Abstract

Georgia leads the nation in probation supervision, which has been the subject of recent legislative reforms. Probation supervision is the primary mechanism for monitoring and collecting legal financial obligations (LFOs) from people sentenced in Georgia courts. This Article analyzes how monetary sanctions and probation supervision intersect in Georgia using quantitative data from the Department of Community Supervision as well as interviews with probationers and probation officers gathered as part of the Multi-State Study of Monetary Sanctions between 2015 and 2018. Several key findings emerge: (1) there is substantial variation between judicial districts in the amount of fines and fees ordered to felony probationers in Georgia, with fines and fees in rural areas much higher than those in urban areas; (2) probationers express fear of incarceration solely for lack of ability to pay; (3) probation officers consider collecting LFOs as a distraction from their true mission of public safety; and (4) both probationers and probation officers question the purpose, effectiveness, and fairness of monetary sanctions in Georgia. This Article concludes with a discussion of reforms to date and further options for reform based on the findings from this research.

I. Introduction

Georgia is well-known as the national leader in probation supervision, with a rate of 5,570 per 100,000 people on felony or misdemeanor probation supervision as of 2015 (the most recent data available).1 This “dubious distinction”2 means that Georgia’s probation supervision rate is nearly four times the national average.3 Georgia’s largely privatized misdemeanor probation system in particular has garnered widespread criticism and litigation in recent years due to lack of transparency and mistreatment of low-income probationers who cannot afford to pay fines and fees.4

In 2015, the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform (GCCJR) recognized adult probation supervision as an area for much-needed reform.5 After studying the high rate of probation supervision in Georgia, the GCCJR made several recommendations that ultimately led to Senate Bill 174 (SB 174),6 which passed unanimously by the Georgia General Assembly and was signed into law by Governor Nathan Deal in 2017.7 Among several measures intended to curtail Georgia’s probation supervision rate, SB 174 included provisions requiring judges to waive or convert to community service fines, fees, and surcharges for people on felony supervision if they are indigent or face significant financial hardship.8 To provide greater oversight of misdemeanor probation in Georgia, House Bill 310 (HB 310), which was passed in 2015, created the Board of Community Supervision (the Board) within the Georgia Department of Community Supervision (DCS).9 The Board provides education and regulation for the state’s misdemeanor probation system and collects quarterly data on misdemeanor probationers.10

The Multi-State Study of Monetary Sanctions began collecting data on U.S. systems of LFOs in 2015.11 Georgia is one of eight states included in the study.12 The goal of the study was to examine how states’ multi-tiered systems of monetary sanctions operate across representative regions of the United States.13 Monetary sanctions are comprised of a wide variety of financial penalties for criminal convictions.14 These sanctions have varying purposes and legal justifications. Fines are typically imposed as punishment and viewed as a potential deterrent to future crime, while restitution is used to compensate victims’ losses.15 Court fees and surcharges are added on to base fines in order to recoup system costs, such as funding courts and other criminal justice system operations.16 In some cases, fees and surcharges are assessed in order to fund general government operations or funds that are seemingly far-flung from the criminal justice system.17

Georgia’s probation system is instrumental in monitoring and collecting LFOs, which is not the case in all states.18 This particular feature of Georgia’s system of monetary sanctions has ongoing implications for Georgia’s high rate of probation supervision and the reforms that have been enacted since 2015. This Article analyzes how monetary sanctions and probation supervision intersect in Georgia using quantitative data gathered from the DCS as well as interviews with probationers and probation officers gathered as part of the Multi-State Study of Monetary Sanctions between 2015 and 2018. Several key findings emerge from this analysis: (1) there is substantial variation between judicial districts in the amount of fines and fees ordered to felony probationers in Georgia, with fines and fees in rural areas much higher than those in urban areas; (2) probationers express fear of incarceration solely for lack of ability to pay; (3) probation officers consider collecting LFOs a distraction from their true mission of public safety; and (4) both probationers and probation officers question the purpose, effectiveness, and fairness of monetary sanctions in Georgia. This Article concludes with a discussion of reforms to date and further possibilities for reform based on the findings from this research.

II. Monetary Sanctions and Probation in Georgia

Like courts in other states, Georgia courts impose a variety of LFOs as part of sentencing for criminal offenses.19 These monetary sanctions include fines, fees, surcharges, and restitution.20 Georgia courts can impose a fine up to $100,000 as a condition of probation for felony offenses, unless otherwise specified by law.21 Misdemeanor (including traffic) offenses are eligible for fines up to $1,000, unless otherwise prescribed by law.22 In addition to fines, Georgia courts also impose a wide variety of surcharges and fees for specific beneficiary funds, court costs, and other purposes as required by state law.23

Despite similarities to other states in the imposition of such costs, some features of Georgia’s system of monetary sanctions are less common. In particular, the extent to which probation supervision is instrumental in monitoring and collecting LFOs on behalf of Georgia courts is distinct from many other states. For example, Minnesota courts exclusively use the Minnesota Department of Revenue’s Revenue Recapture Program to withhold state tax refunds for collecting outstanding court debt.24 Other states, like New York, make more extensive use of private collection agencies for recouping unpaid LFOs.25 And in Washington, county clerks are most pivotal in monitoring and sanctioning processes for unpaid LFOs.26

