Abstract

The continued expansion of the genome editing toolbox necessitates methods to characterize important properties of these enzymes. One such property is the requirement of CRISPR-Cas proteins to recognize a protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) in DNA target sites. The high-throughput PAM determination assay (HT-PAMDA) is a method that enables scalable characterization of the PAM preferences of different Cas proteins. Here, we provide a step-by-step protocol for the method, discuss experimental design considerations, and highlight how the method can be used to profile naturally occurring CRISPR-Cas9 enzymes, engineered derivatives with improved properties, orthologs of different classes (e.g. Cas12a), and even different platforms (e.g. base editors). A distinguishing feature of HT-PAMDA is that the enzymes are expressed in a cell type or organism of interest (e.g. mammalian cells), permitting scalable characterization and comparison of hundreds of enzymes in a relevant setting unlike previously available assays. HT-PAMDA does not require specialized equipment or expertise and is cost-effective for multiplexed characterization of many enzymes. The protocol enables comprehensive PAM characterization of dozens or hundreds of Cas enzymes in parallel in less than two weeks.

Keywords: CRISPR-Cas, protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), genome editing, protein engineering, HT-PAMDA

Introduction

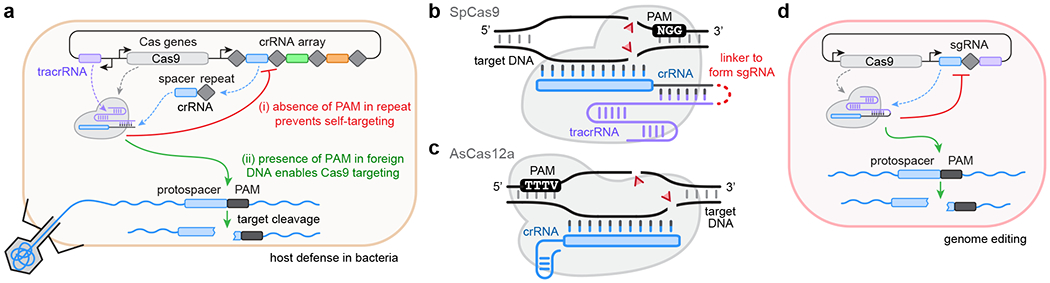

The adaptation of CRISPR-Cas enzymes for genome engineering applications has had a transformational impact on biomedical research. The number of CRISPR-based technologies with different capabilities is rapidly expanding through the discovery of naturally occurring type II (Cas9) and type V (Cas12) orthologs and the engineering of enzymes with improved properties1,2. One critical property of these DNA-targeting Cas enzymes is the necessity to recognize a protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) in their target site3. This requirement fulfills an important biological role, enabling the CRISPR immune system to differentiate self from invading DNA (Fig. 1a)4. For genome editing applications, the PAM of a Cas protein dictates which genomic sites are accessible to the enzyme Fig. 1b,c). A major bottleneck in the identification or engineering of CRISPR enzymes with unique PAM requirements is the need for scalable experimental methods to characterize PAM preferences in biologically relevant settings. Here, we provide a detailed experimental protocol and steps for analyzing data with HT-PAMDA, a scalable assay to investigate the PAM profiles hundreds of Cas enzymes5. Beyond understanding the targeting ranges of Cas enzymes, the HT-PAMDA workflow should be adaptable for scalable characterization of other important properties of CRISPR enzymes including their activities, specificities, guide RNA (gRNA) requirements, and others. For both naturally occurring and optimized enzymes, thorough characterization of the properties of these engineered tools is essential for understanding and benchmarking their performance for genome editing applications (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1. |. The role of the PAM for host defense and genome editing.

a, Recognition of the PAM by Cas enzymes permits CRISPR systems to (i) distinguish between self and non-self to prevent self-targeting, and (ii) surveil and cleave foreign nucleic acids. b, Schematic of SpCas9 (grey) bound to its guide RNA (gRNA). The gRNA is comprised of a crRNA (with spacer and repeat in blue and grey, respectively) and tracrRNA (in purple); these two RNA components can be joined by a synthetic linker to form a single guide RNA (sgRNA). Once complexed with the gRNA, the Cas-gRNA RNP can scan DNA targets for the presence of PAMs, a 3’-NGG sequence for SpCas9, to initiate DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs; red triangles). c, Schematic of AsCas12a (grey) bound to its crRNA. In comparison to SpCas9, AsCas12a does not require a tracrRNA and recognizes a 5’-TTTV PAM; like SpCas9, the Cas12a-crRNA RNP complex scans DNA targets for PAMs to initiate DSBs. d, In genome editing applications, Cas enzymes and their gRNAs are co-expressed to perform PAM-dependent DNA targeting events.

Development of the protocol

HT-PAMDA was developed to eliminate the bottleneck of enzyme characterization in projects that seek to discover or engineer new Cas variants. We recently utilized HT-PAMDA as part of a protein engineering pipeline to improve the targeting range of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9) by relaxing its NGG PAM requirement, resulting in the SpCas9 variants named SpG and SpRY, that require minimal NGN and NRN>NYN PAMs, respectively5. HT-PAMDA played an integral role in this study, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the impact of single amino acid changes on the PAM preferences of intermediate enzymes during their engineering trajectories. The scalability of HT-PAMDA permitted the exploration of a larger variant space than previously achieved, producing complete PAM profiles for more than one hundred SpCas9 variants.

