Abstract

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) contains a pacemaker that generates circadian rhythms and entrains them with the 24-h light-dark cycle (LD). The SCN is composed of 16,000 to 20,000 heterogeneous neurons in bilaterally paired nuclei. γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) is the primary neurochemical signal within the SCN and plays a key role in regulating circadian function. While GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, there is now evidence that GABA can also exert excitatory effects in the adult brain. Cation chloride cotransporters determine the effects of GABA on chloride equilibrium, thereby determining whether GABA produces hyperpolarizing or depolarizing actions following activation of GABAA receptors. The activity of Na-K-2Cl cotransporter1 (NKCC1), the most prevalent chloride influx cotransporter isoform in the brain, plays a critical role in determining whether GABA has depolarizing effects. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that NKCC1 protein expression in the SCN is regulated by environmental lighting and displays daily and circadian changes in the intact circadian system of the Syrian hamster. In hamsters housed in constant light (LL), the overall NKCC1 immunoreactivity (NKCC1-ir) in the SCN was significantly greater than in hamsters housed in LD or constant darkness (DD), although NKCC1 protein levels in the SCN were not different between hamsters housed in LD and DD. In hamsters housed in LD cycles, no differences in NKCC1-ir within the SCN were observed over the 24-h cycle. NKCC1 protein in the SCN was found to vary significantly over the circadian cycle in hamsters housed in free-running conditions. Overall, NKCC1 protein was greater in the ventral SCN than in the dorsal SCN, although no significant differences were observed across lighting conditions or time of day in either subregion. These data support the hypothesis that NKCC1 protein expression can be regulated by environmental lighting and circadian mechanisms within the SCN.

Keywords: phase shifting, GABAA receptors, entrainment, circadian, chloride

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) contains a circadian pacemaker that controls the phase of daily rhythms in physiology and behavior and entrains those rhythms with the external light-dark cycle (Moore and Eichler, 1972; Stephan and Zucker, 1972; Cohen and Albers, 1991). The SCN of the anterior hypothalamus contains 16,000 to 20,000 neurons in bilaterally paired nuclei (Moore et al., 2002). The SCN is composed of anatomically distinct neuronal sub-populations with differing neuropeptide content, daily electrical activity, and clock gene expression (Antle et al., 2005; Albers et al., 2017; Carmona-Alcocer et al., 2020). In Syrian hamsters, for example, ventrolateral (“core”) SCN neurons (vSCN) receive the bulk of the input from the retinohypothalamic tract, and few neurons display rhythmic neuronal firing and clock gene expression. In contrast, dorsal (“shell”) SCN neurons (dSCN) receive much less retinal input and display robust electrical and clock gene rhythmicity (Bryant et al., 2000; Hamada et al., 2001; Jobst and Allen, 2002). Importantly, evidence also suggests the retinorecipient vSCN communicates phase information to the dSCN and ultimately adjusts the phase of these oscillators (Leak et al., 1999; Albus et al., 2005; Albers et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2017).

γ-amino butyric acid (GABA) is produced in all or nearly all neurons within the SCN, and there is substantial evidence that GABA plays a key role in regulating the phase of the circadian pacemaker (Ralph and Menaker, 1985; van den Pol and Tsujimoto, 1985; van den Pol and Gorcs, 1986; Okamura et al., 1989; Moore and Speh, 1993; O’Hara et al., 1995; Gillespie et al., 1999; Castel and Morris, 2000; Liu and Reppert, 2000; Novak and Albers, 2004; Albus et al., 2005; Albers et al., 2017). In adults, GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain; however, it is becoming increasingly clear that it can also have excitatory effects. Cation chloride cotransporters are crucial regulators of chloride equilibrium and determine if GABA is hyperpolarizing or depolarizing following activation of GABAA receptors (GABAAR; Xu et al., 1994; Gillen et al., 1996; Payne et al., 1996; Markadieu and Delpire, 2014). K-Cl cotransporters (KCCs) extrude chloride ions from the cell (stoichiometry 1K+: 1Cl−) with 4 identified isoforms (KCC1-4), thereby regulating intracellular chloride concentrations and promoting the inhibitory actions of GABA signaling. The actions of Na-K-2Cl cotransporters (NKCCs) promote the excitatory actions of GABA because these proteins transport chloride ions (stoichiometry 1Na+: 1K+: 2Cl−) into the cell. NKCC1 is the most prevalent NKCC isoform in the central nervous system. As GABA binding opens a GABAAR chloride ion pore, the likelihood of GABA leading to depolarization of a neuron is partially determined by the activity and expression level of this chloride influx cotransporter, NKCC1 (for review, see Markadieu and Delpire, 2014).

Neuronal responses to GABA in the SCN have been extensively studied, yet there is not a consensus as to its actions within the nuclei (Shibata et al., 1983; Wagner et al., 1997; Liu and Reppert, 2000; De Jeu and Pennartz, 2002; Itri et al., 2004; DeWoskin et al., 2015; Albus et al., 2005; Aton et al., 2006; Choi et al., 2008; Irwin and Allen, 2009; Myung et al., 2012; Freeman et al., 2013; Farajnia et al., 2014; Albers et al., 2017). For instance, some reports suggest GABA is exclusively inhibitory, yet others report that GABA is predominantly excitatory during the day, and still others suggest excitation to GABA is more prevalent during the night (Liou and Albers, 1990; Wagner et al., 1997; Choi et al., 2008; Irwin and Allen, 2009; Alamilla et al., 2014). To complicate matters, there is also a lack of consensus about when the dSCN and vSCN are excited and/or inhibited by GABA. Multiple studies suggest that NKCC1 is expressed in most neurons of the dSCN and vSCN, regardless of time of day or nuclear subcompartment, and excitatory responses to GABA in the adult SCN are blocked by inhibition of NKCC1 with the loop diuretic bumetanide (Choi et al., 2008; Irwin and Allen, 2009; Belenky et al., 2010; Klett and Allen, 2017). We have recently shown that endogenous excitatory responses to GABA may be a part of the mechanisms regulating phase shifts to light as well as nonphotic-like shifts of the SCN in vivo (McNeill et al., 2018).

The length of the daily photoperiod is interpreted by the circadian pacemaker as an indicator of the time of year, as long photoperiods occur in the summer and short photoperiods occur in the winter (Pittendrigh and Daan, 1976). Interestingly, cation chloride cotransporters within the SCN may respond to changes in light duration (i.e., photoperiod). Long-day exposure has been shown to increase the percentage of SCN neurons excited by GABA (Farajnia et al., 2014). In addition, GABAAR signaling may be a major regulator of SCN neuronal mechanisms of phase shifting and synchronization via both excitation and inhibition. It seems likely that changes in chloride cotransporter expression may encode both light duration and serve circadian functions such as entrainment of circadian rhythms to light. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that NKCC1 protein expression in the SCN is influenced by environmental lighting. We also tested the hypothesis that NKCC1 displays daily and circadian changes in the intact circadian system of the Syrian hamster.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, Light Treatment, and Activity Monitoring

Adult male Syrian hamsters (approximately 9–10 weeks; 120–140 g) were purchased from Charles River Labs. Upon receipt, hamsters were individually housed in polycarbonate cages with running wheels (Tecniplast) equipped with magnetic switches to record activity. Food (Lab Diet #5001, Nestle Purina Pet Care, St. Louis, MO) and water were provided ad libitum. Animal facility staff used a Kodak LED Safelight (660 nm) for routine animal husbandry. Activity was monitored as wheel revolutions/10 min and collected with VitalView Software (Mini Mitter, Bend, OR). These cage setups were placed into light-tight housing chambers and held in a 14:10 light:dark (LD) cycle for 14 days (25 ± 1 °C; 200 lux at cage tops). Housing in this way allows the animals to acclimatize to the animal facility and also standardizes the recent photoperiodic exposure of all experimental animals to diminish the aftereffects of prior entrainment. After the acclimatization period (14 days), including actogram confirmation that each hamster was entrained to the LD 14:10 cycle, the lights within the light-tight circadian chambers were either kept as LD 14:10 (LD; 200 lux) or changed to constant dark (DD) or constant light (LL; 200 lux) conditions for an additional 14 days. Housing Syrian hamsters in LD 14:10 decreases the chance of individual animals adopting a short-day phenotype. Hamsters were sacrificed at zeitgeber times (ZT) 1, 6, 13.5, and 19 for animals housed in LD and circadian times (CT) 1, 6, 13.5, and 19 for animals housed in DD or LL. Regression lines were fit to activity onsets for 7 to 10 days before sacrifice to determine the onset of activity in free-running conditions (DD and LL; ClockLab, Actimetrics, Wilmette, IL). By convention, CT 12 was defined as the time of activity onset. All procedures conformed to National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Georgia State University.

