Abstract

Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) present global health threats, and their emergences are often linked to anthropogenic change. Artificial light at night (ALAN) is one form of anthropogenic change that spans beyond urban boundaries and may be relevant to EIDs through its influence on the behaviour and physiology of hosts and/or vectors. Although West Nile virus (WNV) emergence has been described as peri-urban, we hypothesized that exposure risk could also be influenced by ALAN in particular, which is testable by comparing the effects of ALAN on prevalence while controlling for other aspects of urbanization. By modelling WNV exposure among sentinel chickens in Florida, we found strong support for a nonlinear relationship between ALAN and WNV exposure risk in chickens with peak WNV risk occurring at low ALAN levels. Although our goal was not to discern how ALAN affected WNV relative to other factors, effects of ALAN on WNV exposure were stronger than other known drivers of risk (i.e. impervious surface, human population density). Ambient temperature in the month prior to sampling, but no other considered variables, strongly influenced WNV risk. These results indicate that ALAN may contribute to spatio-temporal changes in WNV risk, justifying future investigations of ALAN on other vector-borne parasites.

Keywords: light pollution, West Nile virus, zoonoses, urbanization, emerging infectious diseases, ALAN

1. Introduction

Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) are among the greatest threats to public health today [1,2]. Most EIDs are zoonotic in origin (70%), in that causative agents spill over to human populations from other species [3,4]. Anthropogenic effects on wildlife, such as habitat fragmentation, sensory pollutants and toxin exposure, can become detrimental to humans in places where humans and wildlife come into contact [5–7]. The recent surge in many EIDs can be attributed to various forms of global change, including climate change and the structure and biological composition of landscapes [3,8,9]. One recent example of an anthropogenically driven zoonotic EID is West Nile virus (WNV), which was introduced to the United States in 1999 [10]. WNV decimated susceptible bird populations, especially corvid species, within the first several years of its arrival, and its propensity to be transmitted by many vector species also made it a source of substantial human and livestock (i.e. horse) disease [11–14]. Now, 20 years since its introduction, WNV continues to cause harm to diverse animal populations, particularly in or near highly human-modified habitats [15,16].

WNV is recognized as a peri-urban arbovirus, as human incidence and songbird seroprevalence are much higher in or near urban habitats [17,18]. Historically, a higher incidence of WNV in or near cities was linked to aspects of environments that influence mosquito success such as local climate and availability of breeding sites [18,19]. The Florida Department of Health surveillance system has closely monitored arbovirus transmission in mosquito breeding hotspots, such as peri-urban drainage systems, since the late twentieth century [20,21]. WNV dynamics resemble other zoonoses in that urban and agricultural predominance affect emergence and transmission [22]. For instance, Lyme disease (caused by Borrelia burgdorferi) and flavivirus infections (including yellow fever, dengue and chikungunya) emerge where competent host and vector communities occur in close proximity to humans [23–25]. Some anthropogenic stressors have been found to affect zoonotic risk, but many conspicuous and common ones have never been considered, including light pollution. One form of light pollution, artificial light at night (ALAN), now covers 18.7% of the continental US and affects 99% of the human population with increases anticipated in the future (e.g. 2.2% increase globally per year from 2012 to 2016 [26]). Further, small areas of urban development can emit light into distant suburban and rural landscapes, suggesting that light pollution effects, and skyglow in particular, may be widespread [27,28].

Light pollution affects multiple host traits with consequences for disease transmission. For instance, in night shift workers, ALAN can affect non-communicable disease risk (e.g. cancer, diabetes, etc.) [29], probably because vertebrate immune systems are ‘fundamentally circadian in nature’ [29–31]. House sparrows, a common passerine reservoir of WNV, experimentally infected with WNV and exposed to modest ALAN (i.e. 5 lux; a full moon on a clear night is 0.3 lux) maintained transmissible WNV titres for 2 days longer than controls but did not experience higher mortality [32,33]. Epidemiologically, this extension of the infectious-to-vector period was estimated to increase outbreak potential by 41% [32]. Host population characteristics also have the capacity to alter disease transmission. For example, avian species diversity is known to affect WNV transmission, but there are no studies to our knowledge that have quantified direct effects of ALAN on avian community composition [34,35].

ALAN also probably alters a multitude of vector traits that affect arbovirus transmission. Arthropod vectors of WNV, mainly Culex spp., are renowned for their flight-to-light behaviours; for those vectors that survive desiccation or depredation, flight-to-light behaviour might concentrate infection risk where light pollution is common [36,37]. WNV can be transmitted by as many as 45 vector species, many of which bite wildlife (including songbirds) and humans, and are abundant across Florida [38–40]. WNV vectors are dense in urban areas, as surface imperviousness is one of the strongest predictors of Culex spp. distribution [41]. Interestingly, Culex spp. are more abundant in areas of moderate ALAN than low or high ALAN during late summer months during peak transmission [42].