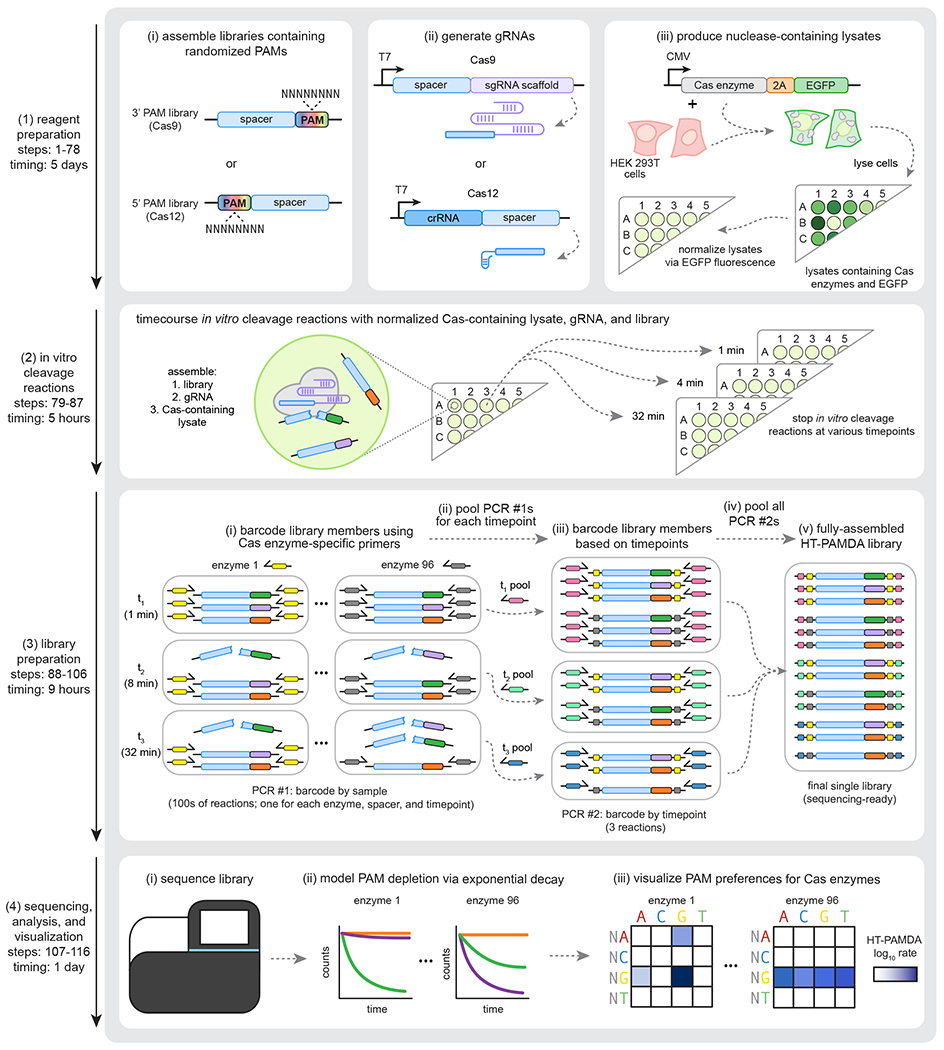

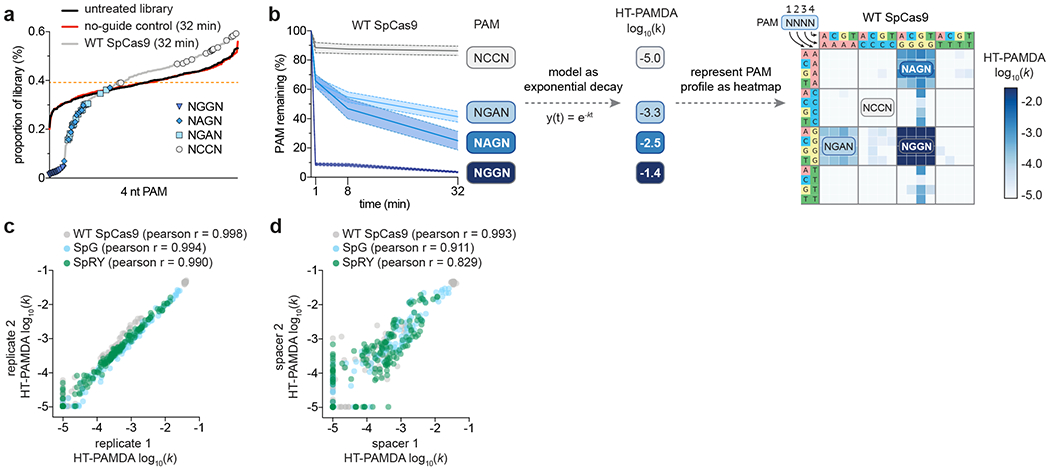

The HT-PAMDA method enables the characterization of Cas nuclease targeting range based on the in vitro cleavage of plasmid libraries harboring randomized PAMs (Fig. 2). The protocol requires the preparation of three components to perform the in vitro cleavage reactions: (1) substrate libraries encoding randomized PAMs, (2) gRNAs required to target the Cas protein(s) to cleave the libraries, and (3) cell lysates containing normalized Cas nucleases, avoiding laborious and low-throughput protein expression and purification. The in vitro cleavage reactions are performed by complexing the gRNAs with the normalized Cas lysates, and using this ribonucleoprotein (RNP)-containing lysate to cleave the randomized PAM library. Aliquots of each reaction are removed at several timepoints and the change in library composition over time is assessed by next-generation sequencing (NGS), similar to methods previously described in refs 6 and 7. Quantification of the cleavage kinetics for each PAM-harboring substrate permits the calculation of depletion rate constants for each PAM.

Fig. 2 |. Overview of HT-PAMDA workflow.

The HT-PAMDA protocol enables molecular characterization of the PAMs of different Cas enzymes. The workflow is divided into four major segments: (1) preparation of reagents, including the plasmid libraries harboring randomized PAMs, the gRNA(s), and the human cell lysates that contain Cas enzymes and EGFP (see protocol steps 1-78); (2) performing in vitro cleavage reactions using the reagents generated in section 1, stopping reactions at various timepoints (see protocol steps 79-87); (3) library preparation of the samples generated during the in vitro cleavage reactions of section 2 (the samples are barcoded, amplified, and pooled based on the Cas enzyme, spacer sequence, and timepoint; see protocol steps 88-106); and (4) sequencing of the libraries, data analysis, and visualization (see protocol steps 107-116).

Applications of the method

While our initial implementation of HT-PAMDA was to profile the PAM preferences of SpCas9 variants, this approach should be extensible to other Cas enzymes and for the in vitro characterization of other properties5. The enzyme-containing lysate and/or the PAM library (substrate library) can be substituted to develop new protocols to understand other parameters beyond targeting range. As examples, we will highlight two alternate implementations to characterize the PAM requirements of C-to-T base editors (CBEs) and A-to-G base editors (ABEs) in the CBE-HT-PAMDA and ABE-HT-PAMDA protocols, respectively. In these assays, the lysates containing normalized Cas nucleases are substituted for CBEs or ABEs to characterize the PAM requirements of these enzymes that nick and deaminate DNA compared to nucleases that generate double-strand breaks8,9. Pending appropriate modifications (discussed