Abstract

Objectives

Adults’ perceptions of aging are known to affect their mental and physical health. However, not much is known about how perceptions of aging within the couple-unit affect each member of the unit. Therefore, the current study explores the effects of husbands’ and wives’ self-perceptions of aging (SPA) on each other’s physical and mental health, both directly and indirectly, through impacting each other’s SPA.

Method

The study used data from the Health and Retirement Study, focusing on couples aged 50 and older. Self-rated health and Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D) were used as indicators of physical and mental health. SPA was measured using the “Attitudes toward aging” subscale of the “Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale.” An actor–partner interdependence mediation model was used to examine the effects of the 2008 SPA of couples on each other’s 2012 SPA and 2016 health.

Results

The SPA of both husbands and wives was associated with their own future mental and physical health in 2016, but not with that of their partner. However, their SPA was associated with their partner’s health indirectly, by influencing the SPA of the partner. That is, the SPA of both husbands and wives in 2008 impacted their partner’s SPA in 2012, which was subsequently related to that partner’s mental and physical health in 2016.

Discussion

Older couples can influence each other’s health indirectly, by affecting each other’s SPA. This indicates that adults’ SPA are interconnected, and thus, the entire couple-unit should be targeted to enhance positive SPA.

Keywords: Depression, Longitudinal change, Marriage, Self-rated health

Beliefs about one’s own aging can have far-reaching consequences for the experiences of later-life in the domains of health, well-being, and longevity (Bellingtier & Neupert, 2016; Levy, Slade, & Kasl, 2002; Levy, Slade, Kunkel, & Kasl, 2002). Aging does not take place in isolation but is intertwined with other individuals, with partner relationships often being the closest and most meaningful relationship (Mejía & Hooker, 2015), whose importance can increase in later life (Lang, 2001). The health, well-being, and mental health of couples have been shown to be interrelated, and one person’s feelings and behaviors can propagate to his or her partner (Hoppmann & Gerstorf, 2009). However, the effects of adults’ aging perceptions on the health of their partners are not well-understood. The current study sets out to explore the effects of individuals’ self-perceptions of aging (SPA) on their partner’s mental and physical health. It also explores whether such a connection is mediated by the partner’s SPA.

SPA and Their Relationship With Physical and Mental Health

SPA indicate peoples’ attitudes toward their own aging, and are defined as the way people think about their own aging process and interpret age-related changes (Levy, Slade, Kunkel, & Kasl, 2002). They represent a well-known construct that has received substantial attention in the scientific literature, but also outside academia as a leading drive behind the recent World Health Organization campaign to combat ageism, given its real-life implications (Officer et al., 2016). This construct is often measured by the Attitudes Toward Own Aging subscale of the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale, which asks directly about perceived changes that occur with increasing age (e.g., changes in energy level). It differs from other constructs of subjective aging, such as subjective age, by being a relatively explicit assessment of individuals’ evaluation of their aging process (Ayalon, Palgi, Avidor, & Bodner, 2016). Specifically, there is ample research to show the direct association of SPA with the aging process, including health, physical functioning, and well-being (Levy, 2003; Sargent-Cox, Anstey, & Luszcz, 2012). For example, older individuals with more positive SPA, measured up to 23 years earlier, were found to live, on average, 7.5 years longer than those who had less positive SPA (Levy, Slade, Kunkel, & Kasl, 2002). Moreover, past research has shown that the way we think about our own aging impacts our ability to recover from disability so that those individuals who report more positive SPA show faster recovery (Levy, Slade, Murphy, & Gill, 2012). Better SPA has also been associated with lower rates of hospitalization (Sun, Kim, & Smith, 2017), a lower likelihood of falls (Ayalon, 2016) and better ability to perform activities of daily living (Moser, Spagnoli, & Santos-Eggimann, 2011).

SPA has an established role in relation to subjective physical health and mental health (Han & Richardson, 2015; Hicks & Siedlecki, 2017; Moor, Zimprich, Schmitt, & Kliegel, 2006). For instance, a study conducted in Germany, involving 362 community dwellers, showed that more positive SPA were associated with better subjective physical health (Moor, Zimprich, Schmitt, & Kliegel, 2006). A different study, focusing on American older adults, found that positive SPA were associated with less depressive symptoms 4 years later (Han & Richardson, 2015). Hence, no doubt, the concept of SPA deserves research and policy attention, given its important non-controversial impact on our physical and mental health.

The Importance of Couple Relationships for One’s Physical and Mental Health

The examination of the reciprocal effects of couples’ SPA in older adulthood is of special interest for several theoretical and practical reasons. First, according to the Socioemotional Selectivity Theory, older adults’ more limited time perspective prompts them to focus on emotionally gratifying relationships, rather than on those relationships that bear instrumental benefits (Carstensen, 2006; Lang & Carstensen, 2002). This, coupled with changes in life circumstances such as retirement and losses in one’s social network, may result in increased importance ascribed to the marital relationship. Spousal relationships are usually intimate in nature, accentuating the reciprocal effects of partners on one another (Hoppmann & Gerstorf, 2009).

