Abstract

Maternal morbidity and mortality continue to rise in the United States, with cardiovascular disease as the leading cause of maternal deaths. Congenital heart disease is now the most common cardiovascular condition encountered during pregnancy, and its prevalence will continue to grow. In tandem with these trends, maternal cardiovascular health is becoming increasingly complex. The identification of women at highest risk for cardiovascular complications is essential, and a team-based approach is recommended to optimize maternal and fetal outcomes. This document, the second of a five-part series, will provide practical guidance from preconception through postpartum for cardiovascular conditions that are predominantly congenital or heritable in nature, including aortopathies, congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, and valvular heart disease.

Keywords: cardio-obstetrics, pregnancy, congenital, aortopathy, pulmonary hypertension

Condensed Abstract

Congenital heart disease is now the most common cardiovascular condition encountered during pregnancy, and its prevalence will continue to grow. The identification of women at highest risk for cardiovascular complications is essential, and a team-based approach is recommended to optimize maternal and fetal outcomes. This document, the second of a five-part series, will provide practical guidance from preconception through postpartum for cardiovascular conditions that are predominantly congenital or heritable in nature, including aortopathies, congenital heart disease, pulmonary hypertension, and valvular heart disease.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States. (1) Contributing factors include increases in the number of first births to older women and increased prevalence of underlying cardiovascular risk factors in pregnant women.(1) Medical and surgical management of pediatric heart disease now permit survival of most women born with congenital heart disease (CHD) to reproductive age and beyond.(2) This document serves as a practical guide from preconception through postpartum for the management of pregnant women with cardiovascular conditions predominantly congenital or heritable in nature, namely aortopathies, CHD, pulmonary hypertension, and valvular heart disease.

Cardio-Obstetrics Team and Risk Stratification

Pregnancy may be poorly tolerated by women with congenital or heritable cardiovascular conditions. Due to the wide heterogeneity in cardiovascular risk associated with pregnancy, preconceptual risk stratification and counseling according to the risk models discussed in Part 1 of this series should begin in adolescence and continue into adulthood.(3) A multidisciplinary cardio-obstetrics team should ideally evaluate the patient before conception, optimize her cardiac status prior to pregnancy when needed, and follow her through the pregnancy and postpartum period. Members of the cardio-obstetrics team will vary based on the complexity of the patient’s underlying cardiac condition, but women with modified World Health Organization (mWHO) Class III and IV conditions require a cardio-obstetrics team experienced in the management of complex cardiac disease in pregnancy (See Part 1).(3,4)

Aortopathy

Pregnancy can result in weakening of the aortic media, increased aortic diameter and heightened risk of aortic dissection in pregnancy and the postpartum period.(5) Aortic complications occur most commonly in the third trimester or postpartum, and risk is further increased in the presence of concomitant hypertension.(6) Aortic dissection is associated with high maternal and fetal mortality (8.6% and 50% respectively), and requires prompt diagnosis and treatment.(7)

Preconception Evaluation

Patients at risk for aortic aneurysms (Table 1) should be evaluated with echocardiogram and CT/MRI within one year prior to conception to evaluate for aortic valve disease and aortic dimensions. In those with aortic root dilatation exceeding certain diametric thresholds (Table 1), consider prophylactic surgery prior to pregnancy. The majority of pregnancy-related aortic complications occur in patients with a family but not a personal history of aortopathy.(8) Thus, risk screening and genetic counseling is recommended as a part of the preconception evaluation for women with a first or second-degree relative with aortopathy, given the heritability of these disorders.

Table 1.

Pregnancy Management for Women with Aortopathy

| Condition | mWHO Class | Preconception Surgery | Cesarean Delivery | Imaging Frequency | Heritability | Disease Specific Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bicuspid AV | II: AVA >1 cm2 and peak gradient <50 mmHg, Aortic root <45 mm | >50 mm | >50 mm | At least once if normal aortic dimension | 9% | Aortic dilatation may worsen aortic regurgitation |

| III: Aortic root 45–50 mm IV: AVA <1cm2 or peak gradient >50 mmHg or Aortic root >50 mm | Every Trimester if >40 mm | Fetal echocardiogram recommended 2nd trimester | ||||

| Turner Syndrome | II-III: Aortic root <20 mm/m2 with associated risk factors or <25 mm/m2 without associated risk factors | >25 mm/m2 or >20 mm/m2 with associated risk factors for aortic dissection | >20 mm/m2 | At least once if normal aortic dimension | 5% CHD | Risk for pregnancy loss, preeclampsia, and ~2% risk of dissection |

| IV: Aortic root >20 mm/m2 with associated risk factors or >25 mm/m2 without associated risk factors | Every 4–8 weeks if dilated aorta | Pregnancy risk higher for women with structural heart disease and hypertension | ||||

| Marfan Syndrome | III: Aortic root <45 mm, mod-severe AI | >40–45 mm | >40 mm | Every 4–8 weeks if >40 mm | 50% | Dissection risk ~10% if aortic root >40 mm, ≤1% if aortic root <40 mm; more recent studies suggest up to 4.5 cm may be safe |

| IV: Aortic root >45 mm, history of dissection | Moderate-severe aortic regurgitation Rapid dilatation (>2–3 mm/year) | History of Aortic Dissection | Every trimester if <40 mm | Pregnancy discouraged if high risk features: personal or family history of dissection, rapid dilation rate | ||

| Vascular Ehlers-Danlos | IV | No wellestablished guidelines, >40 mm reasonable | All - to reduce risk of obstetric complications | Every 4–8 weeks | 50% | Mortality 5.3%, life threatening complications in 14.5% - Pregnancy should be avoided Significant obstetric morbidity - uterine rupture, premature rupture of membranes with preterm delivery, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, and severe perineal tears Delivery recommended by 36–38 weeks |

| Loeys-Dietz | III: Aortic diameter <40 mm | >42 mm by TEE or >4446 mm by CT or MRA | >40 mm | Every 4–8 weeks | 50% | Preconception comprehensive MRA/CTA of brain, pelvis, thorax, and abdomen recommended |

| IV: Aortic diameter >40 mm | *No diameter is truly safe | More aggressive vascular course than Marfan Syndrome - dissection may occur in absence of aneurysm | ||||

| Familial Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections | III: Aortic diameter <40 mm | Every trimester if <40 mm | Variable | Dissection may occur with minimal aortic dilatation | ||

| IV: Aortic diameter >40 mm | Every 4–8 weeks if >40 mm | Dissection may occur in descending aorta after replacement of ascending aorta | ||||

While each patient requires individualized management, this table provides general disease-specific recommendation for the management of women with heritable aortopathy.

mWHO – modified World Health Organization. AV – aortic valve. AVA – aortic valve area. CHD – congenital heart disease. AI – aortic insufficiency. CTA – computed tomography angiography. MRA – magnetic resonance angiography.

Pregnancy Management

Women with aortopathy syndromes require a multidisciplinary team with expertise in the management of aortic disease during pregnancy. Current guidelines recommend serial aortic imaging throughout pregnancy until 6 months postpartum by echo or non-contrast magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).(9) Blood pressure management during pregnancy to prevent stage II hypertension (140/90) is recommended; consideration should be given to beta-blockade during pregnancy.(9) Rapid aortic root expansion during pregnancy (> 5mm) should prompt discussion of therapeutic options, including pregnancy termination versus aortic repair with the fetus in utero prior to viability. When the fetus is viable, Caesarean delivery in a tertiary cardiothoracic center, followed directly by aortic surgery is recommended. The safest period to undertake semi-elective surgery is during the second trimester. (5) Disease-specific management of heritable aortopathies is summarized in Table 2. (10–18)

Table 2.

