Abstract

Paradoxical coronary artery embolism is often an underdiagnosed cause of acute myocardial infarction (MI). It should always be considered in patient with acute MI and a low risk profile for atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. We describe a patient with simultaneous acute saddle pulmonary embolism (PE) and acute ST segment elevation MI due to paradoxical coronary artery embolism. Transoesophageal echocardiography demonstrated a patent foramen ovale with right to left shunt and large saddle PE in the main pulmonary artery and coronary angiography demonstrated acute thrombotic occlusion of the right coronary artery.

Keywords: interventional cardiology, ischaemic heart disease, venous thromboembolism

Background

Paradoxical coronary embolism is rare cause of acute myocardial infarction (MI). Presentation of coronary embolism is difficult to distinguish from atherosclerotic acute coronary syndrome (ACS) before angiography. It is shown that paradoxical coronary embolism accounts for 25% of acute coronary events in patients less than 35 years of age,1 and there are known cases of coronary emboli originating from deep vein thrombosis. Patients with a patent foramen ovale (PFO) and major pulmonary embolism (PE) had more than 10-fold increased mortality compared with those without a PFO, and this was thought to result from paradoxical emboli to either the coronary or, more commonly, the cerebral circulation.2 We present an unusual case of a simultaneous paradoxical coronary embolism causing ST elevation MI and acute PE with resulted in cardiovascular collapse.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old woman with a medical history of osteogenesis imperfecta, quadriparesis secondary to cervical spinal injury was being treated for partial small obstruction and nephrolithiasis in the right kidney. She was status post lithotripsy and stent placement under fluoroscopy guidance and was found to be bradycardic with heart rate of 35 bpm and systolic blood pressure of 72 mm Hg which subsequently improved with oxygen and intravenous fluids. An electrocardiogram (EKG) (figure 1) showed ST segment elevation in inferior (II, III and aVF) leads. Patient subsequently became unresponsive and telemetry showed ventricular tachycardia which then progressed to ventricular fibrillation. Cardiac biomarkers were elevated (troponin-T 16.7 ng/mL (normal <0.01 ng/mL) and creatine kinase myocardial band fraction 52 ng/mL (normal <6.7 ng/mL)).

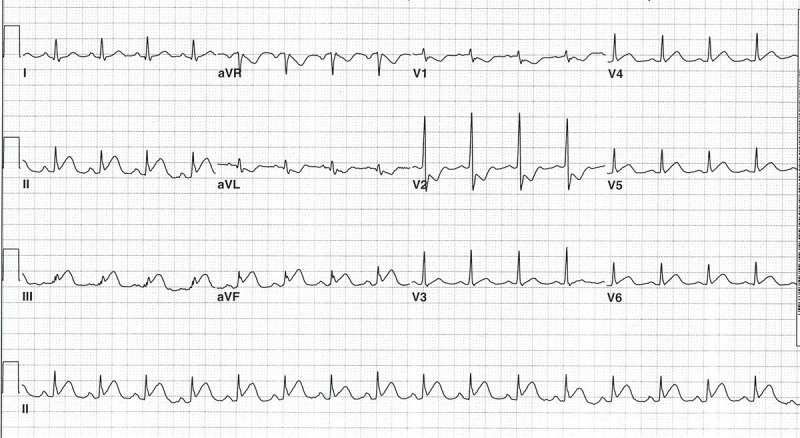

Figure 1.

ECG showing ST segment elevation in lead II, III, aVF and ST depression in V1 to V2.

Coronary angiography revealed occlusion of the right coronary artery (RCA) in the distal segment prior to the take-off of the posterior left ventricular (PLV) and posterior descending artery (PDA) (figure 2A). The lesion was traversed using a.014-inch coronary guide wire and flow was immediately established to the distal part of the RCA. There was evidence of a large thrombus burden. An AngioJet catheter was used on the RCA to perform mechanical rheolytic thrombectomy with successful achievement of the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 3 flow (figure 2B). However, the patient continued to be haemodynamically unstable and required placement of an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) for support and temporary right ventricular pacing. Patient required defibrillation during the procedure and was started on amiodarone infusion.

Figure 2.

(A) Coronary angiogram revealing occlusion of the right coronary artery (RCA) in the distal segment prior to the take-off of the posterior left ventricular (PLV) and posterior descending artery (PDA). (B) normal flow in the RCA after mechanical thrombectomy using Angiojet rheolytic thrombectomy.