At the misdemeanor level, Georgia is one of about a dozen states to allow the use of private probation companies to supervise misdemeanor probationers.27 In fact, Georgia law explicitly disallows the state from supervising any misdemeanor probationers, who must be supervised by local or private entities instead.28 In contrast, Georgia law requires that all felony-level probationers be supervised by the state DCS.29 This system often results in abusive practices on the part of private probation companies, such as excessive fees and improper use of incarceration. Criminalized traffic offenses also create a substantial population on probation for “pay only” status, meaning that the only impetus for probation supervision is inability to pay traffic tickets at sentencing. According to Georgia’s DCS, seventy-five misdemeanor probation agencies currently operate in the state (including twenty-four private companies and fifty-one local government agencies).30 Information is not publicly available on supervision fees and other costs these agencies assess, but a media report cites monthly supervision fees between $25 and $45 in addition to start-up fees ($15) and daily fees ($7 to $12) for electronic monitoring.31 According to the Council of State Governments Justice Center, private probation companies in Georgia collected $121 million in fines, fees, restitution, and other payments in 2015 alone.32

Beyond court-imposed fines, fees, and surcharges, probationers in Georgia are charged additional supervision fees, whether on misdemeanor or felony supervision. By statute, felony probationers are to be charged a fee of $23 per month and a one-time charge of $50.33 Any individual serving under active probation must pay a $9 fee per month into the Georgia Crime Victims Emergency Fund.34 Further fees are attached to specific conditions of probation, such as reporting to a day reporting center ($10 per day)35 or completing a family violence intervention program (on a sliding fee scale if deemed indigent).36 Technology used to supervise probationers convicted of some offenses also incurs additional costs, such as electronic home monitoring and GPS.37

III. Study Design

The Multi-State Study of Monetary Sanctions began in 2015 with the goal of bringing a national perspective on how state-level systems of monetary sanctions function in practice.38 Currently, no national data sets provide a full understanding of the many disparate policies and practices surrounding LFOs across the country.39 The eight states that we examined (California, Georgia, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri, New York, Texas, and Washington) represent key regions of the country. We sought to first examine the “law on the books” in the statutes of our eight focal states, followed by a multi-pronged effort to study the “law in action” in courtrooms within each state.40

To achieve these goals, each state team began documenting state and local laws and ordinances pertaining to monetary sanctions in 2015.41 We also sought access to automated data from courts and corrections agencies to examine the amounts of LFOs ordered and collected.42 In 2016, we began fielding interviews with people who owed (or had paid in the recent past) LFOs (510 total across the eight states; 60 total in Georgia). In 2017 and 2018, we interviewed court decisionmakers including judges, attorneys, clerks, and probation officers, in each state (436 total across the eight states; 50 total in Georgia). We also observed an average of 200 hours of court proceedings per state, including courts handling felony and misdemeanor cases. In Georgia, we observed court proceedings and interviewed people in three judicial circuits, which represent Georgia’s urban, mid-sized, and rural communities.

In this Article, I draw on data from several of these sources. First, I describe findings from automated data provided by the Georgia DCS regarding the amounts of LFOs ordered to and owed by people on felony probation as of December 31, 2018. Second, I elaborate on several themes that emerged through our interviews with people on probation regarding their experiences with monetary sanctions while on supervision in Georgia. Finally, I describe how probation officers we spoke with view their role in monitoring and collecting LFOs. Together, this analysis shows that, despite recent reforms, problems remain with the intersection of probation supervision and monetary sanctions in Georgia. I conclude by suggesting opportunities for future reform.

IV. Findings

The Georgia DCS provided our study team with a data file containing information on 206,129 people under felony probation supervision as of December 31, 2018. Within this sample, 67,172 people (33%) had information on LFOs, including court fines, fees, and restitution. There are, however, several limitations to the data set. First, it does not contain information on probation fees due to inaccuracy in data collection for this measure. Second, information on restitution for probationers is very sparse (n = 313). As a result, I am unable to provide an analysis that includes these dimensions of monetary sanctions. Third, the data field for court-ordered fines and fees is a lump-sum amount that cannot be directly linked to individual convictions or offense types. Individuals in the sample may have been convicted of several counts for different offenses, but I am unable to parse the data to attach dollar amounts to specific offense types. With these caveats in mind, I present a descriptive analysis from the available data of the scope of LFOs for people under felony probation supervision in Georgia.

