patterned, and how it relates to universal characteristics. What we realize is that, on a massive foundation of sharedness, individuals vary in subtle ways at all levels of study: from the molecular [42,43], to the anatomical and physiological [44], and to the psychological and cognitive [45]. This variation is mostly small and quantitative, and results in a wide range of ‘normality’ that grades into the ‘pathological’—here we are interested in this normal range of variation, which is not distributed at random between individuals, but is intricately patterned. Thus, on the one hand, any given individual belongs to multiple (overlapping or nested) groups, and groups differ in myriad continuous, statistical and multivariate ways (as opposed to ‘crisp’, deterministic, categorical differences driven by one or a few characteristics, as usually claimed by racist ideologies). This patterning is rooted in our complex but relatively recent evolutionary and demographic history [46–48]: while we are much more uniform than other species (for example, there is less genetic diversity in the 8 billion people spread across the world than in a few hundred highly geographically circumscribed chimpanzees; [49]), we do vary, with most of this variation distributed between individuals (approx. 80%), and not between groups either within (approx. 10%) or between continents (approx. 10%) [46,50]. Yet, this variation is informative enough (especially when aggregated among many genetic loci and characteristics) to recover individual origins, geographic patterns of human dispersals and migrations, and past demographic events [48,51]. This variation decreases with distance from Africa, is distributed as continuous and overlapping gradients across many variables, with very few (if any) sharp boundaries—often referred to as ‘clinal variation’ [46,47,52]. Clinal variation underscores the unity of humankind, and a proper understanding of its patterns and processes represents one of the most powerful scientific arguments against racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination [48,53–56].

Language in general, and the vocal tract in particular, are far from being exceptions, despite decades of focusing on (absolute) universals and denying, or, at best, dismissing and trivializing variation as mere irrelevant ‘noise’ to be removed from the analysis and ignored from theorizing. Of course, this was not a blanket stance, with aspects of variation being actively studied in, for example, dialectology [57], sociolinguistics [58] and phonetics [59–64], but it did result in the marginalization of such inquiries and limited the appreciation of how widespread variation is, and of how powerful an explanatory factor it may be [39,41]. However, focusing on phonetics and phonology alone, the last two decades have witnessed the accumulation of data concerning the type and patterns of inter-individual variation in the production and perception of speech, as well as a heightened interest in the theoretical implications for phonology, sound change and typological diversity [41,65].

Of particular interest here is variation in the anatomy of the vocal tract structures, especially in those structures that (i) have a higher chance of preservation in the osteological and fossil record, or (ii) whose particularities can be inferred from ancient DNA, and their effects on phonetics and phonology. While our understanding of the genetic and developmental underpinnings of the vocal tract is still in its infancy, being primarily based on pathologies with a genetic component (see, for example, the information available in OMIM, https://omim.org/), there are several candidate genes and mechanisms known, especially concerning the teeth [66,67] and the hard palate [68,69], but also the skull and the face in general (see, for example, FaceBase; https://www.facebase.org/). These sources of information are rich enough to even allow some inferences about the evolution of the position of the larynx and the structure of the face from methylation patterns in ancient DNA extracted from archaic human fossils [70]. However, we are far from being able to reliably reconstruct the details of normal variation in vocal tract anatomy from the (epi)genetic variants ascertained from the remains of a given individual, which means that, at least for now, we should focus instead on the osteological and fossil record, which has the advantage that the relevant anatomical details are sometimes preserved well enough, but is affected by the twin disadvantages of very small (and geographically and historically skewed) sample sizes, and the lack of soft tissue preservation (with a few notable exceptions involving special taphonomic conditions such as anaerobic bogs, permafrost or ice; [71,72]). It is also important to recognize the potential influence of environmental factors on the physiology and anatomy of the vocal tract. The desiccation of the vocal folds, and its subsequent phonatory consequences, in environments with low air humidity [73,74] is an example of the first type, while the sexually dimorphic and geographically patterned variation in the nasal cavity [75–77], which seems partly explained by the need to warm and humidify the in-breathed air in cold and dry climates [76,78–80], with possible consequences for nasalization, is an example of the second type.

Before discussing the type of vocal tract data that can be recovered from this record, and the kind of inferences for speech and language that can be made, we briefly review a few studies linking variation in details of vocal tract anatomy to phonetics and phonology using a multitude of methodologies, including experimental designs with living people, computational modelling and phylogenetic inferences.

3. From details of the vocal tract to phonetic and phonological diversity

To begin, there are well-known claims that the position of the larynx within the throat can be inferred from traces in the archaeological record, most notably the shape of the base of the cranium and characteristics of the hyoid bone, and that this positioning might allow us to say something about the capacity of ancient humans to produce (or not) the full modern vowel space [2,3,5,6,9]. However, despite claims to the contrary [81,82], it is far from clear how reliable such reconstructions are (even when adding inferences from ancient epigenomes; [70]), but, more importantly, it is not obvious what articulatory, acoustic and linguistic effects different positions of the larynx would have. The original claims [6] that Neanderthals had a much higher larynx than modern humans and that this precluded them from producing the full spectrum of vowels found in the currently spoken languages, did not age well. Newer models of speech articulation seem to suggest that the vowel space produced with a higher larynx is not terribly limited thanks to active compensation by the other articulators [2–4], that the rest position of the larynx is not very relevant given its wide dynamic range [83,84], and that the Neanderthal hyoid bone was, in fact, anatomically and biomechanically extremely similar to the modern human one [85]. Finally, despite the importance of the peripheral vowels, and the fact that actual speech productions are spread across the potential (acoustic and articulatory) vowel space relatively independently of the described phonological system of the language, few modern languages use the full extent of this potential space to convey phonological distinctions.

As we will detail below, the hard structures of the vocal tract have by far the highest chances of preservation in the osteological and fossil record, suggesting that we should focus on the hard palate, the jaw and the teeth. There is tremendous inter-individual morphological variation in all these structures, and some aspects of this variation are patterned, in a continuous, statistical and multivariate manner, also between groups [39,41]. We will briefly review a few studies, using a variety of methods and data, showing how normal variation in these structures affects speech.

There are experimental indications that the midsagittal shape of the hard palate—between ‘domed’ and ‘flat’—influences token-to-token variability, with speakers with ‘flatter’ palates showing less articulatory variability [61,86]. Computer models combining a realistic geometric model of the vocal tract (VocalTractLab 2.1; https://www.vocaltractlab.de/; [87]) controlled by a neural network, which repeatedly learns and transmits vowels across multiple generations [88], show that details of the midsagittal shape of the hard palate, as quantified using Bézier curves [89], do affect the articulation and acoustic properties of vowels. Importantly, the acoustic effects survive the active compensation by the free articulators (the tongue, jaw and lips) and, despite being very weak in any particular generation, are amplified by repeated learning across generations, to the level of the acoustic variation observed within actual languages [88].

