Abstract

A relationship between ultrasound strain indices in carotid plaque to cognitive domains of executive and language function are studied in 42 symptomatic and 34 asymptomatic patients. The mean and standard deviation of the percentage stenosis were 72.10 ± 15.19 and 77.41 ± 11.20 for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients respectively. Pearson’s correlation between axial, lateral and shear strain indices versus executive and language composite scores was performed.. A significant inverse correlation for both executive and language function for symptomatic patients to strain indices was found. On the other hand, for asymptomatic patients only executive function was inversely correlated with the corresponding strain indices. Our hypothesis that micro-emboli from vulnerable plaque and possible ‘silent strokes’ may be responsible for decline in executive function for both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients’. Strokes and transient ischemic attacks may be responsible for further cognitive decline in language function for symptomatic patients.

I. INTRODUCTION

Carotid artery plaque rupture is a leading cause of ischemic stroke [1]. Up to 5 silent strokes are estimated to occur for every clinically recognized stroke [2]. These silent strokes are caused due to release of micro-emboli from vulnerable plaque and do not present with any clinical symptoms but may cause cognitive deficits due to blockages of smaller microvasculature.

However, it is the mechanical and structural properties of plaque that may determine probability of plaque rupture that may lead to strokes, transient ischemic attacks (TIA) and silent strokes. Ultrasound carotid strain imaging [3, 4] can be used to quantify the mechanical properties of carotid plaque to access vulnerability and thereby the probability of plaque rupture.

The relationship of carotid plaque instability and cognitive deficits in executive function was previously studied and it was found that unstable plaques in patients as identified by carotid strain imaging also had associated cognitive deficits in executive function [5–7]. In this paper we compare cognitive deficits in executive and language function observed in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. The objective of this paper is to provide a better understanding of the relationship between cognitive decline with vulnerable plaque and how this relates to occurrence of stroke and transient ischemic attacks. This paper expands on findings recently reported in [8], that describes the relationship between strain indices and multiple cognitive domains.

II. Methods

A. Human Participants

Our study included seventy-six patients that had severely stenotic carotid plaques and were scheduled for carotid endarterectomy (CEA). The study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison IRB and patients provided informed consent before participating in this study. Patients were divided into two groups, where the symptomatic group included patients that previously had a stroke or TIA and an asymptomatic group that included patients without symptoms of a prior stroke or TIA. Demographic information on patients is presented in Table 1. Prior to CEA patients underwent both ultrasound strain imaging and neurocognitive testing.

Table 1.

: Patient demographics.

| Symptomatic (n=42) | Asymptomatic (n=34) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 68.43 ± 10.62 years | 71.88 ± 7.04 years |

| Stenosis | 72.10 ± 15.19 % | 77.41 ± 11.20 % |

| Female | n=15, 35.71% | n=15, 44.12% |

B. Neurocognitive testing

Patients were administered a 60-minute cognitive testing protocol based on the guidelines of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders (NINDS) and the Canadian Stroke Network (CSN) [9] that was developed for stroke patients. The protocol was selected to test multiple cognitive skills such as executive function, visuospatial function, memory function and language function. The test used for executive function included two tests involving trail making, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV): Digit Symbol Coding and WAIS-IV: digit span [10, 11]. For Language function tests, Animal Naming and Controlled Oral Word Associates Test (COWAT): F-A-S and Boston Naming Test (BNT) were administered [12–15].

C. Ultrasound Strain Imaging

Radio frequency (RF) data were acquired on all patients using a Siemens Acuson S2000 system and an 18L6 transducer (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA, USA). Acquisitions over several cardiac cycles were made at the common carotid artery, the carotid bifurcation and internal carotid artery on both left and right carotid arteries for each patient. Plaque in each of the end diastolic frames were manually segmented by an experienced sonographer.

