Abstract

Novel behaviours can spur evolutionary change and sometimes even precede morphological innovation, but the evolutionary and developmental contexts for their origins can be elusive. One proposed mechanism to generate behavioural innovation is a shift in the developmental timing of gene-expression patterns underlying an ancestral behaviour, or molecular heterochrony. Alternatively, novel suites of gene expression, which could provide new contexts for signalling pathways with conserved behavioural functions, could promote novel behavioural variation. To determine the relative contributions of these alternatives to behavioural innovation, I used a species of spadefoot toad, Spea bombifrons. Based on environmental cues, Spea larvae develop as either of two morphs: ‘omnivores' that, like their ancestors, feed on detritus, or ‘carnivores' that are predaceous and cannibalistic. Because all anuran larvae undergo a natural transition to obligate carnivory during metamorphosis, it has been proposed that the novel, predaceous behaviour in Spea larvae represents the accelerated activation of gene networks influencing post-metamorphic behaviours. Based on comparisons of brain transcriptional profiles, my results reject widespread heterochrony as a mechanism promoting the expression of predaceous larval behaviour. They instead suggest that the evolution of this trait relied on novel patterns of gene expression that include components of pathways with conserved behavioural functions.

Keywords: carnivory, transcriptomics, plasticity, polyphenism, cannibalism

1. Introduction

Novel behaviours can precede and even shape morphological evolution [1,2]. Although several theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain the evolution of novel traits [3–6], relatively few empirical studies attempt to use such frameworks to explain the evolution of novel behaviours [7–9]. Therefore, an outstanding question is where the raw material for evolutionarily novel behaviours comes from.

A major mechanism proposed as a catalyst for behavioural innovation is heterochrony, whereby novel traits arise from shifts in the ontogenetic (i.e. developmental) timing of the expression of ancestral traits [4,10]. The ‘molecular heterochrony hypothesis' specifically predicts that gene expression associated with an ancestral behaviour will also be associated with a derived behaviour, albeit during a different stage of development [11]. For example, sibling care, a behavioural innovation and hallmark trait of eusocial systems, may have evolved from the precocious display of maternal care in worker females towards siblings instead of their own offspring [12]. Indeed, a suite of common genes have been implicated in both sibling and maternal care behaviour in Polistes wasps [13].

However, other studies have suggested the importance of a genetic ‘toolkit' in the evolution of sibling care [14]. This alternative hypothesis posits that certain genes and pathways have highly conserved roles in behaviour across diverse taxa, and that novel, complex behaviours can be assembled anew from simpler, pre-existing behavioural modules [8]. Supporting this scenario, genetic pathways related to feeding and reproduction in Drosophila melanogaster are instrumental in the expression of more complex honeybee social behaviours [14]. Furthermore, the paucity of analogous, molecular studies in other novel behaviours or in non-insect taxa leaves it unclear which of these two hypotheses enjoys more support across animals. Investigation of the evolutionary paths to behavioural innovation over a broader swath of organisms exhibiting different behavioural phenotypes would shed light on the generality of these proposed mechanisms.

Comparing species or populations, one expressing an ancestral behaviour and the other a derived behaviour, is a common approach for revealing the evolutionary changes necessary for behavioural modification [15]. However, the relative importance of heterochronic expression as the basis of behavioural innovation is hard to test in many systems because even closely related species or populations that retain ancestral behaviours may show a unique profile of gene expression—unrelated to behavioural differences—as a consequence of their independent evolution. Examination of environmentally induced ecomorphs within a species—one exhibiting the ancestral behaviour and one exhibiting a novel behaviour—can be useful for identifying expression patterns specific to the ontogenetic emergence of the novel behaviour. Spadefoot toads present a system in which this is possible: larvae (tadpoles) of the genus Spea have the ability to develop as such ecomorphs based on environment cues experienced early in development [16]. The ‘omnivore' morphs forage on the bottom of ponds for decaying plants and animals, a behaviour that likely represents the ancestral state for Spea larvae [17,18]. Alternatively, ‘carnivore' morphs, which exhibit highly derived morphologies and behaviours, are induced by and specialized for consuming shrimp and other tadpoles. This morph spends more time in the water column actively pursuing prey than opportunistically consuming decaying animals. Although the ecological drivers of this behavioural innovation are well-studied [19,20], its evolutionary origins and proximate basis are virtually unknown.

