Abstract

Background

The clinical characteristics and treatment of patients who tested positive for COVID-19 after recovery remained elusive. Effective antiviral therapy is important for tackling these patients. We assessed the efficacy and safety of favipiravir for treating these patients.

Methods

This is a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial in SARS-CoV-2 RNA re-positive patients. Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either favipiravir, in addition to standard care, or standard care alone. The primary outcome was time to achieve a consecutive twice (at intervals of more than 24 h) negative RT-PCR result for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in nasopharyngeal swab and sputum sample.

Results

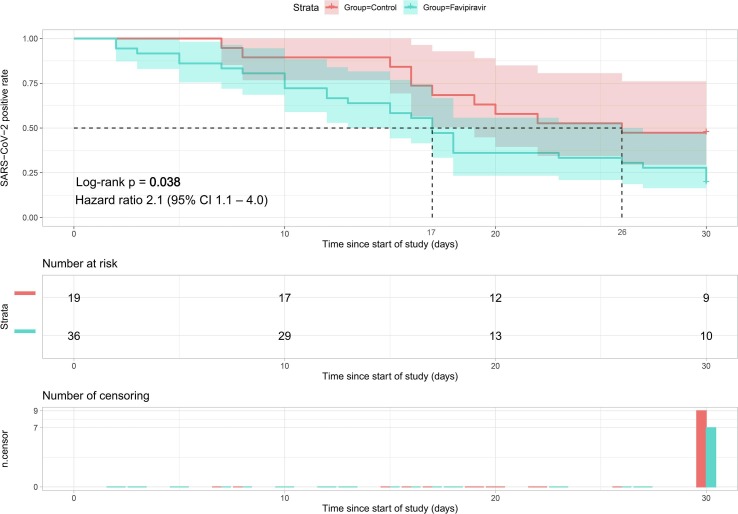

Between March 27 and May 9, 2020, 55 patients underwent randomization; 36 were assigned to the favipiravir group and 19 were assigned to the control group. Favipiravir group had a significantly shorter time from start of study treatment to negative nasopharyngeal swab and sputum than control group (median 17 vs. 26 days); hazard ratio 2.1 (95% CI [1.1–4.0], p = 0.038). The proportion of virus shedding in favipiravir group was higher than control group (80.6% [29/36] vs. 52.6% [10/19], p = 0.030, respectively). C-reactive protein decreased significantly after treatment in the favipiravir group (p = 0.016). The adverse events were generally mild and self-limiting.

Conclusion

Favipiravir was safe and superior to control in shortening the duration of viral shedding in SARS-CoV-2 RNA recurrent positive after discharge. However, a larger scale and randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial is required to confirm our conclusion.

Keywords: Favipiravir, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Recurrent positive

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; SD, standard deviation; ALB, albumin; TBIL, total bilirubin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CK, creatine kinase, CK-MB, creatine kinase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, glutamyl transpeptidase; Cr, creatinine; UA, uric acid

1. Introduction

At the end of 2019, a new coronavirus named SARS-CoV-2, has caused an international outbreak of respiratory illness termed COVID-19 [1]. By December 24, 2020, COVID-19 had infected more than 70 million people and killed about 1.7 million people worldwide [2]. According to the discharge criteria in China's COVID-19 prevention and treatment guidelines [3], more and more COVID-19 patients were discharged from hospital and received regular follow-up observation. Nevertheless, it has been reported that SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been re-detected in some recovered patients [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]. Unfortunately, the mechanism of recurrent positive of SARS-CoV-2 was not clear at present.

Favipiravir is a new broad-spectrum antiviral drug, which targets RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. On February 13, 2020, favipiravir tablets were approved by China FDA (batch number: 2020L00005) for COVID-19 's clinical trial. Favipiravir has a wide range of antiviral effects, including influenza A and B, viral haemorrhagic fever, etc. [9]. In addition, a retrospective study of Ebola virus disease showed that the overall survival rate in the favipiravir group was higher than that in the control group (56.4% [22/39] vs35.3% [30/85], p = 0.027) [10]. Experiments on favipiravir showed that it had anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity in vitro, although higher concentrations were required compared with chloroquine or remdesivir [11]. An open-label non-randomized clinical trial has shown that favipiravir can shorten the time of SARS-CoV-2 clearance compared with lopinavir/ritonavir (median 4 day [IQR 2.5–9] vs. 11 day [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13] P < 0.001). The improvement rate of chest imaging in the favipiravir group was significantly better than that of control group (91.43% vs. 62.22%, P = 0.004) [12].

We designed this clinical trial to verify the efficacy and safety of favipiravir in SARS-CoV-2 RNA recurrent positive after discharge.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and patients

In this multicenter, randomized controlled trial, we screened patients who tested re-positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA after discharge from 5 hospitals in mainland China. The discharge of COVID-19 patients should meet the following criteria [3]: ① Body temperature returned to normal for at least 3 days. ② Respiratory symptoms significantly improved. ③ Pulmonary imaging showed that acute exudative lesions were significantly absorbed and improved. ④ The SARS-CoV-2 RNA test of respiratory tract samples was negative for two consecutive times (the sampling time was at least 1 day). The trial was done in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization–Good Clinical Practice guidelines. This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital and all other participating hospital (Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital, Ezhou Central Hospital, The Third People’s Hospital of Shenzhen, The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College and Wuxi Fifth People's Hospital). All patients signed the informed consent form. The complete protocol for the clinical trial has been registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04333589) and also available on Trials [13].

