Key Points

Question

What are the rates of axillary pathologic complete response (pCR) for different breast cancer subtypes in patients with initially clinically node-positive breast cancer?

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis, including 33 unique studies with 57 531 unique patients, showed that the hormone receptor (HR)–negative/ERBB2-positive subtype was associated with the highest axillary pCR rate (60%). The remaining subtypes were associated with the following axillary pCR rates in decreasing order: 59% for ERBB2-positive, 48% for triple-negative, 45% for HR-positive/ERBB2-positive, 35% for luminal B, 18% for HR-positive/ERBB2-negative, and 13% for luminal A breast cancer.

Meaning

These data can help estimate axillary treatment response in the neoadjuvant setting and thus select patients for more or less invasive axillary procedures.

This systematic review and meta-analysis pools data from studies in the neoadjuvant setting on axillary pathologic complete response rates for different breast cancer subtypes in patients with initial clinically node-positive disease.

Abstract

Importance

An overview of rates of axillary pathologic complete response (pCR) for all breast cancer subtypes, both for patients with and without pathologically proven clinically node-positive disease, is lacking.

Objective

To provide pooled data of all studies in the neoadjuvant setting on axillary pCR rates for different breast cancer subtypes in patients with initially clinically node-positive disease.

Data Sources

The electronic databases Embase and PubMed were used to conduct a systematic literature search on July 16, 2020. The references of the included studies were manually checked to identify other eligible studies.

Study Selection

Studies in the neoadjuvant therapy setting were identified regarding axillary pCR for different breast cancer subtypes in patients with initially clinically node-positive disease (ie, defined as node-positive before the initiation of neoadjuvant systemic therapy).

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers independently selected eligible studies according to the inclusion criteria and extracted all data. All discrepant results were resolved during a consensus meeting. To identify the different subtypes, the subtype definitions as reported by the included articles were used. The random-effects model was used to calculate the overall pooled estimate of axillary pCR for each breast cancer subtype.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcome of this study was the rate of axillary pCR and residual axillary lymph node disease after neoadjuvant systemic therapy for different breast cancer subtypes, differentiating studies with and without patients with pathologically proven clinically node-positive disease.

Results

This pooled analysis included 33 unique studies with 57 531 unique patients and showed the following axillary pCR rates for each of the 7 reported subtypes in decreasing order: 60% for hormone receptor (HR)–negative/ERBB2 (formerly HER2)–positive, 59% for ERBB2-positive (HR-negative or HR-positive), 48% for triple-negative, 45% for HR-positive/ERBB2-positive, 35% for luminal B, 18% for HR-positive/ERBB2-negative, and 13% for luminal A breast cancer. No major differences were found in the axillary pCR rates per subtype by analyzing separately the studies of patients with and without pathologically proven clinically node-positive disease before neoadjuvant systemic therapy.

Conclusions and Relevance

The HR-negative/ERBB2-positive subtype was associated with the highest axillary pCR rate. These data may help estimate axillary treatment response in the neoadjuvant setting and thus select patients for more or less invasive axillary procedures.

Introduction

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NST) is often considered in patients with axillary lymph node involvement at diagnosis (cN-positive disease). Neoadjuvant systemic therapy may result in complete eradication of invasive cancer in the breast and axillary lymph nodes, defined as pathologic complete response (pCR), which is associated with improved survival compared with residual disease after NST.1,2,3 Previous studies4,5,6 have reported that axillary pCR has a greater effect on disease-free and overall survival than pCR of the primary breast tumor.

Axillary pCR not only provides prognostic information but may also lead to the omission of conventional axillary lymph node dissection (ALND). Different less invasive axillary staging procedures have been introduced to identify patients with axillary pCR to minimize the risk of morbidity.7,8,9 However, the lack of long-term oncologic safety data and the overall false-negative rates of these less invasive staging procedures are a concern, and, therefore, ALND is still often performed in current clinical practice.7,9,10,11,12 Identifying patients in whom axillary pCR is most likely can improve patient selection for less invasive staging procedures. In this systematic review and meta-analysis of patients with cN-positive disease treated with NST, the aim was to provide pooled data of axillary pCR rates for different breast cancer subtypes and their association with survival.

Methods

Systematic Literature Search

For this systematic review and meta-analysis, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were applicable.13 Embase and PubMed were searched on July 16, 2020, for studies assessing axillary pCR and/or survival outcomes for different breast cancer subtypes in patients with initially cN-positive disease. Details of both search strategies are provided in eMethods 1 and 2 in the Supplement.

Eligibility Criteria for Study Inclusion

Studies were eligible for inclusion if the axillary pCR rates were reported for 1 or more different subtypes in patients with cN-positive disease, including studies with and without pathologically proven axillary lymph node metastases at diagnosis before NST. Studies that assessed survival were eligible only if they included patients who had pathologically proven cN-positive disease. Female patients with breast cancer had to be treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, with or without ERBB2 (formerly HER2)–targeted therapy, followed by any type of axillary surgery. Studies based on neoadjuvant endocrine or radiation therapy, with fewer than 10 patients per subtype, or with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) performed before NST, were excluded. Only randomized clinical trials, case-control studies, and cohort studies published in English were included.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of this study was the rate of axillary pCR and residual axillary lymph node disease after NST for different breast cancer subtypes, differentiating studies with and without patients with pathologically proven cN-positive disease. The secondary outcome of this study was survival divided by axillary pCR and residual axillary lymph node disease for different subtypes.

Study Selection

The title and abstract of all studies were independently screened by 2 reviewers (S.S. and J.M.S.). Afterward, the full text of each remaining study was read and assessed for eligibility. In addition, the reference lists of the included studies were manually checked to identify further eligible studies.

Data Extraction and Analysis

The following study characteristics were extracted from the included studies by the 2 reviewers independently: first author, year of publication, country, study design, evaluable sample size, clinical tumor and nodal stage, definition of subtypes, NST regimens, type of axillary surgery, and definition of axillary pCR. Discrepancies of data extraction were resolved during a consensus meeting. The extracted data were divided by studies with and without patients with pathologically proven cN-positive disease. The first group included only studies in which the whole study population had cytologically or pathologically proven axillary lymph node metastases. In studies without patients with pathologically proven cN-positive disease, nodal positivity was based on physical examination and imaging findings, or only part of the study population had pathologically proven axillary lymph node metastases. The statistical analyses were performed in Stata/SE, version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC). The random-effects model for meta-analysis in the metaprop command of Stata/SE was used to calculate the overall pooled estimate of axillary pCR for each subtype, regardless of the type of axillary surgery.14 A subanalysis was performed for studies with the reference standard ALND and for axillary pCR definition. The computed variation of axillary pCR effect size estimates with 95% CI and weights for each subtype was visualized in forest plots divided into studies of patients with and without (or not always) pathologically proven cN-positive disease. The variability of axillary pCR estimates due to heterogeneity among the included studies was quantified using the I2 index.15 The χ2 test was used to assess statistical heterogeneity. Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Systematic Literature Search and Study Selection

