Abstract

Context

Dulaglutide reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in the Researching Cardiovascular Events with a Weekly INcretin in Diabetes (REWIND) trial. Its efficacy and safety in older vs younger patients have not been explicitly analyzed.

Objective

This work aimed to assess efficacy and safety of dulaglutide vs placebo in REWIND by age subgroups (≥ 65 and < 65 years).

Methods

A post hoc subgroup analysis of REWIND was conducted at 371 sites in 24 countries. Participants included type 2 diabetes patients aged 50 years or older with established cardiovascular (CV) disease or multiple CV risk factors, and a wide range of glycemic control. Patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to dulaglutide 1.5 mg or placebo as an add-on to country-specific standard of care. Main outcomes measures included MACE (first occurrence of the composite of nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or death from CV or unknown causes).

Results

There were 5256 randomly assigned patients who were 65 years or older (mean = 71.0), and 4645 were younger than 65 years (mean = 60.7). Baseline characteristics were similar in randomized treatment groups. Dulaglutide treatment showed a similar reduction in the incidence (11% vs 13%) of MACE in older vs younger patients. The rate of permanent study drug discontinuation, incidence of all-cause mortality, hospitalizations for heart failure, severe hypoglycemia, severe renal or urinary events, and serious gastrointestinal events were similar between randomized treatment groups within each age subgroup. The incidence rate of serious cardiac conduction disorders was numerically higher in the dulaglutide group compared to placebo within each age subgroup but the difference was not statistically significant.

Conclusion

Dulaglutide had similar efficacy and safety in REWIND in patients65 years and older and those younger than 65 years.

Keywords: dulaglutide, cardiovascular, older

More than 25% of the US population age 65 years and older has type 2 diabetes (T2D) (1). Patients age 65 years and older with diabetes have higher rates of premature death, functional disability, and coexisting illnesses, such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, and stroke, than those without diabetes (2). The cardiovascular (CV) efficacy and safety of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) in people with T2D have been evaluated in CV outcome trials and are of particular interest for those age 65 and older as a potentially effective and safe treatment option, because this patient group is at greater risk of CV events and side effects from therapy.

The GLP-1 RA class has proven to be generally safe and effective at lowering blood glucose and decreasing body weight, and some agents reduce the risk of a major adverse CV event (MACE) in the general T2D population without increased risk of hypoglycemia (3-5). Dulaglutide is a once-weekly GLP-1 RA that was tested in the Researching Cardiovascular Events with a Weekly INcretin in Diabetes (REWIND) trial, which showed that it reduced the risk of MACE in adults with T2D with established CV disease or multiple CV risk factors (6, 7). In relatively small and short-term studies, dulaglutide has been found to have similar glycemic efficacy with an acceptable safety profile in T2D patients age 65 years or older compared to those younger than 65 (8).

The present post hoc analysis of REWIND evaluated the CV efficacy and safety of dulaglutide vs placebo by age subgroups (≥ 65 and < 65 years) in this larger and longer-duration, randomized controlled trial.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patients

The study design of the REWIND trial was previously published (7, 9). Briefly, patients with T2D aged 50 years or older with established CV disease, aged 55 years or older with subclinical CV disease, and aged 60 years or older with 2 or more CV risk factors were recruited between August 2011 and August 2013, from 371 sites in 24 countries. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to blinded once-weekly subcutaneous injection of either dulaglutide 1.5 mg or placebo as an add-on to standard of care therapy based on country-specific guidelines. The trial was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent, and all protocols were approved by local ethical review boards.

Outcomes

The primary objective of this post hoc analysis was to assess the efficacy differences and safety of dulaglutide vs placebo by age subgroups. Outcomes evaluated were incidence of MACE (nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or death from CV or unknown causes), all-cause mortality, and hospitalization or urgent care for heart failure. Safety outcomes included the incidence and rates of all severe hypoglycemic events, incidence of serious renal or urinary events, serious gastrointestinal (GI) events, serious cardiac conduction disorders (supraventricular tachycardia and CV conduction disorders), and permanent discontinuation of the study drug due to any reason and due to adverse events. The criteria for adjudication of all clinical events were previously reported (7).

