Abstract

Background

Persons living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH) constitute a vulnerable population in view of their impaired immune status. At this time, the full interaction between HIV and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been incompletely described.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to explore the impact of HIV and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection on mortality.

Method

We systematically searched PubMed and the Europe PMC databases up to 19 January 2021, using specific keywords related to our aims. All published articles on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and HIV were retrieved. The quality of the studies was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for observational studies. Statistical analysis was performed with Review Manager version 5.4 and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3 software.

Results

A total of 28 studies including 18 255 040 COVID-19 patients were assessed in this meta-analysis. Overall, HIV was associated with a higher mortality from COVID-19 on random-effects modelling {odds ratio [OR] = 1.19 [95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.01–1.39], p = 0.03; I2 = 72%}. Meta-regression confirmed that this association was not influenced by age (p = 0.208), CD4 cell count (p = 0.353) or the presence of antiretroviral therapy (ART) (p = 0.647). Further subgroup analysis indicated that the association was only statistically significant in studies from Africa (OR = 1.13, p = 0.004) and the United States (OR = 1.30, p = 0.006).

Conclusion

Whilst all persons ought to receive a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, PLWH should be prioritised to minimise the risk of death because of COVID-19. The presence of HIV should be regarded as an important risk factor for future risk stratification of COVID-19.

Keywords: coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, HIV, AIDS

Introduction

At the end of December 2019, the first cases of a newly discovered acute respiratory illness named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) were reported in Wuhan, China.1 By January 2021, >88.3 million infections and 1.9 million deaths worldwide had been reported.2 The COVID-19 disease has various clinical manifestations, ranging from mild symptoms such as fever, cough and anosmia to life-threatening conditions including shock, respiratory failure, arrhythmia, overwhelming sepsis and neurological impairment.3,4 Meta-analyses have identified several comorbidities,5,6,7,8,9 medicines10,11 and abnormal laboratory test results12,13 associated with a poor outcome. Persons living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH) are an at-risk population in view of their impaired immunity. This impairment increases susceptibility to tuberculosis, opportunistic infections and cancer.14 In 2019, an estimated 38 million people globally were living with HIV; 1.7 million new (incident) infections and 690 000 deaths were reported that year.15 Human immunodeficiency virus–infected individuals with immune suppression (impaired T-cell and humoral responses), unsuppressed HIV RNA viral load (untreated or with treatment failure) and comorbid disease (diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular and renal impairment) may be at risk of the life-threatening forms of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.16 However, this hypothesis requires additional evidence. Results from observational studies have been conflicting.17,18,19,20 This meta-analysis aims to explore the impact of HIV and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection on the mortality outcomes of COVID-19 based on available observational studies.

Research methods and design

Eligibility criteria

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis of published observational studies. Articles were selected if they fulfilled the following entry criteria: compliance with the PICO framework, namely P = confirmed positive COVID-19 patients, I = patients living with HIV, C = HIV-uninfected persons and O = mortality in COVID-19-confirmed patients not attributable to unrelated conditions such as trauma. The studies included were randomised clinical trials, cohort, case-cohort and cross-over design, and the full-text paper had to be available and to have been published. Excluded studies included non-original research such as review articles, letters or commentaries; case reports; studies in a language other than English; studies of children and youths <18 years of age and pregnant women.

Search strategy and study selection

A systematic search of PubMed and Europe PMC provided many papers. Additional articles were located by analysing the papers cited by the authors of the identified studies. The search terms included ‘HIV’ or ‘human immunodeficiency virus’ or ‘immunocompromised’ or ‘immune-deficient’ or ‘AIDS’ or ‘acquired immunodeficiency syndrome’ and ‘SARS-CoV-2’ or ‘coronavirus disease 2019’ or ‘COVID-19’ or ‘novel coronavirus’ or ‘nCoV’. The selected time-range included 01 December 2019 to 19 January 2021. Only English-language articles were evaluated. Details of the search strategy are listed in Table 1. Studies of HIV and SARS-CoV-2 co-infection with a valid definition of ‘mortality’ were included. The search strategy is presented in the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) diagram.

TABLE 1.

Literature search strategy.

| Database | Keywords | No. of results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“hiv”[MeSH Terms] OR “hiv”[All Fields]) OR (“acquired immunodeficiency syndrome”[MeSH Terms] OR (“acquired”[All Fields] AND “immunodeficiency”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields]) OR “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome”[All Fields] OR “aids”[All Fields]) AND (“COVID-19”[All Fields] OR “COVID-19”[MeSH Terms] OR “COVID-19 Vaccines”[All Fields] OR “COVID-19 Vaccines”[MeSH Terms] OR “COVID-19 serotherapy”[All Fields] OR “COVID-19 Nucleic Acid Testing”[All Fields] OR “covid-19 nucleic acid testing”[MeSH Terms] OR “COVID-19 Serological Testing”[All Fields] OR “covid-19 serological testing”[MeSH Terms] OR “COVID-19 Testing”[All Fields] OR “covid-19 testing”[MeSH Terms] OR “SARS-CoV-2”[All Fields] OR “sars-cov-2”[MeSH Terms] OR “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2”[All Fields] OR “NCOV”[All Fields] OR “2019 NCOV”[All Fields] OR ((“coronavirus”[MeSH Terms] OR “coronavirus”[All Fields] OR “COV”[All Fields]) AND 2019/11/01[PubDate] : 3000/12/31[PubDate])) | 1626 |

