Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic and degenerative joint disease, which causes stiffness, pain, and decreased function. At the early stage of OA, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are considered the first-line treatment. However, the efficacy and utility of available drug therapies are limited. We aim to use bioinformatics to identify potential genes and drugs associated with OA.

Methods

The genes related to OA and NSAIDs therapy were determined by text mining. Then, the common genes were performed for GO, KEGG pathway analysis, and protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis. Using the MCODE plugin-obtained hub genes, the expression levels of hub genes were verified using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). The confirmed genes were queried in the Drug Gene Interaction Database to determine potential genes and drugs.

Results

The qRT-PCR result showed that the expression level of 15 genes was significantly increased in OA samples. Finally, eight potential genes were targetable to a total of 53 drugs, twenty-one of which have been employed to treat OA and 32 drugs have not yet been used in OA.

Conclusions

The 15 genes (including PTGS2, NLRP3, MMP9, IL1RN, CCL2, TNF, IL10, CD40, IL6, NGF, TP53, RELA, BCL2L1, VEGFA, and NOTCH1) and 32 drugs, which have not been used in OA but approved by the FDA for other diseases, could be potential genes and drugs, respectively, to improve OA treatment. Additionally, those methods provided tremendous opportunities to facilitate drug repositioning efforts and study novel target pharmacology in the pharmaceutical industry.

1. Introduction

OA is a chronic and degenerative joint disease that occurs commonly in the elderly, and the main concomitant symptoms were cartilage loss, subchondral bone sclerosis, synovitis, and pain [1, 2]. The incidence of OA is increasing around the world due to the aging population and the growing number of obese individuals [3]. According to the statistics, the incidence of OA can reach nearly half of people over age 65 and 80% of those over age 80 [4].

There are different management methods between the end stage and early stage for OA. Traditionally, the treatments of end-stage OA for improving function and relieving pain have been joint operation [5], which may have long-term problems and potential complications, such as pain, infection, hemorrhage, and arthrofibrosis [6]. Therefore, early treatment is particularly important. Comprehensive clinical practice guidelines by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons held that NSAIDs were appropriate for all nonsurgical treatment OA patients [7]. Using the drug of NSAIDs in the treatment of OA has also been approved by the American College of Rheumatology and other academic institutions [8].

NSAIDs include traditional NSAIDs and new COX-2 inhibitors; the former blocks COX-1 and COX-2 but the new one only blocks the COX-2 enzyme. The formation of prostaglandinH2 (PGH2) by the metabolic process of the COX enzyme is metabolized by prostaglandin E (PGE) synthase into PGE2, which is one of the significant inflammation mediator [9]. COX-1, found in most tissues, is encoded by prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 (PTGS1) and COX-2, induced by various cytokines and growth factors, is encoded by prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) [10]. COX-1 NSAIDs are associated with more gastrointestinal side effects than COX-2 [11], but likely have a lower rate of cardiovascular events [12]. In clinical practice, diclofenac, one kind of NSAIDs (inhibiting COX-1 and COX-2), is used as the most effective for OA treatment [4] and increases the rating of the risk of a cardiovascular event by fourfold, stroke by threefold, and all-cause death by twofold [13]. A long-term use of Ibuprofen (also inhibiting COX-1 and COX-2) shows more than three times the incidence of stroke complications compared with placebo [13]. Although there are significant limitations and health risks, approximately 65% of patients are provided oral NSAIDs to control OA [14]. After consuming NSAIDs chronically, most patients still report persistent pain and disability, and more than half will receive a prescription to stop using within one year [15]. Given all that, the securities of NSAIDs are problems that have to be paid attention to. It is still limited to research into drug therapy, and we need further studies to fill the vacancies in the development of novel therapeutic drugs.

Discovering new drug therapies is typically a 7–12 years process. With the development of computer technology and biotechnology, the article type of text mining for new drugs is becoming more common worldwide. Besides, abundant clinical trials and investment of billions of dollars are recommended but what we got are unpredictable returns on investment [16]. However, it is a less costly and possibly quicker alternative that the existing drugs are beyond their original intent to treat a novel situation [17]. Text mining of biomedical literature is a well-established approach in revealing new associations between pathologies and genes [18]. In recent years, approximately 30% of the newly Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved vaccines and drugs are repurposing discoveries in the US [19]. As a classic example, sildenafil (Viagra), originally targeted towards angina, is used in the treatment of erectile dysfunction in men in 1998 [20].

In this study, we use bioinformatics methods to investigate novel drugs for OA. Firstly, we made a preliminary list of candidate genes for further analysis by mining text. Next, we analyzed the characteristics of genes selected by way of GO and KEGG enrichment analysis. Then, we acquired the association between those genes by PPI analysis and generated focused target genes set by the MCODE plugin. Finally, candidate key drugs were discovered from the final genes set through the drug-gene interaction analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Text Mining

The web-based service pubmed2ensembl (http://pubmed2ensembl.ls.manchester.ac.uk/) was used to perform text mining. The link is a publicly available resource database, including biological articles from MEDLINE life science journals and online books, and linking over 2,000,000 literature to nearly 150,000 genes from 50 species [21]. All gene names, related to the search concepts found in the available literature, are extracted from pubmed2ensembl when a query is performed [21]. In this study, we performed queries using the search terms (Osteoarthritis and NSAIDs) for producing two gene lists. Common unique genes between the two lists were then used to proceed to the next steps.

2.2. Biological Process and Pathway Analysis

We used the FUNRICH (http://www.funrich.org) for a GO enrichment analysis, including biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), molecular function (MF). FUNRICH is a stand-alone software tool whose one kind of function is for the functional enrichment of genes and proteins. The KEGG pathway analysis was performed with annotations (chemokine activity, catalytic activity, transcription factor activity, receptor activity, growth factor, receptor binding, and cytokine activity) from the DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery), which contained all the gene terms we mined. DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/summary.jsp) is a web-based tool, providing functional annotation tools for the researcher to understand biological meaning among a large list of genes.

