Abstract

Virilization is the medical term for describing a female who develops characteristics associated with male hormones (androgens) at any age, or when a newborn girl shows signs of prenatal male hormone exposure at birth. In girls, androgen levels are low during pregnancy and childhood. A first physiologic rise of adrenal androgens is observed at the age of 6 to 8 years and reflects functional activation of the zona reticularis of the adrenal cortex at adrenarche, manifesting clinically with first pubic and axillary hairs. Early adrenarche is known as “premature adrenarche.” It is mostly idiopathic and of uncertain pathologic relevance but requires the exclusion of other causes of androgen excess (eg, nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia) that might exacerbate clinically into virilization. The second modest physiologic increase of circulating androgens occurs then during pubertal development, which reflects the activation of ovarian steroidogenesis contributing to the peripheral androgen pool. However, at puberty initiation (and beyond), ovarian steroidogenesis is normally devoted to estrogen production for the development of secondary female bodily characteristics (eg, breast development). Serum total testosterone in a young adult woman is therefore about 10- to 20-fold lower than in a young man, whereas midcycle estradiol is about 10- to 20-fold higher. But if androgen production starts too early, progresses rapidly, and in marked excess (usually more than 3 to 5 times above normal), females will manifest with signs of virilization such as masculine habitus, deepening of the voice, severe acne, excessive facial and (male typical) body hair, clitoromegaly, and increased muscle development. Several medical conditions may cause virilization in girls and women, including androgen-producing tumors of the ovaries or adrenal cortex, (non)classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia and, more rarely, other disorders (also referred to as differences) of sex development (DSD). The purpose of this article is to describe the clinical approach to the girl with virilization at puberty, focusing on diagnostic challenges. The review is written from the perspective of the case of an 11.5-year-old girl who was referred to our clinic for progressive, rapid onset clitoromegaly, and was then diagnosed with a complex genetic form of DSD that led to abnormal testosterone production from a dysgenetic gonad at onset of puberty. Her genetic workup revealed a unique translocation of an abnormal duplicated Y-chromosome to a deleted chromosome 9, including the Doublesex and Mab-3 Related Transcription factor 1 (DMRT1) gene.

Learning Objectives

Identify the precise pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to virilization in girls at puberty considering that virilization at puberty may be the first manifestation of an endocrine active tumor or a disorder/difference of sex development (DSD) that remained undiagnosed before and may be life-threatening. Of the DSDs, nonclassical congenital adrenal hyperplasia occurs most often.

Provide a step-by-step diagnostic workup plan including repeated and expanded biochemical and genetic tests to solve complex cases.

Manage clinical care of a girl virilizing at puberty using an interdisciplinary team approach.

Care for complex cases of DSD manifesting at puberty, such as the presented girl with a Turner syndrome-like phenotype and virilization resulting from a complex genetic variation.

Keywords: virilization, androgen excess, disorders/differences of sex development (DSD), endocrine active tumors, genetic disorders of androgen excess

An 11.5-year-old girl was referred to our center for progressive clitoromegaly for 6 months. Her medical history revealed prematurity of 36 weeks’ gestation with a birth weight of 2920 g (–0.70 standard deviation score [SDS]) and length of 45.5 cm (–1.85 SDS). At birth, typical female external genitalia were noted without any signs of virilization (eg, no clitoromegaly). The child was assigned and raised as female. She was followed by a general pediatrician who noted a mild delay in psychomotor development for unknown reasons, which did not prompt further neurodevelopmental and genetic workup. The girl had pubarche and thelarche at around age 10 years. At presentation aged 11.5 years, physical examination revealed a height of 139.4 cm (–1.12 SDS), a weight of 43.6 lb (0.47 SDS), and body mass index of 22.4 kg/m2 (1.59 SDS), indicating overweight. Blood pressure was normal. She presented no syndromic features (eg, no typical signs for Turner syndrome [TS] or hypercortisolism). She showed a normal cardiopulmonary and abdominal examination; no intra-abdominal or inguinal masses were palpable. External genitalia inspection revealed a marked clitoromegaly of 3.5 × 1.5 cm in size but was otherwise typical female. No other signs of virilization such as voice deepening or severe acne were noted. Pubertal stage according to Tanner was pubic hair V, breast II, axillary hair II. In addition, rich bodily hair was noted consistent with hypertrichosis, but a Ferriman and Gallwey score was not assessed.

Background

Virilization at puberty is a rare disease manifestation of severe androgen excess, most often occurring in girls who have an undiagnosed underlying genetic condition or an acquired disorder affecting the adrenal glands or gonads. By contrast, mild to moderate hyperandrogenism may manifest with hirsutism at puberty and is characterized by excessive hair growth in androgen-sensitive areas, but without additional signs of masculinization. Hirsutism may be idiopathic or the first sign of a polycystic ovary syndrome (1).

In 46,XX adolescents, virilization can result from severe hyperandrogenism because of underlying excessive production or abnormal metabolism of adrenal or gonadal androgens. Paradoxically, in 46,XY females, virilization around puberty points toward a possible condition of severe undervirilization during sex determination and differentiation in fetal life, manifesting at birth with a female phenotype that may go unrecognized until puberty. At that time, high circulating androgens may then lead to the development of masculine bodily characteristics including deepening of the voice, clitoromegaly, severe acne, and severe, early-onset hirsutism.

