Abstract

In this study we analyzed the social networks of a systematic sample of married adolescent girls (ages 13–19 years) residing in Dosso, Niger (N=322); data were collected as part of an evaluation of a family planning (FP) intervention. Participants were asked to name individuals important in their lives (alters) using three name generating questions as part of a larger survey including questions about reproductive health, social norms, and FP. Each girl was asked specific questions about their alters. One alter per girl was then recruited to be separately interviewed (N=250), using a subset of questions asked of the primary respondent. This provided us with two separate datasets: one in which we have data from each respondent regarding each person that they nominated, and one in which we have the interviewed alters matched with the respondent who nominated them. We found that married adolescent girls who were nulliparous were more likely to have no alters, and that those with the most alters had participated in the intervention. Alters of treatment participants were more likely to have used FP. Respondents were more likely to have used FP when their sisters or in-laws had, but there was no correlation with use by friends. Our results provide evidence of diffusion of the FP program to those close to intervention participants. Future research should explicitly study these dynamics, as they are crucial to understanding intervention costing, impact, and the possibility of normative change.

Keywords: Niger, family planning, early marriage, social norms, social networks, interventions, contraceptive use, child marriage

Introduction

Though many sub-Saharan African countries have gone through significant demographic changes, Niger remains the country with the world’s highest total fertility rate (7.6 births per woman) and adolescent fertility rate (Institut National de la Statistique, 2018). In Niger, child marriage is highly prevalent with about one-fourth of girls married by the age of 15 and three-fourths by the age of 18 (Institut National de la Statistique, 2018; Institut National de la Statistique & ICF International, 2013). Importantly, work in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) shows that girls who are married early lack decision-making power, particularly with respect to health-related decisions like contraceptive use (Hameed et al., 2014; A. S. Shahabuddin et al., 2016; A.S. Shahabuddin et al., 2017). While this indicates that others are either making or significantly influencing contraceptive use decisions for married female adolescents, little is known about the social networks and norms that influence their attitudes and practices related to family planning (FP).

Because FP interventions frequently work specifically with individual women, evaluation studies often fail to assess the impact of the intervention on the social context, or the impact of social context on the success of the intervention. The social network dynamics of FP interventions amongst adolescent wives can work in multiple directions. On the one hand, because young wives, like those in Niger, may not make the decisions regarding contraceptive use, a social network approach can help identify social barriers to their use. On the other hand, a social network approach can also help intervention programmers understand the possible diffusion of intervention messages promoting FP use from these young adolescents to others that they engage with in the community. Diffusion of intervention messages is a critical but often overlooked aspect of the impact of an intervention in a community (Kohler et al., 2000). In both the case of networks as barriers or networks facilitating diffusion, an understanding of social norms within these populations is a crucial piece of the puzzle.

To improve FP utilization in this population of adolescent wives in rural Niger, it is crucial to make significant and sustainable changes in the norms that shape FP attitudes, norms and behaviors, including those related to women’s reproductive autonomy. This study is one of the first in Francophone West Africa to collect social network data specific to married adolescent girls’ social norms regarding FP. The results we present represent a significant advancement in current understanding of the motivations for use or non-use of contraceptive methods and have the potential to inform innovative approaches to create demand for FP services among highly vulnerable populations. Here, we analyze the characteristics of girls’ reported networks; the associations of girls’ perceptions of their network members (perceived norms) with girls’ FP use; the possible role of the intervention in girls’ reported norms regarding FP use, and alters’ reported FP use; and how the nature of the relationship between the respondent and her network members potentially moderates these associations.

Background

Demographic research suggests that adoption of FP is frequently associated with an ideational shift, or a community shift in normative thinking, including changes in ideas around the benefits of large families, the acceptability of FP within proximal networks, and self-efficacy to successfully acquire and use FP (Babalola et al., 2015; Kincaid, 2000; Montgomery & Casterline, 1996). Ideally, in norms research, normative reference groups would be identified through the use of discrete social network ties (Shakya et al., 2014a, 2015), but in much health and development research such data are lacking. Using network analysis can help identify the specific groups and pathways through which norms change can occur.

Prior research has delineated two fundamental mechanisms by which the diffusion of ideational shifts can occur: social learning and social influence (Kohler et al., 2001; Lowe & Moore, 2014; Montgomery & Casterline, 1996; Shakya et al., 2014b). Social learning occurs when an individual observes others adopt a new behavior, and concluding that the behavior has some utility, decides to adopt it herself (Cislaghi & Shakya, 2018; Maccoby, 2007). This is consistent with what social psychology scholar Cialdini has termed descriptive norms (Cialdini, 2007). Descriptive norms are behaviors people engage in that can be observed in the environment. Seeing others engage in those behaviors, individuals are likely to conclude that the behavior is appropriate and that it may have some utility. Social influence occurs when others actively strive to influence the behavior of another. This is a case of injunctive norms—behaviors around which others in one’s proximal network have some perceived stake (Cialdini et al., 2006; Cislaghi & Heise, 2018). In the case of injunctive norms, violating the norm may mean a social sanction such as disapproval or ostracization (Mackie et al., 2015). Norms against FP held by proximal people in a girl’s network may impede her ability to adopt FP even if she herself would like to. Similarly, such norms would work against a possible diffusion effect. However, if FP diffuses by social learning, then injunctive norms are not at play and simply exposing people to the new information may be sufficient to instigate change.

There is evidence that in some contexts, FP adoption messages may spread through diffusion (Gayen & Raeside, 2010; Murphy, 2004). A study on an FP media campaign conducted in a community in rural Nepal, found that approximately half of the community was exposed to the program indirectly, meaning that they heard of it through someone else, and that those who had been reached indirectly were likely to adopt FP (Boulay et al., 2002). The authors determined that once this indirect effect was accounted for, the overall reach of the program was 50–75% greater than initially reported. In Malawi, researchers conducted qualitative interviews with community members about FP communication, and found that people in the community heard about FP primarily through discussion (Paz Soldan, 2004). Women spoke to each other in depth about the intricacies of FP, such as methods used, side effects experienced, and covert use, while men discussed the issue of limiting family size in general.