2.3. Protein Interaction Network

We used the STRING database (http://string-db.org) for acquiring a key estimation of protein-protein functional associations. The study reported that this database could comprehensively integrate the PPI of selected genes. Then, we used the MCODE (molecular complex detection) plugin of Cytoscape (version 3.7.1) to seek a gene list of the tightest interaction network among all common genes. The parameters of MCODE were used: node score cutoff ≥0.05, degree cutoff ≥2, maximum depth = 100, and k-score ≥2 [22].

2.4. Quantitative Real-Time- (qRT-) PCR Array Validation

To validate the findings of bioinformatics analysis, synovial tissues from patients were harvested for qRT-PCR validation between the OA group (n = 8) and the control group (n = 8). The use of verbal consent was approved by Fuzhou Second Hospital affiliated to Xiamen University, and oral consent was obtained by each subject. Total RNA from the lesion of synovial tissue was extracted using TRIzol reagent (TAKARA, Dalian, China). RNA samples from total RNA were reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The conditions were set as follows: 95°C for 30 sec for denaturation, cycling stage 95 °C/10 s, and 60 °C/0.5 minutes (40 cycles). GAPDH was then handled as an internal reference. Relative mRNA expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. P values < 0.05 indicated a significant difference. The sequences of primers are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Lists of primer sequences used for quantitative real-time PCR.

| Genes | Sequences | |

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| PTGS2 | CCGAGGTGTATGTATGAGTG | GGGAGGGAGAAATTAATGGG |

| NLRP3 | CACAGTCTAGTTGGGAAGAC | GAGACCATGTCTTCCATCAC |

| MMP13 | CTTCCTCTTCTTGAGCTGG | GCAAGATACTCTACCTCTGC |

| MMP9 | ATGTCTAAGGAGGGGAGATC | CTCAAACTCCTGAGCTTCAG |

| IL1RN | CTGGTATGTTCCTGTGGAAG | GGATAGGAGGCAGGACTAAT |

| CCL2 | GTAATCAAAGAGAGGGTGGG | CTCATTACCTCTGCAGAGTC |

| CXCL8 | CAAGCTTCTAGGACAAGAGC | CTTACCTTCACACAGAGCTG |

| TNFRSF1B | GGGCTGTCAGACTAGAATTG | CAGAGTATATGGCATGACCC |

| TNF | GAAGACACTCAGGGAAAGAG | TGATTAGAGAGAGGTCCCTG |

| CASP3 | CAGGCAGAGGGATCTTTATG | CACTAGGTATGAAGGTCAGC |

| IL10 | GCTTCTTAATCCCTGGGATC | CTCAGTCCTGGTCTTCTTTC |

| CD40 | CCAAAGGTCTCATAGCTAGC | GTTCTCACTCCCCATAGTTC |

| MAPK8 | GAGGTCAGATGCTCTAAGTG | CTATATTCCAGGCTAGGTGG |

| STAT3 | CTGAAAGACTTCATGGGAGG | CCTCACTTCCCAAGTTAGAC |

| IL6 | CGTCCGTAGTTTCCTTCTAG | AGGGGGAGAATACTACTCAC |

| NGF | CTCTTGTTGAAGGGGGATAG | CTCTGAGGTGCTCCTATACT |

| TP53 | GATGAGTCCTCTCTGAGTCA | GTCCTAACATCCCCATCATC |

| RELA | CTATGAAGTAGCCGCTACAG | GAAGTGATTAGGGACCCATC |

| BCL2L1 | TAGACCCAGACCTTCGTAAG | GAAGGGAGAGAAAGAGCTTC |

| VEGFA | CAGTGCTAGGAGGAATTTCC | CAGTGATCATCCTTTCCCTG |

| NOTCH1 | GGCGAGAATTATCTGTCCTC | GGATCAATTACTCAAGCCCC |

| HMGB1 | CAGGAGATCAGCAGAGATTG | CTGGGACCAGGATATGTAGA |

2.5. Drug-Gene Interactions

The web-based Drug-Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb) (version 3.0, http://www.dgidb.org) was used to search drug-gene interactions of the confirmed genes, which might cause associations with small organic compounds or drugs. The DGIdb aggregates drug-gene interaction data from 27 kinds of sources, including PharmGKB, DrugBank, NCBI Entrez, ChEMBL, PubChem, Ensembl, and other authoritative databases. It organized the results of the search so that drug-gene interaction was available to match with relevant gene entry by its source link [23].