Very rarely, drug abuse and environmental toxins may play a role and should be considered in unsolved cases (2). Timely investigation of the girl with virilization at puberty is essential, particularly if associated with a sudden onset of symptoms and/or a rapid progression because this should raise immediate concern of an androgen-secreting tumor of the ovaries or adrenal cortex (3-6).

Adrenal and Gonadal Tumors

Adrenocortical tumors are very rare (<0.2% of pediatric malignancies) and produce mostly not only excess androgens but also glucocorticoids (80%), thus manifesting with signs of hypercortisolism (Cushing syndrome) (6). Furthermore, they are often associated with particular genetic syndromes such as the Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome or with a familial genetic predisposition to cancers (mostly from p53 mutations) (6).

Likewise, (androgen-secreting) tumors of the ovary are rare (4). The most common pediatric ovarian neoplasms are teratomas. These are germ cell tumors (GCTs) that originate from pluripotent germ cells. The majority are benign and hormonally inactive. Dysgerminoma is the most common malignant GCTs, developing from a preexisting gonadoblastoma, predominantly in persons with gonadal dysgenesis. In fact, a GCT may be the first manifestation of an undiagnosed disorder of sex development (DSD) and should raise suspicion and specific workup (7). Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors are exceedingly rare malignancies that produce androgens and cause severe virilization. They have a high association with the DICER1 syndrome, a genetic disorder with increased risk for developing tumors in the lungs, kidneys, ovaries, thyroid, and several other locations (8).

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

The most common genetic cause of virilization before and at puberty is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) (Table 1). In addition, rarer forms of DSD affecting gonadal development and/or sex steroid synthesis and action need to be considered. CAH is in most cases caused by 21-hydroxylase deficiency resulting from autosomal recessive variants of the CYP21A2 gene, which has a prevalence of its classic form of 1 in 15,000 births worldwide (3, 9). Numerous genetic variants lead to glucocorticosteroid deficiency and adrenal androgen excess (3, 9). Virilization of the external genitalia at birth is therefore frequently seen in girls with more severe forms of classic CYP21A2 deficiency, and diagnosis is usually made by clinical manifestation and neonatal screening in most countries (3, 9). By contrast, prevalence of the less severe, nonclassic/late-onset form of CAH is estimated more than 10-fold higher in the general population, and it is diagnosed later in childhood, in adolescence, or even only in adulthood (9). Nonclassic CAH typically manifests with hyperandrogenism resulting in premature pubarche, accelerated linear growth, advanced skeletal maturation, and signs of virilization including clitoromegaly (10).

Table 1.

Genetic disorders of sex development associated with pubertal virilization

| Gonadal dysgenesis |

|---|

| -Structural or numerical aberrations of sex chromosomes |

| -Variants in genes involved in gonadal development (eg, WT1, NR5A1, DMRT1) |

| 46,XX congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) |

| -21-hydroxylase deficiency (CYP21A2) |

| -11-hydroxylase deficiency (CYP11B1) |

| -3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency (HSD3B2) |

| -Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase deficiency (POR) |

| 46,XX aromatase deficiency (CYP19A1) |

| 46,XY defects of androgen synthesis and action |

| -17β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency (HSD17B3) |

| -5α reductase deficiency (SRD5A2) |

| -Partial androgen receptor (AR) insensitivity syndrome (PAIS) |

Much rarer forms of CAH manifesting as late-onset virilization in individuals with a 46,XX karyotype include deficiencies of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 and 11β-hydroxylase caused by variants in the HSD3B2 and CYP11B1 genes, respectively (3, 11, 12). Even variants in the cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) gene, a cofactor supporting several enzymes of steroidogenesis (including CYP21A1, CYP17A1, and CYP19A1) could explain virilization of affected females at puberty, although so far only a polycystic ovary syndrome–like phenotype has been described in young women, whereas both 46,XY undervirilization and 46,XX virilization resulting from genetic variants of POR are typical at birth (3, 13). In addition, girls harboring autosomal recessive CYP19A1 variants may also present at puberty with virilization because aromatase deficiency leads to elevated androgens and low estrogens (14). However, more typically these girls experience virilization in utero, have ambiguous genitalia at birth, and may suffer from ovarian cysts during childhood.

Disorders of Androgen Synthesis and Action, Testicular Dysgenesis, and Ovotesticular DSD

Sudden virilization at puberty can be seen in 46,XY girls who have a disorder of androgen synthesis or action (Table 1). To the former group belong genetic variants of the SRD5A2 gene, catalyzing for DHT production from testosterone (15) and the HSD17B3 gene, converting androstenedione into testosterone (16). Why testicular testosterone or DHT production is more efficient than prenatally in pubertal girls who have these conditions has been attributed in part to isoenzyme activation at puberty (3), but remains overall insufficiently understood. Massive virilization and clarification of the underlying diagnosis may lead to sex/gender reassignment in these individuals in adolescence in up to 50% of cases (17).

Partial androgen insensitivity syndrome is a form of testicular DSD caused by pathogenic mutations in the Androgen Receptor gene, resulting in a decreased sensitivity to the actions of androgens and has a prevalence of 1 to 5:100,000 (18, 19). The 46,XY females with partial androgen insensitivity syndrome and typical female-looking external genitalia at birth may present signs of external genital masculinization, including clitoromegaly or posterior labial fusion later in childhood or puberty. (17).