From March 27 to May 9, 2020, we screened a total of 67 SARS-CoV-2 RNA recurrent positive after discharge. All patients enrolled in the favipiravir group and the control group should meet the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria include: ① Over 18 years of age, both male and female; ② After the first diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19, the SARS-CoV-2 RNA test of respiratory specimens such as sputum or nasopharyngeal swabs, has been negative for two consecutive times (sampling time interval of at least 24 h), in accordance with China COVID-19 guidelines (7th Edition), discharged; ③ During screening visit (follow-up after discharge), the SARS-CoV-2 RNA test of COVID-19 is positive in any one of the following samples: sputum, nasopharyngeal swabs, blood, feces or other specimens. Regardless of whether or not they had symptoms and the severity of symptoms; ④ Volunteer to participate in the research and sign the Informed Consent Form. Key exclusion criteria included: ① Allergic to favipiravir; ② Pregnant or lactating women; ③The researchers considered the patient was not suitable to participate in this clinical trial.

2.2. Randomization and masking

Patients were randomly assigned to either the favipiravir group or the control group, in the ratio of 2:1, by simple randomization with no stratification. Randomized treatment was open-label. Patients were assigned to a serial number by the study coordinator. Each serial number was linked to a computer-generated randomization list assigning the antiviral treatment regimens. The study medications were dispensed by the hospital pharmacy and then to the patients by the medical ward nurses.

2.3. Procedures

The use of favipiravir was 1600 mg (bid) on the first day, and 600 mg (bid) from the 2nd day to the 7th day, orally. After that, the researchers decided whether to continue favipiravir according to the patient's condition, but no more than 14 days of treatment. Patients assigned to the control group received drugs other than favipiravir and treatment according to the needs of the disease.

All enrolled patients had to have laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by RT-PCR in the nasopharyngeal swab. In order to avoid being mistakenly taken as saliva when taking sputum samples, sputum samples were taken from the respiratory tract samples after deep cough.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was time to achieve a consecutive twice (at intervals of more than 24 h) negative RT-PCR result for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in nasopharyngeal swab and sputum sample. The secondary outcomes were the changes of blood routine and CRP (C-reactive protein); the count and proportion of T lymphocyte subsets in peripheral blood and the changes of cytokines. In addition, we also analyzed the relationship between the antibody titer and the SARS-CoV-2 RNA re-negative time. The safety end point is the frequency of adverse events in each group.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as the median and range (or mean with standard deviation). Categorical variables were demonstrated with number and percentage. The t test (paired and non-paired) or Kruskal-Wallis analysis were used to compare continuous variables, and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were used to categorical variables. SARS-CoV-2 positive rate between favipiravir group and control group curves were analyzed by log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. The patient's sample size was calculated based on previous studies by Hung and colleagues [14]. Our hypothesis was that there may be a 5-day difference in the duration of SARS-CoV-2 between the favipiravir group and the control group, which meant that the sample size of a total of 48 patients (32 in favipiravir group and 16 in control group) was needed (with a power of 90% for a significance level of 5% with a two-tailed test). The p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was conducted with R (version 3.6.2).

3. Result

3.1. Patients and baseline analysis

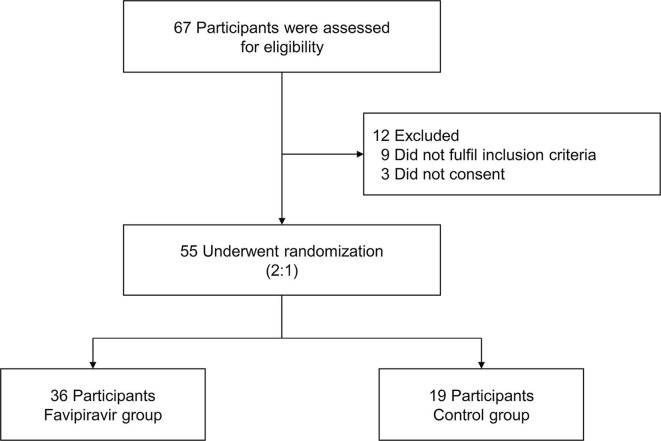

From March 27 to May 9, 2020, 67 patients were screened, of whom 55 (36 in favipiravir group and 19 in control group) were eligible (Fig. 1 ). The median age of study patients was 60 years (ranging from 28 to 79); sex distribution was 16 (44.4%) men versus 20 (55.6%) women in the favipiravir group and 10 (52.6%) versus 9 (47.4%) in the control group.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study design.

There was no significant difference in patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics before treatment between two groups (Table 1 ). The moderate type was dominant in both the favipiravir group and the control group (94.4% [34/36] vs. 89.5% [17/19]) according to the clinical classification criteria (Table S1). Most patients were found to be SARS-CoV-2 RNA re-positive during centralized isolation (65.5% [36/55]). The “centralized isolation” shelter was the “Fangcang shelter hospitals” which were temporarily built in China during COVID-19 [15]. More than half of the patients (56.4% [31/55]) have at least one chronic disease or malignant tumor, and the most common of which is hypertension (30.9% [17/55]). The vast majority of patients (74.5% [41/55]) had used at least one antiviral drug during last hospitalization, the most common of which was Umifenovir (61.8% [34/55]). Only two patients (one patient in each group) have ever used glucocorticoid. The duration of the first SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive was 28.2 ± 14.8 days (favipiravir group and control group were 28.3 ± 16.6 and 27.8 ± 11.3 days, respectively), of which the shortest was 5 days and the longest was 86 days. The time from the first SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative (two consecutive times) to this re-positive was 20.6 ± 17.4 days (favipiravir group and control group were 22.2 ± 19.3 and 17.9 ± 13.9 days, respectively).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the first SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive*