Zooming in on a specific substructure of the hard palate, the alveolar ridge (a shelf-like structure behind the upper incisors), biomechanical models using ArtiSynth [90] show that its shape and size affect the effort required for the articulation of click consonants as well as their acoustic properties [91]. Specifically, the alveolar ridge shape that is statistically most often found among the native speakers of ‘click languages’ in southern Africa (i.e. a ‘small’ or ‘absent’ alveolar ridge) seems to reduce the effort needed and may simultaneously enhance the acoustics of clicks. There is also experimental evidence from a large, ethnically diverse sample, using structural, sustained articulation and real-time magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), complemented with intra-oral optical three-dimensional scans and acoustic recordings [41], showing that the strategy used to articulate the North American English ‘r’ is influenced by the anatomy of the anterior vocal tract, including the hard palate, the alveolar ridge and the lower jaw. While practically indistinguishable from an acoustic point of view, these different articulations nevertheless influence the articulation and acoustics of other neighbouring sounds [92,93], thus potentially influencing sound change.

The last study to be mentioned here [94] combines biomechanical modelling, large-scale cross-linguistic statistical analyses, detailed case studies, and Bayesian phylogenetic analyses of the Indo-European family. It shows that the type of bite (‘overjet’/’overbite’ versus ‘edge-to-edge’) most common in a population influences the probability that the language(s) spoken by that population will have labiodental sounds (such as ‘f’ and ‘v’) in their sound system. Importantly for us here, the type of bite is strongly influenced by post-developmental factors, especially the diet, with hunter-gatherer populations predominantly showing an ‘edge-to-edge’ bite, while those practicing agriculture predominantly having ‘overjet’/’overbite’ [94]. This influence is mediated by at least two processes having to do with the mechanical properties of food: tougher foods promote tooth erosion and movement [95–97], but also affect the growth of the lower jaw [98].

Taken together (see [39,41] for more comprehensive reviews and discussions), these studies suggest that (a) there is extensive normal inter-individual and, in some cases, even between-group variation in the hard structures of the vocal tract (e.g. hard palate, teeth, lower jaw); (b) this variation is mostly continuous, statistical and gradient in nature, but it (c) sometimes does influence the articulation and/or the acoustics of speech sounds, producing (d) (usually very) weak effects at the individual level (so-called ‘biases’) that nevertheless can be (e) amplified by the repeated use and transmission of language to result in unmistakable differences between dialects and languages in their phonetics and phonology. While this causal chain is very complex, influenced by many other factors (e.g. linguistic, cultural, historical, demographic, environmental) and composed of individually subtle links, it does seem to work, at least in some cases. This raises the hope that we may be able to infer something about past languages by combining such findings with information about vocal tract structures preserved in the osteological and fossil record—to which we now turn.

4. Aspects of the vocal tract that can be recovered from the osteological and fossil record

In what concerns the osteological and fossil traces of speech and language, a lot of attention has been given to the hyoid bone, the ear structures housed in the temporal bone, the openings in bones through which nerves can pass (i.e. foramina, canals), and to endocasts (fossilized brain traces). To date, we have fossilized hyoids from australopithecines [99], Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals ([85,100,101]; the finding originally identified as a Homo erectus hyoid [102] has been reinterpreted as a fragment of a vertebra [103]), and it seems that, while the Australopithecus hyoid is clearly different from the modern human one, the Neanderthal and pre-Neanderthal ones are very similar to our own [9,104]. The shape of the ear structures can be reconstructed using computed tomography (CT) scans, and ear ossicles are sometimes directly preserved [105–108], allowing inferences about the audition of long-gone humans: from these, it seems that, functionally, the hearing of Neanderthals was very similar to that of modern humans and clearly different from that of chimpanzees [9,10]. Unfortunately, brain endocasts [109,110] and the size of the hypoglossal canal [111,112] seem to currently offer rather limited and unclear evidence concerning speech and language.

However, the evidence briefly reviewed above seems to suggest that we might want to also focus on other components of the vocal tract, particularly on those with a bony component, increasing their chances of surviving the taphonomic processes. Evidence suggests that while the hard palate is a rather fragile structure, it is often quite complete when the cranium is not too fragmented, while the lower jaw survives rather well [113,114]. In fact, in order to test the feasibility of extracting information about the hard palate and the lower jaw from osteological remains, in 2015–2016 we conducted an exploratory study of well-understood collections of historic human skeletons (coming from different cemeteries). The overarching goals were to (a) digitize the structures of interest in order to (b) compare the historical samples to each other and with a modern sample, so that we can (c) ascertain the feasibility of the methods, (d) draw conclusions about temporal changes in vocal tract anatomy and, possibly, (e) their effects on speech and language. The project was a collaboration between D Dediu and SR Moisik (then at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, The Netherlands) and AL Waters-Rist, WA Baetsen and AM Bosman (then at the Laboratory for Human Osteoarchaeology, Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University, also in The Netherlands), as part of the larger G[ɜ]bils (Genetic biases in language and speech) project, funded by The Dutch Research Council (NWO). Following a careful assessment, considering data availability, quality, sample size and meta-information, we decided to use one contemporary and three historical samples, all collected in The Netherlands (figure 1): Alkmaar (1484–1574 CE), Klaaskinderkerke (thirteenth to sixteenth centuries CE), Middenbeemster (1829–1866 CE), and part of the contemporary ArtiVarK sample (2014–2015).

Figure 1.

The map of The Netherlands showing the locations of the four samples (yellow triangles) as well as the location of Amsterdam (red diamond) for orientation. ArtiVarK is shown as located in Nijmegen. Map generated using QGIS, version 3.10.3-A Coruña.

Alkmaar (Paardenmarkt) is the oldest sample; it was part of a monastic cemetery in present-day Alkmaar in Noord Holland, in use between 1484 and 1574 CE. Klaaskinderkerke is a cemetery belonging to a verdronken dorp (lit. ‘drowned village’, or ‘sunken village’) on the island of Schouwen-Duiveland in the province of Zeeland, the remains there dating between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries CE. Middenbeemster is a Protestant church cemetery in Noord Holland, located on a polder (or reclaimed lake), the Beemster, the first in The Netherlands to be dried by building dykes and pumping out the water using windmills; the remains are firmly dated between 1829 and 1866 CE. For more information about these historical samples, see previous work [115–117]. Finally, the ArtiVarK sample was collected between 2014 and 2015 in Nijmegen, and contains, of relevance here (see [41] for details), structural MRI and intra-oral three-dimensional optical scans of approximately 90 participants; for this study we used a subset of 34 (16 male; 18 female) contemporary Dutch individuals coming from across the whole country. See electronic supplementary material, table S1 for the list of included individuals.

