Abstract

Sigma-1 receptor (Sig-1R) is a protein present in several organs such as brain, lung, and heart. In a cell, Sig-1R is mainly located across the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum and more specifically at the mitochondria-associated membranes. Despite numerous studies showing that Sig-1R could be targeted to rescue several cellular mechanisms in different pathological conditions, less is known about its fundamental relevance. In this review, we report results from various studies and focus on the importance of Sig-1R in physiological conditions by comparing Sig-1R KO mice to wild-type mice in order to investigate the fundamental functions of Sig-1R. We note that the Sig-1R deletion induces cognitive, psychiatric, and motor dysfunctions, but also alters metabolism of heart. Finally, taken together, observations from different experiments demonstrate that those dysfunctions are correlated to poor regulation of ER and mitochondria metabolism altered by stress, which could occur with aging.

Keywords: Sigma-1 receptor, Endoplasmic reticulum, Mitochondria, Neurodegenerative disorders

Introduction

The discovery of Sig-1R dates back to Martin’s hypothesis of multiple opioid receptors (Martin et al. 1976). This hypothesis defined the various effects of morphine and its analogs by the numerous subtypes of opioid receptors. The first mention of Sig-1R was made by Su (Su 1982), but as a sigma “opioid’ receptor because of its ability to bind to [3H]N-allylnormetazocine (SKF-10047). However, the receptor observed by Su did not share other characteristics of the opioid receptor family in terms of function, structure, or homology of sequence. Later findings proved that Sig-1R, contrary to all other opioid receptor subtypes, has a very low affinity with naltrexone, does not have 7 transmembrane spanning regions, and shares no clear homology with other mammalian proteins (Ossa et al. 2017). Six years after this first publication, the receptor observed by Su et al. was then identified as a sigma receptor to be separated from the opioid receptor family (Su et al. 1988). In 1990, this receptor was named sigma-1 receptor to be distinguished from sigma-2 receptor, which also has an affinity with ditolyguanidine (Hellewell and Bowen 1990). Finally, the first model of Sig-1R knockout mice was generated by Langa et al. in 2003 (Langa et al. 2003).

Successful sequencing of Sig-1R (Hanner et al. 1996; Kekuda et al. 1996; Seth et al. 1997) was an asset to numerous studies and improved the understanding of the biological functions of the receptor. Sig-1R is now known as 223aa receptor chaperone protein, sensitive to calcium variations (Hayashi and Su 2007). One of the main actions of Sig-1R takes place at the mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs) where it resides primarily. Here, from the MAMs, Sig-1R is able to regulate cell stress.

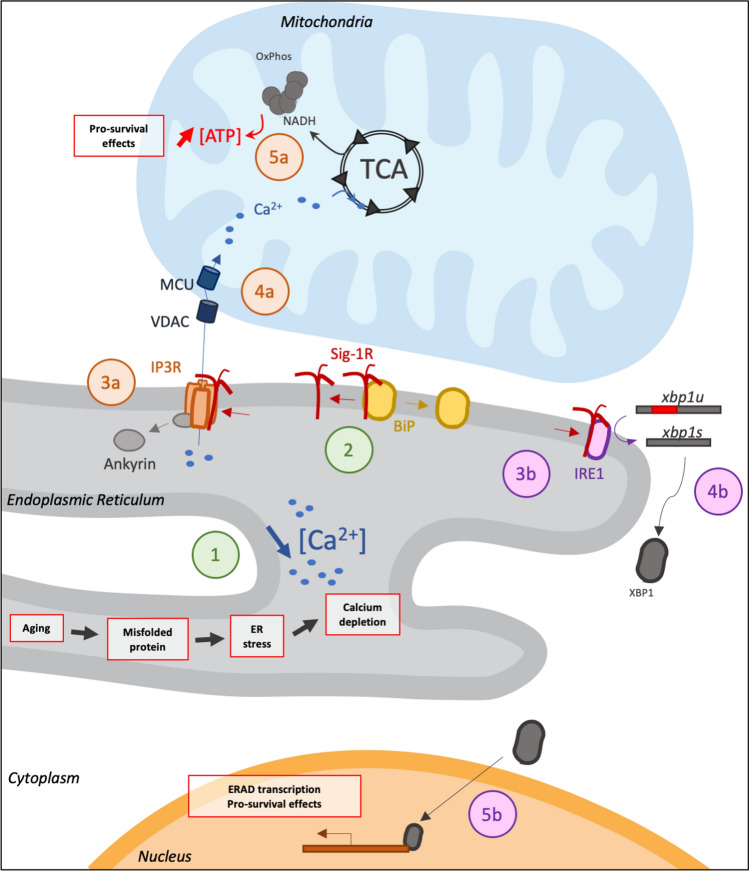

IP3R and Mitochondria Calcium Influx

With a basal ER calcium level, Sig-1R is mainly associated with another chaperon protein, Binding Immunoglobulin Protein (BiP, also known as GRP78), at the MAM. Bound together, these chaperone proteins have a weaker chaperone activity. After the decrease of calcium concentration in the ER, Sig-1R and BiP tend to separate from each other (Hayashi and Su 2007). This allows Sig-1R to increase its chaperone activity and to interact with inositol triphosphate receptor type3 receptor (IP3R) by disassociating IP3R from ankyrin (Hayashi and Su 2001). The interaction of Sig-1R and IP3R allows stabilization of IP3R and inhibits its degradation. This enhances in fine ATP production from mitochondria and increases cell survival during cellular stress (Eisner et al. 2018). Moreover, it was observed that the interaction of Sig-1R with an agonist has the same effect as a Ca2+ ER depletion. The use of Sig-1R agonist is also able to dissociate Sig-1R from IP3R (Hayashi and Su 2007). However, an overload of Ca2+ into mitochondria could lead to cell death (Walter and Hajnóczky 2005). Interestingly, this action could be related to the bell shape dose effect observed when Sig-1R agonists are used, i.e., too high or too low administration of agonist fails to reverse pathologic phenotypes (Maurice and Privat 1997; Meunier et al. 2006).

Unfolded Protein Response

From the MAM, activation of Sig-1R plays another important role for cell homeostasis. Indeed, Sig-1R is also involved in the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR). Sig-1R has been shown to interact with IRE1 (Mori et al. 2013). In short, the activation of IRE1 by Sig-1R can increase the endonuclease activity of IRE1, which can cut an intron in xbp1 mRNA, allowing the correct translation of XBP1. Eventually, XBP1 translocates into the nucleus and increases the transcription of genes which code for proteins able to regulate stress in the ER such as p58IPK (Lee et al. 2003).

In addition to those functions, Sig-1R, upon activation, can translocate to other subcellular compartments and acts as a chaperone with many proteins from Emerin at the nuclear membrane, which alters chromatin, to plasma membrane proteins such as ion channels or neurotransmitter receptors. All of those actions are well reviewed (Su et al. 2016).

Few Sig-1R endogenous ligands are known. In 1988, Su et al. demonstrated that neurosteroids such as progesterone and pregnenolone sulfate have relatively high affinity with Sig-1R (Su et al. 1988). However, those molecules are known to be organ specific, while Sig-1R is ubiquitous. The questions of what the endogenous ligands of Sig-1R are and how do they bind to Sig-1R have been studied since 1994. Glennon et al. examined the high affinity between Sig-1R and phenylalkylamine-based molecules (Glennon et al. 1994). Later findings identified sphingolipid (Ramachandran et al. 2009) and Myristic acid (Tsai et al. 2015) as endogenous ligands of Sig-1R. Additionally, Fontanilla et al. (2009) found that DMT (N,N-Dimethyltryptamine), an endogenous molecule in the brain, has a relatively high affinity with Sig-1R. However, the question remains: How is Sig-1R activated in organs where no endogenous ligands are found? Does this activation only occur by calcium depletion?

On the contrary, exogenous ligands are various and several studies observed the modulation of Sig-1R through those ligands (Bolshakova et al. 2016; Vavers et al. 2019). As a receptor, Sig-1R could be activated or inactivated using exogenous ligands. The importance of Sig-1R in critical roles such as regulation of mitochondria and ER functions made Sig-1R a hot therapeutic target for several pathological conditions or diseases where those organelles are dysfunctional. In the last 2 years, activation or inactivation of Sig-1R has been reported to decrease pathological phenotypes in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Maurice et al. 2019), Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Francardo et al. 2019), Huntington disease (HD) (Jabłońska et al. 2020), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Ionescu et al. 2019), demonstrating the ongoing interest for Sig-1R therapy in the most common neurodegenerative disorders. The mechanisms and importance of Sig-1R in those contexts were recently reviewed by Ryskamp et al. (Ryskamp et al. 2019). Furthermore, Sig-1R is also involved in other diseases (Su et al. 2016) such as cardiac disorder (Lewis et al. 2020), chronic pain (Bravo-Caparrós et al. 2019; Bravo-Caparrós et al. 2020; Xiong et al. 2020), depression (Yang et al. 2019), addiction (Kourrich et al. 2013), and cancer (Palmer et al. 2007). In June 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved the first Sig-1R targeted drug, Fintepla, to treat seizures associated with Dravet syndrome. At least two other molecules are in clinical trials. ANAVEXTM 2-73 is being tested for Alzheimer’s disease and E-52962 to treat neuropathic pain. Finally, it is interesting to note that those molecules are, respectively, Sig-1R agonist and antagonist. A better understanding of the fundamental functions of Sig-1R will help to understand in which conditions the use of an agonist or an antagonist is beneficial or detrimental.