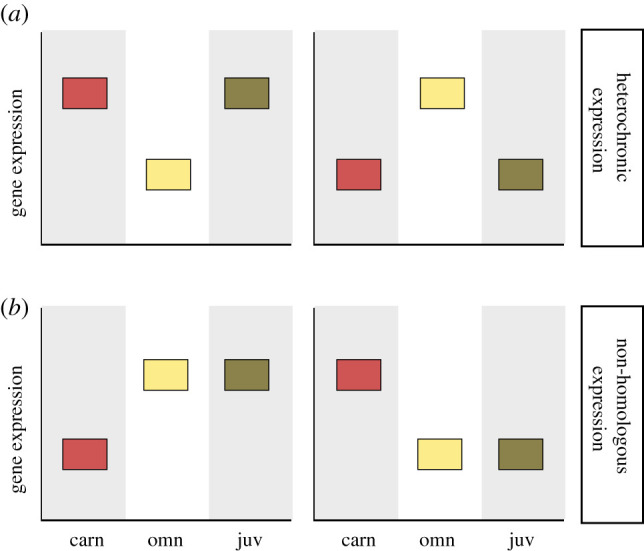

I hypothesized that the predaceous behaviour of Spea larvae—a novel larval feeding behaviour among anurans—is the precocious expression of their post-metamorphic (juvenile and adult) feeding behaviour, which is obligately predaceous. Assuming that there is a transcriptional signature of feeding behaviour in brains, I made the following predictions: if the novel larval feeding behaviour is a product of accelerated gene expression, carnivorous larvae should share a greater degree of gene expression with juveniles than omnivorous larvae; alternatively, if the novel larval feeding behaviour is non-homologous to juvenile feeding behaviour, then carnivorous larvae should exhibit a greater proportion of genes with characteristic (i.e. different than both juveniles and omnivores) expression (figure 1). I further hypothesized that if the novel larval feeding behaviour is non-homologous to juvenile behaviour within this species, then genes with characteristic expression in carnivores would have conserved behavioural functions in other taxa.

Figure 1.

Alternative predictions for heterochronic and non-homologous gene-expression contributing to a novel, predaceous behaviour in spadefoot larvae. (a) Depicts a prediction supporting the molecular heterochrony hypothesis, wherein gene expression in carnivore larvae (carn) is shared with juveniles (juv) due to their shared feeding behaviour (indicated by grey shading). (b) Depicts an alternative prediction whereby carnivore larvae possess novel gene-expression relative to the ancestral type omnivore (omn) larvae that is not similar to juvenile gene-expression. Two graphs are provided for each panel to demonstrate potential increases and decreases in gene expression. (Online version in colour.)

2. Material and methods

(a). Animal collection and breeding

Spea bomifrons (plains spadefoot toad) adults were collected near Wilcox, AZ in the summer of 2018. Individuals had been housed in a colony at Indiana University (IU) before experiments commenced in the summer of 2019. Male and female adults were injected with 0.05–0.1 ml luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (Sigma L-7134) to induce breeding and were left in nursery tanks filled with water for 8 h. Breeding and tadpole rearing were carried out in a room maintained at 25°C on a 12 L : 12 D reverse light cycle. All procedures were carried out in compliance with the Bloomington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at IU under protocol no. 18-011-3.

One sibship was used for this experiment. After hatching (3 days after breeding), larvae from the sibship were transferred in groups of five to microcosms filled with 800 ml of water, which were then randomized and interspersed on racks in the same room. In Spea, feeding detritus to larvae is highly correlated with the development of omnivorous behaviour, and feeding larvae shrimp is highly correlated with the development of carnivorous behaviour [19,20]. Thus, on the same day they were transferred to microcosms, larvae were fed either brine shrimp nauplii (Artemia sp.) or ground commercial fish food (hereafter ‘detritus’). Ground fish food and brine shrimp resemble the detritus and anostracan shrimp, respectively, that Sp. bombifrons encounters in nature [19,21]. Because, in nature, the shrimp that spadefoots feed upon undergo metamorphosis from nauplii to adults, those microcosms originally fed Artemia nauplii were switched on the fourth day of feeding (i.e. 7 days after eggs were laid) to a diet of adult brine shrimp to mirror this transition. Each diet treatment was represented by 48 microcosms, such that a total of 480 tadpoles were used across treatments.

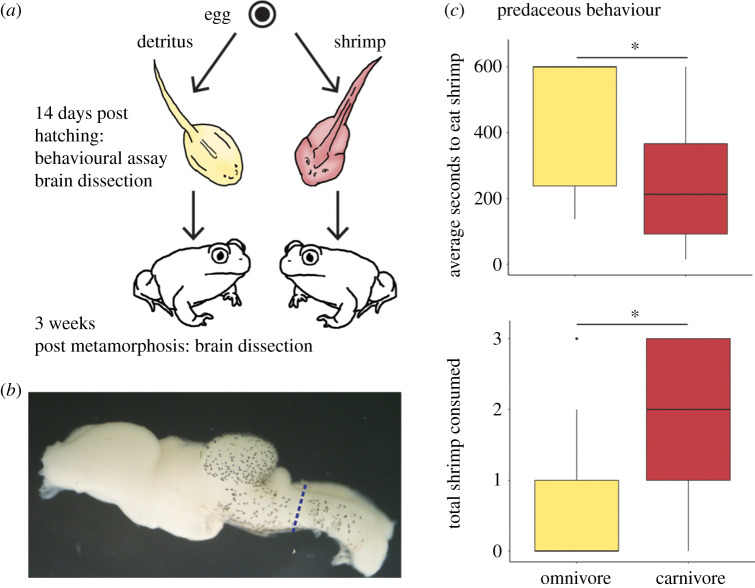

On the 17th day after eggs were laid, 24 carnivores from the shrimp treatment and 24 omnivores from the detritus treatment were selected. These individuals were first subjected to a larval behavioural assay (described below) to confirm that the diet treatment altered their behaviours. Tadpoles within each morph assignment were randomly distributed among two sampling categories—a larval time point and a juvenile time point—resulting in four classes of animals: (i) omnivores; (ii) carnivores; (iii) juveniles that were omnivores as larvae; and (iv) juveniles that were carnivores as larvae (figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Induction of omnivore and carnivore phenotypes in Spea bombifrons. (a) Omnivores (yellow) and carnivores (red) were induced by feeding tadpoles pure diets of either detritus or shrimp. At 14 days post-hatching, they were assayed for behaviour and, for a subset of individuals, their brains were dissected. The remaining tadpoles were raised on their respective diets until three weeks post-metamorphosis, at which point their brains were dissected. (b) Brain tissue anterior (left) of the dashed line was used for RNA extractions. (c) At 14 days post-hatching, carnivores took significantly (p < 0.05) less time on average to consume all shrimp and ate significantly more shrimp in total. Lines within boxes are median values and whiskers extend to the most extreme data points that are not outliers. (Online version in colour.)