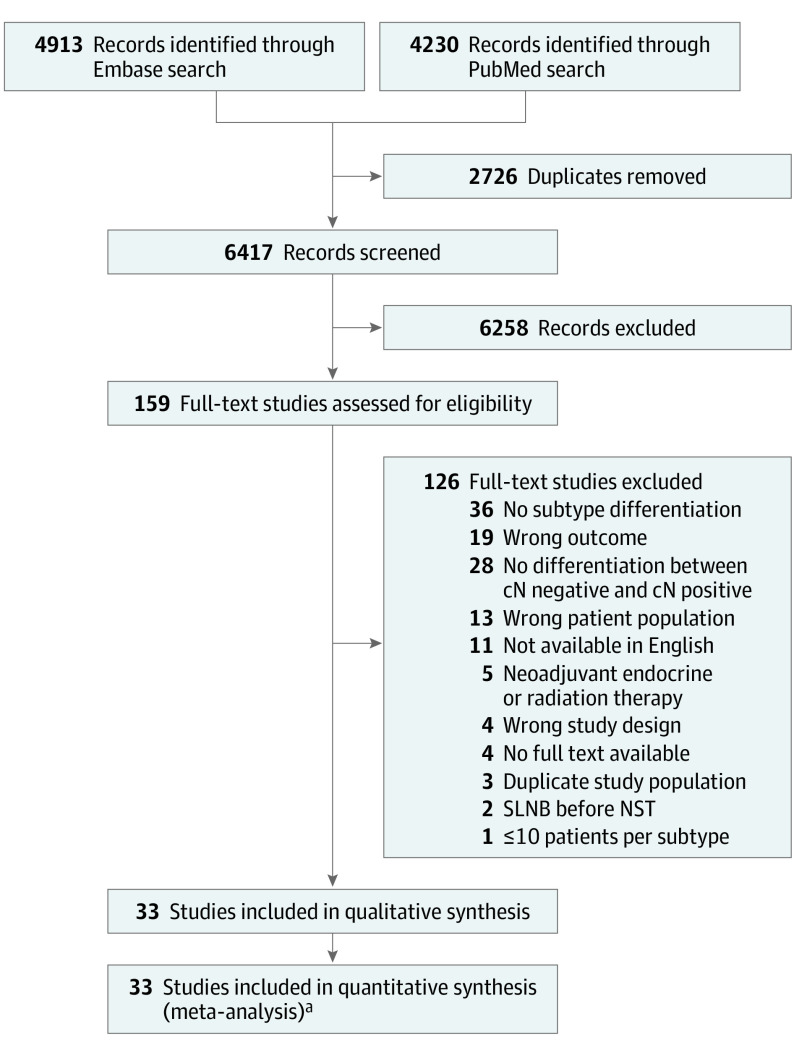

A total of 9143 records were identified from the systematic literature, of which 2726 duplicate records were removed. After title and abstract screening of the remaining records, 159 studies were selected for full-text review. Eventually, 33 studies6,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 were included for qualitative and quantitative analysis after full-text assessment. The flow diagram of study selection is shown in Figure 1. Assessment of the reference lists did not yield further eligible articles. All 33 included studies reported on axillary pCR rates for different subtypes, and 1 of the 33 studies16 reported on survival outcome of axillary pCR and residual axillary lymph node disease for different subtypes.

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram for Study Selection.

NST indicates neoadjuvant systemic therapy; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

aIncludes 33 studies on axillary pCR rates, of which 1 study also reported on the second study aim of survival outcome.

Study Characteristics

A total of 57 531 patients were included. In 23 studies (9961 patients),6,16,17,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38 all the patients had pathologically proven axillary lymph node metastases before NST. In the remaining 10 studies (47 570 patients),18,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 nodal positivity was solely based on results of the physical examination and imaging, or only part of the study population had pathologically proven axillary lymph node metastases before NST. The Table depicts the general characteristics of all included studies. Most studies (20 of 33) included cT1 to cT4 disease. Axillary pCR was defined as ypN0 in 15 studies,19,21,23,25,26,30,31,32,34,38,39,41,43,44,47 as ypN0 with isolated tumor cells (itc) in 15 studies,6,16,18,22,24,28,29,33,35,36,37,40,42,45,46 as ypN0/itc with micrometastases (mi) in 1 study,20 and not reported in 2 studies.17,27 Axillary lymph node dissection was routinely performed in all patients in 18 of the 33 studies.6,16,19,20,22,25,26,28,29,30,31,33,35,36,38,40,41,43 In the other studies, either SLNB or targeted axillary dissection (TAD) with or without ALND was performed. In total, 7 different subtypes were identified, and each patient was included only in 1 subtype: hormone receptor (HR)–positive/ERBB2-positive, HR-positive/ERBB2-negative, HR-negative/ERBB2-positive, triple-negative, ERBB2-positive (unknown whether HR-positive or HR-negative), luminal A (HR-positive, ERBB2-negative, low levels of Ki-67), luminal B/ERBB2-negative (HR-positive, ERBB2-negative, high levels of Ki-67), and luminal B/ERBB2-positive (HR-positive, ERBB2-positive, any Ki-67 level).

Table. General Characteristics of Included Studies in Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis, Divided by Studies of Patients With and Without Pathologically Proven Clinically Node-Positive Disease.

| Source | Country | Center | Study type | No. of participants | cT category | cN category | Cancer subtype | NST | Axillary surgery | Definition of axillary pCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies of patients with pathologically proven clinically node-positive disease | ||||||||||

| Al-Hatalli et al,20 2019 | UK | Single | Retrospective | 87 | 1-4 | 1-3 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and/or taxane with or without trastuzumab | ALND | ypN0/itc/mi |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Bi et al,21 2019 | China | Single | Retrospective | 495 | 1-4 | 1-3 | ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and taxane with or without trastuzumab | SLNB, ALND | ypN0 |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Boughey et al,22 2017 | US | Multiple | Prospective | 701 | 0-3 | 1-2 | ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and/or taxane with or without trastuzumab; no anthracycline and no taxane | ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Cerbelli et al,23 2019 | Italy | Single | Retrospective | 181 | 1-4 | 1-3 | Luminal A | Anthracycline, cyclophosphamide, and taxane with or without trastuzumab | SLNB, ALND | ypN0 |

| Luminal B/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| Luminal B/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Choi et al,24 2019 | Korea | Single | Retrospective | 844 | 1-3 | 1-3 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and/or taxane with or without trastuzumab | SLNB, ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Dominici et al,6 2010 | US | Single | Prospective | 109 | 0-4 | 1-3 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline or taxane with or without trastuzumab | ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| Enokido et al,25 2016 | Japan | Multiple | Prospective | 130 | 1-3 | 1 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | NR | ALND | ypN0 |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Fernandez-Gonzalez et al,16 2020 | Spain | Single | Retrospective | 330 | 0-4 | 1-2 | Luminal A | Anthracycline and taxane with or without trastuzumab | ALND | ypN0/itc |

| Luminal B/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| Luminal B/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Glaeser et al,26 2019 | Germany | Single | Retrospective | 72 | 1-4 | 1-3 | ERBB2 positive | Taxane with or without trastuzumab | ALND | ypN0 |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Ha et al,27 2018 | US | Single | Retrospective | 127 | NR | NR | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and taxane | SLNB, ALND | NR |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Kim et al,28 2019 | Korea | Single | Retrospective | 244 | 1-4 | 1-3 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and taxane with or without trastuzumab | ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Kim et al,29 2015 | Korea | Single | Retrospective | 415 | 1-4 | 1-3 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and/or taxane; no anthracycline and no taxane | ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Koolen et al,30 2013 | The Netherlands | Single | Prospective | 80 | 1-4 | 1-3 | ERBB2 positive | Taxane, platinum, and trastuzumab; anthracycline and cyclophosphamide | ALND | ypN0 |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Li et al,31 2014 | China | Single | Retrospective | 157 | 1-4 | 1-3 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Taxane, platinum, and trastuzumab | ALND | ypN0 |

