Abstract

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children has become a recognised syndrome, whereas a parallel syndrome in adults, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults (MIS-A), has not been well defined. Most cases occur several weeks following confirmed or suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection, but none have been reported in association with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Here we describe the case of a 22-year-old man, who received the inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine 6 weeks following a mild COVID-19 infection. He presented after his second dose of the vaccine with a clinical picture of a multisystem inflammatory syndrome-like illness. Additionally, there was laboratory evidence of acute inflammation. The patient’s condition markedly improved after initiation of steroids. Whether the vaccine augmented an already-primed immunity from the infection and contributed to the occurrence of MIS-A is difficult to prove. Understanding the pathogenesis of this condition will shed light on this question and entail major implications on treatment and prevention.

Keywords: COVID-19, unwanted effects/adverse reactions, prevention

Background

Vaccines to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection are considered the most promising approach for controlling the pandemic. While safety of many of these vaccines has been projected from phase I and II studies, monitoring of authorised vaccines is continuing to track problems or side effects that were not detected during the clinical trials. If there are problems with the vaccines, they are most likely to emerge early in the testing process when they can be identified and addressed. Systemic signs and symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, headache, chills, myalgia and arthralgia, can occur following COVID-19 vaccination; however, most systemic postvaccination signs and symptoms are mild to moderate in severity, occur within the first 3 days of vaccination and resolve within 1–2 days of onset.1

BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm) is an inactivated vaccine based on a SARS-CoV-2 isolate from a patient in China; it has an aluminium hydroxide adjuvant.2 This vaccine has been licensed in the United Arab Emirates based on interim data from a phase III efficacy data that showed the vaccine to have 99% seroconversion rate of neutralising antibody and 100% effectiveness in preventing moderate and severe cases of the disease. Furthermore, the analysis showed no serious safety concerns.3

A multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection has been defined in children (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, MIS-C) and adolescents. There have been recent reports of cases with a similar syndrome in adults (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults, MIS-A) identified in the USA and the UK, since June 2020. According to these reports, the syndrome appears to be potentially more complicated in adults than in children.4

In this case report, we shall present an entity of adult multisystem inflammatory syndrome that occurred following the administration of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in an individual with a recent history of mild COVID-19.

Case presentation

A previously healthy 22-year-old man presented to our emergency department in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates in December. This patient was diagnosed with mild COVID-19 illness, sore throat and loss of sense of smell as well as positive COVID-19 PCR, 0n 26 October 2020. Following full recovery by resolution of symptoms and reverting to negative PCR, he received the first dose of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine on November 6. Following the first dose of vaccine, he remained asymptomatic and well. He received the second dose on 6 December 2020. A few hours later the patient started to experience headache and fatigue. The day after, he started to develop fever, sore throat and abdominal pain. The illness progressed over the following 4 days when he presented to the emergency department with high-grade fever, myalgia, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, and a faint erythematous non-itchy rash over his torso that he noticed earlier that day. The patient reported a dry irritant cough but no shortness of breath or chest discomfort. He had no urinary symptoms and no pain or swelling of his joints.

The patient had no history of recent travel, no sick contacts, no animal exposure and no consumption of raw dairy products. He was not on any chronic medications and had no known allergies. He reported taking ibuprofen and one dose of an antibiotic over the prior few days for symptomatic relief. He was a non-smoker and did not use recreational drugs.

In the emergency department the patient was noted to have a temperature of 39°C, systolic blood pressure of 110 mm Hg and tachycardia, 140 beats per minute. Physical examination revealed dry mucous membranes with congested throat. Bilateral conjunctival injection and left conjunctival haemorrhage. There was a generalised erythematous maculopapular rash, mostly over the chest and back. His peripheral lymph nodes were not enlarged. There were no audible cardiac murmurs, his chest was clear to auscultation, abdomen examination was unremarkable.

Investigations

Laboratory investigations on presentation are outlined in table 1. SARS-CoV-2 PCR from nasopharyngeal swab was negative, however SARS-CoV-2 IgG from serum using Liaison XL SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG reagent was later found to be strongly positive at 345 AU/mL (more than 15 AU/mL: positive result). Throat swab was negative for group A streptococcus, sputum culture showed mixed flora and bacterial blood cultures were negative. Urinalysis showed significant proteinuria of more than 300 µg. ANA, dsDNA, c-ANCA and p-ANCA titres were all negative; C3 and C4 were however reduced.

