Abstract

Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: AHA Scientific Statements, heart failure, health informatics

Table of Contents

Top 10 Take-Home Messages 476

Preamble 476

-

1. Introduction 478

1.1. Special Considerations 479

-

2. Methodology 479

2.1. Writing Committee Composition 479

2.2. Relationships With Industry and Other Entities 480

2.3. Review of Literature and Existing Data Definitions 480

2.4. Development of Terminology Concepts 480

2.5. Consensus Development 480

2.6. Relation to Other Standards 480

2.7. Peer Review, Public Review, and Board Approval 480

References 481

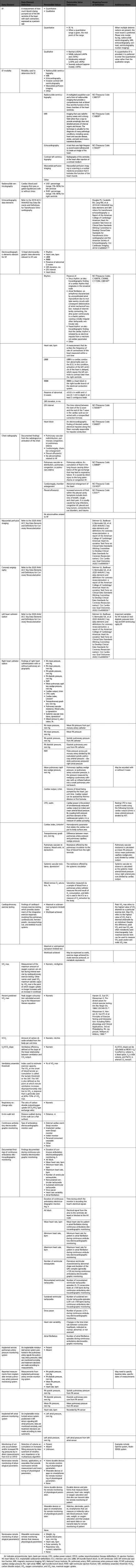

Appendix 1. Author Relationships With Industry and Other Entities (Relevant) 484

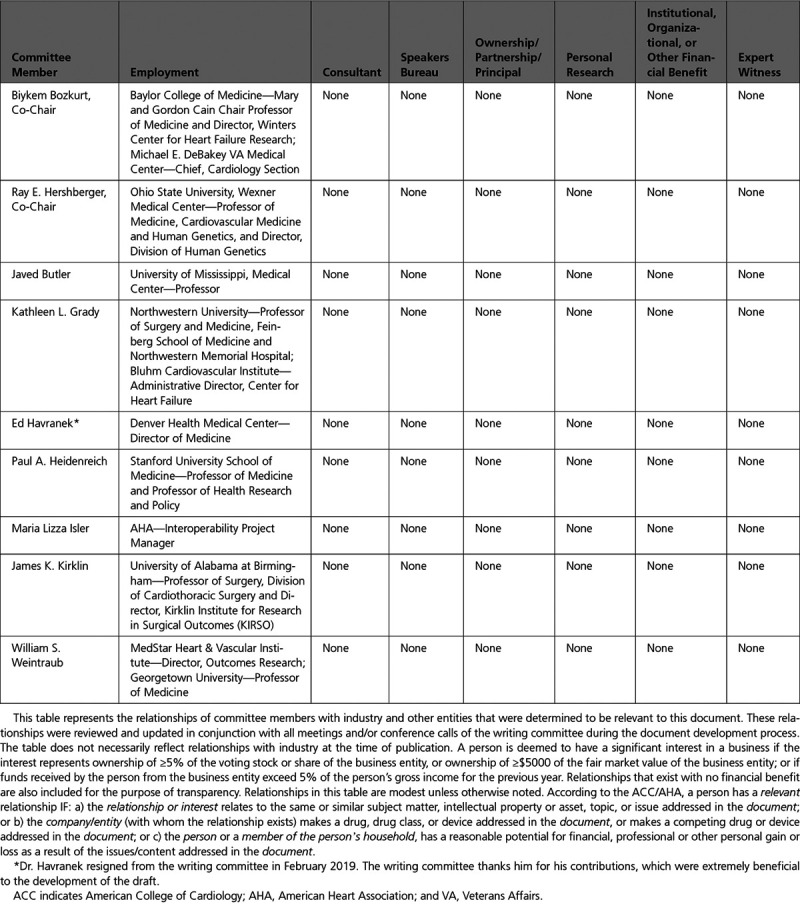

Appendix 2. Reviewer Relationships With Industry and Other Entities (Comprehensive) 485