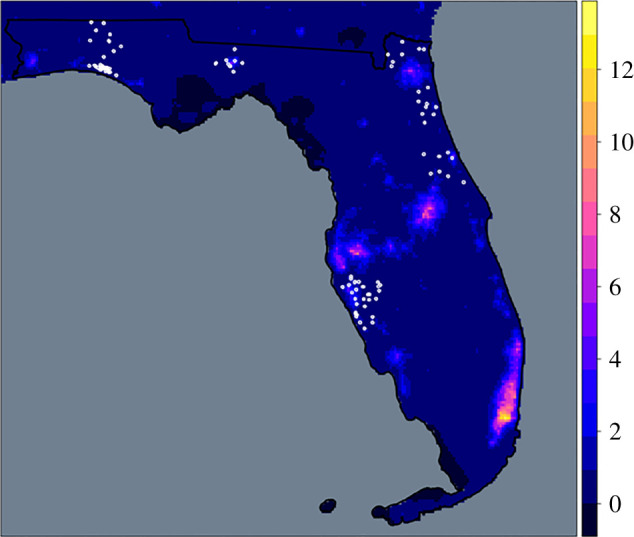

Given the current pervasiveness of ALAN, we asked whether light pollution can affect infectious disease dynamics in a part of the US where arboviruses are common and influential, both economically and socially [42]. Specifically, we investigated whether ALAN affected the risk of WNV exposure across several counties of Florida where emergence and spillover has occurred in the recent past [43]. We chose to focus on WNV because it is the most broadly distributed arbovirus and the most common causative agent of viral encephalitis worldwide [44,45]. Using data from the Florida Department of Health (FDOH) sentinel chicken WNV surveillance programme [21], we tested whether WNV exposure, as estimated by the number of sentinel chickens undergoing antibody seroconversion, would be related to ALAN exposure. We used mixed-effect models with and without spatial correlation structure to assess the effects of ALAN (in radiance, millicandela m−2) on WNV exposure for four recent years across five counties based on 6468 samples from individual chickens from 1126 surveillance events across 105 unique geographical coordinates, including many peri-urban regions (figure 1). These models also accounted for previously documented and other hypothesized predictors of WNV risk (i.e. variation in temperature, precipitation, soil moisture and several aspects of urbanization).

Figure 1.

ALAN intensity at sentinel chicken sites across Florida. Sentinel chicken sampling locations (white circles) throughout Florida overlaid on the artificial component of night sky brightness in radiance (μcd/m2) estimates from Falchi et al. [46]. (Online version in colour.)

We hypothesized that WNV exposure risk would have a nonlinear relationship with ALAN, being greatest in areas of moderate ALAN, and lowest in non- and intensely light-polluted areas. We made this specific and yet complex prediction because we expected vector density and/or host competence to be highest in areas with intermediate light pollution [32]. As above, house sparrows were more infectious under these ALAN conditions than natural light-dark conditions. Also, we found previously that some Culex mosquitoes were most abundant in areas of moderate ALAN during WNV transmission season, indicating there might be combined effects of flight-to-light behaviour from dark areas, but increased vector predation in intensely illuminated areas [42,47–49]. Active avoidance of ALAN by passerines, likely in part due to increased predation risk or negative physiological effects, could also decrease host density in brightly illuminated places, subsequently reducing opportunities for transmission [34,48,50–52].

2. Methods

(a). Sentinel data

Sentinel chicken data were shared by the Florida Department of Health offices in Leon, Manatee, Nassau, Sarasota, St. Johns, Volusia and Walton counties for the years 2015–2018. The data were provided as the monthly total number of sentinel chickens per site that tested positive for WNV antibodies. WNV case counts result from a weekly sampling of either 6 (89.5% of observations) or 4 (10.5% observations) sentinel chickens located at each site [43]. Once a chicken tested positive for WNV antibodies, it was removed from a coop and replaced with a WNV-naïve chicken, ensuring that all positives are new exposures. Coops housing sentinel chickens were occasionally moved small distances (typically less than 0.001 degrees or less than approximately 100 m, but as much as 11 km), resulting in small differences in coop locations across years. As such, we used the unique coordinates from each sentinel chicken sampling location to determine the anthropogenic components of night sky brightness in radiance (ALAN), weather variables (soil moisture, temperature, precipitation) and urbanization variables (human population density, anthropogenic impervious surface extent, human footprint index, see below) at the time and place of sampling of each chicken coop.

(b). Environmental data

Because multiple dimensions of the environment, including ALAN, vary along an urbanization gradient, understanding which aspects are responsible for elevated WNV risk is challenging. As such, we assembled geospatial data reflective of several dimensions of urbanization: percentage anthropogenic impervious surface from the 2011 National Landcover Database (30 m resolution [53]), human population density from the 2010 US Census (1 km resolution [28]), human footprint index data reflective of conditions in 2009 (1 km resolution [54]), plus ALAN estimates from the world atlas of artificial night sky brightness (30-arc seconds, i.e. approx. 1 km resolution [46]), which is an improved measure of NASA's VIIRS data using zenith sky brightness confirmed with handheld sky quality monitors [55]. This resource provides the anthropogenic component of night sky brightness in radiance (microcandela/m2, henceforth denoted as μcd m−2) and is regarded as the most relevant available option at the spatial scale of our study, particularly as zenith sky brightness is more highly correlated with ground-level ALAN exposure than VIIRs satellite data [56]. We temporally harmonized high-resolution monthly cumulative precipitation and monthly mean temperature data (0.8 km resolution) from the PRISM database [57] and monthly mean soil moisture estimates (3 km resolution) generated from NASA's Sentinel 1/SMAP platform [58] to match the month of sentinel chicken sampling. Additionally, to account for potential lags in conditions that could favour vector abundance, we also collected data for these variables from the month prior to sampling. Because greater than 94% of the positive detections of WNV occurred after May of each year, which is similar to other studies [59,60], we restricted our analyses to June–December. Additionally, because mean soil moisture estimates for the month of surveillance and the prior month were not available for all records, we restricted analyses to those records with complete environmental data, resulting in a final dataset of 6468 samples from individual chickens from 1126 surveillance events spanning 80 sites and 105 unique spatial locations.

(c). Data analysis

We modelled incidence of WNV seroprevalence using mixed-effect models with and without a spatially explicit exponential correlation structure with negative binomial error and implemented in the fitme function of the R package spaMM 2.7.5 [61] and the glmm.nb function of the R package lme4 1.1-21 [62]. We used a negative binomial error rather than a Poisson error in our models as many preliminary Poisson models did not converge. Models that did converge received less support from the data than identical models with negative binomial error (i.e. ΔAIC ≥ 30). Because of the high number of zeros in the response variable, we also checked models for zero-inflation using the testZeroInflation function in the R package DHARMa 0.2.4 [63] but found no evidence that a zero-inflated term was necessary.

Given the hierarchical and repeated sampling regime of sentinel chicken surveillance programs, we included nested random effects of sampling month within site within the county. For fixed effects, we built a model that included ALAN, the three variables reflective of urbanization (i.e. impervious surface extent, population density, human footprint) and monthly mean soil moisture, precipitation total and mean temperature, plus a year to account for inter-annual variation. All continuous variables were centred and scaled to facilitate direct comparisons of effects and, based on our hypothesis that WNV seroprevalence would peak at intermediate ALAN exposure levels, we also modelled the effect of ALAN as a second-order polynomial. Preliminary data exploration revealed a nonlinear relationship between WNV seroprevalence and monthly mean temperature, which was also best explained by a second-order polynomial.

