Abstract

Theories of narcissism emphasize the dynamic processes within and between grandiosity and vulnerability. Research seeking to address this has either not studied grandiosity and vulnerability together or has used dispositional measures to assess what are considered to be momentary states. Emerging models of narcissism suggest grandiosity and vulnerability can further be differentiated into a three-factor structure – Exhibitionistic Grandiosity, Entitlement, and Vulnerability. Research in other areas of maladaptive personality (e.g., borderline personality disorder) has made headway in engaging data collection and analytic methods that are specifically meant to examine such questions. The present study took an exploratory approach to studying fluctuations within and between grandiose and vulnerable states. Fluctuations – operationalized as gross variability, instability, and lagged effects – were examined across three samples (two undergraduate and a community sample oversampled for narcissistic features; Total person N = 862; Total observation N = 36,631). Results suggest variability in narcissistic states from moment to moment is moderately associated with dispositional assessments of narcissism. Specifically, individuals who are dispositionally grandiose express both grandiosity and vulnerability, and vary in their overall levels of grandiosity and vulnerability over time. On the other hand, dispositionally vulnerable individuals tend to have high levels of vulnerability and low levels of grandiosity. Entitlement plays a key role in the processes that underlie narcissism and narcissistic processes appear unique to the construct and not reflective of broader psychological processes (e.g., self-esteem). Future research should consider using similar methods and statistical techniques on different timescales to study dynamics within narcissism.

Keywords: Narcissism, Grandiosity, Vulnerability, Variability, Ecological Momentary Assessment

Over the past decade, the study of narcissism has become increasingly popular with an average of 357 peer-reviewed articles published per year since 2010 (Miller et al., 2017). Indeed, narcissism has enjoyed broad interest across the fields of clinical psychology, psychiatry, and social/personality psychology resulting in a large empirical literature that spans diverse areas of inquiry (Cain et al., 2008; Pincus & Lukowitsky, 2010). Clinical psychology and psychiatry tend to emphasize the more maladaptive aspects of narcissism, which have been linked to significant personal and social costs, including depression, suicidality, and violence (e.g., Ansell et al., 2015; Dashineau et al., 2019; Ellison et al., 2013; Pincus et al., 2009). Social and personality psychology tends to also focus on more adaptive features of narcissism (e.g., Sedikides et al., 2004). In the present study we treat narcissism as a multidimensional ensemble of personality traits that manifest in relatively more or less adaptive or maladaptive behavior.

It is generally agreed that narcissism is dimensional (e.g., Aslinger et al., 2018; Foster & Campbell, 2007), and that its manifestations can be divided into two major themes—narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability (Cain et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2017). Narcissistic grandiosity is defined by a grandiose sense of self, lack of empathy, and entitlement (e.g., Cain et al., 2008). Individuals high in narcissistic grandiosity are likely to be overtly immodest, self-promoting, and self-enhancing (Miller et al., 2017). Those same individuals are likely to endorse high levels of the basic personality traits of antagonism and extraversion (e.g., Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Narcissistic vulnerability is associated with acute sensitivity to and avoidance of embarrassment and shame which manifests as self-doubt, defensive social withdrawal, and contingent self-esteem. (e.g., Morf, 2006; Cain et al., 2008). Individuals high in narcissistic vulnerability are often distrustful of others and outwardly distressed and fragile (e.g., Miller et al., 2017). Narcissistic vulnerability is distinct from narcissistic grandiosity in that it is associated with pervasive negative emotionality and is broadly associated with other forms of personality pathology (Edershile et al., 2019). Though researchers tend to consider narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability distinct forms of narcissism, it has been suggested that what these two features of narcissism share is a core of entitlement and an antagonistic interpersonal stance (Krizan & Herlache, 2017; Miller et al., 2016).

Whereas it was original suggested that grandiosity and vulnerability represent two different subtypes of the disorder (e.g., Miller et al., 2014), the shared core of entitlement of these manifestations have led researchers to reconsider the structure of narcissism (Brown et al., 2009). Some argue that the antagonistic core is so central to narcissism that it is “necessary and near sufficient” for a diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder (pg. 13: Lynam & Miller, 2019; See also Lynam & Miller, 2015; Miller, Lynam, Hyatt, & Campell, 2017). This has resulted in several models that revise the originally proposed two-factor structure of narcissism. These models argue that dispositional narcissism may best be organized with a three-factor structure that separates out core antagonism from grandiosity and vulnerability, and keeps each of them as unique factors (Krizan & Herlache, 2017; Miller et al., 2016; Wright & Edershile, 2018). In this model, the core of narcissism is anchored on antagonism and the “peripheral” traits become the features that are unique to grandiosity and vulnerability.

Whereas researchers agree that a three-factor structure well-captures narcissism, they have debated what the best labels are of this three-factor structure (e.g., Wright & Edershile, 2018). Some have referred to this three-factor structure as “antagonism, extraversion, and neuroticism” (e.g., Miller et al., 2016). Though entitlement, grandiosity, and vulnerability inevitably share features of these traits, we do not consider them to be entirely overlapping. Others have labeled this three-factor structure “grandiosity, vulnerability, and self-importance” (Krizan & Herlache, 2017). We posit that the labels of this three-factor structure must capture the unique properties that these features have to narcissism, as opposed to more general and broader personality traits. Thus, throughout the rest of this manuscript, we will refer to the three-factor structure as “exhibitionistic grandiosity, entitlement, and vulnerability.” Regardless of the names chosen for this three-factor structure, evidence of these factors requires researchers to revisit early theories of narcissism and to consider the centrality of antagonism’s role and the narrower conceptualization of grandiose and vulnerable features net of this antagonistic core.

Unlike psychiatric disorders that are episodic, like major depressive episodes, personality pathology, including narcissism, is defined by its relative long-term stability and pervasiveness (e.g., Clark, 2007). These aspects may explain why narcissism is so often studied using broad dispositional and questionnaire-based research designs. Indeed, in the last couple of decades, measures designed to assess grandiosity, vulnerability, or both have proliferated (e.g., Hyler, 1994; Back et al., 2013; Glover et al., 2012; Pincus et al., 2009). Dispositional measures of grandiosity and vulnerability are designed to capture how individuals present in general across time and situations. Yet, despite the fact that contemporary measures of grandiosity and vulnerability correlate, looking across the wide-range of available measures, each has a distinct pattern of antecedents, concurrent associations, and predictive validity (Miller, Dir, et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2014. 2016; Miller et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2012). These results have been difficult to integrate and align with contemporary theoretical models.

In particular, despite the relative stability of narcissism observed within individuals, prominent theories of narcissism would suggest that narcissistic individuals are not always consistent in their presentation of narcissistic features. Several clinical accounts suggest that patients do not always present with the same manifestation of narcissism week-to-week. For example, Wright (2014) describes a patient who first presents with symptoms in line with vulnerability and over time exhibits more grandiose features. Pincus and colleagues (2014) describe a similar pattern, suggesting that presentation of narcissistic vulnerability followed by narcissistic grandiosity is common in patients who seek treatment for their personality disturbance. Beyond these clinical accounts, theorists have long-argued that that grandiosity and vulnerability are two sides of the same coin, they co-occur within the same individual, and it is the processes underlying fluctuations between grandiose and vulnerable states that drive the observed dysfunction. (Kernberg, 1975; Ronningstam, 2009, 2011; Pincus et al., 2014; Wright, 2014).

Some theories have suggested that it is the ebb and flow of self-esteem across time that drives fluctuational patterns of the narcissistic individual (e.g., Rhodewalt et al., 1998; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1998). Others have argued that, though self-esteem may be a factor, it appears to be grandiosity and vulnerability, specifically, that are responsible for such fluctuational shifts. Ronningstam (2009) suggests that grandiose individuals may experience threats to their self-esteem that evoke “defensive grandiose behaviors.” The individual may engage in self-regulatory behaviors to affirm “the grandiose but vulnerable self.” Though Ronningstam (2009) suggests that observed fluctuations are likely a consequence of grandiosity and vulnerability, she argues that other processes (e.g., self-esteem and empathy) may be impacted over the course of fluctuations in grandiosity and vulnerability. In particular, fluctuations in grandiosity and vulnerability have a functional component for the individual and are representative of (perhaps failed) regulatory patterns (Kernberg, 1975, 2009). By engaging in such regulatory patterns (or fighting dysregulation), the narcissistic individual strives to return to a state of control (Kohut, 1971, 1977; Gabbard, 1998).

Some theorists have aimed to describe such observed fluctuations in grandiosity and vulnerability as “cycles of rage” (e.g., Horowitz, 2009). Though clearly related to regulatory patterns, the description of “rage” serves as a vehicle for understanding the different states through the process of regulation. Theorists argue that different forms of rage are differentially indicative of grandiosity or vulnerability. Grandiose rage serves as a defense against a damaged (or vulnerable) interior (Horowitz, 2009; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001). In an alternative state, an individual may feel bitter and withdrawn, believing that they are treated unfairly by others (the vulnerable self). Further still, narcissistic individuals have been described as exhibiting a “mixed state” where the individual may experience both shame and anger. Through these different rage experiences, the narcissistic individual is prone to experience varying emotions and engage in a range of psychological defenses. For example, Grubbs and Exline (2016) have argued that when entitled individuals realize the mismatch between their expectations and reality, they will further try to bolster their self-esteem. It is in a state of vulnerable entitlement, in which the individual is working to return to a state of grandiosity, that they are prone to experience interpersonal conflict. Broadly, it appears that fluctuations between grandiosity and vulnerability are a key feature for narcissistic expression. Clinical theories argue that fluctuations in grandiosity and vulnerability represent efforts of self-regulation that can be observed through changes in self-esteem and expressions of anger.

Importantly, though accounts of narcissistic fluctuations are common to all extant theoretical models, the exact form of these fluctuations remains ill-defined and poorly understood. Clinical descriptions of patients who exhibit such fluctuations suggest that movement between states of grandiosity and vulnerability may occur between treatment sessions (e.g., week-to-week or within-week). These theories additionally suggest that states of vulnerability precede states of grandiosity. Theories regarding narcissistic rage suggest that individuals may move between states of grandiosity and vulnerability but may not do so in any systematic pattern (e.g., moving from states of grandiose rage, to a mixed state, and back to a grandiose state). Thus, theories on narcissistic fluctuation range in the degree to which they emphasize systematic shifts versus general variability in state expression. A further consideration is that clinical descriptions of fluctuations in narcissism have largely only referenced one’s general dispositional level of grandiosity and vulnerability, and have not yet directly considered individual differences in a three-factor structure of narcissism. Thus, though one’s level of entitlement has not been explicitly mentioned in any of the above theories, it may play a crucial role in helping clinicians and researchers understand the nature of observed fluctuations between grandiosity and vulnerability.

Theories regarding state-level fluctuations suggest that the pathology is derived, in part, from the nature of the fluctuations (e.g., emotional instability for borderline vs. grandiosity/vulnerability for narcissism). The form of regulatory processes and by extension the observable fluctuations are what differentiates personality pathologies from each other and from other disorders (Hopwood, 2018; Wright, 2011; Wright & Kaurin, 2020). Like borderline personality disorder, fluctuations in narcissism may reflect processes that serve to maintain the pathology. Thus, studying state-level, or momentary, fluctuations rather than dispositional levels may elucidate new and more effective intervention targets. Here, the vast dispositional assessments available for narcissism fall short and even using a comprehensive battery of trait measures, as Miller and colleagues (2017) suggest, does not help us to directly understand the putative dynamic processes that link narcissistic grandiosity and vulnerability.