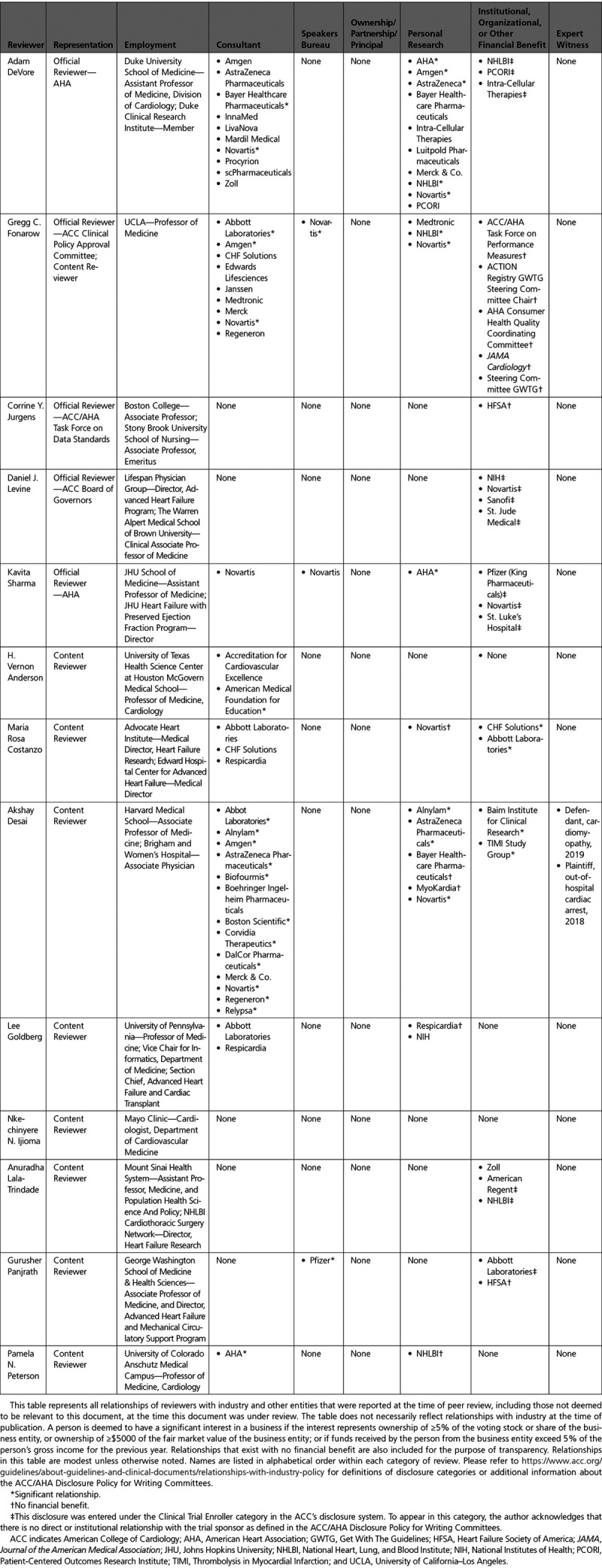

Appendix 3. Abbreviations 487

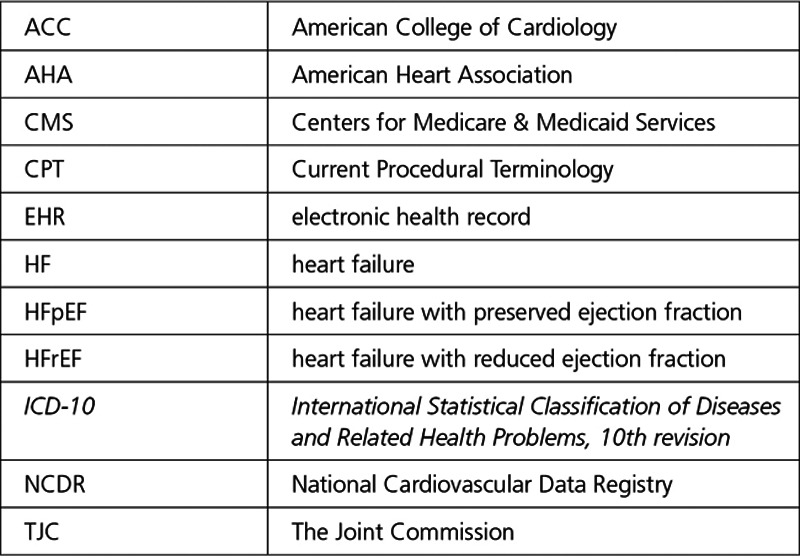

Appendix 4. Medical History 487

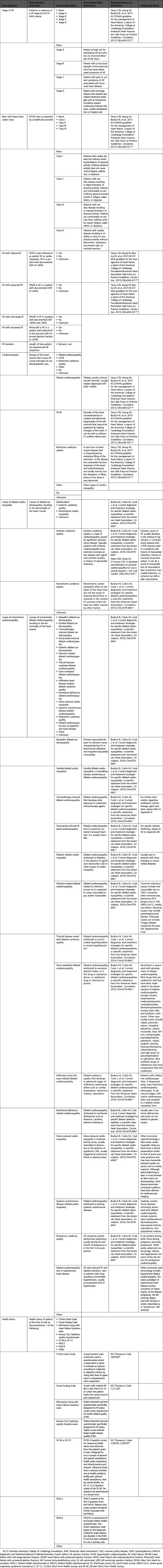

Appendix 5. Patient Assessment 531

Appendix 6. Diagnostic Procedures 544

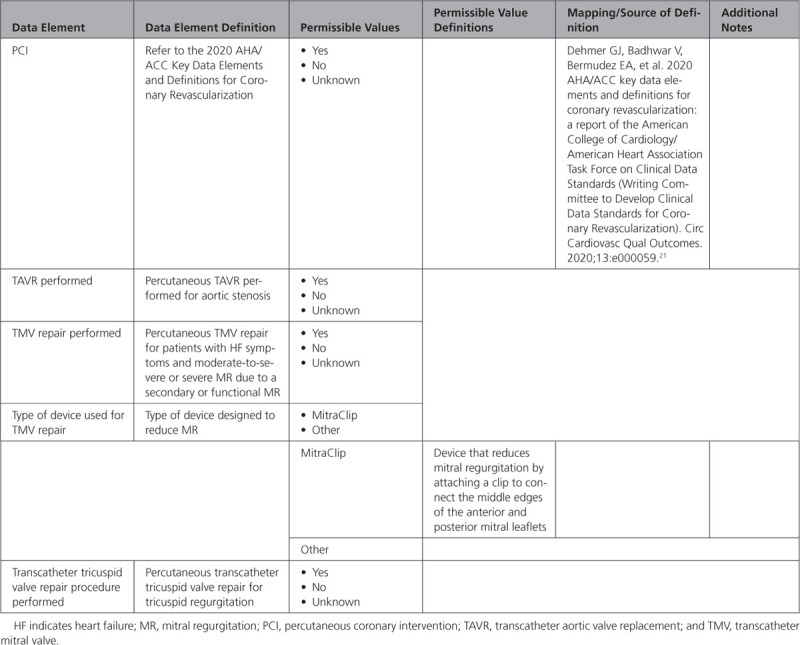

Appendix 7. Invasive Therapeutic Procedures for Heart Failure 554

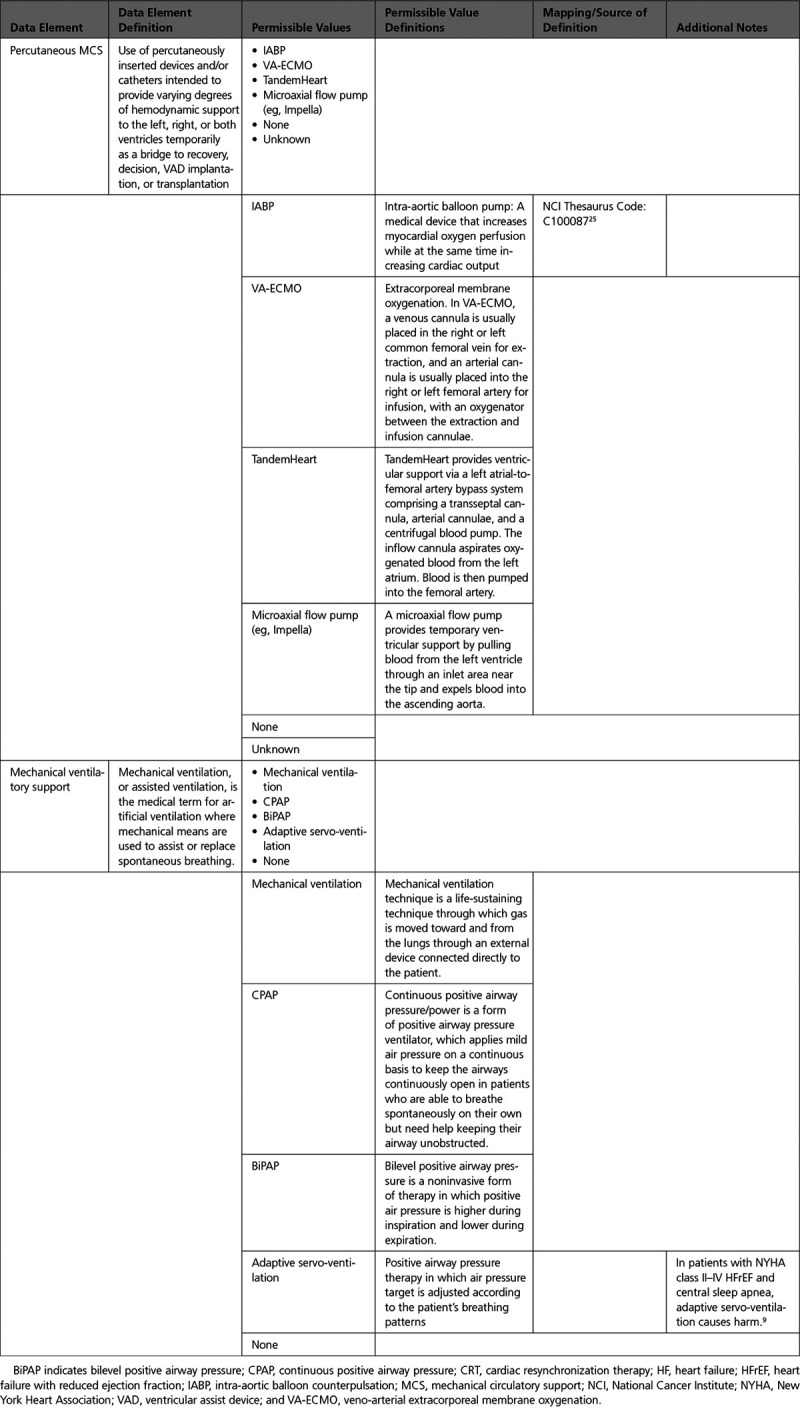

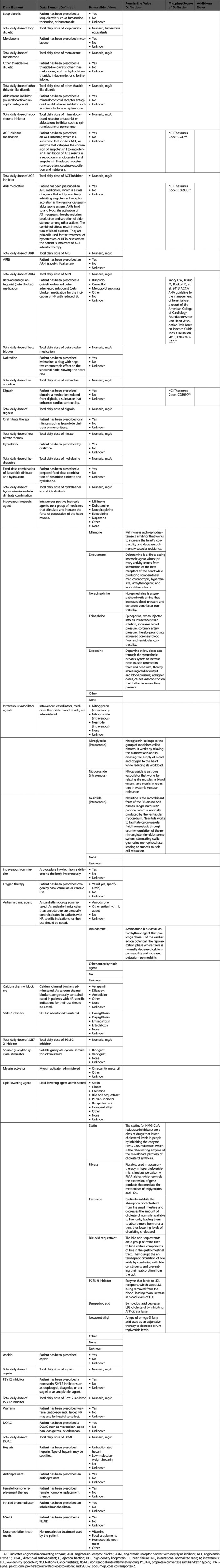

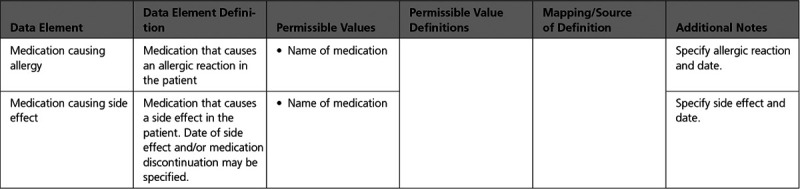

Appendix 8. Pharmacological Therapy 560

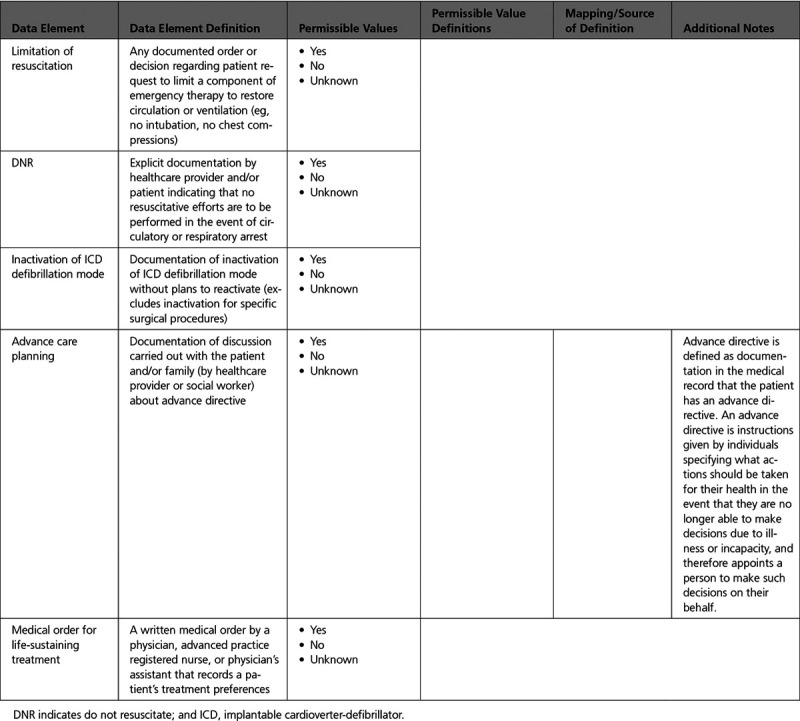

Appendix 9. End of Life Management 566

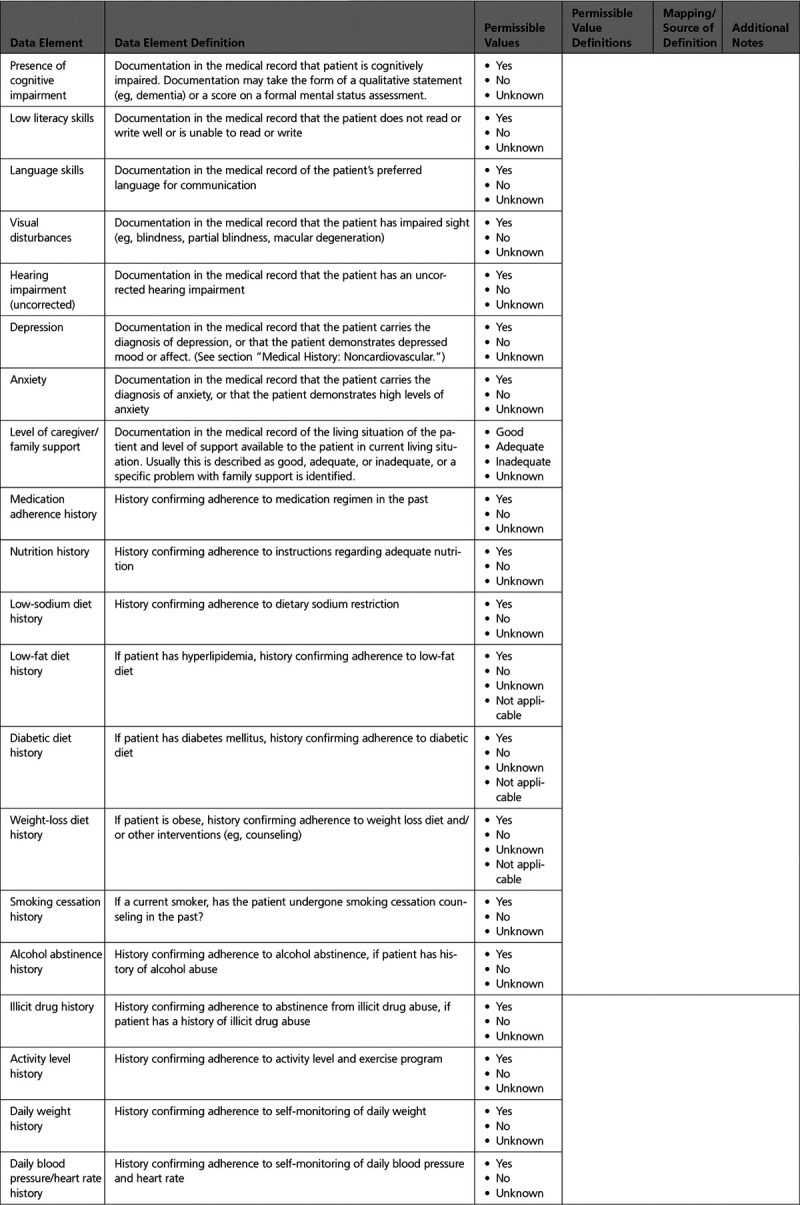

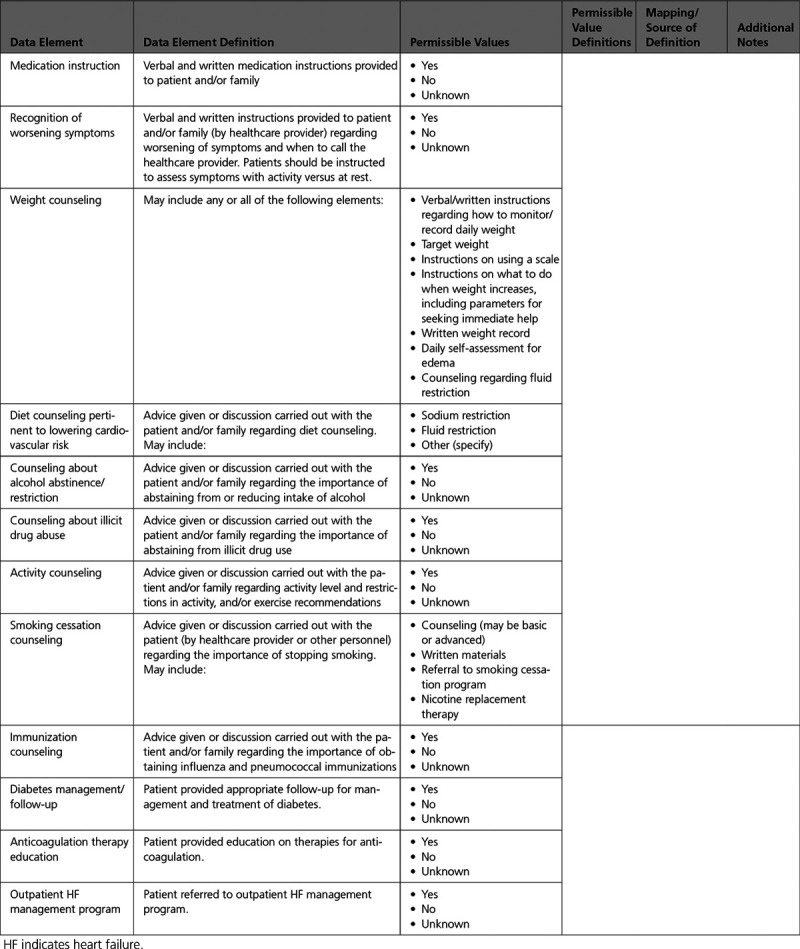

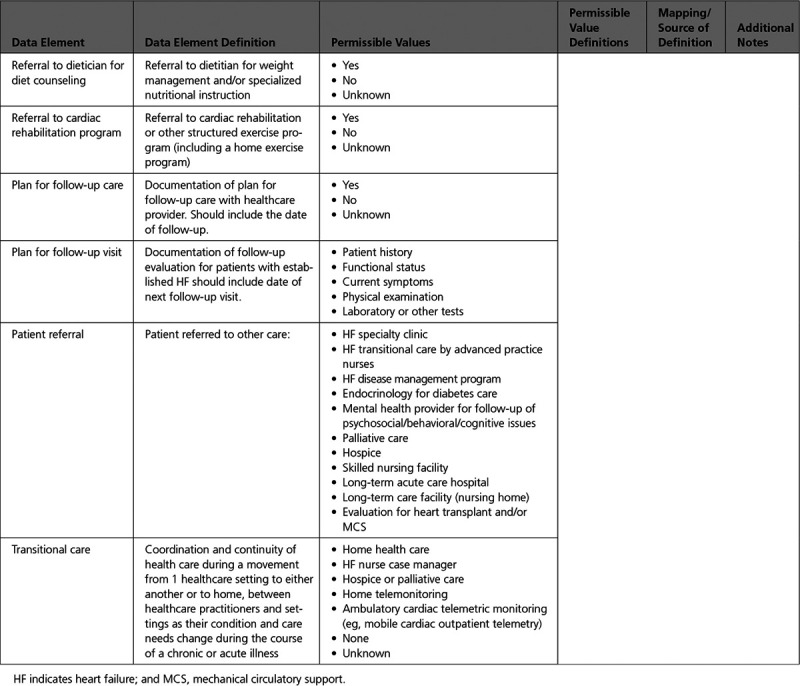

Appendix 10. Patient Education 567

Top 10 Take-Home Messages

This document (an update of the 2005 “ACC/AHA Key Data Elements and Definitions for Measuring the Clinical Management and Outcomes of Patients With Chronic Heart Failure”) presents a clinical lexicon comprising data elements related to heart failure (HF), without differentiation for chronic HF versus acute decompensated HF; inpatient versus outpatient; or medical management with or without palliative care, or hospice. Because HF is a chronic condition, and a patient can experience periodic acute decompensation, the writing committee considered data elements that are pertinent to the full range of care provided to these patients and intended to be useful for all care venues.