NKCC1 Protein Expression in the SCN

At the end of the 14 days in all 3 lighting conditions (LD, DD, LL), hamsters were administered a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg) and transcardially perfused with 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 150 mL, pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (150 mL, pH 7.4). Sodium pentobarbital injections were performed in dim red light (5 lux), and eyes were covered during perfusion to block the effects of acute light exposure on protein expression. The brains were removed and postfixed for an additional 20 h in 4% paraformaldehyde then moved to 20% sucrose for cryoprotection until sectioning (2–4 days). Coronal sections of brain were cut at 40 μm on a cryostat and collected in cryoprotectant (30% w/v sucrose, 1% w/v PVP-40, 30% v/v ethylene glycol in 0.9% NaCl phosphate buffer) and stored at −20°C until immunohistochemical processing.

Immunohistochemistry was yoked, such that all tissue was simultaneously processed for NKCC1 protein expression, to allow for comparison of relative protein expression within and between lighting conditions. Briefly, free-floating tissue sections were rinsed 4× in 0.1 M PBS at room temperature (RT) and then transferred to 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (80 °C, pH 8.5) for 30 min for antigen retrieval. After tissue returned to RT (30 min), sections were rinsed 3× in PBS w/0.3% v/v Triton X-100 (PBS-T) then transferred to 0.3% hydrogen peroxide to quench endogenous peroxidases (20 min at RT). Next, the sections were rinsed 3× in PBS-T, blocked in 10% v/v normal donkey serum (NDS) in PBS-T for 2 h at RT, and incubated in primary antibody targeting NKCC1 (Abcam #99558 1:500 in 0.5% NDS v/v in PBS-T [1 h at RT, 48 h at 4 °C]). Following primary antibody incubation, tissue was rinsed 4× in 5% NDS in PBS-T and then incubated in secondary antibody (1:500; Peroxidase AffiniPure Donkey anti-goat IgG [H+L], Jackson Immuno 705-035-147, West Grove, PA) in 5% NDS in PBS-T (2 h at RT). Next, sections were rinsed 3× in PBS-T and then exposed to tyramide signal amplification for 10 min (1:300, Fluorescein Plus Amplification Reagent in 1x Plus Amplification Diluent, NEL74100; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). We found this amplification step necessary to increase the intensity of the fluorescent signal (Belenky et al., 2010). After signal amplification, tissue was rinsed 3× in 0.1 M PBS then mounted onto double gelatin-coated slides (300 bloom gelatin, with chromium potassium sulfate dodecahyrdrate; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with VectaShield HardSet Anti-Fade Mounting Medium with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; H-1500, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). DAPI relative fluorescent intensity was compared across lighting regimens, times of day, and between subregions of the SCN. There were no significant differences in DAPI intensity (data not shown). Thus, all further analysis was performed only for NKCC11 relative fluorescence.

Representative SCN Tissue

Early neuroanatomical studies using rat brain tissue have describe the main neuropeptidergic subregions of the SCN as ventrolateral (core; vSCN) and dorsomedial (shell; dSCN; van den Pol and Tsujimoto, 1985). However, these divisions show differences between species, and controversy still remains about the functional significance of these neuroanatomical subdivisions (Moore et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2003; Morin and Allen, 2006; Morin, 2007; Evans, 2016; Albers et al., 2017). Further, GABAAR subunit distribution may vary on the dorsoventral and rostrocaudal axes of the nucleus (Gao et al., 1995; Belenky et al., 2003; Walton et al., 2017). Because of these differences, we chose a representative section from each animal that includes both the ventrolateral retinorecipient (calbindin-containing region of the hamster SCN) and dorsal SCN (Hamada et al., 2001). The sections correspond to the third quadrant of the rostrocaudal extent of the Syrian hamster SCN and the vasopressin-containing region dorsal and medial to these cells, as described in Hamada et al. 2001 (Silver et al., 1996; Hamada et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2003; Yan et al., 2005).

Microscopy and Quantification

All immunofluorescent images were captured at 40× for whole SCN and 100× for subregional relative quantification with a Keyence BZ-X700 (Keyence Corporation, Itasca, IL) all-in-one fluorescence microscope. DAPI immunofluorescence images were taken using a Keyence BZ-X DAPI filter (OP-87762) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 and 460 nm, respectively. Fluorescein immunofluorescence was captured with a Keyence BZ-X GFP filter (OP-87763) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 470 and 525 nm, respectively. Images were captured using the Keyence high-resolution 2.8-megapixel monochrome charge-coupled-device camera.

Image Analysis

For fluorescent analysis, ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to define a region of interest (ROI) that included an entire unilateral SCN from this level as defined by dense SCN DAPI fluorescence. An ROI was drawn using a 150-μm circle in both the vSCN and dSCN regions for subregion comparisons. Fluorescent excitation and camera exposure settings were fixed for all imaging so that direct comparisons of relative fluorescence could be made across lighting conditions and time points. Relative fluorescence was quantified using ImageJ software. Briefly, images were converted to 8-bit black and white images, and gray-scale values were measured (0–255) to quantify relative protein immunoreactivity (ir) within the ROI. An observer made measurements blind to the experimental group of each hamster.

NKCC1 Gene Expression in the SCN

Animals were handled before sacrifice for immunohistochemical experiments as described above. After 14 days in either LD or DD, hamsters were administered a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital and decapitated, and brains were quickly removed under dim red light (<5 lux) and placed in RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX). The brains remained in this solution at 4 °C until RNA extraction. Animals were sacrificed at the same time points described above (i.e., ZT 1, ZT 6, ZT 13.5, and ZT 19 for LD and CT 1, CT 6, CT 13.5, and CT 19 for DD). As reported by Walton et al. (2017), the SCN was collected by placing brains in a matrix and, using a 1.0-mm tissue punch, collected into 200 μL of Trizol (Ambion). The SCN were homogenized in 1.0 mL Trizol with a sterile pestle, and RNA extraction was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol (Ambion). RNA samples were washed 2× in chloroform and precipitated with 100% isopropanol. The resulting pellet was washed 2× with 75% ethanol and resuspended in 20 μL of water. A NanoDrop 2000 was used to determine RNA concentration. After the extraction step, 150 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with M-MLV (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. An ABI 7500 FAST real-time system was used to quantify relative gene expression along with Taqman Universal PCR master mix. The 2-step reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) cycles used were as follows: 50 °C for 12 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 sec, and 60 °C for 1 min. The primer/probe sets used were as follows: for Slc12a2, assay, ID Mm01265951_m1, Cat. #433182, and for the housekeeping gene 18s, assay ID Hs99999901_s1, Cat. #4319413E from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA), the sequences of which are proprietary (personal communication, Applied Biosystems). Prior to quantitative RT-PCR, hamster brain cDNA was amplified using each primer set, which produced a single amplicon of the predicted size for each primer set (18s, approximately 190 bp; Slc12a2, approximately 90 bp). Experimental samples were then run in duplicate, and relative gene expression was calculated using the relative standard curve method (ΔCT) using 18s as the active reference within each sample. The calibrator sample dilution (relative standard curve) for each lighting condition was generated using cDNA from pooled hippocampal RNA extracts from animals representing each time point within that lighting condition (Walton et al., 2017). Amplification efficiencies for all primer/probe sets in all PCR reactions were in the optimal range (85%−105%). Because independent calibrators were used for samples from LD and DD, no direct comparisons between LD and DD were made.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Data are represented as relative NKCC1 protein immunoreactivity (ir; gray-scale value) ±SEM. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the effect of lighting conditions and time of day on whole SCN NKCC1-ir. ANOVA was used to analyze the significant main effects of zeitgeber time or circadian time (LD, DD, and LL) on protein-ir and relative gene expression (LD and DD) followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) post hoc testing for multiple comparisons of time of day. A repeated-measures mixed ANOVA was used to determine the effects of subregion (within factor) on NKCC1-ir followed by post hoc testing. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.050.