Recent empirical evidence only indirectly supports theories regarding fluctuations between grandiosity and vulnerability (Gore & Widiger 2016; Hyatt et al., 2017). Gore and Widiger (2016) asked clinicians and clinical psychology professors to identify someone who fit either a “grandiose narcissist” or a “vulnerable narcissist.” Participants rated the individual they had in mind across traits within the matched domain (e.g., if considering a grandiose narcissist, rating them on grandiose characteristics). Participants were then asked to rate the individual in the other domain (e.g., rating a grandiose narcissist across vulnerable characteristics). Results indicated that individuals selected for exhibiting dispositional narcissistic grandiosity were particularly likely to also show vulnerable tendencies at some point. The opposite pattern, however, was not found to be true. Hyatt and colleagues (2017) replicated these findings and extended them to suggest that, someone considered to be a grandiose narcissist responds to threats to their ego with anger whereas a vulnerable narcissist responds with a broader range of emotions, including anger. Broadly, these studies suggest that variability may be a feature of narcissism, yet there may be some key differences between someone considered a “grandiose narcissist” and someone considered a “vulnerable narcissist.” However, given that these studies used cross-sectional dispositional assessments, conclusions regarding explicit momentary fluctuations are impossible.

Some researchers have investigated dynamic fluctuations within narcissism more directly, most often at the daily level. These studies have examined dynamic associations between narcissism, self-esteem, life satisfaction, and/or affect (Giacomin & Jordan, 2016; Akhtar & Thomson, 1982; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995; Bosson et al., 2008; Geukes et al., 2016). For instance, Geukes and colleagues (2016) examined two subtypes of narcissistic grandiosity, admiration and rivalry, and how these domains track with overall self-esteem level and variability in daily life. Results reveal that dispositional admiration, the agentic/exhibitionistic aspect of narcissism, is associated with higher self-esteem level and lower self-esteem variability. Dispositional rivalry, the antagonistic dimension of narcissism, is associated with lower levels of self-esteem and higher levels of variability. Broadly, these results suggest there are specific patterns of variability in state self-esteem with regard to trait narcissism, and in fact these may account for prior inconsistent results in the association between narcissism and fluctuations in self-esteem (Bosson et al., 2008). Though these studies are an important contribution to the literature on dynamic processes in narcissism, they do not directly assess the core features of grandiosity and vulnerability as states. In particular, these studies tend to highlight the role of self-esteem or affective shifts rather than emphasizing actual shifts in grandiosity and vulnerability, which are what dynamic theories of narcissism posit. Given that these two dimensions are thought to be the features that help to maintain the pathology, this is the necessary next step for underlying the processes of narcissism.

The Current Study

The specific timescale and patterning of manifestations of grandiosity and vulnerability have not been systematically examined or even proposed in with much specificity. Accordingly, the present study is a naturalistic exploratory study designed to examine patterns of fluctuation within and across grandiosity and vulnerability in daily life using ambulatory assessment (i.e., ecological momentary assessment) of state narcissism. In particular, to test the nearly ubiquitous theoretical assertion that individuals fluctuate in grandiosity and vulnerability across time, and whether one’s narcissistic state at one time-point portends a shift to another state at the following time-point, an empirical modeling of variability and how this is associated with levels of narcissism is needed. Additionally, given the proposed three-factor structure (e.g., entitlement, exhibitionistic grandiosity, and vulnerability) has gained traction in the narcissism literature (and has been suggested as a better model of trait narcissism than grandiosity and vulnerability alone), an understanding of one’s level of antagonism’s role in such fluctuations is important. Although this trifurcated model has not been articulated at the momentary level or used to describe dynamic processes, we will examine associations between dispositional narcissism and momentary fluctuations using this novel three-dimensional structure. This will allow us to compare the associations that emerge from this new structure and the extant dispositional measures of grandiosity and vulnerability with momentary indices of variability. Thus, broadly our goal is twofold. The first is to understand variability patterns in state narcissism with respect to one’s dispositional level of grandiosity and vulnerability. The second is to understand how these patterns of variability compare when operationalizing dispositional narcissism using a three-factor structure.

In the present study, fluctuation in state narcissism is articulated in three different quantitative indices of variability that followed a similar analytic approach to Houben and colleagues (2015; see also Wang et al., 2012). The first index allows for the examination of how much total variability in narcissistic expression occurs over time. We will refer to this index as Gross variability and it is operationalized as the total amount of variance in momentary narcissism the individual displays over the course of the study. The second index allows us to examine how much change in narcissistic expression occurs, on average, from one moment the next. We will refer to this index as instability and it is operationalized as the mean of the squared successive differences in momentary narcissism scores the individual displays over the course of the study. The final index allows for an examination of how much previous narcissistic states predict the next state. This includes questions of how persistent narcissistic states are, or how likely individuals are to get “stuck” in a narcissistic state, as well as “cross-state” or “switching” effects, whereby one type of narcissistic state (e.g., vulnerability) predicts the other state (e.g., grandiosity) at the subsequent time-point. These latter effects are direct articulations testing whether grandiosity consistently serves as a compensatory mechanism for vulnerability, and whether high grandiosity places someone at risk for subsequent vulnerability. We will refer to these as inertia and cross-lagged effects, respectively. Inertia is operationalized as the autoregression of the momentary scores within a given domain (e.g., grandiosityt-1 → grandiosityt), whereas cross-lags are operationalized as the lagged effect of one domain on the other (e.g., grandiosityt-1 → vulnerabilityt). Of interest is how patterns of variability differ between those higher in narcissism versus lower. Thus, dispositional measures of narcissism (grandiosity and vulnerability as well as a three-factor structure) will be used as predictors of these different articulations of fluctuations in narcissistic states to determine whether those higher in dispositional narcissism vary more or less across time compared to those lower in dispositional narcissism.

Using this three-pronged statistical approach allows for the examination of key theoretical questions with regard to variability within narcissism: 1) Gross Variability: Broadly, how much do individuals vary in their levels of grandiosity and vulnerability across time? 1a) Does an individual’s level of dispositional grandiosity and vulnerability associate with their momentary level and variability in state grandiosity and vulnerability. 1b) Does a three-factor structure of narcissism (i.e., entitlement, exhibitionistic grandiosity, vulnerability) associate with momentary level and variability in state grandiosity and vulnerability? 2) Instability: how much do individuals change in their levels of grandiosity and vulnerability form one time point to the next? 2a) Does an individual’s level of dispositional grandiosity and vulnerability predict their occasion to occasion difference scores in state grandiosity and vulnerability? 2b) Does an individual’s level of entitlement, exhibitionistic grandiosity, or vulnerability predict their occasion to occasion difference scores in state grandiosity and vulnerability? 3) Inertia and Cross-lagged effects: how stable are grandiose and vulnerable states? 3a) Does one’s current level of grandiosity and vulnerability predict future levels of states in the same domain (e.g., grandiosityt-1 → grandiosityt) and/or the other domain (e.g., grandiosityt-1 → vulnerabilityt? 3b) Does dispositional grandiosity and vulnerability predict getting “stuck in states” (e.g., grandiosityt-1 → grandiosityt) or switching states (e.g., grandiosityt-1 → vulnerabilityt) and 3c) Does a dispositional three-factor structure of narcissism associate with Inertia and Cross-lagged effects of state level grandiosity and vulnerability?

Finally, given that it is possible that the processes of fluctuation and instability articulated above in questions 1-3 are not unique to narcissism or are not explained through fluctuations in grandiosity and vulnerability alone, we examine the extent to which associations between dispositional narcissism scales and fluctuations in state grandiosity and vulnerability are similar to, or can be accounted for by, associations between dispositional narcissism and fluctuations in state self-esteem. We also examine how fluctuations in state grandiosity and vulnerability change when using dispositional Big-5 personality features as predictors. To accomplish these different questions, we change the state variable (from grandiosity and vulnerability to self-esteem) in one model and change the dispositional variable (from grandiosity and vulnerability to the Big-5) in a different model as sensitivity analyses for our findings between dispositional narcissism and state narcissism. Thus, our final research questions are 4) How much do individuals vary in their self-esteem over time as a function of narcissism? 4a) Does an individual’s level of dispositional grandiosity and vulnerability predict their state self-esteem level and variability? 4b) Does a dispositional three-factor structure of narcissism (i.e., exhibitionistic grandiosity, entitlement, and vulnerability) predict state self-esteem level and variability? 4c) How do processes observed in question 1a change when controlling for state self-esteem level and variability? 4d) How do processes observed in question 1b change when controlling for state self-esteem level and variability? 5) How much do individuals with higher scores across the Big-5 personality traits vary in their levels of narcissism across time? 5a) Does an individual’s score in dispositional normal-range personality associate with their momentary mean and variability across grandiosity and vulnerability? 5b) How do processes observed in 1a change when controlling for dispositional Big-5 personality characteristics? 5c) How do processes observed in 1b change when controlling for dispositional Big-5 personality characteristics?

Given that it has been demonstrated that individuals high in grandiosity tend to be those that fluctuate between states of grandiosity and vulnerability, though not pre-registered, we hypothesize that in models examining how dispositional grandiosity and vulnerability associate with fluctuations in state-level grandiosity and vulnerability (research question 1a), only those high in dispositional grandiosity will experience variability in both grandiosity and vulnerability. Those high in dispositional vulnerability will experience variability in vulnerability only. No prior work examines the variable nature of a dispositional three-factor structure of narcissism with regard to state level grandiosity and vulnerability (research question 1b), nor does prior work suggest the specific timescale for which narcissistic fluctuations occur (research questions 2-3), or how such processes may compare with other psychological processes/variables (research questions 4 & 5). As such, we treat all other paths as exploratory and do not offer any hypotheses. To ensure results are robust, all analyses are replicated across three independent samples: two undergraduate samples and one community sample enriched for relevant personality traits (i.e., low modesty).

Methods

All study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board under protocol numbers PRO17120303 (Community Personality in Daily Life) and PRO17090511 (Personality and Daily Life).

Subjects

Sample 11

Undergraduates (N=231) from the University of Pittsburgh made up Sample 1 (S1) and were recruited in the Spring of 2018 from the Psychology Department Subject Pool in exchange for two course credits. Participants had to be 18 years of age and had to own an up-to-date smartphone (i.e., purchased within in the last 3 years and with up-to-date software). Participants were excluded from analyses if they had fewer than 10 total observations on the ambulatory assessment portion to ensure a minimum number of observations to estimate variability. Thus 228 individuals were used from S1. Of these, the majority was male (63%) and ages ranged from 18 to 26 (M=18.85, SD=1.12). The majority of participants identified as White (77.7%; 16.4% Asian; 5.4% Black; 8% multiracial).

Sample 2

Sample 2 (S2) consisted of 330 undergraduate students, recruited from introductory psychology courses at the University of Pittsburgh during the Fall 2018 semester. Participants were excluded from analyses if they had fewer than 10 total observations on the ambulatory assessment portion. Thus, 314 individuals were used from S2. Of these, the majority was female (61.7%) and ages ranged from 18 to 25 (M = 18.62, SD = .96). The majority of participants in S2 identified as White (85.9%; 11% identified as Asian; 5.1% as Black).

Sample 3

Sample 3 (S3) was comprised of community members (N=342) recruited during 2018 and 2019, both online through the University of Pittsburgh’s Clinical Translational Science Institute’s online participant registry (https://pittplusme.org) and through posted flyers for a study of personality and daily life. Several inclusionary criteria were implemented. To recruit a distinct community sample, only individuals who were not currently enrolled in a full-time undergraduate program were eligible. To ensure adequate representation of relevant personality features individuals were pre-screened using items from the NEO Personality Inventory – Revised (NEO-PI-R; Costa & McCrae, 1992) in a manner so as to maintain a 2-1-1 representation of low, moderate, and high levels of trait modesty (using published norm tertiles; <18, mid 18 – 21, and high ≥21) within each gender and the overall sample. Participants had to be at least 18 and less than 41 years of age. As before, participants with fewer than 10 total observations were excluded from analyses. Thus, 320 individuals were used for present analyses. Of these, the number of participants were roughly even between male and female (52% female) and the age range was 18 to 40 (M = 27.87, SD = 5.00). The majority of participants in S3 identified as White (87.5%; 8.8% identified as Asian; 4.1% as Black).