| Europe PMC | “HIV” OR “human immunodeficiency virus” OR “immunocompromised” OR “immunodeficient” OR “AIDS” OR “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome” AND “SARS-CoV-2” OR “coronavirus disease 2019” OR “COVID-19” | 9107 |

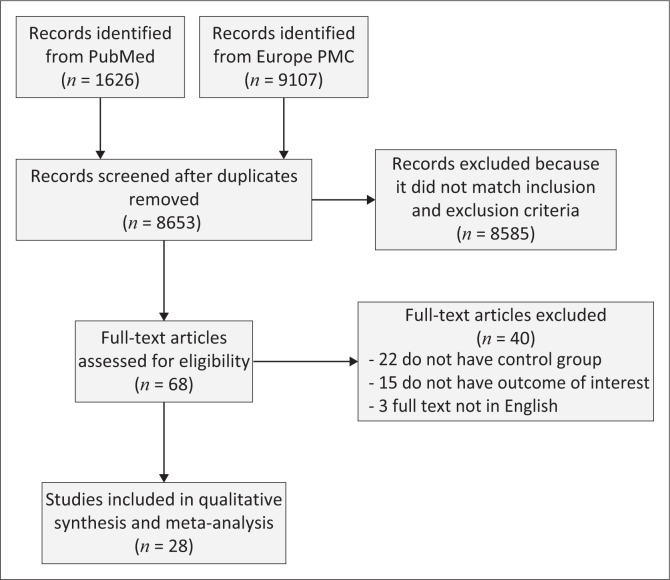

The initial investigation located 10 733 studies. After the removal of duplicates, 8653 records remained. A further 8585 studies were excluded after screening of the titles and abstracts failed to match with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of the 68 full-text articles evaluated for eligibility, 22 that lacked control or comparator groups were excluded, and 15 more were excluded because they lacked outcomes pertinent to our study. Three articles that were not in the English language were rejected. The final meta-analysis included 28 observational studies21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44 that reported on 18 255 040 COVID-19-infected persons, of whom 48 703 were co-infected with both HIV and SARS-CoV-2 (see Figure 1). Of the included articles, 25 were retrospective and 3 were prospective (see Table 2).

FIGURE1.

PRISMA diagram of the detailed process of selection of studies for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Sample size | Design | Median age, yr (IQR) | Male |

Black ethnicity |

No. of HIV/AIDS patients: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | Total |

CD4 cell counts <200 cells/μL |

Receiving ART |

|||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||||||||

| Berenguer J et al.21 2020 (Spain) | 4035 | Retrospective cohort | 70 (56–80) | 2433 | 61 | 12/3915 | 0.3 | 26/3962 | 0.7 | N/A | - | 21/25 | 84 |

| Bhaskaran K et al.17 2020 (England) | 17 282 905 | Retrospective cohort | 48 (40–55) | 8 632 666 | 49.9 | 340 114/17 282 905 | 1.9 | 27 480/17 282 905 | 0.1 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Boulle A et al.22 2020 (South Africa) | 22 308 | Retrospective cohort | 52 (37–63) | 7052 | 31.6 | N/A | - | 3978/22 308 | 17.8 | 70/199 | 35 | 56/70 | 80 |

| Braunstein SL et al.23 2020 (USA) | 204 422 | Retrospective cohort | 52 (47–65) | 105 024 | 51.3 | 32 491/204 422 | 15.8 | 2410/204 422 | 1.1 | 379/1419 | 26.7 | 1288/1447 | 89 |

| Cabello A et al.24 2020 (Spain) | 7061 | Retrospective cohort | 46 (37–56) | 6277 | 88.9 | N/A | - | 63/7061 | 0.9 | 17/63 | 26.7 | 61/63 | 96.8 |

| Chilimuri S et al.25 2020 (USA) | 375 | Retrospective cohort | 63 (52–72) | 236 | 63 | 93/375 | 25 | 22/375 | 6 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Docherty AB et al.26 2020 (England) | 20 133 | Prospective cohort | 72.9 (58–82) | 12 068 | 59.9 | N/A | - | 83/20 133 | 0.5 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| El-Solh AA et al.27 2020 (USA) | 7816 | Retrospective cohort | 69 (60–74) | 7387 | 94.5 | 3264/7816 | 41.7 | 144/7816 | 1.8 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Garibaldi BT et al.28 2020 (USA) | 832 | Retrospective cohort | 63 (49–75) | 443 | 53.2 | 336/832 | 41 | 9/832 | 1 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Geretti AM et al.18 2020 (England) | 47 592 | Prospective cohort | 74 (60–84) | 27 248 | 57.2 | 1523/42 320 | 3.5 | 122/47 592 | 0.2 | N/A | - | 112/122 | 91.8 |