Various forms of gonadal dysgenesis (ie, incomplete testicular or ovarian differentiation) can also lead to virilization of girls with puberty after initial manifestation with a typical female phenotype at birth (Table 1). Chromosomal aberrations and pathogenic variants in several genes involved in the determination of the (bipotential) gonads and their differentiation may be the underlying cause (20). Some of these genetic anomalies will cause isolated DSD, whereas others are associated with additional developmental defects in other organ systems and may form a characteristic syndrome. For example, heterozygous dominant-negative mutations of the Wilms tumor suppressor gene (WT1) on chromosome 11 can lead to the Denys-Drash syndrome, which is associated with kidney and gonad malformations and a high risk for developing a Wilms tumor (21). The 46,XY babies with Denys-Drash syndrome have varying degrees of gonadal dysgenesis, leading to ambiguous external genitalia or even a female phenotype with variable virilization during later pubertal development depending on presence of functional testicular tissue (21). Moreover, spontaneous virilization at puberty has been reported in several cases with nonsyndromic 46,XY DSD resulting from NR5A1/SF1 variants (22, 23). In these cases, testis histology revealed dysplastic gonads with Leydig cell hyperplasia at puberty. Interestingly, development of an ovotestis (ovotesticular DSD) has also been reported in a 46,XY subject with a deletion of NR5A1 and in some 46,XX subjects harboring the NR5A1 variants p.Arg92Trp/Gln (22).

Clinical Evaluation

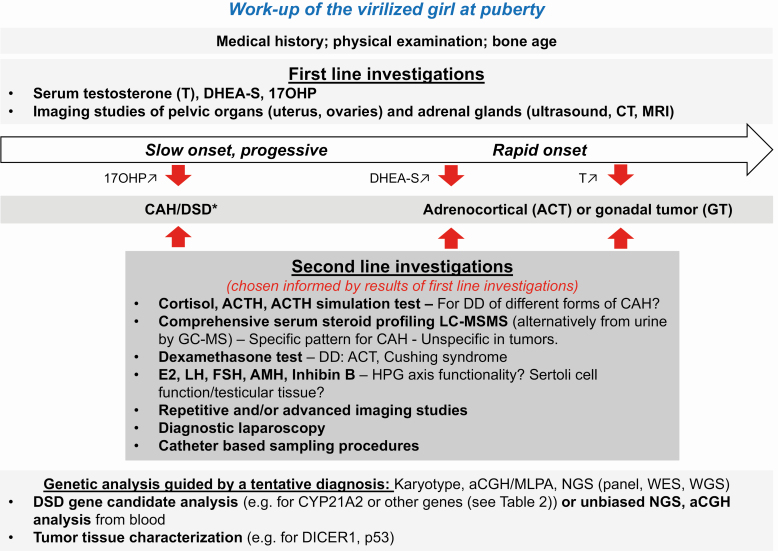

A thorough history and a focused clinical examination are crucial for successful diagnostic evaluation of patients with signs of severe androgen excess (24). Fig. 1 summarizes investigations that are recommended in the workup of a girl with virilization at puberty. Main differential diagnoses are included in the overview.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the workup of virilization of a girl at pubertal age.

Medical History

The medical history should include pregnancy and family history (eg, tumors, fertility issues), birth weight and gestational age at birth, somatic development and growth, age of adrenarche and thelarche, as well as menarche and menstrual characteristics (if already applicable). The timing and progression of the signs of virilization, such as clitoromegaly, acne, and hirsutism, along with a record of previous therapies (eg, hair removal procedures), are important for the diagnostic evaluation and management. History should include questions regarding virilization of the external genitalia (eg, clitoromegaly) or deepening of voice and breast atrophy.

Physical Examination

In the physical examination, blood pressure, height, weight and body mass index, waist-to-hip ratio, and signs of virilization, such as severe acne, hirsutism, and alopecia, should be assessed. The Ferriman and Gallwey score may be used to score hirsutism (25). It is also recommended to search for signs of Cushing syndrome such as rounded face, pink or purple stretch marks on the skin, muscle wasting, and centripetal fat distribution. Furthermore, it is important to determine the pubertal stage and perform a thorough examination of the external genital region looking for the presence of clitoromegaly and other signs of virilization or ambiguity.

Laboratory Investigations and Imaging Studies

Laboratory evaluations are essential in the workup of virilization (24). First-line investigations should include at least serum testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) and 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17OHP). Serum total testosterone levels are often more than 3 times elevated in patients with androgen-secreting ovarian tumors (26). DHEA-S (and adrenal androgen precursors such as DHEA and androstenedione together with glucocorticoids) are markedly elevated with adrenal tumors (27). Markedly increased 17OHP serum levels (3, 9) (or maybe 21-deoxycortisol in the future (28)), suggest CAH resulting from 21-hydroxylase deficiency. This diagnosis may be confirmed by a simple ACTH test and/or a targeted genetic test, if biochemical results are equivocal or genetical counseling is desired (9). Guided by the clinical findings and first laboratory results, imaging studies should ensue, including abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging of the adrenal glands and the pelvic organs to exclude androgen-secreting ovarian or adrenal tumors.