(b). Behavioural assays and dissections

To confirm that the diet treatments modified larval behaviours, all tadpoles underwent shrimp-feeding assays. Individuals were first placed into opaque plastic containers containing 200 ml aged, dechlorinated water. Subsequently, three brine shrimp were introduced, and tadpoles were observed continuously to measure the time it took each to capture and consume each shrimp as well as the total number of shrimp consumed. The assay was stopped after 10 min. In instances where an individual consumed no shrimp, the average time to consume shrimp was recorded as 600 s (the maximum time). The reported behaviour results reflect the 35 individuals that were ultimately used for transcriptional analyses. Significant differences in tadpoles' average time to consume shrimp, which were non-normally distributed, were assessed using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Significant differences in the total number of shrimp consumed by tadpoles were assessed using a generalized linear model with a Poisson error distribution [22].

Following the larval behavioural assay, individuals in the larval sampling category were anaesthetized in MS-222, and brains were dissected out using RNAase-free equipment and stored in 400 μL RNAlater (Sigma). The rest of the focal animals (i.e. those in the juvenile sampling category) were placed individually in new microcosms and continued on their assigned diets for the duration of the experiment. As individuals' forearms emerged, they were transferred to private ‘beaches' containing both sand and water where they completed metamorphosis. Once their tails were completely resorbed, individuals were transferred to microcosms containing only moist sand and were feed crickets daily. At three weeks after tail resorption, the juveniles' brains were dissected (figure 2b).

I compared the whole-brain gene expression across larvae and juveniles because there was no a priori reason to believe that predaceous behaviour in tadpoles was governed by a specific brain region. Thus, while a whole-brain approach may have masked subtle region-specific changes in gene expression associated with predaceous behaviour, this limitation makes the revealed patterns more conservative.

(c). Gene expression analyses

After removing samples with low (i.e. <7.5) RNA integrity numbers, the following sample sizes were available for differential gene expression analyses: omnivores (n = 10); carnivores (n = 6); juveniles that were omnivores as larvae (n = 9); and juveniles that were carnivores as larvae (n = 10). Full methods for RNA extraction, quantification, library construction, sequencing, read trimming, transcriptome assembly and annotation, and read counting are provided as electronic supplementary material, Methods. Briefly, RNA libraries were sequenced using the NextSeq75 (Illumina) and MiSeq600 (Illumina) platforms. The final transcriptome contained 92 938 transcripts. From a total of 5310 benchmarking universal single-copy orthologue (BUSCO) groups searched, 89.1% were categorized as complete (74.9% as single-copy and 14.2% as duplicated), 2% as fragmented and 8.9% as missing BUSCOs. 21 238 of the transcripts were annotated to gene level for use in differential gene expression and pathway analyses.

Trimmed reads were assembled using Trinity [23] and SPAdes [24] and combined using an Evigene [25] pipeline. The quality of the assembly was assessed using BUSCO statistics. Resulting transcripts were blasted against Swissprot, the X. tropicalis proteome (ENSEMBL) and the S. multiplicata proteome [26], and the results were combined using the Trinotate [27] pipeline, which also added KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) and Gene Ontology terms for annotated proteins (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Salmon [28] was used to map and quantify original transcripts, and the resulting counts were imported to R using the package tximport [29]. A gene table was generated using the package DESeq2 [30] and merged with annotations from Trinotate.

I used three approaches to determine which of the two larval treatments was more similar to juveniles with respect to brain gene-expression. First, I visually assessed the data using principal component analysis (PCA). Second, I performed a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) using the R package pheatmap [31] on variance stabilized counts to determine clusters of similar levels of gene expression at a genome-wide level. Specifically, I considered the 9992 genes which possessed at least one experiment-wide significant difference (padj < 0.05) across the four groups (carnivores, omnivores and juveniles derived from either carnivores or omnivores) as determined by a likelihood ratio test implemented in DESeq2 (clustering results for all replicates and all genes are provided in electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Relationships between groups were determined using Euclidean distances.

Third, I used differential gene expression analysis to compare animal groups. To correct for multiple hypothesis testing, only genes that were significant in a global likelihood ratio test across the four animal groups (see above) proceeded to assessment at a pairwise level [32]. The experiment-wide corrected gene list was then analysed in a GLM using an animal group as a factor with four levels, from which pairwise comparisons were extracted. I specifically quantified the number of significantly (padj) differentially expressed genes in three contrasts: (i) carnivore larvae versus juveniles derived from carnivores; (ii) omnivore larvae versus juveniles derived from omnivores; and (iii) carnivore larvae versus omnivore larvae.

