Abstract

The purpose of this project was to describe the implementation of a perinatal health fair intended to connect local women to holistic resources. Researchers used participatory strategies to develop the health fair with local women and perinatal educators. Researchers evaluated the health fair using pragmatic measures based on the (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) framework. Forty-two attendees were reached and 23 educators hosted booths and educational sessions. Feedback indicated strong enthusiasm for future similar events. Nearly three quarters of the time spent implementing the health fair was devoted to building relationships within the community. Overall, this project provides practical and empirical information to inform the planning, implementation, and evaluation of perinatal health fairs that establish meaningful connection between local women, perinatal educators, and health researchers.

Keywords: perinatal, health fair, implementation, RE-AIM

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy and parenthood alter nearly every aspect of a new parent's life (Fahey & Shenassa, 2013), leading to dynamic emotional, social, and physical shifts that can be overwhelming (Hall et al., 2018). Research indicates that over three quarters of pregnant women experience fears related to pregnancy and childbirth (Hanna-Leena Melender, 2003). In addition, women in the perinatal period struggle with daily barriers to well-being including physical changes and complications of pregnancy, conflicts in interpersonal relationships, and work-related challenges (Quintanilha et al., 2018).

Supporting women through these ongoing, fluctuating challenges is crucial because exposure to maternal psychological stress and anxiety has long-term ramifications for both the woman and child (Grigoriadis et al., 2018; Madigan et al., 2018). Social support may help prevent maternal stress (Racine et al., 2019), and many women in the perinatal period experience an intense longing for authentic human connection (Brady & Lalor, 2017). This desire for human connection may explain expectant parents' preference for face-to-face prenatal education (Kovala et al., 2016) that spans a wide range of topics about pregnancy and parenthood (Deave et al., 2008). However, there are significant gaps in perinatal support, as well as access to and awareness of that support (Deave et al., 2008; Guerra-Reyes et al., 2017; Tully et al., 2017).

To address women's social, emotional, and informational needs, a holistic and empowering approach to perinatal education is critical (Fahey & Shenassa, 2013). Regional research (deValpine et al., 2016; Harden et al., 2014; Harden et al., 2017) and direct feedback from local perinatal care providers demonstrate the ongoing difficulty in reaching expectant women in rural Virginia. A health fair is one untapped approach to address these difficulties by connecting parents with a variety of perinatal educators at one time in one place. Health fairs are “voluntary, community-based, cost-effective events” (Dillon & Sternas, 1997) that are designed to reach underserved populations (Murray et al., 2014), such as pregnant or postpartum women. The aim of health fairs is to increase awareness of health problems, promote healthy behaviors, and facilitate a sense of connection between local individuals and healthcare providers, thereby generating community empowerment (Dillon & Sternas, 1997; Ezeonwu & Berkowitz, 2014).

