Abstract

The Ferguson Report became a watershed moment for understanding the costs and consequences of the monetary sanctions system for communities of color. Since that time, myriad reports, studies, and commissions have uncovered evidence that suggests that Ferguson, Missouri, was not an outlier but rather part of a broader set of systems throughout the country that relied on increasingly punitive assessment and collection strategies for revenue. The growth and expansion of these systems continue to have detrimental and widespread consequences. In this article, we aim to shed light on the current state of monetary sanctions as the full scope and damage of the monetary sanctions system come better into focus on the national, state, and local level. We explore the legal challenges and legislative reforms that are attempting to reshape the landscape of monetary sanctions and lessen the burden on economically disadvantaged individuals and communities of color.

Keywords: monetary sanctions, criminal justice system, debtors’ prison, legal financial obligations, LFOs

INTRODUCTION

Criminal justice reform is on the minds of many. In fact, the United States Congress is currently considering the First Step Act, House Bill 5682, which has bipartisan support. Among other issues, the legislation bans the shackling of pregnant and postpartum women, retroactively applies the Fair Sentencing Act, lowers lifetime mandatory minimums for people with prior nonviolent felony drug convictions, and provides identification cards to every person released from custody. Although this legislation addresses many concerns about inhumane treatment during incarceration, sentencing disparities, and reentry problems, the legislation does not address the prominent and disturbing issues capturing mainstream media headlines, such as state-sponsored violence and the intrinsic connection between poverty and social control in the United States. The death of Michael Brown and the aftermath in Ferguson, Missouri, was a watershed moment that shed light on the unequal systems embedded in municipal court systems and upheld by law enforcement and court actors. The resulting Ferguson Report detailed a punitive and racist system of law enforcement practice and municipal court procedures that targeted the economically disadvantaged African American residents of Ferguson with numerous and costly court fines and fees. The unfair and burdensome monetary sanctions system and its impacts on communities of color in Ferguson spurred discussions about the pervasive yet largely unexplored use of the monetary sanctions system to provide revenue for local and state governments.

The report prompted investigations into the policies, practices, and laws in other states, cities, and jurisdictions that undergird the practice of assessing and collecting court-related fines, fees, and costs. At the heart of these explorations into the complex set of systems that constitute these court costs were questions about whether Ferguson was an outlier or whether we could see similar patterns in other locales (Harris 2016, Henricks & Harvey 2017). Researchers have suggested the monetary sanctions system is part and parcel of larger policies, procedures, and legislative shifts that constitute a punitive racialized system of processes and sanctions (Miller et al. 2018). The growing empirical literature suggests that Ferguson’s reliance on fines and fees generated through the criminal justice system is not unique but rather a more widespread practice than previously realized (Henricks & Harvey 2017).

