Abstract

Research Summary:

In addition to outsourcing the management of correctional facilities, many local and state authorities contract with private companies to provide a variety of services and processes within U.S. courthouses, jails, and prisons. In this article, we explore the various “cost points” at which individuals who make contact with public systems of justice are charged by private entities. We provide two case studies with an in-depth look at how private companies make money within U.S. justice facilities—court-ordered programs and prison services.

Policy Implications:

Through our examples, we show the extent to which private companies generate profits within U.S. systems of justice and the potential impacts of justice “cost points” on those involved in these systems. We end by suggesting policy makers more thoroughly explore the reasons for the privatization of justice system practices and services and develop transparent oversight to ensure private arrangements do not impose undue burdens on justice-involved individuals and their families.

Keywords: costs, criminal justice, prison services, private corrections, privatization

1. INTRODUCTION

Discussion about “private corrections” has often been focused on the rising use of private prisons. Since the 1980s, federal and local governments have increasingly used public money to hire private corporations to house and manage incarcerated populations. In 2016, 13% of people held in federal prisons, and 8% of people held in state facilities, were in privately operated institutions. These numbers increased by 165% and 24%, respectively, from the year 2000 (Kaeble & Cowhig, 2016). This endeavor has been lucrative. CoreCivic (formerly known as Corrections Corporation of America), one of the largest private prison management firms in the United States, generated $1.8 billion in total revenue in 2015, which was a 9% increase from 2014 (Corrections Corporation of America, 2015).

Although private prisons rightfully garner much scholarly and public attention, they are only one aspect of the private corrections industry. In addition to outsourcing the entire management of correctional facilities, many local and state authorities enter into contracts with private companies for a variety of services and processes within U.S. courthouses, jails, and prisons. Even though justice institutions primarily remain public entities, private corporations are running many key justice system programs and generating large profits from captive populations.

In this article, we explore the various “cost points” at which individuals who make contact with public systems of justice are charged by private entities. At times these costs are exchanged for actual services or products; at other times private entities are allowed by local governments to charge people for the forced management of their bodies and property. After reviewing these various cost points, we provide two case studies with in-depth examination of how private companies make money within U.S. justice systems. In the first, we explore how the city of Seattle contracts out services to monitor and control people who make contact with the courts. In the second example, we describe the relationship between the Washington State Department of Corrections (DOC) and a national prison-tech company called JPay. Companies like JPay regularly contract with local, state, and federal prisons across the nation to provide services and products to people who are incarcerated.

Our aim is threefold. First, to explore the ways corporations are allowed by local and state jurisdictions to generate profits within our public systems of justice and the potential consequences for people forced to make these payments. Second, to begin a dialogue about the ethical considerations of public entities transferring portions of a tax-funded public good (i.e., the operations of justice systems) to private corporations. And third, to outline a research agenda for better exploring the various cost points of the private corrections industry and to examine more effectively the legal, financial, and justice-oriented implications of these increasing practices.

2. PRIVATE “COST POINTS” WITHIN U.S. SYSTEMS OF JUSTICE

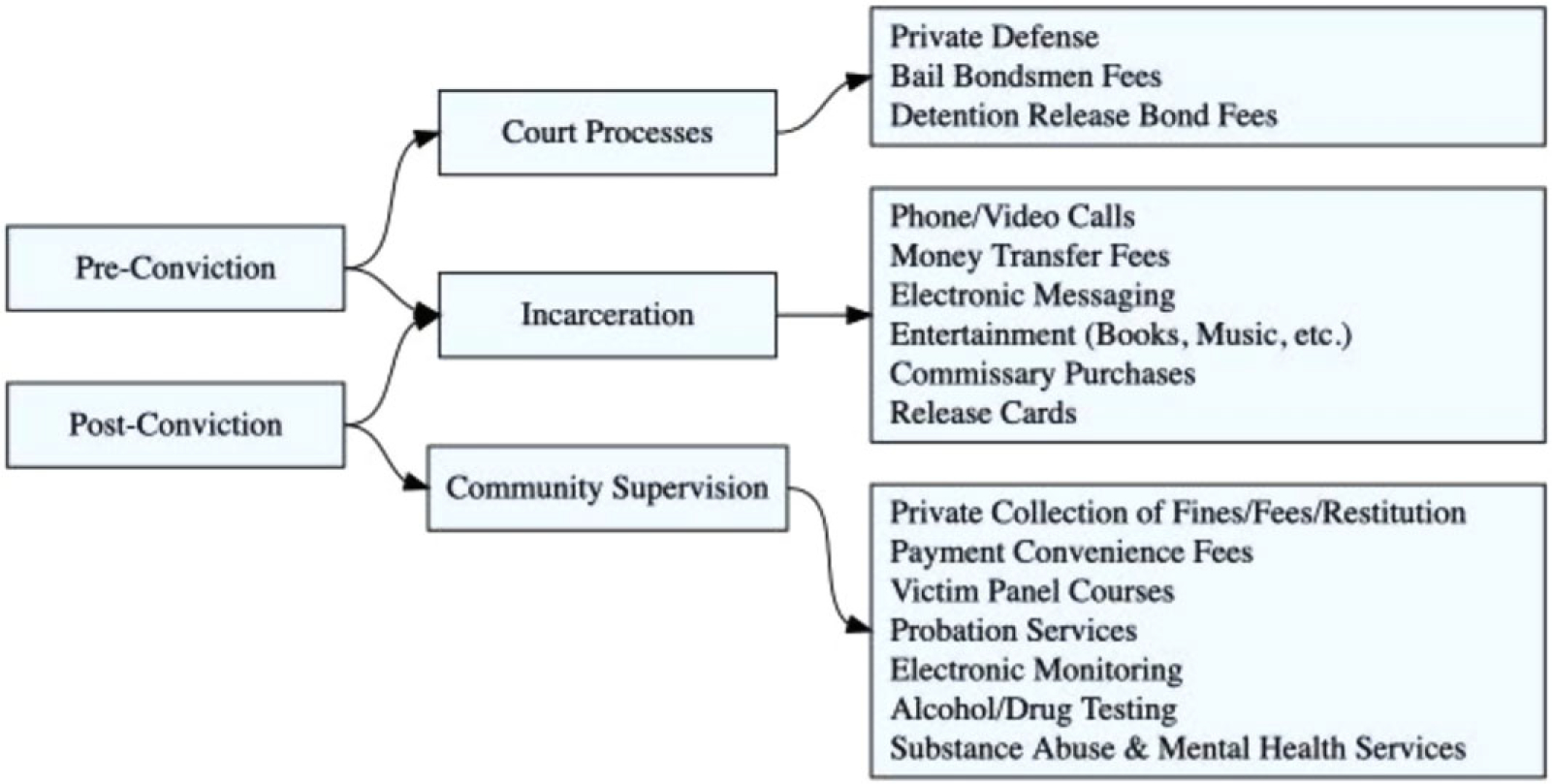

In our review of the various private services that operate within different systems of justice, our findings highlight the wide scope of these public–private partnerships. In Figure 1, we have outlined three broad levels of the justice system at which people face costs from private entities (what we call cost points). These cost points include charges during (1) the court process, (2) incarceration (both pre- and postconviction), and (3) supervision and/or release. Although individuals may have the choice in whether to pay for some of these services, in many cases, usage is mandated by the law, court order, or internal practice. Thus, companies gain profit through the forced participation of individuals who are entangled with the various justice systems in the United States.

