This randomized clinical trial compares the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of single-agent carboplatin every 3 weeks, weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel, or conventional every-3-weeks carboplatin–paclitaxel in vulnerable older patients with ovarian cancer.

Key Points

Question

What is the optimal chemotherapy regimen for vulnerable older patients with ovarian cancer?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 120 vulnerable older patients with ovarian cancer, single-agent carboplatin was less feasible and active than a conventional every-3-weeks carboplatin–paclitaxel regimen (6 cycles completed in 48% vs 60% of patients, respectively), with significantly worse progression-free and overall survival outcomes, leading to premature termination of the trial.

Meaning

Despite relatively high toxic effects, a conventional doublet regimen should be offered to all older adult patients with ovarian cancer, irrespective of vulnerability.

Abstract

Importance

Single-agent carboplatin is often proposed instead of a conventional carboplatin–paclitaxel doublet in vulnerable older patients with ovarian cancer. Such an approach could have a detrimental effect on outcomes for these patients.

Objective

To compare the feasibility, efficacy, and safety of single-agent carboplatin every 3 weeks, weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel, or conventional every-3-weeks carboplatin–paclitaxel in vulnerable older patients with ovarian cancer.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This international, open-label, 3-arm randomized clinical trial screened 447 women 70 years and older with newly diagnosed stage III/IV ovarian cancer by determining their Geriatric Vulnerability Score; 120 patients with a Geriatric Vulnerability Score of 3 or higher were stratified by country and surgical outcome. Enrollment took place at 48 academic centers in France, Italy, Finland, Denmark, Sweden, and Canada from December 11, 2013, to April 26, 2017. Final analysis database lock April 2019. Data analysis was performed from February 1 to December 31, 2019.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to receive 6 cycles of (1) carboplatin, area under the curve (AUC) 5 mg/mL·min, plus paclitaxel, 175 mg/m2, every 3 weeks; (2) single-agent carboplatin, AUC 5 mg/mL·min or AUC 6 mg/mL·min, every 3 weeks; or (3) weekly carboplatin, AUC 2 mg/mL·min, plus paclitaxel, 60 mg/m2, on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was treatment feasibility, defined as the ability to complete 6 chemotherapy cycles without disease progression, premature toxic effects–related treatment discontinuation, or death.

Results

A total of 120 women were randomized. The mean and median age was 80 (interquartile range, 76-83; range, 70-94) years; 43 (36%) had a Geriatric Vulnerability Score of 4 and 13 (11%) had a Geriatric Vulnerability Score of 5; 40 (33%) had stage IV disease. During its third meeting, the independent data monitoring committee’s recommendation led to the termination of the trial because single-agent carboplatin was associated with significantly worse survival. Six cycles were completed in 26 of 40 (65%), 19 of 40 (48%), and 24 of 40 (60%) patients in the every-3-weeks combination, single-agent carboplatin, and weekly combination groups, respectively. Treatment-related adverse events were less common with the standard every-3-weeks combination (17 of 40 [43%]) than single-agent carboplatin or weekly combination therapy (both 23 of 40 [58%]). Treatment-related deaths occurred in 4 patients (2 of 40 [5%] in each combination group).

Conclusions and Relevance

This randomized clinical trial shows that compared with every-3-weeks or weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel regimens, single-agent carboplatin was less active with significantly worse survival outcomes in vulnerable older patients with ovarian cancer.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02001272

Introduction

In women with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer, the standard chemotherapy regimen is carboplatin and paclitaxel every 3 weeks. However, alternative schedules and regimens are often used for vulnerable or older adult patients.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 Single-agent carboplatin is probably the most widely used treatment in older patients, but given conflicting results for such an approach,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 the Fourth Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference emphasized the need for additional research on treatment modification for older patients.1

Chronological age without consideration of clinical condition or frailty is a poor predictor of outcome.18 Geriatric assessment gathers information on functional, mental, and nutritional status, comorbidities, emotional conditions, social support, polypharmacy, and geriatric syndromes to improve treatment decisions19 and define tailored interventions. The French National Group of Investigators for the Study of Ovarian and Breast Cancer (GINECO) led a clinical trial program focusing on older patients with cancer. The first trial20 identified 3 independent prognostic factors for overall survival (OS): symptoms of depression, more than 6 different comedications per day, and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IV disease. The second trial21 indicated that depression (measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]) was significantly associated with worse OS. These 2 studies suggested poorer outcome with paclitaxel administration, raising questions about the value of carboplatin–paclitaxel doublets in older patients. The third trial22 identified 5 factors significantly associated with outcome: Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale score less than 6, Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale score less than 25, HADS score greater than 14, albuminemia (albumin level <35 g/L), and lymphopenia (lymphocyte count <1 × 109/L). These factors were combined to develop a Geriatric Vulnerability Score (GVS). A GVS of 3 or greater identified a particularly vulnerable population with significantly worse OS, treatment completion, and toxic effects. To determine the optimal chemotherapy regimen(s) for older vulnerable patients with ovarian cancer, we designed the Elderly Women With Ovarian Cancer (EWOC)-1 (European Network for Gynaecological Oncological Trial [ENGOT] OV-23) trial.