The experiences of aging are largely intersubjective and are shaped by shared meanings and feedback from other persons. The linked lives principle holds that individuals’ lives are interdependently linked such that people’s experiences and perspectives frequently elicit changes in other people, as well (Settersten, 2015). Accordingly, the aging of close others often triggers awareness of one’s own aging (Settersten, Richard, & Hagestad, 2015). In particular, the perspectives and emotions of couples can be interrelated due to their centrality in each other’s lives and long history of joint experiences (Hoppmann & Gerstorf, 2009). Hence, individuals can internalize the aging perceptions of their partner, resulting in an impact on their own SPA.

Furthermore, partners’ perceptions of aging could affect one’s physical and mental health. Those partners who have more positive views on aging may show greater support in adoption of health-promoting behaviors, such as adhering to medical treatment, healthy diet or exercise, in order to jointly tackle health problems (Assad, Donnellan, & Conger, 2007; Stavrova, 2019). More positive views on aging might also affect the aging-related stress experienced within the family unit, creating a more favorable relational climate that ultimately reduces conflict and stress—both associated with physical and mental health (McEwen, 2005; Srivastava, McGonigal, Richards, Butler, & Gross, 2006).

Although previous studies have examined the role of actor’s psychosocial experiences for outcomes of physical and emotional health in the partner, the potential effect of the actor’s SPA on the partner are not well-understood. One study has examined SPA within the couple unit, focusing on the couple’s shared SPA (Mejía & Gonzalez, 2017). That study showed that couples who had more positive shared SPA also had less future functional limitations (Mejía & Gonzalez, 2017). Although informative, that study focused on the shared experiences of couples as a single construct and did not attempt to examine the separate effects of each actor on their partner. A different study has explicitly differentiated between the aging beliefs of both partners, focusing on older Malaysian couples, and found interdependence between actor’s attitudes towards aging and their partner’s well-being (Momtaz, Hamid, Masud, Haron, & Ibrahim, 2013). However, that study was conducted at one time point only. Thus, its findings could reflect the similarity of spouses, instead of a temporal dynamic. Furthermore, these results are limited to the realm of well-being, although aging perceptions might also be associated with physical health, based on numerous studies examining this at the individual level (Hicks & Siedlecki, 2017; Moor, Zimprich, Schmitt, & Kliegel, 2006). Therefore, the current study will explore the effects of older adults’ SPA on their partner’s future mental and physical health.

To sum, it is important to further assess the interdependence between couples given a substantial body of research that has shown that couples impact each other with regard to a variety of factors, including health and depression (Bakker, 2009; Kim, Chopik, & Smith, 2014; Kouros & Cummings, 2010). The current study will examine whether this interdependence extends to their aging perceptions. It will explore both the direct and the indirect pathway of associations between the SPA of actors and partners. Gender differences will also be considered, since social and subjective aging experiences are gendered (Kornadt, Voss, & Rothermund, 2013; Kouros & Cummings, 2010; Schwartz & Litwin, 2018; Settersten, Richard, & Hagestad, 2015). As SPA are potentially modifiable (Fernández-Ballesteros et al., 2013), this article is of utmost importance as it suggests future avenues for intervention. The current study will explore three hypotheses:

Actors’ SPA will be associated with their own future physical and mental health.

Actors’ SPA will be associated with the future physical and mental health of their partner.

Due to the interdependence of couples, the effects of actors’ SPA on the future physical and mental health of their partner will be mediated by an association with their partners’ SPA.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The HRS is a nationally representative longitudinal study of adults in the contiguous United States, aged 50 and older and their partners regardless of age, who are interviewed biennially. The main interview is conducted in a face-to-face format, followed by self-administered questionnaires. These self-administered “leave-behind” questionnaires obtain information about individuals’ psychosocial circumstances. This information is collected in each biennial wave from a rotating (random) 50% of the panel participants who completed the face-to-face interview. In 2008, the psychosocial questionnaire incorporated, for the first time, measures of SPA. The respondents who received this questionnaire in 2008 (T1) also received it in 2012 (T2) and 2016 (T3).

The current study focused on opposite-sex married partners who were aged 50 and older and in which both partners completed the psychosocial questionnaire in 2008. In 2008, 16,862 respondents over the age of 50 were interviewed face-to-face, out of which 6,947 completed the psychosocial questionnaire (85%). Out of them, 3,646 were living in the same household and married to a partner of the opposite sex, with both partners having filled the psychosocial questionnaire. This resulted in 1,823 couples being included in the current study. We conducted a selectivity analysis comparing the couples in this study to the couples that received the psychosocial questionnaire but did not complete it. This was done by creating a dummy variable, which was coded as 1 for completing the leave behind and using bivariate difference analyses with various socio-demographic and health variables. t-tests were conducted with continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Effect sizes were assessed using φ, Cramer’s V, and Cohen’s d for chi-square and t-tests, respectively. Small, medium, and large effects were considered for values of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5, respectively, for φ and Cramer’s V, and for values of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively, for Cohen’s d. The couples in this study differed (p < .05) from those who received the psychosocial questionnaire but did not complete it on several variables of interest: they perceived their health as better at T1 (Cohen’s d = 0.21 for wives, Cohen’s d = 0.13 for husbands); had fewer depressive symptoms (Cohen’s d = 0.22 for wives, Cohen’s d = 0.13 for husbands); and were more likely to be white (Cramer’s V = 0.16 for wives, Cramer’s V = 0.15 for husbands). They did not differ (p > .05) in terms of their age, education, and SPA. Effect sizes of the differences indicated a relatively weak selectivity effect (Baltes & Smith, 2003).