| Gudipati S et al.19 2020 (USA) | 65 271 | Prospective cohort | 52 (45–67) | 30 677 | 47 | 20 886/65 271 | 32 | 278/65 271 | 0.4 | 2/14 | 14.2 | 13/14 | 92.8 |

| Hadi YB et al.20 2020 (USA) | 50 167 | Retrospective cohort | 48 (29–67) | 22 636 | 45.1 | 12 729/50 167 | 25.3 | 404/50 167 | 0.8 | N/A | - | 284/404 | 70.2 |

| Harrison SL et al.29 2020 (USA) | 31 461 | Retrospective cohort | 50 (35–63) | 14 306 | 45.5 | 8758/31 461 | 27.8 | 226/31 461 | 0.7 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Hsu HE et al.30 2020 (USA) | 2729 | Retrospective cohort | 54 (40–68) | 1312 | 48.1 | 1218/2729 | 44.6 | 732/2729 | 2.7 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Huang J et al.31 2020 (China) | 50 333 | Retrospective cohort | 37 (29–52) | 5427 | 90.4 | N/A | - | 6001/50 333 | 11.9 | 613/5897 | 10.3 | 5527/6001 | 92.1 |

| Jassat W et al.32 2020 (South Africa) | 41 877 | Retrospective cohort | 52 (40–63) | 19 122 | 45.6 | 13 444/19 777 | 68 | 3077/35 550 | 8.7 | 401/1390 | 28.8 | 1271/1278 | 99.5 |

| Kabarriti R et al.33 2020 (USA) | 5902 | Retrospective cohort | 58 (44–71) | 2768 | 46.9 | 1935/5902 | 32.7 | 92 | 1.6 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Karmen-Tuohy S et al.34 2020 (USA) | 63 | Retrospective cohort | 60 (41–81) | 57 | 90.4 | 9 | 14.2 | 21/63 | 33.3 | 6/19 | 31.5 | 21/21 | 100 |

| Kim D et al.35 2020 (USA) | 867 | Retrospective cohort | 57 (46–71) | 473 | 54.7 | 267/867 | 30.8 | 24/867 | 2.8 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Lee SG et al.36 2020 (Korea) | 7339 | Retrospective cohort | 47 (28–66) | 2970 | 40.1 | N/A | - | 4/7339 | 0.1 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Maciel EL et al.37 2020 (Brazil) | 440 | Retrospective cohort | 53 (42–68) | 240 | 57.1 | 158/279 | 56.6 | 4/440 | 1 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Marcello RK et al.38 2020 (USA) | 13 442 | Retrospective cohort | 52 (39–64) | 7481 | 56 | 3518/13 442 | 26.1 | 159/13 442 | 2 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Miyashita H et al.39 2020 (USA) | 8912 | Retrospective cohort | 55 (42–69) | 4922 | 55.2 | N/A | - | 161/8912 | 1.8 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Ombajo LA et al.40 2020 (Kenya) | 787 | Retrospective cohort | 43 (33–54) | 505 | 64 | N/A | - | 53/787 | 7 | N/A | - | N/A | - |

| Parker A et al.41 2020 (South Africa) | 113 | Retrospective cohort | 48 (34–62) | 45 | 38.9 | N/A | - | 24/113 | 21.2 | N/A | - | 17/24 | 70.8 |

| Sigel K et al.42 2020 (USA) | 493 | Retrospective cohort | 61 (54–67) | 374 | 75.8 | 205/493 | 41.5 | 88/493 | 17.8 | 24/57 | 42.1 | 88/88 | 100 |

| Stoeckle K et al.43 2020 (USA) | 120 | Retrospective cohort | 60 (56–70) | 96 | 80 | 36/100 | 36 | 30/120 | 25 | 7/27 | 25.9 | 29/30 | 96.6 |

| Tesoriero JM et al.44 2020 (USA) | 377 245 | Retrospective cohort | 53 (45–67) | 51 | 70.5 vs 50.5 | 192 646 | 51 | 2988/377 245 | 0.8 | 270/2887 | 9.3 | 2834/2988 | 94.8 |

USA, United States of America; ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV/AIDS, human immunodeficiency virus / acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; IQR, interquartile range; N/A, not applicable.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The study’s outcome of interest was mortality from COVID-19. This was defined as the number of patients with COVID-19 whose death could not be attributed to a cause other than COVID-19. Two authors performed the data extraction. Relevant demographic, laboratory and clinical information was recorded on a dataform: age, gender, ethnicity, the number of PLWH, the number of patients with a CD4 cell count of <200 cells/μL, the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and the mortality outcomes of both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected participants. Two authors independently assessed the quality of each study using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.45 The selection, comparability and outcome of each study were assigned a score from zero to nine. Studies with scores of ≥7 were considered to be of good quality (see Table 3). All included studies were rated ‘good’. In summary, all studies were deemed fit to be included in the meta-analysis.