In rural Kenya, research showed that social learning dynamics are primarily at play, and that network impacts are stronger for men than for women (Behrman et al., 2002). However complex dynamics around FP uptake were also identified. In areas where there were active markets, and people were frequently exposed to individuals outside of their proximal networks, social learning was the dominate means by which FP ideas spread. In contrast, in areas with less outside interaction, FP decisions were mainly determined by social influence (Kohler et al., 2001). Research in rural Honduras found that while social influence at the community level may play a role (Shakya et al., 2019), the factor most strongly associated with adolescent birth is the adolescent birth experiences of proximal network members (Shakya et al., 2020).

Social influence is a trickier dynamic than social learning, partially because social influence works within the context of injunctive norms. The maintenance and enforcement of injunctive norms involves more complex levels of social reinforcement. The reference groups, or the people to whom an individual turns for expectations regarding appropriate behavior tend to be more proximal (Mackie et al., 2015), and the level of influence tends to be stronger the more densely connected the individuals are within their networks (Kohler et al., 2001; Madhavan et al., 2003). Injunctive norms can be difficult to change, but once changed may be more sustainable. Injunctive norms around FP are often strongly tied to fertility norms (Madhavan et al., 2003), and programs that do not successfully address fertility norms may increase the use of FP, while making no impact on overall fertility (Murphy, 2004).

Injunctive norms against FP use may also be in the domain of the husband rather than the wife. In Mali women reported that their husbands were unwilling to allow them to use contraception because its use was associated with a reputation for marital infidelity and violated local fertility norms (Bove et al., 2012). In Uganda, community level aggregate gender role norms attenuated the effect of perceived benefit on FP use (Paek et al., 2008). While the woman’s report of the perceived benefit of FP use was predictive, that association was weaker in communities in which people reported support for inequitable gender roles.

The vast majority of FP programs target married women and girls, and while some interventions also engage male partners, they may be less likely to succeed in the long-term because they do not engage the girl’s social network to transform social norms beyond the inclusion of her partner. A pilot intervention aimed at strengthening the role of the husbands in women’s reproductive life in Niger led to an increase in women’s use of health facilities and better use of contraception (Badjeck et al., 2012). In the same context, Nouhou showed that the social influence regarding women’s acceptance of birth control varies according to their religiosity (2016). More religious women make their reproductive choices by referring to their husbands and religious leaders, while the less religious ones refer to other women in their community.

Methods

Data Source

We conducted the present social network analysis among married adolescent girls and their husbands in 16 villages in the Dosso district of the Dosso region of Niger. The network analysis was a supplement to the Reaching Married Adolescents (RMA) study (a study to assess the effectiveness of a community-based FP promotion intervention among married adolescent girls and their husbands in the Dosso region). We collected data for the primary study from participants across 48 villages clustered within the Dosso, Doutchi, and Loga districts (16 villages per district). Participants completed surveys at baseline (2016) and Time 2 (2018). Of the 16 villages in each district, we randomly assigned 4 to the control condition. We randomly selected villages which met the following inclusion criteria: 1) having at least 1000 permanent inhabitants; 2) primarily Hausa or Zarma-speaking (the two major languages of Niger); and 3) including no known recent intervention specifically around FP or female empowerment with married adolescent wives or their husbands.

We randomly selected 25 married female adolescents ages 13–19 years and their husbands from each of the 48 villages using a list of all eligible married female adolescents that was provided by each village chief. Eligibility criteria for the married female adolescents included: 1) ages 13–19 years old; 2) married; 3) fluent in Hausa or Zarma; 4) residing in the village where recruitment was taking place with no plans to move away in next 18 months or plan to travel for more than 6 months during that period; 5) not currently sterilized; and 6) provided informed consent to participate. Of those who were randomly selected, 81.6% participated in the baseline survey. The major reason for non-participation was the inability to locate many of the households included on the original list provided by the chief. We found no significant differences in wife’s age, husband’s age, or time spent away from the village across those who did and did not participate.

Gender-matched trained Research Assistants (RAs) from the Dosso region conducted separate surveys with the young women and their husbands. All RAs could fluently read and speak French and fluently speak Hausa and/or Zarma. Research Assistants visited the randomly selected households and conducted a Household Recruitment Screener to confirm eligibility. If the household did not include an eligible wife/husband dyad, the RAs randomly selected a replacement in their place. Research Assistants made up to three visits to each of the selected participants, after which no additional efforts were made.

Research Assistants administered the surveys in a private location in the village indicated by the participant and out of earshot of another person—typically an outdoor area. While the surveys were written in French, the RAs conducted the interviews in either the Hausa or Zarma language, depending on participant’s language preference, as neither Hausa nor Zarma are commonly written languages (Hausa is possible to write, but exceedingly few are able to read this script). The survey took approximately 40–60 minutes to complete and was administered using pre-programmed tablets.

The Social Network Module

We collected data for this analysis via the Social Networks Module of the main RMA study Time 2 survey, plus a separate module we administered to one nominated social contact (referred to here as alters) per RMA participant. We administered the Social Network Module of the main RMA study Time 2 survey to respondents only in the Dosso district, including those enrolled in both the RMA intervention and controls. We asked all participating adolescent wives in the 16 selected villages three questions to identify the names of individuals important in their lives. These questions were chosen after in-depth qualitative network interviews that allowed us to assess how these questions would perform as possible predictors of FP use. Questions included: 1) Who do you trust to talk to about personal and important matters; 2) With whom do you discuss decisions about family, including decisions around fertility and FP; and 3) Any additional people who helps you make decisions about delaying or spacing pregnancy. For each of these three questions, participants could name up to three alters. We asked participants to rank these people on a ladder scale of 1–6 on how influential they are in the participant’s life.

Because husbands were interviewed as part of the main RMA study, we asked participants to name alters besides their husbands. Alters could be anyone within the village over the age of 13, regardless of gender or relationship. For each person nominated, we asked participants a series of follow-up questions about their nominated alters to help understand influential relationships including: name, place of residence, gender, relationship to participant, age, marital status, and number of children. After we had interviewed all RMA respondents, final alter lists were compiled. Trained, gender-matched RAs approached one alter per RMA respondent, requested their participation, and received their consent. The Alter Survey took approximately 45–60 minutes to complete and included a subset of questions from the main RMA survey, including reproductive health history, use of modern contraception, social norms and attitudes around gender roles, and approval of contraceptive use. We also asked alters to nominate their own alters via the Social Network Module questions, although none of the alters’ alters were interviewed. At no point did we disclose to interviewed alters who had nominated them. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of California San Diego (UCSD) as well as the Nigerien Ministry of Health IRB1. Because the Alter Survey comprised a subset of questions from the main Primary Respondent Survey (which included the Social Network Module), when we interviewed alters, we asked them if they were participants in the main RMA study. If the alter was a primary respondent (including the participant’s husband or wife), we noted their nomination but they were not re-interviewed as an alter since their data would have already been captured by the Primary Respondent Survey.

