Abstract

Dynamic RNA-protein interactions underpin numerous molecular control mechanisms in biology. However, relatively little is known about the kinetic landscape of protein interactions with full-length RNAs. The extent to which interaction kinetics vary for the same RNA element across the transcriptome, and the molecular determinants of variability, therefore remain poorly defined. Moreover, how one protein-RNA interaction might be transduced by RNA to kinetically impact a second is unclear. We report a parallelized, real-time single-molecule fluorescence assay for protein interaction kinetics on eukaryotic messenger RNA populations obtained from cells. We observed ~100-fold heterogeneity for interactions of the translation factor eIF4E with the universal mRNA 5ʹ cap structure, dominated by steric effects on barrier-height variability for association. We also found that an RNA helicase, eIF4A, independently accelerated eIF4E-cap association. These data support a kinetic mechanism for how mRNA can determine the sensitivity of its translation to reduction in cellular eIF4E concentrations. They also support the view that global RNA structure significantly modulates protein-RNA interaction dynamics, and can facilitate real-time communication between protein interactions at distinct sites.

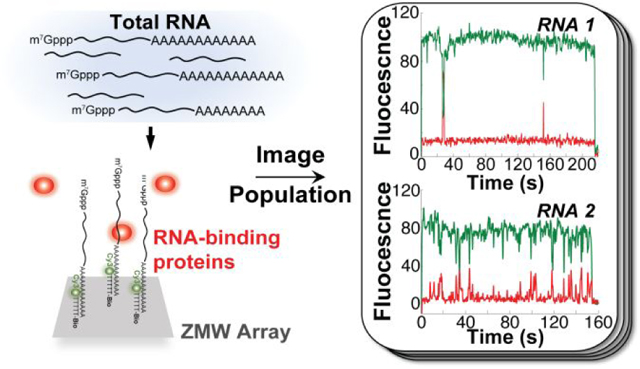

Graphical Abstract

RNA-protein interactions are fundamentally important at all stages of regulated gene expression. They are highly dynamic, and separate interactions frequently coordinate on a single RNA molecule to transduce a biological response.1 One example is the interplay between mRNA 5ʹ-cap structure recognition and mRNA helicase activity, which differentiates the efficiency of protein synthesis between mRNAs.2

Understanding the chemical-kinetic principles of RNA-protein interaction is therefore important in defining molecular mechanisms of the corresponding biological processes. It is critical when interactions occur in a non-equilibrium regime, where binding reactions or their biological consequences are kinetically controlled.3 However, kinetic information on protein interactions with full-length native RNAs is scarce. Moreover, relatively little is known about how protein-binding kinetics for an individual RNA element might differ between RNAs transcriptome-wide.

Cutting-edge technologies have probed RNA-protein interactions at transcriptome scale, with in vivo crosslinking-based snapshots, or through directly imaging protein interactions in vitro on libraries of ~107 RNA sequences up to ~300 nucleotides long.4–7 These approaches observed equilibrium binding and protein dissociation, revealing substantial diversity across local RNA sequences and secondary structures.4,5 However, transcriptome-wide data on both association and dissociation kinetics for full-length transcripts obtained from cells are not yet available. Thus, the contributions of global RNA structure and sequence landscapes to RNA-protein dynamics remain unclear. Additionally, existing studies have not yet fully addressed how formation of one RNA-protein interaction impacts the dynamics of contemporaneous interactions on the same RNA.

We developed a single-molecule fluorescence approach to observe real-time protein association and dissociation across an mRNA population obtained from eukaryotic cells (Figure 1a–c). We employed a customized Pacific Biosciences RS II DNA sequencer,8 which utilizes zero-mode waveguide (ZMW) technology to observe up to 150,000 single-molecule reactions simultaneously. Applied previously to define single-molecule dynamics on many copies of the same transcript,9,10 here we observed dynamics on mRNA populations from Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

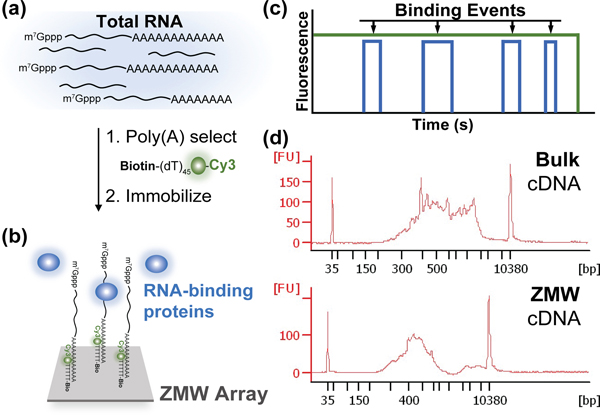

Figure 1.

