Abstract

Aims

Studying birth-cohort differences in depression incidence and their explanatory factors may provide insight into the aetiology of depression and could help to optimise prevention strategies to reduce the worldwide burden of depression.

Methods

Data were used from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam, a nationally representative study among community dwelling older adults in the Netherlands. Cohort differences in depression incidence over a 10-year-period (score ⩾16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale) were tested using a cohort-sequential-longitudinal-design, comparing two identically measured cohorts of non-depressed 55–64-year-olds, born 10-years apart. Baseline measurements took place in 1992/93 (early cohort, n = 794), and 2002/03 (recent cohort, n = 771). As indicated by the dynamic equilibrium model of depression, potential explanatory factors were distinguished in risk and protective factors.

Results

The incidence rates for depression in the early and recent cohort were 1.91 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.59–2.27) and 1.60 (95% CI 1.31–1.94) per 100 person-years, respectively. A 29% risk reduction in depression incidence was observed in the recent cohort (HRcohort: 0.71, 95% CI 0.54–0.92, p = 0.011), as compared with the early cohort, even though average levels of risk factors such as chronic disease and functional limitations had increased. This reduction was primarily explained by increased levels of education, mastery and labour market participation.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that favourable developments of protective factors have counterbalanced unfavourable effects of risk factors on the incidence of depression, resulting in a net reduction of depression incidence among young-old adults. However, maintaining a good physical health must be a priority to further decrease depression rates.

Key words: Depression, epidemiology, incidence, risk factors

Introduction

It needs no introduction that depression is a major contributor to the global burden of disease at all ages (Ferrari et al., 2013). Although there has been an increasing awareness in the recent decades of the need to better recognise and treat depression (Kohls et al., 2017), a majority of studies have observed an increase in depression rates among recent generations (Wittchen and Uhmann, 2010). These findings have been largely based on prevalence studies (e.g. Compton et al., 2006; Jeuring et al., 2018; Weinberger et al., 2018), while only very few have been able to investigate cohort differences in the incidence of depression (Waraich et al., 2004). Whereas prevalence rates provide information about the population burden of depression, they are the net-result of the combination of the incidence and the course of depression. For studying putative changes in the occurrence of new episodes of depression and the factors that are responsible for these trends, incidence rates are more accurate. Information on trends in incidence rates and their underlying mechanisms is essential for the design of prevention strategies to help to reduce the worldwide burden of depression.

Reasons for the lack of knowledge on cohort differences in the incidence of depression may be that the required nationwide prospective studies are scarce, expensive and time-consuming. Moreover, available studies provided evidence for both increasing and decreasing trends in incidence of depression, implying that the incidence fluctuates with time and place, and that studies should be repeated in different contexts. The Lundby study in Sweden has found a twofold increase in the incidence rate of depression when a 10-year period, 1947–1957, was compared with a subsequent 15-year period, 1957–1972 (Hagnell et al., 1982). However, a slight decrease in the incidence rate within the Lundby study had been observed in the period 1972–1997, as compared with the period 1947–1972 (Mattisson et al., 2005). The Sterling County Study in Canada has demonstrated a stable annual incidence rate of depression for the period 1952–1992 (Murphy et al., 2000). A study on data collected from general practitioners in the UK from 1996 to 2006 has demonstrated a decrease in the incidence of depression diagnoses, but an increase in the registration of depressive symptoms (Rait et al., 2009). Most of these studies lacked the ability to identify explanatory factors for the trends found in depression incidence. Studying explanatory factors may reveal underlying mechanisms of trends in depression incidence, which can subsequently be addressed in preventive policy and medicine.

A useful model to understand the aetiology and onset of depression is the dynamic equilibrium model of risk and protective factors, in which the balance of risk factors relative to protective factors determines the observed changes in incidence (Fiske et al., 2009). In a large meta-analysis on risk factors of incident depression among community dwelling older adults (aged ⩾50 years), Cole (2003) identified new medical illness, poor health status, prior depression, poor self-perceived-health, bereavement, sleep disturbance, disability and female sex as the most important risk factors (Cole and Dendukuri, 2003). These findings suggest that health-related problems may be a central realm of risk of incident depression among middle-aged and older adults. In a previous study on cohort differences in the prevalence of depression, we confirmed that an increase in health problems was associated with an increase in depression prevalence in more recent cohorts of 55–64-year-olds in comparison with previous cohorts of age-peers (Jeuring et al., 2018). Simultaneously, we found that average increases in protective factors, such as educational level, labour market participation and sense of mastery, prevented the depression prevalence rates from having increased even further. These findings emphasise the importance of incorporating protective factors in studies on the incidence of depression (Jeuring et al., 2018). From these findings, it may be assumed that the shift in depression prevalence among 55–64-year-olds is the net result of two broad underlying trends in recent generations, with opposing effects on depression: the shift towards increased levels of physical health problems (increased risk) on the one hand, and an improvement in overall socio-economic resources, such as education, access to work and mastery (increased protection) on the other. Whether these trends in risk and protective factors of depression prevalence also explain cohort differences in depression incidence has not been studied yet.