From the fully parameterized model described above, we explored whether substituting monthly soil moisture, precipitation total and mean temperature values with the corresponding values from the previous month improved model performance using Akaike information criterion (AIC) values. We retained soil moisture and precipitation totals from the months in which chickens were sampled. However, subsequent analyses included the monthly mean temperature of the prior month because this time-lagged form of the temperature variable received stronger support than the monthly mean temperature of the month of sampling (ΔAIC > 90). We used AIC scores to gauge whether polynomial terms for ALAN and mean temperature of the previous month improved model performance over linear effects of each. We also used AIC scores to arbitrate between spatial and non-spatial models, to evaluate the support for using an offset to account for the number of chickens sampled per site per month, and to test whether there was any evidence for polynomial effects of predictor variables other than ALAN that reflected urbanization. We considered models with ΔAIC scores ≤ 2.0 as equally competitive and determined that a parameter had a strong effect on WNV seroprevalence patterns when its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) did not overlap zero. Finally, because different approaches to model selection can result in different results [64], we evaluated relative model support using two additional information criteria in the spaMM package: the conditional AIC (cAIC) [65], which is conditional on the realized values of the random effects, and the dispersion AIC (dAIC), which focuses on dispersion parameters [66].

Finally, we conducted two forms of model diagnostics. First, we checked for potential multicollinearity and redundancy among predictor variables with variance inflation factor (VIF) and considered VIF > 10 as potentially problematic [67]. The mean temperature of the previous month, and its quadratic term, were the only parameters with suspect VIF scores. However, centring this variable at its mean resulted in VIF < 2.0 for each variable. Second, we assessed model performance with qqplots and residual versus expected value plots using the simulateResiduals function in the R package DHARMa 0.2.4 [63].

3. Results and discussion

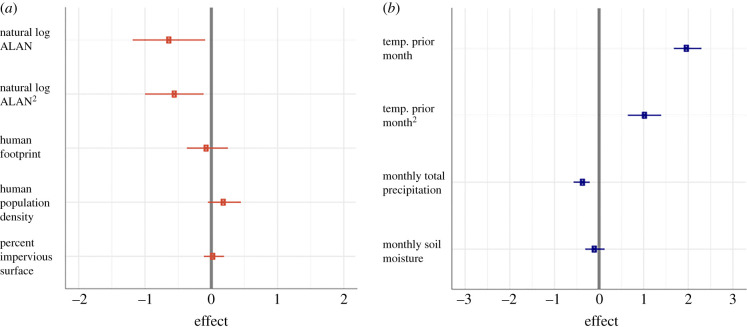

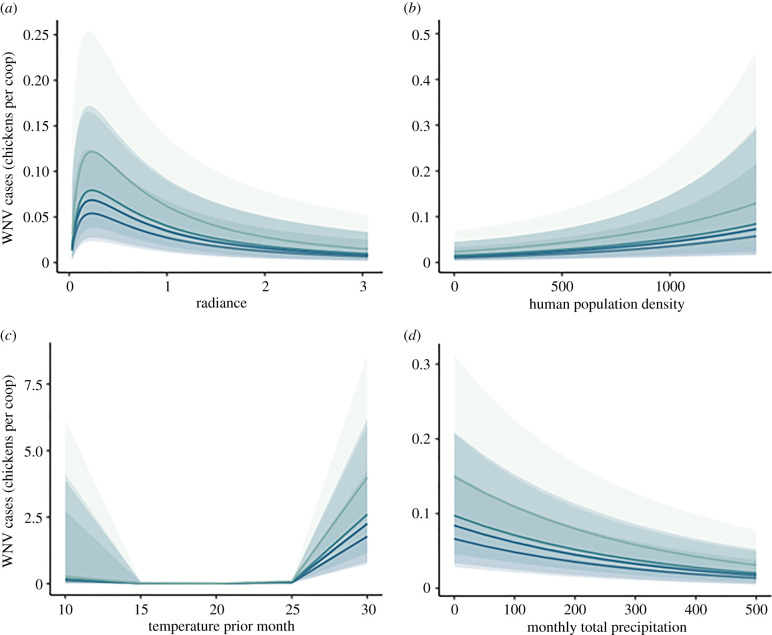

ALAN was a strong but nonlinear predictor of WNV exposure risk in Florida (figure 2a). Models with and without spatial correlation structure (or an offset to account for variation in the number of chicken samples per site; see electronic supplementary material, text) were equally competitive (table 1) and included qualitatively similar parameter estimates for ALAN. Alternative model selection criteria also confirmed model rankings via AIC and relative competitiveness. Specifically, we found that WNV risk rises rapidly from dark conditions and peaks at low anthropogenic radiance intensities (i.e. less than 0.5), but then declines with higher ALAN exposure (figure 3a). This peak was slightly lower than expected but overall consistent with our hypothesis.

Figure 2.

Effect sizes of (a) ALAN and urbanization and (b) temperature and weather variables on West Nile virus risk. Standardized effect sizes (square symbols) and 95% CI (lines) from top ranked model in table 1. Natural log of ALAN and ALAN2 in radiance (μcd m−2) had the largest effects on WNV risk compared to urbanization parameters, whereas mean temperature and mean temperature2 of the prior month had the largest effect sizes compared to precipitation and soil moisture variables. Variables are natural log transformed to account for the extreme values in the distribution of data. (Online version in colour.)

Table 1.

WNV exposure models with spatial, non-spatial and offset options near-equivalent. Rankings among models with and without spatial correlation structure and offsets to account for variation in number of sentinel chickens surveyed. All models contained the following fixed effects: second-order polynomial terms for mean temperature of the previous month and natural log of ALAN, plus human footprint index, human population density, percentage impervious surface, monthly total precipitation, monthly soil moisture and year.

| model | logLik | AIC | ΔAIC | cAIC | dAIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| spatial | −727.492 | 1492.981 | 0 | 1460.878 | 1466.981 |

| non-spatial | −729.772 | 1493.544 | 0.563 | 1467.355 | 1467.544 |

| non-spatial with offset | −729.939 | 1493.878 | 0.897 | 1471.652 | 1467.878 |

| spatial with offset | −729.272 | 1496.545 | 3.564 | 1470.341 | 1470.545 |

Figure 3.

