Abstract

The use of immune reconstitution therapies (IRT) in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) is associated with a prolonged period of freedom from relapses in the absence of continuously applied therapy. Cladribine tablets is a disease-modifying treatment (DMT) indicated for highly active relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS) as defined by clinical or imaging features. Treatment with cladribine tablets is effective and well tolerated in patients with active MS disease and have a low burden of monitoring during and following treatment. In this article, an expert group of specialist neurologists involved in the care of patients with MS in the United Arab Emirates provides their consensus recommendations for the practical use of cladribine tablets according to the presenting phenotype of patients with RRMS. The IRT approach may be especially useful for patients with highly active MS insufficiently responsive to treatment with a first-line DMT, those who are likely to adhere poorly to a continuous therapeutic regimen, treatment-naïve patients with high disease activity at first presentation, or patients planning a family who are prepared to wait until at least 6 months after the end of treatment. Information available to date does not suggest an adverse interaction between cladribine tablets and COVID-19 infection. Data are unavailable at this time regarding the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination in patients treated with cladribine tablets. Robust immunological responses to COVID-19 infection or to other vaccines have been observed in patients receiving this treatment, and treatment with cladribine tablets per se should not represent a barrier to this vaccination.

Keywords: Cladribine tablets, Disease-modifying therapy, Multiple sclerosis, United Arab Emirates

Key Summary Points

| Cladribine tablets is a disease-modifying treatment (DMT) for highly active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) that acts in a manner consistent with being an immune reconstitution therapy (IRT). |

| This treatment is effective and well tolerated in patients with active relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS), with a low burden of monitoring during and following treatment. |

| We, an expert group of specialist neurologists involved in the care of patients with MS in the United Arab Emirates, provide our consensus recommendations for the practical use of cladribine tablets according to the presenting phenotype of patients with RRMS. |

| The IRT approach may be especially useful for patients with highly active MS uncontrolled by a first-line DMT, where the likelihood of adherence to continuous treatment is uncertain, for naïve high disease active patients at first presentation or for patients planning a family who are prepared to wait until at least 6 months after the end of treatment. |

| Current data support the safety of cladribine tablets in patients who contract COVID-19, and receipt of this treatment per se should not represent a barrier to vaccination against COVID-19. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14217224.

Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis in the United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is currently home to about 9.9 million people, a figure expected to increase by about 800,000 by 2033 [1]. Most of the population is concentrated in the three northeastern Emirates of Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Sharjah. Almost nine in ten people in the UAE are expatriate workers from other countries, which complicates calculation of the incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis (see below). Also, this causes a marked gender bias towards males (72% of all current UAE residents are male) [1].

Similarly to other Middle Eastern countries, the UAE has a relatively young population by global standards, with a median age of 33 years [1]. This is similar to the average age of first diagnosis of multiple sclerosis (MS) worldwide of 30 years [2], and higher than some estimates of the average age of onset of MS in the UAE from retrospective or registry studies, for example, 26 years for Emirati patients [3] and 27 years for all patients managed in a major tertiary centre in Dubai. The average age of onset for non-Emirati MS patients in that centre was higher, at 30 years [4]. In Abu Dhabi, the average age of MS onset was 27 years for Emiratis (again, average at onset for non-Emiratis was 30 years) [5]. The preponderance of younger people in the UAE likely contributes to the reported medium-to-high prevalence of MS in Emiratis in the UAE of 55–57/100,000 population [4–6]. One of these studies (from Abu Dhabi) found a crude prevalence of MS in the UAE of 57/100,000, which increased to 64/100,000 when age-standardised [5]. Interestingly, MS was found to be considerably more common in native Emirati people (crude prevalence 55/100,000) than in a mixed population of Emiratis and expatriates (crude prevalence 19/100,000). About three-quarters (77–78%) of Emiratis have the relapsing-remitting form of MS (RRMS) [4–6].

MS is more common in females in the UAE, as in other countries, with a female-to-male ratio among Emirati nationals of 2.85 in Dubai [4] and 1.9 in Abu Dhabi [5]. These findings, together with the relatively young age at which MS manifests in the UAE (see above), indicate a high burden of MS among women of childbearing age. MS is therefore particularly challenging to manage among this population [7].

The application of disease-modifying therapy (DMT) is central to the management of RRMS [8]. It is essential that healthcare professionals caring for people with MS understand the properties of different DMTs and which patients should—or should not—receive them. Cladribine tablets is a relatively new DMT, which was approved for use in people with RRMS the UAE in April 2018. This article provides practical consensus recommendations for the therapeutic use of cladribine tablets within the management of RRMS from an expert group of physicians in the UAE.

About This Review

This narrative review arose from discussions at a closed meeting of experts in the management of MS from the UAE. Experts discussed the current management of RRMS and the potential benefits and limitations of the use of cladribine tablets in their patients. Experts suggested evidence for inclusion, supplemented by PubMed searchers in individual areas of interest, with preference given to authorititative reviews (systematic or otherwise) and randomised trials where possible. This culminated in the use of a consensus procedure (described below) to identify the patient subgroups for whom the experts considered the therapeutic use of cladribine tablets to be most appropriate.

This narrative review article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Overview of Current Pharmacological Management of Multiple Sclerosis

A Note on Prescribing in the Arabian Gulf

It should be noted that prescribing practices in the Arabian Gulf differ somewhat from practices in other regions. International guidelines and labelling from major regulators, such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Medicines Agency (EMA), are influential, but not restrictive on prescribing. The availability of a specific treatment is more likely to be influenced by the formulary in use at a given centre or the availability of funding for that treatment. Regarding cladribine tablets in particular, local labelling in the UAE indicates their use for patients with high disease activity, defined by clinical presentation and MRI findings.

Classifications of DMTs for Use in RRMS

Space permits only a brief account of the properties of each agent to be given here, focussing on principal safety issues and other factors relevant to their long-term use. Comprehensive information can be found in regional [8] and international [9–11] guidelines for MS care and from reviews by experts in the field [12, 13].

DMTs for RRMS can be classified broadly by their efficacy in preventing MS relapses and/or disease progression, with fingolimod, siponimod, natalizumab, ocrelizumab, cladribine tablets, and alemtuzumab categorised as “high efficacy” DMTs, usually reserved for use in patients with higher levels of disease activity that are not well controlled by the “first-line” or “platform” agents (interferons, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, and dimethyl fumarate) [12]. These DMTs can also be classified broadly according to their pharmacological mechanisms of action. For example, dimethyl fumarate, teriflunomide, fingolimod, natalizumab, and the anti-CD20 agents ocrelizumab and ofatumumab [14] (the latter is newly approved for the management of RRMS in the USA) are continuously administered immunosuppressants. Interferons and glatiramer acetate are administered continuously and act via complex mechanisms that do not require a generalised suppression of the immune system [15–17]. Finally, cladribine tablets and alemtuzumab are hypothesised to act as immune reconstitution therapies (IRT) [18].

