Abstract

Objective

To explore the experiences and lessons learnt by the study team and participants of the Workplace-based HIV self-testing among Men trial during the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda.

Design

An explorative qualitative study comprising two virtual focus group discussions (FGDs) with 12 trial team members and 32 in-depth participant interviews (N=44). Data were collected via telephone calls for in-depth interviews or Zoom for FGDs and manually analysed by inductive content analysis.

Setting

Fourteen private security companies in two Uganda districts.

Participants

Members of the clinical trial study team, and men working in private security companies who undertook workplace-based HIV testing.

Results

The key themes for participants experiences were: ‘challenges in accessing HIV treatment and care, and prevention services’, ‘misinformation’ and ‘difficulty participating in research activities’. The effects on HIV treatment and prevention resulted from; repercussions of the COVID-19 restrictions, participants fear of coinfection and negative experiences at health facilities. The difficulty in participating in research activities arose from: fear of infection with COVID-19 for the participants who tested HIV negative, transport difficulties, limited post-test psychosocial support and lack of support to initiate pre-exposure prophylaxis. The key study team reflections focused on the management of the clinical trial, effects of the local regulations and government policies and the need to adhere to ethical principles of research.

Conclusions

Findings highlight the need to organise different forms of HIV support for persons living with HIV during a pandemic. Additionally, the national research regulators and ethics committees or review boards are strongly urged to develop policies and guidelines for the continuity of research and clinical trials in the event of future shocks. Furthermore, this study calls on the appropriate government agencies to ensure public and researchers’ preparedness through continuing education and support.

Trial registration number

Clinicaltrials.gov NCT04164433; Pre-results.

Keywords: COVID-19, HIV & AIDS, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study of the experiences and lessons learnt while conducting an ongoing HIV clinical trial during the COVID-19 pandemic in Uganda.

The participants included both the clinical trial team and trial participants.

Data were collected through in-depth interviews (IDIs) and focus group discussions.

We used telephone calls and the Zoom platform.

Telephone interviews made it impossible to observe non-verbal cues during the IDIs.

Introduction

COVID-19 is a viral respiratory disease caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).1 2 By 13 April 2021, there were 136,115,434 confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide, reported to the WHO with 41,140 cases and 337 deaths in Uganda.3 Several countries introduced variations of social distancing restrictions ranging from the extreme of lockdown, to banning of social gatherings and quarantine of exposed individuals. While these measures may have helped to disrupt the spread of the virus, they also interrupted the delivery of other health services and the conduct of research activities. Global reports on the impact of COVID-19 on health systems are beginning to emerge. For example, because of the closure of borders and lock downs, antiretroviral (ARV) manufacturers in India reported concerns with international shipping of raw materials, thus causing delays and raising costs.4 Globally, there is an expected shortage of ARVs not only because of the lockdowns, but also due to a shift of financial resources.5 Consequently, HIV morbidity and mortality are expected to increase during the pandemic and post-pandemic. A model by Jewell et al6 predicts that a 6-month supply disruption of ARVs because of COVID-19 pandemic could result in over 500 000 HIV related deaths in sub-Saharan Africa and twofold increase of mother to child transmission of HIV.

One of the challenges faced by the global community is how to maintain continuity of HIV care, treatment and research programmes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerging evidence suggests that COVID-19 has disrupted HIV services with negative implications on the attainment of the 90-90-90 targets and clinical services for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA).7 In a survey conducted in February 2020 in China, 32.6% of PLWHA were at risk of antiretroviral therapy (ART) discontinuation and another 48.6% did not know where to get ARVs.8 In yet another study, Sun et al found that 22.8% of the participants, reported medication uptake was disrupted and 67.5% worried about disruption in their medication and future care.9 In the same study, some participants discontinued medication to keep their HIV status concealed.9 Field notes from Kenya document how the disease has impacted HIV testing and assisted partner-notification programmes.10 Due to fear of acquiring the COVID-19 infection, patients hesitated to attend the clinic, and many others could not afford transport to the health facilities.11

In this study, we sought to document experiences of clinical trial study participants and reflections of the study team in the Workplace-based HIV self-testing among Men (WISe-Men) trial during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ‘WISe-Men’ trial is a cluster-randomised trial assessing the effectiveness of workplace-based HIV self-testing in Uganda (Clinicaltrials.gov, ID: NCT04164433). The trial started participant enrolment on 4 February 2020. However, new participant enrolments were halted on 28 March 2020. This followed directives such as the country-wide mandatory lockdown and curfew implemented by the Ugandan government and the national research regulator, the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (UNCST).12 13

Methods

WISe-Men clinical trial

This was a two-arm cluster randomised trial (CRT) involving men employed in private security companies. The clusters were private security companies each employing more than 50 men. The trial was conducted in two Ugandan districts; Kampala and Hoima. Through randomisation, Kampala district was allocated to the intervention arm and Hoima to the control arm. The clusters in the intervention arm received HIV self-testing while those in the control arm received standard HIV testing services. Men who worked at private security companies were eligible to participate in the trial if they were (i) 18–60 years old, (ii) employed >6 months within the security industry, (iii) not tested for HIV before or attained negative test results for HIV ≥1 year prior to enrolment. The participants in each arm received either an HIV test or an HIV test kit with planned follow-up at 1 month, 3 months and 12 months to assess linkage to care or prevention services.