3. Results

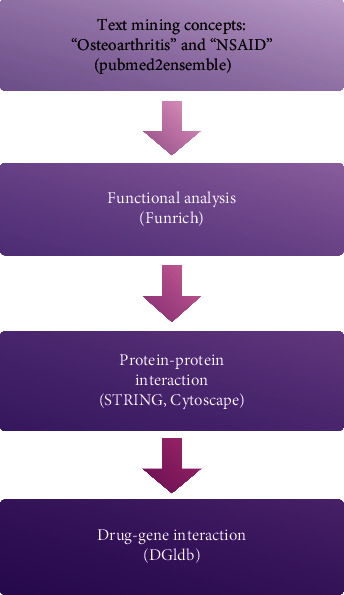

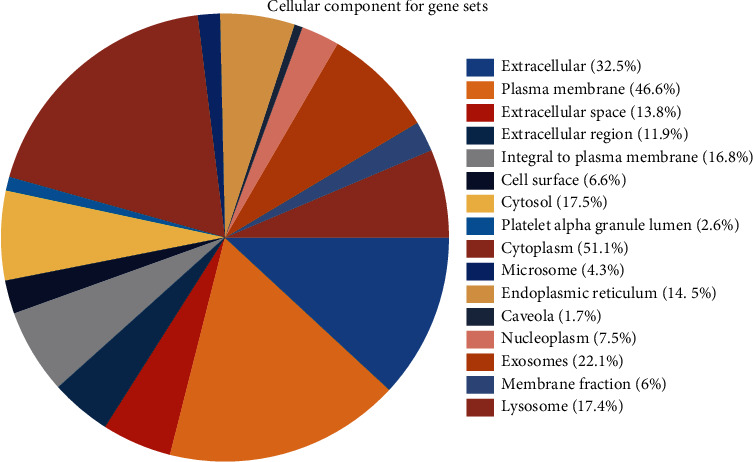

3.1. Text Mining and Biological Process

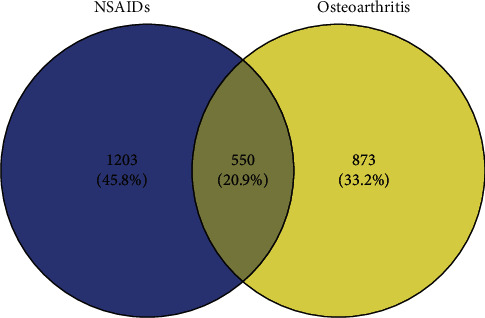

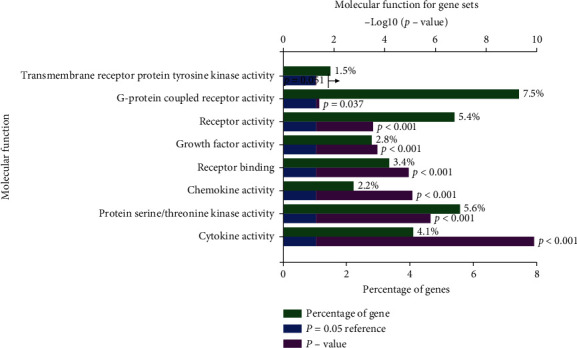

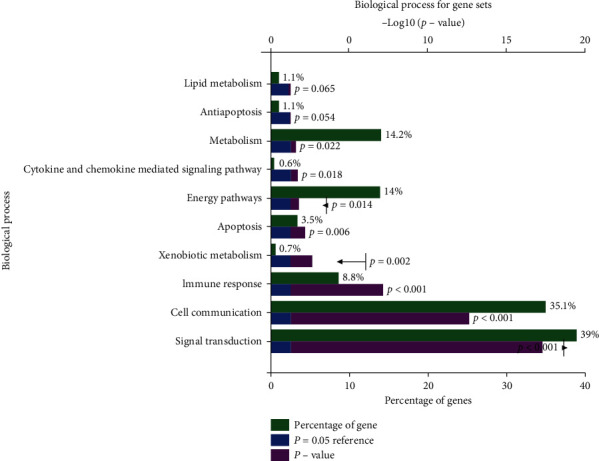

Based on the strategy of data investigation described in Figure 1, from text-mining searches by pubmed2ensembl, we determined 550 unique genes (Figure 2), related to both OA and NSAIDs (we do not rule it out that some of them may have more than one name). All gene names are shown in Appendix S1. In the process of GO biological annotations, we are based on the characteristics of the results from data analysis in FUNRICH. The cellular-components annotations revealed that most of the genes are expressed in the Cytoplasm (51.1%), plasma membrane (46.6%), and extracellular (32.5%), and other details are seen in Figure 3. The GO enrichment analysis of molecular functions (transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase activity, G-protein coupled receptor activity, receptor activity, growth factor activity, receptor binding, chemokine activity, protein serine/threonine kinase activity, and cytokine activity) demonstrated that 7.5% of the identified genes had G-protein coupled receptor activity (Figure 4). Biological process annotations showed cell communication (35.1%) and signal transduction (39%) were the most highly enriched terms (Figure 5).

Figure 1.

Overall data mining strategy. Text mining was used to identify genes associated with the concepts of OA and NSAID using pubmed2ensemble. Extracted genes were then analyzed for their function and gene ontology using Funrich. Further enrichment was obtained by molecular network analysis using STRING and Cytoscape. The final enriched gene list was then used to determine interactions with known drugs using the Drug Gene Interaction Database.

Figure 2.

A Venn diagram showing the overlapping genes between OA and NSAIDs.

Figure 3.

The cellular-component annotations of those gene sets.

Figure 4.

The molecular functions annotations of those gene sets.

Figure 5.

The biological process of those gene sets.

3.2. Pathway Analysis

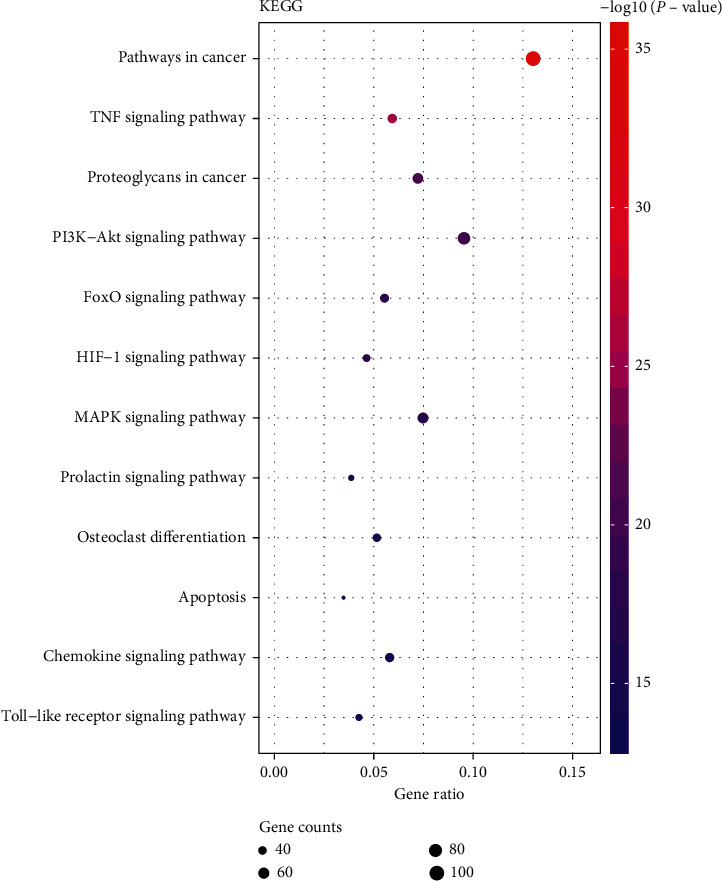

For the procedure of KEGG pathways enrichment analysis, more enriched genes and relatively low P values showed that the pathways are particularly relevant to OA and NSAIDs. The four most enriched biological KEGG pathway were (1) pathways in cancer (5.49E-36); (2) TNF signaling pathway (2.45E-26); and (3) proteoglycans in cancer (1.86E-21), PI3K-Akt signaling pathway (6.99E-21), containing 101, 46, 56, and 74 genes related to pathways enrichment analysis, respectively, and other highly enriched pathways including FoxO signaling pathway, HIF-1 signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, prolactin signaling pathway, osteoclast differentiation, apoptosis, chemokine signaling pathway, and Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. To more intuitively present the details, we conducted mapping with R statistical software (version 3.6.1) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The enriched biological KEGG pathway.