This ability of Sig-1R to be involved in several diseases is explained by its ubiquitous expression of its gene SIGMAR1. Several studies using different techniques in different models observed the presence of Sig-1R throughout mammal bodies (Fagerberg et al. 2014; Kitaichi et al. 2000; Novakova et al. 1995). Furthermore, expression of SIGMAR1 is observed in different cell lines generated from different organs such as ovary (Hayashi and Su 2007), liver (Christ et al. 2019), kidney (Johannessen et al. 2009), and brain (Su et al. 2014). Positron Emission Tomography (PET) also allows observation of the expression of Sig-1R and underlines the fact that Sig-1R expression could change with the physiopathological states of tissues (James et al. 2012). As Sig-1R has been shown to be critical in the nervous system, several studies focused on the expression of SIGMAR1 in the subcompartments of the brain (Alonso et al. 2000; Baum et al. 2017; Kitaichi et al. 2000; Lan et al. 2019; Seth et al. 2001). At the subcellular level, Sig-1R is present mainly at the MAM (Hayashi and Su 2007). However, when activated, Sig-1R could be translocated to different subcellular compartments, including the plasma membrane and the nuclear membrane (Su et al. 2016). This translocation allows Sig-1R to interact with other proteins from ion channels to transcriptional factors, increasing Sig-1R spectrum of functions.

Despite the numerous functions of Sig-1R and its ubiquitous localization, the absence of Sig-1R in KO mice has been less studied than the activation or inactivation of Sig-1R with exogenous ligands. In this review we will focus on the consequences of the absence of Sig-1R on both behaviors and cellular physiology to determine the fundamental functions of Sig-1R.

Effect of the Absence of Sig-1R on Behavior and Metabolism

Neuronal Functions

Cognition

The first report of Sig-1R KO mice was made by Langa et al. (2003). In that study, they observed no differences in any of the behavioral tests they conducted, suggesting that there were no cognitive deficits. However, other groups later tested cognitive functions in Sig-1R KO mice. Chevallier et al. (2011) reported that female Sig-1R KO mice showed deficits in working memory and spatial memory shown by Y-maze test and Morris water maze test, respectively. Moreover, using the step-through passive avoidance test (STPA), the authors demonstrated that stress-conditioned memory is altered in Sig-1R KO but only in 12-month-old homozygous females. Also, female heterozygous KO mice that did not show deficits in memory at 2 months of age began to show memory deficits at 12 months. Loss of Sig-1R protein-inducing memory deficit was also suggested in a male/female-mixed behavior test produced by Xu et al. (2017). WT and KO mice did not show any differences in the Morris water maze test, except the significantly increased escape time of KO mice during the training. However, KO mice showed a significant decrease in long-term memory efficiency but no defect in short term memory in the object recognition test, respectively, after a retention interval of 24 h or 1 h (Xu et al. 2017). Also, it was found that 17-β-estradiol levels were significantly decreased in homozygous KO females compared to WT. Furthermore an estradiol treatment in KO female animals significantly alleviated memory dysfunction where WT was unaffected by the treatment (Chevallier et al. 2011). Finally, Crouzier et al. (2020), using the Hamlet test, noted that physiological brain plasticity and topographic memory are altered in 7 to 9-week-old male Sig-1R KO mice compared to WT mice of the same age.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the absence of Sig-1R alters cognitive functions such as long-term memory, working memory, or stress-conditioned memory, especially in older mice. Furthermore, the absence of Sig-1R may have different consequences related to gender.

Motor Activity

In this section we will focus on motor-related behaviors, from spontaneous locomotion to motor coordination. The first observations of Sig-1R deletion on motor phenotypes were made by Langa et al. after generation of Sig-1R KO mice. Sig-1R was identified first as an SKF binding receptor (Su 1982). Firstly, Langa et al. confirmed that hyperactivity induced by SKF is blocked when Sig-1R is absent (Langa et al. 2003). However, they did not observe any differences between WT and Sig-1R KO in spontaneous locomotion in saline injected group. In this report, Langa et al. used males between 8 and 12 weeks old. In another study, Chevallier et al., did not observe differences between 8 week-old Sig-1R KO and WT in both males and females in distance traveled, locomotion speed, and duration of immobility in an open field (Chevallier et al. 2011). Nevertheless, in the Y-maze test (YMT), an increase in the number of entries in arms was observed in both male and female Sig-1R KO compared to WT mice. However, this result was not observed by Xu et al. using mixed group of males and females between 11 and 20 weeks old (Xu et al. 2017). Sabino et al. observed no locomotion differences between WT and Sig-1R KO males between 6 and 8 months old in open field (Sabino et al. 2009a). Furthermore, the total distance traveled by males aged between 12 weeks and 48 weeks in an open field was also observed in Hong et al. study (Hong et al. 2017). No difference was noted between WT and Sig-1R KO mice. Hong et al. observed that when using the beam straight walking test, Sig-1R male KO mice spent more time to cross the beam than WT between 24-week-old and 48-week-old but not at 12-week-old. Finally, Fontanilla et al. noted no differences in spontaneous locomotion in open field between WT and Sig-1R KO mice (Fontanilla et al. 2009). These results seem to show that spontaneous locomotion is not affected by the absence of Sig-1R.

Many studies also observed motor coordination in Sig-1R KO mice compared to WT through the use of the Rotarod. Bernard-Marissa et al. found that Sig-1R KO mice at 10 weeks and 20 weeks of age had lower scores with Rotarod test compared to age-matched WT (Bernard-Marissal et al. 2015). This result is also observable in Mavlyutov’s et al. study. In this study, weekly Rotarod scores of mice between 8 weeks old and 14 weeks old were observed. The authors noted that Sig-1R KO mice have lower scores than WT (Mavlyutov et al. 2010). Furthermore, this group also observed that the differences in the 14-week-old mice were larger compared to those of the 8-week-old mice, especially at constant speed. However, in the same study, Mavlyutov et al., observed no differences in the stride pattern at the same age they observed motor coordination deficit using footprint analysis. Nieto et al. found no differences using female mice with the Rotarod, but the age of the mice in this experiment is not mentioned (Nieto et al. 2012). Motor coordination was also examined by Hong et al. (2017). Interestingly, no difference was observed in Rotarod scores between WT and Sig-1R KO 12-week-old male mice. However, after 24 weeks and until the last measure at 48 weeks, the Rotarod score of Sig-1R KO males was lower than that of WT mice.

Bernard-Marissal et al. also showed that 20-week-old Sig-1R KO mice have lower muscle strength compared to WT mice (Bernard-Marissal et al. 2015). This result is confirmed by Hong et al., who also observed that muscle strength is lower in 48-week-old Sig-1R KO male mice compared to WT mice. However, before 48 weeks Hong et al. did not observe difference between the two genotypes. Despite the fact that the Rotarod is not used to measure muscle strength, Rotarod performances could be affected by decreased muscle strength (Foley et al. 2010; Gill et al. 2018).

Finally, some groups also examined swimming efficacy. In Mavlyutov’s study, it was observed that Sig-1R KO mice aged between 8 weeks and 14 weeks swim faster to reach a safe zone in a straight line than age-matched WT mice. This result correlates with a different swimming pattern (Mavlyutov et al. 2010). Chevallier et al. did not observe any change in swimming speed between Sig-1R KO and WT mice when using the water maze on either males or females at 8 weeks. Hong et al. did not observe swimming speed alterations in Sig-1R KO males aged between 12 and 48 weeks old compare to WT mice (Hong et al. 2017).

In conclusion, it appears that the main motor defects in Sig-1R KO mice are observable with the Rotarod, which is known to measure motor coordination. This result is correlated with an abnormal swimming pattern in Sig-1R KO mice. However, footprint analysis does not show any differences between Sig-1R KO and WT mice. Nevertheless, it should be noted that differences in muscle strength are measured and could influence the decrease in Rotarod scores.

Psychiatric-Related Behaviors

The association between Sig-1R and depression has been suggested by pharmacological studies, as Sig-1R agonists display an antidepressant-like action. Some studies have examined depressive-like behaviors in Sig-1R KO mice using the forced swimming test (FST) and tail suspension test (TST) (Akunne et al. 2001; Matsuno et al. 1996; Ukai 1998; Wang et al. 2007). Several studies reported consistent results that male Sig-1R KO mice, compared to WT, exhibited significantly higher immobility duration in the first 6 min of FST and TST tests, while female KO mice did not (Chevallier et al. 2011; Di et al. 2017; Sabino et al. 2009a; Sha et al. 2015). In the FST, typically, data are obtained between 1 and 6 min to evaluate antidepressant activity. However, Chevallier et al. performed an extensive two-session protocol of swimming for 15 min on the first day and 6 min on the second day. The authors noted that the difference in the immobility between male Sig-1R KO and WT mice on the first day was attenuated on the second day and female Sig-1R KO mice showed an increase in immobility from 6 to 10 min (Chevallier et al. 2011).