IRTs differ from other DMTs used in MS in that they are not given continuously. Rather, cladribine tablets and alemtuzumab are given in two short courses 1 year apart (the administration of cladribine tablets is described in more detail below). The administration of a pharmacological IRT causes a marked reduction in the number of circulating immune cells that recovers slowly over time. Specifically, there is a profound and rapid reduction in B (CD19+) cells following treatment with cladribine tablets, which occurs over several weeks and recovers over a period of about 1 year, with a slower and smaller reduction in T cells, which recovers over about 18 months [19, 20]. Treatment with cladribine tablets appears to exert little effect on components of the innate immune system (e.g. monocytes or dendritic cells) [20], while alemtuzumab may exert a larger effect on this component of immunity [21–24].

Two annual short courses of treatment with cladribine tablets in the CLARITY trial and its extension, compared with placebo, provided protection against MS relapses, radiological progression, and progression of disability that clearly outlasted both the persistence of cladribine in the body (days) and the duration of time for which circulating lymphocytes were suppressed (months, see above) [25–29]. Further treatment beyond 2 years was not necessary to maintain protection from recurrence of MS disease activity in about three-quarters of patients. About half (46%) of patients randomised to cladribine tablets maintained no evidence of disease activity (NEDA-3; no relapses; no 6-month EDSS progression; no T1 gadolinium-enhancing/active T2 lesions) during years 3 and 4 [30]. A further post hoc analysis of these data suggested that cladribine tablets was more effective in reducing disability progression in patients with higher vs. lower MS disease activity at baseline [31].

Similar findings have been reported with alemtuzumab, with about 50–60% of patients demonstrating no evident MS disease activity for each of the 3 years following the initial 2-year treatment period [32]. The persistence of efficacy beyond the apparent pharmacological effects of the treatment is the hallmark of an IRT-like mechanism [33].

Clinical evidence on the therapeutic profile of cladribine tablets in patients with less severe presentations of MS is lacking. The randomised ORACLE trial showed that treatment with cladribine tablets significantly reduced the rate of conversion from clinically isolated syndrome to clinically definite MS [34]. A post hoc analysis from this study suggested that cladribine tablets were effective in preventing further demyelinating attacks in patients judged retrospectively to meet the updated McDonald 2010 diagnostic criteria for clinically definite MS [35]. Furthermore, prospective data on the effects of cladribine tablets in patients with early MS would be needed to support a therapeutic indication in this population.

Safety and Tolerability

The risk of infection or malignancy with interferon β or glatiramer acetate is low, although an increased risk of infections or malignancy has been associated with DMTs that cause long-term immunosuppression [36–40]. Treatment with natalizumab for > 2 years, or administration of this agent to patients positive for John Cunningham virus (JCV), is associated with increased risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), although careful selection of patients or this treatment, and careful monitoring during the administration of natalizumab, has minimised the threat of this life-threatening complication of treatment [41]. Other opportunistic infections may arise during treatment with this agent. As of July 2019, seven confirmed cases of PML (plus a further five cases of suspected PML not meeting strict diagnostic criteria for this condition) have been reported in people with MS receiving ocrelizumab [42]. All of these patients had received other DMTs before prescription of ocrelizumab. Rituximab, which shares a similar anti-CD20 mechanism, has also been rarely associated with PML in patients with conditions other than MS [43]. Five cases of PML have been reported in patients with MS receiving dimethyl fumarate (plus another 16 cases associated with this treatment in people with other conditions), and 15 cases of PML have been reported in patients receiving fingolimod [44]. Treatment with fingolimod may also induce bradycardia and impairment of intracardiac conduction, especially early in treatment [45].

The main side effects of cladribine tablets relate to leukopenia/lymphopenia consistent with its therapeutic mechanism of action (see above). There is also potential for activation of latent infections, particularly varicella zoster and tuberculosis (TB), especially in the setting of profound lymphopenia, and patients should be screened and vaccinated against these diseases before treatment [46]. The labelling for this agent cites an increased risk of malignancy, and a recent pooled analysis has identified an interaction with increasing age and increased risk of malignancy for DMTs that deplete immune cells [47]. However, an increased risk of malignancy has not been observed in recent analyses of pooled data from clinical evaluations of cladribine tablets [46], a meta-analysis [48], and a comparison of cancer rates in patients exposed to cladribine tablets vs. the general population in the GLOBOCAN reference database [49]. Alemtuzumab has been associated with severe cardiovascular, autoimmune, and other side effects that now limit its therapeutic use to patients free of “certain heart, circulation or bleeding disorders or in patients who have autoimmune disorders other than multiple sclerosis” where “[MS] is highly active despite treatment with at least one disease-modifying therapy or if the disease is worsening rapidly”, according to the European Medicines Agency [50].

Which Patients with RRMS Should Be Considered for Cladribine Tablets?

Consensus Procedure

The consensus recommendations presented here were based on a series of workshops conducted within a closed meeting of 12 clinical experts in the management of MS based in the UAE (all are co-authors of this article). Experts were presented with a series of scenarios relating to patients with varying MS phenotypes and registered their level of agreement or disagreement regarding the suitability of a prescription of cladribine tablets for each case using a 5-point Likert scale. The clinical situations considered included the management of a newly diagnosed, DMT-naïve patient with RRMS, a patient who has already received one or more alternative DMTs, and a patient who develops new MS disease activity following treatment with cladribine tablets. Practical recommendations regarding investigations required before treatment with cladribine tablets were discussed, along with an overall rating of various aspects of cladribine tablets and other high-efficacy DMTs (ocrelizumab, natalizumab, fingolimod, natalizumab)

Which Patients with RRMS Are Most Suitable for Treatment with Cladribine Tablets?

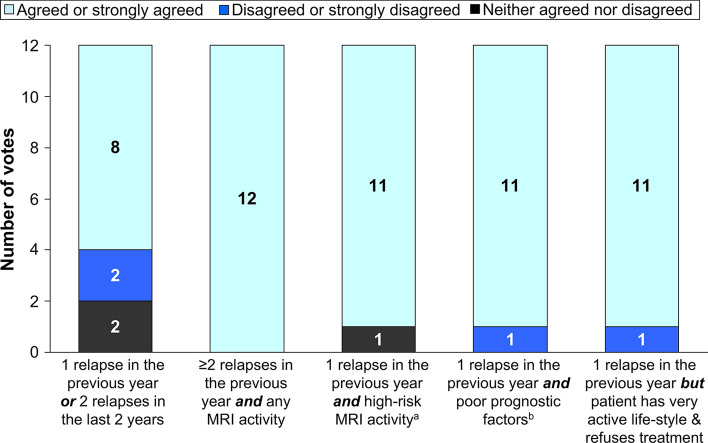

First-Line DMT Therapy for a Patient with RRMS

The first scenario considered patients with newly diagnosed RRMS, with evidence of recent highly active MS, who had not received prior treatment with a DMT (Fig. 1). There was strong support for the use of cladribine tablets in all of the clinical scenarios presented, with greater support for use in patients with high-risk features of MS, such as a higher level of recent MS disease activity, a combination of relapse with radiological activity, MS activity in the brainstem, cerebellum, or spinal cord, or with other adverse prognostic factors (e.g. motor symptoms presentation or MRI findings in high-risk regions) [51].