FIGURE 1.

Examples of private entity’s justice system cost/revenue points

2.1. Preconviction court process

Private cost points begin almost immediately upon interaction with systems of justice. These moments that follow arrest or citation are when people are faced with financial charges related to court processes and predetention in jail. People who are arrested have the choice to seek out a private defense attorney; the data, however, show that only 18% and 34% of people in state and federal courts, respectively, hire a private attorney (Harlow, 2000). It is important to acknowledge that choosing to pay for a private defense attorney is only a choice for those with adequate fiscal means. Private attorneys can generate a great deal of money from people who are arrested and then prosecuted. Some attorneys require a retainer of a set amount of money that could range from $3,500 to $4,500 and in addition charge an hourly rate for court appearances. It is for this reason that many individuals choose representation by a public defender. In many jurisdictions across the United States, however, people who are eligible for public defense as a result of their indigence are required, via practice or court order, to pay some or all of their public defender fees. Harris (2016) found in an analysis of state statutes that two thirds of states allow public defense costs to be imposed on defendants. Some counties in Washington State charged up to $1,356 for public defender services (Harris, 2016, p. 43). These fees can be costly and consequential for people who are poor and require legal counsel.

Another cost point as a result of an arrest, and one that is nondiscretionary, is the requirement to post bail. Under certain circumstances, a judge may determine a person is a threat to community safety or at risk of not returning to court, and the payment of a monetary amount is required for a person to be released from jail. Many scholars have pointed out that bond and bail systems are frequently not established according to security issues, but they are imposed as a matter of routine (Mamalian, 2011). A great deal of public and political attention has turned to cash money bail systems, which indicates that the practice is reminiscent of “modern day debtors’ prisons” (Gambino & Jacobs, 2018). In such instances when a person or his or her family can pay cash to post bail, then a person can be released. When a person does not have access to enough money to be released from jail, however, he or she must seek out a private bail bondsman company. The bondman will require a certain percentage of the bail (usually 10%) to be given as compensation. The financial collateral could be a car or a house deed given to the bondsman. This company will then pay a portion of the bail to the court in exchange for the person to be released with assurance that he or she will attend all required future court hearings. If the person absconds, then the bondsman will take the collateral. The entity makes a profit by keeping the 10% of the bail, which is treated as a nonrefundable fee, as well as by confiscating property that was temporarily deeded to the bondsman when a person does not meet all requirements of the court.

In another context, when a person is arrested and suspected of being in the United States as an undocumented citizen, he or she is frequently transferred to federal immigration detention centers. Gilman and Romero (2018) examined the role of monetary bond requirements for an individual’s release from immigration detention centers. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention facilities regularly set bonds averaging $7,500. In another study, Ryo (2016) found the mean bond rates differed by judges and ranged from $10,667 to $80,500. To post bond, people rely on intermediary companies that work with bail bond companies. Such companies charge “premium payments” based on the total amount of the bond, a service fee, and a global positioning system (GPS) device installation and tracking fee. Libre by Nexus, a company that provides these “services,” advertises that the average amount is ~20% of the bond amount.1

From the moment individuals enter any type of justice system in the United States, they face numerous costs. Even for those who are not charged or sentenced, the price for simply navigating their way through the system can be high. These cost points can have major impacts on people’s lives even before their cases are resolved. For those who ultimately face legal sanctions as a result of their charge, these prices can grow exponentially.

2.2. Pre- and postconviction incarceration

A second major set of cost points exists whenever a person is incarcerated. Companies have commodified many services and resources in prisons and jails that provide basic necessities for hygiene and nutrition, as well as those that help individuals maintain contact with their family and friendship networks. Whether individuals are in jail as they await their trials, or in prison serving their sentences, they are faced with a menu of charges. These include costs to make high-priced phone or video calls to friends and family members, purchase marked-up items at the commissary, send electronic messages to loved ones, or buy tablets that allow incarcerated individuals to purchase additional books and magazines or listen to music. In our extended example later in this article, we discuss a leading prison technology company, JPay, and the ways it has partnered with state prison facilities to provide these services to people who are incarcerated.

In addition to these services, another product local jurisdictions are increasingly relying on private companies to provide are prepaid release cards. These plastic debit cards are digitally preloaded with people’s money. When people use the cards to access their own money, they are charged several types of fees, which are automatically deducted from the original balance. The money placed on the card ranges from cash confiscated at the time a person is arrested to money earned while incarcerated. Some jurisdictions use these prepaid release cards for persons solely arrested, not even prosecuted or convicted, as a means to manage the cash money they had on their person at the time of arrest. Furthermore, in some jurisdictions, when someone is released from a jail or prison sentence, any money left on the “books” is transferred to these prepaid cards (Diallo, 2015; Gupta, 2016).

Private companies offering these services suggest that they relieve jail and prison staff of “the burden of managing money inside the facilities.”2 Under the notion of saving money, jurisdictions enter into contracts with private companies to outsource the financial accounting practices to private businesses that manage the cash and charge maintenance and transaction fees for use of the card. When cards are inactive or not being used, the maintenance fees are continually charged until the amount on the card is fully depleted. Thus, the local jail, county, or state correction facility’s accounting functions are transferred to private entities at no cost to the public; instead, all costs are transferred to people who are incarcerated. As with the previously mentioned “services,” the private companies are allowed through public contracts to generate profits from people who make contact with our systems of justice.