Table 1 includes descriptive statistics for the analytic sample. Participants’ age ranged between 50 and 95, with husbands being on average older than wives (average age of 70 vs 67). Husbands were also more educated, 48% of them reporting high education, compared to 44% of the wives. The sample was composed of 81% whites, 8% blacks, and 8% Hispanics. This was the first marriage for two-thirds of the sample, with an average marriage duration of 38 years.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics of the Study

| Variable | Wives | Husbands | t/χ 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 66.75 (8.74) | 69.80 (8.79) | −28.66*** |

| Education (high) | 44.0% | 48.1% | 332.23*** |

| Race | 3,435.27*** | ||

| Race (white) | 80.7% | 81.0% | |

| Race (black) | 8.1% | 8.4% | |

| Race (Hispanic) | 8.6% | 8.4% | |

| Race (Other) | 2.6% | 2.2% | |

| First marriage | 69.5% | 68.0% | 925.00*** |

| Mobility limitations | 1.03 (1.36) | 0.88 (1.33) | 3.87*** |

| Chronic conditions | 1.84 (1.24) | 2.11 (1.36) | −6.9*** |

| Self-rated health T1 | 3.27 (1.04) | 3.16 (1.09) | 3.62*** |

| Self-rated health T3 | 3.12 (1.02) | 3.06 (1.05) | 2.23* |

| Depression T1 | 1.18 (1.81) | 0.96 (1.56) | 4.1*** |

| Depression T3 | 1.27 (1.81) | 0.95 (1.50) | 4.19*** |

| SPA T1 | 4.02 (1.03) | 3.91 (1.04) | 4.24*** |

| SPA T2 | 3.89 (1.04) | 3.81 (1.00) | 3.62*** |

| Household level | |||

| Marriage duration | 38.38 (15.82) |

Note. SPA, self-perceptions of aging. Values are percentages or means (SD).

**p < .01, ***p < .001.

Measures

Physical and mental health

Physical health was measured as self-rated health, using a single question asking respondents to rate their health, from “excellent” (1) to “poor” (5). We recoded the answers such that a higher score indicated better-perceived health. Self-rated health is well established as a reliable predictor of functional impairment, morbidity, and mortality (Bond et al., 2006; Idler & Benyamini, 1997; Verropoulou, 2012). Number of depressive symptoms was assessed via the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). Due to interview time constraints, the HRS uses a shortened version of the CES-D, which includes eight items. The eight-item CES-D version has similar symptom dimensions as the original 20-item CES-D and high internal consistency and validity in the HRS (Wallace, Weir, Langa, Faul, & Fisher, 2000). Participants were asked whether they had (1) or had not (0) experienced any of eight symptoms “much of the time during the past week.” The scale measures the sum of these eight items, such that a higher score indicated more depressive symptoms (range: 0–8).

Self-perceptions of aging

Adults’ perceptions of their aging were assessed using 8 items based on the “Attitudes toward aging” subscale of the “Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale” (Liang & Bollen, 1983). This scale assesses participants’ positive and negative evaluation of their experiences of aging. It includes items such as “I have as much pep as I did last year,” “I am as happy now as I was when I was younger” and “The older I get, the more useless I feel.” Each item has response options ranging from “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly agree” (6). A rating of aging satisfaction was obtained by reverse coding negatively phrased items and averaging the scores across all eight items. The final score was set to missing if there were more than four items with missing values. The scale had good internal reliability for T1 (husbands α = 82; wives α = .81) and for T2 (husbands α: .81; wives α: .81).

Covariates

Age was measured as a continuous variable. Education distinguished between those with high-school education or less (0) and those with higher education (1). Race was divided into four categories: “white,” “black” (non-Hispanic blacks), “Hispanic” and “other.” First marriage was a dichotomous variable, receiving 1 if it was the respondent’s first marriage and 0 if there were previous marriages. Marriage duration was measured as the years of the current marriage. Mobility limitations was a count of difficulties experiences in five tasks: walking several blocks, walking one block, walking across the room, climbing several flights of stairs, and climbing one flight of stairs. It ranges between 0 and 5. Chronic conditions were a count of different conditions: high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer, lung disease, heart problems, stroke, and arthritis. This variable had a range of 0–7.

Statistical Analyses

We used the Actor–Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) that is widely used in the analysis of dyadic data to account for the interdependence of the partners in couples (Cook & Kenny, 2005). The APIM tests how one partner’s behaviors or characteristics influence the other partner’s outcomes (partner effects), above and beyond the effects of each partner’s behaviors and characteristics on his or her own outcomes (actor effects). The APIM is estimated using path analysis, as this method can model longitudinal mediation (Ledermann & Kenny, 2017). A longitudinal approach can reduce the risk of bias in estimating predictor–outcome associations at the same time point (Selig & Preacher, 2009).

