Abstract

A 51-year-old woman presented with a 4-month history of painful ulcers in the mouth and vulva, and painful vegetative plaques at intertriginous sites. Skin biopsies showed squamous hyperplasia and intraepidermal eosinophilic pustulation. Skin direct immunofluorescence (DIF) revealed intercellular deposition of IgG and C3 in the lower part of the epidermis, while serum indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) confirmed the presence of antiepithelial antibodies. The patient was diagnosed with pemphigus vegetans, and successfully treated with dapsone, prednisolone and topical steroids. Although pemphigus vegetans and pyostomatitis-pyodermatitis vegetans can show identical clinical and histological features, the presence or absence of comorbid inflammatory bowel disease, and the results of both skin DIF and serum IIF can be used to distinguish between these two conditions. This case report explores the challenges in making this distinction, and the implications of establishing the correct diagnosis.

Keywords: dermatology, pathology, gastroenterology

Background

Pemphigus vegetans, a variant of pemphigus vulgaris, is a rare immunobullous disorder associated with autoantibodies directed against cell adhesion molecules in the epidermis, in particular desmoglein 3 ± desmoglein 1.1 Pyostomatitis-pyodermatitis vegetans (PPV) is a rare inflammatory disease with a strong association with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).2 Pemphigus vegetans and PPV can show identical clinical and histological features, however, the presence or absence of comorbid IBD, and the results of skin direct immunofluorescence (DIF) and serum indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) can assist in distinguishing between these two conditions. Resolving this differential diagnosis is important because of the strong association between PPV and IBD.

Case presentation

A 51-year-old woman presented to her private dermatologist with a 4-month history of painful ulcers involving her mouth and vulva, and painful skin lesions affecting scalp, axillary, intermammary, periumbilical and inguinal sites. She also reported pain and discomfort when eating and swallowing food, indicating possible oropharyngeal and/or oesophageal involvement. Of note, she had no other gastrointestinal symptoms, and no personal or family history of IBD. It was also relevant to note that she had no history of haematolymphoid or other malignant disease. Her medical history included hypercholesterolaemia, and she was on no regular medication. Examination showed extensive ulceration of the lips (figure 1), buccal mucosa and palatal mucosa, and similar ulceration was noted at the vulva. There was no involvement of the ocular mucous membranes. The skin was affected by vegetative plaques at the scalp and intertriginous sites. These plaques had a pustular quality, and some showed superficial erosion and crusting (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Extensive, circumferential ulceration of the upper and lower mucosal lip.

Figure 2.

Right axilla, showing vegetative and crusted plaques.

Figure 3.

Left inguinal region, showing erosive pustular plaques, and a discrete pustule.

Investigations

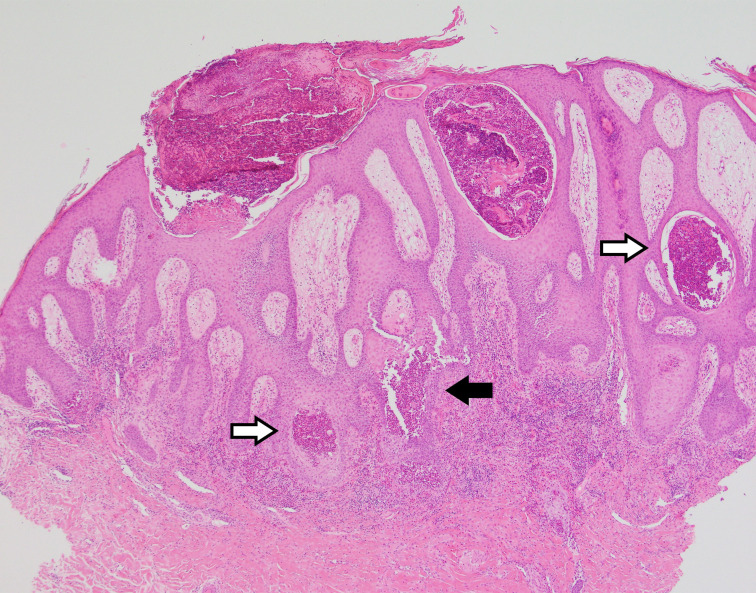

Skin biopsies were taken from representative lesions in the axilla for histological assessment, along with a biopsy of perilesional skin for DIF. Histological assessment showed squamous hyperplasia, spongiosis, and exocytosis of neutrophils and eosinophils with focal pustule formation (figure 4). Acantholysis was noted, but this was not a prominent feature. This biopsy was an elegant example of how the clinical morphology of a lesion can correlate with its histological features. The squamous hyperplasia accounted for the thickened and vegetative nature of these lesions, while the aggregated neutrophils and eosinophils in the epidermis accounted for the discoloured yellow and pustular appearance noted in areas. If acantholysis was a more prominent feature, one might have expected a more conspicuous vesicular or bullous presentation.