2.3. Postconviction community supervision

The third bucket of privatized cost points connected to the U.S. systems of justice are costs associated with people’s formal sentences imposed by judges. These costs can include fees associated with the collection of court-imposed monetary sanctions, programs that the courts require people to enter into, privatized probation supervision, electronic home monitoring, alcohol and drug testing and monitoring, and private substance abuse and mental health services. In most instances, once a judge imposes a sentence that requires any of these services, a person must enter into a consumer-type relationship with a private entity, pay for the services, and show the court ongoing proof of service receipt and completion. When people are unable to pay for these services, they can be found in violation of their sentencing agreement and receive jail time as punishment (Harris, 2016).

In a similar way to the release cards, many jurisdictions transfer the public good of justice management and accounting to private entities for fiscal-related sentences. For example, at sentencing or citation, local and state courts mandate people to pay court user fees, fines related to offenses, restitution to victims, surcharges, and interest (Harris, 2016). Some city, county, and state jurisdictions have developed in-house public collection agencies to bill, accept payment, and reallocate monies once paid. Many jurisdictions, however, contract with private collection agencies to manage individuals’ court-imposed debt. These companies are allowed via the public contracts to charge an additional collection fee or percentage to the principal amount of the court-sentenced sanction. For example, in Washington State, by legal statute, private companies can charge up to an additional 50% of the principal for the collection “services” (RCW 19.16.500).

Another iteration of this type of public–private relationship is the reliance of local jurisdictions on private companies to supervise people who have been placed on probation. The most egregious form of this practice involves people being placed on private probation, charged a certain amount for an infraction or offense, and mandated to pay a monthly fee toward both their monetary sanction and the cost of probation. Frequently, private companies apply any payment toward their services first, and if any amount is left over, it is applied to the court debt. In this scenario, however, frequently people are only able to make a small payment toward the private probation costs, much less any payment toward their initial court debt. As such, people become ensnared in a cycle of probation payment amounts with the financial inability to pay off their monetary sanctions and at times are even jailed for their failure to pay in full their probation fees (Edelman, 2017; Human Rights Watch, 2014).

3. TWO CASE STUDIES OF HOW COSTS ARE CHARGED AND GENERATED

In the previous section, we outlined the various cost points of where private entities enter into systems of justice to manage public services and impose costs on people who make contact with courts, jails, and prisons. In a dearth of research, scholars have theorized, documented, and examined these public–private relationships. Next we closely examine two examples of private profiting in public systems to begin to understand how these relationships and outcomes exist.

3.1. Seattle Municipal Court and DUIs

Seattle Municipal Court has the largest caseload of any trial court in Washington State (City of Seattle, 2016). Charges of driving under the influence (DUI) are highly common and extremely expensive to defendants. In Washington, even though judges impose a variety of mandatory monetary sanctions for DUIs, they can waive discretionary fees with a waiver of indigence. The city of Seattle contracts with a private collection service, Harris and Harris, Ltd., for collecting payment for the remaining mandatory obligations. Harris and Harris, Ltd. is based in Illinois and provides collection services for courts across the country (Harris and Harris, Ltd., n.d.). The contract allows this company to add on collection fees that range from 14.95% to 21.85% depending on whether the account is new or transferred, as well as a $10 precollection plan “set-up fee” (City of Seattle, 2017).

In addition to fines and fees, judges impose a variety of conditions on drivers who receive DUIs, which they must comply with to be allowed to drive. In adhering to these conditions, people face a multitude of costs charged by private firms that may not be initially understood when in a courtroom. Furthermore, the requirement for defendants to use only court-approved companies can negate the benefits of competition and price reduction that privatization claims to provide.

Unlike most courts in Washington State, it is common for prosecutors at Seattle Municipal Court to request that people accused of a DUI post bail and install an ignition interlock device (IID) on their vehicle as a condition of release (Burg, 2008). For people who are convicted, this IID requirement can last multiple years depending on the number of previous DUIs. In addition to state fees charged by the Department of Licensing (DOL) to receive an ignition interlock license, individuals must pay fees to obtain a Statement of Responsibility (SR-22) from their car insurance provider, which not all insurance companies issue. The car insurance premium increases for a person charged with a DUI and for those who are convicted. The cost of insurance increases can run thousands of dollars (Kuo, 2014).

In some cases, people who are accused of DUIs may also be required to participate in electronic home detention (EHD). This pre- and postadjudicatory requirement involves calling supervision monitors to obtain permission to leave the house each time they wish to travel and requires constantly wearing a monitoring bracelet. Under a state-wide contract, Seattle Municipal Court contracts with Sentinel, LLC to provide EHD. EHD can cost $7.20 to $18.25 per day in addition to installation, orientation, service calls, and removal costs (City of Seattle, 2018). The contract states that the contractor must provide an offender-funded program. This particular company pioneered the offender-funded model, advertising that it “allows Sentinel to provide all of its monitoring services at little or no cost to the agencies” and “has placed more offenders through offender-funded programs than the rest of the monitoring industry combined” (City of Seattle, 2018, p. 191). Simply being identified as indigent does not qualify an individual for free monitoring. Thus, this widely used model is built on the premise that those who are subjects of the criminal justice system should bear all its costs.

Drivers are responsible for paying the costs of an IID from one of the six Washington State–approved manufacturers (Washington State Patrol, n.d.). These private firms charge fees for installation, monthly calibration, removal, and transfer to another vehicle. Depending on the type of vehicle, costs can vary, with newer cars tending to cost more. One of the most commonly used companies, Smart Start, estimates that installation costs $70 to $150 per car, calibration fees cost between $60 and $150 per month, and removal costs from $50 to $100.3 This company provides discounts on the installation, monthly fees, and removal for referrals from attorneys and public defenders. Drivers need to be able to access service centers, which may also drive up prices.

In Washington State, drivers also pay $20 per month into an Ignition Interlock Device Revolving Account. Drivers pay directly to their IID manufacturer or service provider, which remits the fee to the Department of Licensing, keeping $0.25 of the fee (RCW § 46.20.720). Since August 2012, these funds provide $80 a month to the IID provider of indigent drivers (Washington State Department of Licensing, 2018). Per Washington State law, indigence is defined as receiving public assistance, involuntarily committed to a public mental health facility, being unable to pay for the anticipated cost of court counsel, or making less than 125% of the current federally established poverty level (RCW 10.101.010). The need for such a fund suggests that these IID costs are expensive to the extent that people may not be able to meet their court obligations.

