Abstract

Objectives

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) remains a global challenge. Corticosteroids constitute a group of anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs that are widely used in the treatment of COVID-19. Comprehensive reviews investigating the comparative proportion and efficacy of corticosteroid use are scarce. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials to evaluate the proportion and efficacy of corticosteroid use for the treatment of COVID-19.

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive literature review and meta-analysis of research articles, including observational studies and clinical trials, by searching the PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry, and China Academic Journal Network Publishing databases. Patients treated between December 1, 2019, and January 1, 2021, were included. The outcome measures were the proportion of patients treated with corticosteroids, viral clearance and mortality. The effect size with the associated 95% confidence interval is reported as the weighted mean difference for continuous outcomes and the odds ratio for dichotomous outcomes.

Results

Fifty-two trials involving 15710 patients were included. The meta-analysis demonstrated that the proportion of COVID-19 patients who received corticosteroids was significantly lower than that of patients who did not receive corticosteroids (35.19% vs. 64.49%). In addition, our meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in the proportions of severe and nonsevere cases treated with corticosteroids (27.91% vs. 20.91%). We also performed subgroup analyses stratified by whether patients stayed in the intensive care unit (ICU) and found that the proportion of patients who received corticosteroids was significantly higher among those who stayed in the ICU than among those who did not. The results of our meta-analysis indicate that corticosteroid treatment significantly delayed the viral clearance time. Finally, our meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in the use of corticosteroids for COVID-19 between patients who died and those who survived. This result indicates that mortality is not correlated with corticosteroid therapy.

Conclusion

The proportion of COVID-19 patients who received corticosteroids was significantly lower than that of patients who did not receive corticosteroids. Corticosteroid use in subjects with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infections delayed viral clearance and did not convincingly improve survival; therefore, corticosteroids should be used with extreme caution in the treatment of COVID-19.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a novel viral respiratory disease that surfaced in December 2019 and is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a novel, highly diverse, enveloped, positive single-stranded betacoronavirus that belongs to the subgenus Sarbecovirus [1]. The rapid progression of the COVID-19 pandemic has become a global concern. By March 11, 2020, Central European Time, 114 countries had become involved, 118319 laboratory-confirmed infections had been reported, over 4000 deaths had occurred, and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic [2]. By June 15, 2020, approximately 7823289 laboratory-confirmed cases had been identified worldwide, with 431541 deaths. Worryingly, the number of newly diagnosed patients continues to dramatically increase [3].

The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in humans resemble those of viral pneumonia [4]. The pathogenesis of viral pneumonia may not be virus-induced cytopathy but rather an aberrant host immune reaction (e.g., cytokine storm) to the viral infection in all affected patients [5]. Because the immune pathogenesis of pneumonia may be the same in all infected patients, the timing of immunomodulator (corticosteroid) treatment is crucial, and the early control of initial immune-mediated lung injury is helpful for reducing patient morbidity and possible mortality [5]. Corticosteroids do not directly inhibit virus replication, and their main role is inhibiting inflammation and suppressing the immune response [6].

A wide range of variability in COVID-19 severity has been observed, ranging from asymptomatic to critical, and the symptoms of the disease are nonspecific, including self-reported fever, dry cough, fatigue, and myalgia with diarrhea. Severe cases of difficulty breathing, sepsis, and septic shock have been reported, progressing to a severe form of pneumonia in 10–15% of patients. Severe COVID-19 can lead to critical illness, with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multiorgan failure (MOF) as the primary complications, as well as fatal respiratory diseases [7]. Its epidemiological and clinical characteristics are slowly becoming evident. However, the pathogenic features of acute lung injury in COVID-19 and other infectious respiratory diseases remain unknown. Given the rapid emergence of COVID-19, currently, no pharmacological therapies with proven efficacy are available to treat this fatal disease [8]. Several companies have produced vaccines, but these vaccines are in phase 2 or 3 clinical trials, and the exact effect of these vaccines remains to be observed in the future [9]. SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) share many genetic features; particularly, SARS-CoV-2 is highly homologous to SARS-CoV [10]. The phylogenetics and clinical features of COVID-19 resemble those of SARS and MERS; however, corticosteroid therapy in the latter two infections is controversial [11, 12]. The current guidance from the WHO regarding the clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when SARS-CoV-2 infection is suspected (released: September 2, 2020) advises the use of systemic corticosteroids rather than no corticosteroids for the treatment of patients with severe and critical cases of COVID-19; however, the guidelines suggest not using corticosteroids in the treatment of patients with nonsevere cases of COVID-19 [13, 14]. Additionally, dexamethasone, which is a corticosteroid, has been found to improve survival in hospitalized patients who require supplemental oxygen, with the greatest effect observed in patients who required mechanical ventilation. Therefore, the use of dexamethasone is strongly recommended in this setting by the COVID-19 treatment Guidelines of the National Institutes of Health (last update: November 3, 2020) [15]. There have been several reports regarding the use of corticosteroids in addition to other therapeutics in patients with COVID-19, especially in persons with severe infection hospitalized in the intensive care unit (ICU); their impact on clinical outcomes remains highly controversial [8, 16, 17]. However, to date, data regarding the proportion and efficacy of corticosteroids in this setting are scarce [18, 19]. Understanding the evidence related to the efficacy and safety of corticosteroid treatment for COVID-19 is of immediate clinical importance. This meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the proportion and efficacy of the current options for the use of systemic corticosteroid therapy for COVID-19.

Materials and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) protocols but were not registered in any registry.

Search strategy

Two researchers (JN Wang and WX Yang) independently searched the PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Controlled Trials Registry, and China Academic Journal Network Publishing databases from December 1, 2019, to January 1, 2021, using the following key words: glucocorticoid or corticosteroid or adrenal cortex hormones or steroid or corticoid or corticoids or corticosteroids or glucocorticosteroid or glucocorticosteroids or methylprednisolone or budesonide or dexamethasone or Prednisone or prednisolone or methylprednisolone or hydrocortisone or cortisol. Each key word was searched with the following string of key words (using the “AND” operator): COVID-19 OR coronavirus OR "SARS-CoV-2" OR "novel coronavirus" OR 2019-nCoV OR "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2" OR "Corona Virus Disease 2019" OR COVID-19 OR COVID. No language restrictions were applied while searching for published studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) research articles, including observational studies and clinical trials, investigating the use of glucocorticoids in persons with COVID-19 infection who were diagnosed by real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and underwent chest X-ray or chest computed tomography (CT) examination during hospitalization; (2) articles reporting outcomes regarding the proportion of glucocorticoids administered by severity and region, COVID-19 viral clearance and/or death; and (3) studies without restrictions based on the country in which the trial occurred and age.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) studies involving patients post-transplantation or with a history of any organ transplantation; 2) studies that did not report original data, clear diagnostic criteria or data that could be summarized as the mean and standard deviation, and studies lacking reliable clinical data; and 3) conference abstracts or review articles.

Disagreements regarding the study selections were resolved by discussion with a review author (YK Wang) until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Two researchers (Yao Lu and JN Wang) independently performed the data extraction. The means were obtained from data tables or figures if no direct data were available in the article text or from the corresponding author. If the sample mean and standard deviation of the data could not be obtained from the authors, they were calculated from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range according to the procedures described in the articles by Wan X and Luo D et al [20, 21]. Disagreements regarding the data extraction were resolved by discussion with a review author (YK Wang) until a consensus was reached. The extracted data included the following: research type, author names, country, date of publication, sample size, number of patients treated with corticosteroids, dosage, duration and combination drugs, number of ICU admissions, invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV)/noninvasive ventilation (NIV), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), number of deaths, mortality, viral clearance time, comorbidity, classification, and length of in-hospital stay. The severity of COVID-19 was categorized as mild, common, severe or critical. The mild type was defined by mild symptoms, including any of the various signs and symptoms of COVID-19 (e.g., fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and loss of taste and smell) without shortness of breath, dyspnea, or pneumonia on imaging. The common type was defined by respiratory tract symptoms and pneumonia on imaging. The severe type was characterized by dyspnea, respiratory rate ≥30/minute, blood oxygen saturation ≤93%, PaO2/FiO2 ratio <300, and/or >50% lung infiltration within 24–48 hours. The critical type was characterized by respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction/failure. We classified severe and critical cases as severe and common and mild cases as nonsevere. Finally, the data were imported into Review Manager 5.3 for the analysis.

