Abstract

The work outlined herein describes AU-011, a novel recombinant papillomavirus-like particle (VLP) drug conjugate and its initial evaluation as a potential treatment for primary uveal melanoma. The VLP is conjugated with a phthalocyanine photosensitizer, IRDye 700DX, that exerts its cytotoxic effect through photoactivation with a near-infrared laser. We assessed the anticancer properties of AU-011 in vitro utilizing a panel of human cancer cell lines and in vivo using murine subcutaneous and rabbit orthotopic xenograft models of uveal melanoma. The specificity of VLP binding (tumor targeting), mediated through cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG), was assessed using HSPG-deficient cells and by inclusion of heparin in in vitro studies. Our results provide evidence of potent and selective anticancer activity, both in vitro and in vivo. AU-011 activity was blocked by inhibiting its association with HSPG using heparin and using cells lacking surface HSPG, indicating that the tumor tropism of the VLP was not affected by dye conjugation and cell association is critical for AU-011–mediated cytotoxicity. Using the uveal melanoma xenograft models, we observed tumor uptake following intravenous (murine) and intravitreal (rabbit) administration and, after photoactivation, potent dose-dependent tumor responses. Furthermore, in the rabbit orthotopic model, which closely models uveal melanoma as it presents in the clinic, tumor treatment spared the retina and adjacent ocular structures. Our results support further clinical development of this novel therapeutic modality that might transform visual outcomes and provide a targeted therapy for the early-stage treatment of patients with this rare and life-threatening disease.

Introduction

We recently described the tumor tropic nature of human papillomavirus (HPV) capsids and demonstrated their ability to target a large panel of tumor types both in vitro and in vivo (1). This tropism is mediated through heparan sulfate modifications on cancer cells that mimic the modifications normally found on basement membrane proteoglycans but not the apical surfaces of intact tissues (2, 3). Exploiting this broad tropism, the recombinant virus-like particle (VLP) can act as a carrier for the delivery of a variety of cytotoxic payloads to cancer cells. Owing to its complex higher order structure, this type of carrier may have distinct advantages over existing platforms, such as antigen-driven technologies (e.g., antibodies), as the multivalency of the VLP permits many sites of interaction, thereby facilitating a strong association with tumor cells. In addition, as a consequence of their size and complex structure, VLPs also have the capacity to deliver hundreds of payload molecules per binding event. Thus, the VLP platform offers unique characteristics that can be potentially exploited as novel cancer therapeutics across broad cancer indications in a tumor–antigen independent manner.

AU-011 is comprised of two recombinantly expressed HPV-derived capsid proteins, L1 and L2, that self-assemble into VLPs to which the photostable phthalocyanine photosensitizer IRDye 700DX (IR700) has been conjugated (4). Use of IR700 as a cytotoxic agent was first described by Mitsunaga and colleagues (5) in the context of tumor targeting using antibodies. This group has demonstrated the potency of this photosensitizer and its ability to directly kill and indirectly potentiate antitumor immunity (6, 7), and clinical trials are currently under way targeting EGFR-positive head and neck tumors (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02422979; ref. 8). IR700 has been described to induce potent necrosis-mediated cell killing when delivered to a cancer cell membrane via conjugation to an antibody and has several advantages over traditional cytotoxic agents used for targeted cancer therapy (9, 10). First, IR700 is cytotoxic only during its activation by light, providing an additional level of specificity in addition to the targeting properties of an antibody or VLP. Second, IR700 is activated at a wavelength of 690 nm, and light from this part of the spectrum penetrates relatively deeply into tissues (11). Finally, based on its mechanism of action, unbound IR700 is not cytotoxic, reducing the risk of off-target effects (5). Although not yet fully understood, IR700-mediated cell killing is likely attributed to both local generation of reactive oxygen species and localized heating of cell-associated water, resulting in disruption and permeabilization of the cellular membrane (5).

AU-011 is a first-in-class experimental therapy currently being clinically evaluated for the treatment of primary uveal melanoma (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03052127). Although it is a rare disease, uveal melanoma is the most common primary ocular cancer in adults (12, 13). Currently, the most widely used first-line treatment options for this disease are radiation-based therapies and surgery. There are two main types of radiotherapy: plaque brachytherapy, using iodine-125, ruthenium-106, or palladium-103, or radiation applied as proton-beam therapy (13). Both of these radiation-based therapies require surgical procedures to place the plaque, in the case of brachytherapy, or to place fiducial markers enabling localization of the tumor, in the case of proton beam therapy. Alternatives to radiation have been explored, including transpupillary thermotherapy and verteporfin-mediated photodynamic therapy; however, these treatments carry their own risks while offering limited clinical benefit (14). Enucleation is often the first-line treatment for blind, painful eyes, or uncontrolled tumor growth. Although the aforementioned therapies regularly achieve good local disease control, none of them influence the survival rate for patients with uveal melanoma (15-17). In addition, radiation lacks tumor tissue specificity and often is accompanied by irreversible radiation damage to the retina and other ocular structures that can result in severe vision impairment or vision loss (18-20). Despite success in local control of primary tumors with radiotherapy, liver metastasis remains the driver of mortality in approximately 50% of patients (12, 13). Although great advances in early diagnosis have been achieved over the past few years (21-23), 5-year survival rates have not improved. As with most cancers, early detection and early intervention are likely critical for a positive long-term survival outcome in uveal melanoma. Taken together, these observations call attention to an unmet medical need for the early treatment of small melanocytic lesions or small melanomas in the eye to achieve local disease control and vision preservation with the added potential to improve long-term survival outcomes for patients.

Described herein, we have evaluated the tumor-specific targeting and light activated cellular toxicity by AU-011 toward a panel of human tumor cell lines in vitro. We further evaluated the in vivo activity of AU-011 using murine subcutaneous and rabbit orthotopic xenograft models of uveal melanoma to explore the antitumor potency of AU-011. The results of these experiments support the ongoing phase Ib/2 clinical trial and provide compelling evidence for further clinical evaluation of AU-011 for the primary treatment of uveal melanoma.