| Overall (n = 55) |

Favipiravir (n = 36) |

Control (n = 19) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.836 | |||

| Female | 30 (54.5%) | 20 (55.6%) | 10 (52.6%) | |

| Male | 25 (45.5%) | 16 (44.4%) | 9 (47.4%) | |

| Age (year) | 55.7 (13.6) | 55.8 (14.2) | 55.5 (12.6) | 0.949 |

| BMI (kg/mb) | 23.3 (2.61) | 22.8 (2.44) | 24.2 (2.74) | 0.067 |

| Clinical typea | 0.169 | |||

| Mild | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Moderate | 51 (92.7%) | 34 (94.4%) | 17 (89.5%) | |

| Severe | 3 (5.5%) | 1 (2.8%) | 2 (10.5%) | |

| Positive Spot | 0.866 | |||

| Home Isolation | 9 (16.4%) | 6 (16.7%) | 3 (15.8%) | |

| Centralized Isolation | 36 (65.5%) | 23 (63.9%) | 13 (68.4%) | |

| Hospital | 10 (18.2%) | 7 (19.4%) | 3 (15.8%) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 17 (30.9%) | 8 (22.2%) | 9 (47.4%) | 0.055 |

| Diabetes | 8 (14.5%) | 4 (11.1%) | 4 (21.1%) | 0.426 |

| CHD | 4 (7.3%) | 2 (5.6%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0.602 |

| Malignant tumor | 4 (7.3%) | 3 (8.3%) | 1 (5.3%) | >0.999 |

| CLDb | 7 (12.7%) | 4 (11.1%) | 3 (15.8%) | 0.682 |

| Chronic Disease or Tumorc | 31 (56.4%) | 18 (50.0%) | 13 (68.4%) | 0.190 |

| Treatment history | ||||

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir | 9 (16.4%) | 7 (19.4%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0.163 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 3 (5.5%) | 2 (5.6%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0.714 |

| Remdesivir | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | – |

| Oseltamivir | 7 (12.7%) | 4 (11.1%) | 3 (15.8%) | 0.939 |

| Umifenovir | 34 (61.8%) | 20 (55.6%) | 14 (73.7%) | 0.403 |

| Favipiravir | 6 (10.9%) | 5 (13.9%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0.304 |

| Antibiotic | 21 (38.2%) | 13 (36.1%) | 8 (42.1%) | 0.928 |

| Glucocorticoid | 2 (3.6%) | 1 (2.8%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0.922 |

| SPDd | ||||

| Mean (Sd) day | 28.2 (14.8) | 28.3 (16.6) | 27.8 (11.3) | 0.911 |

| Median [Min, Max] day | 27.0 [5.00, 86.0] | 27.5 [5.00, 86.0] | 26.0 [10.0, 49.0] | 0.745 |

| Re-Positive Intervale | ||||

| Mean (Sd) day | 20.6 (17.4) | 22.2 (19.3) | 17.9 (13.9) | 0.405 |

| Median [Min, Max] day | 15.0 [1.00, 71.0] | 17.0 [1.00, 71.0] | 12.0 [3.00, 59.0] | 0.531 |

NOTE: *The values shown are based on available data.

SPD, SARS-CoV-2 RNA Positive Duration; CHD, Coronary heart disease; CLD, Chronic Liver Disease

Clinical classification was based on China COVID-19 guidelines (7th Edition).

CLD means chronic liver disease. It's defined as liver necrosis and inflammation caused by different causes and lasting at least 6 months, including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, steatohepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, cirrhosis, etc.

With a history of at least one chronic disease or malignant tumor.

The “SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive duration” refers to the time from the first positive detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA to two consecutive nasopharyngeal swabs negative. Two patients were unable to get “SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive duration” data.

The “Re-Positive Interval” refers to the time from two consecutive nasopharyngeal swabs negative to this recurrent positive interval. Six patients were unable to get “Re-Positive Interval” data.

All the patients’ vital signs were stable (not shown). Most of the patients (69.1% [38/55]) were without clinical symptoms. Cough was the most common among these symptomatic patients, accounting for only 16.4% (9/55). Other clinical symptoms such as fever, diarrhea and chest tightness were shown in Table 2 . As with the first COVID-19 onset, the clinical classification was mainly the moderate type, regardless of the favipiravir group or the control group. The white blood cell count in these re-positive patients were in the normal range (reference values were shown in Table S2). One patient in the favipiravir group had chronic lymphoblastic leukemia, so his blood routine was quite different from the other patients. The median lymphocyte count (1.74 vs. 1.88 × 109/L) and percentage (28.6% vs. 31.8%) were at the lower limit of the normal value in both the favipiravir group and the control group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and laboratory examination of this SARS-CoV-2 RNA recurrent positive*

| Overall (n = 55) | Favipiravir (n = 36) | Control (n = 19) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical symptom | ||||

| Asymptom | 38 (69.1%) | 27 (75.0%) | 11 (57.9%) | 0.192 |

| Cough | 9 (16.4%) | 3 (8.3%) | 6 (31.6%) | 0.051 |

| Palpitation | 3 (5.5%) | 1 (2.8%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0.272 |

| Chest tightness | 3 (5.5%) | 1 (2.8%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0.272 |