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| Mougalian et al,17 2016 | US | Single | Retrospective | 1346 | 0-4 | 1-3 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and/or taxane with or without trastuzumab | SLNB, ALND | NR |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Park et al,32 2017 | Korea | Single | Retrospective | 86 | 1-4a | 1-3 | ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and/or taxane with or without trastuzumab | SLNB | ypN0 |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Park et al,33 2013 | Korea | Single | Retrospective | 169 | 1-3 | NR | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and/or taxane with or without trastuzumab | ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Qu et al,34 2018 | US | Single | Retrospective | 59 | NR | NR | ERBB2 positive | NR | TAD, ALND | ypN0 |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Samiei et al,35 2019 | The Netherlands | Multiple | Retrospective | 2410 | 1-3 | 1 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline, cyclophosphamide, with or without taxane or fluorouracil | ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Schipper et al,36 2014 | The Netherlands | Multiple | Retrospective | 291 | 1-4 | NR | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and cyclophosphamide with or without taxane | ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Tadros et al,37 2017 | US | Single | Retrospective | 237 | 1-2 | 1 | ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline and/or taxane with or without trastuzumab with or without pertuzumab | NR | ypN0/itc |

| TN | ||||||||||

| van Nijnatten et al,19 2017 | The Netherlands | Multiple | Retrospective | 1258 | 0-4a | NR | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline, cyclophosphamide, and taxane or fluorouracil with or without trastuzumab | ALND | ypN0 |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Wu et al,38 2019 | China | Single | Prospective | 133 | 0-3 | 1-3 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | Taxane with or without anthracycline or platinum with or without trastuzumab with or without pertuzumab | ALND | ypN0 |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Studies of patients without pathologically proven clinically node-positive disease (or only part of the study population) | ||||||||||

| DiMicco et al,39 2019 | Italy | Single | Retrospective | 176 | 1-4 | NR | Luminal A | Anthracycline and taxane | SLNB, ALND | ypN0 |

| Luminal B | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Fayanju et al,18 2018 | US | Multiple | Retrospective | 15 078 | 1-3 | 1 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | NR | SLNB, ALNDb | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Gentile et al,40 2017 | US | Single | Retrospective | 310 | 1-4 | 1-3 | ERBB2 positive | Anthracycline, cyclophosphamide with or without taxane; cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil; cyclophosphamide, taxane, with or without vinorelbine; taxane only; platinum only; anthracycline and taxane | ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Kantor et al,41 2018 | US | Multiple | Retrospective | 18 052 | 1-4a | 1-3 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | NR | ALND | ypN0 |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Lee et al,42 2019 | US | Single | Retrospective | 195 | 1-4 | 1-3 | ERBB2 positive | NR | SLNB, ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Ouldamer et al,43 2018 | France | Single | Retrospective | 116 | 2-4 | 1 | Luminal A | NR | ALND | ypN0 |

| Luminal B | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Petruolo et al,44 2017 | US | Single | Retrospective | 297 | 1-4a | 1-3 | HR positive/ERBB2 negative | Anthracycline, cyclophosphamide, and taxane | NR | ypN0 |

| Resende et al,45 2018 | Brazil | Single | Retrospective | 228 | 1-4 | 1-3 | Luminal A | Anthracycline, cyclophosphamide, and taxane with or without platinum | NR | ypN0/itc |

| Luminal B | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Steiman et al,46 2016 | US | Single | Retrospective | 135 | NR | 1-3 | ERBB2 positive | NR | SLNB, ALND | ypN0/itc |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

| Wong et al,47 2019 | US | Multiple | Retrospective | 12 983 | 1-3 | 1-2 | HR positive/ERBB2 positive | NR | SLNB, ALND | ypN0 |

| HR positive/ERBB2 negative | ||||||||||

| HR negative/ERBB2 positive | ||||||||||

| TN | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; HR, hormone receptor; itc, isolated tumor cells; mi, micrometastases; NR, not reported; NST, neoadjuvant systemic therapy; pCR, pathologic complete response; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; TAD, targeted axillary dissection; TN, triple negative.

Clinical tumor stage was not available in a small number of patients.

Axillary surgery was defined by the number of lymph nodes removed.