RESULTS

Effect of lighting Conditions on NKCC1 Protein Expression in the Whole SCN

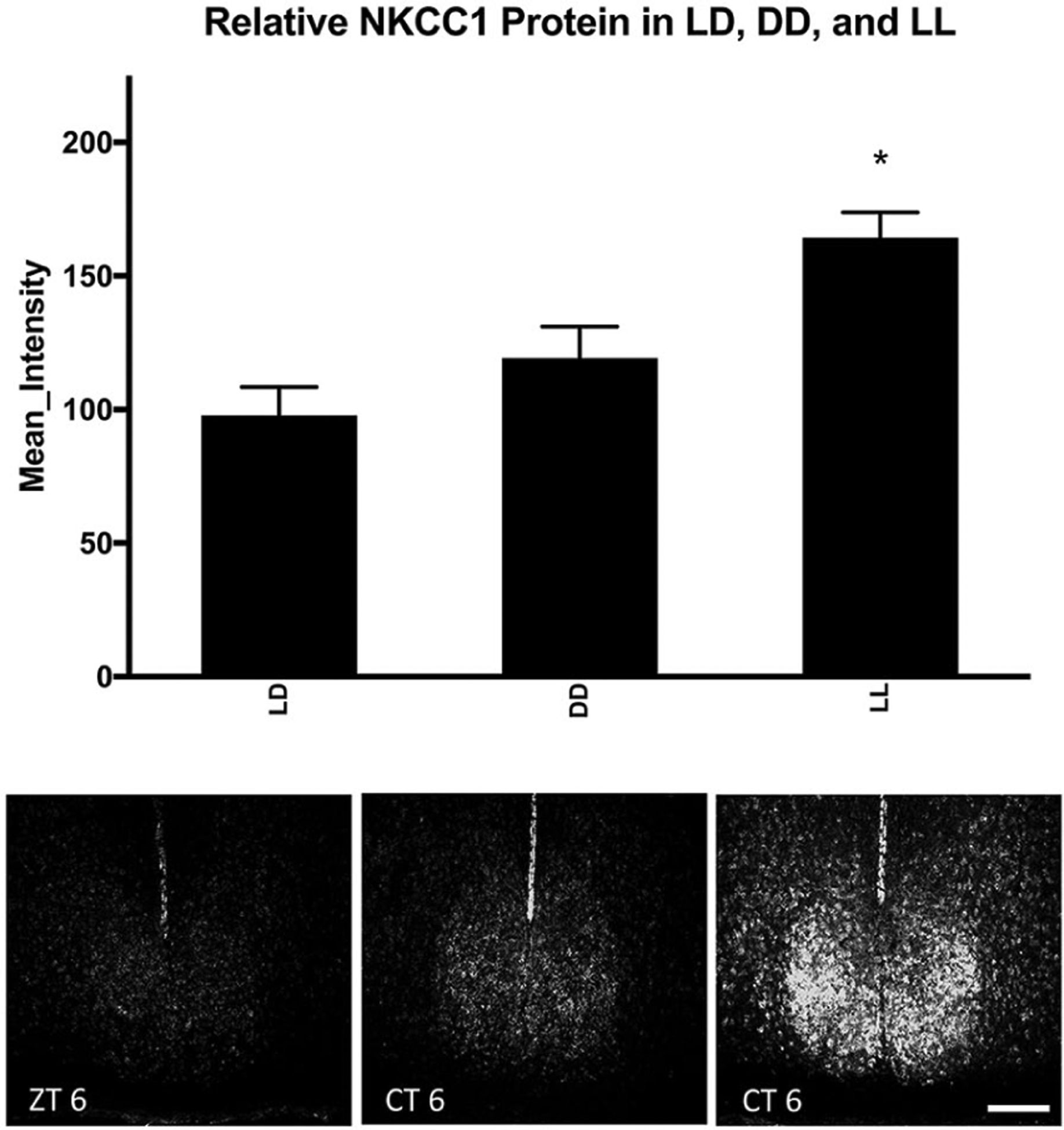

NKCC1-ir was observed throughout the SCN in hamsters housed in all conditions. As previously observed in rats, the expression of NKCC1-ir was diffuse throughout the nucleus (Belenky et al., 2010). Two-way ANOVA revealed the main effects of both lighting conditions and time of day with no interaction (F2,56 = 15.988, p = 0.000006; F3,56 = 4.553, p = 0.0073; F6,56 = 2.196, p = 0.0613, respectively). Tukey’s HSD post hoc testing revealed that hamsters housed for 14 days in LL (200 lux) had significantly higher NKCC1 protein expression in the SCN than those housed in either LD 14:10 or DD (p = 0.0001 and p = 0.001, respectively). There were no differences in overall NKCC1 protein expression in whole SCN between hamsters housed in LD or DD (p > 0.05; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of lighting condition on NKCC1 protein. lighting condition changed NKCC1 protein immunoreactivity in the SCN, as analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (F2,56 = 15.988, p = 0.000006). Means represent all hamsters within the lighting condition, regardless of the time of sacrifice (LL/DD = CT 1, 6, 13.5, and 19; LD = ZT 1, 6, 13.5, and 19). Tukey’s honestly significant difference post hoc testing revealed that LL increased protein immunoreactivity as compared with both LD and DD light cycles (p = 0.0001 and p = 0.001, respectively). *p < 0.05. Scale bar: 200 μm. Group sizes by light cycle ad zeitgeber/circadian time can be seen in Table 1.

Time-dependent NKCC1 Protein Expression in the Whole SCN (LD, DD, and LL)

