Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread throughout the world, including Cyprus, Iceland and Malta. Considering the small population sizes of these three island countries, it was anticipated that COVID-19 would be adequately contained and mortality would be low. This study aims to compare and contrast COVID-19 mortality with mortality from all causes and common non-communicable diseases (NCDs) over 8 months between these three islands.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Ministry of Health websites and COVID dashboards from Cyprus, Iceland and Malta. The case-to-fatality ratio (CFR) and years of life lost (YLLs) were calculated. Comparisons were made between the reported cases, deaths, CFR, YLLs, swabbing rates, restrictions and mitigation measures.

Results

Low COVID-19 case numbers and mortality rates were observed during the first wave and transition period in Cyprus, Iceland and Malta. The second wave saw a drastic increase in the number of confirmed cases and mortality rates, especially for Malta, with high CFR and YLLs. Similar restrictions and measures were evident across the three island countries. Results show that COVID-19 mortality was generally lower than mortality from NCDs.

Conclusions

The study highlights that small geographical and population size, along with similar restrictive measures, did not appear to have an advantage against the spread and mortality rate of COVID-19, especially during the second wave. Population density, an ageing population and social behaviours may play a role in the burden of COVID-19. It is recommended that a country-specific syndemic approach is used to deal with the local COVID-19 spread based on the population's characteristics, behaviours and the presence of other pre-existing epidemics.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Mortality, Case fatality rate, Non-communicable disease, Islands, Syndemic, Cyprus, Iceland, Malta

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic spread across the European continent in early 2020, affecting every country in Europe, including the islands of Cyprus, Iceland and Malta. The Republic of Cyprus and Malta are situated within the Mediterranean Sea, while Iceland is situated between the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans. The three islands share similar population characteristics, including a total population of <1 million (Cyprus 875,900; Malta 514,564 and Iceland 364,134) and similar life expectancy among males (Cyprus 78.5 years; Malta 78.9 years and Iceland 79.8 years).

Of these three countries, Iceland reported the first COVID-19 case on the 28th February 2020, followed by Malta (7th March 2020) and Cyprus (9th March 2020).1 Similar to other countries, their governments implemented a number of restrictions to curb the viral spread during the first wave, and these were subsequently reintroduced in late summer when the second wave prevailed.1 It was hypothesised that the small geographical and population sizes of these three islands would be an advantage, in addition to the implementation of COVID-19 measures, to curb the viral spread and keep the mortality rate low. This study aims to compare and contrast COVID-19 mortality with mortality from all causes and common non-communicable diseases (NCDs) over 8 months (March to November 2020) between the three small islands of Cyprus, Iceland and Malta.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Ministry of Health websites and COVID-19 dashboards from Cyprus, Iceland and Malta, in addition to local published studies. Comparisons were made between the reported cases, deaths, swabbing rates, restrictions and mitigation strategies. No distinction was made between individuals dying ‘with’ COVID-19 and individuals dying ‘due to’ COVID-19 as a result of lack of such data from Iceland and Malta.

The reported COVID-19–positive cases and deaths were subdivided into three phases: (1) the first wave (6th March to 7th May); (2) the transitional period (8th May to 13th August) and (3) the second wave (14th August to 30th November). The case-to-fatality ratio (CFR) for each COVID-19 phase was calculated by subdividing the confirmed number of positive cases by the confirmed number of deaths and then multiplying by 100.2

Years of life lost (YLLs) is a metric used in population health to measure the number of years lost due to premature death from a particular cause. This metric is calculated by identifying the number of deaths in an age group and multiplying it by a standard life expectancy for that particular age group. The World Health Organization life expectancy age group tables for each country were used for this analysis.3 The number of deaths by age groups and gender was obtained from the COVID-19 dashboards of each island. The COVID-19 YLLs for each island (Cyprus, Iceland and Malta) were compared with the YLLs of common NCDs (cardiovascular disease, stroke, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus) and road traffic injuries, as reported by the Global Burden of Disease for the year 2019.4