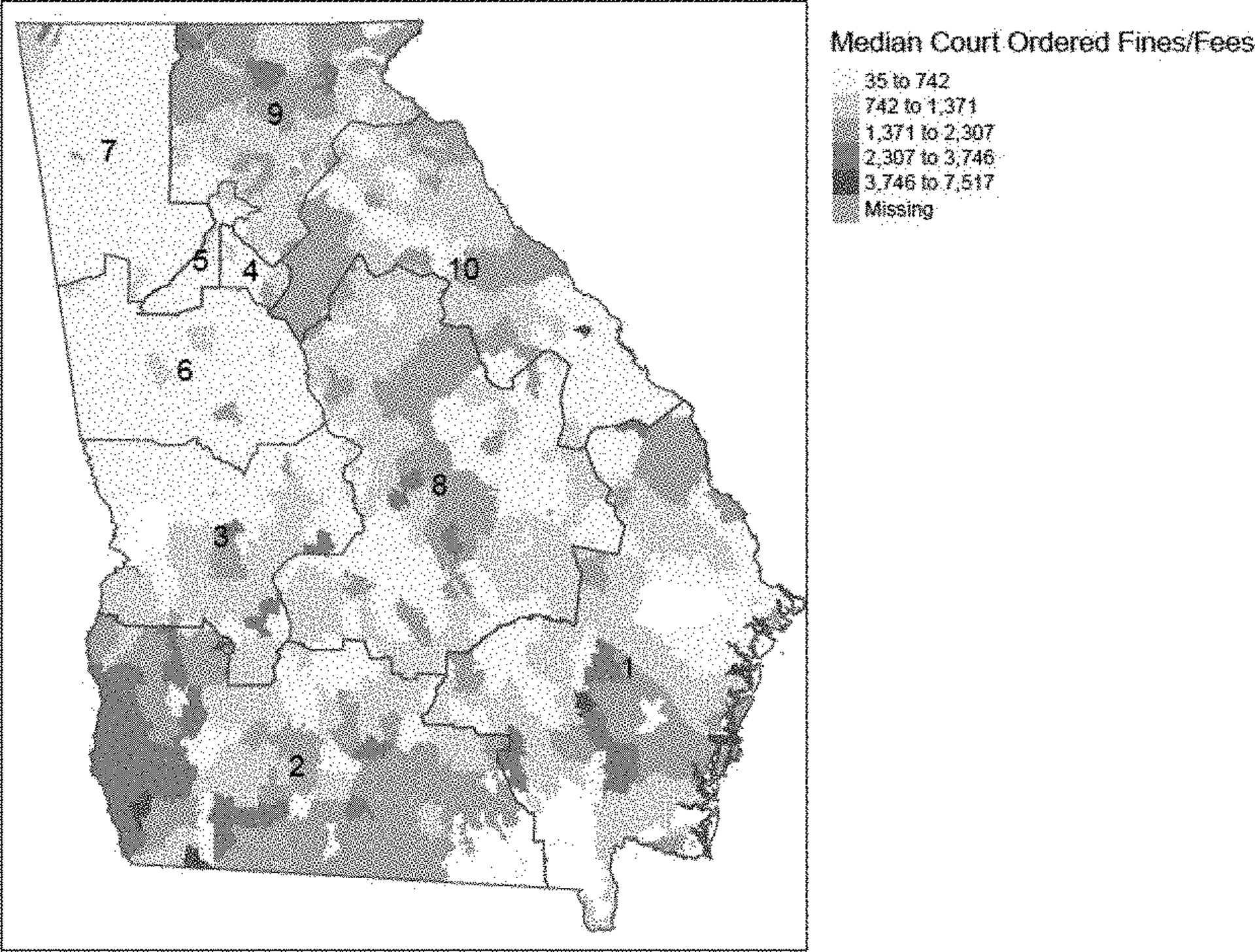

Figure 1 below shows the geographic distribution of median court fines and fees ordered to people on felony probation in Georgia by zip code of residence according to year-end 2018 data. Median amounts are displayed to account for the effect of high outlier fine amounts. The map overlays the boundaries of Georgia’s ten judicial districts in order to display any apparent patterns by district. Notably, median fine and fee amounts ordered to probationers living in districts four through seven appear to be considerably lower than probationers residing in other districts, particularly districts two and nine, which contain multiple zip codes in which median amounts of fines and fees ordered exceed $2,300.

Figure 1.

Median Court Fines and Fees Ordered by Zip Code of Residence for Felony Probationers in Georgia, December 31, 2018.