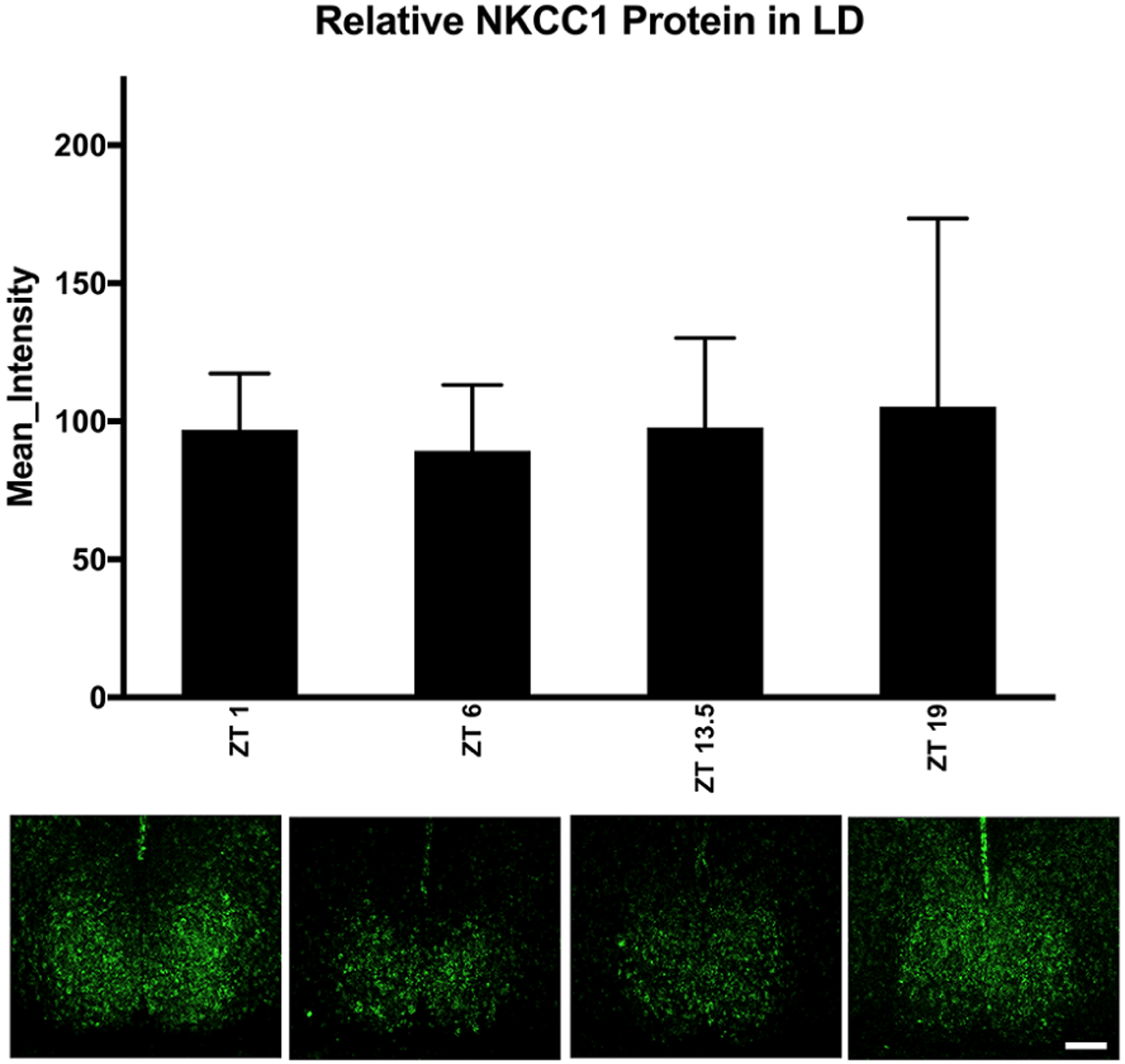

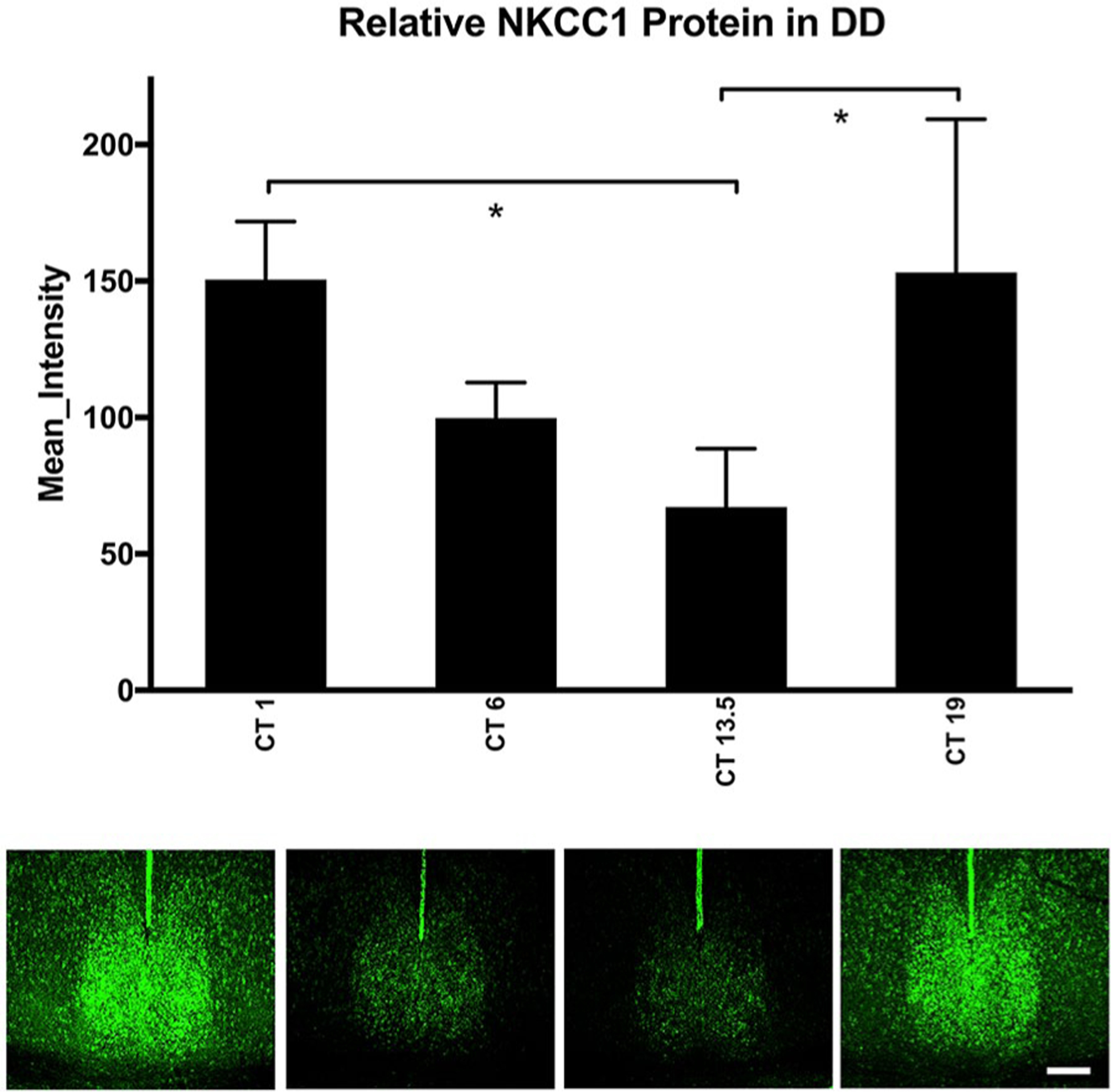

Next, because of the main effect of time of day on NKCC1 protein expression, 1-way ANOVA was used with the gray-scale value as the dependent variable and either ZT (LD) or circadian time (free-running groups in DD and LL) as independent variables, followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc testing. ZT did not affect NKCC1-ir in the SCN, suggesting no discernible time-dependent NKCC1-ir changes in hamsters housed in LD 14:10 (F3,15 = 0.075, p = 0.972; Fig. 2). In hamsters housed in DD or LL for 14 days, however, there were circadian time-dependent differences in NKCC1-ir (Figs. 3 and 4). NKCC1-ir varied in DD (F3,16 = 4.542, p = 0.017), with NKCC1 protein expression lower in the early subjective night than during the early subjective day and late subjective night (p = 0.040 and 0.033, respectively). NKCC1 protein-ir in the middle of the subjective day (CT 6) did not differ from any other circadian time point (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

NKCC1 expression in LD 14:10. When hamsters were housed in LD 14:10, one-way analysis of variance revealed that NKCC1 protein immunoreactivity in the SCN did not differ across zeitgeber time (F3,15 = 0.075, p = 0.972). Scale bar: 200 μm. Color versions are available online.

Figure 3.

NKCC1 protein expression in constant dark (DD). In hamsters housed in constant dark, one-way analysis of variance of NKCC1 protein immunoreactivity (ir) showed changes over circadian time (CT) (F3,15 = 4.542, p = 0.017). Tukey’s honestly significant difference post hoc testing revealed that NKCC1 protein in the early subjective night (CT 13.5) was lower than both early subjective day (CT 1) and late subjective night (CT 19) (p = 0.040 and 0.033, respectively). NKCC1 protein-ir in the middle of the subjective day (CT 6) did not differ from any other circadian time (CT 1, CT 13.5, CT 19; p = 0.227, 0.628, and 0.192, respectively). *p < 0.05. Scale bar: 200 μm. Color versions are available online.

Figure 4.

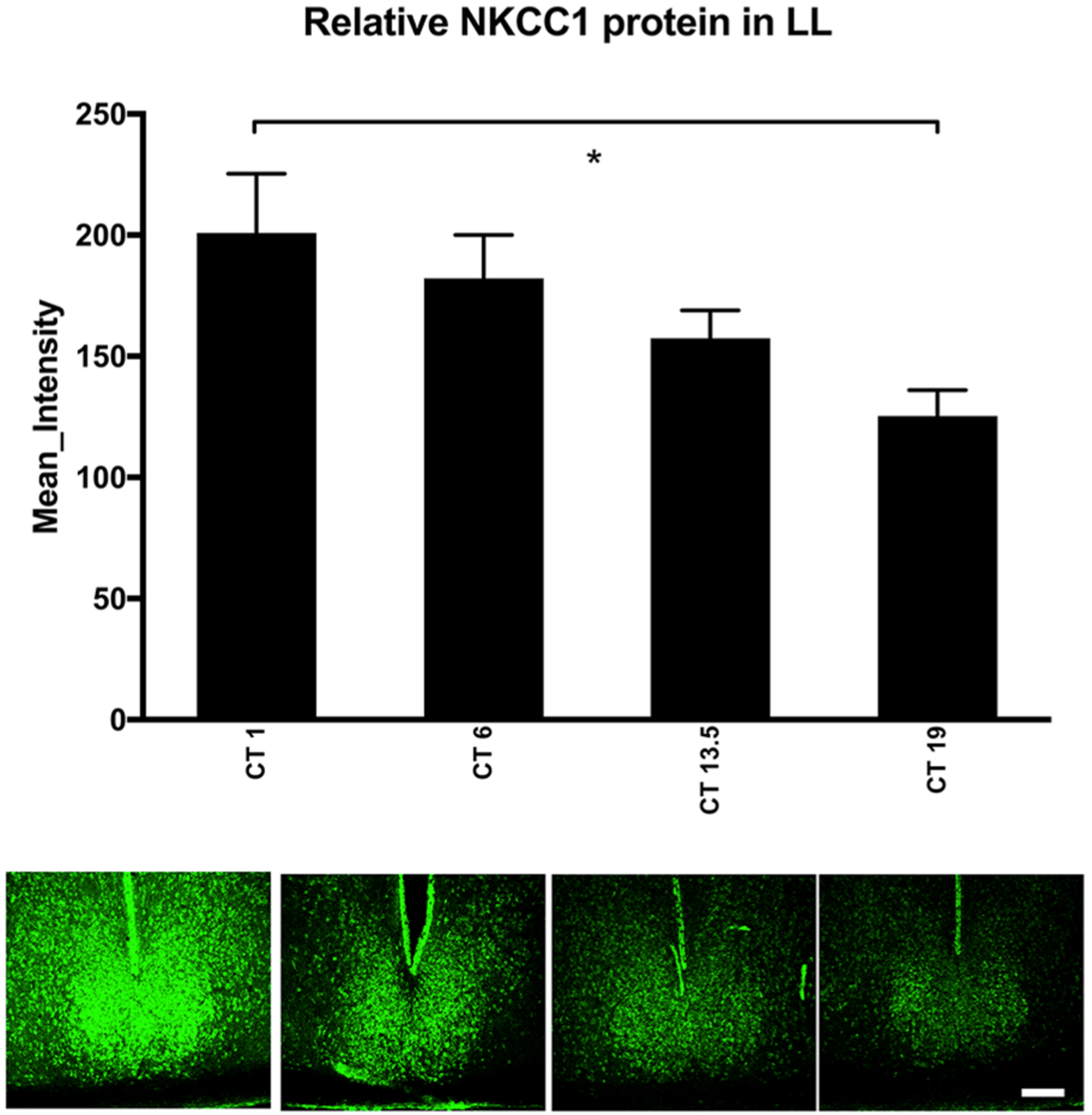

NKCC1 protein expression in constant light (LL). In hamsters housed in constant light (200 lux), a one-way analysis of variance revealed that NKCC1 protein immunoreactivity (ir) varied over circadian time, although the pattern of NKCC1 expression was different than in DD (Fig. 3; F3,16 = 3.982, p = 0.027). Tukey’s honestly significant difference post hoc testing revealed that NKCC1 protein-ir was elevated in the early subjective day (CT 1) as compared with the late subjective night (CT 19; p = 0.026). NKCC1 protein-ir in the middle of the subjective day (CT 6) and the early subjective night (CT 13.5) did not differ from other circadian times. Scale bar: 200 μm. Color versions are available online.