Assessment of study quality

Two researchers (PW Chen and JB Guo) independently assessed the quality of the included studies. The risk of bias was evaluated using the modified Jadad scale [22]. The following categories were included: “Was the study described as randomized?”, “Was the method used to generate the sequence of randomization described and appropriate (random numbers, computer-generated, etc.)?”, “Was the study described as double-blind?”, “Was the method of double-blinding described and appropriate (identical placebo, active placebo, dummy, etc.)?”, and “Was there a description of withdrawals and drop-outs?”. The Jadad scale is a five-point scale; a score of zero indicates poor quality evidence, and a score of five indicates high-quality evidence; therefore, trials with a score of 4 or 5 were considered to be of high methodological quality. Additionally, the Cochrane collaboration tool was used to address the risk of bias. Disagreements regarding the study quality were resolved by discussion with a review author (YK Wang) until a consensus was reached.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Cochrane Collaboration software Review Manager 5.3. The weighted mean difference (WMD) and the associated 95% confidence interval (CI) of the viral clearance as a continuous outcome were calculated, while the odds ratio (OR) and the associated 95% CI of dichotomous outcomes, including the proportion of cases treated with glucocorticoids and the mortality rate, were calculated.

Heterogeneity was assessed using an I2-test. A fixed-effects model was used to pool the data if there was no evidence of significant heterogeneity (I2≤50%). Otherwise, a random-effects model was used. Publication bias was assessed with funnel plots. The subgroup analyses were stratified by area (Wuhan, China; outside of Wuhan, China; and outside of China), severity (critical and severe), evidence grade age (pediatric or adult) and glucocorticoid dosage.

Ethics committee and/or institutional board approval were not required for this study.

Results

Trial characteristics

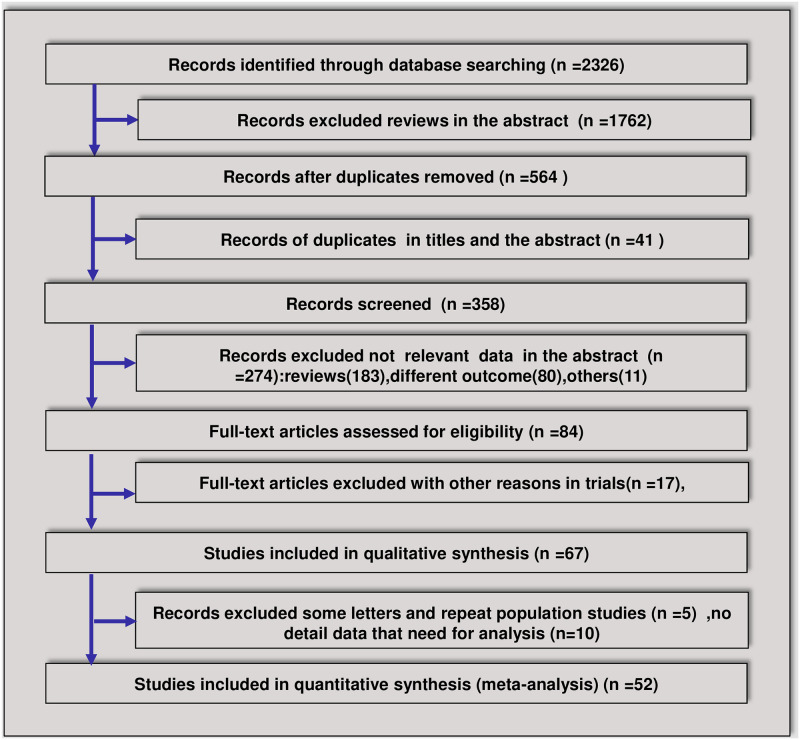

The searches identified 2326 relevant articles. Of these articles, 52 were eligible for inclusion according to our criteria for considering studies for this meta-analysis [18, 19, 23–72] (Fig 1). Forty-four trials were retrospective case series (RCS), and eight trials were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). In total, 11 RCT protocols were not included due to the lack of results (S1 File). In total, 15710 patients with COVID-19 were included in the analyses. Among the 52 included trials, 18 were multicenter trials, and 35 were single-center trials. Twenty-six trials were conducted in Wuhan, China, 17 trials were conducted outside of Wuhan, China, and 9 trials were conducted outside of China. In total, 12 studies performed analyses by severity; 4 trials divided the patients into ICU and non-ICU groups, and 8 trials divided the patients into severe or nonsevere groups. Viral clearance was compared in 5 trials. The effect on mortality was analyzed in 15 trials. Most trials indicated that 40–80 mg of methylprednisolone was used once or twice per day, ranging from 4–15 days. Antibiotics were not administered in three trials, 1 trial had no antibiotic-related data, and 51 trials administered antibiotics. In total, NIV was used in 2193 patients and IMV was used in 4729 patients in 27 trials to assist ventilation (S3 Fig). In total, 80 patients in 14 trials were treated with ECMO. Overall, 32 patients were included in Jacobs J et al’s article, and 4 of 5 survivors received steroids [29]. ECMO plays a role in the stabilization and survival of select critically ill patients with severe pulmonary and cardiac compromise; however, determining whether ECMO supplemented with corticosteroids is useful for improving the survival rate still requires more research. The most common complications were ARDS, acute coagulopathy, acute liver injury and acute kidney injury. The characteristics of the 52 included trials are summarized in Table 1.

Fig 1. Flowchart of the article screening and selection process.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Study | Design | Age | Males (%) | Region | Site | Dose and duration | Combination drugs | Classification | Complications (%) | IMV/NIV | EC | ICU | Deaths | Hospitalization time | Follow up | Jadad scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MO | ||||||||||||||||

| Angus D [70] 2020 | RCT | 60 | 273 (71) | 121 sites in 8 countries | Multiple centers | Hydrocortisone fixed 7 days (50 mg or 100 mg every 6 hours) and a shock-dependent course (50 mg every 6 hours) | Antiviral or immunoglobulin therapy and therapeutic anticoagulation | 384 severe | Respiratory failure | 213/114 | 3 | 384 | 21 | NA | 5 | |

| ARDS | ||||||||||||||||

| Heart failure | ||||||||||||||||

| Shock | ||||||||||||||||

| Bai P [65] 2020 | RCS | 62.1 (30–92) | 28 (48.3) | Wuhan, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic and antiviral therapy | 36 severe/22 critical | NA | 7/NA | 3 | 7 (28) | NA | NA | 3 | |

| Bruno M [67] 2020. | RCT | 60.1 ±15.8 | 187 (63.5) | Brazil | Multiple centers | Dexamethasone 20 mg/day, 5 days, 10 mg/day, 5 days or until ICU discharge | Hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, other antibiotics, oseltamivir | moderate or severe | ARDS | 187 | 187 | 176 | 28 | NA | 5 | |

| Heart failure | ||||||||||||||||

| Kidney failure | ||||||||||||||||

| Cao B [66] 2020 | RCT | 58.0 (49–68) | 120 (60.3) | Shanghai, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic and antiviral therapy | 199 severe | Sepsis | 32/29 | 4 | NA | 44 (28) | 28 | NA | 5 |

| Respiratory failure | ||||||||||||||||

| ARDS | ||||||||||||||||

| Heart failure | ||||||||||||||||

| Septic shock | ||||||||||||||||

| Coagulopathy | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute kidney injury | ||||||||||||||||

| Cao J [23] 2020 | RCS | 54.0 (37–67) | 53 (52.0) | Wuhan, China | Single center | NA | Antiviral, antibiotic, and intravenous immunotherapy and Chinese medicine | NA | Shock 10 (9.8) | 14/5 | 3 | 18 | 17 (15) | 11 (7–15) | NA | 3 |

| ARDS 20 (19.6) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute infection 17 (16.7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute cardiac injury 15 (14.7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Arrhythmia 18 (17.6) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute kidney injury 20 (19.6) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute liver injury 34 (33.3) | ||||||||||||||||