To examine the direct effects of actors’ SPA on health, we estimated APIM models in which the SPA of each actor at T1 predicted the T3 self-rated health and depressive symptoms of that actor (first hypothesis) and of the partner (second hypothesis). These models were run twice, once without covariates and once with the covariates, such that the study variables were regressed on the baseline covariates while controlling for the depressive symptoms and self-rated health at T1. The third hypothesis of mediation was estimated using two APIM’s, the first did not include covariates and the second added the covariates. In each model, the self-rated health and depressive symptoms for both husbands and wives at T3 were predicted using the T1 SPA of actors and partners, mediated by their T2 SPA, while also controlling for their baseline self-rated health and depressive symptoms. All variables in the analyses were measured as observed variables. We compared the paths of interest for wives and husbands by comparing a freely estimated model to a model in which each actor’s path was constrained to be equal to that of the partner (Kline, 2011). A significant decline in model fit, were it to occur, would indicate the path coefficients to differ significantly between wives and husbands. The current study was not pre-registered in a repository.

We used the Lavaan package in R for model estimation (Rosseel, 2012). Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) was used to handle missing data. The models were run with a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR) to allow variables to deviate from multivariate normality. The use of MLR entailed adjustment of model comparisons to better approximate chi-square under non-normality (Satorra & Bentler, 2010). Model fit was evaluated primarily based on the criteria of comparative fit index (CFI) > .95, standardized root mean residual (SRMR) < .08, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < .08 (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, 2008).

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study sample. Wives rated their health as better than husbands, and perceived health deteriorated between T1 and T3 among both wives (t = −10.07, p < .001) and husbands (t = −10.56, p < .001). Wives reported more depressive symptoms compared to husbands, and depressive symptoms increased over time among both wives (t = 3.88, p < .001) and husbands (t = 3.14, p = .002). Wives rated their aging as more positive compared to husbands, and the SPA decreased among both wives (t = −10.05, p < .001) and husbands (t = −10.67, p < .001) between T1 and T2.

Table 2 presents Pearson correlations between the study variables of interest at baseline. Husbands’ and wives’ reports were correlated in terms of their self-rated health, their depressive symptoms scores, and their perceptions of aging. Positive perceptions of aging among wives were related to more positive self-rated health and to fewer depressive symptoms among husbands. Similarly, positive perceptions of aging among husbands were related to better self-rated health and lower depressive symptoms of wives.

Table 2.

Correlations Between the Study Characteristics at Baseline

| Self-rated health wives | Self-rated health husbands | Depressive symptoms wives | Depressive symptoms husbands | SPA wives | SPA husbands | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-rated health wives | - | 0.26*** | −0.44*** | −0.17*** | 0.54*** | 0.23*** |

| Self-rated health husbands | - | −0.15*** | −0.38*** | 0.26*** | 0.51*** | |

| Depressive symptoms wives | - | 0.22*** | −0.46*** | −0.19*** | ||

| Depressive symptoms husbands | - | −0.21*** | −0.41*** | |||

| SPA wives | - | 0.37*** | ||||

| SPA husbands | - |

Note. SPA, self-perceptions of aging.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

We examined the first and second hypotheses with a model in which the T1 SPA of each actor directly predicted the partner’s T3 self-rated health and depressive symptoms. This model was first examined without covariates, showing excellent fit to the data (χ 2 (30) = 1,585.41, p < .001, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00 [CI: 0.00–0.00], SRMR = 0.00). The direct effects between each actor’s T1 SPA and T3 health were significant, in accordance with the first hypothesis. However, the second hypothesis was not supported since the partner effects were not significant (not shown). In the second model, we added the covariates, showing excellent fit to the data (χ 2 (30) = 1,741.36, p < .001, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00 [CI: 0.00–0.00], SRMR = 0.00). In the model with covariates, we found a direct effect between the T1 SPA of each partner on his or her own T3 health, in accordance with the first hypothesis (Husband T1 SPA -> Husband T3 self-rated health: β = 0.08, p < .05; Husband T1 SPA -> Husband T3 depressive symptoms: β = −0.12, p < .01; Wife T1 SPA -> Wife T3 self-rated health: β = 0.16, p < .001; Wife T1 SPA -> Wife T3 depressive symptoms: β = −0.13, p = .001). However, we did not find support for the second hypothesis, as no direct effects were found between the SPA of individuals and the future health of their partner (Husband T1 SPA -> Wife T3 self-rated health: β = −0.02, p > .05; Husband T1 SPA -> Wife T3 depressive symptoms: β = 0.02, p > .05; Wife T1 SPA -> Husband T3 self-rated health: β = 0.02, p > .05; Wife T1 SPA -> Husband T3 depressive symptoms: β = −0.01, p > .05).