Methods

Study Design

This international, multicenter, open-label, phase 2 randomized clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02001272) was undertaken by the Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) and ENGOT groups, led by GINECO. Patients were enrolled from 48 academic centers in France, Italy, Finland, Denmark, Sweden, and Canada. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The protocol (Supplement 2) was approved by each participating country’s ethics committee. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.

Participants

Eligible patients were 70 years and older with newly diagnosed FIGO stage III or IV histologically or cytologically confirmed epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer, no clinically relevant organ dysfunction, and life expectancy greater than 3 months (Figure 1). Patients provided written informed consent to undergo GVS assessment. Those with a GVS of 3 or greater were eligible for the EWOC-1 trial and, after providing written informed consent, were randomized to receive 6 cycles of every-3-weeks carboplatin–paclitaxel (control), every-3-weeks single-agent carboplatin, or weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel. Patients were not paid to participate. Patients with a GVS less than 3 or not meeting eligibility criteria for randomization entered the EWOC-1 registry and were treated with investigator-selected chemotherapy.

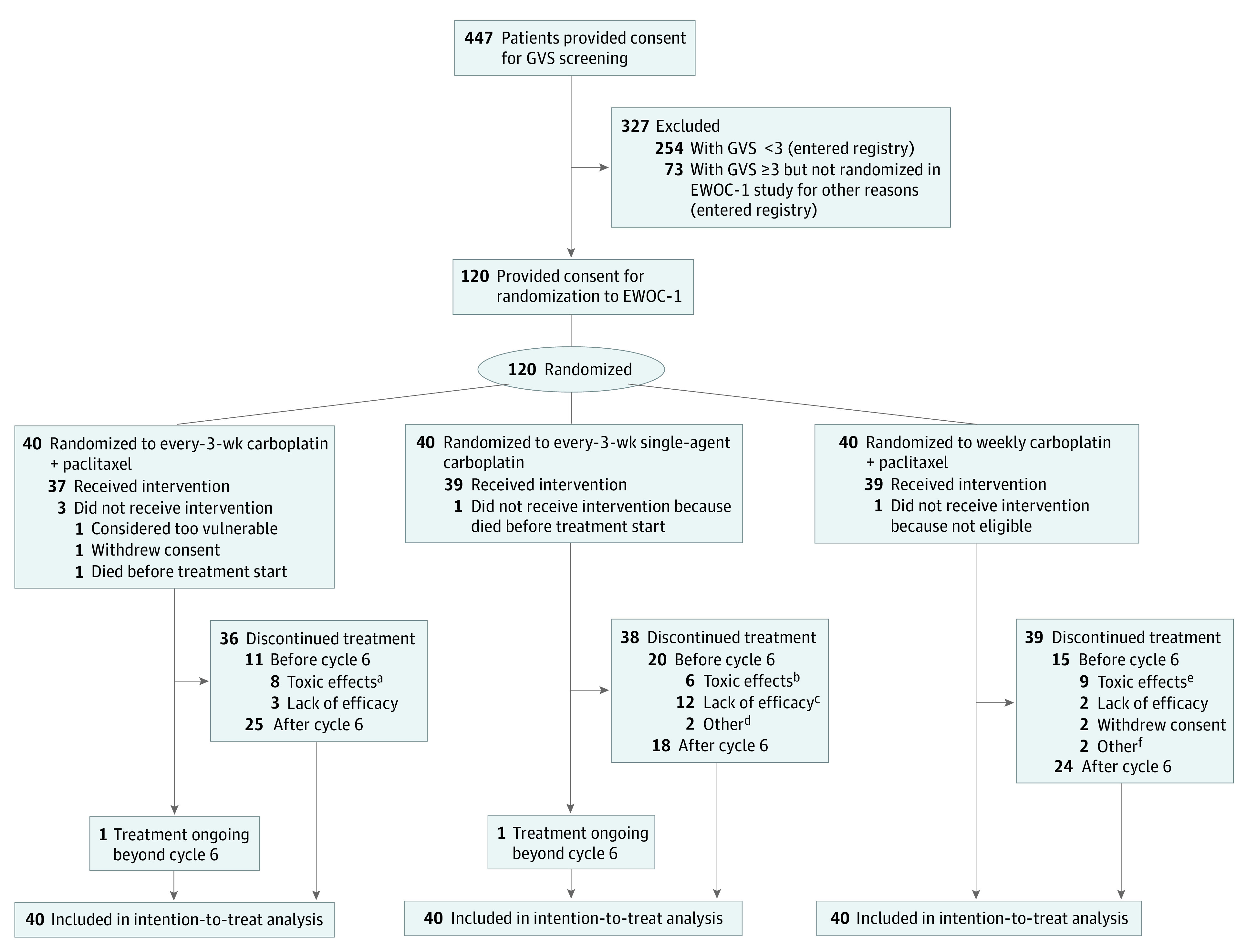

Figure 1. Trial Profile.