Since 1985, an individual charged with a DUI in Washington State can petition the court for a deferred prosecution if there is a diagnosis of drug or alcohol dependency or mental health issues (RCW 10.05). This involves adhering to restrictions for 5 years, including a two-year treatment plan. If the person complies with all of the conditions, at the end of the 5 years, the charges are dismissed and the guilty plea will be replaced with a not guilty plea. A deferred prosecution can only be granted once in a lifetime. As part of a deferred prosecution, however, a person must enroll and comply with recommended treatment conditions and pay for all the costs of treatment and 2 years of active probation. Seattle Municipal Court offers probation and judges can choose to waive the $25 per month fee if an individual has a waiver of indigence. The drug or alcohol dependency or mental health issues become a part of the person’s legal record. Deferred prosecutions for DUIs exist in several states, such as Alabama, Arkansas, and some counties in Florida, but the requirements can differ highly.

For a person to be in compliance with the conditions of a deferred prosecution, they must complete Alcohol and Drug Information School (ADIS, typically $110 to $150), a 1.5-hour DUI Victim Impact Panel (typically $40 to $60), drug and alcohol assessments ($75 to $250, higher costs apply to interpreted services, with some places accepting insurance), mandatory treatment ($100+ per session), urine analyses to test for compliance with the abstinence condition ($15 to $30 per test), and breathalyzer (BART device) or Secure Remote Continuous Alcohol Monitoring (SCRAM, $8.50 to $9 per day; City of Seattle, 2018; Family Law CASA, n.d.). These services must be provided by court-approved companies. With some of these conditions applying for years, the costs can escalate quickly.

Unlike publicly provided services, poverty typically does not qualify an individual for a waiver for most of these costs. A few not-for-profit organizations provide sliding scale fees for some low-income defendants, although these organizations are limited in number and scope. For example, one nonprofit (New Traditions, n.d.) provides free services to adult women who are low income or eligible for a medical coupon. People must also attend group meetings, typically Alcoholics Anonymous twice a week. Although these group meetings are free, it can further decrease the time people need for family responsibilities, employment, and health maintenance.

The Seattle Municipal Court example is illustrative of how private companies have entered justice system markets to provide goods that courts mandate individuals to purchase. For some services, there are only a handful of court-approved vendors, which provides little incentive for the private entities to lower their costs. Furthermore, programs such as deferred prosecution are meant to be rehabilitative, yet are only accessible to those wealthy enough to obtain treatment from private providers. While discouraging people not to drive under the influence of mind-altering substances benefits society, the system currently in place further advantages people who can afford both the financial costs and time constraints to have the charges ultimately removed from their records.

3.2. Case study of a prison tech company

One way in which private companies make profits through the justice system is by selling services to people who are incarcerated. Corporations increasingly contract with prisons to offer technology-based communication and entertainment services to those behind bars. The Washington State Department of Corrections (DOC) contracts with one of the largest prison tech companies in the United States: JPay Inc. Originally offering money transfer services for inmate accounts, JPay quickly expanded its offerings to include “a variety of corrections-related services.”4 Washington State prisons offer many of JPay’s services, including money transfers, e-mail, video visitation calls, and music players. Therefore, Washington offers a useful case study for exploring the partnership between correctional institutions and private tech companies.

The primary service JPay offers is the management of inmate financial accounts. In most prisons, people who are incarcerated have special accounts that are funded through their work in prison industries and/or through deposits from their loved ones. These accounts allow people to buy convenience items from the prison commissary, make phone calls, and purchase other services that are offered inside the prison. The Washington DOC allows loved ones to post money to people’s accounts by bringing a cashier’s check or money order in person to the prison or sending it through the mail. If families cannot easily reach the facility for in-person transfers, or if the money needs to be deposited quickly, individuals may also deposit money online using services offered by either Western Union or JPay. Western Union allows money to be deposited online, over the phone, or in person. Money sent through Western Union, however, may only be deposited into a person’s general spendable account and cannot be specified for special accounts such as those dedicated to postage, medical expenses, educational expenses, or media purchases. Alternatively, posting money to inmate accounts using JPay’s online system allows loved ones to put money into both a person’s general fund as well as the various subaccounts. Thus, JPay is the quickest and most flexible option for funding those who have been incarcerated.

Online money transfer services are convenient, but there is a price for this convenience. Both Western Union and JPay charge a fee depending on the amount of money transferred through their systems. In addition, people can only purchase many of JPay’s services (such as tablets, e-mails, and music) using funds that have been placed in a person’s “JPay Media Account.” Although JPay offers the ability to transfer money to a person’s general fund, these funds may not be used to purchase JPay services, which means that the company not only generates profit from the transfer of money to media accounts, but also it guarantees that money will be used to purchase its services only. In some states, tech companies may also charge a service for maintaining active inmate financial accounts, allowing them to generate a profit at three different points in the purchase of inmate resources and amenities.

Some of the main resources that may be bought from an inmate’s JPay media services are newer forms of communication. Historically, prisons have offered phone services and traditional “snail mail” for prisons to communicate with their social networks (Jackson, 2005). As the new technologies of the digital age continue to transform how we communicate, there have been increasing calls to allow these technologies inside the prison. It has been argued that these new forms of communications could improve incarcerated individuals’ ability to maintain social bonds and provide them with exposure to technology that will assist in reentry adjustment when they are released (Hopkins & Farley, 2015). Prisons have been slow to adopt these technologies, however, because of concerns about cost and security. Private technology companies have stepped in to address these concerns by offering to manage these services and take on the responsibility of maintaining secure servers for their use. In exchange, prisons are provided with a consistent source of revenue through commissions on the use of these communication tools.

The main communication service that JPay offers in Washington prisons is video visitation. This is a two-way video call that can be done through one of JPay’s kiosks inside the prison. This kind of call allows individuals to see their family members on the kiosk’s video screen and their family members to see them on their devices. The establishment of video visitation technology inside the prisons has been seen as an important way to increase visitations for individuals whose families are far away from the prisons. Video calls, however, are significantly more expensive than regular phone calls. The rate for a video visitation call in a Washington State prison costs $7.95 for 30 minutes compared with $3.30 for a regular 30-minute phone call. Another new communication service JPay offers is electronic messaging. Although prison staff still screen these messages, they are a quicker and more secure form of communication than traditional mail. The pricing for e-messages is less straightforward as it requires individuals to purchase JPay “stamps.” These stamps can then be exchanged for using e-mail, in which “each typed page of text costs 1 stamp and each attachment costs 1 stamp.”

Finally, JPay offers a tablet that is specifically designed for use by incarcerated individuals. These tablets are designed to offer a safe way to deliver digital goods to people who are incarcerated. With applications preprogramed on the tablet (and limitations imposed by the correctional facility), JPay tablets may offer e-messaging services, recreation (such as eBooks, music, and games), and educational programs. In Washington State facilities, the tablet seems to function primarily as a media player. Individuals may purchase a music-playing tablet for their loved ones for $50.00. Once people have their JPay Player, they can purchase music from JPay kiosks for $3.50 per transaction.