We proceeded to examine the mediation hypothesis with an APIM that predicted self-rated health and depressive symptoms at T3 using actor and partner SPA, without including covariates. The model showed good fit to the data (χ 2 (51) = 2,924.82, p < .001, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03 [CI: 0.01–0.04], SRMR = 0.01). For both wives and husbands, actor’s SPA at T1 had a positive association with the partner’s SPA at T2. The SPA of each partner at T2 were positively associated with the self-rated health of that individual T3 and was negatively associated with the partner’s depressive symptoms at T3. Thus, in accordance with the third hypothesis, actor’s SPA were indirectly associated with their partner’s physical and mental health, by being related to the partner’s SPA. However, no direct effects were seen between actor’s SPA at T2 and each partner’s self-rated health or depressive symptoms at T3. The main paths of interest are presented in Table 3. Analyses of the indirect effects showed that this effect was significant for the effects of wives on husbands’ self-rated health (B (SE) = 0.02 (0.01), p = .007) and on husbands’ depressive symptoms (B (SE) = −0.03 (0.01), p = .008). This effect was also significant for the effects of husbands on wives’ self-rated health (B (SE) = 0.02 (0.01), p = .005) and on wives’ depressive symptoms (B (SE) = −0.02 (0.01), p = .008).

Table 3.

Longitudinal APIM Model of Couples’ SPA, Self-Rated Health, and Depressive Symptoms

| Regression path | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | B | B (SE) | B | |

| Wives | ||||

| SPA actor T1 → SPA partner T2 | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.08** | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.06* |

| SPA actor T1 → SPA actor T2 | 0.55 (0.03) | 0.55*** | 0.51 (0.03) | 0.50*** |

| SPA actor T2 → Self-rated health partner T3 | 0.02 (0.03) | 0.02 | 0.03 (0.03) | 0.02 |

| SPA actor T2 → Depressive symptoms partner T3 | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.01 | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 |

| SPA partner T2 → Self-rated health partner T3 | 0.27 (0.03) | 0.25*** | 0.25 (0.03) | 0.23*** |

| SPA partner T2 → Depressive symptoms partner T3 | −0.34 (0.05) | −0.22*** | −0.34 (0.05) | −0.22*** |

| Husbands | ||||

| SPA actor T1 → SPA partner T2 | 0.08 (0.03) | 0.07** | 0.07 (0.03) | 0.07** |

| SPA actor T1 → SPA actor T2 | 0.53 (0.03) | 0.54*** | 0.50 (0.03) | 0.51*** |

| SPA actor T2 → Self-rated health partner T3 | −0.03 (0.03) | −0.03 | −0.02 (0.03) | −0.02 |

| SPA actor T2 → Depressive symptoms partner T3 | −0.03 (0.06) | −0.02 | −0.05 (0.06) | −0.03 |

| SPA partner T2 → Self-rated health partner T3 | 0.26 (0.03) | 0.26*** | 0.24 (0.03) | 0.24*** |

| SPA partner T2 → Depressive symptoms partner T3 | −0.29 (0.06) | −0.16*** | −0.27 (0.06) | −0.15*** |

Note. APIM, Actor–Partner Interdependence Model; SPA, self-perceptions of aging. Model 1 doesn't include covariates. Model 2 controls for both partners’ age, education, race–ethnicity, first marriage, mobility limitations, marriage duration, self-rated health, and depressive symptoms.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

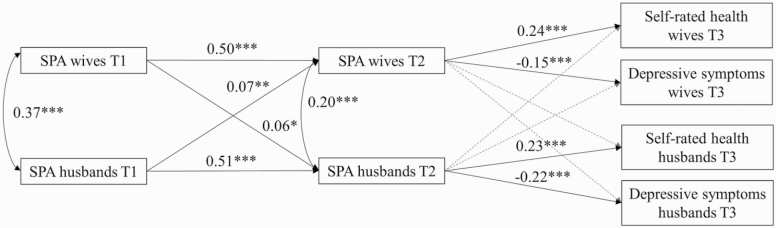

We further tested the mediation hypothesis by adding the covariates to the model, which showed good fit to the data (χ 2 (153) = 3,461.45, p < .001, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.02 [CI: 0.00–0.04], SRMR = 0.01). As seen in the model without the covariates, for both husbands and wives, actor’s SPA at T1 had a positive association with the partner’s SPA at T2. The T2 SPA of the partners were positively associated with their own T3 self-rated health and negatively associated with their depressive symptoms scores at T3, while actor’s SPA at T2 was not associated with the partner’s self-rated health or depressive symptoms at T3. Thus, in accordance with the third hypothesis, actor’s SPA were related to their partner’s health indirectly, by being linked with the partner’s SPA, after the inclusion of the covariates. The main paths of analysis are presented in Table 3 and Figure 1, and the full model, including the covariates is presented as Supplementary Table 1. Analyses of the indirect effects showed that this effect was significant for wives’ indirect effects on their husbands’ self-rated health (B (SE) = 0.02 (0.01), p = .035). There was also an indirect effect on husbands’ depressive symptoms (B (SE) = −0.02 (0.01), p = .037). Husbands’ SPA also had an indirect effect on wives’ self-rated health (B (SE) = 0.02 (0.01), p = .012). A similar pathway was found for their effect on wives’ depressive symptoms (B (SE) = −0.02 (0.01), p = .020).