Statistical Analysis

Time-to-event subgroup analysis for age was performed for all outcomes. For time-to-event variables, a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, in which the model included a fixed effect for treatment, subgroup, and treatment by subgroup interaction, was conducted. Treatment by age subgroup interaction P values were calculated for all outcomes. To estimate dulaglutide’s effect within each subgroup, a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed in which the model included a fixed effect for treatment, and the P value corresponding to the treatment was also reported. To compare the rates of severe hypoglycemic events, a negative binomial regression model was implemented with a fixed effect for treatment, subgroup, and treatment by subgroup interaction. To estimate dulaglutide’s effect on rates of severe hypoglycemia within each subgroup, another negative binomial regression analysis was performed in which the model included a fixed effect for treatment and the P values corresponding to the treatment were also reported. For each analysis, patients who did not experience the outcome of interest were censored at their last known follow-up date. Baseline demographic and other characteristics were summarized within each age subgroup, and continuous variables were summarized as means and SDs and categorical variables as counts and proportions.

Results

Researching Cardiovascular Events with a Weekly Incretin in Diabetes Trial Primary Results

A total of 9901 patients were randomly assigned to treatment (dulaglutide, 4949; placebo, 4952) and were followed for a median of 5.4 years. At baseline the patients’ mean age was 66.2 years with mean glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 7.3%; 46.3% were female (Table 1). Baseline characteristics were comparable among the treatment groups. As previously reported for the overall REWIND population (7), the primary MACE outcome occurred in 594 (12.0%) patients (2.4 per 100 person-years) randomly assigned to dulaglutide and 663 (13.4%) patients (2.7 per 100 person-years) randomly assigned to placebo (hazard ratio [HR] 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.99; P = .026).

Table 1.

Patient baseline characteristics and demographics

| Variable | Total (N = 9901) | Age ≥ 65 y (N = 5256) | Age < 65 y (N = 4645) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (mean ± SD) | 66.2 ± 6.5 | 71.0 ± 4.6 | 60.7 ± 3.2 | < .001 |

| Female (n, %) | 4589 (46.3) | 2453 (46.7) | 2136 (46.0) | .495 |

| White (n, %) | 7498 (75.7) | 3989 (75.9) | 3509 (75.5) | .685 |

| Duration of diabetes, y (mean ± SD) | 10.5 ± 7.2 | 11.5 ± 7.7 | 9.4 ± 6.5 | < .001 |

| HbA1c, % (mean ± SD) | 7.3 ± 1.1 | 7.3 ± 1.0 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | < .001 |

| Weight, kg (mean ± SD) | 88.7 ± 18.5 | 86.1 ± 17.4 | 91.6 ± 19.2 | < .001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 32.3 ± 5.7 | 31.6 ± 5.4 | 33.1 ± 6.0 | < .001 |

| Prior CVD (≥ 1 of the following), n (%) | 3114 (31.5) | 1598 (30.4) | 1516 (32.6) | .006 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1602 (16.2) | 797 (15.2) | 805 (17.3) | .011 |

| Prior ischemic stroke | 528 (5.3) | 262 (5.0) | 266 (5.7) | .101 |

| Prior unstable angina | 587 (5.9) | 291 (5.5) | 296 (6.4) | .210 |

| Prior revascularizationa | 1787 (18.0) | 966 (18.4) | 821 (17.7) | .363 |

| Prior hospitalization for ischemia-related eventsb | 1193 (12.0) | 612 (11.6) | 581 (12.5) | .086 |

| Prior documented MI | 922 (9.3) | 468 (8.9) | 454 (9.8) | .007 |

| Prior hypertension, n (%) | 9224 (93.2) | 4960 (94.4) | 4264 (91.8) | < .001 |

| Prior heart failure, n (%) | 853 (8.6) | 425 (8.1) | 428 (9.2) | .081 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c, MI, myocardial ischemia.

a Coronary, carotid, or peripheral.

b Unstable angina or MI on imaging, or need for percutaneous coronary intervention. Continuous variables were compared using t test if variables satisfied normality, otherwise the Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson chi-square test if the expected counts were 5 or greater in at least 80% of the cells, otherwise the Fisher exact test was performed. For categorical variables, missing or unknown values were counted as a separate category.