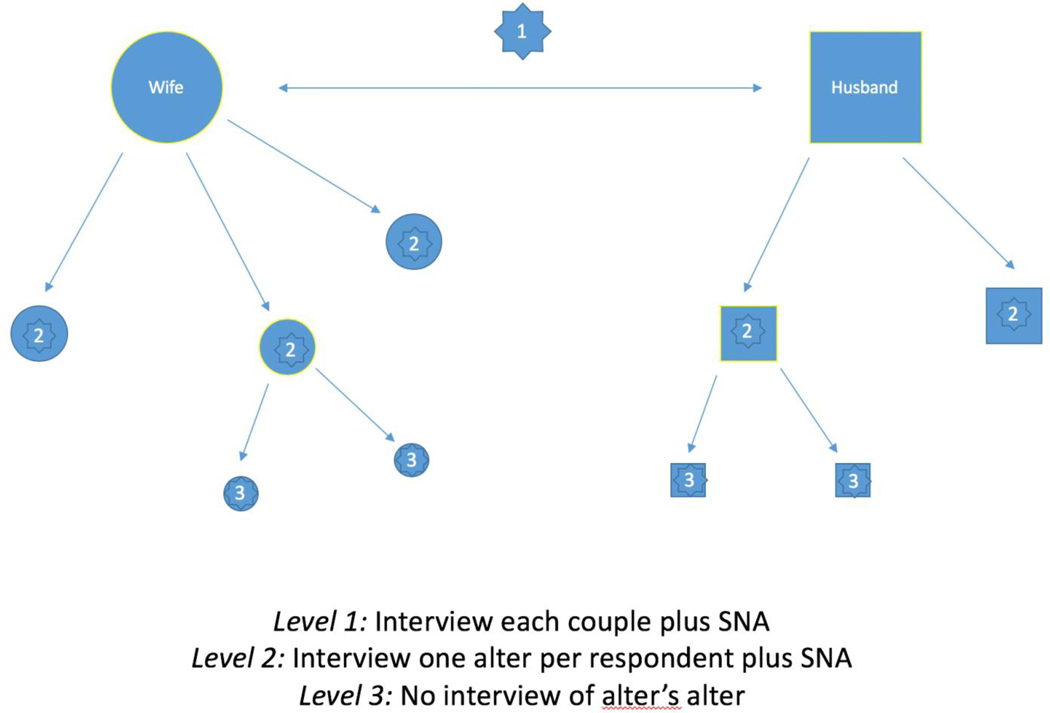

Measures

Data for the current study, therefore, come from two separate sources. First, we have the Primary Respondent Survey, including their own behavioral and demographic measures, as well as their answers to the Social Network Module. Besides the identifying characteristics and demographics provided by the primary respondents about their alters, we asked participants questions to assess their perceptions of their alters’ support for FP, support for men who listen to their wives’ fertility preferences, and belief in timing for a first birth after marriage. Second, we have data from the Alter Survey with measures for one alter per primary respondent. The Alter Survey included a subset of questions asked in the Primary Respondent Survey including: 1) socio-demographics and reproductive history; 2) use of modern contraceptive methods; 3) acceptance of modern contraceptive methods; 4) behavioral intentions regarding contraceptive method use; 5) perceived social norms regarding gender roles, intimate partner violence (IPV), fertility, etc.; 6) women’s autonomy. We also administered a Social Network Module for each alter in which they nominated alters but these second degree alters were not interviewed. See Figure 1 for a visualization of the data collected.

Figure 1:

Primary respondents were couples interviewed individually (Level 1), during which time they were also asked the questions from the Social Network Module. One alter per participant was then interviewed (Level 2), including a social network survey. Alter’s alters (Level 3) were not interviewed, however data was provided regarding them from the alter.

Analysis

Consistent with the two sources of data, our analysis was divided into two primary components. In the first component we analyzed the primary respondents’ answers to questions about their alters and looked at them in conjunction with their answers regarding their own behaviors. A total of 322 female respondents were administered the Social Network Module. Of those, 283 provided information regarding at least one alter. The remaining 39 female respondents (12%) noted no one that they could name in response to the network questions. Matching each respondent with each of their nominated alters resulted in 439 unique dyads, an average of 1.36 alters per respondent, which is what we used for this first analysis. After excluding observations with missing data, our final N was 403. Because participants who named more than one alter would be represented in the data more than once, we used a general estimating equation in our regression analyses to adjust the standard errors for multiple observations of the same participant. Our analyses used adjusted logistic regression models, controlling for girl’s baseline parity, education, age, age at marriage, age difference between herself and her husband, number of alters, and husband’s baseline migration.

The second component of the analysis used data from the Alter Survey (N=251), with alters’ own responses to questions regarding their own attitudes and behaviors. We matched the Alter Surveys with the nominating primary respondent so that we could assess associations between the respondents and their alters. For each respondent we interviewed one alter, ideally the one which they named as being the most influential, but if that person was not available, we attempted to interview the second most influential. Of the 283 respondents who named alters, we were able to interview alters for 250 of them (87%). Of these 4 were men, who we excluded from the present analysis in order to keep the analyses specific to female alters. For analyses that included information from both respondents and their alters, we used dyadic analyses, but because each respondent only had one alter interviewed in the Alter Survey, there were no repeated observations of any of the respondents. Analyses were thus adjusted multi-level logistic regression models, clustering on village and controlling for alter age, alter parity, number of alters named, and alter education.

Results

Descriptive

Participants were on average 17.4 years of age (SD 1.5) (Table 1). Approximately half reported ever having used modern FP, and 76% were in the treatment condition versus being in the control condition. Participants nominated a mean number of 1.36 (SD 0.81) people. The majority named 1, but 40% of participants nominated more than one person. The alter relationships identified by participants included friends (37%), family (29%, excluding mother or sister), mothers (5%), sisters (11%), and in-laws (10%). A large portion of respondents were unable to provide any answer regarding the alters age. All alters with the exception of 4 were female, and almost all alters were married (95%). Despite the fact that many respondents were unable to provide the age of the alter (egos replied don’t know for 216 alters), all of them could provide the alters number of children (mean 2.6, SD 2.0).

