Introduction

Emmonsia species are dimorphic fungi, which can cause human disease through inhalation of airborne conidia from soil. They convert into yeast-like cells, which replicate and cause extra-pulmonary disease via hematological dissemination. Individuals with impaired cell-mediated immunity, such as those with HIV or transplant patients on immunosuppressive therapies, are more commonly infected. The majority of infected individuals present with respiratory symptoms and a widespread rash. More than 60 patients with Emmonsia species infections have been reported in South Africa, with the majority in the past 10 years; all but a few patients had HIV.1 Few cases have been reported from other countries. In these patients HIV was not ubiquitous, but rather many cases were in patients on immunosuppressive medications.2, 3, 4, 5 Herein, we describe a case of Emmonsia in Canada diagnosed at the patient's presentation to dermatology with a solitary facial nodule.

Case description

A 52-year-old renal transplant recipient presented to the dermatology clinic for a solitary, asymptomatic nodule on the right oral commissure. The nodule had been present for 8 weeks, grown rapidly from 2 to 12 mm in diameter, and had become ulcerated. The patient was systemically well with no fevers, night sweats, chills, or weight loss. His review of systems was otherwise unremarkable, including absence of respiratory symptoms.

The patient was born in Saskatchewan, Canada, and had not traveled outside of North America. He had no prior history of fungal infections and was not aware of personal contact with an affected individual. He worked as a dispatcher in Alberta and had no significant soil exposure. His past medical history was significant for end-stage renal disease from chronic glomerulonephritis. At the time of presentation, he was on peritoneal dialysis after a failed cadaveric renal transplant. The patient was immunosuppressed with prednisone 7.5 mg daily, tacrolimus 5.5 mg daily, and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg twice daily, while awaiting a second renal transplant.

Physical examination revealed a 12-mm exophytic nodule with central ulceration on the right oral commissure (Fig 1). No enlarged lymph nodes were observed in the cervical, posterior auricular, preauricular, submandibular, submental, supraclavicular, or axillary regions. The remainder of his mucocutaneous examination was unremarkable. The differential diagnosis included a deep fungal or mycobacterial infection, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and cutaneous metastasis.

Fig 1.

Cutaneous Emmonsia species ulcerated nodule at the right oral commissure in a Canadian renal transplant recipient.

Punch biopsies of the lesion were performed for histology, fungal, and mycobacterial culture. Routine histology revealed a diffuse mixed inflammatory infiltrate and numerous unicellular, oval, budding forms consistent with small yeasts (Fig 2). Structures consistent with pseudohyphae were also noted. The organisms were highlighted with Periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott's methenamine silver special stain (Fig 3), but not with Warthin-Starry or Ziehl-Neelsen special stain.

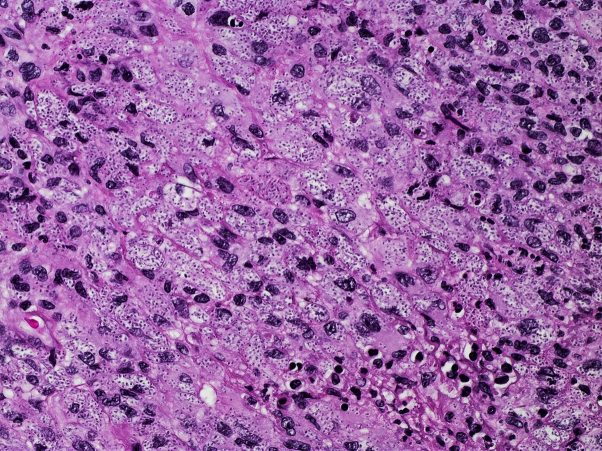

Fig 2.

Histology revealed a diffuse mixed inflammatory infiltrate and numerous unicellular, oval, budding forms consistent with small yeasts (original magnification, ×400).

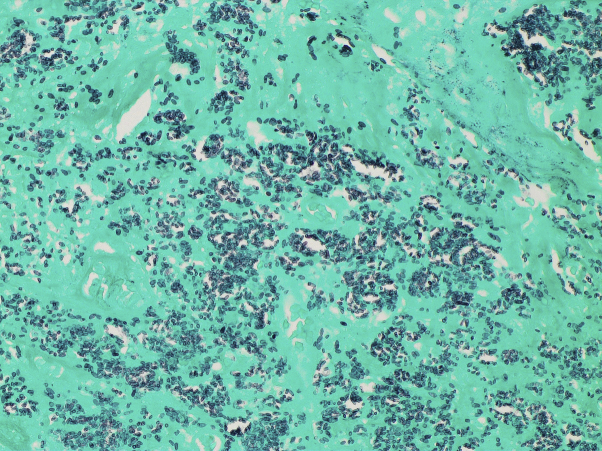

Fig 3.