For the hard palate (see [115] for details), we included 22 individuals from the Klaaskinderkerke sample (6 male, 11 probable male, and 5 probable female; 2 young adults, 6 young-middle adults, 10 middle and 4 middle-old adults—see below for details about the age categories), and 38 individuals from the Middenbeemster sample (17 male, 2 probable male, 3 probable female and 16 female; 22 young adults and 16 middle adults). For the lower jaw (see [116] for details), we included 37 individuals from the Alkmaar sample (6 male, 8 probable male, 5 female and 18 probable female; 20 young adults and 17 middle adults), and 51 individuals from the Middenbeemster sample (18 male, 10 probable male, 11 female and 12 probable female; 31 young adults and 20 middle adults). Note that the estimation of sex and age-at-death from osteological remains are methodologically complex, often difficult to perform due to damage resulting from taphonomy, and their results must be taken as broad probability estimates [118–120]. Therefore, we decided to split our individuals (all adults) into two broad groups: ‘young adults' (roughly 18–35 years old at death) and ‘middle adults’ (roughly 36–60 years old at death); note that the age ranges for the Klaaskinderkerke sample carry a greater uncertainty than the other collections, because of a general lack of postcranial remains. Likewise, we assign sex with certainty (male or female) whenever possible, but we also classified some individuals as ‘probably’ of one sex or the other. Note that, for the Klaaskinderkerke sample, a second, independent assignment of sex agrees with our own for all specimens except one (not used in the simulations conducted here).

The data acquisition and processing protocol was similar for the two structures: following a general osteological analysis, meta-data registration, and the application of various inclusion and exclusion criteria (good or excellent preservation, completeness, adult age, the absence of severe pathologies and abnormalities, and the absence of periodontal disease and ante-mortem tooth loss), the selected individuals were assessed for sex and their age-at-death was estimated. Next, the relevant structures were digitized using a NextEngine™ 3D Desktop Scanner Ultra HD 2020i (NextEngine, Inc., Santa Monica, CA), which is widely used in physical anthropology, palaeoanthropology and other fields. This device allows the acquisition of high-quality, high-resolution three-dimensional models of solid objects using multiple laser beams (for details, see [115,116]). This resulted in a set of three-dimensional meshes (post-processed in ScanStudio™ and MeshLab; [121]), one per individual and structure, on which landmarks (fixed, anatomically clearly defined features that are homologous between individuals) and semilandmarks (or ‘sliding landmarks’, i.e. a set of variable or ‘mobile’ points used to discretize a curve) were placed using Landmark Editor [122]: there are 27 landmarks for the lower jaw in the historical samples, 6 in the contemporaneous ArtiVarK sample (a subset of the 27, due to differing methodologies), and 44 for the hard palate (see electronic supplementary material, tables S2–S5 for a full list including the sliding semilandmarks; [115], tables 8 and 9, and figure 31 and [117], tables 2 and 3 for details; and electronic supplementary material, figure S8 for their placement). These allowed us to quantitatively compare the samples and individuals using classic and geometric morphometric [123] methods which allow the principled separation of variation in shape from variation in size.

In a nutshell (see [115] for full details), for the shape of the hard palate we found that our samples showed a large overlap: the variation within both samples is greater than that between them. This is to be expected, since the populations were not significantly separated temporally, geographically or linguistically (Middle Dutch versus modern Dutch; see [115,124–127]). The small amount of variation we found is best characterized by subtle differences in the height and shape (‘U’-shaped versus ‘V’-shaped) of the maxillary dental arch, as well as the flexion of the basicranial angle, the relative width of the nasal aperture and the degree of orthognathy. The only significant difference in average shape was found between the male group from Klaaskinderkerke and the female group from Middenbeemster. Size differences were found to be statistically significant between the two samples, with Klaaskinderkerke being slightly larger than Middenbeemster. The causes for these differences probably stem from developments during the respective periods when these people lived, ranging from climatic (temperatures during the Little Ice Age) to sociocultural (Industrial Revolution). For the lower jaw (see [116,117] for details), we found that differences between the two historic samples (Alkmaar and Middenbeemster) were dominated by size, with the male individuals from the older site (Alkmaar) having the largest mandibles on average, and the female individuals from Middenbeemster having the smallest mandibles. Moreover, the magnitude of sexual dimorphism seems to differ between the two sites, with a lower amount of sexual dimorphism present in the Alkmaar sample. The results are possibly linked to a softening of the diet that occurred between these time periods, although confounding factors such as sampling bias, life history, and shared population history could not be accurately accounted for.

There are several methods of palaeodietary reconstruction: while the faunal and floral remains at an archaeological site indicate the available foods, the analysis of various aspects of human bones and teeth indicate what people actually ate. The stable isotope ratios in bones and teeth paint a broad picture of the types of plants (C3 versus C4 photosynthetic pathway) and animals (herbivores versus carnivores, marine versus terrestrial) that were consumed [128], while dental calculus often contains masticated food debris, plant microfossils, protein biomolecules, and plant and animal DNA [129,130]. Such research has been successfully applied to both recent and ancient remains, including Neandertals and early modern humans [131,132], and may provide information about dietary variables that affect vocal tract anatomy. The macro- and microscopic analysis of dental wear can be useful for inferring how ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ the diet was [133,134]. Several of these methods have been applied to the three historical samples used here [135–137], but more research and better data integration are needed before we can study if (and how) dietary differences might have affected vocal tract anatomy. With the currently available data, it seems there were no major differences in dietary ‘softness’ among the archaeological populations, nor the modern ArtiVarK sample, suggesting that all groups had diets requiring broadly similar masticatory forces (but we cannot rule out that this is an artifact of the poor landmark coverage in the modern sample), concordant to the historical peasant staples of wheat or rye bread, dairy products (cheese, butter and milk), root vegetables, with smaller amounts of fish, and even more so, meat.

While still preliminary, these findings do show that (i) we can recover and quantitatively analyse data pertaining to the vocal tract from relatively old human remains, and (ii) that there are quantifiable differences between individuals, locations and historical periods that may be relevant for speech.