Data elements for HF risk factors, cardiovascular history, and noncardiovascular health determinants, including COVID-19 infection, are included.

Patient assessment with more detailed elements for symptoms, signs and physical exam findings, stages, and functional assessment were updated.

Structural and ejection fraction sub-phenotypes were added, including data elements for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmEF), and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

Data elements related to cause of HF and cardiomyopathy were added, emphasizing the importance of specific diagnoses such as cardiac amyloidosis and peripartum cardiomyopathy.

Data elements for noninvasive and invasive diagnostic modalities (echocardiogram, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, left and right heart catheterization) were expanded and updated.

Data elements for invasive therapeutic procedures, device therapies, and percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices were added.

Pharmacological treatment options with new classes of medications were updated, and new data elements for new classes of medications were added.

Data elements for patient education and counseling on self-care and patient-reported outcome measures were added.

These clinical data standards should be broadly applicable in various settings, including clinical programs such as HF clinics, transitions of care, clinical registries, clinical research, quality performance improvement initiatives, electronic health records and digital health information technology interoperability, public reporting programs, and education/self-care.

Preamble

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) support their members’ goal to improve the prevention and care of cardiovascular diseases through professional education, research, and development of guidelines and standards and by fostering policy that supports optimal patient outcomes. The ACC and AHA recognize the importance of the use of clinical data standards for patient management, assessment of outcomes, and conduct of research, and the importance of defining the processes and outcomes of clinical care, whether in randomized trials, observational studies, registries, or quality improvement initiatives.

Hence, clinical data standards strive to define and standardize data relevant to clinical topics in cardiovascular medicine, with the primary goal of assisting data collection by providing a platform of data elements and definitions applicable to various conditions. Broad agreement on a common vocabulary with reliable definitions used by all is vital to pool and/or compare data across studies to promote interoperability of electronic health records (EHRs) and to assess the applicability of research to clinical practice. The increasing national focus on adoption of certified EHRs along with financial incentives for providers to demonstrate “meaningful use” of those EHRs to improve healthcare quality render even more imperative and urgent the need for such definitions and standards. Therefore, the ACC and AHA have undertaken to define and disseminate clinical data standards—sets of standardized data elements and corresponding definitions—to collect data relevant to cardiovascular conditions. The ultimate purpose of clinical data standards is to contribute to the infrastructure necessary to accomplish the ACC’s mission of fostering optimal cardiovascular care and disease prevention and the AHA’s mission of being a relentless force for a world of longer, healthier lives.

The specific goals of clinical data standards are:

To establish a consistent, interoperable, and universal clinical vocabulary as a foundation for clinical care and clinical research

To facilitate the exchange of data across systems through harmonized, standardized definitions of key data elements

To facilitate the further development of clinical registries, quality and performance improvement programs, outcomes evaluations, public reporting, and clinical research, including the comparison of results within and across these initiatives

The key data elements and definitions are a compilation of variables intended to facilitate the consistent, accurate, and reproducible capture of clinical concepts; standardize the terminology used to describe cardiovascular diseases and procedures; create a data environment conducive to the assessment of patient management and outcomes for quality and performance improvement and clinical and translational research; and increase opportunities for sharing data across disparate data sources. The ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Task Force) selects cardiovascular conditions and procedures that will benefit from creation of a clinical data standard set. Experts in the subject area are selected to examine and consider existing standards and develop a comprehensive, yet not exhaustive, data standard set. When undertaking a data collection effort, only a subset of the elements contained in a clinical data standard listing may be needed or, conversely, users may want to consider whether it may be necessary to collect some elements not listed. For example, in the setting of a randomized, clinical trial of a new drug, additional information would likely be required regarding study procedures and drug therapies. Another example is as follows: If the data set is to be used for quality improvement, safety initiatives, or administrative functions, other elements such as Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10-CM) codes, or outcomes may be added. The intent of the Task Force is to standardize the clinical concepts, keeping the focus on the patient and the clinical care, not necessarily on administrative billing or coding concepts, and the clinical concepts selected for development are generally cardiovascular specific, where a standardized terminology already exists. The clinical data standards can therefore serve as a guide for development of administrative data sets, and complementary administrative or quality assurance elements can evolve from these core clinical concepts and elements. Thus, rather than forcing the clinical data standards to harmonize with existing administrative codes, such as ICD-10-CM or CPT codes, we would envision the administrative codes to follow the lead of the clinical data standards. This approach would allow the clinical care to lead standardization of the terminologies in health care.

The ACC and AHA recognize that there are other national efforts to establish clinical data standards, and every attempt is made to harmonize newly published standards with existing standards. Writing committees are instructed to consider adopting or adapting existing nationally recognized data standards if the definitions and characteristics are validated, useful, and applicable to the set under development. In addition, the ACC and AHA are committed to continually expanding their portfolio of clinical data standards and will create new standards and update existing ones as needed to maintain their currency and promote harmonization with other standards as health information technology and clinical practice evolve.

The Privacy Rule of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which went into effect in April 2003, heightened all practitioners’ awareness of our professional commitment to safeguard our patients’ privacy. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy regulations specify which information elements are considered “protected health information.” These elements may not be disclosed to third parties (including registries and research studies) without the patient’s written permission. Protected health information may be included in databases used for healthcare operations under a data use agreement. Research studies using protected health information must be reviewed by an institutional review board or a privacy board.

We have included identifying information in all clinical data standards to facilitate uniform collection of these elements when appropriate. For example, a longitudinal clinic database may contain these elements because access is restricted to the patient’s healthcare providers.

In clinical care, healthcare providers communicate with each other through a common vocabulary. In an analogous manner, the integrity of clinical research depends on firm adherence to prespecified procedures for patient enrollment and follow-up; these procedures are guaranteed through careful attention to definitions enumerated in the study design and case report forms. When data elements and definitions are standardized across studies, comparison, pooled analysis, and meta-analysis are enabled, thus deepening our understanding of individual studies.

The recent development of quality performance measurement initiatives, particularly those for which the comparison of providers and institutions is an implicit or explicit aim, has further raised awareness about the importance of clinical data standards. Indeed, a wide audience, including nonmedical professionals such as payers, regulators, and consumers, may draw conclusions about care and outcomes. To understand and compare care patterns and outcomes, the data elements that characterize them must be clearly defined, consistently used, and properly interpreted.

Hani Jneid, MD, FACC, FAHA

Chair, ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards

1. Introduction

The Task Force has been spearheading the initiative to standardize the lexicon of cardiovascular medicine to enhance the use of clinical data, improve clinical communication, optimize quality assurance and improvement, assess outcomes, enhance process improvement efforts, and facilitate clinical research, development, and analysis of registries. Because the ACC and AHA are committed to updating existing standards as needed to maintain their currency and promote harmonization with other standards as health information technology and clinical practice evolve, this document is provided as an update of the 2005 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for chronic heart failure.1 The goal of this publication is to provide new data elements consistent with practice guidelines and updated terminology and attributes in compliance with current methodology of the Task Force2 and current policies of the ACC and AHA regarding harmonization of data across organizations and disciplines.

Heart failure (HF) data standards are of critical importance to clinical providers, investigators, administrators, healthcare services and institutions, regulators, legislators, and payers more than ever as a result of: 1) increasing prevalence and burden of HF3,4; 2) increased focus on performance metrics for HF5; 3) increasing need for large data sets to examine comparative effectiveness and safety of treatment strategies in real world patients6; 4) increased recognition of healthcare disparities that require understanding of patient, healthcare delivery, and system variables7; 5) growing need for new effective preventive and treatment strategies in HF targeted for different stages or types of HF8; subgroups of interest and comorbidities requiring better classification and documentation of patient and treatment variables; 6) need for improved communication and for shared decision-making and transitions of care between different levels of care and providers9,10; 7) development of models for prediction of therapeutic benefit and outcomes11; 8) universally understandable data for individualization of therapies and management strategies for patients with complex HF by different providers; and 9) development and conduct of future registries, at both hospital and national levels, by providing a list of major variables, outcomes, and definitions.