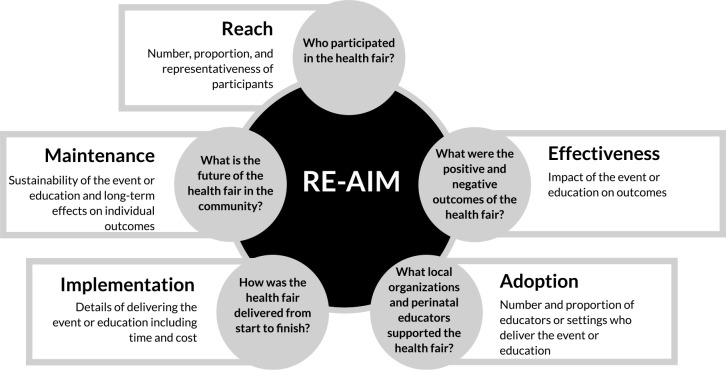

Evidence-based guidelines for implementing a health fair are rare (Goldman & Schmalz, 2004). There is a lack of practical guidance for actionable strategies to establish a fair and scant literature on robust methods for evaluating a fair (Escoffery et al., 2017). Therefore, researchers applied implementation science (Bauer et al., 2015) to plan and evaluate a health fair in Southwest Virginia. For planning, researchers leveraged participatory strategies and stakeholder engagement (Brady & Lalor, 2017; Estabrooks et al., 2019; Powell et al., 2015) as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) to improve local maternal health (WHO, 2014). For evaluation, researchers employed an implementation framework called RE-AIM, which was developed to translate research into meaningful community outcomes (Glasgow et al., 1999; Glasgow et al., 2019). RE-AIM stands for reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance and has been applied to a variety of community, clinical, and corporate settings in its 20-year history (Glasgow et al., 2019; Harden et al., 2018). It has not been applied to health fairs and may be a pragmatic tool for optimizing the delivery and evaluation of perinatal education.

In this paper, we employ RE-AIM to describe the implementation and effectiveness of a perinatal health fair. Findings include empirical outcomes, as well as actionable strategies that can be adapted for health fairs in other communities. In conducting this project, researchers strived to simultaneously serve their community and advance science.

METHODS

Context and Planning

Conducted in rural, Southwest Virginia, this project emerged from an integrated research-practice partnership (IRPP) (Estabrooks et al., 2019) focused on local maternal well-being. Perinatal research and projects related to the IRPP evolved over a decade (e.g., Harden et al., 2014, and Harden et al., 2017) and indicated significant gaps between women's perceived perinatal needs and their access to support services related to those needs.

To better understand local women's perceptions, a graduate research assistant (GRA) who was a registered yoga teacher offered free prenatal yoga classes (see Table 1). The prenatal yoga classes were a vehicle for engaging stakeholders and giving local women a voice in shaping the IRPP's projects. The GRA and members of the IRPP promoted the yoga classes through fliers and Facebook posts. The GRA taught the 75-minute yoga classes in a large, carpeted conference room at a local medical research center. Before class, yoga participants completed a Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire. Yoga mats, straps, and blocks were available for participants to use during each class.

TABLE 1. Timeline of Participatory Actions to Plan, Implement, and Evaluate the Event.

| Participatory action (approximate hours of GRA) | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gathering community input through prenatal yoga classes (64) | 16 | 16 | 20 | 12 | |||||

| Generating mom expo vision, intellectual/creative tasks (37) | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 6 | |||

| Recruiting educators (85) | 14 | 18 | 16 | 13 | 14 | 10 | |||

| Partnering and planning with local organizations (60) | 1 | 1 | 4 | 12 | 15 | 27 | |||

| Promoting event through social media and local TV/radio (22) | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| Hosting the event including facility preparation (16) | 16 | ||||||||

| Evaluating the event (8) | 8 | ||||||||

| Total time to plan, implement, and evaluate the event (292) | 292 | ||||||||

After class, the GRA facilitated informal discussions about participants' perinatal experiences. Notably, the GRA's role in the discussions was minimal with participants eagerly sharing stories, recommendations, and hardships. Within these discussions, participants initiated the idea of a one-day, family-friendly maternal health fair where individuals could interact with local health-care providers and perinatal educators without feeling as if they were part of a research study.

Given this input, the GRA applied her extensive team-building experience as a collegiate athletics coach to recruit local health-care providers (“educators”) to participate in the health fair (“mom expo”). The foundation of this recruiting was face-to-face networking and word-of-mouth recommendations, similar to the recruitment strategies employed by athletics coaches. Overall, the recruiting process emphasized developing interpersonal trust through conversations at local coffee shops, walk-and-talks at local parks, and informal conversations via telephone and text.

In addition to networking with individual educators, the GRA established partnerships with a local library to co-host the event and with an existing, family-focused local organization with 7,500 online followers. In conjunction with the local organizations, promotion for the mom expo included online articles, emails to the organization's followers, six television spots on local channels, one radio interview on a local station, Facebook posts, Instagram posts, and fliers posted at educators' workplaces in addition to local gyms, preschools, libraries, and OB/GYN offices.