The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA) allows the identification and explanation of birth-cohort differences in the incidence of depression by using a long-term (10 years) follow-up in two identically measured nationally representative samples of 55–64-year-olds, who were non-depressed at baseline (Huisman et al., 2011; Hoogendijk et al., 2016). From a clinical point of view, 55–64-year-olds are a suitable target for prevention purposes of late-life depression. Moreover, this age group is of interest because they are young enough to have experienced changes in psychosocial and socioeconomic circumstances, and old enough to have experienced changes in health status, such as physical illness and functional limitations (Jeuring et al., 2018).

The aim of the current study is to investigate and explain cohort differences in the incidence of depression. Based on our previous finding of an increase in major depression prevalence (Jeuring et al., 2018), we expected to find a higher incidence of depression in the recent cohort compared with the early cohort and that this increase in incidence rate could be explained by higher average levels of health-related risk factors in the recent cohort, as compared with the earlier cohort.

Methods

Study sample

Data were used from the LASA, an ongoing prospective cohort-sequential study among older adults in the Netherlands. Sampling procedures have been described previously (Huisman et al., 2011; Hoogendijk et al., 2016). In short, in 1992/93 the first cohort (N = 3107, birth years 1908–1937) was recruited from the population registries of 11 municipalities in three geographic areas of the Netherlands including a random sample of 55–84-year old men and women, stratified by age and sex according to the expected 5-year mortality. The cooperation rate of the first cohort was 62%, also for the 55–64-year-olds subsample (birth years: 1928–1937). Follow-ups were conducted in 1995/96 (N = 2545), 1998/99 (N = 2076) and 2001/02 (N = 1691). Exactly 10 years after the first cohort, a new cohort (N = 1,002, birth years 1938–1947) was recruited in 2002/03 including a random sample of 55–64-year-olds selected from the same sampling frame and measured identically to the first cohort. The cooperation rate for the second cohort was 62%. In subsequent observational cycles, respondents from the second cohort were combined with those from the first cohort. Follow-ups were conducted in 2005/06 (N = 1257), 2008/09 (N = 985) and 2011/12 (N = 614). All interviews were conducted in the homes of the respondents by trained interviewers. Written informed consent was obtained from all respondents. The Ethical Review Board of the VU University Medical Center approved the study.

To test our hypothesis on cohort differences in the incidence of depression, information was used on these two cohorts, for which follow-up of 10 years was available at the time of this study. From both cohorts, respondents with a strict age limit of 55–64-years at baseline were included. Four observation cycles were used for each cohort. At the fourth observational cycle (2001–02 and 2011–12, respectively) respondents were aged 65–74. Respondents were excluded when having clinically relevant depression at baseline or lacked at least one follow-up measurement. The final sample consisted of N = 1565 respondents and a total of 12 695 person-year observations. Of these 1565 respondents, 794 respondents were from the first cohort and 771 respondents from the second cohort.

Measures

Dependent variable

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) was applied to identify respondents with clinically relevant depression at each observational cycle (Radloff, 1977). Clinically relevant depression was defined by a CES-D score ⩾16. The cut-off of 16 is previously validated in LASA, and used in previous studies on depression epidemiology. The psychometric properties of the CES-D were found to be good (Beekman et al., 1997). Incident depression was defined as onset of a new depression (CES-D ⩾ 16) during the observation period. Respondents without clinically relevant depression (CES-D < 16) were indicated as having no depression. Respondents with previous episodes of depression were not excluded due to unavailability of this information for all cohort members.

Main independent variable

A dichotomous variable denoting birth-cohort was constructed, with values for belonging to the ‘early cohort’ with baseline measurement in 1992/93, and the ‘recent cohort’ with baseline measurement in 2002/03.

Explanatory independent variables

Based on two literature reviews on risk factors of incident depression among community dwelling older adults aged 55 years or older (Cole and Dendukuri, 2003; Vink et al., 2008), putative risk and protective factors were included from biological, psychological and social domains of functioning. According to the literature and based on biological plausibility, factors were considered either as risk or protective factors.