The entrenchment of JPay services within the state of Washington’s correctional system highlights an increasing trend in correctional privatization, namely, the ways in which large companies corner the market for services within these systems. In many states, companies are contracted as the sole provider of communication and technology-based services for many correctional facilities. This means that the company that is contracted by a correctional institution (or for an entire correctional system) is granted the monopoly of the “customers” within that institution. These companies are therefore guaranteed revenue off of these services and face no day-to-day competition within the institutional boundaries. In addition, many of their services require the installation and maintenance of hardware that is unique to that company, which makes it difficult, and costly, for jails and prisons to switch providers.

What has resulted from these arrangements is a market that restricts serious competition. Large companies can offer enticing contracts to prisons and jails (often by eating up-front costs of installing hardware) and can expand their operations to a large number of justice systems. In fact, JPay has contractual agreements within 35 state and local jurisdictions, as well as with the District of Columbia. For example, in Arizona, JPay provides services within 14 community supervision offices, 19 department of corrections inmate deposits, and 1 county jail. In California, JPay provides services with 1 federal institution, 35 department of corrections and rehabilitation sites, and 4 county jails. And, in Florida, JPay has contracts with 148 state prison facilities, 2 county jails, and 1 parole and probation location. JPay is extensively coupled with a large and growing number of justice system sites across the United States. Although JPay is not the only company that provides these kinds of services, the market is nearly dominated by only a handful of companies (Neate, 2016).

In addition to these dynamics, the private corrections industry has seen an increased consolidation of services. Even when smaller telecommunications or prison-tech companies can develop, they are often quickly bought by the larger industry firms. In fact, in 2015, JPay itself was bought by Securus, the largest provider of prison security technology in the country (Securus Technologies, Inc., 2015). The consolidation of a variety of justice system services raises new questions about the entire market operation of the corrections industry. It also raises interesting questions about the monopolization of captive markets, and the process by which local and state officials decide whether, when, and how to enter into contracts with prison-tech companies, and if and how these relationships are monitored and evaluated.

4. THINKING ABOUT PRIVATE PROFIT IN A PUBLIC SYSTEM

We are just beginning to understand the extent to which for-profit companies generate money from their engagement with local, state, and federal judicial and correctional systems. The proliferation of public–private partnerships within the justice system follows a similar trend of privatization in other public domains, including child welfare services and public benefits management (Hatcher, 2016). Scholars have linked this increased privatization of public systems to a lack of faith in the ability of the government to manage these complex issues and the belief that private companies can offer similar, if not better, services at a cheaper cost to taxpayers (Enns & Ramirez, 2018; Schichor, 1995).

This pattern is clear to see within the field of punishment. An increased focus on crime control in the late twentieth century led to the development of more punitive philosophies of justice and the over-burdening of the criminal justice system. At the same time, it seemed that the public had a decreasing faith in the ability of correctional systems to rehabilitate and properly socialize individuals (Garland, 2001). In light of these developments, governments began to explore how they could honor the nation’s new “tough-on-crime” philosophy while managing the operational costs of charging and incarcerating a growing number of citizens. Many policy makers viewed partnerships with private companies as an important avenue for addressing these needs, and over time, more and more responsibilities of the justice system have been offloaded to private entities. This developing “corrections–commercial complex” emphasized the “market-driven dimensions of criminal justice,” allowing officials to frame legal systems as self-sustaining and revenue generating (Lilly & Deflem, 1996). It is for this reason, perhaps, that public discourse around the privatization of justice-related services has shifted to focus more heavily on instrumental factors of the system (such as cost and quality) and away from the ethical considerations of this privatization (Burkhardt, 2016). Although systematic considerations are important, key ethical questions remain around how privatization impacts those involved. How do profit-driven motives of private companies, embedded within the day-to-day operations of justice activities, affect individuals who must pay for these private services?

One of the key considerations for using private resources is the ability to offset the costs of running institutions of justice. Given the exponential growth of the U.S. systems of justice over the past 40 years, the country may have reached a point at which local and state funding cannot keep up with the fast pace of system needs. Harris (2016) in her study of the sentencing of monetary sanctions found that one administrator, of a small and impoverished county, argued it was much less costly in terms of time and money to contract with a private collection company to collect all fines, fees, and restitution sentenced to people in her courthouse. Contracting with private companies allows governments to offload the responsibility of managing and providing services onto the private sector. Proponents of privatization argue that this offloading of costs is essential for managing the burden of rising punitive costs, especially for smaller jurisdictions with limited economic resources. These kinds of operational and capacity-oriented concerns have become central to the debate over the privatization of criminal justice systems (Kim & Price, 2014).

Furthermore, one might suggest the privatization of services, similarly to court-sentenced monetary sanctions, is another layer of punishment people who have been found to break the law should face. Might these additional costs be serving a retributive, deterrent, or even rehabilitative benefit to punishment by requiring people to be financial accountable for the punishment they receive? Indeed, many policy makers have emphasized varying degrees of “offender-funded” justice as a necessary part of the experience of punishment in the United States (Lindsey, Mears, & Cochran, 2016). The contractual arrangements that many systems make with companies provide a source of revenue that helps to recover the cost of the sanctions the system imposes. Contracts often stipulate that the court or prison receive commission from the sales of the private services. For example, Washington DOC policy states that inmates should make every effort to “contribute to the cost of privileges” and that DOC staff are to “make every effort to maximize individual inmate contributions to payment for privileges” (RCW § 72.09.470). This is accomplished by funneling the commissions from the sale of contracted services into a designated offender betterment fund (OBF) that is used to fund program staff, stock prison supplies, and purchase recreational activities for prisoners (Washington DOC § 200.200). It seems that buying from private companies is the primary funding source for other important inmate programs and recreational activities.

We can also see how these arrangements provide an incentive for increased mandating of punishments that involves the use of private products. As more individuals use these services, more revenue is generated for the operation of the criminal justice system. Private companies also allow judicial systems to expand the types of punishments available to them. As technologies related to community supervision and communication evolve, governments may not be nimble enough to provide these complex systems and instead rely on specialized companies. Indeed, critics have pointed out that these partnerships can “unnecessarily expand the web of social control” that is available to public justice institutions (Lindsey et al., 2016).