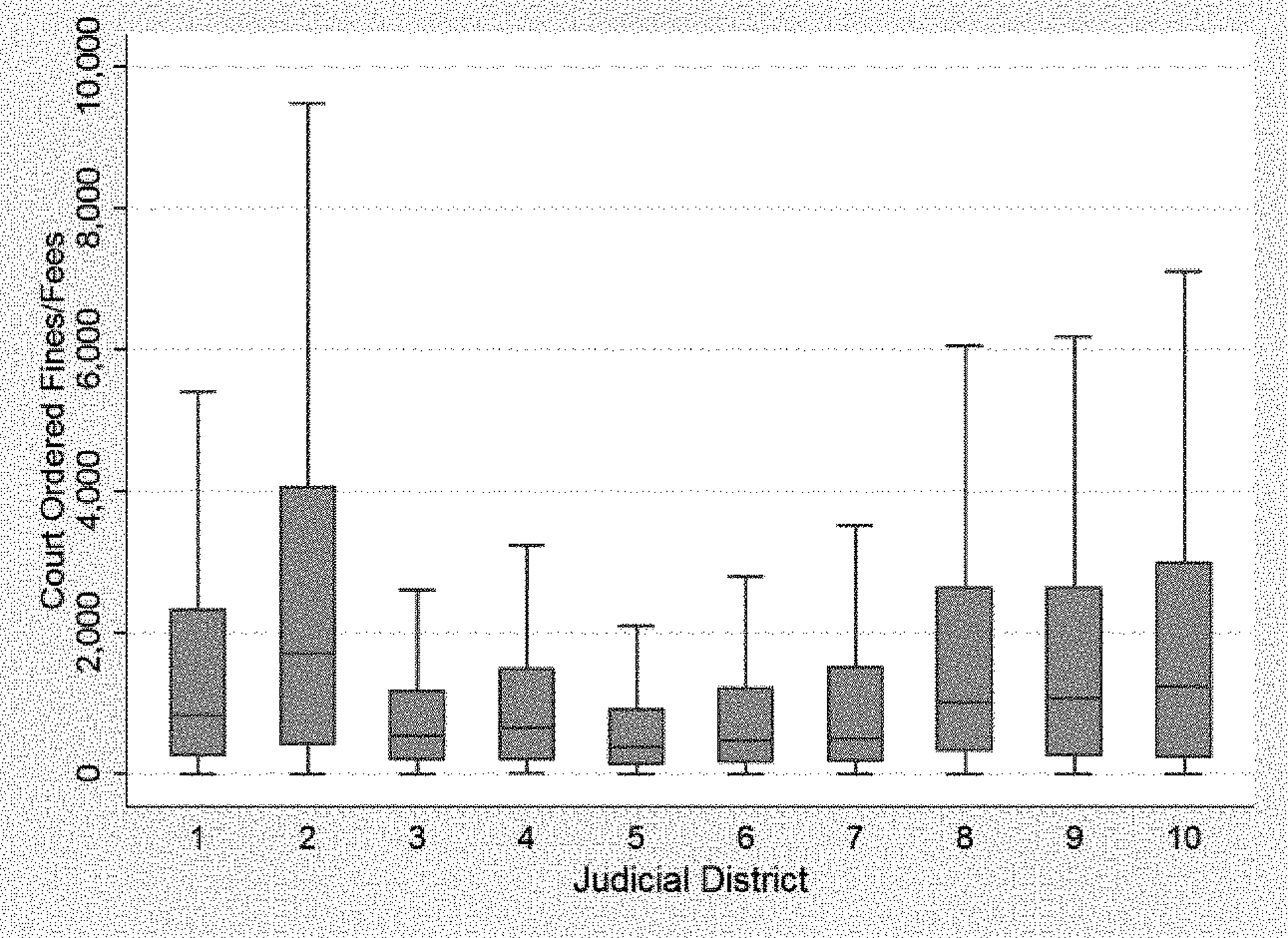

Figure 2 below provides box plots of court fines and fees ordered by Georgia judicial districts. The data for this figure is limited to individuals who were sentenced in only one judicial district because we cannot examine the total dollar amounts by case for individuals who were convicted in more than one district. This reduces the total sample size to 60,534 felony probationers.

Figure 2.

Box Plot of Court Ordered Fines and Fees by Georgia Judicial Districts.

Figure 2 shows a very similar pattern as Figure 1, in which the Second Judicial District, located in the southwestern corner of the state, has the highest median court fines and fees ordered ($1,715), as compared to the Fifth Judicial District (encompassing Fulton County), which has the lowest median court fines and fees ordered ($390). The Second Judicial District also has the highest variability, as indicated by the interquartile range of $3,636. Taken together, these figures indicate a pattern of lower court fines and fees in the urban core of the Atlanta Metropolitan area than in more rural regions of the state. The second-highest median fines and fees ordered are found in the Tenth Judicial District ($1,233), which contains the moderate-sized cities of Augusta and Athens, followed by the Ninth and Eighth Judicial Districts ($1,077 and $1,012, respectively). The second-lowest median court fines and fees amounts are found in the Sixth Judicial District ($471), which encompasses suburban counties like Clayton, Coweta, and Henry.

To examine whether there are statistically significant differences in the amounts of court-ordered fines and fees as well as amounts owed by probationers as of December 31, 2018, I performed an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis using a subsample of 33,134 individuals with sufficient information on demographic characteristics (e.g., race, sex, and age), prior conviction history, any prison time, any violent conviction, and judicial district.43

Table 1 below presents the results of the OLS regression analysis. Specifically, Model 1 shows results for court fines and fees ordered to felony probationers. The dependent variable is the dollar amount ordered, adjusted for inflation to December 31, 2018 based on the year of sentencing. On average, there does not appear to be a statistically significant difference in court fines and fees ordered by race. Men, however, are ordered to pay $105.90 more on average than women. Age is also a significant factor. Each additional year of age is associated with a $16.05 increase in fines and fees. Probationers sentenced to any time in prison are sentenced to $102.90 less in court fines and fees than are those without a prison sentence. Each prior conviction is associated with an additional $36.28 in fines and fees, but violent offenses are associated with lower fines and fees than other offense types.