The following risk factors were included. The number of chronic diseases was assessed by self-report on current diseases and included cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer, cerebrovascular accident, arthritis and chronic non-specific pulmonary disease (range, 0–7) (Kriegsman et al., 1996). Functional limitations were measured by self-report and dichotomised in ‘none’ v. ‘one or more’ limitations (McWhinnie, 1981). Body mass index was calculated as measured body weight (kg) divided by measured height (m2). Pain was measured with the Nottingham Pain Profile scale (range, 5–10) (Landy et al., 1991). Sleep problems were measured with a four-item self-completion questionnaire (range, 3–12) (Landy et al., 1991). Alcohol consumption was measured by the number of alcohol units consumed per day (u/d) and categorised into: abstainer (0 u/d), moderate (men, 1–3 u/d; women, 1–2 u/d) and excessive (men, ⩾4 u/d; women, ⩾3 u/d) (Netherlands Central Bureau of Statistics, 1989). Smoking was dichotomised into ‘current smoker or stopped ⩽15 years ago’ v. ‘never smoked or stopped >15 years’ (Visser et al., 1999). Physical activity was measured by the LASA Physical Activity Questionnaire, from which the total time in min per day spent on physical activity was calculated (Stel et al., 2004). Neuroticism was measured with a 25-items subscale from the 36-item Dutch Personality Questionnaire (range, 0–50) (Luteijn et al., 1975). Loneliness was assessed with the De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale (range, 0–11) (de Jong-Gierveld and Kamphuls, 1985).

The following protective factors were included. Religiousness was dichotomised in having a religion or not. Partner status was dichotomised in having a partner in or outside the household v. having no partner. Education was based on the number of years of education followed (range, 5–18). Labour market participation was assessed by self-report of having a paid job for more than 1 h per week. Physical performance was measured with three performance tests, including walking, chair stand and balance (range, 0–12, with higher scores indicating better performance) (Penninx et al., 2000). Mastery was measured with a translated and abbreviated version of the Pearlin Mastery Scale (range, 5–25) (Pearlin and Schooler, 1978). Personal network size was based on the total number of network members the respondent had regular contact with (range, 0–75); and the exchange of social support (both instrumental and emotional) was collected for nine network members whom the respondent had the most frequent contact with (range, 0–36) (Van Tilburg, 1998).

Use of antidepressants and benzodiazepines were assessed by directly recording the medication from drug containers in the home of the respondents (Sonnenberg et al., 2008). All measurement instruments were either previously validated in comparable samples in the Netherlands or in LASA pilot studies (Deeg et al., 1993). Because the dataset contained minimal 5% and maximal 25% missing values in some risk and protective factors, multiple imputation was performed, including 25 imputations and 50 iterations.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed on complete-cases data of the two cohorts pooled. The early cohort's data were weighted according to the distribution of age and sex in the recent cohort. This was done to make sure that changes in the incidence of depression, risk and protective factors reflected cohort differences and was not due to distributional differences in age and sex. χ2, t tests and Kruskal–Wallis tests were performed to examine cohort differences in risk and protective factors of depression.

Cox proportional hazard regression models the incidence or hazard rate, the number of new cases of depression per population at-risk per unit time. Respondents who developed incident depression at follow-up were labelled as ‘cases’, in which the exact date of the CES-D interview was used as survival time. Those that did not develop depression, or dropped-out (death or loss to follow-up) were all treated as ‘censored’. Further analyses performed with Cox proportional hazard regression were not weighted since all models were standard adjusted for age and sex. A basic model was created to test the association between ‘cohort’ and ‘depression’, adjusted for age and sex, to estimate the presence and degree of a cohort difference in the incidence of depression. The recent cohort was compared with the early cohort (=reference). All risk and protective factors were separately investigated for their explanatory ability. Potential explanatory factors were manually entered one by one into the basic model and the % change in hazards ratio of ‘cohort’ (HRcohort) was estimated (Table 2). The % change in (HRcohort) was calculated with following formulas: ((HRbasic model − HRmodel x)/(HRbasic model)) × 100 (Richter et al., 2012).

Table 2.

Factors associated with the decrease in the incidence of depression in the recent cohort

| Incidence of depression (CES-D ⩾ 16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRcohort | HRchange (%) | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Recent cohort (v. early), unadjusted | 0.70 | 0.54–0.92 | 0.010 | |

| Recent cohort (v. early), age and sex-adjusted | 0.71 | Reference | 0.54–0.92 | 0.011 |

| Protective factors | ||||

| Education | 0.78 | −9.9 | 0.59–1.02 | 0.069 |

| Labour market participation | 0.75 | −5.6 | 0.65–0.86 | 0.032 |

| Mastery | 0.76 | −7.0 | 0.58–0.99 | 0.049 |

| Religious | 0.71 | 0 | 0.54–0.93 | 0.011 |

| Partner | 0.71 | 0 | 0.54–0.93 | 0.013 |

| Network size | 0.72 | −1.4 | 0.67–0.88 | 0.054 |

| Exchange of social support | ||||

| Instrumental support given | 0.74 | −4.2 | 0.57–0.96 | 0.027 |

| Instrumental support received | 0.71 | 0 | 0.62–0.81 | 0.011 |

| Emotional support given | 0.74 | −4.2 | 0.56–0.97 | 0.028 |

| Emotional support received | 0.71 | 0 | 0.62–0.81 | 0.011 |

| Physical performance | 0.73 | −2.8 | 0.56–0.96 | 0.023 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Neuroticism | 0.76 | −7.0 | 0.58–0.99 | 0.046 |