Materials and Methods

Production of VLP conjugates (AU-011)

A mutant version of the HPV16L1 gene (24) and the prototype HPV16 L2 gene were used to produce L1/L2 VLPs mammalian HEK293 cells as described previously (25). VLPs were purified through a series of chromatographic media, namely sulfate (EMD Millipore) and SPXL (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) cation exchange resin, and QXL (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) anion exchange resin. The final eluate pool contained greater than 90% of capsid proteins (L1 and L2 proteins) on SDS-PAGE. IRDye 700DX (IR700; LI-COR Biosciences) was covalently linked to purified VLPs through N-hydroxysuccinimide reactive group with groups on the VLP, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Finally, free dye was separated from AU-011 by tangential flow filtration, and final AU-011 product was quantified by BCA analysis (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Cells and cell culture

Tumor cell lines were routinely cultured in DMEM (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS (Corning). CHO-K1 and pgsA-745 were supplemented with 200 μmol/L proline. 92.1MEL and HSC-3 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Grossniklaus (Emory University, Atlanta, GA; ref. 26) and Dr. Jose Baselga (MSKCC, NY, NY), respectively; HeLa, T24, CHO-K1, and pgsA-745 were purchased from ATCC, and all other cell lines were obtained through the NCI Developmental Therapeutics program as part of the NCI-60 panel. All cell lines were authenticated by STR analysis at the time of receipt, determined to be mycoplasma free (MycoAlert; Lonza) and used within 10 passages of their initial freeze down.

Assessment of AU-011 binding and potency and inhibition by heparin

The binding protocol has been described previously (1); briefly, cells were detached using 10 mmol/L EDTA and allowed a 4-hour recovery while rocking at 37°C in culture media. AU-011 was serially diluted 3-fold ranging from 0.3 pmol/L (7.5 ng/mL) to 1,000 pmol/L (25 μg/mL) and was left in sample diluent alone (PBS supplemented with 2% FBS) or incubated with 1 mg/mL heparin (Sigma, #H4788) at 4°C for one hour prior to addition to the cells. Unless otherwise noted, for experiments using a fixed amount of AU-011, 300 pmol/L was used and when using free IR700, a molar equivalent to the dye content of 300 pmol/L AU-011 was used. After recovery, cells were suspended in cold sample diluent at a density of 2 × 106 cells/mL and aliquoted into a 96-well plate followed by incubation with AU-011 samples for one hour at 4°C. Cells were then washed, resuspended in phenol-red free DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, and half of the cells were transferred to a black, round-bottom plate and irradiated with 25 J/cm2 of 690 nm light (Modulight ML6700-PDT with MLA Kit). The remaining cells served as light untreated (0 J/cm2) controls. Following light treatment, all cells were allowed a 2-hour recovery at 37° C. Cells were then stained using LIVE/DEAD Yellow fixable stain (as per the manufacturer's protocol; Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by 10-minute fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde (EMS) and acquired using a BD FACS Canto II outfitted with an HTS (BD Biosciences). AU-011 is visible in the APC-Cy7 channel, and these data were used to determine binding percentage. Data were analyzed using FlowJo v10 and the EC50s were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis from curves generated using GraphPad Prism v7.

Microscopy

92.1MEL cells were preplated at 2.5 × 104 cells/500 μL in a 24-well plate and allowed to grow for 48 hours. A total of 7.5 μg/mL (300 pmol/L) of AU-011 was incubated for one hour ± 1 mg/mL heparin at 4°C and then added to the plated cells for one hour at 37°C. IR700 dye was also added in an amount equivalent to the amount that is conjugated to 300 pmol/L of AU-011. After one hour, cells were washed twice and then either kept in the dark or exposed to 25 J/cm2 of 690 nm light. Images were acquired within 15 minutes of light treatment using an inverted microscope (Olympus).

Animals

Eight-week-old female athymic nude mice (Charles River Laboratories, Crl:NU(NCr)-Foxn1nu) and 4-month-old male New Zealand White rabbits (Charles River Laboratories) were used. Animal studies described herein were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the NCI (Bethesda, MD; mice) and Biomedical Research Models Inc. and ORA Inc. (Andover, MA; rabbits).

Mice.

92.1MEL cells were detached using 10 mmol/L EDTA and counted. A total of 3.5 × 106 92.1MEL cells (>98% viability) were implanted subcutaneously in the hind flank and allowed to grow. When tumors reached a size of 40 to 80 mm3, they were randomized into treatment groups: vehicle (PBS), 100 μg AU-011, or 200 μg AU-011. PBS and AU-011 were delivered by tail vein injection, and after 12 hours, animals were exposed to 25 or 50 J/cm2 of 690 nm light using the MLL-III-690 laser (Opto Engine) connected with a fiber optic cable to a collimator (25.4 mm BK7, CeramOptec). One day later, tumors were excised and processed for viability measurement. Briefly, tumors were cut into 2 to 3 mm3 pieces and digested in a 37°C shaker in 4 mL PBS supplemented with 2% FBS, collagenase A (Roche), and DNase I (Roche) for 20 to 30 minutes. Tumors and released cells were then gently pressed through a 70-μm cell strainer (Corning) and washed with two volumes of PBS supplemented with 2% FBS. Approximately 106 cells were then transferred to a round-bottom 96-well plate, washed with PBS and stained using LIVE/DEAD Yellow fixable stain (as per the manufacturer's protocol) and fixed for 10 minutes at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde. Data were acquired by flow cytometry as described above.

Rabbits.

Rabbits were immunosuppressed with daily subcutaneous injections of cyclosporine (CsA; Sandimmune 50 mg/mL; Novartis Pharmaceuticals). CsA administration was maintained throughout the experiment to prevent immuno-mediated tumor regression. The dosage schedule was 15 mg/kg per day for 3 days prior to cell inoculation and 10 mg/kg per day until the end of the experiment. During this period, animals were monitored daily for signs of CsA toxicity, and the dose of CsA was adjusted at the discretion of an attending veterinarian.

Tumor cell implantation.

The implantation of 92.1MEL human uveal melanoma cells in New Zealand White rabbits has been described elsewhere (27). Briefly, 1.5 × 106 92.1MEL human uveal melanoma cells, suspended in PBS, and in some cases PBS + 50% Matrigel (Corning), in a volume of 50 to 100 μL suspension was injected into the suprachoroidal space of one eye using a bent cannula. The day following surgery and weekly thereafter, all animals were examined by fundus examination. Tumor size estimates were made by fundus observations and optical coherence tomography and randomized and treated 13 days postimplantation. Tumor sizes were estimated and recorded as size ratio to the optic nerve head.