Inter-annual effects of (a) ALAN, (b) human population density per km2, (c) mean temperature of the previous month in degrees Celsius and (d) monthly total precipitation (mm) on incidence of WNV seroprevalence. Marginal effects of each plotted by year with 95% CI band. Darkest colour denotes earliest year (i.e. 2015) with lighter colours denoting subsequent years. Effects of ALAN (anthropogenic component of night sky brightness in radiance (μcd m−2), human population density, temperature and precipitation on WNV exposure were consistent across 5 years. (Online version in colour.)

Besides the consistent influence of ALAN, all models provided strong evidence for a lag effect of temperature whereby high temperature (greater than 25°C) during the previous month strongly and positively influenced WNV seroprevalence (figures 2b and 3c). By contrast, increases in monthly cumulative precipitation were negatively related to WNV seroprevalence (figure 3d), which is also consistent with prior work [68]. By contrast with previous reports [17,18], we found no influence of two metrics of urbanization, human footprint index or percentage anthropogenic impervious surface, on WNV seroprevalence in chickens. We found mixed support for an influence of human population density on WNV seroprevalence where two of the four models suggested there was a positive relationship (figure 3b; electronic supplementary material, text). Additionally, there was also some evidence for inter-annual variation in WNV prevalence; nonetheless, we found consistent polynomial ALAN effects on WNV risk across several years (figure 3a).

To ensure that the relationship between WNV seroprevalence and ALAN did not reflect nonlinear effects of other variables characteristic of urbanization, we also tested for polynomial effects of human population density, human footprint index and percentage anthropogenic impervious surface on WNV exposure risk. No polynomial terms for these variables were supported, and the model with only linear terms for all predictors (including weather variables and ALAN) received the least support (table 2). Alternative model selection criteria (cAIC and dAIC) led to the same conclusions. Finally, based on the polynomial effects of both temperature of the previous month and the natural log of ALAN, we conducted a post hoc analysis with a model containing the interaction between the two, but the interaction decreased model performance (ΔAIC = 7.564; table 2).

Table 2.

Polynomial ALAN and polynomial average temperature of the previous month were the best predictors of WNV exposure risk. Rankings among models where anthropogenic predictors and mean temperature of the previous month were modelled with linear or polynomial effects. All models contained the following fixed effects: mean temperature of the previous month (temp), natural log of ALAN, human footprint index (hum foot), human population density (pop den), percentage impervious surface (imp sur), monthly total precipitation, monthly soil moisture and year. For each model, all predictors remained in each iteration of the model and we denote which parameters were included as polynomial effects with ‘poly’. ‘All linear’ reflects a model with no polynomial terms. ‘poly ALAN × poly temp’ reflects the post hoc analysis of adding an interaction to the top ranked model in table 1. All models were spatially explicit and did not contain an offset (i.e. such as top ranked model from table 1).

| model | logLik | AIC | ΔAIC | cAIC | dAIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| poly ALAN, poly temp | −727.492 | 1492.981 | 0.000 | 1460.880 | 1466.98 |

| poly temp | −730.790 | 1497.580 | 4.596 | 1463.940 | 1473.58 |

| poly pop den; poly temp | −730.753 | 1499.506 | 6.522 | 1465.320 | 1473.51 |

| poly imp sur; poly temp | −730.754 | 1499.508 | 6.524 | 1465.544 | 1473.51 |

| poly hum foot; poly temp | −730.781 | 1499.561 | 6.577 | 1465.450 | 1473.57 |

| poly ALAN | −736.806 | 1509.611 | 16.627 | 1478.040 | 1485.61 |

| all linear | −740.050 | 1514.100 | 21.116 | 1481.260 | 1492.11 |

| poly ALAN × poly temp | −727.272 | 1500.545 | 7.564 | 1468.182 | 1466.54 |

The use of radiance in units of microcandelas per m2 in this study is admittedly hard to translate into values of light pollution measurable at fine spatial scales. Radiance values in our dataset appear relatively low, but electronic supplementary material, figure S1 shows most ALAN values at coop sites range from 0 to 2.5, so the peak in WNV cases around less than 0.5 can be interpreted as low-intensity light pollution. Previous experimental studies measured ALAN in units of lux using handheld light metres in enclosed facilities, which served as the foundation for our hypotheses [50]. Whereas others have emphasized that data from the new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness that we chose to use here are highly related to light pollution levels at ground level [55,69], a critical component to future work involving ALAN will be understanding how remotely sensed values translate to other common metrics for quantifying light exposure, such as lux [70]. Thus, although our models suggest that WNV risk increases from the darkest sites in our dataset to peak in areas exposed to some degree of light pollution, we are limited by the current availability of data, namely, that our ALAN measure captures only the artificial component of night sky brightness. Notwithstanding the importance of developing methods to better describe light pollution at finer spatial scales, below we discuss how light pollution might exacerbate the risk of WNV and other EIDs, and why WNV risk exhibited a nonlinear relationship with ALAN.

(a). Why does artificial light at night affect West Nile virus exposure?

The relationship between ALAN and WNV exposure risk we described was not altogether surprising. As highlighted earlier, ALAN can extend the infectious period of one avian host; perhaps similar effects occur in other host species [42]. Other studies strongly suggest that ALAN could also increase the local density and feeding period of crepuscular vectors, which might significantly alter opportunities for transmission [71]. Such effects are particularly likely because many vectors exhibit flight-to-light behaviour, which could further concentrate risk spatio-temporally [37].