Results

Covid-19 situation in Cyprus, Iceland and Malta

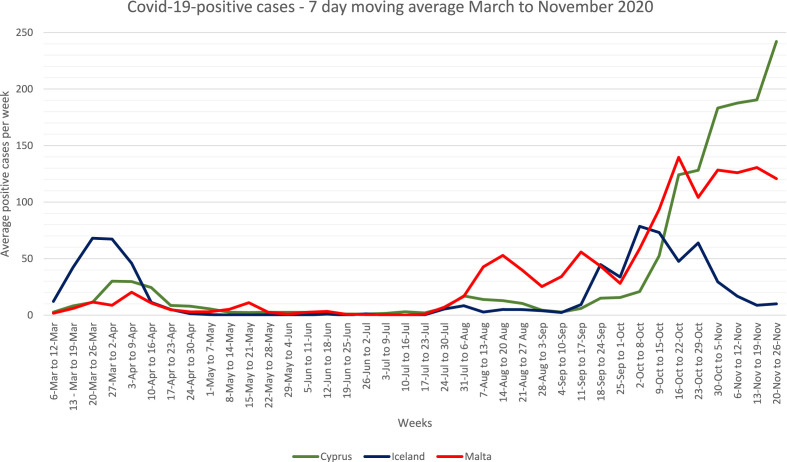

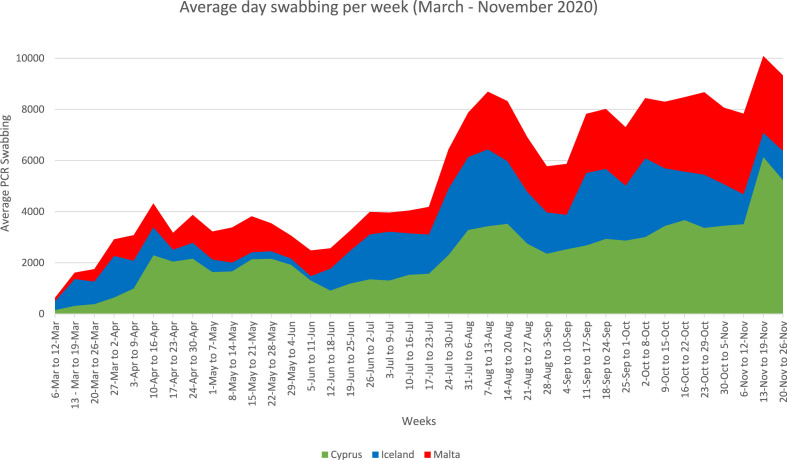

From the onset of the pandemic until the end of November 2020, Cyprus reported 10,583 COVID-19–positive cases (1206 per 100,000), Iceland reported 5027 positive cases (1381 per 100,000) and Malta reported 9877 positive cases (1919 per 100,000).5, 6, 7 Over the study period of 8 months, the daily average number of new COVID-19 cases was 223 for Cyprus, 14 for Iceland and 117 for Malta. During the first wave (March–May 2020), Iceland reported the highest number of positive cases, as shown in Fig. 1 . However, of the three islands, Malta entered the second wave earlier and reported the highest number of positive cases.1 , 8 In mid-October, Cyprus reported a spike in cases, exceeding the number of positive cases reported by Iceland and Malta (Fig. 1). Concurrently, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) COVID-19 swabbing test rate increased over time across the three islands (Fig. 2 ), with Cyprus reaching 70,714.35 per 100,000 PCR swabs by the end of November, while Iceland recorded 107,478.84 per 100,000 and Malta 83,542.54 per 100,000.5, 6, 7

Fig. 1.

COVID-19–positive cases: 7-day moving average for Cyprus, Iceland and Malta between March and November 2020.5, 6, 7

Fig. 2.

COVID-19 average PCR swabbing rate for Cyprus, Iceland and Malta between March and November 2020.5, 6, 7 PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