Intravitreal injections.

Tumor-bearing rabbits were administered test agent or vehicle by intravitreal injection. Typically, rabbits were anesthetized with ketamine 30 to 40 mg/kg and xylazine 5 to 10 mg/kg. After anesthesia, 1 to 3 drops of 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride was applied to the tumor-bearing eye. After eye fixation, a 29-gauge U-100 insulin syringe was used for injection. The needle was inserted at a 45 degree angle toward the sclera plane approximately 1 to 3 mm from the limbus, aimed toward the optic nerve head. For the dose–response studies, 50, 20, or 5 μg of AU-011 or vehicle was injected into the eye quickly, and the needle was removed slowly to prevent efflux of AU-011 or vehicle. Antibiotic ointment was applied to the treated eye. For the studies assessing tumor uptake of AU-011, 16.5 or 40 μg was administered, and tumors were harvested at the designated time points (no laser treatment).

Laser administration.

Laser treatment occurred 6 to 8 hours after AU-011 administration. This treatment (injection followed by lasering) was repeated 7 days later. Laser treatment was applied using a slit lamp system with a Zeiss Visulas 690s laser (Carl Zeiss AG) delivering 690 nm light at an irradiance of 600 mW/cm2 over a duration of 83 seconds for a total fluence of 50 J/cm2. The laser spot size was set to a diameter of 5 mm and as such, tumors that were greater than this size were lasered with overlapping spots. In cases where a clear distinction of the tumor border could not be delineated due to ocular complications (vitritis, retinal detachment, etc.), the entire suspicious area was lasered. In cases where the tumor was anterior to the equator, only the accessible part of the tumor was lasered, which served as an internal control to delineate the effect of AU-011 in the absence of laser activation.

Histopathology.

For tumor localization studies, tumors were harvested at the designated time points after AU-011 injection. Samples were divided into two pieces; one was processed for microscopy as described below and the other flash frozen for lysate production and AU-011 quantification. For the dose–response studies using laser treatment, 2 to 3 or 8 to 9 days following the second treatment, animals were euthanized and the tumored eyes were removed. Microscopy processing is as follows: Samples were fixed in Davidson's fixative and embedded in paraffin blocks [formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE)]. Four- to 5-mm sections were then generated from these FFPE blocks, and these were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Assessment of AU-011 tumor penetration and pharmacokinetics

Preparation of tissue lysates.

Frozen and weighed tissues were first thawed on ice and suspended in lysis buffer (50 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4 containing 1% Triton X-100, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L EGTA). Included in the lysis buffer is Halt Protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Typically, 40 mg of tissue was homogenized in 1 mL of lysis buffer. Tissues were homogenized using an OMNI Tissue Master (TMP125-115; Omni International Inc.) at 70% full power for 10- to 15-second bursts. Following homogenization, the samples were centrifuged at low speed to pellet-insoluble debris. The resulting supernatant was removed and aliquoted for subsequent analysis.

Quantification of AU-011 by dot blot or SDS-PAGE.

Briefly, samples to be analyzed were first prepared with 4× denaturation buffer (250 mmol/L Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 8% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol). A standard curve of AU-011 was also prepared by dilution of stock AU-011 in the same matrix as the samples to a high concentration of 625 ng/mL. Standards were prepared through 1:1 serial dilutions of the high concentration standard and then prepared in denaturation buffer in a manner identical to the test samples. Standards and samples were heated to 95°C for 5 minutes and then assayed by SDS-PAGE or dot blot. For dot blot analysis, samples were applied to a nitrocellulose membrane that had been assembled within a 96-well vacuum manifold. Following the application of the samples, the wells of the vacuum manifold were washed twice with PBS. The membrane was then removed from the apparatus and imaged on an Odyssey CLx gel imager (LI-COR Biosciences) to detect the fluorescence of IR700, the conjugate in AU-011. Estimates of AU-011 levels in tissue samples were generated by comparing the fluorescence intensity of the sample to the standard curve. For SDS-PAGE analysis, samples were run on Any kD TGX gels (Bio-Rad) with the gel similarly imaged and analyzed as described above.

Results

AU-011 induces rapid cell death upon photoactivation

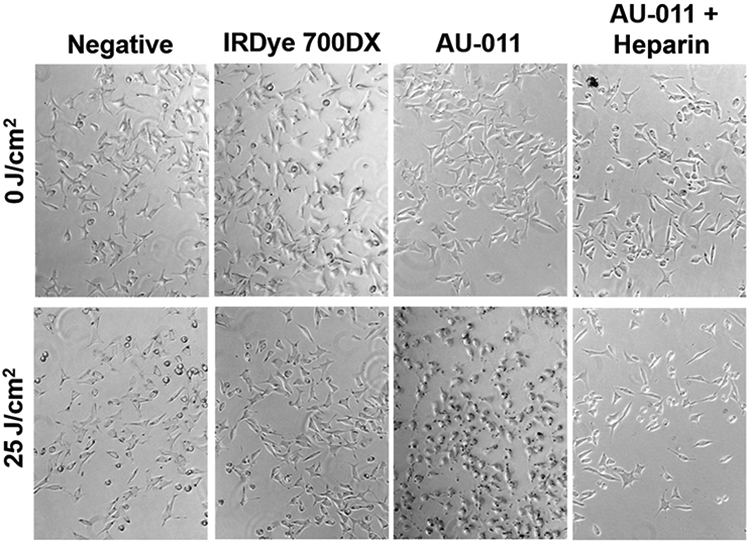

To first assess efficacy and specificity, 92.1MEL uveal melanoma cells were incubated with free IR700 dye or AU-011 in the presence or absence of heparin and either exposed to 25 J/cm2 of 690 nm light or kept in the dark, to serve as control (0 J/cm2). Cells were examined microscopically and images acquired immediately after light treatment (Fig. 1). Only cells that were bound by AU-011 and exposed to light were noticeably affected by the treatment. Within minutes following light treatment, cells became rounded and began to detach (also see Supplementary Fig. S1A-S1D for 3D time-lapse rendering). Inclusion of heparin blocked this effect, indicating that dye conjugation did not alter the heparan sulfate proteoglycan (HSPG) dependence of particle binding. Some cell detachment was noted in the wells that received heparin; however, there was no appreciable difference between 0 and 25 J/cm2 treatment. Irradiated cells exposed to IR700 dye alone were not killed, reinforcing the importance of delivery of the dye to the cell surface via the VLP for its cytotoxicity (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S2A and S2B show HeLa and 92.1MEL cells, respectively). In addition, AU-011–mediated toxicity is directly proportional to light fluence, indicating that it may be plausible to use less AU-011 and more light should the experimental conditions require it (Supplementary Fig. S3A and S3B show HeLa and 92.1MEL cells, respectively).

