Abstract

Introduction

Globally, a substantial number of women experience abusive and disrespectful care from health providers during childbirth. As evidence mounts on the nature and frequency of disrespect and abuse (D&A), little is known about the consequences of a negative experience of care on health and well-being of women and newborns. This review summarises available evidence on the associations of D&A of mother and newborns during childbirth and the immediate postnatal period (understood as the first 24 hours from birth) with maternal and neonatal postnatal care (PNC) utilisation, newborn feeding practices, newborn weight gain and maternal mental health.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of all published qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies on D&A and its postnatal consequences across all countries. Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, LILACS and Scopus were searched using predetermined search terms. Quantitative and qualitative data were analysed and presented separately. Thematic analysis was used to synthesise the qualitative evidence.

Results

A total of 4 quantitative, 1 mixed-methods and 16 qualitative studies were included. Quantitative studies suggested associations between several domains of D&A and use of PNC as well as maternal mental health. Different definitions of exposure meant formal meta-analysis was not possible. Three main themes emerged from the qualitative findings associated with PNC utilisation: (1) women’s direct experiences; (2) women’s expectations and (3) women’s agency.

Conclusion

This review is the first to examine the postnatal effect of D&A of women and newborns during childbirth. We highlight gaps in research that could help improve health outcomes and protect women and newborns during childbirth. Understanding the health and access consequences of a negative birth experience can help progress the respectful care agenda.

Keywords: maternal health, obstetrics, health services research, systematic review

Key questions.

What is already known?

A substantial number of women experience disrespectful and abusive care (D&A) from health providers during childbirth.

A study conducted in four low/middle-income countries (LMICs) found that 41.6% of women had experienced one or more episodes of physical abuse, verbal abuse, stigma or discrimination; with younger, poorer, unemployed, illiterate and unmarried women being the most at risk.

Postnatal care (PNC) use has consistently had among the lowest coverage among interventions on the continuum of maternal and childcare, with a reported median coverage for the 75 LMICs in the Countdown to 2030 initiative at 28% for babies and 58% for mothers.

A recent qualitative study showed that factors affecting utilisation of PNC not only include cost and distance to the healthcare facility and lack of knowledge of the importance of PNC, but also fear of mistreatment by healthcare workers, fear of denial of PNC or actual denial or delay of care.

What are the new findings?

Our systematic review shows that experiencing D&A during childbirth is associated with reduced utilisation of maternal or neonatal PNC, particularly when the woman did not have a companion at the birth, was not offered a choice of birth position or when she perceived that the facility was not clean.

Women’s decision to seek PNC is not solely influenced by their previous experience but also by other factors such as their own expectations and agency which are shaped by broader cultural, social and gender norms.

Experiencing verbal abuse from health providers during childbirth can also take a toll on women’s mental health, increasing the likelihood of developing depression during the postpartum period.

Key questions.

What do the new findings imply?

Health providers and policymakers should increase efforts to guarantee high-quality, respectful, dignified and supportive care throughout the continuum of care to increase coverage of essential services and to promote and protect the health and well-being of women and newborns.

Our findings shed light on the potential consequences of D&A on healthcare seeking behaviours; more research is urgently needed to understand the public health implications of a negative experience at birth on the health of women and newborns.

Introduction

During the millennium development goal era, global efforts were aimed at ensuring that all women and their newborns had access to skilled care before, during and after childbirth as a way to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.1 Despite achieving a 45% reduction in the maternal mortality ratio between 1990 and 2013, these efforts fell short of the target.2 In recent years, evidence emerged suggesting that the quality of care received by women and newborns during facility-based birth was not meeting the required standard.3–7 Around the world, a substantial number of women experienced abusive and disrespectful care from health providers.

In 2010, the publication of the landscape analysis on disrespect and abuse (D&A) by Bowser and Hill led to the global recognition of the poor treatment women experienced during childbirth, including physical abuse, non-consented care or discrimination by healthcare providers.3 Later, a mixed-methods review conducted by Bohren et al concluded that ‘D&A’ should be replaced by ‘mistreatment during childbirth’ (MDC), a term that further separates the issue from individual intentionality and links it to the realm of healthcare quality, introducing an alternative 7-domain typology which integrated health systems constraints (box 1). Using the MDC typology, a recent study found that 41.6% of women attending urban maternity hospitals across four low/middle-income countries (LMICs) had experienced at least one episode of physical abuse, verbal abuse, stigma or discrimination.8 Younger, poorer, unemployed, illiterate and unmarried women were more likely to experience this type of treatment.9

Box 1. Defining terminology.

For the purpose of this review, we conceptualise ‘disrespect and abuse’ (D&A) as a broad term which encompasses an interpersonal and a structural component. The interpersonal component refers to actions by health providers towards women during childbirth that involve violence, discrimination, oppression or disrespect, regardless of intentionality. The structural component refers to constraints in the health system that affect the provision of good quality care rooted in power asymmetries, institutional structures, economic inequality, or social and gender norms. Mistreatment during childbirth overlaps with D&A by referring to instances of poor-quality care at the patient-provider level caused by constraints in the health system. While we recognise more nuances exist between terminologies, we have decided to use D&A as a broader term throughout the text to increase consistency and clarity.

As global evidence mounts on the nature and frequency of D&A during childbirth,10–14 little is known about the consequences of negative experiences of care on the health and well-being of women and newborns. Negative experiences during antenatal, intrapartum or immediate postpartum care might influence women’s care-seeking behaviour after birth, particularly regarding accessing postnatal care (PNC). A recent qualitative study showed that factors affecting utilisation of PNC not only include cost and distance to the healthcare facility and lack of knowledge of the importance of PNC, but also fear of mistreatment by healthcare workers, fear of denial of PNC or actual denial of care.15 This offers a potential hypothesis to explain why, despite great improvements in overall access to institutional care, PNC has consistently had among the lowest coverage on the continuum of maternal and child care.16 17 While many of the arguments in favour of preventing D&A are framed in the context of human rights or maternal and neonatal survival, it is also necessary to understand how the childbirth experience can affect the interactions of women and newborns with the healthcare system, and subsequently their health.18

PNC includes any provision of healthcare for the woman and the baby during the postnatal period, from childbirth until 6 weeks post partum.19 In this period, women and newborns are particularly susceptible to widespread and persistent childbirth-related morbidities, many of which are unreported and go unnoticed and untreated by healthcare professionals.20 Common health problems for women include physical morbidity, such as backache,21 22 perineal pain,23 24 stress incontinence,25–27 breastfeeding problems28–30 and mental health problems, such as postpartum depression (PPD).31–34 The likelihood of depressive episodes after childbirth can be twice as high compared with any other period of a woman’s life.35 Women who suffer from postnatal mental health disorders have prolonged difficulties in developing maternal feelings towards their infants compared with women who do not experience these, with direct effects on infants’ health and development, such as delayed psycho-social development, low-birth weight, reduced breast feeding, hampered growth and lower compliance with immunisation schedules.36 37 Therefore, timely screening and identification of women’s needs are essential to ensuring women have sufficient support during their initiation to motherhood, to promoting her health and her baby’s and to fostering an environment that offers support to the extended family and community for a wide range of health and social needs.38–40 In addition to the need for improvements in the quality of care received by women and newborns in the intrapartum period, evidence on the consequences of D&A on women and newborns’ health, well-being and care-seeking behaviours is necessary to inform programme implementation, policy and advocacy.

