Summary

When Thetis dipped her son Achilles into the River Styx to make him immortal, she held him by the heel, which was not submerged, and thus created a weak spot that proved deadly for Achilles. Millennia later, Achilles heel is part of today’s lexicon meaning an area of weakness or a vulnerable spot that causes failure. Also implied is that an Achilles heel is often missed, forgotten or under‐appreciated until it is under attack, and then failure is fatal. Paris killed Achilles with an arrow ‘guided by the Gods’. Understanding the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes (T1D) in order to direct therapy for prevention and treatment is a major goal of research into T1D. At the International Congress of the Immunology of Diabetes Society, 2018, five leading experts were asked to present the case for a particular cell/element that could represent ‘the Achilles heel of T1D’. These included neutrophils, B cells, CD8+ T cells, regulatory CD4+ T cells, and enteroviruses, all of which have been proposed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Did a single entity emerge as ‘the’ Achilles heel of T1D? The arguments are summarized here, to make this case.

Keywords: B cells, cytotoxic T cells, neutrophils, regulatory T cells, viral

Understanding the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes (T1D), in order to direct therapy for prevention and treatment is a major goal of research into T1D. At the International Congress of the Immunology of Diabetes Society, 2018, five leading experts were asked to present the case for a particular cell/element that could represent “the Achilles Heel of T1D”. These included neutrophils, B cells, CD8+ T cells, regulatory CD4+ T cells, and enteroviruses, all of which have been proposed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. Did a single entity emerge as “the” Achilles Heel of T1D?

Introduction

For nearly a century, insulin replacement therapy has been the only treatment option for individuals diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (T1D). A detailed understanding of disease pathogenesis would aid rational selection of therapies aimed at halting disease progress that destroys the insulin‐producing pancreatic β cells and even, in the future, prevent diabetes onset.

Since the 1970s, we have had evidence suggesting that T1D has a multi‐factorial pathogenesis, involving genetics and environmental influences that include viruses and immune responses. Sophisticated technology has facilitated imaging of the immune target, the pancreatic insulin‐producing β cell, as well as identification of numerous immune components that may be involved. However, we are still working to understand how T1D is initiated and how the disease process evolves in order to design therapies that may halt progression,

In this debate, five experts have discussed the case for elements of the disease pathogenesis to be the ‘Achilles heel’ of T1D. Each of these elements – cells of the innate immune system, B cells, CD8+ T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs) and enteroviruses – have been proposed to play an important role in the pathogenesis of T1D. Has a convincing case been made for any of these to be the ‘Achilles heel’?

Cells of the innate immune system (Manuela Battaglia)

For this debate, we have been tasked with convincing you that there is a specific cell type that is the Achilles heel of type 1 diabetes. I would posit that T1D is not a single disease, as multiple mechanisms are likely to lead to the same clinical manifestation [1]. Therefore, I start by asserting that I do not think that the Achilles heel exists in T1D. Here I will defend the hypothesis that some individuals have an abnormal innate interferon (IFN)‐related immune response which, in some circumstances, can lead to the development of T1D.

Type I IFNs are polypeptides secreted by infected cells and have three major functions: (i) they induce cell‐intrinsic anti‐microbial states in infected and cells in close proximity, which limit the spread of infectious agents, particularly viral pathogens; (ii) they modulate innate immune responses in a balanced manner that promotes antigen presentation and natural killer cell functions, while restraining proinflammatory pathways and cytokine production; and (iii) they activate the adaptive immune system, thus promoting the development of high‐affinity antigen‐specific T and B cell responses and immunological memory. Type I IFNs are protective in acute viral infections, but can also have deleterious effects in autoimmune diseases [2].

The clearest scientific evidence that type I IFNs contribute to T1D development comes from the evidence that individuals with hepatitis C undergoing type I IFN therapy have an increased risk of developing T1D by 10–18‐fold, compared to that of the corresponding general population. This complication typically appears abruptly, is manifested by severe hyperglycaemia accompanied by a high titre of anti‐islet antibodies and is often associated with autoimmune thyroid disease [3]. Of note, patients with other diseases, including multiple sclerosis and hairy cell leukaemia, receiving type I IFN therapy, have a higher risk of developing T1D [4].

Type I IFNs are a catastrophic feature of the islet microenvironment, as they are consistently found in the islet autoinflammatory milieu and represent a viable signal that may initiate/precipitate the development of T1D. Type I IFN cytokines can impair insulin secretory function, possibly through the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress, as well as by impairing mitochondrial bioenergetics. These cytokines also enhance the autoimmune surveillance of pancreatic β cells through induction of the immunoproteasome, de‐novo synthesis of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and genes responsible for the peptide loading complex, as well as enhanced surface expression of MHC class I. This increased capacity for antigen presentation results in the functional ability of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocyte‐mediated β cell destruction (neatly reviewed in [4]).

Our recent transcriptomic data generated on purified neutrophils from children at risk of developing T1D, as well as those with overt disease, demonstrate that neutrophil‐RNA expression is unique and distinct from that of age‐ and gender‐matched non‐diabetic individuals. Of note, this unique signature is already present in T1D family‐related donors but who are autoantibody‐negative, and it is superimposable on that of individuals with overt T1D. Such a signature is characterized by the high expression of IFN‐sensitive genes, suggesting the presence of an IFN‐rich environment in genetically predisposed individuals [5]. These data corroborate similar previous findings reporting an IFN‐rich signature in whole blood of relatives who had already been identified in autoantibody‐negative individuals [6, 7]. Overall, it is tempting to speculate that a specific genetic background predisposes individuals with a heightened innate immune reactive system who, when challenged perhaps repetitively or excessively, may respond erroneously, and this leads to uncontrolled innate immune reactivity.

Genetic predisposition is, therefore, the primary risk factor for the initiation of T1D autoimmunity and can be attributed to the complex interplay of more than 50 genetic loci that may impact immune function, pancreatic activity and regenerative capacity and many other key features. For example, IFIH1 encodes the protein MDA5, a cytoplasmic sensor of viral double‐stranded RNA and the non‐synonymous SNP found in IFIH1 results in a gene variant that may diminish ATPase activity of melanoma differentiation‐associated protein 5 (MDA5) activity, leading to deranged constitutive provocation of type I IFNs as well as blunted viral sensing (reviewed in [3]). Compelling evidence in primary human islets has revealed that presence of the homozygous risk allele decreases the innate response to Coxsackievirus B3 [8]. One could envisage that the IFIH1 risk variant might predispose β cells to persistent enteroviral infection while concurrently promoting deleterious type I IFN production in and around the islet microenvironment.

As only a small number of at‐risk individuals (who might carry the predisposing gene variant/s) will eventually develop T1D, it is likely that counter‐regulatory mechanisms are in place. For instance, Hayday and colleagues have demonstrated that the presence of neutralizing self‐reactive antibodies specific for type I IFNs is associated with protection against T1D in people with autoimmune regulator (AIRE) mutations and immunopositivity to GAD [9]. This further supports an important pathogenic role for IFNs in human T1D and an active mechanism of regulation in some individuals.