COVID-19 mortality in Cyprus, Iceland and Malta

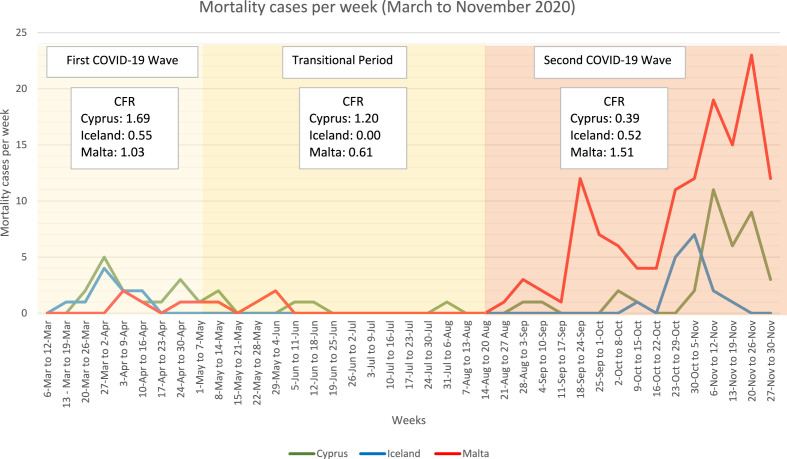

A synergistic relationship between the number of COVID-19–positive cases and the mortality rate was expected as a result of the high infectivity rate and morbidity related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Of these three islands, Malta reported the highest rate of COVID-19 mortality since the onset of the pandemic with 27.31 per 100,000 population, followed by Iceland with 7.14 per 100,000 population and Cyprus with 6.39 per 100,000 population. On subdividing the 8-month study period of the pandemic into three phases, as shown in Fig. 3 , it can be seen that the islands experienced a higher mortality rate during the second wave, which coincides with higher community spread and identified cases. All three islands reported the spread of COVID-19 within nursing homes, especially during the second wave.6 , 8 , 9 Indeed, Iceland reported extensive COVID-19 spread among the geriatric department of Landakot hospital, as well as within nursing homes and a rehabilitation centre.10

Fig. 3.

COVID-19 mortality cases and CFR in Cyprus, Iceland and Malta between March and November 2020. CFR, case-to-fatality ratio.

CFR was measured to assess the impact of the pandemic on the mortality of the population. Interestingly, even though the second wave showed a higher mortality rate for all three islands, the CFR for Malta exceeded those of the other islands. Indeed, on assessing mortality from COVID-19 as a fraction of the reported all-cause mortality for 2019 for each country, mortality from COVID-19 represented 3.73% of all-cause mortality in Malta, 1.23% in Iceland and 0.64% in Cyprus.4

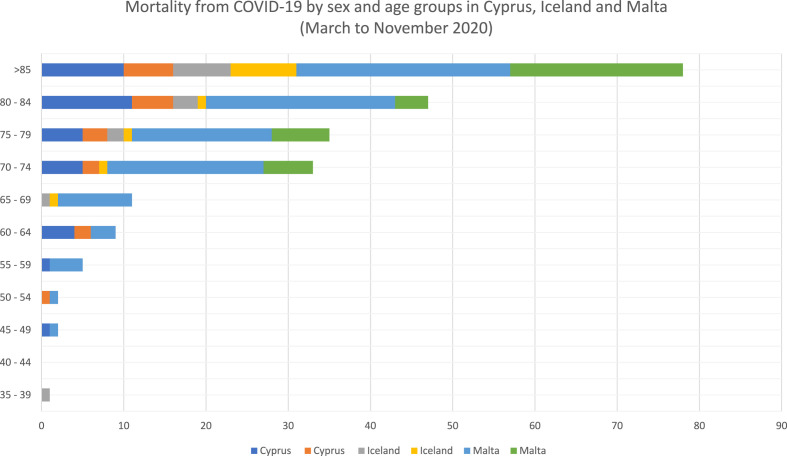

As shown in Fig. 4 , when stratification was performed by age and gender, the highest morality occurrences were seen in men and the elderly (>85 years) across the three islands.

Fig. 4.

COVID-19 mortality by age groups and gender in Cyprus, Iceland and Malta between March and November 2020.

COVID-19 mortality vs mortality from common NCDs and injuries

NCDs have been reported to be responsible for a substantial burden of disease, including increases in years-lived with disability (YLDs) and YLLs.11 Comparisons were made between COVID-19 and common NCDs mortality (per 100,000 population) and YLLs among the populations of Cyprus, Iceland and Malta, as shown in Table 1 . COVID-19 mortality and YLLs were calculated for the study period of 8 months, whereas NCD and injury mortality and YLLs were calculated for the year 2019. However, it is still evident that COVID-19 has resulted in a substantial burden for each of the three island countries, especially Malta. In fact, in Malta, COVID-19 had a higher mortality rate (per 100,000) than road traffic accidents and diabetes mellitus. A similar picture was observed in Iceland; however, in Cyprus, COVID-19 appeared to have a lower disease burden than common NCDs and injuries (until the end of the study period [November 2020]).