Table 1.

Lab investigation results on admission day

| Lab value | Admission day | Reference range |

| WBC (10 9/L) | 15 | 4–12.4 |

| Platelet (109/L) | 122 | 130–400 |

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | 115 | 63.6–110.5 |

| AST (U/L) | 53 | 5–34 |

| ALT (U/L) | 81 | 0–55 |

| Direct bilirubin (µmol/L) | 35 | 0–8.6 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 16 | 35–50 |

| C reactive protein (mg/L) | 249 | 0–5 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 4357 | 21–274 |

| D-dimer (mg/mL) | 14 | 0–0.5 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 9 | 0–0.1 |

| Interleukin-6 (pg/mL) | 90 | 0–7 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; WBC, white blood cell.

Treatment

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for hypotension, with diagnosis of probable sepsis versus vaccine-related illness. He was treated empirically with ceftriaxone and levofloxacin. In addition to intravenous fluids for resuscitation, he was also given intravenous hydrocortisone 100 mg two times per day. The hydrocortisone was given for 2 days and subsequently stopped once patient achieved haemodynamic stability.

The patient’s blood pressure stabilised. Fever initially improved but remained persistent throughout his ICU stay. He quickly started to develop facial puffiness and generalised body oedema. He remained tachycardic, diarrhoea persisted, watery occasionally with incontinence. It was difficult for the patient to mobilise without the support of a walking frame as a result of the myalgia and the anasarca.