TABLE 3.

Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment of observational studies.

| First author | year | Study design | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berenguer J et al.21 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Bhaskaran K et al.17 | 2020 | Cohort | **** | ** | *** | 9 | Good |

| Boulle A et al.22 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Braunstein SL et al.23 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Cabello A et al.24 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Chilimuri S et al.25 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Docherty AB et al.26 | 2020 | Cohort | **** | ** | *** | 9 | Good |

| El-Solh AA et al.27 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Garibaldi BT et al.28 | 2020 | Cohort | **** | ** | *** | 9 | Good |

| Geretti AM et al.18 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Gudipati S et al.19 | 2020 | Cohort | ** | ** | *** | 7 | Good |

| Hadi YB et al.20 | 2020 | Cohort | ** | ** | *** | 7 | Good |

| Harrison SL et al.29 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Hsu HE et al.30 | 2020 | Cohort | ** | ** | *** | 7 | Good |

| Huang J et al.31 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Jassat W et al.32 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Kabarriti R et al.33 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Karmen-Tuohy S et al.34 | 2020 | Cohort | ** | ** | *** | 7 | Good |

| Kim D et al.35 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | **** | 9 | Good |

| Lee SG et al.36 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Maciel EL et al.37 | 2020 | Cohort | ** | ** | *** | 7 | Good |

| Marcello RK et al.38 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Miyashita H et al.39 | 2020 | Cohort | ** | ** | *** | 7 | Good |

| Ombajo LA et al.40 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Parker A et al.41 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Sigel K et al.42 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Stoeckle K et al.43 | 2020 | Cohort | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Tesoriero JM et al.44 | 2020 | Cohort | ** | ** | *** | 7 | Good |

Note: Asterisk denotes scores.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager version 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration) and the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3 software were used in the meta-analysis, and Mantel-Haenszel’s formula gave odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic with values of <25%, 26% – 50% and >50% providing low, moderate and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively. Significance was obtained if the two-tailed P-value was ≤0.05. The qualitative risk of publication bias was assessed using Begg’s funnel plot analysis.

Results

HIV and mortality

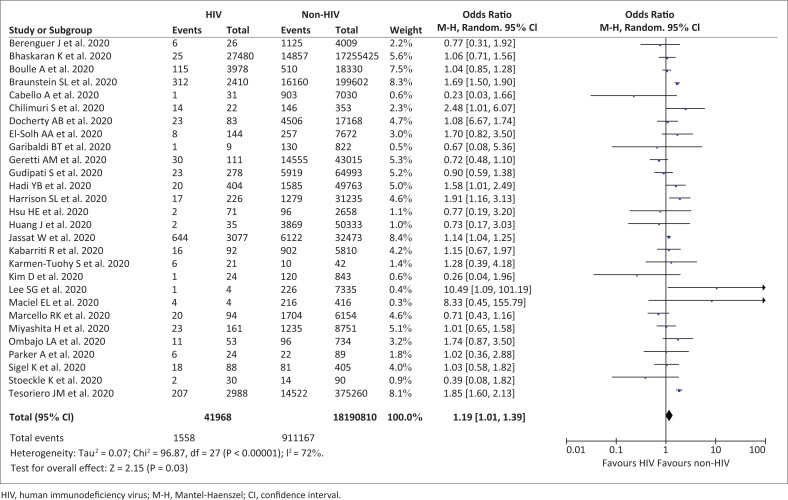

Our pooled analysis indicated that HIV was associated with mortality from COVID-19 [OR = 1.19 (95% CI 1.01–1.39), p = 0.03; I2 = 72%, random-effect modelling] (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot that demonstrates the association of HIV with mortality from COVID-19 outcome.