Experimental approach to analyze single-molecule protein-RNA interaction dynamics on transcriptome-derived mRNA populations. (a) mRNA is selected from total RNA by hybridization of a biotinylated, fluorescent oligonucleotide, biotin-5ʹ-(dT)45-3ʹ-Cy3, to the poly(A) tail. (b) Single mRNA molecules are specifically immobilized across an array of zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs), to image binding of fluorescently-labeled proteins. (c) Idealized single-molecule fluorescence trajectory for cycles of RNA-protein binding and release. (d) Comparison of mRNA size distributions in the bulk input (top) and surface-immobilized (bottom) mRNA populations, assessed by reverse transcription followed by PCR analysis.

We surface-immobilized S. cerevisiae mRNAs by subjecting a total RNA preparation (Supplementary Figure 1a) to an annealing reaction with a fluorescent oligonucleotide, biotin-5ʹ-(dT)45-3ʹ-Cy3 (Figure 1a). This oligonucleotide hybridizes to mRNA 3ʹ-poly(A) tails, allowing specific mRNA fluorescent labeling and biotinylation in the presence of excess ribosomal RNA and tRNA (Figure 1a; Supplementary Figure 1b). We optimized conditions to immobilize a ~104-mRNA population across the ZMW array via biotin-avidin interactions (Figure 1b).

Yeast mRNA transcript abundance varies orders of magnitude across different genes.11,12 To determine the extent to which our ZMW-immobilized population represented the yeast transcriptome, we compared the length distributions of the bulk input and immobilized mRNAs, by a RT-PCR analysis developed for single-cell RNA-seq.13 The cDNA length distributions spanned a similar range, with enrichment in shorter mRNAs in ZMWs (Figure 1d). Single-gene PCR analyses of the ZMW-derived cDNA library confirmed the presence of transcripts with ~8-fold copy-number variation in vivo (Supplementary Figure 1c).11 Our immobilized population thus captures a significant subset of the transcriptome.

To observe mRNA-interaction dynamics of a protein with a common binding mode across all mRNAs, we chose eIF4E, which specifically binds the mRNA 5ʹ m7G(5ʹ)ppp(5ʹ)N cap structure (N is the +1 nucleotide) (Supplementary Figure 2a). We derivatized14 S. cerevisiae eIF4E with a fluorophore, Cy5, allowing observation of single-molecule mRNA cap-binding events. This signal requires both the mRNA cap and poly(A) tail, ensuring it reports on protein interactions with intact mRNAs (Figure 2a).

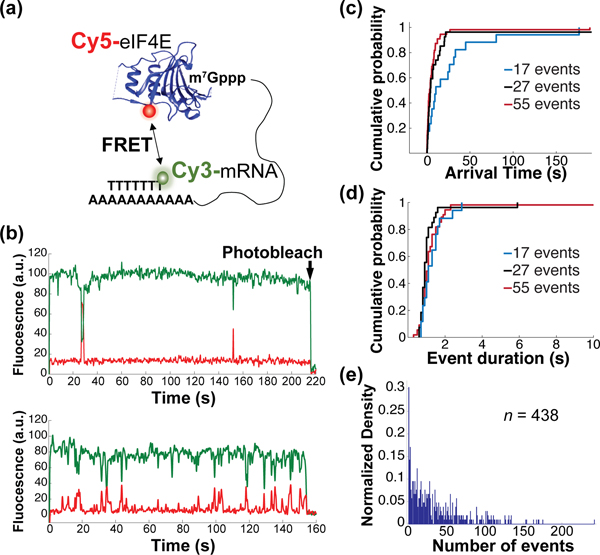

Figure 2.