Table 1:

Respondent and alter attributes, as reported by the respondent

| Respondent attributes N=322 | |||

|

| |||

| Mean | SD | % | |

|

| |||

| Respondent age | 17.4 | 1.5 | |

| Respondent number of children | 1.6 | 1.1 | |

| Respondent percent nulliparous | 13% | ||

| Respondent attended modern school | 38% | ||

| Respondent only attended Quranic | 14% | ||

| Respondent ever use of FP | 49% | ||

| Respondent in the intervention group | 75% | ||

| Respondent average number of alters | 1.4 | 0.8 | |

| Respondent percent with no alters | 12% | ||

|

| |||

| Alters nominated (respondent report) N=403 | |||

|

| |||

| Alter age (216 missing) | 24.5 | 8.44 | |

| Alter number of children | 2.61 | 1.98 | |

| Alter was surveyed | 57% | ||

| Alter relationship to respondent | |||

| Sister | 11% | ||

| Mother | 5% | ||

| In-law | 10% | ||

| Friend | 37% | ||

| Natal family | 29% | ||

| Other | 6% | ||

| Believes alter supports longer first birth timing | 31% | ||

| Believes alter would support respondent FP use | 85% | ||

| Believes alter approves of men listening to wives fertility wishes | 82% | ||

| Alter was part of the study | 15% | ||

Network composition

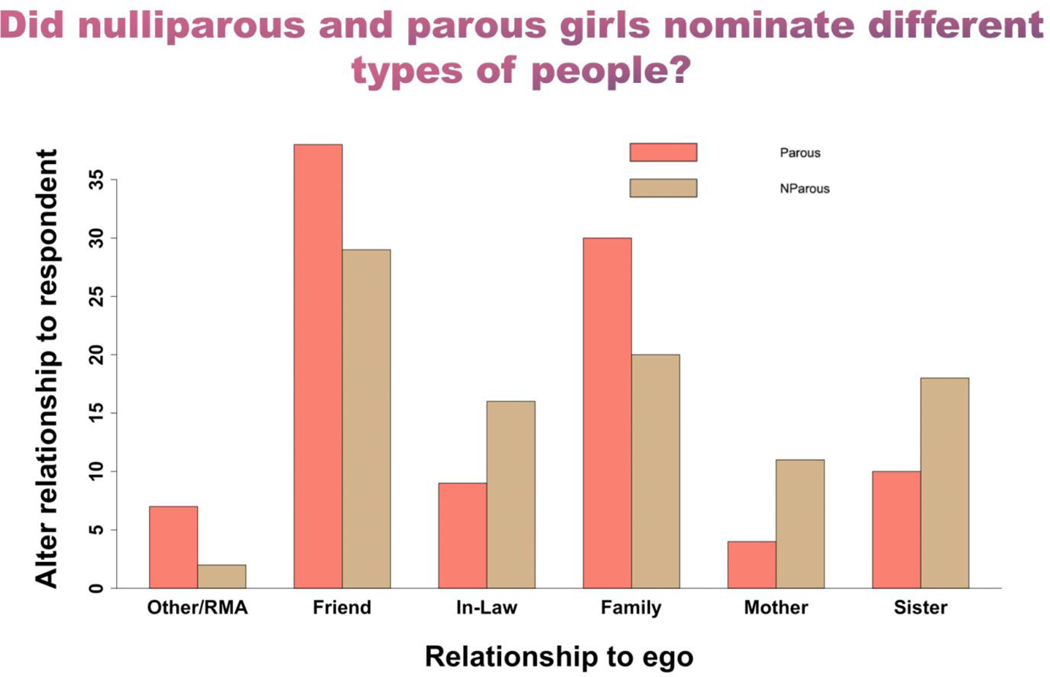

The purpose of our first analysis was to understand the 12% of respondents who did not nominate anyone as an alters. We found that girls with no alters (SA Table 1) were more likely to be nulliparous [AOR 2.75 (95% CI 1.09–6.9)], and to be more than 5 years younger than their husbands [AOR 2.46 (95%CI 1.06–5.71)]. We then looked to see if the type of alter differed for nulliparous compared to parous girls (Figure 2, SA Table 2). We found that girls who nominated mothers [AOR 0.36 (95% CI 0.11–1.13)], sisters [AOR 0.42 (95% CI 0.16–1.11)] and in-laws [AOR 0.32 (95% CI 0.10–1.02)] were less likely to be parous than those who nominated friends. Because of small cell sizes however, estimates for mothers and sisters are not statistically significant at p<0.05. We also found that while participants in the RMA intervention were no more likely than controls to have nominated any alters, they were 1.99 times more likely (95% CI 1.04–3.80) to have nominated more than one alter (SA Table 3).

Figure 2:

Difference between the types of relationships identified by parous versus nulliparous girls.

