Abstract

Objectives

Confirm existence of COVID-19 outbreak, conduct contact tracing, and recommend control measures.

Methods

Two COVID-19 cases in Sana’a Capital met the WHO case definition. Data were collected from cases and contacts who were followed for 14 days. Nasopharyngeal swabs were taken for confirmation by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

Results

Two confirmed Yemeni male patients aged 20 and 40 years who had no travel history were admitted to hospital on 24 April 2020. Regarding the first patient, symptoms started on April 18th, 2020 then the patient improved and was discharged on May 5th, while the second patient’s symptoms started on April 22nd but the patient died on April 29th, 2020. Both patients had 54 contacts, 17 (32%) were health workers (HWs). Four contacts (7%) were confirmed, two of them were HWs that needed hospitalization. The secondary attack rate (sAR) was 12% among HWs compared to 5% among other contacts.

Conclusions

First COVID-19 outbreak was confirmed among Yemeni citizens with a high sAR among HWs. Strict infection control among HWs should be ensured. Physical distancing and mask-wearing with appropriate disinfecting measures should be promoted especially among contacts. There is a need to strengthen national capacities to assess, detect, and respond to public health emergencies.

Keywords: COVID-19, Outbreak, Contact tracing, Health workers, Yemen

Introduction

Coronaviruses are a family of viruses that can cause illnesses such as the common cold, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) (Mayo clinic, 2020). On December 29th, 2019, the first four cases were reported with Novel Coronaviruses Infected Pneumonia at Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan city, China (Jin et al., 2020). On March 12th, 2020, WHO announced the COVID-19 is a world Pandemic (Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020). The SARS disease that is caused by Corona virus 2 is referred to by the International Committee for Classification of Viruses as SARS-CoV-2 (WHO, 2020a).

People with COVID-19 have a wide range of symptoms ranging from asymptomatic mild symptoms to severe illness (CDC, 2020a). The common clinical features of COVID-19 are fever, cough, pneumonia, fatigue, and shortness of breath (Chen et al., 2020, Song et al., 2020). Around 80% of COVID-19 patients have mild symptoms and recovered without any medication (WHO, 2020b). According to CDC, the incubation period for COVID-19 is thought to extend to 14 days, with a median time of 4–5 days from exposure to symptoms onset (Guan et al., 2020, Lauer et al., 2020). COVID-19 is spread mainly from person to person through close contact, and some asymptomatic people may be able to spread the virus (CDC, 2020b). It crosses the country’s borders easily and spreads very quickly as a pandemic (Cucinotta and Vanelli, 2020).

Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic is now a major health threat. Based on the WHO report at the end of February 2021,113,467,305 confirmed cases have been reported in almost all countries and regions around the world, including more than 2,520,550 deaths (WHO, 2020c). In the Eastern Mediterranean Region, all countries of the region have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and by the end of February 2021 the total number of confirmed cases was 6,388,249, while most of the confirmed cases were concentrated in Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Morocco and United Arab Emirates (EMPHNET, 2020).

In Yemen, the first confirmed case was reported from the South on April 10th, 2020 at Hadramout governorate in a Yemeni citizen working in the port of Ash Shihr city in the seventh decade of his life. The symptoms appeared after contact with workers from shipping vessels, and the result of the laboratory test by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) was positive (Alshaikhli et al., 2020).

From Northern governorates, the first notification was received on April 25th by the General Directorate of Surveillance at the Ministry of Public Health and Population (MoPHP) from the Sana’a Capital surveillance officer regarding the presence of two COVID-19 suspected cases at the COVID-19 isolation center of Al-Kuwait University Hospital, Sana’a Capital. On April 26th, 2020, a team from the Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) was deployed to investigate and confirm the presence of COVID-19 outbreak, conduct contact tracing, and make recommendations for prevention and control.

Methods

The two suspected cases were interviewed using the WHO case definition (WHO, 2020d), and demographic characteristics and clinical data were collected. The list of contacts was developed using the contact definition of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (Ecdc) (Ecdc, 2020). The contacts were classified according to exposure into close and causal contact and according to the occupation into Health Workers (HWs) and non-health workers. Data on demographic characteristics and exposure were collected from contacts at the quarantine sites. A nasopharyngeal swab was collected from all cases and contacts and sent for confirmation by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) in the National Center of Public Health Laboratories. Contact tracing was conducted for 14 days. Data were entered in an Excel sheet and analyzed by Epi-info version 7.2. The results were presented by figures and tables.