Fig. 1.

Potential therapeutic use of cladribine tablets for a newly diagnosed patient with RRMS without prior treatment with a disease-modifying therapy

The addition of information on the patient’s lifestyle to the case with the lowest level of MS disease activity influenced the physicians’ likelihood of prescribing cladribine tablets. The proportion of experts who agreed or strongly agreed with the suitability of prescribing cladribine tablets for a patient with one relapse in the previous year or two relapses in the previous 2 years increased from 67 to 100% if the patient had an active lifestyle and a high likelihood of poor adherence to treatment.

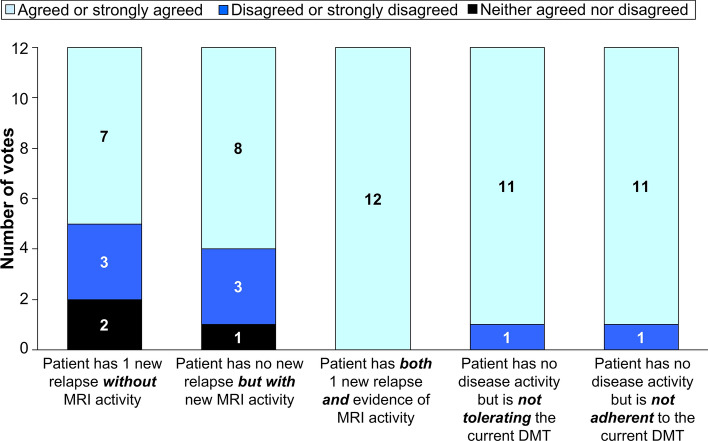

Switching from Another DMT to Cladribine Tablets

There was strong support for the use of cladribine tablets for patients demonstrating either relapses or new MRI activity despite treatment with an alternative DMT (Fig. 2). All experts agreed that switching to cladribine tablets was a rational choice when both relapse and new MS disease activity were present. There was also strong support for using cladribine tablets where the current DMT was not well tolerated or where the patient was not adhering sufficiently well to their current treatment.

Fig. 2.

Potential therapeutic use of cladribine tablets for a patient with RRMS currently receiving a different disease-modifying therapy

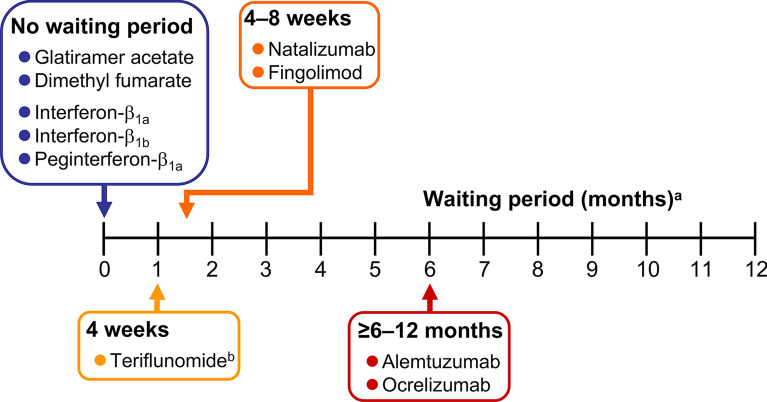

Switching to cladribine tablets must take into account the potential for residual effects on the immune system of the previous treatment, which can be long-lasting for some DMTs. In addition, the potential for rebound disease activation following withdrawal of fingolimod or natalizumab must be considered [52]. Rebound disease activity has been observed in 9–80% of natalizumab-treated patients, with relapses peaking 4–7 months after withdrawal of treatment, especially in patients who were younger, with a higher MS disease burden (more prior relapses and MRI events), and with a shorter duration of treatment with natalizumab [53]. Typical washout periods between withdrawal of the prior DMT and initiation of cladribine tablets are at least 4 weeks for fingolimod or teriflunomide (using the rapid elimination procedure or teriflunomide), about 4–8 weeks for natalizumab, and at least 6–12 months for ocrelizumab or alemtuzumab (Fig. 3). No washout is needed following withdrawal of interferons, dimethyl fumarate, or glatiramer acetate, and cladribine tablets can be initiated immediately, subject to compliance with its labelling requirements (described below, but note that the European and US labelling for cladribine tablets requires that lymphocyte counts must be within normal limits before initiating this treatment).

Fig. 3.

Minimum washout times following discontinuation of a disease-modifying therapy and administration of cladribine tablets. aNote that lymphocytes must be normal before initiating cladribine tablets irrespective of waiting times shown here. bAssumes the rapid elimination procedure for teriflunomide is used

The need to switch to cladribine tablets may occur in response to a perceived lack of efficacy of a previous DMT. Continuing relapses or MRI progression are the usual markers of insufficient disease activity, although there is no agreed set of criteria for identifying a suboptimal response to treatment that requires a change of DMT. In future, composite scores based on disease markers together with NEDA (especially NEDA-4, which includes a measure of cognitive status) will become increasingly important for identifying non-responders to treatment, although this remains in the clinical trial domain for now [54].

Patients with MS Disease Activity after the First Dose of Cladribine Tablets

Treatment with cladribine tablets is given at a total cumulative dose of 3.5 mg/kg over 2 years (Box 1). This involves two periods of 4–5 days (depending on body weight) of oral treatment 1 month apart at the start of treatment, with the same regimen repeated 1 year later. Accordingly, the time between the end of the first session of treatment (start of year 1) and the second period of treatment (start of year 2) represents a period of time where the overall course of treatment with cladribine tablets remains incomplete.

There is no formal clinical evidence base to guide therapy for patients who experience a MS relapse during the first year of treatment with cladribine. The experts agreed unanimously that treatment with cladribine tablets should be continued in this eventuality, rather than switching to an alternative DMT, based on the assumption that the full efficacy of the treatment would not be apparent until the full 2-year course had been given. The relapse would be treated with corticosteroids, in the normal way.

The European labelling for cladribine tablets states that “Following completion of the 2 treatment courses, no further cladribine treatment is required in years 3 and 4”. Thus, there is also no evidence-based guidance for the management of a patient with RRMS who relapses during the second year of treatment, i.e. soon after the full dose of cladribine tablets has been given. In this case, 33% of experts would switch to another high-efficacy DMT, while the remainder would re-treat with cladribine tablets. A higher proportion (58%) would switch (rather than re-treat with cladribine tablets) for a relapse occurring during years 3–4 following the start of treatment with cladribine tablets. Most (92%) would re-treat with cladribine tables for a relapse occurring later than year 4, rather than switch (8%).