5. Getting the past to ‘speak’: simulating the articulation of vowels using medieval hard palates

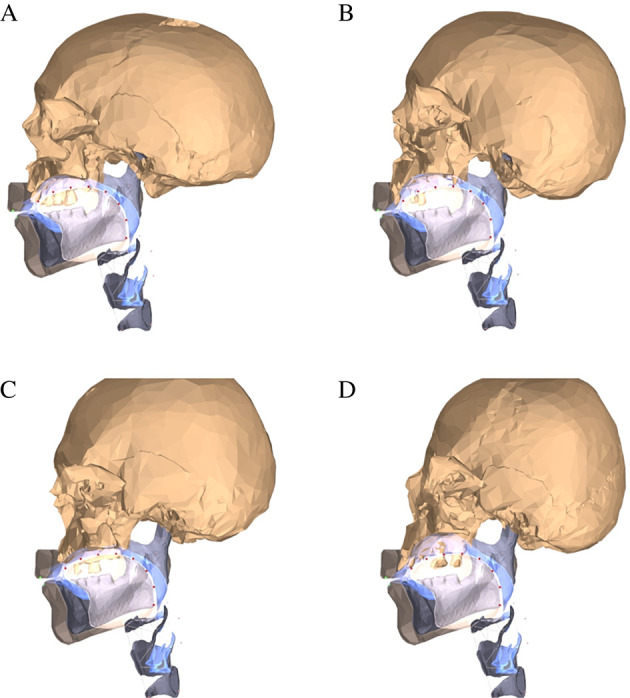

Here we push this research programme an inch further, by making a subset of medieval hard palate samples ‘speak’. More precisely (figure 2; full details about the methods and results are available in the electronic supplementary materials ‘Modelling the biomechanics and acoustics of reconstructed vocal tracts: methods and full results', figures S1–S7 and Videos), we selected four individuals (two males, one probable male, one probable female; one young-middle adult, two middle adults, one middle-old adult) for which very complete skeletal geometry is available, and we used a biomechanical model of the vocal tract (ArtiSynth; [90]) to reconstruct, as accurately as possible, the way these individuals would have articulated the six vowels [i] (as in the North American English ‘heat’), [e] (as in ‘hate’), [æ] (as in ‘hat’), [ɑ] (as in ‘hot’), [o] (as in ‘hotel’) and [u] (as in ‘hoot’; figure 2; electronic supplementary material, figure S2 and Videos). What we found is that there are differences in the acoustics of the vowels between these individuals (electronic supplementary material, figures S4–S7), some of them rather dramatic (one case being that the vowel [e] of one individual is acoustically close to the [i] of the others). While our models are rather simplistic and, crucially, do not implement articulatory compensation or acoustic-auditory-based targeting, the differences we found are real in the sense that they would exist in the speech output of these individuals if they could maintain exactly the same articulatory structure and posture (given their individual hard palate and dentition); they are components of our organic voice quality [138,139]. Thus, the individuals must overcome these potential acoustic differences in their speech, through articulatory compensation, in order to achieve reasonably well the intended auditory vowel targets or risk being misunderstood.

Figure 2.

Midsagittal views (from the left) of the four reconstructed vocal tracts (identified as A–D; see the electronic supplementary materials for details). The airways are shown in blue, the associated skull samples are in beige and the large capital black letters are the samples. Sample access granted by the Stichting Cultureel Erfgoed Zeeland. Digitized image dissemination for educational purposes only. Crania models created by author W.A.B.; for access to the actual three-dimensional models of the crania, contact author W.A.B. (Online version in colour.)

Our own previous work [88], using a different type of model of the vocal tract that does allow for articulatory compensation of differences in the midsagittal shape of the hard palate through the use of the free articulators (mainly the tongue, the lips and the lower jaw), shows that even if this compensation is highly effective, it nevertheless fails to completely erase the acoustic ‘signature’ of inter-individual anatomical variation. This ‘attenuated’ acoustic signature is very small but present and, perhaps surprisingly, is sometimes amplified by the repeated use and transmission of language in populations composed of individuals with a similar anatomy [39,88,91].

All in all, we hope to have shown that (i) information about vocal tract structures can be successfully extracted from the remains of long-gone people, (ii) that it can be used in qualitative, quantitative and modelling investigations into (iii) the patterning of inter-individual (and, possibly, inter-group) variation with (iv) consequences for speech and language.

6. Discussion and conclusion

While the aforementioned data have only ‘scratched the surface’, we do hope to have shown that there is huge potential in such an approach, which uses traces of vocal tract anatomy from past people, combined with results from computer models and experiments in contemporaneous individuals, to make informed inferences about long-gone languages. What we have tried to show here concretely is that there is a wealth of information about specific ‘hard’ components of the vocal tract (the lower jaw and the hard palate) in the osteological record, that this information can be extracted and quantified in a rigorous manner, and that it can be used not only to compare individuals and groups across time, but also to simulate how these would have affected the production of vowels. Naturally, these first steps can be extended in time, space and linguistic coverage.

Temporally, we have focused here on relatively recent historical populations from well-understood contexts (medieval and post-medieval northwestern Europe) for pragmatic (reliable contextual information, good preservation, access to digitization technology, osteological expertise) and theoretical reasons (controversies about sexing using the lower jaw, changes in food and nutrition, sound changes in the history of Dutch). But our experience clearly suggests that this can be extended back in time for as far as there are well-preserved components of the vocal tract in the fossil record, emphatically preceding the emergence of anatomically modern humans a few hundred thousand years ago [140].

Geographically, there is nothing special about northwestern Europe besides the fact that it is historically rather well understood and archeologically intensively studied, but as more work is conducted in other regions, as more osteological and fossil data become available, either physically (in museums and collections) or digitally (as three-dimensional optical or CT scans), and as the various non-scientific hurdles related to accessing these data diminish, this type of investigation can be used to shed light on regional or larger-scale developments.

Finally, we are guilty of producing yet another study of vowel production here (although we do provide the formants F1 to F5 and the spectra up to 5000 Hz), but this can be extended to other speech sounds and vocal tract structures as well. Just to cite a few possibilities, one could investigate the alveolar ridge and its effects on click consonants [91,141], hard palate shape and ‘r’ [41], dentition/bite and labiodentals [94], or larynx position and, indeed, vowels [4].

Putting these extensions together, we could suggest studies that would, for example, look at the osteological and fossil record of sub-Saharan Africa preceding the relatively recent Bantu expansion [142,143], focusing on the alveolar ridge and aiming to understand the time-depth and geographical extensions of ‘click languages’. More precisely, while currently there are but a few languages that integrate click consonants in their phonological inventories, mostly in southern and eastern Africa (and some Bantu languages that have borrowed clicks), there are intriguing suggestions that they are but remnants of a once widespread use of phonemic clicks [144–146]. If the alveolar ridge shape and size indeed bias the articulation and acoustics of clicks [91,141], then we might be able to infer if past populations were biased in such a way as to favour phonological clicks or not. (Incidentally, we could apply the same inferences to the existing pygmy groups: while their pre-Bantu languages are lost, they may very well have used phonemic clicks as well.)

Another example might even transgress the origins of modern humans and try to infer features of Neanderthal speech: if the negative effects of the edge-to-edge bite on labiodentals inferred for recent hunter-gatherers [94] also hold deeper in time, we can infer that pre-12 000 years ago modern humans, archaic humans, Neanderthals (and even H. erectus) probably did not use ‘f’ and ‘v’ that much [147]. Likewise, we might use the shape of the Neanderthal hard palate to infer something about the vowels that their languages might have used, or even how they might have articulated their ‘r’s.

But we also need to know more about the type and patterning of variation in vocal tract anatomy, physiology and control in present-day humans, and its effects on speech and language, before we can generate informed hypotheses about the past. The work we presented here, concerning the hard palate [41,88], the alveolar ridge [91], and the bite [94], are (we hope) just the beginning of a vast research programme. Other directions could concern the curvature of the cervical spine and pitch [148,149], or the anatomy of the nasal cavity and the anatomy and physiology of the velum and vowel nasalization. While we do not know how widespread this variation is and how important its effects on speech and language are, the available evidence suggests that this is a worthwhile direction of future research. In the end, the breadth of these questions is only limited by our imagination, the fossil and osteological data, and the kind of relationships between vocal tract anatomy, sound change and linguistic diversity that future work will establish.

Such investigations assume that the processes, forces and mechanisms that we observe today (in particular, the effects of vocal tract anatomy on speech and language) were also at work in the past in pretty much the same way—what is known as the uniformitarian principle. However, it is currently unclear how this principle should be applied in practice, because the farther back in time we go the more different things (gradually) become, until we cross into the long evolutionary history preceding the emergence of language as we know it [9,150]. Even closer to the present, if the link between food, bite and labiodentals [94] holds, then strict uniformitarianism breaks down at the dawn of agriculture, as we cannot expect pre-12 000-years old languages to have the same distribution of labiodentals as present-day languages, but the uniformitarian principle would still largely apply, as the same articulatory constraints and affordances worked then as they do today. (For more nuanced discussions and further developments, see [16], as well as [151–153].)