A repeat angiogram of the RCA revealed no evidence of acute plaque rupture and the patient’s coronary artery was angiographically normal. The operator then attempted to cannulate the pulmonary artery in an attempt to place a Swan-Ganz catheter for further haemodynamic assessment but was unable to do so. At this time due to high suspicion of PE, a transoesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was done. TEE showed a large PFO (figure 3A) with right to left shunt as seen on colour Doppler imaging (figure 3B). In addition, a large saddle thrombus was seen in the main pulmonary artery straddling both left and right branches (figure 3C). Patient continued to be haemodynamically unstable with continuous intravenous vasopressor and IABP support and the decision was made to do thrombolysis of PE. Pulmonary artery was carefully cannulated and AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy was performed starting from the main pulmonary artery initially into the left pulmonary artery and then into the right pulmonary artery. Twenty milligram to tissue plasminogen activator and full dose of heparin over 30 min was given through the PA catheter with adequate haemodynamic results. In addition to long-term treatment with warfarin for PE, percutaneous PFO closure was recommended to prevent recurrent embolism but patient refused and eventually had an inferior vena cava filter placement by vascular surgery. The patient went on to make a full recovery.

Figure 3.

(A) Transoesophageal echocardiography (TTE) showing a large patent foramen ovale (PFO). (B) Colour Doppler imaging across the PFO with evidence of right to left shunt. (C) TTE showing large thrombus in the main pulmonary artery and right pulmonary artery.

Outcome and follow-up

Patient has been following up in the cardiology clinic regularly since her procedure. Her last visit was 1 year ago and she has been asymptomatic.

Discussion

Paradoxical coronary embolism is rare cause of acute MI. Presentation of coronary embolism is difficult to distinguish from atherosclerotic ACS before angiography. Prizel et al3 showed in a cohort that 13% of the acute MI with coronary arteries thrombosis had no demonstrable acute plaque rupture, suggesting an embolic source. Most had underlying valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy or atrial fibrillation.

It is shown that paradoxical coronary embolism accounts for 25% of acute coronary events in patients less than 35 years of age.1 There are case reports of coronary emboli originating from deep vein thrombosis. Emboli pass through an interatrial communication, and then into the coronary arteries. Patients with a PFO and major PE had more than 10-fold increased mortality compared with those without a PFO, and this was thought to result from paradoxical emboli to either the coronary or, more commonly, the cerebral circulation.2 Our patient was at high risk of developing venous thromboembolism because of decreased physical activity.

Our patient suddenly became bradycardic with hypotension. A large saddle PE was in the differential for her sudden haemodynamic instability. But the EKG was suggestive of acute inferior and possibly posterior MI which was the likely cause of her sudden haemodynamic instability. The management of ACS caused by paradoxical coronary artery embolism is similar to atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Angiographically, coronary embolism may present with a large thrombus burden and smaller emboli may be present more distally. It has been suggested that aspiration allows better assessment of the underlying coronary artery and aspiration thrombectomy may be considered in the presence of high thrombus burden.4

Our patient had successful mechanical thrombectomy with Angiojet with excellent outcome. Her coronary arteries were angiographically normal and no further intervention was required. If there’s high suspicion of paradoxical embolism, both TEE and transthoracic echocardiography can be used to identify communication across the atrial septum and bubble studies may be used to confirm the presence of a PFO. In the presence of a PFO, screening for deep vein thrombosis or PE should also be considered. Given the high suspicion of PE in our patient, a TEE was done which confirmed massive saddle PE in the main pulmonary artery.

Learning points.

We believe our case demonstrates three important clinical points that cardiologists need to be aware:

There should be a high suspicion of paradoxical coronary embolism particularly in patients who presents with a myocardial infarction (MI) with high thrombus burden and no evidence of coronary artery disease.

Any patients who continue to remain unstable following an MI due to suspected coronary artery paradoxical embolism following the re-establishment of blood flow, other sequelae of peripheral embolism should be considered such as pulmonary embolism.

Rheolytic thrombectomy can be successfully performed in both the coronary and pulmonary vascular beds in the same sitting.

Footnotes

Contributors: HG, NKS, ZH and ER were involved in the case and contributed equally in writing the case report. HG and ER performed major revisions and approved the final version of the case report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Velebit V, al-Tawil D. [Myocardial infarct in a young man with angiographically normal coronary arteries and atrial septal defect]. Med Arh 1999;53:33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Kasper W, et al. Patent foramen ovale is an important predictor of adverse outcome in patients with major pulmonary embolism. Circulation 1998;97:1946–51. 10.1161/01.CIR.97.19.1946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prizel KR, Hutchins GM, Bulkley BH. Coronary artery embolism and myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 1978;88:155–61. 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raphael CE, Heit JA, Reeder GS, et al. Coronary embolus: an underappreciated cause of acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018;11:172–80. 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.08.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]