EWOC-1 indicates Elderly Women With Ovarian Cancer trial; GVS, Geriatric Vulnerability Score.

aHematologic events (n = 2); neuropathy (n = 2); other adverse events (AEs) (n = 2); toxic effect–related death (n = 2).

bRecorded as unacceptable toxic effect (hematologic toxic effect [n = 1]; allergy [n = 1]; other reason [n = 1]); investigator’s decision due to excess toxic effects (n = 2); patient’s decision because of toxic effects (n = 1).

cProgressive disease (n = 8); death due to progression (n = 4).

dNon–chemotherapy-related AEs (n = 2).

eHematologic toxic effect (n = 3); neuropathy (n = 3); other reasons (n = 3).

fNon–chemotherapy-related AEs (n = 1); loss to follow-up (n = 1).

Procedures

Eligible patients were stratified by country and outcome of initial debulking surgery (initial debulking surgery and no macroscopic residual disease vs initial debulking surgery and macroscopic residual disease or planned interval debulking surgery or inoperable) and randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio using a web-based system (Euraxipharma, https://ecrf.euraxipharma.fr/CSOnline/) and a minimization procedure.

The control regimen comprised intravenous carboplatin, area under the curve (AUC) 5 mg/mL·min, plus intravenous paclitaxel, 175 mg/m2, every 3 weeks. Single-agent carboplatin was administered at AUC 5 mg/mL·min or AUC 6 mg/mL·min every 3 weeks. The weekly combination regimen comprised carboplatin, AUC 2 mg/mL·min, plus paclitaxel, 60 mg/m2, both given on days 1, 8, and 15 every 4 weeks as in the MITO-5 trial.2 Patients were premedicated with corticosteroids, antihistamines, and H2-receptor antagonists according to local standards and the paclitaxel label. Protocol-defined carboplatin and paclitaxel dose reductions to manage toxic effects are summarized in eAppendix in Supplement 1. Beyond cycle 6, treatment continuation was at the investigator’s discretion.

Investigators assessed disease response or progression according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1. Tumors were assessed by pelvic and abdominal cross-sectional imaging at baseline, after cycle 6, and then at the investigator’s discretion until disease progression or for up to 24 months. Adverse events (AEs) were recorded at every cycle, graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.03).

Outcomes

The primary end point was feasibility, defined as completion of 6 chemotherapy cycles without premature discontinuation for unacceptable toxic effects (chemotherapy-related AE, treatment procedure leading to early treatment discontinuation, unplanned hospital admission, >14-day dose delay, >2 dose reductions, or death), disease progression, or death. Secondary outcomes included therapeutic strategy (feasibility of optimal surgery and postoperative chemotherapy), progression-free survival (PFS), OS, and safety.

Statistical Analysis

According to the 2-step Bryant and Day method to assess both efficacy and toxic effects, a maximum of 240 patients were to be enrolled over a 24-month period. In the first step, 66 patients (22 per treatment group) were planned. At the prespecified interim analysis, a regimen was to be dropped from the trial if more than 8 of 22 patients experienced treatment failure (disease progression or death from progression) or 6 of 22 patients experienced major AEs leading to early treatment discontinuation, hospitalization for toxic effects, or death. In the second step, 58 additional patients per remaining treatment group were to be enrolled, totaling 240 patients overall if all 3 regimens progressed to the second step. The trial was designed with a 2-sided α 1 error of .05 for insufficient activity (upper limit of 40% of patients with disease progression at 6 months) and a 2-sided α 2 error of .05 for excessive toxic effects (upper limit of 30% of patients with unacceptable toxic effects), with 90% power.

The chemotherapy completion rate for the primary end point was calculated with corresponding 95% CIs. The PFS and OS were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier methods. Medians were estimated, and corresponding 95% CIs were calculated. Data analysis was performed from February 1 to December 31, 2019. All analyses were performed in the intention-to-treat population (all randomized patients) using R software, version 3.5.3 (R Foundation).23

Results

Among 447 enrolled patients, 120 were randomized and 327 entered the nonrandomized registry (to be reported separately). The first patient was enrolled on December 11, 2013. Following apparent excess toxic effects in all groups, the independent data monitoring committee (IDMC) reviewed safety and efficacy in the first 65 patients, concluding that the prespecified interim analysis should be abandoned, accrual should continue, and the IDMC should review an interim analysis after 30 patients accrued to each arm had completed 6 cycles or experienced an event before cycle 6 (Supplement 2). After reviewing the interim analysis, the IDMC advocated suspending accrual until all 116 enrolled patients had had the opportunity to complete treatment. At the third safety review, the IDMC recommended closing the single-agent carboplatin arm for insufficient efficacy and excluding patients with a GVS of 3 if accrual restarted, as they derived significant benefit from the control vs weekly doublet. To detect a difference in treatment completion rate, 180 patients per group were required; therefore, the trial was stopped prematurely. At the database lock (April 2019), the median duration of follow-up was 12.7 (interquartile range [IQR], 4.5-25.5) months.