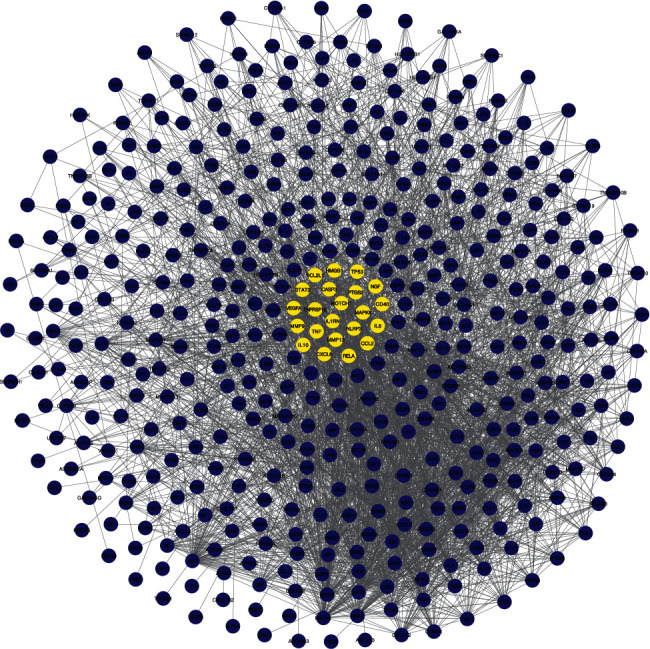

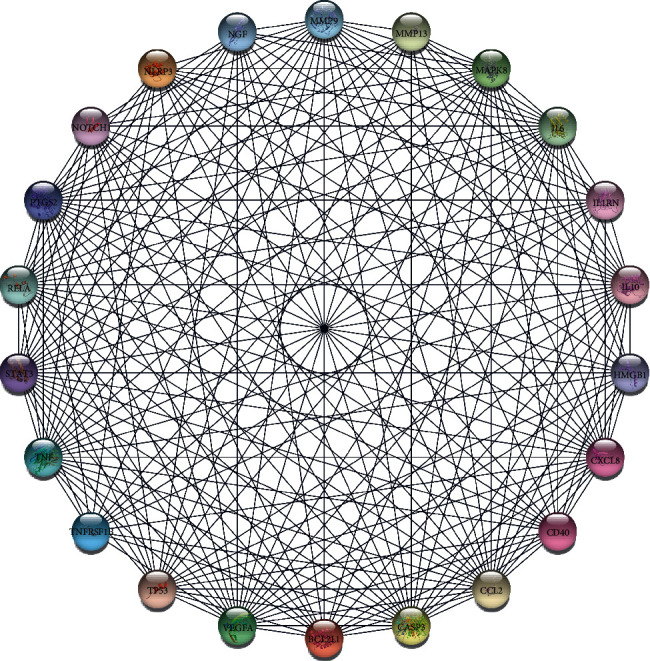

3.3. Protein-Protein Interaction

The protein-protein interaction analysis was performed using STRING and we set the following parameters: (1) minimum required interaction score: medium confidence (0.400) and (2) display simplifications: hide disconnected nodes in the network. Network Stats showed the results: the number of nodes: 452; the number of edges: 11095; average node degree: 49.1; local clustering coefficient: 0.529; expected number of edges: 4532; and PPI enrichment P value: <1.0e-16 (Figure 7). Then, the data format “.tsv” was imported from the STRING EXPORTs channel to the MCODE plugin of Cytoscape and the following parameters were set: node score cutoff: 0. 05; K- -core: 2; max. depth: 100. Based on these criteria, we selected 22 central genes which formed the tightest module network, including PTGS2, NLRP3, MMP13, MMP9, IL1RN, CCL2, CXCL8, TNFRSF1B, TNF, CASP3, IL10, CD40, MAPK8, STAT3, IL6, NGF, TP53, RELA, BCL2L1, VEGFA, NOTCH1, and HMGB1 (Figure 8). We used DAVID to perform KEGG pathways enrichment analysis of central genes and picked the top 10 most enriched biological KEGG pathways to list out in Table 2 (Table 2). From Table 2, it is not difficult to find that all of those genes are involved in the enriched pathways.

Figure 7.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of common genes.

Figure 8.

The tightest module from the PPI network.

Table 2.

Summary of KEGG pathways gene set enrichment analysis.

| Pathways | Genes in query set | Total genes in genome | Percentage (%) | P value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF signaling pathway | 9 | 108 | 0.267857 | 1.73E-10 | CASP3, TNFRSF1B, IL6, TNF, CCL2, PTGS2, RELA, MMP9, MAPK8 |

| NOD-like receptor signaling pathway | 7 | 166 | 0.208333 | 5.53E-09 | IL6, TNF, CCL2, RELA, CXCL8, MAPK8, NLRP3 |

| Pathways in cancer | 11 | 515 | 0.327381 | 1.92E-08 | CASP3, IL6, PTGS2, RELA, MMP9, VEGFA, TP53, CXCL8, MAPK8, BCL2L1, STAT3 |

| Apoptosis | 6 | 135 | 0.178571 | 5.33E-07 | CASP3, TNF, RELA, TP53, BCL2L1, NGF |

| NF-kappa B signaling pathway | 6 | 93 | 0.178571 | 2.91E-06 | TNF, PTGS2, RELA, CXCL8, BCL2L1, CD40 |

| Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 6 | 102 | 0.178571 | 7.74E-06 | IL6, TNF, RELA, CXCL8, MAPK8, CD40 |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | 5 | 50 | 0.14881 | 8.84E-06 | CASP3, TNFRSF1B, TNF, TP53, BCL2L1 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | 5 | 62 | 0.14881 | 2.38E-05 | IL6, TNF, RELA, IL10, STAT3 |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 7 | 263 | 0.208333 | 3.37E-05 | TNFRSF1B, IL6, TNF, CCL2, CXCL8, CD40, IL10 |

| Adipocytokine signaling pathway | 5 | 69 | 0.14881 | 3.40E-05 | TNFRSF1B, TNF, RELA, MAPK8, STAT3 |

To make sure that only the most enriched annotations were selected, a P value cutoff (P=1.00E − 05) was set. Among the most significantly enriched pathway annotations above the cutoff, those most relevant to OA pathology based on the available literature and research were selected. A total of 10 pathways were picked out from the analysis of enriched pathway annotations.