Heterogeneity of RNA-protein binding dynamics on a transcriptome-derived mRNA population. (a) Schematic of experimental approach showing smFRET signal between immobilized, Cy3-labeled mRNA and Cy5-labeled eIF4E cap-binding protein. (b) Representative single-molecule fluorescence trajectories for eIF4E-mRNA binding, contrasting mRNAs with few (top) and many (bottom) eIF4E-binding events. (c) Empirical cumulative probability distribution of eIF4E-mRNA arrival times from molecules showing 17, 27, and 55 events. (d) Empirical cumulative probability distribution of eIF4E-mRNA event durations on the same mRNAs as in panel (d). (e) Distribution of numbers of eIF4E–mRNA binding events observed across 438 mRNA molecules over a 10-minute observation.

We delivered Cy5-eIF4E to the immobilized mRNA population. As observed for short, capped RNA oligonucleotides14, for thousands of mRNAs we observed single-molecule Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET) between 5ʹ cap-bound Cy5-eIF4E, and Cy3-(dT)45 hybridized to the 3ʹ poly(A) tail (Figure 2b). Experiments where the Cy5 fluorophore attached to eIF4E was directly excited confirmed that this FRET signal reports on the true association and dissociation rates for the eIF4E•mRNA complex (Supplementary Figure 3a–c; Supplementary Discussion D1). That we observed efficient FRET indicates 5ʹ and 3ʹ ends are within ~5 nm for many mRNAs, even in the absence of proteins paradigmatically thought to drive mRNA end-to-end proximity, i.e. eIF4G, a subunit of the cap-binding complex, and poly(A)-binding protein.15 This is consistent with results indicating the ends of mRNA-sized RNAs are intrinsically close in space.16–19

eIF4E-mRNA interaction was characterized by rapidly reversible binding and dissociation (Figure 2b–d). Single-molecule fluorescence trajectories for each mRNA are therefore characterized by the arrival times between FRET events, and their durations. Arrival times typically showed a double-exponential distribution, with a fast arrival rate contributing >80% of the total amplitude in the cumulative distribution function (Figure 2c, Supplementary Figure 3d). This is consistent with a stochastic, Poisson-type sampling process for eIF4E–mRNA binding. The double-exponential nature of the distribution appears to be predominantly a consequence of measuring protein-RNA association kinetics in ZMWs, rather than of differential binding to slowly-interconverting mRNA conformations (Supplementary Figure 3d,e; Supplementary Discussion D2). Event-duration distributions were more complex but were typically dominated by an exponential distribution (Figure 2d). These results support a two-state equilibrium-binding model for yeast and human eIF4E.14,20

We analyzed eIF4E interaction with 438 mRNAs chosen arbitrarily from the population. We constructed a distribution of the number of times each mRNA bound eIF4E during a 10-minute observation (Figure 2e), as censored by FRET-donor photobleaching. The 5th and 95th percentiles of this distribution lay at 1 and 104 events, respectively, representing a ~100-fold variability in eIF4E binding. The median mRNA bound eIF4E 23 times, which scaled with eIF4E concentration (Supplementary Figure 4a). In contrast, distributions generated for similar populations of the JJJ1 and NCE102 transcripts showed variabilities of only ~26- and ~18-fold (Supplementary Figure 4b). Thus, we propose that the ~100-fold variability reflects authentic kinetic diversity driven by mRNA identity.

We extracted mean eIF4E-mRNA binding rates for each mRNA in the population, by fitting the arrival-time distributions for each mRNA to an exponential model (Supplementary Figure 5a). We excluded molecules with fewer than 10 observed binding events to ensure robust fitting.

eIF4E-mRNA association rate constants were distributed between 0.32 μM−1 s−1 and 119 μM−1 s−1, with a median of 5.0 μM−1 s−1. The 5th and 95th percentiles of the distribution lay at 1.04 μM−1 s−1 and 20.8 μM−1 s−1, a ~20-fold variability (Figure 3a). The fastest rate constants approached those for eIF4E binding to an unstructured, capped RNA oligonucleotide.14 Similar values were obtained in analyses that excluded trajectories with increasing goodness-of-fit stringency (Supplementary Figure 5b). The 20-fold association-rate range thus likely sets a lower limit on the true diversity transcriptome-wide.