(b). Nonlinearity of artificial light at night effects on West Nile virus exposure risk

Our results suggest that although WNV exposure risk initially increased with ALAN, it subsequently declined towards the most intensely lit sites in our study. Previously, we found that hosts exposed to broad-spectrum ALAN incurred greater mortality risk to WNV, which may create a disease ‘sink’ for some avian hosts in highly light-polluted areas [50]. As above, surveys of Culex mosquitoes in the Tampa Bay region also suggest that vectors are more abundant in moderately light-polluted areas than non- and highly light-polluted areas during the WNV transmission season [42]. Hosts and vectors are probably both at higher risk of predation under a full moon or street lights or other sources of ALAN, which may contribute to lower host and vector densities in intensely light-polluted areas [48,72]. Similarly, individual birds avoid light exposure at night, which would further decrease host density in intensely light-polluted areas [34]. Many characteristics of highly light-polluted areas (e.g. fragmented habitat) support fewer hosts and fewer vector breeding sources and may be subject to extensive vector control efforts [73–75]. Altogether, the recruitment of vectors to light-polluted areas, combined with reduced viral resistance, predator avoidance behaviour, and/or host or vector mortality effects could all contribute to the observed nonlinear relationship between ALAN intensity and WNV exposure risk. To better understand the mechanisms underlying the nonlinear relationship between WNV exposure and ALAN, we advocate for future research on the light intensity-dependent effects of ALAN on vector survival, vector bite rate and host susceptibility [71].

(c). Weather, precipitation and West Nile virus

In addition to ALAN, an average temperature of the prior month predicted WNV exposure in parts of Florida. It is unsurprising that this climate component was important in our models, as many aspects of WNV transmission are temperature dependent (e.g. vector development, survival and competence) [76]. Indeed, most vectors of WNV thrive when temperatures increase over summer months, as high temperatures accelerate vector growth rates and extrinsic incubation periods (i.e. the time required to develop a transmissible virus in salivary glands) [77]. Periods of heavy rainfall and the availability of water sources for breeding can also sustain large populations of Culex nigripalpus, a moderately competent WNV vector in south Florida [78,79]. Relatedly, irrigation in the Western United States has sustained populations of WNV vectors during dry periods, creating suburban hotspots [80]. Although water sources are required for mosquito breeding, drought is a significant predictor of high WNV infection rates in Culex pipiens and restuans [81]. Drought can indirectly increase vector abundance by decreasing mosquito predator density during drought years; however, these effects are typically time-lagged [82,83]. Alternatively, contradicting data indicate that higher WNV incidence may reflect changes in host competence rather than vector success [68]. While drought could be considered in future studies, we argue that the inclusion of rainfall data here enhanced our ability to control for natural factors at a higher resolution when asking how other variables affect WNV exposure risk.

(d). Urbanization and zoonotic exposure risk

Urbanization has long been viewed as a driver of WNV prevalence [18], but here, multiple metrics of urbanization had no to little explanatory power for WNV risk. Other studies have concluded that urban land use and human population density were important predictors of inter-annual WNV prevalence over large geographic regions [22,84,85]. These environmental features are hypothesized to drive WNV incidence due to decreased host diversity in urban areas, altered vector ecology (e.g. small water sources ideal for mosquito breeding) and/or increased host susceptibility to infection [86,87]. However, besides mixed support for a positive influence of human population density, we found minimal effects of urbanization on risk. One potential reason we did not detect relationships with urbanization might be due to a lack of data from the most urbanized areas of Florida. However, our study did include locations where anthropogenic surface was 67% and the human footprint index was 46.28 on a scale of 0–50, so we were able to capture diverse intensities of human inhabitation [54]. It is also possible that our urbanization metrics are distinct from the ones used in previous studies, as sentinel chicken sites typically are not located in city centres (electronic supplementary material, text). Further exploration of how ALAN interacts with other aspects of urbanization across the landscape to influence WNV risk will be valuable.

(e). Conclusions and implications

Our study suggests that light pollution might affect arbovirus infection risk in Florida and perhaps elsewhere. Investigating how host and vector responses to ALAN vary with the intensity level of light will be required to fully understand patterns in WNV exposure risk. The consideration of wild bird or vector data in the future would provide a more comprehensive description of how light at night might be affecting WNV outbreaks, whether it be Culex spp. derived or reservoir driven, and provide information regarding effective intervention strategies. Although additional studies are needed to assess the commonness of relationships between ALAN and WNV risk in other areas, mitigation opportunities exist that could ameliorate the negative consequences of ALAN on wildlife and humans [29]. Furthermore, we emphasize the need to investigate effects of ALAN on other passerine reservoirs of WNV, as songbirds, rather than sentinel chickens, drive transmission [88]. In particular, we should consider important peri-urban and rural reservoirs such as northern cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis) and American robins (Turdus migratorius) as they dominate avian communities in areas with low-intensity ALAN and are quite competent for WNV [35].

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrea Morrison, Dana Giandomenico and county offices at the Florida Department of Health for sharing their sentinel chicken surveillance data with us.

Contributor Information

Meredith E. Kernbach, Email: kernbach@mail.usf.edu.

Lynn B. Martin, Email: cdfranci@calpoly.edu.

Clinton D. Francis, Email: lbmartin@usf.edu.

Data accessibility

Data are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.msbcc2fxd [89].

Authors' contributions

M.E.K. solicited data, assisted in data cleaning and wrote manuscript; L.B.M. solicited data, assisted in data cleaning and revised manuscript; T.R.U. solicited data and revised manuscript; R.J.H. assisted in data analyses and revised manuscript; R.H.Y.J. revised manuscript; C.D.F. solicited data, assisted in data cleaning, performed analyses and revised manuscript.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by Division of Integrative Organismal Systems (NSF-IOS 1257773) and USF Internal to L.B.M.; Directorate for Biological Sciences (NSF-CNH 1414171), NASA Ecological Forecasting (NNX17AG36G) and National Park Service (NPS P17AC01178) to C.D.F.