Box 1: Posology of cladribine tablets in the management of RRMS.

| 1–2 tablets given for 4–5 consecutive days at these times: | Total cumulative dose | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment year 1 | Beginning of 1st month | |

| Beginning of 2nd month | 1.75 mg/kg | |

| Treatment year 2 | Beginning of 1st month | |

| Beginning of 2nd month | 3.5 mg/kg | |

Cladribine tablets is administered orally as 10 mg tablets over 4–5 days for each of the four treatment periods. The number of tablets per day and the number of days of treatment (4 or 5) are determined by the patient’s body weight (see the label for a guide). Treatment is administered orally, with water, in a single tablet intake. Source: European Summary of Product Characteristics for Mavenclad®

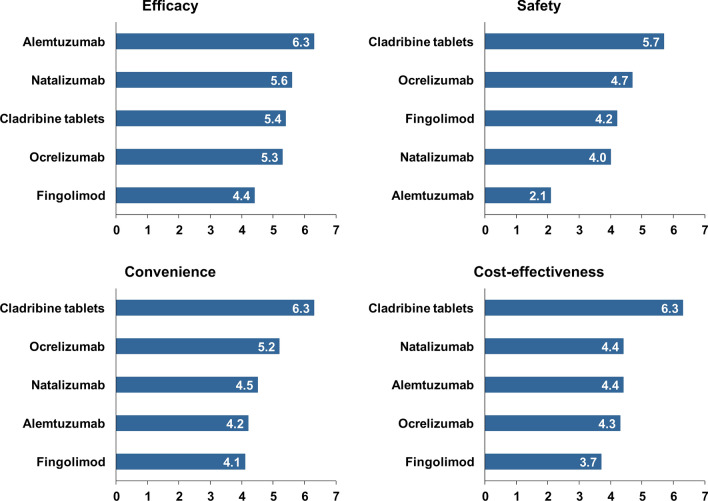

Overall Perceptions of High-EFFICACY DMTs

Experts scored individual DMTs against four attributes of treatment (efficacy, safety, convenience, and cost-effectiveness) in advance of the meeting (hence each expert initially rated each aspect of each DMT masked to the ratings made by other experts). These ratings are shown in Fig. 4. These ratings were the subject for further discussions during the meeting, but remained unchanged.

Fig. 4.

Experts’ perceptions of high-efficacy DMTs for the management of RRMS. Experts scored DMTs according to each attribute from 1 (lowest/worst) to 7 (highest/best) and bars show average rankings. See text for more details

Alemtuzumab was perceived to be the most effective treatment from this group and fingolimod was least effective. However, alemtuzumab was seen as having the most adverse safety profile (consistent with the data summarised for this agent above). Cladribine tablets were regarded as having the most favourable safety profile and were also rated highest for convenience of administration and overall cost-effectiveness.

Practical Aspects of Therapy with Cladribine Tablets

Administration and Monitoring

General Requirements

Box 1 summarises the administration of cladribine tablets. The treatment is administered as two short periods of oral treatment, 1 month apart. This treatment course is repeated at the start of the first month of the following year. Each day’s treatment intake is made up of a single intake of 10 mg tablets taken over 4–5 days: the labelling for the drug contains instructions on how many tablets the patient needs to take, based on their body weight. The overall dosage of cladribine is 3.5 mg/kg at the end of the second treatment course.

Table 1 summarises the screening requirements prior to administering cladribine tablets, based largely but not exclusively on European and US labelling. The lymphocyte count must be in the normal range before treatment initiation and must have recovered to at least 800/mm2 before administering the second course (delay the second course if necessary, to allow recovery of lymphocytes). It is important to screen for latent or pre-existing infections, particularly varicella/herpes zoster, hepatitis B or C, tuberculosis, or HIV. Active infections (including TB, hepatitis B or C, PML, or HIV) are contraindications to the use of cladribine tablets. Patients who have not been exposed to Varicella zoster virus (by an antibody test) can be vaccinated against this virus at least 4–6 weeks before starting treatment. Active malignancy and moderate or severe renal or hepatic impairments are further contraindications and must be screened for and excluded in advance of treatment. Finally, an MRI scan should be performed at (or soon after) the time of treatment initiation to provide a new baseline for evaluation of the therapeutic response.

Table 1.

Summary of screening requirements at initiation of therapy and related contraindications to the use of cladribine tablets for RRMS

| Initiation and monitoring | Contraindications | |

|---|---|---|

| Lymphocyte count/immunosuppression | Lymphocytes must be in the noraml range (year 1) or ≥ 800/mm3 (year 2) before initiating cladribine tablets | Lymphocyte count < 800/mm3 before second course (monitor actively until recovery if lymphocyte count is < 500/mm3) |

| Do not initiate cladribine tablets if patient is on immunosuppressive or myelosuppressive therapy | ||

| Screen for immunocompromised status | ||

| Active chronic infection and vaccination | Screen for latent infections, especially TB and hepatitis B and C (prior to treatment in years 1 and 2) | Active chronic infection, e.g. TB or hepatitis |

| Exclude HIV infection before initiation | HIV infection | |

| Vaccinate patients who are antibody negative for Varicella zoster virus prior to initiation of therapy | Do not initiate cladribine tablets within 4–6 weeks after vaccination with live or attenuated vaccines | |

| PML | ||

| Malignancy | Screen for active malignancy before initiation of therapy | Active malignancy |

| Renal or hepatic impairment | Screen for renal or hepatic impairment prior to initiation | Moderate or severe renal or hepatic impairment |

| MRI | A baseline MRI should be performed before initiating cladribine tablets (usually within 3 months) | None |

| Pregnancy and breastfeeding | Exclude pregnancy before initiation of cladribine tablets in Years 1 and 2 | Pregnancy |

| Maintain contraception during treatment and for at ≥ 6 months after the last dose | Breastfeeding is contraindicated during treatment with Cladribine Tablets and for 1 week after the last dose |

HIV human immunodeficiency virus, PML progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, TB tuberculosis;

Special Consideration-Latent Tuberculosis

Importantly for healthcare professionals in the UAE, there are no additional screening tests needed in advance of administration of cladribine tablets in that country over and above those specified in the product labelling. Overall, the experts regarded the burden of monitoring associated with treatment with cladribine tablets to be low.

Special attention must be made to the labelling requirement to exclude latent TB infection. Latent TB infection is not uncommon in the UAE, as in other countries of the Middle East, particularly where residents have travelled to TB-endemic areas or have been in contact with others who have [55]. It is recommended to prescribe the 3-month isoniazid/rifapentine protocol [56] for a patient with latent TB, starting treatment 1 month before initiating cladribine tablets and continuing for 2 months after. Physicians who are not experienced in the management of TB are encouraged to consult with specialists in infectious disease or pulmonology.

Family Planning

Pregnancy is a formal contraindication to the use of cladribine tablets (Table 1). The possibility of pregnancy must be excluded before starting treatment, and the labelling requires the use of adequate contraception during treatment with cladribine tablets and for 6 months after the last dose. Many pregnancies are unplanned, however, and it is inevitable that some will be exposed to treatments contraindicated at this time. Clinical experience on pregnancies exposed to cladribine tablets is limited to a survey of 64 pregnancies, which did not report an increased risk of adverse maternal or foetal outcomes [57]. Women who become pregnant within 6 months of a dose of cladribine tablets who wish to continue their pregnancy should be monitored carefully.