REVENUE GENERATION

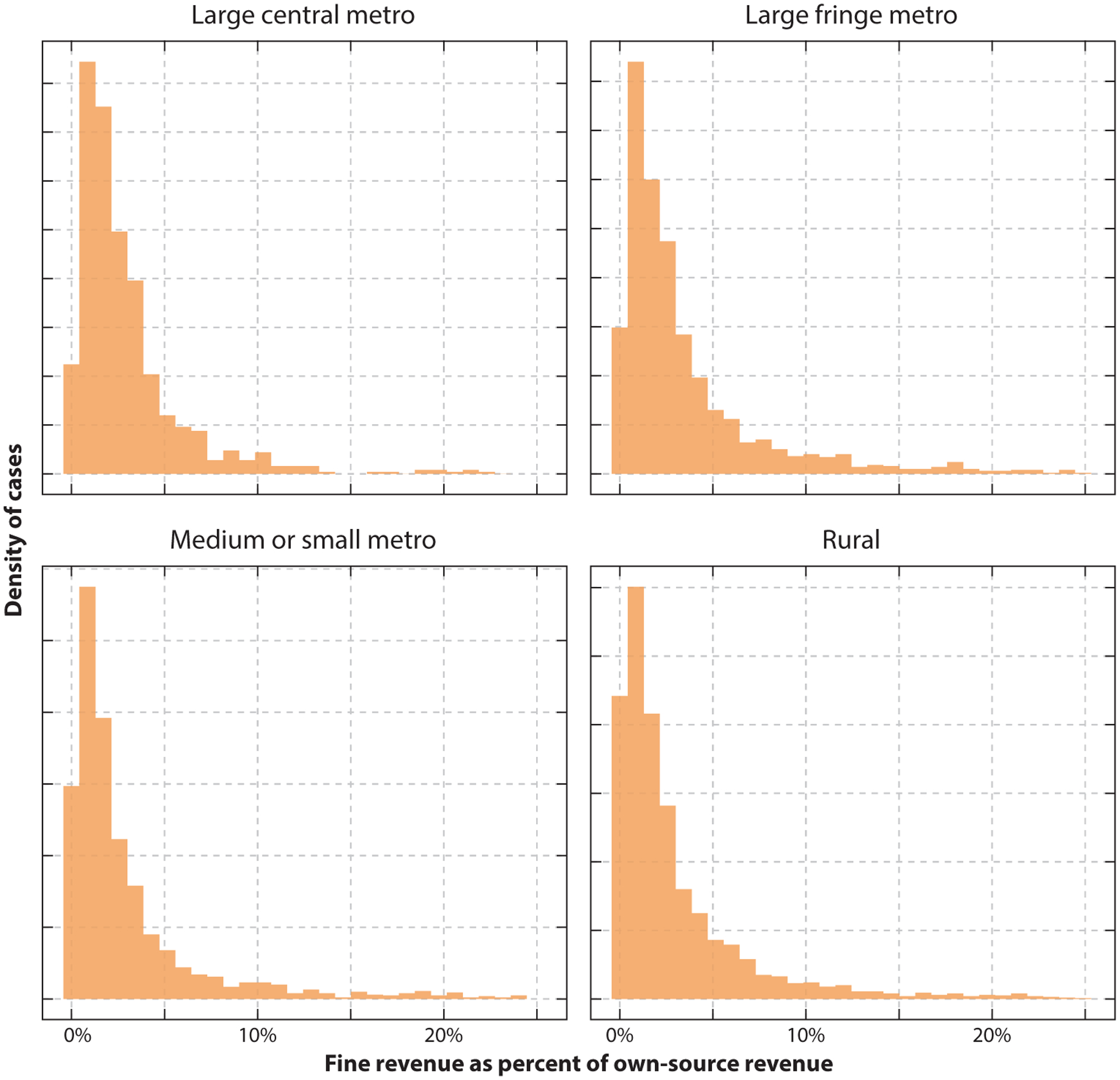

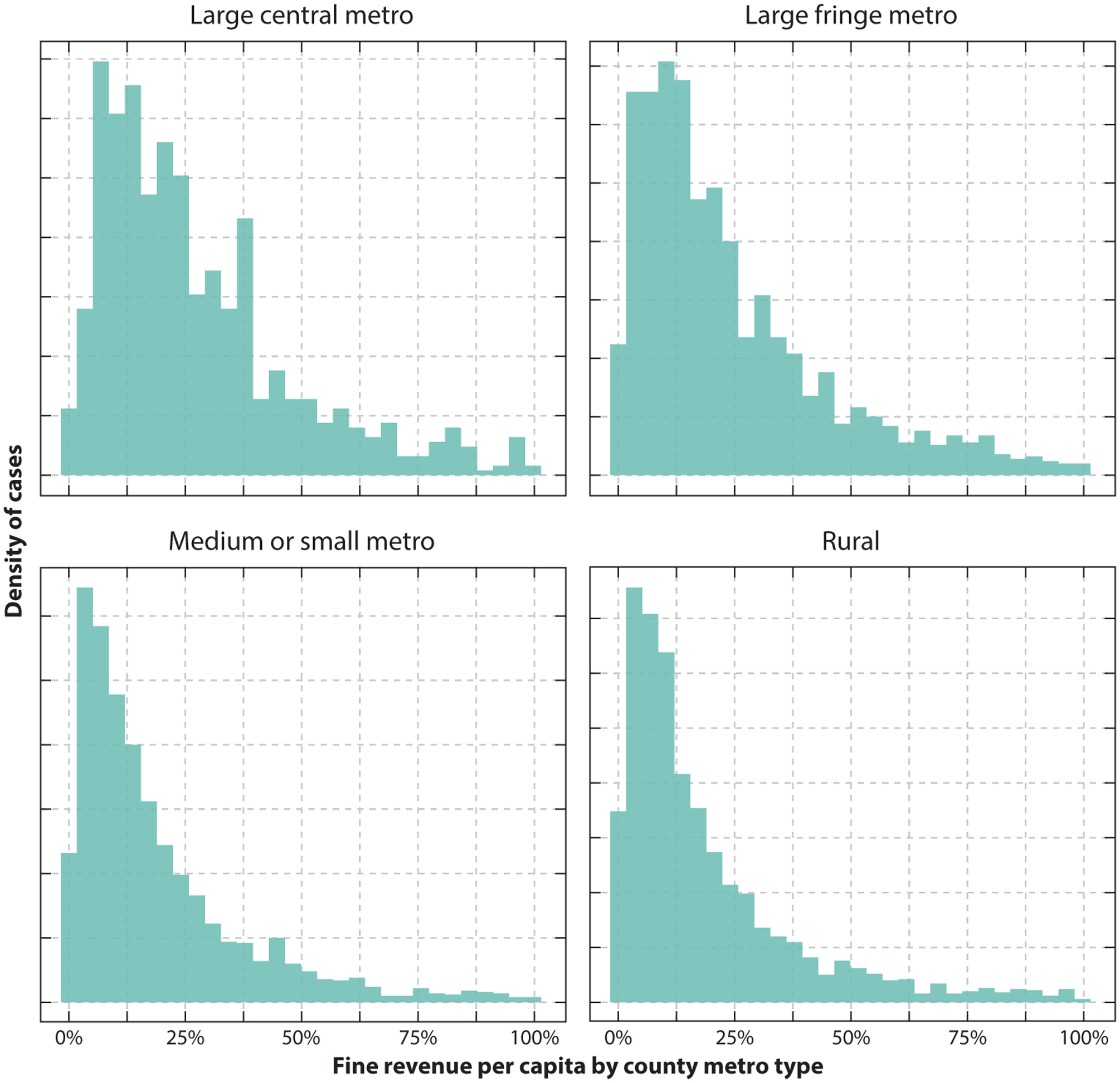

Ferguson’s reliance on criminal justice revenue is far from unique. We provide a brief illustration of the scale of the revenues generated by local governments from the criminal justice system with data from the Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finance (US Census Bureau 2012). Table 1 displays the revenues per capita and revenues as a percentage of own-source revenue for municipal governments in the United States by county metropolitan type. We display both the mean value and values at the 95th percentile. On average, in 2012, cities in large central metropolitan areas collected approximately $40 per capita from fines and forfeitures, whereas rural municipalities collected approximately $25 per capita. Fines and forfeitures tend to make up a larger share of own-source revenue in suburban large fringe municipalities when compared with municipal governments in other metro types. We display histograms of the distribution of fines and forfeitures revenue per capita in Figure 1 and fines and forfeitures revenue as a percentage of own-source revenue in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Fines and forfeitures revenue in US municipalities, 2012

| Metro type | Revenue per capita, mean | Revenue per capita, 95th percentile | Revenue as percent of own-source revenue, mean | Revenue as percent of own-source revenue, 95th percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large central metro | $40.61 | $108.09 | 3.3 | 9.72 |

| Large fringe metro | $38.55 | $133.82 | 4.32 | 16.54 |

| Medium or small metro | $25.84 | $86.31 | 3.71 | 15.03 |

| Rural | $24.81 | $87.06 | 3.61 | 13.34 |

Figure 1.

Fines as a percent of municipal own-source revenue by county metro type (2012) (data from US Census Bureau 2012).

Figure 2.

Municipal fines and forfeitures revenue per capita by county metro type (2012) (data from US Census Bureau 2012).

In 2012, Ferguson reported that it generated approximately $2.2 million in revenues from fines and forfeitures, or approximately $105 per capita. These fines and forfeitures revenues accounted for more than 20% of the city’s own-source revenue for that year. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, Ferguson is not the only municipal government with criminal justice revenues at these extreme levels. In 2012, 355 municipalities (with populations of more than 500 residents) collected at least $100 in fines and forfeitures revenues per capita, and 208 municipalities generated at least 20% of their own-source revenues from fines and forfeitures. Of these, 54 were cities in large central metropolitan areas, 137 were cities in large fringe metropolitan areas, 109 were cities in medium or small metropolitan areas, and 119 were municipalities in rural areas. Criminal justice revenue dependence is a widespread phenomenon, and many municipal governments are at or above the troubling levels reported by the Department of Justice (DOJ) in Ferguson.

The results suggest that Ferguson is not an isolated case, but that in fact these policies, practices, and procedures have been fully entrenched in the criminal justice and law enforcement systems in various municipalities, disproportionately affecting individuals and communities of color (Harris 2016, Sances & You 2017, Soss & Weaver 2017). The DOJ investigation of Ferguson, along with studies in other states (Harris 2016, Harris et al. 2010, Martin et al. 2018), brought the monetary sanctions system to light; however, such revenue-generating systems had been working silently in the background for decades.

Buried deep in state and city statutes, the procedures for assessment, collection, and enforcement of court fines, fees, and costs have been formulated to compensate for increasing budget shortfalls for overexpanded court and incarceration systems. The stakeholders that benefited from the assessment and collection of these sanctions ballooned, including those far outside the court system, from the public school system to health care. These external and internal pressures facilitated the expansion of the monetary sanctions system, with states and municipalities increasing the types and amounts of fines, fees, and costs assessed. The growing reliance on monetary sanctions revenue then necessitates collection procedures and practices that range from wage garnishment and tax levies to driver’s license suspensions to recoup costs. Because these sanctions were often levied on those who did not have the means to pay, more punitive sanctions, such as arrest warrants and incarceration, were implemented to dually punish and collect on legal debt. Such practices represent increased burdens on those who were the most affected in Ferguson: the poor and communities of color.