below), the HT-PAMDA method is applicable to study other Cas9 orthologs and Cas proteins of different classes (such as Cas12a proteins, as we demonstrated with the lower-throughput PAMDA approach)7. Alternatively, the protocol can also be modified to study different properties of Cas proteins. For example, the target specificities of Cas proteins can be studied using this method by substituting the randomized PAM substrate libraries for libraries encoding spacer sequences with mismatched bases. Broadly, HT-PAMDA and similar adaptations can form a suite of methods for the rapid characterization of the properties of genome editing tools.

Comparison with other methods

An array of computational and experimental approaches exists for the characterization of PAM preferences, each with their own advantages and disadvantages (Table 1). In silico PAM prediction tools use protospacer sequences found in endogenous CRISPR arrays to search for target sites in bacteriophage or plasmid sequences10–13. By analyzing the protospacer-adjacent sequences, a basic motif representing the PAM can be inferred. This method is generally reliable to predict the PAMs of Cas enzymes whose endogenous arrays encoded several protospacers but provides no indication of the performance of a Cas enzyme for genome editing. To avoid ambiguity of indirect interpretation of PAM preferences, direct experimental methods have been developed and can be broadly divided into in vitro, bacterial-cell based, and mammalian cell-based approaches. In most implementations, these methods utilize substrate libraries encoding fixed spacer sequences and randomized PAMs, where the PAM preference is inferred from changes in library composition following targeting by a Cas enzyme.

Table 1.

Comparison of methods to determine Cas enzyme PAM preference.

| Method | Ideal application | Advantages | Limitations | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In silico PAM prediction | Computational prediction of PAM preference for Cas effector enzymes in naturally occurring CRISPR systems | • Computational • Rapid and high throughput • Low cost |

• Not applicable to engineered enzymes • Enzyme performance is based on endogenous bacterial context (not in a mammalian genome editing setting) |

10–13 |

| Bacterial depletion assays, bacterial gene circuits, and in vitro transcription-translation systems | Characterization of PAM preference in a bacterial setting | • Rapid • Moderate-to-high throughput depending on scale of plating (nuclease-based) and FACS requirement (gene-circuits) |

• Limited control of reaction conditions in bacteria or bacterial lysate make it challenging to interpret how results will translate to a mammalian genome editing context • Separate molecular constructs required for bacterial and mammalian cell expression • Scalability can be limited for nuclease-based assays that require plating on large quantities of LB agar plates |