| Chen N [24] 2020 | RCS | 55.5 (21–82) | 67 (68.0) | Wuhan, China | Single center | 1–2 mg/kg/day; 3–15 days (median, 5 [3–7]). | Antibiotic, antifungal, antiviral and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy | 2 severe | ARDS 17 (17) | 4/13 | 3 | 23 | 11 (20) | NA | NA | 3 |

| Acute renal injury 3 (3) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute respiratory injury 8 (8) | ||||||||||||||||

| Septic shock 4 (4) | ||||||||||||||||

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia 1 (1) | ||||||||||||||||

| Chen T [54] 2020 | RCS | 54 (20–91) | 108 (53.2) | Wuhan, China | Single center | 40–80 mg/day; 3–5 days | Expectorant, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 36 severe/34 critical | ARDS 18 (69.2) | 39 | NA | 26 (40) | 11 (1–45) | NA | 3 | |

| Sepsis/shock | ||||||||||||||||

| Heart failure | ||||||||||||||||

| Deng Y [55] 2020 | RCS | 54.5 (33–74) | 124 (55.1) | Wuhan, China | Two tertiary hospitals | NA | Antibiotics antifungal and immunoglobulin therapy | 95 severe | ARDS 98 (89.9) | 21/68 | 2 | NA | 109 (50) | 8–16 | NA | 3 |

| Acute cardiac injury 65 (59.6) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute kidney injury 20 (18.3) | ||||||||||||||||

| Shock 13 (11.9) | ||||||||||||||||

| Disseminated intravascular | ||||||||||||||||

| coagulation 7 (6.4) | ||||||||||||||||

| Dequin P [69] 2020 | RCT | 62.2 | 108 (69.8) | France | Multiple centers | Hydrocortisone 200 mg/d 7 days then decreased to 100 mg/d for 4 days and 50 mg/d for 3 days for a total of 14 days | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 149 critical | ARDS | 121/4 | 4 | 149 | 76 | 21 | NA | 5 |

| Sequential organ failure | ||||||||||||||||

| Ding Q [25] 2020 | RCS | 50.2 (39–66) | 2 (40) | Wuhan, China | Cluster of cases | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral and transient hemostatic medication therapy | 1 severe | ARDS 1 (20) | 0/1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12–30 | NA | 1 |

| Acute liver injury 3 (60) | ||||||||||||||||

| Diarrhea 2 (40) | ||||||||||||||||

| Du Y [26] 2020 | RCS | 65.8±14.2 | 62 (72.9) | Wuhan, China | Two hospitals | NA | Antibiotic, antifungal, antiviral, interferon and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy | 60 mild/25 severe | Respiratory failure 80 (94.1) | 18/61 | 0 | NA | 85 (37) | 6.35 ± 4.51 | 36 | 3 |

| Shock 69 (81.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| ARDS 63 (74.1) | ||||||||||||||||

| Arrhythmia 51 (60) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute cardiac injury 38 (44.7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute liver injury 30 (35.3) | ||||||||||||||||

| Sepsis 28 (32.9) | ||||||||||||||||

| Emmi G [48] 2020 | RCS | 42 (36–48) | 2 (15.4) | Tuscany, Italy | Single center | Prednisone equivalent (1.5–5) mg/day | Hydroxychloroquine, anti-rheumatic drugs and immunoglobulin therapy | 1 severe | ARDS 1 (7.6) | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA | 14 | 3 |

| Fang X [27] 2020 | RCS | 45.5 (24–74) | 44 (56.4) | Anhui, China | Single center | Methylprednisolone 38–40 mg/day | Antiviral therapy, Chinese medicine | 23 severe | ARDS 9 (11.5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 |

| Gao T [38] 2020 | RCS | 41.0±16.4 | 19 (47.5) | Xianyang, Liancheng, China | Two hospitals | Methylprednisolone 40~80 mg/time, twice/day | Antibiotic, antifungal, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 3 mild/36 common/1 severe | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0 | NA | NA | 3 |

| G uan W [46] 2020 | RCS | 47.0 (35–58) | 640 (58.2) | Mainland, China | 552 hospitals in 30 provinces | NA | Antibiotic, antifungal, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 52 severe | Septic shock 12 (1.1) | 25/56 | 5 | 55 | 15 (15) | 12.0 (10.0–14.0) | NA | 3 |

| ARDS 37 (3.4) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute kidney injury 6 (0.5) | ||||||||||||||||

| Disseminated intravascular | ||||||||||||||||

| coagulation 1 (0.1) | ||||||||||||||||

| Guo T [44] 2020 | RCS | 58.5 ±14.66 | 91 (48.7) | Wuhan, China | Single center | Methylprednisolone 40–80 mg every day | Antiviral, antibiotic, immune glucocorticoid therapy | NA | ARDS 46 (24.6) | 45 | NA | NA | 43 (30) | 16.63 ± 8.12 | NA | 3 |

| Acute coagulopathy 42 (34.1) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute liver injury 19 (15.4) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute kidney injury 18 (14.6) | ||||||||||||||||

| Han Y [28] 2020 | RCS | 57.3 (44–81) | 1 (33.3) | Wuhan, Yiyang, China | Familial cluster | Prednisone 7.5 mg/d and steroids 80 mg/d | Antibiotic, antiviral, interferon and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy | 1 severe | NA | NA | NA | 1 | NA | NA | NA | 1 |

| Hong K [47] 2020 | RCS | 55.4±17.1 | 38 (38.8) | Daegu, South Korea | Single center | Methylprednisolone 40–80 mg every day | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | NA | ARDS 18 (18.4) | NA | NA | 13 | 5 | NA | NA | 3 |

| Septic shock 9 (9.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute cardiac injury 11 (11.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute kidney injury 9 (9.2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Huang C [62] 2020 | RCS | 49 (41–58) | 30 (73) | Wuhan, China | Single center | Methylprednisolone 40–120 mg per day | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | NA | ARDS 12 (29) | 2/10 | 2 | 6 (17) | NA | NA | 4 | |

| Acute cardiac injury 5 (12) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute kidney injury 3 (7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Secondary infection 4 (10) | ||||||||||||||||

| Shock 3 (7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Huang Q [61] 2020 | RCS | 41 (31–51) | 28 (51.9) | Wuhan, China | Four hospitals | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 51 common/3 severe | ARDS 3 (5.6) | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 9 (7–12) | NA | 3 |

| Jeronimo C [68] 2020 | RCT | 55±15 | 254 (64.6) | Manaus, Brazil | Single center | Methylprednisolone 0.5 mg/kg bid, 5 days | Antibiotic and antiviral therapy | 393 severe or critical | NA | 133/138 | 126 | 148 | 28 | NA | 5 | |

| Jacobs J [29] 2020 | RCS | 52 (12–49) | 22 (68.8) | Unites States | 9 different hospitals | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 32 critical | Pulmonary failure | NA | 32 | 10 (23) | 24 | NA | 3 | |

| Heart failure | ||||||||||||||||

| ARDS | ||||||||||||||||

| Li Q [71] 2020 | RCS | 59 (43–70) | 258 (54.3) | Shanghai, China | 19 different hospitals | Methylprednisolone 20–40 mg/day, 3–5 days | Antibiotic, antifungal, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 475 nonsevere | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 50 | NA | 3 |

| Li R [30] 2020 | RCS | 50 ± 14 | 120 (53.3) | Wuhan, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 37 severe | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 |

| Li X [31] 2020 | RCS | 60 (48–69) | 279 (50.9) | Wuhan, China | Single center | Prednisone cumulative dose, 200 (0–450) mg, 4 days | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 153 severe | ARDS 210 (38.3) | 25/78 | NA | NA | 90 (37) | NA | 38 | 3 |

| Cardiac injury 119 (21.7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Liver dysfunction 106 (19.3) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute kidney injury 95 (17.3) | ||||||||||||||||

| Bacteremia 42 (7.7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Liu J [40] 2020 | RCS | 64 (54–73) | 452 (58.4) | China | Multiple centers | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 774 severe | ARDS | 119/157 | 7 | 277 | 290 | 32 | NA | 3 |