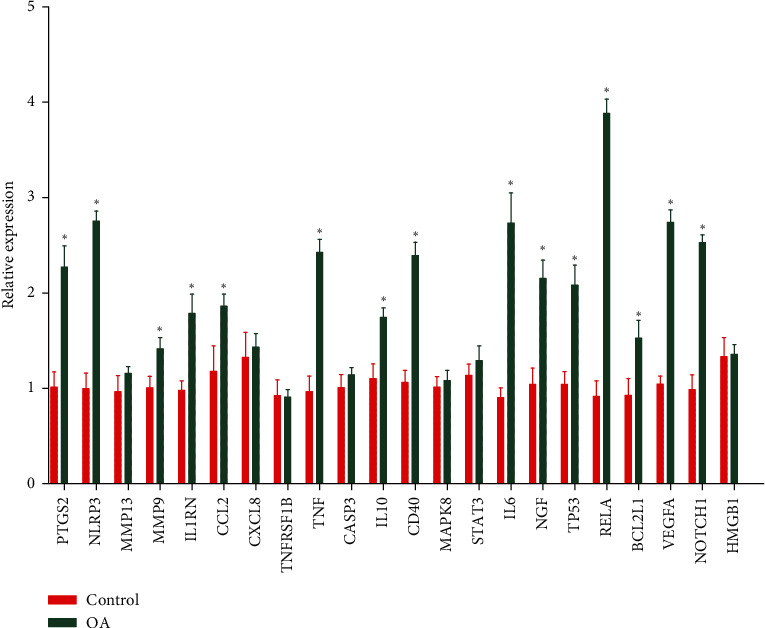

3.4. qRT-PCR Validation of the Hub Genes

A qRT-PCR approach was used to detect the expression levels of 22 potential genes. The verification result showed that the expression levels of PTGS2, NLRP3, MMP9, IL1RN, CCL2, TNF, IL10, CD40, IL6, NGF, TP53, RELA, BCL2L1, VEGFA, and NOTCH1 were significantly increased in osteoarthritis samples (P < 0.05) (Figure 9), which confirmed the analytical results of bioinformatics were reliable in this study.

Figure 9.

RT-PCR validation of the hub gene between OA and normal controls.

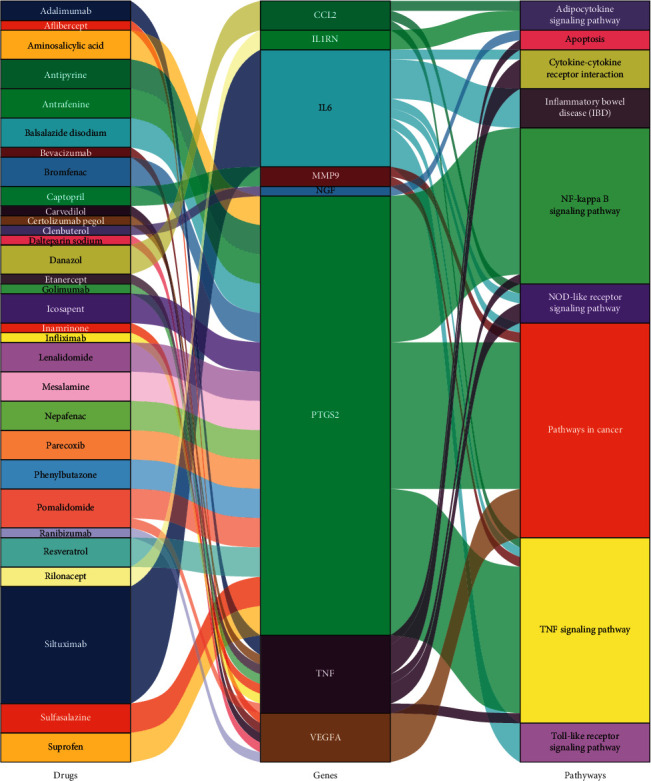

3.5. Drug-Gene Interactions

The final confirmed genes were used to conduct drug-gene interaction analysis, and a list of 53 drugs was regarded as potentially meeting possible drug therapy for OA (Table 3). Potential gene targets of the drugs in this list are PTGS2 (35 drugs), TNF (7 drugs), VEGFA (5 drugs), MMP9 (2 drugs), and CCL2, IL1RN, IL6, and NGF (1 drug each). 21 of 53 drugs have been employed to treat OA and 32 drugs (including 16 drugs target COX-2) have not yet been used in OA. The interrelation of the 32 drugs with genes and pathways is shown in Figure 10.

Table 3.

Candidate drugs targeting genes with OA.

| Number | Drug | Description | Gene | Drug-gene interaction | Score | Approved by FDA | Approved use in OA | Clinical trial phase in O A | Reference (PubMed ID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Celecoxib | COX-2 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 12 | Yes | Yes | 4 | 12093311|12086292 |

| 2 | Etodolac | Mainly COX-2 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 11 | Yes | Yes | 2 | 12824918|11009046 |

| 3 | Oxaprozin | Mainly COX-1 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 10 | Yes | Yes | 2 | 19338579|9831331 |

| 4 | Meloxicam | COX-2 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 11 | Yes | Yes | 4 | 10567199|10220944 |

| 5 | Icosapent | Eicosanoids | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 7 | Yes | No | Not available | 12573452|16190133 |

| 6 | Aminosalicylic acid | Antimycobacterial agent | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 6 | Yes | No | Not available | 16855178|12463455 |

| 7 | Mesalamine | Anti-inflammatory agent | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 9 | Yes | No | Not available | 16855178|12463455 |

| 8 | Indomethacin | Mainly COX-1 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 8 | Yes | Yes | 4 | 15668944|15730717 |

| 9 | Nabumetone | COX-2 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 11 | Yes | Yes | 4 | 11304699|12047490 |