This review will answer the following research question: what are the associations of (a) D&A of mother and newborn during childbirth and the immediate postnatal period (understood as the first 24 hours from birth) with (b) maternal and neonatal PNC utilisation, newborn feeding practices, newborn weight gain and maternal mental health?

Methods

Type of review

A mixed-methods review was conducted following a parallel-result segregated synthesis design. In this review, quantitative and qualitative data were analysed and presented separately with integration occurring in the discussion.41 The rationale for conducting a mixed-methods review was to acknowledge the complexity of the issue of D&A during childbirth. We not only aimed to quantify the relation between D&A and the selected outcomes (quantitative analysis) but also to explore how other factors enable or inhibit this relationship (qualitative analysis).

Search strategy

Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, LILACS and Scopus were systematically searched using controlled vocabulary and free-text terms for: (a) D&A or mistreatment of women or newborns during childbirth, (b) maternal, perinatal, neonatal, postnatal health, (c) access to care, (d) breast feeding or PNC utilisation or PPD or infant weight gain (online supplemental appendix 1). The search was restricted to published articles from 20 September 2010 until March 2020. The starting date of the search was selected as it coincides with the date of the publication of Bowser and Hill’s seminal landscape analysis.3 Reviews and reference lists from identified articles were hand searched to identify additional studies.

bmjgh-2020-004698supp001.pdf (402KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

For the quantitative analyses, we included studies if: (a) they were primary research conducted using quantitative research designs; (b) the sample included women who have given birth at a health facility; (c) they measured the association of D&A with PNC utilisation after initial discharge, maternal PPD or other mental health outcome, breast feeding or infant weight gain and (d) were conducted in LMICs by the World Bank definition.42

For the qualitative analyses, we included studies if they (a) were primary research conducted using qualitative methods; (b) discussed issues related to D&A, and PNC utilisation, maternal PPD or other mental health outcome, breast feeding or infant weight gain and (c) were conducted in LMICs by the World Bank definition.42 No inclusion criteria on the study sample’s characteristics were established for the selection of qualitative studies.

For both quantitative and qualitative studies, we did not impose any restrictions regarding the type of D&A, its operationalisation, definition or measurement tools for inclusion. Grey literature, opinion pieces and editorials, dissertations/theses, policy papers, general reports and conference abstracts were excluded. Studies were also excluded if they focused on people with disabilities, refugees or people from conflict-affected settings, or on women or newborns with severe health conditions that require specialised clinical care. Articles in English, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, Italian and French were included.

Data extraction and synthesis

The titles and abstracts retrieved were independently screened by two reviewers (NM, AGN). Unclear abstracts were carried forward to the screening stage. The full texts of potentially eligible articles were retrieved and screened against the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between reviewers. For both quantitative and qualitative studies, data were extracted on country, study design, sample size and characteristics of the sample (age, place of residence, occupation, gender/sex, education, socioeconomic status, marital status).

For quantitative studies, primary outcomes were extracted according to the type of abuse reported in the article, independently of whether it was aligned to existing D&A or MDC typologies. If the article reported the exposure in its positive form (such as privacy), it was converted to its negative form (ie, lack of privacy) to ensure consistency across the studies and facilitate interpretation of the review’s results. Measures of effects were also transformed to unadjusted ORs if reported differently to allow for comparison between studies (original effect size without transformation can be found in online supplemental appendix 5). A meta-analysis on the association between mistreatment and the main outcomes was not possible because of the small number of articles and large heterogeneity in the definition of both exposure and outcomes. Therefore, results were summarised descriptively. All calculations were done in the statistical software STATA V.14.

Qualitative studies were imported to the software NVivo V.12 for analysis. Articles were analysed using thematic synthesis.43 After becoming familiar with the data, two researchers (NM, AGN) independently coded the results section of each study, line by line, to inductively search for emerging themes. First, we identified codes that addressed the following research questions: (a) does D&A affect women’s decision to use PNC? and (b) does D&A affect other outcomes such as breast feeding, infant growth or women’s mental health? No studies were found to answer the latter question, so the analysis only focused on PNC use as an outcome. At this stage, specific codes related to disrespectful or abusive acts towards women emerged as enablers or deterrents of PNC use. During a second round of coding, we explored underlying mechanisms by which D&A could affect PNC use through the following question: ‘how does D&A relate to women’s decision to use PNC?’. This approach allowed us to detect broader factors linking D&A and PNC utilisation. Next, we grouped the codes identified into common descriptive themes. From this exercise, the final three themes emerged: (a) women’s direct experiences, (b) women’s expectations, (c) women’s agency.

Risk of bias (quality) assessment

For the quantitative studies, we used the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.44 The quality of qualitative studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme quality-assessment tool (http://www.casp-uk.net).45

Two reviewers independently assessed each study for quality and categorised the studies on ‘high’ (≥75% of applicable criteria), ‘medium’ (50–<75%) or ‘low’ (<50%) quality. Discussions were held to reach consensus (online supplemental appendices 2 and 3). Because there is no current consensus on the role of quality criteria and how it should be applied,46 no studies were excluded as a result of the quality assessment. The Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research approach was used to assess the confidence of the qualitative finding by assessing methodological limitations, relevance to the review question, coherence and adequacy of data.47 The confidence in the evidence was categorised as high, moderate and low.

Registrations and reporting

This systematic review is reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement guidelines48 and the ENTREQ statement guideline49 to enhance transparency in reporting quantitative and qualitative evidence synthesis. The protocol has been prospectively registered and published in PROSPERO: registration CRD42020208916.

Results

General overview

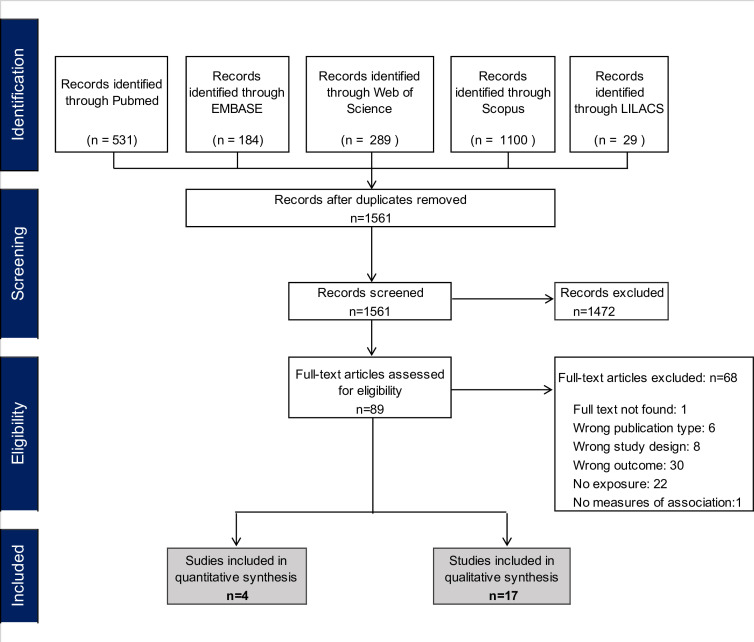

The Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, LILACS and Scopus searches yielded 2133 articles, of which 572 were duplicates. Full texts were assessed of 89 potentially eligible studies. The main reasons for exclusion are listed in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart of included studies.