The disproportionate impact exists beyond Ferguson, with those most likely to be targeted for contact with the criminal justice system being assessed exorbitant amounts for infraction, misdemeanor, and felony convictions. Without the ability to pay, poor communities and communities of color are more likely to be subject to the pervasive collections and sanction procedures for failure to pay their outstanding legal debt, compounding the consequences that result from contact with the system. Such practices foment increased distrust of law enforcement and the criminal justice system, as well as extending the time that individuals spend under surveillance. Monetary sanctions and the accrual of legal debt may prompt individuals to engage in system avoidance to avoid further contact with the system and punitive collection procedures, such as wage garnishment, tax liens, and driver’s license revocation. Existing research on system avoidance suggests that individuals who have had contact with the criminal justice system are more likely to avoid formal institutions and organizations, resulting in increasing exclusion and stratification (Brayne 2014). The expanded reach of the monetary sanctions system may be yet another mechanism that prompts individuals with outstanding legal debt to not engage in the formal labor market, financial institutions, and health care systems, among others, or to be locked out of these institutions as a result of legal debt.

The exploration of other Fergusons then necessitates a discussion of the ways in which this overreach of the criminal justice and monetary sanctions systems is being dealt with in legislative and legal circles. The acknowledgment of the existence of many Fergusons demands a set of diverse and complex responses to the building and sustaining of these systems that further disadvantage already poor communities and communities of color.

NATIONAL MOMENTUM FOR REFORM ON FINES AND FEES

The issue of legal financial obligations (LFOs) or monetary sanctions has gained a great deal of public attention over the past several years. One of the first academic analyses of the subject from a sociological perspective was published in 2010 and highlighted the imposition of fines and fees on defendants by criminal courts and outlined their social and legal consequences (Harris et al. 2010). In November 2014, the first report of its kind about municipal fines and fees in St. Louis County, Missouri, was released by the ArchCity public defenders. This report highlighted the large amounts of the LFOs that were assessed to residents by cities in St. Louis County (ArchCity Defenders 2014). Following the killing of Michael Brown, an unarmed African American man who was accosted by police for jaywalking in Ferguson, Missouri, the DOJ issued a similar report outlining the city’s use of fines and fees. In part, the study found that the Ferguson municipal court imposes “substantial and unnecessary barriers to the challenge or resolution to municipal court violations” and “unduly harsh penalties for missed payments or appearances” (US Dep. Justice Civ. Rights Div. 2015).

The DOJ, along with the White House, held a joint convening in December 2015 titled “A Cycle of Incarceration: Prison, Debt and Bail Practices” in light of reports that highlighted the difficulty poor people experienced as a result of fines and fees (US Dep. Justice 2015). Following these meetings, in March 2016, the DOJ issued a “Dear Colleague” letter to judges across the nation. The letter outlined seven principles relating to the sentencing of fines and fees. Key points reminded judges that they should not incarcerate people for nonpayment of LFOs before determining whether they have the ability to make payments, that they should consider alternatives to incarceration for nonpayment, and that they must safeguard against unconstitutional practices by all court officials (US Dep. Justice 2016). Furthermore, the DOJ, under the Office of Justice Program’s Bureau of Justice Administration (BJA), issued a call for the “Price of Justice Grants,” in which five states were selected to study their practices around LFOs. The states include California, Louisiana, Missouri, Texas, and Washington (US Dep. Justice 2016). In 2016, the BJA also created and sponsored the National Task Force on Fines, Fees and Bail Practices, composed of the Conference of Chief Justices and the Conference of State Court Administrators. The aim of the taskforce is to assess the impact of fines and fees on people who are indigent and draft model statutes and court rules guiding the use of this sentencing option. With the widespread nature of the use of monetary sanctions as revenue, it is imperative to explore the legal challenges, legislative reforms, and policy implications that are shifting the landscape on fines and fees.

Legal Challenges

The release of the Ferguson Report became a watershed moment in the conversation surrounding fines and fees, with the report detailing the role of municipal courts in the unjust and burdensome implementation and collection of monetary sanctions in Ferguson, Missouri. The revelations from that report of municipal courts and law enforcement acting as revenue-generating agents rather than arbiters and enforcers of the law caused state and local jurisdictions to rethink the policies, practices, and procedures that had been implemented to assess monetary sanctions for infractions to felony offenses. The increasing attention toward monetary sanctions and their impact has resulted in calls for reform, as well as legislative and legal challenges to lessen the negative effects of fines, fees, and surcharges levied for criminal justice contact. Proposed changes have targeted the most detrimental assessment and collections procedures that have been enacted. National and state task forces and committees were subsequently convened to investigate the state of monetary sanctions and potential reforms that could be enacted to stem the burden on poor communities and communities of color.

The National Task Force on Fines, Fees and Bail Practices was commissioned in 2016 to assess the state of monetary sanctions in the nation’s court systems and to provide guidance for an equitable and efficient system that emphasizes access, fairness, and transparency as part of the monetary sanctions system. The recommendations suggest that these systems throughout the country should focus on equal treatment, acknowledging the disparate impact of these sanctions and their resulting legal debt on those who are economically disadvantaged and communities of color. The report emphasizes the need for free counsel provided for indigent defendants and the elimination of driver’s license suspensions. It focuses on key principles that should be adopted in regard to fines and fees, including increasing judicial discretion in the assessment and waiving of fines and fees, standardizing ability-to-pay inquiries, and ending the practice of incarceration for nonpayment—so-called pay-or-stay practices. Many of these tenets have guided additional reports on monetary sanctions, providing a framework for legislative and administrative changes throughout the country.

The US Commission on Civil Rights released a report in 2017 focusing on the scope, impact, and constitutionality of imposing monetary sanctions on low-income people of color, finding that fines and fees were often being levied to target economically disadvantaged communities of color (US Comm. Civ. Rights 2017). These findings dovetailed with Harris’s (2016) research in her book, A Pound of Flesh, which suggests that such targeting amounts to the assessment of “poverty penalties,” whereby low-income citizens, often citizens of color, are fined for offenses relating to their economic status. The Commission details the expansion of fine and fee structures and punitive collections procedures that are often cited as the main mechanisms targeting economically disadvantaged individuals and keeping them in a cycle of mounting debt and ongoing surveillance.

In 2018, the American Bar Association (ABA) adopted ten guidelines on court fines and fees, detailing recommendations for reforms on federal, state, and local levels (Am. Bar Assoc. 2018). The recommendations range from limiting assessed fines and fees and eliminating incarceration and other such disproportionate sanctions for failure to pay to mandating ability-to-pay hearings and limiting the use of coercive collections procedures. These proposed reforms directly target the policies and practices that have resulted in hardships for those subject to these monetary sanctions. In line with the ABA and other such institutions calling for reform, state and local jurisdictions have begun to implement such reforms to alleviate the burden that monetary sanctions place on often economically and occupationally disadvantaged individuals and communities. These recommendations have set the stage for potential reforms that have played out in legal challenges throughout the country.