Table 1.

OLS Regression Models for Court Fines and Fees.44

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Fines/Fees | Fines/Fees | |

| Variables | Ordered | Owed |

| Black | −43.19 (27.12) |

86.82*** (24.91) |

| Male | 105.90** (37.53) |

84.25* (34.47) |

| Age | 16.05*** (1.145) |

8.31*** (1.05) |

| Prison sentence | −102.90*** (29.16) |

−1.66 (26.78) |

| Number of prior convictions | 36.28*** (7.509) |

27.47*** (6.90) |

| Any violent offense | −338.90*** (27.97) |

−291.40*** (25.70) |

| Judicial District 1 | 659.00*** (76.32) |

263.60*** (70.11) |

| Judicial District 2 | 2073.00*** (73.80) |

1986.00*** (67.79) |

| Judicial District 3 | 216.80** (73.89) |

294.10*** (67.87) |

| Judicial District 4 | 485.80*** (146.70) |

608.90*** (134.80) |

| Judicial District 6 | 131.60 (75.43) |

194.40** (69.29) |

| Judicial District 7 | 364.80*** (69.60) |

378.80*** (63.93) |

| Judicial District 8 | 1042.00*** (77.13) |

787.00*** (70.85) |

| Judicial District 9 | 1276.00*** (73.35) |

756.30*** (67.37) |

| Judicial District 10 | 1519.00*** (70.34) |

1178.00*** (64.61) |

| Constant | 232.60* (92.08) |

−301.20*** (84.58) |

| Observations | 33134 | 33134 |

| R-squared | 0.09 | 0.07 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

p <0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

The results for judicial districts confirm the geographic pattern in Figures 1 and 2. As compared to the Fifth Judicial District (the reference category), all other districts have higher court-ordered fine and fee amounts. The Sixth Judicial District is the only district that is not statistically different than the Fifth Judicial District. The Second Judicial District stands out for ordering $2,073 more in fines and fees on average than the Fifth Judicial District, followed by the Tenth, Ninth, and Eighth Judicial Districts—each of which order $1,000+ more on average in fines and fees than the Fifth Judicial District.

While this analysis of court fines and fees ordered does not show any statistically significant differences by race, Model 2 shows a significant difference by race for amounts of fines and fees owed as of December 31, 2018. Even taking into account all other factors in Model 2’s predictions of the dollar amount of fines and fees still owed at year-end 2018, black probationers owed $86.82 more than probationers of other racial groups. There are few other statistically significant differences between Model 1 and Model 2. Notably, probationers with prison sentences did not owe significantly more than those without. In Model 2, all judicial districts show significantly higher amounts owed than the Fifth Judicial District did.

Overall, this statistical analysis shows significant differences by judicial district in the amounts of fines and fees ordered to and owed by people on felony probation in Georgia. In particular, probationers residing in rural areas of Georgia pay higher amounts of fines and fees than felony probationers in urban and suburban areas. This finding holds even when available demographic and criminal justice factors are controlled for in the models. In addition, while there were no differences by racial group in amounts ordered, black probationers had higher outstanding balances than probationers of other racial groups.

Our interviews with people currently on probation supervision across three judicial circuits revealed several notable themes with implications for future reforms.45 In total, we interviewed sixty people on felony and misdemeanor supervision in Georgia. Regardless of whether they were under supervision by DCS or by a misdemeanor agency, all expressed that they had been threatened with incarceration if they failed to pay their fines and fees. As one probationer in a mid-sized community put it:

Well, see I was always told that they can’t lock you up for non-payment, but every time I get in front of a probation officer they tell me that they are allowed to lock me up for non-payment. Last month[,] I went in front of my [probation officer] supervisor[,] and she told me that if I didn’t pay $75 a week, or $75 a month, and get 16 hours community service each month I was going to go to jail, so I don’t know.

Another probationer in a large, urban circuit similarly said, “They want the money. Either you [sic] gonna pay or you’re going to jail. One of the two.” A probationer in a small, rural circuit put it this way: “They’re saying … [if] you can’t make this payment, we’re going to lock you up.” Incarceration for failure to pay was a consistent concern expressed across our sample of people sentenced to fines and fees, regardless of where they lived, where they were sentenced, or whether they were under felony or misdemeanor probation supervision.

People on probation described several negative consequences of this threat. For example, some probationers we spoke with described making significant trade-offs in paying other bills because they were afraid of being incarcerated for failing to pay. As one probationer in a small, rural circuit put it:

When I was ordered to pay the $250 in the next two weeks[,] … [s]he gave me two weeks to pay that. It was either pay my car payment, pay half my rent, or pay this probation. Well, if I don’t pay probation, no sense in me trying to keep this car, ‘cause I’m a be [sic] locked up. No sense in me trying to keep this apartment, ‘cause I’m a be [sic] locked up. So I took [$]250 and paid the probation, like I ought to do.