Sha et al. further examined effects of estradiol on the immobility of Sig-1R KO mice in the FST and TST (Sha et al. 2015) in order to explain the differences between males and females. They showed that there was no difference in corticosterone levels between WT and Sig-1R KO or male and female mice, respectively. Neither estradiol in females nor testosterone in males were different in WT and Sig-1R KO mice, although Chevallier et al. reported decreased estradiol levels in female Sig-1R KO mice (Chevallier et al. 2011). FST and TST were performed upon estradiol administration in male mice or removal of bilateral ovaries from female mice. The estradiol treatment abolished the increase of immobility in male Sig-1R KO mice, while it did not affect those in WT mice. Additionally, removing ovaries significantly increased immobility in female Sig-1R KO mice, indicating that estradiol eases the depressive-like behaviors in Sig-1R KO mice. The same group also indicated that PMA, a NMDA receptor agonist and a PKC activator, has a similar effect as estradiol. On the other hand, PP2, a Src inhibitor, attenuated the estradiol-reduced immobility in male Sig-1R KO mice and induced immobility in female Sig-1R KO mice in the FST and TST (Di et al. 2017; Sha et al. 2015). In order to investigate Sig-1R roles in postpartum depression, Zhang et al. applied hormone-simulated pregnancy and subsequent estradiol withdrawal to female mice, and found that those treatments caused significantly larger increase of immobility in Sig-1R KO mice, suggesting that the deficiency of Sig-1R worsens depressive-like behaviors in the postpartum model (Zhang et al. 2017).

A few studies have examined anxiety-like behaviors in Sig-1R KO mice. Sabino et al. used the elevated plus maze test and the light–dark transfer test. The apparatus of the elevated plus maze test consists of two open arms and two enclosed arms. The apparatus of the light–dark transfer test consists of two compartments; a larger compartment is brightly illuminated and a smaller one is dark. Rodents prefer enclosed or darker places over open or lighter places; therefore, an increase of time spent in the open or lighter spaces or number of entries to those areas is considered as a reduction of anxiety. Sabino et al. found no significant difference between male WT and Sig-1R KO mice in those two tests (Sabino et al. 2009a). In contrast, Chevallier et al. used male and female WT and Sig-1R KO mice in the elevated plus maze test and found that compared to WT, male Sig-1R KO mice showed a significant decrease in time spent in open arms, while female Sig-1R KO mice did not (Chevallier et al. 2011). The inconsistent results from those two studies might be due to different conditions, e.g., animal ages (respectively 6–8 months old vs. 2 months old) and the recording period (5 vs. 10 min). It should be mentioned that Chevallier et al. additionally observed increased anxiety states of male Sig-1R KO mice in distinct behavioral tests such as decreased time spent in the center in the open field test and increased latency to enter the dark compartment during training in the step-through passive avoidance test (Chevallier et al. 2011). Taken together, the absence of Sig-1R seems to trigger anxiety in male mice but not in females; however, further studies are needed to clarify a relationship between anxiety and Sig-1R functions.

One study has investigated alcohol-related behaviors using male Sig-1R KO mice (Valenza et al. 2016). Sig-1R KO mice showed significantly increased intake of ethanol compared to WT mice when mice were exposed to an alcohol solution either with ascending concentrations for 6 days each or with steady concentration for 14 days. It should be noted that Sig-1R KO mice did not show differences in water intake during the ethanol intake or taste perception. They also found that ethanol injection failed to stimulate locomotor activity in Sig-1R KO mice. The sedative effect of ethanol was evaluated in WT and Sig-1R KO mice using the loss of righting reflex experiment. Mice were injected with ethanol and placed on a V-shaped surface in the spine position. They recorded sleeping duration and latency to lose righting reflex, the time mice turn themselves back on to four paws from the ethanol injection and found that Sig1KO mice did not differ from WT mice. These data suggest a possibility that Sig-1R affects stimulant properties of ethanol such as locomotor activity rather than depressant properties. It has been shown that ethanol induces conditioned taste aversion (CTA) in rodents observed as reduced intake of a pleasant taste food when paired with ethanol injection (Green and Grahame 2008). Sig-1R KO mice developed a greater ethanol-induced CTA compared to WT mice, suggesting that mice lacking Sig-1R are more sensitive to an aversive effect of ethanol. Previous findings with Sig-1R ligands in the ethanol intake tests and CTA test apparently are opposed to the data from Sig-1R KO mice (Blasio et al. 2015; Maurice et al. 2003; Sabino et al. 2009b, c). Also, to our knowledge, there is no study that has investigated the relationship between Sig-1R and ethanol-related behaviors on female animals. These issues still remain to be investigated.

Sensorial System and Pain

Reports about Sig-1R’s involvement in the modulation of opioid analgesia traces to the first observations made by Pasternak and Chien where they studied antagonism of morphine analgesia by (+)-pentazocine (Chien and Pasternak 1993). Reports from Pasternak’s group prompted other investigators to broaden Sig-1R studies in different pain models. Rodent pain models offer a variety of approaches to test animal response for acute stimuli of mechanical or altered temperature to mimic chronic pain conditions. There are also diverse behavioral tests to evaluate different receptor systems and mechanisms that are involved in the sensory abnormalities associated with pain (Deuis et al. 2017).

The formalin test is one of the most widely used preclinical screening tests for spontaneous pain behavior. After administration of the chemical in the dorsal surface of the paw, 2 phases of responses are observed in rodents (Fischer et al. 2014). In Sig-1R KO female mice compared to WT, the response to formalin was markedly inhibited and duration of both phases was reduced in KO mice, leading to the conclusion that Sig-1R is necessary for the full expression of formalin-induced pain (Cendán et al. 2005). Capsaicin is an agonist of the transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily V, member 1 (TRPV1), which is expressed in small-diameter neurons of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) (Caterina et al. 1997) and has been used in inflammatory models of pain (Gregory et al. 2013). Capsaicin injection results in reflexive behavioral changes that include thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia surrounding the site of injury (the site itself becomes analgesic) and mechanical hyperalgesia outside the site of injury. Intradermal capsaicin administration induces secondary mechanical hypersensitivity through a central mechanism involving an activation of NMDA receptors. Capsaicin sensitized Sig-1R KO female mice (CD1) did not show hyperalgesia in response to mechanical punctate stimulus (Dynamic Plantar Aesthesiometer) (Entrena et al. 2009). Both CD1 and C57BL/6 J Sig-1R KO mice were resistant to capsaicin, while WT and Sig-KO capsaicin un-injected animals showed similar responses to different intensities of mechanical stimuli (Entrena et al. 2009).

Paclitaxel, a chemotherapeutic agent, produces peripheral neuropathy which causes acute neuropathy during or immediately after infusion (Boyette-Davis et al. 2013). Microtubule, mitochondrial dysfunction, axon degeneration, altered calcium homeostasis, and changes in peripheral nerve excitability have been linked to paclitaxel neuropathy (Zajączkowska et al. 2019). Treatment of paclitaxel in WT female mice caused cold (acetone test) and mechanical (Dynamic Plantar Aesthesiometer) allodynia, whereas the response in Sig-1R KO mice changed very little as compared to their baseline values. As presented in the motor-related behavior section of this review, comparison of WT and Sig-1R KO mice on Rotarod tests did not show differences, which suggested that no motor deficit could have accounted for the cold and mechanical allodynia in Sig-1R KO mice (Nieto et al. 2012).

In spinal cord contusion injury (SCI) Sig-1R KO female mice (CD1) showed reduction in mechanical allodynia (Von Frey) and thermal hyperalgesia (radiant heat) as compared to WT SCI mice (Castany et al. 2018). In peripheral nerve injury models of neuropathic pain, baseline values obtained from female and male WT and Sig-1R KO mice did not differ, suggesting that basic mechanisms for transduction, transmission, and perception of sensory and nociceptive inputs were intact in mice lacking Sig-1R. In the partial sciatic nerve ligation (PSNL) model of pain, mechanical (Von Frey) and thermal (cold) stimuli were attenuated or absent in Sig-1R KO animals. Conversely, the development of thermal hyperalgesia (plantar test) did not differ in the injured group when the different genotypes were compared (Puente et al. 2009). In the spared nerve injury (SNI) model of neuropathic pain, behavioral tests reported in other studies were repeated and confirmed. After SNI, Sig-1R KO mice developed less pronounced mechanical allodynia and did not develop cold allodynia (acetone test). Both KO and WT genotypes developed a similar degree of heat hypersensitivity in the Hargreaves test after SNI. It should be noted that during the pre-surgery baseline evaluation of acetone test ≈ 5% of the tested mice were discarded due to an exaggerated atypical response to the acetone (Bravo-Caparrós et al. 2019).

Other Dysfunctions

Peripheral Organs

Sig-1R is also expressed throughout peripheral organs as well as CNS (Alonso et al. 2000; Sigma Receptors 2007).

Heart

Sig-1R is widely expressed in the heart, which has even higher levels than in the brain (Bhuiyan et al. 2011; Dumont and Lemaire 1991; Novakova et al. 1995). The high expression of Sig-1R in the heart suggests that Sig-1R plays an important role in the modulation of cardiac function. Currently, most of Sig-1R’s contribution to cardiac function is based on pharmacological evidence from pathological cardiac models (Alam et al. 2017; Novakova et al. 2007; Novakova et al. 1995; Novakova et al. 1998; Shan et al. 2010). Sig-1R regulates cardiac function by modulating diverse ion channels, improving cardiac function, and demonstrating cardioprotection after ischemia and cardiac hypertrophy (Benedict et al. 1999; Bhuiyan and Fukunaga 2011; Huang et al. 2003; Johannessen et al. 2009; Shan et al. 2010; Tagashira et al. 2010; Tarabová et al. 2009). In cardiac tissue, modulation of contractility by Sig-1R ligands was first reported in rat neonatal cultured cardiomyocytes (Ela et al. 1994).