Figure 1.

Rapid HSPG-mediated tumor killing by AU-011. 92.1 cells were preplated at 2.5×104/500 μL in a 24-well plate and allowed to grow for 48 hours. A total of 7.5 μg/mL (300 pmol/L) of AU-011 was incubated for 1 hour ± 1 mg/mL heparin at 4°C and then added to the cells for 1 hour at 37°C. IR700 dye was also added in an amount equivalent to that which is conjugated to 300 pmol/L of AU-011. After 1 hour, cells were washed twice and then either kept in the dark or exposed to 25 J/cm2 of 690 nm light. Images were acquired within 15 minutes of light treatment.

Breadth and specificity of AU-011 binding and killing

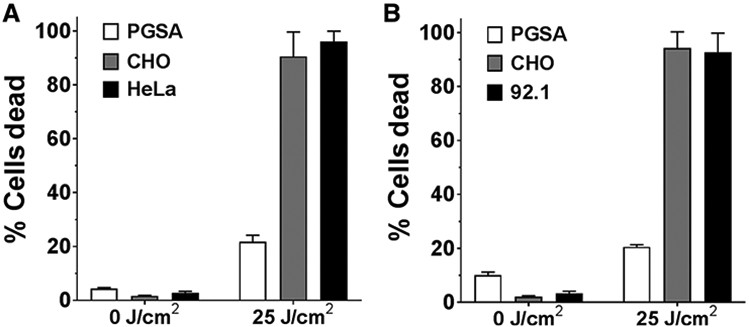

A panel of human tumor cell lines (ovarian, lung, breast, cervical, cutaneous melanoma, head and neck, bladder, and uveal melanoma) was assessed for their AU-011–binding ability and the role of HSPG in this binding. Cells were incubated with a range of AU-011 from 0.3 to 1,000 pmol/L, and binding was measured by detecting the IR700 signal by flow cytometry. Values were plotted and the EC50s were calculated (Table 1). Cutaneous melanoma (SK-MEL-2) and head and neck (HSC-3) tumor cells demonstrated the strongest binding with EC50s at 11.74 and 10.99 pmol/L, respectively. Lung tumor cells, NCI-H460, demonstrated slightly reduced binding with an EC50 of 133.7 pmol/L. Overall, binding was similar among all lines tested, and heparin blocked this binding (example of curves in Supplementary Fig. S4). When cells were subjected to 690 nm light, a concentration-dependent killing effect was observed. This potency was measured using a cell viability dye detectable by flow cytometry. The EC50 values for cell killing are shown in Table 1, and very little difference could be observed between cell types (range, 20–70 pmol/L). Consistent with the binding data, cell death was not observed in the presence of heparin (Supplementary Fig. S4). To further assess the HSPG requirement for binding and killing, HeLa cells and 92.1MEL cells were combined at a 1:1 ratio with either HSPG-deficient pgsA-745 (28, 29) or parental CHO-K1 cells in the presence or absence of AU-011 and exposed to 25 J/cm2 of 690 nm light. Immortalized parental CHO-K1 cells express modified surface HSPG similar to those found on tumors, thus enabling AU-011 binding and killing (28-30). The tumor cell lines were killed in these coculture experiments, whereas the HSPG-deficient cells remained viable, indicating that there is little bystander effect and that AU-011 must be bound specifically to the target cell (Fig. 2A, HeLa cells and Fig. 2B, 92.1MEL cells; gating example shown in Supplementary Fig. S5).

Table 1.

Binding and potency EC50 values (pmol/L) of AU-011 on a panel of human tumor cell lines

| Binding | Killing | |

|---|---|---|

| 92.1MEL | 27.37 ± 1.385 | 61.74 ± 2.142 |

| NCI-H460 | 133.7 ± 50.94 | 70.32 ± 28.25 |

| HeLa | 26.17 ± 3.137 | 66.24 ± 2.708 |

| HSC-3 | 10.99 ± 1.115 | 24.72 ± 0.918 |

| MCF-7 | 53.28 ± 6.519 | 37.21 ± 4.58 |

| SK-MEL-2 | 11.74 ± 0.956 | 25.24 ± 1.693 |

| SK-OV-3 | 23.2 ± 1.414 | 37.86 ± 6.831 |

| T24 | 41.12 ± 5.142 | 60.1 ± 18.53 |

NOTE: Values represent mean pmol/L ± SEM, obtained from three experiments performed in triplicate.

Figure 2.

HSPG specificity of AU-011 activity. HeLa (A) or 92.1MEL (B) cells were combined at a 1:1 ratio with either CHO-K1 (gray bar) or pgsA-745 cells (white bar) and coincubated with AU-011 at 300 pmol/L for 1 hour at 4°C. Cells were washed and then exposed to 25 J/cm2 or kept in the dark (0 J/cm2). Prior to combining cell lines, human cell lines were incubated with CFSE, and hamster cell lines were incubated with CellTrace Violet to distinguish the populations for flow cytometry analysis (example of the analysis provided in Supplementary Fig. S5). Data are reported as % dead as determined by viability staining. Values plotted are the mean of two experiments performed in triplicate and error bars represent the SEM.