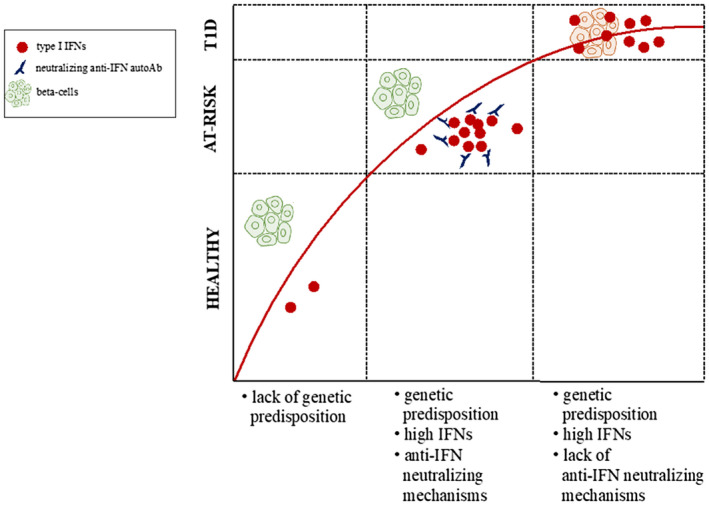

In summary, the Achilles heel in T1D is likely to be the combination of a genetic background that presents individuals with a heightened innate immune reactive response that, in some individuals, is kept in check by physiological regulatory mechanisms, while in others it remains uncontrolled. In the latter, an IFN‐rich environment is present, and this creates a highly toxic milieu for the β cells, with consequent development of T1D (Fig. 1). On the basis of the current evidence, additional studies are required to clarify further the role of type I IFNs in human T1D pathogenesis and determine whether they might represent an interesting therapeutic opportunity.

Fig. 1.

Intersection of genetic predisposition and immune responses involving type 1 interferons.

B cells (Jane Buckner)

For this debate, we have been tasked with convincing you that our assigned immune cell type, in my case the B cell, is the Achilles heel of T1D, but first we need to decide what makes an immune cell type an Achilles heel for T1D. I would posit that to be the Achilles heel, an immune cell needs to contribute to the following: (1) disease initiation; (2) disease progression; and (3) β cell damage. It also needs to be difficult to control and under‐appreciated. Here, I will present evidence that B cells meet all these criteria, and indeed are the immune cells that most warrant recognition as the Achilles heel of T1D.

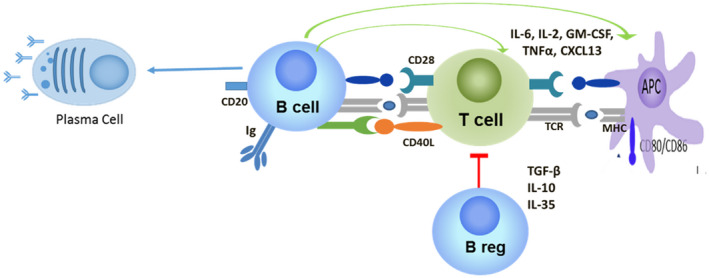

B cells have multiple immune functions, all of which may contribute to T1D pathogenesis. They produce antibodies, present antigens, produce inflammatory cytokines and have a regulatory function [10, 11] (Fig. 2). In T1D, B cells clearly have a key role in disease initiation based on both mouse and human studies. In the NOD mouse model, B cell ablation prevents development of diabetes [12, 13, 14], and this appears to be primarily due to their function as antigen‐presenting cells [15, 16]. Furthermore, studies of human cohorts at risk for developing T1D also implicate B cells in disease initiation, with the presence of two or more autoantibodies targeting islets as a hallmark of early‐stage T1D prior to clinical diagnosis [17]. There is also emerging evidence that B cell homeostasis and function is impaired in ‘at‐risk’ cohorts [11, 18, 19]. Reported alterations include increased frequency of transitional B cells, reduced frequency of anergic B cells and dynamic alterations in both B cell receptor and IL‐21 responses. Some of these alterations appear to be present only in presymptomatic T1D, whereas others persist after clinical diagnosis, suggesting a role in disease progression. Further evidence that B cells contribute to disease progression is provided by the rituximab clinical trial, which showed that B cell depletion with this anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody resulted in preservation of C‐peptide [20]. Although more research is needed, there are also data suggesting B cells contribute to β cell damage. Rapid loss of β cell function in individuals with new‐onset T1D is associated with a B cell signature, a finding most pronounced in the young [21]. B cells have been detected near or within pancreatic islets from individuals with recent‐onset T1D [22]. Interestingly, the abundance of B cells in the islets stratified with age at diagnosis, with CD20hi individuals diagnosed at a younger age than those individuals that were CD20lo, suggesting that B cells may be more important in childhood‐onset T1D. In addition, a recent study found a significant reduction in the number of primary B cell follicles in the pancreatic lymph nodes of individuals with recent‐onset T1D, compared to a non‐diabetic control group [23]. Mechanistic studies in mice also suggest that B cells contribute β cell damage by promoting CD8 T cell survival [24], as well as through production of inflammatory cytokines and their role as antigen‐presenting cells.

Fig. 2.

B cells influence islet autoimmunity at multiple levels.

B cells also pose unique therapeutic challenges. Despite anti‐B cell therapy, islet autoantibodies persist after B cell depletion [20] and B cells arising after depletion are still autoreactive [25]. In addition, responses to therapies that target B cells may only be seen in a subgroup of individuals with T1D. Those who were young and had a B cell immunotype were more likely to respond to B cell depletion [21], while individuals showing a poor response to abatacept, a T cell‐targeted therapy, had a transient increase in B cell activation after therapy [26]. Additionally, preservation of regulatory B cells may also enhance responses to B cell targeted therapies [27]. This suggests that therapeutic approaches targeting B cells will need to be both selective about which patients receive treatment and the B cell type that is targeted. Lastly, a review of the literature highlights how under‐appreciated B cells are in the field of T1D research. On 15 April 2020, a PubMed search for ‘B cell and type 1 diabetes’ resulted in only 1081 publications; in contrast, a search for ‘T cell and type 1 diabetes’ identified 5909 publications.

In summary, B cells are involved in disease initiation, disease progression and β cell damage, and are difficult to target therapeutically. Importantly, our understanding of B cells is still incomplete, with an under‐appreciated role in T1D pathogenesis until recently. Achilles knew he had a weak point – but left it unshielded; B cells have been telling us they are important – have we been ignoring them?

CD8+ T cells (F. Susan Wong)

In this debate, I propose that cytotoxic CD8+ T cells are the Achilles heel in type 1 diabetes. In T1D, there is infiltration of the pancreatic islets with immune cells and a loss of the production of insulin, implying β cell damage and destruction [28]. If a modern definition of Achilles heel is a vulnerable spot that is missed and under‐appreciated, the CD8+ T cells cause failure of β cells by attacking in a situation where their effector role causes immunopathology and β cell damage. This may occur at disease initiation and certainly progression in a setting where highly effective cytotoxic CD8+ T cells are either inappropriately activated or correctly functioning but inadequately regulated.

Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells are vital effectors in the adaptive immune system, are required for protection against viruses and tumours, and can respond to very low amounts of antigen. They kill target cells by a variety of means that include release of cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzymes, production of cytotoxic cytokines and induce apoptosis by CD95–CD95 ligand interactions. They can also become memory cells, which will rapidly kill target cells on reactivation. In recent years, it has become clear that CD8 T cells may be highly promiscuous, and are able to respond to a spectrum of antigens, possibly becoming activated by high‐avidity targets and then able to recognize autoantigenic targets with low affinity [29].

Are CD8+ T cells involved in disease initiation? It is difficult to know for certain about human type 1 diabetes. Certainly, for one of the most studied mouse models, the non‐obese diabetic (NOD) mouse, they are clearly involved in the early stages of disease. In the absence of MHC class I, required for antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells, few CD8+ T cells develop and neither insulitis nor diabetes occurs [30, 31]. In humans, CD8+ T cells are found infiltrating the pancreatic islets at the time of diagnosis of type 1 diabetes [32]. They are also found in postmortem samples of people who have died having had recently diagnosed T1D, and are the most abundant infiltrating immune cell [33, 34]. The CD8+ T cells within the pancreas can be shown to be specifically responsive to insulin and other islet autoantigens [35]. Together with this can be seen up‐regulation of MHC class I on the islets of Langerhans [36], and this is not observed in the islets that are not infiltrated, and also not found in non‐diabetic controls [37]. The very presence of these CD8+ T cells does not necessarily imply that they are initiators, but certainly they are the most abundant cells to be found within the islets in the studies focused upon pancreatic cell infiltration.

How would the CD8+ T cells become activated to initiate damage the β cells? For many years, there has been debate about whether molecular mimicry is a mechanism for activation of autoreactive T cells in diabetes, with a number of viral epitopes proposed to be potential initiators. Recently, gut bacterial peptides have been shown to be able to activate CD8+ T cells in NOD mice. This was exemplified by a peptide from fusobacteria found in the gut, able to stimulate islet‐specific glucose‐6‐phosphatase related protein (IGRP)‐reactive CD8 T cells [38]. Similarly, a human proinsulin‐specific clone can recognize a peptide of Clostridium aspargiforme [39]. Thus, there is the means to activate these pathogenic CD8+ T cells without invoking an infection. Furthermore, there is also the possibility of a viral infection in the pancreas, with some enteroviruses specifically able to target islet β cells [40] (see below). As CD8+ T cells are important effectors that are central to the immune response to viral infection, their collateral effects in dealing with a viral infection within the pancreas could be particularly important in both initiation and progression of islet cell damage.

So, are CD8+ T cells involved in damage to the islets? Undoubtedly, islet‐reactive T cells can kill islet β cells. The initial discovery that proinsulin was an important antigen for CD8+ T cells in the NOD mouse model showed very clearly that insulin‐reactive CD8+ T cells can not only kill islet β cells in vitro but also in vivo, leading directly to the onset of diabetes and clear histopathological evidence that the islets had been destroyed [41, 42]. These findings were followed by the cloning of a proinsulin‐specific CD8+ T cell clone from an individual who had type 1 diabetes, which was shown to have the capacity to kill islet cells in vitro [43]. Transplantation studies by Sutherland and colleagues have given very strong evidence that CD8+ T cells are able to damage and destroy islets in vivo in humans [44]. Pancreatic transplantation was carried out in identical twins discordant for T1D; when the non‐diabetic twin donated a portion of pancreas to the diabetic twin, unfortunately T1D recurred rapidly, and histology showed a predominance of CD8+ T cells. It is interesting that, more recently, it has been noted that alterations in frequency of a CD57+ subset of memory CD8 T cells correlates with changes in C‐peptide levels after diagnosis of T1D [45].

Finally, if CD8+ T cells are the Achilles heel, could they be targeted to prevent or treat type 1 diabetes? While there have not been any immunotherapies that have had a lasting effect on reducing β cell loss, as measured by decrease of C‐peptide, recently a number of strategies have slowed the initial rate of loss of β cell function. In a study where the anti‐CD2 monoclonal antibody Alefacept was given in two 12‐week courses over 36 weeks, the treated individuals exhibited a delay in C‐peptide loss [46, 47]. Interestingly, there was a reduction in the CD8+ central memory cells, correlating with this delay in C‐peptide decline. An alternative therapeutic manoeuvre involved administration of plasmid‐encoded proinsulin, and a short duration of C‐peptide preservation was associated with reduction in proinsulin‐specific CD8 T cells [48]. Although these are correlative observations, if CD8+ T cells could be directly targeted this might, in the future, be an important avenue to pursue.

In conclusion, we could consider that the major vulnerability in type 1 diabetes is the β cell itself, as the target organ that becomes damaged, and requires protection. CD8+ cytotoxic T cells will attack cells, which they specifically recognize and that display signals, such as increased MHC class I. Other processes that can lead to an increase in this vulnerability include β cell stress and viral infection, and these increase the visibility to the CD8+ T cells which, if unchecked, will damage the β cells. Thus, while a major strength in terms of the vitally important protection given by CD8+ T cells fighting off infectious agents and tumours, this strength could be considered the Achilles heel in type 1 diabetes where normal function of CD8+ T cells is deleterious, and should be targeted for control.

Regulatory T cells (Megan Levings)

According to Wikipedia, an Achilles heel is ‘a weakness in spite of overall strength, which can lead to downfall’. T1D is an immunologically complex disease mediated by a co‐ordinated network of innate and adaptive immune cells. I argue that at the top of this network of immune cells is the Treg: a cell type which possesses strong immunosuppressive function yet has several points of weakness which can lead to their functional demise. A key concept is that there are probably many origins of Treg weakness in T1D. Their loss of function could be the consequence of genetics, environment, intrinsic dysfunction and/or changes in the susceptibility of effector cells to suppression [49]. Although multiple roads can lead to the downfall of Tregs, the common outcome is the failure to keep the autoreactive immune response at bay, thus unleashing the destructive power of islet‐cell‐reactive effector T cells, which we all have in circulation [50].

When one gives a talk or writes a review about Tregs, it is common to use analogies such as ‘conductors’, ‘police of the immune system’, ‘peacekeepers’ or ‘firefighters’. These comparisons are meant to convey the message that this single‐cell type is at the top of a cellular hierarchy, with the power to orchestrate and control many aspects of immune function. It important to consider that although the best‐known effect of Tregs is control over other T cells through their broad, typically cell‐type agnostic, immunosuppressive mechanisms, they control many different types of immune responses. For example, beyond conventional T cells, they control B cells [51, 52], natural killer (NK) cells [53], γδT cells [54], antigen‐presenting cells [55] and even neutrophils [56]: essentially, all the other cell types that my learned co‐authors have argued for. As long as Tregs are functioning properly, these other immune cells do not have a chance. Moreover, a recent development is that Tregs not only exert control over immune cells, but also of islets themselves, with an emerging literature – albeit almost exclusively in mice so far – describing the important role of Tregs in promoting β cell survival and regeneration [57].