Approximately 6.2 million persons ≥20 years of age in the United States have HF, with approximately 1 million new HF cases diagnosed annually, and the prevalence continues to rise.3,12 Despite improvements in age-adjusted HF-related survival rates between 2000 and 2012, there has been a recent increase in mortality rates for all age and sex subgroups.12–14 HF remains as the primary diagnosis in >1 million hospitalizations annually, and the total cost of HF care in the United States exceeds $30 billion annually, with over half of these costs spent on hospitalizations.15 The mortality rates after hospitalization for HF remains high, at approximately 20% to 25% at 1 year, with similar mortality rates for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction or heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.16

The clinical syndrome of HF may result from different causes. Thus, despite a common syndrome of HF, different etiologies may imply different prognosis and varying treatment strategies, underlining the importance of specific data elements for emphasizing these differences in HF.8 Similarly, the syndrome of HF commonly overlaps with other cardiovascular diseases, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, valvular disease, and primary myocardial disease, which are common causes of HF. Specifying these data elements for patients with HF is important for clinical care, performance improvement, research, and endpoints. Standardized data elements and definitions across studies can help accelerate and facilitate research in HF through dissemination and sharing of relevant information, comparisons, pooled analyses, and meta-analyses.17

In clinical care, a broad spectrum of clinicians provides a continuum of care for patients with HF, ranging from primary care/family medicine providers, HF specialists and/or cardiologists, cardiac and transplant surgeons, interventional cardiologists, electrophysiologists, advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, pharmacists, hospitalists, home healthcare providers, palliative care specialists and nurses, hospice specialists and nurses, social workers, and cardiac rehabilitation specialists to investigators, who must communicate with each other through a common vocabulary. Care of patients with HF may take place in specialized clinics delivered by a variety of providers previously mentioned, necessitating care coordination comprising common terminology with a patient-centered approach.18 Furthermore, HF is a chronic problem, and patients are likely to transition through different stages of HF, which requires recognition and definition of these states with common terminology standardized across different providers and encounters of care.

Similarly, given the recent emphasis on quality performance measurement initiatives, particularly those for which institutions and providers are compared against each other or against benchmarks, and reimbursement strategies and penalties that are attached to such metrics, the necessity for reliable, risk adjustable, and analyzable data is gaining more importance for the professional community, as well as for payers, regulators, legislators, and consumers.5,19,20

The writing committee envisions that the data elements might be useful in these broad categories:

Clinical programs, such as HF clinics, where many clinicians work together to achieve specific goals for the care and care coordination of patients with HF.

Transitions of care, in which patients with HF move through different locations and levels of care (ie, inpatient, outpatient [eg, home, rehabilitation center, nursing home], palliative care, and hospice) or progress through different stages of HF (Stages A to D), with providers ranging from HF specialists, cardiac transplant physicians, home healthcare or palliative care providers, and primary care providers.

Clinical registries, for ongoing care, prospective epidemiologic and comparative effectiveness research, pre- or postmarket analysis for efficacy and safety in populations of interest.

Clinical research, particularly prospective randomized clinical trials where eventual pooled analysis or meta-analysis is anticipated.

Quality performance measurement initiatives, provider or institutional based or external, retrospective, or prospective.

Organization and design of electronic medical information initiatives, such as EHRs, pharmacy databases, computerized decision support, and cloud technologies incorporating health information.

Public health policy, healthcare coverage, insurance coverage, and legislation development to provide appropriate and timely care for patients with HF and to prevent disparities in HF care.

The data element tables are also included as an Excel file in the Online Data Supplement.

1.1. Special Considerations

Several points are important to recognize regarding the scope of this document. First, given the magnitude of additional data elements that cardiac transplantation and mechanical circulatory support device therapies would entail, the writing group decided to focus on HF and not include cardiac transplantation and mechanical circulatory support data elements in detail in this document.

Second, the data elements were not differentiated for chronic HF versus acute decompensated HF; or for inpatient, outpatient, palliative care, or hospice status, because HF is a chronic condition that is not an episodic event, and a patient can transition from one status to the other through his/her life time. The writing committee considered data elements pertinent to the full range of care provided to these patients and are intended to be useful for all care venues.

Third, the data elements were not differentiated for new onset incident versus prevalent cases or number of encounters, and databases can be built and customized according to users’ needs to capture such information.

Fourth, the writing committee would like to alert the readers to the existence of other documents and guidelines with which we tried to harmonize and are likely to complement the content of our document, including the “2020 AHA/ACC Key Data Elements and Definitions for Coronary Revascularization,”21 “2019 ACC/AHA/ASE Key Data Elements and Definitions for Transthoracic Echocardiography,”22 “2014 ACC/AHA Key Data Elements and Definitions for Cardiovascular Endpoint Events in Clinical Trials,”23 “2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure,”24 “2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure,”9 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html), and The Joint Commission core HF performance measures; meaningful use criteria; The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's quality indicators for HF; Get With The Guidelines and National Cardiovascular Data Registry CathPCI Registry data elements. We made every attempt to use guideline- and evidence-based definitions.

Finally, we did not include data element fields for entry of calculated risk scores, as databases can be programmed and customized to calculate risks scores according to the user’s objective as different risk models can be used for different purposes.

The intent of this writing committee was not to be overly prescriptive.

2. Methodology

2.1. Writing Committee Composition

The Task Force selected the members of the writing committee. The writing committee consisted of 8 individuals with domain expertise in HF, cardiomyopathy, cardiovascular disease, outcomes assessment, medical informatics, health information management, and healthcare services research and delivery.

2.2. Relationships With Industry and Other Entities

The Task Force made every effort to avoid actual or potential conflicts of interest that might arise as a result of an outside relationship or a personal, professional, or business interest of any member of the writing committee. Specifically, all members of the writing committee were required to complete and submit a disclosure form showing all such relationships that could be perceived as real or potential conflicts of interest. These statements were reviewed by the Task Force and updated when changes occurred. Authors’ and peer reviewers’ relationships with industry and other entities pertinent to this data standards document are disclosed in Appendixes 1 and 2, respectively. In addition, for complete transparency, the disclosure information of each writing committee member—including relationships not pertinent to this document—is available as a Supplemental Table. The work of the writing committee was supported exclusively by the AHA and ACC without commercial support. Writing committee members volunteered their time for this effort. Meetings of the writing committee were confidential and attended only by committee members and staff.

2.3. Review of Literature and Existing Data Definitions

A substantial body of literature was reviewed to create this article.1,9,21–24 This information was augmented by multiple peer-reviewed references listed in the tables under the column “Mapping/Source of Definition.”

2.4. Development of Terminology Concepts

The writing committee aggregated, reviewed, harmonized, and extended these terms to develop a controlled, semantically interoperable, machine-computable terminology set that would be usable, as appropriate, in as broad a number of contexts as possible. As necessary, the writing committee identified the contexts where individual terms required differentiation according to their proposed use (ie, research/regulatory versus clinical care contexts).

This publication was developed with the intent that it will serve as a common lexicon and base infrastructure that can be used by end users to augment work related to standardization and healthcare interoperability including, but not limited to, structural, administrative, and technical metadata development. The resulting appendixes (Appendixes 4–10) list the data element in the first column, followed by a clinical definition of the data element. The allowed responses (“permissible values”) for each data element in the next column are the acceptable “answers” for capturing the information. For data elements with multiple permissible values, a bulleted list of the permissible values is provided in the row listing the data element, followed by multiple rows listing each permissible value and corresponding permissible value definition, as needed. Where possible, clinical definitions (and clinical definitions of the corresponding permissible values) are repeated verbatim as authored by the Standardized Data Collection for Cardiovascular Trials Initiative23 or as previously published in reference documents.

2.5. Consensus Development

The Task Force established the writing committee per the processes described in the Task Force’s methodology paper.2 The primary responsibility of the writing committee was to review and refine the “ACC/AHA Key Data Elements and Definitions for Measuring the Clinical Management and Outcomes of Patients With Chronic Heart Failure”1 and develop a harmonized data set for coronary revascularization that will provide the attributes and other informatics formalisms required to attain interoperability of the terms. The work of the writing committee was accomplished via a series of teleconference and web conference meetings, along with extensive email correspondence. The review work was distributed among subgroups of the writing committee based on interest and expertise in the components of the terminology set. The proceedings of the workgroups were then assembled, resulting in the vocabulary and associated descriptive text in Appendixes 4–10. All members reviewed and approved the final vocabulary.

2.6. Relation to Other Standards

The writing committee reviewed the available published data standards, including registry data dictionaries from registries, which were specifically developed for HF. Relative to published data standards, the writing committee anticipates that this terminology set will facilitate the uniform adoption of these terms, where appropriate, by the clinical, clinical and translational research, regulatory, quality and outcomes, and EHR communities.