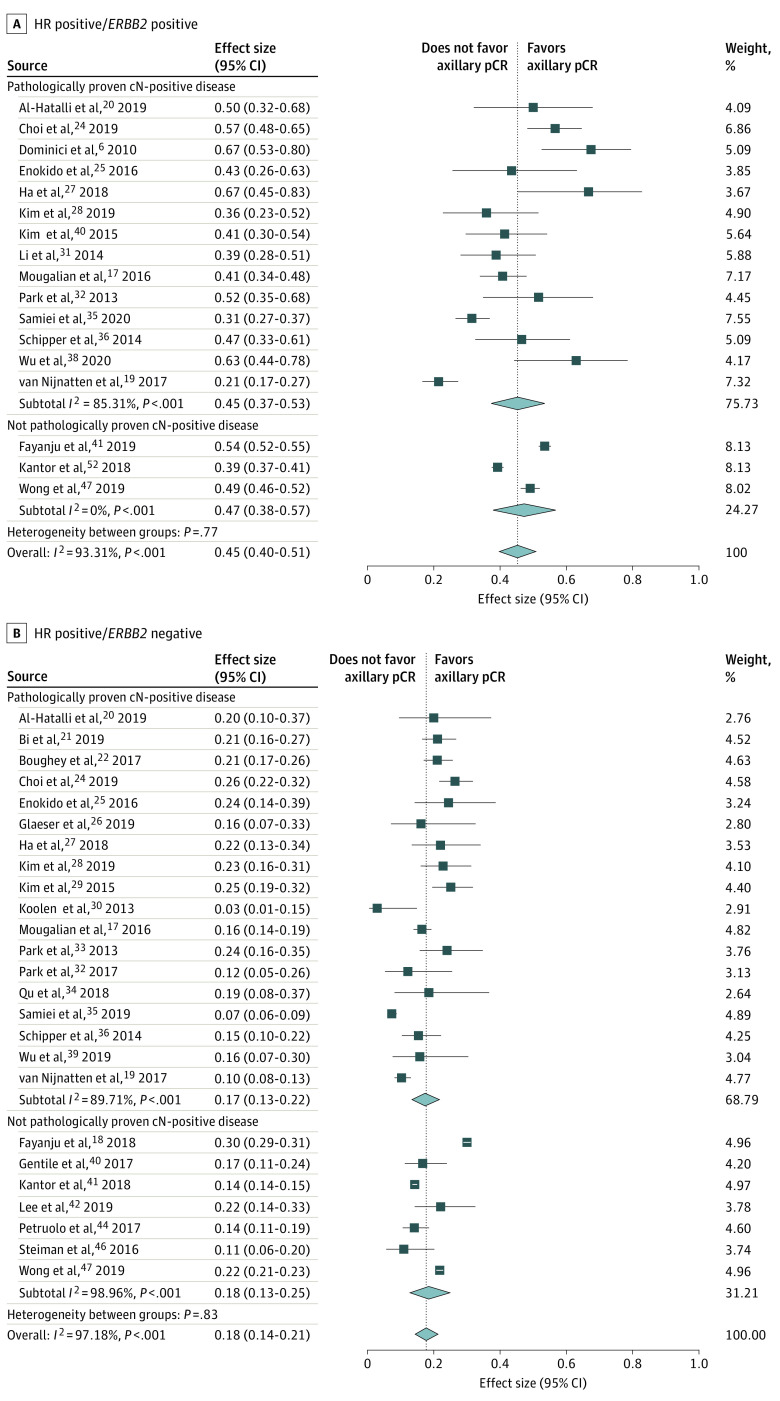

HR-Positive/ERBB2-Positive Breast Cancer

Seventeen studies6,17,18,19,20,24,25,27,28,29,31,33,35,36,38,41,47 including 8168 patients reported on HR-positive/ERBB2-positive breast cancer: 1225 with pathologically proven and 6943 without (or not always) pathologically proven cN-positive disease (Figure 2A). In 12 studies (3730 patients),6,19,20,25,28,29,31,33,35,36,38,41 the reference standard was ALND, and in 5 studies (4438 patients),17,18,24,27,47 it was SLNB or ALND. Axillary pCR was defined as ypN0/itc/mi in 1 study (26 patients),20 ypN0/itc in 8 studies (3612 patients),6,18,24,28,29,33,35,36 ypN0 in 6 studies (4325 patients),19,25,31,38,41,47 and not reported in 2 studies (205 patients).17,27 The overall pooled axillary pCR rate was 45% (95% CI, 40%-51%) (45% [95% CI, 37%-53%] for patients with pathologically proven and 47% [95% CI, 38%-57%] for those without [or not always] pathologically proven cN-positive disease) (eTable in the Supplement). Between the studies, significant heterogeneity was seen with an I2 index of 93.31% (P < .001). The pooled axillary pCR rate was 42% for studies with the reference standard ALND. Regarding pCR definition, the pooled axillary pCR rate was 48% for ypN0/itc and 40% for ypN0.

Figure 2. Forest Plots of Axillary Pathologic Complete Response (pCR) for Hormone Receptor (HR)–Positive/ERBB2-Positive and HR-Positive/ERBB2-Negative Breast Cancer Subtypes.

HR indicates hormone receptor. Diamonds indicate effect size.

HR-Positive/ERBB2-Negative Breast Cancer

Twenty-five studies17,18,19,20,21,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,38,40,42,44,46,47 including 26 322 patients reported on HR-positive/ERBB2-negative breast cancer: 4340 with pathologically proven and 21 982 without (or not always) pathologically proven cN-positive disease (Figure 2B). In 14 studies (11 921 patients),19,20,22,25,26,28,29,30,33,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 the reference standard was ALND; in 8 studies (14 036 patients),17,18,21,24,27,42,46,47 SLNB or ALND; in 1 study (27 patients),34 TAD or ALND; in 1 study (41 patients),32 SLNB; and in 1 study (297 patients),44 was not reported. Axillary pCR was defined as ypN0/itc/mi in 1 study (30 patients),20 ypN0/itc in 11 studies (9326 patients),18,22,24,28,29,33,35,36,40,42,46 ypN0 in 11 studies (16 188 patients),19,21,25,26,30,32,34,38,41,44,47 and not reported in 2 studies (778 patients).17,27 The pooled axillary pCR rate was 18% (95% CI, 14%-21%) (17% [95% CI, 13%-25%] for pathologically proven and 18% [95% CI, 13%-25%] for not [or not always] pathologically proven cN-positive disease) (eTable in the Supplement). Between the studies, significant heterogeneity was seen with an I2 index of 97.18% (P < .001). The pooled axillary pCR rate was 16% for studies with the reference standard ALND. Regarding pCR definition, the pooled axillary pCR rate was 20% for ypN0/itc and 15% for ypN0.