| Diarrhea | 3 (5.5%) | 1 (2.8%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0.272 |

| Fever | 3 (5.5%) | 3 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.544 |

| Clinical type | >0.999 | |||

| Mild | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Moderate | 53 (96.4%) | 34 (94.4%) | 19 (100%) | |

| Severe | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Routine blood test | ||||

| WBC (10^9/L) Mean (SD) | 5.9 (1.6) | 5.9 (1.8) | 5.7 (1.4) | 0.648 |

| Neutrophil count (10^9/L) Mean (SD) | 3.5 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.1) | 0.621 |

| Neutrophil percentage (%) Mean (SD) | 58.6 (7.3) | 58.8 (7.6) | 58.3 (6.9) | 0.832 |

| Lymphocyte count (10^9/L) Mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.4) | 0.746 |

| Lymphocyte percentage (%) Mean (SD) | 30.1 (7.2) | 29.6 (7.3) | 30.9 (7.0) | 0.553 |

| Monocyte count (10^9/L) Mean (SD) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.226 |

| Monocyte percentage (%) Mean (SD) | 7.4 (2.7) | 7.7 (3.1) | 6.9 (1.4) | 0.311 |

| CRP (mg/L) Mean (SD) | 3.3 (7.6) | 4.0 (9.1) | 2.0 (2.8) | 0.350 |

| Blood biochemical test | ||||

| ALB (g/L) Mean (SD) | 43 (3.2) | 42.6 (3.2) | 44 (3.2) | 0.148 |

| TBIL (umol/L) Mean (SD) | 11.2 (5.1) | 11.7 (5.7) | 10 (3.2) | 0.249 |

| ALT (U/L) Mean (SD) | 28.6 (22.2) | 26.3 (21.7) | 33.6 (23) | 0.265 |

| AST (U/L) Mean (SD) | 21.9 (10.7) | 21.6 (11.3) | 22.5 (9.6) | 0.779 |

| LDH (U/L) Mean (SD) | 169.8 (35.7) | 166.3 (29.8) | 176.8 (45.7) | 0.324 |

| CK (U/L) Mean (SD) | 69.8 (36.1) | 71.8 (39.7) | 65.7 (28) | 0.582 |

| CK-MB (U/L) Mean (SD) | 11.4 (4.6) | 11 (4.2) | 12.1 (5.4) | 0.423 |

| ALP (U/L) Mean (SD) | 65 (24) | 63.9 (26.1) | 67.3 (19.2) | 0.639 |

| GGT (U/L) Mean (SD) | 36.4 (27.3) | 36.9 (28.2) | 35.2 (26) | 0.827 |

| Cr (umol/L) Mean (SD) | 61.3 (19.7) | 61.7 (21.7) | 60.4 (15.1) | 0.824 |

| UA (umol/L) Mean (SD) | 361.1 (130.1) | 370.6 (132.9) | 342.8 (126.6) | 0.493 |

NOTE: *The values shown are based on available data.

WBC white blood cell; SD standard deviation; ALB albumin; TBIL total bilirubin; ALT alanine aminotransferase; AST aspartate aminotransferase; LDH lactate dehydrogenase; CK creatine kinase; CK-MB creatine kinase; ALP alkaline phosphatase; GGT glutamyl transpeptidase; Cr creatinine; UA uric acid. One patient in the favipiravir group was chronic lymphocytic leukemia, with a lymphocyte percentage as high as 82.8%, so the patient was excluded from the analysis.

3.2. Primary outcome

For the primary endpoint of time from start of study treatment to negative nasopharyngeal swab and sputum, the favipiravir group had a significantly shorter median time (17 days) than the control group (26 days; hazard ratio 2.1 [95% CI 1.1–4.0], p = 0.038; Fig. 2 ). At the end of this clinical trial (30 days), the proportion of SARS-CoV-2 RNA PCR turning negative in the favipiravir group was much higher than control group (80.6% [29/36] vs. 52.6% [10/19], p = 0.030, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Time to SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative in the Control-to-Favipiravir Population. The shaded areas represent pointwise 95% confidence intervals.