The differentially expressed genes from these contrasts were used to make gene lists that were characteristic of either carnivore or omnivore larvae (method summarized in electronic supplementary material, figure S3). Genes expressed characteristically by omnivores were those significantly different from juveniles derived from omnivores (contrast ii) and significantly different from carnivores (contrast iii), and in the same direction (figure 1a). Likewise, genes expressed uniquely by carnivores were those significantly different from juveniles derived from carnivores (contrast i) and significantly different from omnivores (contrast iii), and in the same direction (figure 1b). Genes expressed characteristically by carnivores provide evidence for non-homologous, rather than heterochronic, gene-expression. These gene lists were used in enrichment analyses, below. A parallel method for generating these lists—by contrasting either omnivores or carnivores to all remaining groups—yielded qualitatively similar results and is presented in the electronic supplementary material.

(d). Gene Ontology analysis

To further understand in what ways carnivores were characteristically different from omnivores and juveniles, I performed Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analyses on genes whose expression was characteristic of either carnivores or omnivores using ‘Biological Processes' annotations in the topGO package in R using the weighted Fisher's exact test [33]. The default algorithm used by topGO is a weighted algorithm, wherein the p-value of a GO term is conditioned on neighbouring terms and multiple testing theory does not apply. Nevertheless, the false discovery rate (FDR) corrected p-values were also calculated and are provided in electronic supplementary material, table S4.

3. Results

(a). Predaceous behaviour is induced by diet

The shrimp-eating behaviours of tadpoles were significantly influenced by morph (figure 2c); carnivore larvae consumed shrimp faster on average (W = 218.50, p = 0.01) and consumed more overall shrimp (z(33) = 2.64, p < 0.001).

(b). Predaceous behaviour is associated with characteristically expressed genes

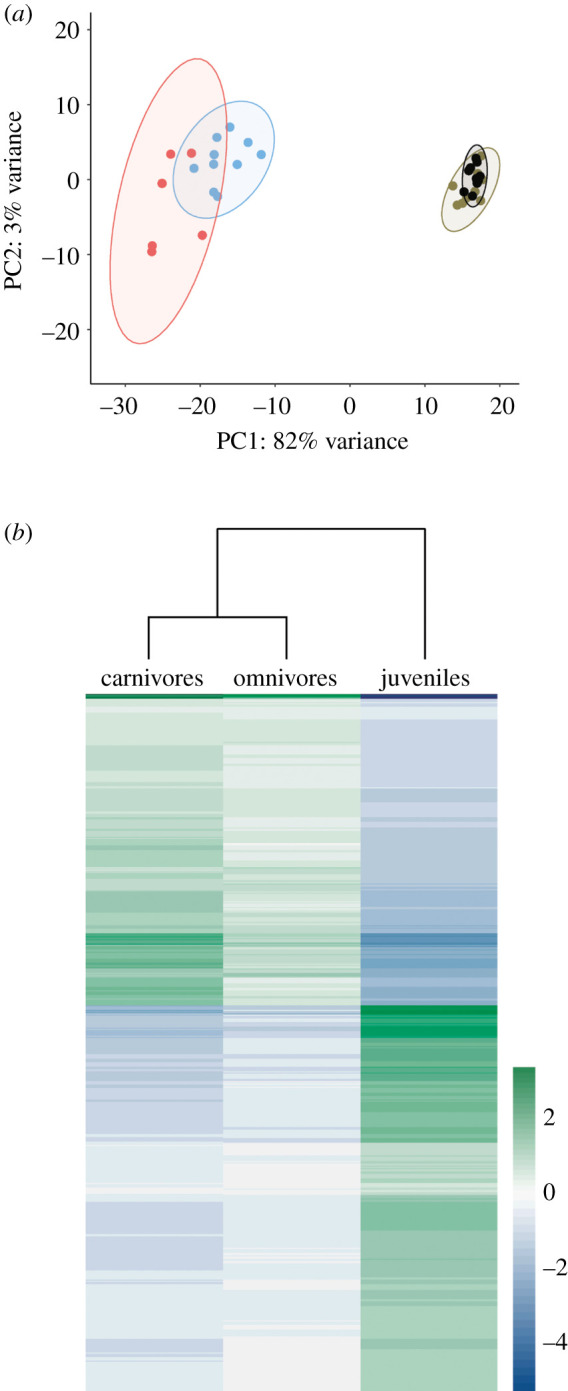

Two lines of evidence from this study reject widespread heterochronic gene expression as a mechanism contributing to the novel predaceous behaviour in Spea tapdoles. First, the principal component analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis grouped gene-expression patterns of omnivore and carnivore larvae together rather than grouping gene-expression patterns of carnivores with juveniles (figure 3). Second, this result was mirrored by the number of significant gene expression patterns characteristic of either ecomorph (electronic supplementary material, table S4). Carnivores possessed 1481 genes with a characteristic expression pattern while omnivores possessed only 102. Thus, the transcriptional profiles suggest a limited role for heterochronic gene-expression in promoting the novel predaceous behaviour.

Figure 3.

Brain gene-expression in larval carnivore, larval omnivore and juvenile Spea bombifrons. (a) Clustering of brain gene-expression based on principal component analysis of genes significantly different among at least one of the animal groups (padj < 0.05) are presented. Omnivore larvae are depicted in blue; carnivore larvae are depicted in red; juveniles derived from omnivore are depicted in brown; juveniles derived from carnivore are depicted in black. (b) Hierarchical clustering analysis of brain gene-expression patterns shows that carnivores are not more similar to juveniles than are omnivores. Each row in the heat map represents a gene with a significant difference (padj < 0.05) in expression across animal groups. For clarity, juveniles derived from each diet are grouped and 600 of the 9992 genes with the smallest padj are shown. Colours represent the mean expression level of that gene across all individuals minus the mean expression level of that gene across individuals within a group; green and blue indicate relative over- and under-expression, respectively, while white indicates more intermediate levels of expression. (Online version in colour.)