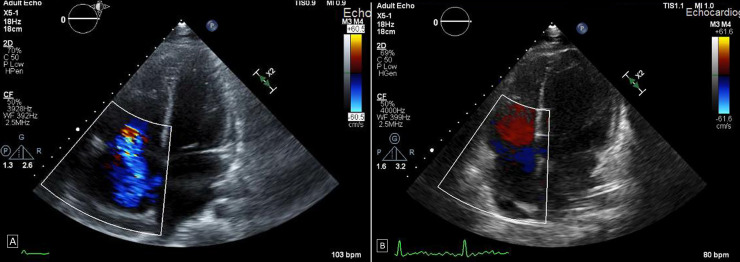

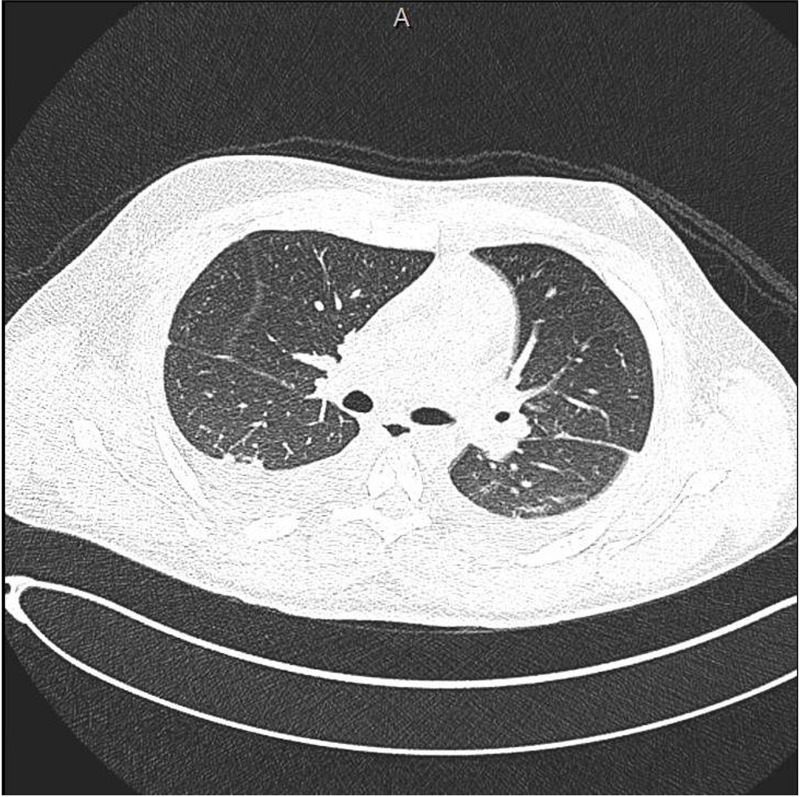

Further workup revealed evidence of renal impairment with significant proteinuria. An ECG showed sinus tachycardia with non-specific T-wave abnormalities, troponin-I was raised at 0.29 ng/mL and pro-BNP over 8000 pg/mL. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed severe tricuspid regurgitation with normal structure of the tricuspid valve. There was pulmonary hypertension, PASP of 46 mm Hg. The right atrium and ventricle were moderately dilated with normal systolic function. Left ventricle cavity size was normal with mildly reduced ejection fraction of 45%. There was a thin rim of pericardial effusion (figure 1A). A computed topography scan of the chest was negative for pulmonary embolism, however it showed evidence of bilateral moderate pleural effusion along with basal atelectasis (figure 2).

Figure 1.

(A) Initial transthoracic echocardiogram showing the right atrium and ventricle moderately dilated. There was a thin rim of pericardial effusion. Severe tricuspid regurgitation. (B) Repeat transthoracic echocardiography after treatment with dexamethasone showing normal size of the right atrium and ventricle. Trace tricuspid regurgitation.

Figure 2.

Axial computed topography scan of the chest: evidence of bilateral moderate pleural effusion along with basal atelectasis.

As the patient achieved relative haemodynamic stability, the hydrocortisone was discontinued, and the patient was shifted to the medical ward. Gradually the high-level fever began to recur. By that time all cultures came back negative, and other workup was unrevealing.

Towards the end of the first week after admission it was apparent that the cause of the patient’s illness was not due to an infective cause, neither it was due to an acute flare of a rheumatologic disease. Considering the multisystem involvement, cardiac, renal, haematologic, dermatologic and ophthalmologic in addition to raised inflammatory markers, our patient met the criteria for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults. The patient underwent therapy with intravenous steroids, dexamethasone 6 mg daily.

Outcome and follow-up

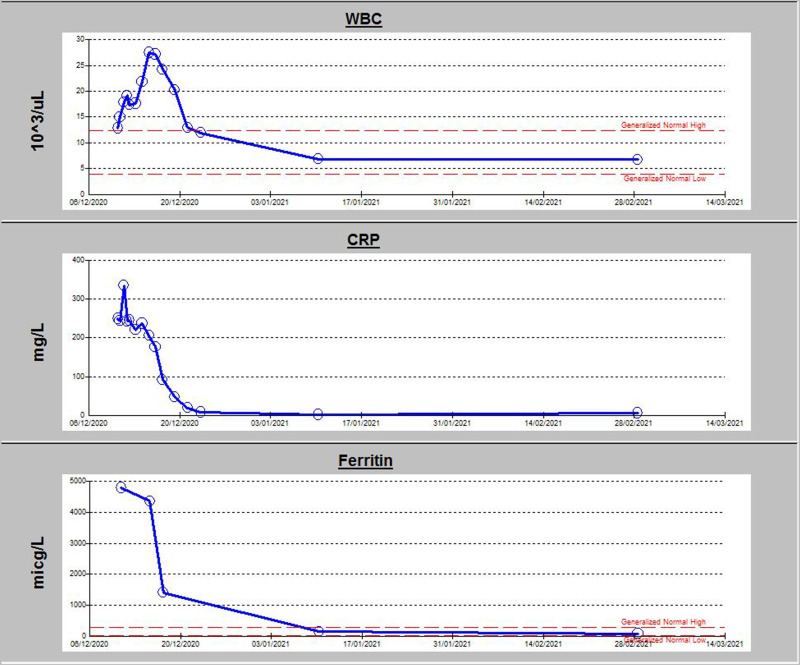

The patient’s condition improved markedly after initiation of dexamethasone, his generalised oedema subsided over the following few days, skin rash and conjunctivitis resolved, white blood cell count normalised and renal function including albuminuria improved. His inflammatory markers came down to normal levels (figure 3). A repeat transthoracic echocardiography showed trace tricuspid regurgitation, marked improvement in right ventricular systolic function, with normal size of the right atrium and ventricle. The pulmonary artery systolic pressure normalised (figure 1B).