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank our ArtiVarK participants; David Norris and Paul Gaalman for access to and piloting on the Avanto MRI scanner; Thomas Maal, Frans Delfos and Cees Kreulen for access to and help with the TRIOS intra-oral scanner; Carly Jaques for participant recruitment and management; John Esling for recording the phonetic training materials; Sabine Kooijman for assistance with ethics; Rachel Schats for assistance with the Alkmaar skeletal collection. Sample access granted by the Stichting Cultureel Erfgoed Zeeland. Digitized image dissemination for educational purposes only. The osteological collections of Alkmaar and Middenbeemster were analysed at the Laboratory for Human Osteoarchaeology, Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden University.

Ethics

The ArtiVarK study is covered by the ethics approval 45659.091.14 (1 June 2015), Donders Center for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Data accessibility

The R code and data needed to reproduce the simulation plots and results reported here and in the electronic supplementary materials are freely available as described in the electronic supplementary materials. The 3D STL models of the four crania used in the simulations are available upon request from W.A.B.

Authors' contributions

D.D., S.R.M. and A.W.R. designed the research. W.A.B. and A.M.B. collected and analysed the historical samples, summarized the samples, described and plotted the landmarks. S.R.M. collected and analysed the contemporaneous sample; performed the biomechanical and acoustic simulations, analysed and plotted their results. D.D. drafted the paper. All authors contributed to the paper. All authors gave final approval for publication and agree to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Dutch Research Council (grant no. NWO276-70-022), the European Institutes for Advanced Study (grant no. EURIAS2017-2018) and the French National Research Agency (ANR)/IDEXLyon (grant no. 16-IDEX-0005).

References

- 1.Howard DM, Schofield J, Fletcher J, Baxter K, Iball GR, Buckley SA. 2020. Synthesis of a vocal sound from the 3,000 year old mummy, Nesyamun ‘True of Voice’. Sci. Rep. 10, 1-6. ( 10.1038/s41598-019-56316-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boë L-J, Heimb J-L, Hondac K, Maeda S. 2002. The potential Neandertal vowel space was as large as that of modern humans. J. Phon. 30, 465-484. ( 10.1006/jpho.2002.0170) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Boer B, Fitch WT. 2010. Computer models of vocal tract evolution: an overview and critique. Adapt. Behav. 18, 36-47. ( 10.1177/1059712309350972) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janssen R, Moisik SR, Dediu D. 2019. The effects of larynx height on vowel production are mitigated by the active control of articulators. J. Phon. 74, 1-17. ( 10.1016/j.wocn.2019.02.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieberman P, Crelin ES, Klatt DH. 1972. Phonetic ability and related anatomy of the newborn and adult human, Neanderthal man, and the chimpanzee. Am. Anthropol. 74, 287-307. ( 10.1525/aa.1972.74.3.02a00020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieberman P, Crelin ES. 1971. On the speech of Neanderthal man. Linguist. Inq. 2, 203-222. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berwick RC, Chomsky N. 2017. Why only us: recent questions and answers. J. Neurolinguistics 43(B), 166-177. ( 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2016.12.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hauser MD, Yang C, Berwick RC, Tattersall I, Ryan M, Watumull J, Chomsky N, Lewontin R. 2014. The mystery of language evolution. Front. Psychol. 5, 401. ( 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dediu D, Levinson SC. 2013. On the antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neandertal linguistic capacities and its consequences. Front. Lang. Sci. 4, 397. ( 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00397) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dediu D, Levinson SC. 2018. Neanderthal language revisited: not only us. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 21, 49-55. ( 10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.01.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renfrew C, McMahon A, Trask L (eds). 2000. Time depth in historical linguistics. Cambridge, UK: McDonald Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowern C, Evans B. 2014. The Routledge handbook of historical linguistics. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell L. 2004. Historical linguistics : an introduction. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lass R. 1997. Historical linguistics and language change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mallory JP, Adams DQ. 2006. The Oxford introduction to proto-Indo-European and the proto-Indo-European world. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Everett C. 2021. The sounds of prehistoric speech. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 376, 20200195. ( 10.1098/rstb.2020.0195) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Renfrew C, Nettle D (eds). 1999. Nostratic: examining a linguistic macrofamily. Cambridge, UK: McDonald Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salmons JC, Joseph BD (eds). 1998. Nostratic: sifting the evidence. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenberg JH. 2000. Indo-European and its closest relatives: the eurasiatic language family, volume 2, lexicon. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robbeets M, Bouckaert R. 2018. Bayesian phylolinguistics reveals the internal structure of the Transeurasian family. J. Lang. Evol. 3, 145-162. ( 10.1093/jole/lzy007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starostin SA, Dybo AV, Mudrak OA. 2003. Etymological dictionary of the Altaic languages. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heggarty P. 2013. Ultraconserved words and Eurasiatic? The ‘faces in the fire’ of language prehistory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E3254. ( 10.1073/pnas.1309114110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbieri C, Butthof A, Bostoen K, Pakendorf B. 2013. Genetic perspectives on the origin of clicks in Bantu languages from southwestern Zambia. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 21, 430-436. ( 10.1038/ejhg.2012.192) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haak W, et al. 2015. Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature 522, 207-211. ( 10.1038/nature14317) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olalde I, et al. 2018. The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature 555, 190-196. ( 10.1038/nature25738) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heggarty P. 2010. Prehistory through language and archaeology. In The Routledge handbook of historical linguistics (eds Bowern C, Evans B), pp. 498-626. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouckaert R, Lemey P, Dunn M, Greenhill SJ, Alekseyenko AV, Drummond AJ, Gray RD, Suchard MA, Atkinson QD. 2012. Mapping the origins and expansion of the Indo-European language family. Science 337, 957-960. ( 10.1126/science.1219669) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowern C, Atkinson Q. 2012. Computational phylogenetics and the internal structure of Pama-Nyungan. Language 88, 817-845. ( 10.1353/lan.2012.0081) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray RD, Atkinson QD. 2003. Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature 426, 435-439. ( 10.1038/nature02029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honkola T, Vesakoski O, Korhonen K, Lehtinen J, Syrjänen K, Wahlberg N. 2013. Cultural and climatic changes shape the evolutionary history of the Uralic languages. J. Evol. Biol. 26, 1244-1253. ( 10.1111/jeb.12107) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pagel M, Atkinson QD, Calude AS, Meade A. 2013. Ultraconserved words point to deep language ancestry across Eurasia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 8471-8476. ( 10.1073/pnas.1218726110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wichmann S, et al. 2012. The ASJP Database (version 15).