Recently, Abdullah and his colleagues employed a comprehensive analysis of how Sig-1R modulates cardiac hemodynamics in Sig-1R KO mice (Abdullah et al. 2018). Sig-1R does not affect baseline cardiac hemodynamic functions except higher systolic pressure seen in young KO mice (< 4 months old). With dobutamine, an adrenoceptor agonist and an inotropic agent (Ruffolo 1987), myocardial contractility is increased in KO mice. In aged mice (> 6 months old), KO mice demonstrate progressive systolic dysfunction, which is in line with the idea that Sig-1R agonist DHEA is decreased in aged heart failure patients (Moriyama et al. 2000) and Sig-1R ligand increases rat cardiomyocyte contractility (Novakova et al. 1998).

LiverLiver

Pal et al. did screening of metabolites related to oxidative stress using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) in livers of WT and Sig-1R KO mice (Pal et al. 2012). They noted an increase of oxidative glutathione and glutamate but also an increase of alanine, glutamine, lactic acid, AMP, myo-inositol and betaine, which are signs of oxidative stress but also of an increase of oxidative stress defense. They noted also by mass spectrometry an increase in Prdx6 and BiP, which are antioxidant proteins. In the same study, the authors measured the concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in liver, lung and primary culture of hepatocytes from Sig-1R KO and WT mice. They noted an increase in both organs of the ROS in Sig-1R KO mice compared to WT.

Bladder

Recently, González-Cano et al. noted that Sig-1R is present in human and mouse urinary bladder. Furthermore, they observed the impact of Sig-1R deletion in this organ (González-Cano et al. 2020). In this study, the authors noted that the deletion of Sig-1R has no consequences on various parameters observed such as Myeloperoxidase activity or ERK1/2 and pERK1/2 protein concentrations, which are known to be biomarkers of cystitis. However, they observed that pharmacological induction of cystitis is less severe in Sig-1R KO compared to what was observed in WT and that the deletion of Sig-1R avoids an increase of those previously described parameters in this pathological condition.

General Metabolism

In the Langa et al. study, growth curves of WT and Sig-1R KO newborn pups, from birth to weaning, were studied (Langa et al. 2003); however, no differences were noted. Other observations of body weight were done by Chevallier et al. and Yongu Ha et al. (Chevallier et al. 2011; Ha et al. 2012). In those studies, there were also no differences in the weights of adult and juvenile mice, neither female nor male. As previously mentioned, Chevallier et al. have observed the circulating estradiol (estradiol) levels. Sig-1R KO, 2 and 14-month-old female mice showed a significant decrease in 17b-estradiol basal level compared to WT mice (Chevallier et al. 2011). Yongu Ha et al. compared blood glucose and insulin levels in Sig-1R KO mice with levels present in WT mice. No significant differences between Sig-1R WT and KO mice were found (Ha et al. 2012). It should be noted also that Marcos and colleagues observed no differences between WT and Sig-1R KO in rectal temperature, micronucleated polychromatic erythrocyte or micronucleated reticulocytes (Guzmán et al. 2008).

This first part of the review, focused on behavior changes and alterations in various organ metabolism induced by the absence of Sig-1R, is summarized in Table 1. Despite no drastic changes in growth curves, adult weight, or breeding ability in the absence of Sig-1R, several behavioral alterations occur. Indeed, motor-, cognitive-, and psychiatric-related behaviors are altered. Furthermore, peripheral organs such as the heart or liver, are also affected. Interestingly it appears that aging increases deficits in many of those behaviors.

Table 1.

Behavior and metabolism changes induced with the deletion of Sig-1R

| Test | Measured parameter | Sig-1R KO mice compare to Wt | Mice | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Gender | |||||

| Behaviors | ||||||

| Cognition | Hamlet | Topographic memory | Decrease | 7 to 9 weeks old | Males | Crouzier et al. (2020) |

| Hamlet | Exploration pattern | Decrease | 7 to 9 weeks old | Males | Crouzier et al. (2020) | |

| Object recognition test | Recognition index after 1 h | No difference | 11 to 20 weeks old | Mix | Xu et al. (2017) | |

| Object recognition test | Recognition index after 1 h | Decrease | 11 to 20 weeks old | Mix | Xu et al. (2017) | |

| STPA | Step throught latency | No difference | 8 and 48 weels old | Males and females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| STPA | Escape latency | No difference | 8 and 48 weels old | Males | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| STPA | Escape latency | No difference | 8 weeks old | Females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| STPA | Escape latency | Increase | 48 weeks old | Females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Water-maze | Time to reach target during training | No difference | 8 weeks old | Males | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Water-maze | Time to reach target during training | Increase | 8 weeks old | Females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Water-maze | Time spent in Target quadrant during prob-test | No difference | 8 weeks old | Males | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Water-maze | Time spent in Target quadrant during prob-test | Decrease | 8 weeks old | Females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Water-maze | Time to reach target during training | Increase | 11 to 20 weeks old | Mix | Xu et al. (2017) | |

| Water-maze | Time spent in Target quadrant during prob-test | No difference | 11 to 20 weeks old | Mix | Xu et al. (2017) | |

| YMT | spontaneous alternation | No difference | 8 and 48 weeks old | Males | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| YMT | spontaneous alternation | Decrease | 8 and 48 weels old | Females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| YMT | spontaneous alternation | No difference | 11 to 20 weeks old | Mix | Xu et al. (2017) | |

| Motor activity | Beam walked | Time to cross | No difference | 12 weeks old | Males | Hong et al. (2017) |

| Beam walked | Time to cross | Increase | 24 to 48 weeks old | Males | Hong et al. (2017) | |

| Footprint analysis | stride pattern | No difference | 8 to 14 weeks old | n/a | Mavlyutov et al. (2010) | |

| Grid test | ability to lift the grid | Decrease | 20 weeks old | n/a | Bernard-Marissal et al. (2015) | |

| Grid test | ability to lift the grid | No difference | 12 to 36 weeks old | Males | Hong et al. (2017) | |

| Grid test | ability to lift the grid | Decrease | 48 weeks old | Males | Hong et al. (2017) | |

| Open field | Cumulative mobile time | No difference | 8–12 weeks old | Males | Langa et al. (2003) | |

| Open field | Distance traveled | No difference | 12 weeks old | Males and females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Open field | Locomotion speed | No difference | 12 weeks old | Males and females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Open field | Duration of immobility | No difference | 12 weeks old | Males and females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Open field | Distance traveled | No difference | 12 to 48 weeks old | Males | Hong et al. (2017) | |

| Open field | Spontaneous locomotion | No difference | Adult | n/a | Fontanilla et al. (2009) | |

| Open field | Beams interuption | No difference | 28 weeks old | Males | Sabino et al. (2009a, b, c) | |

| Rotarod | Score | Decrease | 10 and 20 weeks old | n/a | Bernard-marissal et al. (2015) | |

| Rotarod | Score | Decrease | 8 to 14 weeks old | n/a | Mavlyutov et al. (2010) | |

| Rotarod | Score | No difference | 12 weeks old | Males | Hong et al. (2017) | |

| Rotarod | Score | No difference | n/a | Females | Nieto et al. (2012) | |

| Rotarod | Score | Decrease | 24 to 48 weeks old | Males | Hong et al. (2017) | |

| Swimming test | Time to reach safe zone | Decrease | 8 to 14 weeks old | n/a | Mavlyutov et al. (2010) | |

| Water-maze | Swimming speed | No difference | 8 weeks old | Males and females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Water-maze | Swimming speed | No difference | 11 to 20 weeks old | Mix | Xu et al. (2017) | |

| YMT | Number of arms visited | Increase | 8 weeks old | Males and females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| YMT | Number of arms visited | No difference | 11 to 20 weeks old | Mix | Xu et al. (2017) | |

| Psychiatric related | Alcohol intake | Two-bottle choice continuous acces paradigm | Increase | 9–13 weeks old | Males | Valenza et al. (2016) |

| Elevated plus maze | Open arm time, closed arm entries | No difference | 28 weeks old | Males | Sabino et al. (2009a, b, c) | |

| Elevated plus maze | Open arm time | Decrease | 8 weeks old | Males | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Elevated plus maze | Open arm time | No difference | 8 weeks old | Females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Forced swimming test | Immobility duration | Increase | 20 weeks old | Males | Di et al. (2017) | |

| Forced swimming test | Immobility duration | Increase | n/a | Males | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Forced swimming test | Immobility duration | No difference | n/a | Females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Forced swimming test | Immobility duration | Increase | 28 weeks old | Males | Sabino et al. (2009a, b, c) | |

| Forced swimming test | Climbing | No difference | 28 weeks old | Males | Sabino et al. (2009a, b, c) | |

| Forced swimming test | Immobility duration | Increase | 8 weeks old | Males | Sha et al. (2015) | |

| Forced swimming test | Immobility duration | No difference | 8 weeks old | Females | Sha et al. (2015) | |

| Light–Dark transfert | Latency to enter light, time spend in light, transfert number | No difference | 28 weeks old | Males | Sabino et al. (2009a, b, c) | |

| Open field | Time spend in the center | Decrease | 8 weeks old | Males | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Open field | Time spend in the center | No difference | 8 weeks old | Females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| STPA | Latency to enter dark | Decrease | 8 and 48 weeks old | Males | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| STPA | Latency to enter dark | No difference | 8 and 48 weeks old | Females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Tail suspension | Immobility duration | Increase | 20 weeks old | Males | Di et al. (2017) | |

| Tail suspension | Immobility duration | Increase | 8 weeks old | Males | Sha et al. (2015) | |

| Tail suspension | Immobility duration | No difference | 8 weeks old | Females | Sha et al. (2015) | |