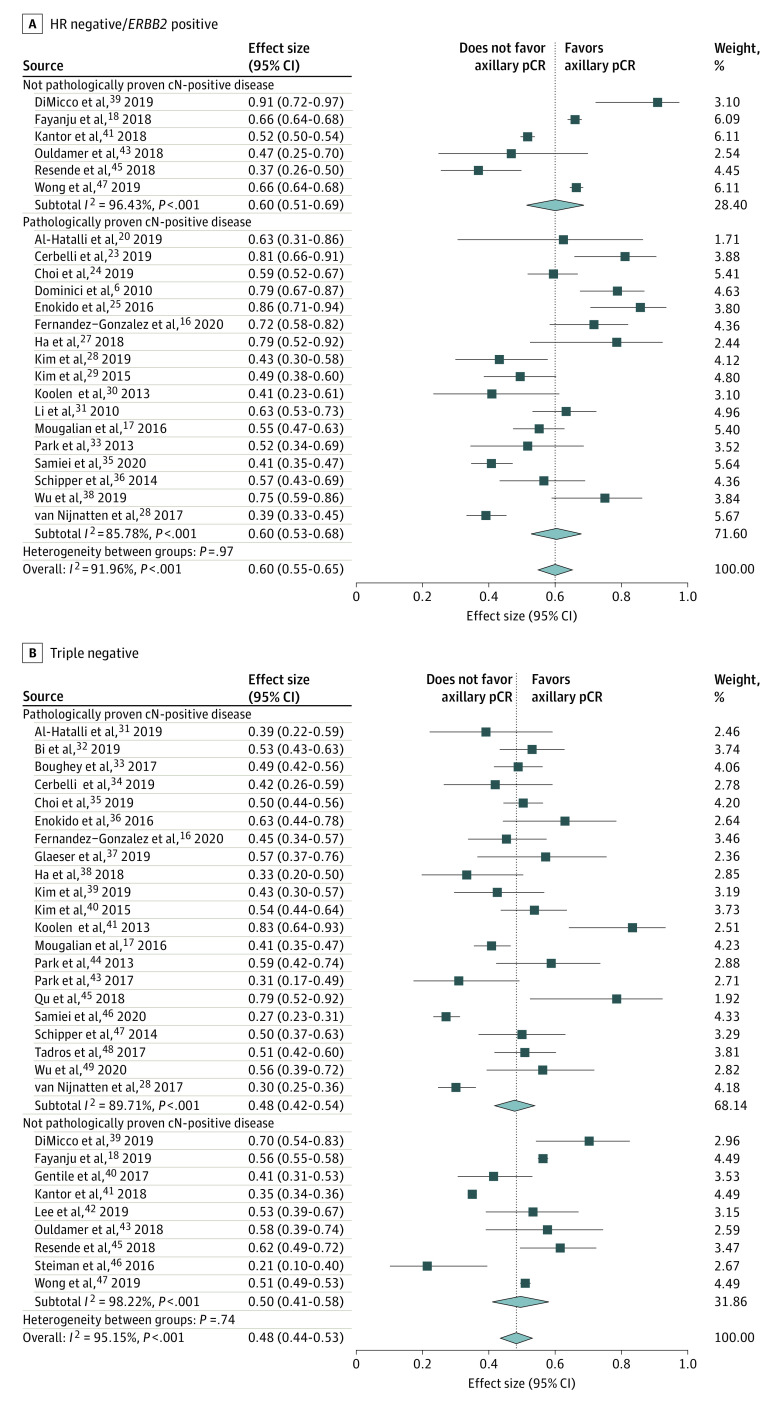

HR-Negative/ERBB2-Positive Breast Cancer

Twenty-three studies6,16,17,18,19,20,23,24,25,27,28,29,30,31,33,35,36,38,39,41,43,45,47 including 7132 patients reported on HR-negative/ERBB2-positive breast cancer: 1357 with pathologically proven and 5775 without (or not always) pathologically proven cN-positive disease (Figure 3A). In 15 studies (3034 patients),6,16,20,25,28,29,30,31,33,35,36,37,38,41,43 the reference standard was ALND; in 7 studies (4041 patients),17,18,23,24,27,39,47 SLNB or ALND; and in 1 study (57 patients),45 not reported. Axillary pCR was defined as ypN0/itc/mi in 1 study (8 patients),20 ypN0/itc in 10 studies (2440 patients),6,16,18,24,25,28,29,33,35,36 ypN0 in 10 studies (4516 patients),19,21,25,30,31,38,39,41,43,47 and not reported in 2 studies (168 patients).17,27 The pooled axillary pCR was 60% (95% CI, 55%-65%) (60% [95% CI, 53%-68%] for patients with and 60% [95% CI, 51%-69%] for those without [or not always] pathologically proven cN-positive disease) (eTable in the Supplement). Between the studies, significant heterogeneity was seen with an I2 index of 91.96% (P < .001). The pooled axillary pCR rate was 57% for studies with the reference standard ALND. Regarding pCR definition, the pooled axillary pCR rate was 56% for ypN0/itc and 64% for ypN0.

Figure 3. Forest Plots of Axillary Pathologic Complete Response (pCR) for Hormone Receptor–Negative/ERBB2-Positive and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Subtypes.

HR indicates hormone receptor. Diamonds indicate effect size.

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

Thirty studies16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47 including 14 521 patients reported on triple-negative breast cancer: 2164 with pathologically proven and 12 357 without (or not always) pathologically proven cN-positive disease (Figure 3B). In 16 studies (5759 patients),16,19,20,22,25,26,28,29,30,33,35,36,38,40,41,43 the reference standard was ALND; in 10 studies (8548 patients),17,18,21,23,24,27,39,42,46,47 SLNB or ALND; in 1 study (14 patients),34 TAD or ALND; in 1 study (29 patients),32 SLNB; and in 2 studies (171 patients),37,45 not reported. Axillary pCR was defined as ypN0/itc/mi in 1 study (23 patients),20 ypN0/itc in 14 studies (5449 patients),16,18,22,24,28,29,33,35,36,37,40,42,45,46 ypN0 in 13 studies (8727 patients),19,21,23,25,26,30,32,34,38,39,41,43,47 and not reported in 2 studies (322 patients).17,27 The pooled axillary pCR rate was 48% (95% CI, 44%-53%) (48% [95% CI, 42%-54%] for pathologically proven and 50% [95% CI, 41%-58%] for not [or not always] pathologically proven cN-positive disease) (eTable in the Supplement). Between the studies, significant heterogeneity was seen with an I2 index of 95.15% (P < .001). The pooled axillary pCR rate was 47% for studies with the reference standard ALND. Regarding pCR definition, the pooled axillary pCR rate was 47% for ypN0/itc and 52% for ypN0.