Respondents reports on alters

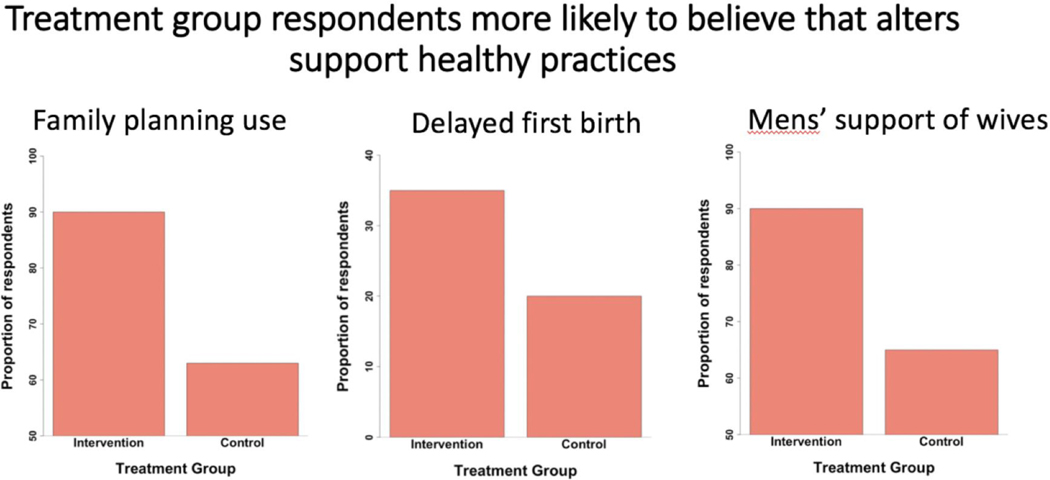

We next looked at the respondents’ reports of whether they think their alters would support their use of FP, support men who listen to their wives’ fertility preferences, and how soon alters thinks a new wife should have her first baby. Overall respondents were likely to believe that alters support a first birth within one year of marriage, with a significant proportion (24%) saying that they don’t know. Categorizing a longer first birth timing for adolescent girls vs a shorter timing (less than two years or don’t know), we found that RMA intervention participants were 2.16 more likely than controls (95% CI 1.08–4.29) to think that their alters support a longer time for first birth, as were respondents with a greater number of alters [AOR 1.73 (95% CI 1.17–2.57) for each additional alter] (Table SA 4). Treatment respondents were also more likely to think that their alters would support their use of FP (Table 3) [AOR 3.82 (95% CI 2.00–7.23)], and to think that alters would support a man who listens to his wife’s fertility preferences (SA Table 5) [AOR 3.16 (95% CI 1.72–5.3)], as were respondents with more alters [AOR 1.63 (95% CI 1.06–2.51) for each additional alter]. See Figure 3 for a representation of treatment versus control respondents on all three measures. When we broke down the respondents’ belief in whether their alters would support the respondents’ use of FP, there was evidence that respondents who believed that alters who were extended family members and mothers were less likely to support respondents’ FP use, though due to small cell sizes this did not reach significance (not shown).

Table 3:

Association between being in treatment group and reporting a belief that alter supports her potential use of modern family planning, dyadic analysis N=402

| Beta | SE | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention group vs control | 1.34 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| Respondent age | −0.11 | 0.12 | 0.34 |

| Education: Quranic only: ref modern | −0.84 | 0.48 | 0.08 |

| Education: none: ref modern | −0.05 | 0.34 | 0.87 |

| Age difference husband-wife | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.95 |

| parity | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.09 |

| Assets: median vs low | −0.52 | 0.42 | 0.21 |

| Assets: high vs low | −0.36 | 0.44 | 0.42 |

| Husband migrates | −0.15 | 0.37 | 0.69 |

| Number of alters | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.15 |

Figure 3:

Compared to the control group, respondents in the RMA treatment group are more likely to report that their alters would be supportive of their family planning use, agree with a later amount of time between marriage and first birth, and would be supportive of men who listen to their wives fertility preferences.

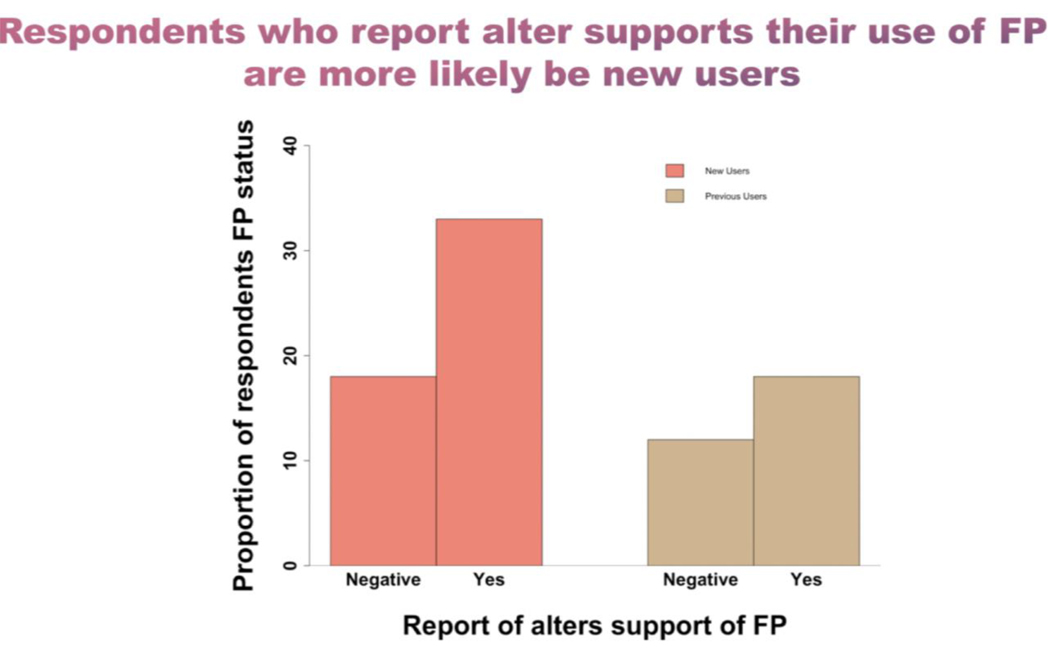

For our last analysis using the Primary Respondent Survey, we consider respondents’ use of FP. We find that the respondents who have ever used FP (Table 4) [AOR 2.69 (95% CI 1.36–5.34)], or are currently using modern FP (SA Table 6) [AOR 2.08 (95% CI 1.02–4.2)] are more likely to believe that an alter supports their use of FP. Looking a little further, we find that the association between respondents’ use of FP and their perception of alters’ support of FP is significant for new users (those who had not reported ever using at baseline), but not for previous users (Figure 4). Respondents with no alters are less likely to have used FP (SA Table 7), although this is partially attenuated by parity. Including parity in the model dampens the association of having no alters but does not eliminate it. The chance that a respondent reports ever having used FP also differs by who that respondent has named as an alter. Respondents who name mothers as alters are significantly less likely to have used FP than those who named friends [AOR 0.26 (95% CI 0.07–0.89)].

Table 4:

Association between the respondents belief that alter supports her FP and respondents reported ever use of FP N=250

| Beta | SE | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reports belief that alter supports her use of FP | 0.99 | 0.35 | 0.00 |

| Intervention group vs control | 0.88 | 0.41 | 0.03 |

| Respondent age | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.37 |

| Education: Quranic only: ref modern | −0.49 | 0.43 | 0.25 |

| Education: none: ref modern | −0.40 | 0.33 | 0.23 |

| Age difference husband-wife | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.43 |

| parity | 0.49 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

| Assets: median vs low | −0.38 | 0.37 | 0.29 |

| Assets: high vs low | −0.48 | 0.38 | 0.20 |

| Husband migrates | −0.32 | 0.32 | 0.31 |

| Number of alters | −0.17 | 0.22 | 0.43 |

Figure 4:

The association between the likelihood that a respondent believes that their alter supports FP and the respondents report of ever having used FP is significant for new users (those who did not report use at baseline), but not for previous users.