| Loneliness | 0.71 | 0 | 0.62–0.81 | 0.012 |

| Sleep problems | 0.70a | +1.4 | 0.53–0.93 | 0.015 |

| Pain | 0.69a | +2.8 | 0.53–0.90 | 0.007 |

| ⩾One chronic disease | 0.67a | +5.6 | 0.51–0.88 | 0.004 |

| ⩾One functional limitation | 0.64a | +9.9 | 0.49–0.84 | 0.001 |

| Body mass index | 0.69a | +2.8 | 0.53–0.91 | 0.008 |

| Physical activity | 0.70a | +1.4 | 0.53–0.91 | 0.009 |

| Alcohol use | 0.68a | +4.2 | 0.52–0.90 | 0.007 |

| Smoking | 0.72 | −1.4 | 0.55–0.95 | 0.018 |

| Psychotropic medication | ||||

| Antidepressant use | 0.71 | 0 | 0.54–0.93 | 0.013 |

| Benzodiazepine use | 0.71 | 0 | 0.54–0.93 | 0.013 |

HR, hazard ratio; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale.

Suppressors.

Factors were considered to be potentially explanatory when the magnitude of the association of cohort with depression incidence (HRcohort) was reduced after adding them to the regression model: thus decrease in HR if HR > 1 or increase in HR if HR < 1. Explanatory factors were considered to be suppressors when the opposite was observed: the magnitude of the association (HRcohort) became stronger after adding them to the regression model: thus decrease in HR if HR < 1 or increase in HR if HR > 1. It is important to take into account suppressors in an explanatory analysis like this, because they indicate how much stronger the association (HRcohort) would have been if these suppressing factors had remained stable over time.

Finally, multivariable analyses were performed to estimate the total percentage that could be explained by adjusting the basic model subsequently for the overall influence of suppressors, the overall influence of explanatory risk factors and finally for the overall influence of explanatory protective factors (Table 3). Data analyses were conducted with SPSS v22.

Table 3.

Multivariate models explaining the decrease in depression incidence in the recent cohort

| Incidence of depression (CES-D ⩾ 16) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRcohort | HRchange (%) | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Blockwise | ||||

| Basic Model (BM) | 0.71 | Reference | 0.54–0.92 | 0.01 |

| Model II. BM + increase in protective factors | 0.93 | −31 | 0.70–1.24 | 0.62 |

| Model III. BM + decrease in risk factors | 0.77 | −9 | 0.59–1.01 | 0.06 |

| Model IV. BM + increase in risk factors (suppressors) | 0.58 | +18 | 0.43–0.79 | <0.001 |

| Stepwise | ||||

| Model V. Model IV (suppressors) | 0.58 | Reference | 0.43–0.79 | <0.001 |

| Model VI. Model V + III (explanatory risk factors) | 0.64 | −10 | 0.47–0.86 | 0.003 |

| Model VII. Model VI + II (explanatory protective factors) | 0.79 | −36 | 0.57–1.09 | 0.15 |

CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale. Variables included in models: basic model (BM) = cohort, adjusted for age and sex; model II = BM + education, mastery, labour market participation, network size, instrumental and emotional support given, physical performance; model III = BM + neuroticism and smoking; model IV = BM + functional limitations, chronic diseases, alcohol use, pain, body mass index, sleep problems, physical activity.