3.3. Secondary outcomes

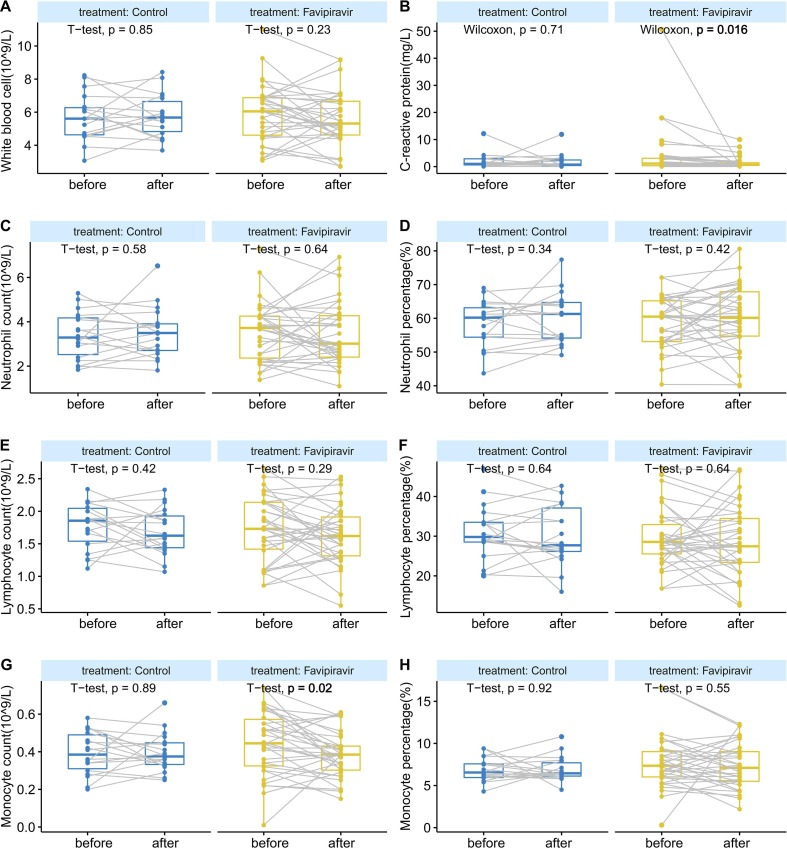

No death was reported in both groups. After treatment, CRP decreased significantly from baseline in favipiravir group (4.0 ± 9.1 to 1.5 ± 2.1 mg/L, p = 0.016, Fig. 3 B), while the control group did not change significantly (2.0 ± 2.8 to 1.8 ± 2.7 mg/L, p = 0.710). In favipiravir group, CRP decreased significantly from baseline in patients with negative RNA after therapy (2.9 ± 4.7 to 1.5 ± 2.3 mg/L, p = 0.005). Monocyte count also showed a significant decrease after therapy in the favipiravir group (0.45 ± 0.17 to 0.38 ± 0.12 × 10^9/L, p = 0.020, Fig. 3G).

Fig. 3.

Changes of blood routine test and C-reactive protein in peripheral blood before and after treatment. (A) White blood cell count (B) C-reactive protein (C) Neutrophil count (D) Neutrophil percentage (E) Lymphocyte count (F) Lymphocyte percentage (G) Monocyte count (H) Monocyte percentage. The horizontal line represents the median value. The difference between before and after treatment were calculated by t-test or Wilcoxon-test.

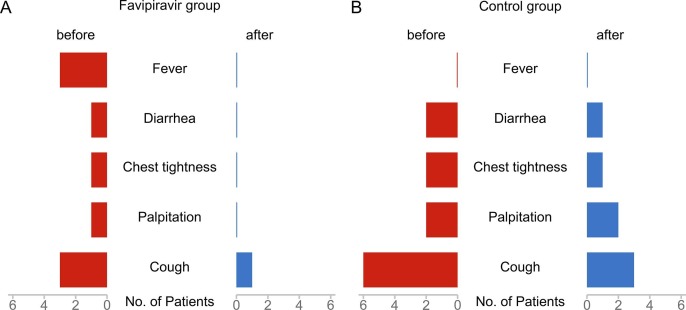

Fig. 4 shows the improvement of clinical symptoms in the favipiravir group and the control group before and after treatment. Before treatment, there seemed to be more clinical symptoms in the control group, but there was no statistical difference between them (Table 1). Fig. 4A shows the clinical symptoms of the favipiravir group. After treatment, almost all the clinical symptoms, including fever, disappeared, and only one patient with cough. In the control group, cough was relieved in only half of the patients(3/6), and other clinical symptoms are shown in Fig. 4B. Because there are few people with clinical symptoms, we only give a simple description.

Fig. 4.

Clinical symptom in favipiravir group and control group. (A) favipiravir group (B) control group.

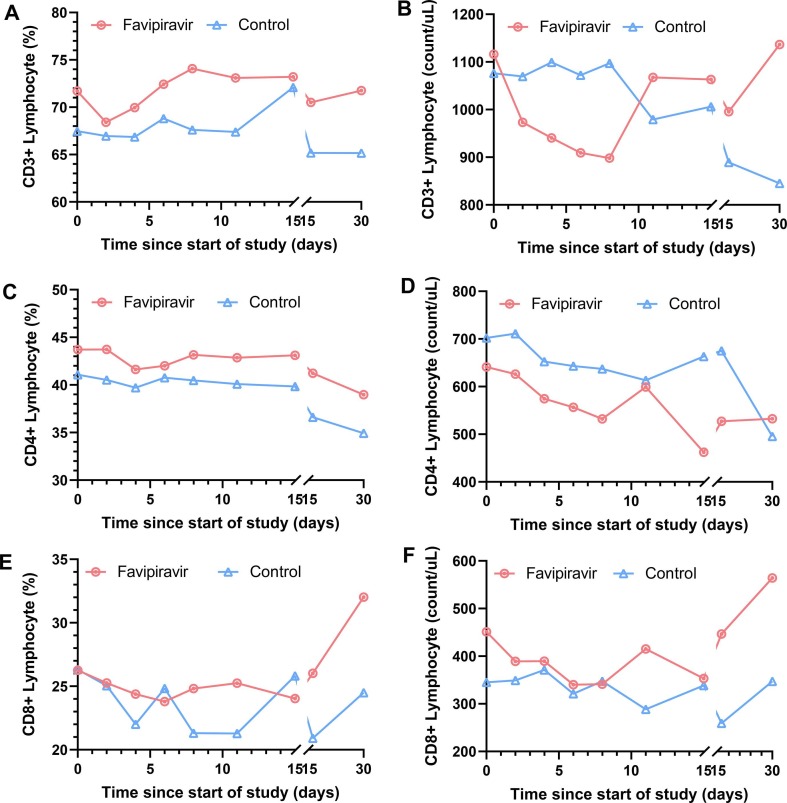

The CD3+ T cell and CD8+ T cell counts decreased within the first 7 days and then increased in the favipiravir group, in contrast a continuous decrease trend in the control group (Fig. 5 B and Fig. 5F). The CD4+ T cell count did not show an upward trend in both the control group and the favipiravir group (Fig. 5D, Table S4). In the favipiravir group, the CD4+ cell count decreased significantly after 15 days of treatment (719.1 ± 226.6 vs. 484.1 ± 177.4 count/uL, p = 0.001), but then gradually increased. In the control group, CD3+ and CD4+ cell counts decreased significantly after 30 days of treatment ([CD3+ T cell: 1159.2 ± 280.7 vs. 778 ± 173.5 count/uL, p = 0.026]; [CD4+ T cell: 672.5 ± 120.2 vs. 505.8 ± 151.4 count/uL, p = 0.047]).