Figure 3.

Graph illustrating trend in inflammatory markers during patient’s hospital stay. CRP, C reactive protein; WBC, white blood cell.

Dexamethasone was continued for 8 days and then switched to oral prednisolone. He was discharged home with a tapering dose of prednisolone over a period of 2 weeks. When seen in the outpatient clinic 2 weeks following discharge from the hospital, the patient’s symptoms resolved although some general weakness and fatigue. His repeat echocardiogram was completely normal.

Discussion

The case definition for MIS-C has been well defined, and subsequently the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report described criteria that fulfilled a working case definition for MIS-A outlined in box 1.4 Our patient, a previously healthy young adult, met these criteria.

Box 1. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) criteria for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults.

MMWR criteria

A severe illness requiring hospitalisation in a person aged ≥21 years.

A positive test result for current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection (nucleic acid, antigen or antibody) during admission or in the previous 12 weeks.

Severe dysfunction of one or more extrapulmonary organ systems (eg, hypotension or shock, cardiac dysfunction, arterial or venous thrombosis or thromboembolism or acute liver injury).

Laboratory evidence of severe inflammation (eg, elevated C reactive protein, ferritin, D-dimer or interleukin-6).

Absence of severe respiratory illness (to exclude patients in which inflammation and organ dysfunction might be attributable simply to tissue hypoxia). Patients with mild respiratory symptoms who met these criteria were included. Patients were excluded if alternative diagnoses such as bacterial sepsis were identified.

Several features of our patient’s presentation were consistent with MIS-A, including hypotension and cardiac dysfunction. Moreover, our patient’s stable respiratory status was itself a feature shared by patients with MIS-A, who often lack intrinsic respiratory disease.

Other features included a skin rash, conjunctivitis and mucositis. Additionally, he had persistent fever, gastrointestinal symptoms and AKI. Prominent gastrointestinal symptoms are seen in many patients with MIS-C and most of the described adults with MIS-A. Our patient also had persistently high-inflammatory markers, including leukocytosis with neutrophilia and lymphopaenia.5

Finally, and most importantly, there was no alternative diagnosis to explain his symptoms or laboratory findings. This has been supported by the extensive workup done for the patient which revealed no focus of infection.

It is worth mentioning that our patient had interesting cardiac findings, his cardiac dysfunction was primarily right-sided. Echocardiogram showed severe tricuspid regurgitation and high pulmonary artery pressure, while CT scan showed no evidence of pulmonary embolism. It is interesting to speculate whether he had a COVID-19-related vasculitis process leading to elevated pulmonary vascular resistance and subsequent right ventricular strain. Intriguingly all these echocardiogram findings almost completely resolved after steroid therapy.

The interval between infection and development of MIS-A is unclear. In patients who reported typical COVID-19 symptoms before MIS-A onset, MIS-A was experienced approximately 2–5 weeks later. However, in patients with no preceding symptoms it is difficult to estimate when initial infection occurred.4

Our patient developed this condition 6 weeks following the infection and immediately after the second dose of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. The relatively long interval between infection and the immediate development of MIS-A following the second dose of vaccine raises concern that the vaccine may have triggered the patient into developing this disease entity. It would have been interesting to know the IgG level he attained from his COVID-19 illness before his vaccination, unfortunately this was not done.

Our patient received an inactivated vaccine with an aluminium hydroxide adjuvant. A potential concern about the use of aluminium adjuvants is that this vaccine platform has been associated with immunopathology including enhanced disease in animal models of SARS-CoV-1 and MERS vaccines.6 7 On the other hand, no evidence for this was seen in the studies with two aluminum-adjuvanted coronavirus vaccines.8 9 Instead, aluminium formulations may actually reduce immunopathology compared with unadjuvanted coronavirus vaccines.9 10 Other vaccines developed and currently in use for COVID-19, such as mRNA and adenovirus vector vaccines avoid the interference with protein targets and potentially unwanted immune responses.11

Case reports indicate that patients with MIS-A have been treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, corticosteroids or with the interleukin-6 inhibitor, tocilizumab.4 In a series that describes seven previously healthy, young adult men who experienced mixed cardiogenic and vasoplegic shock and hyperinflammation along with high SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin G antibody titres, were all treated with corticosteroids and recovered and were discharged home after 7–18 days.12 Similarly our patient was treated with dexamethasone 6 mg daily and responded rapidly and successfully to the treatment.