After exclusions, 4 quantitative papers, 1 mixed-methods paper and 16 qualitative papers were included. Two quantitative studies evaluated the association of D&A with PNC use,50 51 one with breast feeding52 and one with maternal PPD.53 All included qualitative studies evaluated D&A in relation to access to PNC.15 54–69 Of all included studies, 16 were conducted in Africa, 2 in Latin America (Brazil) and 2 in Asia (China and Indonesia). A summary of the studies is presented in tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included quantitative studies

| Study | Country | Study aims | Participants’ characteristics | Sample size | Study design | Exposure definition | Exposure prevalence | Outcome measured | Outcome prevalence |

| Bishanga et al50 | Tanzania | To explore women’s experience of facility-based childbirth care, including D&A, choice of birth position, offer of a birth companion and perceived facility cleanliness. | Women aged 15–49 years who had given birth in health facilities during the 2 years preceding the survey. | 732 | Cross-sectional | Self-report of any of the following: left alone for a long period of time, left to deliver unassisted/alone, verbally abused, shared a bed with another person during labour, level of privacy, provided with no bed sheet, physical violence, inappropriate touching, discrimination, denied services, detained for payment, denied food/drink or care without consent. | 73.1% | PNC use—any healthcare services given to women or baby by a professional health worker at a health facility within 48 hours of delivery. | Early postnatal check for women: 339 (46.3%); early postnatal check for baby: 358 (51.4%). |

| Creanga et al51 | Malawi | To examine predictors of perinatal health service utilisation and to assess patient satisfaction with these services when last obtained. | Women aged 15–49 years who have given birth within the last 12 months and whose babies were alive at the time of the survey. | 1301 | Cross-sectional (baseline data from a cluster RCT) | Perceptions regarding the cleanliness of the facility, patients’ privacy, providers availability at the facility, quality of services offered, unmarried woman lack of access to services. Assessed by a 5-point agreement Likert scale. | Cleanliness: 3.5%; privacy: 6.7%; provider availability: 10.2%; low quality services: 10.9%; access to FP/RHs for unmarried women: 31.5%. | Maternal and neonatal PNC use—use after last delivery and number of checks within 2 months post partum. | 77.5% |

| Bandeira de Sá et al52 | Brazil | To identify factors associated with breast feeding in the first hour of life. | Mother–child pairs aged 0–12 months who attended health units. | 1027 | Cross-sectional | Self-report of any of the following during labour or delivery: physical violence (painful medical examination, being hit pushed or tied up), verbal violence (being yelled at), neglect (denial of care, fail to provide pain relief or lack on information about procedures), rooming in. | Verbal violence: 17.8%; physical violence: 17.3%; neglect: 16.7%; no rooming-in: 10.1%. | Child placed in the chest to breast feed in the first hour of life. | 77.3% |

| Silveira et al53 | Brazil | To examine the effect of the different types of disrespectful and abusive experiences on maternal postpartum depression occurrence and to explore if the associations differ according to women’s antenatal depressive symptoms status. | All women resident in the urban area, with confirmed pregnancy estimated delivery date in the year 2015. | 3065 | Cohort | Self-reported information on disrespect and abuse as any of the following: verbal abuse, denial of care (abandonment of care), physical abuse and undesired procedures (non-consented care) during the process of childbirth. | 18.0% (95% CI 16.7 to 19.4) |

Maternal postpartum depression- assessed by EPDS with cut-off of ≥13 points for moderate signs of depression and ≥15 points for severe signs of depression. | EPDS score ≥13: 9.4%; EPDS score ≥15: 5.7% |

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; FP, family planning services; PNC, postnatal care; RCT, Randomised controlled trial; RH, reproductive health services.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included qualitative studies

| Study | Country | Study aims | Participants’ characteristics | Study design and data collection | Aspects of D&A explored* |

| Chen et al54 | China | To explore coverage, quality of care, reasons for not receiving care and barriers to providing postnatal care after introduction of new policy. | Caregivers of children younger than 2 years of age and township maternal and child healthcare workers. | Mixed methods combining a quantitative household survey and qualitative semi-structured interviews. | Health system level issues such as workload, income and training. |

| Dol et al62 | Tanzania | To explore the experience of newborn care discharge education at a national hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania from the perspective of mothers and nurse midwives. | Mothers who recently gave birth at national hospital and nurse midwives working on the postnatal and labour ward. | Qualitative descriptive research using in-depth interviews. | Woman-provider communication, and social, institutional and cultural influences when providing care. |

| Ganle and Dery63 | Ghana | To explore the barriers to and opportunities for men’s involvement in maternal healthcare in the Upper West Region of Ghana. | Men and their spouses, community chiefs, women leaders, assembly men, community health nurses, community health officers and mother-to-mother support group leaders. | Qualitative focus group discussions, in-depth interviews and key informant interviews. | Challenges to male involvement in maternal healthcare, including institutional constraints and providers attitudes. |

| Kane et al64 | Sudan | To gain insight into what hinders women from using maternal health services. | Community members, traditional leaders and traditional birth attendants. | Qualitative focus group discussions and in-depth interviews. | Social fears, social expectations and social interactions. |

| Mahiti et al65 | Tanzania | To explore women’s views about the maternal health services (pregnancy, delivery and postpartum period) that they received at health facilities in rural Tanzania. | Women attending a health facility for vaccination at Kongwa District Hospital and Ugogoni Health Centre. | Qualitative focus group discussions and non-participant observation. | Women-provider interaction, waiting times, informal payments and material constraints (drug shortage and dirtiness). |

| McMahon et al66 | Tanzania | To explore how rural Tanzanian women and their male partners describe disrespect and abuse experienced during childbirth in facilities and how they respond to abuse in the short or long-term. | Women, male partners, community health workers (CHWs) and community leaders from eight health centres across four districts. | Qualitative, cross-sectional study using in-depth interviews. | Types of verbal and physical abuse, discriminatory treatment, unpredictable financial charges and fear of detention. |

| Melberg et al67 | Burkina Faso | To explore how communities in rural Burkina Faso perceive the promotion and delivery of facility pregnancy and birth care, and how this promotion influences health-seeking behaviour. | Women with recent health centre birth, women with a recent home birth, their partners and community men and women. | In-depth interviews and focus group discussions. | Fear of reprimands, economic sanctions, denial of care, stigma and discriminatory practices. |