Procedure

In S1 participants came to an on-campus computer lab for training and assessment in groups of 20-30 participants. Participants were briefed on procedures and given a battery of self-report measures via the computer. After completing the in-person assessments, participants were trained to use software that was then installed on their smartphone. In S2 and S3, participants were trained using a self-administered online PowerPoint tutorial. Participants were required to complete several comprehension questions before continuing on with study procedures. Participants who did not show adequate comprehension were not eligible for further participation.

Participants then completed the ambulatory assessment portion of the study, which differed in length across the three samples. Participants completed up to 42 assessments in S1 (M = 32.38; SD = 7.99) over the course of the week (maximum of six surveys per day) between 10:00 and 22:00 each day. In S2, participants could complete up to 50 assessments (M =36.77; SD=7.45) with a maximum of five per day over ten days between 9:00 and 21:00 each day. In S3, participants could complete up to 70 assessments (M =55.08; SD =12.96) with a maximum of seven per day over ten days between 9:00 and 21:00 each day. Surveys were designed to appear at random times throughout the day with the stipulation that they had to be 90 minutes apart, and participants were prompted via push notification on their smartphones when a new survey was available. Once prompted to complete a survey, participants had 30 minutes to fill out the survey on the smartphone. Each assessment took 3-5 minutes to complete. For the ambulatory assessment portion of the study, compliance was high (78% compliance in Sample 1 [7,459 out of 9,576 total possible]; 74% compliance in Sample 2 [11,545 out of 15,700 total possible]; 79% compliance in Sample 3 [17,627 out of 22,400 total possible]).

In S1 participants completed both baseline questionnaires and the 7-day ambulatory assessment protocol for course credit. Full credit was given if participants completed 50% of the random surveys. Participation beyond this minimum amount was incentivized with random drawings for additional rewards (Apple watch, Nintendo Switch, Play Station 4), with chances of winning proportional to amount of the participation. In S2, participants completed both the baseline questionnaires and the 10-day ambulatory assessment protocol for course credit. Full credit was awarded to individuals who completed 60% or more of the 60 surveys during the study period. No partial credit was given. In S3, participants who completed baseline questionnaires received entry into prize drawings for $75 Amazon gift cards. After these questionnaires and a brief training presentation, participants were given the additional opportunity to participate in an ambulatory assessment study. Individuals who completed 90% or greater of the 80 surveys during the study period were given $100 Amazon gift cards. Gift cards of prorated value (e.g., $65 for 65% participation) were given to those who completed less than 90% of the surveys.

Measures

The Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory—Short Form (FFNI-SF; Sherman et al., 2015).

The FFNI-SF is a 60-item version of the original Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory (FFNI; Glover et al., 2012) that assesses narcissism across 15 different traits. These traits have been shown to tap the broad dimensions of grandiosity and vulnerability, as well as a three-factor structure of Extraversion, Antagonism, and Neuroticism. Participants rate the degree to which each statement captures them on a 5-point Likert scale (0 – Very Untrue of Me, 1 – Moderately Untrue of Me, 2 – Neither True nor Untrue of Me, 3 – Moderately True of Me, 4 – Very True of Me). Internal consistency for the FFNI was good (S1: Grandiosity McDonald’s ω =.92; Vulnerability ω = .82; Extraversion ω =.86; Antagonism ω =.90; Neuroticism ω =.89; S2: Grandiosity ω = .92; Vulnerability ω =.84; Extraversion ω =.86; Antagonism ω =.91; Neuroticism ω =.88; S3: Grandiosity ω =.89; Vulnerability ω = .87; Extraversion ω =.88; Antagonism ω =.90; Neuroticism ω =.90).

The Big Five Inventory – 2 (BFI-2; Soto & John, 2017).

The BFI-2 is a revised and updated version of the original Big Five Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava, 1999) which measures the Big Five domains of personality—Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Negative Emotionality, and Open-Mindedness (as well as 15 lower order facets). The BFI-2 contains 60 self-report items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 – Disagree Strongly; 1 – Disagree A Little; 2 – Neutral/No Opinion; 3 – Agree a Little; 4 – Agree Strongly). The BFI-2 was used in S1 and S3 of the current study. Internal consistency for the BFI-2 was good (S1: Extraversion ω = .86; Agreeableness ω = .80; Conscientiousness ω = .86; Negative Emotionality ω = .92; Open-Mindedness ω = .83; S3: Extraversion ω = .81; Agreeableness ω = .71 ; Conscientiousness ω = .79 ; Negative Emotionality ω = .86 ; Open-Mindedness ω = .75).

Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale (NGS; Crowe et al, 2016; Rosenthal et al, 2007; Rosenthal et al, 2020).

State level narcissistic grandiosity was assessed using a subset of adjectives from the NGS. The four adjectives with the highest factor loadings on a grandiosity factor in previous work (Edershile et al., 2019) were selected for the present study. These four adjectives were Glorious, Prestigious, Brilliant, and Powerful. Previous work has demonstrated that these four adjectives perform well as a measure of state narcissistic grandiosity (Edershile et al., 2019). These items were administered as part of the EMA survey with a 100-point sliding scale in which Not at all and Extremely were anchors. Reliability of the NGS was adequate (S1: ω within = .80; ω between = .97; S2: ω within = .74; ω between = .97; S3: ω within = .76; ω between = .96).

Narcissistic Vulnerability Scale (NVS; Crowe et al., 2018).

This measure consists of a set of 12 adjectives designed to assess narcissistic vulnerability and is meant as a complementary measure to the NGS. Similar to above, previous work has demonstrated that the NVS performs well as a state measure of narcissistic vulnerability (Edershile et al., 2019) and four adjectives with strongest loadings on vulnerability were selected: Underappreciated, Misunderstood, Ignored, and Resentful. These four adjectives were used in the current study. As above, these four items were administered as part of the EMA survey with a 100-point sliding scale in which Not at all and Extremely were anchors. Reliability of the NVS was adequate (S1: ω within = .78; ω between = .96; S2: ω within = .79; ω between = .98; S3: ω within = .80; ω between = .96).

Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965).

State level self-esteem was assessed using a subset of items from the 10-item Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965). Three items, all keyed in the positive direction (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) were selected and adapted for momentary assessment (e.g., “Right now, I feel that I have a number of good qualities”). Participants rated each of these three items on a 4-point Likert scale (0—Strongly Disagree; 3—Strongly Agree). Reliability of this three-item measure was adequate (S1: ω within = .80; ω between = .95; S2: ω within = .84; ω between = .98; S3: ω within = .85; ω between = .98).

Results

Due to the similarity of the procedure used for data collection across Sample 1, Sample 2, and Sample 3, and per the suggestion of reviewers, the datasets were combined into one data file. This approach is sometimes referred to as a “mega-analysis” (e.g., Fleeson & Gallagher, 2009) and can be used instead of a mega-analysis when all raw data are available for analysis. For results within each individual sample, please refer to the Supplementary Materials. In addition to results at the sample level, also, in Supplementary Material are the same analyses presented here but with the Pathological Narcissism Inventory instead. A summary of results will be presented in text. For complete results, please refer to the tables, figures, and Supplementary Material. Datasets, syntax, and codebooks can be found on https://osf.io/c9uea/

For basic descriptive statistics of the measures used, please refer to Supplementary Table 1.

Our data are hierarchically structured, such that momentary observations (Level 1) are nested within individuals (Level 2). As such, questions related to individual differences require analyses at the between-person level, which will involve many fewer observations than those at the within-person level. Because several of our questions involved individual differences, we powered the study (N=200 or more) to be able to detect a small population effect in a regression model (f2=.04) with alpha = .05 and beta = .80. This corresponds, roughly, to the average effect size from a recent review of personality and social psychology research (Gignac & Szodorai, 2016). These power analyses are informative for all questions related to gross variability and instability associations with dispositional narcissism scales, because these are fundamentally between-person associations (i.e., associations between standard trait narcissism scales with individual differences in the means and variances of EMA responses). It is common to calculate individual parameters for each of these within-person means and variances and treat them as individual difference variables, although here our use of multilevel models affords various benefits (e.g., adjusting for time in study and differential numbers of observations per person). Our stopping rule for Sample 1 and 2 were to collect as many participants as we could collect in one semester assuming it was higher than N=200. In addition, we sought to overshoot this goal by as much as possible given that participants with very low participation rates would not be able to meaningfully contribute to models of individual differences in variability. In the third sample, we sought higher power at the between-person level (N=300). However, given that we have shifted to presenting mega-analyses, with a substantially larger sample size (person N = 862), we have substantially more power to detect average or much smaller effects.

Associations between dispositional narcissism scales and inertia/cross-lagged analyses are effectively cross-level interactions, which are notoriously challenging to estimate a priori power for, because many assumptions must be made about within- and between-person effects. To evaluate power, we used Mathieu et al.’s (2012) simulation code as implemented in their shiny web-based application (https://aguinis.shinyapps.io/ml_power/). We used the results of the zero-order correlations and unconditional baseline inertia/cross-lagged models to estimate power to detect cross-level interactions. As with above, we assumed a cross-level effect size of approximately f2 =.04 with alpha = .05. We used the smallest observed sample size (S1) of N=228 and an average within-person sample size of 32 observations (i.e., 75% compliance), .35 as the association between dispositional narcissism and average momentary narcissism, and .65 as the ICC, and standardized variables. For the inertia effect, we assumed an autoregressive stability of .20 and a cross-lagged effect of .01, and this resulted in a power of .81 for both. Again, with the mega-analysis we have substantially higher power to detect these or smaller effects when samples are pooled.