Event Description

The mission of the mom expo was to empower, educate, and connect local women and their partners to resources related to pregnancy, birth, postpartum, and early parenthood. The mom expo occurred on Saturday, July 27, 2019, at a local library from 10 am to 4 pm. The mom expo was free to attend, but preregistration was available through a local organization's website. The kick-off event from 10 am to 10:45 am included a drum circle led by a certified music therapist. From 11 am to 4 pm, educators and local organizations hosted information tables in the auditorium. From 11 am to 3 pm, educators taught 30-minute seminars (see Table 2). From 3 pm to 4 pm, event managers administered educator surveys, thanked volunteers, and led facility clean-up.

TABLE 2. Seminar Characteristics and Attendance.

| Room 1–30-minute seminars | Room 2–30-minute seminars | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seminar title | Educator credential | Attendance N (%)a | Seminar title | Educator credential | Attendance N (%)a |

| “Exercise: Before and After Baby” | PhD, Exercise Physiology | 7 (17) | “Holistic Nutrition and Self-care for Women of Childbearing Age” | Master's, Applied Clinical Nutrition; Certified Massage Therapist | 7 (17) |

| “Pelvic Floor Exercises for Pregnancy and Postpartum” | PhD, Physical Therapy | 11 (24) | “Acupuncture and Reproductive Health: It is Possible to Not Dread Your Period” | Licensed Acupuncturist | 1 (2) |

| “Prenatal Care and Webster's Technique” | Doctor of Chiropractic | 9 (13.8) | “Mommy Mind” | PhD, Neuroscience | 16 (24.6) |

| “Fact of Fiction? Infant Feeding During the First Year of Life” | Registered Dietician | 4 (12.5) | “The 4th Trimester: The 10Bs and Who You Need on Your Support Team” | MD, Obstetrics/Gynecology | 14 (43.7) |

| “Self-Advocacy at Home, Work, and Your Doctor's Office” | Lawyer | 9 (31) | “Myth-busting and why Dads and Birth Partners Love Doulas” | Certified Midwife and Doula | 3 (10.3) |

| “Private Parts: A Practical Look at Body Autonomy” | Registered Nurse | 12 (46) | “Keeping Kids Safe” | Safe Kids Health Educator and Coalition Coordinator | 0 (0) |

| “Music for Labor Through the Early Years” | Licensed Musical Therapist | 4 (14.8) | “Breastfeeding Q&A: Tips and Local Resources” | Certified Lactation Counselor | 3 (11.5) |

| “Pain Coping for Labor” | Certified Doula | 3 (12.5) | “Practical Mealtime Tips for New Parents” | Cooperative Extension Agent | 2 (8) |

Percent of individuals based on total individuals counted in room 1, room 2, and the auditorium where educators hosted tables.

Data Collection and Evaluation

To evaluate the mom expo and fulfill the women's requests to avoid feeling studied, researchers employed pragmatic measures (Glasgow, 2013) guided by the RE-AIM framework (Glasgow et al., 1999). See Figure 1. For reach, undergraduate and GRAs used an observational protocol to document the number of attendees at the mom expo. For effectiveness, anonymous comment cards with a 1–10 visual analog and open space for writing feedback were available to mom expo attendees throughout the day of the event. Two researchers independently reviewed the comment cards to identify emergent themes through a rapid analysis approach (Taylor et al., 2018). For additional measures of effectiveness, educators received a paper-and-pencil survey (“educator survey”) to report their perception of the event's success in empowering, connecting, and educating attendees. For adoption, the GRA maintained qualitative descriptions of educators and organizations who agreed to participate. For implementation, the GRA maintained fidelity checklists, a timeline, and expense reports. In addition, the educator survey included measures of educators' perceptions of the event's implementation including facility, location, publicity, atmosphere/energy, planning/organization leading up to the event, management on the day of the event, overall experience, and suggestions for improvements. For maintenance, the educator survey included one item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not likely, 5 = very likely): “How likely are you to participate in Mom Expo next year?”

Figure 1. Applying the RE-AIM framework to a perinatal health fair.