Study design and participants

This was an explorative qualitative substudy nested in the WISe-Men clinical trial. The data in this study were collected during follow-up calls with trial participants. In this paper, ‘study participants’ will refer to the enrolled clinical trial participants who consented to share their challenges reported in this paper.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved. Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Data collection

Data were collected from a combination of in-depth interviews (IDIs) and virtual focus group discussions (FGDs) by PAM, RN, LK, MN and two research assistants who are trained and have experience in qualitative methodologies.

In-depth participant interviews

Two research team members experienced in qualitative research conducted the IDIs. Participants were purposefully sampled to include men from different employee ranks, age categories (18–25, 36–35, 36–45 and 46–64) and HIV status (positive and negative). The interview guide was tested and developed iteratively at three pilot interviews to refine the questions (see online supplemental file 1). The participants in the pilot interviews gave consent prior to participation in the study. The interview guide collected data about participants’ experiences, challenges and lessons learnt while participating in all the trial activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Phone interviews were conducted in August and September 2020 and each lasted 45 min to an hour.

bmjopen-2021-048825supp001.pdf (34.9KB, pdf)

Research team reflections

Reflections from the research team were collected during the daily de-brief meetings. The reflections were collected in two ways; face-to-face IDIs between 15 March and 30 March 2020, and virtual FGDs between 1 June and 11 June 2020 using the Zoom platform. The FGDs had six team members per group. All the team members were informed that these reflections were part of the study, and informed consent was sought. The meetings lasted 45 min to 1 hour, led by a moderator and note-taker. Both the FGD and IDI used an open guide with the question ‘What were today’s experiences, successes, challenges and lessons learned from conducting the WISe-Men trial during the COVID-19 pandemic?’. This question was incorporated into the clinical trial following ethics approval to modify the design during the unanticipated COVID-19 pandemic.

Data analysis

The phone interview recordings were transcribed verbatim. The minutes from each de-brief meeting were typed up after each meeting and archived. Both the participant and study team data were analysed manually using inductive content analysis. This process entailed open coding, developing emergent categories and conceptualisation.14 Two groups (PAM/RN and FEK/JN) reviewed the transcripts independently. The pairs identified codes separately and then discussed them to achieve consensus. Any disagreements on the codes were settled by discussion with other members of the study team (TDN/EMN/CPO). The coders iteratively named and re-named the codes as more insights and latent meanings emerged from the data. The codes were then grouped into categories and subcategories.

The research team members who took part in the de-brief meetings did not analyse the data.

To ensure trustworthiness and credibility of the data, a sample of the study participants reviewed the categories and subcategories. The sample (n=7) included one participant from each of the different employee ranks, different age groups, different HIV status and two members from the research team. The reviewers read through the identified categories and subcategories to validate them as a true representation of their perspectives of participating in an ongoing clinical trial during a pandemic. The participants corroborated most of the identified categories and subcategories, except one category ‘wrong information’ which was changed to ‘misinformation’. Interview notes were recorded in the principal researcher’s reflective journal for confirmability.

Results

Participant’s characteristics

In total we interviewed 44 participants, the majority of the clinical trial participants were 18–25 years old, and mostly security guards. The trial participants in this study (n=32) had all received HIV testing services as part of the clinical trial and 10 (31.2%) were newly diagnosed as HIV positive (see table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of participants

| Participant characteristics (N=44) | Frequency (n) | Percentage |

| Age range, years | ||

| 18–25 | 19 | 43.2 |

| 26–35 | 10 | 22.7 |

| 36–45 | 11 | 25.0 |

| 46–64 | 4 | 9.1 |

| Employment position/job title | ||

| Security guard | 20 | 45.5 |

| Field supervisor/administrator | 7 | 15.9 |

| Employers/company executives | 5 | 11.4 |

| Clinical trial team member | 12 | 27.3 |

| Trial participants HIV status (n=32) | ||

| HIV positive | 10 | 31.2 |

| HIV negative | 22 | 68.8 |

Participants’ challenges

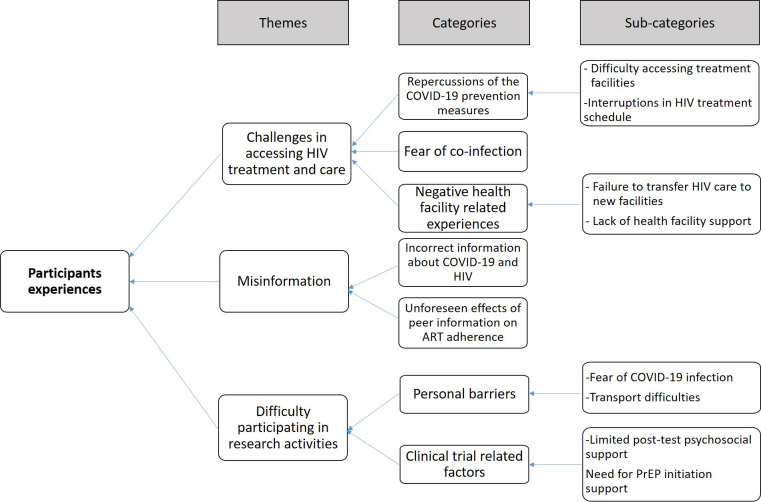

Three themes emerged from the participants’ experiences. The themes, categories and subcategories are presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Coding tree for the participants experiences of participating in an ongoing HIV clinical trial during a pandemic. *(PrEP Pre-exposure prophylaxis)