All but 5 of 120 randomized patients received treatment (Figure 1). Most (108 [90%]) were enrolled in France. All patients in the single-agent carboplatin arm received a starting dose of AUC 5 mg/mL·min. Patient characteristics were generally well balanced between treatment groups (Table). The mean and median age was 80 (IQR, 76-83; range, 70-94) years; GVS was 4 in 43 (36%) patients and 5 in 13 (11%) patients. Most patients had poor nutritional and autonomy scores, and more than half had mood disturbance. One-third (40 [33%]) of patients had stage IV disease and 8 (7%) had complete surgical resection. Postoperative complications were infrequent (nutritional, 1 patient in each of the 3 treatment arms; respiratory, 2 patients [7%] in the single-agent carboplatin arm; healing, 1 patient [3%] in the single-agent carboplatin arm; and other complications, 1 patient in each treatment arm).

Table. Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Every-3-wk carboplatin–paclitaxel (n = 40) | Every-3-wk carboplatin (n = 40) | Weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel (n = 40) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 79 (74-82) | 82 (78-84) | 80 (76-83) |

| Global GVS | |||

| 3 | 24 (60) | 19 (48) | 21 (53) |

| 4 | 14 (35) | 14 (35) | 15 (38) |

| 5 | 2 (5) | 7 (18) | 4 (10) |

| GVS per item | |||

| Albuminemia <35 g/L | 32 (80) | 33 (83) | 34 (85) |

| Katz ADL score <6 | 33 (83) | 34 (85) | 36 (90) |

| Lawton IADL score <25 | 36 (90) | 37 (93) | 37 (93) |

| HADS score >14 | 23 (58) | 28 (70) | 23 (58) |

| Lymphocyte count <1.0 × 109/L | 14 (35) | 16 (40) | 13 (33) |

| ECOG performance status | |||

| 0 | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 3 (8) |

| 1 | 15 (38) | 15 (38) | 13 (33) |

| 2 | 16 (40) | 16 (40) | 12 (30) |

| 3 | 4 (10) | 4 (10) | 7 (18) |

| Not available | 2 (5) | 3 (8) | 5 (13) |

| Countrya | |||

| France | 36 (90) | 36 (90) | 36 (90) |

| Italy | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 3 (8) |

| Finland | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 (3) |

| Denmark | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Primary tumor location | |||

| Ovary | 36 (90) | 34 (85) | 31 (78) |

| Primary peritoneal | 4 (10) | 4 (10) | 6 (15) |

| Fallopian tube | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (3) | 3 (8) |

| Histologic type | |||

| Serous | 24 (60) | 25 (63) | 28 (70) |

| Clear cell | 2 (5) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Mucinous | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 0 |

| Endometrioid | 0 | 2 (5) | 0 |

| Adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified | 10 (25) | 5 (13) | 3 (8) |

| Undifferentiated | 2 (5) | 4 (10) | 1 (3) |

| Other | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 6 (15) |

| Not available | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) |

| FIGO stage | |||

| III | 27 (68) | 24 (60) | 29 (73) |

| IV | 13 (33) | 16 (40) | 11 (28) |

| Initial debulking surgerya | |||

| None or macroscopic residuum | 37 (93) | 38 (95) | 37 (93) |

| No surgery | 14 (35) | 11 (28) | 12 (30) |

| Macroscopic residuum | 23 (58) | 27 (68) | 25 (63) |

| Complete surgical resection | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 3 (8) |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; GVS, Geriatric Vulnerability Score; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; IQR, interquartile range.

Stratification factor.

The primary end point analysis showed that 26 of 40 patients (65% [95% CI, 49%-79%]) in the control arm completed 6 treatment cycles compared with 19 of 40 (48% [95% CI, 32%-63%]) receiving single-agent carboplatin and 24 of 40 (60% [95% CI, 44%-74%]) receiving weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel. The median treatment duration was 6 cycles (IQR, 2.8-7.0; range, 0-9) in the control arm, 4.5 cycles (IQR, 2.8-6.0; range, 0-10) in the single-agent carboplatin group, and 6 cycles (IQR, 2.0-6.0; range, 0-9) in the weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel group.