If a patient becomes pregnant after the first treatment course of cladribine tablets, the second course must be withheld until after delivery. A patient who develops significant MS disease activity at this time presents a difficult challenge for clinical management, as the risk to the pregnancy from a severe relapse must be balanced with perceived risks from treatment with a DMT. If the physician concludes that a DMT is required, interferon beta is now indicated in Europe for use during pregnancy. If a high-efficacy DMT is needed, most physicians would consider the use of natalizumab during pregnancy up to week 30, based on experience in pregnant women [58–60] and the lack of a formal contraindication for this treatment in Europe or the USA. It should be noted that the continued use of natalizumab to delivery risks the development of haematologic abnormalities in the neonate [61].

The treatment course for cladribine tablets normally takes place over a total of 13 months and 1 week, and patients should avoid being pregnant for at least 6 months after the last dose. Accordingly, patients of childbearing potential and planning to raise a family must commit to avoiding pregnancy for a minimum of 19 months (and 1 week) after taking their first cladribine tablet (and possibly longer if the second course needs to be delayed to allow recovery of lymphocytes or to deal with an infection). If the patient responds to the treatment with an absence of relapses (as did 75% of patients during up to 4 years of follow-up in the CLARITY Extension [28]) or NEDA (as did 46% of patients [30]), this can provide a window of opportunity to complete a pregnancy free of constraints from either MS disease activity or treatment with a DMT [7].

Treatment with cladribine tablets is also contraindicated during breastfeeding. Women should not breastfeed their baby for at least 1 week after the last dose of cladribine tablets.

Vaccination

The European and US labels for cladribine tablets recommend that treatment with cladribine tablets should not be initiated within 4 to 6 weeks after vaccination with live or attenuated live vaccines to reduce the risk of vaccine-induced infections associated with reduced lymphocyte counts. After starting cladribine tablets, live and attenuated vaccines can be given after the lymphocytes return to normal levels. Live-attenuated vaccines should not be given to patients who have received cladribine tablets while lymphocyte counts are depressed.

At the time of writing, novel vaccines directed against SARS-CoV-2 (see below) are in the final stages of development, and mass vaccination programmes are being rolled out. Current knowledge regarding vaccination for COVID-19 in patients under treatment for MS with cladribine tablets is summarised in the following section.

COVID-19 and Cladribine Tablets

Impact of Treatment on COVID-19 Outcomes

Clinical data to date suggest that the incidence of viral respiratory infections has not been higher in patients with MS who received cladribine tablets relative to placebo during clinical trials (to October 2018) and that no safety signals relating to respiratory coral infections have emerged in real-world data to January 2020 [62]. In addition, initial experience in people with MS who developed COVID-19 after having received cladribine tablets found that the severity of COVID-19 was almost universally low, the severity of COVID-19 was almost always mild or moderate, and the patients developed antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 virus, even in the setting of cladribine-associated lymphopenia [63, 64].

A retrospective review of 844 patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 in Italy found no association between receipt of a DMT and adverse COVID-19 outcomes other than a 2.4-fold increase in the risk of severe COVID-19 in patients receiving an anti-CD20 agent [65]. There were few patients who had received cladribine tablets in this study, and this treatment was pooled with alemtuzumab (there was no increase in risk of adverse outcomes for this group) [65]. An association between anti-CD20 agents and adverse COVID-19 outcomes has been observed in other observational cohorts [66, 67], but not in the pharmacovigilance database of the pharmaceutical sponsor of ocrelizumab [68]. Recent receipt of a corticosteroid was another risk factors for a more severe outcome in the study in Italy [65], and older age, a progressive MS phenotype, and male gender have emerged as risk factors for adverse COVID-19 outcomes elsewhere [69].

Theoretical considerations suggest that different DMTs may have been associated with greater or lesser risks of adverse outcomes for a patient with MS who develops COVID-19 [70]. However, data so far do not support a clear or consistent adverse association between COVID-19 infection and adverse outcomes in subjects with MS who have received a DMT [71]. Accordingly, the experts supported a policy of continuing to manage their patients with MS as previously, including use of DMTs, as recommended by physicians elsewhere in the Middle East [72]. In general, the experts here did not consider the COVID-19 pandemic to represent a barrier per se to the use of cladribine tablets for a patient without symptoms of this condition, especially with regard to administration of the second annual treatment course. As always, potential risks and benefits must be discussed carefully with the patient.

Vaccination for COVID-19 During Treatment with Cladribine Tablets

The vaccines against COVID-19 available to date are not live or live-attenuated vaccines and are thus not subject to restrictions limiting the use of such vaccines in potentially immunocompromised patients (see above). Thus, treatment with cladribine tablets is not a reason to withhold vaccination against COVID-19 per se.

Data are not available at this time from patients treated with cladribine tablets on the ability of vaccines against COVID-19 to prevent patients catching the virus or on the severity of COVID-19 in patients who do contract it. Case reports have described robust immunological responses to COVID-19 infection in two patients who were receiving cladribine tablets [64]. In addition, immunological responses to influenza or varicella zoster vaccines observed in patients in year 1 or 2 of treatment with cladribine tablets were considered sufficient to prevent the onset of these diseases in exposed patients [73, 74].

In practice, the decision on the timing of vaccination will be shared between the patient and the physician. This will depend on multiple factors such as the patient’s immunological status, the local prevalence of COVID-19, and whether or not the patient has risk factors for a severe adverse outcome from a COVID-19 infection.

Discussion

Box 2 summarises the published evidence that helps to identify the most appropriate subgroups of patients for treatment with cladribine tablets. Data from the CLARITY study and elsewhere confirm that treatment of people with RRMS with cladribine tablets is effective (with the majority of patients free of relapses for 2 years following a 2-year course of treatment). This treatment is also well tolerated, with a low potential for infection (where common, latent, or pre-existing infections are excluded or treated) and a low potential for malignancy.

The pivotal CLARITY study was conducted in patients with active RRMS defined as one relapse in the previous year or two relapses in the previous 2 years [25]. This relapse history reflected one of the clinical scenarios presented to the expert group described above. Interestingly, while there was clear majority support for using cladribine tablets in such patients, support was stronger for the use of this treatment in patients with higher-risk presentations, based on two relapses in the previous year plus MRI activity or one relapse in the previous year with either MRI activity in high-risk areas of the central nervous system or other markers of poor prognosis. This group therefore viewed cladribine tablets as a treatment for “highly active” RRMS, with some emphasis on patients with a more severe presentation than that seen in the overall population of CLARITY. This is consistent with the results of the post hoc analysis of the CLARITY study that suggested reduced progression of MS-related disability in patients with vs. without a higher frequency of relapses [31]. Post hoc data are hypothesis generating and this finding requires confirmation, however. “High disease activity” is not well defined as a basis for therapeutic indications, and its definition for the therapeutic use of individual DMTs tends to reflect the patient populations of the Phase 3 trials that supported its introduction [72]. For the future, a more consistent definition of “high disease activity” in RRMS would be useful.

