Scabies is a common ectoparasitic infection that presents with pruritus, widely distributed eczematous papules, and visible burrows (Raffi et al., 2019). Scabies can present differently in elderly patients, notably with burrows absent in the interdigital spaces and present on the face. Delayed diagnosis due to atypical presentation may lead to an increased mite load and severe disease requiring a different treatment approach tailored to older populations (Cassell et al., 2018, Raffi et al., 2019).

A 69-year-old woman who presented with a 10-year history of recalcitrant pruritus illustrates this diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. With diffuse eczematous papules coalescing into plaques and a lack of traditional burrowing in the finger webs, the patient went years without a definitive diagnosis. At one point, a presumptive diagnosis of scabies was made and she underwent traditional permethrin therapy (topical application on days 0 and 14) with only minimal improvement.

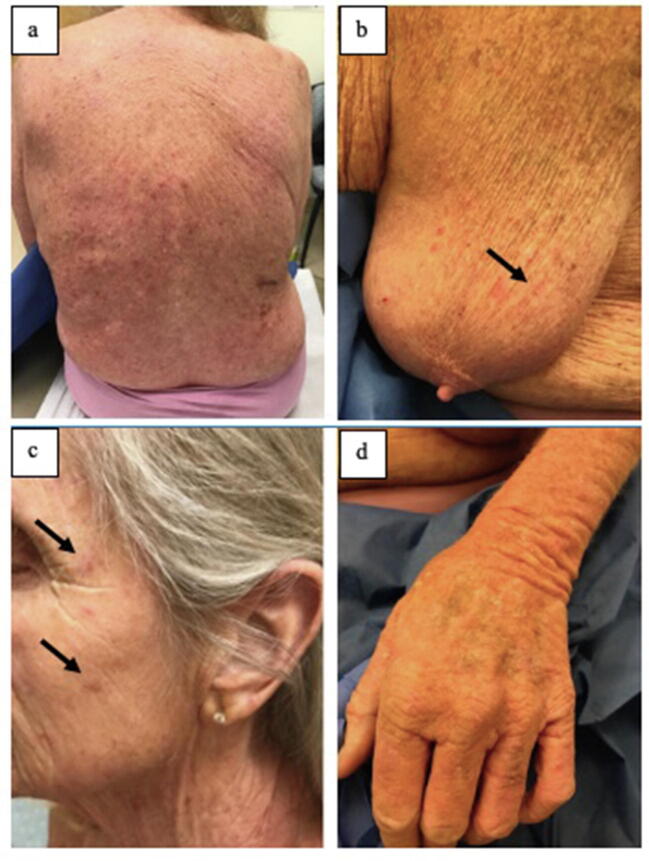

Upon examination, diffuse eczematous papules coalescing into plaques (Fig. 1A) with linear burrows on the feet, wrists, periareolar area (Fig. 1B), buttocks, scalp, and face (Fig. 1C) were observed. There was a distinct lack of burrowing in the finger webs (Fig. 1D). Skin scraping was positive for scabies mites.

Fig. 1.

(A) Diffuse eczematous papules and plaques on patient’s back. (B) and (C) Linear burrowing was visible in many areas, including the periareolar area and cheeks. (D) There was a distinct lack of burrowing in the finger webs.

Continued pruritis after treatment may be attributed to postscabietic itch, a phenomenon related to continued host immune response after the clearance of scabies mites. Unlike in our patient, this pruritis should decrease over subsequent weeks and no additional mites should be found on skin scrapings. Anchoring on this diagnosis may delay additional therapy. Our case and others in the literature indicate that traditional treatment with twice topical permethrin in elderly patients with widespread disease may not be sufficient (Morris Hicks and Lewis, 1995, Wilson et al., 2001). Ultimately, there is little research on the treatment of severe disease in older adults.

Solution

Given the extent of disease and prior failure of twice topical permethrin treatment, our patient was instructed to take 12 mg of oral ivermectin (200 µg/kg) on days 0 and 14 and to apply topical permethrin 5% to her entire body, including her face, scalp, hairline, genitals, and between the fingers and toes once a week for 3 weeks (days 0, 7, and 14) (Table 1). The eczematous papules and itch resolved within 1 month, and the patient did not report any adverse effects from the therapy. It is important to also consider treating a patient’s close contacts, who may have been exposed to scabies mites.

Table 1.

Treatment regimen recommended for widespread eczematous dermatitis in the elderly when scabies is on the differential diagnosis.

| Week 1 | Ivermectin 200 µg/kg + permethrin 5% (full body)a |

| Week 2 | Permethrin 5% (full body) |

| Week 3 | Ivermectin 200 µg/kg + permethrin 5% (full body) |

Permethrin applied to full body, including the scalp, hairline, genitals, and between the fingers and toes.

The combination of oral ivermectin and topical permethrin is often used for crusted scabies (Raffi et al., 2019). However, this approach may be suitable to address extensive disease and barriers that may exist in applying creams in older populations (Raffi et al., 2019). Oral ivermectin was considered controversial in the past after a 1997 study suggested an increased risk of death (Raffi et al., 2019). However, other researchers have reaffirmed ivermectin’s safety, including a study of 220 nursing home residents treated with ivermectin that did not show any difference in mortality (Reintjes and Hoek, 1997). According to the package insert, clinical trials determining the safety of ivermectin indicated that tachycardia (a generally harmless condition) was the most common side effect, found in 3.5% of participants. Our case speaks to the efficacy and safety of this approach.

Scabietic infection in aging adult represents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Scabies must be differentiated for diffuse pruritus or nonspecific eczematous eruptions in aging patients, even after partial treatment. Severe disease, delayed diagnosis, and comorbidities in older populations may require a more comprehensive therapeutic regimen that addresses the extent of infection and atypicality of presentation in the geriatric population.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Study Approval

The author(s) confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies.

References

- Cassell J.A., Middleton J., Nalabanda A., Lanza S., Head M.G., Bostock J. Scabies outbreaks in ten care homes for elderly people: a prospective study of clinical features, epidemiology, and treatment outcomes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(8):894–902. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30347-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris Hicks L.E., Lewis D.J. Management of chronic, resistive scabies: a case study. Geriatr Nurs. 1995;16(5):230–236. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4572(05)80171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffi J., Suresh R., Butler D.C. Review of scabies in the elderly. Dermatol Ther. 2019;9(4):623–630. doi: 10.1007/s13555-019-00325-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reintjes R., Hoek C. Deaths associated with ivermectin for scabies. Lancet. 1997;350(9072):215. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62377-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M.M., Philpott C.D., Breer W.A. Atypical presentation of scabies among nursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(7):M424–M427. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.7.m424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]