To further understand the function of genes characteristically expressed in the brains of carnivore and omnivore larvae, I assessed how they were enriched in GO categories. Notably, gene expression characteristic of carnivore larvae was enriched in GO categories related to learning, memory and social behaviour (table 1; electronic supplementary material, table S5). These genes included many candidates that, in other taxa, modulate behaviours that might contribute to the novel predaceous behavioural phenotype of Spea carnivores (figure 4; see Discussion).

Table 1.

Gene Ontology enrichment. Listed are Gene Ontology categories that were enriched among genes characteristically expressed in carnivore or omnivore brains. Full results are listed in electronic supplementary material, table S4.

| GO category | group ID | genes in group | significant genes in group | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| enriched among genes characteristically expressed in carnivores | ||||

| learning | GO:0007612 | 98 | 25 | 3.40 × 10−6 |

| regulation of NMDA receptor activity | GO:2000310 | 12 | 6 | 5.70 × 10−5 |

| memory | GO:0007613 | 90 | 17 | 0.003 |

| negative regulation of insulin secretion | GO:0061179 | 5 | 3 | 0.003 |

| brain development | GO:0007420 | 501 | 70 | 0.003 |

| visual learning | GO:0008542 | 31 | 7 | 0.004 |

| cerebral cortex development | GO:0021987 | 72 | 10 | 0.004 |

| insulin secretion | GO:0030073 | 142 | 16 | 0.004 |

| long-term synaptic potentiation | GO:0060291 | 62 | 12 | 0.006 |

| startle response | GO:0001964 | 20 | 6 | 0.006 |

| social behaviour | GO:0035176 | 34 | 7 | 0.006 |

| long-term memory | GO:0007616 | 29 | 6 | 0.011 |

| NMDA glutamate receptor clustering | GO:0097114 | 3 | 2 | 0.013 |

| hippocampus development | GO:0021766 | 48 | 8 | 0.013 |

| behavioural fear response | GO:0001662 | 19 | 5 | 0.019 |

| trans-synaptic signalling by BDNF | GO:0099183 | 4 | 2 | 0.024 |

| positive regulation of long-term neuronal synaptic plasticity | GO:0048170 | 4 | 2 | 0.024 |

| adult behaviour | GO:0030534 | 100 | 17 | 0.031 |

| enriched among genes characteristically expressed in omnivores | ||||

| neuropeptide signalling pathway | GO:0007218 | 82 | 4 | 0.001 |

| visual perception | GO:0007601 | 157 | 5 | 0.004 |

| feeding behaviour | GO:0007631 | 61 | 4 | 0.008 |

| somatostatin secretion | GO:0070253 | 5 | 1 | 0.023 |

| response to food | GO:0032094 | 19 | 2 | 0.027 |

| growth hormone receptor signalling pathway | GO:0060397 | 6 | 1 | 0.028 |

| adult feeding behaviour | GO:0008343 | 10 | 1 | 0.045 |

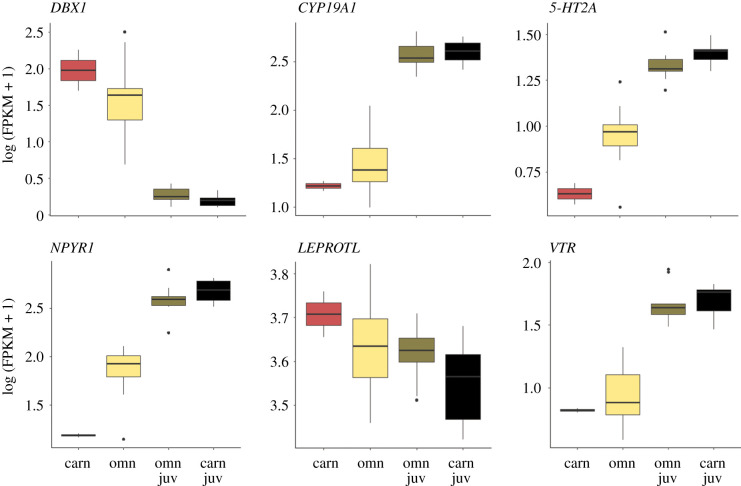

Figure 4.

Patterns of brain gene expression in candidate genes for feeding and aggression in carnivorous tadpoles. Boxplots display select genes pertinent to the novel predaceous behaviour that were characteristically expressed in carnivore (carn) brains relative to omnivores (omn) and juveniles (‘juv', derived from either omnivores in brown or carnivores in black). Lines within boxes are median values of natural log transformed gene-expression and whiskers extend to the most extreme data points that are not outliers (indicated by dots). Abbreviations: DBX1, developing brain homeobox 1; CYP19A1, aromatase; 5-HT2A, serotonin receptor 2A; NPYR1, neuropeptide Y receptor Y1; LEPROTL, leptin receptor overlapping transcript (homologue of X. laevis leptin receptor overlapping transcript-like); VTR, vasotocin receptor. (Online version in colour.)