Pregnancy Management for Women with Congenital Heart Disease

| CHD Lesion | WHO Class | Potential Complications | Monitoring Considerations | Management Considerations | Anesthesia Considerations | Delivery Considerations | Postpartum Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shunt Lesions (ASD, VSD, PDA) |

|||||||

| Repaired | I | Arrhythmias | Baseline Echo | After initial cardiology consultation, may be managed at nonspecialized center | Consider epidural | Vaginal Preferred | Low risk for complications |

| Unrepaired Qp:Qs < 1.5 | II | Arrhythmias, Heart Failure, Paradoxical Embolism | Baseline and 28–32 week echocardiogram | Consideration of aspirin 81 mg or prophylactic enoxaparin for paradoxical embolism prevention | Potential to transiently reverse shunt with systemic hypotension Filtered IV lines Consider epidural | Vaginal preferred | Small risk of right heart failure; risk ofparadoxical embolism |

| Unrepaired Qp:Qs > 1.5 | II | Arrhythmias, Heart Failure, Paradoxical Embolism | Consider serial echo to monitor ventricular function and pulmonary pressures | Consideration of aspirin 81 mg or prophylactic enoxaparin for paradoxical embolism prevention | Preload dependent if RV enlargement/dysfunction Potential to transiently reverse shunt with systemic hypotension Filtered IV lines Epidural recommended | Vaginal preferred unless severe pulmonary hypertension | Risk of right heart failure and paradoxical embolism |

|

Systemic Right Ventricle |

|||||||

| D-TGA with atrial switch, L-TGA | III | Atrial arrhythmias (15%), heart failure (10%), worsening tricuspid regurgitation, premature delivery (33%), accelerated decline in systemic ventricular function | Baseline and 28–32 week echocardiogram | Requires CHD cardiologist and MFM | Epidural recommended - slow titration if significant systemic ventricular dysfunction | Vaginal preferred unless acute decompensated heart failure | Risk of postpartum heart failure - consider extended postpartum monitoring 48–72 hours |

| Holter/Event monitoring for palpitations | Continue heart failure therapies with pregnancy-safe medications Continue arrhythmia management with pregnancy-safe medications | Consider telemetry monitoring | Delivery in specialized CHD/Cardio-obstetrics care center | Early postpartum outpatient follow up | |||

| D-TGA with arterial switch | II-III | Arrhythmias (2.5–7%), heart failure (2.5–21%) | Baseline echo Consider baseline ischemic evaluation if any chest pain symptoms Consider 28–32 week echo if significant PI, AI or ventricular dysfunction | Recommend CHD cardiologist, MFM management | Consider epidural Consider telemetry monitoring | Vaginal preferred | Low risk of postpartum arrhythmias or heart failure |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | II | Arrhythmias (2–6%), heart failure (2%), progressive right heart failure/dysfunction | Baseline echo to evaluate pulmonary valve and right ventricular function | Recommend CHD cardiologist and MFM management | Epidural recommended - slow titration if significant right ventricular dysfunction | Vaginal preferred | Risk of right heart failure if significant pulmonary valve or right heart dysfunction |

| *Risk higher for women requiring cardiac medications prior to pregnancy, ≥moderate pulmonary regurgitation, or severe RV dilation | Consider 28–32 weeks echocardiogram if significant pulmonary valve or right ventricular dysfunction | Consider genetics consultation given increased risk of fetal transmission of conotruncal defects If asymptomatic and good functional capacity, preconception PVR not required unless otherwise meeting indication | Consider telemetry monitoring | ||||

| Coarctation of the Aorta | II-III | Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (30%), aortic dissection if aneurysm present | Baseline MRA | Consider aspirin 81 mg daily beginning in the second trimester given increased risk of preeclampsia | Epidural recommended | Vaginal generally preferred | High risk of postpartum hypertension - blood pressure expected to peak between days 3–8 after delivery |

| *Increased risk for complications if any of the following: residual obstruction (gradient >20 mmHg, minimal aortic lumen <12 mm), hypertension, aortic aneurysm | Consider serial non-contrast MRA if aortic diameter >4.0 cm | Close monitoring of blood pressure with individualized blood pressure goals, considering risk of cerebral hypertension and fetal hypoperfusion in the setting of underlying residual coarctation | Consider Cesarean delivery if ascending aortic aneurysm >5.0 cm or acute aortic syndrome | ||||

| Baseline echo to evaluate for bicuspid aortic valve | Repair residual/recurrent coarctation prior to pregnancy if possible | ||||||

| Baseline MRA brain to evaluate for berry aneurysms | Consider repair of aortic aneurysm >5.0 cm prior to pregnancy | ||||||

| Severe unrepaired coarctation | IV | Coarctation should be repaired prior to proceeding with pregnancy | |||||

| Single Ventricle Physiology | III | Atrial arrhythmias, heart failure, thromboembolism, fetal loss, growth restriction, preterm birth | Baseline echocardiogram, preconception exercise test. | Requires coordinated care by CHD cardiologist and MFM | Epidural is recommended - slow titration due to preload dependent circulation | Vaginal preferred | Remains at risk of heart failure and thromboembolism |

| IV - evidence of Fontan failure, clinically significant cirrhosis, baseline hypoxemia, poor functional class | Live birth rate only 45% if evidence of Fontan failure | Consider 28–32 weeks echocardiogram | Continue heart failure therapies with pregnancy-safe medications | IV filters required if Fontan fenestration or significant venovenous collaterals | Labor in left lateral decubitus position due to preload dependence | ||

| Baseline labs - liver function tests, renal function tests, liver imaging, pulse oximetry | Continue arrhythmia management with pregnancy-safe medications | Consider low threshold for assisted second stage to reduce duration of Valsalva | |||||

| Consider preconception cardiopulmonary stress test to assess functional capacity Consider baseline endoscopy if evidence of portal hypertension; consider repeating second trimester if evidence of varices | Consider low dose aspirin, prophylactic, or therapeutic anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolism, depending on type of palliation, degree of cyanosis, and history of thromboembolism | Maintain adequate hydration and treat hypotension or hemorrhage with immediate fluid resuscitation | |||||

While each patient requires individualized management, this table provides general disease-specific recommendation for the management of women with congenital heart disease.

CHD – congenital heart disease. WHO – World Health Organization. ASD – atrial septal defect. VSD – ventricular septal defect. PDA – patent ductus arteriosus. IV – intravenous. RV – right ventricle. TGA – transposition of the great arteries. MFM – maternal fetal medicine. PI – pulmonary insufficiency. PVR – pulmonary valve replacement. MRA – magnetic resonance angiography.

A documented delivery plan should be widely distributed to all health care team members with consideration for delivery at term given the maternal risks of pregnancy continuation versus small additional fetal benefit. Most women may be delivered vaginally with consideration for an assisted second stage in the event of prolonged pushing, though Cesarean delivery may be safer for high-risk women (Table 2). Delivery is recommended at a hospital where cardiothoracic surgery is available.(9)

Emergency Management

Non-contrast MRA or contrast-enhanced computed tomography angiography (CTA) should be performed immediately upon suspicion of aortic dissection. Emergency surgery should be undertaken regardless of trimester for acute type A aortic dissections. In women with a viable fetus, Caesarean delivery should be performed immediately before the aortic repair, given the fetal risks associated with cardiopulmonary bypass. Type B aortic dissections are usually managed medically unless there are end-organ complications, in which case endovascular strategies should be considered. Gravid or postpartum patients should be managed in a tertiary care center specializing in management of aortic complications.

Congenital Heart Disease

The risk of severe maternal morbidity or mortality depends on the type of CHD, severity of residual lesions and ventricular function.(19) Mortality in the Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) CHD population was 0.2%, with heart failure occurring in 13% of patients with complex CHD and in 5% with simple to moderate CHD.(19) Women with complex CHD are also at increased risk of obstetric and fetal complications, including postpartum hemorrhage, spontaneous pre-term birth, and small for gestation age babies.(20,21) Individual pre-conception risk stratification is thus essential for counseling and managing patients during their childbearing years.(2)

Preconception Evaluation

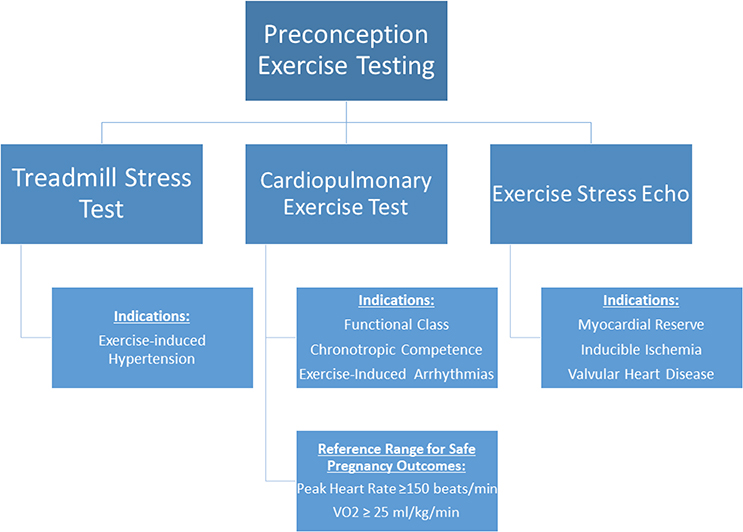

Discussions regarding contraception and pregnancy should begin in pediatric cardiology clinics and continue after transition to adult CHD care.(3,22) Residual or progressive lesions are common, and preconception imaging is important for identifying high-risk lesions, such as pulmonary hypertension, severe left-sided obstructive valve disease, systemic ventricular dysfunction, or aortic dilation.(23) When possible, high-risk lesions should be treated prior to conception.(23) Preconception exercise testing can help with risk stratification, particularly in patients with current or recovered ventricular dysfunction or valve disease (Figure 1).(3,23,24) Referral to a geneticist for risk assessment is appropriate for women with high risk for fetal transmission of cardiovascular disease or a strong family history of CHD.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for preconception stress testing for women with CHD. Preconception exercise testing may be considered for risk stratification, in particular for women with congenital or valvular conditions. VO2 – Maximum oxygen consumption.