Fig. 5.

Changes of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets (median value) in Favipiravir group and Control group. (A) CD3+ Lymphocyte percentage (B) CD3+ Lymphocyte count (C) CD4+ Lymphocyte percentage (D) CD4+ Lymphocyte count (E) CD8+ Lymphocyte percentage (F) CD8+ Lymphocyte count.

In favipiravir group, IL-8 (mean value 653.7 to 95.3U/L, p = 0.007, Fig. S1F) and TNF-β (mean value 2.8 to 2.2 U/L, p = 0.013, Fig. S1M) had a significant decline after treatment. IL-1β (mean value 2.6 to 1.3 U/L, p = 0.095, Fig. S1A) and IL-5 (mean value 3.3 to 2.2 U/L, p = 0.056, Fig. S1D) also decreased in values although had no statistical difference. In control group, only IL-1β had an obvious reducing compared with its baseline level (mean value 1.9 to 0.9 U/L, p = 0.018, Fig. S1A).

We detected anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in 32 patients (the rest 23 patients refuse to be tested). During the entire study, the IgG antibodies of all tested patients were positive, regardless of whether the SARS-CoV-2 RNA was positive. Meanwhile, only 37.5% (12/32) patients had IgM antibodies positive (reference value was ≤ 10 AU/ml). The median titer of IgM in patients with SARS-CoV-2 RNA negative was slightly higher than those with positive results ([favipiravir group 9.8 vs. 6.4 AU/ml, p = 0.37]; [control group 33.8 vs. 5.6 AU/ml, p = 0.13] Fig. S2A). The titer of IgG showed an opposite trend in both group ([favipiravir group 93.3 vs. 128.7 AU/ml, p = 0.64]; [control group 96.1 vs. 110.2 AU/ml, p = 0.72], Fig. S2B).

3.4. Safety

A total of 19 adverse events occurred in this clinical trial. There were 12 in favipiravir group and 7 in control group. Elevated transaminase (ALT and AST) was the most common in both the favipiravir group and the control group. Hyperuricemia, diarrhea, nausea and other adverse reactions were also reported, as detailed in Table S3. No serious adverse effects occurred in this clinical trial, and the aforementioned adverse reactions were alleviated during subsequent follow-up.

4. Discussion

In this multicenter, randomized clinical trial of patients with SARS-CoV-2 RNA re-positive after discharged, patients who received favipiravir had faster virus clearance than control group. CRP decreased more significantly in favipiravir group. The adverse events were generally mild and self-limiting in favipiravir group.

So far, there have been no randomized controlled trials for recurrent positive after discharged. Our clinical trial shows that favipiravir is effective in patients with SARS-CoV-2 RNA re-positive. An open-label clinical trial showed that favipiravir could shorten the positive duration of the virus compared with lopinavir/ritonavir (median time 4 vs. 11 day, P < 0.001) [12]. The favipiravir arm also showed significant improvement in chest imaging compared with control arm (91.43% versus 62.22%, P = 0.004). However, our median time for RNA negative was 17 days in favipiravir group, which is significantly longer than Cai et al. study. We note that Cai et al.[12], defined RNA negative criteria as the presence of two consecutive negative results with qPCR detection over an interval of 24 h, while we defined as two consecutive respiratory (both nasopharyngeal swab and sputum) virus test negative results. What’s more, our patients are re-positive patients, more than half of the patients are complicated with underlying diseases; this may also be one of the other reasons.

There were many drugs that may be effective against SARS-COV-2, such as remdesivir, lopinavir–ritonavir, Umifenovir, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, ribavirin, interferon-α/γ [16]. Clinical trials failed to show benefits of treatment with chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine [17], [18]. The effect of remdesivir was controversial. Wang et al. study (237 patients) [19] showed remdesivir was not associated with statistical clinical benefits (HR 1.23 [95% CI 0.87–1.75]). However, Beigel et al. (1063 patients) [20] demonstrated that remdesivir had a shorter median recovery time (11 day [95%CI 9–12]), as compared with placebo (15 days [95% CI, 13 to 19)]; RR 1.3 [95% CI, 1.1–1.6] P < 0.001). A triple combination drug study (127 patients) [14] indicated that combination group (interferon β-1b, lopinavir–ritonavir, and ribavirin) had a significantly shorter median time of negative nasopharyngeal swab (7 days [IQR 5–11]) than control group (lopinavir–ritonavir) (12 days [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15]; HR 4.37 [95% CI 1.86–10.24], p = 0.001). A trial of Lopinavir–Ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe COVID-19 showed that there was no significant difference in clinical symptoms (HR 1.31, [95%CI 0.95–1.80]), 28-day mortality (19.2% vs. 25.0%; difference, −5.8 percentage points; 95% CI, −17.3 to 5.7) and 28-day virus clearance (59.3% vs. 57.7%; difference 1.6 [-15.4, 18.6]) between lopinavir–ritonavir groups and control group [21].