In vivo activity of AU-011

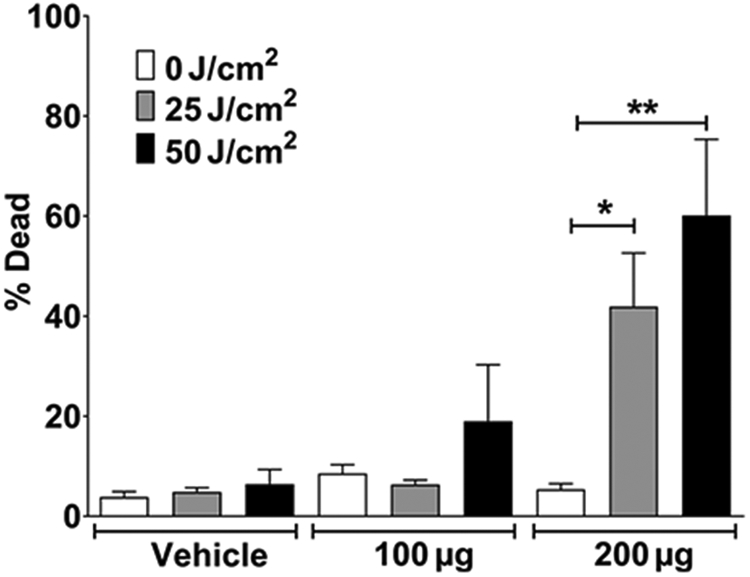

We initially tested AU-011’s ability to both target and kill 92.1MEL tumors in a murine model. Cells were implanted subcutaneously in nude mice and allowed to establish. When tumors reached a size range of 40 to 80 mm3, animals were randomized and intravenously injected by tail vein, with vehicle (PBS) or one of two doses of AU-011, 100 or 200 μg. After 12 hours, tumors were exposed to either 25 or 50 J/cm2 of 690 nm light, and tumors were harvested one day later to determine viability (Fig. 3). Some cytotoxic activity was observed with 100 mg, but only in conjunction with the 50 J/cm2 light treatment. However, 200 μg of AU-011 was capable of eliciting significant tumor killing at both the 25 and 50 J/cm2 light doses. These data were supportive of AU-011 activity against the 92.1MEL uveal melanoma tumor line in vivo and thus warranted evaluation in a more clinically representative orthotopic model.

Figure 3.

Dose-dependent AU-011 tumor killing in vivo. AU-011 was systemically administered to nude mice with subcutaneous 92.1 tumors (40–80 mm3). After 12 hours, animals were exposed to 25 or 50 J/cm2 690 nm light. Tumors were removed after 24 hours, homogenized, and viability measured by flow cytometry. Vehicle, n = 3; AU-011, n = 5. Data are representative of two experiments. Two-tailed Student t test: *, P = 0.0091; **, P = 0.0071.

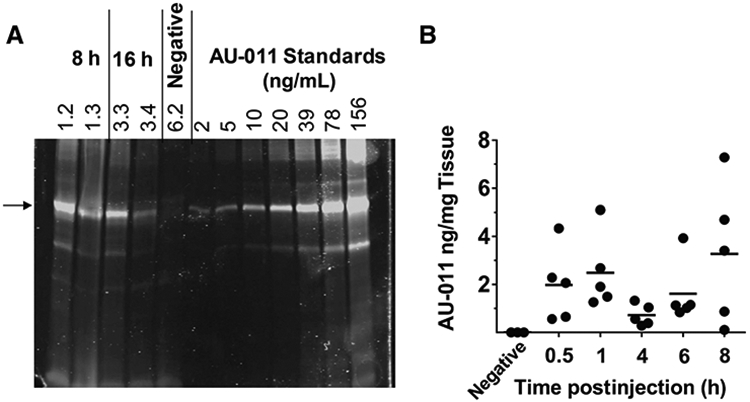

Assessment of tumor uptake and pharmacokinetics of AU-011 after intravitreal administration

We assessed the tumor distribution and pharmacokinetics after an intravitreal administration in a rabbit orthotopic xenograft model of human uveal melanoma using 92.1MEL tumor cells. The tumor cells were injected into the choroid space, the initiation site of most human uveal melanomas. Because AU-011 is fluorescent, a property imparted upon it by the IR700-conjugated molecule, we were able to directly image its presence in cancer tissue after a single intravitreal injection in the tumor-bearing rabbit eye. Tumors were divided into two pieces, one for AU-011 quantification by SDS-PAGE analysis and one for microscopic imaging and localization. Figure 4A shows that the IR700 signal on the SDS-PAGE gel corresponds to the input AU-011 L1 protein used in the standard verifying that AU-011 had indeed localized to the tumor tissue. For quantitative measurement of AU-011 in tumor tissues upon intravitreal injection, a dot-blot procedure was utilized. Figure 4B depicts the AU-011 levels, as measured by IR700 fluorescence, in tumor tissue following a series of time intervals after intravitreal injection. The data show appreciable levels of AU-011 in tumor tissue across these time points. To verify the presence of AU-011 by an orthogonal method, the 8- and 16-hour tissues from the same animals that were processed for AU-011 quantification described above were also processed for fluorescence confocal microscopy (Supplementary Fig. S6A-S6C shows 8-hour tissues and Supplementary Fig. S6D-S6F shows 16-hour tissues). AU-011–derived signal can be observed in the tumor tissue harvested from the rabbits, and no signal is present in the saline-treated control animals. It has been described that the retinal pigmented epithelium and choroid autofluoresce in the near-infrared range (31). This likely accounts for the fluorescence signal that is observed at the tumor edges in both the control and treated animals in Supplementary Fig. S6A-S6F.

Figure 4.

Accumulation of AU-011 in 92.1MEL ocular tumors after intravitreal injection. A, SDS-PAGE of tumor lysates from samples used in confocal microscopy (see Supplementary Fig. S6A-S6F) and analyzed on Odyssey CLx imager at 700 nm. Two examples each of rabbit 92.1MEL tumor lysates 8 (rabbits 1.2 and 1.3) or 16 hours (rabbits 3.3 and 3.4) after intravitreal injection. The negative control received vehicle only (rabbit 6.2). The arrow indicates the predominant L1 protein in AU-011. B, Measurement of AU-011 levels in tumor tissue lysates. Each dot represents AU-011 levels measured in the tumor recovered from one animal.

Activity of AU-011 in vivo

A study was then designed to assess a dose response to AU-011 in the rabbit xenograft model. In this case, AU-011 was administered by intravitreal injection weekly for 2 consecutive weeks. Laser was applied 6 to 8 hours following each AU-011 administration.