As shown in Figure 1, the proportion of patients discontinuing treatment for toxic effects before cycle 6 was similar in the 3 treatment groups: 8 patients (20%) in the control arm, 6 patients (15%) in the single-agent carboplatin group, and 9 (23%) in the weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel group. However, considerably more patients in the single-agent carboplatin group (12 [30%]) than in the combination groups (3 [8%] in the control arm and 2 [5%] in the group receiving the weekly regimen) discontinued treatment prematurely because of lack of efficacy. Overall, 18 patients (15%) stopped treatment at cycle 1 (4 [10%] in the control arm, 6 [15%] in the single-agent carboplatin group, and 8 [20%] in the weekly combination group) and 7 (6%) died within 1 month of randomization (2 [5%], 3 [8%], and 2 [5%] patients, respectively, in the 3 treatment groups). Details of treatment exposure overall and by GVS subgroup are provided in eTables 1-3 in Supplement 1. Nineteen patients underwent interval debulking surgery (8 [20%] in the control arm, 4 [10%] receiving single-agent carboplatin, and 7 [18%] receiving weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel). There was no residual disease after interval debulking surgery in 2 of 8 (25%), 3 of 4 (75%), and 5 of 7 (71%) patients, respectively, in the 3 groups.

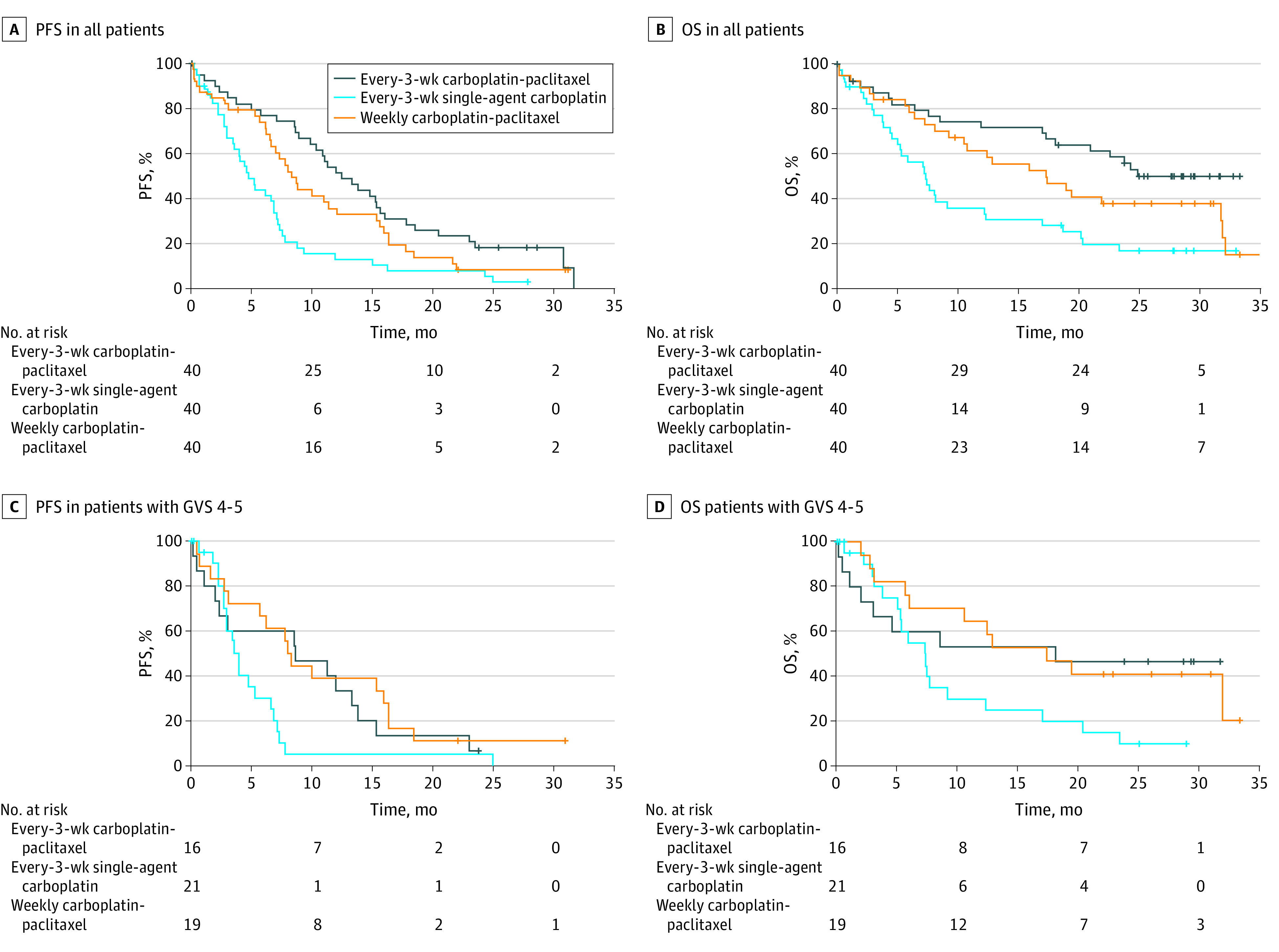

At the data cutoff, PFS events had been recorded in 106 patients (88%). The PFS was significantly longer in the control arm than with single-agent carboplatin (Figure 2A; eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Median PFS was 12.5 (95% CI, 10.3-15.3) months in the control arm, 4.8 (95% CI, 3.6-15.3) months with single-agent carboplatin, and 8.3 (95% CI, 6.6-15.3) months with weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel. The hazard ratio for single-agent carboplatin vs the control arm was 2.51 (95% CI, 1.56-4.04; Wald test P < .001). The OS results showed a similar pattern (Figure 2B; eTable 4 in Supplement 1). At the data cutoff date, 76 patients (63%) had died, most (56 of 76 [74%]) from ovarian cancer. Median OS was not reached (95% CI, 21.0-32.2 months) in the control arm, 7.4 (95% CI, 5.3-32.2) months with single-agent carboplatin, and 17.3 (95% CI, 10.8-32.2) months with weekly combination therapy. The hazard ratio for single-agent carboplatin vs the control arm was 2.79 (95% CI, 1.57-4.96; Wald test P < .001). Similar patterns were seen in the GVS 3 and the GVS 4 or 5 subgroups (Figure 2; eTable 4 and eFigure in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. Progression-Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS) in All Patients and Those With Geriatric Vulnerability Score (GVS) 4-5.

There was a higher incidence of grade 3 or greater thrombocytopenia and anemia in the single-agent carboplatin group than in either combination group, whereas grade 3 or greater neutropenia was more common with the weekly combination regimen (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). Low-grade gastrointestinal toxic effects, neuropathy, and alopecia were more frequent with paclitaxel-containing combination regimens than with single-agent carboplatin. Grade 5 AEs were reported in 3 (8%), 4 (10%), and 5 (13%) patients in the control arm, single-agent carboplatin, and weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel groups, respectively. These events were considered treatment related in 2 patients (5%) in the control arm (1 patient with febrile neutropenia with cardiac failure and kidney failure, 1 with hematologic toxic effects), none treated with single-agent carboplatin, and 2 (5%) treated with weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel (1 patient with septic shock and infection without neutropenia, 1 with septic shock and intestinal perforation).