References

- 1.Morens DM, Folkers GK, Fauci AS. 2004. The challenge of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Nature 430, 242-249. ( 10.1038/nature02759) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Binder S, Levitt AM, Sacks JJ, Hughes JM. 1999. Emerging infectious diseases: public health issues for the 21st century. Science 284, 1311-1313. ( 10.1126/science.284.5418.1311) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, Storeygard A, Balk D, Gittleman JL, Daszak P. 2008. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451, 990-993. ( 10.1038/nature06536) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolhouse MEJ, Gowtage-Sequeria S. 2005. Host range and emerging and reemerging pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 1842-1847. ( 10.3201/eid1112.050997) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Estrada-Peña A, Ostfeld RS, Peterson AT, Poulin R, de la Fuente J. 2014. Effects of environmental change on zoonotic disease risk: an ecological primer. Trends Parasitol. 30, 205-214. ( 10.1016/j.pt.2014.02.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dominoni DM, et al. 2020. Why conservation biology can benefit from sensory ecology. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 502-511. ( 10.1038/s41559-020-1135-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray MH, Sánchez CA, Becker DJ, Byers KA, Worsley-Tonks KEL, Craft ME. 2019. City sicker? A meta-analysis of wildlife health and urbanization. Front. Ecol. Environ. 17, 575-583. ( 10.1002/fee.2126) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis SL, Maslin MA. 2015. Defining the Anthropocene. Nature 519, 171-180. ( 10.1038/nature14258) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMahon BJ, Morand S, Gray JS. 2018. Ecosystem change and zoonoses in the Anthropocene. Zoonoses Public Health 65, 755-765. ( 10.1111/zph.12489) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilpatrick AM, Randolph SE. 2012. Drivers, dynamics, and control of emerging vector-borne zoonotic diseases. Lancet 380, 1946-1955. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61151-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marfin AA, et al. 2001. Widespread West Nile virus activity, eastern United States, 2000. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7, 730-735. ( 10.3201/eid0704.017423) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turell MJ, O'Guinn ML, Dohm DJ, Jones JW. 2001. Vector competence of North American mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) for West Nile virus. J. Med. Entomol. 38, 130-134. ( 10.1603/0022-2585-38.2.130) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes EB, Komar N, Nasci RS, Montgomery SP, O'Leary DR, Campbell GL. 2005. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 1167-1173. ( 10.3201/eid1108.050289a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marm Kilpatrick A, Wheeler SS. 2019. Impact of West Nile virus on bird populations: limited lasting effects, evidence for recovery, and gaps in our understanding of impacts on ecosystems. J. Med. Entomol. 56, 1491-1497. ( 10.1093/jme/tjz149) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson BJ, Munafo K, Shappell L, Tsipoura N, Robson M, Ehrenfeld J, Sukhdeo MVK. 2012. The roles of mosquito and bird communities on the prevalence of West Nile virus in urban wetland and residential habitats. Urban Ecosyst. 15, 513-531. ( 10.1007/s11252-012-0248-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H, Weng Q, Gaines D. 2011. Geographic incidence of human West Nile virus in northern Virginia, USA, in relation to incidence in birds and variations in urban environment. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 4235-4241. ( 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.07.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilpatrick AM. 2011. Globalization, land use, and the invasion of West Nile virus. Science 334, 323-327. ( 10.1126/science.1201010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradley CA, Gibbs SEJ, Altizer S. 2008. Urban land use predicts west Nile virus exposure in songbirds. Ecol. Appl. 18, 1083-1092. ( 10.1890/07-0822.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loss SR, Hamer GL., Walker ED, Ruiz MO, Goldberg TL, Kitron UD, Brawn JD. 2009. Avian host community structure and prevalence of West Nile virus in Chicago, Illinois. Oecologia 159, 415-424. ( 10.1007/s00442-008-1224-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Day JF, Tabachnick WJ, Smartt CT. 2015. Factors that influence the transmission of West Nile Virus in Florida. J. Med. Entomol. 52, 743-754. ( 10.1093/jme/tjv076) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day JF, Lewis AL. 1991. An integrated approach to arboviral surveillance in Indian River County, Florida. J. Florida Mosq. Control Assoc. 62, 46-52. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gómez A, et al. 2008. Land use and West Nile virus seroprevalence in wild mammals. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, 962-965. ( 10.3201/eid1406.070352) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LoGiudice K, Ostfeld RS, Schmidt KA, Keesing F. 2003. The ecology of infectious disease: effects of host diversity and community composition on lyme disease risk. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 567-571. ( 10.1073/pnas.0233733100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhondt AA, et al. 2005. Dynamics of a novel pathogen in an avian host: mycoplasmal conjunctivitis in house finches. Acta Trop. 94, 77-93. ( 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.01.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weaver SC. 2013. Urbanization and geographic expansion of zoonotic arboviral diseases: mechanisms and potential strategies for prevention. Trends Microbiol. 21, 360-363. ( 10.1016/j.tim.2013.03.003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyba CCM, et al. 2017. Artificially lit surface of Earth at night increasing in radiance and extent. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701528. ( 10.1126/sciadv.1701528) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horton KG, Nilsson C, Van Doren BM, La Sorte FA, Dokter AM, Farnsworth A. 2019. Bright lights in the big cities: migratory birds' exposure to artificial light. Front. Ecol. Environ. 17, 209-214. ( 10.1002/fee.2029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Census Bureau. 2010. Population, housing units, area, and density: 2010—United States and Puerto Rico. See www.census.gov/library/publications/2012/dec/cph-2.html.