In this study, a total of 16 tumor-bearing rabbits were enrolled and randomized into four dose cohorts, specifically, 50 μg (n = 5), 20 μg (n = 4), 5 μg (n = 5), and vehicle control (n = 2). After completing the two weekly cycles of AU-011 or vehicle plus laser treatment, the animals were euthanized either 2 to 3 days after the second treatment, or 8 to 9 days after the second treatment. All 16 animals had apparent tumors between 2 and 5 times the size of the optic nerve head determined by fundoscopic examination at the outset of the study. Histopathologic analysis revealed a dose–response effect for AU-011. Tumors from the control animals (Fig. 5A) were generally free from necrosis except for small focal areas, which are not unexpected in a tumor xenograft model. In the 50 μg dose group, the animals that were euthanized 2 days after treatment showed profound tumor necrosis across the entire depth of the tumor tissue, an example of which is shown in Fig. 5B. Animals that were euthanized 8 to 9 days after the second treatment generally had smaller tumors with evidence of necrosis. In one animal (Supplementary Fig. S7A), the tumor was very small and comprised mostly of monocytic infiltrate, with evidence of few cancer cells and no visible damage to the adjacent retina.

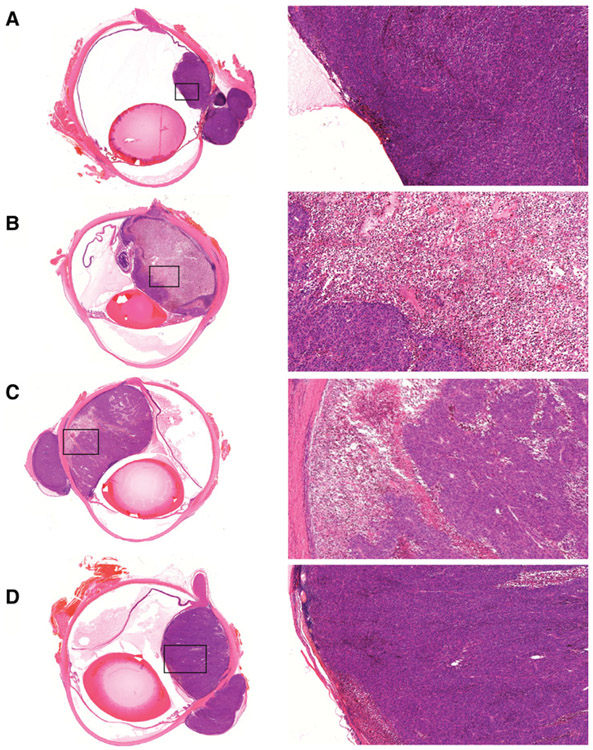

Figure 5.

AU-011 anticancer activity in a rabbit orthotopic xenograft model of uveal melanoma. Panels show H&E-stained sections of tumor-bearing rabbit eyes from the vehicle (A), 50 μg (B), 20 μg (C), and 5 μg (D) treated cohorts 2 days after treatment. Higher magnifications shown on the right are demarcated by black boxes in the overview images on the left.

The 20 μg cohort also revealed a potent antitumor effect upon examination 2 days following the final dose. Figure 5C shows considerable necrosis in a large tumor. In the 20 μg samples analyzed 8 to 9 days after the last treatment, a rabbit with a smaller tumor at the time of treatment revealed a residual lesion with intact retina overlaying the region (Supplementary Fig. S7B). In the cohort receiving 5 μg of AU-011, there was evidence of necrosis following AU-011 and laser treatment, but to a lesser extent as illustrated in Fig. 5D and Supplementary Fig. S7C. Of note, some animals had extraocular tumors that were not accessible by the laser that conveniently served as internal controls. No necrosis can be observed in these extraocular tumors, lending support to the lack of toxicity of AU-011 in the absence of light (Fig. 5C and D; Supplementary Fig. S7C). Importantly, no retinal damage was observed in any of the treated animals, further emphasizing the specificity of this treatment and the lack of off-target effects.

Discussion

In this report, we describe a novel VLP/drug conjugate, AU-011, and, through a variety of in vitro and in vivo experiments, demonstrate its robust targeted anticancer activity, indicating potential utility for the primary treatment of uveal melanoma. Our VLP/drug conjugate is based on the capsid proteins of HPV. It is well described that HPV attachment and infection requires modified HSPG (namely N-sulfation), and this is the means by which HPV-based VLPs interact with cancer cells (1, 3, 32, 33). In the current study, we demonstrate that HSPG-mediated binding of AU-011 occurs across a broad panel of human tumor cell lines in vitro. Of particular importance is the demonstration that HSPG surface expression on tumor cells is critical for AU-011 binding and activity, consistent with previously published work (1).

AU-011, in combination with 690 nm laser light (25 J/cm2) in vitro, was found to have extremely potent cytotoxicity, with EC50 values in the low picomolar range regardless of tumor type. This potency is thought to be attributable to two unique characteristics of AU-011: First, multivalency of binding results in a strong interaction with target cells; and second, the ability to conjugate a large number of IR700 dye molecules to a single VLP results in the deposition of high concentrations of the photosensitizer localized on the cell membrane. This cell association is critical, as the equivalent amount of free dye (not conjugated to the VLP) had no demonstrable killing activity on cells in the presence or absence of light corroborating the findings of Mitsunaga and colleagues (5). In addition, AU-011–mediated killing was inhibited by the inclusion of soluble heparin, suggesting that not only is free IR700 inert, but that unbound AU-011 is ineffective. Furthermore, the importance of cell association and HSPG dependence was confirmed when AU-011 displayed no bystander toxicity when coincubated with a mixed cell population comprised of a 1:1 ratio of tumor cells and HSPG-deficient cells. Uveal melanoma tumors have been shown to express surface HSPG and have increased endosulfatase expression in high-grade disease (34, 35). Taken together, when considering the use of AU-011 in the context of specific laser photoactivation for the treatment of uveal melanoma, these results strongly suggest the possibility of a treatment with high tumor specificity due to HSPG expression and the possibility to avoid damage to key ocular structures.

The proposed use of AU-011 to treat uveal melanoma utilizing VLPs to deliver IR700 via intravitreal administration would require that AU-011 distributes throughout the ocular tumor tissue prior to activation with 690 nm light. Our studies using confocal fluorescence microscopy showed that AU-011 does in fact diffuse throughout tumor tissue after intravitreal injection. Assuming a tumor tissue density of 1 g/mL (31, 36), the AU-011 levels in tumor tissue were estimated to be between 28 and 130 pmol/L (Fig. 4B), within the range of EC50s determined for 92.1MEL cell killing (Table 1), indicating that pharmacologically relevant levels of AU-011 were achieved in this tumor model. Sano and colleagues (37) have demonstrated increases in local tumor vascularity after Ab-IR700 treatment, leading to an influx of additional drug into the tumor, which could in turn, be activated with additional light treatments. We are exploring this phenomenon using AU-011, and early data support multiple light treatments as more efficacious and may also allow use of lower drug concentrations (unpublished data).