In exploratory analyses of the primary end point according to GVS, the proportion of patients completing 6 cycles was lowest in the single-agent carboplatin group within the subgroup of patients with GVS of 3 (11 of 19 randomized patients [58%]; 11 of 18 treated patients [61%]). However, in the subgroup of 56 patients with GVS of 4 or 5, the proportion completing 6 cycles was similar in the control arm (5 of 16 randomized patients [31%]; 5 of 13 treated patients [38%]) and the single-agent carboplatin group (8 of 21 patients; 38%), and higher in the weekly combination group (10 of 19 randomized patients [53%]; 10 of 18 treated patients [56%]).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, EWOC-1 is the first randomized trial to compare chemotherapy regimens in a patient population selected based on vulnerability rather than chronological age alone. In this trial population of vulnerable patients 70 years and older, single-agent carboplatin was associated with significantly worse outcomes than either conventional every-3-weeks or weekly carboplatin–paclitaxel doublets. This finding held true for the most vulnerable subgroup within this population (GVS 4 or 5).

In clinical practice, a large proportion of older women are not treated according to guidelines with respect to both surgical and medical treatment.24 Furthermore, authors of a recent single-center study25 in 80 patients 65 years and older with gynecologic cancers suggested that frailty may help in selecting patients appropriate for less aggressive chemotherapy regimens. Our evidence from a randomized trial contradicts this conclusion, at least in ovarian cancer, demonstrating the negative effect of undertreatment in frail women. Patients receiving single-agent therapy were less likely to complete treatment, more likely to experience toxic effects, and, most importantly, had worse OS than those receiving standard-of-care treatment. Nevertheless, patient preference is an important factor leading to choice of best supportive care and should not be neglected.24

A strength of the present study is its focus on frailty assessed by the GVS, which provides a more meaningful biological and functional assessment of a patient’s condition than age alone. Although numerous indices for assessing frailty exist,5,18,26 results from EWOC-1 suggest that these geriatric measures are perhaps less important in treatment decision-making than initially suspected, as all patients, irrespective of frailty, should be offered standard therapy to optimize outcomes. However, a comprehensive geriatric assessment approach should lead not only to adaptation of specific cancer treatments but also an individualized and proactive care plan, a major aspect of multidisciplinary care in this vulnerable population. Another strength is the primary end point (completion of 6 chemotherapy cycles), which encapsulates measures of both toxic effects and efficacy, thus capturing the effect of treatment on both the quality and quantity of survival, unlike more traditional parameters.

After EWOC-1 began, results were reported from the nonrandomized NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group GOG273 trial,27 suggesting that single-agent carboplatin was associated with a higher premature treatment discontinuation rate than a carboplatin–paclitaxel doublet. Only 54% of patients completed 4 cycles of single-agent carboplatin without dose delay or reduction (vs 82% receiving combination therapy). However, patients electing to receive single-agent carboplatin were significantly older with significantly worse performance status than those receiving combination therapy. The authors concluded that by identifying populations with decreased tolerance, interventions could be designed to decrease toxic effects. However, the findings of the present study challenge the assumption that regimens anticipated to lessen toxic effects improve outcomes in frailer patients.