Similarly, a probationer in a small, rural circuit expressed:

I think they should be a little bit more understanding, which everybody got a life to live and I understand that, but I think they should be a little bit more understanding with people.

In addition, probationers spoke of not reporting to their probation officer when they did not have money to pay in a given month out of fear of being incarcerated. As one probationer in a large urban circuit put it:

I was always afraid to go in if I went so long without obtaining a job. I’d be paranoid they were going to lock me up for being broke. Which is really messed up. So then I was like, “nope,” then I have a warrant. I’ll have a warrant until they catch me or whatever.

In contrast, all eleven of the probation officers we interviewed across three circuits reported that probation revocations are never initiated solely based on unpaid LFOs. Rather, failure to pay is often included as part of a broader picture of lack of compliance with supervision conditions when probation revocations are initiated. This response from a probation officer in a mid-sized circuit was typical of the officers we spoke with:

Not for just fines. If they’re gonna [sic] mess up, they’re messing up across the board.… Generally, payment by itself is more of the salt and pepper of the stew than it is the meat. It’s a way to draw an impression of their whole attitude, but it’s never a deciding factor as far as whether or not they’re getting a warrant.

Likewise, a probation officer in a rural circuit said, “[I]f we’re going to revoke you, it’s not going to be just because of a fee. It’s going to be a fee[,] and you caught a new charge.” An officer in a mid-sized circuit acknowledged that there can be gray areas, particularly when probationers fail to report because they are afraid of being incarcerated for non-payment. In this case, a revocation might be initiated because of the technical violation of failing to appear:

Sometimes people who can’t pay become desperate[,] so they just stop reporting, stop answering. So, that’s why we stress when we do intake and stuff, if you can’t pay, don’t run away, don’t abscond. Don’t lose contact with us. Let us know what’s going on, because if the judge calls and says, “Hey, why isn’t Mr. Joe paying?” And I say, “I don’t know,” that’s not going to look good. He’s going to say, “Go find out.” But if he says, “Why is Joe paying so little?” I say, “Listen, Joe’s got this going on, this, this and this, he’s paying what he can,” whether it’s $5, whether it’s the whole month some months or whether it’s just the $32 fee or it’s just $10, he’s making his payments, he’s trying.

However, probation officers we spoke with did see problems with the intersection of probation supervision and LFOs in their day-today work. In fact, the DCS officers we interviewed were nearly universal in their opinion that monitoring and collecting LFOs is not the most important aspect of their jobs, yet it requires a disproportionate amount of their time. These officers expressed that their time is best spent supervising people that they think pose a greater threat to public safety. One officer in a rural circuit summarized what we heard from many of the officers we interviewed across three circuits on this subject:

We are more concerned with them not reoffending with major felonies and violent crimes on other people, stealing from other people. We’re more concerned with safety of the community than just fines and fees to be honest with you. The judges may not want to hear that.… I can speak personally that that’s always been lower on my radar than anything else. I’m more worried about making sure that you’re not on drugs. You’re not committing new crimes. You know? You’re being a productive citizen. You’re getting a job.… I could probably safely say that that’s probably the rest of them too, if not [the] majority statewide.

Similarly, a probation officer in a large, urban circuit emphasized the greater importance of officers’ efforts to help probationers get drug treatment and jobs, which he argued would help the state by producing more law-abiding taxpayers:

Work on people getting treatment.… Even if we put them to work, it doesn’t guarantee that they’re going to be able to have the means to pay the money. If we can solve those issues, we at least have some tax money coming into the state, and everybody’s productive.

In addition to concerns about how time spent monitoring and collecting LFOs distracts from their public safety mission, some officers pointed to revenue generation as a purpose of fines and fees that is philosophically out of step with their priority of ensuring public safety. Officers also noted that fines and fees often unduly burden their probationers who cannot afford to pay them. As one officer in a mid-sized circuit put it:

Other than a way to keep the machine running. I understand the need to collect fines to pay to run a system. As far as using fines as a punishment, I honestly wish that we did it more like some European countries[] [w]here the punishment is based on income. If you’re on disability and drawing $500.00 a month, why should we be able to fine you $1,500.00 when we’re also gonna [sic] fine $1,500.00 for the guy that’s making 50 grand a year?

Another officer expressed a similar concern about funding government operations with fines and fees:

I do believe that just as often, we miss the mark and tend to over-assess in an effort to get the pound of flesh, and for the clerk’s office, which would scream at me if they heard me say this, but I don’t know if it’s really the best practice to try and I don’t know, fund county government offices off of court time. Which is why they raised Cain, that we’ve not been getting our fines and whatever, well, we’re assessing people as fines who in many cases may not be able to afford them. Just as often as we hit the mark, I think we miss it.

As a result, several officers we spoke with expressed a desire for probation officers to be relieved of the task of collecting LFOs altogether. Some suggested that the state should outsource collections of monetary sanctions to third-party collection agencies or to make more extensive use of tax intercept and wage garnishment programs. One officer in an urban circuit explained that other government or private entities have access to information and tools that would make collecting LFOs more efficient than probation:

I think we should get out of collecting fines. We don’t do a good job of it.… [S]omebody else could do it better.… When you have a private agency that can run your social and can get all this information, I can’t do that. I don’t have that ability. I can’t garnish wages.