Challenges in accessing HIV treatment and care, or prevention services

Participants reported challenges in seeking and accessing HIV treatment and care or prevention services. The narrative quotes are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Narrative quotes of participants’ experiences in being part of an ongoing HIV trial during a pandemic

| Subcategory | Narrative quotes |

| Difficulty accessing treatment facilities | I got my results on March 2, 2020 and started taking HIV medication and was told to return for follow-up on April 6, 2020. I selected that hospital because it is close to my workplace but since we are not working now, I am at home and it is too far from the hospital. I have therefore decided to wait until we are released from this lockdown, to go for the medication. (Participant 29, district 2) |

| Interruptions in HIV treatment schedule | I haven’t yet told my wife my HIV status because I wasn’t expecting to be tested positive. I have been keeping the ARVs at the office and taking them each morning as soon as I report to work. When companies were closed after the president’s speech, I was one of those who was sent on temporary and indefinite unpaid leave. I am now at home and have no way of explaining why I am taking this daily medication. I just threw the tablets away and when I resume my work, I will start afresh. (Participant 01, district 1) |

| Fear of coinfection with COVID-19 | People have been saying that men and people who have other illnesses are more likely to get infected with COVID-19. Now that I am HIV positive, am I not more likely to get infected? Is HIV considered a pre-existing condition? Are people taking anti-retroviral treatment (ART) more at risk or is it better to continue the treatment? (Participant 05, district 2) |

| Incorrect information about COVID-19 and HIV | Some of our colleagues told us that people who were on ART would get COVID-19 much faster than those who were HIV positive but not on ART. That all one needs to do is eat plenty of fruits and vegetables during this time. When this happened, I stopped taking the medicine for one week. With this lockdown, we are mostly getting information from our friends, it is very unfortunate that many of us stopped taking medicine based on fake information. (Participant 07, district 1) My friends told me that only people who have underlying conditions like Diabetes [Diabetes Mellitus], pressure [Hypertension] or HIV can get COVID-19. During the wellness day, I tested, and all my results were negative. That means, I am safe. So why do I need to keep wearing a mask or social distancing or using hand sanitizer? (Participant 04, district 2) |

| Unforeseen effects of peer information on ART adherence | About a month ago, I was talking to some friends and they told me that there was a new drug for COVID-19. Apparently, this anti-viral drug is like the drugs we take for HIV. Although I did not tell them that I have HIV, I decided to take my drugs faithfully. I hope that this will lower my chance of getting the disease. (Participant 07, district 1) |

| Difficulty in transferring HIV care to new facilities | The lockdown from the government came so suddenly and we rushed to the village. I visited the health centre near my home for condoms and to refill my medicine [ART] for the next month, I was surprised to learn that I cannot just get medication from any hospital. They told me to go back to the place where I usually get my medication. I am now trying to get in touch with the former hospital to see if they can inform this health centre to allow me to pick some drugs. (Participant 16, district 2) |

| Limited HIV treatment support at health facilities | I keep forgetting to take the tablets because I am not used to taking medicine every day. I have also been struggling with some pain in my stomach since I started taking the medications. There are also some changes in my skin, I developed some swellings on my arms, and I needed to show them to my counsellor, but I cannot access the hospital. She asked me to take some pictures and send them to her on the phone, but I do not have a smartphone. I can’t cope with this anymore, I need support. (Participant 20, district 1) |

| Need for PrEP initiation support | My results were negative, but we discussed with the counsellor about starting treatment because of some reasons [PrEP]. I went to the hospital and I received the HIV drugs, but I have not yet started taking them. People told me that there are many side effects, and I do not want to have problems when I am on my own at home. I think I will wait to start treatment until I can easily see the counsellor or the doctor when they open public transport again. (Participant 05, district 1) |

| Transport difficulties | I was told to return for my follow-up visit on March 28, unfortunately by then we were in a lockdown so I couldn’t go to the facility because of the stay-at-home order. About a week later, I was not feeling well and decided to go to the facility to see the counsellor. I started walking from my house at 7:00am and finally got to the hospital at about 11am. After seeing the doctor, it was 2pm and I could not get transport back home. Unfortunately, if I decided to walk, I would have reached home past curfew hours. I therefore decided to stay at the hospital for the night with no beddings since I had not prepared for an overnight visit. The next morning, I walked home again and by the time I got home, I was feeling unwell again and sore all over. After that experience, there was no way I could go to the hospital again. (Participant 1, district 2) Honestly, it is such a hustle to come all the way to the hospital, I think I can give you all the information over the phone. I told you that my self-test was negative, therefore there is no need to come in person. The line at the Resident District Commissioner’s office for a travel permit is so long. It is not worth it. (Participant 20, district 1) |