Notably, data collection and evaluation were intended to fit seamlessly within the mom expo to avoid disrupting attendees' and/or educators' experience. Likewise, data collection did not include sensitive information. This project was Institutional Review Board exempt.

RESULTS

In this section, authors present results for each RE-AIM dimension. For reach, 116 community members preregistered for the mom expo, and 42 individuals attended the event (see Table 2). Of those 42, 25 (59.5%) preregistered and the remaining 17 (40.5%) were walk-ins. There are multiple appropriate denominators for determining the proportion of the targeted population that attended. Using the approximate membership (7,500) of the family-oriented organization who spearheaded online promotions, the reach proportion was .0056. Using the 2018 number of live births of the surrounding city and county (3,155), the reach proportion was .013 (Virginia Department of Health, 2019). Finally, using the approximate number of prenatal patients (400) in local OBGYN clinics, the reach proportion was .11. In terms of relative reach, the mom expo drew many more participants than two free maternal health events hosted by other organizations in the same summer. The other events reached 3 and 12 local women, respectively.

In terms of effectiveness, 14 attendees (33.3%) submitted voluntary comment cards, and the mean experience rating on the comment cards was 9.5 out 10. Emergent themes from written feedback on the comment cards were positive experience (n = 8), interest in sustainability (n = 4), and suggested improvements (n = 4) (see Table 3). In addition, 21 educators (91.3%) submitted surveys and rated the mom expo as above average in providing attendees opportunity for education (4.76 out of 5), empowerment (4.71 out of 5), and connection (4.75 out of 5). In terms of adoption, 23 educators, 7 maternal-related organization representatives, and 7 volunteers participated in the event in addition to the 3 event managers. For implementation, the GRA spent approximately 289 hours planning, implementing, and evaluating the mom expo (see Table 1). The GRA dedicated nearly three quarters (72.3%) of those hours to direct interactions with community members via face-to-face conversations and phone calls. Excluding person-hours, the implementation cost of the mom expo was $1,003.44, including T-shirts, promotional materials, and food on the day of the event. The library cohosting the mom expo waived the rental fee, and all educators and organizations volunteered their time. Educators rated the planning/organization leading up to the event as excellent (5.0 out of 5) and the management on the day of the event as above average (4.95 out of 5). Successful implementation required ongoing problem-solving (see Table 4). In terms of maintenance, 100% of the educators who completed surveys indicated that they are very likely (18) or likely (3) to participate in the mom expo next year. In addition, attendees and educators who convened at the mom expo developed Huddle Up Moms (HUM), a nonprofit organization hosting events and developing support groups. Efforts of HUM continue to echo the mom expo mission of empowerment, education, and connection.

TABLE 3. Mom Expo Effectiveness: Comment Card Feedback from Attendees.

| Emergent theme | Positive experience (8) | Interest in sustainability (4) | Suggested improvements (4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Examples of feedback |

|

|

|

TABLE 4. Problems and Solutions to Hosting a Maternal Heal Fair.