| Myocardial | ||||||||||||||||

| Liver injury | ||||||||||||||||

| Shock | ||||||||||||||||

| Lian J [32] 2020 | RCS | 41.15±11.38 (<60) | 407 (51.6) | Wuhan, China | Single center | Methylprednisolone 40–80 mg/daily, 15 days | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 710 mild/61 severe/17 critical | ARDS 58 | 11/7 | 0 | 86 | 0 | NA | NA | 3 |

| Septic shock 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Abnormal liver function 82 | ||||||||||||||||

| 68.28±7.314 (≥60) | Acute kidney injury 13 | |||||||||||||||

| Lian JS [56] 2020 | RCS | 45 (5–88) | 243 (52.3) | Zhejiang, China | Multiple centers | Methylprednisolone 40 (40–80), 7 days | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 20 mild/ 396 common) | ARDS 11 (2.37) | 4/4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | NA | NA | 3 |

| 41severe/critical | Shock 1 (0.22) | |||||||||||||||

| Liver injury 61 (13.12) | ||||||||||||||||

| Ling Y [33] 2020 | RCS | 44.0 (34–62) | 28 (42.4) | Shanghai, China | Single center | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 14 | 3 |

| Luo P [50] 2020 | RCS | 73 (62–80) | 12 (80.0) | Wuhan, China | Single center | Methylprednisolone 40 mg bid | Tocilizumab treatment | 2 common /6 severe/7 critical | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 (38) | NA | NA | 3 |

| Mo P [34] 2020 | RCS | 54 (42–66) | 86 (55.5) | Wuhan, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral, interferon and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy | 63 common /55sever/37critical | Severe pneumonia | 36 | NA | NA | 22 (40) | 10 | 50 | 3 |

| Pulmonary edema | ||||||||||||||||

| ARDS | ||||||||||||||||

| Multiple organ failure | ||||||||||||||||

| Ni Q [39] 2020 | RCS | 52 (45–62) | 29 (56.9) | Zhejiang, China | Single center | Methylprednisolone 0.75~1.50 mg/d | Antibiotic, antiviral, and immunoglobulin therapy | 13 common | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 |

| 26severe/12critical | ||||||||||||||||

| Pang X [37] 2020 | RCS | 45. 1 (5–91) | 45 (57) | Anhui, China | Single center | 1–2 mg/kg/d, more than 5 days | Antibiotic, antiviral, and immunoglobulin therapy | 55 common /21 severe/3 critical | Severe pneumonia | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 (27) | NA | 3 | |

| Pulmonary edema | ||||||||||||||||

| ARDS | ||||||||||||||||

| Multiple organ failure | ||||||||||||||||

| Peter H [72] 2020 | RCT | 66.1 | 4112 (64) | United Kingdom | Multiple centers | Dexamethasone 6 mg/day, 10 days | Antibiotic, antiviral, and immunoglobulin therapy | NA | NA | 1007/3883 | NA | NA | 1147 | 28 | 28 | 5 |

| Petersen M [49] 2020 | RCT | 57 (52–75) | 23 (79) | Denmark | Multiple centers | Hydrocortisone 200 mg/d, 7 days | Antibiotic, antiviral, and immunoglobulin therapy | Sepsis | 15 | NA | NA | 8 | 28 | 365 | 5 | |

| Shock | ||||||||||||||||

| Fungal | ||||||||||||||||

| Infection | ||||||||||||||||

| Qiu C [57] 2020 | RCS | 43 (8–84) | 49 (47.1) | Wuhan, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral, and immunoglobulin therapy | 16 severe | ARDS 12 (11.54) | 3/4 | NA | 9 | 1 (32) | 10.45±3.79 | 33 | 3 |

| Acute kidney injury 2 (1.92) | ||||||||||||||||

| Abnormal liver function 5 (4.81) | ||||||||||||||||

| Cardiac injury 3 (2.14) | ||||||||||||||||

| Shock 2 (1.92) | ||||||||||||||||

| Shen Q [41] 2020 (children) | RCS | 7.6 (1–12) | 3 (25) | Changsha, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral, and immunoglobulin therapy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12–16 | 49 | 1 |

| Sun L [51] 2020 | RCS | 44.0 (34–56) | 31 (56.4) | Beijing, China | Single center | 40–80 mg/day | Antibiotic, antiviral, interferon, and immunoglobulin therapy and Chinese medicine | 40 mild/ common, 15 severe/ critical | Abnormal liver and kidney function | 3/5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 3 | |

| Wan S [42] 2020 | RCS | 47 (36–55) | 72 (53.3) | Chongqing, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral, and immunoglobulin therapy and Chinese medicine | 95 mild /40 severe | ARDS 21 (15.6) | 34/1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16) | NA | NA | 3 |

| Acute cardiac injury 10 (7.4) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute kidney injury 5 (3.7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Secondary infection 7 (17.5) | ||||||||||||||||

| Shock 1 (0.7) | ||||||||||||||||

| Wang D [35] 2020 | RCS | 56 (22–92) | 75 (54.3) | Wuhan, China | Single center | NA | Oseltamivir and antibacterial therapy | NA | ARDS | 17/15 | 4 | 26 | 6 (27) | NA | 34 | 3 |

| Wang L [58] 2020 | RCS | 42 (34–53) | 11 (42.3) | Shandong, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral, and immunoglobulin therapy, Chinese medicine, and gastric mucosal protection | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3 |

| Wang Y [18] 2020 | RCS | 54 (48, 64) | 26 (57) | Wuhan, China | Single center | Methylprednisolone 1–2 mg/kg/day for 5–7 days | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 46 severe | NA | 7/3 | 0 | 46 | 3 (36) | NA | NA | 3 |

| Wang YM [52] 2020 | RCT | 65 (56–71) | 89 (56) | Hubei, China | Ten hospitals | 8 days | Antibiotic, antiviral, interferon, vasopressor and immunoglobulin therapy | NA | ARDS 22 | 21/17 | 2 | NA | 32 (35) | 8 (6–9) vs 15 (9–19) | 64 | 5 |

| Pulmonary embolism 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cardiac arrest 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Septic shock 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Wu C [19] 2020 | RCS | 51 (43–60) | 128 (63.7) | Wuhan, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral, interferon, antioxidant and immunoglobulin therapy | NA | ARDS 84 (41.8) | 61/5 | 1 | 53 | 44 (32) | 13 (10–16) | 50 | 3 |

| Xu K [53] 2020 | RCS | 52 (43, 63) | 66 (58.4) | Wuhan, China | Single center | Methylprednisolone 0.5–1 mg/kg | Antiviral, interferon and immunoglobulin therapy | 32 severe/23 critical | ARDS 23 | 0/18 | 21 | NA | 3 | |||

| Yang W [59] 2020 | RS | 45.11 ± 13.35 | 81 (54.4) | Zhejiang, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral, interferon and immunoglobulin therapy | NA | NA | 2/0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 29 | 3 |

| Yang X [64] 2020 | RCS | 59 ±13 | 35 (67) | Wuhan, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral, vasoconstrictive and immunoglobulin therapy | 52 critical | ARDS 35 (67) | 22/29 | 6 | 52 | 32 (26) | NA | NA | 3 |

| Acute kidney injury 15 (29) | ||||||||||||||||

| Cardiac injury 12 (23) | ||||||||||||||||

| Liver dysfunction 15 (29) | ||||||||||||||||

| Pneumothorax 1 (2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Zha L [36] 2020 | RCS | 39 (32–54) | 20 (64%) | Wuhu, Anhui province, China | Two designated hospitals | Methylprednisolone 40 mg once or twice per day | Antibiotics, moxifloxacin, lopinavir/ritonavir and interferon alfa; umifenovir, lopinavir/ritonavir and interferon alfa | NA | Liver injury 12 (39) | NA | NA | NA | 0 | 18.5 (16–21) | NA | 3 |

| 5 days (iqr, 4.5–5.0 days) | ||||||||||||||||

| Zhang Y [43] 2020 | RCS | 62.7±14.2 | 85 (51.2) | Wuhan, China | Single center | Methylprednisolone 1–2 mg/kg/d, 3–7 days | Antibiotic, antiviral, and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy and tocilizumab | 100 severe/36 critical | Acute kidney injury | 22/11 | 7 | 24 (41) | 23.0±12.2 | NA | 3 | |