17–23 |

| Mammalian cell-based | Characterization of PAM preferences of a small number of Cas enzymes in a mammalian genome editing setting | • Profiling of activities in mammalian cells • Same construct and codon usage can be used for mammalian editing experiments • Provides edit outcome information |

• Low throughput due to large-scale tissue culture • Speed of assay is limited due to need for generation of clonal cell lines, and/or selection and expansion of transduced cells harboring gRNA/target library • Moderate control of reaction conditions. • Expression levels of Cas effectors may not be representative of transfection-based experiments |

24,25 |

| In vitro assay with purified protein | Characterization of PAM preferences of a small number of Cas enzymes in controlled in vitro reaction conditions | • Precise control of reaction conditions | • Low throughput due to the requirement for protein purification • Separate molecular constructs required for protein expression in bacteria and mammalian cell expression • Requires tuning of in vitro conditions to capture mammalian editing performance |

5–7,14–16 |

| HT-PAMDA | Characterization of PAM preferences of small to large numbers of Cas enzymes in controlled in vitro reaction conditions | • Precise control of reaction conditions • Rapid and scalable • Same molecular construct can be used for mammalian editing applications |

• Requires tuning of in vitro conditions to capture mammalian editing performance | 5 |

In vitro methods are generally performed using DNA substrate libraries harboring randomized PAMs, which are then subject to in vitro cleavage reactions with Cas enzymes5–7,14–16. These approaches typically use either purified Cas proteins for precise control of reaction conditions, or Cas protein produced by in vitro transcription-translation systems or cultured cells. In the latter cases, assay throughput is improved by avoiding protein purification, but precise control of reaction conditions is not possible without a means to accurately normalize nuclease input.

Bacterial-based approaches have been developed to profile libraries of randomized PAMs in living cells either by cleavage (PAM depletion assay) or using gene circuits based on DNA binding (for activation of fluorescent protein expression)17–23. These methods are scalable but offer limited control over reaction conditions. PAM characterization in cultured human cells is also possible by integrating the Cas nuclease and a library of target sites with randomized PAMs into the genomes of human cells24,25. Generating the required cell lines and the large-scale experimental and cell culture requirements can limit the throughput of these assays.

Beyond the fundamental differences between experimental PAM characterization methods, there are many important shared parameters that differ across implementations. In particular, the degree of control over experimental conditions critically influences assay reproducibility and calibration to reflect performance in the genome editing application of interest. Additionally, aspects of assay design such as endpoint versus kinetics measurements, the number of randomized bases in the PAM, the position of the PAM relative to the spacer (5’ or 3’), using NGS versus Sanger sequencing to analyze substrate depletion or enrichment, and other considerations all vary between methods. In the experimental design section, we expand on the importance of these parameters. Like other similar protocols, we imagine that several steps should be amenable to automation, which would improve the throughput of HT-PAMDA.

Advantages

HT-PAMDA is an in vitro approach that offers unique scalability and other capabilities for the characterizing Cas proteins. While HT-PAMDA is performed in vitro, in the case of our original publication of HT-PAMDA the Cas proteins are expressed in human cells, controlling for organism-specific nuances in PAM preferences by performing the method in an appropriate context5. Precise control of Cas nuclease input to the reaction is achieved by co-expressing a fluorescent protein for fluorescence-based normalization, enabling highly reproducible characterizations that are consistent with the performance of nucleases in genome editing experiments5. Further, the use of human cell lysate obviates the need for laborious and low-throughput protein purification. Combined with a library preparation protocol and analysis pipeline designed for sample multiplexing, HT-PAMDA enables accurate, rapid, and scalable characterization of the PAM requirements of Cas enzymes. Finally, since human expression constructs are used for PAM characterization, no additional cloning steps are necessary to conduct follow-up genome editing experiments in human cells. Overall, HT-PAMDA is a rapid and scalable assay that is most effective from a cost perspective when several variants are to be characterized (Table 2). The modularity of the assay also lends itself to being adaptable to profile other important properties of enzymes.

Table 2.

Sequencing costs per nuclease for HT-PAMDA with different sequencing platforms and reagents.

| Platform | Sequencing kit | Reagent price* | Estimated non-PhiX reads | Number of samples** | Sequencing cost per nuclease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiSeq | MiSeq Reagent Micro Kit v2 (300-cycles) | $479 | 3,000,000 | 3 | $141 |

| MiSeq | MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (150-cycle) | $989 | 15,000,000 | 17 | $58 |

| NextSeq | NextSeq 500/550 Mid Output Kit v2.5 (150 Cycles) | $1,179 | 81,000,000 | 92 | $13 |

| NextSeq | NextSeq 500/550 High Output Kit v2.5 (75 Cycles) | $1,617 | 250,000,000 | 283 | $6 |

List prices in USD from Illumina website as-of August 2020.

A sample is considered as one nuclease evaluated on two distinct substrate libraries with three reaction timepoints.