The following sections explore the legal challenges and reforms that have resulted from the evolving acknowledgment of these sanctions as disproportionately assessed and burdensome. Advocacy groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union and the Southern Poverty Law Center have sought legal redress not only for individual clients but also for the policies that prove to be increasingly detrimental to individuals and communities of color. This section highlights the main legal shifts from the ability-to-pay and failure-to-pay practices as well as the consequences of nonpayment, highlighting pay-or-stay provisions and the role of private probation and collections companies. Investigating these shifts and changes allows for an ever-evolving understanding of where the state of monetary sanctions stands in terms of practice and procedure, but also where future challenges can be directed to ameliorate the potential and actual damage of court costs, fines, and fees and their impacts. Additionally, these practices and policies represent a complex interlocking system that involves various stakeholders, agencies, businesses, and governmental agencies. This complexity makes the rolling back and dissolution of predatory assessment and collection procedures a colossal undertaking.

Ability to pay.

States such as New Jersey and California have been instrumental in passing safeguards to lessen the assessment of sanctions and their attendant effects. One of the main targets for reform has been implementing standards on the ability to pay and mandating hearings to ensure that such considerations are taken into account. In many jurisdictions, the ability to pay is not systematically factored into the assessment of monetary sanctions, leaving indigent and low-income defendants open to additional sanctions and the threat of incarceration for failure to pay. The ABA suggests that minimum standards should consider factors such as the receipt of public assistance, housing instability, transportation access, and fines and fees in other courts, as well as financial obligations to dependents. States have since implemented these standards and practices to alleviate the burden on low-income and indigent defendants. The New Jersey Supreme Court Committee’s report on Municipal Court Reform mandates ability-to-pay hearings for those who have failed to pay fines. Such hearings then facilitate the setting of a payment schedule or consider sentencing alternatives. California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office released a report in 2016 similarly calling for fines to be based on the ability to pay to avoid the attendant consequences of nonpayment. At the center of many of the current legal challenges to the assessment and cost of monetary sanctions is the absence of systematic and consistent policies and practices to assess the ability to pay. Without such safeguards, individuals are often beset with fines, fees, and court costs that far outstrip their available financial resources.

The majority of the current legal challenges to monetary sanctions focus directly on the absence of policies and practices that assess the ability to pay as a key mechanism for punishing indigent defendants. The model for ability-to-pay hearings was set by State of Washington v. Blazina (2015), which held that trial courts are obligated to conduct inquiries into defendants’ ability to pay before assessing monetary sanctions. According to the ruling, such inquiries should involve important factors such as indigent status and other impending legal debts. In a recent case, State of Washington v. Ramirez (2018), the issue at hand was not only a consideration of the current inability to pay but also an assessment of future ability to pay and other important factors that may inhibit the payment of monetary sanctions. The judge in the original case did not question Ramirez on his current or future ability to pay when assessing the amount of fines and fees associated with his conviction. The ruling suggests that individualized inquiries about indigence, other outstanding legal debt, and other financial circumstances, such as employment history, assets, and living expenses, need to be addressed to alleviate the burden of legal debt on economically disadvantaged defendants.

The class action lawsuit Bell v. City of Jackson (2015) dealt with the practice of jailing defendants for the inability to pay fees related to traffic violations. In addition, individuals were charged extra fees for not paying their outstanding balance in full, without inquiries into their ability to pay. The settlement requires that the city of Jackson review defendants’ ability to pay on a case-by-case basis and no longer incarcerate for the inability to pay. The ruling in Cain v. City of New Orleans (2017) expressly cited the use of a debtors’ prison scheme to disadvantage poor citizens of Louisiana. The Orleans Parish Criminal District Court had failed to assess the ability to pay court fines and fees, resulting in disproportionate financial burdens for indigent defendants and defendants of color. In addition, these defendants were often subject to incarceration for the inability to pay their outstanding debt.

In Johnson v. Jessup (2018), the practice of revoking driver’s licenses for traffic convictions in North Carolina was at issue. The complaint focused on the absence of a formal hearing to determine ability to pay and a lack of reasonable options to avoid license revocation. The plaintiff asserted that the state of North Carolina presumes that defendants are willful in their nonpayment but do not inquire into the ability to pay in the process of assessing monetary sanctions. As a result of this lawsuit, among others, district court judges in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, consult bench cards that serve as a reminder to assess the ability to pay before monetary sanctions are assessed (Ewing 2017). Implementing this type of reform throughout the country would aid in ensuring a fairer and more equitable assessment of court fines and fees, as well as mitigating the consequences that arise with the failure to pay outstanding balances.

Failure to pay.

Failure to appear for a hearing or pay for fines and fees has often resulted in stringent penalties for defendants, ranging from additional fines and fees and driver’s license suspensions to bench warrants and incarceration. These penalties have often been levied on those who do not have the means to pay their legal debt, thereby increasing the economic and legal burden that they face for often minor offense charges and convictions. Oftentimes, courts lack a systematic consideration of the ability to pay, which can result in punitive responses to the failure to pay. The inconsistent practices regarding assessing the ability to pay and punitive penalties for the failure to pay can result in substantial hardships for those caught in the vicious cycle of monetary sanctions. For those in economically precarious circumstances, enormous trade-offs often have to be made, for instance, in deciding between paying down debt or purchasing medication or keeping the lights on (Harris 2016). In states and municipalities that incarcerate for nonpayment, however, the costs of both time and money can be especially detrimental. States and local jurisdictions have investigated the practice, finding that the cost of prosecuting for failure to appear or pay is disproportionate to the amount recovered in sanction payments (Laisne et al. 2017). In addition, the potential punishments for failure to pay, ranging from extra surcharges to arrest warrants and jail time, can have detrimental implications for those who have contact with the criminal justice system. The lawsuits address not only the sanctions for failure to pay but also less punitive and costly reforms that can be implemented by court administrators.

The vast majority of current legal challenges focus on failure to pay and its consequences, especially incarceration for nonpayment, as a key point of reform. The resolutions of many of these lawsuits have resulted in changes to policy and practice on the local and state levels. For instance, in Roberts v. Black (2016), the city of Bogalusa, Louisiana, required a $50 extension fee for those who were unable to pay the full amount of their court costs and fines. Those who could not afford the extension fee were often threatened with jail for nonpayment. In addition, those who defaulted on payment were assessed an additional contempt fee. As a result of the settlement, the city discontinued the practice of jailing indigent defendants and the assessment of the extension and contempt fees for those who could not pay their outstanding balances.