| Mselle et al59 | Tanzania | To examine how postpartum care was delivered in three postnatal healthcare clinics in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. | Nurse-midwives and obstetricians from Dar es Salaam Referral Regional Hospitals. | Semi-structured interviews. | Relations of power among providers and women, focusing on beliefs, values, practices, language, meaning. |

| Morgan et al68 | Uganda | To understand the role of gender power relations in relation to access to resources, division of labour, social norms and decision-making affect maternal healthcare access and utilisation in Uganda. | Women who had given birth recently, fathers whose wives had given birth recently, and transport drivers. | Qualitative focus group discussions. | Access to resources, division of labour (including male involvement), and social norms (including health workers attitudes and behaviours). |

| Ochieng and Odhiambo69 | Kenya | To understand what factors are leading to low healthcare seeking during pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal period in Siaya County in Kenya. | Women attending ANC in Kenyan public primary healthcare facilities. | Qualitative focus group discussions. | Transportation issues, affordability, attitudes of health providers, embarrassment, autonomy in decision making, denial of care or punishment for delaying care. |

| Ongolly and Bukachi55 | Kenya | To explore the barriers to men’s involvement in antenatal and postnatal care in Butula subcounty, Western Kenya. | Married men of the Butula subcounty who had had children in the past 1 year and healthcare workers in charge of maternal health services. | Mixed methods using quantitative surveys, focus group discussions and key informant interviews. | Health systems barriers including long waiting limes, lack of privacy, infrastructure constraints and providers’ attitudes. |

| Probandari et al56 | Indonesia | To explore barriers to utilisation of postnatal care at the village level in Klaten district, Central Java Province, Indonesia. | Mothers with postnatal complications, family members and village midwives. | Qualitative data using in-depth interviews. | Suboptimal patient-centred care including lack of communication, availability of providers, insufficient time, inadequate education, selective care, cultural beliefs and practices, social power. |

| Sialubanje et al60 | Zambia | To identify psychosocial and environmental factors contributing to low utilisation of maternal healthcare services in Kalomo, Zambia. | Women of reproductive age (15–45 years) who gave birth within the last year, traditional leaders, mothers, fathers, community health workers and nurse-midwives. | Qualitative focus group discussions and in-depth interviews. | Provider’s attitude such as verbal abuse and health systems constraints. |

| Sacks et al15 | Uganda and Zambia | To examine experiences with, and barriers to, accessing postnatal care services in the context of a maternal health initiative. | Women who had delivered in the preceding year and lived within the eight districts. | Qualitative focus group discussions. | Fear of verbal or physical abuse, fear of denial of care or threat of denial of care, and neglect. |

| Yakong et al57 | Ghana | To describe rural women’s perspectives on their experiences in seeking reproductive care from professional nurses. | Women 15 and 49 years of age and who had received care from two rural clinics and clinic nurses and community-based surveillance volunteers. | Qualitative study with in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and participant observation. | Intimidation and verbal abuse, experiences of limited choices, of receiving silent treatment and of lack of privacy. |

| Yevoo et al58 | Ghana | To explore ‘how’ and ‘why’ pregnant women in Ghana control their past obstetric and reproductive information as they interact with providers at their first antenatal visit, and how this influences providers’ decision-making at the time and in subsequent care encounters. | Pregnant women who were within a gestational age of between 12 and 20 weeks and focus group discussions with pregnant and postnatal women. | Ethnographic study using participant observation, semi-structured interviews, and focus group discussions. | Healthcare providers’ ideological ‘domination and humiliation, including derogatory comments and verbal abuse, stigmatisation and discrimination, privacy and confidentiality. |

| Zamawe et al61 | Malawi | To examine the perceptions of parents toward the postpartum period and postnatal care in order to deepen the understanding of the maternal care-seeking practices after childbirth. | Women and men who had either given birth or fathered a baby within 12 months prior to the study (new parents). | Descriptive qualitative study using focus group discussions. | Health system constraints related to long waiting times, costs, distance. |

*The information presented in this column has been extracted during the initial coding phase of the qualitative analysis. No explicite conceptual definition of D&A was provided in most of the included studies.

D&A, disrespect and abuse.

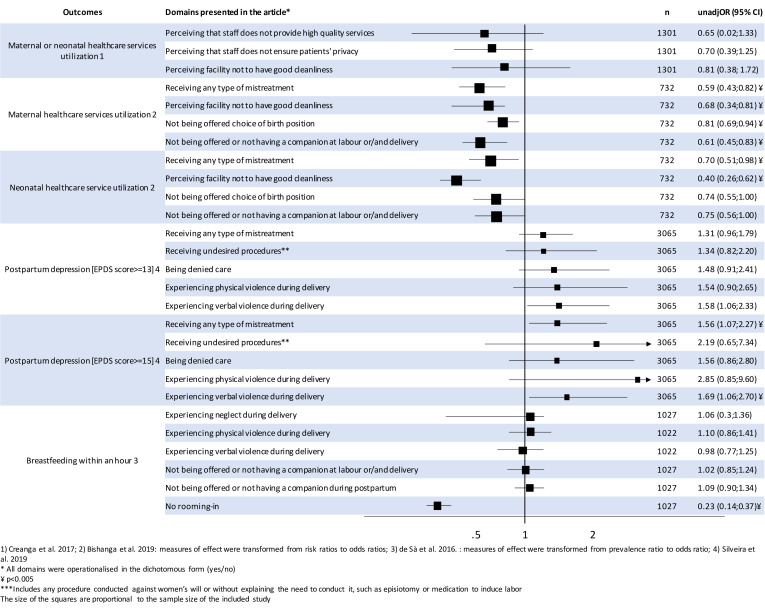

Quantitative synthesis of main outcomes

All quantitative studies defined D&A and the outcomes differently. Table 3 shows how the D&A domains extracted from the included studies relate to existing typologies of D&A and MDC. In this section, we present a narrative summary of the findings further illustrated in figure 2.

Table 3.

Categorisation of the domains of D&A extracted from included quantitative studies based on existing typologies

| Domains as extracted from article | Domains categorised based on D&A typology* | Domains categorised based on MDC typology† |

| Experiencing physical violence during deliveryठ| Physical abuse | Physical abuse |

| Experiencing verbal violence during delivery§ | Non-dignified care | Verbal abuse |

| Receiving undesired procedures§ | Failure to meet professional standards of care | |

| Being denied care§ | ||

| Experiencing neglect during delivery‡ | ||

| Perceiving that staff does not provide high quality services¶ | ||

| Not being offered choice of birth position** | Poor Rapport between women and providers | |

| Not being offered or not having a companion at labour or/and delivery**‡ | Abandonment of care | |

| Not being offered or not having a companion during post partum‡ | ||

| No rooming-in‡ | ||

| Perceiving that staff does not ensure patients’ privacy¶ | Non-confidential care | Health systems conditions and constraints |

| Perceiving facility not to have good cleanliness¶** | Non-apply | |

| Receiving any type of mistreatment**§ | Receiving any type of D&A **§ | Receiving any type of mistreatment**§ |

Figure 2.