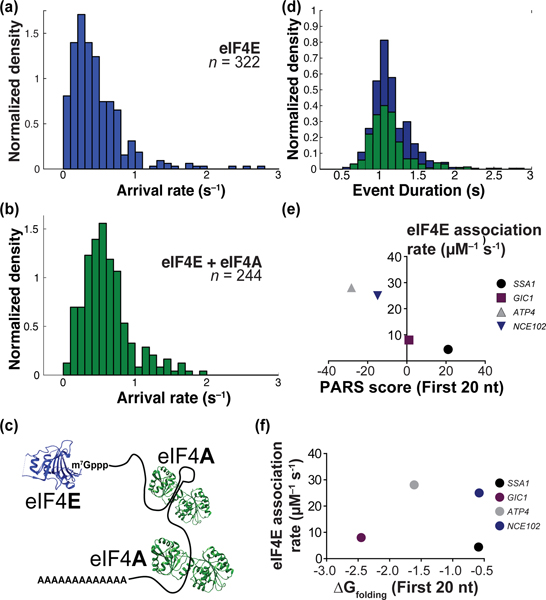

Figure 3.

Distributions of protein-RNA binding kinetics. (a) On-rate distribution for eIF4E binding to 322 arbitrarily-chosen mRNAs from the surface-immobilized population. (b) eIF4E-mRNA on-rate distribution in the presence of eIF4A. (c) Schematic with relative mRNA-binding sites of eIF4E and eIF4A. (d) Distribution of eIF4E-mRNA event durations in the absence (blue) and presence (green) of eIF4A. (e) Correlation of eIF4E-mRNA association rate with the extent of cap-proximal 20 nucleotides, as measured by PARS score. (f) Correlation of eIF4E-mRNA association rate with computed folding free energy change at 30˚C for the cap-proximal 20 nucleotides.

We also examined the distribution of binding-event durations for each mRNA in the population. To avoid overfitting we chose the arithmetic mean as the metric for eIF4E-mRNA binding duration. The event-duration distribution was almost an order of magnitude narrower than for arrival rates (5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles at 0.75 s, 1.1 s, and 1.8 s, respectively – a 2.4-fold variation (Figure 3d)). This echoes measurements of protein dissociation from ~107 different short RNA sequences, where the same confidence intervals ranged over 12.2-fold across a large sequence space.4,5

Previous results for structured oligoribonucleotides revealed a complex relationship between cap-proximal RNA structure and eIF4E equilibrium affinity.21 We asked whether a similarly complex relationship exists for eIF4E association rates on full-length yeast mRNAs. We correlated eIF4E association rates with mRNA PARS scores22, an experimental measure of secondary structural propensity. For four transcripts (ATP4, GIC1, SSA1, and NCE102) chosen to span the range of “structuredness” in their cap-proximal nucleotides, we found eIF4E-mRNA association rates (Supplementary Figure 6) showed an unambiguous anticorrelation with structural propensity (Figure 3e; Supplementary Figure 7a). This correlation persisted for at least the first 40 nucleotides, but not for the entire transcript (Supplementary Discussion D3). In contrast, computationally-predicted23 folding free energy changes for isolated cap-proximal RNA sequences were not strongly correlated with eIF4E-mRNA association rates (Figure 3f, Supplementary Figure 7b). eIF4E dissociation rates were again narrowly distributed (~0.5 – 0.8 s−1; Supplementary Figure 6c).

These results support a model where extent of mRNA structure kinetically controls eIF4E association rate. Steric block of the eIF4E-cap interaction by the mRNA body is expected to vary between mRNAs. Barriers to dissociation are expected to be less variable, reflecting similar structural environments for mRNA 5ʹ ends in the eIF4E•mRNA complex. Since the free energy change for eIF4E binding to cap structure analogs lacking an RNA body is dominated by interactions with the methylated guanine base and the triphosphate bridge24, differences in affinity imply barrier-height variation between distinct mRNA-protein encounters marked by early transition states.

mRNAs with evidently low secondary structure may still form compacted arrangements of the RNA chain.25 We therefore asked whether these higher-order structures could modulate eIF4E-cap association, by determining the response of eIF4E–mRNA dynamics to inclusion of the helicase eIF4A. In the presence of ATP, S. cerevisiae eIF4A binds double-stranded and single-stranded RNA with equilibrium dissociation constants of ~20 nM and ~1.5 μM, respectively, but does not appreciably unwind duplexes in the absence of protein cofactors.26 In our experiments, eIF4A thus simply acts as a dual double-stranded and single-stranded RNA binding protein (Figure 3c).