Meta-regression

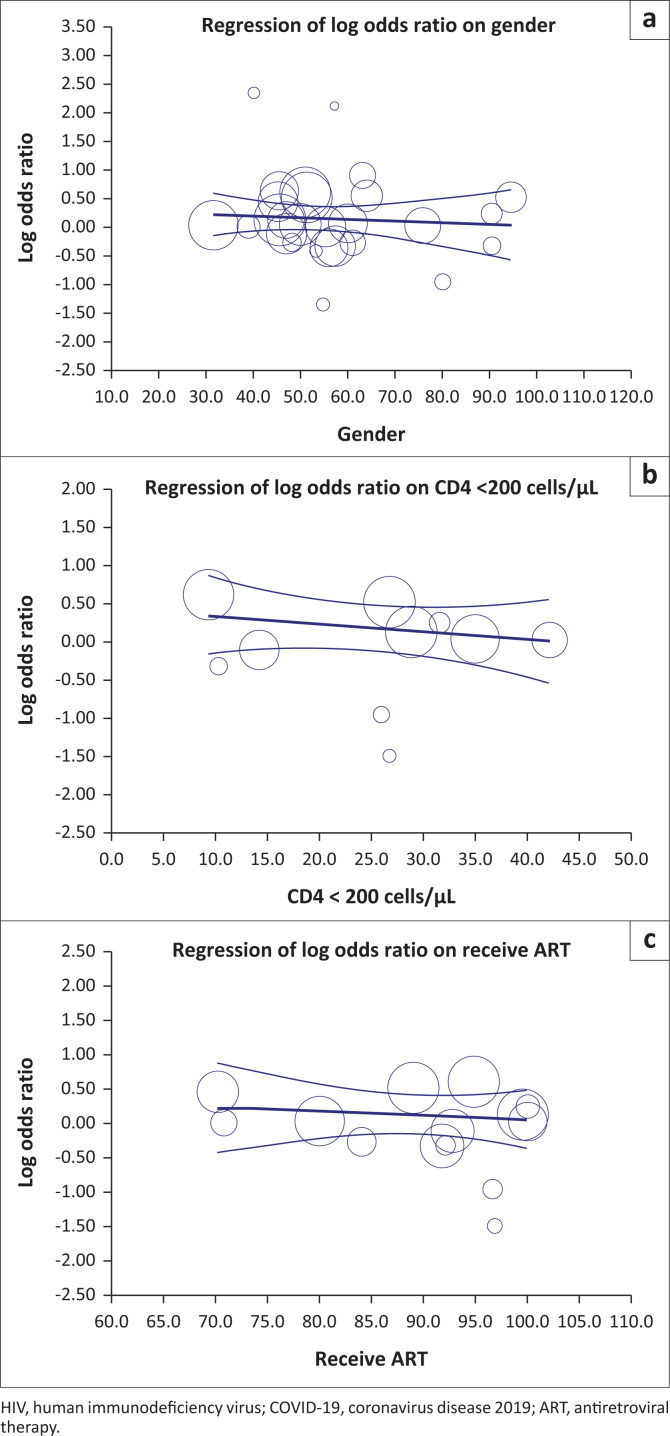

However, meta-regression showed that the association between HIV and mortality from COVID-19 was unaffected by age (p = 0.208), gender (p = 0.608) (see Figure 3a), Black ethnicity (p = 0.389), CD4 cell count of <200 cells/μL (p = 0.353) (see Figure 3b) or ART (p = 0.647) (see Figure 3c).

FIGURE 3.

Bubble-plot for meta-regression. Meta-regression analysis showed that the association between HIV and mortality from COVID-19 was not affected by gender (a), CD4 cell count (b) or ART (c).

Subgroup analysis

The subgroup analysis revealed that the association between HIV and mortality from COVID-19 was only statistically significant for studies from African regions [OR = 1.13 (95% CI = 1.04–1.23), p = 0.004; I2 = 0%, random-effect modelling] and the United States of America (USA) [OR = 1.30 (95% CI = 1.08–1.59), p = 0.006; I2 = 61%] but not for studies from Asia [OR = 2.41 (95% CI = 0.16–36.57), p = 0.53; I2 = 76%], or Europe [OR = 0.90 (95% CI = 0.70–1.15), p = 0.40; I2 = 5%].

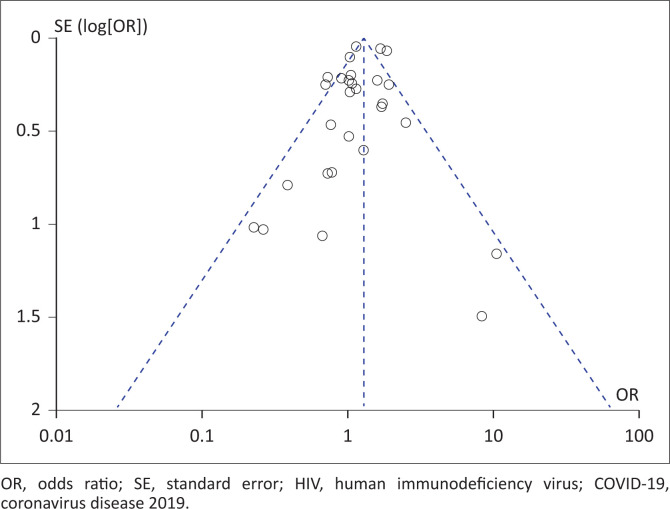

Publication bias

The funnel plot analysis revealed a qualitatively symmetrically inverted funnel plot for the association between HIV and a mortality outcome, suggesting no publication bias. This is demonstrated in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Funnel plot for the association of HIV with mortality from COVID-19 outcomes.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 studies not only analyse the association between HIV and mortality from COVID-19 but evaluate the role of confounding factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, CD4 cell count and ART in this cohort.