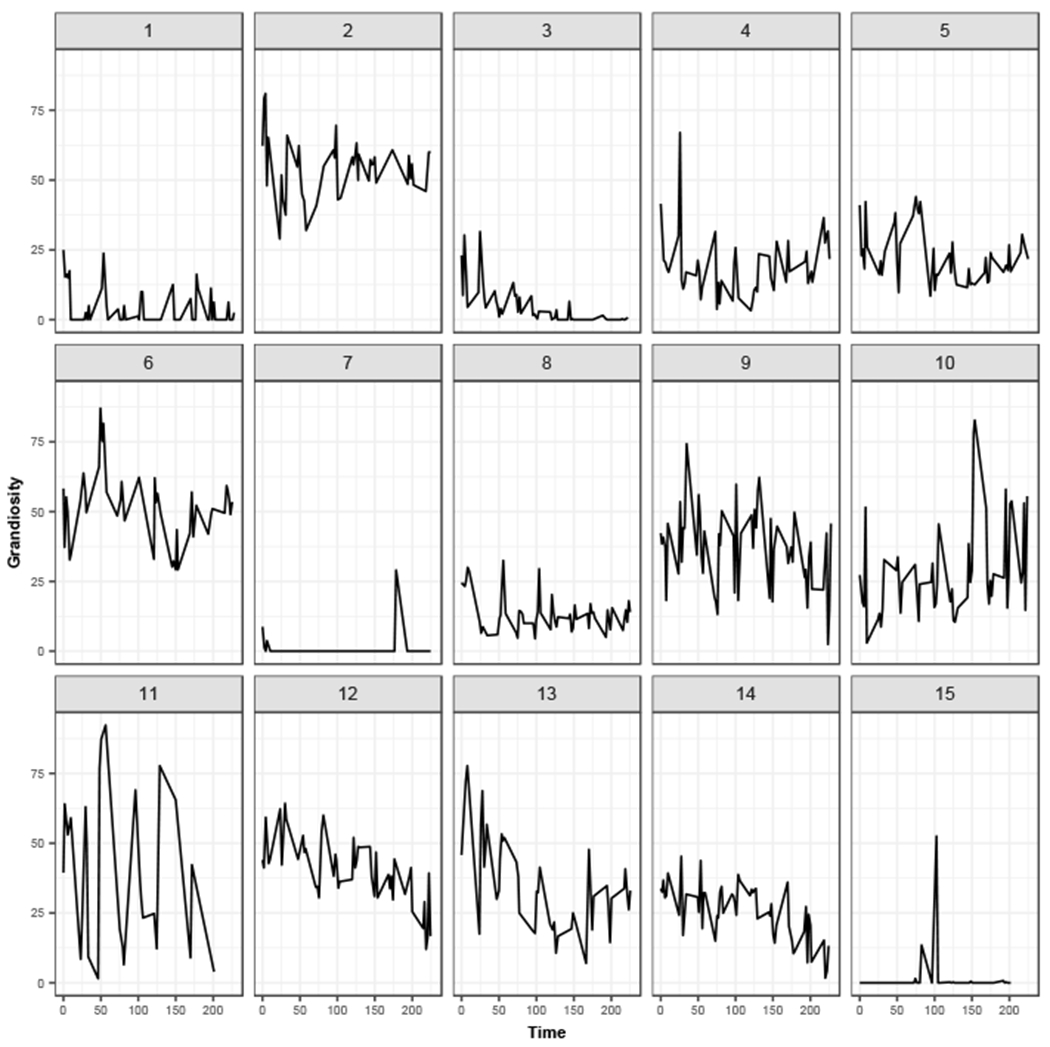

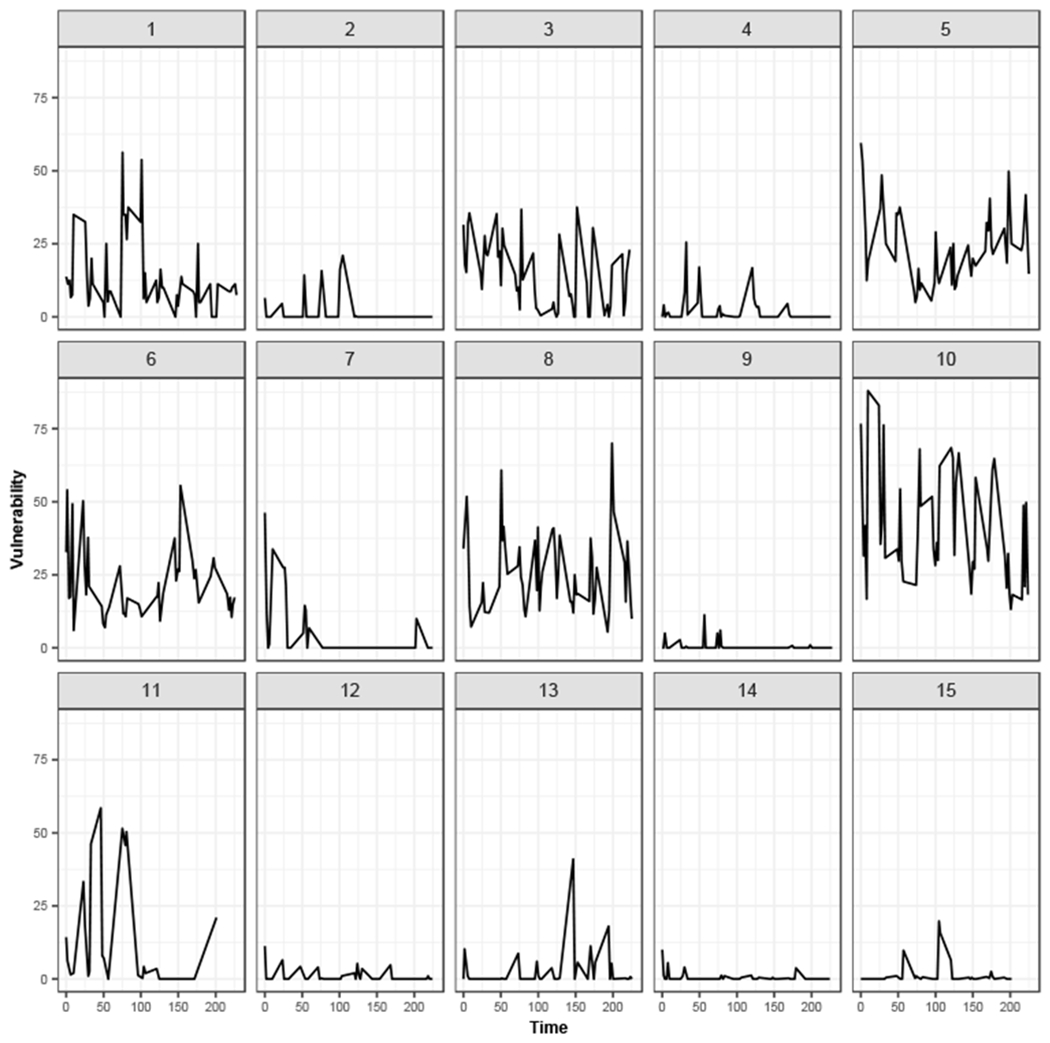

As a demonstration of the within-person variability and how it varies across participants, momentary reported scores of grandiosity and vulnerability for a subset of participants are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. The intraclass correlation (ICC) for momentary grandiosity is .72 mega-analytically (S1 is .72, .67 in S2, and .73 in S3). The ICC for momentary vulnerability is .59 mega-analytically (.64 in S1, .58 in S2, and .49 in S3). Thus, in all but S3 Vulnerability, the majority of the variance is at the between-person level. Nonetheless, there remains significant and substantial within-person variability in each scale in each sample.

Figure 1. Individual Variability of Momentary Grandiosity.

Note. Subset of S3 demonstrating individual variability of momentary grandiosity across time.

Figure 2. Individual Variability of Momentary Vulnerability.

Note. Subset of S3 demonstrating individual variability of momentary vulnerability across time.

The main results are organized by research question below, and details of the analysis for each question is presented alongside the first instance of the question. All models were estimated in Mplus Version 8.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2018). All analyses were run with the Bayesian Estimator function in Mplus. Therefore, resulting coefficient point estimates are the median of the posterior distribution, and we present the 95% credibility intervals as a measure of precision and to facilitate inferential tests (e.g., whether an effect was significantly different from 0).

1). Gross Variability: Broadly, how much do individuals vary in their levels of grandiosity and vulnerability across time?

Gross variability is a summary statistic of the dispersion of an individual’s states across time. Gross variability can be estimated by calculating each individual’s within-person standard deviation (iSD) or variance (i V AR) of grandiosity and vulnerability across time. Here, a multilevel modeling approach was adopted to evaluate gross variability, as it allows for each participant’s contribution to be weighted by how many responses they contributed. For instance, someone who only completed 11 entries would not have as reliable of a gross variability score as someone who had a complete set of 42 responses. Following Geukes and colleagues (2016), who used a similar approach in the study of self-esteem variability, multilevel models that relax the assumption of homogeneous level 1 (i.e., time-varying or within-person) residuals and allow for predictors of individual differences in momentary variation were used. That is, each individual is allowed to have a separate estimate of level 1 residuals (i.e., variability after accounting for the effect of any predictors), and these individual differences can be predicted by other individual difference variables. The higher-order dimensions of the FFNI – FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability for question (1a) and FFNI extraversion, FFNI antagonism, and FFNI neuroticism for question 1b – were used as predictors of individual differences in momentary variability. Additionally, these were estimated as multilevel structural equation models, which although conceptually similar to standard multilevel regressions used in this area, are more flexible and allow for the estimation of more complex path models (see e.g., Sadikaj et al., 2020 for a primer). The effect of time was included as a within-person predictor to adjust for potential linear trends in models estimated.

We present a simplified version of the model, using only momentary grandiosity as the outcome and the higher-order FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability scales as the trait predictors, to illustrate its specification. The full model also included momentary vulnerability as a parallel outcome, and was repeated with the FFNI three-factor higher-order solution and the PNI factors as predictors. The model was specified as follows,

where Grandiosityti represents the momentary assessments of grandiosity that vary across time (subscript t) and individuals (subscript i), β0i represents the random intercept that varies across individuals, εti reflects the momentary departures in grandiosity from each individuals intercept across time and participants, γ00 reflects the grand intercept or expected value when FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability are at 0, γ01 is the effect of FFNI grandiosity on individual differences in momentary grandiosity, γ02 is the effect of FFNI vulnerability on individual differences in momentary grandiosity, and u0i reflects the randomly varying residuals in intercepts. Multilevel models typically assume that the variance of within-person residuals (i.e., σ2ti) is constant across individuals. However, here that assumption was relaxed and σ2ti was allowed to vary across individuals and as a function of FFNI scores. Values of variances need to be positive, which is achieved by using an exponential function when modeling the variance. Here γ10 represents the average variability score when FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability are 0, γ11 is the effect of FFNI grandiosity on individual differences in variability, γ12 is the effect of FFNI vulnerability on individual differences in variability, γ13 is the effect of the mean of grandiosity on individual differences in variability, γ14 is the effect of the mean of vulnerability on individual differences in variability, and u1i reflects residual individual differences in variability.

Currently there is a debate in the literature about how associations between individual differences in variability of momentary scores and within-person means of those same scores should be interpreted. Many argue that positive associations between within-person means and variability merely reflect that people with higher means have more room to vary, and thus this relationship is artifactual (e.g., Baird et al., 2006; Kalokerinos et al., 2020). In particular, it is argued that individual means and standard deviations are associated due to floor or ceiling effects that artificially constrain the variance for individuals close to the boundary. Baird and colleagues (2006) demonstrated that even when means and standard deviations are independent, when distributions are skewed (as is often the case with narcissism variables), associations between the means and standard deviations become an artifact of the analyses. As a result, it is possible that associations between variability in narcissistic states and predictors designed to assess average levels of narcissism (e.g., FFNI scores) may emerge due to non-substantive reasons. Given this, person-mean levels of grandiosity and vulnerability were included as covariates, and the relationship between dispositional narcissism scores and variability in narcissistic states adjusting for each individual’s mean level of momentary reports was examined. However, we first examined zero-order correlations among all variables to fully understand the associations among the variables.

1a. Does an individual’s level of dispositional grandiosity and vulnerability associate with their momentary level and variability in state grandiosity and vulnerability.

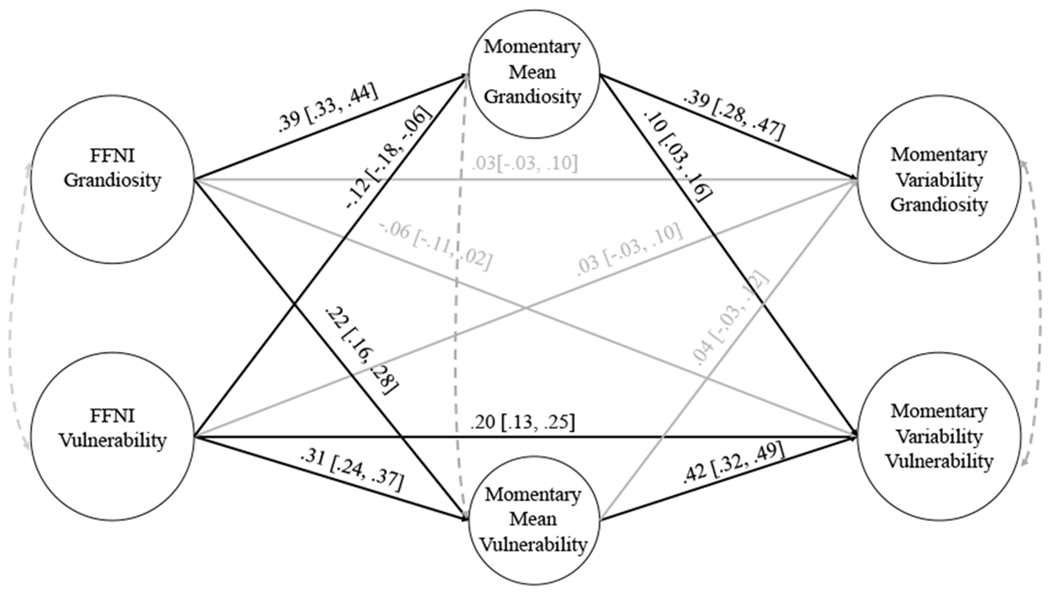

Table 1 shows the correlations among FFNI grandiosity and vulnerability, momentary means in grandiosity and vulnerability, and gross variability. Please note, this table also contains all correlations performed for the present study. As such, we will refer to it in later results as well. Figure 3 illustrates the path analysis model designed to examine associations among FFNI two-factor scores and gross variability accounting for the mean of momentary grandiosity and vulnerability.