| Fear of infection with COVID-19 | I am sorry that I did not come for the follow up visit, but I am worried about the danger of leaving my house. My family and I have been at home the entire month and my wife said that if I come back home then I need to self-isolate for 14 days. If I take that risk and come, then you must provide a substantial allowance for putting myself and my family at risk. I also figured that since I am HIV negative, there is really no need for me to come for any further check-up. (Participant 20, district 1) |

| Limited post-test psychosocial support | Just a few weeks ago, I took a test, and I was told that I am HIV positive. I still cannot believe it. The counsellor told me that I need to start on treatment [ART] immediately but I still do not believe it. I had started talking with the counsellor who asked us to come back after one month and I have started accepting my fate. However, now that I cannot see her, I feel like I have gone back to a bad state, like how I was when I had just received my results. She calls me regularly, but the network is so poor, and it is impossible to talk about so many things because we stay in a small place with many people now that we are all in the lock-down. I am waiting for this to end then I go back to the hospital for further confirmation. I hope the person who did the first test made a mistake. (Participant 15, district 2) |

*PrEP Pre-exposure prophylaxis

Difficulty accessing treatment facilities

Several participants who had recently started on ART were unable to continue with their treatment due to difficulty in accessing the health facility following the stay-at-home directives among other reasons. During the COVID-19 lockdown and curfew period in Uganda, only essential personnel who had special car stickers or travel in vehicles with special government permission were permitted to drive personal cars. Additionally, during this time, many worksites were closed. The study participants had previously selected health facilities that were close to their workplaces for their HIV care. They expressed difficulty in walking to and from their homes to the health facility to access their treatment.

Interruptions in HIV treatment schedule

A few participants experienced interruptions in their treatment schedule due to issues of non-disclosure of their HIV status and inability to explain the daily medication to their partner. They reported that they typically keep their medications at the workplace where they can easily take them without intrusive questioning from family members.

Fear of coinfection with COVID-19

Study participants who tested positive for HIV expressed concern about being more at risk of COVID-19 infection because it was widely circulated that men, older people and those with pre-existing comorbidities were more susceptible to infection.

Difficulty in transferring HIV care to new facilities

During the lockdown period, some participants travelled to their home villages to stay with their families. While they were there, they visited nearby hospitals for drug refills, however, some were denied the opportunity to transfer their care to new ART treatment facilities.

Limited HIV treatment support at health facilities

Some of the participants experienced some side effects following ART initiation. One suffered from severe stomach upsets and skin changes which he attributed to the ART treatment. Unfortunately, he was not able to access the hospital where he was receiving HIV care. He felt unsupported and still reports difficulty coping with the new treatment.

Need for PrEP initiation support

One of the participants who was undergoing counselling to commence PrEP, reported that he lacked the confidence to start without face-to-face support.

Mitigation measures for trial participants challenges in accessing HIV treatment, care or prevention services

As a result of the challenges experienced by study participants, the trial team implemented some mitigation measures to ensure that the participants received their treatment or had access to prevention services.

Home delivery of ART by study counsellors for participants who needed refills, these visits were also useful for follow-up assessments, and counselling for study participants and their partners.

Delivery of ART to community pick-up points for participants who were not willing to receive the study team members in their homes.

Follow-up phone calls from the study counsellors and nurses for participants who returned reactive HIV self-test kits and needed further counselling for ART initiation. During these counselling sessions, further information was provided regarding COVID-19.

Home and community delivery of condoms for all study participants.

Active linkage of participants to clinics for further counselling and initiation of PrEP.

Provision of letters and health information to health facilities that enabled the participants to link to HIV care and treatment at new facilities.

Misinformation

At the start of the pandemic, there was a lot of information shared via several social media platforms. Participants reported that this information influenced their decisions regarding HIV treatment. The narrative quotes are presented in table 2.

Incorrect information about COVID-19

Some participants reported that they received wrong information from their peers. For example, some participants were informed that PLWHA who were on ART were more likely to get infected with COVID-19. Therefore, some participants stopped taking their medication. Other participants who tested HIV negative were initially unwilling to follow the COVID-19 guidelines. They reported that their peers informed them that only people with underlying disease conditions were at risk for infection with the COVID-19. The WISe-Men trial had also involved blood pressure, blood glucose and syphilis tests. Therefore, some of the participants who tested negative for all the tests, were misinformed regarding their ability to contact COVID-19.

Unforeseen effects of peer information on ART adherence

A few participants heard about remdesivir as a potential drug for use in treatment of COVID-19. Their colleagues suggested that it was like the HIV ARV medication. This erroneously encouraged adherence to their ART regimen as they thought it would lower their risk of COVID-19 infection.

Difficulty participating in research activities

The other main experience involved the participants’ difficulty in taking part in follow-up research activities as part of the clinical trial. The narrative quotes are presented in table 2.

Transport difficulties

Following enrolment into the trial, all participants were meant to return for follow-op visits after 1 week, 1 month and then at 3 months. This was for participants who tested HIV positive and HIV negative. Unfortunately, the stay-at-home orders made this impossible and those who tested HIV negative were unwilling to spend their money and face the inconvenience to travel to the research sites. The research team then changed to follow-up phone calls; however, some participants had poor telephone network connectivity and therefore missed these calls.