Second-line investigations (29) may include an ACTH stimulation test for evaluating adrenal gland function in cases of mildly elevated or normal basal 17OHP to exclude milder forms of (nonclassic) CAH (9), or a more comprehensive plasma or urine steroid profile assessed by a chromatographic mass spectrometric method to find specific patterns of rarer forms of CAH (Table 1) (30, 31). Patients suspected for Cushing syndrome should be evaluated with a 24-hour urine free cortisol, a diurnal ACTH and cortisol profile, and/or a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (3). Baseline gonadotrophins (FSH, LH) and estradiol should be measured and interpreted according to age-specific reference intervals. Suppressed or unmeasurably low serum LH and FSH may be found before puberty onset or with severe androgen excess leading to a negative feedback blockade of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Elevated LH and FSH is consistent with primary gonadal failure. Furthermore, measurement of serum Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) help in classifying the different forms of DSDs with and without gonadal dysgenesis (32). Normally, AMH is produced in high amounts in immature Sertoli cells, but physiologically declines once pubertal testosterone production starts. In 46,XY DSD, AMH is low in gonadal dysgenesis, but normal or elevated with defects of androgen synthesis or action. In chromosomal and 46,XY DSD with suspected gonadal dysgenesis, AMH levels indicate the existence of functional testicular tissue, (32, 33). Granulosa cells of primary and small antral ovarian follicles produce only small amounts of AMH from late fetal life until menopause. In 46,XX DSD elevated AMH levels indicate ovotesticular DSD with usually functional ovarian tissue but dysgenetic testicular tissue (32). Tumor markers such as α-fetoprotein, β-human chorionic gonadotrophin, lactate dehydrogenase, inhibin, and cancer antigen 125 are positive in 50% to 80% of malignant ovarian lesions, but may also be positive in 20% of benign ovarian germ cell tumors (4). Repetitive imaging studies may be necessary, in case of unsolved tumor suspicion and/or localization. If still unsuccessful, catheter procedures for adrenal vein sampling may be considered for diagnosing and localizing suspected adrenal tumors, whereas diagnostic laparoscopy and biopsy may be performed for suspected gonadal tumors.

Genetic tests are now standard for diagnostic workup of many disorders to confirm a diagnosis at the molecular level and allow for genetic counseling and prognostic evaluation. This may include a simple karyotype, an array comparative genomic hybridization, a candidate gene or an unbiased next-generation sequencing (eg, whole exome or genome sequencing) approach. The appropriate method for genetic testing depends on the suspected diagnosis and is best advised by a geneticist.

Returning to the Patient

First-line investigations showed a very high serum testosterone and normal values for DHEA-S and 17OHP, orientating the diagnosis toward a gonadal rather than an adrenal origin of androgen excess (Table 2). Gonadal dysgenesis was suspected because of elevated LH and FSH (FSH > LH), and undetectable estradiol (E2). AMH was low (0.53 ng/mL; normal value <9.00 ng/mL). Ultrasound revealed a prepubertally sized uterus, normal adrenals, and gonads that were first described as normal, but on later review of images not clearly detectable; no tumor was found. Bone age was concordant with chronological age according the Greulich-Pyle method. The 24-hour urine steroid profile excluded any form of nonclassic CAH and Cushing syndrome, but confirmed very high excretion of androgen metabolites (>3-fold of normal). The ACTH stimulation test showed normal reactivity of adrenal steroids, and the dexamethasone suppression test revealed normal inhibition of adrenal steroidogenesis. Overall, all these investigations pointed toward a gonadal origin of testosterone production, whereas elevated LH and FSH paradoxically suggested hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. Thus, gonadal dysgenesis owing to a DSD was suspected and genetic workup initiated.

Table 2.

Laboratory values before and after gonadectomy

| Reference | Initial (basal) | ACTH test basal/stimulated | Dexamethasone test | Postoperative day 1 | Postoperative day 75 before E2 | Under E2 5 mo E2 6.25 µg/24 h | Under E2 14 mo E2 12.5 µg/24 h | Under E2 21 mo E2 25 µg/24 h | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTH (ng/L) | 7.2-63.6 | 2.1/… | 1.5 | <1.5 | 2.3 | … | … | … | |

| Cortisol (nmol/L) | 133-537 (6-10 am) *68-327 (4-8 pm) | 227/668 | 26 | 20* | 167 | … | 206 | ||

| DHEA (nmol/L) | 3.9-20 | 3.8 | 4.0/6.8 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 4.5 | 2.87 |

| DHEA-S (µmol/L) | 0.92-7.6 | 1.32 | 1.02/… | 0.85 | 0.83 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.85 | 1.22 |

| Androstenedione (nmol/L) | <8.4 | <1.05 | <1.05/1.12 | <1.05 | … | <1.05 | <1.05 | <1.05 | <1.05 |

| Free testosterone (pmol/L) | 1.06-4.88 | 23.3 | 14.8/12.5 | 12.6 | 0.75 | 2.34 | 2.16 | 1.36 | 4.35 |

| 11-desoxycortisol (nmol/L) | <12 | 7.9 | …/18.0 | 2.5 | … | 5.3 | 7.0 | 4.6 | 0.70 |

| 17-OH-progesterone (nmol/L) | <6 | 1.9 | 2.1/6.9 | 1.7 | … | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

| LH (U/L) | 12.5 | 13.1/- | 15.3 | 19.6 | 26 | 23.5 | 19.1 | 27.9 | |

| FSH (U/L) | 37.5 | 39.4/- | 42 | 44.1 | 79.6 | 72.4 | 67.4 | 70.8 | |

| Estradiol (pmol/L) | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 | 208 | 65 |

Numbers in bold mark values outside the reference range.