Brown v. Lexington County (2017) is an ongoing class action lawsuit in South Carolina centered on the consequences for nonpayment, specifically the use of bench warrants and incarceration. Magistrate judges would offer the ability to set up payment plans without regard to the individual’s ability to pay, thereby subjecting defendants to arrest and incarceration if they failed to make the large monthly payments. As a result of the suit, some judges have voluntarily recalled arrest warrants for nonpayment to decrease the number of defendants jailed for outstanding balances. Similarly, the New Jersey Supreme Court Committee on Municipal Court Operations, Fines and Fees called for a review and recall of all bench warrants for failure to pay that were over 10 years old, regardless of the amount of debt (New Jersey Courts 2018). Such changes help to mitigate the potential for more severe consequences, such as jailing for nonpayment, and thereby lessen the burden on the economically disadvantaged.

The reforms for failure to pay have often taken a two-pronged approach, on the one hand implementing procedures to assess financial ability to pay, and on the other hand allowing for waivers that can decrease the total amount assessed and owed. For instance, in Dade v. City of Sherwood (2016), the focus was mainly on pay-or-stay provisions for nonpayment in Arkansas; however, one of the reforms to result from the lawsuit settlement was the implementation of fee adjustments and waivers for those who could not afford to pay their balances. Waiver programs can offer relief from monetary sanctions at the point of assessment, eliminating the potential consequences of legal debt and nonpayment, including incarceration.

Pay or stay.

One of the most egregious poverty penalties that exists is the practice of pay or stay, or incarcerating people for inability to pay fines and fees. Often, those who have outstanding debt owing to traffic violations or misdemeanor offenses are threatened with jail because they do not have the means to pay at the time of assessment. Courts generally specify a per-day amount that is compensated toward the remaining debt, usually between $10 and $30 per day in jail. The widespread use of this practice to compel payment of outstanding legal debt has prompted scholars, civil rights attorneys, and advocates to declare these modern-day debtors’ prisons (ACLU 2010). Pay or stay has been at the forefront of legal challenges and calls for reform owing to the unconstitutionality of the practice and its widespread implications.

Throughout the country, individual and class action lawsuits have been filed to challenge the practice of pay or stay, arguing on the basis of Fourth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendment violations. In Alabama, Cleveland v. City of Montgomery (2013) was a substantial case that mandated the cessation of pay or stay and the closure of one of the largest private probation companies in the state. In Dade v. City of Sherwood (2016), class action plaintiffs argued that the practice of jailing for nonpayment for hot-check or bounced-check convictions in Arkansas was in violation of the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. The settlement stipulated that the Sherwood court would cease jailing individuals for nonpayment for bounced-check convictions. In addition, the Sherwood court would conduct individual assessments of defendants’ ability to pay and would offer adjustments or waivers for defendants who were in default on their legal debt. Mahoney v. Derrick (2018) was a class action suit filed in Arkansas against a district court judge; the plaintiffs asserted that Judge Derrick’s practices of suspending driver’s licenses and incarceration for nonpayment amounted to an undue burden on poor defendants, creating modern-day debtors’ prisons. Attorneys for the plaintiffs pointed to signs that hung in the district court offices about Judge Derrick’s zero-tolerance policy1 on nonpayment of monetary sanctions as evidence of his punitive attitude toward indigent defendants. In addition, he would issue warrants for those debtors who missed payments, even if they had made arrangements with the court clerks for an extension or if they had made a partial payment. The court found that Judge Derrick was indeed violating the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment and causing undue and disproportionate hardship for indigent defendants.

In Bell v. City of Jackson (2015), jailing for nonpayment of fines resulting from traffic violations was at issue, with plaintiffs arguing that jailing for nonpayment of infraction and misdemeanor convictions was unconstitutional in the state of Mississippi. The settlement mandated that it was unconstitutional to incarcerate for nonpayment and mandated that judges assess the ability to pay monetary sanctions before the assessment of fines and fees. A case that garnered national media attention, Kneisser v. McInerney (2015), revolved around a New Jersey college student who was assessed $239 for littering but could not afford to pay the $200 minimum payment and was threatened with five days in jail. The judge refused to set up a payment plan or offer a community service alternative to incarceration. These cases, among others throughout the country, highlight the mounting legal challenges that question the constitutionality of pay-or-stay practices and their impact on indigent defendants. The punitive ideology of zero tolerance in regard to payment of monetary sanctions underlies the policies and practices that sustain this system of fines, fees, costs, and surcharges, to the detriment of the indigent and economically disadvantaged, as well as communities of color.

Private collections.

The increasing pressure on local jurisdictions to increase revenue streams through collection of outstanding legal debt has led to partnerships with private collections companies. These companies often levy their own set of fees and surcharges to the outstanding balance, compounding the debt, especially for indigent defendants. The federal case of Wilkins et al. v. Aberdeen Enterprizes II, Inc. (2017) names both a private collections company and every Oklahoma county sheriff in what plaintiff attorneys suggest was an “extortion scheme” that jailed indigent defendants for failure to pay (Killman 2017). The suit alleges that the contract between the Sheriffs’ Association and the private collections company made it difficult for indigent defendants to pay their outstanding balances and avoid incarceration for nonpayment. The private collections company would routinely add an additional 30% markup for existing balances and automatically suspend driver’s licenses for nonpayment. According to the lawsuit, the Sheriffs’ Association made more than $800,000 in 2015 owing to their contract agreement with Aberdeen Enterprizes. Currently, in Oklahoma, nonpayment of fines is the fourth most common reason that an individual is in jail (Weill 2017). The outcome of this case could have implications for how the state of Oklahoma handles collections for indigent defendants who do not have the means to pay their outstanding balances. More broadly, however, such legal challenges shed light on predatory collections practices throughout the country.

Driver’s license revocation.

Driver’s license revocations or suspensions occur for several reasons but are commonly the result of charges of driving while under the influence of alcohol or drugs, accumulation of too many points on one’s driving record, non-traffic-related drug offenses, unpaid child support, and unpaid court fines and fees for both traffic offenses and non-traffic criminal convictions (Carnegie & Eger 2009, Salas & Ciolfi 2017). Millions of individuals throughout the United States have had their licenses suspended because of failure to pay their LFOs (Marsh 2017). This type of suspension appears to disproportionately impact poor communities of color. In New Jersey, a 2007 report found that whereas only 17% of licensed New Jersey drivers reside in low-income areas, 43% of suspended drivers do, and most license suspensions are due to unpaid court debts (Carnegie 2007). As cited in Stinnie v. Holcomb (2017), African Americans in Virginia were found to have higher rates of suspended licenses owing to nonpayment and failure to appear. The revocation or suspension of driver’s licenses can impact the ability to work and attend to other daily responsibilities, such as taking children to school or daycare (Edelman 2017). As a result, many choose to drive on their suspended licenses and incur subsequent violations that make it even harder to have their license reinstated (Edelman 2017). This creates a cycle of debt and criminal justice system embeddedness that disproportionally impacts poor communities of color. Of the 2,000 drivers in the District of Columbia convicted of driving with a suspended license in 2011, 80% were African American. Throughout the country, legal challenges have been raised to question this practice and its disproportionate impact on the poor, particularly poor people of color.