Figure 1.

Longitudinal Actor–Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) model of couples’ self-perceptions of aging (SPA), self-rated health, and depressive symptoms. Note. The model controls for both partners’ age, education, race–ethnicity, first marriage, mobility limitations, marriage duration, self-rated health, and depressive symptoms. Paths present standardized coefficients; dotted paths are non-significant; covariances between cross-sectional actor and partner variables at T3 are omitted for clarity; *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Since the paths from individuals’ SPA to their partner’s SPA were significant for both husbands and wives, we tested these paths for equality. We did this by constraining the paths between husbands’ T1 SPA to their partner’s T2 SPA to be equal to the parallel path from wives’ T1 SPA to the T2 SPA of their husband. Comparing this model to the model in which these two paths were freely estimated did not result in a significant decline in model fit (χ 2(1) = 0.01, p = .93), indicating that the partner effects of SPA were similar among husbands and wives.

The present study used a measure of SPA, which includes items such as “Do you have as much pep as you had last year?” and “Are you as happy now as you were when you were younger?.” Hence, there is a possibility that these items are conceptually similar to the outcome variables of self-rated health and depressive symptoms. Thus, we ran additional analyses (not shown) in which we excluded these two items from the SPA measure. This analysis showed a similar trend of results, such that the SPA of older adults was related to their partner’s depressive symptoms and self-rated health via the SPA of that partner. This strengthens the premise that SPA is conceptually different from the outcome health variables.

Discussion

The present study examined the temporal associations of individuals’ SPA with their partner’s mental and physical health, which were measured as self-rated health and depressive symptoms. No direct effects were found, as the SPA of each person was only associated with his or her own future mental and physical health, but not with the health of their partner. However, the results showed an indirect effect, such that the SPA of older adults was related to their partner’s health via the SPA of that partner. The SPA of husbands and wives was associated with the SPA of their partner four years later, and the SPA of that partner was subsequently related to his or her future mental and physical health. Thus, the current study sheds light on the social consequences of adults’ aging perceptions and their implications for couple relationships.

The findings of an indirect effect, in accordance with our third hypothesis, can suggest that individuals’ SPA contributes to the SPA of their partner in a process of contagion. Such effects are in line with the linked-lives principle (Settersten, 2015) as they highlight the dynamic interdependence of aging couples. These results highlight a significant social source of influence on one’s aging perceptions—the way one’s partner perceives his or her own aging. The longitudinal findings further indicate that the cross-sectional associations between couples’ SPA do not only represent assortative mating (e.g., self-selection), rather there is a dynamic process of transactions between couples’ aging perceptions. Such processes are particularly meaningful as they are consequently related to the future mental and physical health of older individuals.

These results show that adults’ SPA is embedded in a social context and affected by the way close others perceive their own aging process. As adults spend much time with their partner, they might have frequent exposure to his or her outlook regarding aging and can internalize these perceptions (Levy, 2009). For example, having a partner that perceives retirement as a positive opportunity can make one perceive his or her own aging in a similar manner and act in a way that makes the most of such a change. Additionally, the aging perceptions of individuals might extend to their partners by encouraging actions that improve the aging of that partner. For instance, individuals with more positive aging perceptions might generate a more positive atmosphere at home and be nicer to their partner (Santini, Koyanagi, Tyrovolas, Haro, & Koushede, 2017), which can result in a more positive evaluation of aging by that partner. They might also initiate joint activities with their partner, including interactions with friends and involvement in organizations (Menkin, Robles, Gruenewald, Tanner, & Seeman, 2017; Schwartz, Ayalon, & Huxhold, 2020), as well as engaging in health behaviors such as eating a balanced diet and exercising (Levy & Myers, 2004; Li, Cardinal, & Acock, 2013). Such behaviors can improve the SPA of their partner, especially if they are counteractive to the negative stereotypes of older adults as feeble and passive (Levy, 2009).

Adults’ SPA was not found to be directly related to the mental or physical health of their partner, in contrast to our second hypothesis. Thus, it seems that the effects of adults’ SPA do not directly extend to their partner’s health. We note that we found significant cross-sectional correlations between actors’ SPA and their partner’s physical and mental health, similar to a previous investigation (Momtaz, Hamid, Masud, Haron, & Ibrahim, 2013). However, no longitudinal effects were found, indicating the importance of examining these effects over time. It might be possible that people with positive SPA and better health are more likely to be a couple. However, the lack of longitudinal findings suggests that this association does not represent a temporal relationship.