Abbreviations: DHEA-S, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; E2, estradiol.

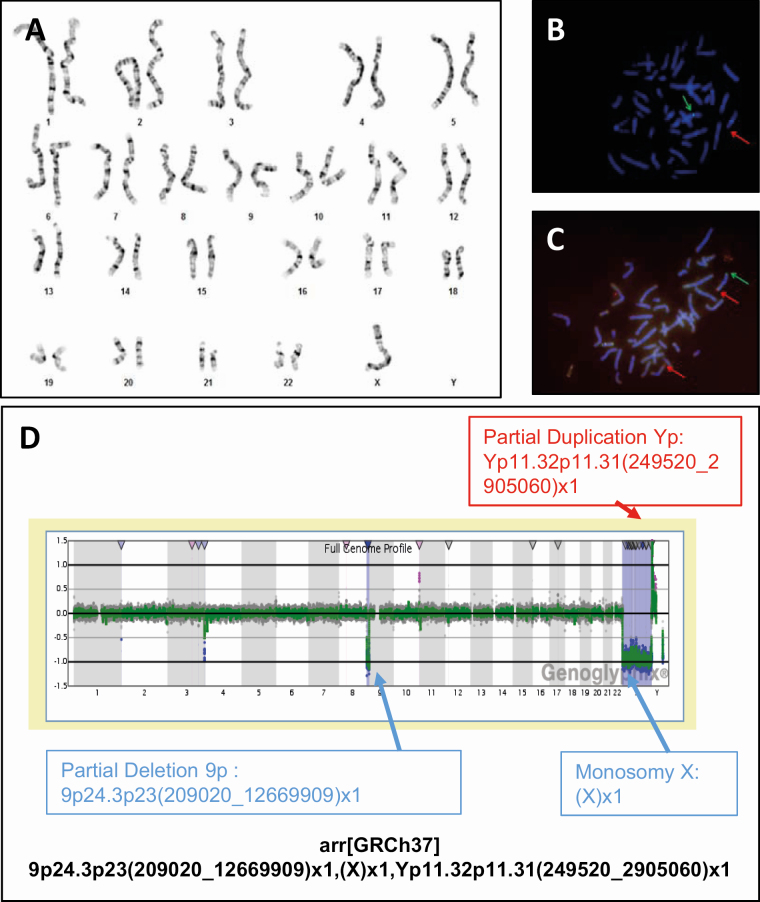

Initially, conventional chromosomal analysis of 30 lymphocytes (180 mitosis) revealed a 45,X karyotype compatible with TS (Fig. 2A). Further genetic examinations in search of “hidden” Y-chromosome material included fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) and array comparative genomic hybridization (180 K) analyses (Fig. 2B–D). They uncovered a terminal heterozygous deletion of 9p24.3p23 and the presence of Yp11.32p11.31, with the karyotype described according to the International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (2016) as follows: 45,X.ish der (9)t(Y;9)(305J7-T7,SRY+).arr[GRCh37]9p24.3p23(209020_12669909)x1,(X)x1,Yp11.32p11.31(249520_2905060)x1. Ectopic presence of Sex Determining Region on Y (SRY) has been shown sufficient to induce testis development (34). However, the terminal heterozygous deletion of 9p24.3p23 resulted in partial monosomy of 9p (~12.46 Mb) with absence of 49 genes including the pro-testis gene Doublesex and Mab-3 Related Transcription Factor 1 (DMRT1), and explaining the female phenotype in our patient (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Genetic analyses performed in the girl presented in the case vignette. (A) Karyotype 45,X. (B-C) FISH analysis confirmed the presence of SRY and showed a suspicious hybridization pattern. (B) FISH analysis with LSI SRY(red)/CEPX(green) probes showing an unusual hybridization pattern. LSI SRY-signal on chromosome 9pter. (C) FISH analysis with SubTel-9p/9q-probe (9pter(green)/9qter(red)). No SubTel 9p signal present on the derivative chromosome 9, only a red signal, no green signal. (D) Array-CGH analysis. Full genome profile from Genoglyphix, CGX, 180K, PerkinElmer. Abbreviation: FISH, fluorescent in situ hybridization.