Table 1.

Mega-analytic between-person correlations among all variables for which Gross Variability was examined.

| Measure | Variable | Momentary Variables | FFNI | Big-5 Personality | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grandiosity | Vulnerability | Self-Esteem | Two-Factor Structure | Three-Factor Structure | ||||||||||||

| Momentary Mean | Variability | Momentary Mean | Variability | Momentary Mean | Variability | FFNI-G | FFNI-V | FFNI-E | FFNI-A | FFNI-N | Openness | Conscientiousness | Extraversion | Agreeableness | ||

| Momentary Variables | ||||||||||||||||

| Grandiosity | Momentary Mean | - | ||||||||||||||

| Variability | .41 [.32, .46] | - | ||||||||||||||

| Vulnerability | Momentary Mean | .28 [.21, .34] | .17 [.09, .23] | - | ||||||||||||

| Variability | .18 [.12, .24] | .37 [.25, .44] | .51 [.40, .56] | - | ||||||||||||

| Self-Esteem | Momentary Mean | .34 [.27, .39] | .12 [.05, .19] | −.30 [−.36, −.24] | −.25 [−.31, −.17] | - | ||||||||||

| Variability | −.01 [−.08, .05] | .29 [.21, .35] | .21 [.16, .27] | .38 [.31, .43] | −.30 [−.37, −.24] | - | ||||||||||

| FFNI | ||||||||||||||||

| Two-Factor Structure | FFNI-G | .37 [.32, .43] | .19 [.11, .26] | .25 [ .18, .31] | .11 [.04, .17] | .10 [.03, .17] | .03 [−.03, .10] | - | ||||||||

| FFNI-V | −.08 [−.15, −.01] | .01 [−.07, .08] | .33 [.26, .38] | .32 [.24, .38] | −.48 [−.53, −.42] | .26 [.20, .31] | .10 [.04, .16] | - | ||||||||

| Three-Factor Structure | FFNI-E | .34 [.29, .40] | .26 [.19, .33] | .12 [.06, .18] | .04 [−.02, .10] | .18 [.12, .25] | .03 [−.04, .09] | .77 [.74, .79] | .06 [−.02,.11] | - | ||||||

| FFNI-A | .28 [.22, .34] | .12 [.05, .19] | .36 [.29, .41] | .21 [.15, .27] | −.12 [−.18, −.06] | .10 [.02, .16] | .85 [.82, .86] | .44 [.38, .49] | .42 [.36, .47] | - | ||||||

| FFNI-N | −.20 [−.26, −.13] | −.03 [−.11, .04] | .17 [.11, .24] | .21 [.14, .27] | −.45 [−.51, −.40] | .24 [.18, .30] | −.28 [−.34, −.23] | .78 [.74, .80] | −.10 [−.16, −.04] | −.03 [−.09, .04] | - | |||||

| Big-5 Personality | ||||||||||||||||

| Openness | .02 [−.06, .12] | .03 [−.06, .12] | −.12 [−.21, −.05] | .00 [−.07, .08] | .16 [.07, .24] | −.04 [−.11, .06] | .01 [−.09, .09] | −.08 [−.17, −.00] | .18 [.09, .27] | −.12 [−.21, −.04] | −.02 [−.11, .06] | - | ||||

| Conscientiousness | .02 [−.07, .10] | .05 [−.03, .15] | −.21 [−.29, −.13] | −.12 [−.20, −.03] | .30 [.22, .37] | −.12 [−.21, −.05] | −.16 [−.25, −.06] | −.31 [−.39, −.24] | .04 [−.03, .13] | −.31 [−.39, −.22] | −.20 [−.28, −.12] | .09 [.00, .17] | - | |||

| Extraversion | .32 [.24, .39] | .27 [.17, .34] | −.06 [−.15, .02] | −.02 [−.12, .05] | .38 [.30, .45] | −.11 [−.19, −.03] | .42 [.35, .49] | −.28 [−.37, −.18] | .60 [.55, .65] | .12 [.04, .21] | −.32 [−.39, −.23] | .21 [.12, .29] | .25 [.17, .34] | - | ||

| Agreeableness | −.01 [−.11, .09] | −.03 [−.12, .08] | −.28 [−.37, −.20] | −.18 [−.26, −.10] | .26 [.19, .36] | −.11 [−.21, −.03] | −.40 [−.46, −.32] | −.42 [−.48, −.33] | −.08 [−.16, −.00] | −.63 [−.68, −.67] | −.07 [−.17, .02] | .17 [.09, .27] | .28 [.19, .36] | .08 [−.00, .16] | - | |

| Neuroticism | −.18 [−.27, −.10] | −.04 [−.15, .05] | .31 [.22, .38] | .32 [.24, .39] | −.54 [−.59, −.49] | .29 [.22, .36] | −.15 [−.26, −.05] | .69 [.63, .73] | −.14 [−.24, −.05] | .14 [.04, .24] | .67 [.61, .71] | −.03 [−.10, .05] | −.28 [−.35, −.21] | −.28 [−.35, −.19] | −.26 [−.34, −.17] | |

Note. N=862. Bolded values represent those in which the credibility interval did not contain zero. FFNI-G = Five Factor Narcissism Inventory-Grandiosity; -V = Vulnerability; -E = Extraversion; -A = Antagonism; -N = Neuroticism; FFNI-G = Five. Please note, some correlations were estimated in multiple models. The first correlation presented in text is presented here (however all values were similar). Most values are drawn from a mega-analysis across Sample 1, Sample 2, and Sample 3. Estimates from associations with the Big-5 are from a mega-analysis of Sample 1 and Sample 3 (The BFI-2 was not given in Sample 2).

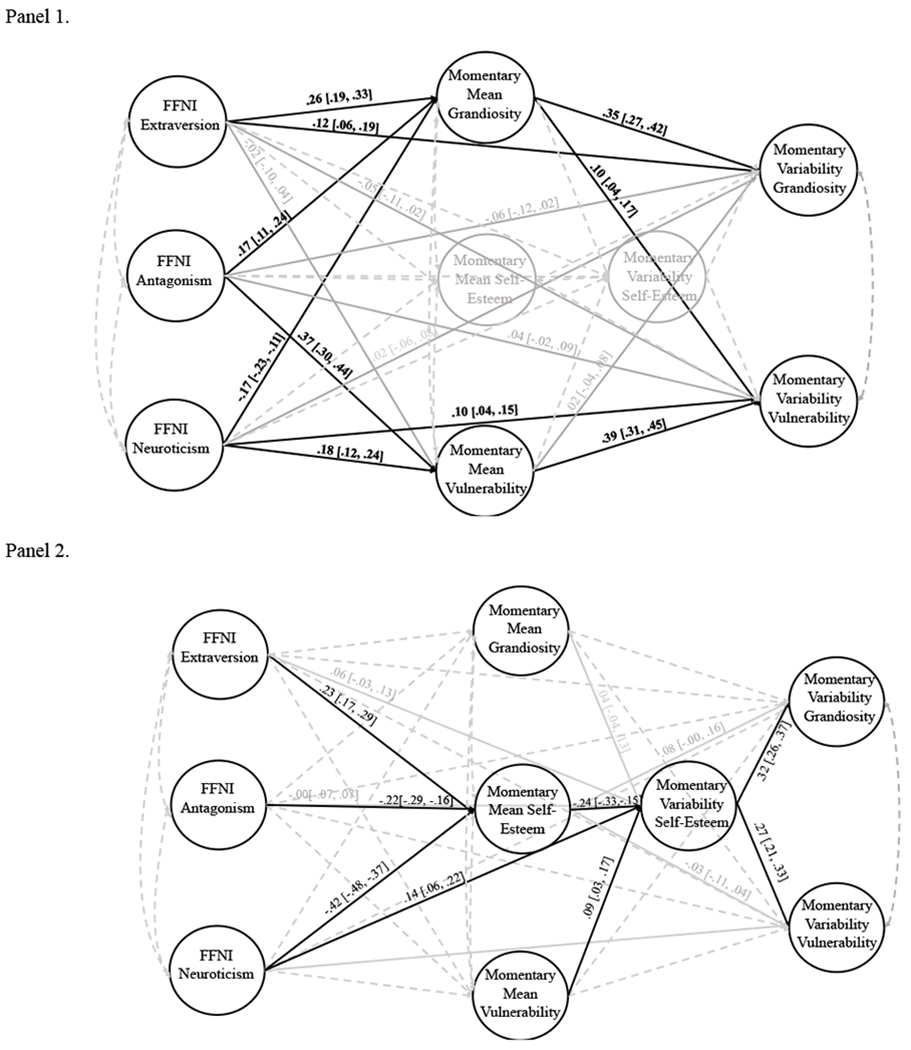

Figure 3. Between-person path model using dispositional narcissism and mean level as predictors for average level variability across grandiosity and vulnerability.

Note. Mega-analytic results N=862. Bolded values are those in which the credibility interval did not contain zero. Mean grandiosity and mean vulnerability were correlated at .26 [.19, .31], variability of grandiosity and variability of vulnerability were corelated at .35 [.21, .42]. FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability are correlated at .09 [.03, .16]. FFNI = Five Factor Narcissism Inventory.

Starting with the associations between the dispositional FFNI scales and individual differences in momentary means, FFNI scale scores were moderately significantly correlated with same domain momentary means (e.g., FFNI grandiosity with momentary mean of grandiosity), and effect sizes were similar once accounting for shared variance in dispositional scores in the path-analytic model. FFNI grandiosity was moderately significantly correlated with the momentary mean of vulnerability, and effects were similar in the path-analytic model. Dispositional vulnerability was modestly negatively correlated with the momentary mean of grandiosity, and the effect was similar in the path analytic model.

Moving to the primary question of the association between dispositionally assessed narcissism and fluctuation in states, dispositional grandiosity scores were modestly positively significantly correlated with gross variability in grandiosity, though the significance of this effect did not hold when adjusting for dispositional vulnerability and momentary means in the path analysis. Dispositional vulnerability scores were moderately significantly correlated with variability in vulnerability and remained a modest significant predictor once adjusting for dispositional grandiosity and momentary means. Moving to cross-domain associations, dispositional grandiosity was modestly positively significantly correlated with variability in vulnerability but virtually unassociated in the path analysis. Dispositional vulnerability was not significantly associated with gross variability in grandiosity either in correlations or path analysis.

In both correlations and the path analysis model, momentary mean levels were moderately to strongly positively associated with gross variability in the matched dimension (e.g., momentary mean of grandiosity and variability in grandiosity). For both domains, somewhat smaller correlations were observed across domains between momentary means and variability. These associations were further reduced in the path analysis.

1b. Does a three-factor structure of narcissism (i.e., entitlement, exhibitionistic grandiosity, vulnerability) associate with momentary level and variability in state grandiosity and vulnerability?