A switch to cladribine tablets may be conducted in a search for greater efficacy against MS disease activity. Head-to-head studies comparing cladribine tablets with other DMTs have not been conducted. An observational study involving propensity score matching the CLARITY trial population with subjects in a database in Italy suggested the annualised relapse rate for cladribine tablets was lower than that seen with first-line DMTs, was similar to that seen with fingolimod, and was lower than that seen with natalizumab [75]. The prospect of a prolonged period (years) free of MS disease activity in the absence of continued, regular dosing with medication is an important feature of DMTs with an IRT-like mechanism that is not shared by continuously administered agents, however. Poor adherence to DMT regiments is common among patients with MS and due to multiple factors including side effects, efficacy, dissatisfaction with treatment, and demographic and other factors [76, 77]. Intensive monitoring requirements or the need to visit hospitals for infusions of some DMTs adds to the burden of treatment with some DMTs [78]. The IRT approach renders these issues moot [18, 36, 79, 80]: for example, for a patient who responds to treatment with cladribine tablets there is no need for regular intakes of treatment or for continued monitoring beyond 6 months of the last dose (or the recovery of lymphocytes, if this takes longer). This expert group supported this principle, as their support for the use of cladribine tablets in CLARITY-like patients (one relapse in the previous year or 2 relapses in the previous 2 years) was stronger if the patient’s lifestyle preferences mitigated against the use of continuous treatment or if the patient was likely to be non-compliant with this approach. As the administration of cladribine tablets requires a total of only 16–20 days of treatment intakes over the total treatment course, it is feasible to make arrangements for a (potentially) non-compliant patient to take the cladribine tablets under medical supervision. The IRT concept may also provide flexibility for family planning, as described above.

Box 2: Published information on the use of cladribine tablets in specific subpopulations of people with RRMS.

| Patients with higher MS disease activity | The CLARITY Study [22] demonstrated reduced relapse rates over 2 years of randomised treatment in patients with active RRMS at baseline (one relapse in the previous year or two relapses in the previous 2 years |

| 2-year extension to CLARITY demonstrated reduced relapse rate [25], reduced MRI progression [24, 26], and increased achievement of NEDA-3 [27] without further treatment; about 75% of patients who had received cladribine tablets in the randomised phase remained relapse-free when cladribine tablets were switched to placebo for a further 2 years | |

| Post hoc analysis from CLARITY suggested reduced 6-month progression of disability in patients with vs. without high disease activity at baseline (≤ 2 relapses during the year prior to study entry), irrespective of prior treatment with a disease-modifying therapy [28] | |

| Patients considered unlikely to adhere well to a continuous DMT regimen | Long-term freedom from disease activity without continuous treatment is possible for a majority of patients treated with the 2-year course of cladribine tablets (see above)a |

| Patients planning a family | Long-term freedom from MS disease activity following the initial 2-year course of treatment (see above) may provide a window of opportunity to complete a pregnancy uncomplicated by concurrent administration of a DMTa |

aAlso applies in principle to any disease-modifying therapy (DMT) that acts like an immune reconstitution therapy (e.g. alemtuzumab); NEDA: no evident disease activity

Conclusions

In conclusion, treatment with an IRT-like DMT provides opportunity for prolonged freedom from RRMS and its treatment (including regular monitoring) for a substantial proportion of patients with relatively high MS disease activity. We hope that our recommendations on the use of cladribine tablets for these patients help practising physicians to identify the most suitable patients for this treatment and to apply it correctly. Such considerations will be even more important as we recover our routine practice following the disruptions to the care of people with MS during the global SARS-CoV2 pandemic [71].

Acknowledgements

Funding

Merck Serono Middle East FZ, Ltd., an affiliate of Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany, funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee. The authors received no payment for contributing to this article.

Editorial Assistance

A medical writer (Dr Mike Gwilt, GT Communications) provided editorial assistance (funded by Merck Serono Middle East FZ Ltd., an affiliate of Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

All co-authors contributed substantially to the conception, design, content, and interpretation of data in the article, participated in its drafting and critical revision for intellectual content, approved the final version for submission, and acknowledge that they are accountable for all aspects of the article. The co-authors of the article remained in control of its content throughout.

Disclosures

This article arose from discussions at a meeting funded by Merck Serono Middle East FZ, Ltd., an affiliate of Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Additionally, Dr Ahmed Osman Shatila reports honoraria for lectures (Sanofi-Genzyme, Merck, Genpharm, Roche, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Biologix) and for advisory boards (Sanofi-Genzyme, Roche, Novartis, Pfizer, Biologix); educational conference travel and registration and hotel accommodation have been sponsored by Sanofi-Genzyme, Merck, Genpharm, Roche, Novartis, and Biologix. Dr Taoufik Alsaadi has received consulting fees, honoraria, and research grants from Novartis, Newbridge, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Hekma, Cyberonics, and Sanofi. MS received honoraria from Merck, Biogen, Novartis, and Sanofi. Dr Amir Boshra is an employee of Merck Serono Middle East FZ, Ltd., Dubai, UAE, an affiliate of Merck KgaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Drs Jihad S Inshasi, Sarmed Alfahad, Ali Hassan, Tayseer Zein, Victoria Ann Mifsud, Suzan Ibrahim Nouri, Mustafa Shakra, Miklos Szolics, Mona Thakre, and Ajit Kumar reported no other conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This narrative review article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Global Media Insight. United Arab Emirates population statistics. 2020. https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/uae-population-statistics/. Accessed Nov 2020.