The predictions made from our biodistribution studies were tested in a dose–response experiment using the orthotopic model in conjunction with intravitreal injection to determine AU-011 activity in vivo. AU-011 elicited profound antitumor activity in the rabbit orthotopic xenograft model of human uveal melanoma that has previously been used to test the efficacy of other therapeutics (38, 39). Evidence of complete responses and a dose response could be observed by histologic evaluation, revealing the absence of cancer cells subsequent to administration of two doses of AU-011, each followed by laser light photoactivation. The large areas of necrotic tissue paired with the subsequent absence of tumor support the in vivo efficiency of the drug.

One of the more appealing aspects of the treatment described herein is its apparent specificity. Currently, in clinical practice, uveal melanoma is treated primarily via plaque radiotherapy, a treatment that involves suturing a radioactive plaque to the sclera in juxtaposition to the tumor. Although this treatment is effective for controlling tumor growth, it is nonspecific and results in potentially severe vision-threatening complications, including, but not limited to, glaucoma, radiation retinopathy, optic neuropathy, and cataract formation (40, 41). In our animal model, through detailed evaluation of histopathology sections, we noted clear evidence of retinal sparing both adjacent to, and overlying, treated tumors. It is our expectation that this will translate to better visual outcomes relative to plaque radiotherapy in the clinical setting.

This study is not without limitations. For instance, complications from the xenograft surgery (retinal detachment, hemorrhage, etc.) occasionally made it difficult to visualize the tumor by fundoscopy and thus, obtaining a consistent clinical history was not always possible. In addition, AU-011 treatment was assessed in xenograft models that utilize immunodeficient and immunosuppressed animals. The sustained immunosuppression required for the rabbit uveal melanoma model prevented long-term evaluation of the effects of AU-011 treatment given that animals cannot be treated with cyclosporine for long periods of time. Despite the eye generally being an immune privileged site, the choroid is highly vascularized, and so it is unclear to what extent a functioning immune system would affect tumor response. Ogawa and colleagues (7) have reported that IR700-mediated killing has the potential to create antitumor immunogenicity, which we have similarly observed in immunocompetent mouse models (unpublished observations). Finally, it was not always possible to photoactivate the AU-011 throughout the entire tumor, particularly if the tumor was anteriorly located. However, in a clinical setting, it is expected that the patient will be able to move their eye to allow for optimal viewing/lasering, thereby limiting this restriction.

As a proof-of-concept study, the degree of necrosis noted in large tumors in the treated animals, and in particular the complete responses observed in small melanomas, is a promising result that warrants continued clinical investigation. The intended primary target treatment of AU-011 would be small melanocytic lesions and small melanomas. On the basis of the tumor-specific nature of AU-011, this treatment might control the tumor while preserving vision for patients. It is possible that treating earlier melanocytic lesions in the eye may ultimately reduce the rate of metastasis and improve long-term survival outcomes.

In conclusion, our observations show that AU-011 has the potential to be an effective treatment for the primary treatment of uveal melanoma. AU-011 binds to uveal melanoma cells through heparan sulfate modifications on the cancer cell surfaces and upon activation with 690 nm light elicits potent and selective anticancer activity in vitro. In animal studies, AU-011 can be delivered throughout cancer tissue following both intravenous and intravitreal injection and activation by low intensity 690 nm laser results in a potent antitumor effect. Collectively, these studies lead us to conclude that AU-011 can have a profound targeted therapeutic effect resulting in dose-dependent tumor necrosis. Our data support the further clinical development of this novel therapeutic modality, as it has the potential to provide a first-line treatment option for early-stage uveal melanoma that could transform visual outcomes for patients with this rare but life-threatening disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All research was funded by Aura Biosciences. The authors would like to acknowledge the following: Laura Belen and Kortni Violette from ORA Inc. for development and expert execution of the rabbit orthotopic xenograft model of uveal melanoma; Drs. Hisataka Kobayashi and Yuko Nakamura for technical advice; and Dr. Patricia Day for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data for this article are available at Molecular Cancer Therapeutics Online (http://mct.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

R.C. Kines is a scientist at and has ownership interest (including patents) in Aura Biosciences. S. Spring is an associate scientist at Aura Biosciences. E. de los Pinos has ownership interest (including patents) in and has provided expert testimony for Aura Biosciences. J.T. Schiller has ownership interest (including patents) in a patent. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