Results

Cohort difference in depression incidence

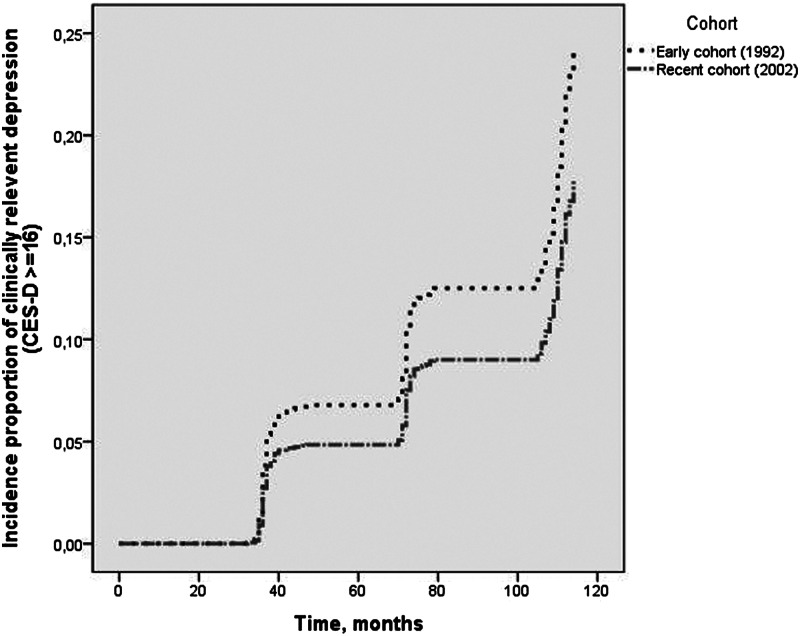

From the 794 non-depressed respondents in the early cohort at baseline, 122 (15.4%) developed incident depression at follow-up. From 771 non-depressed respondents in the recent cohort at baseline, 101 (13.1%) developed incident depression at follow-up. The total time at risk in the early cohort was 76 785 months (6399 years), whereas the total time at risk in the recent cohort was 75 559 months (6297 years). The incidence rates for the early and recent cohort were 1.91 (95% CI 1.59–2.27) and 1.60 (95% CI 1.31–1.94) per 100 person-years, respectively. The risk of developing incident depression in the recent cohort, adjusted for sex and age, was 29% less as compared with the early cohort (HR: 0.71, 95% CI 0.54–0.92), which is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Decline in depression incidence among young-old adults between 2002 and 2012 v. 1992 and 2002. The figure is an output of SPSS, delivered by a Cox proportional hazards regression, adjusted for sex and age. On the Y-axis of the figure, the cumulative incidence proportion of depression (CES-D ⩾ 16) for both cohorts is shown. On the X-axis, the survival time in months is shown (i.e. onset time to incident depression).

Cohort differences in risk and protective factors

Table 1 shows the cohort differences in risk and protective factors of depression between the early (1992/93) and recent (2002/03) cohort. The recent cohort had on average a higher level of education, more labour market participation, higher levels of mastery, of physical performance, of given instrumental and of given emotional support than the previous cohort. It also had lower average levels of neuroticism and smoking, but more chronic diseases, and functional limitations, a higher average body mass index, lower levels of physical activity and more excessive alcohol use, compared with the previous cohort. Finally, the use of antidepressants was higher in the recent cohort.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of non-depressed respondents by cohort

| Variables | Early cohort 1992/93 | Recent cohort 2002/03 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. observations, unweighted | 794 | 771 | |

| Female, no. (%) | 406 (51.1) | 385 (49.9) | 0.64 |

| Age, 55–64, mean (s.d.), years | 60.1 (2.8) | 59.9 (2.9) | 0.084 |

| No. observations, weighted | 793 | 771 | |

| Protective factors | |||

| Education, mean (s.d.), years | 9.6 (3.3) | 10.6 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Labour market participation, no. (%), yes | 251 (32.0) | 358 (46.4) | <0.001 |

| Mastery, mean (s.d.) | 18.3 (3.1) | 18.8 (3.0) | 0.003 |

| Religious, no. (%), yes | 482 (60.7) | 413 (53.6) | 0.004 |

| Partner, no. (%), yes | 678 (85.4) | 674 (87.4) | 0.24 |

| Network size, median (IQR) | 14.0 (12.0) | 14.0 (12.0) | 0.68 |

| Exchange of social support, mean (s.d.) | |||

| Instrumental support given | 16.1 (7.0) | 17.4 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| Instrumental support received | 14.5 (6.4) | 14.8 (6.3) | 0.36 |

| Emotional support given | 21.6 (7.8) | 24.2 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Emotional support received | 23.1 (7.5) | 22.6 (7.6) | 0.24 |

| Physical performance, mean (s.d.) | 8.7 (2.3) | 9.2 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Neuroticism, median (IQR) | 4.0 (6.0) | 4.0 (6.0) | 0.009 |

| Loneliness, median (IQR) | 0.0 (2.0) | 1.0 (2.0) | 0.80 |

| Sleep problems, mean (s.d.) | 5.4 (2.0) | 5.5 (2.0) | 0.66 |

| Pain, median (IQR) | 5.0 (0.0) | 5.0 (1.0) | 0.11 |

| ⩾1 Chronic diseases, no. (%) | 359 (45.3) | 396 (51.4) | 0.016 |

| ⩾1 Functional limitations, no. (%) | 117 (14.8) | 164 (21.3) | 0.001 |

| Body mass index, median (IQR) | 26.4 (4.3) | 27.0 (5.1) | 0.003 |

| Physical activity, median (IQR), min/day | 173.6 (158.7) | 143.2 (137.5) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol use | <0.001 | ||

| Abstainer | 101 (13.9) | 48 (6.6) | |

| Moderate use | 543 (74.7) | 534 (73.2) | |

| Excessive use | 83 (11.4) | 148 (20.3) | |

| Smoking, no. (%) | 366 (50.1) | 314 (43.0) | 0.006 |

| CES-D score at baseline, mean (s.d.) | 4.9 (4.1) | 5.4 (4.2) | 0.021 |

| Incident depression (CES-D ⩾ 16) at follow-up, no. (%) | 122 (15.4) | 101 (13.1) | 0.20 |

| Psychotropic medication | |||

| Antidepressant use, no. (%), yes | 5 (0.7) | 22 (3.0) | 0.001 |

| Benzodiazepine use, no. (%), yes | 42 (5.7) | 39 (5.3) | 0.74 |

No., number; s.d., standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale.