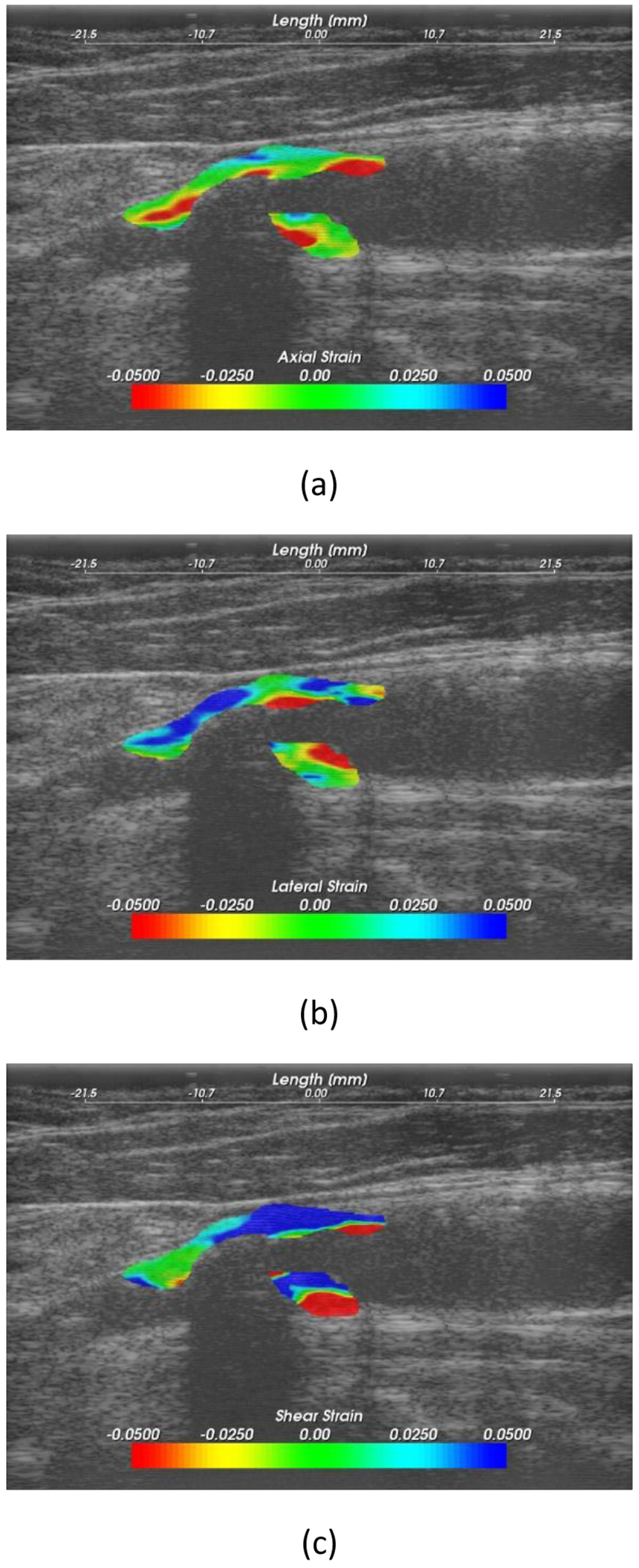

Displacement estimation was performed using a multi-level algorithm [16, 17] with Bayesian regularization [18]. Displacement information was used to propagate the manual segmentations from end diastole to other frames over the cardiac cycle. Axial, lateral and shear strain were calculated from accumulated displacement vector estimates. A fast GPU version of the algorithm was used for the estimation reported in this paper [19]. Figure 1, shows an example of axial, lateral and shear strain maps obtained. The maximum accumulated strain index (MASI) was calculated from the estimated strain distribution as previously described [5]. MASI quantifies the strain distribution in a small region of interest with highest strain values over the entire plaque and over a cardiac cycle.

Figure 1.

Example of (a) axial, (b) lateral and (c) shear strain maps.

C. Data analysis

All cognitive tests were demographically corrected according to published norms. In order to compare the cognitive scores to strain indices, composite cognitive scores were calculated for each cognitive domain compared. This was done by taking z-scores of all the cognitive scores and then taking the average of the z-scores for each cognitive domain. Hence a composite executive score and language score was calculated for each patient.