Johnson v. Jessup (2018) questioned the practice of driver’s license revocation in North Carolina courts. Johnson learned that his license was revoked for unpaid traffic tickets during a routine traffic stop. His license was reinstated after he paid the outstanding balance; however, he could not pay the additional fees that resulted from the traffic infraction, increasing the possibility of future license revocations. Driver’s license suspension and revocation require defendants to choose between obeying the law and going to work or taking their children to school. Such trade-offs can lead to further penalties, with the suspension of driving privileges making it nearly impossible to earn the money to pay their outstanding debt. Several lawsuits have been filed in Tennessee challenging revocation practices that have resulted in more than 146,000 revocations for failure to pay court costs and only 7% of drivers being able to reinstate their licenses (Oppel 2018). Robinson v. Purkey (2017) is an ongoing class action lawsuit that focuses on the suspension and revocation of driver’s licenses for nonpayment of monetary sanctions. The judge issued a restraining order that restored driving privileges for two of the plaintiffs, concluding that driver’s licenses were crucial to economic self-sufficiency and the repayment of legal debt. In Thomas et al. v. Haslam et al. (2018), the practice of revoking driver’s licenses for failure to pay court costs was found to be unconstitutional. As a result of the lawsuits, Tennessee residents who have suspended licenses for unpaid monetary sanctions qualify for license reinstatement. These legal challenges suggest a recognition by the court of the fact that license suspension or revocation is an extraordinary punishment that directly impacts the ability of defendants, especially those who are poor, to attend to their daily responsibilities.

Private probation services.

To reduce personnel and administrative costs, state and local governments have partnered with private companies to outsource debt collections and probation services. Oftentimes, the public and private entities work in concert, with courts referring individuals who cannot pay their outstanding balance or who default on their loans. Although only a handful of states, including Alabama, Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, and Michigan, currently use private probation companies, they have become an increasingly attractive solution to mounting personnel and administrative costs and fiscal deficits.

In a set of cases adjudicated in Alabama, the practices of a private probation company, Judicial Corrections Services (JCS), were at issue, with defendants being assessed additional fines and fees and subject to incarceration for failure to pay. If an individual pled guilty and could not pay their fines and court costs, they were assigned, by the court, to “pay-only” probation with JCS and were charged a $10 setup fee and $40 monthly supervision fee. The terms of payment were set by JCS and did not take into account ability and means to pay. In addition, JCS retained the authority to deny the implementation of payment plans and to recommend incarceration for nonpayment to the court. The cases of Cleveland v. City of Montgomery (2013) and Ray v. Judicial Corrections Services (2016) brought such practices to light and highlighted the extraordinary burden that these policies place on those who have pled guilty to traffic or misdemeanor offenses.

As a result of this series of lawsuits, JCS was shuttered throughout the state of Alabama. However, there was no shortage of companies to take its place. In Harper v. Professional Probation Services (2017), a private probation company was sued for implementing practices similar to those of JCS in Alabama, including charging a $40 monthly fee for probation services. Similar cases have been adjudicated in other states, such as Georgia and Tennessee, where private probation companies dominate the market for probation services. These legal challenges suggest that there is a greater acknowledgment of the extraordinary burdens that monetary sanctions and resulting legal debt create for indigent and economically precarious individuals. These changes in policy and practice, which are often limited to state and local jurisdictional boundaries, can be seen as a changing tide against the increasingly punitive and wide-sweeping nature of the assessment and collections of monetary sanctions. Although untangling the complex web of state statutes, governmental and private corporate interests, and fiscal demands will not be an easy or quick process, these legal challenges represent movements toward a fairer and more just system, especially for indigent and economically disadvantaged individuals and communities.

Policy Reforms

As a result of this national attention on monetary sanctions and cries for reform, state supreme courts, legislators, and local policy-making councils have clarified and revised laws and practices regarding the sentencing of fines and fees. Local and state jurisdictions have directed their focus to several dimensions of monetary sanctions systems, including creating state taskforces, developing bench cards to inform judges of mandatory and discretionary cost schedules as well as existing law guiding the sentencing assessments of fines and fees, eliminating interest, decreasing and eliminating criminal justice system user fees, decoupling criminal action from motor vehicle violations, and establishing community service provisions.

Creation of fines and fees taskforces.

In addition to the National Task Force on Fines, Fees and Bail Practices, organized by the National Center for State Courts and supported by the Obama Administration via the BJA, states and local jurisdictions across the nation have created taskforces to study and discuss justice practices around the citation and sentencing of fines and fees (Natl. Cent. State Courts 2017). For example, in 2016, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors created a Fines and Fees Taskforce to study “the impact of fines, fees, tickets and various financial penalties, that disproportionally impact the low-income San Franciscans and propose reforms” (San. Franc. Board Superv. 2016). Taskforces like these are important because convened stakeholders have the authority of the local or state jurisdiction to examine court records and understand internally the amount of costs that are cited and sentenced, what is outstanding, and all revenue generated and spent on collection practices. Such analyses both allow a nuanced and broad understanding of jurisdictional monetary sanction practices and can inform policy and legal changes that could better serve low-income citizens who encounter systems of justice.

Bench cards indicating cost schedules and laws.

An increasingly popular way states are thinking about their systems of monetary sanctions is through the development of state supreme court–issued bench cards. These informational, and frequently laminated, sheets of paper outline each state’s mandatory and discretionary fines and fees, as well as any additional surcharges, interest, and collection fees that courts can sentence convicted persons. Courts have created cards for each jurisdictional level within a given state. Furthermore, the cards outline existing state standards for determining willful ability to pay and any additional state guidelines for sanctioning when one states they are unable to make payments as outlined by case law and state statute. The Washington State Supreme Court issued such a bench card in 2015, and the Ohio State Supreme Court issued one in 2016 (ACLU 2014, Wash. State Super. Courts 2015). Similarly, the Texas Office of Court Administration developed a bench card for judicial processes related to the collection of fines and costs (Tex. Off. Court Adm. 2017).

Eliminating interest on nonrestitution fines and fees.

In Washington, House Bill 1783, which went into effect on June 8, 2018, significantly modified the state codes for LFOs. It expanded the number and kinds of LFOs that could be waived owing to a finding of indigence, which is related to annual income, mental health status, and homelessness. It eliminated the accrual of state-imposed interest on outstanding fines and fees; however, interest still accrues on restitution. The removal of interest did not include interest that accrued on convictions prior to June 6, 2018; that is, it is not retroactive, but the new statute includes a pathway for people to apply to have their nonrestitution interest waived or reduced via judge-approved petition. The change in legislation also set priorities for repayment so that any money collected would first be directed as payments to any outstanding restitution for victims.

Decrease or eliminate user fees.