Fear of exposure to COVID-19

Participants were concerned about the likelihood of exposure to the COVID-19 at the research site. They requested for a significant risk allowance for in-person visits during the pandemic. This was expressed more among participants who returned negative test results. They felt that there was no need to put themselves in danger of exposure to COVID-19 since they had already tested HIV negative.

Limited post-test psychosocial support

Some participants tested HIV positive for the first time and were still in denial. They reported the unmet need of support with adherence, coping with taking ART, dealing with side effects and assisted partner notification.

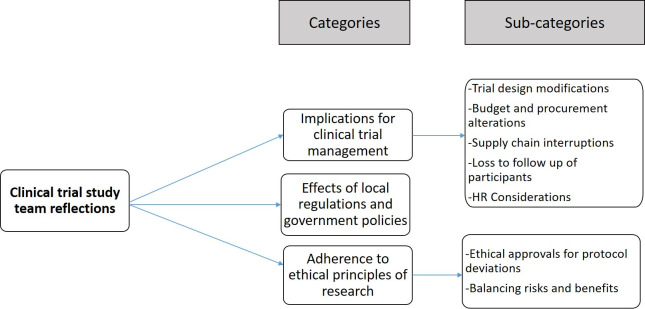

Study team reflections of managing a clinical trial during the COVID-19 pandemic

The study team reflected on their experiences of conducting an ongoing clinical trial during the COVID-19 pandemic. The coding tree is in figure 2 and the categories and narrative quotes are presented in table 3.

Figure 2.

Coding tree for the clinical trial study team of managing an ongoing HIV clinical trial during a pandemic.

Table 3.

Narrative quotes of the study team reflections on conducting a clinical trial during a pandemic

| Category | Narrative quotes |

| Trial design modifications | During this time, several participants travelled back to their villages and homes, which may have reduced the ability to control for ‘contamination’ among the individuals and this could affect our study outcomes. Additionally, the original plan was for in-person follow up visits, but the travel restrictions made this almost impossible. According to the protocol, participants were supposed to receive group pre-test HIV counselling, however, was modified to individual counselling to accommodate the social distancing directives. (Study team member, 01) |

| Budget and procurement alterations | For example, we had to procure personal protective equipment (PPE) like masks, aprons and gloves, and educational materials for the prevention of COVID-19. We also procured hand-held infrared temperature monitors, hand sanitizers, and installed handwashing stations for use at each entry point. (Study team member, 07) … public transport, we increased the budgeted transport refund from 10,000 Uganda Shillings (USD 2.65) to 76,000 (USD 20) per participant to cater for private transportation. (Study team member, 11) |

| Supply chain disruptions | Predictably, some of the companies supplying materials for the trial closed and the few that were open were overwhelmed with numbers and resorted to rationing of supplies like PPE. We experienced disruptions in obtaining vital materials like HIVST test kits and were thus were unable to continue with crucial elements of our research. (Study team member, 01) |

| Human resource considerations | … they hired two (2) new COVID-19 personnel responsible for sanitation, screening and for ensuring adherence to recommended infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines. The new staff hired also trained the rest of us and helped to respond to any queries from the participants regarding COVID-19 as it continually evolved. (Study team member, 08) The principal investigator made it clear that continuation of field-work was voluntary, and many people opted to work from home. This staffing reduction drastically slowed the trial processes because those of us who stayed had to handle more than one role. (Study team member, 06) |

| Effects of local regulations | … the Principal investigator (PI) in consultation with the oversight committee and research team, halted the recruitment of new participants into the study. We also revised and prioritized trial outcome measures to collect at each follow-up visit and the participants who were already enrolled were followed up via phone. (Study team member, 02) |

| Loss to follow-up of enrolled participants | Some of the men lost their jobs during this time and according to the trial eligibility criteria, had to be removed from the study. Others travelled upcountry to rural areas and their phones were unreachable due to the telecom network challenges. Others simply refused to take my calls or just kept ‘rejecting’ the call. This made participant follow-up difficult. (Study team member, 03) |

| Ethical approvals for protocol deviations | The trial involved the collection of biological specimens (blood), therefore, each participant was required to don a face mask and wash their hands prior to involvement in any research activities. This was eventually halted as venepuncture invalidated the social distancing guidelines. (Study team member, 11) Initially, the men were supposed to return for follow-up after 1 and 3 months. However, for those who were already recruited, their follow up visits were right in the middle of the lockdown. We therefore submitted a request for an amendment to the ethics committee to allow us to conduct the follow up visits by phone. Some of the participants were not happy about this because they wanted to discuss some things when they were assured of privacy. (Study team member, 09) |

| Balancing risks and benefits | We considered the aims of the study vs the potential for exposure to COVID-19 for everyone involved, the potential for community transmission in the study districts and the staffing strain. We eventually temporarily halted the trial. However, before the temporary closure of the trial, we informed all the study participants and sought informed consent to conduct follow-up via phone calls. We also assigned study counsellors to individual study participants, to offer psychological support and for immediate contact in the event of any adverse events. (Study team member, 02) |

Effects of local regulations and government policies

On 25 March 2020, the government of Uganda suspended public transport and placed restrictions on private vehicle movements, while on 30 March, the president declared a nationwide lockdown and curfew.12 On 27 March the UNCST banned the recruitment of new study participants. Researchers were also directed to halt face-to-face follow-up visits of the already recruited participants indefinitely.13 This had ripple effects on both the management and continuity of the clinical trial.