- 2.Reich D, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA. Multiple Sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:169–180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1401483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed M, Mir R, Shakra M, Al FS. Multiple sclerosis in the emirati population: onset disease characterization by MR imaging. Mult Scler Int. 2019;2019:7460213. doi: 10.1155/2019/7460213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inshasi J, Thakre M. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Int J Neurosci. 2011;121:393–398. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2011.565893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiess N, Huether K, Fatafta T, et al. How global MS prevalence is changing: a retrospective chart review in the United Arab Emirates. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;9:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohammed EMA. Multiple sclerosis is prominent in the Gulf states: review. Pathogenesis. 2016;3:19–38. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alroughani R, Inshasi J, Al-Asmi A, et al. Disease-modifying drugs and family planning in people with multiple sclerosis: a consensus narrative review from the Gulf Region. Neurol Ther. 2020;9:265–280. doi: 10.1007/s40120-020-00201-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamout B, Sahraian M, Bohlega S, et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis: 2019 revisions to the MENACTRIMS guidelines. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;37:101459. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.101459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24:96–120. doi: 10.1177/1352458517751049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90:777–788. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghezzi A. European and American guidelines for multiple sclerosis treatment. Neurol Ther. 2018;7:189–194. doi: 10.1007/s40120-018-0112-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alroughani R, Inshasi JS, Deleu D, et al. An overview of high-efficacy drugs for multiple sclerosis: Gulf region expert opinion. Neurol Ther. 2019;8:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s40120-019-0129-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauser SL, Cree BAC. Treatment of multiple sclerosis: a review. Am J Med. 2020;S0002–9343(20):30602–30611. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Florou D, Katsara M, Feehan J, Dardiotis E, Apostolopoulos V. Anti-CD20 agents for multiple sclerosis: spotlight on ocrelizumab and ofatumumab. Brain Sci. 2020;10:758. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10100758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giovannoni G. Disease-modifying treatments for early and advanced multiple sclerosis: a new treatment paradigm. Curr Opin Neurol. 2018;31:233–243. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kieseier BC. The mechanism of action of interferon-β in relapsing multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:491–502. doi: 10.2165/11591110-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziemssen T, Schrempf W. Glatiramer acetate: mechanisms of action in multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;79:537–570. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)79024-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.AlSharoqi IA, Aljumah M, Bohlega S, et al. Immune reconstitution therapy or continuous immunosuppression for the management of active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients? A narrative review. Neurol Ther. 2020;9(1):55–66. doi: 10.1007/s40120-020-00187-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuve O, Soelberg Soerensen P, Leist T, et al. Effects of cladribine tablets on lymphocyte subsets in patients with multiple sclerosis: an extended analysis of surface markers. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:1756286419854986. doi: 10.1177/1756286419854986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leist TP, Weissert R. Cladribine: mode of action and implications for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34:28–35. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e318204cd90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Zwan M, Baan CC, van Gelder T, Hesselink DA. Review of the clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of alemtuzumab and its use in kidney transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;57:191–207. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0573-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gross CC, Ahmetspahic D, Ruck T, Schulte-Mecklenbeck A, Schwarte K, Jörgens S, Scheu S, Windhagen S, Graefe B, Melzer N, Klotz L, Arolt V, Wiendl H, Meuth SG, Alferink J. Alemtuzumab treatment alters circulating innate immune cells in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2016;3:e289. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas K, Eisele J, Rodriguez-Leal FA, Hainke U, Ziemssen T. Acute effects of alemtuzumab infusion in patients with active relapsing-remitting MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2016;3:e228. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baker D, Giovannoni G, Schmierer K. Marked neutropenia: Significant but rare in people with multiple sclerosis after alemtuzumab treatment. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;18:181–183. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2017.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giovannoni G, Comi G, Cook S, Rammohan K, Rieckmann P, Soelberg-Sørensen P, Vermersch P, Chang P, Hamlett A, Musch B, Greenberg SJ; CLARITY Study Group. A placebo-controlled trial of oral cladribine for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:416–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Cook S, Comi G, Rieckmann P et al. Safety and tolerability of cladribine tablets in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS): final results from the 120-week phase 3b extension trial to the CLARITY study. In: Poster presented at: 68th American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting; April 15–21, 2016; Vancouver, BC, Canada. Poster P3.095.

- 27.Comi G, Cook SD, Giovannoni G, Rammohan K, Rieckmann P, Sørensen PS, Vermersch P, Hamlett AC, Viglietta V, Greenberg SJ. MRI outcomes with cladribine tablets for multiple sclerosis in the CLARITY study. J Neurol. 2013;260:1136–1146. doi: 10.1007/s00415-012-6775-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giovannoni G, Soelberg Sorensen P, et al. Safety and efficacy of cladribine tablets in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: Results from the randomized extension trial of the CLARITY study. Multiple Sclerosis J. 2018;24:1594–1604. doi: 10.1177/1352458517727603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comi G, Cook S, Rammohan K, Soelberg Sorensen P, Vermersch P, Adeniji AK, Dangond F, Giovannoni G. Long-term effects of cladribine tablets on MRI activity outcomes in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: the CLARITY Extension study. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2018. (advance publication online). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Giovannoni G, Keller B, Jack D. Durability of NEDA-3 status in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis receiving cladribine tablets: CLARITY Extension (P3.2–100). Neurol 2019; 92(15 Supplement):Abstract P3.2–100. https://n.neurology.org/content/92/15_Supplement/P3.2-100. Accessed Nov 2020.

- 31.Giovannoni G, Soelberg Sorensen P, Cook S, et al. Efficacy of Cladribine Tablets in high disease activity subgroups of patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a post hoc analysis of the CLARITY study. Mult Scler. 2019;25:819–827. doi: 10.1177/1352458518771875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coles AJ, Cohen JA, Fox EJ, et al. Alemtuzumab CARE-MS II 5-year follow-up: efficacy and safety findings. Neurology. 2017;89:1117–1126. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorensen PS, Sellebjerg F. Pulsed immune reconstitution therapy in multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;28(12):1756286419836913. doi: 10.1177/1756286419836913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leist TP, Comi G, Cree BA, et al. Effect of oral cladribine on time to conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis in patients with a first demyelinating event (ORACLE MS): a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:257–267. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freedman MS, Leist TP, Comi G, et al. The efficacy of cladribine tablets in CIS patients retrospectively assigned the diagnosis of MS using modern criteria: results from the ORACLE-MS study. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2017;3:2055217317732802. doi: 10.1177/2055217317732802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brod SA. In MS: immunosuppression is passé. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;40:101967. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.101967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Celius EG. Infections in patients with multiple sclerosis: Implications for disease-modifying therapy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(Suppl 201):34–36. doi: 10.1111/ane.12835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Epstein DJ, Dunn J, Deresinski S. Infectious complications of multiple sclerosis therapies: implications for screening, prophylaxis, and management. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018;5:ofy174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Lebrun C, Rocher F. Cancer risk in patients with multiple sclerosis: potential impact of disease-modifying drugs. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:939–949. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0564-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ragonese P, Aridon P, Vazzoler G, et al. Association between multiple sclerosis, cancer risk, and immunosuppressant treatment: a cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:155. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0932-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelsey R. The risk of natalizumabassociated PML is revealed. Nature Milestones. 2018. https://www.nature.com/articles/d42859-018-00025-5. Accessed Nov 2020.

- 42.Clifford DB, Gass, A, Richert N, et al. Cases reported as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in ocrelizumab-treated patients with multiple sclerosis. Poster P97 presented at the 35th Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis (ECTRIMS), 11–13 September 2019; Stockholm, Sweden. 2019. https://bit.ly/3pozMYB. Accessed Jan 2021.

- 43.Berger JR, Malik V, Lacey S, Brunetta P, Lehane PB. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in rituximab-treated rheumatic diseases: a rare event. J Neurovirol. 2018;24:323–331. doi: 10.1007/s13365-018-0615-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yukitake M. Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2018;9:34–47. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Camm J, Hla T, Bakshi R, Brinkmann V. Cardiac and vascular effects of fingolimod: mechanistic basis and clinical implications. Am Heart J. 2014;168:632–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cook S, Leist T, Comi G, et al. Safety of cladribine tablets in the treatment of patients with multiple sclerosis: an integrated analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;29:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prosperini L, Haggiag S, Tortorella C, Galgani S, Gasperini C. Age-related adverse events of disease-modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis: a meta-regression [published online ahead of print, 2020 Oct 26]. Mult Scler 2020;1352458520964778. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Pakpoor J, Disanto G, Altmann DR, Pavitt S, Turner BP, Marta M, Juliusson G, Baker D, Chataway J, Schmierer K. No evidence for higher risk of cancer in patients with multiple sclerosis taking cladribine. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2:e158. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.European Medicines Agency. Assessment report. MAVENCLAD. International non-proprietary name: cladribine. Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/004230/0000. 2017. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/004230/WC500234563.pdf. Accessed Jan 2019.