Hamsters housed in LL for 14 days also had circadian time-dependent differences in NKCC1-ir (F3,16 = 3.982, p = 0.027; Fig. 4). Interestingly, the pattern of NKCC1-ir was different from that of hamsters housed in DD. NKCC1-ir was at its lowest in the late subjective night (CT 19) and different from the early subjective day (CT 1; p = 0.026). NKCC1-ir in the middle of the subjective day (CT 6) and early subjective night (CT 13.5) did not differ statistically from other circadian time points (Fig. 4).

NKCC1 Protein Expression in the vSCN and dSCN (LD, DD, and LL)

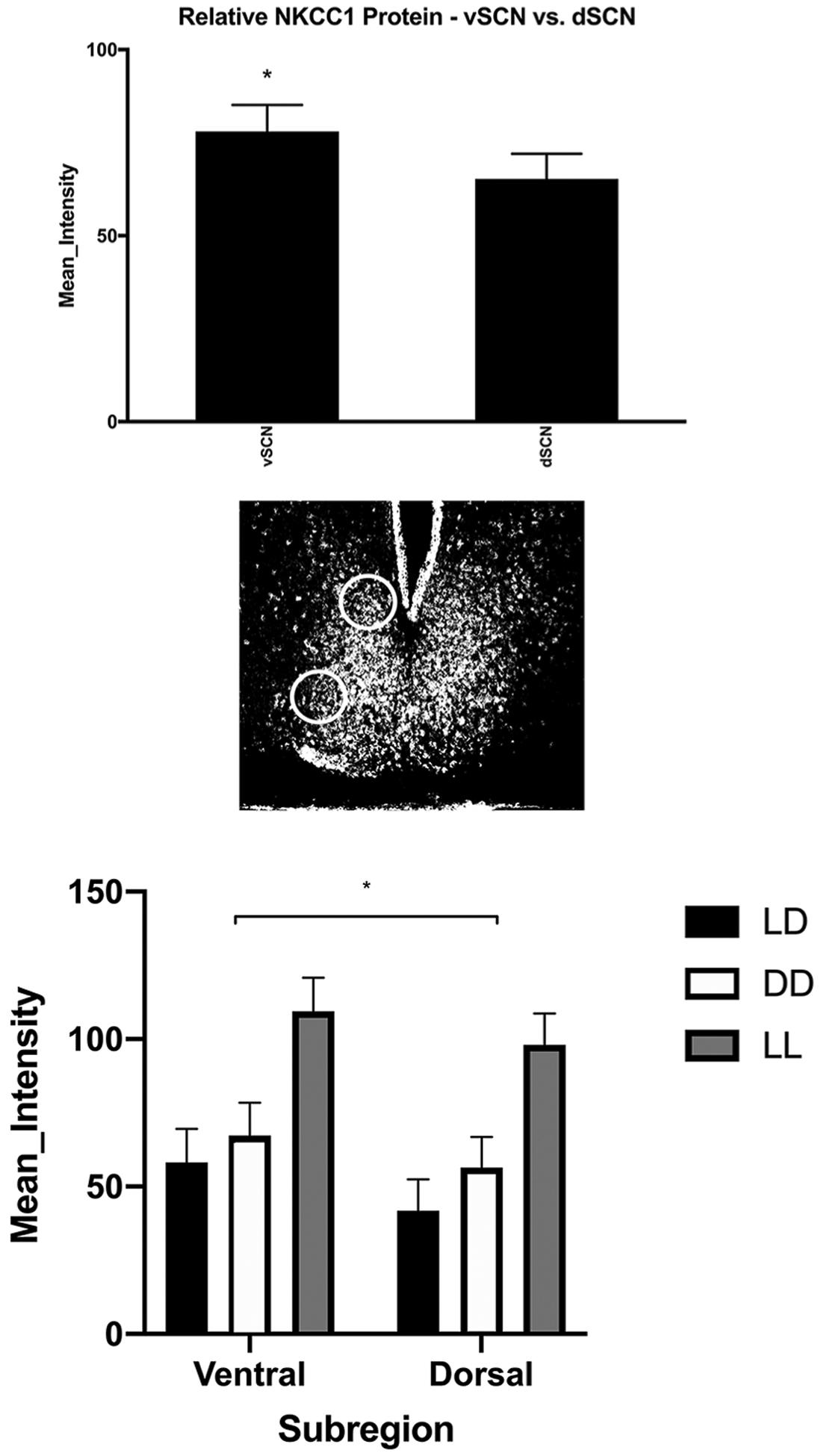

As described above, the vSCN and dSCN are well-studied subcompartments within the SCN with different neurochemical elements and different functions (Moore et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2003; Yan et al., 2007; Albers et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2017). Thus, we planned a priori to examine NKCC1-ir in these subregions using the same brain sections used for whole SCN analysis with repeated-measures mixed ANOVA across light cycles. A significant main effect of subregion on NKCC1-ir expression was uncovered (F1,55 = 14.551, p = 0.00035) without an interaction with light cycle (F2,55 = 0.272, p = 0.763; Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

NKCC1 expression in LD; vSCN and dSCN. A repeated-measures analysis of variance revealed a significant main effect in the amount of NKCC1 protein expression between SCN subregions (F1,55 = 14.551, p = 0.00035). Circles indicate the areas of the SCN where NKCC1 protein immunoreactivity was compared (diameter = 150 μm). There was no dorsal/ventral interaction within light cycle (F2,55 = 0.272, p = 0.763).

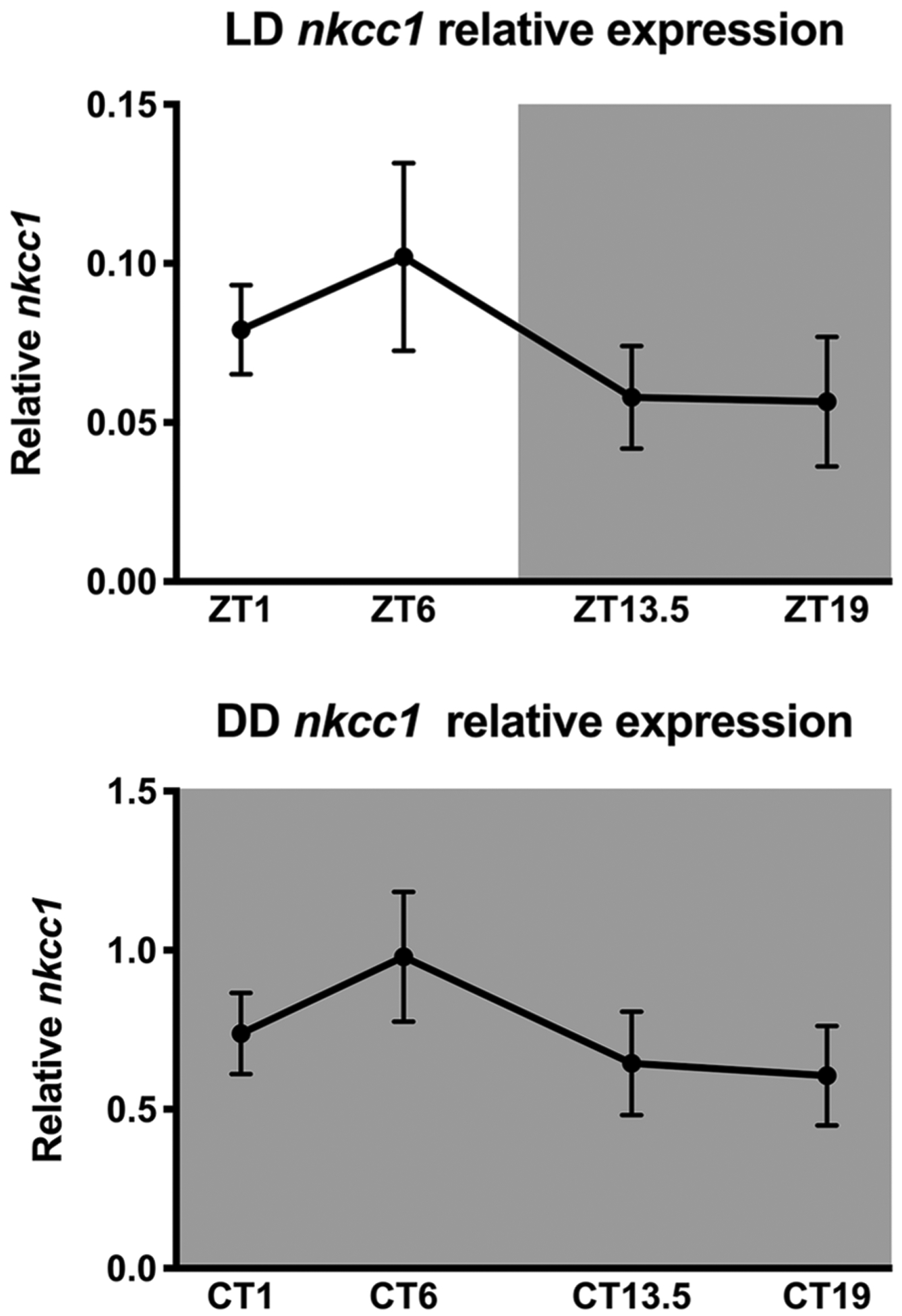

NKCC1 Gene Expression in the SCN (LD and DD)

One-way ANOVA of the relative Slc12a2 (Nkcc1) gene expression in the SCN, with time of day as the independent variable, was not significantly different across the day in either entrained (LD: F3,23 = 0.855, p = 0.478) or in free-running (DD: F3,17 = 1.035, p = 0.402) hamsters (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

NKCC1 mRNA in LD and DD. One-way analysis of variance showed that nkcc1 mRNA did not differ across the day in hamsters housed in entrained (LD: F3,23 = 0.855, p = 0.478) or in free-running conditions (DD: F3,17 = 1.035, p = 0.402).