Baseline Characteristics and Demographics

Patient baseline characteristics by age subgroups (≥ 65 and < 65 years) are provided in Table 1. Of the 9901 patients randomly assigned, 5256 (dulaglutide, 2619; placebo, 2637) were 65 years or older and 4645 (dulaglutide, 2330; placebo, 2315) were younger than 65. Patients 65 years or older had a mean age of 71.0 years, HbA1c 7.3%, body weight 86.1 kg, and duration of diabetes of 11.5 years. Those younger than 65 had a mean age of 60.7 years, HbA1c of 7.4%, body weight of 91.6 kg, and duration of diabetes of 9.4 years. As expected, age, duration of diabetes, body weight, and body mass index were significantly different between age subgroups (P < .001). In addition, significant differences were noted for HbA1c (P < .001), prior CV disease (P = .006), and prior hypertension (P < .001).

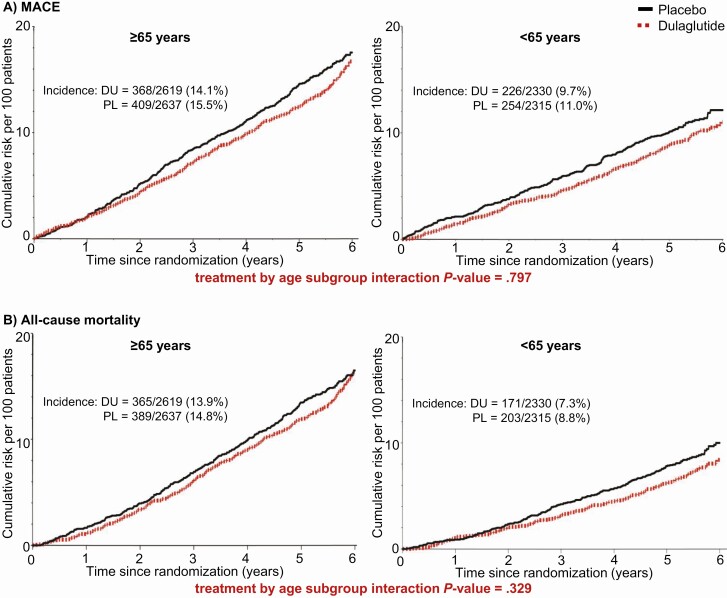

Cardiovascular Outcomes

For participants aged 65 years or older, the primary composite MACE outcome occurred in 368 of 2619 (14.1%) patients randomly assigned to dulaglutide and 409 of 2637 (15.5%) patients randomly assigned to placebo (HR 0.89; 95% CI, 0.78-1.03). For participants younger than 65, the primary composite outcome of MACE occurred in 226 of 2330 (9.7%) of those randomly assigned to dulaglutide and 254 of 2315 (11.0%) of those randomly assigned to placebo (HR 0.87; 95% CI, 0.72-1.04) (Fig. 1A). There was no evidence of a differential dulaglutide treatment effect between the age subgroups (Pinteraction = .797).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of cardiovascular outcomes. DU, dulaglutide; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, composite end point of nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, or death from cardiovascular or unknown causes; PL, placebo.

The incidence of all-cause mortality for participants aged 65 or older was 365 of 2619 (13.9%) for those randomly assigned to dulaglutide and 389 of 2637 (14.8%) for patients randomly assigned to placebo (HR 0.94; 95% CI, 0.81-1.08) (Fig. 1B). For participants younger than 65, all-cause mortality was 171 of 2330 (7.3%) for those randomly assigned to dulaglutide and 203 of 2315 (8.8%) for patients randomly assigned to placebo (HR 0.83; 95% CI, 0.6801.01) (Fig. 1B). No evidence of interaction by age was seen (Pinteraction = .329).

The incidence of hospitalization or urgent care for heart failure also did not differ between treatment groups within age subgroups (Table 2); and there was no evidence of interaction by age (Pinteraction = .636).

Table 2.