MATLAB 2017b was used for statistical analysis. Pearson’s cross correlation was performed between strain indices and composite cognitive scores. Pearson’s r-value was used to show the strength of the relationship and the p-value the statistical significance. Linear regression was also performed between strain indices and cognitive scores where the slope provides the directionality of these relationships.

III. Results

Symptomatic patients demonstrated significant inverse Pearson’s correlation values (p<0.05) of −0.43, −0.42 and −0.52 for axial, lateral and shear strain versus executive function. Significant inverse Pearson’s correlation values of −0.30 and −0.40 were also observed for lateral and shear strain versus language function, however axial strain presented an inverse Pearson’s correlation of −0.26 which was not significant.

Asymptomatic patients on the other hand only showed significant inverse Pearson’s correlation values (p<0.05) of −0.52, −0.45 and −0.47 for axial, lateral and shear strain versus executive function. The corresponding Pearson’s correlation of the axial, lateral and shear strain indices with language function were not significant with values −0.12, −0.19 and −0.10, respectively.

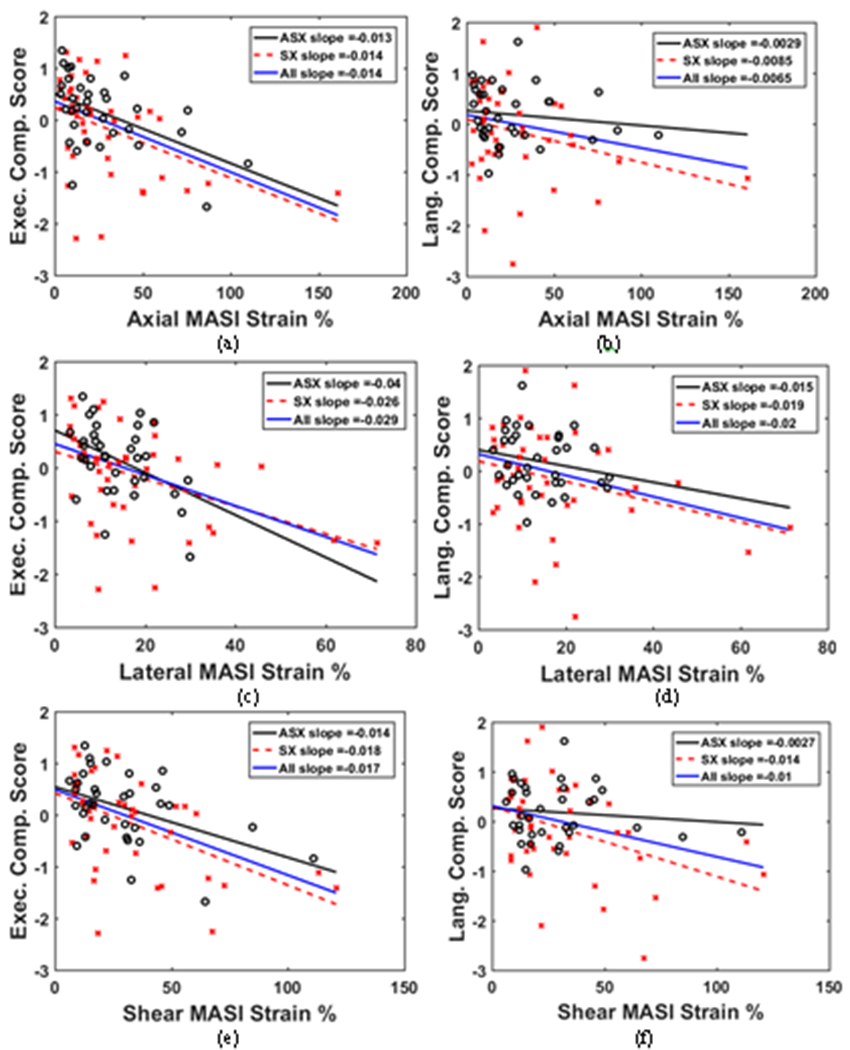

Figure 2, presents linear regression slopes for symptomatic, asymptomatic and for all patients. In Fig. 2(a), for axial strain it is observed that the slope is similar for all three patient categories for executive function. The corresponding slopes for language function in Fig. 2(b) demonstrate a stronger trend for symptomatic patients when compared to asymptomatic patients. Figure 2(c) shows that the slope is higher for asymptomatic for lateral strain versus executive function while a weak relationship of lateral strain to language function is observed for asymptomatic patients in Fig. 2(d). Shear strain presents observation similar to axial strain in Fig. 2(e) and 2(f).

Figure 2 –

Linear regression to estimate slope between axial MASI strain and (a) Executive composite score (b) Language composite score. In a similar manner slope is estimated for lateral MASI strain and (c) Executive composite score (d) Language composite score, and shear MASI strain and (e) Executive composite score (f) Language composite score, where o – asymptomatic patients and x- symptomatic patients.

Observe from Fig. 2 (a), (c) and (e) that plot executive function cognitive scores versus strain indices that the slopes for asymptomatic, symptomatic and all patients show only small deviations. On the other hand, in Fig. 2 (b), (d) and (f) plotting language function cognitive scores versus strain indices the slopes for asymptomatic and symptomatic patients diverge significantly.

IV. Discussion