Limitations

Similar to other PAM characterization methods that are based on substrate depletion, HT-PAMDA might be most appropriate for studying Cas enzymes with more defined PAM requirements. One potential bottleneck in scalability of the assay is the requirement to obtain expression constructs for individual Cas enzymes, whether through molecular cloning or gene synthesis. However, this is a requirement for any method. Additionally, NGS remains a major cost of executing HT-PAMDA and other assays (see below and Table 2). Furthermore, we typically perform HT-PAMDA on two libraries that encode distinct spacer sequences to detect and potentially compensate for any spacer-specific features that influence PAM preference. While the inclusion of additional spacers might offer a more comprehensive analysis of this property, the durations of several steps of the protocol scale linearly with the number of substrates profiled and thus this must be considered when planning.

Experimental design

Overview of the workflow

HT-PAMDA consists of four major steps (Fig. 2): (i) reagent preparation (cloning the randomized PAM library, gRNA preparation, and production of nuclease-containing lysate), (ii) in vitro cleavage reactions, (iv) library preparation, and (iv) sequencing, analysis, and visualization.

Randomized PAM library (substrate library) cloning (Steps 1-28)

The randomized PAM libraries, or substrate libraries, are the substrates to be used in the in vitro cleavage reactions. These libraries have two critical features: (i) a fixed spacer sequence, and (ii) a region of randomized nucleotides in place of the PAM (Fig. 2). Appropriate design of both features is important for accurate PAM characterization.

The spacer. Libraries should be constructed with spacer sequences known to be efficiently targeted. Constructing multiple libraries with distinct spacer sequences enables potential spacer-specific effects on PAM preference to be accounted for and performing the assay on a second library also serves as a technical replicate, as the in vitro cleavage reactions are performed separately. Additional spacer design considerations apply when adapting HT-PAMDA for characterizing base editors (e.g. having targetable bases in the edit window of the target site) or other enzymes2.

The PAM. To accommodate the possibility that a Cas enzyme may recognize an extended PAMs and/or can exhibit preferences beyond their core motifs, the randomized sequence should be longer than is expected to be necessary. The orientation of the randomized PAM relative to the spacer sequence is another important feature of the substrate library. The position of the PAM depends on the category of Cas enzyme being studied; generally, Cas9 nucleases require PAMs on the 3’ end of the spacer, while Cas12 nucleases require 5’ PAMs Figs. 1b and 1c). Alternatively, libraries may be designed with spacer sequences flanking either side of the randomized PAM to generate a single substrate for Cas enzymes with either 3’ or 5’ PAM requirements.

gRNA preparation (Steps 56-65)

In HT-PAMDA, the gRNA is targeted to the spacer sequence adjacent to the randomized region of the library. There are two general approaches to preparing the gRNA: separate production of a purified gRNA (as done in the HT-PAMDA protocol) or co-transfection of the gRNA and nuclease expression plasmids into cells, combining the nuclease and gRNA production steps. The choice between these options should depend on the number of unique gRNAs to be used in the assay. If a small number of gRNAs will be used to characterize many Cas enzymes that share the same gRNA scaffold (as is the case when characterizing engineered variants of one Cas ortholog), it may be more economical to prepare the gRNA in bulk by in vitro transcription or to purchase a chemically synthesized gRNA for those that are commercially available. Alternatively, if each nuclease requires a different gRNA (for example, when characterizing multiple different Cas orthologs), it may be advantageous to co-transfect nuclease and gRNA expression plasmids into human cells when generating the lysates to avoid a large number of in vitro transcription reactions. If generating the gRNA from a lysate, the gRNA expression plasmid should be transfected in excess so that nuclease molecules are saturated with gRNA.

Production of nuclease-containing lysate (Steps 66-78)

The source of Cas enzyme for HT-PAMDA from unpurified and concentration-normalized human cell lysates facilitates the scalability and accuracy of the method. To generate Cas enzymes from human cell (e.g. HEK 293T) lysates, all nuclease coding sequences should be cloned into an appropriate human expression vector that also includes a transcriptionally coupled fusion to a reporter gene to enable lysate normalization (e.g. to a 2A peptide and a fluorescent protein; Fig. 2). While obtaining sufficient quantities of Cas enzyme and reporter protein for accurate fluorescence quantification and appropriate in vitro cleavage reaction conditions is generally robust when transfecting human codon optimized constructs into HEK 293T cells, this may require optimization under different experimental conditions (see Troubleshooting for more information). Although we have not performed HT-PAMDA using Cas proteins derived from other cell types, we anticipate that Cas proteins expressed from other cells should be equivalently effective in the protocol if the cells are sufficiently transfected with the Cas expression plasmid harboring the P2A-EGFP sequence.