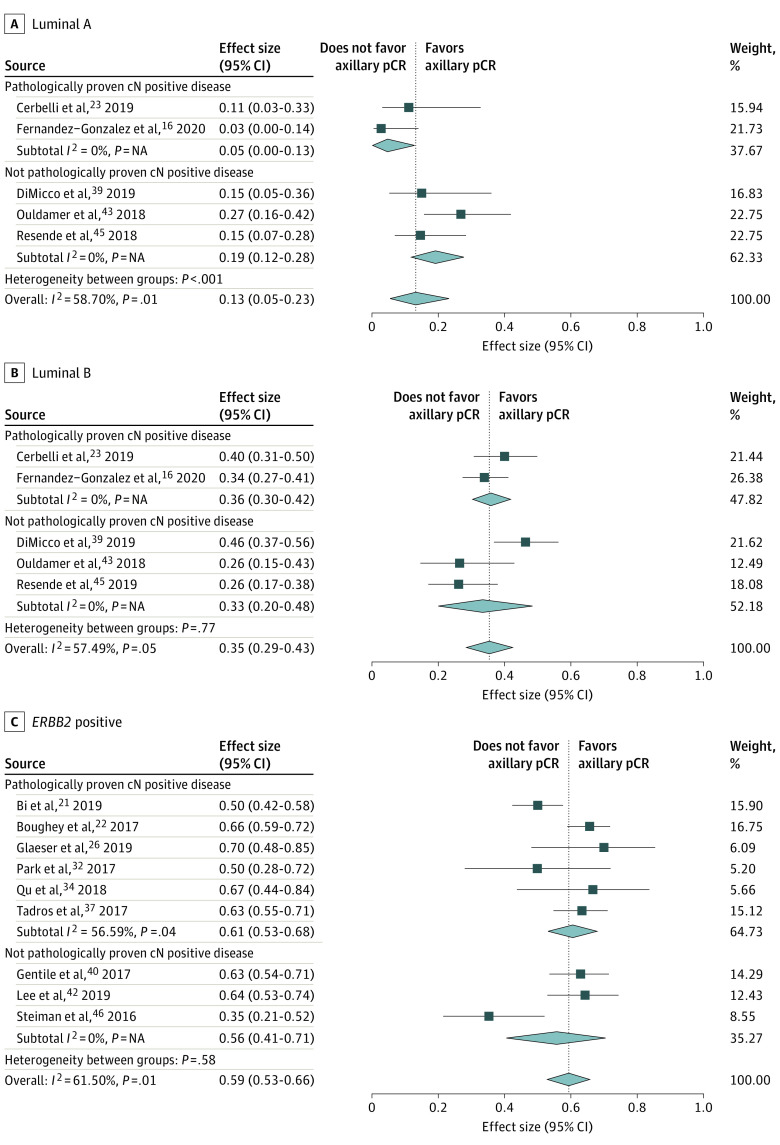

Luminal A Breast Cancer

Five studies16,23,39,43,45 including 156 patients reported on luminal A breast cancer: 54 with pathologically proven and 102 without (or not always) pathologically proven cN-positive disease (Figure 4A). In 2 studies (77 patients),16,43 the reference standard was ALND; in 2 studies (38 patients),23,39 SLNB or ALND; and in 1 study (41 patients),45 not reported. Axillary pCR was defined as ypN0/itc in 2 studies (77 patients)16,45 and ypN0 in 3 studies (79 patients).23,39,43 The pooled axillary pCR rate was 13% (95% CI, 5%-23%) (5% [95% CI, 0%-13%] for pathologically proven and 19% [95% CI, 12%-28%] for not [or not always] pathologically proven cN-positive disease) (eTable in the Supplement). Between the studies, heterogeneity was seen with an I2 index of 58.70% (P = .05). The pooled axillary pCR rate was 13% for studies with the reference standard ALND. Regarding pCR definition, the pooled axillary pCR rate was 8% for ypN0/itc and 20% for ypN0.

Figure 4. Forest Plots of Axillary Pathologic Complete Response (pCR) for 3 Breast Cancer Subtypes.

Diamonds indicate effect sizes. NA indicates not applicable.

Luminal B Breast Cancer

Five studies16,23,39,43,45 including 468 patients reported on luminal B breast cancer: 272 with pathologically proven and 196 without (or not always) pathologically proven cN-positive disease (Figure 4B). In 2 studies (211 patients),16,43 the reference standard was ALND; in 2 studies (192 patients),23,39 SLNB or ALND; and in 1 study (65 patients),45 not reported. Axillary pCR was defined as ypN0/itc in 2 studies (242 patients)16,45 and ypN0 in 3 studies (226 patients).23,39,43 The pooled axillary pCR rate was 35% (95% CI, 29%-43%) (36% [95% CI, 30%-42%] for pathologically proven and 33% [95% CI, 20%-48%] for not [or not always] pathologically proven cN-positive disease) (eTable in the Supplement). Between the studies, heterogeneity was seen with an I2 index of 57.49% (P = .05). The pooled axillary pCR rate was 33% for studies with the reference standard ALND. Regarding pCR definition, the pooled axillary pCR rate was 32% for ypN0/itc and 39% for ypN0.

ERBB2-Positive Breast Cancer

Nine studies21,22,26,32,34,37,40,42,46 including 764 patients reported on ERBB2-positive breast cancer: 549 with pathologically proven and 215 without (or not always) pathologically proven cN-positive disease (Figure 4C). In 3 studies (332 patients),22,26,40 the reference standard was ALND; in 3 studies (267 patients),21,42,46 SLNB or ALND; in 1 study (18 patients),34 TAD or ALND; in 1 study (16 patients),32 SLNB; and in 1 study (131 patients),37 not reported. Axillary pCR was defined as ypN0/itc in 5 studies (550 patients)22,37,40,42,46 and ypN0 in 4 studies (214 patients).21,26,32,34 The pooled axillary pCR rate was 59% (95% CI, 53%-66%) (61% [95% CI, 53%-68%] for pathologically proven and 56% [95% CI, 41%-71%] for not [or not always] pathologically proven cN-positive disease) (eTable in the Supplement). Between the studies, significant heterogeneity was seen with an I2 index of 61.50% (P = .01). The pooled axillary pCR rate was 65% for studies with the reference standard ALND. Regarding pCR definition, the pooled axillary pCR rate was 61% for ypN0/itc and 56% for ypN0.

Survival by Axillary Treatment Response and Subtype

Fernandez-Gonzalez et al16 evaluated 330 patients with pathologically proven cN-positive disease treated with NST and subsequent ALND: 36 with luminal A, 115 with luminal B (ERBB2-negative), 62 with luminal B (ERBB2-positive), 53 with HR-negative/ERBB2-positive, and 64 with triple-negative breast cancer. For all subtypes, distant disease–free survival (defined as the time from the initiation of NST until distant recurrence, second primary cancer, or death due to any cause) and overall survival were improved for patients with axillary pCR compared with those with residual axillary lymph node disease. The differences in distant disease–free survival and overall survival between subtypes were minimal in patients who achieved axillary pCR.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis, to our knowledge, to investigate axillary pCR rates for different breast cancer subtypes, for patients both with and without (or not always) pathologically proven clinically node-positive disease. All 7 subtypes reported in the included articles were incorporated into the analysis to increase the clinical utility of the results. The pooled analysis of 57 531 patients showed that the HR-negative/ERBB2-positive subtype was associated with the highest axillary pCR rate (60%). In decreasing order, the remaining subtypes were associated with the following axillary pCR rates: 59% for ERBB2-positive, 48% for triple-negative, 45% for HR-positive/ERBB2-positive, 35% for luminal B, 18% for HR-positive/ERBB2-negative, and 13% for luminal A breast cancer. In general, no major differences were found in the axillary pCR rates by analyzing separately the studies including patients with and without pathologically proven cN-positive disease.

Houssami et al3 performed a meta-analysis on this association and found that the triple-negative and HR-negative/ERBB2-positive subtypes have the highest chance of achieving a pCR. Contrary to the meta-analysis of Houssami et al,3 the current meta-analysis only included patients with cN-positive disease and specifically focused on axillary pCR rather than overall or breast-only pCR. Equal to the meta-analysis by Houssami et al,3 the triple-negative and HR-negative/ERBB2-positive subtypes were associated with the highest pCR rates. In addition to the association between treatment response and subtype, multiple studies have reported on the strong positive correlation between pCR and survival. In a pooled analysis of 12 studies of patients with breast cancer treated in the neoadjuvant setting, Cortazar et al1 reported that a pCR of both the breast and axilla was associated with improved survival compared with a pCR of the breast, irrespective of axillary treatment response. This correlation was especially strong in the triple-negative and HR-negative/ERBB2-positive (treated with ERBB2-targeted therapy) subtypes. Furthermore, a few studies have reported the effect on survival in patients with cN-positive breast cancer who achieved an axillary pCR. In these patients, it seems that achieving a pCR of the axilla has a greater effect on survival than achieving a breast pCR. In a study of 1600 patients with cN-positive disease, Mougalian et al17 found that patients with an axillary pCR but residual breast disease have improved survival compared with patients with a breast pCR but residual axillary disease. Fayanju et al18 reported that the prognostic impact of breast-only pCR or axilla-only pCR depends on subtype. In the current meta-analysis, only 1 study16 included reported on survival for different subtypes stratified by axillary treatment response. This study suggested that in the case of axillary pCR, survival is no longer substantially different among subtypes. Further research is needed to determine whether the correlation between axillary pCR and survival may vary among different subtypes.