| Cardiac injury | ||||||||||||||||

| Zhao X [60] 2020 | RCS | 46.00 | 49 (53.8) | Jingzhou, China | Single center | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 61 mild/30 severe | Cardiovascular jury 14 (15.4) | 5 | NA | NA | 2 (25) | NA | 25 | 3 |

| Digestive tract jury 14 (15.4) | ||||||||||||||||

| Liver jury 18 (19.8) | ||||||||||||||||

| Renal jury 5 (5.5) | ||||||||||||||||

| Coagulation dysfunction 19 (20.9) | ||||||||||||||||

| Zheng F [45] 2020 | RCS | 3 (2–9) | 14 (56.0) | Hubei, China | 10 hospitals | 2 mg/kg/day | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 15 mild/2 critical | ARDS | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | NA | NA | 3 |

| Zhou F [63] 2020 | RCS | 56 (46–67) | 119 (62) | Wuhan, China | 2 hospitals | NA | Antibiotic, antiviral and immunoglobulin therapy | 66 severe/53 critical | Sepsis 112 (59) | 32/6 | 3 | 50 | 54 (33) | 11 (7–14) | NA | 3 |

| Respiratory failure 103 (54) | ||||||||||||||||

| ARDS 59 (31) | ||||||||||||||||

| Heart failure 44 (23) | ||||||||||||||||

| Septic shock 38 (20) | ||||||||||||||||

| Coagulopathy 37 (19) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute cardiac injury 33 (17) | ||||||||||||||||

| Acute kidney injury 28 (15) |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; RCS, retrospective case series; RCT, randomized controlled trial. Age (median/mean [range/IQR], years); length of in-hospital stay (median/mean [range/IQR].

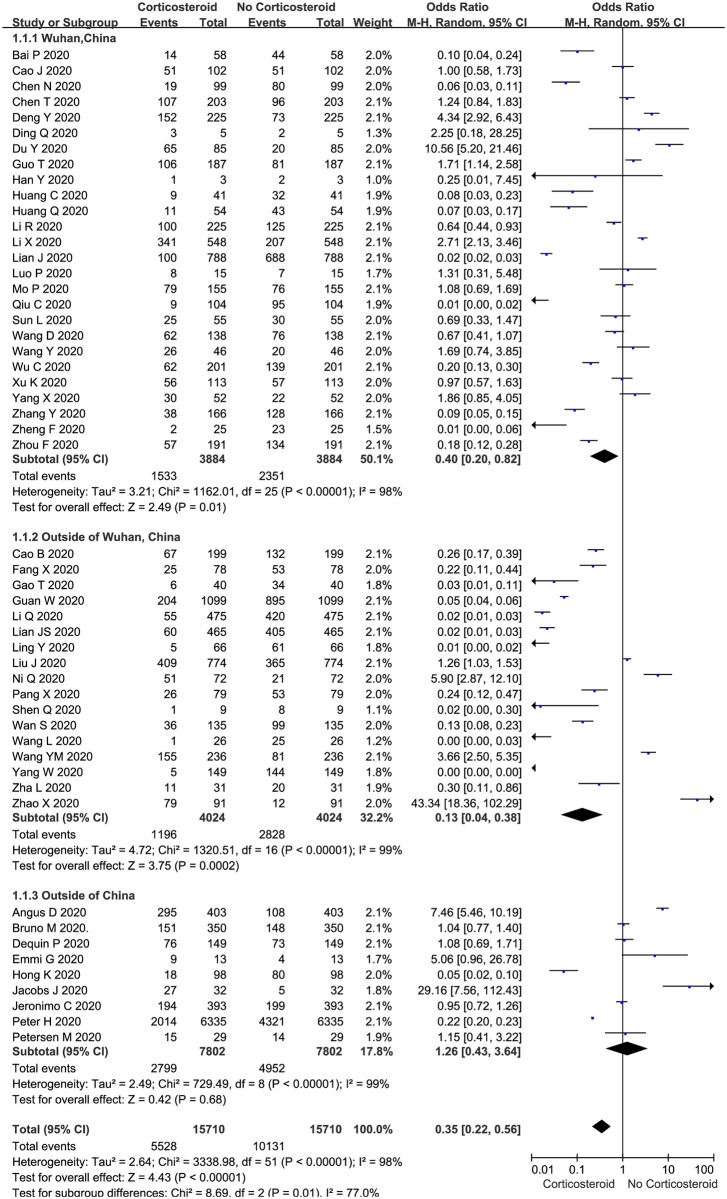

Proportion of corticosteroid treatments

The proportion of COVID-19 patients treated with corticosteroids compared to those who were not was described in all 52 included trials (n = 15710 patients). The meta-analysis demonstrated that the proportion of COVID-19 patients treated with corticosteroids was significantly lower than that of patients who were not treated with corticosteroids (35.19% vs. 64.49%, 5528 vs. 10131 OR: 0.35, 95% CI: 0.22–0.56, P <0.01; Fig 2) in both adult and pediatric cases (S4A Fig). There was evidence of significant heterogeneity among the trials (P <0.01, I2 = 98%). There was no significant difference between the patients who were treated with corticosteroids and those not treated with corticosteroids among those with low and high Jadad scores (S4B Fig).

Fig 2. Proportion of corticosteroid treatments in COVID-19 patients: Overall and subgroup analyses stratified by region.

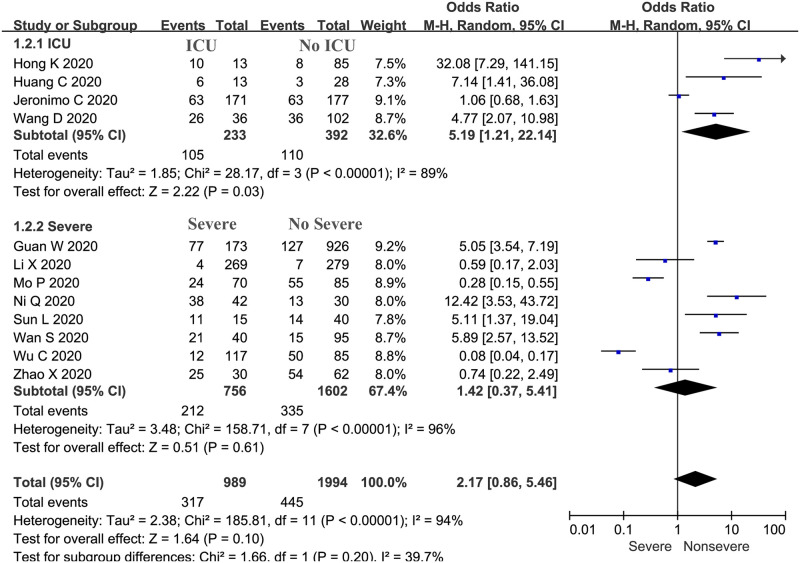

Comparison of the proportion of severe and nonsevere cases treated with corticosteroids

The proportion of severe cases treated with corticosteroids was 32.05% (n = 317), while 22.31% (n = 445) of nonsevere cases were treated with corticosteroids in 12 trials (n = 2983 patients). Our meta-analysis demonstrated a significant difference in the proportions of severe plus ICU and nonsevere plus no ICU cases treated with corticosteroids (OR: 2.17, 95% CI: 0.86–5.46, P = 0.04; Fig 3). There was evidence of significant heterogeneity among the trials (P <0.01, I2 = 94%).

Fig 3. Proportions of severe and nonsevere cases treated with corticosteroids: Overall and subgroup analyses stratified by severity.