Alter demographics

In the second component of our analysis, we looked at the Alter Survey (Table 2). The proportion of alters in each relationship category was very close to what we observed in the Primary Respondent Survey, however in this case, because we were interviewing alters directly, we had accurate measures of alters’ ages. Alters on average were 7 years (SD 8.5) older than respondents, but this varied by type of relationship. Mean ages for alters were: 38.7 years for mothers (SD 10.6), 23.1 for sisters (SD 5.7), 28.5 for extended family (SD 11.7), 24.6 for in-laws (SD 8.5), and 21.5 for friends (SD 5.4). It is interesting to note that the in-law category was relatively young and did not fit the age profile of an elder in-law, but was more consistent with women closer to the respondents’ own ages (e.g., a sister-in-law or co-wife). Of the 251 alters interviewed, 36 of them (14%) were also participants in the RMA program.

Table 2:

Alter attributes from Alter Survey, alters self-report

| Alters interviewed (N=251) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Mean | SD | % | |

| Alter age | 26.0 | 10.04 | |

| Alter relationship to respondent | |||

| Sister | 8% | ||

| Mother | 6% | ||

| In-law | 10% | ||

| Friend | 39% | ||

| Natal family | 30% | ||

| Other | 6% | ||

| Ever used family planning | 50% | ||

| Modern Schooling | 25% | ||

| Quranic schooling | 22% | ||

| Parity | 3.8 | 2.5 | |

| Heard of RMA (treatment village) | 75% | ||

| Have talked to others about RMA (those who report knowing about it) | 50% | ||

| Believes community supports FP use | 84% | ||

| Participated in the RMA program | 14% | ||

Alter RMA awareness and FP use

One of the research questions that inspired the Social Network Module, was whether there was evidence for diffusion of the RMA intervention. Our first question then was whether or not alters that were nominated by RMA intervention respondents were familiar with the RMA program (excluding those who were themselves RMA respondents). We found that 60% of treatment alters reported familiarity with the RMA program, and of those, approximately half had discussed it with other people, primarily with friends. We then found that alters who were nominated by RMA intervention respondents were more likely to have reported ever use of FP as compared to alters of control respondents (Table 5), [AOR 2.29 (95% CI 1.07–4.93)], but that this association was lost when knowledge of the RMA program was included in the model. A cross-sectional mediation analysis was significant (p=0.03 with 40% of the direct effect explained by the mediation, not shown), suggesting that being nominated by an intervention respondent led to knowledge of RMA, which potentially increased the likelihood that the alter used FP (see Figure 5). We would like to emphasize, however that these results are cross-sectional, and using a relatively small sample size, so we would be remiss to make any claims regarding causality. However, the results are compelling evidence towards diffusion of the intervention effect and warrant further investigation. Finally, we looked descriptively at the alters’ reported ever use of modern FP by relationship to the respondents. We found that mothers were significantly less likely to have used FP compared to most other groups [for example age-adjusted odds of mothers using FP are 0.26 compared to friends, and for family 0.42 compared to friends].

Table 5:

Association between respondent being in the treatment condition and alter reporting ever use of FP N=250

| Beta | SE | P | Beta | SE | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent treatment vs control | 0.93 | 0.47 | 0.05 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.33 |

| Alter knows RMA | 0.88 | 0.38 | 0.02 | |||

| Alter is other vs friend | −1.35 | 0.72 | 0.06 | −1.56 | 0.74 | 0.04 |

| Alter is in-law vs friend | 0.20 | 0.52 | 0.70 | 0.08 | 0.53 | 0.87 |

| Alter is family vs friend | −0.57 | 0.38 | 0.13 | −0.71 | 0.39 | 0.07 |

| Alter is mother vs friend | −0.93 | 0.84 | 0.27 | −1.03 | 0.85 | 0.23 |

| Alter is sister vs friend | 0.07 | 0.63 | 0.91 | 0.21 | 0.65 | 0.73 |

| Alter age | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.25 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.26 |

| Alter modern education vs Quranic | −0.29 | 0.45 | 0.52 | −0.28 | 0.46 | 0.55 |

| Alter no education vs Quranic | −0.74 | 0.39 | 0.06 | −0.63 | 0.40 | 0.12 |

| Alter parity | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.15 |

Figure 5:

There is evidence of possible mediation between the association of a respondent’s treatment group, and the use of FP by an alter through the pathway of the alter’s knowledge of the RMA program. Longitudinal data will be necessary to understand this dynamic more clearly.

Association between respondent and alter FP use

Our final set of analyses were conducted to investigate 1) whether socially connected people (i.e., respondents and their alters) in this context are similar in their use of modern FP, and 2) whether this differs by relationship type. We conducted analyses of the associations between the respondents’ use of modern FP and that reported by the alter, and added an interaction to see if this differs by relationship type. We found evidence of an association between the respondents’ FP use and that of the alter [OR 1.52 (95% CI 0.85–2.74)], although it was not significant at p<0.05 (SA Table 9). However, when we interact alters’ use of FP with alters’ relationship to the respondents, we find that the association between the respondents’ and the alters’ use of FP varies greatly (not shown). Respondents’ ever use of FP is strongly associated with that of alters’ in the in-law category and the sister category, but not at all related to that of friends or extended family (Figure 6). Respondents’ ever use of FP is however, significantly associated with the perceived approval of alters (SA Table 10), with some evidence that this association is weaker or non-existent with friends (not shown).

Figure 6:

The association between the respondents use of FP (y axis), and the alters use of FP differs by relationship of the alter to the respondent (x axis). Respondents use of FP is strongly correlated with that of Inlaws and sisters, but not at all related to that of friends or extended family.

Discussion

We used rare social network and reproductive health data from rural Niger to look at the social network and social normative factors that are associated with FP use among married adolescent girls. We had several compelling findings that advance our understanding of the social contexts of these married adolescents, as well as of the association of that context with FP use.