Perhaps the strongest evidence that Tregs are the Achilles heel in T1D comes from the study of IPEX: the X‐linked monogenic immunodeficiency arising from mutations in forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3), the key Treg lineage‐defining transcription factor [58]. Children affected by IPEX have a variety of conditions, but a unifying feature is T1D, which manifests in the majority of patients, often at birth. Imaging and autopsy studies in IPEX reveal destruction of the pancreas and intense lymphocytic infiltrates in many tissues, highlighting the strength of the autoreactive response in the absence of Tregs [59, 60]. Moreover, other rare monogenic mutations which affect Treg function, for example in CD25 or CTLA4, can also cause T1D, lending more support to the argument that, without these cells, islet‐directed immunity is unleashed [61].

However, beyond the rare monogenic causes of T1D, it is also important to consider the prevalence of genetic effects on Treg function in the common polygenic form of the disease. Classical genome‐wide association studies (OGWAS) repeatedly uncover genetic risk factors associated with a variety of Treg relevant genes [62, 63]. For example, genes with high odds ratios include CD25, PTPN2, PTPN22, CTLA4, and IL2 ‐ all genes which can affect Treg function [64, 65].

It has been challenging to pinpoint exactly how Tregs are dysfunctional in T1D. In addition to the fact that multiple roads can lead to dysfunction, seeking the answer to this question in humans has been difficult due to the limitations of studying peripheral blood, which may not capture relevant antigen‐specific cells, the lack of a standardized, reproducible and antigen‐specific suppression assay and that the commonly used in‐vitro suppression may not even measure function which is relevant in vivo. Because of the difficulty in accurately quantifying Tregs by flow cytometry, over the years there have been a myriad of reports of Tregs being higher or lower, and functional or dysfunctional in T1D [49]. There are also reports of Treg ‘instability’, manifested as increased proinflammatory cytokine production [66, 67]. A consistent finding is their relative unresponsiveness to IL‐2 [68, 69], and we have shown diminished production of chemokines that are important for attracting their targets of suppression [70]. We also studied Tregs using a gene signature‐based approach, initially defining a core Treg transcriptome, then applying this signature to unfractionated cells in blood. These data showed that Tregs from both children and adults with T1D have changes in their core transcriptional signature, and that monitoring this signature can be used to track changes in Tregs over time in the context of clinical trials [71, 72].

It is also noteworthy that both academia and industry are clearly convinced that Tregs represent an Achilles heel on the basis of the large number of clinical studies specifically aimed at targeting these cells. Examples of Treg‐targeted therapies include those that aim to directly manipulate the IL‐2/IL‐2R pathway, or to indirectly boost their numbers or activity, using approaches such as tolerogenic dendritic cells (DCs) or cytokine modulation to create an environment favourable for Treg function. It can be anticipated that the polyclonal Treg cell therapy studies which provided important safety data [73] will soon advance to testing of antigen‐specific Tregs [74]. Almost 20 years since the power of this approach was first demonstrated in NOD mice [75, 76], perhaps there will finally be a way to fix the Achilles heel of T1D.

The virus‐infected beta (β) cell (Sarah Richardson)

In the 1920s, Gunderson originally proposed that diabetes may be ‘of infectious origin?’ [77]. Since then, many studies have provided additional support for the role of viruses, particularly enteroviruses (EV), the focus of this review, in the development of islet autoimmunity and progression to T1D [78, 79, 80, 81]. As alluded to earlier, for a cell or a pathological agent to be the Achilles heel of T1D they need to contribute to the following: (1) disease initiation; (2) disease progression; and (3) β cell damage. However, in the case for EVs, I propose that we think of the β cell itself as the Achilles heel, and then the enterovirus as the arrow that targets it. I will also re‐order the contributions to: (1) β cell damage; followed by (2) disease initiation; and finally (3) disease progression, for reasons that will soon become clear.

β cell targeting and damage by enteroviruses

Evidence of β cell damage by select EV serotypes [Coxsackie B (CVB) and echoviruses] has been demonstrated both in vivo and in vitro (reviewed in [40]). The examination of pancreata from children who died following an acute CVB infection shows selective targeting of the islets [82, 83, 84, 85]. Furthermore, isolated human islets are highly susceptible to infection in vitro [41, 78, 86], particularly with EVs associated with the development of islet autoimmunity and T1D in epidemiological studies. These viruses have tropism for β cells above other pancreatic endocrine cells [86, 87, 88], and the recent finding that human β cells express a specific isoform of the Coxsackie and adenovirus receptor (CAR) could explain why they are selectively targeted [87]. This isoform was unexpectedly localized to the insulin granule membrane and therefore could, under situations where the host has viraemia (virus in the blood), facilitate infection of the β cells during the process of insulin secretion.

Importantly, a large proportion of genes associated with genetic susceptibility to T1D are expressed in β cells [86, 89, 90], and ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) of these demonstrates that the ‘top hit’ pathways involve cellular sensing of infections and responses to IFNs [91]. β cells are known to be highly responsive to IFNs [92], which are rapidly induced and distributed systemically in response to a viral infection. The ability of the host to rapidly produce an immune response against the virus, and the capacity of the β cells themselves to control the infection, will determine the extent and level of damage in a given individual. Crucially, several of the T1D associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with differential responses to both viral infection and IFN stimulation [8, 93]. It is not inconceivable, therefore, that Achilles, ‘the β cell’ carrying these risk SNPs would have altered susceptibility to infection and/or an aberrant immunological response following infection, which could impact upon both the degree of initial damage and his ability to resolve it.

Disease initiation

As with any viral infection, recruitment of innate immune cells to the affected site facilitates the presentation of the antigens released from damaged cells (in this case derived from the β cells) to the adaptive immune system. In the context of T1D, individuals at risk of developing disease have an increased propensity to recognize self‐derived antigens and have deficiencies in regulating responses against these self‐antigens (covered elsewhere in this review). The toxic combination of a viral infection, which causes β cell damage and specific presentation of β cell antigens to an immune system primed to recognize self‐antigen, without appropriate regulation, could promote disease initiation in these genetically susceptible individuals.

In support of this hypothesis, epidemiological studies have demonstrated an association between enteroviral infections and the appearance of islet autoantibodies (evidence of an adaptive host response against the β cell antigens). A meta‐analysis in 2011 found that individuals with islet autoimmunity were more than 3.7 times more likely to have evidence of an enterovirus infection [80]. It is also worth considering the evidence from studies in Cuba, where an enterovirus epidemic led to the development of islet autoantibodies in a significant number of individuals [94]. The circulating enterovirus isolated from affected individuals was shown to infect and impact upon β cell function in vitro [94, 95]. However, the majority of these individuals did not develop T1D. What this study demonstrates, therefore, is that enteroviruses can infect β cells; they can cause sufficient damage to induce an adaptive response directed against β cells, but this alone is not sufficient to initiate the development of T1D. Progression to T1D needs a breakdown in immune tolerance (in the case of Achilles, ‘friendly fire’) and potentially also a ‘smouldering fire’ (chronic infection) to facilitate the continued recruitment of immune cells to the islets.