4. Discussion

Heterochronic shifts have historically been implicated as a major mechanism generating evolutionary innovation [34], including novel behavioural phenotypes [4]. One important prediction from this hypothesis is that shifts in the developmental onset of phenotypes will be mirrored by shifts in gene expression profiles, and specifically brain gene expression when the phenotype under consideration is a behaviour [11]. Although there are several vertebrate examples in which heterochrony is invoked as the mechanism underlying behavioural variants [35,36], there are very few empirical studies to support this mechanism at a molecular level (although see [37]). Here, I provide a test of the molecular heterochrony hypothesis using a species from a spadefoot toad clade that has evolved a novel larval feeding behaviour. I found that the transcriptional profiles of larval carnivore brains are not more similar to those of juvenile brains than are larval omnivore brains. Instead, a novel suite of gene expression associated with learning, memory and social behaviour in other taxa is associated with the novel predaceous behaviour in carnivore larvae. Thus, the expression of genes—specifically, those with conserved behavioural functions—in a novel context can provide a substrate for new and complex behaviours.

These findings indicate that the predaceous and often cannibalistic behaviours of carnivore tadpoles are not homologous to, but fundamentally different than, the predaceous behaviours of juveniles. Although seemingly similar, there may be important ways in which carnivory differs before and after metamorphosis. For instance, whereas carnivore larvae may need to modify their social behaviours in order to consume kin, or even avoid consuming kin [38,39], juveniles—which consume terrestrial invertebrates [40]—would not require such social decision making. Likewise, carnivores are characterized as behaviourally bold (sensu [41]), yet it would be imprecise to liken the boldness of carnivorous larvae to juveniles given that they encounter different predators and risks in their respective environments. These results underscore the importance of characterizing the mechanisms underlying behavioural traits before inferring homology, even across life stages within the same species.

If gene expression associated with the induction of predaceous larval behaviours does not reflect a shift in the timing of existing developmental pathways, where do these ‘novel’ patterns come from? The behavioural genetic toolkit theory proposes that when organisms evolve similar behaviours due to shared ecological conditions and selective pressures, they will also use the same underlying genetic pathways [42,43]. Although I identified no candidate genes or pathways modulated in carnivore larvae that are associated with cannibalism per se, significant differences did occur in genes and pathways associated with behaviours in other vertebrates that represent components of the carnivore larvae's predaceous behaviour. For instance, vasotocin signalling in amphibians and other animals (as vasopressin in mammals) is widely appreciated as a mediator of social interactions [44,45], and such interactions are also likely to be important in the cannibalistic actions of the carnivore morph [38,39]. Additionally, vasotocin and serotonin signalling, as well as aromatase activity, are all associated with aggression [46–49], a key component of the larval carnivore's behaviour. Finally, neuropeptide Y receptor has a conserved role in feeding behaviours [50]. Given these parallels, my results suggest that the novel larval behaviour in spadefoots is a mosaic of behavioural elements seen in other contexts [51,52]. Future functional experiments validating the role of these individual genes in the expression of predaceous behaviour would shed light on whether the behavioural toolkit was key to promoting the evolution of this novel trait.

In this study, I found limited evidence for widespread heterochronic gene expression in the brains of carnivore larvae. It is important, however, to acknowledge that a heterogeneous sample such as a whole brain may not have revealed otherwise important transcriptional differences more locally. Specifically, it is additionally possible that heterochronic changes in a small number of feeding- or aggression-related neurons in carnivores may also be important but are obscured by the more pervasive, brain-wide patterns that I report here. Thus, while the results from the current study should reject widespread heterochrony in the origins of this novel larval behaviour, future studies of specific brain regions or neurons might reveal whether heterochrony plays a more targeted role in its expression.

Here I have tested the molecular heterochrony hypothesis in a vertebrate species, specifically with respect to the evolution of predaceous larval feeding, a novel and complex behaviour. Although this hypothesis has garnered support in several other systems [13,14,53], my results indicate that non-homologous gene expression—specifically the expression of genes with conserved behavioural functions in other taxa—fuelled the emergence of this particular behavioural innovation. Further, my results establish spadefoots as a model to empirically assay and comparatively analyse genes underlying a recently evolved behaviour. For instance, assessing transcriptional variation among species and families of Scaphiopus—a closely related spadefoot clade that does not produce the carnivore morph—that correlates with behavioural components of carnivory (e.g. aggression) may reveal pathways that preceded and facilitated the evolution of the more complex, predaceous behaviour shown by Spea larvae. Even within Spea, species and populations experiencing different ecological pressures have evolved to either express the behaviour more frequently and drastically [54] or suppress the behaviour altogether, even in the presence of the inducing cue [55]. Although the results from this study do not support widespread heterochrony in promoting the novel predaceous behaviour in the Sp. bombifrons population assessed, it is possible that heterochrony or other mechanisms, such as protein evolution or novel genes (e.g. [56,57]), additionally, or instead, contribute to the behaviour's expression in other species and populations. The reference point established here will allow the distinction among multiple possible routes to behavioural innovation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

I thank Erik Ragsdale and Sarah Lagon for their helpful comments on the manuscript; Aaron Buechlein and Doug Rusch of the IU Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics for their support; Christyn Willis and Ian Carrico for collecting behaviour data; Karin and David Pfennig for their advice while collecting animals; and the Southwestern Research Station.

Ethics

The animals and experiments in this study were approved by the Bloomington Indiana University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol no. 18-011-7).

Data accessibility

The RNA-seq data produced for this research are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fn2z34tsd [58].

Authors' contributions

C.C.L.-R. collected the animals, designed and performed the research, analysed the data and wrote the paper.

Competing interests

I declare I have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation (grant DEB-1754136).