Results

Description of cases

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the two suspected patients. Both patients were confirmed as COVID-19 cases by PCR on April 26th, 2020. The first patient was admitted to the inpatient department and dramatically improved with a downward trend in his inflammatory markers. The patient was discharged on day 13 of admission.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics and clinical features of the first two COVID-19 cases, Sana’a Capital, April 2020.

| Characteristics | 1st patient | 2nd patient |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | Male |

| Age | 40 | 26 |

| Marital status | Married | Married |

| Occupation | Judge | Daily labor |

| Address | Al-Jarf neighborhood | Al-Hathili neighborhood |

| District | Al-Sabean District | Al-Thawra District |

| Date of onset | April 18th, 2020 | April 22nd, 2020 |

| Date of admission | April 24th, 2020 | April 24th, 2020 |

| Severity of illness | Moderate | Severe |

| Clinical symptoms | Fever, non-productive cough and sore throat | Fever and non-productive cough with shortness of breath |

| Vital signs when admission | Temperature = 38.1 C° | Temperature = 38.8 C° |

| SpO2 = 92% | SpO2 = 63% | |

| Respiratory Rate = 28 | Respiratory Rate = 41 | |

| Heart rate = 82 | Heart rate = 96 | |

| Chronic disease | No history of chronic disease | No history of chronic disease |

| Admission place | Men in-patient ward | Intensive Care Unit |

| Type of treatment | Analgesic, antipyretic and antibiotic | Ventilator + broad-spectrum antivirals, antibiotics, and intensive supportive care |

| Outcome | Improved and discharged | Died |

| Date of outcome | May 5th, 2020 | April 29th, 2020 |

| History of travel | No | No |

| History of contact with COVID-19 cases | No | No |

The second patient was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) on April 24th, 2020, and immediately put on a ventilator and ICU standard treatment in which his chest x-ray illustrated acute pneumonia in both lower lobes. His respiratory status deteriorated despite broad-spectrum antivirals, antibiotics, and intensive supportive care, and he died on day 6 of admission.

Contact tracing

The first patient had 21 contacts, 14 (67%) of them were males, 7 (33%) were HWs and two were confirmed by PCR with one of them being an HW who need admission. The secondary attack rate (sAR) was 10%. The second patient had 33 contacts, of them 19 (58%) were males, 10 (30%) were HWs and two were confirmed by PCR; one was an HW who needed admission. The sAR was 6%. The sAR among HWs was 12% compared to 5% among other contacts. None of the contacts gave a history of travel or contact with a traveller. Table 2 shows the characteristics of contacts.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic, Exposure and Clinical characteristics of Contacts, Sana’a Capital, April 2020.

| Characteristics | No. of contacts (N = 54) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 21 | 39% |