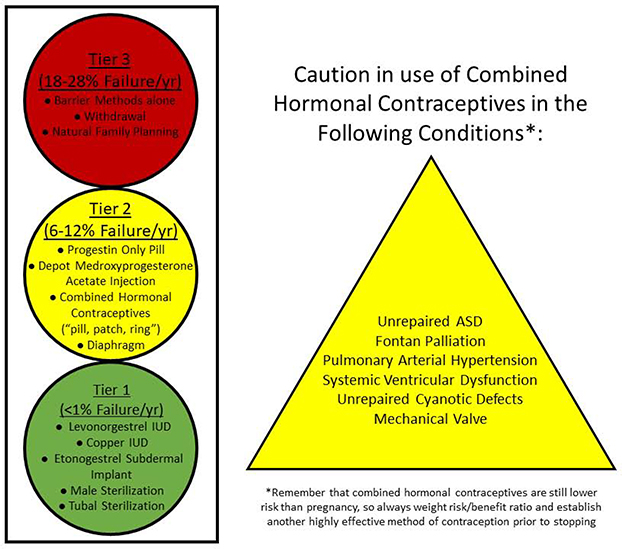

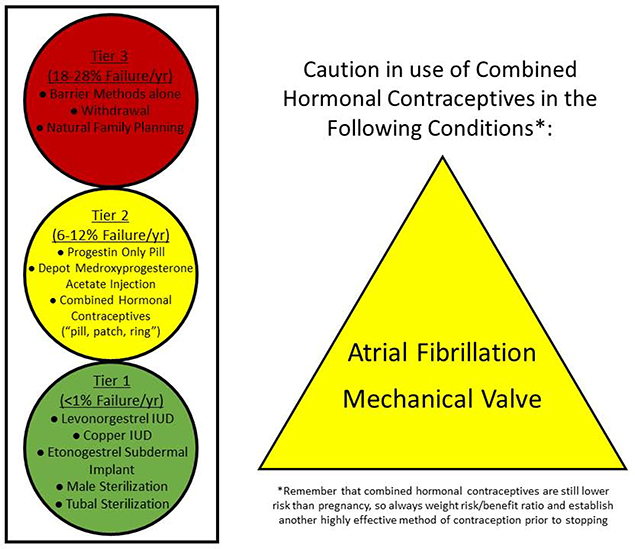

Contraception

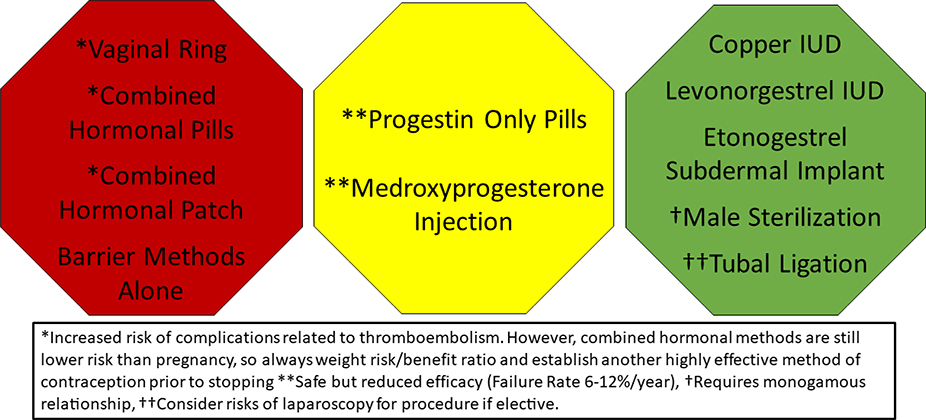

Contraception is discussed in detail in the fifth part of this manuscript series. Long-acting reversible methods of contraception are safe for women with all forms of CHD.(25) Combined hormonal contraceptives are considered contraindicated in patients with CHD at high risk for thromboembolism and those with prosthetic valves, and alternate methods of contraception should be considered (Figure 2).(26)

Figure 2. Safety and Efficacy of Contraceptives in Women with CHD.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (the IUD and subdermal implant) and permanent sterilization are safe and highly effective for all women with CHD. Caution should be advised when prescribing combined hormonal contraceptives to women with certain CHD conditions due to the increased risk of thromboembolism. ASD – Atrial septal defect.

Fetal Screening

The risk of CHD in a child born to a parent with non-syndromic CHD is approximately 3–5%, compared to 1% in the general population.(27) Certain cardiac defects are associated with higher rates of fetal transmission. A dedicated fetal echocardiogram should be performed between gestational weeks 18–22 when either parent has a history of CHD.(3,27)

Pregnancy Management

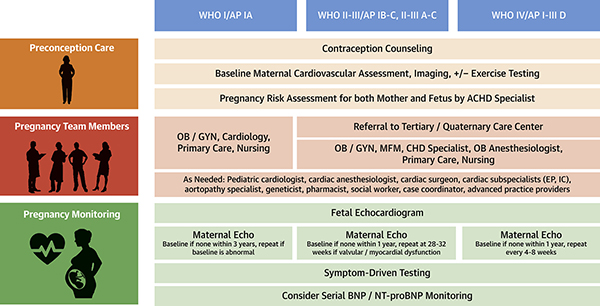

Each patient requires an individualized pregnancy management plan developed by a cardio-obstetrics team that includes specialists from adult congenital cardiology, maternal fetal medicine, obstetric anesthesiology, and pediatric cardiology if the fetus also has CHD (Central Illustration).(3) While each patient will require individualized care plans based on her specific anatomy and physiology, general disease-specific management is outlined in Table 2.(23,26,28–36).

Central Illustration. Multidisciplinary Cardio-Obstetrics Team Management for Women with Congenital Heart Disease.

CHD – Congenital Heart Disease. OB/GYN – Obstetrics and Gynecology. MFM – Maternal-Fetal Medicine. BNP – Brain Natriuretic Peptide. NT-proBNP – N-terminal-pro hormone BNP. Anatomical Classification: I - Simple complexity: Small atrial septal defect (ASD) or ventricular septal defect (VSD), mild pulmonary stenosis (PS), repaired ductus arteriosus, repaired secundum or sinus venosus ASD or VSD without residual shunt or chamber enlargement. II - Moderate complexity: Aorto-left ventricular fistula, anomalous pulmonary venous return, anomalous coronary artery arising from pulmonary artery, anomalous coronary artery arising from opposite sinus, partial or complete atrioventricular septal defect, congenital aortic or mitral valve disease, coarctation of the aorta, Ebstein anomaly, ostium primum ASD, ≥ moderate unrepaired ASD, ≥ moderate unrepaired patent ductus arteriosus, ≥ moderate PS, ≥ pulmonary regurgitation, peripheral PS, sinus of Valsalva fistula/aneurysm, sinus venosus defect, subvalvular or supravalvular aortic stenosis, Tetralogy of Fallot, VSD with associated anomalies and/or ≥ moderate shunt. III - Great complexity: Cyanotic congenital heart defect (unrepaired or palliated), double-outlet ventricle, Fontan procedure, interrupted aortic arch, mitral atresia, single ventricle, pulmonary atresia, transposition of the great arteries (any form), truncus arteriosus, other abnormalities of atrioventricular and ventriculoarterial connection (crisscross heart, isomerism, heterotaxy syndromes, ventricular inversion)(3) Physiological Stage: A – NYHA functional class I symptoms. No hemodynamic or anatomic sequelae. No arrhythmias. Normal exercise capacity. Normal renal/hepatic/pulmonary function. B – NYHA functional class II symptoms. Mild hemodynamic sequelae (mild aortic enlargement, mild ventricular enlargement, mild ventricular dysfunction). Mild valvular disease. Trivial or small shunt (not hemodynamically significant). Arrhythmia not requiring treatment. Abnormal objective cardiac limitation to exercise. C – NYHA functional class III symptoms. Significant (≥ moderate) valvular disease. ≥ moderate ventricular dysfunction (systemic, pulmonic, or both). Moderate aortic enlargement. Venous or arterial stenosis. Mild or moderate hypoxemia/cyanosis. Hemodynamically significant shunt. Arrhythmias controlled with treatment. Pulmonary hypertension (less than severe). End-organ dysfunction responsive to therapy.D – NYHA functional class IV symptoms. Severe aortic enlargement. Arrhythmias refractory to treatment. Severe hypoxiemia (almost always associated with cyanosis). Severe pulmonary hypertension. Eisenmenger syndrome. Refractory end-organ dysfunction.