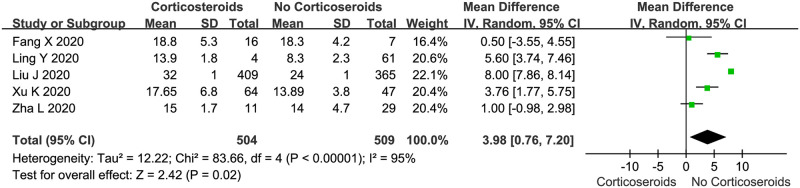

Effect of corticosteroid use on viral clearance

We evaluated the viral clearance time in patients treated with corticosteroids compared with that in patients who were not treated with corticosteroids using a random-effects model (Fig 4). Five studies reported the outcome of viral clearance. In all 5 studies, viral clearance was confirmed by serial RT-PCR of samples from throat swabs or sputum; in the 5 studies, clearance was defined as at least two consecutive negative results. The pooled estimates showed that corticosteroid treatment significantly delayed the viral clearance time (WMD: 3.98, 95% CI: 0.76–7.02, P < 0.05; I2 = 95%). However, there was significant heterogeneity among the studies.

Fig 4. Corticosteroid vs. no corticosteroid treatment: Viral clearance time (days).

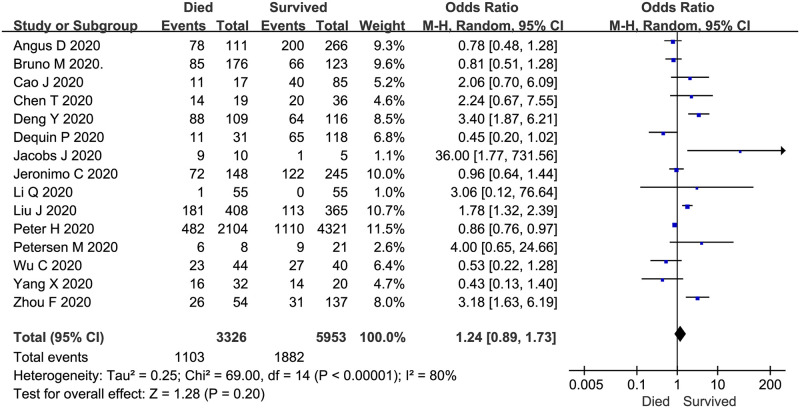

Effect of corticosteroid use on mortality

The mortality of COVID-19 patients treated with corticosteroids for 4–15 days was described in 15 trials (n = 9279 patients). The meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in the use of corticosteroids between COVID-19 patients who died and those who survived (overall OR: 1.24, 95% CI 0.89–1.73, P = 0.2; Fig 5). There was evidence of significant heterogeneity among the trials (P < 0.01, I2 = 80%).

Fig 5. Corticosteroid vs. no corticosteroid treatment: Mortality of studied subjects (both groups received corticosteroids).

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

The subgroup analyses stratified by region indicated that the proportion of COVID-19 patients treated with corticosteroids was significantly lower than that of patients who were not treated with corticosteroids in Wuhan, China (OR: 0.40, 95% CI: 0.20–0.82, P = 0.01; I2 = 98%, Fig 2) and outside of Wuhan (OR: 0.13, 95% CI: 0.04–0.38, P < 0.01; I2 = 99%, Fig 2), but there was no significant difference outside of China (OR: 1.26, 95% CI: 0.43–3.64, P = 0.68; I2 = 99%, Fig 2).

The subgroup analyses were also stratified by whether patients stayed in the ICU and by severity. Patients who were identified as having severe or critical disease were collectively included in the “severe” group, while those with mild and common COVID-19 were included in the “nonsevere” group. The subgroup analysis indicated that the proportion of patients treated with corticosteroids among ICU patients was significantly higher than that among non-ICU patients (OR: 5.19, 95% CI: 1.21–22.14, P = 0.03; I2 = 89%; Fig 3), but there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with critical or severe disease and mild or common disease treated with corticosteroids (OR: 1.42, 95% CI: 0.37–5.41, P = 0.61; I2 = 96%; Fig 3).

The subgroup analyses were also stratified by the dosage of corticosteroids and whether the patients were ventilated. The main dosage of corticosteroids used was 40–80 mg/day. The number of patients treated with corticosteroids at 40–80 mg/day was significantly lower than the number of patients not treated with corticosteroids (557 vs. 1580; S2 Fig); however, there were no significant differences in the number of patients treated by weight, treated with less than 40 mg/day, treated with more than 80 mg/day, and not treated with corticosteroids. There was also no significant difference in the number of ventilated and nonventilated patients (2193 vs. 4729; S3 Fig).

Assessment of study quality

The level of evidence in each trial was graded from 1 to 5 according to the Jadad quality score (Table 1 and S2 Table). Regarding publication bias, the shape of the funnel plot showed obvious asymmetry for trials investigating the proportion of corticosteroid use in COVID-19 patients regardless of region or severity (S1A and S1B Fig) and slight asymmetry for trials investigating the effect on viral clearance (S1C Fig) and mortality (S1D Fig).

Additionally, the risk of bias, as assessed by the Cochrane tool, is summarized in S5 Fig and presented in detail in S6 Fig. The main limitations of the included trials were selection bias and performance bias because most studies were not randomized or blinded.

Discussion

Since the outbreak of the novel SARS-CoV-2 infection, no effective antiviral treatment has been developed. COVID-19 patients are mainly treated with symptomatic therapy. In clinical practice, corticosteroids are widely used in the symptomatic treatment of severe viral pneumonia. However, whether COVID-19 patients should be adjunctively treated with corticosteroids remains highly controversial. The main pathological feature of COVID-19 pneumonia is an inflammatory reaction accompanied by deep airway and alveolar destruction [73]. The current hypothesis is that lung injury is not associated with direct virus-induced injury but that COVID-19 invasion triggers immune and inflammatory responses that lead to the activation of immune cells (macrophages, T and B lymphocytes, granulocytes, and monocytes) to release numerous pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, and markedly increased levels of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate [74]. The overwhelming secretion of cytokines causes severe alveolar and deep airway damage, which manifests as extensive damage to pulmonary vascular endothelial and alveolar epithelial cells and increased pulmonary vascular permeability, resulting in pulmonary edema and hyaline membrane formation [75]. Lung histological examinations have shown diffuse alveolar damage with cellular fibromyxoid exudate and hyaline membrane formation, which resembles ARDS [73]. Further autopsy revealed bilateral diffuse alveolar injury with fibrous mucinous exudate and interstitial mononuclear inflammatory infiltration dominated by lymphocytes, which is very similar to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections [73]. This finding indicates that COVID-19 infection is usually accompanied by increased immune and inflammatory responses and that the concentrations of immune factors are associated with the severity of the disease [62]. Corticosteroids are classical immunosuppressive drugs that perform key physiological processes, including exerting inhibitory effects on the immune response and playing anti-inflammatory roles to reduce systemic inflammation [16, 76]. Both aspects are important for stopping or delaying the progression of pneumonia. Low-dose corticosteroids have been proven to be effective in the treatment of viral pneumonia due to their excellent pharmacological effects on the suppression of the immune system to prevent the development of related autoimmune diseases and dysfunctional systematic inflammation [77].

In this meta-analysis, the proportion of COVID-19 patients treated with corticosteroids was significantly lower than that of patients who did not receive corticosteroids. The subgroup analyses stratified by region showed that the proportion of COVID-19 patients treated with corticosteroids was significantly lower than that of patients who were not in Wuhan, China, outside of Wuhan, and outside of China. The results of this study indicate that the clinical application of corticosteroids is not very common. Thus, the use of corticosteroids could be regarded as a double-edged sword [16].

Studies have indicated that patients with severe disease are more likely to require adjunctive corticosteroid therapy [77]. However, our meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in the proportion of severe and nonsevere cases treated with corticosteroids. This finding differs from the results of previous research. We speculate that the reason underlying this inconsistency is an unsuitable population selection as follows: patients with mild or common COVID-19 might not be included in a target population to assess the efficacy of corticosteroids in most studies. We also performed subgroup analyses stratified by severity, which indicated that the proportion of corticosteroid use in ICU patients was significantly higher than that in non-ICU patients. These results indicate that ICU patients were more likely to require corticosteroid therapy. The meta-analysis by Li Huan et al. reported that evidence suggests that ICU inpatients with coronavirus infections were more likely to receive corticosteroids than non-ICU inpatients [78].