While it is not fully understood how serological responses correlate with protection from infection or disease, there is general agreement that people who have had COVID-19 should get a vaccine. However, it is when the vaccine should be administered, how many doses, what is the appropriate interval between doses and whether any particular vaccine platform is preferable remains to be answered. Studies on COVID-19 vaccines that include patients who recovered from COVID-19 infection and therefore the side effects of various vaccines in this population are still undefined as the results are still awaited. Recent data on healthcare workers support that recovery from a COVID-19 and the presence of anti-spike or anti-nucleocapsid IgG antibodies was associated with a substantially reduced risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection at least in the short term, up to 6 months.13 This probably indicates that immunity to reinfection can last for up to 6 months; hence vaccination can be delayed in patients who have evidence of immunity or previous infection. Many authorities including the CDC are advising a 3-month interval between the infection and the vaccination.14

Learning points.

What we describe may be a new entity of inactivated vaccine-induced multisystem inflammatory syndrome in adults, possibly due to immune system over-reaction to the inactivated vaccine in the setting of an already-primed immune system from prior COVID-19 infection.

Dexamethasone achieved rapid and full recovery and can be considered for treatment in similar cases.

The need for vaccinating patients who already got COVID-19 infection and when to administer the inactivated vaccine requires further study as potential side effects might arise if the inactivated vaccine is administered early and immune response to the initial infection is robust.

Footnotes

Contributors: AKU is the primary infectious disease consultant of the patient, and was responsible for collecting clinical history, drafting of the manuscript and manuscript review. NMMH was involved in collecting clinical history, follow-up, drafting of the manuscript and manuscript review. MSAG was responsible for clinical data collection, follow-up, drafting of the manuscript and manuscript review. KMMS was involved in clinical data collection, follow-up, drafting of the manuscript and manuscript review.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Center for disease control . Post vaccine considerations for healthcare personnel, 2020. Available: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/is-the-covid19-vaccine-safe

- 2.Xia S, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBIBP-CorV: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2021;21:39–51. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30831-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emirates News Agency . UAE Ministry of Health and Prevention announces officialregistration of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine used in #4Humanity Trials, 2020. Available: wam.ae

- 4.Morris SB, Schwartz NG, Patel P, et al. Case Series of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Adults Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection - United Kingdom and United States, March-August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1450–6. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6940e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kofman AD, Sizemore EK, Detelich JF, et al. A young adult with COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)-like illness: a case report. BMC Infect Dis 2020;20:716. 10.1186/s12879-020-05439-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghimire TR. The mechanisms of action of vaccines containing aluminum adjuvants: an in vitro vs in vivo paradigm. Springerplus 2015;4:181. 10.1186/s40064-015-0972-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham BS. Rapid COVID-19 vaccine development. Science 2020;368:945–6. 10.1126/science.abb8923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen W-H, Tao X, Agrawal AS, et al. Yeast-Expressed SARS-CoV recombinant receptor-binding domain (RBD219-N1) formulated with aluminum hydroxide induces protective immunity and reduces immune enhancement. Vaccine 2020;38:7533–41. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Q, Bao L, Mao H, et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020;369:77–81. 10.1126/science.abc1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hotez PJ, Corry DB, Bottazzi ME. COVID-19 vaccine design: the Janus face of immune enhancement. Nat Rev Immunol 2020;20:347–8. 10.1038/s41577-020-0323-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tregoning JS, Brown ES, Cheeseman HM, et al. Vaccines for COVID-19. Clin Exp Immunol 2020;202:162–92. 10.1111/cei.13517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chau VQ, Giustino G, Mahmood K, et al. Cardiogenic shock and hyperinflammatory syndrome in young males with COVID-19. Circ Heart Fail 2020;13:e007485. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.007485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lumley SF. Status and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers antibody status and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers. NEJM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frequently asked questions about covid-19 vaccination. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/faq.html