Table 1.

Comparison between COVID-19 and common non-communicable disease mortality (per 100,000) and YLLs in Cyprus, Iceland and Malta.a

| Mortality causes | Cyprus |

Iceland |

Malta |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality per 100,000 | YLLs | Mortality per 100,000 | YLLs | Mortality per 100,000 | YLLs | |

| COVID-19b | 6.39 | 684.33 | 7.14 | 273.40 | 27.40 | 1558.80 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 355.34 | 48,033.21 | 198.75 | 9200.09 | 289.77 | 20,557.96 |

| Stroke | 85.11 | 10,176.77 | 40.76 | 1774.29 | 63.96 | 4281.98 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 61.78 | 7417.58 | 30.43 | 1502.00 | 30.56 | 2282.47 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 56.00 | 7086.12 | 7.13 | 392.40 | 23.98 | 1889.28 |

| Road traffic injuries | 15.27 | 5705.54 | 3.11 | 486.51 | 2.89 | 649.42 |

YLLs, years of life lost.

Mortality per 100,000 and YLLs based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (excl. COVID-19).

Mortality over 8 months (March to November 2020).

COVID-19 mortality and restrictive measures

The first wave of COVID-19 resulted in the implementation of a number of extreme restrictive measures, including closure of airports and ports (Cyprus and Malta); closure of non-essential retail, bars, restaurants, schools and restricting the number of people in one gathering (Cyprus, Iceland and Malta). Cyprus also restricted free movement of the population to only a daily trip.1 These measures appear to have been effective as the number of COVID-19 cases and mortality rate remained low (Fig. 1, Fig. 3). Indeed, this led to the slow easing of restrictive measures, while keeping the case numbers and mortality low.1 However, by mid-August, COVID-19 case numbers began to increase again all over Europe, including across the three islands. A distinct spike in COVID-19–positive cases was observed in Malta compared with Cyprus and Iceland, especially after the reopening of schools towards the end of September and beginning of October, with a consequential high mortality rate (Fig. 3). A stepwise control restriction was reintroduced, including a reduction in the number of people attending gatherings, compulsory mask wearing indoors and outdoors and restrictions in non-essential services. Supplement Table S1 provides a list of the different restrictions and measures implemented at the onset of the second wave by Cyprus, Iceland and Malta. Although restrictions were put in place, a substantial mortality rate was still evident, especially for Malta and later on for Cyprus.

Discussion

Small islands are considered to be at an advantage when controlling infectious diseases owing to their small population and geographical sizes. In small islands, containment measures at a population level are anticipated to be easier to implement, thus more efficiently limiting the viral spread than larger countries. The absence of land borders further enabled the successful implementation of containment measures. These advantages played a role during the first wave of COVID-19 and the transition period, where Cyprus, Iceland and Malta had relatively low numbers of COVID-19–positive cases and subsequently low mortality rates when compared with larger neighbouring countries.1 , 12, 13, 14 Of these three small islands, Malta was predominantly in a better containment scenario (not mortality), albeit with their similar restrictions and measures.1 , 15

However, hasty relaxation of restrictions and opening of the airport and ports, in addition to the organisation of large mass events led to the downfall of the stable COVID-19 situation in Malta, giving rise to the second wave.8 Cyprus and Iceland also experienced an increase in COVID-19–positive cases around late summer time. However, a steeper incline in cases along with spikes in mortality occurred in Malta. This study showed that, similar to other countries, these small islands showed a higher mortality among the elderly population, particularly among men.16 Despite similar reintroduction of restrictions at the onset of the second wave in the three islands, the COVID-19 burden in Malta predominated with a higher CFR than that in Cyprus and Iceland. Such CFR differences have been attributed to differences in patient characteristics, prevalence of diagnostic testing and healthcare system availability.17 However, Cyprus and Malta have been reported to have similar patient metabolic characteristics and healthcare system preparedness for COVID-19.1 , 18, 19

The PCR testing strategy in Cyprus, Iceland and Malta has been very similar.1 However, Iceland reported the highest prevalence of testing rate, followed by Malta and Cyprus. Furthermore, a spread within nursing homes was reported in all islands,6 , 8 , 9 which has been anticipated to have detrimental impacts on these elderly populations with subsequential high mortality.20 Indeed, the majority of COVID-19 mortality was among the elderly population in Cyprus, Iceland and Malta.