| Male | 33 | 61% |

| Age | ||

| <18 | 12 | 22% |

| (18–>35) | 29 | 54% |

| (35–>45) | 6 | 11% |

| (45–>60) | 4 | 7% |

| ≥60 | 3 | 6% |

| Address by district | ||

| Al-Sabean | 21 | 39% |

| Al-Safiah | 11 | 20% |

| Al-Tahrir | 5 | 9% |

| Al-Thawrah | 9 | 17% |

| Ma’en | 7 | 13% |

| Sho’oab | 1 | 2% |

| Place of contact | ||

| COVID-19 Isolation center | 17 | 31% |

| Household | 27 | 50% |

| Work-place | 2 | 4% |

| Hotel | 8 | 15% |

| Type of Protective Personal Equipment (PPE) use for HWs (N = 17) | ||

| Surgical Mask | 15 | 88% |

| Gloves | 12 | 71% |

| N95 | 6 | 35% |

| Eye Google | 6 | 35% |

| Gown | 5 | 29% |

| No PPE use | 1 | 6% |

| Type of contact (N = 54) | ||

| Close contact | 31 | 57% |

| Causal contact | 23 | 43% |

| Result of PCR COVID-19 (N = 54) | ||

| Positive | 4 | 7% |

| Negative | 50 | 93% |

| Health status of contacts who were positive on PCR (N = 4) | ||

| Symptomatic | 2 | 50% |

| Asymptomatic | 2 | 50% |

| Type of contacts who were positive on PCR (N = 4) | ||

| HWs | 2 | 50% |

| Household | 1 | 25% |

| Work-place | 1 | 25% |

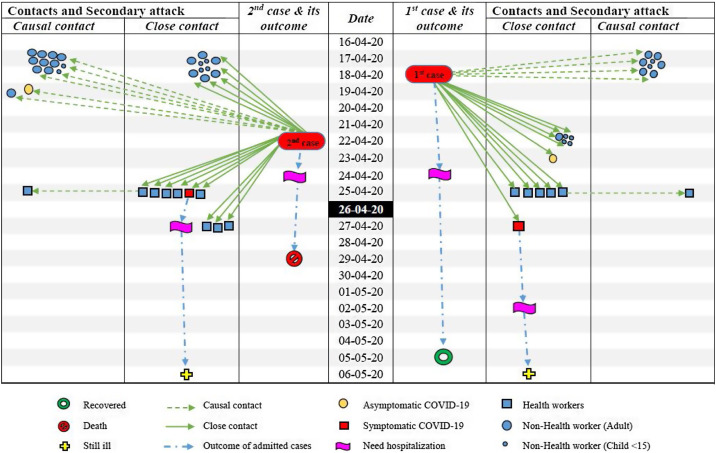

Figure 1 shows the transmission chain of the first two COVID-19 cases in Sana’a Capital. Two of the HWs were causal contacts, those had contact with other HWs who had direct contact with patients. Out of the 54 contacts who were traced, four were confirmed by PCR to be positive. Three out of the four confirmed cases were among close contacts. The fourth confirmed case was the shop owner where the second patient was working; however, he did not give a history of close contact with him.

Figure 1.

Transmission chain of first COVID-19 cases in Sana’a Capital, April 2020.

Discussion

Yemen is one of the countries that has suffered from siege, war, and conflict for more than five years, debilitating the health system and leaving only a little capacity to respond. However, this catastrophic situation was also given as an explanation for the late arrival of COVID-19 to Yemen (Kadi, 2020). This study will help to lay down the lessons learned and future opportunities for containment of the COVID-19 epidemic in Northern Yemen.

Regarding clinical features, fever and non-productive cough are the dominant symptoms in addition to shortness of breath; all of these are the most common symptoms reported throughout the literature on COVID-19 (Rodriguez-Morales et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2020), and also agreed with our findings.

In this study, we found one of the six confirmed patients (17%) needed ICU admission compared to (32%) in China (Huang et al., 2020) and none in Kurdistan, Iraq (Merza et al., 2020). Such variation may be attributed to the difference in affected age groups and the presence of co-morbid chronic diseases. The clinical status of this patient worsened, and he deteriorated to death. It seemed possible that he had a weak immune response that led to Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, which is a well-known cause of death in COVID-19 (Lee, 2017, Prompetchara et al., 2020).

In our findings, there is no travel history for all patients and contacts. This attributed to the blockade imposed on Yemen in addition to the closure of Sana'a airport for a long time, where Yemen became isolated from all countries of the world (Kadi, 2020).

In addition, the number of contacts between men was higher than women. In contrast, a study in Germany showed that sex ratios reveal higher contact among women than men at working ages; the opposite holds true at old age (Dörre and Doblhammer, 2020). However, a study in Taiwan showed that all types of contacts in women were higher than in men except in the household contacts, where the men became higher (Cheng et al., 2020). This can be explained by the fact that males constitute the majority of Yemen's workforce. Also, males have more contact with patients compared to females, who stay at home for long periods as a Yemeni traditional behaviour.