- 29.Navara KJ, Nelson RJ. 2007. The dark side of light at night: physiological, epidemiological, and ecological consequences. J. Pineal. Res. 43, 215-224. ( 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2007.00473.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cermakian N, Lange T, Golombek D, Sarkar D, Nakao A, Shibata S, Mazzoccoli G. 2013. Crosstalk between the circadian clock circuitry and the immune system. Chronobiol. Int. 30, 870-888. ( 10.3109/07420528.2013.782315) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Becker DJ, Singh D, Pan Q, Montoure JD, Talbott KM, Wanamaker SM, Ketterson ED. 2020. Artificial light at night amplifies seasonal relapse of haemosporidian parasites in a widespread songbird. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20191051. ( 10.1098/rspb.2020.1831) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kernbach ME, et al. 2019. Light pollution increases West Nile virus competence of a ubiquitous passerine reservoir species. Proc. R. Soc. B 286, 20191051. ( 10.1098/rspb.2019.1051) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kyba CCM, Mohar A, Posch T. 2017. How bright is moonlight? Astron. Geophys. 58, 1.31-1.32. ( 10.1093/astrogeo/atx025) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dominoni DM, Carmona-Wagner EO, Hofmann M, Kranstauber B, Partecke J. 2014. Individual-based measurements of light intensity provide new insights into the effects of artificial light at night on daily rhythms of urban-dwelling songbirds. J. Anim. Ecol. 83, 681-692. ( 10.1111/1365-2656.12150) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans BS, Ryder TB, Reitsma R, Hurlbert AH, Marra PP. 2015. Characterizing avian survival along a rural-to-urban land use gradient. Ecology 96, 1631-1640. ( 10.1890/14-0171.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donners M, van Grunsven RHA, Groenendijk D, van Langevelde F, Bikker JW, Longcore T, Veenendaal E. 2018. Colors of attraction: modeling insect flight to light behavior. J. Exp. Zool. Part A Ecol. Integr. Physiol. 329, 434-440. ( 10.1002/jez.2188) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barghini A, de Medeiros BAS. 2010. Artificial lighting as a vector attractant and cause of disease diffusion. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 1503-1506. ( 10.1289/ehp.1002115) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamer GL, et al. 2008. Rapid amplification of West Nile Virus: the role of hatch-year birds. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 8, 57-68. ( 10.1089/vbz.2007.0123) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marra PP, et al. 2004. West Nile virus and wildlife. Bioscience 54, 393-402. ( 10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054[0393:WNVAW]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sardelis MR, Turell MJ, Dohm DJ, O'Guinn ML. 2001. Vector competence of selected North American Culex and Coquillettidia mosquitoes for West Nile virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7, 1018-1022. ( 10.3201/eid0706.010617) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gangoso L, et al. 2020. Determinants of the current and future distribution of the West Nile virus mosquito vector Culex pipiens in Spain. Environ. Res. 188, 109837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kernbach ME, Hall RJ, Burkett-Cadena ND, Unnasch TR, Martin LB. 2018. Dim light at night: physiological effects and ecological consequences for infectious disease. Integr. Comp. Biol. 58, 995-1007. ( 10.1093/icb/icy080) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Florida Department of Health. 2020. Mosquito-Borne Disease Surveillance. See http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/mosquito-borne-diseases/surveillance.html.

- 44.Davies TW, Smyth T. 2018. Why artificial light at night should be a focus for global change research in the 21st century. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 872-882. ( 10.1111/gcb.13927) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chancey C, Grinev A, Volkova E, Rios M. 2015. The global ecology and epidemiology of West Nile virus. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 1-20. ( 10.1155/2015/376230) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Falchi F, Cinzano P, Duriscoe D, Kyba CCM, Elvidge CD, Baugh K, Portnov BA, Rybnikova NA, Furgoni R. 2016. The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600377. ( 10.1126/sciadv.1600377) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisenbeis G, Hassel F. 2011. Attraction of nocturnal insects to street lights lighting systems, with considerations of LEDs. Natur und Landschaft 86, 298-306. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewanzik D, Voigt CC. 2014. Artificial light puts ecosystem services of frugivorous bats at risk. J. Appl. Ecol. 51, 388-394. ( 10.1111/1365-2664.12206) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krebs BL, Anderson TK.Goldberg TL, Hamer GL, Kitron UD, Newman CM, Ruiz MO, Walker ED, Brawn JD. 2014. Host group formation decreases exposure to vector-borne disease: a field experiment in a ‘hotspot’ of West Nile virus transmission. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20141586. ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.1586) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kernbach ME, Cassone VM, Unnasch TR, Martin LB. 2020. Broad-spectrum light pollution suppresses melatonin and increases West Nile virus-induced mortality in House Sparrows (Passer domesticus). Condor 122, duaa018. ( 10.1093/condor/duaa018) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daly M, Behrends PR, Wilson MI, Jacobs LF. 1992. Behavioural modulation of predation risk: moonlight avoidance and crepuscular compensation in a nocturnal desert rodent, Dipodomys merriami. Anim. Behav. 44, 1-9. ( 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80748-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fallows C, Fallows M, Hammerschlag N. 2016. Effects of lunar phase on predator-prey interactions between white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) and Cape fur seals (Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus). Environ. Biol. Fishes 99, 805-812. ( 10.1007/s10641-016-0515-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Homer C, et al. 2015. Completion of the 2011 national land cover database for the conterminous United States—representing a decade of land cover change information. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sensing 81, 345-354. ( 10.1016/S0099-1112(15)30100-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Venter O, et al. 2016. Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nat. Commun. 7, 12558. ( 10.1038/ncomms12558) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhong C, Franklin M, Wiemels J, McKean-Cowdin R, Chung NT, Benbow J, Wang SS, Lacey JV, Longcore T. 2020. Outdoor artificial light at night and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma among women in the California Teachers Study cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. 69, 101811. ( 10.1016/j.canep.2020.101811) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simons AL, Yin X, Longcore T. 2020. High correlation but high scale-dependent variance between satellite measured night lights and terrestrial exposure. Environ. Res. Commun. 2, 021006. ( 10.1088/2515-7620/ab7501) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schneider DP, Deser C, Fasullo J, Trenberth KE. 2013. Climate data guide spurs discovery and understanding. Eos (Washington DC) 94, 121-122. ( 10.1002/2013EO130001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Das N, et al. 2017. SMAP/Sentinel-1 L2 Radiometer/Radar 30-Second Scene 3 km EASE-Grid Soil Moisture, Version 1 (Boulder, Colorado USA) ( 10.5067/9UWR1WTHW1WN) [DOI]