In vitro cleavage reactions (Steps 79-87)

Time course in vitro cleavage experiments with control samples can be performed to test the functionality of both the lysate and gRNA before proceeding to a large-scale characterization. This ensures performance of reagents and is recommended to optimize conditions for new systems. In addition to the intended lysate/gRNA/PAM library combination, control samples should include (i) un-transfected lysate, (ii) nuclease-containing lysate without gRNA, and (iii) nuclease-containing lysate with non-targeting gRNA. We recommend using SpCas9 and AsCas12a as positive control nucleases for 3’ and 5’ PAM libraries, respectively. The results of these quality control experiments may be determined by NGS by following the HT-PAMDA protocol. Alternatively, for a faster quality control readout, DNA substrates resembling the PAM library but instead harboring fixed canonical and non-canonical PAMs may be used (to establish an appropriate dynamic range of in vitro cleavage rates of various substrates for the assay). Small-scale pilot experiments allow optimization of PAM library concentration, lysate concentration, and timepoint selection, where the in vitro cleavage reactions can be visualized and quantified by agarose gel or capillary electrophoresis.

It is desirable to have a control nuclease for which the performance of the nuclease in mammalian genome editing applications is known. Assay conditions should reflect the performance of the control nuclease in relevant genome editing settings. For example, with SpCas9 as a control in vitro cleavage reaction, canonical NGG PAMs should be depleted in early timepoints, and non-canonical NAG and NGA PAMs should be depleted at later timepoints to recapitulate the well-documented relative activities in human cells5,7,17,18,25.

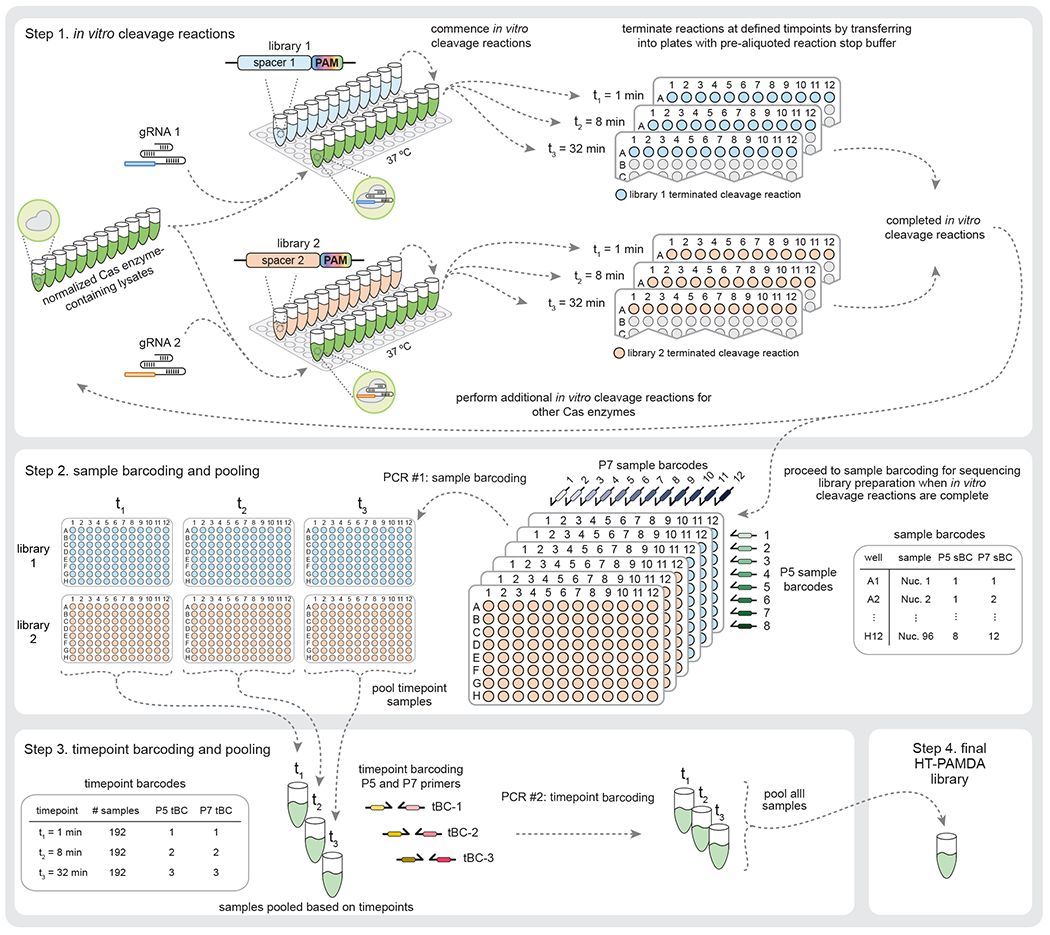

NGS library preparation and sequencing (Steps 29-48, 88-116)

The library preparation for HT-PAMDA is designed to maximize throughput by minimizing pipetting and leveraging multiple barcoding steps (Figs. 2 and 3). First, each reaction aliquot is labeled during PCR using primers encoding unique barcodes to index and distinguish variant nucleases. All uniquely barcoded nuclease samples from a given timepoint can then be pooled together; each timepoint pool is subsequently labeled using timepoint barcode primers (via Illumina indices) before final pooling of all samples (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 3 |. Detailed experimental workflow for in vitro cleavage reactions and library preparation.