Disease progression

The evidence for the role of enteroviruses in β cell damage and disease initiation is compelling, but could they also contribute to progression? There is circumstantial evidence that they can. Enteroviral infections have been associated with accelerated progression from islet autoantibody positivity to clinical onset of diabetes in many studies around the world (reviewed in [79, 81]). A meta‐analysis of these demonstrated that individuals at clinical onset of T1D are nearly 10 times more likely to exhibit evidence of an enteroviral infection compared to controls [80]. However, the emerging evidence at onset does not support the presence of an acute infection; rather, studies of the blood and pancreas from individuals with T1D suggest the presence of a low‐level, chronic infection (reviewed in [40, 79, 96]).

Why might this be important? Studies in the pancreas of individuals with T1D demonstrate that islets, which still contain residual β cells (even several years after diagnosis), have clear evidence of aberrant IFN and anti‐viral responses [37, 97, 98]; these findings correlate with evidence of low levels of infection, as assessed by the presence of viral protein and RNA [83, 97, 98, 99, 100]. One key hallmark feature in the pancreas of T1D donors is the dramatic hyperexpression of human leucocyte antigen (HLA) class I [37, 101], which can facilitate the recognition and targeting of β cells by infiltrating, potentially self‐reactive, CD8+ T cells. A low level, chronic smouldering infection within the pancreatic β cells could be sufficient to maintain an environment that facilitates the recruitment of self‐reactive immune cells over a protracted period, ultimately creating a progressively destructive process in the islets eventually leading to clinical diagnosis.

So, was Achilles’ heel (the β cell), first damaged by an infection that did not resolve which, when combined with the presence of islet‐reactive immune cells and a breakdown in immune tolerance, resulted in a festering wound that brought about his demise? The answer: perhaps. How do we know? Most of the studies described here report an association of infection with the clinical biomarkers accompanying the development of T1D; importantly, they do not demonstrate causality. The only way to definitively prove that enteroviruses contribute to the initiation and progression of the disease is to prevent the infection in the first place and assess the impact of this on disease development. Effectively, we want to give Achilles ‘a pair of boots’ to protect his heel, which is far easier said than done. Encouragingly, however, efforts are now under way [40, 78, 102] to generate an anti‐enteroviral vaccine, which targets multiple CVB serotypes with first‐in‐man trials scheduled in 2020/2021. The intention is to immunize young individuals who are genetically at risk of developing T1D and follow them to assess the impact on the development of islet autoantibodies and onset of clinical disease. Another approach, currently being trialled at the University of Oslo, involves the use of the anti‐viral drugs ribavirin and pleconaril, which are given to individuals at the onset of disease to promote clearance of chronic infection with the hope that this could help to preserve residual β cell mass. The field eagerly awaits the outcome of these efforts and Achilles ‘the β cell’ looks forward to his new boots!

Conclusion

We will leave the reader to judge whether, indeed, there is a single ‘Achilles heel’ in type 1 diabetes. At the conference, in the spirit of debate, voting was carried out and was won by Sarah Richardson, who deftly adjusted the proposition that the β cells, infected by enteroviruses, are the Achilles heel in type 1 diabetes. In providing the arguments in support of the individual component/cell/process that is the Achilles heel in T1D, all the debate participants agreed that this is not a single entity, with the β cell representing a weakness that is targeted for death and a number of other potential contributors to this process. The challenge remains as to how we use the evidence to progress the therapeutic targeting, with the aim of providing robust immunotherapeutic treatment for halting disease progression and future prevention.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