Emmonsia species were highlighted with the Grocott methenamine silver stain (original magnification, ×400).

While awaiting culture results, the patient was admitted for pleuritic chest pain. A chest computed tomography scan revealed numerous bilateral pulmonary nodules with a cavitary mass in the left lower lobe. Cultures from the skin and lung grew Emmonsia species on inhibitory mold agar and blood and chocolate agar, respectively. DNA sequencing of the beta-tubulin gene and the internal transcribed spacer region of ribosomal genes performed by the Alberta Health Services Public Health Laboratory confirmed the diagnosis of Emmonsia species. The patient was started on treatment with amphotericin B 300 mg intravenously 5 days per week, and his immunosuppressive medications were discontinued. After 2 months of treatment, his lip lesion had decreased in size to 4 mm.

The patient's course was complicated by an aspiration pneumonia secondary to bronchoscopy, which progressed to a bronchopleural fistula. Three months into the amphotericin B treatment, he remained clinically stable, although chest imaging suggested worsening pulmonary disease. Despite treatment with micafungin 100 mg administered intravenously daily and orally administered posaconazole 300 mg daily, the patient clinically deteriorated. He developed adrenal insufficiency unresponsive to steroids, an ileus, and a drug-related pancreatitis. He ultimately passed away a few weeks after these complications.

Discussion

Over the years, the classification of Emmonsia species has undergone multiple taxonomic revisions. Initially included in the family Ajellomyceteae, Emmonsia was recently reclassified into the new genus Emergomyces, which contains 5 reported species.6 Affected patients are usually immunosuppressed, have respiratory symptoms, and often develop disseminated cutaneous lesions. Our case from North America is one of the few to describe an Emmonsia infection presenting as a solitary, cutaneous nodule in the absence of respiratory symptoms. Furthermore, the patient was HIV-negative, but on immunosuppressive therapies for his renal transplant.

In a cohort of South-African patients, cutaneous Emmonsia species infections were often misdiagnosed as entities such as varicella, drug reactions, and Kaposi sarcoma.1 Therefore, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion in at-risk populations and perform biopsies for both pathology and tissue culture. Patients treated with biologic therapies represent a new population at risk for disseminated fungal infections. For instance, histoplasmosis infections come second only to Staphylococcus aureus for patients on tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors in areas endemic for Histoplasma.7 Furthermore, multiple Talaromyces marneffei infections have been reported in patients from Hong Kong who were treated with kinase inhibitors.8 Dermatologists should counsel patients on their increased risk of fungal infections, including Emmonsia species, when initiating immunosuppressive and/or biologic therapies in patients living in endemic areas, in those traveling to endemic areas, or in patients with additional co-morbidities.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

Patient consent was obtained.

References

- 1.Schwartz I.S., Govender N.P., Corcoran C. Clinical characteristics, diagnosis, mangement, and outcomes of disseminated emmonsiosis: a retrospective case series. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(6):1004–1012. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang X.H., Zhou H., Zhang X.Q., Han J.D., Gao Q. Cutaneous disseminated emmonsiosis due to Emmonsia pasteuriana in a patient with cytomegalovirus enteritis. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(11):1263–1264. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng P., Yin S., Zhu G. Disseminated infection caused by Emmonsia pasteuriana in a renal transplant recipient. J Dermatol. 2015;42(12):1179–1182. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kappagoda S., Adams J.Y., Luo R., Banaei N., Concepcion W., Ho D.Y. Fatal Emmonsia sp. infection and fungemia after orthotopic liver transplantation. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(2):346–349. doi: 10.3201/eid2302.160799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz I.S., Sanche S., Wiederhold N.P., Patterson T.F., Sigler L. Emergomyces canadensis a dimorphic fungus causing fatal systemic human disease in North America. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(4):758–761. doi: 10.3201/eid2404.171765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz I.S., Govender N.P., Sigler L. Emergomyces: the global rise of new dimorphic fungal pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(9):e1007977. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvana E.M.T., Salata R.A. Infectious complications associated with monoclonal antibodies and related small molecules. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22(2):274–290. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00040-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan J.F.W., Chan T.S.Y., Gill H. Disseminated infections with Talaromyces marneffei in non-AIDS patients given monoclonal antibodies against CD20 and kinase inhibitors. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(7):1101–1106. doi: 10.3201/eid2107.150138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]