As well as ensuring that frail patients are offered standard chemotherapy, the necessary support must be provided to enable patients to continue and complete their therapy. The significantly lower likelihood of completing chemotherapy in patients with 2 or more vs fewer than 2 comorbidities in a recent analysis of 4617 older adult patients28 highlights the need for expertise in geriatric assessment when treating older patients with ovarian cancer, to identify medical and psychosocial barriers to treatment completion, and to provide the necessary support throughout treatment.

Limitations

The major limitation of this analysis is the premature discontinuation of the trial, resulting from a very cautious follow-up of treatment safety, based on a Bryant and Day design, in a vulnerable population expected to experience poor outcomes. The trial termination was decided according to IDMC conclusions (including excess toxic effects in all groups and inferior efficacy of single-agent carboplatin), although no definitive conclusions about the relative feasibility, efficacy, and safety of the 2 combination regimens could be reached. Only 4 of the 6 participating countries enrolled patients, and the enrollment rate was much slower than initially envisaged, contributing to the inability to extend accrual in the GVS 4 or 5 group, as suggested by the IDMC. A contributing factor might have been the lower proportion of patients with GVS 3 or higher among those included for GVS assessment. Analysis of the subgroup of patients with a GVS of 4 or 5 (almost half of the study population) suggested a similarly inferior clinical outcome with single-agent carboplatin vs the every-3-weeks doublet, despite similar chemotherapy completion rates. Another potential criticism is the differing cycle lengths, which complicates comparison of the regimens. Patients completing 6 cycles of the weekly regimen received 24 rather than 18 weeks of chemotherapy, albeit with a higher frequency of dose reductions. Interestingly, many of the chemotherapy discontinuations from the every-4-weeks combination regimen occurred in the first cycle, suggesting that the influence of later cycles on the primary end point might be relatively minor. Choice of the intention-to-treat population for analysis of the primary end point might be considered a weakness because of imbalances in the number of patients actually starting treatment. In the control arm, 3 randomized patients never started treatment (1 considered too vulnerable, 1 withdrew consent, 1 died before treatment start) and are counted as premature discontinuations despite no treatment exposure. However, in such an unstable population, in which patients are susceptible to AEs related to disease progression, chemotherapy toxic effects, and geriatric vulnerability, the high proportion of premature withdrawals is unsurprising. Finally, with small sample sizes, there are, as expected, some apparent imbalances between treatment arms. For example, compared with the control arm, the single-agent carboplatin arm appeared to include higher proportions of patients with GVS 4 or 5 (52% vs 40%), stage IV disease (40% vs 33%), or HADS score greater than 14 (70% vs 58%), perhaps hinting at a worse-prognosis population that could confound comparison.

Conclusions

Contrary to the current practice of considering single-agent carboplatin in frail patients, these results suggest that even vulnerable older women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer should be offered carboplatin–paclitaxel combination therapy. Management of vulnerable older patients with ovarian cancer should include, from cancer diagnosis, a personalized plan for oncogeriatric care, including both oncologic and geriatric treatment plans. If the oncologic plan considers the survival advantage provided by carboplatin–paclitaxel doublets, the geriatric plan must be prioritized in parallel, given the high toxic effects observed in this population, and should address the major components of the GVS (functionality, malnutrition, mood disorders). Additional trials are merited in vulnerable older adult patients to manage severe AEs without compromising outcomes.

List of Participating Investigators.

eAppendix. Dose Modification Scheme

eTable 1. Treatment Exposure in All Patients (n = 120)

eTable 2. Treatment Exposure in Subgroup of Patients With GVS 3 (n = 64)

eTable 3. Treatment Exposure in Subgroup of Patients With GVS 4 or 5 (n = 56)