DISCUSSION

Overall NKCC1-ir in the SCN was greater in hamsters housed in constant light than in hamsters housed in LD or DD conditions. These data suggest that light duration may increase the expression of NKCC1 protein levels in the SCN. On the other hand, NKCC1 protein levels in the SCN of hamsters housed in LD cycles containing 14 h of light per day were not different than in hamsters housed in the complete absence of light. In hamsters housed in LD cycles, no differences in NKCC1-ir within the SCN were observed over the 24-h cycle. In contrast, in hamsters housed in free-running conditions, NKCC1 protein in the SCN was found to vary significantly over the circadian cycle. In DD, NKCC1 protein peaked in the late subjective night and early subjective day, whereas NKCC1 protein was lowest in the late subjective day and early subjective night (Fig. 3). Whereas in LL, the NKCC1 protein peaked in the early subjective day but declined, culminating in the lowest expression during the late subjective night (Fig. 4). Overall, NKCC1 protein was greater in the vSCN than in the dSCN in animals housed in LD or DD, but this difference was not observed in animals housed in LL (Fig. 5). However, no significant dorsal/ventral differences were observed by ZTs or CTs (Fig. 6).

An important point for consideration is that 2 main splice variants of Slc12a2 (Nkcc1) have been identified, Nkcc1a and Nkcc1b. Most commercially available NKCC1 antibodies, including the one used in the present study, bind a C-terminal domain and target amino acids encoded by exon 21. These antibodies, therefore, do not detect the Nkcc1b splice variant encoded protein because it lacks exon 21 (Randall et al., 1997; Clayton et al., 1998; Vibat et al., 2001; Kaila et al., 2014; Morita et al., 2014; Puskarjov et al., 2014a; Puskarjov et al., 2014b). This is an important point when comparing expression levels of NKCC1 genes and/or protein reported by different laboratories.

Other investigators have addressed changes in NKCC1 protein across the day but none, to our knowledge, tracked circadian changes in free-running conditions. For example, Belenky et al. (2010) used 2 antibodies to characterize NKCC1 expression in the rat SCN: one that putatively targets both Nkcc1a and Nkcc1b encoded proteins and one that most likely targets only Nkcc1a encoded protein, as in the present study. The antibody likely targeting protein products of both Nkcc1a and Nkcc1b labeled somata and fibers, while, as in the present study, the Nkcc1a protein product-specific antibody seemed to stain mostly cell bodies. Belenky et al. (2010) also described a slightly different expression pattern in the dorsoventral axis than that seen in the present study. When using the putative Nkcc1a protein product-specific antibody, animals sacrificed in the middle of the day (ZT 5–7) appeared to have a stronger signal in the dSCN than in the vSCN, although the differences were not quantified (Belenky et al., 2010). We did not find differences in Nkcc1a protein product between the day and night in hamsters entrained to an LD cycle. When employing the antibody that most likely targets two different protein products of the splice variants, Nkcc1a and Nkcc1b, Belenky et al. (2010) found no differences in immunoreactivity between rats examined during the day and the night (ZT 5–7 and ZT 17, respectively).

Importantly, NKCC1-ir was found to be co-expressed with all major SCN neuropeptides, including vasopressin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, and gastrin-releasing peptide (Belenky et al., 2010). One of the only other reports of NKCC1 protein expression in the SCN suggested that NKCC1 expression in mice is higher in the dSCN in the night with no subregional differences in the day (Choi et al., 2008). Again, neither of these studies measured NKCC1 protein expression in free-running conditions. The antibody used by Choi et al. (2008) most likely targets Nkcc1a protein products, as in our study. The lack of consensus between these few studies could arise from differences in the species studied or in the techniques used to measure NKCC1 protein.

Seasonal rhythms in mammals are mediated by the ability of the circadian clock to measure the length of the environmental photoperiod (Pittendrigh and Daan, 1976; Pohl, 1983; Pittendrigh, 1984; Bartness and Goldman, 1989; Humlova and Illnerova, 1992; Travnickova et al., 1996; Vuillez et al., 1996; Sumova and Illnerova, 1998; vanderLeest et al., 2009). Evidence that environmental lighting can influence the ratio of excitation:inhibition produced by GABA in the SCN has led to the hypothesis that changes in this ratio may be involved in encoding seasonal changes in photoperiod length (Farajnia et al., 2014; Myung et al., 2015). Support for this hypothesis comes from in vitro studies that have examined the effects of light on the ratio of SCN neurons that are excited:inhibited by GABA. For example, a greater percentage of SCN neurons in a hypothalamic slice obtained from mice housed in long photoperiods respond to GABA with excitation than SCN neurons from mice housed in equinoctial or short photoperiod conditions. Specifically, 40% of SCN neurons from mice housed in LD 16:8 show excitatory transients in response to GABA application, whereas 32% had inhibitory responses. In mice housed in LD 8:16, this ratio switches, such that 28% of neurons are excited and 52% are inhibited, whereas mice housed in an equinoctial photoperiod display an intermediate response (Farajnia et al., 2014). In addition, in neurons obtained from mice housed in long photoperiods (16:8), the ratio of NKCC1/KCC2 mRNA and total intracellular chloride is higher than in SCN neurons from mice housed in short photoperiods (8:16; Myung et al., 2015).

The data obtained in the present study from analysis of the NKCC1 protein in intact hamsters housed in different lighting conditions do not fully support the hypothesis that the ratio of the excitation:inhibition produced by GABA in the SCN is involved in encoding seasonal changes in photoperiod length. Although the NKCC1 protein is significantly higher in the SCN of hamsters housed in LL than in hamsters housed in DD or LD 14:10, there is no significant difference in NKCC1 protein between hamsters housed in DD and LD 14:10. It is possible, however, that the duration of the photoperiod only influences the ratio of excitation:inhibition in response to GABA within the SCN in animals entrained to an LD cycle. It will be important to clearly define the relationship between photoperiod length and the ratio of excitation:inhibition produced by GABA in the SCN in animals entrained to LD cycles.

Because the circadian clock can be entrained to very short or very long photoperiods, it seems unlikely that specific ratios of GABA-induced excitation:inhibition in SCN neurons are required for entrainment to the LD cycle. The length of the photoperiod can, however, influence the magnitude of the phase-shifting effects of light. Light-induced phase advances and delays are smaller in animals previously housed in longer photoperiods (Pittendrigh et al., 1984; Evans et al., 2004; Evans, 2016). As such, it might be predicted that an increased ratio of GABA-induced excitation:inhibition in SCN neurons as a result of long photoperiod exposure would reduce the phase-shifting response of the circadian clock to incoming zeitgebers. We recently found, however, that injection of the NKCC1 inhibitor bumetanide into the SCN decreased light-induced phase delays, suggesting that the excitatory effects of GABA in the SCN contribute to the phase-delaying effects of light. These studies also found that inhibition of the excitatory effects of GABA reduced the phase-advancing effects of nonphotic stimuli during the middle of the subjective day (McNeill et al., 2018). Interestingly, no differences were observed in NKCC1-ir across the day in hamsters housed in the LD cycle, although significant differences in NKCC1-ir were found at different phases of the circadian cycle in hamsters housed in both DD and LL. Thus, while it appears that the circadian clock regulates NKCC1 protein in free-running conditions, the underlying mechanisms responsible for, and the functional significance of, the different patterns of NKCC1 protein in LL and DD are not clear. The circadian variations in NKCC1 and their absence in animals entrained to the LD cycle are interesting given that some mechanisms regulating GABA function in the SCN are rhythmic in animals housed in LD cycles but damp out in constant lighting conditions (Cagampang et al., 1996; Huhman et al., 1996; Huhman et al., 1999).