Summary of quantitative findings of the association between different domains of disrespect and abuse and PNC utilisation, breastfeeding and postpartum depression. (1) Creanga et al;51 (2) Bishanga et al:50 measures of effect were transformed from risk ratios to ORs; (3) Bandeira de Sà et al:52 measures of effect were transformed from prevalence ratio to OR; (4) Silveira et al.53 *All domains were operationalised in the dichotomous form (yes/no). ¥p<0.005. ***Includes any procedure conducted against women’s will or without explaining the need to conduct it, such as episiotomy or medication to induce labour. EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

In the study by Bishanga et al,50 the 73.1% of women who reported experiencing at least one form of D&A had 41% lower odds of receiving an early postnatal check (unadjusted OR: 0.59, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.82) and 30% lower odds of their newborn receiving an early postnatal check (95% CI 0.51 to 0.98) compared with mothers who did not experience D&A. The study by Silveira et al53 reported that women who experienced any D&A during childbirth (18%) had 56% higher odds (unadjusted OR: 1.56; 95% CI 1.07 to 2.27) of developing severe PPD compared with those that did not experience D&A. When analysed by domain of D&A, Silveira et al showed that if the abuse was verbal, women had 69% greater odds (unadjusted OR: 1.69; 95% CI 1.06 to 2.70) of developing severe PPD, compared with those that did not experience verbal abuse. Bandeira de Sà et al52 found that keeping the baby in the same room as the mother after delivery was the only clinically or statistically significant predictor of breast feeding within 1 hour (unadjusted OR: 0.23; 95% CI 0.14 to 0.37) among those measured, however, the survey was conducted with mothers attending vaccination centres, and so the study population may have already self-selected as those with high levels of engagement. Additionally, Bishanga et al50 reported that women not offered a choice of birth position had 19% lower odds of a postnatal check (95% CI 0.69 to 0.94); and those who perceived the facility as not being clean had 32% (OR=0.68; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.81) and 60% lower odds (95% CI 0.26 to 0.62) of receiving a maternal early postnatal check and newborn early postnatal check, respectively.

Creanga et al51 found no statistical association at the 5% level between postnatal check and any of the domains measured. The authors stated that this may be explained by a widespread perception of poor quality of care by women participating in the study.

Qualitative synthesis of factors affecting PNC

The main objective of the qualitative analysis was to better understand if and how D&A and its underlying drivers affect the use of PNC. All included studies with a qualitative component described this relationship from different perspectives, however, no study had this as its primary research question. Six studies aimed to explore barriers to maternal and newborn health (MNH) care,15 54 56 60 64 69 five explored experience of MNH care,57 59 62 65 66 three evaluated perception of MNH care,58 61 67 two described male involvement in maternal and newborn care55 63 and one explored gender dynamics in care provision.68 The majority of the studies (15/17; 88%) were conducted in Africa (Burkina Faso,67 Ghana,57 58 63 Malawi,61 Kenya,55 69 Uganda,15 68 Sudan,64 Zambia15 and Tanzania59 62 65 66) while the remaining two were from Asia (China and Indonesia).54 56 While women direct experience of D&A during childbirth was identified as a factor influencing their decision to accessing care, two other themes emerged from the included studies to better explain the underlying factors driving such relationship. The assessment of confidence in the review findings showed high confidence in the theme related to women’s direct experience and low to moderate confidence in the remaining two themes (online supplemental appendix 4).

Theme 1: women’s direct experience

The first theme that appeared repeatedly was the effect of ‘women’s direct experience’, indicating that a previous negative interaction with a health provider could impact women’s subsequent care-seeking behaviour either by changing provider or by delaying or avoiding care altogether. This theme includes aspects related to health systems constraints and prior experiences of mistreatment.

Health systems constraints

Inadequate infrastructure and staff shortage contributed to the loss of trust in the maternal and neonatal services women received.54 59–61 63 65 Women frequently reported having to wait before receiving care, which resulted in a poor patient/client relation.61 Although in some of the included articles, women accepted the long waiting times as the result of a limited number of staff, in others they questioned the value of PNC as other issues were prioritised before theirs.54 55 61 Men and women used the long waiting time as an argument for lack of male involvement in MNH care, as men were frequently the ones in the paid workforce and often perceived themselves not to be ‘in a position to spend the day waiting for their wives to receive care’.63 65 Men also reported a shortage of waiting space for them as a reason for not participating in MNH care, often being asked to wait outside while women are were treated.

Women referred to facility cleanliness as another major deterrent for accessing PNC.59 65 They described labour wards as dirty and untidy, sometimes having to reuse dirty bed sheets or share a bed with other women, all of which impacts strongly on their confidence in the hygiene of the health facilities.

D&A during previous contacts with health system

Many women referred to their previous experience with the healthcare system as a barrier to PNC use.15 56–60 62 68 Women identified areas where they felt that nurses did not provide them with sufficient, clear or timely information about the postnatal period, including skin-to-skin contact, hygiene practices and positioning for breast feeding.62 In one article, they mentioned that education on postnatal practices was provided immediately after delivery when women were still in pain.56 Nurses-midwives also recognised their lack of time for providing health education to new mothers or even providing essential life-saving practices to mothers/newborns because of staff shortages.59

Another recurring theme that women mentioned as having profound effect on their health-seeking patterns was the lack of privacy during the visits.57 58 In some articles, women expressed concerns about sharing confidential information because they felt that other people could listen into their interactions with health providers and questioned healthcare providers’ ability to protect the confidentiality of the information they exchanged. Women recognised that these issues prevented them from discussing topics related to their reproductive health, contraceptive use or ill-health as they were afraid of negative repercussions on their relationship with family members or their husbands.

Many women and men identified rudeness and abusive behaviours by health workers as a key problem affecting access to and use of maternal and neonatal services.15 58 68 Women described nurses as ‘rude and harsh’, with many complaining about receiving ‘verbal abuse’, ‘condescension’ or ‘derogatory comments’.68 As described in a group discussion with young mothers: ‘the nurses beat you when you refuse to push’.58

Theme 2: women’s expectations

The second theme was ‘women’s expectations’, meaning the apprehension of attending facilities based on the fear of what is expected of them by the healthcare provider. As an example, this includes women’s sense that they could be shamed for the ill-health of their child or for not following the recommendations of health providers.

Internalised stigma

Women’s internalised stigma frequently appears as a deterrent to PNC use in the form of fear of repercussions and embarrassment.15 64 66–69 In some studies, women describe their fear of being detained at the health facility or ‘shamed and belittled’ for not having enough money to pay for services.68 Others were afraid of reprimand and embarrassment from health workers because they lacked proper baby clothing, and they believed that appearing dishevelled and uncared for gave an impression of not being celebrated and dignified by the family.64 66 Women also reported that if they failed to honour what the health provider expected of them, they would be made to wait, yelled at or criticised.64 However, these fears were most prominent among women who delivered at home.15

Women avoided accessing PNC in all these cases instead of confronting the health providers as they were afraid that they would be denied future care or services. Women described that they did not consider themselves competent enough to engage in open confrontation fearing they would have to seek care in another facility further away from their place of residence, which would impact on the cost and time to access healthcare when needed.69

Beliefs and traditions

Some women discussed differences between medical and traditional knowledge as major barriers for accessing the postnatal clinic.56 62 69 The lack of culturally sensitive care during childbirth, the ineffective communication, and the dismissal of traditional practices and beliefs led to women avoiding access to subsequent care. Women reported unwanted medical interventions as a reason for not attending PNC, with vaccine hesitancy due to the fear that an injection could harm the child as one of the main concerns for avoiding PNC.