The current study has several strengths, including its large sample, use of three waves of data and examination of how SPA contributes to dyadic health. However, some limitations should be noted. The observed relations between couples’ SPA and health over time may be attributable to a third variable not assessed in this study. For example, individuals who are more optimistic may perceive their aging as better, and their optimism might be linked with improvements in their partner’s SPA. Examining this option would extend beyond the scope of the current study, which focused on dyadic processes related to health outcomes. This prospect could be explored in future studies. Additionally, this study focused on opposite-sex couples. There was a small number of same-sex couples interviewed in the HRS, which did not permit an analysis of opposite-sex couples. However, it is important to understand the interdependence of same-sex older couples as they might differ in their needs and dynamics (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). Future research could extend the current investigation to same-sex older couples, to gain meaningful insights regarding their SPA and health. Additionally, it should be noted that some respondents were not included in the final analysis due to not filling the psychosocial questionnaire and they differed in several attributes from those participants who were eventually included. Thus, this slightly limits the generalizability of findings to adults who are relatively healthy.

Nonetheless, the current study showed that the SPA of older adults predicted the mental and physical health of their partner indirectly, via an association with that partner’s SPA over time. It indicates that the way adults perceive their aging does not only contribute to their own health and well-being, but extends to their close social ties, ultimately having implications for the health and well-being of their partner. Greater understanding of how spouses contribute to and promote positive health and well-being in each other is an important addition of this study and should be further expanded in future research. Practitioners working with older couples should thus pay attention to the dyadic perceptions of aging, as even improving one partner’s perceptions might result in positive consequences for both partners.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Our study is a secondary analysis of existing data from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Data files and documentation are for public use and available at http://hrs.isr.umich.edu.

Funding

The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- Assad, K. K., Donnellan, M. B., & Conger, R. D. (2007). Optimism: An enduring resource for romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(2), 285–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L. (2016). Satisfaction with aging results in reduced risk for falling. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(5), 741–747. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215001969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L., Palgi, Y., Avidor, S., & Bodner, E. (2016). Accelerated increase and decrease in subjective age as a function of changes in loneliness and objective social indicators over a four-year period: Results from the health and retirement study. Aging & Mental Health, 20(7), 743–751. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1035696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. B. (2009). The crossover of burnout and its relation to partner health. Stress and Health, 25(4), 343–353. doi: 10.1002/smi.1278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, P. B., & Smith, J. (2003). New frontiers in the future of aging: From successful aging of the young old to the dilemmas of the fourth age. Gerontology, 49(2), 123–135. doi: 10.1159/000067946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellingtier, J. A., & Neupert, S. D. (2016). Negative aging attitudes predict greater reactivity to daily stressors in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(7), 1155–1159. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond, J., Dickinson, H. O., Matthews, F., Jagger, C., & Brayne, C.; MRC CFAS . (2006). Self-rated health status as a predictor of death, functional and cognitive impairment: A longitudinal cohort study. European Journal of Ageing, 3(4), 193–206. doi: 10.1007/s10433-006-0039-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science (New York, N.Y.), 312(5782), 1913–1915. doi: 10.1126/science.1127488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, W. L., & Kenny, D. A. (2005). The actor-partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(2), 101–109. doi: 10.1080/01650250444000405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ballesteros, R., Caprara, M., Schettini, R., Bustillos, A., Mendoza-Nunez, V., Orosa, T.,…Zamarrón, M. D. (2013). Effects of university programs for older adults: Changes in cultural and group stereotype, self-perception of aging, and emotional balance. Educational Gerontology, 39(2), 119–131. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2012.699817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., & Kim, H. (2017). The science of conducting research with LGBT older adults- an introduction to aging with pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS). The Gerontologist, 57(S1), S1–S14. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, J., & Richardson, V. E. (2015). The relationships among perceived discrimination, self-perceptions of aging, and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of age discrimination. Aging & Mental Health, 19(8), 747–755. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.962007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, S. A., & Siedlecki, K. L. (2017). Leisure activity engagement and positive affect partially mediate the relationship between positive views on aging and physical health. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(2), 259–267. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. www.ejbrm.com [Google Scholar]