- 50.European Medicines Agency. Measures to minimise risk of serious side effects of multiple sclerosis medicine Lemtrada. 2019. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/lemtrada. Accessed Nov 2020.

- 51.Bergamaschi R. Prognostic factors in multiple sclerosis. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;79:423–447. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)79019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giovannoni G, Hawkes C, Waubant E, Lublin F. The 'Field Hypothesis': rebound activity after stopping disease-modifying therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;15:A1–A2. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prosperini L, Kinkel RP, Miravalle AA, Iaffaldano P, Fantaccini S. Post-natalizumab disease reactivation in multiple sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2019;12:1756286419837809. doi: 10.1177/1756286419837809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gasperini C, Prosperini L, Tintoré M, et al. Unraveling treatment response in multiple sclerosis: a clinical and MRI challenge. Neurology. 2019;92:180–192. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Almarzooqi F, Alkhemeiri A, Aljaberi A, Hashmey R, Zoubeidi T, Souid AK. Prospective cross-sectional study of tuberculosis screening in United Arab Emirates. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;70:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment Regimens for Latent TB Infection (LTBI). 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm. Accessed Nov 2020.

- 57.Galazka A, Nolting A, Cook S, et al. Pregnancy outcomes during the clinical development programme of cladribine in multiple sclerosis (MS): an integrated analysis of safety for all exposed patients. In: Abstract (P1874) at the ECTRIMS 2017 congress. 2020. https://onlinelibrary.ectrims-congress.eu/ectrims/2017/ACTRIMS-ECTRIMS2017/199894/vicky.john.pregnancy.outcomes.during.the.clinical.development.programme.of.html. Accessed Oct 2020.

- 58.Ebrahimi N, Herbstritt S, Gold R, Amezcua L, Koren G, Hellwig K. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes following natalizumab exposure in pregnancy. A prospective, controlled observational study. Mult Scler 2015;21:198–205. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Portaccio E, Annovazzi P, Ghezzi A, et al. Pregnancy decision-making in women with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab: I: Fetal risks. Neurology. 2018;90:e823–e831. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friend S, Richman S, Bloomgren G, Cristiano LM, Wenten M. Evaluation of pregnancy outcomes from the Tysabri® (natalizumab) pregnancy exposure registry: a global, observational, follow-up study. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:150. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0674-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haghikia A, Langer-Gould A, Rellensmann G, et al. Natalizumab use during the third trimester of pregnancy. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:891–895. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cook S, Giovannoni G, Leist T et al. Updated Safety of Cladribine Tablets in the Treatment of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: Integrated Safety Analysis and Post-approval Data. In: Abstract 0415 at the 2020 meeting of the European Committee for Research and Treatment in Multiple Sclerosis and American Committee for Research and Treatment in Multiple Sclerosis.

- 63.Jack D, Nolting A, Galazka A. Favorable outcomes after COVID-19 infection in multiple sclerosis patients treated with cladribine tablets. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;46:102469. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Angelis M, Petracca M, Lanzillo R, Brescia Morra V, Moccia M. Mild or no COVID-19 symptoms in cladribine-treated multiple sclerosis: Two cases and implications for clinical practice. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;45:102452. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sormani MP, De-Rossi N, Schiavetti I, et al. Disease-Modifying Therapies and Coronavirus Disease 2019 Severity in Multiple Sclerosis [published online ahead of print, 2021 Jan 21] Ann Neurol. 2019 doi: 10.1002/ana.26028). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simpson-Yap S, De Brouwer E, Kalincik T, et al. First results of the COVID-19 in MS Global Data Sharing Initiative suggest antiCD20 DMTs are associated with worse COVID-19 outcomes. In: Abstract SS02–4.04, presented at the MSVirtual2020: 8th Joint ACTRIMS-ECTRIMS Meeting. 2020. https://msvirtual2020.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/SS02.04.pdf. Accessed Mar 2021.

- 67.MS Covid-19 Meeting. 2020. https://multiple-sclerosis-research.org/2020/05/mscovid19-swedish-experience. Accessed Mar 2020.

- 68.Hughes R, Pedotti R, Koendgen H. COVID-19 in persons with multiple sclerosis treated with ocrelizumab—a pharmacovigilance case series. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2020;42:102192. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hughes S. Increased risk of severe COVID with anti-b-cell MS drugs? Medscape. 2021. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/938277. Accessed Mar 2021.

- 70.Zheng C, Kar I, Chen CK, et al. Multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapy and the COVID-19 pandemic: implications on the risk of infection and future vaccination. CNS Drugs. 2020;34:879–896. doi: 10.1007/s40263-020-00756-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salama S, Ahmed SF, Ibrahim Ismail I, Alroughani R. Impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on multiple sclerosis care. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2020;197:106203. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alroughani R, Inshasi J, Al-Asmi A, et al. Expert consensus from the Arabian Gulf on selecting disease-modifying treatment for people with multiple sclerosis according to disease activity. Postgrad Med. 2020;132:368–376. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1734394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roy S, Boschert U. Analysis of influenza and varicella zoster virus vaccine antibody titers in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine tablets. In: Abstract P059 presented at the ACTRIMS Virtual Forum. 2021. https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/9245/session/23. Accessed Mar 2021.

- 74.Wu GF, Boschert U, Hayward B, Lebson LA, Cross AH. Evaluating the impact of cladribine tablets on the development of antibody titres: interim results from the CLOCK-MS Influenza Vaccine Sub-Study. In: Abstract P071 presented at the ACTRIMS Virtual Forum. 2021. https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/9245/session/23. Accessed Mar 2021.

- 75.Signori A, Saccà F, Lanzillo R, et al. Cladribine vs other drugs in MS: Merging randomized trial with real-life data. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7:e878. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Remington G, Rodriguez Y, Logan D, Williamson C, Treadaway K. Facilitating medication adherence in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2013;15:36–45. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2011-038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morillo Verdugo R, Ramírez Herráiz E, Fernández-Del Olmo R, Roig Bonet M, Valdivia GM. Adherence to disease-modifying treatments in patients with multiple sclerosis in Spain. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:261–272. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S187983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Deleu D, Canibaño B, Mesraoua B, Adeli G, Abdelmoneim MS, Ali Y, Elalamy O, Melikyan G, Boshra A. Management of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis in Qatar: an expert consensus. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36:251–260. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2019.1669378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Inshasi JS, Almadani A, Fahad SA, et al. High-efficacy therapies for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: implications for adherence. An expert opinion from the United Arab Emirates. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2020;10:257–266. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2020-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.AlJumah M, Alkhawajah MM, Qureshi S, et al. Cladribine tablets and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a pragmatic, narrative review of what physicians need to know. Neurol Ther. 2020;9:11–23. doi: 10.1007/s40120-020-00177-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]