2.7. Peer Review, Public Review, and Board Approval

This document was reviewed by official reviewers nominated by ACC and AHA. To increase its applicability further, the document was posted on the ACC and AHA websites for a 30-day public comment period. This document was approved for publication by the ACC Clinical Policy Approval Committee in October 2020, by the AHA Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee in September 2020, and by the AHA Executive Committee in December 2020. The writing committee anticipates that these data standards will require review and updating in the same manner as other published guidelines, performance measures, and appropriate use criteria. The writing committee will, therefore, review the set of data elements on a periodic basis, starting with the anniversary of publication of the standards, to ascertain whether modifications should be considered.

ACC/AHA Task Force on Clinical Data Standards

Hani Jneid, MD, FACC, FAHA, Chair; Srinath Adusumalli, MD, MSc, FACC*; Sana Al-Khatib, MD, MHS, FACC, FAHA*; H. Vernon Anderson, MD, FACC*; Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, FACC, FAHA; Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, FACC, FAHA*,†; Bruce E. Bray, MD, FACC; Mauricio G. Cohen, MD, FACC; Monica Colvin, MD, MS, FAHA; Garth Nigel Graham, MD, FACC*; Nasrien Ibrahim, MD, FACC, FAHA; Corrine Y. Jurgens, PhD, RN, ANP, FAHA; David P. Kao, MD*; Arnav Kumar, MBBS; Leo Lopez, MD, FACC, FAHA*; Nidhi Madan, MD, MPH; Amgad N. Makaryus, MD, FACC; Gregory M. Marcus, MD, FACC, FAHA*; Paul Muntner, PhD, FAHA; Hitesh Raheja, MD*; Jennifer Rymer, MD*; Kevin Shah, MD, FACC*; April W. Simon, RN, MSN; Nadia R. Sutton, MD, MPH, FACC; James E. Tcheng, MD, FACC*; William S. Weintraub, MD, MACC, FAHA†; Emily Zeitler, MD, MHS, FACC*

Presidents and Staff

American College of Cardiology

Athena Poppas, MD, FACC, President

Cathleen C. Gates, Chief Executive Officer

John S. Rumsfeld, MD, PhD, FACC, Chief Science Officer and Chief Innovation Officer

Lara Slattery, Division Vice President, Clinical Registry and Accreditation

Grace D. Ronan, Team Lead, Clinical Policy Publication

Timothy W. Schutt, MA, Clinical Policy Analyst

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association

Abdul R. Abdullah, MD, Director, Guideline Science and Methodology

Kathleen LaPoint, MS, Clinical Healthcare Data Manager

American Heart Association

Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, MS, FAAN, FAHA, President

Nancy Brown, Chief Executive Officer

Mariell Jessup, MD, FAHA, Chief Science and Medical Officer

Radhika Rajgopal Singh, PhD, Vice President, Office of Science, Medicine and Health

Jody Hundley, Production and Operations Manager, Scientific Publications, Office of Science Operations

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1. Author Relationships With Industry and Other Entities (Relevant)—2021 ACC/AHA Key Data Elements and Definitions for Heart Failure

Appendix 2. Reviewer Relationships With Industry and Other Entities (Comprehensive)—2021 ACC/AHA Key Data Elements and Definitions for Heart Failure