- 33.Jäger G. 2015. Support for linguistic macrofamilies from weighted sequence alignment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 12 752-12 757. ( 10.1073/pnas.1500331112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dediu D, Levinson SC. 2012. Abstract profiles of structural stability point to universal tendencies, family-specific factors, and ancient connections between languages. PLoS ONE 7, e45198. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0045198) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atkinson QD. 2011. Phonemic diversity supports a serial founder effect model of language expansion from Africa. Science 332, 346-349. ( 10.1126/science.1199295) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atkinson QD. 2012. Response to Comments on ‘Phonemic diversity supports a serial founder effect model of language expansion from Africa’. Science 335, 657. ( 10.1126/science.1210005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowern C. 2011. Out of Africa? The logic of phoneme inventories and founder effects. Linguist. Typol. 15, 207-216. ( 10.1515/lity.2011.015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cysouw M, Dediu D, Moran S. 2012. Comment on ‘Phonemic diversity supports a serial founder effect model of language expansion from Africa’. Science 335, 657. ( 10.1126/science.1208841) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dediu D, Janssen R, Moisik SR. 2017. Language is not isolated from its wider environment: vocal tract influences on the evolution of speech and language. Lang. Commun. 54, 9-20. ( 10.1016/j.langcom.2016.10.002) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dediu D, Moisik SR. 2019. Biology matters: variation in vocal tract anatomy and language. Sel. Pap. Theor. Appl. Linguist. 23, 19-33. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dediu D, Moisik SR. 2019. Pushes and pulls from below: anatomical variation, articulation and sound change. Glossa J. Gen. Linguist. 4, 7. ( 10.5334/gjgl.646) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. 2015. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 526, 68-74. ( 10.1038/nature15393) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tracy TS, et al. 2016. Interindividual variability in cytochrome P450-mediated drug metabolism. Drug Metab. Dispos. 44, 343-351. ( 10.1124/dmd.115.067900) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durand C, Rappold GA. 2013. Height matters—from monogenic disorders to normal variation. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 9, 171-177. ( 10.1038/nrendo.2012.251) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furr RM, Bacharach VR. 2007. Psychometrics: an introduction, 1st edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barbujani G, Colonna V. 2010. Human genome diversity: frequently asked questions. Trends Genet. 26, 285-295. ( 10.1016/j.tig.2010.04.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jobling MA, Hollox E, Hurles M, Kivisild T, Tyler-Smith C. 2013. Human evolutionary genetics. New York, NY: Garland Science. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reich D. 2018. Who we are and how we got here: ancient DNA and the new science of the human past. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowden R, MacFie TS, Myers S, Hellenthal G, Nerrienet E, Bontrop RE, Freeman C, Donnelly P, Mundy NI. 2012. Genomic tools for evolution and conservation in the chimpanzee: Pan troglodytes ellioti is a genetically distinct population. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002504. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002504) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewontin RC. 1972. The apportionment of human diversity. In Evolutionary biology (eds Dobzhansky T, Hecht MK, Steere WC), pp. 381-398. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Novembre J, et al. 2008. Genes mirror geography within Europe. Nature 456, 98-101. ( 10.1038/nature07331) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huxley J, Haddon AC. 1935. We Europeans: a survey of ‘racial’ problems. London, UK: J. Cape. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lippert-Rasmussen K. 2014. Born free and equal?: A philosophical inquiry into the nature of discrimination. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Livingstone FB, Dobzhansky T. 1962. On the non-existence of human races. Curr. Anthropol. 3, 279-281. ( 10.1086/200290) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts DE. 2011. Fatal invention: how science, politics, and big business re-create race in the twenty-first century. New York, NY: New Press. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saini A. 2019. Superior: the return of race science. London, UK: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nerbonne J. 2009. Data-driven dialectology. Lang. Linguist. Compass 3, 175-198. ( 10.1111/j.1749-818X.2008.00114.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meyerhoff M. 2015. Introducing sociolinguistics. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allott R. 1994. Motor theory of language: the diversity of languages. In Studies in language origins (eds Wind J, Jonker A, Allott R, Rolfe L), pp. 125-160. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brosnahan LF. 1961. The sounds of language: an inquiry into the role of genetic factors in the development of sound systems. Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brunner J, Fuchs S, Perrier P. 2009. On the relationship between palate shape and articulatory behavior. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 3936-3949. ( 10.1121/1.3125313) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lammert A, Proctor M, Narayanan S. 2013. Morphological variation in the adult hard palate and posterior pharyngeal wall. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 56, 521-530. ( 10.1044/1092-4388(2012/12-0059)) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ohala JJ. 1989. Sound change is drawn from a pool of synchronic variation. In Language change: contributions to the study of its causes (eds Breivik LE, Jahr EH), pp. 173-198. Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weirich M, Fuchs S. 2013. Palatal morphology can influence speaker-specific realizations of phonemic contrasts. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 56, 1894-1908. ( 10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0217)) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu ACL. 2013. Origins of sound change: approaches to phonologization. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Galluccio G, Castellano M, La Monaca C.. 2012. Genetic basis of non-syndromic anomalies of human tooth number. Arch. Oral Biol. 57, 918-930. ( 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.01.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jheon AH, Seidel K, Biehs B, Klein OD. 2013. From molecules to mastication: the development and evolution of teeth. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2, 165-182. ( 10.1002/wdev.63) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, Murray JC. 2011. Cleft lip and palate: synthesizing genetic and environmental influences. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 167-178. ( 10.1038/nrg2933) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leslie EJ, Marazita ML. 2013. Genetics of cleft lip and cleft palate. Am. J. Med. Genet. C 163, 246-258. ( 10.1002/ajmg.c.31381) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gokhman D, et al. 2020. Differential DNA methylation of vocal and facial anatomy genes in modern humans. Nat. Commun. 11, 1-21. ( 10.1038/s41467-020-15020-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murphy WA, zur Nedden D, Gostner P, Knapp R, Recheis W, Seidler H. 2003. The iceman: discovery and imaging. Radiology 226, 614-629. ( 10.1148/radiol.2263020338) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Van der Sanden W. 1996. Through nature to eternity: the bog bodies of northwest Europe. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Batavian Lion. See https://books.google.fr/books/about/Through_Nature_to_Eternity.html?id=GgFsQgAACAAJ&redir_esc=y. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Everett C, Blasi DE, Roberts SG. 2015. Climate, vocal folds, and tonal languages: connecting the physiological and geographic dots. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 1322-1327. ( 10.1073/pnas.1417413112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Everett C. 2017. Languages in drier climates use fewer vowels. Front. Psychol. 8, 1285. ( 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01285) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bastir M, Godoy P, Rosas A. 2011. Common features of sexual dimorphism in the cranial airways of different human populations. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 146, 414-422. ( 10.1002/ajpa.21596) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hall RL. 2005. Energetics of nose and mouth breathing, body size, body composition, and nose volume in young adult males and females. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 17, 321-330. ( 10.1002/ajhb.20122) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moreddu E, Puymerail L, Michel J, Achache M, Dessi P, Adalian P. 2013. Morphometric measurements and sexual dimorphism of the piriform aperture in adults. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 35, 917-924. ( 10.1007/s00276-013-1116-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bastir M, Rosas A. 2013. Cranial airways and the integration between the inner and outer facial skeleton in humans. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 152, 287-293. ( 10.1002/ajpa.22359) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Roseman CC, Weaver TD. 2004. Multivariate apportionment of global human craniometric diversity. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 125, 257-263. ( 10.1002/ajpa.10424) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Noback ML, Harvati K, Spoor F. 2011. Climate-related variation of the human nasal cavity. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 145, 599-614. ( 10.1002/ajpa.21523) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lieberman P. 1994. Functional tongues and Neanderthal vocal tract reconstruction: a reply to Dr. Houghton (1993). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 95, 443-450; discussion 450–2. ( 10.1002/ajpa.1330950408) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lieberman P. 2016. The evolution of language and thought. J. Anthropol. Sci. 94, 127-146. ( 10.4436/JASS.94029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fitch WT. 2000. The phonetic potential of nonhuman vocal tracts: comparative cineradiographic observations of vocalizing animals. Phonetica 57, 205-218. ( 10.1159/000028474) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fitch WT, Reby D. 2001. The descended larynx is not uniquely human. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 1669-1675. ( 10.1098/rspb.2001.1704) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.D'Anastasio R, et al. 2013. Micro-biomechanics of the Kebara 2 hyoid and its implications for speech in Neanderthals. PLoS ONE 8, e82261. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0082261) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brunner J, Fuchs S, Perrier P. 2005. The influence of the palate shape on articulatory token-to-token variability. ZAS Pap. Linguist. 42, 43-67. ( 10.21248/zaspil.42.2005.273) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Birkholz P. 2013. Modeling consonant-vowel coarticulation for articulatory speech synthesis. PLoS ONE 8, e60603. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0060603) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dediu D, Janssen R, Moisik SR. 2019. Weak biases emerging from vocal tract anatomy shape the repeated transmission of vowels. Nat . Hum. Behav. 3, 1107-1115. ( 10.1038/s41562-019-0663-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Janssen R, Moisik SR, Dediu D. 2018. Modelling human hard palate shape with Bézier curves. PLoS ONE 13, e0191557. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0191557) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lloyd JE, Stavness I, Fels S. 2012. ArtiSynth: a fast interactive biomechanical modeling toolkit combining multibody and finite element simulation. In Soft tissue biomechanical modeling for computer assisted surgery (ed. Payan Y), pp. 355-394. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moisik SR, Dediu D. 2017. Anatomical biasing and clicks: evidence from biomechanical modeling. J. Lang. Evol. 2, 37-51. ( 10.1093/jole/lzx004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mielke J, Smith B, Fox MJ. 2017. Implications of covert articulatory variation for several phonetic variables in Raleigh, North Carolina English. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 141, 3981. ( 10.1121/1.4989092) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Smith BJ, Mielke J, Magloughlin L, Wilbanks E. 2019. Sound change and coarticulatory variability involving English /ɹ/. Glossa J. Gen. Linguist. 4, 63. ( 10.5334/gjgl.650) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Blasi DE, Moran S, Moisik SR, Widmer P, Dediu D, Bickel B. 2019. Human sound systems are shaped by post-Neolithic changes in bite configuration. Science 363, eaav3218. ( 10.1126/science.aav3218) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Deter CA. 2009. Gradients of occlusal wear in hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 138, 247-254. ( 10.1002/ajpa.20922) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kaifu Y. 2000. Tooth wear and compensatory modification of the anterior dentoalveolar complex in humans. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 111, 369-392. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kaifu Y, Kasai K, Townsend GC, Richards LC. 2003. Tooth wear and the ‘design’ of the human dentition: a perspective from evolutionary medicine. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 122, 47-61. ( 10.1002/ajpa.10329) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.von Cramon-Taubadel N. 2011. Global human mandibular variation reflects differences in agricultural and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 19 546-19 551. ( 10.1073/pnas.1113050108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alemseged Z, Spoor F, Kimbel WH, Bobe R, Geraads D, Reed D, Wynn JG. 2006. A juvenile early hominin skeleton from Dikika, Ethiopia. Nature 443, 296-301. ( 10.1038/nature05047) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Arensburg B, Tillier AM, Vandermeersch B, Duday H, Schepartz LA, Rak Y. 1989. A Middle Palaeolithic human hyoid bone. Nature 338, 758-760. ( 10.1038/338758a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Martínez I, Arsuaga JL, Quam R, Carretero JM, Gracia A, Rodríguez L. 2008. Human hyoid bones from the middle Pleistocene site of the Sima de los Huesos (Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain). J. Hum. Evol. 54, 118-124. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.07.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Capasso L, Michetti E, D'Anastasio R. 2008. A Homo erectus hyoid bone: possible implications for the origin of the human capability for speech. Coll. Antropol. 32, 1007-1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Capasso L, D'Anastasio R, Mancini L. 2016. New evaluation of the Castel di Guido ‘hyoid’. J. Anthropol. Sci. 94, 231-235. ( 10.4436/JASS.94021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Frayer DW. 2017. Talking hyoids and talking Neanderthals. In Human paleontology and prehistory (eds Marom A, Hovers E), pp. 233-237. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ( 10.1007/978-3-319-46646-0_17) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Beals ME, Frayer DW, Radovčić J, Hill CA. 2016. Cochlear labyrinth volume in Krapina Neandertals. J. Hum. Evol. 90, 176-182. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.09.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Martínez I, et al. 2004. Auditory capacities in Middle Pleistocene humans from the Sierra de Atapuerca in Spain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9976-9981. ( 10.1073/pnas.0403595101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Martínez I, Quam RM, Rosa M, Jarabo P, Lorenzo C, Arsuaga JL. 2008. Auditory capacities of human fossils: a new approach to the origin of speech. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123, 3606. ( 10.1121/1.2934784) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Stoessel A, David R, Gunz P, Schmidt T, Spoor F, Hublin J-J. 2016. Morphology and function of Neandertal and modern human ear ossicles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11 489-11 494. ( 10.1073/pnas.1605881113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Beaudet A. 2017. The emergence of language in the hominin lineage: perspectives from fossil endocasts. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 427. ( 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00427) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Holloway RL. 2009. Brain fossils: endocasts. Encycl. Neurosci. 2, 253-261. [Google Scholar]