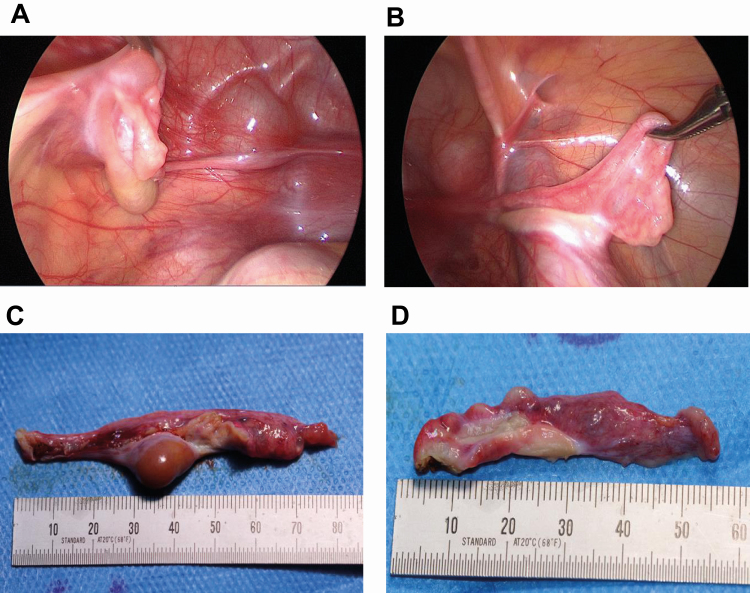

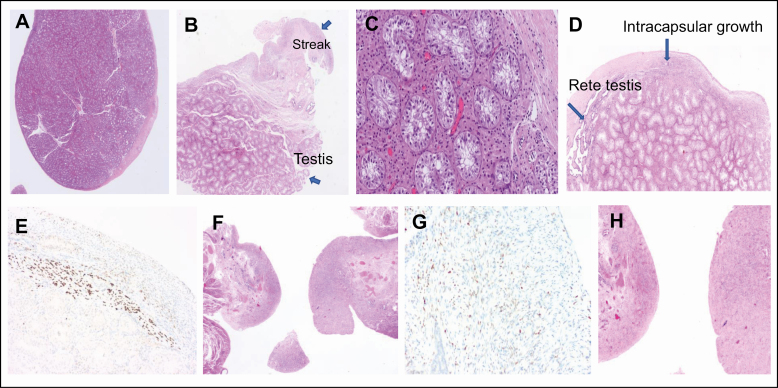

Given that these results were consistent with a complex form of gonadal dysgenesis with functionally active testicular tissue, the patient underwent laparoscopy. Macroscopically atypical gonads were found on both sides (Fig. 3). Gonadectomy was performed to avoid further virilization and malignant degeneration because there is a high risk for germ cell cancer (GCC), arising from surviving pluripotent germ cells in dysgenetic gonads harboring Y chromosomal material (35). Morphological and immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 4) revealed a left gonad mostly differentiated as testis and characterized by Sertoli cell only tubules, extensive Leydig cell hyperplasia, and discrete signs of dysgenesis (intracapsular growth of tubules, ovarian-type stroma) at the gonadal periphery, as well as a small area of streak gonadal tissue. The right gonad was composed of streak tissue only with limited and scattered granulosa cells. Follicles or isolated germ cells were not detected by specialized immunohistochemical staining. There were no signs of in situ or invasive GCC, as indicated by negative SALL4 and OCT3/4 staining (not shown).

Figure 3.

Pictures of gonads of the described patient at timepoint of laparoscopic gonadectomy. (A) Laparoscopic view on the in situ dysgenetic gonad on the left. (B) Laparoscopic view on the streak gonad on the right. (C) Left gonad after removal. (D) Right gonad after removal.

Figure 4.

Histologic workup of the dysgenetic gonads. (A-E) Left gonad. (A-B) Left gonad predominantly developed as testis, with a smaller zone of streak tissue at the periphery. (C) Detailed analysis shows Sertoli cell-only tubules and diffuse intertubular Leydig cell hyperplasia. (D) The testicular periphery reveals rete testis and a more dysgenetic area with intracapsular growth of testis tubules in a background of ovarian-type stroma. (E) The latter finding is confirmed by the presence of scattered FOXL2 positive (brown) granulosa cells. (F-H) Right streak gonad. (F) Follicles or isolated germ cells are not detected. (G) The stromal background contains some dispersed FOXL2 positive (brown) granulosa cells confirming the overall female differentiation of this gonad. (H) Tube with fimbrial funnel on the right.

On follow-up, after removal of the gonads, testosterone values normalized (Table 2) and clitoromegaly reduced. The patient received psychosexual care and identified herself clearly in the female gender. Given the high LH/FSH values suggesting pubertal activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, E2 replacement therapy was started 2 months after gonadectomy to enable the development of secondary female sexual characteristics and to promote normal bone mass acquisition. The patient’s compliance with transdermal E2 patch treatment was initially rather poor, but improved under psychological guidance, so that E2 and FSH levels normalized under stepwise dose adjustment (Table 2).

Discussion

We describe a girl who presented with spontaneous virilization at puberty. High serum testosterone, LH and FSH, and a complex chromosomal rearrangement, including presence of Y chromosomal material initially suggested a diagnosis of TS with mosaicism for a second cell line. A normal or partly deleted Y chromosome can be found in 6% to 11% of women with TS. However, the girl lacked clinical features associated with classic TS, such as typical facial characteristics, short stature, and cardiac or renal anomalies. Instead, the unique chromosomal rearrangement, resulting in the combined presence of the testis-inducing gene SRY with absence of the pro-testis gene DMRT1 on 9p had led to partial gonadal (testicular) dysgenesis, manifest as unilateral testis development with extensive Leydig cell hyperplasia resulting in high androgen production at puberty. The molecular genetic diagnosis and pathological findings are in line with hormonal results (ie, hypergonadotropic hypogonadism and testosterone levels well above the female reference range), but cannot explain why virilization did not occur already prenatally.

Early diagnosis and appropriate management of partial gonadal dysgenesis is crucial because of a strongly increased (up to 50%) risk of gonadoblastoma and invasive GCC development (36, 37) Therefore, a systematic search for hidden Y-chromosome material should be performed in all TS girls with signs of virilization or with an unidentifiable marker chromosome identified by classical cytogenetic analysis (38-40).