| Water intake | Two-bottle choice continuous acces paradigm | No difference | 9–13 weeks old | Males | Valenza et al. (2016) | |

| Somato sensation | Formalin test | Duration of licking/biting of injected paw | Decrease | 7–9 weeks old | female | Cendán et al. (2005) |

| Acetone Test | Duration of biting or licking of the hind paw | No difference | 8–11 weeks | female | Bravo-Caparrós et al. (2019) | |

| Acetone Test | Duration of biting or licking of the hind paw | No difference | 8–11 weeks | Males | Bravo-Caparrós et al. (2019) | |

| Capsaicin test. Dynamic Plantar Aesthesiometer (mechanical hypersensitivity) | Paw withdrawal latency time at 0.5 g (4.90 mN) force. | Increase | n/a | Female | Entrena et al. (2009) | |

| Dynamic Plantar Aesthesiometer (mechanical sensitivity) | Paw withdrawal latency time | No difference | n/a | Female | Entrena et al. (2009) | |

| Hot plate test at 50 ± 0.5 °C | Latency to the beginning of forepaw licking and jumping | No difference | 6–8 weeks old | Males | De la Puente et al. (2009) | |

| hot/cold plate (5 ± 0.5 °C) | The number of elevations of each hindpaw | No difference | 6–8 weeks old | Males | De la Puente et al. (2009) | |

| Paw pressure | The struggle response latency at 450 g constant pressure | No difference | n/a | Female | Sánchez-Fernández et al. (2014) | |

| Paw pressure | The struggle response latency at 450 g constant pressure | No difference | n/a | Female | Montilla-García et al. (2018) | |

| Plantar test | Hindpaw withdrawal latency in response to radiant heat | No difference | 6–8 weeks old | Males | De la Puente et al. (2009) | |

| Tail flick | Latency to tail-flick response | No difference | 6–8 weeks old | Males | De la Puente et al. (2009) | |

| Thermal stimulus (radiant heat) Hargreaves method | Hind paw withdrawal latency | No difference | 4–5 weeks old | Female | Castany et al. (2018) | |

| Thermal stimulus (radiant heat) Hargreaves method | Hind paw withdrawal latency | No difference | 8–11 weeks | Female | Bravo-Caparrós et al. (2019) | |

| Thermal stimulus (radiant heat) Hargreaves method | Hind paw withdrawal latency | No difference | 8–11 weeks | Males | Bravo-Caparrós et al. (2019) | |

| Unilateral hot plate | Paw withdrawal latency at 55 ± 1 °C | No difference | n/a | Female | Montilla-García et al. (2018) | |

| Von frey filament (up and down 0.008 to 2 g) | Hindpaw withdrawal response | No difference | 6–8 weeks old | Males | De la Puente et al. (2009) | |

| Von frey filament (up and down 0.02 to 1.4 g) | Paw withdrawal thresholds | No difference | 8–11 weeks | Female | Bravo-Caparrós et al. (2019) | |

| Von Frey filament (up and down 0.02 to 1.4 g) | Paw withdrawal thresholds | No difference | 8–11 weeks | males | Bravo-Caparrós et al. (2019) | |

| Von Frey filament (up and down 0.04–2 g) | Paw withdrawal thresholds | No difference | 4–5 weeks old | female | Castany et al. (2018) | |

| Peripheral organs | ||||||

| Cardiovascular system | Echocardiography | Left ventricul systolic internal dimension | No difference | 12 to 24 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) |

| Echocardiography | Left ventricul systolic internal dimension | Increase | 60 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) | |

| Echocardiography | Percentage fractional shortening | No difference | 12 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) | |

| Echocardiography | Percentage fractional shortening | Increase | 24 to 60 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) | |

| Echocardiography | Left ventricul systolic volume | No difference | 12 to 24 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) | |

| Echocardiography | Left ventricul systolic volume | Increase | 60 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) | |

| Echocardiography | Pourcentage ejection fraction | No difference | 12 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) | |

| Echocardiography | Pourcentage ejection fraction | Increase | 24 to 60 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) | |

| Echocardiography | Pourcentage ejection fraction | No difference | 24 to 60 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) | |

| Invasive Hemodynamic Assessement | Systolic blood pressure | Increase | 12 to 16 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) | |

| Invasive Hemodynamic Assessement | Heart rate, left ventricule contractibility | No difference | 12 to 16 weeks old | Mix | Abdullah et al. (2018) | |

| Liver | 2D gel electropherisis and mass spectroscopy | BiP, 40S Ribosomal Protein SA,b-Globinm, CPS1, Prdx6 | Increase | 12 weeks old | n/a | Pal et al. (2012) |

| 2D gel electropherisis and mass spectroscopy | HSP5, Mups | Decrease | 12 weeks old | n/a | Pal et al. (2012) | |

| DCFH-DA assay | ROS | Increase | 12 weeks old | n/a | Pal et al. (2012) | |

| Nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomic screening | Ala, AMP, Glu, Lactic Acid, Myo-Inositol, GSSG, Thr, Betaine, Gln | Increase | 12 weeks old | n/a | Pal et al. (2012) | |

| Nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomic screening | Val | Decrease | 12 weeks old | n/a | Pal et al. (2012) | |

| Lung | DCFH-DA assay | ROS | Increase | 12 weeks old | n/a | Pal et al. (2012) |

| Bladder | Western blot | ERK1/2, pERK1/2 | No difference | n/a | Females | González-Cano et al. (2020) |

| Myeloperoxidase activity | – | No difference | n/a | Females | González-Cano et al. (2020) | |

| General metabolism | Measured parameter | Sig-1R KO mice compare to Wt | Mice | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Gender | ||||

| Weight | Weight | No difference | 1 to 25 days postpartum | n/a | Langa et al. (2003) |

| Weight | No difference | 8 weeks old | Males and females | Chevallier et al. (2011) | |

| Weight | No difference | 3 and 15 weeks old | n/a | Ha et al. (2012) | |

| Blood composition | Estradiol | Decrease | 8 weeks old | Female | Chevallier et al. (2011) |

| Glucose | No difference | 3 and 15 weeks old | n/a | Ha et al. (2012) | |

| Insuline | No difference | 3 and 15 weeks old | n/a | Ha et al. (2012) | |

| Temperature | Rectal temperature | No difference | 14 weeks old | Males | Guzmán et al. (2008) |

The table presents the test and the measured parameter. The effect induced by the deletion of Sig-1R (increase, decreased or no difference). The age and the sex are also presented when available in the original article if not n/a (not applicable) is mentioned

Ala alamine, BiP binding immunoglobulin protein, CPS1 carbamoyl phosphate synthetase I, ERK1/2 extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2, Gln glutamine, Glu glutamic acid, GSSG oxidized glutathione, HSP5 heat shock protein 5, Mups major urinary proteins, pERK1/2 phosphorylated ERK1/2, Prdx6 peroxiredoxin-6, ROS reactive oxygen species, STPA step-through passive avoidance, Thr threonine, Val valine, YMT Y-maze test

Effect of the Absence of Sig-1R at Cellular Level

Neurons

Hippocampus

As described earlier in this review, lack of Sig-1R protein displayed memory deficits. The most well-studied part of the brain that is responsible for memory is the hippocampus. Immunohistochemical staining and Western blot analysis of the hippocampus revealed that there were no differences between hippocampus of WT and KO mice on the thickness of layers and the morphology of the neurons in CA (Cornu Ammonis) 1, CA3, and DG (dentate gyrus) (Chevallier et al. 2011), the expression level of neuronal marker NeuN, and the morphology of nuclei of hippocampal neurons (Xu et al. 2017). Since hippocampus is known as one of the brain regions at which adult neurogenesis occurs, the rate of the neurogenesis as well as the survival of the newborn neurons were compared between hippocampus of WT and KO mice. Sha et al. (2013) using, respectively, Ki67 and DCX as markers on hippocampus slices from 8-week-old male, found that newborn cell proliferation was significantly promoted in DG of KO mice compared to DG of WT mice, but that the number of survival newborn neuron was significantly lower in KO. They later found that the reduction of the survival of newborn cells was observed in only male KO but not female KO mice and the alteration was rescued by estradiol administration to male KO mice (Sha et al. 2015). Moreover, even though the length of the neurite of the surviving neurons was not altered, density of the neurite was significantly reduced. Slightly different results were recently found by Crouzier et al. as they found a decrease in both Ki67 and DCX positive cells in hippocampus slices from Sig-1R KO male mice aged between 9 and 11 weeks compared to WT mice (Crouzier et al. 2020). Sha et al. noted that all of these alterations except the neurite density were diminished by treatment of NMDAr agonist (Sha et al. 2015; Sha et al. 2013). Also, treatment with NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801 to WT mice induced upregulation of proliferation of cells but reduced the survival rate of the newly generated cells as observed in KO mice (Sha et al. 2013). This implies the possibility of NMDAr alteration due to lack of Sig-1R, which in turn affects the hippocampus function. Likewise, knocking down Sig-1R with siRNA transfection to hippocampal primary neurons leads to a significantly reduced number of branching and dendrites, which resulted in significantly decreased number of functional synapse formation via altered Rac-GTP pathway (Tsai et al. 2009). Although Tsai et al. reported contradictory results that Sig-1R siRNA transfected neuron showed decreased axon length (Tsai et al. 2015), it may be due to the difference between the acute knockdown and persistent knockout of the Sig-1R. Also, Sha et al. focused on adult neurogenesis (Sha et al. 2015; Sha et al. 2013), whereas Tsai et al. induced knockdown of Sig-1R by siRNA transfection in neuronal primary culture, which may reflect the phenomenon without compensatory mechanism for the loss of Sig-1R.