References

- 1.Allf BC, Durst PAP, Pfennig DW. 2016. Behavioral plasticity and the origins of novelty: the evolution of the rattlesnake rattle. Am. Nat. 188, 475-483. ( 10.1086/688017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price TD, Qvarnström A, Irwin DE. 2003. The role of phenotypic plasticity in driving genetic evolution. Proc. R. Soc. B 270, 1433-1440. ( 10.1098/rspb.2003.2372) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoekstra HE, Coyne JA. 2007. The locus of evolution: Evo Devo and the genetics of adaptation. Evolution 61, 995-1016. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00105.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West-Eberhard MJ. 2003. Developmental plasticity and evolution. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner GP, Lynch VJ. 2010. Evolutionary novelties. Curr. Biol. 20, R48-R52. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wray GA. 2007. The evolutionary significance of cis-regulatory mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 206-216. ( 10.1038/nrg2063) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehan SM, Toth AL. 2015. Climbing the social ladder: the molecular evolution of sociality. Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 426-433. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2015.05.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toth AL, Robinson GE. 2007. Evo-devo and the evolution of social behavior. Trends Genet. 23, 334-341. ( 10.1016/j.tig.2007.05.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh JT, Signorotti L, Linksvayer TA, d'Ettorre P. 2018. Phenotypic correlation between queen and worker brood care supports the role of maternal care in the evolution of eusociality. Ecol. Evol. 8, 10 409-10 415. ( 10.1002/ece3.4475) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raff RA, Wray GA. 1989. Heterochrony: developmental mechanisms and evolutionary results. J. Evol. Biol. 2, 409-434. ( 10.1046/j.1420-9101.1989.2060409.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linksvayer TA, Wade MJ. 2005. The evolutionary origin and elaboration of sociality in the aculeate hymenoptera: maternal effects, sib-social effects, and heterochrony. Q. Rev. Biol. 80, 317-336. ( 10.1086/432266) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West-Eberhard MJ. 1987. Flexible strategy and social evolution. In Animal societies: theories and facts (eds Brown IY, Kikkawa J), pp. 35-51. Tokyo, Japan: Scientific Society Press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toth AL, et al. 2007. Wasp gene expression supports an evolutionary link between maternal behavior and eusociality. Science 318, 441-444. ( 10.1126/science.1146647) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodard SH, Bloch GM, Band MR, Robinson GE. 2014. Molecular heterochrony and the evolution of sociality in bumblebees (Bombus terrestris). Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20132419. ( 10.1098/rspb.2013.2419) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster SA. 2013. Evolution of behavioural phenotypes: influences of ancestry and expression. Anim. Behav. 85, 1061-1075. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.02.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pomeroy LV. 1981. Developmental polymorphism in the tadpoles of the spadefoot toad Scaphiopus multiplicatus. Riverside, CA: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ledón-Rettig CC, Pfennig DW. 2011. Emerging model systems in eco-evo-devo: the environmentally responsive spadefoot toad. Evol. Dev. 13, 391-400. ( 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2011.00494.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ledon-Rettig CC, Pfennig DW, Nascone-Yoder N. 2008. Ancestral variation and the potential for genetic accommodation in larval amphibians: implications for the evolution of novel feeding strategies. Evol. Dev. 10, 316-325. ( 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00240.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfennig DW, Rice AM, Martin RA. 2006. Ecological opportunity and phenotypic plasticity interact to promote character displacement and species coexistence. Ecology 87, 769-779. ( 10.1890/05-0787) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfennig DW, Rice AM, Martin RA. 2007. Field and experimental evidence for competition's role in phenotypic divergence. Evolution 61, 257-271. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00034.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfennig DW, Mabry A, Orange D. 1991. Environmental causes of correlations between age and size at metamorphosis in Scaphiopus multiplicatus. Ecology 72, 2240-2248. ( 10.2307/1941574) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Hara RB, Kotze DJ. 2010. Do not log-transform count data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 118-122. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2010.00021.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haas BJ, et al. 2013. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494-1512. ( 10.1038/nprot.2013.084) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bankevich A, et al. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455-477. ( 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert DG. 2013. Gene-omes built from mRNA-seq not genome DNA. In 7th Annu. Arthropod Genomics Symp. ( 10.7490/f1000research.1112594.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seidl F, Levis NA, Schell R, Pfennig DW, Pfennig KS, Ehrenreich IM. 2019. Genome of Spea multiplicata, a rapidly developing, phenotypically plastic, and desert-adapted spadefoot toad. G3 Genes, Genomes, Genet. 9, 3909-3919. ( 10.1534/g3.119.400705) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bryant DM, et al. 2017. A tissue-mapped axolotl de novo transcriptome enables identification of limb regeneration factors. Cell Rep. 18, 762-776. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.063) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. 2017. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417-419. ( 10.1038/nmeth.4197) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD. 2016. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Research 4, 1521. ( 10.12688/F1000RESEARCH.7563.2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. ( 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolde R. 2012. Pheatmap: pretty heatmaps. R package version 1.0.10.