Cumulative incidence of hospitalization or urgent care due to heart failure, all severe hypoglycemic events, and discontinuation of study drug

| Age ≥ 65 y | Age < 65 y | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DU (N = 2619) | PL (N = 2637) | HR or RR (95% CI) | DU (N = 2330) | PL (N = 2315) | HR or RR (95% CI) | Interaction P | |

| Hospitalization or urgent care due to heart failure | |||||||

| Patients with events, n (%) | 138 (5.3) | 152 (5.8) | HR: 0.90 (0.72-1.14) | 75 (3.2) | 74 (3.2) | HR: 0.99 (0.72-1.37) | .636 |

| All severe hypoglycemic events | |||||||

| Patients with events, n (%) | 46 (1.8) | 49 (1.9) | HR: 0.94 (0.63-1.41) | 18 (0.8) | 25 (1.1) | HR: 0.71 (0.39-1.30) | .443 |

| All events | 57 | 53 | RR: 1.08 (0.68-1.72) | 20 | 29 | RR: 0.69 (0.36-1.31) | .259 |

| Discontinuation of study drug | |||||||

| Discontinuation due to any reason, n (%) | 985 (37.6) | 1013 (38.4) | HR: 0.99 (0.91-1.09) | 632 (27.1) | 681 (29.4) | HR: 0.91 (0.82-1.01) | .209 |

| Discontinuation due to adverse event, n (%) | 289 (11.0) | 200 (7.6) | HR: 1.50 (1.25-1.79) | 162 (7.0) | 110 (4.8) | HR: 1.47 (1.16-1.88) | .921 |

Abbreviations: DU, dulaglutide; HR, hazard ratio; PL, placebo; RR, rate ratio.

Safety Outcomes

The incidence of severe hypoglycemia among participants aged 65 or older was 46 of 2619 (1.8%) for those randomly assigned to dulaglutide and 49 of 2637 (1.9%) for patients randomly assigned to placebo (HR 0.94; 95% CI, 0.63-1.41) (see Table 2). For participants younger than 65, the corresponding numbers were 18 of 2330 (0.8%) for those randomly assigned to dulaglutide and 25 of 2315 (1.1%) for patients randomly assigned to placebo (HR 0.71; 95% CI, 0.39-1.30) (see Table 2). No interaction by age was observed (Pinteraction = .443) (Table 2). There was also no evidence that the effect on the total number of severe hypoglycemia events differed by age subgroups (Pinteraction = .259) (see Table 2).

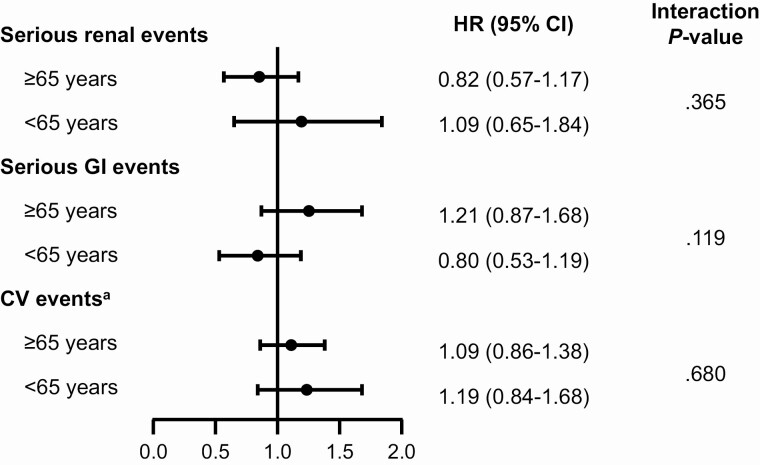

There was no evidence of differences in treatment effect across age subgroups for renal or urinary events, serious GI events, or serious cardiac conduction disorders, with nonsignificant tests for interaction (Pinteraction = .365, .119, and .680, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Analysis of serious renal events, serious gastrointestinal (GI) events, and serious cardiac conduction disorders. aPatients age 65 years or older: dulaglutide, 2619; placebo, 2637; and patients younger than 65 years: dulaglutide, 2330; placebo, 2315. bSupraventricular tachycardia or cardiovascular (CV) conduction disorders. HR, hazard ratio.