Just as Sig-1R KO male and female mice showed different results in memory behavior tests (Chevallier et al. 2011), there were sex-dependent differences in neurogenesis at hippocampus of KO mice as well. Sha et al. (Sha et al. 2015) observed the deficits in hippocampus of only male but not female KO mice; they noted a reduction of survival of newborn cells, reduction in NMDA-activated current (INMDA), and reduction in phosphorylation level of NR2B at hippocampus, and significantly promoted immobility in tail suspension test (TST) and forced swim test (FST) compared to WT mice. These phenomena were restored by estradiol administration in males and these defects were induced by OVX in female mice. This is in accordance with their finding that estradiol treatment reverted the depressive-like behavior of male KO mice and only KO OVX female mice displayed depressive-like behavior (Sha et al. 2015). These results further confirm the hormonal-dependent deficits in hippocampus that were also shown in the spatial memory behavior test (Chevallier et al. 2011). Taken together, these lead to the speculation that lacking Sig-1R results in defects in neurogenesis and that may contribute to the depressive-like behavior described above in KO mice (Sabino et al. 2009a).

As mentioned, NMDAr activity through NR2B phosphorylation has been a candidate molecular mechanism responsible for the deficits in hippocampus due to loss of Sig-1R. Indeed, altitude of INMDA was significantly smaller in KO condition than that of WT condition where GABA-activated current (IGABA) was unaltered (Sha et al. 2015; Sha et al. 2013). That altered INMDA may be caused by reduction of NR2B phosphorylation levels through the loss of Sig-1R protein. In addition, estradiol administration restored the survival of newborn neurons in male KO mice through promoting Src activity, which in turn upregulate the phosphorylation level of NR2B (Sha et al. 2015). On the contrary, Snyder et al. reported that although there was a small but significant reduction in the LTP magnitude, there were no differences between WT and KO of pyramidal neuron at CA1 (i.e., resting membrane potential and quality of (AP)) (Snyder et al. 2016). They also did not observe differences in the activity of AMPA receptor as well as NMDAr, and AMPA/NMDA ratio in CA1 area. This contradictory result may owe to the difference in the area where they measured the activity; DG vs CA1 area.

Other reports demonstrate that the Sig-1R absence in mice does not change the concentration of iNOS (Chao et al. 2017). While multiple reports indicate that knocking down (KD) Sig-1R in hippocampal primary neurons results in the decrease in mushroom spine density (Fisher et al. 2016; Ryskamp et al. 2019; Tsai et al. 2009), Tsai et al. also suggested that it was due to the increase of free radicals in Sig-1R KD neurons. Indeed, they observed that reducing the free radicals with the scavenger restores the dendritic spine formation in Sig-1R KD neurons. Later, the microarray data further confirmed that Sig-1R is involved in synapse formation and oxidative stress (Tsai et al. 2012). These results showed that Sig-1R seems to be able to reduce the oxidative stress and that loss of Sig-1R could result in the alteration of the hippocampus in case of oxidative stress.

Basal Ganglia and Motoneurons

Basal ganglia are a group of subcortical nuclei which are mainly involved in the regulation of motor activity. This group is composed of the striatum, substantia nigra, globus pallidus, ventral pallidum, and subthalamic nucleus. It was observed that defects could occur in Sig-1R KO mice in some of these structures. Hong et al. observed a progressive neurodegeneration of the substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons in Sig-1R KO mice compared to WT mice. Nevertheless, this phenomenon is not observed in 3-month-old mice but is found in mice 6-month-old or more. This result is correlated with an increase of αSyn monomers and oligomers phosphorylation and an increase of αSyn oligomers and fibril form, which are known to be neurotoxic. However, no alteration of the αSyn monomer population is observed. In the same time, it is noted that UPR activity is decreased, while oxidative stress is increased. Finally, Hong et al. observed that decreasing ER stress with salubrinal reversed those pathological phenotypes observed in Sig-1R KO mice (Hong et al. 2017).

It is known that Sig-1R is overexpressed in the striatum in neuropathology involving striatum (Ryskamp et al. 2017), which could be a response to the stress encountered by neurons induced in those pathological conditions. However, to our knowledge and despite the important results observed with motor coordination assays, no studies focused on the striatum condition in Sig-1R KO mice. Issues on the substantia nigra observed in Sig-1R KO mice, described before, which project to the striatum could lead by itself to a defective striatum. Results are contrasted in the expression of Sig-1R in the striatum. First, Alonso et al. noted from immunohistology studies “only faint if any” immunostaining of Sig-1R in the striatum (Alonso et al. 2000) but later, several studies reported through immunohistology and Western blot experiments the presence of Sig-1R in the striatum (Francardo et al. 2014; Hayashi et al. 2010; Navarro et al. 2013; Ryskamp et al. 2017). Importantly, Ryskamp et al. observed that Sig-1R deletion through the use of Crispr-Cas9 decreased the dendritic spines concentration on mice medium-spiny neurons.

Impact on motoneurons of the Sig-1R absence was especially studied in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) context, a neurodegenerative disorder affecting spinal cord motoneurons. It was observed that deletion of Sig-1R in a mouse model of ALS exacerbated disease pathological phenotypes (Mavlyutov et al. 2013). Furthermore, Ionescu et al., observing the contraction of myotubules in co-cultures with motoneurons, noted that motoneurons from Sig-1R KO mice induced less contractions of myotubules than motoneurons from WT mice (Ionescu et al. 2019). This result is correlated with BDNF retrograde transport decrease in motoneurons from Sig-1R KO mice compared to their WT counterparts (Ionescu et al. 2019). Moreover Mavlyutov et al. also observed that for the same stimulation, motoneurons from Sig-1R KO mice generated less action potential than motoneurons from WT mice (Mavlyutov et al. 2013). In addition, Marrissal et al. showed that the absence of Sig-1R- induced shorter motoneuron axons and increased cell death. Those results were correlated with defects on calcium signaling, ER and mitochondria metabolism (Bernard-Marissal et al. 2015). Those experiments may show that the in fine consequences of Sig-1R absence is a partial motoneuron degeneration.

Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal (HPA) Axis

The HPA axis is a major neuroendocrine system composed of three organs—the hypothalamus, anterior pituitary, and adrenal gland—and their functional interactions. The activity of the HPA axis dynamically changes depending on circadian and ultradian rhythms and stress, which controls a variety of body functions. The HPA axis plays a central role in neuroendocrine adaptation to stress response. Dysregulation of HPA axis activity is strongly correlated with several diseases including psychiatric disorders such as depression (Gjerstad et al. 2018; Spencer and Deak 2017). The HPA axis has three cellular components; 1—Neurons located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) receive neural input caused by stress and secrete corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). 2—Upon CRF activation, endocrine cells in the anterior pituitary rapidly release the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) that activates 3—secretion of glucocorticoid hormones (cortisol and corticosterone, CORT) from endocrine cells located primarily in the zona fasciculata layer of the adrenal cortex.

Di et al. studied the influence of Sig-1R deficiency in the HPA axis activity under basal condition or acute mild restraint stress (AMRS) using male WT and Sig-1R KO mice (Di et al. 2017). They found that there was no significant difference in the levels of serum hormones CORT, ACTH, and CRF, and mRNA of CRF in basal conditions between WT and Sig-1R KO mice. After exposure to 15 min of AMRS, serum levels of CORT and ACTH, as well as CRF mRNA were significantly higher in Sig-1R KO mice. These results suggest that the deficiency of Sig-1R causes hyperactivation of the HPA axis as a response to AMRS, indicating abnormal regulation of HPA axis activity.

CORT exhibits its effects through activating the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and mineralocorticoid receptor. While the GR is ubiquitously expressed throughout the body, it is expressed particularly high in the PVN of the brain as well as a few other regions. The GR in the PVN plays an important role for CORT to inhibit the HPA axis activity with a negative feedback loop and reduce its own production through the GR, which is thought to be the fundamental mechanism to terminate a stress response (Gjerstad et al. 2018). Di et al. showed that the protein expression and mRNA of GR in PVN did not differ between WT and Sig-1R mice either under basal conditions or AMRS treatment. They also examined the phosphorylation of GR since it is considered an activator of GR (Kotitschke et al. 2009). The phosphorylated GR (phospho-GR) level was significantly lower in Sig-1R KO mice compared to WT mice in basal conditions and this difference was maintained after AMRS exposure. Taken together, the Sig-1R deficiency continuously represses GR activation in PVN, which could lead to malfunction of the CORT-mediated negative feedback and hyperactivation of the HPA axis.

They further investigated if protein kinase C (PKC) and protein kinase A (PKA)/cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) are involved in the molecular mechanisms on how the Sig-1R deficiency causes suppressed phospho-GR levels. The basal level of phosphorylated PKC, an active form of PKC, in the PVN was lower in Sig-1R KO mice than that in WT mice similar to the phospho-GR. This is consistent with the fact that injection of PMA, a PKC activator, increased the phospho-GR in Sig-1R KO mice. On the other hand, the basal levels of phosphorylated PKA and CREB were not different in the PVN between WT and Sig-1R KO mice and a PKA inhibitor H89 treatment failed to alter the phospho-GR level. AMRS- induced phosphorylation of PKA and CREB both in WT and Sig-1R KO mice, whereas AMRS-induced phosphorylation of PKC and GR was observed in WT, but not in Sig-1R KO mice. Furthermore, PMA treatment rescued the decrease of phospho-GR and H89 treatment failed to manipulate the AMRS-induced increase of phospho-GR in WT mice. These results suggest that the decreased phospho-PKC likely contributes to the suppression of phospho-GR in Sig-1R KO mice, which is supported by the fact that PMA injection reduced the AMRS-induced increase of CRF mRNA and serum levels of CORT and ACTH.