Considering the similar COVID-19 public health approaches, small populations and geographical aspects shared by Cyprus, Iceland and Malta, the results of this study indicate that other predisposing factors might be contributing to the discrepancy in mortality rates in Malta. Potential factors are a higher ageing population in Malta than Cyprus and Iceland,4 , 21 thus increasing susceptibility to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.22 Another potential factor could be the social behaviours and attitudes of the populations. The population density of each country may have had an effect on the containment measures and viral spread. Malta's population density is much higher (1380 individuals per km2) than that of Cyprus (3.31 individuals per km2) and Iceland (131 individuals per km2). In fact, countries with low population densities, such as Finland and Norway, have exhibited superior viral containment, which has also been influenced by the timely implementation of measures and compliance and trust within the population.23

Notwithstanding the negative COVID-19 pandemic implications on the mortality rate, mental health and well-being, along with the burden on the healthcare systems and economy, the COVID-19 mortality burden (for 8 months) only contributed to a small proportion of the all-cause mortality in Cyprus, Iceland and Malta. Furthermore, the COVID-19 mortality burden was substantially lower than mortality from common NCDs and injuries (with some exceptions). Of note, individuals with NCDs who had COVID-19 were more likely to experience severe infection, leading to higher morbidity and mortality.24 However, it appeared that the burden of COVID-19 mortality did not exceed the typical annual NCDs burden. This highlights the importance of implementing a syndemic approach, where healthcare systems and policies target both COVID-19 and NCDs simultaneously.25

A number of limitations need to be acknowledged for this study. COVID-19 data and analyses were limited to the available data from online sources, such as dashboards, platforms and other ministerial sites. Mortality data identifying individuals dying ‘with’ COVID-19 as opposed to dying ‘due to’ COVID-19 were available for Cyprus, but not for Iceland and Malta. Furthermore, it is expected that a proportion of COVID-19 mortality has been unreported, as individuals may die without officially being identified as COVID-19 positive. This may impact the analyses and conclusions of this study. Another limitation is the lack of data on confounding factors that might have had an impact on mortality rates. All-cause mortality, mortality attributed to NCDs and YLLs were reported for the year 2019, while the COVID-19 mortality and YLLs were calculated based on a period of 8 months. These comparisons provide a general overview of the effect of COVID-19 within the study period. However, conclusive comparisons could not be achieved, especially as the pandemic is ongoing and variables, including the rate of spread, restriction measures and epidemiological data, rapidly change.

Conclusion

The spread of the COVID-19 pandemic exhibits no boundaries and has affected all countries across the world, including the small islands of Cyprus, Iceland and Malta. The present study highlights that small geographical and population sizes, along with similar restrictive public health measures, did not have an advantage against the viral spread and mortality rate, especially during the second wave in Malta. Population density, an ageing population and social behaviours may play a role in the burden of COVID-19. However, the COVID-19 burden appeared to have less impact than common NCDs and injuries on the population. It is therefore recommended that a country-specific syndemic approach should be implemented to mitigate the local spread of COVID-19, taking into account population characteristics, behaviours and other pre-existing epidemics.

Author statements

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms Margarita Kyriakou, Press Officer of the Ministry of Health, for the provision and validation of the provided data for Cyprus.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Funding

None declared.

Competing interests

None declared.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.03.025.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Cuschieri S., Pallari E., Hatziyiann A., Sigurvinsdottir R., Sigfusdottir I.D., Sigurðardóttir Á.K. Dealing with COVID-19 in small European island states: Cyprus, Iceland and Malta. Early Hum Dev. 2020 Nov 12:105261. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105261. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33213965 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 22]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) Estimating mortality from COVID-19. Sci Brief. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Health Observatory data repository . World Health Organization; 2018. Life tables by country.https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.LT62060?lang=en [Internet]. World Health Organization (WHO) [cited 2020 Dec 12]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) 2019. Global health data exchange. Seattle. [Google Scholar]