| 10 | Tenoxicam | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 10 | Yes | Yes | 2 | 11563332|16245223 |

| 11 | Lenalidomide | Immunomodulatory drug | PTGS2 | Modulator | 3 | Yes | No | Not available | 15598423|12720152 |

| 12 | Rofecoxib | COX-2 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 15 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 10580458|11398914 |

| 13 | Piroxicam | COX-1 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 10 | Yes | Yes | 2 | 11952155|11785774 |

| 14 | Sulindac | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 9 | Yes | Yes | 2 | 11118042|10372826 |

| 15 | Mefenamic acid | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 11 | Yes | Yes | 2 | 10393680|15792781 |

| 16 | Naproxen | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 11 | Yes | Yes | 4 | 17604186|17612049 |

| 17 | Sulfasalazine | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 7 | Yes | No | Not available | 16855178|12463455 |

| 18 | Phenylbutazone | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 9 | Yes | No | Not available | 15939622|15489888 |

| 19 | Diflunisal | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 11 | Yes | Yes | Not available | 11315375|8737748 |

| 20 | Suprofen | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 7 | Yes | No | Not available | 11885959|17139284 |

| 21 | Salicylic acid | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 10 | Yes | Yes | Not available | 15035793|15348270 |

| 22 | Aspirin | Mainly COX-1 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 12 | Yes | Yes | Not available | 17522398|17181859 |

| 23 | Bromfenac | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 6 | Yes | No | Not available | 16982289|16846546 |

| 24 | Ketoprofen | COX-2 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 11 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 14513718|11729362 |

| 25 | Balsalazide disodium | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 7 | Yes | No | Not available | 17981262|12950415 |

| 26 | Lumiracoxib | COX-2 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 10 | Yes | Yes | 3 | 14965322|15017615 |

| 27 | Salsalate | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 7 | Yes | Yes | Not available | 9711054|10452868 |

| 28 | Ginseng, Asian | Adaptogen | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 4 | Yes | No | Not available | 17436372|15753395 |

| 29 | Antrafenine | Cyclooxygenase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 7 | Yes | No | Not available | 17604186|17612049 |

| 30 | Antipyrine | Cyclooxygenase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 2 | Yes | No | Not available | 11695253 |

| 31 | Tiaprofenic acid | PTG synthetase inhibitor | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 8 | Yes | Yes | Not available | 2277128|11752352 |

| 32 | Etoricoxib | COX-2 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 12 | Yes | Yes | 4 | 17573128|17164136 |

| 33 | Resveratrol | Polyphenolic phytoalexin | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 2 | Yes | No | 3 | 11752352 |

| 34 | Nepafenac | COX-1 and COX-2 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 5 | Yes | No | Not available | 10850857 |

| 35 | Parecoxib | COX-2 | PTGS2 | Inhibitor | 3 | Yes | No | Not available | 10794682 |

| 36 | Captopril | Inhibitor of ACE | MMP9 | Inhibitor | 5 | Yes | No | Not available | 12381651|19057128 |

| 37 | Glucosamine | Precursor of lipids | MMP9 | Antagonist | 6 | Yes | Yes | 4 | 12405690|16616490 |

| 38 | Rilonacept | Interleukin 1 inhibitor | IL1RN | Binder | 3 | Yes | No | Not available | 23319019|12815153 |

| 39 | Danazol | Gonadotropin inhibitor | CCL2 | Inhibitor | 3 | Yes | No | Not available | 11056242|11216879 |

| 40 | Etanercept | Fusion protein | TNF | Antibody | 12 | Yes | No | Not available | 10375846|10405518 |

| 41 | Adalimumab | Monoclonal antibody | TNF | Antibody | 12 | Yes | No | Not available | 12044041|15022409 |

| 42 | Infliximab | TNF-α blocker | TNF | Inhibitor | 17 | Yes | No | Not available | 16456024|16052578 |

| 43 | Inamrinone | PDE3 inhibitor | TNF | Inhibitor | 6 | Yes | No | Not available | 11805217|1611705 |

| 44 | Golimumab | Monoclonal antibody | TNF | Antibody | 6 | Yes | No | Not available | 21079302 |

| 45 | Certolizumab pegol | TNF-α inhibitor | TNF | Neutralizer | 6 | Yes | No | Not available | 23620660 |

| 46 | Pomalidomide | COX-2 | TNF | Inhibitor | 2 | Yes | No | Not available | 22917017 |

| 47 | Siltuximab | Monoclonal antibody | IL6 | Antagonist | 4 | Yes | No | Not available | 8823310 |

| 48 | Clenbuterol | Beta(2) agonist | NGF | Stimulator | 6 | Yes | No | Not available | 10525174|10403429 |

| 49 | Aflibercept | Recombinant fusion protein | VEGFA | Inhibitor | 7 | Yes | No | Not available | 22813448 |

| 50 | Carvedilol | Beta adrenoceptor blocker | VEGFA | Other | 5 | Yes | No | Not available | 15071347|15942707 |

| 51 | Dalteparin sodium | Anticoagulant | VEGFA | Inhibitor | 4 | Yes | No | Not available | 17692905|21091776 |

| 52 | Ranibizumab | VEGFA antagonist | VEGFA | Inhibitor | 14 | Yes | No | Not available | 18046235|18054637 |

| 53 | Bevacizumab | VEG inhibitor | VEGFA | Inhibitor | 10 | Yes | No | Not available | 15705858|11752352 |

Fifty-three drugs which met the criteria of targeting one of the candidate genes by an appropriate interaction were collected in the final list. Whether the drug has been approved by the FDA and whether it has been approved for OA are documented in the table. ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; PDE: phosphodiesterase; PTG: prostaglandin; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

Figure 10.

The interrelation of 32 drugs with genes and pathways.

4. Discussion

As the obesity rate and ages of the world population increase, the morbidity of OA is increasing especially in older adults. OA is one of the most common conditions causing decreased function, joint pain, and stiffness. To relieve symptoms by the improvement of joint function and reduction of pain, the classical treatment of OA is still using NSAIDs [24]. However, the long-term use of NSAIDs sometimes may cause headaches, gastrointestinal disturbances, and cardiovascular side effects. To address this question, we utilized bioinformatics tools to identify existing potential NSAIDs for OA treatment. Consequently, we identified eight targeting potential genes and 53 drugs associated with OA (Table 3).