Clinical trial management

Trial design modifications

This was a cluster randomised design where two districts were randomly assigned to receive the intervention which was HIV self-testing and the standard HIV testing services to the control arm. During this time, several trial participants travelled back to their home villages or ancestral homes. The study team expressed concern that this may have unintentionally caused ‘contamination’ among the individuals, since participants in both the control and intervention clusters could have interacted in the villages. Evidence is still being sought regarding whether there was study contamination.

Budget and procurement alterations

The trial stared enrolment on 4 February 2020, and the first COVID-19 case in Uganda was reported on 21 March 2020.12 The study team therefore incurred unanticipated purchases and budget modifications to ensure continuity of study activities, and safety of the team and participants.

Supply chain interruptions

A prominent implication of the COVID-19 pandemic was the degree to which services were entirely shut down. This meant that there were interruptions in procuring and obtaining equipment and materials needed for crucial elements of the clinical trial, which led to a delay in research activities.

Human resource considerations

The study team members reported low levels of COVID-19 health literacy. The trial directors hired more staff who had received training in infection prevention and control measures for COVID-19. The new personnel conducted screening, 4 hourly surface disinfection and provided training and education for study participants. Other precautionary measures are highlighted in table 3. Additionally, the trial suffered some personnel losses since some team members were unable to continue participating in the research activities.

Loss to follow-up of enrolled participants

Some security companies downsized, and participants lost their jobs, therefore, they had to be removed from the trial as they no longer met the inclusion criteria. Others could not be reached due to their poor phone network connectivity, while others simply refused to take calls from the study team.

Adherence to ethical principles of research

Ethical approvals for protocol deviations

The trial protocol and consent forms were modified to reflect the changes mentioned in table 3 and submitted to the review board for approval before the trial could proceed. The research team felt that the modifications were minor and did not necessitate a complete discontinuation of the trial. However, because of the COVID-19 restrictions, there was a substantial delay before this was approved.

Balancing risks and benefits

The study team conducted daily assessments of predictable risks to both the staff and the trial participants in comparison with potential benefits. The trial was eventually halted, and several contingency plans were initiated to ensure safe continuity of some research activities.

Discussion

This substudy explored the trial team and participants’ experiences of participating in an ongoing clinical trial during a pandemic. Three themes emerged for the participants’ experiences: effects on accessing HIV treatment and care, misinformation and difficulty participating in research activities. The study team reflections focused on the management of the clinical trial, effects of the local regulations and government policies and the need to adhere to ethical principles of research.

One of the greatest implications for this clinical trial were the knock-on effects of the local regulations and government policies. In March 2020, the government of Uganda enforced several COVID-19 restrictions including travel bans, border closures, nationwide lockdowns and curfews, and suspension of mass gatherings.12 While this strategy maybe efficacious in preventing the transmission of COVID-19, it could aggravate non-COVID-19 related health outcomes.15 Additionally, as in this study, these effects may include difficulties in accessing lifesaving treatment, or participating in research activities. Furthermore, results from mathematical modelling suggest that interruption to condom supply and health education could make populations more vulnerable to increases in HIV incidence.16 In agreement with,17 this suggests the need for appropriate government agencies and research regulatory bodies to develop systems that can ensure continuity of essential services and research even when lockdowns and travel bans are in effect. Research and ethics committees might consider asking researchers conducting trials in HIV, to submit a contingency plan if participants are unable to access their treatment and care.

An important consideration is the need to plan for different forms of support for research participants and PLWHA during a pandemic. The difficulty in continuing ART treatment was a recurring issue among many of the participants who missed clinic visits. This agrees with Opio and colleagues in Uganda who reported some of the major reasons for loss to follow-up as the long distance from home to the health facility for drug replenishment and limited capacity at lower level ART clinics.18 In hindsight, HIV research teams could have provided participants with transfer letters to new facilities or home delivery of ART.19 For example, the research team from a tuberculosis clinical trial made arrangements for delivery of medicines to the homes of participants who gave prior consent.20 Another form of support could be psychosocial support where participants are availed a phone number that they can contact for any further pertinent discussions or a routine follow-up phone call in the absence of in-person visits. At the policy level, Rewari and colleagues recommend instituting measures and guidelines to minimise ART supply shocks and to prepare for future emergencies.4

Another challenge that the research participants faced was the misinformation regarding COVID-19. Some participants halted their treatment because of misinformation from their peers about the relationship between ART and infection with COVID-19. Coincidentally, the information from peers encouraged adherence to ART. This followed reports that patients with both HIV and SARS‐CoV‐2 coinfected patients may have a less severe clinical picture of COVID-19 if they are already receiving ART.21 Unfortunately, they altered the information that people on ART were less likely to get the COVID-19 infection. To prevent this, researchers should make every effort to get well informed about a new health threat (within the limits of available information), so that they can advise participants appropriately but also make robust plans on how to manage the research. Researchers are therefore encouraged to design information and initiatives to advance research literacy and serve as a source for correct information. This will maintain trust and encourage continued participation and engagement22–24 and prevent unnecessary fear and distress.25 Participants should receive regular practical tips on handling the disruption in their work life and giving them hope that normal research activities will resume once the pandemic abates.26–28