Increasing age was associated with an increase in COVID-19 risk. Our results showed that more than half of the contacts were between the ages of 18 to >35; this was nearly similar to other studies in Taiwan and South Korea (Cheng et al., 2020, Choe et al., 2020). In contrast, other studies in China and the USA showed an increase in risk among elderly contacts (Huang et al., 2020, McMichael et al., 2020). This might be explained by the fact that the Yemeni population pyramid indicates that 80% of the Yemeni peoples are less than 40 years old (Pelletier and Spoorenberg, 2015) and they might be getting infected with COVID-19 without showing any symptoms (asymptomatic) or showing mild symptoms and recovering without admission or taking any medication. In contrast, the elderly group may have chronic diseases, and they may become ill.

Furthermore, among contacts, the asymptomatic cases in this study were 50% of confirmed cases and this result is quite similar to the finding reported in Iraq (Merza et al., 2020). In contrast, another study in China showed that four-fifths of cases are asymptomatic (Michael, 2020). The prolonged political humanitarian crisis and lack of resources for COVID-19 testing in Yemen have weakened the surveillance system (Oxford Analytica Daily Brief, 2020). Furthermore, the stigma and the rumors about high mortality rates in COVID-19 isolation centers may prevent showing the actual size of the problem.

Regarding occupation, Health workers recorded the highest percentage, and this result is similar to previous studies in the USA and WHO report (McMichael et al., 2020, WHO Africa Region, 2020). This may be due to higher exposure to infected patients during health care and also may be due to less cautious or improper usage of PPE.

In view of the high attack rate among HWs that has been shown in this study and HWs’ carelessness in wearing PPE when dealing with cases and contacts in isolation and quarantine centers, aside from PPE unavailability, there is a strong need to ensure PPE availability and to impose its appropriate use by HWs, especially those with contact with a suspected COVID-19 patient, in addition to disinfecting surfaces, treating patients in a separate ward or hospital with a separate team, and contact tracing and quarantine (Ng et al., 2020). Moreover, the Yemeni health system needs to adopt lessons from other countries that successfully contained and mitigated COVID-19, such as China, South Korea, Singapore, and Germany, as well as to identify thresholds for “reopening,” or relaxing, stay-at-home orders and other restrictions.

Our study has some limitations, especially regarding the difficulty in collecting and accessing patients’ files and the lack of some important investigations such as computerized tomography and other blood tests in isolation centers. Furthermore, the stigma and the rumors about high mortality rates in COVID-19 isolation centers could prevent showing the actual size of the problem.

In conclusion, the first COVID-19 outbreak was confirmed among Yemeni citizens who had no travel history and with a high sAR among HWs. Strict infection control among HWs should be ensured. Physical distancing, mask-wearing, and appropriate disinfecting measures should be promoted especially among contacts. There is a need to strengthen national capacities to assess, detect, and respond to public health emergencies.

Transparency declaration

This article is published as part of a supplement titled, “Field Epidemiology: The Complex Science Behind Battling Acute Health Threats,” which was supported by Cooperative Agreement number NU2HGH000044, managed by TEPHINET (a program of The Task Force for Global Health) and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services, The Task Force for Global Health, Inc., or TEPHINET.

Author’s contributions

E. Al-Sakkaf contributed to the study design, collected, analyzed, interpreted the data, and prepared the main manuscript. E. Al-Dabis and M. Qairan contributed in collected data and samples, Y. Ghaleb and M. Al-Amad contributed to questionnaire design, data analysis and revising the draft, A. Al-serouri and A. Al-Kohlani contributed to final revising and final approval of the version to be submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Funding source

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee at the Ministry of Health and Population. Permission of the MoPHP was secured and verbal consent was given. Privacy was maintained during interviews, questionnaires kept in a lockable cabinet and data entered in a password-protected file in computer with specific entrance code.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge the TEPHINET and EMPHNET as well as the General Directorate of Surveillance and Disease Control at the Ministry of Public Health and Population for their support to the Y-FETP. The authors also thank all the medical, nursing, infection prevention, and laboratory teams at the COVID-19 isolation center.