Gonadal (testicular) dysgenesis with increased risk of gonadoblastoma can also be associated with partial or complete deletion of distal chromosome 9 (41). The recurrent distal 9p microdeletion syndrome has a prevalence of <1/1,000,000 and is characterized by dysmorphic features such as trigonocephaly, long philtrum, psychomotor retardation, speech problems, and atypical genitalia (42). The phenotype shows variable expressivity and is related to the size of the deletion, with cases of isolated 46,XY sex reversal without other dysmorphic features (43). Within this region, the strongest candidate for disrupted gonadal development is the DMRT1 gene, mapping to 9p24.3 (44). DMRT1 is a transcription factor expressed by both Sertoli and germ cells. It is critical for testis determination, differentiation, and maintenance. DMRT1 haploinsufficiency is associated with abnormal testicular development, leading to germ cell loss and reduced or absent virilization of external genitalia (45-47). The particular genotype of sex reversal resulting from loss of DMRT1 is extremely rare, with only a few cases reported. Marsudi et al (45) reported on a 12-year-old female with short stature and cognitive impairment, mimicking TS. Genetic analysis revealed loss of the DMRT1 gene in a mosaic 45,XY,-9[8]/46,XY,r (9)[29]/47,XY,+idic r (9)×2[1]/46,XY,idic r (9)[1]/46,XY[1] karyotype. Further research is required to better understand the exact mechanism that underlies sex reversal caused by DMRT1 haploinsufficiency (48), as well as the delayed onset of virilization in our case.

Conclusion

Virilization at puberty is more complex than routinely thought. All efforts should be taken to identify the underlying cause as a malignant tumor may be found and ongoing virilization may result in irreversible bodily changes. Underlying ovarian or adrenal tumors should be excluded by imaging studies. Karyotyping and a thorough search for Y chromosomal material by quantitative PCR or FISH are essential components of the genetic evaluation. If Y material is found, prophylactic gonadectomy of dysgenetic gonads may be advised to prevent gonadoblastoma and invasive tumor development. The described case report highlights the importance of repeated and expanded biochemical and genetic workup to solve unusual cases. Complex genetic rearrangements can cause unique, unexpected phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient and her family for allowing her case history to be published.

Financial Support: None.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 17OHP

17-hydroxyprogesterone

- AMH

anti-Müllerian hormone

- CAH

congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- DHEA-S

dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- DMRT1

Doublesex and Mab-3 Related Transcription factor 1

- DSD

disorder/difference of sex development

- E2

estradiol

- FISH

fluorescent in situ hybridization

- GCC

germ cell cancer

- GCT

germ cell tumor

- POR

cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase; SDS, standard deviation score

- TS

Turner syndrome

Additional Information

Disclosures: None.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.