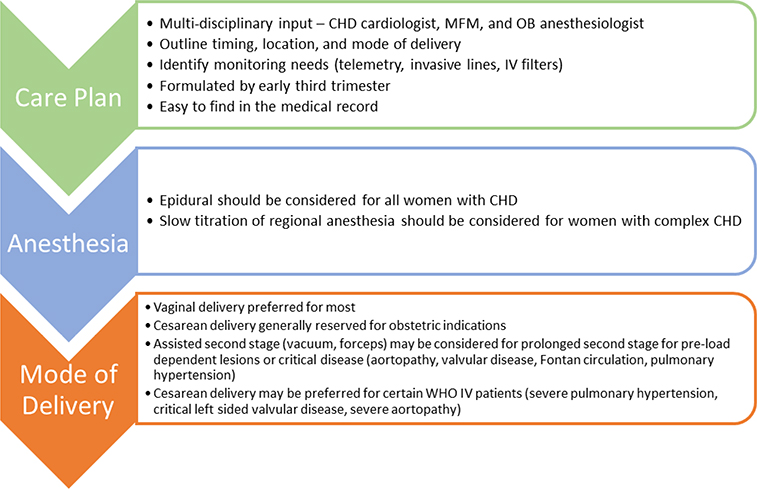

Delivery Planning

Due to the increased risk of spontaneous pre-term birth, the multidisciplinary team should document a detailed delivery care plan by 28 weeks, which is easy to find in the medical record (Figure 3).(3) Vaginal delivery is preferred for the majority of patients, with consideration of an assisted second stage for those with critical disease, aortopathy, or preload-dependent conditions such as pulmonary hypertension or Fontan circulation.(2,23) Epidural anesthetic should be considered for all patients with CHD.(2,23)

Figure 3. Delivery Planning in Women with CHD.

The multidisciplinary cardio-obstetrics team should collaborate to develop a delivery plan by the early third trimester. The delivery plan should include recommendations for anesthesia, monitoring, and timing/mode of delivery. CHD – Congenital Heart Disease. MFM – Maternal Fetal Medicine. OB – Obstetric. IV – intravenous. WHO – World Health Organization.

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH)

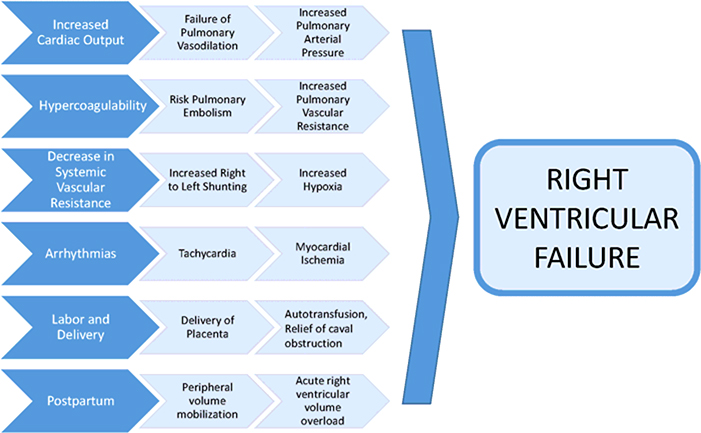

Pregnancy is associated with significant morbidity and mortality risk in all groups of pulmonary hypertension.(37) PAH is considered a contraindication for pregnancy by many U.S.-based and international guidelines.(38,39) Serious cardiovascular complications may be precipitated by a variety of mechanisms during pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period, namely right heart failure (Figure 4).(40) Paradoxical emboli may occur in the presence of patent foramen ovale or Eisenmenger syndrome. Other serious complications include syncope and sudden cardiac death (41).

Figure 4. Contributors to Pregnancy-Associated Right Heart Failure in Women with Pulmonary Hypertension.

Maternal cardiovascular morbidity and mortality due to PAH is most often related to the precipitation of right ventricular failure. Numerous physiologic changes in pregnancy and the postpartum period predispose to right heart failure, including tachycardia, volume overload, hypoxia and hypercoagulability.

Preconception Evaluation

Patients with PAH who are long-term responders to calcium channel blockers are a select group with the most favorable overall prognosis.(37,42) While some contemporary series have reported better outcomes, perhaps due to more widespread use of pulmonary vasodilators, maternal mortality and acute decompensation requiring urgent heart–lung transplantation continue to be reported(43,44) Each patient should be individually evaluated, with the risk/benefit ratio discussed, understanding the limits to our current knowledge. Pre-pregnancy right ventricular dysfunction, impaired hemodynamics, and poor functional class indicate high risk. Based on the risk/benefit ratio, current society guidelines recommend that women with PAH should be counseled that pregnancy is contraindicated, and highly effective contraception recommended.(42,46)

Contraception and Fertility Therapy

Contraception is discussed in detail in part 5 of this manuscript series. Highly effective contraception should be considered in patients with PAH. Combined hormonal methods are generally considered contraindicated due to the risk of thromboembolism.(25,46) The intrauterine device and subdermal implant are safe and provide superior efficacy (Figure 5). Bosentan may reduce the efficacy of oral contraceptive agents. Bosentan, ambrisentan, macitentan and riociguat are all potentially teratogenic; if these are prescribed in women of childbearing age, dual mechanical barrier contraceptive techniques are recommended.(46)

Figure 5. Contraception Recommendations for Women with Pulmonary Hypertension.

Highly effective contraception is recommended to prevent pregnancy in women with pulmonary hypertension. While progesterone only pills and medroxyprogesterone acetate injection are safe, they are less effective than the long acting reversible and permanent contraceptive options. IUD – Intrauterine Device

The safety of fertility procedures/therapies in patients with PAH is not known. Elective oocyte retrieval procedures for surrogacy are a risk but can be considered in a PAH/CHD center with the appropriate multi-disciplinary planning. Currently no guidelines address the risks associated with fertility procedures or therapies.

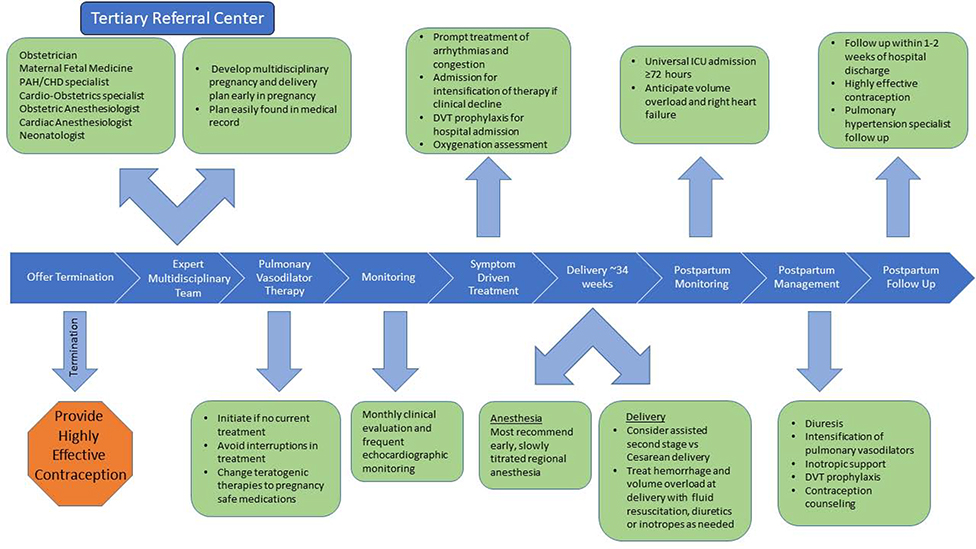

Pregnancy Management

Pregnant women with PAH must be informed of the high risk of the pregnancy to both herself and the fetus and pregnancy termination should be discussed.(42,46) If termination is pursued, this should be performed in a hospital setting at a center with experience in the management of pulmonary hypertension. If pregnancy is continued, disease-targeted therapies should continue with a planned elective delivery and close multidisciplinary collaboration between obstetricians and the PAH team (Figure 6, Table 3) (42,46) Patients may need addition of infusion therapy to baseline oral therapies for improved hemodynamic management. Hospitalization during the second trimester may be required due to the increased risk of premature labor and hemodynamic compromise. (47) Anticoagulation should be continued for patients with a history of thromboembolism prior to pregnancy. Anticoagulation as long-term therapy for prevention of thromboembolism should be individualized.(48)

Figure 6. Algorithm for the Management of Pregnancy in Women with Pulmonary Hypertension.

Management of pregnancy in a women with PAH requires meticulous multidisciplinary collaboration in a center experienced in managing pregnancy in this population of patients. Close monitoring before, during and after delivery is essential to reduce adverse maternal events. DVT – Deep Vein Thrombosis. ICU – Intensive Care Unit.

Table 3.