Stage 1: The gRNA is complexed with the Cas enzymes within the normalized lysates at 37 °C, and in vitro timecourse cleavage reactions commence when the substrate library is added. Two substrate libraries (and corresponding gRNAs) harboring distinct spacer sequences are used as technical replicates and to account for sequence-specific effects within the spacers. Aliquots of in vitro cleavage reactions are removed at each timepoint and mixed with pre-aliquoted reaction stop buffer in separate plates to halt the reactions. This process is repeated for all samples (for simplicity, 12 samples per library are shown; the process scales easily to 96 samples per library in a complete plate). Stage 2: Samples are barcoded during PCR #1 with the sample barcoding primers (sBCs) in the first step of library preparation. A given sample receives the same P5 and P7 barcodes across timepoints and substrate libraries. Stage 3: All samples from a timepoint are pooled to create the timepoint pools, which are subsequently barcoded with timepoint barcodes (tBCs) during PCR #2 using standard Illumina P5 and P7 barcoding primers. Stage 4: The timepoint pools are combined to generate the final sequencing-ready HT-PAMDA library.

The required sequencing depth per sample is dependent on the PAM representation of the substrate library, the number of nucleotides required to ascertain the complete PAM, the number of timepoints, and the number of substrate libraries. These factors considered, we recommend sequencing at a depth of approximately 750,000 reads per sample to resolve up to 5 nt of PAM preference, where a sample is comprised of one nuclease across three timepoints on two randomized PAM libraries harboring distinct spacer sequences (an average of 125,000 reads per nuclease/substrate library/timepoint). Accounting for a PhiX spike-in to increase nucleotide diversity and typical mapping rates in the analysis pipeline, there are several sequencing platforms and reagent kits that enable flexible assay throughput (Table 2).

Visualization of PAM preference (Step 116)