Molecular Mechanisms of Sig-1R Action in Somatosensory System

Sig-1R is expressed in supraspinal, spinal, and peripheral nervous location of somatosensory pathway. Notably, Sig-1R bands at their highest intensities were found at DRG (Sánchez-Fernández et al. 2014).

DRG houses somata of primary sensory neurons. Primary sensory neurons are pseudounipolar by nature. Its distal process projects to cutaneous or deep peripheral tissues, and the proximal process terminates in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord or sensory nuclei of the brain stem. In naïve mouse DRGs, confocal microscopy localized the Sig-1R to the cell bodies of neurons. Sig-1R expression was enriched or restricted to the soma of DRG neurons, but not in their peripheral sensory endings or in the afferent axons, tested by colocalization studies of intrathecally injected adeno-associated virus (AAV) expressing the diffusible eGFP and fluorescently conjugated receptor-binding domain of the tetanus toxin for neuronal process labeling. In DRG neurons, S1R was detected in the plasma membrane, ER and nuclear envelope (Mavlyutov et al. 2016).

Based on the degree of myelination and associated conductance velocity, there are four main class types of sensory neurons: Aα, Aβ, Aδ, and unmyelinated C fibers. C fibers can be subdivided into peptidergic (express neuropeptides) and non-peptidergic neurons, which can be labeled with Isolectin B4 (IB4) (Silverman and Kruger 1990). Based on immunohistochemistry studies of Sig-1R expression pattern in DRGs, although Sig-1R were located in all DRG neurons, the distribution of these receptors was much higher in IB4 positive neurons (Montilla-García et al. 2018).

After spared nerve injury (SNI) in DRGs, Sig-1R is translocated to the plasma membrane and to the vicinity of the cell nucleus. In Sig-1R KO mice, the levels of CCL2, macrophage/monocyte infiltration, and IL-6 into the DRG were lower after nerve injury than in WT mice. In this particular experimental setting, after SNI, Sig-1R staining in DRG was restricted to sensory neurons, thus the authors proposed that the modulation of macrophage/monocyte infiltration in the DRG after nerve injury was unlikely to be caused by direct effect of Sig-1R on immune cells. They explained their results as Sig-1R playing a crucial communication role between neurons and macrophages/monocytes (Bravo-Caparrós et al. 2020).

The ultrastructural characteristics of myelinated and unmyelinated saphenous nerve fibers in WT and Sig-1R KO mice were similar. There was no difference in morphometric measurements or distribution pattern of the mitochondrial area in naïve animals. Paclitaxel treatment caused swelling and vacuolization of mitochondria in myelinated A-fibers. This phenomenon was not observed in paclitaxel treated Sig-1R KO animals (Nieto et al. 2014).

Some molecular changes have been reported at spinal cord level after injuries. Interestingly, in a number of different pain models, the same target was identified. For example, in capsaicin, PSNL (peripheral) and in SCI (central) models of neuropathic pain in the spinal cord, increase of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2) was not seen in Sig-1R KO animals as compared to WT counterparts. There was no difference in ERK1/2 protein level in naïve animals as compared to KO animals (Castany et al. 2018; Nieto et al. 2012; Puente et al. 2009). In SCI, phosphorylation level of NMDA-NR2B as well as expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β were decreased in Sig-1R KO mice in the T8-T9 segments of the spinal cord. WT animals showed stronger wind-up responses than Sig-1R KO animals at stimulus intensities sufficient to activate C fibers, while responses to repetitive A-fiber intensity stimulation didn’t produce spike wind-up and were similar in spinal cords of 5-10 day old WT and Sig-1R KO mice (Puente et al. 2009).

If we try to put together all the molecular changes seen in chronic or acute pain models from WT versus KO animals as described above, the molecular alternations are diverse, and this makes it difficult to pinpoint more concrete molecular signaling pathways that could be altered by Sig-1R. If we look at the data from more global approaches of reasoning, there should be something shared in the pathological mechanisms of all these different pain models that could be modified by Sig-1R. The reason for the changes in WT animals that are not observed in KO mice could be due to pain developing differently in KO and WT mice. As a result, we are not able to observe end point changes that are seen in different pain models. It is critical to study pain development mechanisms in WT and KO animals in more detail.

Retinal Ganglion Cells

Several studies demonstrated that retinal ganglion cells are also affected in Sig-1R KO mice. Mavlyutov et al. observed that Sig-1R is highly expressed in those cells (Mavlyutov et al. 2011). Furthermore, they noted that without stress, Sig-1R KO and WT mice had the same density of cells in the retinal ganglion cell layer. However, 7 days after mice were treated by optic nerve crush, the authors observed that the number of cells remaining is higher in WT mice compared to Sig-1R KO mice, concluding that Sig-1R alleviates retinal degeneration when stress is induced. Furthermore Ha et al. confirms in their study that acute but also chronic stress has more drastic consequences in Sig-1R KO mice than WT mice (Ha et al. 2012). Nevertheless, Ha et al. also observed differences between Sig-1R KO and WT mice without directly inducing stress in the retina but qualified them as late onset. Indeed, this group observed first that at 6 months, Sig-1R KO mice present axonal degeneration in the optic nerve head. Then at 12 months, Sig-1R KO mice develop a loss of cells in the ganglion cell layer which is correlated with an abnormal electroretinogram despite no changes in cornea or lens morphology (Ha et al. 2011). Results were confirmed in another study observing electroretinogram altered in 12-month-old Sig-1R KO mice (Ha et al. 2012). Moreover Mysona et al. observed the impact of Sig-1R absence on BDNF in retina cells and noted that this deletion induced a decrease in mature BDNF but no change in pro BDNF (Mysona et al. 2018). Altogether those results showed that retina is highly dependent on Sig-1R to counteract stress which could occur inside the cell.

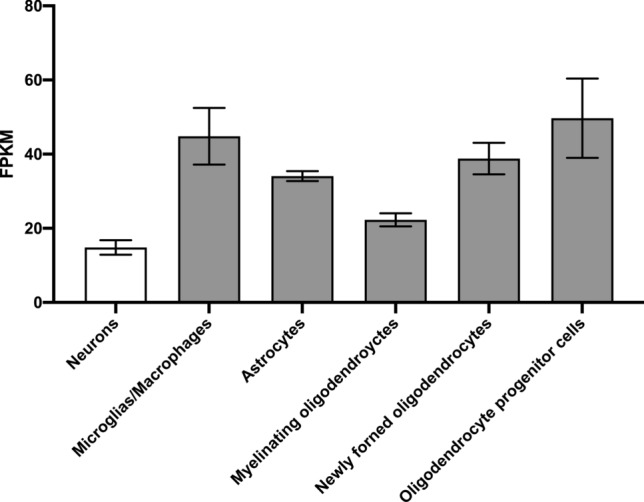

Non-neuronal Cells

Despite the fact that the consequences of Sig-1R activation, inhibition, or deletion are mainly studied in neuronal cells, it is important to note that Sig-1R plays an important role in other cell types. According to previous studies, Sig-1R is not only expressed in neuronal cells but is also expressed in glia cells such as astrocytes and microglias (Chao et al. 2017; Francardo et al. 2014; Peviani et al. 2014). Furthermore, the RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database analysis (Zhang et al. 2014) allows us to observe that Sig-1R is more expressed in glial cells than neurons (Fig. 1). However, Hong et al. observed the same amount of astrocyte and microglial cells, respectively, marked with GFAP and Iba-1 between WT and Sig-1R KO mice in substantia nigra (Hong et al. 2015). Nevertheless, Weng et al. noted an increase of astrocyte population in brain primary culture from Sig-1R KO mice compared to WT mice. Contradictory results about the impact of the Sig-1R deletion on glial cells are present in the literature; further experiments could shed light on this cell population. Despite different cardiovascular issues induced by the absence of Sig-1R, the size of cardiomyocytes and hypertrophy indicators measured as heart/body weight ratio do not vary between WT and KO mice, which may suggest that undesirable cardiac adaptations do not affect their mass.

Fig. 1.

Sig-1R expression profile in different brain cell types in mice. Sigmar1 mRNA level in different brain cell populations in mice. Glial cells have a higher expression of Sig-1R than neurons. FPKM: Fragments per kilo base of exon per million reads mapped. Result extracted from brainrnaseq database (Zhang et al. 2014)

Conclusion

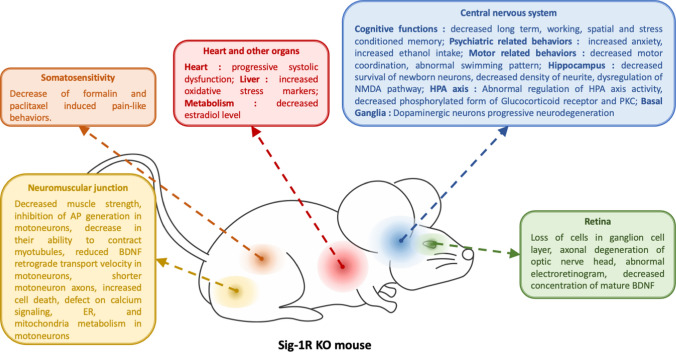

These different studies allow us to observe that the absence of Sig-1R induces various behavioral changes which are consequences of numerous cell type alterations. Those changes and alterations are summarized in Fig. 2. However, it seems that all those cell type alterations share a common origin: cell stress misregulation. Interestingly, we noted that aging in Sig-1R KO mice eventually induces enough cell stress to highlight the absence of Sig-1R that is not observable at a younger stage.