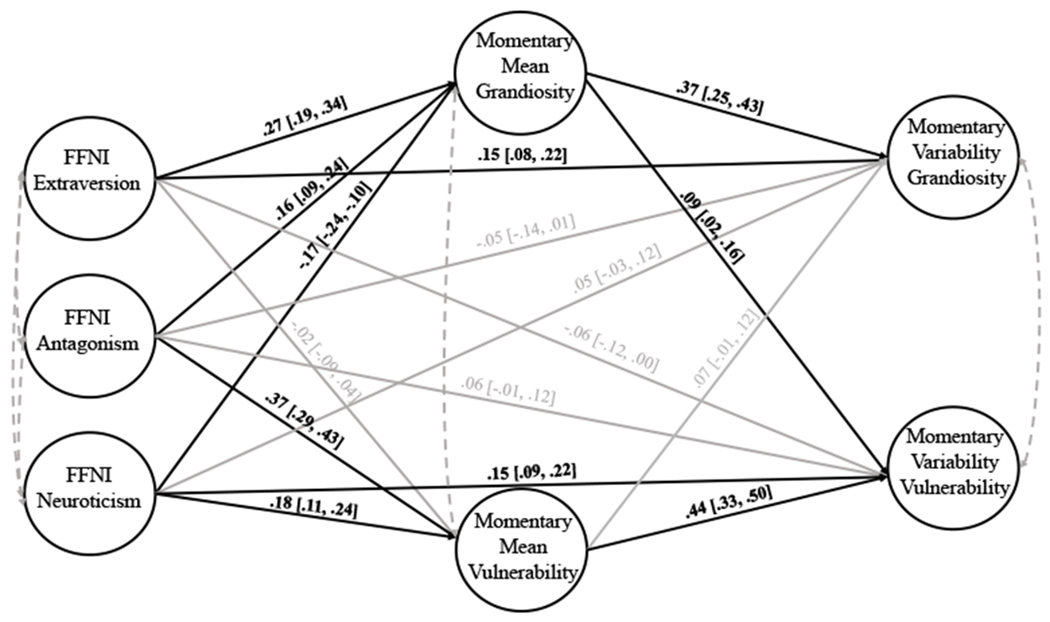

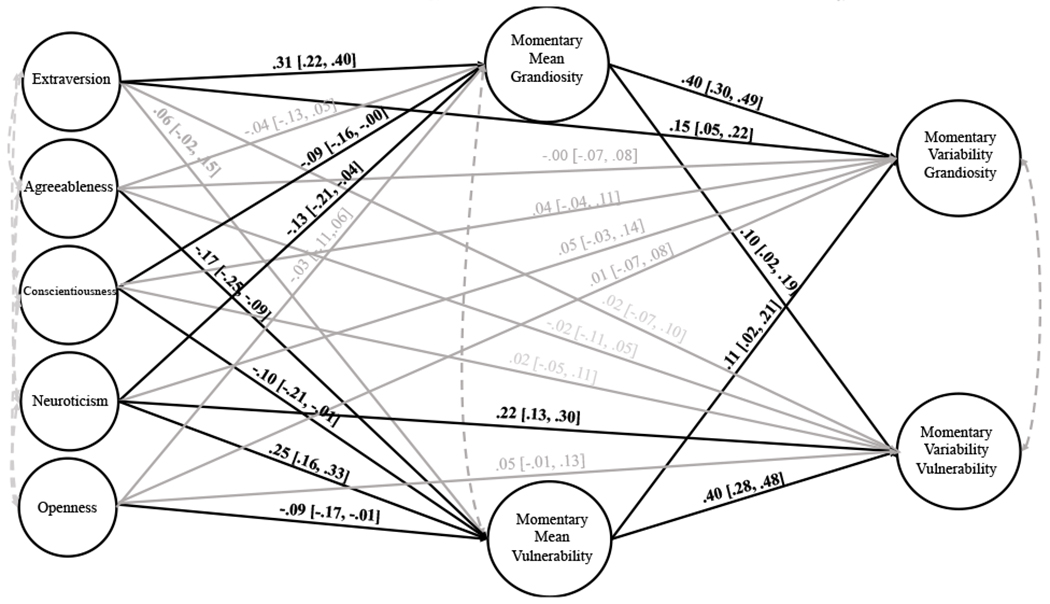

Table 1 shows the correlations among FFNI three-factor structure, momentary means in grandiosity and vulnerability, and gross variability. Figure 4 illustrates the path analysis model estimating the associations among FFNI three-factor scores and gross variability accounting for the mean of momentary grandiosity and vulnerability.

Figure 4. Between-person path model using dispositional narcissism and mean level as predictors for average level variability across grandiosity and vulnerability.

Note. N = 862. Bolded values are those in which the credibility interval did not contain zero. Mean grandiosity and mean vulnerability were correlated at .25[.19, .32], variability of grandiosity and variability of vulnerability were corelated at .36 [.20, .42]. FFNI extraversion and FFNI neuroticism were correlated at −.09 [−.15, −.03]. FFNI extraversion with FFNI antagonism .42 [.36, .46]. FFNI Antagonism and FFNI Neuroticism were correlated at −.03 [−.10, .04]. FFNI = Five Factor Narcissism Inventory.

Examining associations between the dispositional three-factor FFNI scales and individual differences in momentary means, FFNI extraversion and FFNI antagonism were moderately significantly positively associated with the momentary mean of grandiosity, and these effects were similar in the path-analysis. On the other hand, FFNI neuroticism was moderately significantly negatively correlated with the momentary mean of grandiosity and this effect was also similar in the path analysis. All FFNI subscales were significantly positively correlated with the momentary mean of vulnerability, with the strongest association between FFNI antagonism and the momentary mean of vulnerability. However, in the path analytic model only FFNI antagonism and FFNI neuroticism significantly predicted the momentary mean of vulnerability, but the association between FFNI extraversion and the momentary mean of vulnerability was not significant.

Moving to the primary question of the association between dispositionally assessed narcissism using a three-factor structure and fluctuation in states, FFNI extraversion and FFNI antagonism were both moderately positively and modestly positively associated with variability in grandiosity, respectively, in the zero-order correlations. In the path analytic model, only FFNI extraversion yielded a modest positive significant association with variability in grandiosity. All other paths between FFNI scores and variability in grandiosity were non-significant. FFNI neuroticism and antagonism were moderately positively correlated with variability in vulnerability in the zero-order associations, but only the association between FFNI neuroticism and variability in vulnerability maintained in the path-analytic model.

Associations between momentary means and variability followed a very similar patterns to those in the model using a two-factor structure of narcissism.

2). Instability: how much do individuals change in their levels of grandiosity and vulnerability form one time point to the next?

Whereas gross variability summarizes the dispersion in scores without considering temporal ordering, instability is a metric that summarizes the average magnitude of change from one moment to the next. Instability is often calculated as each individual’s mean squared successive differences (iMSSD) between consecutive narcissism scores. However, a multi-level modeling framework was adopted to examine instability, by taking the squared differences between consecutive scores in grandiosity and vulnerability at successive time points and using these difference scores as outcomes (Jahng et al., 2008). Missing values were inserted between the last observation of one day and the first observation of the next so that difference scores reflected changes in narcissistic states within a day. The FFNI scales (2a) two-factor and 2b) three-factor structure) were used as predictors of individual differences (i.e., the random intercepts) in squared successive differences (SSD) in grandiosity and vulnerability.

A simplified example of the model specification is given with SSD grandiosity and the two-factor FFNI scales, but SSD vulnerability was included as an additional outcome in all models, and these were repeated as with the three-factor FFNI and PNI. The model was specified as follows,

where SSD grandiosityti represents the SSDs for grandiosity that vary across time (subscript t) and individuals (subscript i), β0i represents the random intercept of SSD grandiosity that varies across individuals, εti reflects the momentary departures in SSD grandiosity from each individuals intercept across time and participants, γ00 reflects the grand intercept or expected value of SSD grandiosity when FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability are 0, γ01 is the effect of FFNI grandiosity on individual differences in SSD grandiosity, γ02 is the effect of FFNI vulnerability on individual differences in SSD grandiosity, and u0i reflects the randomly varying residuals in intercepts.

2a. Does an individual’s level of dispositional grandiosity and vulnerability predict their occasion to occasion difference scores in state grandiosity and vulnerability?

Results of the instability analyses at the between-person level for the two-factor FFNI can be found in Table 2. FFNI grandiosity was moderately positively associated with grandiosity SSD. These positive associations maintained once adjusting for the shared variance in FFNI vulnerability. Dispositional vulnerability was moderately positively associated with vulnerability SSD and remained moderately positively associated once accounting for dispositional grandiosity. Dispositional vulnerability was modestly positively associated with grandiosity SSD in the correlation model but this association became non-significant in the adjusted model. Dispositional grandiosity was modestly positively associated with vulnerability SSD in both the correlation and adjusted model.

Table 2.

Zero order correlation and regression paths of instability at the between-person level-Mega analytic results

| Measure | Squared Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grandiosity | Vulnerability | |||

| r | β | r | β | |

| FFNI-G | .20 [.13, .27] | .19 [.13, .27] | .14 [.05, .20] | .11 [.04, .20] |

| FFNI-V | .07 [.01, .14] | .05 [−.02, .12] | .26 [.19, .34] | .25 [.19, .32] |

Note. N=862. The squared difference variables were regressed on the FFNI. FFNI= Five Factor Narcissism Inventory; G = Grandiosity; V = Vulnerability. Bolded values are those for which the credibility interval did not contain zero. Squared Successive Differences of Grandiosity and Vulnerability were correlated at .44[.36, .49].

2b. Does an individual’s level of entitlement, exhibitionistic grandiosity, or vulnerability predict their occasion to occasion difference scores in state grandiosity and vulnerability?

Results of the instability analyses at the between-person level for the three-factor FFNI can be found in Table 3. FFNI extraversion and antagonism were modestly positively associated with grandiosity SSD in both the correlation and adjusted models. Dispositional neuroticism was not significantly associated with grandiosity SSD in either the correlation of adjusted model. Dispositional neuroticism and antagonism were modestly positively associated with vulnerability SSD. Dispositional extraversion was associated with vulnerability in the correlation model but this association was near zero in the adjusted model.

Table 3.

Zero order and regression paths of instability at the between-person level-Mega analytic results

| Measure | Squared Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grandiosity | Vulnerability | |||

| r | β | r | β | |

| FFNI-Extraversion | .19 [.10, .26] | .16 [.09, .23] | .10 [.03, .16] | .03 [−.04, .10] |

| FFNI-Antagonism | .17 [.09, .25] | .11 [.04, .18] | .20 [.14, .26] | .20 [.12, .28] |

| FFNI-Neuroticism | .01 [−.05, .09] | .03 [−.03, .10] | .17 [.11, .23] | .18 [.12, .24] |

Note. N = 862. The squared difference variables were regressed on the FFNI. FFNI= Five Factor Narcissism Inventory. Squared Successive Differences of grandiosity and vulnerability were correlated at .43. Bolded values are those for which the credibility interval did not contain zero.

3). Inertia and Cross-lagged effects: how stable are grandiose and vulnerable states?

Inertia is a metric that quantifies the degree to which a previous state level predicts the current state level (i.e., autoregression). Accordingly, it indicates how long a person tends to stay in a state or how quickly a person returns to baseline after being perturbed. Conceptually, inertia can be understood as how well a person is able to regulate themselves. In most psychological data, the value ranges between 0 and 1 (although they can be negative), and the closer it is to 1, the longer it takes a person to return to his/her baseline. An individual with high grandiosity inertia has grandiose states that are more self-predictive across time, and which tend to ramp up and diminish more slowly over time. Conversely, an individual who is prone to unpredictable oscillations will have a lower inertia than someone who either stays constant from one point to the next or someone who predictably fluctuates between states.

In addition, we were interested in whether one’s level of narcissistic grandiosity (or vulnerability) at one point in time predicted one’s level of vulnerability (or grandiosity) at the next. These “cross-state” effects best reflect certain theoretical propositions related to shifting between narcissistic states. For instance, that grandiosity reflects a defensive reaction to vulnerable states (e.g., Ronningstam, 2009), and alternatively whether fragile grandiosity predicts tumbling down into a vulnerable state (e.g., Horowitz, 2009). To evaluate the effect of one narcissistic state on the other between time points, we estimated cross-lagged effects from one time-point to the next, adjusting for the prior time-points state (e.g., predicting grandiosity at time t from vulnerability and grandiosity at time t-1). This can be understood as the effect of one’s standing on one narcissistic dimension predicting change in the other over time.