Theme 3: women’s agency

The last analytical theme was ‘women’s agency’ referring to larger societal or familial influences that diminishe women’s decision-making power, a consequence of health systems failures and ineffective education opportunities after childbirth.

Male involvement and gender dynamics

The lack of participation of men in maternity care was described in many studies as a healthcare system’s failure to actively engage men on issues of maternal health, with many men reporting negative attitudes from health workers when trying to get involved in the childbirth experience.55 59 63 68 While some healthcare workers agreed that family members needed to be included in post-delivery education, they often mentioned restrictions on this practice due to space constraints or other infrastructural issues.59 This, in conjunction with traditional gender norms and cultural beliefs, led to most men perceiving maternal and newborn care as a ‘feminine’ domain, disengaging themselves from the process of care.59 63 68

Both men and women acknowledged that, even if healthcare is perceived as the responsibility of the woman, men still exercised their power by either permitting or restricting women’s access to services, through financial control or other forms of domestic violence.55 63 68 Thus, women avoided PNC as any delay that prevented them from performing their household chores or accepting care practices condemned by their partner, could potentially trigger episodes of domestic violence.

Family and societal influence (social norms)

The suboptimal provision of education on PNC after facility childbirth made women less prepared to confront external family and societal influences after discharged.56 59 62 69 Midwives reported not having adequate time to build a trusting relationship with women to discuss issues related to postpartum care because of staff shortages or space constraints, while women claimed they did not understand midwives’ instructions on how to care for the baby as they rushed through it and used high-manner language.62

The lack of preparation for the postnatal period meant that many women, especially those who share homes with their extended family (such as their in-laws or their grandparents), were more likely to follow culture-related myths and rules passed by their relatives. 56 59 69 Women recognised they were expected to obey traditional family rules rather than acting on any teaching provided at the hospital.56 Thus, they would refrain from accessing PNC due to fear of repercussions for not following providers’ instructions during previous contact.

Although this theme appeared less frequently across articles, health providers recognised the cultural beliefs and traditional practices regarding healthcare in their communities and mentioned that they try to discuss this issue with women. However, they acknowledged that family and society’s influences are particularly strong during the postnatal stage.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to understand how and why the experience that women and newborns have during childbirth can impact on their relationship with the healthcare system and on their health and well-being. Different domains of D&A were associated with poorer engagement with early maternal care, early neonatal care and PPD; the only domain associated with breast feeding was rooming-in, as mothers and babies are kept together promoting opportunities of contact. Although there is currently a paucity of high-quality quantitative evidence and lack of consistency in the measurement of the exposure, the themes that emerged from the qualitative studies could indicate different pathways by which these associations could hold true. These pathways reflect multiple interrelated influences that guide women to access and use PNC, and subsequently impact on their health and that of their newborn.

Echoing our quantitative results, the qualitative findings suggest that the quality of medical care received by women directly influences women’s healthcare seeking behaviours. As evidence shows that a negative experience during antepartum care is a barrier to facility-based childbirth,5 a negative experience during facility-based childbirth can also influence the decision to seek care postnatally. Despite interpersonal factors being the most prominent contributors to a negative experience of care across the identified literature, system level conditions also play a crucial role. Health system constraints, such as staff shortages and lack of cleanliness, often associated with longer waiting times and poorer quality of care, can create an environment in which women feel unwelcome and discouraged to return for future visits. However, the disrespectful or abusive treatment received by women, including health system constrains, appear not to be sufficient to solely explain the potential impact on PNC use.

Our findings show that women’s decision-making process on PNC seeking originates from a complex intersection of factors, both from within and outside the healthcare realm. It is influenced by broader cultural, social and gender norms that reify women’s vulnerabilities within society, not only as part of their direct experience with healthcare. The most disenfranchised women are more likely to avoid institutional healthcare as another place where they might feel disempowered, a consequence of their ‘internalised stigma’, and systemic disadvantages. This aligns with Dixon-Woods concept of ‘candidacy’ to describe inequity of access to health services and health outcomes.70 Candidacy suggests that an individual’s identification of his or her ‘legitimacy’ for health services is structurally, culturally, organisationally and professionally construed; with a range of characteristics, such as gender, poverty, education, age and ethnicity coalescing to suppress the use of services.71 This combination of systemic disadvantages can reduce women’s agency, diminish her candidacy and compromise her access to healthcare.72 This might partially explain why, even in settings with universal healthcare provision, those in deprived circumstances make less use of services than the more affluent.

Our findings constitute the initial necessary steps to bring clarity on D&A as a possible barrier to care and to women and newborn’s health and well-being. This review highlighted several gaps of knowledge in the current literature. The most prominent one comes from the methodological challenges in quantifying and comparing the prevalence of D&A and its impacts across studies and settings, as no unique definition was used. In recent years, efforts have been made to develop universal evidence-based definitions, typologies and measurement tools.73–75 The widespread adoption of these tools could allow for a better harmonisation of measures in future studies. Moving forward, we need to be strategic in addressing the difficulties attached to such a complex phenomenon. More research is needed to develop and evaluate interventions to tackle the structural drivers sustaining D&A, such as damaging gender norms, social inequalities and asymmetric power distributions that promote the normalisation of poor treatment. Alongside this, we need measurable objectives that are attainable in the short term and help move us towards those broader systemic changes. Understanding the immediate health benefit of providing respectful maternity and newborn care can be a first strategic step to encourage health workers to equate the value of non-clinical aspects of care to that of high-quality, evidence-based clinical practices. In this review, we selected specific public health outcomes that can bring a new perspective to tackling this issue and can contribute to designing custom-made messages to address front-line stakeholders. We highlight the need for primary research to robustly measure the health and well-being impact of D&A in order to quantify and monitor progress as interventions are put in place.

Limitations and strength of the review

While some of the cross-sectional studies show preliminary evidence of a possible relation between D&A during childbirth with PNC utilisation and maternal mental health, the results come from small scale studies with a low prevalence of the exposure and provide inconclusive evidence. The low prevalence could be explained by recall or social desirability biases as studies required women to remember what happened during childbirth or were conducted within hospital settings. Additionally, the confidence in the qualitative evidence related to broader cultural and societal themes was low to moderate, highlighting the need to further study how structural aspects interplay with D&A and PNC. Further, the definitions of D&A and outcomes differed between studies making cross-study comparisons challenging. Thus, the potential for the complementarity of quantitative and qualitative methods for synthesising data could not be fully exploited. Finally, the limited number of studies from Asia and Latin America relative to Africa could be affecting generalisability.