Fig. 2.

Schematic summary of defects induced by the absence of Sig-1R in mice. AP action potential, BDNF brain-derived neurotrophic factor, ER endoplasmic reticulum, HPA axis hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis

Several Phenotypes a Common Dysfunction? Poor Regulation of Cellular Stress

Activation and inactivation of Sig-1R with exogenous ligands are known to be key players in stress regulation, which is a keystone in pathological conditions and especially in the most common neurodegenerative disorders such as AD, PD, HD, ALS (Ryskamp et al. 2019; Tsai et al. 2014) or even cardiac disorders (Novakova et al. 2007). Studies on retinal cells observed that the absence of Sig-1R accelerates cell death following acute or chronic stress (Ha et al. 2012; Mavlyutov et al. 2011). However, it is less clear how important Sig-1R is in physiological conditions as its absence presents no fatal consequences in KO models (Langa et al. 2003). Interestingly, Hong et al. noted that the deletion of Sig-1R by itself induced ER stress, which lead to neurotoxicity and eventually pathological phenotypes. Even more noteworthy, they observed that neurotoxicity and these pathological phenotypes are alleviated using pharmacological ER stress inhibitors (Hong et al. 2017). Also, Pal et al. reported an increase of ROS and biomarkers of oxidative stress in liver of Sig-1R KO mice compared to WT mice (Pal et al. 2012). Those results allow us to think that the deletion of Sig-1R leads to neurotoxicity and pathological phenotypes through a dysregulation of cell stress regulation. However, it could be interesting to confirm that the use of ER stress inhibitors is equally able to protect all cell types altered by Sig-1R deletion. It should be noted that Sig-1R is known to have several other functions besides the regulation of oxidative stress (Su et al. 2016). However, studies that showed functions of Sig-1R are founded on the activation of Sig-1R through exogenous ligands (Su et al. 2016), mainly because of the lack of knowledge on endogenous ligands. Despite the interesting therapeutic findings brought by these studies, this does not prove that in physiological conditions, i.e., without application of exogenous molecules, such functions of Sig-1R are activated.

Aging and Sexual Dimorphism Highlight Sig-1R Deletion

Some experiments observing Sig-1R KO vs WT phenotypes demonstrate different results. However, when we look closer, we found that depending on the age and gender of the mice used, the absence of Sig-1R could have different consequences. Different studies observed that non-physiological phenotypes appear as the Sig-1R KO mice get older. Hong et al. (2017) demonstrated that 12-month-old Sig-1R KO mice have deficits in motor-related phenotypes compared to age-matched WT mice, without observing any differences in 3-month-old mice. Furthermore, Abdullah et al. observed that progressive cardiac disorders appear in Sig-1R KO mice as they age. This result is correlated with an increase of proton leak across the inner mitochondrial membrane in 6-month-old Sig-1R KO mice compared to WT mice, but this difference is not observable between 3-month-old mice (Abdullah et al. 2018). Cognitive dysfunction is also noted as age related in Chevallier et al. (Chevallier et al. 2011), as escape latency to STPA is not altered in 8-week-old females but is altered in 48-week-old females. Similar results are also noted in retinal ganglion cells, where it was observed that late onset neurodegeneration occurs in Sig-1R KO correlated with dysfunctional retinal activities (Ha et al. 2011; Ha et al. 2012; Mavlyutov et al. 2011). One exception is observed on anxiety tests where younger mice seem to have more defects (Chevallier et al. 2011) than older mice (Sabino et al. 2009a), but the difference between those results could be explained by the fact that they don’t come from one longitudinal study but rather come from two different experiments performed by two different groups. Sig-1R is known to regulate stress in cells, especially through regulation of Ca2+ into the mitochondria and activation of UPR. In physiological conditions, it is expected that cells are functional, and that cell stress occurs moderately compared to a pathological model. However, the more mice age, the more cells will encounter stress (Fonken et al. 2018; Haigis and Yankner 2010) and the more important Sig-1R becomes. Surprisingly, to our knowledge, no survival assay has been done to compare WT and Sig-1R KO mice lifespans. On light of those interpretations, it would be interesting to know more about the longevity in Sig-1R KO context. It is also interesting to note that in several models of neurodegenerative disorders such as ALS and AD where cell stress occurs, the deletion of Sig-1R aggravates those conditions (Maurice et al. 2018; Mavlyutov et al. 2013). However, others studies demonstrated that the deletion of Sig-1R induces the reduction of pathological phenotypes in pharmacological models of PD and AD (Hong et al. 2015; Yin et al. 2015).

As a receptor, Sig-1R is ligand activated. It is known that neurosteroids such as progesterone are a Sig-1R ligands. Furthermore, progesterone is known to have neuroprotective effects (Si et al. 2014). Circulating progesterone in WT male mice is around 1.96 ng/mL and in WT female in could vary between 3 and 15 ng/mL and even peaks between 25 and 50 ng/mL (Wagner 2006). This could lead to a sexual dimorphism in Sig-1R activity. This is confirmed by Chevallier et al. who observed different results between male and female Sig-1R KO and WT mice at the same age (Chevallier et al. 2011). Finally, it should be noted that two studies present results with Sig-1R KO heterozygous mice in physiological conditions (Chevallier et al. 2011; Yin et al. 2015). Yin et al. observed no deficit in heterozygous mice; however, Chevallier et al. observed that those heterozygous mice present some pathological phenotypes compared to WT mice, but fewer and milder than that observed in Sig-1R KO homozygous mice. All these results demonstrate that the more mice age, the more the absence of Sig-1R will lead to abnormal phenotypes. However, the impact of gender on the deletion of Sig-1R is still not clear.

Absence, Mutation, and Polymorphism of Sig-1R in Other Species

In humans, several mutations and polymorphisms of Sig-1R are known to be involved in pathological disorders. Sig-1R polymorphisms are known to aggravate pathological phenotypes or increase the risk of developing AD (Fehér et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2011) but also ALS (Ullah et al. 2015), whereas Sig-1R mutations are known to induce frontotemporal lobar degeneration and motor neuropathy (Gregianin et al. 2016; Li et al. 2015; Luty et al. 2010). Interestingly, Sig-1R E102Q amino acid substitution induces ALS and is known as a loss of function as the mutation is recessive (Al-Saif et al. 2011). However, in vivo studies observed that overexpression of this Sig-1R mutant in Drosophila melanogaster is able to induce ALS pathological phenotypes, underlining also a potential toxic gain of function (Couly et al. 2019). These results are correlated with previous in vitro observations (Dreser et al. 2017). It should be noted that despite no known homologues of Sig-1R are observed in Drosophila, fundamental interactors of Sig-1R in mammals such as BiP and IP3R have known homologues in Drosophila (Ham et al. 2014; Venkatesh and Hasan 1997). Furthermore, it seems that overexpressing Sig-1R in Drosophila is able to enhance resistance of Drosophila to oxidative stress (Couly et al. 2019). Moreover, in this review we previously noted that the deletion of Sig-1R seems to be necessary to optimal cell stress response; in Drosophila, we observed that expression of Sig-1R in a model which contains Sig-1R partners but not Sig-1R is able to enhance cell stress defenses at least against oxidative stress. These results are also correlated with studies that note that activation or overexpression of Sig-1R is able to enhance oxidative stress response (Goguadze et al. 2019; Pal et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2015). Combined, these results lead us to think that Sig-1R seems to be necessary to better regulate stress in cells as it is summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fundamental functions of Sig-1R on ER stress regulation. 1: Misfolded proteins increasing with age induce ER stress and modification in calcium homeostasis; 2: Calcium depletion in ER activates Sig-1R, which separates from BiP. Pathway a: IP3R and ATP production. 3a: Sig-1R interacts with IP3R and allows ankyrin to be detached from IP3R, which stabilize and enhance opening of IP3R. 4a: Calcium ions efflux from ER lumen into mitochondria through IP3R, VDAC, and MCU. 5a: Calcium ions increase in mitochondria enhances ATP production through TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation. Pathway b: Unfolded Protein Response. 3b: Sig-1R interacts with IRE1. 4b: Activated IRE1 acts as an endonuclease and is able to cut an intron from xbp1 to allow its translation. 5b: XBP1 allows the transcription of ER chaperone genes and pro-survival genes. ATP: adenosine triphosphate; BiP: binding immunoglobulin protein; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; ERAD: endoplasmic-reticulum-associated protein degradation; IP3R: inositol trisphosphate receptor; IRE1: inositol-requiring enzyme 1; MCU: mitochondrial calcium uniporter; OxPhos: oxidative phosphorylation; TCA: tricarboxylic acid cycle; VDAC: voltage-dependent anion channel; XBP1: X-box binding protein 1; xbp1s: xbp1 mRNA spliced; xbp1u: xbp1 mRNA unspliced

To conclude, altogether these results show that deletion of Sig-1R have numerous and various consequences at both behavioral and cellular levels. In the light of those observations and with the knowledge acquired from other studies observing the activation and inactivation of Sig-1R, we hypothesized a common origin of those defects induced by the absence of Sig-1R: the misregulation of cell stress occurring with aging.

Acknowledgements