An officer in a rural circuit echoed this idea:

Personally, I think that somebody else needs to be collecting it besides us … because we just have so many more serious issues to deal with than being a collection agency if you will. I mean that would probably be my only recommendation is that we shouldn’t be dealing with it at all.

To summarize, our findings from interviews with sixty probationers and eleven probation officers across three judicial circuits in Georgia revealed several significant problems at the intersection of monetary sanctions and probation. Probationers almost universally expressed fear of and experiences with being threatened with incarceration solely for non-payment. They further explained how making LFO payments often meant making trade-offs with paying other bills, such as rent or medical expenses. This fear sometimes led probationers to avoid reporting to their officers, which then led to revocations for failure to appear. The probation officers we interviewed acknowledged this tension and noted that while they do not directly incarcerate probationers solely for failure to pay, some probationers might fail to appear as a result of this fear and wind up incarcerated anyway. Officers also endorsed public safety, not debt collection, as their primary mission. Some officers questioned whether using court fines and fees to fund government operations is sensible, especially when it unduly burdens people with limited incomes. And several officers proposed alternatives, such as basing fines and fees on probationers’ income at sentencing and using wage garnishment or tax intercept programs, as more effective mechanisms for recouping LFOs. Taken together, both probationers and probation officers question the purpose, effectiveness, and fairness of monetary sanctions as currently assessed by courts in Georgia.

V. Opportunities for Future Reform

Data collection for this Article took place between 2015 and 2018—the same time frame in which the Georgia General Assembly and Governor Deal passed legislation to address felony probation supervision, including efforts to curtail the role of fines and fees in keeping people under supervision for long periods of time.46 Because this data collection was underway as the legal ground was shifting, this Article is not able to assess the long-term impacts of these legal changes. However, the analysis presented here suggests that an evaluation of the recently enacted legislation is needed to determine whether the problems identified by this research persist.

Beyond the reforms brought about by SB 174 and other legislation, this analysis highlights several additional avenues for future policy change. One potential reform is to completely de-couple enforcement and collection of monetary sanctions from probation supervision, as many of the officers in our sample endorsed. There are other means to do so that would impose a lower burden on corrections staff and perhaps be more efficient. This would also eliminate the concern expressed so frequently by the probationers we interviewed that reporting to their probation officers could lead to incarceration for failure to pay.

Second, these findings highlight the need for clearer communication and ongoing education efforts for probationers about the consequences of non-payment, should probation supervision continue to be the primary mechanism for monitoring and collecting LFOs in Georgia. Officers stated that they explain to probationers at intake that they cannot be incarcerated solely for failure to pay. However, the fact that probationers universally consider incarceration a likely outcome of non-payment demonstrates the need for sustained communication with probationers about their rights and what type of behavior justifies incarceration while on supervision.

Third, this analysis points to a need to more systematically address ability to pay at the time of sentencing. Probationers in our sample discussed their struggles in making trade-offs between LFO payments and other essential bills, while the probation officers we interviewed noted that many of the people they supervise cannot pay what is assessed. The impact of SB 174 needs further study, particularly its emphasis on converting fines and fees to community service and its provisions on the presumption of indigence for individuals meeting certain conditions. These reforms were discussed by probation officers in our study, but implementation was too new for us to assess its effects during our study period. Beyond these enacted reforms, implementing a statewide, systematic assessment of ability to pay for all courts and allowing greater flexibility at sentencing by eliminating mandatory fines, fees, and surcharges are further reforms to explore.

Finally, while this Article provides an analysis of the best available quantitative data on the intersection of probation supervision and LFOs in Georgia, substantial data limitations make it impossible to assess the full scope and breadth of this system. There are many important questions about LFOs and probation supervision in Georgia that cannot be fully answered using these data. Because Georgia does not have a unified court system, quantitative data on LFOs statewide are severely limited. The DCS data provide a limited picture but do not facilitate a comprehensive quantitative analysis that could draw more substantial conclusions about how the system functions. Improved data collection statewide, as well as more ready access to these data by researchers, is a vital next step in furthering criminal justice reform in Georgia.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant to the University of Washington from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation (Alexes Harris, Principle Investigator). I thank the faculty and graduate student collaborators of the Multi-State Study of Monetary Sanctions for their intellectual contributions. Partial support for this research came from a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant (P2C HD042828) to the Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology at the University of Washington. Brittany Martin, Daniel Boches, Amairini Sanchez, Timothy Edgemon, Avery Warner, and many undergraduate research assistants provided invaluable research support for the Georgia arm of the study.

References

- 1.Kaeble Danielle & Bonczar Thomas P., U.S. Dep’t. of Just., Probation and Parole in the United States, 2015, at 16 (2016), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ppusl5.pdf.

- 2.Boggs Michael P. & Miller Carey A., Report of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform 8 (Feb. 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.See Kaeble & Bonczar, supra note 1, at 16. The national average is 1,522 per 100,000 people. Id.