- 111.DeGusta D, Gilbert WH, Turner SP. 1999. Hypoglossal canal size and hominid speech. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1800-1804. ( 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1800) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jungers WL, Pokempner AA, Kay RF, Cartmill M. 2003. Hypoglossal canal size in living hominoids and the evolution of human speech. Hum. Biol. 75, 473-484. ( 10.1353/hub.2003.0057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Galloway A, Willey P, Snyder L. 1997. Human bone mineral densities and survival of bone elements: a contemporary sample. In Forensic taphonomy: the postmortem fate of human remains (eds Haglund WD, Sorg MH), pp. 295-317. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Waldron T. 1987. The relative survival of the human skeleton: implications for paleopathology. In Death, decay and reconstruction (eds Boddington A, Garland AN, Janaway RC), pp. 55-64. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Baetsen WA. 2016. Geometric morphometric analysis of the ‘skeletal vocal tract’: a first step in involving osteoarchaeology in the search for a potential ‘genetic bias’ for language, using two Dutch historical skeletal populations. MSc thesis, University of Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands. (https://hdl.handle.net/1887/45959) [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bosman AM. 2016. Talking heads. MSc thesis, Human Osteology and Funerary Archaeology, University of Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bosman AM, Moisik SR, Dediu D, Waters-Rist A. 2017. Talking heads: morphological variation in the human mandible over the last 500 years in the Netherlands. HOMO J. Comp. Hum. Biol. 68, 329-342. ( 10.1016/j.jchb.2017.08.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hoppa RD. 2000. Population variation in osteological aging criteria: an example from the pubic symphysis. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 111, 185-191. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Konigsberg LW, Hens SM. 1998. Use of ordinal categorical variables in skeletal assessment of sex from the cranium. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 107, 97-112. () [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ubelaker DH, Khosrowshahi H. 2019. Estimation of age in forensic anthropology: historical perspective and recent methodological advances. Forensic Sci. Res. 4, 1-9. ( 10.1080/20961790.2018.1549711) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cignoni P, Callieri M, Corsini M, Dellepiane M, Ganovelli F, Ranzuglia G. 2008. MeshLab: an open-source mesh processing tool. In Eurographics Italian chapter conference (eds Scarano V, Chiara RD, Erra U). The Eurographics Association. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wiley DF, et al. 2005. Evolutionary morphing. In Conf. Proc. VIS 05. IEEE visualization, 23–28 October, Minneapolis, MN, pp. 431-438. New York, NY: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zelditch ML, Swiderski DL, Sheets HD. 2012. Geometric morphometrics for biologists: a primer. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Brachin P. 1985. The Dutch language: a survey. Leiden, The Netherlands: EJ Brill Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- 125.De Vin A. 1952. Het dialect van Schouwen-Duiveland. Assen, The Netherlands: Van Gorcum & Comp. N.V. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Janssens G, Marynissen A. 2005. Het Nederlands van vroeger en nu. Leuven, The Netherlands: Uitgeverij Acco. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Van den Toorn MC, Pijnenburg WJJ, van Leuvenstijn JA, van der Horst JM. 1997. Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse taal. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Katzenberg MA, Waters-Rist AL. 2018. Stable isotope analysis. In Biological anthropology of the human skeleton (eds Katzenberg MA, Grauer AL), pp. 467-504. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Henry AG, Piperno DR. 2008. Using plant microfossils from dental calculus to recover human diet: a case study from Tell al-Raqā’i, Syria. J. Archaeol. Sci. 35, 1943-1950. ( 10.1016/j.jas.2007.12.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Weyrich LS, et al. 2017. Neanderthal behaviour, diet, and disease inferred from ancient DNA in dental calculus. Nature 544, 357-361. ( 10.1038/nature21674) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Richards MP, Trinkaus E. 2009. Out of Africa: modern human origins special feature: isotopic evidence for the diets of European Neanderthals and early modern humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 16 034-16 039. ( 10.1073/pnas.0903821106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wißing C, et al. 2019. Stable isotopes reveal patterns of diet and mobility in the last Neandertals and first modern humans in Europe. Sci. Rep. 9, 4433. ( 10.1038/s41598-019-41033-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mahoney P. 2006. Dental microwear from Natufian hunter-gatherers and early Neolithic farmers: comparisons within and between samples. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 130, 308-319. ( 10.1002/ajpa.20311) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Smith BH. 1984. Patterns of molar wear in hunter-gatherers and agriculturalists. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 63, 39-56. ( 10.1002/ajpa.1330630107) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Schats R. 2016. Life in transition: an osteoarchaeological perspective of the consequences of mediëval socioeconomic developments in Holland and Zeeland (AD 1000–1600). Doctoral thesis, University of Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands. See https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/43926. [Google Scholar]