The exact mechanism of OA pathogenesis remains to be elucidated, but the inflammation and cartilage degradation is the main pathological feature of OA [25]. The mechanism at a molecular level of inflammation and cartilage destruction involves multiple factors, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), COX-2, and ADAMTS (a disintegrin and metalloproteinases with thrombospondin motifs), in articular chondrocytes [26]. Mechanical stress, proinflammatory cytokines (including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-17, IL-1β) can promote COX-2 and ADAMTS expression and accelerate the destruction of cartilage and OA development. PGE2 that is associated with the activity of TNF-α and IL-1β can lead to a large reduction in proteoglycan content in cartilage tissue [27]. The MMPs (especially 1 and 13) play major roles in cartilage matrix degradation and result in focal lesions in the articular surface [28]. Several studies reported increased expression of MMP-13 in OA. This difference may be caused as follows: PCR stochasticity, primer biases, multiple species in individual samples, and pooling of samples exerts too many uncertainties that could bias the results. Additionally, the sample size was insufficient. Proinflammatory cytokines can increase in nitric oxide (NO) and PGE2 synthesis and release [29]. Previous studies have shown that the anti-inflammatory effects of NSAIDs mainly depend on the function of inhibiting COX, reducing the generation of prostaglandins, which are the major mediator of pain and inflammatory response [30, 31].

In our results, the PTGS2 gene responsible for encoding COX-2 is corresponding to the most diverse class of drugs. Among them, 20 drugs are not applied for the treatment of OA but have been approved by the FDA to treat other diseases and obtained excellent outcomes. The mesalamine (5-ASA) compounds are commonly well tolerated and rare complications [32]. In the European [33] and the United States [34] guidelines, 5-ASA was recommended as a frontline agent for treating patients with mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. From the molecular structures' point of view, the intensity of halogenation is positively correlated with drug therapy strength. It is considered that such a difference may also allow bromfenac (containing a bromine atom) wider ocular distribution [35]. Bromfenac is better than both dexamethasone and fluorometholone in preventing cystoid macular edema [36]. Although the molecular mechanism of sulfasalazine remained ambiguous, the drug is known to play a role that is immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory [37]. It has also been the widely used treatment of other diseases, such as and ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, and ankylosing spondylitis [34, 38, 39].

The platelet-derived growth factor superfamily secreted vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), a glycoprotein that mediates glomerular endothelial cell biological functions [40]. Glomerular visceral epithelial cells, known as podocytes, secrete VEGFA, a glycoprotein that mediates glomerular endothelial cell biological functions [40]. In the early stages of diabetes, podocytes increasing the expression of Vegfa can lead to both insulin deficiency and resistance in rodents [41]. Furthermore, Vegfa is also irreplaceable to induce the formation of cartilage. A significant positive correlation between the overexpression of Vegfa in osteochondrogenic cells and bone mass is also observed [42]. At the early stage of bone development, Vegfa was regarded as a regulator of both osteoblast differentiation and perichondrial vascularity [43].

There were also some limitations to the study. Firstly, the databases we used may be limited to get accurate information on genes concerning function or role. With the databases becoming more comprehensive, the results of the analysis will be more accurate. Although we have validated results in multiple biological databases, further molecular biological experiments of the large sample are indispensable to confirm the reliability of the results. We cannot ensure that a given gene is known to all relations of existing drugs and drug-gene interactions. Therefore, it is possible that we missed or ignored the drugs which could potentially be useful.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have presented a way to investigate the potential candidate drugs which target the genes/pathways relevant to OA. With the databases and analytical tools evolved and improved, such a method may be used routinely to explore more diseases and to facilitate drug repositioning efforts in the pharmaceutical industry. From the present analysis, we identified a total of 53 potential drugs, of which 32 drugs targeted other OA-relevant pathways but have not yet been used in OA, which could give us a clue to novel therapeutic targets as potential treatments for OA. However, further direct evidence by molecular biological experiments is necessary to make clear their association with OA.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Project of Innovation Platform for Fuzhou Health and Family Planning Commission (no. 2017-S-wp1).

Abbreviations

- OA:

Osteoarthritis

- NSAIDs:

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- GO:

Gene ontology

- KEGG:

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- PPI:

Protein-protein interaction

- COX:

Cyclooxygenase

- PGH2:

Prostaglandin H2

- PGE:

Prostaglandin E

- PTGS1:

Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase

- PTGS2:

Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase

- FDA:

Food and Drug Administration

- BP:

Biological process

- CC:

Cellular component

- MF:

Molecular function

- DGIdb:

Drug-Gene Interaction Database

- MMPs:

Matrix metalloproteinases

- TNF-α:

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- IL:

Interleukin

- NO:

Nitric oxide

- VEGFA:

Vascular endothelial growth factor A.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the supplementary information file.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary Materials

All gene names are shown in Appendix S1.