F. S. Wong, Email: wongfs@cardiff.ac.uk.

T. I. Tree, Email: timothy.tree@kcl.ac.uk.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Battaglia M, Ahmed S, Anderson MS et al. Introducing the endotype concept to address the challenge of disease heterogeneity in type 1 diabetes [internet] Diabetes Care 2020; 43:5–12. American Diabetes Association Inc.; [cited 2020 Oct 27]. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31753960/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat Rev Immunol [internet] 2014; 14:36–49. Available at: http://www.nature.com/articles/nri3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zornitzki T. Interferon therapy in hepatitis C leading to chronic type 1 diabetes. World J Gastroenterol [internet] 2015; 21:233. Available at: http://www.wjgnet.com/1007‐9327/full/v21/i1/233.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newby BN, Mathews CE. Type I interferon is a catastrophic feature of the diabetic islet microenvironment. Front Endocrinol [internet] 2017; 8. Available at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fendo.2017.00232/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vecchio F, Lo Buono N, Stabilini A et al. Abnormal neutrophil signature in the blood and pancreas of presymptomatic and symptomatic type 1 diabetes. JCI Insight [Internet] 2018; 3. Available at: https://insight.jci.org/articles/view/122146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferreira RC, Guo H, Coulson RMR et al. A type I interferon transcriptional signature precedes autoimmunity in children genetically at risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes [internet] 2014;63:2538–50. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2337/db13‐1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kallionpaa H, Elo LL, Laajala E et al. Innate immune activity is detected prior to seroconversion in children with HLA‐conferred type 1 diabetes susceptibility. Diabetes [internet] 2014. Jul 1; 63:2402–14. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2337/db13‐1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Domsgen E, Lind K, Kong L et al. An IFIH1 gene polymorphism associated with risk for autoimmunity regulates canonical antiviral defence pathways in Coxsackievirus infected human pancreatic islets. Sci Rep [internet] 2016; 6:39378. Available at: http://www.nature.com/articles/srep39378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meyer S, Woodward M, Hertel C et al. AIRE‐deficient patients harbor unique high‐affinity disease‐ameliorating autoantibodies. Cell [internet] 2016; 166:582–95. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0092867416307929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fillatreau S. B cells and their cytokine activities implications in human diseases. Clin Immunol [internet] 2018; 186:26–31. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1521661617305326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith MJ, Simmons KM, Cambier JC. B cells in type 1 diabetes mellitus and diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol [internet] 2017; 13:712–20. Available at: http://www.nature.com/articles/nrneph.2017.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Akashi T. Direct evidence for the contribution of B cells to the progression of insulitis and the development of diabetes in non‐obese diabetic mice. Int Immunol [internet] 1997; 9:1159–64. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/intimm/article‐lookup/doi/10.1093/intimm/9.8.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xiu Y, Wong CP, Bouaziz J‐D et al. B lymphocyte depletion by CD20 monoclonal antibody prevents diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice despite isotype‐specific differences in FcγR effector functions. J Immunol [internet] 2008; 18:2863–75. Available at: http://www.jimmunol.org/lookup/doi/10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hu C, Rodriguez‐Pinto D, Du W et al. Treatment with CD20‐specific antibody prevents and reverses autoimmune diabetes in mice. J Clin Invest [internet] 2007; 117:3857–67. Available at: http://content.the‐jci.org/articles/view/32405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noorchashm H, Lieu YK, Noorchashm N et al. I‐Ag7‐mediated antigen presentation by B lymphocytes is critical in overcoming a checkpoint in T cell tolerance to islet beta cells of nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol [internet] 1999; 163:743–50. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10395666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marino E, Tan B, Binge L, Mackay CR, Grey ST. B‐cell cross‐presentation of autologous antigen precipitates diabetes. Diabetes [internet] 2012; 61:2893–905. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2337/db12‐0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ziegler AG, Rewers M, Simell O et al. Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA [internet] 2013; 309:2473. Available at: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2013.6285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Habib T, Long SA, Samuels PL et al. Dynamic immune phenotypes of B and T helper cells mark distinct stages of T1D progression. Diabetes [internet] 2019; 68:1240–50. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2337/db18‐1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith MJ, Rihanek M, Wasserfall C et al. Loss of B‐cell anergy in type 1 diabetes is associated with high‐risk HLA and non‐HLA disease susceptibility alleles. Diabetes [internet] 2018; 67:697–703. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2337/db17‐0937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pescovitz MD, Greenbaum CJ, Krause‐Steinrauf H et al. Rituximab, B‐lymphocyte depletion, and preservation of beta‐cell function. N Engl J Med [internet] 2009; 361:2143–52. Available at: http://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMoa0904452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dufort MJ, Greenbaum CJ, Speake C, Linsley PS. Cell type–specific immune phenotypes predict loss of insulin secretion in new‐onset type 1 diabetes. JCI Insight [Internet] 2019; 4. Available at: https://insight.jci.org/articles/view/125556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leete P, Willcox A, Krogvold L et al. Differential insulitic profiles determine the extent of β‐cell destruction and the age at onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes [internet] 2016; 65:1362–9. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2337/db15‐1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Willcox A, Richardson SJ, Walker LSK, Kent SC, Morgan NG, Gillespie KM. Germinal centre frequency is decreased in pancreatic lymph nodes from individuals with recent‐onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia [internet] 2017; 60:1294–303. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00125‐017‐4221‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brodie GM, Wallberg M, Santamaria P, Wong FS, Green EA. B‐cells promote intra‐islet CD8+ cytotoxic T‐cell survival to enhance type 1 diabetes. Diabetes [internet] 2008; 57:909–17. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2337/db07‐1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chamberlain N, Massad C, Oe T, Cantaert T, Herold KC, Meffre E. Rituximab does not reset defective early B cell tolerance checkpoints. J Clin Invest [internet] 2015; 126:282–7. Available at: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/83840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Linsley PS, Greenbaum CJ, Speake C, Long SA, Dufort MJ. B lymphocyte alterations accompany abatacept resistance in new‐onset type 1 diabetes. JCI Insight [Internet] 2019; 4. Available at: https://insight.jci.org/articles/view/126136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hamad ARA, Ahmed R, Donner T, Fousteri G. B cell‐targeted immunotherapy for type 1 diabetes: What can make it work? Discov Med [internet] 2016; 21:213–219. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27115172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pearson JA, Wong FS, Wen L. The importance of the non obese diabetic (NOD) mouse model in autoimmune diabetes. J Autoimmun 2016; 66:76–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wooldridge L, Ekeruche‐Makinde J, van den Berg HA et al. A single autoimmune T cell receptor recognizes more than a million different peptides. J Biol Chem [internet] 2012; 287:1168–77. Available at: http://www.jbc.org/lookup/doi/10.1074/jbc.M111.289488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wicker LS, Leiter EH, Todd JA et al. Beta 2‐microglobulin‐deficient NOD mice do not develop insulitis or diabetes. Diabetes [internet] 1994; 4:500–4. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2337/diabetes.43.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Serreze DV, Leiter EH, Christianson GJ, Greiner D, Roopenian DC. Major histocompatibility complex class I‐deficient NOD‐B2mnull mice are diabetes and insulitis resistant. Diabetes [internet] 1994; 43:505–9. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2337/diabetes.43.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Itoh N, Hanafusa T, Miyazaki A et al. Mononuclear cell infiltration and its relation to the expression of major histocompatibility complex antigens and adhesion molecules in pancreas biopsy specimens from newly diagnosed insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus patients. J Clin Invest [internet] 1993; 92:2313–22. Available at: http://www.jci.org/articles/view/116835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Willcox A, Richardson SJ, Bone AJ, Foulis AK, Morgan NG. Analysis of islet inflammation in human type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol [internet] 2009; 155:173–81. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365‐2249.2008.03860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Foulis AK, Liddle CN, Farquharson MA, Richmond JA, Weir RS. The histopathology of the pancreas in Type I (insulin‐dependent) diabetes mellitus: a 25‐year review of deaths in patients under 20 years of age in the United Kingdom. Diabetologia [internet] 1986; 29:267–74. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF00452061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Coppieters KT, Dotta F, Amirian N et al. Demonstration of islet‐autoreactive CD8 T cells in insulitic lesions from recent onset and long‐term type 1 diabetes patients. J Exp Med [Internet] 2012; 209:51–60. Available at https://rupress.org/jem/article/209/1/51/40983/Demonstration‐of‐isletautoreactive‐CD8‐T‐cells‐in. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Foulis A, Farquharson M, Meager A. Immunoreactive α‐INTERFERON IN insulin‐secreting β cells in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Lancet [internet] 1987; 330:1423–7. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673687911287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Richardson SJ, Rodriguez‐Calvo T, Gerling IC et al. Islet cell hyperexpression of HLA class I antigens: a defining feature in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia [internet] 2016; 59:2448–58. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00125‐016‐4067‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tai N, Peng J, Liu F et al. Microbial antigen mimics activate diabetogenic CD8 T cells in NOD mice. J Exp Med [internet] 2016; 213:2129–46. Available at: https://rupress.org/jem/article/213/10/2129/42010/Microbial‐antigen‐mimics‐activate‐diabetogenic‐CD8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cole DK, Bulek AM, Dolton G et al. Hotspot autoimmune T cell receptor binding underlies pathogen and insulin peptide cross‐reactivity. J Clin Invest [internet] 2016; 126:2191–204. Available at: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/85679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Richardson SJ, Morgan NG. Enteroviral infections in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes: new insights for therapeutic intervention. Curr Opin Pharmacol [internet] 2018; 43:11–9. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1471489217302205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wong FS, Visintin I, Wen L, Flavell RA, Janeway CA. CD8 T cell clones from young nonobese diabetic (NOD) islets can transfer rapid onset of diabetes in NOD mice in the absence of CD4 cells. J Exp Med [internet] 1996; 183:67–76. Available at: https://rupress.org/jem/article/183/1/67/58343/CD8‐T‐cell‐clones‐from‐young‐nonobese‐diabetic‐NOD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wong FS, Karttunen J, Dumont C et al. Identification of an MHC class I‐restricted autoantigen in type 1 diabetes by screening an organ‐specific cDNA library. Nat Med [internet] 1999; 5:1026–31. Available at: http://www.nature.com/articles/nm0999_1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Skowera A, Ellis RJ, Varela‐Calviño R et al. CTLs are targeted to kill β cells in patients with type 1 diabetes through recognition of a glucose‐regulated preproinsulin epitope. J Clin Invest 2008; 118:3390–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sutherland DE, Sibley R, Xu XZ et al. Twin‐to‐twin pancreas transplantation: reversal and reenactment of the pathogenesis of type I diabetes. Trans Assoc Am Physicians 1984; 97:80–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yeo L, Woodwyk A, Sood S et al. Autoreactive T effector memory differentiation mirrors β cell function in type 1 diabetes. J Clin Invest [internet] 2018; 128:3460–74. Available at: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/120555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rigby MR, DiMeglio LA, Rendell MS et al. Targeting of memory T cells with alefacept in new‐onset type 1 diabetes (T1DAL study): 12 month results of a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol [internet] 2013; 1:284–94. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2213858713701116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rigby MR, Harris KM, Pinckney A et al. Alefacept provides sustained clinical and immunological effects in new‐onset type 1 diabetes patients. J Clin Invest [internet] 2015; 125:3285–96. Available at: http://www.jci.org/articles/view/81722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Roep BO, Solvason N, Gottlieb PA et al. Plasmid‐encoded proinsulin preserves C‐peptide while specifically reducing proinsulin‐specific CD8+ T cells in type 1 diabetes. Sci Transl Med [internet] 2013; 5:191ra82. Available at: https://stm.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.3006103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hull CM, Peakman M, Tree TIM. Regulatory T cell dysfunction in type 1 diabetes: what’s broken and how can we fix it? Diabetologia 2017; 60:1839–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Culina S, Lalanne AI, Afonso G et al. Islet‐reactive CD8+ T cell frequencies in the pancreas, but not in blood, distinguish type 1 diabetic patients from healthy donors. Sci Immunol [internet] 2018; 3:eaao4013. Available at: https://immunology.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/sciimmunol.aao4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fonseca VR, Ribeiro F, Graca L. T follicular regulatory (Tfr) cells: dissecting the complexity of Tfr‐cell compartments. Immunol Rev [internet] 2019; 28:112–27. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/imr.12739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Weingartner E, Golding A. Direct control of B cells by Tregs: an opportunity for long‐term modulation of the humoral response. Cell Immunol [internet] 2017; 318:8–16. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0008874917300813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pedroza‐Pacheco I, Madrigal A, Saudemont A. Interaction between natural killer cells and regulatory T cells: perspectives for immunotherapy. Cell Mol Immunol [internet] 2013; 10:222–9. Available at: http://www.nature.com/articles/cmi20132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Okeke EB, Uzonna JE. The pivotal role of regulatory T cells in the regulation of innate immune cells. Front Immunol [internet] 2019; 9:10. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00680/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Josefowicz SZ, Lu L‐F, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu Rev Immunol [internet] 2012; 30:531–64. Available at: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Himmel ME, Crome SQ, Ivison S, Piccirillo C, Steiner TS, Levings MK. Human CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells produce CXCL8 and recruit neutrophils. Eur J Immunol [internet] 2011; 41:306–12. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/eji.201040459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dirice E, Kahraman S, De Jesus DF et al. Increased β‐cell proliferation before immune cell invasion prevents progression of type 1 diabetes. Nat Metab [internet] 2019; 1:509–18. Available at: http://www.nature.com/articles/s42255‐019‐0061‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bacchetta R, Barzaghi F, Roncarolo M‐G. From IPEX syndrome to FOXP3 mutation: a lesson on immune dysregulation. Ann NY Acad Sci [internet] 2018; 1417:5–22. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/nyas.13011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Costa‐Carvalho BT, de Moraes‐Pinto MI, de Almeida LC et al. A remarkable depletion of both naïve CD4+ and CD8+ with high proportion of memory T cells in an IPEX infant with a FOXP3 mutation in the forkhead domain. Scand J Immunol [internet] 2008; 68:85–91. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365‐3083.2008.02055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rubio‐Cabezas O, Minton JAL, Caswell R et al. Clinical heterogeneity in patients with FOXP3 mutations presenting with permanent neonatal diabetes. Diabetes Care [internet] 2009; 32:111–6. Available at: http://care.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2337/dc08‐1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cepika A‐M, Sato Y, Liu JM‐H, Uyeda MJ, Bacchetta R, Tregopathies RMG. Monogenic diseases resulting in regulatory T‐cell deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol [internet] 2018; 142:1679–95. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0091674918315173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nyaga DM, Vickers MH, Jefferies C, Perry JK, O’Sullivan JM. The genetic architecture of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Mol Cell Endocrinol [internet] 2018. Dec; 477:70–80. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0303720718301886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pociot F, Akolkar B, Concannon P et al. Genetics of type 1 diabetes: what’s next? Diabetes [internet] 2010; 59:1561–71. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2337/db10‐0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Long A, Buckner JH. Intersection between genetic polymorphisms and immune deviation in type 1 diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes [Internet] 2013; 20:285–91. Available at: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=01266029‐201308000‐00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Valta M, Gazali AM, Viisanen T et al. Type 1 diabetes linked PTPN22 gene polymorphism is associated with the frequency of circulating regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol 2020; 50:581–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Marwaha AK, Crome SQ, Panagiotopoulos C et al. Cutting edge: increased IL‐17‐secreting T cells in children with new‐onset type 1 diabetes. J Immunol [internet] 2010; 185:3814–18. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=20810982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. McClymont SA, Putnam AL, Lee MR et al. Plasticity of human regulatory T cells in healthy subjects and patients with type 1 diabetes. J Immunol [internet] 2011; 186:3918–26. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21368230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Long SA, Cerosaletti K, Bollyky PL et al. Defects in IL‐2R signaling contribute to diminished maintenance of FOXP3 expression in CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T‐cells of type 1 diabetic subjects. Diabetes [internet] 2010; 59:407–15. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19875613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cerosaletti K, Schneider A, Schwedhelm K et al. Multiple autoimmune‐associated variants confer decreased IL‐2R signaling in CD4+CD25hi T cells of Type 1 diabetic and multiple sclerosis patients. PLOS ONE [internet] 2013; 8:e83811. Available at: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Patterson SJ, Pesenacker AM, Wang AY et al. T regulatory cell chemokine production mediates pathogenic T cell attraction and suppression. J Clin Invest [internet] 2016; 126:1039–51. Available at: https://www.jci.org/articles/view/83987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pesenacker AM, Chen V, Gillies J et al. Treg gene signatures predict and measure type 1 diabetes trajectory. JCI Insight [internet] 2019. Available at: http://insight.jci.org/articles/view/123879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pesenacker AM, Wang AY, Singh A et al. A regulatory T‐cell gene signature is a specific and sensitive biomarker to identify children with new‐onset Type 1 diabetes. Diabetes [internet] 2016; 65:1031–9. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2337/db15‐0572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bluestone JA, Buckner JH, Fitch M et al. Type 1 diabetes immunotherapy using polyclonal regulatory T cells. Sci Transl Med [internet] 2015; 7:315ra189. Available at: https://stm.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.aad4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ferreira LMR, Muller YD, Bluestone JA, Tang Q. Next‐generation regulatory T cell therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov [internet] 2019; 18:749–69. Available at: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41573‐019‐0041‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tang Q, Henriksen KJ, Bi M et al. In vitro‐expanded antigen‐specific regulatory T cells suppress autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med [internet] 2004; 199:1455–65. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15184499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tarbell KV, Yamazaki S, Olson K, Toy P, Steinman RM. CD25+ CD4+ T cells, expanded with dendritic cells presenting a single autoantigenic peptide, suppress autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med [internet] 2004; 199:1467–77. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15184500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Gundersen E. Is Diabetes of infectious origin? J Infect Dis [internet] 1927; 41:197–202. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article‐lookup/doi/10.1093/infdis/41.3.197. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Dunne JL, Richardson SJ, Atkinson MA et al. Rationale for enteroviral vaccination and antiviral therapies in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia [internet] 2019; 62:744–53. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00125‐019‐4811‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hyöty H. Viruses in type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes [internet] 2016; 17:56–64. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/pedi.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Yeung W‐CG, Rawlinson WD, Craig ME. Enterovirus infection and type 1 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational molecular studies. BMJ [internet] 2011; 342:d35. Available at: http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.d35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Craig ME, Nair S, Stein H, Rawlinson WD. Viruses and type 1 diabetes: a new look at an old story. Pediatric Diabetes 2013; 15:149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Foulis AK, McGill M, Farquharson MA, Hilton DA. A search for evidence of viral infection in pancreases of newly diagnosed patients with IDDM. Diabetologia 1997; 40:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Richardson SJ, Willcox A, Bone AJ, Foulis AK, Morgan NG. The prevalence of enteroviral capsid protein vp1 immunostaining in pancreatic islets in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia [internet] 2009; 52:1143–51. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00125‐009‐1276‐0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Ylipaasto P, Klingel K, Lindberg AM et al. Enterovirus infection in human pancreatic islet cells, islet tropism in vivo and receptor involvement in cultured islet beta cells. Diabetologia 2004; 47:225–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bennettjenson A. Pancreatic islet‐cell damage in children with fatal viral infections. Lancet [internet] 1980. Aug; 316:354–8. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673680903499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. M Hodik, A Lukinius, O Korsgren, G Frisk. Tropism analysis of two coxsackie B5 strains reveals virus growth in human primary pancreatic islets but not in exocrine cell clusters in vitro . Open Virol J [internet] 2013; 7:49–56. Available at: https://openvirologyjournal.com/VOLUME/7/PAGE/49/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ifie E, Russell MA, Dhayal S et al. Unexpected subcellular distribution of a specific isoform of the Coxsackie and adenovirus receptor, CAR‐SIV, in human pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia [internet] 2018; 61:2344–55. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00125‐018‐4704‐1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Frisk G, Diderholm H. Tissue culture of isolated human pancreatic islets infected with different strains of Coxsackievirus B4: assessment of virus replication and effects on islet morphology and insulin release. Exp Diabesity Res 2000; 1:165–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Bergholdt R, Brorsson C, Palleja A et al. Identification of novel type 1 diabetes candidate genes by integrating genome‐wide association data, protein‐protein interactions, and human pancreatic islet gene expression. Diabetes [internet] 2012; 61:954–62. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/doi/10.2337/db11‐1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Eizirik DL, Sammeth M, Bouckenooghe T et al. The human pancreatic islet transcriptome: expression of candidate genes for Type 1 diabetes and the impact of pro‐inflammatory cytokines. PLOS Genet [internet] 2012; 8:e1002552. Available at: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Marroqui L, Dos Santos RS, Fløyel T et al. TYK2, a candidate gene for Type 1 diabetes, modulates apoptosis and the innate immune response in human pancreatic β‐cells. Diabetes [internet] 2015; 64:3808–17. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2337/db15‐0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Hultcrantz M, Hühn MH, Wolf M et al. Interferons induce an antiviral state in human pancreatic islet cells. Virology [internet] 2007; 367:92–101. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0042682207003509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Cinek O, Tapia G, Witsø E et al. Enterovirus RNA in peripheral blood may be associated with the variants of rs1990760, a common type 1 diabetes associated polymorphism in IFIH1. PLOS ONE [internet] 2012; 7:e48409. Available at: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Sarmiento L, Frisk G, Anagandula M, Cabrera‐Rode E, Roivainen M, Cilio CM. Expression of innate immunity genes and damage of primary human pancreatic islets by epidemic strains of echovirus: implication for post‐virus islet autoimmunity. PLOS ONE [internet] 2013; 8:e77850. Available at: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Sarmiento L, Cubas‐Dueñas I, Cabrera‐Rode E. Evidence of association between type 1 diabetes and exposure to enterovirus in Cuban children and adolescents. MEDICC Rev [Internet] 2013; 15:29–32. Available at: http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1555‐79602013000100007&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Morgan NG, Richardson SJ. Enteroviruses as causative agents in type 1 diabetes: loose ends or lost cause? Trends Endocrinol Metab [Internet] 2014; 25:611–9. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1043276014001520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Krogvold L, Edwin B, Buanes T et al. Detection of a low‐grade enteroviral infection in the Islets of Langerhans of living patients newly diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetes [internet] 2015; 64:1682–7. Available at: http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2337/db14‐1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Richardson SJ, Leete P, Bone AJ, Foulis AK, Morgan NG. Expression of the enteroviral capsid protein VP1 in the islet cells of patients with type 1 diabetes is associated with induction of protein kinase R and downregulation of Mcl‐1. Diabetologia [internet] 2013; 56:185–93. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00125‐012‐2745‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Dotta F, Censini S, van Halteren AGS et al. Coxsackie B4 virus infection of beta cells and natural killer cell insulitis in recent‐onset type 1 diabetic patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA [internet] 2007; 104:5115–20. Available at: http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0700442104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Busse N, Paroni F, Richardson SJ et al. Detection and localization of viral infection in the pancreas of patients with type 1 diabetes using short fluorescently‐labelled oligonucleotide probes. Oncotarget [internet] 2017; 8:12620–36. Available at: http://www.oncotarget.com/fulltext/14896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Foulis AK, Farquharson MA, Hardman R. Aberrant expression of Class II major histocompatibility complex molecules by B cells and hyperexpression of Class I major histocompatibility complex molecules by insulin containing islets in Type 1 (insulin‐dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia [internet] 1987; 30:333–43. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF00299027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Stone VM, Hankaniemi MM, Svedin E et al. A Coxsackievirus B vaccine protects against virus‐induced diabetes in an experimental mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia [internet] 2018; 61:476–81. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00125‐017‐4492‐z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.