- 5.University of Cyprus . University of Cyprus Research and Innovation Center of Excellence; 2020. COVID-19 spread in cyprus.https://covid19.ucy.ac.cy/ [Internet] [cited 2020 Sep 22]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Directorate of Health . 2020. The department of civil protection and emergency management. COVID-19 in Iceland.https://www.covid.is/data [Internet] [cited 2020 Sep 23]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.COVID-19 Public Health Response Team - Ministry for Health . 2020. COVID-19 data management system. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuschieri S., Balzan M., Gauci C., Aguis S., Grech V. Mass events trigger Malta's second peak after initial successful pandemic suppression. J Community Health. 2020 Sep 16:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00925-6. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10900-020-00925-6 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 17]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Financial Mirror . Financial Mirror; 2020. COVID19: 35 people test positive at Limassol nursing home - Financial Mirror.https://www.financialmirror.com/2020/11/02/covid19-35-people-test-positive-at-limassol-nursing-home/ [Internet] [cited 2020 Dec 11]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hafstao V. Iceland Monitor; 2020. Cluster of COVID-19 infections puts landspítali on high alert - Iceland Monitor.https://icelandmonitor.mbl.is/news/news/2020/10/26/cluster_of_covid_19_infections_puts_landspitali_on_/ [Internet] [cited 2020 Dec 30]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vos T., Lim S.S., Abbafati C., Abbas K.M., Abbasi M., Abbasifard M., et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020 Oct 17;396(10258):1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30925-9/fulltext [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 22]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Remuzzi A., Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet (London, England) 2020 Apr 11;395(10231):1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32178769 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 25]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nurchis M.C., Pascucci D., Sapienza M., Villani L., D'Ambrosio F., Castrini F., et al. Impact of the burden of COVID-19 in Italy: results of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and productivity loss. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12) doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124233. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32545827 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 18]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flynn D., Moloney E., Bhattarai N., Scott J., Breckons M., Avery L., et al. COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom. Health Policy Technol. 2020 Dec 1;9(4):673–691. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.003. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211883720300757 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 14]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuschieri S. COVID-19 panic, solidarity and equity—the Malta exemplary experience. J Public Health (Bangkok) 2020 May 30:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s10389-020-01308-w. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10389-020-01308-w [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 3]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Islam N., Khunti K., Dambha-Miller H., Kawachi I., Marmot M. COVID-19 mortality: a complex interplay of sex, gender and ethnicity. Eur J Public Health. 2020 Oct 1;30(5):847–848. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa150. https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/article/30/5/847/5879989 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 10]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang S.-J., Jung S.I. Age-related morbidity and mortality among patients with COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2020 Jun 1;52(2):154. doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.2.154. https://icjournal.org/DOIx.php?id=10.3947/ic.2020.52.2.154 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 14]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuschieri S., Falzon C., Janulova L., Aguis S., Busuttil W., Psaila N., et al. Malta's only acute public hospital service during COVID-19: a diary of events from the first wave to transition phase. Int J Qual Health Care. 2021;33(1) doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa138. mzaa138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuschieri S., Pallari E., Terzic N., Alkerwi A., Sigurðardóttir Á.K. Mapping the burden of diabetes in five small countries in Europe and setting the agenda for health policy and strategic action. Health Res Policy Sys. 2021;19:43. doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00665-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Signorelli C, Odone A. Age-specific COVID-19 case-fatality rate: no evidence of changes over time. Int J Public Health. [cited 2020 Dec 14];65:1435–6. Available from: 10.1007/s00038-020-01486-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) IHME, University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 2019. Malta profile.http://www.healthdata.org/malta [Internet] [cited 2020 Feb 15]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Larochelambert Q., Marc A., Antero J., Le Bourg E., Toussaint J.-F. Covid-19 mortality: a matter of vulnerability among nations facing limited margins of adaptation. Front Public Health. 2020 Nov 19;8:782. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.604339. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.604339/full [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 14]. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 2020. Health at a glance: Europe 2020 state of health in the EU cycle. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Available from: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuschieri S., Grech V. At risk population for COVID-19: Multimorbidity characteristics of European Small Island State. Public Health. 2021;192:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horton R. Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. Lancet. 2020 Sep 26;396(10255):874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32979964 (London, England) [Internet] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.