There are several strengths to this review as it is, to our knowledge, the first to summarise the consequences of D&A during childbirth. The use of mixed methods allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the available evidence, integrating the measurement of the effect size of the association with the identification of broader factors that interact to bring about such effect. Following a systematic process for the screening, inclusion and analysis of the retrieved articles, this review shows reliable and transparent results that highlight the need for further research in this field.

Conclusion

Women’s access to PNC can be influenced by a myriad of factors with long lasting effects on her health and her newborn’s. In the quest to improve women and newborns’ health and guarantee access to high-quality, respectful, dignified and supportive care, understanding the consequences of a negative birth experience can provide a step forward in prioritising the problem. While a complex, systemic and multidimensional response is needed, it might take longer to materialise and will require buy-in from multiple stakeholders. This review aims to offers a new perspective to the issue of D&A and calls on the public health community to urgently address D&A during facility-based childbirth for the sake of its potentially damaging health consequences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Ann G Nicholson and Dr Vanessa Brizuela for providing support and collaboration during the development of the review.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @nminckas, @LuGram12, @jvmannell

Contributors: NM conceived the study, conducted the search, analysed the data and wrote the first manuscript with input from JM, CS and LG. All authors interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: During the development of this study, Nicole Minckas was supported by the UK Economic and Social Research Council through an UBEL DTP grant.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of UK ESRC, or other institutions with whom the authors are affiliated.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon request. Data analysed in the current study will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.WHO, UNICEF . Building a future for women and children - the 2012 report, 2012. Available: http://www.countdown2015mnch.org/ [Accessed 23 Oct 2020].

- 2.United Nations . The millennium development goals report, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth report of a landscape analysis. USAid traction project. Harvard school of public health university, 2010. Available: http://www.urc-chs.com/uploads/resourceFiles/Live/RespectfulCareatBirth9-20-101Final.pdf [Accessed 12 Jan 2021].

- 4.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med 2015;12:1–32. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohren MA, Hunter EC, Munthe-Kaas HM, et al. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health 2014;11:71. 10.1186/1742-4755-11-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman LP, Ramsey K, Abuya T, et al. Defining disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth: a research, policy and rights agenda. Bull World Health Organ 2014;92:915–7. 10.2471/BLT.14.137869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyaddondo D, Mugerwa K, Byamugisha J, et al. Expectations and needs of Ugandan women for improved quality of childbirth care in health facilities: a qualitative study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2017;139:38–46. 10.1002/ijgo.12405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohren MA, Mehrtash H, Fawole B, et al. How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: a cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys. Lancet 2019;394:1750–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31992-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afulani PA, Sayi TS, Montagu D. Predictors of person-centered maternity care: the role of socioeconomic status, empowerment, and facility type. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:360. 10.1186/s12913-018-3183-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Tunçalp Özge, et al. "By slapping their laps, the patient will know that you truly care for her": A qualitative study on social norms and acceptability of the mistreatment of women during childbirth in Abuja, Nigeria. SSM Popul Health 2016;2:640–55. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balde MD, Bangoura A, Diallo BA, et al. A qualitative study of women's and health providers' attitudes and acceptability of mistreatment during childbirth in health facilities in guinea. Reprod Health 2017;14:4. 10.1186/s12978-016-0262-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maya ET, Adu-Bonsaffoh K, Dako-Gyeke P, et al. Women's perspectives of mistreatment during childbirth at health facilities in Ghana: findings from a qualitative study. Reprod Health Matters 2018;26:70–87. 10.1080/09688080.2018.1502020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sando D, Ratcliffe H, McDonald K, et al. The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:1–10. 10.1186/s12884-016-1019-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afulani PA, Phillips B, Aborigo RA, et al. Person-centred maternity care in low-income and middle-income countries: analysis of data from Kenya, Ghana, and India. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e96–109. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30403-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sacks E, Masvawure TB, Atuyambe LM, et al. Postnatal care experiences and barriers to care utilization for Home- and Facility-Delivered newborns in Uganda and Zambia. Matern Child Health J 2017;21:599–606. 10.1007/s10995-016-2144-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sacks E, Langlois Étienne V. Postnatal care: increasing coverage, equity, and quality. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e442–3. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30092-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Countdown 2030 . Women's, children's and adolescents's health. Available: http://countdown2030.org/ [Accessed 11 Feb 2020].

- 18.Waiswa P, Kallander K, Peterson S, et al. Using the three delays model to understand why newborn babies die in eastern Uganda. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:964–72. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02557.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Helth Organization . Postnatal care of the mother and newborn, 2013. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/97603/1/9789241506649_eng.pdf [Accessed 23 Oct 2020]. [PubMed]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) . Postnatal care up to 8 weeks after birth, 2015. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/ [Accessed 23 Oct 2020]. [PubMed]

- 21.Thompson JF, Roberts CL, Currie M, et al. Prevalence and persistence of health problems after childbirth: associations with parity and method of birth. Birth 2002;29:83–94. 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowlands IJ, Redshaw M. Mode of birth and women's psychological and physical wellbeing in the postnatal period. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:138. 10.1186/1471-2393-12-138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leeman L, Fullilove AM, Borders N, et al. Postpartum perineal pain in a low episiotomy setting: association with severity of genital trauma, labor care, and birth variables. Birth 2009;36:283–8. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00355.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.East CE, Sherburn M, Nagle C, et al. Perineal pain following childbirth: prevalence, effects on postnatal recovery and analgesia usage. Midwifery 2012;28:93–7. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mason L, Glenn S, Walton I, et al. The experience of stress incontinence after childbirth. Birth 1999;26:164–71. 10.1046/j.1523-536x.1999.00164.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schytt E, Lindmark G, Waldenström U. Symptoms of stress incontinence 1 year after childbirth: prevalence and predictors in a national Swedish sample. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2004;83:928–36. 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hannestad YS, et al. Urinary incontinence after vaginal delivery or cesarean section. N Engl J Med 2003;348:900–7. 10.1056/NEJMoa021788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson KT, Mantler T, OʼKeefe-McCarthy S. Women's experiences of breastfeeding-related pain. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2019;44:66–72. 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooklin AR, Amir LH, Nguyen CD, et al. Physical health, breastfeeding problems and maternal mood in the early postpartum: a prospective cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2018;21:365–74. 10.1007/s00737-017-0805-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooke M, Sheehan A, Schmied V. A description of the relationship between breastfeeding experiences, breastfeeding satisfaction, and weaning in the first 3 months after birth. J Hum Lact 2003;19:145–56. 10.1177/0890334403252472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shorey S, Chee CYI, Ng ED, et al. Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2018;104:235–48. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayers S, McKenzie-McHarg K, Slade P. Post-traumatic stress disorder after birth. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2015;33:215–8. 10.1080/02646838.2015.1030250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreno DH, Bio DS, Petresco S, et al. Burden of maternal bipolar disorder on at-risk offspring: a controlled study on family planning and maternal care. J Affect Disord 2012;143:172–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wisner KL, Perel JM, Peindl KS, et al. Timing of depression recurrence in the first year after birth. J Affect Disord 2004;78:249–52. 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00305-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pearlstein T, Howard M, Salisbury A, et al. Postpartum depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;200:357–64. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.11.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, et al. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet 2016;387:587–603. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00837-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slomian J, Honvo G, Emonts P, et al. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health 2019;15:174550651984404. 10.1177/1745506519844044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xie R-H, He G, Koszycki D, et al. Prenatal social support, postnatal social support, and postpartum depression. Ann Epidemiol 2009;19:637–43. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Higgins M, Roberts ISJ, Glover V, et al. Mother-child bonding at 1 year; associations with symptoms of postnatal depression and bonding in the first few weeks. Arch Womens Ment Health 2013;16:381–9. 10.1007/s00737-013-0354-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sines BE, Syed U, Wall S. Postnatal care: a critical opportunity to save mothers and newborns. Policy Perspect Newborn Heal 2007;18:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noyes J, Booth A, Moore G, et al. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform guidelines on complex interventions: Clarifying the purposes, designs and outlining some methods. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:893. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Bank . New country classifications by income level: 2019-2020. Available: https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2019-2020 [Accessed 9 Jul 2020].