| Potential problem | Potential solution |

|---|---|

| Trademark of event name |

|

| Security at event |

|

| Facility comfort on day of event |

|

| Breastfeeding needs |

|

| Overwhelming emails related to event organization |

|

| Nerves and confusion among event staff |

|

| Last-minute absences of educators |

|

| Last-minute absences of event managers |

|

| Unannounced media presence |

|

| Stroller accessibility |

|

| Issues with signs, equipment, or technology |

|

| Refreshments |

|

| Commercialization versus empowerment, connection, and education |

|

| Lack of inclusivity |

|

DISCUSSION

Based on the positive feedback from attendees and educators, the mom expo was perceived as an effective vehicle for empowerment, education, and connection. The mom expo reached 3–20 times more participants than other free perinatal health events that summer, and the proportion of pre-registered individuals (22%) who attended the mom expo aligned with other events promoted by the family-orientated organization. However, the reach still fell below the IRPP's aspirations. This difficulty reaching pregnant and postpartum women reflects results of other perinatal research conducted in this rural area (deValpine et al., 2016) and may require novel approaches beyond generalities described in current literature (Dillon & Sternas, 1997; Escoffery et al., 2017; Goldman & Schmalz, 2004; Murray et al., 2014). For example, one attendee suggested on a comment card that participants who attended this first mom expo could become “mom ambassadors” in promoting the event to individuals they know. Another novel, untested strategy for improving reach could be to generate connection between individuals who preregister for the event before the event. This preevent connection could include personalized reminders, phone calls, emails, and social media interactions, as well as individualized invitations to participate in “ask anything” sessions with educators or even preevent prize drawings in which prizes are announced and drawn before the event but must be retrieved at the event itself.

Overall, this project demonstrates the power of taking time to build meaningful relationships between researchers and perinatal educators within the community. Recruiting educators and building trust was time and energy intensive; however, investing this socio-emotional energy in relationship building ended up saving money and facilitating promotions. For example, after weeks of interactions, a library administrator offered to waive the rental fee of over $800, and a prenatal yoga attendee arranged promotional airtime on a local television channel. Beyond cost savings, the power of meaningful relationships is evident in the high adoption among educators and volunteers. Furthermore, educators, volunteers, and women who met each other through the mom expo are now establishing a non-profit organization as a long-term, sustainable, local hub for holistic perinatal education, support, and connection.

Building relationships within participatory projects is an iterative, emotionally demanding process that belies typical empirical procedures and scientific skills (Oliver et al., 2019). Findings from this mom expo support the following actionable strategies related to building authentic relationships and partnerships between researchers, perinatal educators, and local women: First, members of a participatory project should carefully choose their roles based on each member's individual skills and capacities (Stoecker, 1999). For example, the GRA tasked with bringing individuals together for the mom expo had 15 years of team-building experience as an athletics coach. Second, members of a participatory project—including members who do not have networking roles—should account for relationship building and local networking in research protocols, timelines, discussions, and so on, so that this pivotal aspect of community-based projects does not remain invisible. Third, to manage conflicting academic and community workloads, members of a participatory project can “batch” their responsibilities by focusing on one type of work in a single block of time (Newport, 2016). For example, the GRA scheduled several email and phone “blackout times” per week so that she could finish her academic/intellectual work without the social “interruptions” that come with extensive relationship building. Fourth, when actually doing the relationship building, members of a participatory project should initiate contact in-person or via telephone (not email); spend more time listening than speaking; meet in nonresearch settings like coffee shops or parks; match their word choice, body language, and clothing to the meeting setting; offer appealing, free group activities—like prenatal yoga—as natural opportunities to spend meaningful time with community members; and intentionally shift one's mindset from expertise and productivity to empathy and presence.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations of this project. First, reach did not include sociodemographic or health information, and effectiveness did not include behavioral or physiological measures. When selecting pragmatic measures, researchers intentionally prioritized the women's requests to avoid feeling as if they were in a study over scientific paradigms of more rigorous empirical methods. Second, measuring GRA hours was complicated by overlapping tasks and the spontaneous, unpredictable nature of building relationships within a participatory project. This type of community-driven work does not fit neatly into traditional scientific paradigms of a priori protocols, linear processes, and objective, measurable outcomes (Oliver et al., 2019; Stoecker, 1999). Third, one intended pragmatic measure—using Live- Poll to gather demographics and perceptions of participants at the mom expo—failed due to technological issues, further limiting data related to attendee characteristics and experience. Future projects could leverage interactive technology, such as LivePoll, to facilitate interpersonal connection and data collection at perinatal health fairs. Future projects could also use RE-AIM in the planning stages, not just the evaluation stages.