It is through these kinds of arrangements and arguments that a government may shift the cost of expanding court and correctional processes away from the public pocketbook and onto the backs of the justice system involved and their families. Although the impacts of these shifting costs are not completely understood, researchers have suggested that the additional financial burdens of being involved with the justice system, coupled with family separation during confinement and the collateral consequences related to conviction and postrelease, create insurmountable burdens for people to move forward positively with their lives postconviction (Harris, 2016). Many important empirical questions remain—to what extent, if at all, do policy makers and practitioners think about these additional costs in relation to the practice of punishment? Is there an underlying theoretical argument for imposing additional costs for services on justice-involved individuals and their families, or do people primarily rely on efficiency and cost-effective arguments to support these private–public arrangements?

Theoretically, we could also spend time thinking about the private–public partnerships as an example of how new markets are continually developed under the U.S. system of capitalism. The “services” and “products” developed are new forms of technologies, but also amenities governments and individuals have gone without in prior eras of criminalization. Yet, increasingly, JPay tablets, DUI interlock devices, and video visitation are common and expected services offered within the U.S. system of justice from arrest to community supervision. The private companies have successfully developed and marketed these new needs to both agents managing justice systems and individuals processed, housed, and controlled by the system. Our focus in this article was to provide an example of the continual expansion of capitalism into new realms, if you will, the cracks and crevasses of our criminal justice system, with no accountability or oversight.

In divergence to this perspective that views the private as invading the public, scholars in contrast have theorized these relations as consistent partnerships throughout U.S. history between the state and private entities, that in fact, these boundaries have always been penetrated and masked in certain ways (Mayrl & Quinn, 2016, Quinn, 2019). Throughout the nineteenth century, the U.S. criminal justice system had been tethered to private industry via convict leasing programs that “leased out” the convicted, rightly and undeservedly, to private companies for use of their labor (Blackmon, 2008). These programs generated revenue for the state and covered the cost of confinement of the convicted. Furthermore, private companies have been embedded within prisons to access people’s labor at low cost to produce goods to sell at market value or at a reduced rate to state and local jurisdictions (Elk & Sloan, 2011). Thus, another perspective could view these partnerships within systems of justice as a contemporary iteration of the long-standing partnership between government systems and private corporations.

5. RESEARCH TRAJECTORY

Needless to say, there is a great amount of empirical analyses and theoretical development required to understand better the ways private entities are partnering with and have become embedded within U.S. systems of justice. We know very little about the direct impacts of the privatization of justice practices on the people who are involved in these systems. A great deal of research findings have shown that most people who make contact with systems of justice are disproportionately unemployed, undereducated, poor, and managing mental health and substance abuse issues (James, 2004; McKay, Comfort, Linquist, & Bir, 2016; Pager, 2007; Peterson & Krivo, 2010; Pettit & Western, 2010; Pew Charitable Trusts, 2010). We can surmise that these additional private costs can create undue burden.

In a parallel body of relevant research, scholars have examined how court-imposed monetary sanctions increase the stress, financial instability, and criminal justice engagement for court-involved people (Harris, 2016). Current research, policy, and media attention has been focused on whether jurisdictions should be assessing large fines, fees, surcharges, interest, collection fees, and even engaging in forfeitures to generate funding for state and local funds. In February 2019 the U.S. Supreme Court took up this issue with Timbs v. State of Indiana (586 U.S. 2019). In this case, the petitioner’s 2012 Land Rover LR2, purchased with his father’s life-insurance proceeds for $42,000, was seized by the state of Indiana because he had used it to drive to a location to sell undercover officers two grams of heroin. The maximum allowable fine for his drug conviction was $10,000. Timbs pleaded guilty to one count of dealing and one count of conspiracy to commit theft. He received a sentence of 6 years, with the first year being on home detention and the remaining 5 years on probation. He was also sentenced to $1,203 for police costs, an interdiction fee, court costs, a bond fee, and a drug and alcohol assessment via the probation department (Tyson Timbs and A 2012 Land Rover LR2 v. State of Indiana, 2018). This case raised the question of whether the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process clause incorporates the Bill of Rights protection from excessive Fines Clause in the Eighth Amendment and should be applied to the states. One of the key issues raised is the extent to which all citizens should be free from the imposition of excessive fines and fees, as well as the degree at which jurisdictions should be levying high costs on a population, the criminal justice population, which is primarily poor. In a unanimous decision the Court found that the excessive fines clause does apply to states. In a separate, but concurring decision, Justice Thomas even linked the practice of excessive fines in contemporary times to the abusive 19th-century practice of Black Codes that unfairly convicted African Americans and imposed excessive fines and fees to ensnare them for life. We raise an additional overlapping question: Should private entities be able to enter the criminal justice space and generate profits from this population? If the assessment of legal debt can have such negative impacts, what additional burden do private costs create in the lives of individuals who are required to pay for them?

In this article, we have provided two examples of private corporations that enter into business with our systems of justice. First, we examined the city of Seattle’s use of for-profit companies for the enforcement of DUI sentences. This provides a clear example of the kinds of public–private partnerships that increasingly exist in community supervision processes across the country. In fact, we see myriad court-ordered conditions that require individuals to pay for private services. Inability to afford the prices that private providers set can make the difference between a clean and a tarnished criminal record, which has consequences for educational, housing, and employment opportunities. Our second example demonstrates the ways private companies target incarcerated populations. These arrangements have created a circumstance in which incarcerated individuals and their families are forced to pay private companies to remain in contact with their loved ones and provide them with amenities.

Several sets of research questions are to be explored. First, how are people who face these additional costs managing to make ends meet? Are there trade-offs to make these payments that affect individuals and their family members? How might these additional costs inhibit people’s ability to desist from offending and disengage with our systems of justice? Do these additional costs limit or negatively affect people’s connections with their family members and friends, decreasing community ties and social bonds? Future research should be aimed at investigating how private companies affect the livelihood and functioning of individuals who have made contact with systems of justice.

Second, researchers should also investigate the public–private contracts. How do state and local codes structure these partnerships? How much profits, or mark-ups, are private entities allowed to impose on people living in jails and prisons and under supervision in their communities? How much profit is being made throughout the entire range of cost points? Legal ethicists should examine the fairness and legality of these private–public partnerships, particularly when the consumer base is frequently captive.