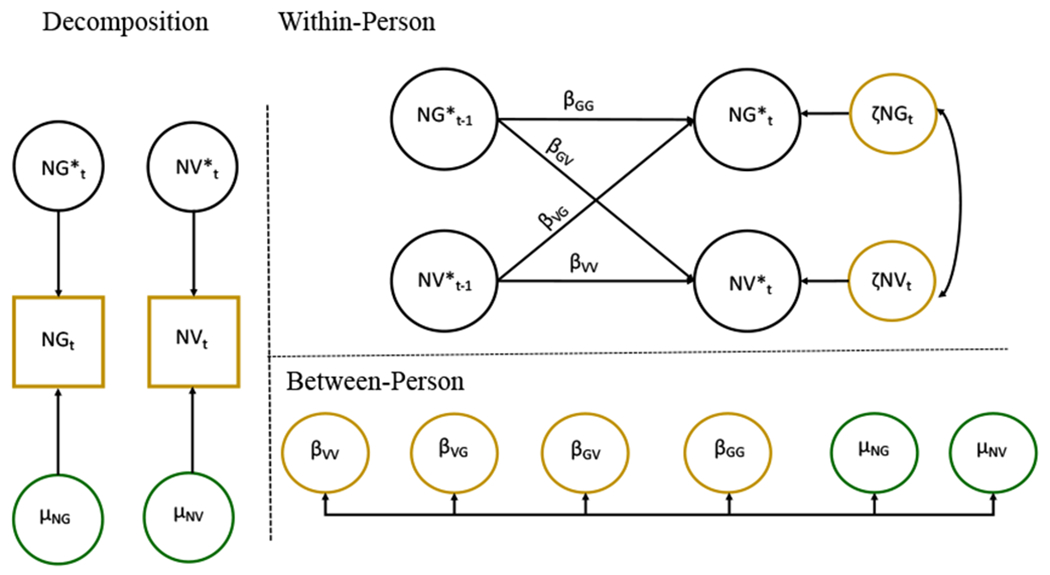

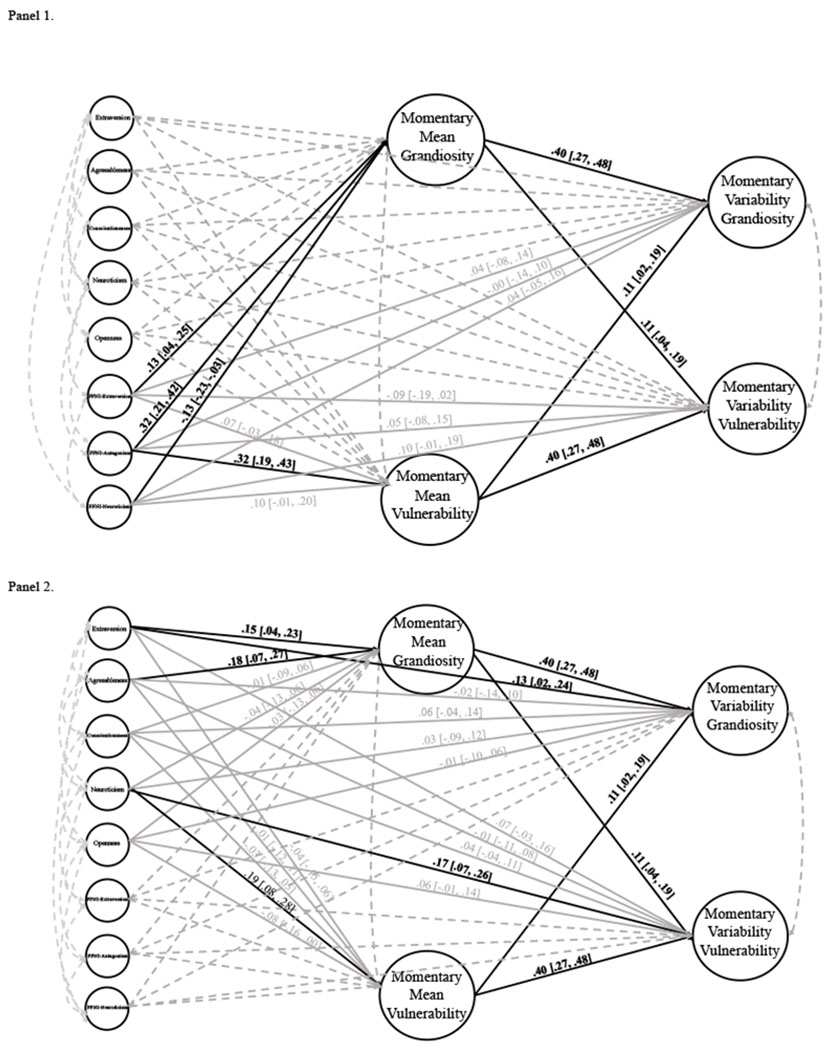

Figure 5 illustrates the basic model. Within-person coefficients (e.g., βGG, βGV) estimates how strongly previous states of grandiosity and vulnerability (t-1) predict current states of grandiosity and vulnerability (t). The between-person random effects reflect individual differences in the strength of the autoregressive effects. Both the autoregressive inertia (e.g., βGG) and cross-lagged state shifting effects (e.g., βGV) were estimated simultaneously using Dynamic Structural Equation Modeling (DSEM; e.g., Asparouhov et al., 2017, 2018), which combines multilevel modeling, structural equation modeling, and time series analysis. As with above, models were calculated using the Bayesian estimator. Then the FFNI scales—both the (3a) two-factor and (3b) three-factor structure—were included as predictors of individual differences of the autoregressions and cross-lagged effects. The effect of time was included as a within-person predictor to adjust for potential linear trends in models estimated.

Figure 5. Proposed model of inertia at the between and within person level.

Note. NG = Narcissistic Grandiosity; NV = Narcissistic Vulnerability. The left panel shows the decomposition of observed variables (rectangles) into their latent within-person (top circles) and between-person (bottom circles) components.

As above, though models included both grandiosity and vulnerability, for simplicity of illustrating the basic model features, only grandiosity is shown below. The models were also run with both the three-factor FFNI scales and the PNI scales as predictors.

where Grandiosityti represents the momentary assessments of grandiosity that vary across time (subscript t) and individuals (subscript i), β0i represents the random intercept that varies across individuals, β1i(Gt-1i) represents the effect of grandiosity at the previous time point (t-1) that varies across individuals (i.e., a random slope), εti reflects the momentary departures in grandiosity from each individual’s intercept across time and participants, γ00 reflects the grand intercept or expected value of grandiosity when FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability are 0 and an individual’s mean grandiosity at t-1, γ01 is the effect of FFNI grandiosity on individual differences in momentary grandiosity, γ02 is the effect of FFNI vulnerability on individual differences in momentary grandiosity, and u0i reflects the randomly varying residuals in intercepts, γ10 reflects the average effect of grandiosity at t-1 when FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability are 0, γ11 is the effect of FFNI grandiosity on individual differences in inertia, γ12 is the effect of FFNI vulnerability on inertia, and u1i reflects the randomly varying residuals in slopes.

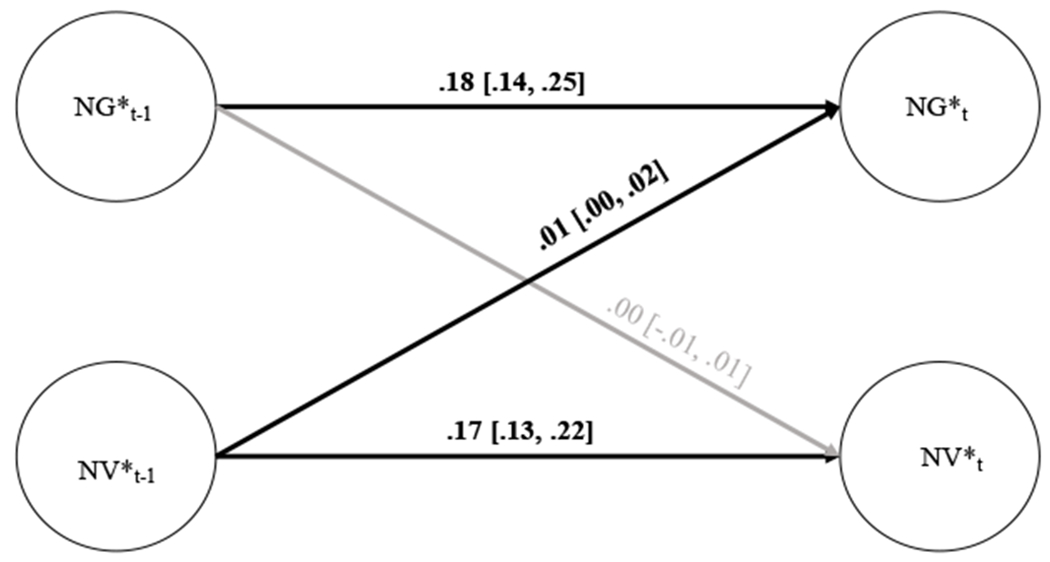

3a. Does one’s current level of grandiosity and vulnerability predict future levels of states in the same domain (e.g., grandiosityt-1 → grandiosityt) and/or the other domain (e.g., grandiosityt-1 → vulnerabilityt)?

Within-person results of auto-regressive and cross-lagged effects of a baseline unconditional model (i.e., without level 2 predictors) can be found in Figure 6. We observed a significant positive fixed effect (i.e., average within-person effect) of inertia for both grandiosity and vulnerability. These effects were modest, although we also found a significant random effect such that individuals differed significantly in their level of inertia. Cross-lagged fixed effects yielded very small associations, though, due to the number of observations, the effect between momentary vulnerability at t-1 predicting change in grandiosity from t-1 to t was significant despite its very modest value. However, as with the auto regressive effects, significant random effects indicated that individuals differed in the strength of these paths.

Figure 6. Within-person results of inertia.

Note. N=862. NG= Narcissistic Grandiosity; NV= Narcissistic Vulnerability.

3b. Does dispositional grandiosity and vulnerability predict getting “stuck in states” (e.g., grandiosityt-1 → grandiosityt) or switching states (e.g., grandiosityt-1 → vulnerabilityt)

Between-person results of the associations between the FFNI scale scores and the autoregressive and cross-lagged effects can be found in Table 4. With the exception of the effect of FFNI vulnerability on vulnerability inertia, no associations between dispositional scales and individual differences in these lagged momentary associations were observed.

Table 4.

Mega-Analytic Results of multilevel regression results of inertia at the between person level for the FFNI Two-Factor structure

| Measure | β G→G | β V→V | β V→G | β G→V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFNI Grandiosity | −.02 [−.08, .04] | −.04 [−.10, .02] | −.03 [−.11, .05] | .00 [−.11, .10] |

| FFNI Vulnerability | −.06 [−.12, .01] | .16 [.09, .22] | −.05 [−.15, .03] | .05 [−.03, .14] |

Note. N= 862. Bolded values are those for which the credibility interval did not contain zero. Values on the right predicted column headings. FFNI=Five Factor Narcissism Inventory.

3c. Does a dispositional three-factor structure of narcissism associate with Inertia and Cross-lagged effects of state level grandiosity and vulnerability?

Between-person results of the autoregressive effects using the three-factor structure of the FFNI can be found in Table 5. With the exception of the effect of dispositional neuroticism predicting the lagged effect of prior vulnerable states predicting current vulnerability states, no associations between dispositional scales and individual differences in these lagged momentary associations emerged.

Table 5.