Bold values are statistically significant at p < 0.05. χ2 values have been computed for categorical variables, t-values for interval variables and independent-sample Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to determine non-parametric variables.

Explaining cohort difference in depression incidence

The contribution of each risk and protective factor to the difference in depression incidence between the cohorts is shown in Table 2. The differences in education (−9.9%), mastery (−7.0%) and neuroticism (−7.0%) contributed most to the difference in depression incidence. On the other hand, the high levels of functional limitations (+9.9%), chronic diseases (+5.6%), and excessive alcohol use (+4.2%) in the recent cohort suppressed the association of cohort with depression incidence. In other words, had these health-related factors remained constant, the incidence of depression would have decreased even further. Table 3 shows that the risk of developing depression in the recent cohort was 42% less (HR: 0.58, 95% CI: 0.43–0.79) as compared with the early cohort, after adjustment for all suppressors (model V).

The decrease in risk factors (neuroticism and smoking) explained 10% of the reduction in depression incidence (model VI), but the overall increase in protective factors (education, mastery, labour market participation, network size, instrumental and emotional support given, physical performance) explained the most part of the reduction in depression incidence (model VII). In total, 36% of the difference in depression incidence between the cohorts could be explained by all these risk and protective factors together.

Discussion

This study found a substantial cohort difference in the 10-year incidence of depression between two cohorts of 55–64-year-olds: those from the recent cohort developed incident depression less often than the earlier cohort. The difference amounted to a 29% lower incidence risk observed in the recent cohort. The difference was primarily related to favourable developments in protective and resilience related factors, including an increase in levels of education, mastery and labour market participation. Had risk factors, such as chronic diseases and functional limitations, not increased in the recent cohort compared with the earlier cohort, the incidence difference would have been even larger. Although this finding indicates that chronic diseases and functional limitations are indeed important risk factors for developing depression, their relatively high levels in the recent cohort had not resulted in an increase in depression incidence between the cohorts, thereby falsifying our initial hypothesis. In terms of the dynamic equilibrium theory of depression, we conclude that the favourable developments in protective factors have outweighed the concurrent negative effects of developments in risk factors of depression.

Our study adds new knowledge to previous work, because published epidemiological studies on trends in depression rates have mainly focused on cohort differences in the prevalence (Waraich et al., 2004), rather than incidence of depression. The majority of these prevalence studies have reported an increase in depression rates (Wittchen and Uhmann, 2010). The observed incidence rates of depression from the early (1.9 per 100 person-years) and recent cohort (1.6 per 100 person-years) are both of comparable magnitude as those in other studies (Waraich et al., 2004). However, increasing (Hagnell et al., 1982), decreasing (Eaton et al., 2007; Rait et al., 2009) and stable trends in depression incidence have all been reported (Murphy et al., 2000). Comparing these studies is extremely difficult, because different samples and study designs have been used, and findings refer to different period and social contexts. When comparing our previous trend study in depression prevalence (higher rates) (Jeuring et al., 2018), with the current trend study in depression incidence (lower rates), it may be suggested that a higher prevalence is due to an increasing chronicity of depression in more recent cohorts, which has also been suggested by Eaton and colleagues using data from the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study (Eaton et al., 2007).

To our knowledge no previous study has addressed explanatory factors of cohort differences in a systematic way by using the dynamic equilibrium theory of depression. Our study identified a combination of risk and protective factors that together explained approximately one third of the difference in depression incidence. The protective role of education and sense of mastery in preventing the onset of depression is well known (Fiske et al., 2009), however, to our knowledge the protective role of labour market participation has not yet been reported. It may be that young-old adults from the recent cohort have profited from changing societal attitudes towards being open about mental illness and seeking help, which may be related to higher average educational levels, increases in participation in gainful employment and higher experienced levels of mastery. Jorm et al. (2017) has found some evidence that improvements in treatment, particularly antidepressants, have been masked by an increased reporting of symptoms because of a greater public awareness of mental disorders or willingness to disclose (Jorm et al., 2017). This may be an explanation for the higher CES-D baseline score we found in the recent v. the early cohort.