The results of our meta-analysis indicate that corticosteroid treatment significantly delayed the viral clearance time. A study by Russell D.C. et al showed a delay in viral RNA clearance from the respiratory tract and suggested that this delay followed corticosteroid treatment for MERS-CoV infection [14]. Moreover, a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial investigating SARS compared early adjunctive hydrocortisone treatment (before day seven of the illness) with a placebo and showed that early adjunctive hydrocortisone therapy in patients was associated with delayed SARS-CoV RNA clearance in plasma [79].

The meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in the use of corticosteroids between COVID-19 patients who died and those who survived. These results indicate that mortality is not correlated with corticosteroid therapy; there was no favorable impact on the endpoint of death. In a retrospective cohort study involving 309 patients who were critically ill with MERS [12], the authors reported that there was no difference in 90-day mortality between patients treated with corticosteroids and those not treated with corticosteroids, but the corticosteroid treatment was associated with delayed MERS-CoV RNA clearance from respiratory tract secretions. This finding was somewhat supported by our systematic review. Glucocorticoid therapy was associated with delayed SARS-CoV-2 RNA clearance after adjusting for baseline and time-varying confounding factors [33]. However, the WHO’s rapid evidence appraisal of COVID-19 therapies by a working group conducting a prospective meta-analysis showed that in clinical trials of patients critically ill with COVID-19, compared with usual care or placebo, the administration of systemic corticosteroids was associated with a lower 28-day all-cause mortality rate [80], which differs from our results because we included mild, common and severe cases in our meta-analysis.

There are some limitations to this meta-analysis. First, some included studies were early retrospective cohort studies with small patient sample sizes and historical control studies of this emerging pathogen, and we found substantial heterogeneity among studies with a low level of evidence, which restricted the quality grade of the effects. Larger-scale RCTs are urgently needed. Second, there is no uniform standard for the dosage or initiation time of the administration of the corticosteroid regimens used in the different studies. For instance, in future research, corticosteroids should be used at an early stage of the illness. Third, antiviral agents might be confounders to corticosteroid use and their effects. Other co-treatments might have influenced our results. Fourth, our study was not registered, and the study populations only included hospitalized patients. Finally, due to the ongoing outbreak of COVID-19, many regions affected by COVID-19 have not published results in their populations, which may lead to publication bias.

Conclusions

The proportion of COVID-19 patients treated with corticosteroids was significantly lower than that of patients who were not treated with corticosteroids. The subgroup analyses stratified by severity indicated that the proportion of corticosteroid use in ICU patients was significantly higher than that in non-ICU patients. Corticosteroid use in subjects with SARS-CoV-2 infection resulted in delayed viral clearance and did not convincingly improve survival in all patients. Therefore, corticosteroids should be used with extreme caution in the treatment of COVID-19. Nevertheless, further multicenter, larger, randomized, controlled clinical trials are needed to verify this conclusion.

Supporting information

A. Funnel plot of the proportion of corticosteroid treatments in COVID-19 patients by region. B. Funnel plot of the proportion of corticosteroid treatments in COVID-19 patients by severity. C. Funnel plot of the effect of corticosteroid treatments on viral clearance in COVID-19 patients. D. Funnel plot of mortality.

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSM)

(CSV)

Abbreviations

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- CI

confidence interval

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- ICU

intensive care unit

- MOF

multiorgan failure

- OR

odds ratio

- RCTs

randomized controlled trials

- WMD

weighted mean difference

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Shaanxi Natural Science Foundation of China (Number 2019JQ-536). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Fu L, Wang B, Yuan T, Chen X, Ao Y, Fitzpatrick T, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020; 80:656–65. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report, 51 (2020). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed March, 11 2020).

- 3.World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report, 147 (2020). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed June,15 2020).

- 4.World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report, 36 (2020). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed January 15 2020).

- 5.Lee KY, Rhim JW, Kang JH. Early preemptive immunomodulators (corticosteroids) for severe pneumonia patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2020;63:117–8. 10.3345/cep.2020.00290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montón C, Ewig S, Torres A, El-Ebiary M, Filella X, Rañó A, et al. Role of glucocorticoids on inflammatory response in nonimmuno suppressed patients with pneumonia: a pilot study. Eur Respir J. 1999; 14: 218–20. 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a37.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G. Which lessons shall we learn from the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak? Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:48. 10.21037/atm.2020.02.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhong H, Wang Y, Zhang ZL, Liu YX, Le KJ, Cui M, et al. Efficacy and safety of current therapeutic options for COVID-19—lessons to be learnt from SARS and MERS epidemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2020:104872. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Clinical Trials Using ACTIV-Informed Harmonized Protocols. https://www.nih.gov/research-training/medical-research-initiatives/activ/sars-cov-2-vaccine-clinical-trials-using-activ-informed-harmonized-protocols.

- 10.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382: 727–33. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sung JJ, Wu A, Joynt GM, Yuen KY, Lee N, Chan PK, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: report of treatment and outcome after a major outbreak. Thorax. 2004; 59:414–20. 10.1136/thx.2003.014076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arabi YM, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, Sindi AA, Almekhlafi GA, Hussein MA, et al. Corticosteroid Therapy for Critically Ill Patients with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018; 197:757–67. 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Organization WH. World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): technical-guidance-publications. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance-publications.

- 14.Russell CD, Millar JE, Baillie JK. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury. Lancet. 2020; 395:473–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Therapeutic Management of Patients with COVID-19. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapeutic-management/.

