Abstract

A 38-year-old man presented with mild blurring of vision in both eyes for the past 1 week. On examination, the retinal vessels were dilated and tortuous, along with multiple dot blot haemorrhages all over the fundus with yellowish white focal retinal infiltrates at the macula temporal to the fovea. The salmon pink discolouration of the blood column made us look at the peripheral blood smear, which was suggestive of chronic myeloid leukaemia, leading to a diagnosis of leukaemic retinopathy in both the eyes.

Keywords: retina, macula

Background

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) is a clonal haematopoietic disorder. Reciprocal translocation between chromosome 9 and 22 resulting in Breakpoint cluster-Abelson 1 (Bcr-Abl 1) fusion gene is characteristically seen in CML.1 It can affect many organs in the body, including the eye. Sometimes, the ocular symptoms and signs are non-specific and could be the first and only manifestation of the underlying haematological malignancy. Failure to recognise this could cause an unnecessary delay in the diagnosis of a potentially serious systemic disorder.

Case presentation

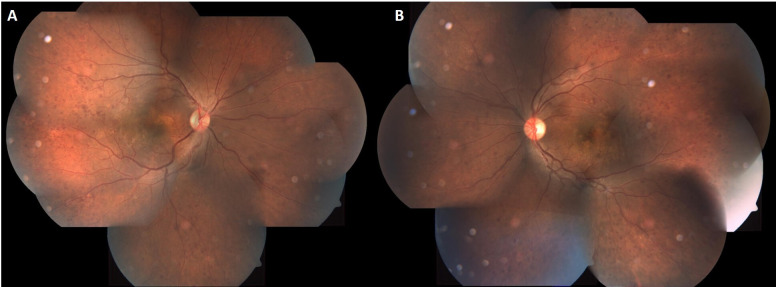

A 38-year-old man presented with blurring of vision in both eyes for the past 1 week for both distance and near. There was no history of trauma, diabetes mellitus or hypertension. His unaided vision was 20/20, N36 in the right and 20/20, N6, in the left eye not improving further. On ophthalmic examination, his anterior segment was unremarkable with a normal pupillary reaction. Vitreous was clear in both eyes. Fundus showed multiple dot and blot haemorrhages, dilated and tortuous vessels with salmon pink discolouration, white coloured retinal infiltrates and subretinal yellow white deposits at the macula in both eyes (figure 1). Multimodal imaging was ordered to decipher the nature of the lesions. A salmon pink discolouration of the blood within the retinal vessels led us to investigate him further to rule out a blood dyscrasia in addition to vasculitis workup.

Figure 1.

Coloured fundus images of the right (A) and left (B) eyes showing dilated and tortuous vessels with a salmon pink hue (black arrow), multiple superficial retinal haemorrhages (white arrow) and white colour retinal infiltrates (blue arrow).

Investigations

Fundus fluorescein angiography showed blocked fluorescence due to retinal haemorrhages and infiltrates and segmentation of the dye along the venous wall in arteriovenous phase and multiple pinpoint leakages and peripheral capillary non-perfusion areas in late phase in both eyes (figure 2). Optical coherence tomogram with transfoveal line scan showed neurosensory detachment (figure 3) and with line scan through the retinal infiltrates showed an increase in reflectivity of the inner retinal layer with distortion of retinal architecture (figure 4).

Figure 2.

Fundus fluorescein angiogram of both eyes showing blocked fluorescence corresponding with the retinal haemorrhages and infiltrates in the arteriovenous phase (yellow arrows in A and B). There are pin point hyperfluorescence secondary to leak from the infiltrates as well as elsewhere in the late venous phase (red arrows in C and D). There is segmentation of the dye suggestive of stasis of blood flow in either eyes more prominent in the early frames (green arrow in B).

Figure 3.

Optical coherence tomogram with transfoveal line scans in right (A) and left (B) eyes showing neurosensory detachment.

Figure 4.

Optical coherence tomogram with line scan passing across the retinal infiltrate showing an increase in reflectivity of the inner retinal layers and loss of retinal architecture.