The management of discharge COVID-19 patients with recurrent positive SARS-CoV-RNA is challenging [22], [23]. So, we conducted a PubMed search using the following search strategy: (“recurrent positive”[Title/Abstract] OR “re-positive”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“COVID-19″[Title/Abstract] OR ”SARS-CoV-2″[Title/Abstract]). Although there is no direct study about the mechanism of recurrent positive, several related studies have been found. Firstly, there is still live virus in patient. Yao et al. [24] reported an elderly female patient whose nasopharyngeal swab test was negative for three consecutive days, and the clinical symptoms and lung imaging were significantly improved. Just as she was about to be discharged from the hospital, unfortunately, the patient died of cardiac arrest suddenly. After autopsy, SARS-CoV-2 particles was found in the patient's lungs (confirmed by electron microscope and immunohistochemical staining). Secondly, the immune status of the patient. Diao et al. study [25] (including 522 COVID-19 patients and 40 healthy controls) declared that not only the number of T cells in COVID-19 patients decreased, but also the function of T cells was significantly suppressed (increasing PD-1 and Tim-3 expression). At the same time, our clinical data also showed that the specific immune function of recurrent positive patients were decreased. Another possibility is that COVID-19 did recover for the first time, but there was another new infection. Although it is currently believed that neutralizing antibodies in patients have some resistance to COVID-19, which can greatly reduce the risk of secondary infection. But because COVID-19 is a brand-new disease, we know little about it. How much protective effect does the antibody produced by the body have? How long does it last? It is still unknown. Therefore, the possibility of reinfection cannot be ruled out. In addition, there are also several reports that SARS-CoV-2 is mutating [26], [27], [28], and the ability of antibodies produced by previous infection to protect the mutated virus is also unknown. Besides, the biological characteristics of the virus itself, the use of glucocorticoids in the treatment process, sample collection and detection may also be the reasons for the re-positive of SARS-CoV-2 [29].

The majority of patients enrolled in this study without obvious clinical symptoms, while favipiravir only shortened the duration of SARS-CoV-2positive, which seemed to have little clinical significance. However, we did not think so. First, for patients with clinical symptoms, favipiravir did significantly relieve clinical symptoms, and only one patient had a cough at the end of treatment. Second, for non-severe patients, reducing the duration of the SARS-CoV-2 meant shortening the length of stay. Because according to China's COVID-19 discharge criteria [3], SARS-CoV-2 RNA test positive cannot discharge. We know that long-term hospitalization may cause psychological burdens to both patients, their families and medical staff [30]. For patients and their families, the psychological problems caused by long-term hospitalization or persistent SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive are momentous. Pan et al.[31] research (including 1517 participants) showed that COVID-19 patients required close monitoring in clinical practice. In addition, a survey of 14,825 health-care workers by Song et al [32] showed that during the epidemic of COVID-19, the prevalence rates of depressive symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder were 25.2% and 9.1%, respectively. Third, from the perspective of health economics, it is also meaningful to reduce the SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive. It was reported that the average cost of COVID-19 patients in China is ¥17000 (about $2600) [33]. If the duration of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA can be reduced, thus reducing the length of hospitalization of inpatients; this is bound to help reduce the health economic burden. In short, it is of great significance for patients without clinical symptoms to use favipiravir to reduce the duration of the virus.

We also have several unavoidable limitations in this clinical trial. First of all, due to the limited number of recurrent positive patients, the sample size of this study needs to be expanded. Secondly, the trial was not blinded, so it is possible that knowledge of the treatment assignment might have influenced clinical decision-making. Thirdly, we followed up all the patients for only 30 days, and it is not clear whether these patients will return to positive again. Fourth, because the EDC system records only the qualitative data of PCR results, we have not been able to obtain the Ct value of the dynamic changes of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in patients. Fifth, the presence of few symptomatic patients in this study, and only mild symptoms, prevents us from demonstrating a clear clinical benefit of favipiravir. Sixth, hospital admission is mandatory in PCR positive patients in China, and discharge is not allowed meanwhile PCR is still positive, but these measures are not followed worldwide, so the benefits of treatment may not be widespread in other settings.

5. Conclusion

Favipiravir can significantly short SARS-CoV-2 positive time of patients whose RNA re-positive after discharge; increase the chance of virus negative conversion and have better safety. However, a larger scale and randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial is required to fully assess the efficacy and safety of favipiravir in patients with SARS-CoV-2 recurrent positive after discharge.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital and all other participating hospital (Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital, Ezhou Central Hospital, The Third People’s Hospital of Shenzhen, The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical College and Wuxi Fifth People's Hospital) and has been registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04333589). All patients signed the informed consent form.

Funding

This study was supported by Chinese COVID-19 scientific research emergency project (grant numbers 2020YFC0844100, 2020YFC0846800 and 2020ZYLCYJ05-14); China Mega-Project for Infectious Diseases (grant numbers 2017ZX10203202) and China Mega-Project for Innovative Drugs (grant numbers 2016ZX09101065).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients and their families who participated in this study, as well as all the health care workers and other staff who participated in the fight against COVID-19. In addition, we thank Ashermed Pharmaceutical Technology Co.Ltd for its participation in data checking and collation.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107702.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y., et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. New Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.http://2019ncov.chinacdc.cn/2019-nCoV/global.html (accessed December 24, 2020).