To avoid overtreatment of the axilla in patients with cN-positive disease who achieve an axillary pCR, several less invasive staging procedures have been proposed to replace ALND. Among these are SLNB,48,49,50 the removal of the pretreatment positive lymph node (for example, the MARI [marking axillary lymph node with radioactive iodine seeds] procedure),9 and TAD7 (excision of both the pretreatment marked positive lymph node and the SLN[s]). In a meta-analysis on the diagnostic accuracy of these different staging procedures,51 TAD appeared to be most accurate. However, strong evidence to confirm this is lacking. Moreover, whether the accuracy of less invasive staging procedures depends on subtype remains unknown. In the current meta-analysis, pooled axillary pCR rates were generally lower for studies in which all patients had undergone ALND. This can be explained by the superior diagnostic accuracy of ALND and, consequently, increased detection of residual axillary disease. Whether the diminished accuracy of these less invasive staging procedures compared with ALND impairs long-term survival remains unknown. Despite the lack of evidence on long-term outcomes of patients with cN-positive disease in whom ALND is omitted after NST, ALND is already increasingly being replaced by less invasive staging procedures.52,53,54 This trend is occurring in all subtypes. Therefore, data on long-term outcomes are urgently needed to further advance response-based treatment while considering tumor biology.

The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis may have implications not only for patients with axillary pCR but also for patients with residual axillary disease. Two recent trials reported on the benefit of treatment with additional adjuvant systemic therapy in patients with residual disease after NST. In the KATHERINE trial,55 patients with ERBB2-positive cancer and residual disease were treated with adjuvant trastuzumab emtansine, and in the CREATE-X trial,56 patients with ERBB2-negative cancer and residual disease were treated with adjuvant capecitabine. Both trials reported improved disease-free survival. These trials demonstrated that adequate assessment of treatment response is pivotal. The data of the current review can help estimate axillary treatment response and thus improve patient selection for appropriate axillary staging and adjuvant treatment.

Limitations

This review is limited by the heterogeneity of the included studies. To account for the different definitions of cN-positive disease and pCR, and for the extent of axillary surgery, subanalyses were performed. We expected that studies with pathologically proven cN-positive disease would show a lower overall axillary pCR rate. However, the differences found in this meta-analysis were not substantial, except for luminal A breast cancer, which could have been caused by the small number of patients and/or tumor heterogeneity. The small differences in the other subtypes can be explained by the fact that a part of the study population had pathologically proven cN-positive disease. Conflicting results have been published regarding the prognosis of ypN0 and residual isolated tumor cells and/or micrometastases.19,57,58 In the present study, both decreased and increased axillary pCR rates were observed depending on subtype when ypN0 was compared with ypN0/itc. Further research is needed to determine the optimal definition of axillary pCR and whether limited residual nodal disease should be regarded as a separate entity. Apart from this, most studies classified subtypes based on traditional markers, and data were limited for molecularly classified subtypes (including Ki-67 status).

Conclusions

Axillary pCR rates in patients with initially cN-positive breast cancer who are treated with NST strongly depend on subtype. The HR-negative/ERBB2-positive subtype had the highest pooled axillary pCR rate. Whether the correlation between axillary pCR and survival is stronger in certain subtypes is still unknown. Data on long-term outcomes stratified by subtype, axillary treatment response, and the extent of surgery are urgently needed, especially in an era when ALND is increasingly being replaced by less invasive staging procedures.

eMethods 1. Embase Search

eMethods 2. PubMed Search

eTable. Pooled Axillary pCR Rate for Different Breast Cancer Subtypes, Divided by Patients With and Without Pathologically Proven Clinically Node-Positive Disease