For participants aged 65 or older, 985 of 2619 (37.6%) patients randomly assigned to dulaglutide discontinued the study drug; 289 (11.0%) discontinued because of an adverse event (see Table 2). Of the patients randomly assigned to placebo, 1013 of 2637 (29.4%) discontinued the study drug; 200 (7.6%) discontinued because of an adverse event (see Table 2). For participants younger than 65, 632 of 2330 (27.1%) randomly assigned to dulaglutide discontinued the study drug, and 162 (7.0%) discontinued because of an adverse event (see Table 2). Of the patients randomly assigned to placebo, 681 of 2315 (29.4%) discontinued the study drug, and 110 (4.8%) discontinued the study drug because of an adverse event (see Table 2). Interactions by age were not significant for any study drug discontinuation (Pinteraction = .209) or discontinuation because of an adverse event (Pinteraction = .921).

Discussion

In this REWIND post hoc analysis, no difference in treatment effect between age subgroups was observed for the incidence of MACE. As expected, the CV event rate was higher in older vs younger patients and this was consistent both for the dulaglutide- and placebo-treated patients. A similar pattern was observed for all-cause mortality, hospitalization or urgent care for heart failure, severe hypoglycemia, severe renal or urinary events, serious GI events, and serious cardiac conduction disorders. Overall, adverse events and study drug discontinuations secondary to adverse events were more frequent in older vs younger patients, which was consistent both for the dulaglutide- and placebo-treated patients, and there was no evidence of a differential dulaglutide effect on discontinuation.

The large proportion of people with T2D who are age 65 or older has received considerable attention in guideline statements. Current standards of care for such patients recommend medication classes with a low risk of hypoglycemia, avoidance of polypharmacy when possible, and consideration of costs and other factors that may contribute to nonadherence (2). Treatment options may be limited in older populations with multiple comorbidities that may restrict use of some medications. For example, metformin, which is commonly considered the first-line treatment for T2D, is contraindicated in patients with advanced renal decline and should be used with caution in individuals with impaired hepatic function or congestive heart failure (2, 10). In addition, the CV benefit of this agent has not been conclusively proven. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs have demonstrated CV benefit and are recommended treatment options for patients with T2D and CV disease (10-12). However, SGLT2 inhibitors increase the risk of urogenital infections and dehydration, and should be used with caution in older adults also at high risk of such infections or during intercurrent illnesses (13, 14). Finally, GLP-1 RAs may not be optimal for older adults in whom unwanted weight loss may be difficult to reverse given its refractory GI adverse events (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea).

Safety and efficacy of dulaglutide were previously reported using data from 6 phase 3 clinical trials with dulaglutide, including 4213 patients younger than 65 and 958 older than 65 (8). No difference between age subgroups in the frequency of hypoglycemia, treatment-emergent adverse events, or specifically GI events were observed accompanying the use of dulaglutide, but this earlier analysis did not include patients assigned to placebo (8). The present analysis, including data from a larger number of older patients in the REWIND trial, not only confirmed the previous report of no greater risks for older individuals, but also showed an equivalent reduction in incidence of MACE for the older subgroup compared with placebo.

Studies of other GLP-1 RAs in older populations with T2D have generally demonstrated similar efficacy and safety as in younger populations (8, 15-17). The results from the current post hoc analysis of data from REWIND are consistent with other analyses of GLP-1 RA CV outcome trials (18-20). These analyses have shown no evidence of differences in effects on MACE, all-cause mortality and hospitalizations for heart failure, and no differences in GI events among age subgroups (18-20).

Strengths of this analysis include the long duration of the REWIND trial, and its large enrolled population that is quite representative of the general population of T2D patients seen in clinical practice, including a large proportion of older individuals. Limitations of this study include the exploratory nature of the post hoc analysis, which should be interpreted with appropriate caution.

In summary, these results suggest that once-weekly dulaglutide reduces the incidence of MACE and other CV outcomes without an increased risk of hypoglycemia or GI adverse events in all patients regardless of age subgroup. Dulaglutide can be considered a safe and effective treatment option for use in older adults.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants, without whom this study and these analyses would not have been possible. We also thank the many investigators from 371 sites in 24 countries who worked diligently to help ensure REWIND was run to the highest possible standards.

Financial Support: This work was supported by Eli Lilly and Company.

Clinical Trial Information: Clinical trials.gov ID: NCT01394952 (registered July 15, 2011).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CV

cardiovascular

- GI

gastrointestinal

- GLP-1 RAs

glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin A1c

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular event

- REWIND trial

Researching Cardiovascular Events with a Weekly INcretin in Diabetes

- SGLT2

sodium-glucose cotransporter 2

- T2D

type 2 diabetes.