In a third set of questions, the monopolization of public justice system services by private companies across the United States is examined. Local and state justice systems seem to have an increasing reliance on allowing private companies to serve as vendors, and these vendors seem to establish strong and long-lasting footholds within these systems. These footholds have allowed a limited number of large companies to dominate this service market. Monopolization could be examined in many different ways. First, we need to understand better the extent of competition in private markets for justice-related services. How many companies exist? How might they vary, and what dimensions are local and state jurisdictions deciding to enter into contracts with these companies? Furthermore, we need to explore how such companies promote and situate themselves to dominate the market. That is, what are the “selling points” of the companies to entice new jurisdictions to shift from public provision of goods to allowing private companies to provide the services? Are companies promising to provide better services that save jurisdictions money? Are jurisdictions considering any extra costs experienced by system-involved individuals and their families? And, are any evaluations being performed to determine whether these benefits are, in fact, occurring? From an economic perspective, the criminal justice system is a unique market environment and how companies operate within these systems must be thoroughly examined.

A fourth line of inquiry should be used to explore the extent to which private–public partnerships are a necessity. A more thorough study, with a full detailing of examples of private justice system cost points, should be performed. A case study within one municipal, county, or state jurisdiction could be performed to understand better the types of companies providing services and the parameters of the arrangements, costs, and profits. One could then explore under what circumstances it might make sense to have jurisdictions outsource certain type of services. Some services might be better suited to outsourcing such as drug treatment or mental health services. Are certain provisions available that might save public money and/or be better performed by private companies such as collection units, in-house “amenities,” various components of probation supervision, and treatment services? Yet, privatization may show a negative impact when operating in other capacities. Should criteria regarding financial prudence and quality of service be used to inform the creation of private–public partnerships? If so, what are the standards practitioners and policy makers should establish to determine when and with whom they should enter into a contract for private services?

The case for privatization lies on the premise that market forces will lead to more efficient, lower cost service delivery. Yet contracts and actual costs are often not transparent to the public to determine whether this is the case. Nor is it clear what incentives exist that might lead to socially undesirable and unethical outcomes, or what are the potential harms of these types of partnerships to individuals and their families and to the legitimacy of systems of justice. Supposing there are savings to taxpayers through privatization, are there other costs and consequences we should consider? What burdens does this system place on people who cannot afford its “services”?

6. POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The ability of researchers to answer these important questions lies in the ability to gather complete and accurate information about the partnerships between justice institutions and private entities. Currently, many of the contractual agreements between these parties are not readily available and may only be gathered through slow, and sometimes expensive, public data requests. Even then, many states have not weighed in on how much information private companies in these arrangements are required to divulge to the public (Eisen, 2018). Local and state jurisdictions should mandate in their codes that private contracts are publicly available. Additionally, policy makers should require more transparency from both companies and justice system departments on how much money is saved and generated from these partnerships.

An important step in expanding this transparency may be in determining whether the services they are offering are functional equivalents to services that the government can offer. Currently, corporate law gives companies a broad range of protections from sharing company processes and finances. Determining that a company is serving a public function, however, opens them up to a set of stricter regulatory laws that are applied to government bodies (Tartalgia, 2014). We would suggest that state and federal courts directly take up the question on whether these private companies are governmental equivalents and more directly outline requirements for transparent reporting.

In addition to increasing requirements for financial reporting, governments should also take a closer examination of regulations around the pricing structures of these services. The market structure of these services creates the potential for exploitative pricing, considering that individuals who use these services have very little choice in whether to purchase from those companies. The author of a recent report found that the prices of prison amenities and digital music downloads was higher than the market average for these same services outside of prison (Raher, 2018). Governments should examine these pricing structures and create policy that prevents companies from using exploitative pricing structures.

There have been recent movements to decrease the high cost of private services within public jurisdictions. In 2014, the Supreme Court of Georgia ruled that private probation companies could not extend court-imposed ordered supervision for misdemeanor convictions past what was initially ordered by the court. Thus, the practice of private companies extending supervision for lack of a person’s ability to make payment was found illegal (Tatum, 2015). In July 2018, the New York City Council passed legislation to no longer charge people in jail costs for phone calls, and the policy specifically stipulated that the jurisdiction could not generate any revenue from phone calls. As such, via social movements that hold local and state governments accountable for their actions, and through litigation of practices involving private companies’ apparent illegal extension into justice system practices, changes can be made.

We argue that a great deal of further research findings highlighting and investigating these practices is needed to provide a better foundation and theoretical development for our understanding of this private profiting in public systems. There is still much to learn about the consequences of privatizing public systems of justice. In particular, for people who are incarcerated or who do not have the ability to pay the added price, does the privatization of public services impact rehabilitation, strain social networks, or impose financial burdens on families? Understanding the impact of this discreet private incursion of our systems of justice is crucial as more and more “products” and “services” in the criminal justice system become sources of corporate profit.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES

Alexes Harris is the University of Washington Presidential Term Professor in the Department of Sociology. In her book, A Pound of Flesh, she was the first to examine the criminal justice sentencing practice of fines and fees and the related consequences for people with felony convictions.

Tyler Smith is a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Washington. His research is focused on the assessment of legal fines and fees, privatization of the criminal justice system, and the role of technology in prisoner reentry.

Emmi Obara is a doctoral candidate at the University of Washington in the Daniel J. Evans School of Public Policy and Governance. Her research is focused on recidivism and cycles of imprisonment.

Footnotes

For example, see librebynexus.com. We learned of this company from Nina Rabin’s presentation at Yale Law School on April 6, 2018.

From the Numi Financial webpage advertising inmate trust management and release cards: http://www.numifinancial.com/inmate-trust-fund-management-c1q6v

Information about Smart Start’s pricing structure can be found on its website at https://www.smartstartinc.com/blog/ignition-interlock-cost/

All information about JPay, including the various services offered as well as details about its partnerships with state justice systems can be found on its website: https://www.jpay.com/AboutUs.aspx

REFERENCES

- Blackmon D (2008). Slavery by another name: The enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Burg J (2008). Seattle Municipal Court DUI guide. DUI Washington. Retrieved from https://www.duiwashington.com/seattle-municipal-court-dui-guide [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt BC (2016). Private prisons in public discourse: Measuring moral authority. Sociological Focus, 47, 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- City of Seattle. (2016, September). Request for Proposal RFP No. MUNI 3630: City of Seattle municipal court collections. Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- City of Seattle. (2017, November). Purchasing services. Contract for collection agency services for Seattle Municipal Court Contract #0000003630. Seattle, WA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- City of Seattle. (2018). Contract #4409 with Sentinel Offender Services, LLC for electronic monitoring of offenders. Seattle, WA: Purchasing Services. [Google Scholar]

- Corrections Corporation of America. (2015). Annual report, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.annualreports.com/HostedData/AnnualReportArchive/c/NYSE_CXW_2015.pdf