Pulmonary Vasodilator Therapy Safety in Pregnancy and Lactation

| Medication | Pregnancy | Lactation |

|---|---|---|

| Ambrisentan | CONTRAINDICATED | Benefit/Risk Discussion with Patient, no human data available |

| Bosentan | CONTRAINDICATED | Benefit/Risk Discussion with Patient, no human data available |

| Epoprostenol | Benefit Outweighs Risk | Safe |

| Iloprost | Benefit Outweighs Risk | Benefit/Risk Discussion with Patient, no human data available |

| Macitentan | CONTRAINDICATED | Benefit/Risk Discussion with Patient, no human data available |

| Nitric Oxide | Benefit Outweighs Risk | Benefit/Risk Discussion with Patient, no human data available |

| Riociguat | CONTRAINDICATED | Benefit/Risk Discussion with Patient, no human data available |

| Selexipag | Benefit/Risk discussion with patient. No human data available, but no risk of fetal harm in animal studies at 50x MRHD | Benefit/Risk Discussion with Patient, no human data available |

| Sildenafil | Benefit Outweighs Risk | Benefit/Risk Discussion with Patient, limited human data available, though harm not expected based on drug properties |

| Tadalafil | Benefit Outweighs Risk | Benefit/Risk Discussion with Patient, no human data available |

| Treprostinil | Benefit Outweighs Risk | Safe |

MRHD – maximum recommended human dose.

Delivery Planning

A multidisciplinary approach to delivery at a pulmonary hypertension center including both the obstetric and cardiovascular anesthesiology services is recommended.(49) It is best to have a comprehensive plan and a non-emergent procedure.(43) There are no guidelines regarding the best method of delivery or anesthesia, and the delivery plan should be individualized for each patient. Some experts recommend early Cesarean delivery around 34 weeks gestation.(48) A small series from the United Kingdom reported success in 10 pregnancies utilizing a tailored multi-professional approach with early induction of targeted therapy, early planned delivery, and regional anesthetic techniques.(50) Single-dose spinal anesthesia should be avoided due to the risk of hypotension and hemodynamic instability.(48) In patients with Eisenmenger syndrome, recommendations for management of shunt lesions should be considered in addition to those for PAH (Table 2).

Postpartum Care

Most maternal deaths due to PAH occur in the first month postpartum, due to right heart failure, sudden death, or thromboembolism.(48) Women with PAH should be monitored closely after delivery for evidence of right heart failure, and in an intensive care setting for at least the first several days due to the risk of rapid decompensation in the setting of postpartum volume shifts.(48) Pharmacologic thromboembolism prophylaxis in the postpartum period is essential.(48)

Valvular Heart Disease

Valve disease among childbearing women in the US is most frequently congenital, but rheumatic disease is more prevalent among patients who have emigrated from low-resource countries. Women with valvular heart disease are at increased risk for complications during pregnancy including heart failure, atrial arrhythmias, postpartum hemorrhage, and poor fetal outcomes.(51)

Preconception Evaluation

Preconception risk stratification by a cardiologist and MFM with expertise in valvular heart disease in pregnancy is recommended based upon functional class and echocardiography for all valvular conditions.(52) Asymptomatic women with severe valve disease may be considered for risk assessment via exercise testing.(52) Preconceptual valve intervention is recommended for women who meet guideline-based criteria for valve intervention, or who are mWHO IV pregnancy risk due to their valve condition.(52)

Contraception

All methods of contraception are safe for women with uncomplicated valvular heart disease.(25) Women with prosthetic heart valves or risk for thrombotic complications should be advised to avoid combined hormonal contraceptives due to the risk of thromboembolism, particularly if effective alternative options are available (Figure 7).(25)

Figure 7. Contraception Recommendations for Women with Valvular Heart Disease.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (the IUD and subdermal implant) and permanent sterilization are safe and highly effective for all women with valvular heart disease. Caution should be advised when prescribing combined hormonal contraceptives to women with mechanical valves or atrial fibrillation due to the increased risk of thromboembolism.

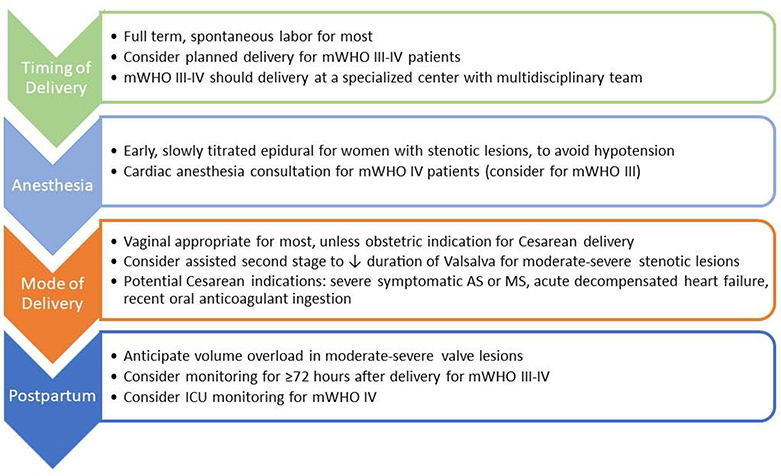

Pregnancy and Delivery Planning

Women with severe valve disease (Stages C and D) require an experienced multidisciplinary cardio-obstetrics team, including a cardiologist with expertise in pregnancy for women with CHD or valvular heart conditions, MFM, surgeons and cardiac and obstetric anesthesiologists at a tertiary-care center.(52) The cardio-obstetrics team should develop a comprehensive pregnancy management and delivery plan according to the patient’s individualized needs (Table 4).(4) The delivery plan, including the potential need for invasive hemodynamic monitoring, should be documented in the medical record prior to labor. Most asymptomatic women may be permitted to go into spontaneous labor (Figure 8). At the time of delivery there is an abrupt increase in left ventricular afterload increasing the risk for acute heart failure. The early postpartum period is the highest risk time for deterioration, so extended inpatient observation and close outpatient follow-up are required.

Table 4.

Pregnancy Risk Stratification and Management of Native Valvular Conditions

| Valve Lesion | Common Underlying Conditions | WHO Risk | Potential Complications | Principles of Management | Delivery | Postpartum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic Stenosis | Bicuspid Valve, Subaortic Membrane, Supravalvular Stenosis, Rheumatic | II - Mild | Arrhythmias, Heart Failure, Aortic Dissection if bicuspid aortopathy, Urgent Surgery, Rarely death in WHO IV | Multidisciplinary Team for ≥ Moderate AS | Consider assisted second stage or Cesarean if severe or symptomatic | Anticipat e need for diuresis |

| III - Moderate | Consider pre-conception exercise testing in asymptomatic women | Slow titration of regional anesthesia | Consider monitoring ≥72 hours | |||

| IV - AVA <1.0, Peak gradien t >50 mmHg | Serial echocardiography for ≥ moderate AS Volume management with diuresis Heart Rate control Prompt treatment of arrhythmias | Avoid Volume Overload | ||||

| Mitral Stenosis | Congenital – parachute, Rheumatic | III – Mild MS | Arrhythmias, Thromboembolism, Heart Failure, Urgent Surgery or Valvuloplasty, Death in WHO IV | Multidisciplinary Team | Consider assisted second stage or Cesarean if ≥ moderate or symptomatic | Anticipat e need for diuresis |

| IV - MVA <1.5 cm2 | Thromboembolism | Serial echocardiography | Slow titration of regional anesthesia | Consider monitori ng ≥72 hours | ||

| Heart Failure Increased valve gradients | Volume management with diuresis Heart Rate control | Avoid Volume Overload | ||||

| Urgent Surgery or Valvuloplasty | Prompt treatment of arrhythmias | |||||

| Death in WHO IV | Anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, left atrial thrombosis, prior embolism, severe MS, spontaneous echo contrast in the LA, LAVI ≥60 mL/m2, or heart failure | |||||

| Aortic Regurgitation | Bicuspid Valve, Aortopathy, History of Ross Procedure, Endocarditis, D-TGA with Arterial Switch, Rheumatic | II - Mild to Moderate | Arrhythmias | Volume management with diuresis | Vaginal delivery | Anticipat e need for diuresis if ≥ moderate |

| III - Moderate to Severe | Heart Failure Urgent Surgery | Management of hypertension Serial echocardiography if moderate to severe | Epidural recomme nded Avoid Volume Overload | |||

| Mitral Regurgitation | Mitral Valve Prolapse, Rheumatic, Congenital – parachute, Functional | II - Mild | Arrhythmias | Volume management with diuresis | Vaginal delivery | Anticipate need for diuresis if ≥ moderate |

| III - Moderate to Severe | Heart Failure | Management of hypertension | Epidural recommended | |||

| Worsening Mitral Regurgitation | Serial echocardiography if moderate to severe | Avoid Volume Overload | ||||

| Pulmonary Stenosis | Congenital Pulmonary Stenosis, Sequelae of Tetralogy of Fallot | I - Mild | Arrhythmias | Serial echocardiography for ≥ moderate PS | Vaginal delivery | Anticipat e need for diuresis if ≥ moderate |

| II - Moderate | Right Heart Failure | Volume management with diuresis | Slow titration of regional anesthesia Preload Dependent | |||

| III - Severe | Increased valve gradients | |||||

| Pulmonary Regurgitation | Congenital Pulmonary Stenosis - Following Valvuloplasty or Valvotomy, Sequelae of Tetralogy of Fallot | I - Mild to Moderate | Arrhythmias | Serial echocardiography for ≥ moderate PI or RV enlargement or dysfunction | Vaginal delivery | Anticipate need for diuresis if RV dysfunction is present |

| II-III - Severe | Right Heart Failure | Volume management with diuresis | Epidural recomme nded | |||

| Tricuspid Regurgitation | Ebstein Anomaly, Endocarditis, Functional | I - Mild | Arrhythmias | Serial echocardiography for ≥ moderate TR or RV enlargement or dysfunction | Vaginal delivery | Anticipat e need for diuresis if RV dysfuncti on is present |

| II - Moderate | Right Heart Failure | Volume management with diuresis | Epidural recomme nded | |||

| III - Severe | ||||||

While each patient requires individualized management, this table provides general disease-specific recommendation for the management of women with native valvular heart disease.