Unlike our NKCC1 protein measurements, we did not observe time-of-day–/subjective day–dependent differences in the expression of Slc12a2 (Nkcc1) in animals housed in either LD 14:10 or DD conditions. A few different mechanisms could explain this observation. For example, the number of functional chloride cotransporters is regulated by membrane trafficking, activation, deactivation by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, and proteolytic cleavage (Delpire and Gagnon, 2008; Alessi et al., 2014; Kaila et al., 2014; Piala et al., 2014). Thus, daily or circadian changes in any one of these posttranslational modifications could lead to changes in the rhythm of the NKCC1 protein that are not evident at the transcript level. Using the hamster whole-brain transcriptome, we found transcripts that most likely encode different NKCC1 protein products, but the functional significance of this finding is unknown (McCann et al., 2017). Since we used a proprietary primer/probe set of unknown sequence, we are not able to distinguish between these splice variants and our gene expression findings. It will be important for future work to look at the functional significance of these Slc12a2 (Nkcc1) splice variants in the SCN on NKCC1 expression, function, and role in time-keeping mechanisms. It is important to note, however, that mRNA rhythms generally appear to be uncoupled from protein rhythms in the SCN (for a discussion, see Olsen and Sieghart, 2008; Challet et al., 2013).

Studies of the excitatory and inhibitory effects of GABA in the SCN have not provided consistent results. Some studies of SCN neuronal activity report no differences in the effects of GABA administration at different times of day (Liou and Albers, 1990; Mason et al., 1991; Gribkoff et al., 1999; Gribkoff et al., 2003). Other studies have found GABA to be excitatory during the day in a substantial number of SCN neurons (Wagner et al., 1997; Wagner et al., 2001). Still others report that GABA is excitatory during certain parts of the night or subjective night (De Jeu and Pennartz, 2002; Choi et al., 2008). Other studies suggest that the balance between excitatory and inhibitory depends on the time of day as well as subregion of the SCN examined.

Despite the large number of studies examining GABA-induced exciation:inhibition in the SCN, a clear consensus of how GABA influences neuronal activity in the SCN has not been reached. It has been suggested, however, that the most parsimonious interpretation of the data may be that GABA produces primarily inhibitory responses during the day and remains mostly inhibitory at night in the vSCN but can have substantial excitatory effects in the dSCN (Albers et al., 2017).

CONCLUSION

The current data add to the findings that the NKCC1 protein may be regulated by environmental lighting conditions. These data also suggest that there is a circadian rhythm in NKCC1 protein in the hamster SCN. Importantly, these studies are the first to measure the NKCC1 protein in the SCN in both LD and free-running conditions. The SCN offers a dense GABAergic network with which to study GABA-induced excitation that is increasingly thought to play a role in cell-to-cell signaling within the brain.

Table 1.

Group sizes by light cycle and zeitgeber/circadian time.

| Light Cycle | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ZT/CT | LD | DD | LL |

| 1 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 6 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| 13.5 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| 19 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 19 | 20 | 20 |

ZT = zeitgeber time; CT = circadian time; LD = 14:10 light-dark cycle; DD = constant dark; LL = constant light.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Daniel Hummer and Alisa Norvelle for assistance with these experiments. We also thank Ancilla Titus-Scotland, Robert Bynes, and Christopher Barrow for animal husbandry. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01NS078220 to H.E.A. and F32NS092545 to J.C.W.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- Alamilla J, Perez-Burgos A, Quinto D, and Aguilar-Roblero R (2014) Circadian modulation of the Cl(−) equilibrium potential in the rat suprachiasmatic nuclei. Biomed Res Int 2014:424982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers HE, Walton JC, Gamble KL, McNeill JKt, and Hummer DL(2017) The dynamics of GABA signaling: revelations from the circadian pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Front Neuroendocrinol 44:35–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albus H, Vansteensel M, Michel S, Block G, and Meijer J (2005) A GABAergic mechanism is necessary for coupling dissociable ventral and dorsal regional oscillators within the circadian clock. Curr Biol 15:886–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi DR, Zhang J, Khanna A, Hochdorfer T, Shang Y, and Kahle KT (2014) The WNK-SPAK/OSR1 pathway: master regulator of cation-chloride cotransporters. Sci Signal 7:re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antle M, LeSauter J, and Silver R (2005) Neurogenesis and ontogeny of specific cell phenotypes within the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 157:8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aton S, Huettner J, Straume M, and Herzog E (2006) GABA and Gi/o differentially control circadian rhythms and synchrony in clock neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:19188–19193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartness TJ, and Goldman BD (1989) Mammalian pineal melatonin: a clock for all seasons. Experientia 45:939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky M, Sollars P, Mount D, Alper S, Yarom Y, and Pickard G (2010) Cell-type specific distribution of chloride transporters in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience 165:1519–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky MA, Sagiv N, Fritschy JM, and Yarom Y (2003) Presynaptic and postsynaptic GABAA receptors in rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroscience 118:909–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D, LeSauter J, Silver R, and Romero M (2000) Retinal innervation of calbindin-D28K cells in the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus: ultrastructural characterization. J Biol Rhythms 15:103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagampang FR, Rattray M, Powell JF, Campbell IC, and Coen CW (1996) Circadian changes of glutamate decarboxylase 65 and 67 mRNA in the rat suprachiasmatic nuclei. Neuroreport 7:1925–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona-Alcocer V, Rohr KE, Joye DAM, and Evans JA (2020) Circuit development in the master clock network of mammals. Eur J Neurosci 51:82–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel M and Morris J (2000) Morphological heterogeneity of the GABAergic network in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the brain’s circadian pacemaker. J Anat 196(pt 1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challet E, Denis I, Rochet V, Aioun J, Gourmelen S, Lacroix H, Goustard-Langelier B, Papillon C, Alessandri JM, and Lavialle M (2013) The role of PPARbeta/delta in the regulation of glutamatergic signaling in the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus. Cell Mol Life Sci 70:2003–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Lee C, Schroeder A, Kim Y, Jung S, Kim J, Kim DY, Son E, Han H, Hong S, et al. (2008) Excitatory actions of GABA in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurosci 28:5450–5459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton GH, Owens GC, Wolff JS, and Smith RL (1998) Ontogeny of cation-Cl-cotransporter expression in rat neocortex. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 109:281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA and Albers HE (1991) Disruption of human circadian and cognitive regulation following a discrete hypothalamic lesion: a case study. Neurology 41:726–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jeu M and Pennartz C (2002) Circadian modulation of GABA function in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus: excitatory effects during the night phase. J Neurophysiol 87:834–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpire E and Gagnon KB (2008) SPAK and OSR1: STE20 kinases involved in the regulation of ion homoeostasis and volume control in mammalian cells. Biochem J 409:321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWoskin D, Myung J, Belle MD, Piggins HD, Takumi T, and Forger DB (2015) Distinct roles for GABA across multiple timescales in mammalian circadian timekeeping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:E3911–3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JA (2016) Collective timekeeping among cells of the master circadian clock. J Endocrinol 230:R27–R49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JA, Elliott JA, and Gorman MR (2004) Photoperiod differentially modulates photic and nonphotic phase response curves of hamsters. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286:R539–R546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farajnia S, van Westering TL, Meijer JH, and Michel S (2014) Seasonal induction of GABAergic excitation in the central mammalian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:9627–9632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman G, Krock R, Aton S, Thaben P, and Herzog E (2013) GABA networks destabilize genetic oscillations in the circadian pacemaker. Neuron 78:799–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao B, Fritschy J, and Moore R (1995) GABAA-receptor subunit composition in the circadian timing system. Brain Res 700:142–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen CM, Brill S, Payne JA, and Forbush B III (1996) Molecular cloning and functional expression of the K-Cl cotransporter from rabbit, rat, and human: a new member of the cation-chloride cotransporter family. J Biol Chem 271:16237–16244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie C, Van Der Beek E, Mintz E, Mickley N, Jasnow A, Huhman K, and Albers H (1999) GABAergic regulation of light-induced c-Fos immunoreactivity within the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Comp Neurol 411:683–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff V, Pieschl R, and Dudek F (2003) GABA receptor-mediated inhibition of neuronal activity in rat SCN in vitro: pharmacology and influence of circadian phase. J Neurophysiol 90:1438–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff V, Pieschl R, Wisialowski T, Park W, Strecker G, de Jeu M, Pennartz C, and Dudek F (1999) A reexamination of the role of GABA in the mammalian suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Biol Rhythms 14:126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T, LeSauter J, Venuti J, and Silver R (2001) Expression of Period genes: rhythmic and nonrhythmic compartments of the suprachiasmatic nucleus pacemaker. J Neurosci 21:7742–7750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhman KL, Hennessey AC, and Albers HE (1996) Rhythms of glutamic acid decarboxylase mRNA in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Biol Rhythms 11:311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huhman KL, Jasnow AM, Sisitsky AK, and Albers HE (1999) Glutamic acid decarboxylase mRNA in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of rats housed in constant darkness. Brain Res 851:266–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humlova M and Illnerova H (1992) Resetting of the rat circadian clock after a shift in the light/dark cycle depends on the photoperiod. Neurosci Res 13:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin R and Allen C (2009) GABAergic signaling induces divergent neuronal Ca2+ responses in the suprachiasmatic nucleus network. Eur J Neurosci 30:1462–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itri J, Michel S, Waschek J, and Colwell C (2004) Circadian rhythm in inhibitory synaptic transmission in the mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurophysiol 92:311–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobst E and Allen C (2002) Calbindin neurons in the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus do not exhibit a circadian variation in spontaneous firing rate. Eur J Neurosci 16:2469–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila K, Price TJ, Payne JA, Puskarjov M, and Voipio J (2014) Cation-chloride cotransporters in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 15:637–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klett NJ and Allen CN (2017) Intracellular chloride regulation in AVP+ and VIP+ neurons of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Sci Rep 7:10226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leak RK, Card JP, and Moore RY (1999) Suprachiasmatic pacemaker organization analyzed by viral transynaptic transport. Brain Res 819:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Billings H, and Lehman M (2003) The suprachiasmatic nucleus: a clock of multiple components. J Biol Rhythms 18:435–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou S and Albers H (1990) Single unit response of neurons within the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus to GABA and low chloride perfusate during the day and night. Brain Res Bull 25:93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C and Reppert SM (2000) GABA synchronizes clock cells within the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Neuron 25:123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markadieu N and Delpire E (2014) Physiology and pathophysiology of SLC12A1/2 transporters. Pflügers Arch Eur J Physiol 466:91–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason R, Biello S, and Harrington M (1991) The effects of GABA and benzodiazepines on neurones in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of Syrian hamsters. Brain Res 552:53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann KE, Sinkiewicz DM, Norvelle A, and Huhman KL (2017) De novo assembly, annotation, and characterization of the whole brain transcriptome of male and female Syrian hamsters. Sci Rep 7:40472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill JKt, Walton JC, and Albers HE (2018) Functional significance of the excitatory effects of GABA in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Biol Rhythms 33:376–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R and Speh J (1993) GABA is the principal neurotransmitter of the circadian system. Neurosci Lett 150:112–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R, Speh J, and Leak R (2002) Suprachiasmatic nucleus organization. Cell Tissue Res 309:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY and Eichler VB (1972) Loss of a circadian adrenal corticosterone rhythm following suprachiasmatic nuclear lesions in the rat. Brain Res 42:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin L (2007) SCN organization reconsidered. J Biol Rhythms 22:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin LP and Allen CN (2006) The circadian visual system. Brain Res Rev 51:1–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y, Callicott JH, Testa LR, Mighdoll MI, Dickinson D, Chen Q, Tao R, Lipska BK, Kolachana B, Law AJ, et al. (2014) Characteristics of the cation cotransporter NKCC1 in human brain: alternate transcripts, expression in development, and potential relationships to brain function and schizophrenia. J Neurosci 34:4929–4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung J, Hong S, DeWoskin D, De Schutter E, Forger D, and Takumi T (2015) GABA-mediated repulsive coupling between circadian clock neurons in the SCN encodes seasonal time. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:E3920–E3929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung J, Hong S, Hatanaka F, Nakajima Y, De Schutter E, and Takumi T (2012) Period coding of Bmal1 oscillators in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurosci 32:8900–8918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak C and Albers H (2004) Novel phase-shifting effects of GABAA receptor activation in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of a diurnal rodent. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286:R820–R825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara B, Andretic R, Heller H, Carter D, and Kilduff T (1995) GABAA, GABAC, and NMDA receptor subunit expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus and other brain regions. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 28:239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H, Berod A, Julien JF, Geffard M, Kitahama K, Mallet J, and Bobillier P (1989) Demonstration of GABAergic cell bodies in the suprachiasmatic nucleus: in situ hybridization of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) mRNA and immunocytochemistry of GAD and GABA. Neurosci Lett 102:131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen RW and Sieghart W (2008) International Union of Pharmacology. LXX. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors: classification on the basis of subunit composition, pharmacology, and function. Update. Pharmacol Rev 60:243–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne J, Stevenson T, and Donaldson L (1996) Molecular characterization of a putative K-Cl cotransporter in rat brain; a neuronal-specific isoform. J Biol Chem 271:16245–16252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piala AT, Moon TM, Akella R, He H, Cobb MH, and Goldsmith EJ (2014) Chloride sensing by WNK1 involves inhibition of autophosphorylation. Sci Signal 7:ra41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittendrigh C and Daan S (1976) A functional analysis of circadian pacemakers in nocturnal rodents. V. Pacemaker structure: a clock for all seasons. J Comp Physiol A Neuroethol Sens Neural Behav Physiol A:333–355. [Google Scholar]