The haematology picture showed an abnormally high leucocyte count 370 000/μL of blood (normal range: 4000–11 000/μL of blood), while peripheral smear showed immature granulocytes. The total erythrocyte and platelet counts were 2 010 000/μL of blood (normal range: 4 005 000–5 005 000/μL of blood) and 314 000/μL of blood (normal range: 150 000–450 000/μL of blood), respectively. The differential count showed neutrophils (39%), monocytes (52%), lymphocytes (5%), eosinophils and basophils (2% each). The peripheral smear showed immature granulocytes like myeloblasts (3), promylocytes (5), mylocytes (28) and metamyelocytes (16).

Treatment

Based on the clinical findings and blood investigations, a diagnosis of CML with leukaemic retinopathy was made. The patient was referred to a haemato-oncologist and was treated for CML with imatinib and hydroxyurea.

Outcome and follow-up

A month after treatment for CML, he was symptomatically better with resolution of retinal infiltrates, haemorrhages and return of normal colour of the retinal vessels (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Coloured fundus photo montage of right (A) and left (B) eyes on follow-up showing resolution of retinal infiltrates, haemorrhages and return of normal colour of the retinal vessels.

Discussion

Leukaemia can have varied ocular manifestation, depending on the age, type of leukaemia and staging. Leukaemia-associated ocular manifestations are more commonly seen in acute and myeloid types as compared with chronic and lymphoid types. Acute leukaemia is commonly seen in the younger age group with higher incidence of ocular involvement. Retina has been reported to be the most common ocular tissue affected and could be due to direct leukaemic infiltration or secondary complications like anaemia and thrombocytopenia.2 3 Most of the retinal changes are self-limiting as seen in the present case (resolution of infiltrate and retinal haemorrhages).

Prolonged leucocytosis can lead to an increase in blood viscosity and stagnation of blood flow causing venous dilatation, tortuosity, stasis and capillary dropout. This finally leads to areas of capillary non-perfusion and proliferative retinopathy.4

Superficial and deep retinal haemorrhages in leukaemia can be secondary to anaemia, thrombocytopenia and vascular occlusion. These can occasionally be white centred. The white centre represents cellular debris, capillary emboli or accumulation of leukaemic cells.

The nodular retinal infiltrates as seen in our case are more commonly seen in CML and have been reported to indicate local tissue destruction, necrosis and haemorrhage. They are usually seen in fulminant disease, associated with elevated leucocyte counts with a high proportion of blast cells. Leukaemic retinal infiltration combined with a high leucocyte count is an ominous prognostic sign. Early detection of these retinal changes can help in the timely treatment and normalisation of blood parameters, leading to low mortality and morbidity as in our case.3

Sometimes, leukaemic infiltration in the perivascular area can give an appearance of vascular sheathing.4 This can mislead the examiner to treat the patient as a case of idiopathic retinal vasculitis and, in the absence of a detailed haematological evaluation, the underlying haematological disorder could remain undetected for long.

Learning points.

Salmon pink discolouration of the blood column within retinal vessels, in addition to retinal haemorrhages, should warrant for a detailed haematological workup.

Retinal infiltrates are more common in chronic myeloid leukaemia and should be differentiated from retinitis due to infective aetiologies.

Venous dilatation and tortuosity could be secondary to an obstruction and arteriovenous shunting or due to a sluggish circulation. In the absence of the former two, one should do a detailed haematological evaluation to rule out blood dyscrasia.

Footnotes

Contributors: AK, TA and TRP contributed significantly to the acquisition of data, critical analysis, review and final approval of the current version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Zhou H, Xu R. Leukemia stem cells: the root of chronic myeloid leukemia. Protein Cell 2015;6:403–12. 10.1007/s13238-015-0143-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soman S, Kasturi N, Srinivasan R, et al. Ocular manifestations in leukemias and their correlation with hematologic parameters at a tertiary care setting in South India. Ophthalmol Retina 2018;2:17–23. 10.1016/j.oret.2017.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rane PR, Barot RK, Gohel DJ, et al. Chronic myeloid leukaemia presenting as bilateral retinal haemorrhages with multiple retinal infiltrates. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:ND04–5. 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18215.7822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenthal AR. Ocular manifestations of leukemia. A review. Ophthalmology 1983;90:899–905. 10.1016/S0161-6420(83)80013-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]