References

- 1.Kines RC, Cerio RJ, Roberts JN, Thompson CD, de Los Pinos E, Lowy DR, et al. Human papillomavirus capsids preferentially bind and infect tumor cells. Int J Cancer 2016;138:901–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kines RC, Thompson CD, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, Day PM. The initial steps leading to papillomavirus infection occur on the basement membrane prior to cell surface binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:20458–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson KM, Kines RC, Roberts JN, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, Day PM. Role of heparan sulfate in attachment to and infection of the murine female genital tract by human papillomavirus. J Virol 2009;83:2067–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peng X, Draney DR, Volcheck WM, Bashford GR, Lamb DT, Grone DL, et al. Phthalocyanine dye as an extremely photostable and highly fluorescent near-infrared labeling reagent. In: Proceedings of the 97th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Optics and Photonics; 2006 Jan 21–26; San Jose, CA. Bellingham, WA: SPIE; 2006. Abstract nr 60970E. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitsunaga M, Ogawa M, Kosaka N, Rosenblum LT, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Cancer cell-selective in vivo near infrared photoimmunotherapy targeting specific membrane molecules. Nature Med 2011;17:1685–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sato K, Sato N, Xu B, Nakamura Y, Nagaya T, Choyke PL, et al. Spatially selective depletion of tumor-associated regulatory T cells with near-infrared photoimmunotherapy. Sci Transl Med 2016;8:352ra110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogawa M, Tomita Y, Nakamura Y, Lee MJ, Lee S, Tomita S, et al. Immunogenic cancer cell death selectively induced by near infrared photoimmunotherapy initiates host tumor immunity. Oncotarget 2017;8:10425–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato K, Watanabe R, Hanaoka H, Harada T, Nakajima T, Kim I, et al. Photoimmunotherapy: comparative effectiveness of two monoclonal antibodies targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Oncol 2014;8:620–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirasu N, Yamada H, Shibaguchi H, Kuroki M, Kuroki M. Potent and specific antitumor effect of CEA-targeted photoimmunotherapy. Int J Cancer 2014;135:2697–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakajima T, Sano K, Mitsunaga M, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Real-time monitoring of in vivo acute necrotic cancer cell death induced by near infrared photoimmunotherapy using fluorescence lifetime imaging. Cancer Res 2012;72:4622–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dougherty TJ, Gomer CJ, Henderson BW, Jori G, Kessel D, Korbelik M, et al. Photodynamic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:889–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoenfield L Uveal melanoma: a pathologist's perspective and review of translational developments. Adv Anat Pathol 2014;21:138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laver NV, McLaughlin ME, Duker JS. Ocular melanoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134:1778–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereira PR, Odashiro AN, Lim L-A, Miyamoto C, Blanco PL, Odashiro M, et al. Current and emerging treatment options for uveal melanoma. Clin Ophthalmol 2013;7:1669–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund RW. The collaborative ocular melanoma study, mortality by therapeutic approach, age and tumor size. J Insur Med 2013;43:221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. The COMS randomized trial of iodine 125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma: V. Twelve-year mortality rates and prognostic factors: COMS report No. 28. Arch Ophthalmol 2006;124:1684–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diener-West M, Reynolds SM, Agugliaro DJ, Caldwell R, Cumming K, Earle JD, et al. Development of metastatic disease after enrollment in the COMS trials for treatment of choroidal melanoma: collaborative ocular melanoma study group report No. 26. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:1639–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wen JC, Oliver SC, McCannel TA. Ocular complications following 1-125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma. Eye 2009;23:1254–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boldt HC, Melia BM, Liu JC, Reynolds SM, Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group. 1-125 brachytherapy for choroidal melanoma photographic and angiographic abnormalities: the collaborative ocular melanoma study: COMS Report No. 30. Ophthalmology 2009;116:106–15 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bianciotto C, Shields CL, Pirondini C, Mashayekhi A, Furuta M, Shields JA. Proliferative radiation retinopathy after plaque radiotherapy for uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology 2010;117:1005–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shields CL, Kaliki S, Furuta M, Fulco E, Alarcon C, Shields JA. American joint committee on cancer classification of uveal melanoma (anatomic stage) predicts prognosis in 7,731 patients: the 2013 Zimmerman Lecture. Ophthalmology 2015;122:1180–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shields JA, Shields CL. Management of posterior uveal melanoma: past, present, and future: the 2014 Charles L. Schepens lecture. Ophthalmology 2015;122:414–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shields CL, Furuta M, Thangappan A, Nagori S, Mashayekhi A, Lally DR, et al. Metastasis of uveal melanoma millimeter-by-millimeter in 8033 consecutive eyes. Arch Ophthalmol 2009;127:989–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleury MJJ, Touzé A, Coursaget P. Human papillomavirus type 16 pseudovirions with few point mutations in L1 major capsid protein FG loop could escape actual or future vaccination for potential use in gene therapy. Mol Biotechnol 2014;56:479–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buck CB, Thompson CD. Production of papillomavirus-based gene transfer vectors. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2007;37:26.1.1–.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Waard-Siebinga I, Blom DJ, Griffioen M, Schrier PI, Hoogendoorn E, Beverstock G, et al. Establishment and characterization of an uveal-melanoma cell line. Int J Cancer 1995;62:155–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanco PL, Marshall JC, Antecka E, Callejo SA, Souza Filho JP, Saraiva V, et al. Characterization of ocular and metastatic uveal melanoma in an animal model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005;46:4376–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esko JD, Stewart TE, Taylor WH. Animal cell mutants defective in glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1985;82:3197–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Day PM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Heparan sulfate-independent cell binding and infection with furin-precleaved papillomavirus capsids. J Virol 2008;82:12565–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L, Lawrence R, Frazier BA, Esko JD. CHO Glycosylation Mutants: Proteoglycans. Methods Enzymol 2006;416:205–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fornabaio M, Kim YS, Stackpole CW. Selective fractionation of hypoxic B16 melanoma cells by density gradient centrifugation. Cancer Lett 1989;44:185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selinka HC, Giroglou T, Nowak T, Christensen ND, Sapp M. Further evidence that papillomavirus capsids exist in two distinct conformations. J Virol 2003;77:12961–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knappe M, Bodevin S, Selinka HC, Spillmann D, Streeck RE, Chen XS, et al. Surface-exposed amino acid residues of HPV16 L1 protein mediating interaction with cell surface heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem 2007;282:27913–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smetsers TF, van de Westerlo EM, ten Dam GB, Clarijs R, Versteeg EM, van Geloof WL, et al. Localization and characterization of melanoma-associated glycosaminoglycans: differential expression of chondroitin and heparan sulfate epitopes in melanoma. Cancer Res 2003;63:2965–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bret C, Moreaux J, Schved J-F, Hose D, Klein B. SULFs in human neoplasia: implication as progression and prognosis factors. J Transl Med 2011;9:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torlakovic G, Grover VK, Torlakovic E. Easy method of assessing volume of prostate adenocarcinoma from estimated tumor area: using prostate tissue density to bridge gap between percentage involvement and tumor volume. Croat Med J 2005;46:423–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sano K, Nakajima T, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Markedly enhanced permeability and retention effects induced by photo-immunotherapy of tumors. ACS Nano 2013;7:717–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marshall J-CA, Fernandes BF, Di Cesare S, Maloney SC, Logan PT, Antecka E, et al. The use of a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor (Nepafenac) in an ocular and metastatic animal model of uveal melanoma. Carcinogenesis 2007;28:2053–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandes BF, Di Cesare S, Neto Belfort R, Maloney S, Martins C, Castiglione E, et al. Imatinib mesylate alters the expression of genes related to disease progression in an animal model of uveal melanoma. Anal Cell Pathol 2011;34:123–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacFaul PA, Bedford MA. Ocular complications after therapeutic irradiation. Br J Ophthalmol 1970;54:237–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Packer S Iodine-125 radiation of posterior uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology 1987;94:1621–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.