Addition of 2 μM eIF4A with 2.5 mM ATP significantly altered the association-rate distribution for the mRNA population (p = 7.6 × 10−10, Wilcoxon’s test) (Figure 3b). The peak in the arrival-rate distribution shifted to ~8 μM−1 s−1, from ~5 μM−1 s−1 without eIF4A. Meanwhile, the event-duration distribution remained unchanged (Figure 3d). Because cap-proximal eIF4A binding might reasonably impact eIF4E dissociation, these results are consistent with eIF4A–mRNA binding remote from the eIF4E binding site perturbing mRNA global structure, and in turn altering the barrier to eIF4E-mRNA association.

In summary, these data reveal order-of-magnitude heterogeneity for the kinetics of protein interaction with the same RNA element across the transcriptome, defined largely by variable association rates, at least for the eIF4E-cap interaction.

Modulation of cellular active eIF4E concentration is a major control mechanism for protein synthesis.27 However, not all mRNAs are equally sensitive to changing eIF4E levels; mRNAs with structured 5ʹ ends are particularly sensitive. Order-of-magnitude heterogeneity in eIF4E-cap association rates suggests a kinetic mechanism for this differential sensitivity: mRNAs with intrinsically fast association are likely to sustain eIF4E-cap binding sufficient to allow continued translation initiation even at low eIF4E availability. Furthermore, recent work has implicated free eIF4A activity throughout the length of the mRNA as accelerating ribosome-mRNA recruitment.28 Our results suggest that this effect may be exerted even at the very initial steps of mRNA selection for translation. Overall, our results highlight how kinetic heterogeneity, determined by the sequence and structural information encoded throughout RNA transcripts, may contribute significantly to dynamic control of gene expression.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants GM111858 and GM139056 to SO’L), by a University of California Riverside Regents’ Faculty Fellowship, and by institutional funds from UC Riverside. We thank Reuben Franklin (UC Riverside) for assistance with RT-PCR. We thank Jin Chen (UT Southwestern Medical Center) and Jikui Song (UC Riverside) for insightful discussions and comments on the manuscript. We thank Adler Dillman (UC Riverside) for providing the template switching oligonucleotide, and Justin Chartron (UC Riverside) for providing the yeast W303 strain.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Methods and Supplementary Figures for RNA and protein purification, RNA immobilization and imaging of protein binding, data analysis and validation. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website. The PDF document contains experimental procedures, purification data, and validation results for the data analysis.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Müller-McNicoll M; Neugebauer KM How cells get the message: dynamic assembly and function of mRNA-protein complexes. Nat. Rev. Genet 2013, 14 (4), 275–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Feoktistova K; Tuvshintogs E; Do A; Fraser CS Human eIF4E promotes mRNA restructuring by stimulating eIF4A helicase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110 (33), 13339–13344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).McCarthy JEG Posttranscriptional control of gene expression in yeast. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 1998, 62(4), 1492–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Buenrostro JD; Araya CL; Chircus LM; Layton CJ; Chang HY; Snyder MP; Greenleaf WJ Quantitative analysis of RNA-protein interactions on a massively parallel array reveals biophysical and evolutionary landscapes. Nat. Biotechnol 2014, 32 (6), 562–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).She R; Chakravarty AK; Layton CJ; Chircus LM; Andreasson JOL; Damaraju N; McMahon PL; Buenrostro JD; Jarosz DF; Greenleaf WJ Comprehensive and quantitative mapping of RNA–protein interactions across a transcribed eukaryotic genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U S A, 2017, 114(14), 3619–3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Guenther U-P; Yandek LE; Niland CN; Campbell FE; Anderson D; Anderson VE; Harris ME; Jankowsky E. Hidden specificity in an apparently nonspecific RNA-binding protein. Nature. 2013, 502(7471), 385–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ozer A; Tome JM; Friedman RC; Gheba D; Schroth GP; Lis JT Quantitative assessment of RNA-protein interactions with high-throughput sequencing–RNA affinity profiling Nat Protoc. 