The deteriorating health trends observed in our data are not surprising, and have previously been found in another study among older adults in the Netherlands (Van Oostrom et al., 2016). In western societies the overall prevalence of chronic diseases is increasing due to the ageing of the population and the greater longevity of people with chronic conditions (Crimmins and Beltrán-Sánchez, 2011). Also, mobility functioning has deteriorated and length of life with disease and mobility functioning loss has increased between 1998 and 2008. No major role for antidepressants was found in reducing the incidence of depression in the recent cohort at follow-up. This may be explained by the broad definition of depression used in this study (CES-D ⩾ 16), including both subthreshold and major depression. Since antidepressants are not the first-choice treatment for subthreshold depression, it could be that the potential of antidepressants in preventing a new episode of depression is underestimated in our study, when compared with studies investigating the incidence of major depression.

The most important strengths are the cohort-sequential study design in which identical methods were used to recruit and measure random samples of 55–64-year-olds in the Netherlands. We had large enough samples to be able to select those without depression at baseline, following them up for maximal 10 years testing for birth-cohort differences in the incidence of depression. The relatively rich collection of risk and protective factors has enabled systematically testing the effects of putative risk and protective explanatory factors. Because both cohorts are identically measured, using long-term follow-ups with low dropout rates, our finding is not likely the result of an artefact. The study focused on a broad, but well-defined, definition of incident depression (CES-D ⩾ 16), because it has become clear that mild depression has also a huge impact on the public health burden (Meeks et al., 2011).

A number of limitations must be acknowledged. The depression incidence may be underestimated since the occurrence of depression between three-yearly follow-up measurements could have been missed. Also, 3-year incidence rates might lead to a loss of power in Cox regression. However, this is not likely to have affected the cohort comparison, because each cohort had the same follow-up schedule. Furthermore, information on a depression history lacked for most respondents in both cohorts. Additionally, solely baseline explanatory factors were included to facilitate the interpretation of cohort differences found, which may be a less sensitive method than studying time-varying factors, as risk and protective factors can change during follow-up. About two-thirds of the decline in incidence could not be explained by factors included in this study, suggesting that other factors have been important also.

To conclude, this study has demonstrated that the depression incidence fluctuates, which is partly influenced by changing risk and protective factors of depression in the community. This also led to the identification of important targets for prevention strategies. For policy makers, the most important message is that the incidence of depression is far from a stable trait of a community, and that it can be influenced. As many of the important protective factors are essentially environmental and man-made factors, this shows that policies aiming to strengthen resilience can indeed have substantial effects on the incidence of a major mental illness, such as depression.

Future research should investigate whether the same trends can be found and explained in other age groups, and in other countries. Furthermore, also cohort differences in the natural course of depression have to be investigated, because the course together with the incidence of depression determines the prevalence, i.e. burden of disease. More detailed insight into time trends of depression will help the field to move forward in the global priority to reduce the disease burden of depression (Cuijpers et al., 2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank participants and interviewers of the LASA study.

Data

An overview of the data used in this study can be found at https://www.lasa-vu.nl/data/availability_data/availability_data.htm. Data will not be shared, unless a specific request is made.

Author ORCIDs

H.W. Jeuring 0000-0002-0131-0735.

Author contributions

H.W. Jeuring, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: All authors. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Jeuring. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Administrative, technical or material support: Hoogendijk, Deeg and Comijs. Study supervision: Comijs, Beekman, Huisman and Stek.