- Hoppmann, C., & Gerstorf, D. (2009). Spousal interrelations in old age–a mini-review. Gerontology, 55(4), 449–459. doi: 10.1159/000211948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler, E. L., & Benyamini, Y. (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E. S., Chopik, W. J., & Smith, J. (2014). Are people healthier if their partners are more optimistic? The dyadic effect of optimism on health among older adults. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 76(6), 447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.03.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (Third). The Guilford Press. doi: 10.1038/156278a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kornadt, A. E., Voss, P., & Rothermund, K. (2013). Multiple standards of aging: Gender-specific age stereotypes in different life domains. European Journal of Ageing, 10(4), 335–344. doi: 10.1007/s10433-013-0281-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros, C. D., & Cummings, E. M. (2010). Longitudinal associations between Husbands’ and Wives’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72(1), 135–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00688.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, F. R. (2001). Regulation of social relationships in later adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(6), P321–P326. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.p321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, F. R., & Carstensen, L. L. (2002). Time counts: Future time perspective, goals, and social relationships. Psychology and Aging, 17(1), 125–139. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.17.1.125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann, T., & Kenny, D. A. (2017). Analyzing dyadic data with multilevel modeling versus structural equation modeling: A tale of two methods. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP, 31(4), 442–452. doi: 10.1037/fam0000290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. R. (2003). Mind matters: Cognitive and physical effects of aging self-stereotypes. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(4), P203–P211. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.4.P203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. (2009). Stereotype embodiment: A psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(6), 332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. R., & Myers, L. M. (2004). Preventive health behaviors influenced by self-perceptions of aging. Preventive Medicine, 39(3), 625–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., & Kasl, S. V. (2002). Longitudinal benefit of positive self-perceptions of aging on functional health. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(5), P409–P417. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.5.p409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., Kunkel, S. R., & Kasl, S. V. (2002). Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(2), 261–270. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., Murphy, T. E., & Gill, T. M. (2012). Association between positive age stereotypes and recovery from disability in older persons. JAMA, 308(19), 1972–1973. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, K. K., Cardinal, B. J., & Acock, A. C. (2013). Concordance of physical activity trajectories among middle-aged and older married couples: Impact of diseases and functional difficulties. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(5), 794–806. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J., & Bollen, K. A. (1983). The structure of the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale scale: a reinterpretation. Journal of Gerontology, 38(2), 181–189. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.2.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B. S. (2005). Stressed or stressed out: What is the difference? Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience: JPN, 30(5), 315–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, S. T., & Gonzalez, R. (2017). Couples’ shared beliefs about aging and implications for future functional limitations. The Gerontologist, 57(S2), 149–159. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, S. T., & Hooker, K. (2015). Emotional well-being and interactions with older adults’ close social partners: Daily variation in social context matters. Psychology and Aging, 30(3), 517–528. doi: 10.1037/a0039468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menkin, J. A., Robles, T. F., Gruenewald, T. L., Tanner, E. K., & Seeman, T. E. (2017). Positive expectations regarding aging linked to more new friends in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(5), 771–781. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbv118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momtaz, Y. A., Hamid, T. A., Masud, J., Haron, S. A., & Ibrahim, R. (2013). Dyadic effects of attitude toward aging on psychological well-being of older Malaysian couples: An actor-partner interdependence model. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 8, 1413–1420. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S51877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moor, C., Zimprich, D., Schmitt, M., & Kliegel, M. (2006). Personality, aging self-perceptions, and subjective health: A mediation model. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 63(3), 241–257. doi: 10.2190/AKRY-UM4K-PB1V-PBHF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser, C., Spagnoli, J., & Santos-Eggimann, B. (2011). Self-perception of aging and vulnerability to adverse outcomes at the age of 65 – 70 years. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(6), 675–680. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Officer, A., Schneiders, M. L., Wu, D., Nash, P., Thiyagarajan, J. A., & Beard, J. R. (2016). Valuing older people: Time for a global campaign to combat ageism. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 94(10), 710–710A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.184960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santini, Z. I., Koyanagi, A., Tyrovolas, S., Haro, J. M., & Koushede, V. (2017). The association of social support networks and loneliness with negative perceptions of ageing: Evidence from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Ageing and Society, 1–21. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X17001465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent-Cox, K. A., Anstey, K. J., & Luszcz, M. A. (2012). The relationship between change in self-perceptions of aging and physical functioning in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 27(3), 750–760. doi: 10.1037/a0027578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2010). Ensuring positiveness of the scaled difference Chi-square test statistic. Psychometrika, 75(2), 243–248. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, E., Ayalon, L., & Huxhold, O. (2020). Exploring the reciprocal associations of perceptions of aging and social involvement. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(3), 563–573. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, E., & Litwin, H. (2018). Social network changes among older Europeans: The role of gender. European Journal of Ageing, 15(4), 359–367. doi: 10.1007/s10433-017-0454-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig, J. P., & Preacher, K. J. (2009). Mediation models for longitudinal data in developmental research. Research in Human Development, 6(2–3), 144–164. doi: 10.1080/15427600902911247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten, R. A. (2015). Relationships in time and the life course: The significance of linked lives. Research in Human Development, 12(3–4), 217–223. doi: 10.1080/15427609.2015.1071944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Settersten, J., Richard, A., & Hagestad, G. O. (2015). Subjective aging and new complexities of the life course. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 35(1), 29–53. doi: 10.1891/0198-8794.35.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S., McGonigal, K. M., Richards, J. M., Butler, E. A., & Gross, J. J. (2006). Optimism in close relationships: How seeing things in a positive light makes them so. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(1), 143–153. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavrova, O. (2019). Having a happy spouse is associated with lowered risk of mortality. Psychological Science, 30(5), 798–803. doi: 10.1177/0956797619835147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. K., Kim, E. S., & Smith, J. (2017). Positive self-perceptions of aging and lower rate of overnight hospitalization in the US population over age 50. Psychosomatic Medicine, 79(1), 81–90. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verropoulou, G. (2012). Determinants of change in self-rated health among older adults in Europe: A longitudinal perspective based on SHARE data. European Journal of Ageing, 9(4), 305–318. doi: 10.1007/s10433-012-0238-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, R. B., Weir, D. R., Langa, K. M., Faul, J. D., & Fisher, G. G. (2000). Documentation of Affective Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Retrieved from hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg/dr-009.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.