An association was found between HIV and mortality from COVID-19. However, this did not appear to be influenced by the confounding factors above. Instead, the subgroup analysis found that mortality from COVID-19 in PLWH was more likely to be reported in studies from Africa and the USA, rather than Asia or Europe. Factors unique to Africa, such as the large background prevalence of HIV, delayed access to healthcare (poor health ‘awareness’, an inadequate healthcare infrastructure and logistical challenges to accessing care) and ready access to alternate, non-Western, traditional health practitioners and medicines, are likely to have influenced outcomes.46,47 Similarly, the COVID-19 epidemic in the USA disproportionately affected the poor, people of colour and the socially marginalised such as drug users and the institutionalised. In both regions, PLWH may have been ‘over-represented’ in published studies.

Our pooled data confirmed an association of higher mortality from COVID-19 in PLWH.

Firstly, HIV infection may cause severe depletion of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue, with a predominant loss of memory CD4+ T cells.48 Human immunodeficiency virus-induced T-cell lymphopenia, which disrupts the innate and adaptive immune response, may predispose patients to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and progression to active disease, which increases the risk of latent tuberculosis reactivation by 20-fold.49,50 Previously published studies regarding COVID-19 have revealed that the presence of tuberculosis was associated with higher severity and mortality from COVID-19.51,52 Secondly, some proportions of PLWH may have incomplete immune reconstitution and evidence of persistent immune activation.53 They may show an abnormal innate and adaptive immune response, characterised by the elevation of macrophages, cytokines [tumour necrosis factor alpha, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-8 and IL-10], acute phase proteins [serum amyloid A, C-reactive protein (CRP)], elements of the coagulation cascade (D-dimer and tissue factor), increased turnover and exhaustion of T cells, increased turnover of B cells and hyperimmunoglobulinaemia.54,55 These conditions may contribute to the development of cytokine storms and severe outcomes in COVID-19. Furthermore, elevated CRP, D-dimer and IL-6 have been associated with severe COVID-19 based on meta-analysis studies.13,56 Thirdly, exhaustion of T-cell lymphocytes, which is observed in HIV progression, may also be exacerbated during COVID-19 infection, possibly as a result of the SARS-Cov-2 infection’s synergistic activity with HIV, which gradually results in T-cell lymphocyte apoptosis.57 This exhaustion of T-cell lymphocytes was associated with the progression and severe manifestation of COVID-19.58,59

Limitations

Firstly, only a limited number of our included studies reported on CD4 cell counts, viral loads and ART – a fact that is likely to have impacted the precision of the meta-regression analysis of this study. Indeed, most studies focussed on the characteristics of COVID-19 patients rather than its effects on PLWH. Secondly, the studies utilised in this review and meta-analysis were primarily observational and thus, may reflect occult confounders or biases unique to the particular study. Finally, we included some preprint studies to minimise the risk of publication bias; however, we made exhaustive efforts to ensure that only sound studies were included that we expect will eventually be published. We hope that this study can give further insight into the management of COVID-19 patients.

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis of observational studies indicates that HIV had an association with a mortality outcome from COVID-19; however, larger observational studies or even randomised clinical trials are needed to confirm our results and elucidate additional associations. Patients living with HIV must take extra precautions and always adhere to health-promoting protocols. They must be prioritised to receive COVID-19 preventive therapy: the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Where feasible, practical use must be made of telemedicine and virtual-based practice to provide continuous care to PLWH throughout this pandemic. Every effort must be made to identify co-infected PLWH and to link them with clinicians and treatment centres skilled in COVID-19 care. Gaps in ART-related care, such as medicine stockouts, must be identified by local healthcare providers and authorities. Finally, HIV co-infection must be included in future risk stratification models for COVID-19 management.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors’ contributions

T.I.H., J.R., K.C. and A.K. formulated the research questions; T.I.H. and J.R. developed the study protocol, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. T.I.H., J.R., K.C. and A.K. did the systematic review. A.K. supported and supervised the work. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Ethical considerations

This article followed all ethical standards for research without direct contact with human or animal subjects.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data analysed in this study were a reanalysis of existing data, which are openly available at the locations cited in the reference section.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Hariyanto TI, Rosalind J, Christian K, Kurniawan A. Human immunodeficiency virus and mortality from coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. S Afr J HIV Med. 2021;22(1), a1220. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhivmed.v22i1.1220

References

- 1.Cheng ZJ, Shan J. 2019 Novel coronavirus: Where we are and what we know. Infection. 2020;48(2):155–163. 10.1007/s15010-020-01401-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Situation report [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update---12-january-2021