- 59.Bolling BG, Barker CM, Moore CG, Pape WJ, Eisen L. 2009. Seasonal patterns for entomological measures of risk for exposure to culex vectors and West Nile virus in relation to human disease cases in Northeastern Colorado. J. Med. Entomol. 46, 1519-1531. ( 10.1603/033.046.0641) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Apperson CS, et al. 2004. Host feeding patterns of established and potential mosquito vectors of West Nile virus in the Eastern United States. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 4, 71-82. ( 10.1089/153036604773083013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rousset F, Ferdy JB. 2014. Testing environmental and genetic effects in the presence of spatial autocorrelation. Ecography (Cop) 37, 781-790. ( 10.1111/ecog.00566) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker BM, Walker SC. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1-48. ( 10.18637/jss.v067.i01) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hartig F. 2020. DHARMa: residual diagnostics for hierarchical regression models. See http://florianhartig.github.io/DHARMa/. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Posada D, Buckley TR. 2004. Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: advantages of akaike information criterion and Bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Syst. Biol. 53, 793-808. ( 10.1080/10635150490522304) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vaida F, Blanchard S. 2005. Conditional Akaike information for mixed-effects models. Biometrika 92, 351-370. ( 10.1093/biomet/92.2.351) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ha ID, Lee Y, MacKenzie G. 2007. Model selection for multi-component frailty models. Stat. Med. 26, 4790-4807. ( 10.1002/sim.2879) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dormann C, et al. 2007. Methods to account for spatial autocorrelation in the analysis of species distributional data: a review. Ecography (Cop) 30, 609-628. ( 10.1111/j.2007.0906-7590.05171.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paull SH, Horton DE., Ashfaq M, Rastogi D, Kramer LD, Diffenbaugh NS, Kilpatrick AM. 2017. Drought and immunity determine the intensity of West Nile virus epidemics and climate change impacts. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20162078. ( 10.1098/rspb.2016.2078) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bustamante-Calabria M, et al. 2020. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on urban light emissions: ground and satellite comparison. Remote Sensing 13, 258. ( 10.3390/rs13020258) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zamorano J, García C, Tapia C, Sánchez de Miguel A, Pascual S, Gallego J. 2017. STARS4ALL night sky brightness photometer. Int. J. Sustain Light 18, 49-54. ( 10.26607/ijsl.v18i0.21) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wonham MJ, De-Camino-Beck T, Lewis MA. 2004. An epidemiological model for West Nile virus: invasion analysis and control applications. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, 501-507. ( 10.1098/rspb.2003.2608) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Minnaar C, Boyles JG, Minnaar IA, Sole CL, Mckechnie AE. 2015. Stacking the odds: light pollution may shift the balance in an ancient predator-prey arms race. J. Appl. Ecol. 52, 522-531. ( 10.1111/1365-2664.12381) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wright AN, Gompper ME. 2005. Altered parasite assemblages in raccoons in response to manipulated resource availability. Oecologia 144, 148-156. ( 10.1007/s00442-005-0018-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Norris DE. 2004. Mosquito-borne diseases as a consequence of land use change. Ecohealth 1, 19-24 ( 10.1007/s10393-004-0008-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Luz PM, Vanni T, Medlock J, Paltiel AD, Galvani AP. 2011. Dengue vector control strategies in an urban setting: an economic modelling assessment. The Lancet 377, 1673-1680. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60246-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paz S. 2015. Climate change impacts on West Nile virus transmission in a global context. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370, 20130561. ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0561) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Paz S, Semenza JC. 2013. Environmental drivers of West Nile fever epidemiology in Europe and Western Asia--a review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10, 3543-3562. ( 10.3390/ijerph10083543) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shaman J, Day JF, Stieglitz M. 2003. St. Louis encephalitis virus in wild birds during the 1990 South Florida Epidemic: the importance of drought, wetting conditions, and the emergence of Culex nigripalpus (Diptera: Culicidae) to Arboviral Amplification and Transmission. J. Med. Entomol. 40, 547-554. ( 10.1603/0022-2585-40.4.547) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Turell MJ, Dohm DJ, Sardelis MR, O'guinn ML, Andreadis TG, Blow JA. 2005. An update on the potential of North American mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to transmit West Nile virus. J. Med. Entomol. 42, 57-62. ( 10.1093/jmedent/42.1.57) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.DeGroote JP, Sugumaran R. 2012. National and regional associations between human West Nile virus incidence and demographic, landscape, and land use conditions in the coterminous United States. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 12, 657-665. ( 10.1089/vbz.2011.0786) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Johnson BJ, Sukhdeo MVK. 2013. Drought-induced amplification of local and regional West Nile Virus infection rates in New Jersey. J. Med. Entomol. 50, 195-204. ( 10.1603/ME12035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lebl K, Brugger K, Rubel F. 2013. Predicting Culex pipiens/restuans population dynamics by interval lagged weather data. Parasit. Vectors 6, 1-11. ( 10.1186/1756-3305-6-129) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chase JM, Knight TM. 2003. Drought-induced mosquito outbreaks in wetlands. Ecol. Lett. 6, 1017-1024. ( 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00533.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gibbs DSEJ, Wimberly MC, Madden M, Masour J, Yabsley MJ, Stallknecht DE. 2006. Factors affecting the geographic distribution of West Nile virus in Georgia, USA: 2002–2004. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 6, 73-82. ( 10.1089/vbz.2006.6.73) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Begon M, Bennett M, Bowers RG, French NP, Hazel SM, Turner J. 2002. A clarification of transmission terms in host-microparasite models: numbers, densities and areas. Epidemiol. Infect. 129, 147-153. ( 10.1017/S0950268802007148) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ezenwa VO, Godsey MS, King RJ, Guptill SC. 2006. Avian diversity and West Nile virus: testing associations between biodiversity and infectious disease risk. Proc. Biol. Sci. 273, 109-117. ( 10.1098/rspb.2005.3284) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bradley CA, Altizer S. 2007. Urbanization and the ecology of wildlife diseases. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 95-102. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2006.11.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Komar N, Langevin S, Hinten S, Nemeth N, Edwards E, Hettler D, Davis B, Bowen R, Bunning M. 2003. Experimental infection of North American birds with the New York 1999 strain of West Nile virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9, 311-322. ( 10.3201/eid0903.020628) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kernbach ME, Martin LB, Unnasch TR, Hall RJ, Jiang RHY, Francis CD. 2021. Data from: Light pollution affects West Nile virus exposure risk across Florida. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.msbcc2fxd) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Kernbach ME, Martin LB, Unnasch TR, Hall RJ, Jiang RHY, Francis CD. 2021. Data from: Light pollution affects West Nile virus exposure risk across Florida. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.msbcc2fxd) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.msbcc2fxd [89].