eTable 4. Summary of Efficacy

eTable 5. Summary of Safety

eFigure. Efficacy in the Subgroup With Geriatric Vulnerability Score 3

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Freyer G, Tinker AV; Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup . Clinical trials and treatment of the elderly diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21(4):776-781. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821bb700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pignata S, Breda E, Scambia G, et al. A phase II study of weekly carboplatin and paclitaxel as first-line treatment of elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer. a Multicentre Italian Trial in Ovarian cancer (MITO-5) study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66(3):229-236. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hershman D, Jacobson JS, McBride R, et al. Effectiveness of platinum-based chemotherapy among elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94(2):540-549. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tortorella L, Vizzielli G, Fusco D, et al. Ovarian cancer management in the oldest old: improving outcomes and tailoring treatments. Aging Dis. 2017;8(5):677-684. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrero A, Fuso L, Tripodi E, et al. Ovarian cancer in elderly patients: patterns of care and treatment outcomes according to age and Modified Frailty Index. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2017;27(9):1863-1871. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabatier R, Calderon B Jr, Lambaudie E, et al. Prognostic factors for ovarian epithelial cancer in the elderly: a case-control study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(5):815-822. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fader AN, von Gruenigen V, Gibbons H, et al. Improved tolerance of primary chemotherapy with reduced-dose carboplatin and paclitaxel in elderly ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109(1):33-38. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maas HA, Kruitwagen RF, Lemmens VE, Goey SH, Janssen-Heijnen ML. The influence of age and co-morbidity on treatment and prognosis of ovarian cancer: a population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97(1):104-109. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lavoue V, Huchon C, Akladios C, et al. Management of epithelial cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, primary peritoneum. long text of the joint French clinical practice guidelines issued by FRANCOGYN, CNGOF, SFOG, GINECO-ARCAGY, endorsed by INCa. (part 2: systemic, intraperitoneal treatment, elderly patients, fertility preservation, follow-up). J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019;48(6):379-386. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2019.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm Group . Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy with either single-agent carboplatin or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in women with ovarian cancer: the ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9332):505-515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09738-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilpert F, du Bois A, Greimel ER, et al. Feasibility, toxicity and quality of life of first-line chemotherapy with platinum/paclitaxel in elderly patients aged ≥70 years with advanced ovarian cancer—a study by the AGO OVAR Germany. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(2):282-287. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giovanazzi-Bannon S, Rademaker A, Lai G, Benson AB III. Treatment tolerance of elderly cancer patients entered onto phase II clinical trials: an Illinois Cancer Center study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(11):2447-2452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.11.2447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenhauer EL, Tew WP, Levine DA, et al. Response and outcomes in elderly patients with stages IIIC-IV ovarian cancer receiving platinum-taxane chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106(2):381-387. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ceccaroni M, D’Agostino G, Ferrandina G, et al. Gynecological malignancies in elderly patients: is age 70 a limit to standard-dose chemotherapy? an Italian retrospective toxicity multicentric study. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85(3):445-450. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villella JA, Chaudhry T, Pearl ML, et al. Comparison of tolerance of combination carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy by age in women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;86(3):316-322. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruchim I, Altaras M, Fishman A. Age contrasts in clinical characteristics and pattern of care in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;86(3):274-278. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uyar D, Frasure HE, Markman M, von Gruenigen VE. Treatment patterns by decade of life in elderly women (≥70 years of age) with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;98(3):403-408. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar A, Langstraat CL, DeJong SR, et al. Functional not chronologic age: frailty index predicts outcomes in advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147(1):104-109. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.07.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pallis AG, Fortpied C, Wedding U, et al. EORTC elderly task force position paper: approach to the older cancer patient. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(9):1502-1513. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freyer G, Geay JF, Touzet S, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment predicts tolerance to chemotherapy and survival in elderly patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: a GINECO study. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(11):1795-1800. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trédan O, Geay JF, Touzet S, et al. ; Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux pour l’Etude des Cancers Ovariens . Carboplatin/cyclophosphamide or carboplatin/paclitaxel in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer? analysis of two consecutive trials from the Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux pour l’Etude des Cancers Ovariens. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(2):256-262. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falandry C, Weber B, Savoye AM, et al. Development of a geriatric vulnerability score in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer treated with first-line carboplatin: a GINECO prospective trial. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(11):2808-2813. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Accessed April 20, 2020. http://www.R-project.org/

- 24.van Walree IC, van Soolingen NJ, Hamaker ME, Smorenburg CH, Louwers JA, van Huis-Tanja LH. Treatment decision-making in elderly women with ovarian cancer: an age-based comparison. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2019;29(1):158-165. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2018-000026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hay CM, Donovan HS, Campbell GB, Taylor SE, Wang L, Courtney-Brooks M. Chemotherapy in older adult gynecologic oncology patients: can a phenotypic frailty score predict tolerance? Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152(2):304-309. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.11.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH, van Munster BC. Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):e437-e444. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70259-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Gruenigen VE, Huang HQ, Beumer JH, et al. Chemotherapy completion in elderly women with ovarian, primary peritoneal or fallopian tube cancer—an NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144(3):459-467. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.11.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairfield KM, Murray K, Lucas FL, et al. Completion of adjuvant chemotherapy and use of health services for older women with epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(29):3921-3926. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.1552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of Participating Investigators.

eAppendix. Dose Modification Scheme

eTable 1. Treatment Exposure in All Patients (n = 120)

eTable 2. Treatment Exposure in Subgroup of Patients With GVS 3 (n = 64)

eTable 3. Treatment Exposure in Subgroup of Patients With GVS 4 or 5 (n = 56)

eTable 4. Summary of Efficacy

eTable 5. Summary of Safety

eFigure. Efficacy in the Subgroup With Geriatric Vulnerability Score 3

Trial Protocol

Data Sharing Statement