Implications for Practice

Despite these limitations, this participatory project is significant as a practically feasible and empirically sound example of bridging the gap between rural women and holistic perinatal support. This promising process can be replicated in other communities in which perinatal educators and researchers establish partnerships to launch community events planned and evaluated through the RE-AIM framework. The key to replication will be devoting considerable time and energy to engaging stakeholders through authentic relationship building. In this way, a perinatal health fair may be a vehicle for lasting interpersonal connections that nurture holistic well-being and community change beyond the research itself.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the educators, organizations, and volunteers who enthusiastically collaborated to plan and implement the mom expo. As well, we thank the Translational Obesity Research Interdisciplinary Graduate Education Program for the yoga practice supplies.

Biographies

ABBY STEKETEE is an adjunct instructor in Virginia Tech's Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise. Her areas of research and practice include implementation science, participatory research, novel qualitative methods, yoga, physical activity, and flourishing. She spent 15 years as an NCAA Division I Swimming and Diving coach and is a certified yoga teacher.

SAMANTHA HARDEN is an associate professor in Virginia Tech's Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise as well as the Department of Obstetrics/Gynecology in Virginia Tech's Carilion School of Medicine. She is an expert in group-based physical activity, implementation science, yoga, and the RE-AIM framework. In addition, she has completed her 500-hour yoga teacher training (RYT-500).

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no relevant financial interest or affiliations with any commercial interests related to the subjects discussed within this article.