References

- 1.Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, et al. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 2014;384(9938):164-172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Brown A, Mamounas E, et al. Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on local-regional disease in women with operable breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-18. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(7):2483-2493. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.7.2483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houssami N, Macaskill P, von Minckwitz G, Marinovich ML, Mamounas E. Meta-analysis of the association of breast cancer subtype and pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(18):3342-3354. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hennessy BT, Hortobagyi GN, Rouzier R, et al. Outcome after pathologic complete eradication of cytologically proven breast cancer axillary node metastases following primary chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9304-9311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rouzier R, Extra JM, Klijanienko J, et al. Incidence and prognostic significance of complete axillary downstaging after primary chemotherapy in breast cancer patients with T1 to T3 tumors and cytologically proven axillary metastatic lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(5):1304-1310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dominici LS, Negron Gonzalez VM, Buzdar AU, et al. Cytologically proven axillary lymph node metastases are eradicated in patients receiving preoperative chemotherapy with concurrent trastuzumab for HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(12):2884-2889. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caudle AS, Yang WT, Krishnamurthy S, et al. Improved axillary evaluation following neoadjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer using selective evaluation of clipped nodes: implementation of targeted axillary dissection. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(10):1072-1078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Nijnatten TJA, Simons JM, Smidt ML, et al. A novel less-invasive approach for axillary staging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with axillary node-positive breast cancer by combining radioactive iodine seed localization in the axilla with the sentinel node procedure (RISAS): a Dutch prospective multicenter validation study. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17(5):399-402. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2017.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donker M, Straver ME, Wesseling J, et al. Marking axillary lymph nodes with radioactive iodine seeds for axillary staging after neoadjuvant systemic treatment in breast cancer patients: the MARI procedure. Ann Surg. 2015;261(2):378-382. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vugts G, Maaskant-Braat AJG, de Roos WK, Voogd AC, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP. Management of the axilla after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for clinically node positive breast cancer: a nationwide survey study in the Netherlands. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(7):956-964. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caudle AS, Bedrosian I, Milton DR, et al. Use of sentinel lymph node dissection after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer at diagnosis: practice patterns of American Society of Breast Surgeons Members. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(10):2925-2934. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5958-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Nijnatten TJ, Schipper RJ, Lobbes MB, Nelemans PJ, Beets-Tan RG, Smidt ML. The diagnostic performance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in pathologically confirmed node positive breast cancer patients after neoadjuvant systemic therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(10):1278-1287. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, et al. ; and the PRISMA-DTA Group . Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA. 2018;319(4):388-396. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a STATA command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539-1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez-Gonzalez S, Falo C, Pla MJ, et al. Predictive factors for omitting lymphadenectomy in patients with node-positive breast cancer treated with neo-adjuvant systemic therapy. Breast J. 2020;26(5):888-896. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mougalian SS, Hernandez M, Lei X, et al. Ten-year outcomes of patients with breast cancer with cytologically confirmed axillary lymph node metastases and pathologic complete response after primary systemic chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(4):508-516. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fayanju OM, Ren Y, Thomas SM, et al. The clinical significance of breast-only and node-only pathologic complete response (pCR) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT): a review of 20,000 breast cancer patients in the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB). Ann Surg. 2018;268(4):591-601. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Nijnatten TJ, Simons JM, Moossdorff M, et al. Prognosis of residual axillary disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in clinically node-positive breast cancer patients: isolated tumor cells and micrometastases carry a better prognosis than macrometastases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;163(1):159-166. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4157-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Hattali S, Vinnicombe SJ, Gowdh NM, et al. Breast MRI and tumour biology predict axillary lymph node response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Cancer Imaging. 2019;19(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s40644-019-0279-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bi Z, Liu J, Chen P, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and timing of sentinel lymph node biopsy in different molecular subtypes of breast cancer with clinically negative axilla. Breast Cancer. 2019;26(3):373-377. doi: 10.1007/s12282-018-00934-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boughey JC, Ballman KV, McCall LM, et al. Tumor biology and response to chemotherapy impact breast cancer-specific survival in node-positive breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: long-term follow-up from ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance). Ann Surg. 2017;266(4):667-676. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerbelli B, Botticelli A, Pisano A, et al. Breast cancer subtypes affect the nodal response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced breast cancer: are we ready to endorse axillary conservation? Breast J. 2019;25(2):273-277. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi HJ, Ryu JM, Kim I, et al. Prediction of axillary pathologic response with breast pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;176(3):591-596. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05214-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enokido K, Watanabe C, Nakamura S, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with an initial diagnosis of cytology-proven lymph node-positive breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2016;16(4):299-304. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glaeser A, Sinn HP, Garcia-Etienne C, et al. Heterogeneous responses of axillary lymph node metastases to neoadjuvant chemotherapy are common and depend on breast cancer subtype. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(13):4381-4389. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07915-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ha R, Chang P, Karcich J, et al. Predicting post neoadjuvant axillary response using a novel convolutional neural network algorithm. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(10):3037-3043. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6613-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HS, Yoo TK, Park WC, Chae BJ. Potential benefits of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in clinically node-positive luminal subtype−breast cancer. J Breast Cancer. 2019;22(3):412-424. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2019.22.e35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JY, Park HS, Kim S, Ryu J, Park S, Kim SI. Prognostic nomogram for prediction of axillary pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cytologically proven node-positive breast cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(43):e1720. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koolen BB, Valdés Olmos RA, Wesseling J, et al. Early assessment of axillary response with 18F-FDG PET/CT during neoadjuvant chemotherapy in stage II-III breast cancer: implications for surgical management of the axilla. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(7):2227-2235. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2902-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li JW, Mo M, Yu KD, et al. ER-poor and HER2-positive: a potential subtype of breast cancer to avoid axillary dissection in node positive patients after neoadjuvant chemo-trastuzumab therapy. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e114646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S, Lee JE, Paik HJ, et al. Feasibility and prognostic effect of sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cytology-proven, node-positive breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2017;17(1):e19-e29. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2016.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park S, Park JM, Cho JH, Park HS, Kim SI, Park BW. Sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with cytologically proven node-positive breast cancer at diagnosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(9):2858-2865. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2992-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qu LT, Peters S, Cobb AN, Godellas CV, Perez CB, Vaince FT. Considerations for sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer patients with biopsy proven axillary disease prior to neoadjuvant treatment. Am J Surg. 2018;215(3):530-533. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samiei S, Van Nijnatten T, De Munck L, et al. Correlation between pathologic complete response in the breast and absence of axillary lymph node metastases after neoadjuvant systemic therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(suppl 1):S72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schipper RJ, Moossdorff M, Nelemans PJ, et al. A model to predict pathologic complete response of axillary lymph nodes to neoadjuvant chemo(immuno)therapy in patients with clinically node-positive breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14(5):315-322. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tadros AB, Yang WT, Krishnamurthy S, et al. Identification of patients with documented pathologic complete response in the breast after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for omission of axillary surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(7):665-670. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu S, Wang Y, Li J, et al. Subtype-guided 18F-FDG PET/CT in tailoring axillary surgery among node-positive breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a feasibility study. Breast. 2019;44(suppl 1):S67. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9776(19)30253-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Micco R, Zuber V, Fiacco E, et al. Sentinel node biopsy after primary systemic therapy in node positive breast cancer patients: time trend, imaging staging power and nodal downstaging according to molecular subtype. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45(6):969-975. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.01.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gentile LF, Plitas G, Zabor EC, Stempel M, Morrow M, Barrio AV. Tumor biology predicts pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients presenting with locally advanced breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(13):3896-3902. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6085-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kantor O, Sipsy LM, Yao K, James TA. A predictive model for axillary node pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(5):1304-1311. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6345-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee MK, Srour MK, Walcott-Sapp S, et al. Impact of the extent of pathologic complete response on outcomes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Published online November 27, 2019. J Surg Oncol. doi: 10.1002/jso.25787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ouldamer L, Chas M, Arbion F, et al. Risk scoring system for predicting axillary response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in initially node-positive women with breast cancer. Surg Oncol. 2018;27(2):158-165. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petruolo OA, Pilewskie M, Patil S, et al. Standard pathologic features can be used to identify a subset of estrogen receptor-positive, HER2 negative patients likely to benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(9):2556-2562. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5898-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Resende U, Cabello C, Oliveira Botelho Ramalho S, Zeferino LC. Predictors of pathological complete response in women with clinical complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast carcinoma. Oncology. 2018;95(4):229-238. doi: 10.1159/000489785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steiman J, Soran A, McAuliffe P, et al. Predictive value of axillary nodal imaging by magnetic resonance imaging based on breast cancer subtype after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Surg Res. 2016;204(1):237-241. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.04.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong SM, Weiss A, Mittendorf EA, King TA, Golshan M. Surgical management of the axilla in clinically node-positive patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a National Cancer Database analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(11):3517-3525. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07583-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boileau JF, Poirier B, Basik M, et al. Sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in biopsy-proven node-positive breast cancer: the SN FNAC study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(3):258-264. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.7827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boughey JC, Suman VJ, Mittendorf EA, et al. ; Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology . Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1455-1461. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(7):609-618. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70166-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simons JM, van Nijnatten TJA, van der Pol CC, Luiten EJT, Koppert LB, Smidt ML. Diagnostic accuracy of different surgical procedures for axillary staging after neoadjuvant systemic therapy in node-positive breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;269(3):432-442. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al-Hilli Z, Hoskin TL, Day CN, Habermann EB, Boughey JC. Impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on nodal disease and nodal surgery by tumor subtype. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(2):482-493. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6263-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simons JM, Koppert LB, Luiten EJT, et al. De-escalation of axillary surgery in breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant setting: a Dutch population-based study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;180(3):725-733. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05589-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nguyen TT, Hoskin TL, Day CN, et al. Decreasing use of axillary dissection in node-positive breast cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(9):2596-2602. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6637-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.von Minckwitz G, Huang CS, Mano MS, et al. ; KATHERINE Investigators . Trastuzumab emtansine for residual invasive HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):617-628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1814017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Masuda N, Lee SJ, Ohtani S, et al. Adjuvant capecitabine for breast cancer after preoperative chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2147-2159. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fisher ER, Wang J, Bryant J, Fisher B, Mamounas E, Wolmark N. Pathobiology of preoperative chemotherapy: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel (NSABP) protocol B-18. Cancer. 2002;95(4):681-695. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wong SM, Almana N, Choi J, et al. Prognostic significance of residual axillary nodal micrometastases and isolated tumor cells after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(11):3502-3509. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07517-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Embase Search

eMethods 2. PubMed Search

eTable. Pooled Axillary pCR Rate for Different Breast Cancer Subtypes, Divided by Patients With and Without Pathologically Proven Clinically Node-Positive Disease