- 43.Heyvaert M, Hannes K, Onghena P. Using mixed methods research synthesis for literature reviews. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute . Study quality assessment tools, 2014. Available: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools [Accessed 23 Oct 2020].

- 45.CASP . Critical appraisal skills programme. Available: http://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8

- 46.Atkins S, Lewin S, Smith H, et al. Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: lessons learnt. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:1–10. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.GRADE . GRADE-CERQual. Available: https://www.cerqual.org/ [Accessed 15 Jul 2020].

- 48.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:181. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bishanga D, Massenga J, Mwanamsangu A, et al. Women’s experience of facility-based childbirth care and receipt of an early postnatal check for herself and her newborn in Northwestern Tanzania. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:481. 10.3390/ijerph16030481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Creanga AA, Gullo S, Kuhlmann AKS, et al. Is quality of care a key predictor of perinatal health care utilization and patient satisfaction in Malawi? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:150. 10.1186/s12884-017-1331-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bandeira de Sá NN, Gubert MB, Santos WD, dos Santos W, et al. Factors related to health services determine breastfeeding within one hour of birth in the federal district of Brazil, 2011. Rev Bras Epidemiol 2016;19:509–24. 10.1590/1980-5497201600030004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silveira MF, Mesenburg MA, Bertoldi AD, et al. The association between disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth and postpartum depression: findings from the 2015 Pelotas birth cohort study. J Affect Disord 2019;256:441–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen L, Qiong W, van Velthoven MH, et al. Coverage, quality of and barriers to postnatal care in rural Hebei, China: a mixed method study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:31. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ongolly FK, Bukachi SA. Barriers to men’s involvement in antenatal and postnatal care in Butula, western Kenya. African J Prim Heal Care Fam Med 2019;11:a1911. 10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Probandari A, Arcita A, Kothijah K, et al. Barriers to utilization of postnatal care at village level in Klaten district, central Java Province, Indonesia. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:541. 10.1186/s12913-017-2490-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yakong VN, Rush KL, Bassett-Smith J, et al. Women's experiences of seeking reproductive health care in rural Ghana: challenges for maternal health service utilization. J Adv Nurs 2010;66:2431–41. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yevoo LL, Agyepong IA, Gerrits T, et al. Mothers' reproductive and medical history misinformation practices as strategies against healthcare providers' domination and humiliation in maternal care decision-making interactions: an ethnographic study in southern Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:274. 10.1186/s12884-018-1916-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mselle LT, Aston M, Kohi TW, et al. The challenges of providing postpartum education in Dar ES Salaam, Tanzania: narratives of nurse-midwives and obstetricians. Qual Health Res 2017;27:1792–803. 10.1177/1049732317717695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sialubanje C, Massar K, Hamer DH, et al. Understanding the psychosocial and environmental factors and barriers affecting utilization of maternal healthcare services in Kalomo, Zambia: a qualitative study. Health Educ Res 2014;29:521–32. 10.1093/her/cyu011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zamawe CF, Masache GC, Dube AN. The role of the parents' perception of the postpartum period and knowledge of maternal mortality in uptake of postnatal care: a qualitative exploration in Malawi. Int J Womens Health 2015;7:587–94. 10.2147/IJWH.S83228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dol J, Kohi T, Campbell-Yeo M, et al. Exploring maternal postnatal newborn care postnatal discharge education in Dar ES Salaam, Tanzania: barriers, facilitators and opportunities. Midwifery 2019;77:137–43. 10.1016/j.midw.2019.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ganle JK, Dery I. 'What men don't know can hurt women's health': a qualitative study of the barriers to and opportunities for men's involvement in maternal healthcare in Ghana. Reprod Health 2015;12:93. 10.1186/s12978-015-0083-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kane S, Rial M, Kok M, et al. Too afraid to go: fears of dignity violations as reasons for non-use of maternal health services in South Sudan. Reprod Health 2018;15:51. 10.1186/s12978-018-0487-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mahiti GR, Mkoka DA, Kiwara AD, et al. Women's perceptions of antenatal, delivery, and postpartum services in rural Tanzania. Glob Health Action 2015;8:28567. 10.3402/gha.v8.28567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McMahon SA, George AS, Chebet JJ, et al. Experiences of and responses to disrespectful maternity care and abuse during childbirth; a qualitative study with women and men in Morogoro region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:268. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Melberg A, Diallo AH, Ruano AL, et al. Reflections on the unintended consequences of the promotion of institutional pregnancy and birth care in Burkina Faso. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156503. 10.1371/journal.pone.0156503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Morgan R, Tetui M, Muhumuza Kananura R, Kananura RM, et al. Gender dynamics affecting maternal health and health care access and use in Uganda. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:v13–21. 10.1093/heapol/czx011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ochieng CA, Odhiambo AS. Barriers to formal health care seeking during pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal period: a qualitative study in Siaya County in rural Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:339. 10.1186/s12884-019-2485-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:35. 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mackenzie M, Conway E, Hastings A, et al. Is ‘Candidacy’ a useful concept for understanding journeys through public services? A critical interpretive literature synthesis. Soc Policy Adm 2013;47:806–25. 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00864.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kovandžić M, Chew-Graham C, Reeve J, et al. Access to primary mental health care for hard-to-reach groups: from 'silent suffering' to 'making it work'. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:763–72. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Fawole B, et al. Methodological development of tools to measure how women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: labor observation and community survey. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:132. 10.1186/s12874-018-0603-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Greco G, Skordis-Worrall J, Mills A. Development, validity, and reliability of the women's capabilities index. J Human Dev Capabil 2018;19:271–88. 10.1080/19452829.2017.1422704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Medvedev MM, Tumukunde V, Mambule I, et al. Operationalising kangaroo mother care before stabilisation amongst low birth weight neonates in Africa (OMWaNA): protocol for a randomised controlled trial to examine mortality impact in Uganda. Trials 2020;21:126. 10.1186/s13063-019-4044-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2020-004698supp001.pdf (402KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request. Data analysed in the current study will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.