- Pittendrigh CS, Elliott J, and Takamura T (1984) The circadian component in photoperiodic induction. In: Collins RPaGM, ed. Ciba Foundation Symposium. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, Ltd,. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl H (1983) Strain differences in responses of the circadian system to light in the Syrian hamster. Experientia 39:372–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puskarjov M, Kahle KT, Ruusuvuori E, and Kaila K (2014a) Pharmacotherapeutic targeting of cation-chloride cotransporters in neonatal seizures. Epilepsia 55:806–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puskarjov M, Seja P, Heron SE, Williams TC, Ahmad F, Iona X, Oliver KL, Grinton BE, Vutskits L, Scheffer IE, et al. (2014b) A variant of KCC2 from patients with febrile seizures impairs neuronal Cl-extrusion and dendritic spine formation. EMBO Rep 15:723–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph MR and Menaker M (1985) Bicuculline blocks circadian phase delays but not advances. Brain Res 325:362–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall J, Thorne T, and Delpire E (1997) Partial cloning and characterization of Slc12a2: the gene encoding the secretory Na+−K+−2Cl− cotransporter. Am J Physiol 273:C1267–C1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata S, Liou SY, and Ueki S (1983) Effect of amino acids and monoamines on the neuronal activity of suprachiasmatic nucleus in hypothalamic slice preparations. Jpn J Pharmacol 33:1225–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver R, Romero M, Besmer H, Leak R, Nunez J, and LeSauter J (1996) Calbindin-D28K cells in the hamster SCN express light-induced Fos. Neuroreport 7:1224–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan FK and Zucker I (1972) Circadian rhythms in drinking behavior and locomotor activity of rats are eliminated by hypothalamic lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 69:1583–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumova A and Illnerova H (1998) Photic resetting of intrinsic rhythmicity of the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus under various photoperiods. Am J Physiol 274:R857–R863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SR, Wang TJ, Granados-Fuentes D, and Herzog ED (2017) Resynchronization dynamics reveal that the ventral entrains the dorsal suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Biol Rhythms 32:35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travnickova Z, Sumova A, Peters R, Schwartz WJ, and Illnerova H (1996) Photoperiod-dependent correlation between light-induced SCN c-fos expression and resetting of circadian phase. Am J Physiol 271:R825–R831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol AN and Gorcs T (1986) Synaptic relationships between neurons containing vasopressin, gastrin-releasing peptide, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, and glutamate decarboxylase immunoreactivity in the suprachiasmatic nucleus: dual ultrastructural immunocytochemistry with gold-substituted silver peroxidase. J Comp Neurol 252:507–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol AN and Tsujimoto KL (1985) Neurotransmitters of the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus: immunocytochemical analysis of 25 neuronal antigens. Neuroscience 15:1049–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanderLeest HT, Rohling JH, Michel S, and Meijer JH (2009) Phase shifting capacity of the circadian pacemaker determined by the SCN neuronal network organization. PLoS One 4:e4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibat CR, Holland MJ, Kang JJ, Putney LK, and O’Donnell ME (2001) Quantitation of Na+−K+−2Cl− cotransport splice variants in human tissues using kinetic polymerase chain reaction. Anal Biochem 298:218–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuillez P, Jacob N, Teclemariam-Mesbah R, and Pevet P (1996) In Syrian and European hamsters, the duration of sensitive phase to light of the suprachiasmatic nuclei depends on the photoperiod. Neurosci Lett 208:37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Castel M, Gainer H, and Yarom Y (1997) GABA in the mammalian suprachiasmatic nucleus and its role in diurnal rhythmicity. Nature 387:598–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Sagiv N, and Yarom Y (2001) GABA-induced current and circadian regulation of chloride in neurones of the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Physiol 537:853–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton JC, McNeill JKt, Oliver KA, and Albers HE (2017) Temporal regulation of GABAA receptor subunit expression: role in synaptic and extrasynaptic communication in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. eNeuro 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JC, Lytle C, Zhu TT, Payne JA, Benz E Jr, and Forbush B III (1994) Molecular cloning and functional expression of the bumetanide-sensitive Na-K-Cl cotransporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:2201–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Foley NC, Bobula JM, Kriegsfeld LJ, and Silver R (2005) Two antiphase oscillations occur in each suprachiasmatic nucleus of behaviorally split hamsters. J Neurosci 25:9017–9026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Karatsoreos I, Lesauter J, Welsh DK, Kay S, Foley D, and Silver R (2007) Exploring spatiotemporal organization of SCN circuits. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 72:527–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]