WHO – World Health Organization. AS – aortic stenosis. AVA – aortic valve area. MS – mitral stenosis. MVA – mitral valve area. LA – left atrium. LAVI – left atrial volume index. TGA – transposition of the great arteries. PS – pulmonary stenosis. PI – pulmonary insufficiency. RV – right ventricle. TR – tricuspid regurgitation.

Figure 8. Delivery Planning in Women with Valvular Heart Disease.

The multidisciplinary cardio-obstetrics team should collaborate to develop a delivery plan for women with mWHO class III-IV conditions. The delivery plan should include recommendations for anesthesia, monitoring, and timing/mode of delivery. Extended postpartum monitoring should be considered for women with ≥ moderate valve lesions due to the increased risk of postpartum heart failure. mWHO – modified World Health Organization. AS – Aortic Stenosis. MS – Mitral Stenosis. ICU – Intensive Care Unit.

Specific Disorders

Bioprosthetic Valves

It is uncertain whether pregnancy contributes to premature structural valve deterioration of bioprosthetic valves.(53) Valves in the mitral position are more likely to undergo structural deterioration than those in the aortic position.

Mechanical Valves

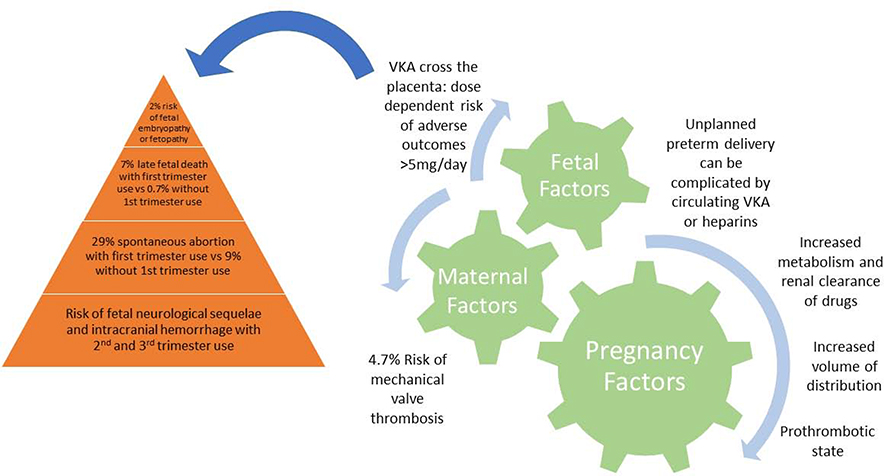

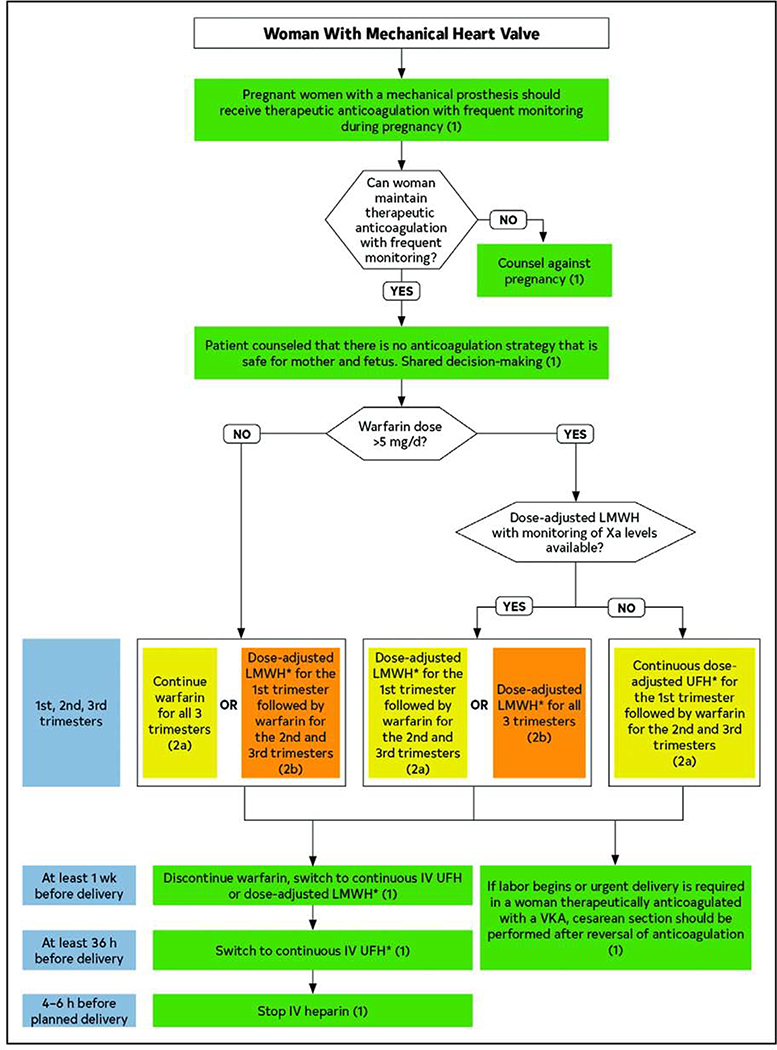

Management of pregnant women with mechanical heart valves requires a balance of the maternal risk of thromboembolic complications with the risk of fetal teratogenicity and loss (Figure 9). Recent reviews have better defined the maternal and fetal risks of pregnancy and anticoagulation in women with mechanical heart valves (Table 5).(54,55) Anticoagulation management requires a thoughtful, detailed discussion with the patient. Recent ACC/AHA management guidelines are presented in Figure 10.(56) Following delivery, IV unfractionated heparin should be resume ~6 hours after vaginal delivery or 12 hours after Cesarean delivery, depending on adequacy of hemostasis. Warfarin should be resumed prior to hospital discharge, with a low molecular weight heparin bridge, and continued through breastfeeding.

Figure 9. Maternal and Fetal Factors to Consider in the Management of Prosthetic Valves in Pregnant Women.

Maternal physiologic changes must be considered in addition to fetal risks of warfarin exposure when considering optimal medication choice and dosing for women requiring anticoagulation during pregnancy. VKA – Vitamin K Antagonists.

Table 5.

Maternal and Fetal Risks of Pregnancy with Mechanical Heart Valves

| ROPAC | ||||

| Mechanical Heart Valve | Bioprosthetic Heart Valve | No Prosthetic Valve | ||

| Maternal Mortality | 1.4% | 1.5% | 0.20% | |

| Any Serious Adverse Event | 42.0% | 21.0% | 22% | |

| D’Souza et al | ||||

| VKA Throughout | Heparins 1st trimester/VKA 2nd and 3rd trimester | LMWH Throughout | UFH Throughout | |

| Maternal Mortality | 0.9% | 2.0% | 2.9% | 3.4% |

| Thromboembolism | 2.7% | 5.8% | 8.7% | 11.2% |

| Live Births | 64.5% | 79.9% | 92.0% | 69.5% |

| Warfarin Embryopathy or Fetopathy | 2.0% | 1.4% | NA | NA |

VKA – Vitamin K Antagonist. LMWH – Low Molecular Weight Heparin. UFH – Unfractionated Heparin

Figure 10. Management Algorithm for Pregnant Women with Mechanical Heart Valves.

Reproduced from the 2020 ACC/AHA Valvular Heart Disease Guidelines. Shared decision making should be employed to determine the optimal anticoagulant dosing regimen for each individual patient during pregnancy. Weekly INR or Xa levels should be monitored to ensure adequate anticoagulation. Warfarin and LMWH need to be discontinued in advance of delivery, with an intravenous UFH bridge to permit for regional anesthesia. *Dose-adjusted LMWH should be given at least 2 times per day, with close monitoring of anti-Xa levels. Target to Xa level of 0.8 to 1.2 U/mL, 4–6 hours after dose. Trough levels may aid in maintaining patient in therapeutic range. Continuous UFH should be adjusted to aPTT 2 times control. Green: Class I recommendation; Yellow: Class IIa recommendation; Orange: Class IIb recommendation.