Financial support

The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam is financed primarily by the Netherlands Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ and Van Tilburg W (1997) Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in the Netherlands. Psychological Medicine 27, 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MG and Dendukuri N (2003) Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 160, 1147–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS and Grant BF (2006) Changes in the prevalence of major depression and comorbid substance use disorders in the United States between 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. American Journal of Psychiatry 163, 2141–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM and Beltrán-Sánchez H (2011) Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? Journals of Gerontology – Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 66, 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Beekman ATF and Reynolds CF (2012) Preventing depression: a global priority. American Medical Association JAMA – Journal of the American Medical Association 307, 1033–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeg D, Knipscheer C and van Tilburg W (1993) Autonomy and well-being in the aging population: Concepts and design of the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. In NIG Trend Studies No. 7. Bunnik, the Netherlands: Netherlands Institute of Gerontology. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong-Gierveld J and Kamphuls F (1985) The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Applied Psychological Measurement 9, 289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton WW, Kalaydjian A, Scharfstein DO, Mezuk B and Ding Y (2007) Prevalence and incidence of depressive disorder: the Baltimore ECA follow-up, 1981–2004. NIH Public Access Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 116, 182–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJL, Vos T and Whiteford HA (2013) Burden of depressive disorders by country, Sex, Age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Ed. PJ Hay. Public Library of Science PLoS Medicine 10, e1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske A, Wetherell JL and Gatz M (2009) Depression in older adults. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 5, 363–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagnell O, Lanke J, Rorsman B and Ojesjö L (1982) Are we entering an age of melancholy? Depressive illnesses in a prospective epidemiological study over 25 years: the Lundby Study, Sweden. Psychological Medicine 12, 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendijk EO, Deeg DJH, Poppelaars J, van der Horst M, Broese van Groenou MI, Comijs HC, Pasman HRW, van Schoor NM, Suanet B, Thomése F, van Tilburg TG, Visser M and Huisman M (2016) The longitudinal aging study Amsterdam: cohort update 2016 and major findings. European Journal of Epidemiology 31, 927–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman M, Poppelaars J, van der Horst M, Beekman ATF, Brug J, van Tilburg TG and Deeg DJH (2011) Cohort profile: the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. International Journal of Epidemiology 40, 868–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeuring HW, Comijs HC, Deeg DJH, Stek ML, Huisman M and Beekman ATF (2018) Secular trends in the prevalence of major and subthreshold depression among 55–64-year olds over 20 years. Psychological Medicine 48, 1824–1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Patten SB, Brugha TS and Mojtabai R (2017) Has increased provision of treatment reduced the prevalence of common mental disorders? Review of the evidence from four countries. World Psychiatry 16, 90–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohls E, Coppens E, Hug J, Wittevrongel E, Van Audenhove C, Koburger N, Arensman E, Székely A, Gusmão R and Hegerl U (2017) Public attitudes toward depression and help-seeking: impact of the OSPI-Europe depression awareness campaign in four European regions. Journal of Affective Disorders 217, 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegsman DMW, Penninx BWJH, van Eijk JTM, Boeke AJJP and Deeg DJH (1996) Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 49, 1407–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landy FJ, Rastegary H, Thayer J and Colvin C (1991) Time urgency: the construct and its measurement. The Journal of Applied Psychology 76, 644–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luteijn F, Starren J and Van Dijk H (1975) Manual Dutch Personality Questionnaire (DPQ). Swets en Zeitlinger: Lisse, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Mattisson C, Bogren M, Nettelbladt P, Munk-Jörgensen P and Bhugra D (2005) First incidence depression in the Lundby study: a comparison of the two time periods 1947–1972 and 1972–1997. Journal of Affective Disorders 87, 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWhinnie JR (1981) Disability assessment in population surveys: results of the O.E.C.D. common development effort. Revue d'epidemiologie et de Sante Publique 29, 413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks TW, Vahia IV, Lavretsky H, Kulkarni G and Jeste DV (2011) A tune in ‘a minor’ can ‘b major’: a review of epidemiology, illness course, and public health implications of subthreshold depression in older adults. Journal of Affective Disorders 129, 126–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Laird NM, Monson RR, Sobol AM and Leighton AH (2000) Incidence of depression in the Stirling County Study: historical and comparative perspectives. Psychological Medicine 30, 505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netherlands Central Bureau of Statistics (1989) Health Interview Questionnaire. Heerlen, the Netherlands: CBS. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI and Schooler C (1978) The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 19, 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BW, Deeg DJ, Van Eijk JT, Beekman AT and Guralnik JM (2000) Changes in depression and physical decline in older adults: a longitudinal perspective. Journal of Affective Disorders 61, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general. Applied Psychological Measurement 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rait G, Walters K, Griffin M, Buszewicz M, Petersen I and Nazareth I (2009) Recent trends in the incidence of recorded depression in primary care. British Journal of Psychiatry 195, 520–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M, Moor I and van Lenthe FJ (2012) Explaining socioeconomic differences in adolescent self-rated health: the contribution of material, psychosocial and behavioural factors. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 66, 691–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg CM, Deeg DJ, Comijs HC, van Tilburg W and Beekman AT (2008) Trends in antidepressant use in the older population: results from the LASA-study over a period of 10 years. Journal of Affective Disorders 111, 299–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stel VS, Smit JH, Pluijm SMF, Visser M, Deeg DJH and Lips P (2004) Comparison of the LASA Physical Activity Questionnaire with a 7-day diary and pedometer. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 57, 252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oostrom SH, Gijsen R, Stirbu I, Korevaar JC, Schellevis FG, Picavet HSJ and Hoeymans N (2016) Time trends in prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity not only due to aging: data from general practices and health surveys. Ed. A Marengoni PLoS ONE 11, e0160264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tilburg T (1998) Losing and gaining in old age: changes in personal network size and social support in a four-year longitudinal study. Journal of Gerontology 53, S313–S323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink D, Aartsen MJ and Schoevers RA (2008) Risk factors for anxiety and depression in the elderly: a review. Journal of Affective Disorders 106, 29–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M, Launer LJ, Deurenberg P and Deeg DJ (1999) Past and current smoking in relation to body fat distribution in older men and women 35. Journal of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 54, M293–M298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waraich P, Goldner EM, Somers JM and Hsu L (2004) Prevalence and incidence studies of mood disorders: a systematic review of the literature. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 49, 124–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Martinez AM, Nash D, Galea S and Goodwin RD (2018) Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychological Medicine 48, 1308–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H-U and Uhmann S (2010) The timing of depression: an epidemiological perspective. Medicographia 32, 115–124. [Google Scholar]