The principle of beneficence requires those in positions of responsibility to act with the best intentions for all those under their jurisdiction,29 therefore trial managers must be cognizant of maintaining the integrity of the trial while ensuring the safety of the participants.30 The COVID-19 pandemic poses potential serious risks for clinical trial participants and staff engaged in health research. Researchers should ensure that participant safety is always supreme.29 For instance researchers may close a clinical trial where the risk of exposure to COVID-19 is high.20 Anker and colleagues discourage the hasty permanent termination of ongoing clinical trials unless they are nearing planned completion or have not yet started.30 In this case, we initially stopped all procedures that prevented the social distancing requirements such as venepuncture. Eventually, we halted participant recruitment and face-to-face follow-up visits.

Before the pandemic, many researchers only used in-person methods for follow up-visits. This period has seen clinical researchers consider several other options including the use of mobile apps, and other remote platforms to conduct research visits.26 In this study, we used both Zoom and phone interviews to collect the follow-up data for the clinical trial. The telephone interviews drastically improved the time efficiency for following up participants, reduced the expenditure for participants’ transport compensation, and provided access to participants who were geographically distant or located in high COVID-19 transmission areas. This agrees with Block and Erskine,31 that telephones give researchers access to diverse resources and experiences without the inconvenience, the expense and the time expended in travel. However, the phone follow-up was a challenge for some participants who developed reactions to the HIV medication and those who needed support with initiating PrEP. Additionally, several ethical issues and unscrupulous behaviours may also arise from the use of these new methods like Zoom such as potential abuse and exploitation.32 33 Potential difficulties such as lack of technology expertise, confidentiality challenges, reimbursement matters,34 poor phone network and low internet connectivity need to be addressed first.

The strength of the study lies in the opportunity to get both research team and participants’ perceptions about conducting or participating in a clinical trial during a pandemic. One limitation of the study may have been the methods of data collection. With phone interviews, it was neither possible to observe non-verbal cues during the IDIs, nor the non-verbal interaction of participants during the FGDs. Additionally, study team members may have participated out of an obligation to the trial team leaders. This was mitigated by requesting written consent prior to participation in the study, and the constant reminder that it was not mandatory to participate, and non-participation would not affect their employment in the study trial.

Conclusions and policy implications

The major implications for participants were the challenges in accessing HIV treatment and care, misinformation, and difficulty in participating in research activities. The major effects on the trial from the research team perspectives, were the cumulative effects of local regulations, the unforeseen protocol modifications, and the ethics committee reporting requirements. The relevant government agencies and research regulators are strongly encouraged to develop policies and guidelines in preparedness for the continuity of research and clinical trials in the event of future pandemics or epidemics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by a NURTURE fellowship award funded under training Grant Number D43TW010132 (PI: Nelson K Sewankambo) from the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the supporting institutions. The authors acknowledge all the members of the WISe-Men Trial team and the trial participants who soldiered on during the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the ensuing lockdown and travel restrictions in Uganda. Your courage made this study possible.

Footnotes

Twitter: @fredkitutu

Contributors: PAM is the Principal Investigator of the WISe-Men clinical trial and was involved in data collection, analysis and drafting the manuscript. RN is the WISe-Men trial manager and was involved in data collection, analysis and drafting the manuscript. NK and NS are both coinvestigators and supervisors on the WISe-Men trial, were involved in designing the study and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. TDN is a coinvestigator on the WISe-Men trial and was involved in conceptualising the study and drafting the work. PK and RM made substantial contribution to the conception of the study, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content especially around IRB and ethical issues. EMN made substantial contribution to the design of the study and was involved in data analysis and drafting the work. JN and FEK were critical in inductive content analysis of the findings from IDI and FGD’s and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content related to access to HIV treatment and care. CPO was involved in the early conception of the study, generation of study themes and drafting the work, LK and MN were involved in data collection from both trial team members and study participants and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, specifically the Methods section. All the authors gave final approval of the work to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data will be available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This substudy ethical approval was granted by the School of Health Sciences Research and Ethics Committee at Makerere University (Ref. Number: 2018-054). Additional approval was obtained from the UNCST (Ref Number: HS 2672). The initial study design did not include telephone or Zoom interviews; therefore, additional approval for these changes was obtained in August 2020. All interactions with the participants were audio-recorded with permission.

References

- 1.Gorbalenya AE, Baker SC, Baric RS. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: the species and its viruses–a statement of the coronavirus Study Group. bioRxiv 2020;10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses . The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat Microbiol 2020;5:536–44. 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard, 2020. Available: https://covid19.who.int/ [Accessed 13 Jun 2020].