FUNDING

The author(s) received no specific grant or financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- Bauer, M. S., Damschroder, L., Hagedorn, H., Smith, J., & Kilbourne, A. M. (2015). An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychology, 3(1), 1–12. 10.1186/S40359-015-0089-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady, V., & Lalor, J. (2017). Space for human connection in antenatal education: Uncovering women's hopes using participatory action research. Midwifery, 55, 7–14. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deave, T., Johnson, D., & Ingram, J. (2008). Transition to parenthood: The needs of parents in pregnancy and early parenthood. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 8, 1–11. 10.1186/1471-2393-8-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deValpine, M. G., Jones, M., Carpenter, D. B., & Falk, J. (2016). First trimester prenatal care and local obstetrical delivery options for women in poverty in rural virginia. Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing, 02(04), 1–8. 10.4172/2471-9846.1000137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, D. L., & Sternas, K. (1997). Designing a successful health fair to promote individual, family, and community health. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 14(1), 1–14. 10.1207/s15327655jchn1401_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoffery, C., Liang, S., Rodgers, K., Haardoerfer, R., Hennessy, G., Gilbertson, K., Heredia, N. I., Gatus, L. A., & Fernandez, M. E. (2017). Process evaluation of health fairs promoting cancer screenings. BMC Cancer, 17(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s12885-017-3867-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks, P. A., Harden, S. M., Almeida, F. A., Hill, J. L., Johnson, S. B., Porter, G. C., & Greenawald, M. H. (2019). Using integrated research-practice partnerships to move evidence-based principles into practice. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 47(3), 176–187. 10.1249/JES.0000000000000194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezeonwu, M., & Berkowitz, B. (2014). A collaborative communitywide health fair: The process and impacts on the community. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 31(2), 118–129. 10.1080/07370016.2014.901092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahey, J. O., & Shenassa, E. (2013). Understanding and meeting the needs of women in the postpartum period: The perinatal maternal health promotion model. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health, 58(6), 613–621. 10.1111/jmwh.12139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow, R. (2013). What does it mean to be pragmatic? Pragmatic methods, measures, and models to facilitate research translation. Health Education and Behavior, 40(3), 257–265. 10.1177/1090198113486805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow, R. D., Vogt, T. M., & Boles, S. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1322–1327. 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow, R. E., Harden, S. M., Gaglio, B., Rabin, B., Smith, M. L., Porter, G. C., Ory, M. G., & Estabrooks, P. A. (2019). RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 64. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, K. D., & Schmalz, K. J. (2004). Top grade health fair An “A” fair to remember. Health Promotion Practice, 5(3), 217–221. 10.1177/1524839904264663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriadis, S., Graves, L., Peer, M., Mamisashvili, L., Tomlinson, G., Vigod, S., Dennis, C. L., Steiner, M., Brown, C., Cheung, A., Dawson, H., Rector, N. A., Guenette, M., & Richter, M. (2018). Maternal anxiety during pregnancy and the association with adverse perinatal outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(5), 17r12011. 10.4088/JCP.17r12011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Reyes, L., Christie, V. M., Prabhakar, A., & Siek, K. A. (2017). Mind the gap: Assessing the disconnect between postpartum health information desired and health information received. Women's Health Issues, 27(2), 167–173. 10.1016/j.whi.2016.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P. J., Foster, J. W., Yount, K. M., & Jennings, B. M. (2018). Keeping it together and falling apart: Women's dynamic experience of birth. Midwifery, 58, 130–136. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna-Leena Melender, R. (2003). Experiences of fears associated with pregnancy and childbirth: A study of 329 pregnant women. Birth, 29(2), 101–111. 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00170.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden, S., Beauchamp, M., Pitts, B., Nault, E., Davy, B., You, W., Weiss, P., & Estabrooks, P. (2014). Group-based lifestyle sessions for gestational weight gain management: A mixed method approach. American Journal of Health Behavior, 38(4), 560–569. 10.5993/AJHB.38.4.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden, S. M., Ramalingam, N. P. S., Wilson, K. E., & Evans-Hoeker, E. (2017). Informing the development and uptake of a weight management intervention for preconception: A mixed-methods investigation of patient and provider perceptions. BMC Obesity, 4(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s40608-017-0144-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden, S. M., Smith, M. L., Ory, M. G., Smith-Ray, R. L., Estabrooks, P. A., & Glasgow, R. E. (2018). RE-AIM in clinical, community, and corporate settings: Perspectives, strategies, and recommendations to enhance public health impact. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 1–10. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovala, S., Cramp, A. G., & Xia, L. (2016). Prenatal education: Program content and preferred delivery method from the perspective of the expectant parents. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 25(4), 232–241. 10.1891/1058-1243.25.4.232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan, S., Oatley, H., Racine, N., Fearon, P., Schumacher, L., Akbari, E., Cooke, J. E., & Tarabulsy, G. (2018). A meta-analysis of maternal prenatal depression and anxiety on child socioemotional development. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(9), 645–657. 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, K., Liang, A., Barnack-Tavlaris, J., & Navarro, A. M. (2014). The reach and rationale for community health fairs. Journal of Cancer Education, 29(1), 19–24. 10.1007/s13187-013-0528-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport, C. (2016). Deep work. Grand Central Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, K., Kothari, A., & Mays, N. (2019). The dark side of coproduction: Do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research? Health Research Policy and Systems, 17(1), 1–10. 10.1186/s12961-019-0432-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell, B. J., Waltz, T. J., Chinman, M. J., Damschroder, L. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M., Proctor, E. K., & Kirchner, J. A. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(1), 1–14. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintanilha, M., Mayan, M. J., Raine, K. D., & Bell, R. C. (2018). Nurturing maternal health in the midst of difficult life circumstances: A qualitative study of women and providers connected to a community-based perinatal program. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s12884-018-1951-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine, N., Plamondon, A., Hentges, R., Tough, S., & Madigan, S. (2019). Dynamic and bidirectional associations between maternal stress, anxiety, and social support: The critical role of partner and family support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 252, 19–24. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecker, R. (1999). Are academics irrelevant. American Behavioral Scientist, 42(5), 840–854. 10.1177/00027649921954561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, B., Henshall, C., Kenyon, S., Litchfield, I., & Greenfield, S. (2018). Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open, 8(10), e019993. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully, K. P., Stuebe, A. M., & Verbiest, S. B. (2017). The fourth trimester: A critical transition period with unmet maternal health needs. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(1), 37–41. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Department of Health. (2019). Total live births by place of occurrence and place of residence by race. https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/HealthStats/stats.htm

- World Health Organization. (2014). WHO recommendations on community mobilization through facilitated participatory learning and action cycles with women's groups for maternal and newborn health. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/community-mobilization-maternal-newborn/en/ [PubMed]