References

- 1. Rosenfield RL. The diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):1154-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rich AL, Phipps LM, Tiwari S, Rudraraju H, Dokpesi PO. The increasing prevalence in intersex variation from toxicological dysregulation in fetal reproductive tissue differentiation and development by endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Environ Health Insights. 2016;10:163-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller WL, Fluck CE, Breault DT, Feldman BJ. The adrenal cortex and its disorders. In: Sperling M, ed. Sperling Pediatric Endocrinology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2020:425-490. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lala SV, Strubel N. Ovarian neoplasms of childhood. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49(11):1463-1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marti N, Malikova J, Galván JA, et al. Androgen production in pediatric adrenocortical tumors may occur via both the classic and/or the alternative backdoor pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;452:64-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pinto EM, Zambetti GP, Rodriguez-Galindo C. Pediatric adrenocortical tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;34(3):101448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Faure-Conter C, Orbach D, Fresneau B, et al. Disorder of sex development with germ cell tumors: which is uncovered first? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(4):e28169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schultz KAP, Harris AK, Finch M, et al. DICER1-related Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor and gynandroblastoma: clinical and genetic findings from the International Ovarian and Testicular Stromal Tumor Registry. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147(3):521-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Speiser PW, Arlt W, Auchus RJ, et al. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(11):4043-4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Speiser PW, Dupont B, Rubinstein P, Piazza A, Kastelan A, New MI. High frequency of nonclassical steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37(4):650-667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Witchel SF. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(5):520-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kurtoğlu S, Hatipoğlu N. Non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia in childhood. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2017;9(1):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pandey AV, Flück CE. NADPH P450 oxidoreductase: structure, function, and pathology of diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138(2):229-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Praveen VP, Ladjouze A, Sauter KS, et al. Novel CYP19A1 mutations extend the genotype-phenotype correlation and reveal the impact on ovarian function. J Endocr Soc. 2020;4:bvaa030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Batista RL, Mendonca BB. Integrative and analytical review of the 5-alpha-reductase type 2 deficiency worldwide. Appl Clin Genet. 2020;13:83-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee YS, Kirk JM, Stanhope RG, et al. Phenotypic variability in 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-3 deficiency and diagnostic pitfalls. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;67(1):20-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mendonca BB, Batista RL, Domenice S, et al. Steroid 5α-reductase 2 deficiency. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;163:206-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hughes IA, Davies JD, Bunch TI, Pasterski V, Mastroyannopoulou K, MacDougall J. Androgen insensitivity syndrome. Lancet. 2012;380(9851):1419-1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quigley CA, De Bellis A, Marschke KB, el-Awady MK, Wilson EM, French FS. Androgen receptor defects: historical, clinical, and molecular perspectives. Endocr Rev. 1995;16(3):271-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Piprek RP. Molecular Mechanisms of Cell Differentiation in Gonad Development. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing Switzerland; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gariépy-Assal L, Gilbert RD, Žiaugra A, Foster BJ. Management of Denys-Drash syndrome: a case series based on an international survey. Clin Nephrol Case Stud. 2018;6:36-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adachi M, Hasegawa T, Tanaka Y, Asakura Y, Hanakawa J, Muroya K. Spontaneous virilization around puberty in NR5A1-related 46,XY sex reversal: additional case and a literature review. Endocr J. 2018;65(12):1187-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tantawy S, Lin L, Akkurt I, et al. Testosterone production during puberty in two 46,XY patients with disorders of sex development and novel NR5A1 (SF-1) mutations. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167(1):125-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lizneva D, Gavrilova-Jordan L, Walker W, Azziz R. Androgen excess: investigations and management. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;37:98-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hertweck SP, Yoost JL, McClure ME, et al. Ferriman-Gallwey scores, serum androgen and mullerian inhibiting substance levels in hirstute adolescent girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25(5):300-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glintborg D, Altinok ML, Petersen KR, Ravn P. Total testosterone levels are often more than three times elevated in patients with androgen-secreting tumours. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2014204797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Terzolo M, Alì A, Osella G, et al. The value of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate measurement in the differentiation between benign and malignant adrenal masses. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;142(6):611-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller WL. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia: time to replace 17OHP with 21-deoxycortisol. Horm Res Paediatr. 2019;91(6):416-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saxena P, Pandey N. Hyperandrogenism—approach and management. Fertil Sci Res. 2019;6:16-22. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krone N, Hughes BA, Lavery GG, Stewart PM, Arlt W, Shackleton CH. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) remains a pre-eminent discovery tool in clinical steroid investigations even in the era of fast liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS). J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121(3-5):496-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kulle A, Krone N, Holterhus PM, et al. ; EU COST Action . Steroid hormone analysis in diagnosis and treatment of DSD: position paper of EU COST Action BM 1303 ‘DSDnet’. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176(5):P1-P9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Josso N, Rey RA. What does AMH tell us in pediatric disorders of sex development? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Edelsztein NY, Racine C, di Clemente N, Schteingart HF, Rey RA. Androgens downregulate anti-Müllerian hormone promoter activity in the Sertoli cell through the androgen receptor and intact steroidogenic factor 1 sites. Biol Reprod. 2018;99(6):1303-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kashimada K, Koopman P. Sry: the master switch in mammalian sex determination. Development. 2010;137(23):3921-3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cools M, Drop SL, Wolffenbuttel KP, Oosterhuis JW, Looijenga LH. Germ cell tumors in the intersex gonad: old paths, new directions, moving frontiers. Endocr Rev. 2006;27(5):468-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van der Zwan YG, Biermann K, Wolffenbuttel KP, Cools M, Looijenga LH. Gonadal maldevelopment as risk factor for germ cell cancer: towards a clinical decision model. Eur Urol. 2015;67(4):692-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cools M, Pleskacova J, Stoop H, et al. ; Mosaicism Collaborative Group . Gonadal pathology and tumor risk in relation to clinical characteristics in patients with 45,X/46,XY mosaicism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(7):E1171-E1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baer TG, Freeman CE, Cujar C, et al. Prevalence and physical distribution of SRY in the gonads of a woman with turner syndrome: phenotypic presentation, tubal formation, and malignancy risk. Horm Res Paediatr. 2017;88(3-4):291-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. de Marqui AB, da Silva-Grecco RL, Balarin MA. [Prevalence of Y-chromosome sequences and gonadoblastoma in Turner syndrome.] Rev Paul Pediatr. 2016;34(1):114-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Freriks K, Timmers HJ, Netea-Maier RT, et al. Buccal cell FISH and blood PCR-Y detect high rates of X chromosomal mosaicism and Y chromosomal derivatives in patients with Turner syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. 2013;56(9):497-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Del Rey G, Venara M, Papendieck P, et al. Association of distal deletion of the short arm of chromosome 9 with 46,XY disorder of sex development and gonadoblastoma. Biol syst Open Access. 2015;4(1):1000129. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hauge X, Raca G, Cooper S, et al. Detailed characterization of, and clinical correlations in, 10 patients with distal deletions of chromosome 9p. Genet Med. 2008;10(8):599-611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Onesimo R, Orteschi D, Scalzone M, et al. Chromosome 9p deletion syndrome and sex reversal: novel findings and redefinition of the critically deleted regions. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(9):2266-2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barbaro M, Balsamo A, Anderlid BM, et al. Characterization of deletions at 9p affecting the candidate regions for sex reversal and deletion 9p syndrome by MLPA. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(11):1439-1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Raymond CS, Murphy MW, O’Sullivan MG, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. Dmrt1, a gene related to worm and fly sexual regulators, is required for mammalian testis differentiation. Genes Dev. 2000;14(20):2587-2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhao L, Svingen T, Ng ET, Koopman P. Female-to-male sex reversal in mice caused by transgenic overexpression of Dmrt1. Development. 2015;142(6):1083-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barrionuevo FJ, Hurtado A, Kim GJ, et al. Sox9 and Sox8 protect the adult testis from male-to-female genetic reprogramming and complete degeneration. Elife 2016;5:e15635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Quinonez SC, Park JM, Rabah R, et al. 9p partial monosomy and disorders of sex development: review and postulation of a pathogenetic mechanism. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(8):1882-1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the data repositories listed in References.