Figure 4.

Skin biopsy (H&E, low power) showing squamous hyperplasia, eosinophilic pustulation (white arrows) and focal acantholysis (black arrow).

DIF showed intercellular deposition of IgG and C3 in the lower part of the epidermis, imparting a so-called ‘chicken wire’ appearance (figure 5), whereas IgA was negative. This result made an immune-mediated disorder more likely, and while positive DIF can be seen in other disorders (including PPV), the pattern of staining in such cases tends to be non-specific in nature, and is thought to be a reactive (rather than immune-mediated) phenomenon.2 To support the DIF findings reported in this case, serum IIF was requested, confirming the presence of antiepithelial skin autoantibodies (pemphigus antibodies) with a high titre at 1:5120.

Figure 5.

Direct immunofluorescence showing intercellular deposition of C3 in the lower part of the epidermis.

Crohn’s disease can cause oral mucosal ulceration, and because this is characterised by the presence of granulomatous inflammation,3 an oral biopsy could have been considered. The potential utility of endoscopy–colonoscopy to exclude disease elsewhere in the gastrointestinal tract was considered, however, in consultation with the patient who reported no abdominal pain or diarrhoea, this was not pursued further.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for mucosal erosion or ulceration and vegetative plaques at intertriginous sites includes pemphigus vegetans and PPV. In this case, the differential diagnosis also included other entities in the pemphigus group, in particular, IgA pemphigus on account of a flexural distribution and pustular morphology, and paraneoplastic pemphigus in the setting of significant mucous membrane involvement.

The absence of IgA deposition on DIF excluded a diagnosis of IgA pemphigus. Furthermore, the patient had no history of haematolymphoid or other malignant disease, and the absence of both keratinocyte necrosis and an interface reaction was against a diagnosis of paraneoplastic pemphigus.3

In distinguishing between pemphigus vegetans and PPV, it was pertinent to note that apart from pain when eating and swallowing food which was attributed to her mucocutaneous disease, she had no gastrointestinal symptoms, and no personal or family history of IBD. The overall combination of clinical and pathological features including the results of DIF showing intercellular deposition of IgG and C3, and IIF confirming the presence of pemphigus antibodies, was used to substantiate a diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans.

Treatment

The patient was initially treated with topical betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% ointment in optimised vehicle to all affected areas two times per day. One week later, after the diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans had been confirmed, this was supplemented with prednisolone 75 mg/day (approximately 1 mg/kg) and dapsone 100 mg/day.

Outcome and follow-up

Rapid improvement was noted in response to treatment. After 2 weeks, her cutaneous and vulval lesions had healed. Her oral lesions took longer to resolve, but had completely healed at 3 months. At 6 months, she had a small flare with new mouth lesions. This occurred while tapering her prednisolone dose, and was successfully managed by increasing her dapsone dose and adding topical triamcinolone. After 11 months of treatment, prednisolone was successfully weaned. Since then, her dapsone dose has been reduced incrementally. At the time of publication, her dapsone dose was 25 mg/day.

The patient first presented over 3 years ago. Since her flare at 6 months, her skin has remained in remission. She has not developed gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain or diarrhoea, and the clinical suspicion for IBD remains low. Follow-up is ongoing.

Discussion

Pemphigus vegetans is a variant of pemphigus vulgaris, a rare immunobullous disorder due to pathogenic autoantibodies against keratinocyte desmosomes, in particular, targeting desmoglein 3±desmoglein 1. Most cases develop in middle aged adults. The disease has a predilection for the mouth, scalp and intertriginous sites, and is characterised by mucosal erosion or ulceration and pustular and vegetative plaques. Two phenotypes have been described: Neumann type, where lesions begin as flaccid bullae similar to pemphigus vulgaris and Hallopeau type, where vegetative plaques arise de novo.2 3

PPV is a rare reactive or inflammatory disorder with a strong association with IBD. The diagnostic label given to a patient includes pyostomatitis if there is oral involvement, and pyodermatitis if there is cutaneous involvement. Most cases arise in young to middle aged adults. While the presence of numerous clustered erosions or pustules with a so-called ‘snail trail’ appearance at mucosal sites has been described as a morphological clue to PPV,4–6 the mucous membrane and cutaneous features of PPV are otherwise similar to pemphigus vulgaris in terms of distribution and morphology.