Aortic and Mitral Stenosis

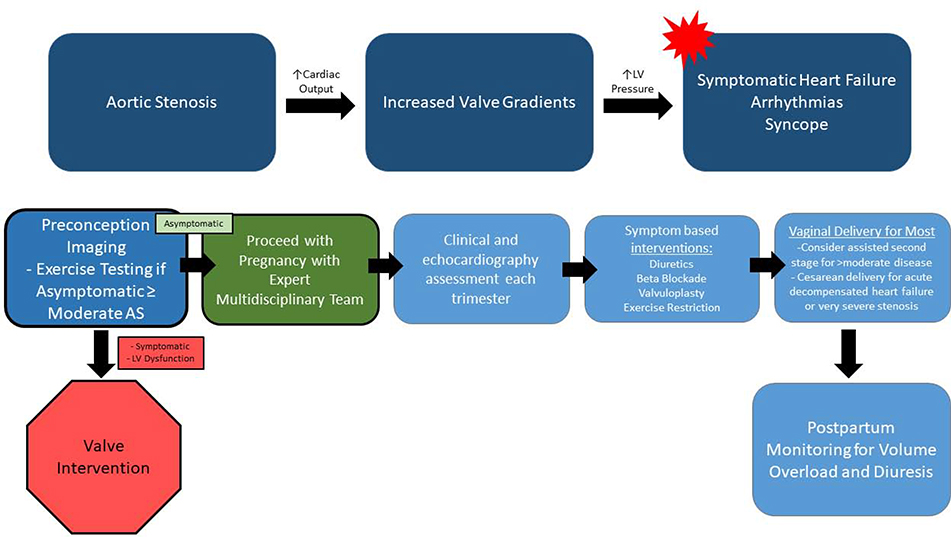

Severe aortic stenosis (AS) and mitral stenosis (MS) are associated with a high risk of adverse events in pregnancy, though even mild MS may be poorly tolerated.(26,57–61) Transvalvular gradients will increase with the increased heart rate and stroke volume of pregnancy, and may precipitate heart failure, arrhythmias, or pulmonary venous hypertension. Exercise testing is recommended in asymptomatic patients with stenotic valvular disease to evaluate the need for preconceptual intervention (Figures 11 and 12).(23,52)

Figure 11. Hemodynamic Changes and Proposed Management Algorithm for Pregnant Women with Aortic Stenosis.

Aortic valve gradients are expected to increase in the setting of pregnancy, and may lead to adverse maternal outcomes. Serial imaging, heart rate control and volume management are useful in caring for pregnant women with MS. While most women may undergo vaginal delivery, some may need consideration of assisted second stage or Cesarean delivery depending on disease severity and clinical status. LV – Left ventricular.

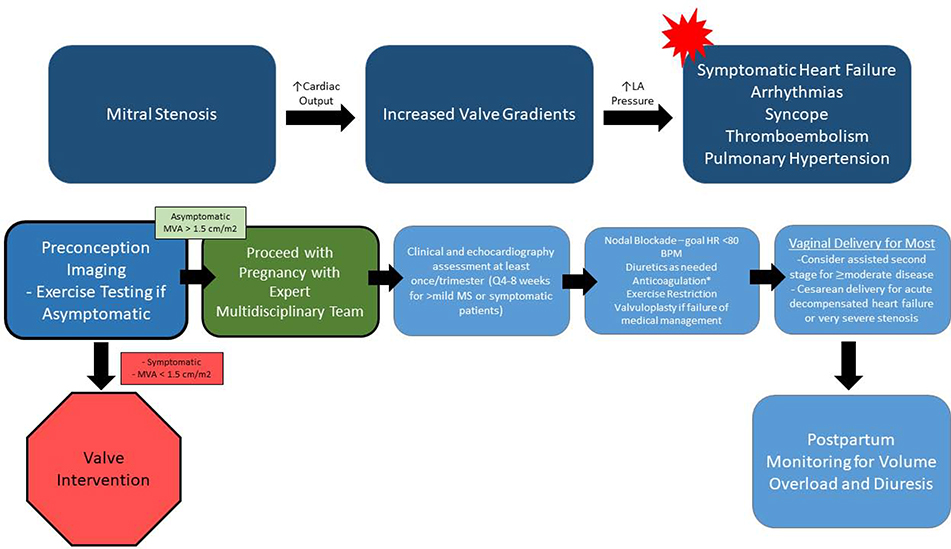

Figure 12. Hemodynamic Changes and Proposed management Algorithm for Pregnant Women with Mitral Stenosis.

Mitral valve gradients are expected to increase in the setting of pregnancy, and may lead to adverse maternal outcomes. Serial imaging, heart rate control, volume management and anticoagulation are useful in caring for pregnant women with MS. While most women may undergo vaginal delivery, some may need consideration of assisted second stage or Cesarean delivery depending on disease severity and clinical status.LA – Left atrial. MVA – Mitral Valve Area. MS – Mitral Stenosis. HR – Heart Rate. *Anticoagulation is indicated for atrial fibrillation, left atrial thrombosis, prior embolism, severe MS, spontaneous echo contrast in the LA, Left atrial volume index ≥60 mL/m2, or heart failure.

Left-sided stenotic valve lesions require close multidisciplinary management by an experienced team, with prompt treatment of congestion and arrhythmias. Symptoms may begin to develop in the second trimester and women remain at risk for heart failure into the postpartum period. Beta-blockers are recommended to decrease the trans-valvular flow rate and gradient, with diuretics as needed for congestion, and anticoagulation when indicated.(52,62) For progressive symptoms despite medical therapy, percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty may be considered with abdominal shielding by an experienced operator in appropriate patients, preferably in the second trimester. In most cases, congenital MS is not amenable to balloon valvuloplasty, highlighting the importance of accurate preconception valve characterization. If balloon valvuloplasty is contraindicated, surgical valve replacement should be considered after early Cesarean delivery.

Aortic and Mitral Regurgitation

Chronic aortic and mitral regurgitation are generally well tolerated, though women with severe mitral regurgitation are at risk of heart failure particularly in the postpartum period in the setting of volume mobilization. Patients with baseline symptoms or left ventricular systolic dysfunction should undergo surgery prior to conception.(63) Acute valve regurgitation remains a surgical emergency and must be dealt with accordingly even in pregnancy.

Pulmonary Stenosis

Pulmonary stenosis (PS) even when severe is generally well-tolerated in pregnancy.(64) Women with PS typically do not require intervention prior to or during pregnancy; balloon valvuloplasty can be considered after the first trimester for severe symptoms refractory to medical therapy.

Pulmonary and Tricuspid Regurgitation

Pulmonic and tricuspid regurgitation are usually associated with CHD. In the absence of pre-conception right heart failure, women typically do well throughout pregnancy. Patients with right sided valve procedures are at risk for atrial arrhythmias and right-sided heart failure, and may require diuretics in the later stages of pregnancy and following delivery.

Conclusions

Most women with congenital and heritable cardiovascular conditions can have a successful pregnancy. This requires coordinated multi-disciplinary care from the pre-conception through postpartum period to optimize maternal and fetal outcomes. Women with moderate to complex conditions require expert cardio-obstetric management at referral centers.

Key Points.

Congenital heart disease is the most common cardiovascular condition encountered in pregnant women

Most women with congenital and heritable conditions can be safely managed with a team-based approach throughout pregnancy

High-risk conditions include pulmonary hypertension, cardiomyopathy, left-sided obstructive valvular disease, and certain aortopathies.

Long-acting reversible contraception is safe and effective for patients with congenital and heritable cardiovascular conditions.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Bello- NIH/NHLBI ( K23 HL136853-03, R01 HL153382-01)

Disclosures:

Gomberg-Maitland - Research grant support to GWU-MFA from Acceleron, Bayer, Complexa, and United Therapeutics. Consultant for Actelion, Altavant, Acceleron, Bayer, Gilead, Insemed, Reata, United Therapeutics

Bairey Merz – Consultant for Abbott, Sanofi. Board of Director for iRhythm.

Park – Consultant for Abbott

The remaining authors have no disclosures.