Appendix 3. Abbreviations

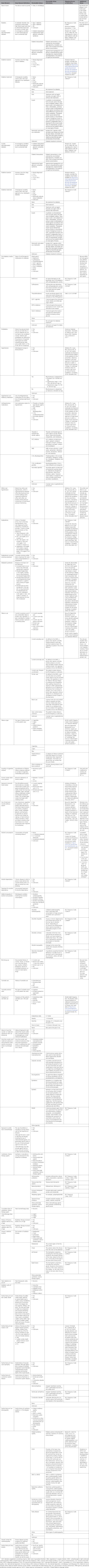

Appendix 4. Medical History

A. Heart Failure Risk Factors

B. Cardiovascular History

C. Noncardiovascular History

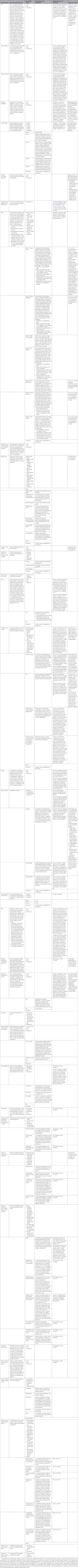

Appendix 5. Patient Assessment

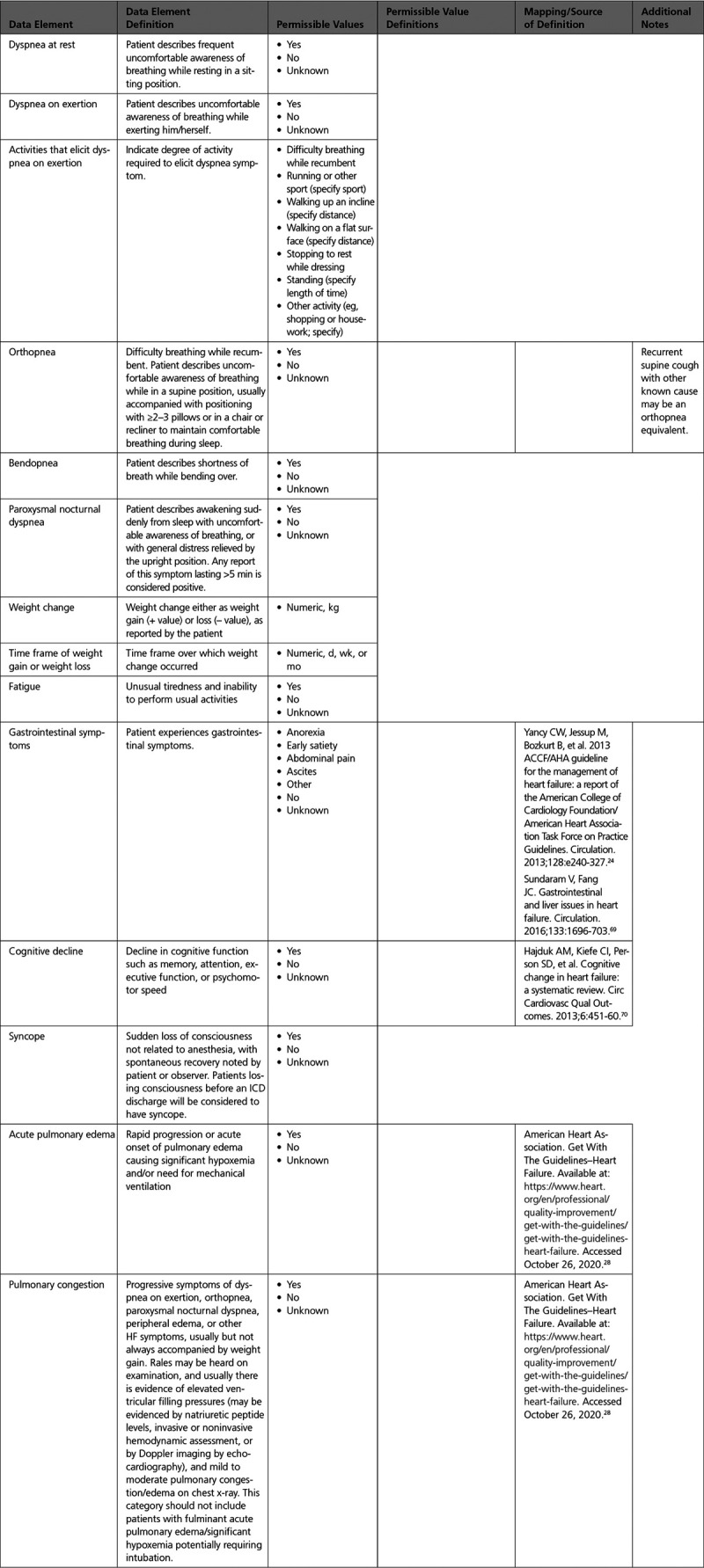

A. Current Symptoms and Signs: Clinical Symptoms

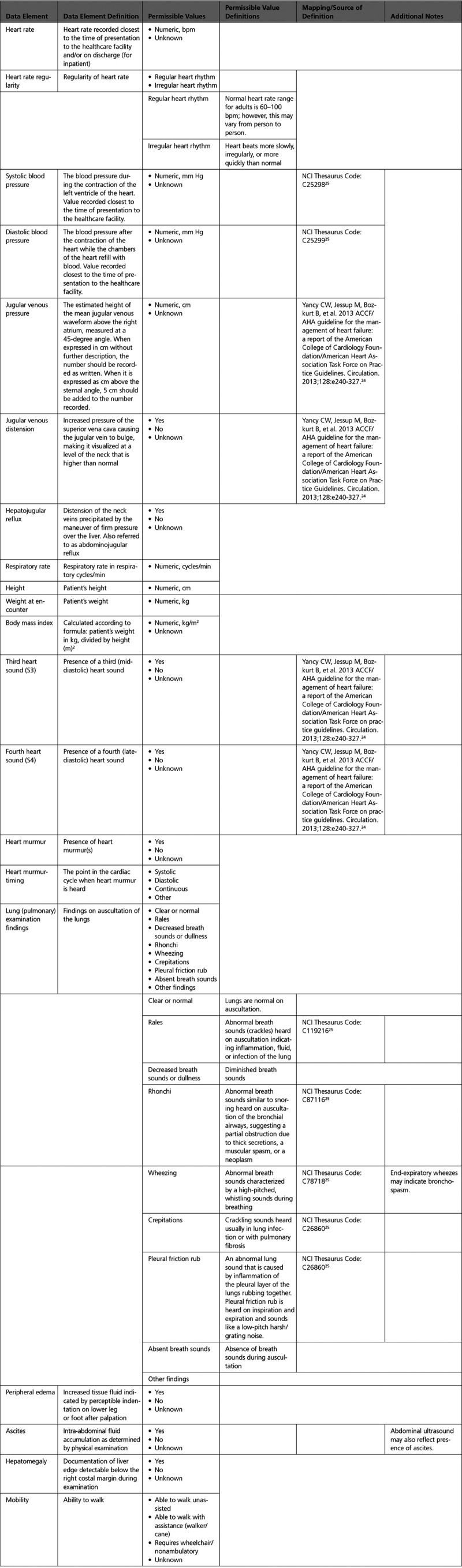

B. Current Symptoms and Signs: Physical Examination

C. Summary Assessment: Heart Failure Stages, Functional Assessment

Appendix 6. Diagnostic Procedures

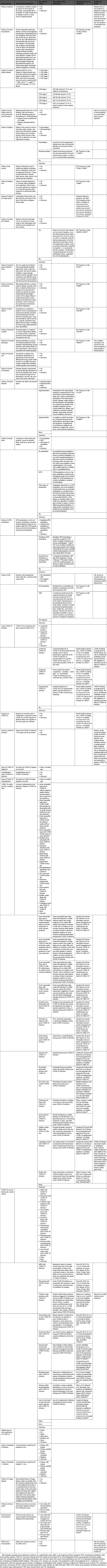

Appendix 7. Invasive Therapeutic Procedures for Heart Failure

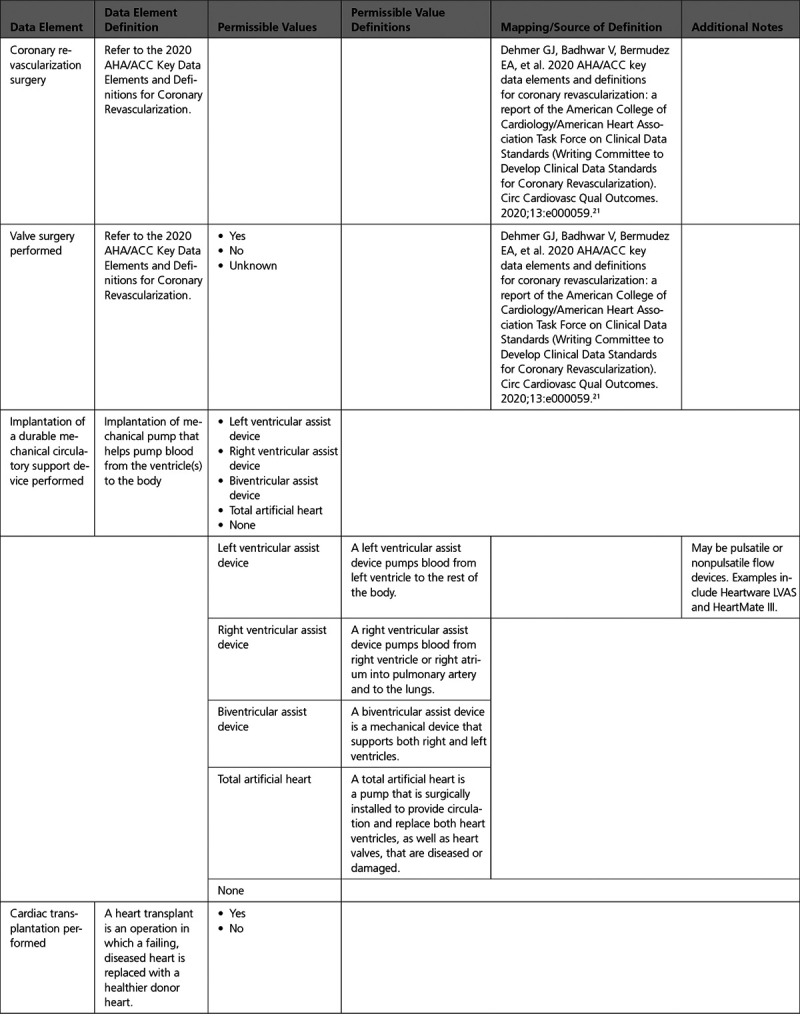

A. Surgical Procedures

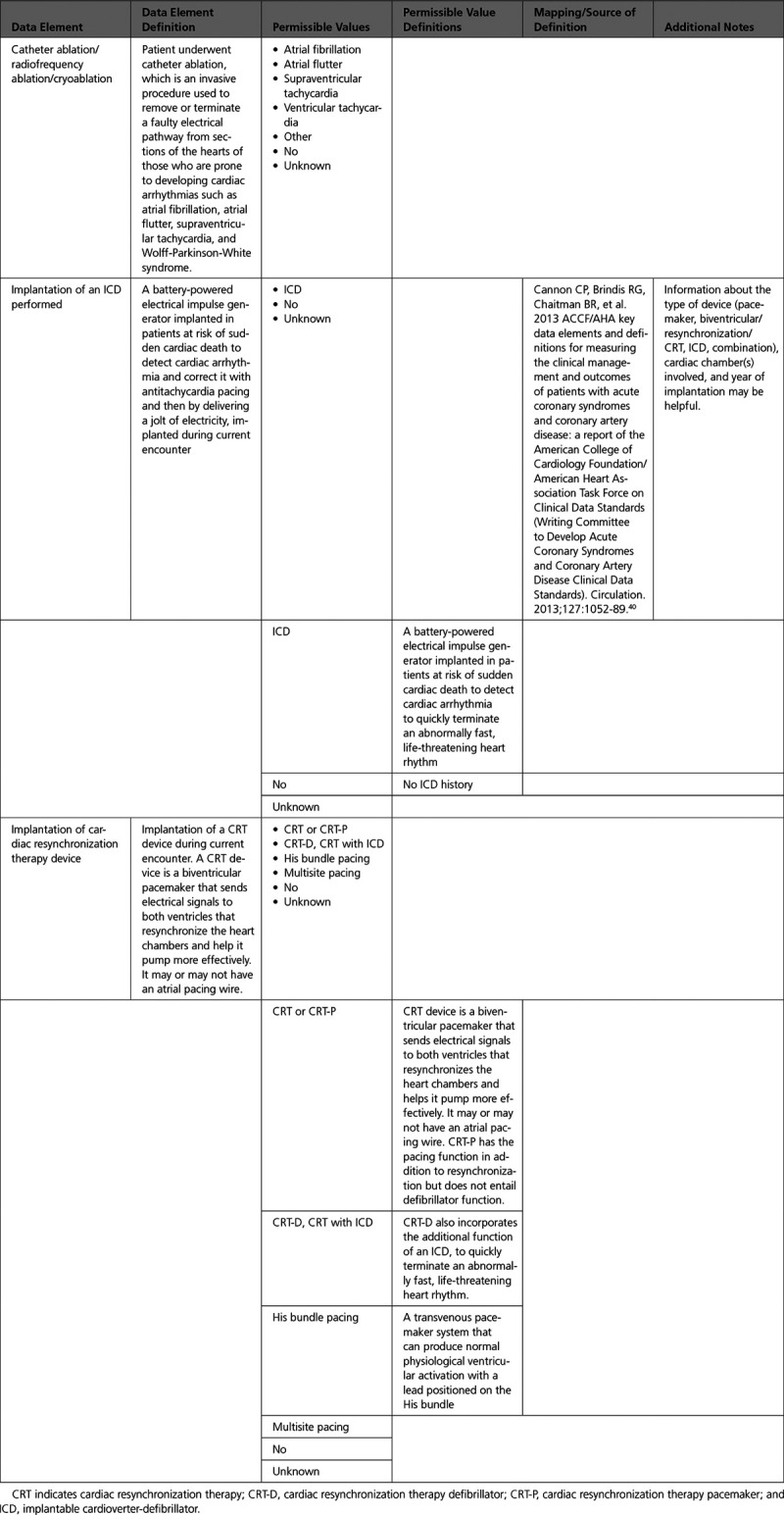

B. Electrophysiological Procedures

C. Percutaneous Interventional Procedures

D. Circulatory/Ventilatory Support

Appendix 8. Pharmacological Therapy

A. Therapies for Heart Failure

B. Medication Allergy/Side Effects

Appendix 9. End of Life Management

Appendix 10. Patient Education

A. Assessment of Status: Assessment of Learning Readiness

B. Intervention and Referral: Education/Counseling Intervention to Promote Self-Care

C. Intervention and Referral

Former Task Force member; current member during the writing effort.