- 4.See Boggs & Miller, supra note 2, at 8.

- 5.See Boggs Michael P. & Worthy W. Thomas, Report of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform 62–63 (Feb. 2015) (recognizing the need to improve probation supervision). [Google Scholar]

- 6.See id.; S.B. 174, 2017 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ga. 2017).

- 7.See Georgia Governor Signs Bill to Strengthen Probation and Increase Public Safety, Council St. Gov’ts Just. Ctr. (May 10, 2017), https://csgjusticecenter.org/georgia-governor-signs-bill-to-strengthen-probation-and-increase-public-safety/ (reporting the passage of SB 174).

- 8.Ga. S.B. 174.

- 9.H.B. 310, 2015 Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ga. 2015).

- 10.Id.

- 11.See Alexes Harris et al., United States Systems of justice, Poverty and the Consequences of Non-Payment of Monetary Sanctions 4 (2017), http://www.monetarysanctions.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Monetary-Sanctions-2nd-Year-Report.pdf (researching LFOs in the “context of raising national awareness of the practice of sentencing fines and fees”).

- 12.Id. The study also examines California, Illinois, Minnesota, Missouri, New York, Texas, and Washington. Id.

- 13.See id.

- 14.See id. at 5.

- 15.See Martin Karin D. et al. , Monetary Sanctions: Legal Financial Obligations in US Systems of Justice, 1 Ann. Rev. Criminology 471, 472 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Id.

- 17.Id.

- 18.See Alexes Harris et al. , Monetary Sanctions in the Criminal Justice System 3 (2017), http://www.monetarysanctions.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Monetary-Sanctions-Legal-Review-Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris et al., supra note 11, at 48.

- 20.See id. at 50–59.

- 21.O.C.G.A. § 17-10-8 (2018).

- 22.Id. § 17-10-3.

- 23.Harris et al., supra note 11, at 51.

- 24.Minn. Stat. Ann. § 270A.03 (West 2020).

- 25.N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 20–489 (2020).

- 26.Harris Alexes, Evans Heather & Beckett Katherine, Drawing Blood from Stones: Legal Debt and Social Inequality in the Contemporary United States, 115 AM. J. Soc 1753, 1759 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 27.See Harris et al., supra note 11, at 23.

- 28.O.C.G.A. § 17-10-3 (2016).

- 29.The Georgia Code allows judges of county and municipal courts to enter into contracts with private corporations to provide probation supervision and money collections services for misdemeanor probationers with unpaid court debt. Id. § 42-8-101.Counties or municipalities may opt to establish a public probation system in lieu of private companies if they so choose. Id. Felony probationers may not be supervised by private companies. Id.

- 30.See Provider Information List, Misdemeanor Prob. Oversight, https://sites.google.com/a/des.ga.gov/department-of-community-supervision2/provider-information-list (last visited Mar. 5, 2020) (listing the misdemeanor probation services in Georgia).

- 31.See, e.g., Hannah Rappleye & Lisa Riordan-Seville, ‘Cash Register Justice’: Private Probation Services Face Legal Counterattack, NBC News (Oct. 24, 2012, 3:26 AM), http://investigations.nbenews.com/_news/2012/10/24/14653300-cash-register-justice-private-probation-services-face-legal-counterattack (noting amounts of common supervision fees that misdemeanor probation agencies assess).

- 32.Barbee Andy et al. , Council of St. Gov’ts Just. Ctr., Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform: First Probation Subcommittee Meeting 31 (2016), https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/JR-in-GAFirst-Presentation.pdf.

- 33.O.C.G.A. § 42-8-34(d)(1) (2018).

- 34.Id. § 17-15-13(f); see also id. § 17-15-9(b)(2) (“The funds placed into the [Georgia Crime Victims Emergency Fund] shall also consist of all moneys … recovered on behalf of the state pursuant to this chapter by subrogation or other action.…”

- 35.Id. § 42-8-34(d)(3).

- 36.Id. § 42-8-35.6.

- 37.Id. § 42-8-35(a)(14).

- 38.See Harris et al., supra note 11, at 4.

- 39.See Martin et al., supra note 15, at 478 (“The lack of consistent and exhaustive measures of monetary sanctions presents a unique problem for tracking both the prevalence and amount of LFOs over time.”).

- 40.See Harris et al., supra note 18, at 41 (analyzing the “law on the books” and the “law in action” in California).

- 41.See id. at 8–10 (providing details of the study’s methodology).

- 42.See Martin et al., supra note 15, at 478 (noting the use of secondary data).

- 43.Due to the data limitations noted above, caution should be taken in interpreting these results. I present this analysis because it represents the best available information on LFOs and felony probationers in Georgia.

- 44.Data are not available from DCS on income or socioeconomic status for probationers, so I am not able to account for income-based differences.

- 45.The rest of this Part includes direct quotes from probationers, probation officers, and other stakeholders in this field. In the interest of anonymity, the sources of these quotes will remain confidential.

- 46.See supra text accompanying notes 8–9.