- 32.Van den Berge K, Soneson C, Robinson MD, Clement L. 2017. stageR: a general stage-wise method for controlling the gene-level false discovery rate in differential expression and differential transcript usage. Genome Biol. 18, 1-14. ( 10.1186/s13059-017-1277-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexa A, Rahnenführer J. 2010. topGO: enrichment analysis for Gene Ontology. R pakcage version 2.10.0. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gould SJ. 1977. Ontogeny and phylogeny. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Universty Press. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Behringer V, Deschner T, Murtagh R, Stevens JMG, Hohmann G. 2014. Age-related changes in thyroid hormone levels of bonobos and chimpanzees indicate heterochrony in development. J. Hum. Evol. 66, 83-88. ( 10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.09.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gariépy JL, Bauer DJ, Cairns RB. 2001. Selective breeding for differential aggression in mice provides evidence for heterochrony in social behaviours. Anim. Behav. 61, 933-947. ( 10.1006/anbe.2000.1700) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu Y, et al. 2018. Spatiotemporal transcriptomic divergence across human and macaque brain development. Science 362, eaat8077. ( 10.1126/science.aat8077) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfennig DW. 1999. Cannibalistic tadpoles that pose the greatest threat to kin are most likely to discriminate kin. Proc. R. Soc. B 266, 1999, 57-61. ( 10.1098/rspb.1999.0604) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfennig DW, Reeve HK, Sherman PW. 1993. Kin recognition and cannibalism in spadefoot toad tadpoles. Anim. Behav. 46, 87-94. ( 10.1006/anbe.1993.1164) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson AM, Haukos DA, Anderson JT. 1999. Diet composition of three anurans from the Playa wetlands of northwest Texas. Copeia 1999, 515. ( 10.2307/1447502) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sloan Wilson D, Clark AB, Coleman K, Dearstyne T. 1994. Shyness and boldness in humans and other animals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 9, 442-446. ( 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90134-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rittschof CC, Robinson GE.. 2016. Behavioral genetic toolkits : toward the evolutionary origins of complex phenotypes. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 119, 157-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toth AL, Rehan SM. 2017. Molecular evolution of insect sociality: an eco-evo-devo perspective. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 62, 419-442. ( 10.1146/annurev-ento-031616-035601) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fischer EK, Roland AB, Moskowitz NA, Tapia EE, Summers K, Coloma LA, O'Connell LA. 2019. The neural basis of tadpole transport in poison frogs. Proc. R. Soc. B 286, 20191084. ( 10.1098/rspb.2019.1084) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore FL, Boyd SK, Kelley DB. 2005. Historical perspective: hormonal regulation of behaviors in amphibians. Horm. Behav. 48, 373-383. ( 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.05.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilczynski W, Quispe M, Muñoz MI, Penna M. 2017. Arginine vasotocin, the social neuropeptide of amphibians and reptiles. Front. Endocrinol. 8, 186. ( 10.3389/fendo.2017.00186) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodson JL, Bass AH. 2001. Social behavior functions and related anatomical characteristics of vasotocin/vasopressin systems in vertebrates. Brain Res. Rev. 35, 246-265. ( 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00043-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elipot Y, Hinaux H, Callebert J, Rétaux S. 2013. Evolutionary shift from fighting to foraging in blind cavefish through changes in the serotonin network. Curr. Biol. 23, 1-10. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.044) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Black MP, Balthazart J, Baillien M, Grober MS. 2005. Socially induced and rapid increases in aggression are inversely related to brain aromatase activity in a sex-changing fish, Lythrypnus dalli. Proc. R. Soc. B 272, 2435-2440. ( 10.1098/rspb.2005.3210) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crespi EJ, Denver RJ. 2012. Developmental reversal in neuropeptide Y action on feeding in an amphibian. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 177, 348-352. ( 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.04.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cunningham CB, VanDenHeuvel K, Khana DB, McKinney EC, Moore AJ. 2016. The role of neuropeptide F in a transition to parental care. Biol. Lett. 12, 20160158. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0158) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cunningham CB, Badgett MJ, Meagher RB, Orlando R, Moore AJ. 2017. Ethological principles predict the neuropeptides co-opted to influence parenting. Nat. Commun. 8, 1-6. ( 10.1038/ncomms14225) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rehan SM, Berens AJ, Toth AL. 2014. At the brink of eusociality: transcriptomic correlates of worker behaviour in a small carpenter bee. BMC Evol. Biol. 14, 260. ( 10.1186/s12862-014-0260-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pfennig DW, Martin RA. 2010. Evolution of character displacement in spadefoot toads: different proximate mechanisms in different species. Evolution 64, 2331-2341. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01005.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rice AM, Leichty AR, Pfennig DW. 2009. Parallel evolution and ecological selection: replicated character displacement in spadefoot toads. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 4189-4196. ( 10.1098/rspb.2009.1337) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dai H, Chen Y, Chen S, Mao Q, Kennedy D, Landback P, Eyre-Walker A, Du W, Long M. 2008. The evolution of courtship behaviors through the origination of a new gene in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7478-7483. ( 10.1073/pnas.0800693105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferreira PG, Patalano S, Chauhan R, Ffrench-Constant R, Gabaldón T, Guigó R, Sumner S. 2013. Transcriptome analyses of primitively eusocial wasps reveal novel insights into the evolution of sociality and the origin of alternative phenotypes. Genome Biol. 14, R20. ( 10.1186/gb-2013-14-2-r20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ledón-Rettig CC. 2021. Data from: Novel brain gene-expression patterns are associated with a novel predaceous behaviour in tadpoles. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.fn2z34tsd) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Ledón-Rettig CC. 2021. Data from: Novel brain gene-expression patterns are associated with a novel predaceous behaviour in tadpoles. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.fn2z34tsd) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The RNA-seq data produced for this research are available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.fn2z34tsd [58].