- 136.van Hattum IJ. 2015. ‘What's on the Menu?’: Diet in Medieval Holland: a stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis of bone ‘collagen’ from early medieval Blokhuizen and late medieval Alkmaar. MSc thesis, University of Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands. (https://hdl.handle.net/1887/35568) [Google Scholar]

- 137.Waters-Rist AL, Hoogland MLP. 2018. The role of infant feeding and childhood diet in vitamin D deficiency in a nineteenth-century rural Dutch community. Bioarchaeol. Int. 2, 95-116. ( 10.5744/bi.2018.1020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Beck JM. 1988. Organic variation and voice quality. PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, UK. See https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/7125. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Laver J. 1980. The phonetic description of voice quality. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Richter D, et al. 2017. The age of the hominin fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, and the origins of the Middle Stone Age. Nature 546, 293-296. ( 10.1038/nature22335) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Moisik SR, Dediu D. 2020. The ArtiVarK click study: documenting click production and substitution strategies by learners in a large phonetic training and vocal tract imaging study. In The handbook of clicks (ed Sands B), pp. 384-417. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- 142.de Filippo C, Bostoen K, Stoneking M, Pakendorf B.. 2012. Bringing together linguistic and genetic evidence to test the Bantu expansion. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 3256-3263. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.0318) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Grollemund R, Branford S, Bostoen K, Meade A, Venditti C, Pagel M. 2015. Bantu expansion shows that habitat alters the route and pace of human dispersals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 13 296-13 301. ( 10.1073/pnas.1503793112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Engstrand O. 1997. Why are clicks so exclusive. In Proc. Fonetik-97, Umeå University, PHONUM 4, 191-194. [Google Scholar]

- 145.Fleming L. 2017. Phoneme inventory size and the transition from monoplanar to dually patterned speech. J. Lang. Evol. 2, 52-66. ( 10.1093/jole/lzx010) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Traunmüller H. 2003. Clicks and the idea of a human protolanguage. PHONUM 9, 1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Spitzer M. 2019. Neandertaler ohne F. Nervenheilkunde 36, 578-581. ( 10.1055/a-0916-1232) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Honda K, Hirai H, Masaki S, Shimada Y. 1999. Role of vertical larynx movement and cervical lordosis in F0 control. Lang. Speech 42, 401-411. ( 10.1177/00238309990420040301) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Moisik SR, Yun DPZ, Dediu D. 2019. Active adjustment of the cervical spine during pitch production compensates for shape: the ArtiVarK study. In Proc. 19th Int. Congress of Phonetic Sciences (ICPhS 2019), 5–9 August 2019, Melbourne, Australia, p. 5. Canberra, Australia: Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Fitch WT. 2010. The evolution of language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Christy TC. 1983. Uniformitarianism in linguistics. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company. See https://benjamins.com/catalog/sihols.31. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Walkden G. 2019. The many faces of uniformitarianism in linguistics. Glossa J. Gen. Linguist. 4, 52. ( 10.5334/gjgl.888) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Trudgill P. 2020. Millennia of language change: sociolinguistic studies in deep historical linguistics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The R code and data needed to reproduce the simulation plots and results reported here and in the electronic supplementary materials are freely available as described in the electronic supplementary materials. The 3D STL models of the four crania used in the simulations are available upon request from W.A.B.