We first found that there were several distinct factors related to being socially isolated, measured here by the inability to name any alters in the survey. Girls that were nulliparous and girls that were significantly younger than their husbands were more likely to be socially isolated. These girls were also less likely to nominate friends, more likely to nominate mothers as alters, and less likely to have used FP. It is not surprising that in a high fertility country like Niger, with a cultural emphasis on early childbearing and large families, girls who have not yet given birth will be unlikely to use FP. However, the social isolation points to an interesting dynamic by which access to the larger community is potentially facilitated by motherhood. Nulliparous girls were not only more likely to have nominated no one, but those who did were far less likely to have nominated friends, controlling for age and education, highlighting an interesting limitation on access to peer networks for this group. This dynamic is potentially facilitated by a social norm that limits the autonomy and enforces a veil of modesty around newly married girls, discouraging them from expressing enthusiasm about marriage, and limiting their interaction with others (Nouhou, 2016).

There is also an interesting and somewhat mysterious dynamic around girls’ mothers that can only be answered with longitudinal data. Girls who nominated mothers are more likely to be nulliparous, to not have nominated friends, and to not have used FP. Mothers are less likely than any other alters to have used FP, and girls are less likely to think that mothers will support FP use than other types of alters. Marriages in Niger are patrilocal, meaning that wives move into their husbands’ home compound, usually with his nuclear and extended family. Unlike in India, where mothers-in-law significantly contribute to decision-making around fertility, in this context, mothers-in-law did not appear to play a major role. Many of these girls are still interacting with their mothers, but these mothers may be enforcing social norms of high fertility, low levels of autonomy, and reluctance to use FP. In this context, older women are more likely to be conservative and less receptive to FP then younger women (Nouhou, 2016). It is clearly a complex dynamic that can only be untangled with further study.

As girls that have friends are more likely to use FP, it would seem reasonable to think that there is a peer diffusion effect taking place in this context, as found in some other studies (Valente et al., 1997). However, our analysis showed absolutely no correlation between the respondents’ use of FP and that of their friends, and no correlation between the respondents’ perception of their friends approval of FP, and their own use. The benefit of friendship, therefore, seems to be a result of increased autonomy and social access after childbirth, and unrelated to any shared interest or shared beliefs around controlling family size. Instead the strongest correlation between respondents and their alters on FP use seems to be with in-laws, and with sisters. This is consistent with some prior research that has identified kin networks as important influences on FP use, as kin are the ones with the highest stake in fertility outcomes (Musalia, 2005).

While low fertility can reflect poorly on a girl and her family (Madhavan et al., 2003), high fertility puts an added economic and resource provision strain on family members who are tasked with childcare assistance. In our own unpublished formative research in these communities, we found that many mothers-in-law were keen to limit fertility amongst daughters-in-law as large numbers of children are difficult to care for, and often suffer from illnesses that add to the childcare burden. It is important to realize, however, that both in-laws and sisters in this sample are relatively young. These are not elders, but in an age range more consistent with slightly older peers. While girls may be observing in-laws’ use of FP and potentially copying it (a descriptive norm facilitated by social learning), girls’ FP use is not correlated with whether these younger women approve of their use. The norm would therefore seem to be descriptive, or based on observation, rather than injunctive or based on overt social approval. The reference group for approval in this context may be the extended family. Again, the average age of this extended family, while older than the girls, is much younger than that of the mothers.

Finally, we observed differences between girls that were part of the RMA intervention and those that were not. Girls who were part of the RMA intervention were more likely to perceive that their alters supported FP and longer first birth timing, had larger networks, and named alters who were more likely to have reported ever using FP, potentially as a result of those alters also being more likely to know about the RMA program. While we cannot claim causality, there is evidence that the RMA program increased girls’ social networks, increased their likelihood of believing that their alters are supportive of healthy reproductive choices, and increased the probability that the program messages diffused to girls’ alters through knowledge of the program. There is a potential response bias, of course, among girls that participated in the RMA program. These girls would be likely aware of the desired outcomes to report in terms of norms, attitudes and use of FP. However, our Alter Survey was completed by one social contact per girl—individuals who mostly did not participate in the RMA program themselves. The chance of treatment induced response bias amongst these alters was therefore low, and yet we still saw that these alters were more likely to know about the RMA program and were more likely to have ever used FP (alters who were RMA participants were excluded from these analyses). The fact that alters of RMA participants were more likely to know about the RMA program and to have reported use of FP is compelling evidence that the RMA program messages did, in fact, diffuse to the social connections of girls enrolled in the program. Potential network diffusion of the messages in reproductive health programs in low resource countries is a tremendously important question in terms of program affordability and sustainability. Untangling the associations between increased social access, FP use, and RMA intervention participation will be crucial for intervention planning, including efforts to increase girls’ reproductive agency.

Our study has limitations. First, the data is cross-sectional, and therefore we cannot track time dependent changes. Second, the sample size is relatively small, and so while we were able to successfully capture many interesting dynamics, for some questions small cell sizes prevented us from being able to conclusively rule out certain possibilities. Third, the data was collected in one district in Niger, and therefore regional cultural tendencies could impact how these results extrapolate to other locations. Finally, while we asked participants 3 separate questions to elicit the names of network members, most of our respondents only provided answers to the first question, perhaps to due fatigue or lack of enumerator motivation to collect more data. In our subsequent studies, we will attempt to ensure that respondents are nominating alters for all name-generation questions.

Despite these shortcomings, our results provide very compelling evidence for strong social dynamics around the use of FP in these communities. Some of these findings were surprising, such as the non-correlation between girls and their friends in FP use. There was also a complex dynamic involving the mothers, parity, FP use and social networks of adolescents that will be interesting to address in further research. While we cannot make any definitive conclusions based on these findings, the relationships are statistically strong, and certainly warrant further research to investigate these dynamics more carefully.

Access to and support for FP for married adolescents in Niger, who have the highest fertility rates of almost any demographic in the world, is a crucial resource for promoting girls’ reproductive autonomy, their health, and the health of their children. An understanding of how social dynamics impact the acceptability and uptake of FP should be a key component of these efforts. Programmers and policy makers promoting FP use in high fertility settings need evidence-based approaches which take into consideration the complex social factors that impact FP acceptance and utilization. Our work suggests that programmatic efforts can be facilitated through strategies that engage girls with proximal members of their social networks, and that assessment of possible diffusion may provide a much more robust understanding of programmatic impacts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding provided by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and NICHD. Funders had no role in in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the articles; or in the decision to submit it for publication.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

All authors report no financial conflicts, or conflicts of interest.