References

- Alshaikhli H., Al-Naggar R.A., Al-Maktari L., Madram S., Al-Rashidi R.R. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in Yemen: a descriptive study. Int J Life Sci Pharma Res. 2020;10:134–138. [Google Scholar]

- CDC . CDC; 2020. Symptoms of coronavirus|.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html . [Accessed 12 May 2020] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . CDC; 2020. How coronavirus spreads|.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/how-covid-spreads.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fprepare%2Ftransmission.html [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Hao-Yuan, Jian Shu-Wan, Liu Ding-Ping. Contact tracing assessment of COVID-19 transmission dynamics in Taiwan and risk at different exposure periods before and after symptom onset. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1156–1163. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe Y.J., Park Y.J., Park O., Park S.Y., Kim Y.-M., Kim Y.-M. Contact Tracing during Coronavirus Disease Outbreak, South Korea, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:4. doi: 10.3201/eid2610.201315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2020;91:157. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörre A., Doblhammer G. The effect of gender on Covid-19 infections and mortality in Germany: insights from age- and sex-specific modelling of contact rates, infections, and deaths. MedRxiv. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.06.20207951. 10.06.20207951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecdc . 2020. Contact tracing: public health management of persons having had contact with novel coronavirus cases in the EU - 25 Feb 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EMPHNET . 2020. GHD|EMPHNET: COVID-19 Dashboard.http://emphnet.net/en/covid-19-response/dashboard/ . [Accessed 28 February 2021] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W., Ni Z., Yu Hu, Liang W., Ou C., He J. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J.-M., Bai P., He W., Wu F., Liu X.-F., Han D.-M. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front Public Heal. 2020;8:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadi H. Yemen is free of COVID-19. Int J Clin Virol. 2020 doi: 10.29328/journal.ijcv.1001012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (CoVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.Y. Pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and early immune-modulator therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18020388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo clinic . Mayo Clinic; 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) - symptoms and causes.https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/symptoms-causes/syc-20479963 . [Accessed 4 May 2020] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael T.M., Currie D.W., Clark S., Pogosjans S., Kay M., Schwartz N.G. Epidemiology of Covid-19 in a long-term care facility in king county, Washington. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2005–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merza M.A., Haleem Al Mezori A.A., Mohammed H.M., Abdulah D.M. COVID-19 outbreak in Iraqi Kurdistan: the first report characterizing epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological findings of the disease. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael D. Covid-19: four fifths of cases are asymptomatic, China figures indicate. BMJ. 2020;369:m1375. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng Y., Li Z., Chua Y.X., Chaw W.L., Zhao Z., Er B. Evaluation of the effectiveness of surveillance and containment measures for the first 100 patients with COVID-19 in Singapore — January 2–February 29, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:307–311. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Analytica Daily Brief . 2020. Yemeni conflict divisions will exacerbate virus impact.https://dailybrief.oxan.com/Analysis/ES252512/Yemeni-conflict-divisions-will-exacerbate-virus-impact [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier F., Spoorenberg T. Evaluation and analysis of age and sex structure. Reg Work Prod Popul Estim Demogr Indic. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Prompetchara E., Ketloy C., Palaga T. Immune responses in COVID-19 and potential vaccines: lessons learned from SARS and MERS epidemic. Asian Pacific J Allergy Immunol. 2020;38:1–9. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Cardona-Ospina J.A., Gutiérrez-Ocampo E., Villamizar-Peña R., Holguin-Rivera Y., Escalera-Antezana J.P. Clinical, laboratory and imaging features of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Liu M., Jia W.P., Wang S.S., Cao W.Z., Han K. Epidemic characteristics and trend analysis of the COVID-19 in Hubei province. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41 doi: 10.3760/CMA.J.CN112338-20200321-00409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Yixuan, Wang Yuyi, Chen Y., Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID‐19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020;92:568–576. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it . [Accessed 12 May 2020] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . WHO; 2020. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the mission briefing on COVID-19 2020.https://www.google.com/search?q=WHO.+WHO+Director-General%27s+opening+remarks+at+the+mission+briefing+on+COVID-19+2020+%5Bcited+2020+19+Feb%5D.+Available+from%3A+https%3A%2F%2Fwww.who.int%2Fdg%2Fspeeches%2Fdetail%2Fwho-director-general-s-opening-remarks-a . [Accessed 28 February 2021] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard.https://covid19.who.int/ . [Accessed 28 February 2021] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report-61; pp. 8–9.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331605 . [Accessed 25 April 2020]. 61. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Africa Region . 2020. COVID-19 Situation update for the WHO Africa Region, external situation report 18. [Google Scholar]