Figure 2 and the Pearson’s correlation values demonstrate that both patient groups (symptomatic and asymptomatic) present with an inverse relationship between their respective carotid strain indices and their executive cognitive function. Note that patients with higher values of the strain indices presented with lower cognition scores. A significant decline in executive function is seen for both symptomatic and asymptomatic patient groups. However, only the symptomatic group showed a significant inverse relationship between strain indices and language function which was absent with the asymptomatic patient group.

These results indicate that although the patients in the asymptomatic group did not present with stroke or TIA symptoms, they were identified with underlying deficits in executive function. Symptomatic patients on the other hand suffered deficits in multiple other cognitive domains (language is presented here) in addition to executive function due to their prior stroke or TIA history. We believe that an explanation for asymptomatic patients presenting with deficits in executive function without incurring a stroke or TIA event could be the likelihood of silent strokes and resulting micro-emboli lodging in the microvasculature of the brain [20]. However, additional studies are required to confirm the prevalence of silent strokes and possible brain atrophy in the asymptomatic patient population.

Our results also point to the need to evaluate risk factors other than carotid stenosis alone, the current clinical criteria for surgical interventions such as CEA. Possible release of micro-emboli that can cause silent strokes may be a significant risk factor that has to be addressed to improve cognitive function in these patients. Identification of vulnerable plaques prone to rupture may be key in improving the quality of life in these asymptomatic patients. Previous results also demonstrate preservation of cognition in patients after CEA [7]. Determination of plaque composition non-invasively will also help with risk stratification in these patients[21, 22]

Clinical Relevance—

This work provides insight in how carotid artery plaque plays an important role in cognitive decline and the potential for ultrasound strain imaging in quantifying such plaque. Example: High strain values were associated with lower cognition scores because plaques that are more likely to be unstable exhibit higher strain values.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by NIH R01NS064034, 2R01CA112192 and 1R01HL147866.

Contributor Information

Nirvedh H. Meshram, Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health (UW-SMPH), Madison, WI, USA. He is now with the Department of Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027.

Daren Jackson, (UW-SMPH), Madison, WI 53706 USA..

Carol C. Mitchell, Department of Medicine, UW-SMPH, Madison, WI 53706 USA

Stephanie M. Wilbrand, Dempsey are with the Department of Neurological Surgery, UW-SMPH, Madison, WI 53792 USA.

Robert J. Dempsey, Dempsey are with the Department of Neurological Surgery, UW-SMPH, Madison, WI 53792 USA.

Bruce P. Hermann, Department of Neurology, UW-SMPH, Madison, WI 53706 USA

Tomy Varghese, Department of Medical Physics, UW-SMPH and Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706 USA.