Additional Information

Disclosures: M.C.R. reports grants to his institution from Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Novo Nordisk; honoraria for consulting from Adocia, DalCor, GlaxoSmithKline, and Theracos; and honoraria for speaking from Sanofi. H.C.G. holds the McMaster-Sanofi Population Health Institute Chair in Diabetes Research & Care; reports grants to his institution from Sanofi, Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Merck, and Novo Nordisk; honoraria for consulting from Sanofi, Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Kowa; and honoraria for speaking from Eli Lilly, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim. D.X. reports grants from Cadila, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Aventis, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, the UK Medical Research Council, and the Wellcome Trust. W.C.C. has received institutional grant funding from Eli Lilly. L.A.L. reports grants to his institution from and has provided CME on behalf of and/or has acted as an advisor to AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Lexicon, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Servier. P.J.R. has nothing to disclose. C.M.A., S.R., O.J.V., M.K., and M.L. are employees of Eli Lilly and own stock in the company. E.F. has acted as an advisor to AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Polfa Tarchomin, and reports honoraria for speaking from AstraZeneca, Bioton, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Polfa Tarchomin, Sanofi, and Servie.

Data Availability

Some or all data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Andes LJ, Li Y, Srinivasan M, Benoit SR, Gregg E, Rolka DB. Diabetes prevalence and incidence among Medicare beneficiaries—United States, 2001-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(43):961-966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Diabetes Association. 12. Older adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S152-S62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Giugliano D, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Longo M, Chiodini P, Esposito K. GLP-1 receptor agonists for prevention of cardiorenal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an updated meta-analysis including the REWIND and PIONEER 6 trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(11):2576-2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nolen-Doerr E, Stockman MC, Rizo I. Mechanism of glucagon-like peptide 1 improvements in type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 2019;8(3):284-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Ellis SL. GLP-1 receptor agonists: a review of head-to-head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2015;6(1):19-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Trulicity US Prescribing Information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2020. http://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-uspi.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. ; REWIND Investigators . Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):121-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boustani MA, Pittman I IV, Yu M, Thieu VT, Varnado OJ, Juneja R. Similar efficacy and safety of once-weekly dulaglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes aged ≥ 65 and < 65 years. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(8):820-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. ; REWIND Trial Investigators . Design and baseline characteristics of participants in the Researching cardiovascular Events with a Weekly INcretin in Diabetes (REWIND) trial on the cardiovascular effects of dulaglutide. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(1):42-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1): S98-S110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. American Diabetes Association. 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S111-S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1577-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kalra S. Sodium glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors: a review of their basic and clinical pharmacology. Diabetes Ther. 2014;5(2):355-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marín-Peñalver JJ, Martín-Timón I, Sevillano-Collantes C, del Cañizo-Gómez FJ. Update on the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. World J Diabetes. 2016;7(17):354-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pencek R, Blickensderfer A, Li Y, Brunell SC, Chen S. Exenatide once weekly for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: effectiveness and tolerability in patient subpopulations. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(11):1021-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Raccah D, Miossec P, Esposito V, Niemoeller E, Cho M, Gerich J. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide in elderly (≥ 65 years old) and very elderly (≥ 75 years old) patients with type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the GetGoal phase III programme. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2015;31(2):204-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Warren M, Chaykin L, Trachtenbarg D, Nayak G, Wijayasinghe N, Cariou B. Semaglutide as a therapeutic option for elderly patients with type 2 diabetes: pooled analysis of the SUSTAIN 1-5 trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(9):2291-2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilbert MP, Bain SC, Franek E, et al. ; LEADER Publication Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Effect of liraglutide on cardiovascular outcomes in elderly patients: a post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(6):423-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leiter LA, Bain SC, Hramiak I, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with once-weekly semaglutide in subjects with type 2 diabetes: a post hoc analysis of gender, age, and baseline CV risk profile in the SUSTAIN 6 trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mentz RJ, Bethel MA, Merrill P, et al. ; EXSCEL Study Group . Effect of once-weekly exenatide on clinical outcomes according to baseline risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: insights from the EXSCEL trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(19):e009304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.