California has been a leader in fine and fee sentencing reform. In 2017, Governor Jerry Brown signed Senate Bill 190, ending the charging of administrative fees to families with youth in the juvenile system. This legislation repealed county authority to charge administrative fees to parents and guardians for their children’s detention, legal representation, probation supervision, electronic monitoring, and drug testing in the juvenile system. Building on this momentum, in mid-2018 the San Francisco Board of Supervisors became the first jurisdiction in the nation to eliminate criminal justice user fees for costs associated with probation, electronic home monitoring, and jail booking fees (San Franc. Board Superv. 2018). And at the same time, Los Angeles County policy makers decided to stop collection of juvenile fees sentenced prior to 2009, eliminating more than $90 million in juvenile detention–related debt (Agrawal 2018).

Decoupling criminal action from motor vehicle violations.

Across the nation, jurisdictions frequently link the failure to pay traffic tickets or court costs or other violation of court sentences with the suspension or revocation of one’s driver’s license. Some jurisdictions have begun to think about decoupling the inability to make court payments from driver’s license suspension or revocation. For example, in June of 2017, California Governor Brown signed a law that included a provision that would discontinue the practice of suspending driver’s licenses as a result of unpaid fines. Along similar lines, in July 2018, a US District Court judge ruled that Tennessee officials were violating the constitution by removing the driver’s licenses of people solely for their inability to pay traffic tickets. The court found that this was a violation of the Equal Protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In response, local officials began reinstating driver’s licenses to people who lost their licenses as a result of their inability to pay their court costs.

The practice of suspending driver’s licenses for unpaid traffic fines and non-traffic-related LFOs has experienced significant changes in some states and jurisdictions owing to policy shifts and litigation. The availability of so-called hardship licenses has been on the rise in several states. Alabama recently passed Senate Bill 55 (2018) to maintain limited driving privileges for drivers with suspended or revoked licenses who do not pose a threat to other drivers. Similar to other jurisdictions that allow restricted licenses, these limited privileges allow drivers to travel to and from work, pick up children, attend school, seek emergency medical care, and get to court-mandated programs and probation or parole offices. However, in some states, like Florida, drivers with suspensions owing to failure to pay civil fines do not qualify for these types of licenses [Florida Code §322.245(5) and §318.15]. Although progress is being made, policy makers and stakeholders should consider how to expand existing policies to alleviate undue burden on poor defendants who cannot afford to pay their LFOs.

In addition to hardship licenses, several states have attempted to alleviate the barrier of high LFOs for license reinstatement by implementing programs such as Arizona’s Compliance Assistance Program (Ariz. State Univ. 2017). This program enables individuals with unpaid traffic fines or court-related debts to get their licenses reinstated after making a down payment and signing up for a reasonable monthly payment plan. Similar programs have been implemented in other states, although some of these seemingly well-meaning programs have not been as effective as hoped in overcoming the disproportionate burden of fines and fees placed on individuals trying to get their licenses back. In response to a report released by the Legal Aid Justice Center as part of their class action lawsuit against the Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles challenging the constitutionality of suspending driver’s licenses for failure to pay court costs, Virginia implemented similar assistance programs to help drivers obtain their licenses in 116 municipalities. Despite the program, reports suggest little to no improvement in helping those in financially difficult positions to access driver’s licenses, and more than 650,000 Virginians currently have their licenses suspended solely for failure to pay.

Community service provisions.

An additional realm of reform related to fines and fees involves the conversion of fines and fees to community service hours. In April 2018, the California Assembly approved legislation that gives courts the discretion to offer convicted persons the option of providing community service in lieu of paying fines. The issue of converting legal debt into community service has been suggested and is common in several states. Some suggest expanding the use of community service in lieu of fines and defining community work service very broadly will reduce high debt loads. For example, Washington State’s most recent legislation allows local jurisdictions to convert court-imposed fines and fees to community restitution service hours.

CONCLUSION

With this article, our aim was to outline the current political landscape of the system of monetary sanctions. We reviewed data from the Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finance to illustrate the large amount of money local jurisdictions generate from citations, fines, fees, and other court costs. We outlined the contemporary legal challenges that citizens and policy advocates have brought to courts across the nation to push back on jurisdictional reliance on monetary sanction revenue, particularly that which is extracted from low-income populations. Finally, we outlined the various ways jurisdictions and states have begun to identify this system as a problem and have created policies and laws to adjust the ways they impose and collect court costs.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

Footnotes

The sign read, “Judge Derrick has a ‘Zero Tolerance’ policy for nonpayment of fine and therefore, if payment is not receipted in the system prior to the end of the month, a nonpayment of fine warrant will be issued with a cash bond for the full sentenced balance, plus the new charge and your DL [driver’s license] will be suspended until such time as your account is paid in full.”

LITERATURE CITED

- Agrawal N 2018. L.A. County to stop collecting old juvenile detention fees, erasing nearly $90 million of families’ debt. Los Angeles Times, October. 9 [Google Scholar]

- Am. Bar Assoc. 2018. Ten guidelines on court fines and fees. Resolut., Work. Group Build. Public Trust Am. Justice Syst., Am. Bar Assoc., Chicago, IL. https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/images/abanews/2018-AM-Resolutions/114.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Am. Civ. Lib. Union (ACLU). 2010. In for a penny: the rise of America’s new debtors’ prisons. Rep., Am. Civ. Lib. Union, New York. https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/InForAPenny_web.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Am. Civ. Lib. Union (ACLU), Ohio Chapt. 2014. Collection of fines and court costs. Bench Card, Off. Judic. Serv., Supreme Court Ohio, Cleveland, OH. http://www.acluohio.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/OhioSupremeCourtBenchCard2014_02.pdf [Google Scholar]

- ArchCity Defenders. 2014. Municipal courts white paper. White Pap., ArchCity Defenders, St. Louis, MO. https://cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3459956/ArchCity_Defenders_Municipal_Courts_Whitepaper.0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ariz. State Univ. 2017. The City of Phoenix Municipal Court’s Compliance Assistance Program, 2016: an economic assessment. Rep., L. William Seidman Res. Inst., W.P. Carey School Bus., Ariz. State Univ., Tempe, AZ. https://finesandfeesjusticecenter.org/content/uploads/2018/11/Phoenix-license-restoration-pilot-THE-CITY-OF-PHOENIX-MUNICIPAL-COURT%E2%80%99S-COMPLIANCE-ASSISTANCE-PROGRAM.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bell v. City of Jackson, 3:15-cv-732-TSL-RHW (S.D. Miss. 2015) [Google Scholar]

- Brayne S 2014. Surveillance and system avoidance: criminal justice contact and institutional attachment. Am. Sociol. Rev 79(3):367–91 [Google Scholar]

- Brown v. Lexington County, 3:17-cv-01426-MBS-SVH (D.S.C. 2017) [Google Scholar]

- Cain v. City of New Orleans, 281 F. Supp. 3d 624 (2017)

- Carnegie JA. 2007. Driver’s license suspensions, impacts and fairness study. Rep. FHWA NJ-2007–020, Dep. Transport., State N.J., Ewing Township, NJ. https://www.nj.gov/transportation/refdata/research/reports/FHWA-NJ-2007-020-V1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Carnegie JA, Eger RJ III. 2009. Reasons for driver license suspension, recidivism, and crash involvement among drivers with suspended/revoked licenses. Rep. No. HS-811 092, US Dep. Transport., Washington, DC. https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.dot.gov/files/documents/811092_driver-license.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland v. City of Montgomery, 2:13-cv-00732-MEF_TFM (M.D. Ala. 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Dade v. City of Sherwood, 4:16-cv-00602-JM (E.D. Ark. 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Edelman PB. 2017. Not a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in America. New York: New Press [Google Scholar]