References

- 1.Wenham C. Y., Conaghan P. G. The role of synovitis in osteoarthritis. Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease. 2010;2(6):349–359. doi: 10.1177/1759720X10378373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lajeunesse D., Massicotte F., Pelletier J.-P., Martel-Pelletier J. Subchondral bone sclerosis in osteoarthritis: not just an innocent bystander. Modern Rheumatology. 2003;13(1):7–14. doi: 10.1007/s10165030000110.3109/s101650300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedson J., Croft P. R. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2008;9(1):p. 116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.da Costa B. R., Reichenbach S., Keller N., et al. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2017;390(10090):e21–e33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glyn-Jones S., Palmer A. J. R., Agricola R., et al. Osteoarthritis. The Lancet. 2015;386(9991):376–387. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60802-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitta M., Esposito C. I., Li Z., Lee Y.-Y., Wright T. M., Padgett D. E. Failure after modern total knee arthroplasty: a prospective study of 18,065 knees. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2018;33(2):407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jevsevar D. S. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd edition. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2013;21(9):571–576. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201309020-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hochberg M. C., Altman R. D., April K. T., et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care & Research. 2012;64(4):465–474. doi: 10.1002/acr.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vane J. R. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nature New Biology. 1971;231(25):232–235. doi: 10.1038/newbio231232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zweers M. C., de Boer T. N., van Roon J., Bijlsma J. W., Lafeber F. P., Mastbergen S. C. Celecoxib: considerations regarding its potential disease-modifying properties in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2011;13(5):p. 239. doi: 10.1186/ar3437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sostres C., Gargallo C. J., Arroyo M. T., Lanas A. Adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, aspirin and coxibs) on upper gastrointestinal tract. Best Practice and Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 2010;24(2):121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kearney P. M., Baigent C., Godwin J., Halls H., Emberson J. R., Patrono C. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2006;332(7553):1302–1308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trelle S., Reichenbach S., Wandel S., et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7086.c7086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gore M., Tai K.-S., Sadosky A., Leslie D., Stacey B. R. Use and costs of prescription medications and alternative treatments in patients with osteoarthritis and chronic low back pain in community-based settings. Pain Practice. 2012;12(7):550–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott D. L., Berry H., Capell H., et al. The long‐term effects of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs in osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized placebo‐controlled trial. Rheumatology. 2000;39(10):1095–1101. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.10.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams C. P., Brantner V. V. Estimating the cost of new drug development: is it really $802 million? Health Affairs. 2006;25(2):420–428. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moosavinasab S., Patterson J., Strouse R., et al. RE:fine drugs: an interactive dashboard to access drug repurposing opportunities. Database. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1093/database/baw083.baw083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosca E., Bertoli G., Piscitelli E., et al. Identification of functionally related genes using data mining and data integration: a breast cancer case study. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10(S12):p. S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-S12-S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin G., Wong S. T. C. Toward better drug repositioning: prioritizing and integrating existing methods into efficient pipelines. Drug Discovery Today. 2014;19(5):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novac N. Challenges and opportunities of drug repositioning. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2013;34(5):267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baran J., Gerner M., Haeussler M., Nenadic G., Bergman C. M. pubmed2ensembl: a resource for mining the biological literature on genes. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):p. e24716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito R., Smoot M. E., Ono K., et al. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nature Methods. 2012;9(11):p. 1069. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner A. H., Coffman A. C., Ainscough B. J., et al. DGIdb 2.0: mining clinically relevant drug-gene interactions. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44(D1):D1036–D1044. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bannuru R. R., Osani M. C., Vaysbrot E. E., et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2019;27(11):1578–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van den Berg W. B. Osteoarthritis year 2010 in review: pathomechanisms. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2011;19(4):338–341. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldring M. B., Otero M. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2011;23(5):p. 471. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328349c2b1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mastbergen S. C., Bijlsma J. W. J., Lafeber F. P. J. G. Synthesis and release of human cartilage matrix proteoglycans are differently regulated by nitric oxide and prostaglandin-E2. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2008;67(1):52–58. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martel-Pelletier J., Boileau C., Pelletier J.-P., Roughley P. J. Cartilage in normal and osteoarthritis conditions. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2008;22(2):351–384. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldring M. B. Osteoarthritis and cartilage: the role of cytokines. Current Rheumatology Reports. 2000;2(6):459–465. doi: 10.1007/s11926-000-0021-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tchetina E. V., Di Battista J. A., Zukor D. J., Antoniou J., Poole A. R. Prostaglandin PGE2 at very low concentrations suppresses collagen cleavage in cultured human osteoarthritic articular cartilage: this involves a decrease in expression of proinflammatory genes, collagenases and COL10A1, a gene linked to chondrocyte hypertrophy. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2007;9(4):p. R75. doi: 10.1186/ar2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Attur M., Al-Mussawir H. E., Patel J., et al. Prostaglandin E2 exerts catabolic effects in osteoarthritis cartilage: evidence for signaling via the EP4 receptor. The Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(7):5082–5088. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chidlow J. H., Jr., Shukla D., Grisham M. B., Kevil C. G. Pathogenic angiogenesis in IBD and experimental colitis: new ideas and therapeutic avenues. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 2007;293(1):G5–G18. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00107.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dignass A., Lindsay J. O., Sturm A., et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2012;6(10):991–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kornbluth A., Sachar D. B. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American college of gastroenterology, practice parameters committee. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105(3):501–523. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kida T., Kozai S., Takahashi H., Isaka M., Tokushige H., Sakamoto T. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of topically applied nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in retinochoroidal tissues in rabbits. PLoS One. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096481.e96481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Q. W., Yao K., Xu W., et al. Bromfenac sodium 0.1%, fluorometholone 0.1% and dexamethasone 0.1% for control of ocular inflammation and prevention of cystoid macular edema after phacoemulsification. Ophthalmologica. Journal International D’ophtalmologie. International Journal of Ophthalmology. Zeitschrift Fur Augenheilkunde. 2013;229(4):187–194. doi: 10.1159/000346847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plosker G., Croom K. Sulfasalazine: a review of its use in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 2005;65(18):p. 2591. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565130-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akkoc N., van der Linden S., Khan M. A. Ankylosing spondylitis and symptom-modifying vs disease-modifying therapy. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2006;20(3):539–557. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lichtenstein G. R., Loftus E. V., Isaacs K. L., Regueiro M. D., Gerson L. B., Sands B. E. ACG clinical guideline: management of Crohn’s disease in adults. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018;113(4):481–517. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2018.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eremina V., Cui S., Gerber H., et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor a signaling in the podocyte-endothelial compartment is required for mesangial cell migration and survival. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;17(3):724–735. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flyvbjerg A., Dagnaes-Hansen F., De Vriese A. S., Schrijvers B. F., Tilton R. G., Rasch R. Amelioration of long-term renal changes in obese type 2 diabetic mice by a neutralizing vascular endothelial growth factor antibody. Diabetes. 2002;51(10):3090–3094. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maes C., Goossens S., Bartunkova S., et al. Increased skeletal VEGF enhances β-catenin activity and results in excessively ossified bones. The EMBO Journal. 2010;29(2):424–441. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan X., Murata Y., Liu Y., Nicolae C., Olsen B. R., Berendsen A. D. Vegfa regulates perichondrial vascularity and osteoblast differentiation in bone development. Development. 2015;142(11):1984–1991. doi: 10.1242/dev.117952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

All gene names are shown in Appendix S1.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the supplementary information file.