Comité national d'éthique pour la recherche en santé - CNERS

Contributor Information

Holly B. Shakya, Center on Gender Equity and Health, University of California San Diego

Sneha Challa, Center on Gender Equity and Health, University of California San Diego.

Abdoul Moumouni Nouhou, Oasis Initiative Niger.

Ricardo Vera-Monroy, Center on Gender Equity and Health, University of California San Diego.

Nicole Carter, University of California San Diego.

Jay Silverman, Center on Gender Equity and Health, University of California San Diego.

References

- Babalola S, John N, Ajao B, & Speizer I (2015). Ideation and intention to use contraceptives in Kenya and Nigeria. Demographic Research, 33, 211–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badjeck A, Diarra M, & Souley A (2012). Evaluation Finale du 7ème programme de cooperation Niger-UNFPA 2009–2013. Retrieved from https://web2.unfpa.org/public/about/oversight/evaluations/docDownload.unfpa?docId=120

- Behrman JR, Kohler HP, & Watkins SC (2002). Social networks and changes in contraceptive use over time: Evidence from a longitudinal study in rural Kenya. Demography, 39(4), 713–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulay M, Storey JD, & Sood S (2002). Indirect exposure to a family planning mass media campaign in Nepal. Journal of Health Communication, 7(5), 379–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bove RM, Vala-Haynes E, & Valeggia CR (2012). Women’s health in urban Mali: Social predictors and health itineraries. Social Science & Medicine, 75(8), 1392–1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB (2007). Descriptive social norms as underappreciated sources of social control. Psychometrika, 72(2), 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB, Demaine LJ, Sagarin BJ, Barrett DW, Rhoads K, & Winter PL (2006). Managing social norms for persuasive impact. Social Influence, 1(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cislaghi B, & Heise L (2018). Using social norms theory for health promotion in low-income countries. Health Promotion International. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cislaghi B, & Shakya HB (2018). Social norms and adolescents’ sexual health: an introduction for practitioners working in low and mid-income African countries. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 22(1), 38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayen K, & Raeside R (2010). Social networks and contraception practice of women in rural Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine, 71(9), 1584–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hameed W, Azmat SK, Ali M, Sheikh MI, Abbas G, Temmerman M, & Avan BI (2014). Women’s empowerment and contraceptive use: the role of independent versus couples’ decision-making, from a lower middle income country perspective. PLoS One, 9(8), e104633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institut National de la Statistique. (2018). Annuaire Statistique 2013–2017. Retrieved from Niamey, Niger: http://www.stat-niger.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Annuaire_Statistique_2013-2017.pdf

- Institut National de la Statistique, & ICF International. (2013). Enquête Démographique et de Santé et à Indicateurs Multiples du Niger 2012. Retrieved from Calverton, MD: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR277/FR277.pdf

- Kincaid DL (2000). Social networks, ideation, and contraceptive behavior in Bangladesh: a longitudinal analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 50(2), 215–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler HP, Behrman JR, & Watkins SC (2000). Empirical assessments of social networks, fertility and family planning programs: Nonlinearities and their implications. Demographic Research, 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler HP, Berman JR, & Watkins SC (2001). The density of social networks and fertility decisions: Evidence from South Nyanza District, Kenya. Demography, 38(1), 43–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe SMP, & Moore S (2014). Social networks and female reproductive choices in the developing world: a systematized review. Reproductive Health, 11(1), 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE (2007). Historical overview of socialization research and theory. Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research, 13–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mackie G, Moneti F, Shakya HB, & Denny E (2015). What are Social Norms? How are they measured? Retrieved from New York: http://globalresearchandadvocacygroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/What-are-Social-Norms.pdf

- Madhavan S, Adams A, & Simon D (2003). Women’s networks and the social world of fertility behavior. International family planning perspectives, 58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MR, & Casterline JB (1996). Social learning, social influence, and new models of fertility. Population and Development Review, 22, 151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E (2004). Diffusion of innovations: Family planning in developing countries. Journal of health communication, 9(S1), 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musalia JM (2005). Gender, social networks, and contraceptive use in Kenya. Sex Roles, 53(11–12), 835–846. [Google Scholar]

- Nouhou AM (2016). Liberté reproductive et recours à la contraception: Les influences religieuse et sociale au Niger. African Population Studies, 30(2). [Google Scholar]

- Paek HJ, Lee B, Salmon CT, & Witte K (2008). The contextual effects of gender norms, communication, and social capital on family planning behaviors in Uganda: a multilevel approach. Health Education & Behavior, 35(4), 461–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paz Soldan VA (2004). How family planning ideas are spread within social groups in rural Malawi. Studies in Family Planning, 35(4), 275–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahabuddin AS, Nostlinger C, Delvaux T, Sarker M, Bardaji A, Brouwere VD, & Broerse JE (2016). What Influences Adolescent Girls’ Decision-Making Regarding Contraceptive Methods Use and Childbearing? A Qualitative Exploratory Study in Rangpur District, Bangladesh. PLoS One, 11(6), e0157664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahabuddin AS, Nostlinger C, Delvaux T, Sarker M, Delamou A, Bardaji A, . . . De Brouwere V (2017). Exploring Maternal Health Care-Seeking Behavior of Married Adolescent Girls in Bangladesh: A Social-Ecological Approach. PLoS One, 12(1), e0169109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya HB, Barker K, Darmsadt GL, Weeks J, & Christakis NA (2020). Social normative and social network factors associated with adolescent pregnancy: a cross-sectional study of 176 villages in rural Honduras. Journal of Global Health in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya HB, Christakis NA, & Fowler JH (2014a). Association Between Social Network Communities and Health Behavior: An Observational Sociocentric Network Study of Latrine Ownership in Rural India. American Journal of Public Health, 104(5), 930–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya HB, Christakis NA, & Fowler JH (2014b). Social network predictors of latrine ownership. Social Science & Medicine, 125, 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya HB, Christakis NA, & Fowler JH (2015). An exploratory comparison of name generator content: data from rural India. Working Paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya HB, Weeks JR, & Christakis NA (2019). Do village-level normative and network factors help explain spatial variability in adolescent childbearing in rural Honduras? SSM-Population Health, 100371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Watkins SC, Jato MN, Van Der Straten A, & Tsitsol LPM (1997). Social network associations with contraceptive use among Cameroonian women in voluntary associations. Social Science & Medicine, 45(5), 677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.