- 4.Rewari BB, Mangadan-Konath N, Sharma M. Impact of COVID-19 on the global supply chain of antiretroviral drugs: a rapid survey of Indian manufacturers. WHO South East Asia J Public Health 2020;9:126–33. 10.4103/2224-3151.294306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oladele TT, Olakunde BO, Oladele EA, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on HIV financing in Nigeria: a call for proactive measures. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002718. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jewell BL, Mudimu E, Stover J, et al. Potential effects of disruption to HIV programmes in sub-Saharan Africa caused by COVID-19: results from multiple mathematical models. Lancet HIV 2020;7:e629–40. 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30211-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang H, Zhou Y, Tang W. Maintaining HIV care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet HIV 2020;7:e308–9. 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30105-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo W, Weng HL, Bai H, et al. [Quick community survey on the impact of COVID-19 outbreak for the healthcare of people living with HIV]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2020;41:662–6. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20200314-00345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun S, Hou J, Chen Y. Challenges to HIV care and psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic among people living with HIV in China. AIDS Behav 2020:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagat H, Sharma M, Kariithi E. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV testing and assisted partner notification services, Western Kenya. AIDS Behav 2020:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linnemayr S, Jennings Mayo-Wilson L, Saya U. HIV care experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: mixed-methods telephone interviews with clinic-enrolled HIV-infected adults in Uganda. AIDS Behav 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.GOU . COVID-19 response info hub-Timeline 2020, 2020. Available: https://covid19.gou.go.ug/timeline.html [Accessed 6 Sep 2020].

- 13.UNCST . New research registration procedures 2020. Available: https://www.uncst.go.ug/new-research-registration-procedures/ [Accessed 13 Jun 2020].

- 14.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mhango M, Chitungo I, Dzinamarira T. COVID-19 lockdowns: impact on facility-based HIV testing and the case for the scaling up of home-based testing services in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Behav 2020;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jewell BL, Mudimu E, Stover J, et al. Potential effects of disruption to HIV programmes in sub-Saharan Africa caused by COVID-19: results from multiple mathematical models. Lancet HIV 2020;7:e629–40. 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30211-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierre G, Uwineza A, Dzinamarira T. Attendance to HIV antiretroviral collection clinic appointments during COVID-19 lockdown. A single center study in Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS Behav 2020:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Opio D, Semitala FC, Kakeeto A, et al. Loss to follow-up and associated factors among adult people living with HIV at public health facilities in Wakiso district, Uganda: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:628. 10.1186/s12913-019-4474-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rebeiro PF, Duda SN, Wools‐Kaloustian KK, et al. Implications of COVID‐19 for HIV research: data sources, indicators and longitudinal analyses. J Int AIDS Soc 2020;23:e25627. 10.1002/jia2.25627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rusen ID. Challenges in tuberculosis clinical trials in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: a sponsor’s perspective. Trop Med Infect Dis 2020;5:86. 10.3390/tropicalmed5020086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel RH, Pella PM. COVID-19 in a patient with HIV infection. J Med Virol 2020;92:2356–7. 10.1002/jmv.26049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gobat N, Butler CC, Mollison J, et al. What the public think about participation in medical research during an influenza pandemic: an international cross-sectional survey. Public Health 2019;177:80–94. 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sentell T, Vamos S, Okan O. Interdisciplinary perspectives on health literacy research around the world: more important than ever in a time of COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3010. 10.3390/ijerph17093010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bikson M, Hanlon CA, Woods AJ, et al. Guidelines for TMS/tES clinical services and research through the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Stimul 2020;13:1124–49. 10.1016/j.brs.2020.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah SGS, Farrow A. A commentary on ‘World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel Coronavirus (COVID-19)’. Int J Surg 2020;76:128–9. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padala PR, Jendro AM, Padala KP. Conducting clinical research during the COVID-19 pandemic: investigator and participant perspectives. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020;6:e18887. 10.2196/18887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunlop A, Lokuge B, Masters D, et al. Challenges in maintaining treatment services for people who use drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Harm Reduct J 2020;17:26. 10.1186/s12954-020-00370-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osseni IA. COVID-19 pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa: preparedness, response, and hidden potentials. Trop Med Health 2020;48:48. 10.1186/s41182-020-00240-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hlongwa P. Current ethical issues in HIV/AIDS research and HIV/AIDS care. Oral Dis 2016;22:61–5. 10.1111/odi.12391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anker SD, Butler J, Khan MS, et al. Conducting clinical trials in heart failure during (and after) the COVID-19 pandemic: an expert consensus position paper from the heart failure association (HFA) of the European Society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2020;41:2109–17. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Block ES, Erskine L. Interviewing by telephone: specific considerations, opportunities, and challenges. Int J Qual Methods 2012;11:428–45. 10.1177/160940691201100409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bashshur R, Doarn CR, Frenk JM, et al. Telemedicine and the COVID-19 pandemic, lessons for the future. Telemed J E Health 2020;26:571–3. 10.1089/tmj.2020.29040.rb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hau YS, Kim JK, Hur J, et al. How about actively using telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic? J Med Syst 2020;44:108. 10.1007/s10916-020-01580-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright JH, Caudill R. Remote treatment delivery in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychother Psychosom 2020;89:130–2. 10.1159/000507376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-048825supp001.pdf (34.9KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Data will be available upon reasonable request.