- 3.Hariyanto TI, Rizki NA, Kurniawan A. Anosmia/hyposmia is a good predictor of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: A meta-analysis. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;25(1):e170–e174. 10.1055/s-0040-1719120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hariyanto TI, Kristine E, Jillian Hardi C, Kurniawan A. Efficacy of lopinavir/ritonavir compared with standard care for treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A systematic review. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2020. 10.2174/1871526520666201029125725 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hariyanto TI, Kurniawan A. Anemia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. TransfusApher Sci. 2020;59(6):102926. 10.1016/j.transci.2020.102926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hariyanto TI, Kurniawan A. Thyroid disease is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Diabetes MetabSyndr. 2020;14(5):1429–1430. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hariyanto TI, Putri C, Arisa J, Situmeang RFV, Kurniawan A. Dementia and outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch GerontolGeriatr. 2020;93:104299. 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hariyanto TI, Putri C, Situmeang RFV, Kurniawan A. Dementia is a predictor for mortality outcome from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;271:393–395. 10.1007/s00406-020-01205-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hariyanto TI, Putri C, Situmeang RFV, Kurniawan A. Dementia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Am J Med Sci. 2020;361(3):394–395. 10.1016/j.amjms.2020.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hariyanto TI, Prasetya IB, Kurniawan A. Proton pump inhibitor use is associated with increased risk of severity and mortality from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52(12):1410–1412. 10.1016/j.dld.2020.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hariyanto TI, Kurniawan A. Statin therapy did not improve the in-hospital outcome of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. Diabetes MetabSyndr. 2020;14(6):1613–1615. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soraya GV, Ulhaq ZS. Crucial laboratory parameters in COVID-19 diagnosis and prognosis: An updated meta-analysis. Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2020;155(4):143–151. 10.1016/j.medcle.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hariyanto TI, Japar KV, Kwenandar F, et al. Inflammatory and hematologic markers as predictors of severe outcomes in COVID-19 infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;41:110–119. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.12.076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang CC, Crane M, Zhou J, et al. HIV and co-infections. Immunol Rev. 2013;254(1):114–142. 10.1111/imr.12063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) . Global HIV & AIDS statistics – 2020 fact sheet [homepage on the Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 19]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

- 16.Zhu F, Cao Y, Xu S, Zhou M. Co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and HIV in a patient in Wuhan city, China. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):529–530. 10.1002/jmv.25732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhaskaran K, Rentsch CT, MacKenna B, et al. HIV infection and COVID-19 death: A population-based cohort analysis of UK primary care data and linked national death registrations within the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(1):e24–e32. 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30305-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geretti AM, Stockdale AJ, Kelly SH, et al. Outcomes of COVID-19 related hospitalization among people with HIV in the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterization Protocol (UK): A prospective observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa1605. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Gudipati S, Brar I, Murray S, McKinnon JE, Yared N, Markowitz N. Descriptive analysis of patients living with HIV affected by COVID-19. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(2):123–126. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hadi YB, Naqvi SFZ, Kupec JT, Sarwari AR. Characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with HIV: A multicentre research network study. AIDS. 2020;34(13):F3–F8. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berenguer J, Ryan P, Rodríguez-Baño J, et al. Characteristics and predictors of death among 4035 consecutively hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(11):1525–1536. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boulle A, Davies MA, Hussey H, et al. Risk factors for COVID-19 death in a population cohort study from the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa1198. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Braunstein SL, Lazar R, Wahnich A, Daskalakis DC, Blackstock OJ. COVID-19 infection among people with HIV in New York City: A population-level analysis of linked surveillance data. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa1793. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Cabello A, Zamarro B, Nistal S, et al. COVID-19 in people living with HIV: A multicenter case-series study. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:310–315. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chilimuri S, Sun H, Alemam A, et al. Predictors of mortality in adults admitted with COVID-19: Retrospective cohort study from New York city. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(4):779–784. 10.5811/westjem.2020.6.47919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with COVID-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: Prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. 10.1136/bmj.m1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Solh AA, Meduri UG, Lawson Y, Carter M, Mergenhagen KA. Clinical course and outcome of COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome: Data from a national repository. medRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.10.16.20214130 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Garibaldi BT, Fiksel J, Muschelli J, et al. Patient trajectories among persons hospitalized for COVID-19: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2020:M20–3905. 10.7326/M20-3905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Harrison SL, Fazio-Eynullayeva E, Lane DA, Underhill P, Lip GYH. Comorbidities associated with mortality in 31,461 adults with COVID-19 in the United States: A federated electronic medical record analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9):e1003321. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu HE, Ashe EM, Silverstein M, et al. Race/ethnicity, underlying medical conditions, homelessness, and hospitalization status of adult patients with COVID-19 at an Urban Safety-Net Medical Center–Boston, Massachusetts, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(27):864–869. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6927a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang J, Xie N, Hu X, et al. Epidemiological, virological and serological features of COVID-19 cases in people living with HIV in Wuhan City: A population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa1186. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Jassat W, Cohen C, Masha M, et al. COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in South Africa: The intersection of communicable and non-communicable chronic diseases in a high HIV prevalence setting. medRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.12.21.20248409 [DOI]