- 16.Nasim S, Kumar S, Azim D, Ashraf Z, Azeem Q. Corticosteroid use for 2019-nCoV infection: A double-edged sword. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020:1–2. 10.1017/ice.2020.165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell B, Moss C, Rigg A, Van Hemelrijck M. COVID-19 and treatment with NSAIDs and corticosteroids: should we be limiting their use in the clinical setting. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020; 14:1023. 10.3332/ecancer.2020.1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Jiang W, He Q, Wang C, Wang B, Zhou P, et al. A retrospective cohort study of methylprednisolone therapy in severe patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020; 5:57. 10.1038/s41392-020-0158-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, Xu S, et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014; 14:135. 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo D, Wan X, Liu J, Tong T. Optimally estimating the sample mean from the sample size, median, mid-range, and/or mid-quartile range. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018; 27:1785–805. 10.1177/0962280216669183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary. Control Clin Trials. 1996; 17:1–12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao J, Tu WJ, Cheng W, Yu L, Liu YK, Hu X, et al. Clinical Features and Short-term Outcomes of 102 Patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020; 395:507–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ding Q, Lu P, Fan Y, Xia Y, Liu M, AUID- Oho. The clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients coinfected with 2019 novel coronavirus and influenza virus in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du Y, AUID- Oho, Tu L, Zhu P, Mu M, Wang R, et al. Clinical Features of 85 Fatal Cases of COVID-19 from Wuhan: A Retrospective Observational Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020. 10.1164/rccm.202003-0543OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang X, Mei Q, Yang T, Li L, Wang Y, Tong F, et al. Low-dose corticosteroid therapy does not delay viral clearance in patients with COVID-19. J Infect. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han Y, Jiang M, Xia D, He L, Lv X, Liao X, et al. COVID-19 in a patient with long-term use of glucocorticoids: A study of a familial cluster. Clin Immunol. 2020; 214:108413. 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs JP, Stammers AH, St Louis J, Hayanga J, Firstenberg MS, Mongero LB, et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the Treatment of Severe Pulmonary and Cardiac Compromise in COVID-19: Experience with 32 patients. ASAIO J. 2020. 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li R, Tian J, Yang F, Lv L, Yu J, Sun G, et al. Clinical characteristics of 225 patients with COVID-19 in a tertiary Hospital near Wuhan, China. J Clin Virol. 2020; 127:104363. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Xu S, Yu M, Wang K, Tao Y, Zhou Y, et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lian J, Jin X, Hao S, Cai H, Zhang S, Zheng L, et al. Analysis of Epidemiological and Clinical features in older patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) out of Wuhan. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ling Y, Xu SB, Lin YX, Tian D, Zhu ZQ, Dai FH, et al. Persistence and clearance of viral RNA in 2019 novel coronavirus disease rehabilitation patients. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020; 133:1039–43. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mo P, Xing Y, Xiao Y, Deng L, Zhao Q, Wang H, et al. Clinical characteristics of refractory COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. LID—ciaa270. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zha L, Li S, Pan L, Tefsen B, Li Y, French N, et al. Corticosteroid treatment of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Med J Aust. 2020. 10.5694/mja2.50577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pang X, Qing M, Tianjun Y, Zhang L, Yun Y, Yuzhong W, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment strategies of 79 patients with COVID. Chinese Pharmacological Bulletin. 2020;453–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao T, Xu Y L, He Xiao P, Ma Y J, Wang LZ, Jiang YD, Wu ZG, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 40 patients with coronavirus disease 2019outside Hubei. Chinese Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2020;148–53. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ni Q, Ding C, Li YT, Zhao H, Liu J, Zhang X, et al. Retrospective study of low-to-moderate dose glucocorticoids on viral clearance in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chinese Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020;E009-009E009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu J, Zhang S, Dong X, Li Z, Xu Q, Feng H, et al. Corticosteroid treatment in severe COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2020; 130:6417–28. 10.1172/JCI140617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen Q, Guo W, Guo T, Li J, He W, Ni S, et al. Novel coronavirus infection in children outside of Wuhan, China. Pediatric PulmonologyPediatric PulmonologyPediatric Pulmonology. 2020; 55:1424–9. 10.1002/ppul.24762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wan S, Xiang Y, Fang W, Zheng Y, Li B, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. Journal of Medical Virology. 2020; n/a:-. 10.1002/jmv.25783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Li H, Zhang J, Cao Y, Zhao X, Yu N, et al. The Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Diabetes Mellitus and Secondary Hyperglycaemia Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: a Single-center, Retrospective, Observational Study in Wuhan. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2020; 10.1111/dom.14086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, et al. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiology. 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng F, Liao C, Fan Q-H, Chen H-B, Zhao X-G, Xie Z-G, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Children with Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Hubei, China. Current medical science. 2020; 40:275–80. 10.1007/s11596-020-2172-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1708–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hong KS, Lee KH, Chung JH, Shin KC, Choi EY, Jin HJ, et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes of 98 Patients Hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Daegu, South Korea: A Brief Descriptive Study. Yonsei medical journal. 2020; 61:431–7. 10.3349/ymj.2020.61.5.431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emmi G, Bettiol A, Mattioli I, Silvestri E, Scala GD, Urban ML, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection among patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity reviewsAutoimmun Rev. 2020;102575–102575. 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petersen MW, Meyhoff TS, Helleberg M, Kjaer MN, Granholm A, Hjortso C, et al. Low-dose hydrocortisone in patients with COVID-19 and severe hypoxia (COVID STEROID) trial-Protocol and statistical analysis plan. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2020; 64:1365–75. 10.1111/aas.13673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luo P, Liu Y, Qiu L, Liu X, Liu D, Li J. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19: A single center experience. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun L, Shen L, Fan J, Gu F, Hu M, An Y, et al. Clinical Features of Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) from a Designated Hospital in Beijing, China. Journal of medical virology. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G., Du R., Zhao J, Jin Y, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. The Lancet. 2020. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu K, Chen Y, Yuan J, Yi P, Ding C, Wu W, et al. Factors associated with prolonged viral RNA shedding in patients with COVID-19. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of AmericaClin. Infect. Dis. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen T, Dai Z, Mo P, Li X, Ma Z, Song S, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of older patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China (2019): a single-centered, retrospective study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020. 10.1093/gerona/glaa089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deng Y, Liu W, Liu K, Fang YY, Shang J, Zhou L, et al. Clinical characteristics of fatal and recovered cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lian J, Jin X, Hao S, Jia H, Cai H, Zhang X, et al. Epidemiological, clinical, and virological characteristics of 465 hospitalized cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from Zhejiang province in China. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020. 10.1111/irv.12758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qiu C, Deng Z, Xiao Q, Shu Y, Deng Y, Wang H, et al. Transmission and clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in 104 outside-Wuhan patients, China. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang L, Duan Y, Zhang W, Liang J, Xu J, Zhang Y, et al. Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics of 26 Cases of COVID-19 Arising from Patient-to-Patient Transmission in Liaocheng, China. Clin Epidemiol. 2020; 12:387–91. 10.2147/CLEP.S249903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang W, Cao Q, Qin L, Wang X, Cheng Z, Pan A, et al. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19):A multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. J Infect. 2020; 80:388–93. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao XY, Xu XX, Yin HS, Hu QM, Xiong T, Tang YY, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in a non-Wuhan area of Hubei Province, China: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2020; 20:311. 10.1186/s12879-020-05010-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang Q, Deng X, Li Y, Sun X, Chen Q, Xie M, et al. Clinical characteristics and drug therapies in patients with the common-type coronavirus disease 2019 in Hunan, China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020; 395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020; 395:1054–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 8:475–81. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bai Peng HW, Zhang Xichun LS, Jianmin J. Analysis of clinical features of 58 patients with severe or critical 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chinese Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020; 29:483–7. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, Liu W, Wang J, Fan G, et al. A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020; 382:1787–99. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tomazini BM, Maia IS, Cavalcanti AB, Berwanger O, Rosa RG, Veiga VC, et al. Effect of Dexamethasone on Days Alive and Ventilator-Free in Patients With Moderate or Severe Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and COVID-19: The CoDEX Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020; 324:1307–16. 10.1001/jama.2020.17021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jeronimo C, Farias M, Val F, Sampaio VS, Alexandre M, Melo GC, et al. Methylprednisolone as Adjunctive Therapy for Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 (Metcovid): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Phase IIb, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dequin PF, Heming N, Meziani F, Plantefève G, Voiriot G, Badié J, et al. Effect of Hydrocortisone on 21-Day Mortality or Respiratory Support Among Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020; 324:1298–306. 10.1001/jama.2020.16761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Angus DC, Derde L, Al-Beidh F, Annane D, Arabi Y, Beane A, et al. Effect of Hydrocortisone on Mortality and Organ Support in Patients With Severe COVID-19: The REMAP-CAP COVID-19 Corticosteroid Domain Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020; 324:1317–29. 10.1001/jama.2020.17022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Q, Li W, Jin Y, Xu W, Huang C, Li L, et al. Efficacy Evaluation of Early, Low-Dose, Short-Term Corticosteroids in Adults Hospitalized with Non-Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Infect Dis Ther. 2020; 9:823–36. 10.1007/s40121-020-00332-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19—Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2020. 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 8:420–2. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Russell B, Moss C, George G, Santaolalla A, Cope A, Papa S, et al. Associations between immune-suppressive and stimulating drugs and novel COVID-19-a systematic review of current evidence. Ecancermedicalscience. 2020; 14:1022. 10.3332/ecancer.2020.1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cruz-Topete D, Cidlowski JA. One hormone, two actions: anti-and pro-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2015; 22:20–32. 10.1159/000362724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang Z, Liu J, Zhou Y, Zhao X, Zhao Q, Liu J. The effect of corticosteroid treatment on patients with coronavirus infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou W, Liu Y, Tian D, Wang C, Wang S, Cheng J, et al. Potential benefits of precise corticosteroids therapy for severe 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020; 5:18. 10.1038/s41392-020-0127-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li H, Chen C, Hu F, Wang J, Zhao Q, Gale RP, et al. Impact of corticosteroid therapy on outcomes of persons with SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, or MERS-CoV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leukemia. 2020; 34:1503–11. 10.1038/s41375-020-0848-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee N, Allen Chan KC, Hui DS, Ng EK, Wu A, Chiu RW, et al. Effects of early corticosteroid treatment on plasma SARS-associated Coronavirus RNA concentrations in adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2004; 31:304–9. 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sterne J, Murthy S, Diaz JV, Slutsky AS, Villar J, Angus DC, et al. Association Between Administration of Systemic Corticosteroids and Mortality Among Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020; 324:1330–41. 10.1001/jama.2020.17023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Funnel plot of the proportion of corticosteroid treatments in COVID-19 patients by region. B. Funnel plot of the proportion of corticosteroid treatments in COVID-19 patients by severity. C. Funnel plot of the effect of corticosteroid treatments on viral clearance in COVID-19 patients. D. Funnel plot of mortality.

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(DOC)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSM)

(CSV)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.