2015;10(8):1212–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Chen J; Dalal RV; Petrov AN; Tsai A; O’Leary SE; Chapin K; Cheng J; Ewan M; Hsiung P-L; Lundquist P; Turner SW; Hsu DR; Puglisi JD High-throughput platform for real-time monitoring of biological processes by multicolor single-molecule fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2014, 111 (2), 664–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Choi J; Puglisi JD Three tRNAs on the ribosome slow translation elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114 (52), 13691–13696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Duss O; Stepanyuk GA; Grot A; O’Leary SE; Puglisi JD; Williamson JR Real-time assembly of ribonucleoprotein complexes on nascent RNA transcripts. Nat. Commun 2018, 9 (1), 5087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lahtvee P-J; Sánchez BJ; Smialowska A; Kasvandik S; Elsemman IE; Gatto F; Nielsen J. Absolute quantification of protein and mRNA abundances demonstrate variability in gene-specific translation efficiency in yeast. Cell Syst. 2017, 4 (5), 495–504.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Miura F; Kawaguchi N; Yoshida M; Uematsu C; Kito K; Sakaki Y; Ito T. Absolute quantification of the budding yeast transcriptome by means of competitive PCR between genomic and complementary DNAs. BMC Genomics 2008, 9, 574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Picelli S; Faridani OR; Björklund AK; Winberg G; Sagasser S; Sandberg R. Full-length RNA-Seq from single cells using Smart-seq2. Nat. Protoc 2014, 9 (1), 171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).O’Leary SE; Petrov A; Chen J; Puglisi JD Dynamic recognition of the mRNA cap by Saccharomyces cerevisiae eIF4E. Structure 2013, 21 (12), 2197–2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wells SE; Hillner PE; Vale RD; Sachs AB Cirularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol. Cell 1998, 2(1), 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Vicens Q; Kieft JS; Rissland OS Revisiting the closed-loop model and the nature of mRNA 5′–3′ communication. Mol. Cell 2018, 72(5), 805–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Yoffe AM; Prinsen P; Gelbart WM; Ben-Shaul A. The ends of a large RNA molecule are necessarily close. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39 (1), 292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lai W-JC; Kayedkhordeh M; Cornell EV; Farah E; Bellaousov S; Rietmeijer R; Salsi E; Mathews DH; Ermolenko DN mRNAs and lncRNAs intrinsically form secondary structures with short end-to-end distances. Nat. Commun 2018, 9 (1), 4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Leija-Martínez N; Casas-Flores S; Cadena-Nava RD; Roca JA; Mendez-Cabañas JA; Gomez E; Ruiz-Garcia J. The separation between the 5′−3′ ends in long RNA molecules is short and nearly constant. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42(22), 13963–13968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Slepenkov SV; Korneeva NL; Rhoads RE Kinetic mechanism for assembly of the m7GpppG·eIF4E·eIF4G Complex. J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283(37), 25227–25237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Carberry SE, Friedland DE, Rhoads RE, Goss DJ Binding of protein synthesis initiation factor 4E to oligoribonucleotides: effects of cap accessibility and secondary structure. Biochemistry 1992, 31(5), 1427–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Kertesz M; Wan Y; Mazor E; Rinn JL; Nutter RC; Chang HY; Segal E. Genome-wide measurement of RNA secondary structure in yeast. Nature 2010, 467 (7311), 103–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31(13), 3406–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Niedzwiecka A; Marcotrigiano J; Stepinski J; Jankowska-Anyszka M; Wyslouch-Cieszynska A; Dadlez M; Gingras A-C; Mak P; Darzynkiewicz E; Sonenberg N; Burley SK; Stolarski R. Biophysical studies of eIF4E cap-binding protein: recognition of mRNA 5′ cap structure and synthetic fragments of eIF4G and 4E-BP1 proteins. J. Mol. Biol 2002, 319(3), 615–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kovtun AA, Shirokikh NE, Gudkov AT, Spirin AS. The leader sequence of tobacco mosaic virus RNA devoid of Watson-Crick secondary structure possesses a cooperatively melted, compact conformation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2007, 358(1):368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Rajagopal V; Park E-H; Hinnebusch AG; Lorsch JR Specific domains in yeast translation initiation factor eIF4G strongly bias RNA unwinding activity of the eIF4F complex toward duplexes with 5ʹ-overhangs. J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287(24), 20301–20312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Hershey JWB, Sonenberg N, Matthews MB Principles of translational control. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 2019, 11(9), a032607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Yourik P; Aitken CE; Zhou F; Gupta N; Hinnebusch AG; Lorsch JR Yeast eIF4A enhances recruitment of mRNAs regardless of their structural complexity Elife. 2017, 6:e31476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.