The strong association between PPV and IBD is important for two main reasons. First, if a patient is known to have IBD, this would add support to a diagnosis of PPV. In a recent review of 38 cases of PPV by Gheisari et al, 65% of cases were associated with IBD.2 Second, PPV can be a marker of occult IBD,7 8 or presage the development of IBD.9 10 As such, it is important to identify cases of PPV so that patients can be monitored for the development of gastrointestinal disease.

As a general rule, both direct and indirect immunofluorescence are positive in pemphigus vegetans and negative in PPV, however, there are multiple recent reports of PPV with positive DIF and IIF.11 12 Gheisari et al included 32 cases where DIF had been performed, and 11 where IIF had been performed. DIF was positive in 12 of 32 cases, and several staining patterns were described. Intercellular IgG and C3—the pattern usually associated with pemphigus vegetans—was reported in 3 of 32 cases. IIF was positive for antiepithelial antibodies in 5 of 11 cases.2

First-line and second-line treatment for pemphigus vegetans and PPV are similar, including topical and systemic steroids, and immunosuppressive agents. In addition, dapsone is regarded as a first line oral medication in pemphigus vulgaris (and by extension, pemphigus vegetans).13 It is interesting to note that in patients with both PPV and IBD, cutaneous and gastrointestinal disease activity tend to parallel one another.2

Learning points.

Pemphigus vegetans and pyostomatitis-pyodermatitis vegetans (PPV) can show identical clinical and histological features.

A history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) favours a diagnosis of PPV. However, even in patients with no known history of IBD, it is important to consider a diagnosis of PPV, because it can be a marker of occult IBD, or presage the development of IBD.

Direct immunofluorescence showing intercellular deposition of IgG and C3 and indirect immunofluorescence demonstrating antiepithelial antibodies (pemphigus antibodies) favour pemphigus vegetans, with some exceptions.

Footnotes

Contributors: The case report was prepared by BS, with supervision from SS and AS. The patient’s dermatological condition is managed by SS, and the diagnosis was established in consultation with AS.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Amagai M. Chapter 29, Pemphigus. : Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, . Dermatology. 4th edn. London: Elsevier, 2017: 494–509. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gheisari M, Zerehpoosh FB, Zaresharifi S. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans: a case report and review of literature. Dermatol Online J 2020;26. [Epub ahead of print: 15 May 2020] https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5871q750 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ. Chapter 5, Acantholytic disorders. : McKee’s pathology of the skin with clinical correlations. 5th edn. London: Elsevier, 2019: 171–200. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehravaran M, Kemény L, Husz S, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. Br J Dermatol 1997;137:266–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18181914.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegarty AM, Barrett AW, Scully C. Pyostomatitis vegetans. Clin Exp Dermatol 2004;29:1–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ko H-C, Jung D-S, Jwa S-W, et al. Two cases of pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. J Dermatol 2009;36:293–7. 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00641.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markiewicz M, Suresh L, Margarone J, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans: a clinical marker of silent ulcerative colitis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007;65:346–8. 10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodd EM, Howard JR, Dulaney ED, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans associated with asymptomatic inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Dermatol 2017;56:1457–9. 10.1111/ijd.13640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storwick GS, Prihoda MB, Fulton RJ. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans: a specific marker for IBD. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;31:336–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wray D. Pyostomatitis vegetans. Br Dent J 1984;157:316–8. 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abellaneda C, Mascaró JM, Vázquez MG, et al. All that glitters is not pemphigus: Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans misdiagnosed as IgA pemphigus for 8 years. Am J Dermatopathol 2011;33:e1–6. 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181d81ecb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark LG, Tolkachjov SN, Bridges AG, et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans (PSV)-pyodermatitis vegetans (PDV): A clinicopathologic study of 7 cases at a tertiary referral center. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;75:578–84. 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeh SW, Sami N, Ahmed RA. Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris: current and emerging options. Am J Clin Dermatol 2005;6:327–42. 10.2165/00128071-200506050-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]