- 3.Diagnosis and treatment protocol for novel coronavirus pneumonia (seventh edition). http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-03/04/5486705/files/ae61004f930d47598711a0d4cbf874a9.pdf (accessed July 10, 2020).

- 4.L Lan, D Xu, G Ye, C Xia, S Wang, Y Li et al. Positive RT-PCR Test Results in Patients Recovered From COVID-19. JAMA. 2020 Apr 21;323(15):1502-1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Mei Q., Li J., Du R., Yuan X., Li M., Li J. Assessment of patients who tested positive for COVID-19 after recovery. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(9):1004–1005. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qu Y.M., Kang E.M., Cong H.Y. Positive result of Sars-Cov-2 in sputum from a cured patient with COVID-19. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling Y., Xu S.B., Lin Y.X., Tian D., Zhu Z.Q., Dai F.H., et al. Persistence and clearance of viral RNA in 2019 novel coronavirus disease rehabilitation patients. Chin. Med. J. 2020;133(9):1039–1043. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.J An, X Liao, T Xiao, S Qian, J Yuan, H Ye, et al., Clinical characteristics of the recovered COVID-19 patients with re-detectable positive RNA test, medRxiv (2020) 2020.03.26.20044222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Coomes E.A, HaghbayanFavipiravir H. an antiviral for COVID-19? J. Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2020;75(7):2013–2014. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bai C.Q., Mu J.S., Kargbo D., Song Y.B., Niu W.K., Nie W.M., et al. Clinical and Virological Characteristics of Ebola Virus Disease Patients Treated With Favipiravir (T-705)-Sierra Leone, 2014. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63(10):1288–1294. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai Q., Yang M., Liu D., Chen J., Shu D., Xia J., et al. Experimental Treatment with Favipiravir for COVID-19: An Open-Label Control Study. Engineering. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J., Zhang C., Wu Z., Wang G., Zhao H. The Mechanism and Clinical Outcome of patients with Corona Virus Disease 2019 Whose Nucleic Acid Test has changed from negative to positive, and the therapeutic efficacy of Favipiravir: A structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):488. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04430-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hung I., Lung K., Tso E., Liu R., Chung T., Chu M., et al. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1695–1704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen S., Zhang Z., Yang J., Wang J., Zhai X., Bärnighausen T., et al. Fangcang shelter hospitals: a novel concept for responding to public health emergencies. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1305–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vijayvargiya P., Esquer Garrigos Z., Castillo Almeida N., Gurram P., Stevens R., Razonable R. Treatment Considerations for COVID-19: A Critical Review of the Evidence (or Lack Thereof) Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020;95(7):1454–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geleris J., Sun Y., Platt J., Zucker J., Baldwin M., Hripcsak G., et al. Observational Study of Hydroxychloroquine in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. New Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(25):2411–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang W., Cao Z., Han M., Wang Z., Chen J., Sun W., et al. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with mainly mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019: open label, randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y., Zhang D., Du G., Du R., Zhao J., Jin Y., et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet (London, England) 2020;395(10236):1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beigel J., Tomashek K., Dodd L., Mehta A., Zingman B., Kalil A., et al. Remdesivir for the Treatment of Covid-19 - Preliminary Report. New Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2022236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cao B., Wang Y., Wen D., Liu W., Wang J., Fan G., et al. A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(19):1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong K., Cao W., Liu Z., Lin L., Zhou X., Zeng Y., et al. Prolonged presence of viral nucleic acid in clinically recovered COVID-19 patients was not associated with effective infectiousness. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 2020;9(1):2315–2321. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1827983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang C., Jiang M., Wang X., Tang X., Fang S., Li H., et al. Viral RNA level, serum antibody responses, and transmission risk in recovered COVID-19 patients with recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA test results: a population-based observational cohort study. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 2020;9(1):2368–2378. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1837018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao X.H., He Z.C., Li T.Y., Zhang H.R., Wang Y., Mou H., et al. Pathological evidence for residual SARS-CoV-2 in pulmonary tissues of a ready-for-discharge patient. Cell Res. 2020;30(6):541–543. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0318-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diao B., Wang C., Tan Y., Chen X., Liu Y., Ning L., et al. Reduction and Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Front. Immunol. 2020;11:827. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grubaugh N.D., Hanage W.P., Rasmussen A.L. Making sense of mutation: what D614G means for the COVID-19 pandemic remains unclear. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korber B., Fischer W.M., Gnanakaran S., Yoon H., Theiler J., Abfalterer W., et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang X., Wu C., Li X., Song Y., Yao X., Wu X., et al. On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020;7(6):1012–1023. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou L., Liu K., Liu H. Cause analysis and treatment strategies of “recurrence” with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) patients after discharge from hospital (in Chinese) Chin. J. Tuberculosis Respiratory Dis. 2020;43(4):281–284. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20200229-00219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The intersection of COVID-19 and mental health. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1473309920307970 (accessed February 14, 2021).

- 31.Pan K.Y., Kok A.A.L., Eikelenboom M., Horsfall M., Jörg F., Luteijn R.A., et al. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with and without depressive, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorders: a longitudinal study of three Dutch case-control cohorts. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(2):121–129. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30491-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song X., Fu W., Liu X., Luo Z., Wang R., Zhou N., et al. Mental health status of medical staff in emergency departments during the Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;88:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.https://news.sina.com.cn/c/2020-03-30/doc-iimxyqwa4112916.shtml (accessed February 24, 2021).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.