Abbreviations

- CHD

Congenital heart disease

- WHO

World Health Organization

- CT

computed tomography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ROPAC

Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease

- PAH

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- MFM

Maternal Fetal Medicine

- MS

Mitral Stenosis

- AS

Aortic Stenosis

- PS

Pulmonary Stenosis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hirshberg A, Srinivas SK. Epidemiology of maternal morbidity and mortality. Seminars in perinatology 2017;41:332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canobbio MM, Warnes CA, Aboulhosn J et al. Management of Pregnancy in Patients With Complex Congenital Heart Disease: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135:e50–e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 212: Pregnancy and Heart Disease. Obstetrics and gynecology 2019;133:e320–e356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lansman SL, Goldberg JB, Kai M, Tang GH, Malekan R, Spielvogel D. Aortic surgery in pregnancy. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 2017;153:S44–S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamel H, Roman MJ, Pitcher A, Devereux RB. Pregnancy and the Risk of Aortic Dissection or Rupture: A Cohort-Crossover Analysis. Circulation 2016;134:527–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beyer SE, Dicks AB, Shainker SA et al. Pregnancy-associated arterial dissections: a nationwide cohort study. Eur Heart J 2020;41:4234–4242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braverman AC, Mittauer E, Harris KM et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Pregnancy-Related Acute Aortic Dissection. JAMA Cardiol 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA et al. 2010. ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Thoracic Aortic Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 April 6;55(14):e27–e129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gravholt CH, Andersen NH, Conway GS et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: proceedings from the 2016 Cincinnati International Turner Syndrome Meeting. Eur J Endocrinol 2017;177:G1–g70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams D, Lindley KJ, Russo M, Habashi J, Dietz HC, Braverman AC. Pregnancy after Aortic Root Replacement in Marfan’s Syndrome: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. AJP reports 2018;8:e234–e240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudd NL, Nimrod C, Holbrook KA, Byers PH. Pregnancy complications in type IV Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Lancet 1983;1:50–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray ML, Pepin M, Peterson S, Byers PH. Pregnancy-related deaths and complications in women with vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Genet Med 2014;16:874–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byers PH, Belmont J, Black J et al. Diagnosis, natural history, and management in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2017;175:40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frise CJ, Pitcher A, Mackillop L. Loeys-Dietz syndrome and pregnancy: The first ten years. Int J Cardiol 2017;226:21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loeys BL, Dietz HC. Loeys-Dietz Syndrome. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. , editors. GeneReviews(®). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; Copyright © 1993–2020, University of Washington, Seattle. GeneReviews is a registered trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle. All rights reserved., 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Hemelrijk C, Renard M, Loeys B. The Loeys-Dietz syndrome: an update for the clinician. Curr Opin Cardiol 2010;25:546–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milewicz DM, Regalado ES, Shendure J, Nickerson DA, Guo DC. Successes and challenges of using whole exome sequencing to identify novel genes underlying an inherited predisposition for thoracic aortic aneurysms and acute aortic dissections. Trends in cardiovascular medicine 2014;24:53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roos-Hesselink J, Baris L, Johnson M et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with cardiovascular disease: evolving trends over 10 years in the ESC Registry Of Pregnancy And Cardiac disease (ROPAC). Eur Heart J 2019;40:3848–3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Hagen IM, Roos-Hesselink JW, Donvito V et al. Incidence and predictors of obstetric and fetal complications in women with structural heart disease. Heart 2017;103:1610–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramage K, Grabowska K, Silversides C, Quan H, Metcalfe A. Association of Adult Congenital Heart Disease With Pregnancy, Maternal, and Neonatal Outcomes. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e193667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindley KJ, Conner SN, Cahill AG, Madden T. Contraception and Pregnancy Planning in Women With Congenital Heart Disease. Current treatment options in cardiovascular medicine 2015;17:50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Society of G, Association for European Paediatric C, German Society for Gender M et al. ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2011;32:3147–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohuchi H, Tanabe Y, Kamiya C et al. Cardiopulmonary variables during exercise predict pregnancy outcome in women with congenital heart disease. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society 2013;77:470–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tepper NK, Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Whiteman MK. Updated Guidance for Safe and Effective Use of Contraception. Journal of women’s health 2016;25:1097–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorne S, MacGregor A, Nelson-Piercy C. Risks of contraception and pregnancy in heart disease. Heart 2006;92:1520–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donofrio MT, Moon-Grady AJ, Hornberger LK et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Fetal Cardiac Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jain VD, Moghbeli N, Webb G, Srinivas SK, Elovitz MA, Pare E. Pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease: the impact of a systemic right ventricle. Congenital heart disease 2011;6:147–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canobbio MM, Morris CD, Graham TP, Landzberg MJ. Pregnancy outcomes after atrial repair for transposition of the great arteries. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:668–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowater SE, Selman TJ, Hudsmith LE, Clift PF, Thompson PJ, Thorne SA. Long-term outcome following pregnancy in women with a systemic right ventricle: is the deterioration due to pregnancy or a consequence of time? Congenital heart disease 2013;8:302–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balci A, Drenthen W, Mulder BJ et al. Pregnancy in women with corrected tetralogy of Fallot: occurrence and predictors of adverse events. Am Heart J 2011;161:307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jimenez-Juan L, Krieger EV, Valente AM et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging predictors of pregnancy outcomes in women with coarctation of the aorta. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging 2014;15:299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Gloan L, Mercier LA, Dore A et al. Pregnancy in women with Fontan physiology. Expert review of cardiovascular therapy 2011;9:1547–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horiuchi C, Kamiya CA, Ohuchi H et al. Pregnancy outcomes and mid-term prognosis in women after arterial switch operation for dextro-transposition of the great arteries - Tertiary hospital experiences and review of literature. J Cardiol 2019;73:247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fricke TA, Konstantinov IE, Grigg LE, Zentner D. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women After the Arterial Switch Operation. Heart Lung Circ 2020;29:1087–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tutarel O, Ramlakhan KP, Baris L et al. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women After Arterial Switch Operation for Transposition of the Great Arteries: Results From ROPAC (Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease) of the European Society of Cardiology EURObservational Research Programme. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e018176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, Denton CP, Gatzoulis MA, Krowka M, Williams PG, Souza R. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019. January 24;53(1):1801913. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01913-2018. PMID: 30545968;. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Galiè N, Channick RN, Frantz RP et al. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019;53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2016;69:177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olsson KM, Channick R. Pregnancy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 2016;25:431–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsu CH, Gomberg-Maitland M, Glassner C, Chen JH. The management of pregnancy and pregnancy-related medical conditions in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients. Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2011:6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Heart J 2016;37:67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jais X, Olsson KM, Barbera JA et al. Pregnancy outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern management era. Eur Respir J 2012;40:881–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duarte AG, Thomas S, Safdar Z et al. Management of pulmonary arterial hypertension during pregnancy: a retrospective, multicenter experience. Chest 2013;143:1330–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sliwa K, van Hagen IM, Budts W et al. Pulmonary hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: data from the Registry Of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:1119–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klinger JR, Elliott CG, Levine DJ et al. Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Adults: Update of the CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2019;155:565–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Terek D, Kayikcioglu M, Kultursay H et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and pregnancy. J Res Med Sci 2013;18:73–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hemnes AR, Kiely DG, Cockrill BA et al. Statement on pregnancy in pulmonary hypertension from the Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute.Pulm Circ 2015;5:435–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taichman DB, Ornelas J, Chung L et al. Pharmacologic therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2014;146:449–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kiely DG, Condliffe R, Webster V et al. Improved survival in pregnancy and pulmonary hypertension using a multiprofessional approach. BJOG 2010;117:565–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roos-Hesselink JW, Ruys TP, Stein JI et al. Outcome of pregnancy in patients with structural or ischaemic heart disease: results of a registry of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:657–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Otto Catherine M, Nishimura Rick A, Bonow Robert O et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. December 17:S0735–1097(20)37796–2. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hung L Prosthetic Heart Valves and Pregnancy. Circulation 2003;107:1240–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Hagen IM, Roos-Hesselink JW, Ruys TP et al. Pregnancy in Women With a Mechanical Heart Valve: Data of the European Society of Cardiology Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC). Circulation 2015;132:132–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.D’Souza R, Ostro J, Shah PS et al. Anticoagulation for pregnant women with mechanical heart valves: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1509–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ginsberg JS, Chan WS, Bates SM, Kaatz S. Anticoagulation of pregnant women with mechanical heart valves. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:694–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drenthen W, Boersma E, Balci A et al. Predictors of pregnancy complications in women with congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J 2010;31:2124–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Orwat S, Diller GP, van Hagen IM et al. Risk of Pregnancy in Moderate and Severe Aortic Stenosis: From the Multinational ROPAC Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:1727–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silversides CK, Grewal J, Mason J et al. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With Heart Disease: The CARPREG II Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:2419–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silversides CK, Colman JM, Sermer M, Siu SC. Cardiac risk in pregnant women with rheumatic mitral stenosis. The American journal of cardiology 2003;91:1382–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hameed A, Karaalp IS, Tummala PP et al. The effect of valvular heart disease on maternal and fetal outcome of pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:893–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J 2018;39:3165–3241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO et al. 2014. AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 June 10;63(22):e57–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hameed AB, Goodwin TM, Elkayam U. Effect of pulmonary stenosis on pregnancy outcomes--a case-control study. Am Heart J 2007;154:852–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]