- Ewing M 2017. A judicial pact to cut court costs for the poor. The Atlantic, December. 25. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/12/court-fines-north-carolina/548960/ [Google Scholar]

- Harper v. Professional Probation Services, 2:17-cv-01791 (2017)

- Harris A 2016. A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as Punishment for the Poor. New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Harris A, Evans H, Beckett K. 2010. Drawing blood from stones: legal debt and social inequality in the contemporary United States. Am. J. Sociol 115(6):1753–99 [Google Scholar]

- Henricks K, Harvey DC. 2017. Not one but many: monetary punishment and the Fergusons of America. Sociol. Forum 32:930–51 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson v. Jessup, 1:18-cv-00467 (M.D. N.C. 2018) [Google Scholar]

- Killman C 2017. Every sheriff in Oklahoma being sued over unpaid fees going to collection. Tulsa World, November. 6. https://www.tulsaworld.com/news/courts/every-sheriff-in-oklahoma-being-sued-over-unpaid-feesgoing/article_ffae758c-1287-5791-b7ea-eff2dde4bd03.html [Google Scholar]

- Kneisser v. McInerney, 1:15-cv-07043 (2015)

- Laisne M, Wool J, Henrichson C. 2017. Past due: examining the costs and consequences of charging for justice in New Orleans. Vera Inst. Justice, January. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney v. Derrick, 60CV-18–5616 (2018)

- Marsh A 2017. Rethinking driver’s license suspensions for nonpayment of fines and fees. Trends State Courts, Natl. Cent. State Courts, Williamsburg, VA. https://www.ncsc.org/~/media/Microsites/Files/Trends%202017/Rethinking-Drivers-License-Suspensions-Trends-2017.ashx [Google Scholar]

- Martin KD, Sykes BL, Shannon S, Edwards F, Harris A. 2018. Monetary sanctions: legal financial obligations in US systems of justice. Annu. Rev. Criminol 1:471–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RJ, Kern LJ, Williams A. 2018. The front end of the carceral state: police stops, court fines, and the racialization of due process. Soc. Serv. Rev 92(2):290–303 [Google Scholar]

- Natl. Cent. State Courts. 2017. Lawful collection of legal financial obligations. Bench Card, Task Force Fines Fees Bail Pract., Natl. Cent. State Courts, Williamsburg, VA. https://www.ncsc.org/~/media/Images/Topics/Fines%20Fees/Benchcard_final_feb2_2017.ashx [Google Scholar]

- New Jersey Courts. 2018. Report of the Supreme Court Committee on Municipal Court Operations, Fines and Fees. Rep., N.J. Supreme Court Comm., Newark, NJ. https://www.njcourts.gov/courts/assets/supreme/reports/2018/sccmcoreport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Oppel R Jr. 2018. Being poor can mean losing a driver’s license. Not anymore in Tennessee. New York Times, July 4. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/04/us/drivers-license-tennessee.html [Google Scholar]

- Ray v. Judicial Corrections Services, 2:12-cv-02819 (N.D. Ala. 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Roberts v. Black, 2:16-cv-11024 (E.D. La. 2016) [Google Scholar]

- Robinson v. Purkey, 3:17-cv-1263 (M.D. Tenn. 2017) [Google Scholar]

- Salas M, Ciolfi A. 2017. Driven by dollars: a state-by-state analysis of driver’s license suspension laws for failure to pay court debt. Rep., Legal Aid Justice Cent., Charlottesville, VA. https://www.justice4all.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Driven-by-Dollars.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sances MW, You HY. 2017. Who pays for government? Descriptive representation and exploitative revenue sources. J. Politics 79(3):1090–94 [Google Scholar]

- San Franc. Board Superv. 2016. San Francisco Fines and Fees Task Force: Initial Findings and Recommendations. San Francisco, CA: Off. Treas. Tax Collect., City County San Franc., CA. https://sftreasurer.org/sites/default/files/SF%20Fines%20%26%20Fees%20Task%20Force%20Initial%20Findings%20and%20Recommendations%20May%202017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- San Franc. Board Superv. 2018. Criminal justice system fees and penalties. Ord. 131–18, Board Superv., San Franc., CA. https://sfbos.org/sites/default/files/o0131-18.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Soss J, Weaver V. 2017. Police are our government: politics, political science, and the policing of race–class subjugated communities. Annu. Rev. Political Sci 20:565–91 [Google Scholar]

- State of Washington v. Blazina, 344 P.3d 680 (2015)

- State of Washington v. Ramirez, 413 P.3d 13 (2018)

- Stinnie v. Holcomb, 3:16-cv-00044-NKM (W.D. Va. 2017) [Google Scholar]

- Tex. Off. Court Adm. 2017. Bench card for judicial processes relating to the collection of fines and costs. Bench Card, Tex. Off. Court Adm., Austin, TX. http://www.txcourts.gov/media/1440393/sb-1913-justice-municipal.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Thomas et al. Haslam v. et al., 3:17-cv-00005 (M.D. Tenn. 2018) [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bur. 2012. Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finance. Washington, DC: US Census Bur. [Google Scholar]

- US Comm. Civ. Rights. 2017. Targeted fines and fees against communities of color: civil rights and constitutional implications. Statut. Enforc. Rep., US Comm. Civ. Rights, Washington, DC. https://www.usccr.gov/pubs/2017/Statutory_Enforcement_Report2017.pdf [Google Scholar]

- US Dep. Justice. 2015. A cycle of incarceration: prison, debt and bail practices. Press Release, December. 3. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/fact-sheet-white-house-and-justice-department-convening-cycle-incarceration-prison-debt-and [Google Scholar]

- US Dep. Justice. 2016. The price of justice: rethinking the consequences of justice fines and fees. Grant Announc., Off. Justice Progr., Washington, DC. https://www.bja.gov/funding/JRIpriceofjustice.pdf [Google Scholar]

- US Dep. Justice Civ. Rights Div. 2015. Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department. Rep., US Dep. Justice Civ. Rights Div., Washington, DC. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/press-releases/attachments/2015/03/04/ferguson_police_department_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wash. State Super. Courts. 2015. 2015 Reference guide on legal financial obligations (LFOs). Ref. Guide, Wash. State Super. Courts, Seattle, WA. https://www.wacdl.org/files/2015%20CLJ%20Reference%20Guide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Weill K 2017. Debt company makes sheriffs rich by jailing the poor, lawsuit claims. Daily Beast, November. 9. https://www.thedailybeast.com/debt-company-makes-sheriffs-rich-by-jailing-the-poor-lawsuit-claims [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins et al. v. Aberdeen Enterprizes II, Inc, 4:17-cv-00606 (2017)