References

- [1].Benjamin EJ et al. , “Heart disease and stroke statistics—2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association,” Circulation, vol. 137, no. 12, pp. e67–e492, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dempsey RJ, Vemuganti R, Varghese T, and Hermann BP, “A review of carotid atherosclerosis and vascular cognitive decline: a new understanding of the keys to symptomology,” Neurosurgery, vol. 67, no. 2, p. 484, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Céspedes I, Huang Y, Ophir J, and Spratt S, “Methods for estimation of subsample time delays of digitized echo signals,” Ultrason. Imaging, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 142–171, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Varghese T, “Quasi-static ultrasound elastography,” Ultrasound clinics, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 323–338, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Meshram NH et al. , “Quantification of carotid artery plaque stability with multiple region of interest based ultrasound strain indices and relationship with cognition,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 62, no. 15, pp. 6341–6360, Jul 17 2017, doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aa781f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dempsey RJ et al. , “The Preservation of Cognition 1 Yr After Carotid Endarterectomy in Patients With Prior Cognitive Decline,” Neurosurgery, vol. 82, no. 3, pp. 322–328, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dempsey RJ et al. , “Carotid atherosclerotic plaque instability and cognition determined by ultrasound-measured plaque strain in asymptomatic patients with significant stenosis,” J. Neurosurg, vol. 128, no. 1, pp. 111–119, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Meshram N et al. , “A cross-sectional investigation of cognition and ultrasound-based vascular strain indices,” Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 46–55, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hachinski V et al. , “National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–Canadian stroke network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards,” Stroke, vol. 37, no. 9, pp. 2220–2241, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alexander M, Stuss D, and Fansabedian N, “California Verbal Learning Test: performance by patients with focal frontal and non‐frontal lesions,” Brain, vol. 126, no. 6, pp. 1493–1503, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wechsler D, “Wechsler adult intelligence scale–Fourth Edition (WAIS–IV),” San Antonio, Texas: Psychological Corporation, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Benton AL, Hamsher K. d., and Sivan AB, Multilingual Aphasia Examination: Token Test. AJA associates, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Franzen MD, Haut MW, Rankin E, and Keefover R, “Empirical comparison of alternate forms of the Boston Naming Test,” The Clinical Neuropsychologist, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 225–229, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Isaacs B and Kennie AT, “The Set test as an aid to the detection of dementia in old people,” The British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 123, no. 575, pp. 467–470, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ober BA, Dronkers NF, Koss E, Delis DC, and Friedland RP, “Retrieval from semantic memory in Alzheimer-type dementia,” J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 75–92, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].McCormick M, Varghese T, Wang X, Mitchell CC, Kliewer M, and Dempsey RJ, “Methods for robust in vivo strain estimation in the carotid artery,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 57, no. 22, p. 7329, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shi H and Varghese T, “Two-dimensional multi-level strain estimation for discontinuous tissue,” Phys. Med. Biol, vol. 52, no. 2, p. 389, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].McCormick M, Rubert N, and Varghese T, “Bayesian regularization applied to ultrasound strain imaging,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng, vol. 58, no. 6, pp. 1612–1620, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Meshram NH and Varghese T, “GPU Accelerated Multilevel Lagrangian Carotid Strain Imaging,” IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, vol. 65, no. 8, pp. 1370–1379, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Berman SE et al. , “The relationship between carotid artery plaque stability and white matter ischemic injury,” NeuroImage: Clinical, vol. 9, pp. 216–222, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shi H, Varghese T, Mitchell CC, McCormick M, Dempsey RJ, and Kliewer MA, “In vivo attenuation and equivalent scatterer size parameters for atherosclerotic carotid plaque: Preliminary results,” Ultrasonics, vol. 49, no. 8, pp. 779–785, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Steffel CN et al. , “Attenuation Coefficient Parameter Computations for Tissue Composition Assessment of Carotid Atherosclerotic Plaque in Vivo,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 46, no. 6, pp. 1513–1532, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]