Former Task Force Chair during this writing effort.

Task Force Liaison.

The American Heart Association requests that this document be cited as follows: Bozkurt B, Hershberger RE, Butler J, Grady KL, Heidenreich PA, Isler ML, Kirklin JK, Weintraub WS. 2021 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Data Standards for Heart Failure). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14:e000102. doi: 10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000102

Endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons

This document was approved by the American College of Cardiology Clinical Policy Approval Committee in October 2020, by the American Heart Association Science Advisory and Coordinating Committee in September 2020, and by the American Heart Association Executive Committee in December 2020.

Appendix 4 includes data elements used to describe congenital heart disease obtained from the International Paediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code (IPCCC) as published by the International Society for Nomenclature of Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease (ISNPCHD) (https://ipccc.net/).

Supplemental materials (Data Supplement [Appendix 4 in an Excel file] and a Comprehensive RWI table) are available with this article at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000102

This article has been copublished in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Copies: This document is available on the websites of the American College of Cardiology (www.acc.org) and the American Heart Association (professional.heart.org). A copy of the document is also available at https://professional.heart.org/statements by selecting the “Guidelines & Statements” button. To purchase additional reprints, call 215-356-2721 or email Meredith.Edelman@wolterskluwer.com.

The expert peer review of AHA-commissioned documents (eg, scientific statements, clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews) is conducted by the AHA Office of Science Operations. For more on AHA statements and guidelines development, visit https://professional.heart.org/statements. Select the “Guidelines & Statements” drop-down menu near the top of the webpage, then click “Publication Development.”

Permissions: Multiple copies, modification, alteration, enhancement, and/or distribution of this document are not permitted without the express permission of the American Heart Association. Instructions for obtaining permission are located at https://www.heart.org/permissions. A link to the “Copyright Permissions Request Form” appears in the second paragraph (https://www.heart.org/en/about-us/statements-and-policies/copyright-request-form).

References

- 1.Radford MJ, Arnold JM, Bennett SJ, et al. ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with chronic heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Heart Failure Clinical Data Standards). Circulation. 2005;112:1888–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendel RC, Bozkurt B, Fonarow GC, et al. ACC/AHA 2013 methodology for developing clinical data standards: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards. Circulation. 2014;129:2346–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonow RO, Ganiats TG, Beam CT, et al. ACCF/AHA/AMA-PCPI 2011 performance measures for adults with heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and the American Medical Association-Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. Circulation. 2012;125:2382–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eapen ZJ, McBroom AJ, Gray R, et al. Priorities for comparative effectiveness reviews in cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinney SP. Disparities in heart failure care: now is the time to focus on health care delivery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:808–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozkurt B, Colvin M, Cook J, et al. Current diagnostic and treatment strategies for specific dilated cardiomyopathies: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e579–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017;136:e137–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:1928–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aaronson KD, Cowger J. Heart failure prognostic models: why bother? Circ Heart Fail. 2012:6–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, et al. Deaths: final data for 2014 Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2016;65:1–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ni H, Xu J. Recent trends in heart failure-related mortality: United States, 2000–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, et al. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:260–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson HV, Weintraub WS, Radford MJ, et al. Standardized cardiovascular data for clinical research, registries, and patient care: a report from the Data Standards Workgroup of the National Cardiovascular Research Infrastructure project. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1835–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riegel B, Moser DK, Anker SD, et al. State of the science: promoting self-care in persons with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120:1141–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jencks SF, Cuerdon T, Burwen DR, et al. Quality of medical care delivered to Medicare beneficiaries: a profile at state and national levels. JAMA. 2000;284:1670–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dehmer GJ, Badhwar V, Bermudez EA, et al. 2020 AHA/ACC key data elements and definitions for coronary revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Data Standards for Coronary Revascularization). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Douglas PS, Carabello BA, Lang RM, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA/ASE key data elements and definitions for transthoracic echocardiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Data Standards for Transthoracic Echocardiography) and the American Society of Echocardiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:e000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Cardiovascular Endpoints Data Standards). Circulation. 2015;132:302–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Cancer Institute. NCI thesaurus. Available at: https://ncit.nci.nih.gov/ncitbrowser/. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 26.American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes–2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:S13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, et al. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1335–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Heart Association. Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure. Available at: https://www.heart.org/en/professional/quality-improvement/get-with-the-guidelines/get-with-the-guidelines-heart-failure. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 29.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2020. Diabetes Care. 2019;43:S1–212. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018;138:e484–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e1082–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e596–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barua RS, Rigotti NA, Benowitz NL, et al. 2018 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on tobacco cessation treatment: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3332–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Health and Human Services. E-Cigarette use among youth and young adults: a report of the surgeon general. 2016. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Center for Health Statistics. National health interview survey. Prevalence of current cigarette smoking among adults aged 18 and over: United States, 1997–September 2017, Sample Adult Core Component. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/EarlyRelease201803_08.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 37.Institute of Medicine Committee on Secondhand Smoke Exposure and Acute Coronary Events. Secondhand smoke exposure and cardiovascular effects: making sense of the evidence. 2010. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol use and your health. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 39.World Health Organization. The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): manual for use in Primary Care. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924159938-2. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 40.Cannon CP, Brindis RG, Chaitman BR, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes and coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Acute Coronary Syndromes and Coronary Artery Disease Clinical Data Standards). Circulation. 2013;127:1052–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2012;126:e354–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e663–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campeau L. The Canadian Cardiovascular Society grading of angina pectoris revisited 30 years later. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:371–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.American College of Cardiology. ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus. Available at: http://tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator-Plus/#!/calculate/estimate/. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 45.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018;138:e618–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:e652–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:e574–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44:2064–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hicks KA, Mahaffey KW, Mehran R, et al. 2017 Cardiovascular and stroke endpoint definitions for clinical trials. Circulation. 2018;137:961–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Cardiovascular Data Registry. CathPCI Registry Coder's Data Dictionary Supplement v5.0. Available at: https://www.ncdr.com/WebNCDR/docs/default-source/cathpci-v5.0-documents/cathpci-registry-v5-dynamic-lists_8-8-17.pdf?sfvrsn=6816de9f_25. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 51.Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Online STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Risk Calculator. Available at: http://riskcalc.sts.org/stswebriskcalc/calculate. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 52.Creager MA, Belkin M, Bluth EI, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACR/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM/SVN/SVS key data elements and definitions for peripheral atherosclerotic vascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Clinical Data Standards for Peripheral Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease). Circulation. 2012;125:395–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130:e199–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2018;138:e272–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veerakul G, Nademanee K. What is the sudden death syndrome in Southeast Asian males? Cardiol Rev. 2000;8:90–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.World Health Organization. COVID-19 coding in ICD-10. Available at: https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/COVID-19-coding-icd10.pdf?ua=1. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 57.Hendren NS, Drazner MH, Bozkurt B, et al. Description and proposed management of the acute COVID-19 cardiovascular syndrome. Circulation. 2020;141:1903–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poissy J, Goutay J, Caplan M, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19: awareness of an increased prevalence. Circulation. 2020;142:184–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haberman R, Axelrad J, Chen A, et al. Covid-19 in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases–case series from New York. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:85–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guzik TJ, Mohiddin SA, Dimarco A, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1666–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135:2033–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jin M, Tong Q. Rhabdomyolysis as potential late complication associated with COVID-19. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1618–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Symptoms of coronavirus. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 68.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal disease. Pneumococcal vaccination. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/vaccination.html. Accessed October 26, 2020

- 69.Sundaram V, Fang JC. Gastrointestinal and liver issues in heart failure. Circulation. 2016;133:1696–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hajduk AM, Kiefe CI, Person SD, et al. Cognitive change in heart failure: a systematic review. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:451–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Felker GM, Kiefe LK, O'Connor CM. A standardized definition of ischemic cardiomyopathy for use in clinical research. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hansen JE, Sue DY, Wasserman K. Predicted values for clinical exercise testing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:S49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY, et al. Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation: Including Pathophysiology and Clinical Applications. 1999. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.