- Diallo A (2015, April 20). Release cards’ turn inmates and their families into profit streams. Aljazeera America. Retrieved from http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2015/4/20/release-cards-turn-inmates-and-their-families-into-profit-stream.html [Google Scholar]

- Edelman P (2017). Not a crime to be poor: The criminalization of poverty in America. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eisen L-B (2018). Inside private prisons: An American dilemma in the age of mass incarceration. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elk M, & Sloan B (2011, August 1). The hidden history of ALEC and prison labor. The Nation. [Google Scholar]

- Enns PK, & Ramirez MD (2018). Privatizing punishment: Testing theories of public support for private prison and immigration detention facilities. Criminology, 56, 546–573. 10.1111/1745-9125.12178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Family Law CASA. (n.d.). Drug & alcohol evaluations/assessments/treatment. Retrieved from https://www.familylawcasa.org/helpful-resources/drug-and-alcohol-services/drug-and-alcohol-assessments/

- Garland D (2001). The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporary society. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gambino L, & Jacobs B (2018, July 25). Bernie Sanders’ case bail bill seeks to end “modern day debtors’prisons.” The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/jul/25/bernie-sanders-cash-bail-bill-seeks-to-end-modern-day-debtors-prisons [Google Scholar]

- Gilman D, & Romero LA (2018). Immigration Detention, Inc. Journal of Migration and Human Security. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2311502418765414 [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A (2016, August 1). The financial firm that cornered the market on jails. The Nation. Retrieved from https://www.thenation.com/article/the-financial-firm-that-cornered-the-market-on-jails/ [Google Scholar]

- Harlow CW (2000). Defense council in criminal cases (Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Harris A (2016). A pound of flesh: Monetary sanctions as a punishment for the poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Harris and Harris, Ltd. (n.d.). We understand government. Retrieved from http://www.harriscollect.com/government/

- Hatcher D (2016). The poverty industry: The exploitation of America’s most vulnerable citizens. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins S, & Farley H (2015). E-learning incarcerated: Prison education and digital inclusion. The International Journal of Humanities Education, 13(2), 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. (2014, February 5). Profiting from probation: America’s offender funded probation industry. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/02/05/profiting-probation/americas-offender-funded-probation-industry [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SJ (2005). Mapping the prison telephone industry. In Herivel T& Wright P (Eds.), Prison profiteers: Who makes money from mass incarceration. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- James DJ (2004). Profile of jail inmates 2002. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble D, & Cowhig M (2016). Correctional population in the United States, 2016. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, & Price BE (2014). Revisiting prison privatization: An examination of the magnitude of prison privatization. Administration and Society, 46(3), 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo J (2014). True cost of a DUI in Washington after insurance increases. Nerdwallet. Retrieved from https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/insurance/true-cost-dui-washington-insurance/ [Google Scholar]

- Lilly R, & Deflem M (1996). Profit and penality: An analysis of the corrections-commercial complex. Crime & Delinquency, 42(1), 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey AM, Mears DP, & Cochran JC (2016). The privatization debate: A conceptual framework for improving (public and private) corrections. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 32, 308–327. [Google Scholar]

- Mamalian CA (2011). State of the science of pretrial risk assessment. Washington, DC: Pretrial Justice Institute. Bureau of Justice Assistance, U.S. Department of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrl D, & Quin S (2016). Defining the state from within: Boundaries, schemas and associational policymaking. Sociological Theory, 34, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- McKay T, Comfort M, Lindquist C, & Bir A (2016). If family matters: Supporting family relationships during incarceration and reentry. Criminology & Public Policy, 15(2), 529–542. [Google Scholar]

- New Traditions. (n.d.). Start your recovery. Retrieved from http://www.new-traditions.org/?page=help

- Neate R (2016). Welcome to Jail Inc: How private companies make money off US prisons. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jun/16/us-prisons-jail-private-healthcare-companies-profit [Google Scholar]

- Pager D (2007). Marked: Race, crime and finding work in an era of mass incarceration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RD, & Krivo L (2010). Divergent social worlds: Neighborhood crime and the racial-spatial divide. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit B, & Western B (2010). Incarceration and social inequality. Daedalus, 11 (Summer). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Charitable Trusts. (2010). Collateral costs: Incarceration’s effect on economic mobility. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn S (2019). American bonds: How credit markets shaped a nation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raher S (2018). The company store: A deeper look at prison commissaries. Washington, DC: Prison Policy Initiative. Retrieved from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/commissary.html [Google Scholar]

- Revised Code of Washington. § 10.05. Deferred Prosecution—Courts of Limited Jurisdiction.

- Revised Code of Washington. § 10.101.010. Definitions.

- Revised Code of Washington. § 19.16.500. Public bodies may retain collection agencies to collect public debts—Fees.

- Revised Code of Washington. § 46.20.720. Ignition interlock device restriction—For whom—Duration—Removal requirements—Credit—Employer exemption—Fee.

- Revised Code of Washington. § 72.09.470. Inmate contributions to costs of privileges—Standards. [Google Scholar]

- Ryo E (2016). Detained: A study of immigration bond hearings. Law & Society Review, 50, 117–153. [Google Scholar]

- Schichor D (1995). Punishment for profit: Private prisons/public concerns. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Securus Technologies, Inc. (2015). Securus Technologies Inc. completes transaction to acquire JPay, Inc PR Newswire. Retrieved from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/securus-technologies-inc-completes-transaction-to-acquire-jpay-inc-300122095.html [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia M (2014). Private prisons, private records. Boston University Law Review, 94, 1689–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Tatum G (2015, January 8). Misdemeanor fee-based probation tolling ends after Georgia Supreme Court Ruling. Atlanta Progressive News. Retrieved from http://atlantaprogressivenews.com/2015/01/08/misdemeanor-fee-based-probation-tolling-ends-after-georgia-supreme-court-ruling/ [Google Scholar]

- Tyson Timbs and A 2012 Land Rover LR2 v. State of Indiana. (2018). Petition for a writ of certiorari to the Indiana Supreme Court. Retrieved from https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/17/17-1091/33939/20180131162915070_Petition%20for%20a%20Writ%20of%20Certiorari%20Timbs%20et%20al%20v%20State%20of%20Indiana.pdf

- Washington State Department of Corrections. § 200.200. Offender Betterment Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Washington State Department of Licensing. (2018). Ignition interlock driver license (IIL). Retrieved from https://www.dol.wa.gov/driverslicense/iil.html

- Washington State Patrol. (n.d.). Ignition interlock. Retrieved from http://www.wsp.wa.gov/driver/duiimpaired-driving/ignition-interlock/