- 33.Kabarriti R, Brodin NP, Maron MI, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with comorbidities and survival among patients with COVID-19 at an Urban Medical Center in New York. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019795. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karmen-Tuohy S, Carlucci PM, Zervou FN, et al. Outcomes among HIV-positive patients hospitalized with COVID-19. J Acquir Immune DeficSyndr. 2020;85(1):6–10. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim D, Adeniji N, Latt N, et al. Predictors of outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with chronic liver disease: US multi-center study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020:S1542-3565(20)31288-X. 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SG, Park GU, Moon YR, Sung K. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for fatality and severity in patients with coronavirus disease in Korea: A nationwide population-based retrospective study using the Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) database. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8559. 10.3390/ijerph17228559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maciel EL, Jabor P, Goncalves Júnior E, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 hospital deaths in Espírito Santo, Brazil, 2020. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2020;29(4):e2020413. 10.1590/S1679-49742020000400022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcello RK, Dolle J, Grami S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 patients in New York City’s public hospital system. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243027. 10.1371/journal.pone.0243027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyashita H, Kuno T. Prognosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in patients with HIV infection in New York City. HIV Med. 2021;22(1):e1–e2. 10.1111/hiv.12920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ombajo LA, Mutono N, Sudi P, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients in Kenya. medRxiv. 2020. 10.1101/2020.11.09.20228106 [DOI]

- 41.Parker A, Koegelenberg CFN, Moolla MS, et al. High HIV prevalence in an early cohort of hospital admissions with COVID-19 in Cape Town, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2020;110(10):982–987. 10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i10.15067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sigel K, Swartz T, Golden E, et al. Covid-19 and people with HIV infection: Outcomes for hospitalized patients in New York City. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa880. 10.1093/cid/ciaa880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Stoeckle K, Johnston CD, Jannat-Khah DP, et al. COVID-19 in hospitalized adults with HIV. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(8):ofaa327. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tesoriero JM, Swain CE, Pierce JL, et al. Elevated COVID-19 outcomes among persons living with diagnosed HIV infection in New York state: Results from a population-level match of HIV, COVID-19, and hospitalization databases. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2020:2020.11.04.20226118. 10.1101/2020.11.04.20226118 [DOI]

- 45.Margulis AV, Pladevall M, Riera-Guardia N, et al. Quality assessment of observational studies in a drug-safety systematic review, comparison of two tools: The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and the RTI item bank. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:359–368. https://doi/org/10.2147/CLEP.S66677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ajayi AI, Mudefi E, Yusuf MS, Adeniyi OV, Rala N, Goon DT. Low awareness and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis among adolescents and young adults in high HIV and sexual violence prevalence settings. Medicine. 2019;98(43):e17716. 10.1097/MD.0000000000017716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stannah J, Dale E, Elmes J, et al. HIV testing and engagement with the HIV treatment cascade among men who have sex with men in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(11):e769–e787. 10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30239-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chinen J, Shearer WT. Secondary immunodeficiencies, including HIV infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S195–S203. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pawlowski A, Jansson M, Sköld M, Rottenberg ME, Källenius G. Tuberculosis and HIV co-infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(2):e1002464. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bruchfeld J, Correia-Neves M, Källenius G. Tuberculosis and HIV coinfection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5(7):a017871. 10.1101/cshperspect.a017871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sy KTL, Haw NJL, Uy J. Previous and active tuberculosis increases risk of death and prolongs recovery in patients with COVID-19. Infect Dis (Lond). 2020;52(12):902–907. 10.1080/23744235.2020.1806353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao Y, Liu M, Chen Y, Shi S, Geng J, Tian J. Association between tuberculosis and COVID-19 severity and mortality: A rapid systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):194–196. 10.1002/jmv.26311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paiardini M, Müller-Trutwin M. HIV-associated chronic immune activation. Immunol Rev. 2013;254(1):78–101. 10.1111/imr.12079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Douek DC. Immune activation, HIV persistence, and the cure. Top Antivir Med. 2013;21(4):128–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neuhaus J, Jacobs DR Jr, Baker JV, et al. Markers of inflammation, coagulation, and renal function are elevated in adults with HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(12):1788–1795. 10.1086/652749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coomes EA, Haghbayan H. Interleukin-6 in covid-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Med Virol. 2020;30(6):1–9. 10.1002/rmv.2141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fenwick C, Joo V, Jacquier P, et al. T-cell exhaustion in HIV infection. Immunol Rev. 2019;292(1):149–163. 10.1111/imr.12823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diao B, Wang C, Tan Y, et al. Reduction and functional exhaustion of T cells in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Front Immunol. 2020;11:827. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang PH, Ding YB, Xu Z, et al. Increased circulating level of interleukin-6 and CD8+ T-cell exhaustion are associated with progression of COVID-19. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):161. 10.1186/s40249-020-00780-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed in this study were a reanalysis of existing data, which are openly available at the locations cited in the reference section.