Mega-analytic Results of multilevel regression results of inertia at the between person level for the FFNI Three-factor structure

| Measure | β G→G | β V→V | β V→G | β G→V |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FFNI Extraversion | .04 [−.03, .12] | .−.04 [−.10, .03] | .03 [−.07, .13] | .04 [−.07, .15] |

| FFNI Neuroticism | −.06 [−.12, .01] | .12 [.06, .17] | −.05 [−.13, .04] | .06 [−.03, .15] |

| FFNI Antagonism | −.07 [−.15, .01] | .05 [−.01, .12] | −.08 [−.18, .03] | −.01 [−.10, .09] |

Note. N=862. Bolded values are those for which the credibility interval did not contain zero. Values on the right predicted column headings. FFNI = Five Factor Narcissism Inventory.

4). How much do individuals vary in their self-esteem over time as a function of narcissism?

In questions 1-3, we examined different patterns of variability between dispositional narcissism (both with a two-factor structure and three-factor structure) and fluctuations in state-level grandiosity and vulnerability. Though such models were designed to examine theorized fluctuations in grandiosity and vulnerability, it is possible that observed fluctuations in narcissism are a consequence of a different psychological process. Thus, in the following models, we examine associations between dispositional narcissism and fluctuations in state-level self-esteem.

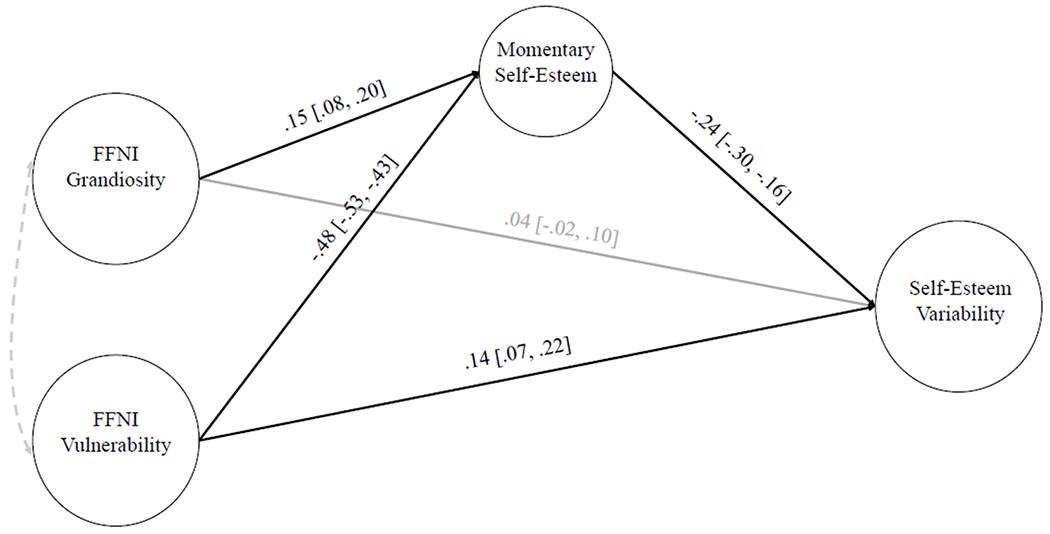

4a. Does an individual’s level of dispositional grandiosity and vulnerability predict their state self-esteem level and variability?

Gross Variability associations between dispositional narcissism two-factor structure and momentary self-esteem and self-esteem variability can be found in Table 1 (zero-order associations) and Figure 7 (adjusted path-analytic model). FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability were modestly positively and strongly negatively correlated with the momentary mean of self-esteem, respectively. These associations were similar in the adjusted model after correcting for the shared variance in grandiosity and vulnerability.

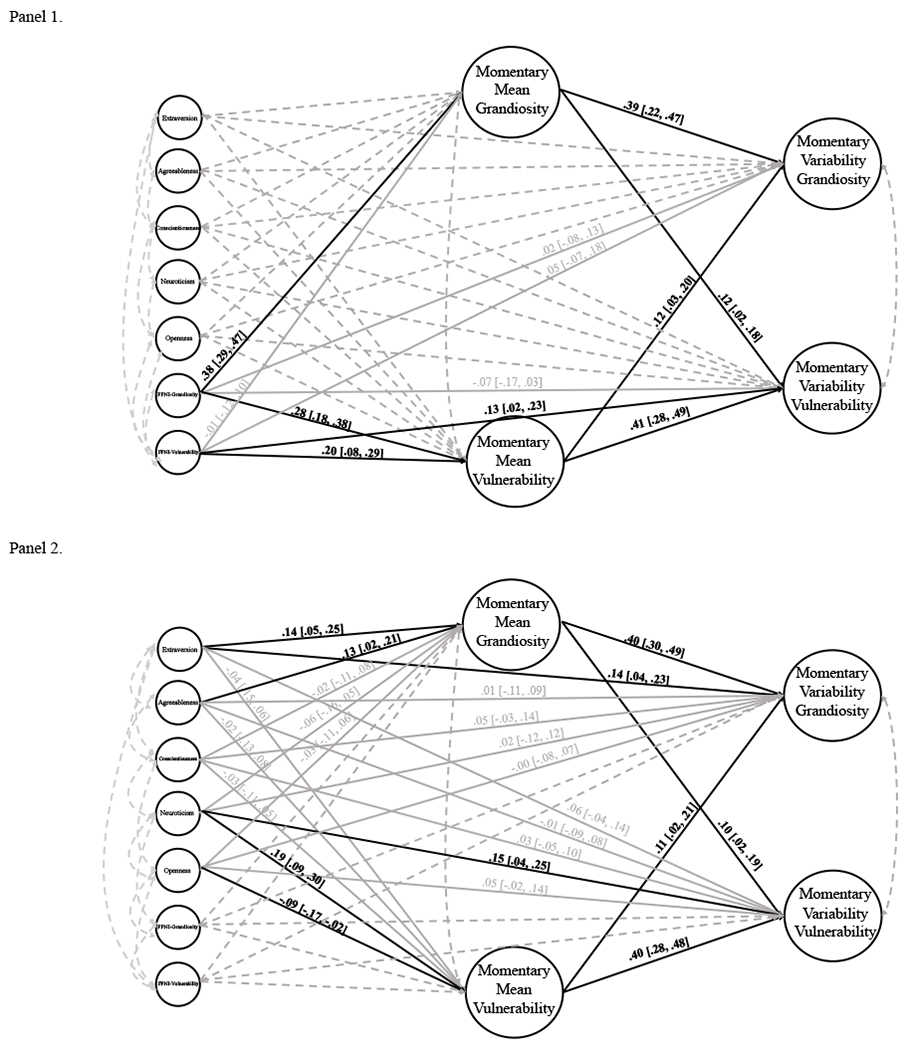

Figure 7. Mega-Analytic Findings for fluctuations between baseline narcissism and momentary self-esteem.

Note. N = 862. FFNI = Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory. FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability are correlated at .09 [.04, .16].

Moving to associations between fluctuation in self-esteem and dispositional grandiosity and vulnerability, only dispositional vulnerability emerged as a significant positive predictor of fluctuation in self-esteem. Associations were in the same direction but attenuated in the adjusted model.

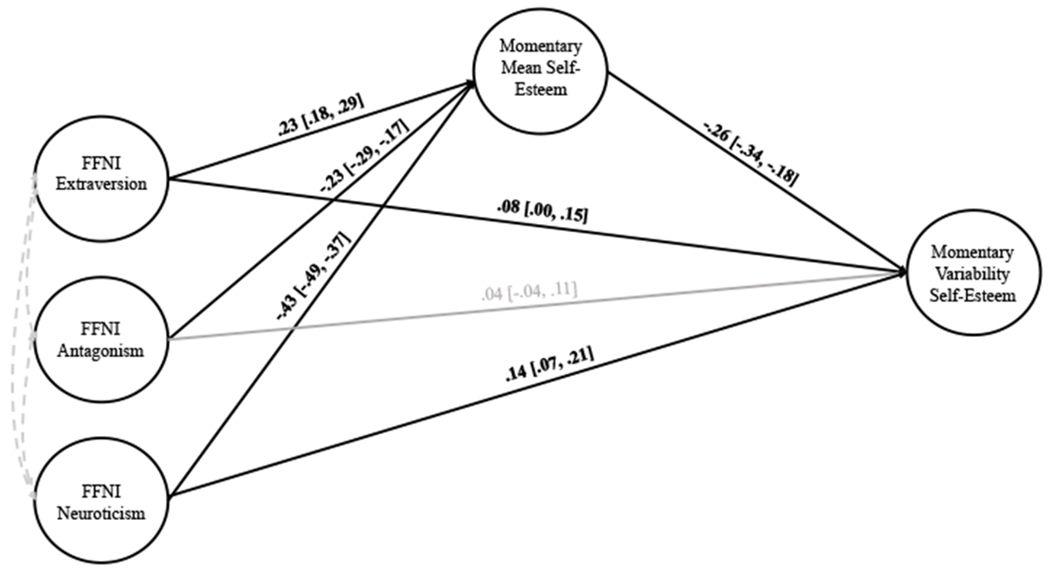

4b). Does a dispositional three-factor structure of narcissism (i.e., exhibitionistic grandiosity, entitlement, and vulnerability) predict state self-esteem level and variability?

Gross Variability associations between dispositional narcissism three-factor structure and momentary self-esteem and self-esteem variability can be found in Table 1 (zero-order associations) and Figure 8 (adjusted path-analytic model). FFNI extraversion was moderately positively associated with the momentary mean of self-esteem. FFNI antagonism and FFNI neuroticism were moderately and strongly negatively associated with the momentary mean of self-esteem, respectively.

Figure 8.

Mega-Analytic Findings for fluctuations between baseline narcissism (three-factor structure) and momentary self-esteem.

Note. N = 862. FFNI extraversion with FFNI antagonism .42 [.36, .47]. FFNI antagonism and FFNI neuroticism were correlated at −.03 [−. 10, .03]. FFNI extraversion and FFNI neuroticism were correlated at −.10 [−. 16, −.03] FFNI = Five Factor Narcissism Inventory.

Moving to associations between fluctuation in self-esteem and dispositional narcissism-three factor structure, both FFNI extraversion and FFNI neuroticism emerged as modest positive predictors of variability in self-esteem.

4c. How do processes observed in question 1a change when controlling for state self-esteem level and variability.

A path-analytic model for a two-factor structure of narcissistic variability, adjusting for self-esteem level and variability, can be found in Figure 9, Panel 1. For a comparison without controlling for self-esteem, please refer to Figure 3. Of note, though values of associations changed slightly, strength and significance of associations remain identical to those in Figure 3.

Figure 9. Mega-Analytic Findings for fluctuations between baseline narcissism (two-factor structure) and momentary variability in narcissism.

Note. N = 862. Panel 1 shows associations between the narcissism variables (solid lines) controlling for self-esteem (dotted lines). Panel 2 shows associations between narcissism and self-esteem variables (solid lines). Both Panel 1 and Panel 2 are from the same model but portions are greyed out for presentation. Variability in grandiosity and variability in vulnerability are correlated at .30 [.22, .36]. Momentary self-esteem and momentary grandiosity are correlated at .30 [.24, .36]. Momentary self-esteem and momentary vulnerability are correlated at −.23 [−.29, −.17]. Momentary grandiosity and momentary vulnerability are correlated at .26 [.19, .32]. FFNI grandiosity and FFNI vulnerability are correlated at .10 [.03, .16]. FFNI = Five Factor Narcissism Inventory.

4d. How do processes observed in question 1b change when controlling for state self-esteem level and variability.

A path-analytic model for a three-factor structure of narcissistic vulnerability, controlling for self-esteem level and variability can be found in Figure 10. For a comparison without controlling for self-esteem, please refer to Figure 4. As with the two-factor structure above, though values of associations changed slightly, strength and significance of associations remain identical to those in Figure 4.

Figure 10. Mega-Analytic Findings for fluctuations between baseline narcissism (three-factor structure) and momentary variability in narcissism.