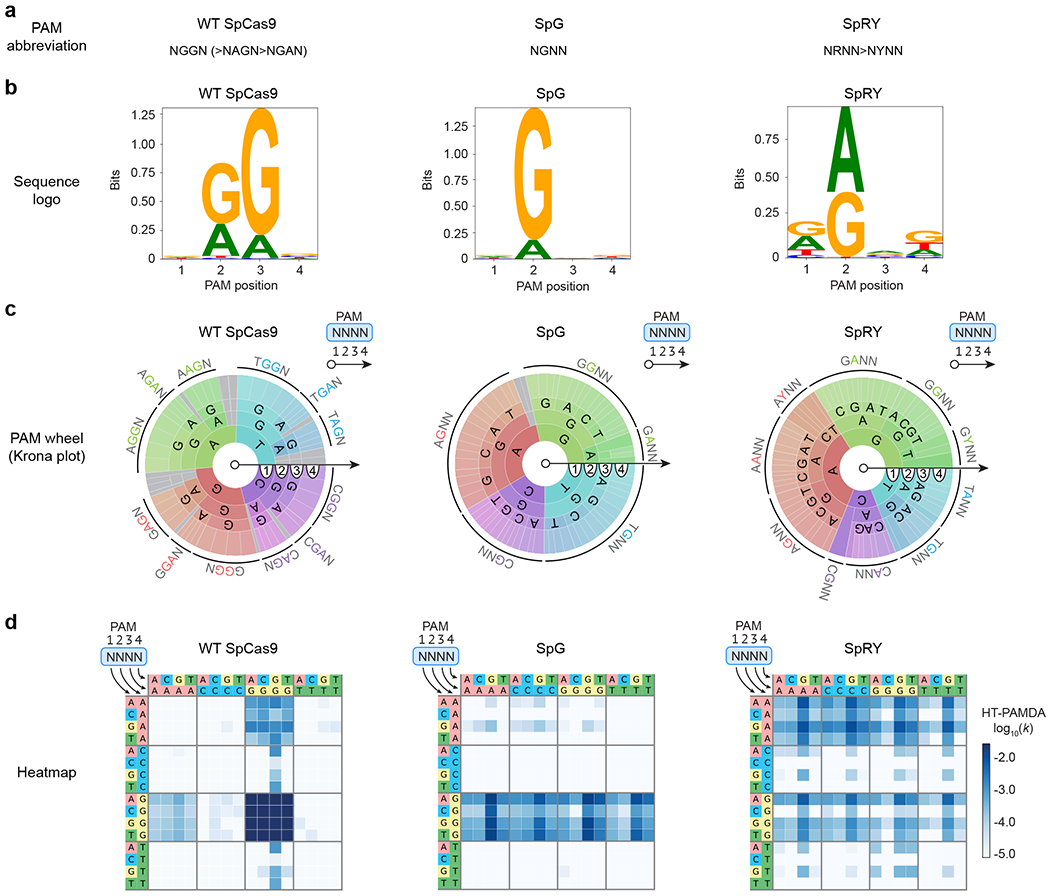

Representations of PAM preference ideally provide a comprehensive description of both PAM preference and activity (Figs 4a–d). Plain text abbreviations of PAM preference are convenient but minimally informative (Fig 4a). Additionally, sequence logos have become a popular method for depicting PAM preference due to their simplicity (Fig. 4b). However, these representations treat each position of the PAM independently and provide no information about the absolute level of activity targeting any PAM. For example, with a sequence logo of the PAM of wild-type (WT) SpCas9, it can be difficult to interpret the relative differences between NRR PAMs (where R is A or G), despite their established biological ranking of NGG>NAG>NGA>>>NAA (Fig. 4b)17,18. PAM wheels are a representation based on Krona plots that preserve position interdependencies (Fig. 4c)22,26. However, PAM wheels indicate only PAM preference, without a measure of absolute activity. For example, PAM wheels of wild-type SpCas9 and SpG reveal that both enzymes target NGG PAMs, but do not enable a comparison of their activities (Fig. 4c). Finally, heatmap representations of PAM preference capture both position interdependencies and activity on an absolute scale (Fig. 4d). For this reason, we prefer to represent PAM preferences as log scale heatmaps of PAM depletion rate constants. The rate constants reflect rate of depletion for any given PAM from a library over time, and are directly comparable across nucleases to determine differences in targeting efficiency.

Fig. 4 |. Representations of Cas enzyme PAM preference.

a-d, The PAM requirements of wild-type (WT) SpCas9, SpG, and SpRY5 are represented using four common methods that convey varying degrees of information (sequence preferences, positional dependencies, and absolute activities): plain text (panel a), sequence logos (generated using Logomaker30; panel b), PAM wheels (generated using modified Krona plots26; panel c), and heatmaps (panel d). All representations of PAM preference were generated using the same HT-PAMDA characterizations, with two replicates on each of two spacer sequences for a total of four replicates per nuclease (see Supplementary Note 2 for details). Source data for this figure was published with the original description of SpG and SpRY5.

Beyond the choice of PAM visualization format, it’s also essential to represent all bases of the PAM that influence PAM preference. Failing to do so can misleadingly represent a group of PAMs as targetable, when the group is actually comprised of both targetable and non-targetable sequences. Even thoroughly characterized nucleases have PAM preferences beyond their well-known canonical requirements so it is good practice to visualize more positions than are anticipated to influence activity. For example, while SpCas9 is known to have 2 nt of specificity for its canonical NGG PAM, the capacity to target sites with shifted NNGG PAMs is apparent when also visualizing the 4th nucleotide of the PAM (Fig. 4d)5,18,27.

Additional design considerations

Endpoint versus kinetics measurements

Most experimental methods for characterizing PAM specificity are amenable to either endpoint or multiple timepoint measurements that enable calculation of kinetic parameters. While endpoint measurements are experimentally more straightforward and require less total sequencing depth, they can provide dramatically different characterizations of PAM preference depending on the selected timepoint. The use of multiple timepoints enables the determination of cleavage kinetics for each PAM, a more intrinsic metric of activity that is more informative compared to the use of a single endpoint measurement.

Alterations for base editor formats (Step 87)

While PAM depletion assays typically require DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) to deplete targetable PAMs from the library, these assays are also adaptable for the measurement of other DNA modifications such as those made by base editors. For example, in CBE-HT-PAMDA the CBE generates target strand nicks and non-target strand C-to-U deamination events that can be converted to DSBs via treatment with USER enzyme to excise uracil nucleotides5. Similarly, in ABE-HT-PAMDA, ABEs generate target strand nicks and non-target strand A-to-I deamination events that can be converted to DSBs via treatment with Endonuclease V to cleave the inosine-containing non-target strand28. These assays require additional considerations, including library design to position target cytosines or adenines within the edit window of the target site, and alterations to in vitro reaction conditions to accommodate different reaction kinetics.

Assay readout formats by sequencing

Most PAM determination assays can be read out by either NGS or Sanger sequencing. Sanger sequencing of PAM libraries provides a coarse description of PAM preference by averaging composition at each position of the PAM at a given endpoint. This can be rapid and affordable for a small number of samples; however, this approach occludes positional dependencies in the PAM and thus can provide an inaccurate characterization of PAM preference. NGS-based readouts provide a more complete characterization and enable sample multiplexing via barcoding that increase sample throughput while decreasing per-sample cost.

Materials

Biological materials

-

HEK 293T cells (ATCC, cat. no. CRL-3216; https://scicrunch.org/resolver/RRID:CVCL_0063)

CAUTION: The cell lines used in your research should be regularly checked to ensure they are authentic and are not infected with mycoplasma.

XL1-Blue chemically competent E. coli (Agilent, cat. no. 200229)

XL1-Blue electrocompetent E. coli (Agilent, cat. no. 200158)

Reagents

General laboratory reagents

Deoxynucleotide (dNTP) solution mix (New England BioLabs, cat. no. N0447L)

Super optimal broth (SOB) (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. H8032-500G)

D-(+)-Glucose (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. G8270-100G)

Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. L3022-250G)

LB agar (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. L2897-250G)

Carbenicillin disodium salt (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. C1389-1G)

Sera-Mag carboxylate-modified magnetic particles (hydrophobic) (Cytiva, cat. no. 44152105050250)

Polyethylene Glycol 8000 (PEG) (Fisher BioReagents, cat. no. BP233-100)

Sodium chloride solution (5 M) (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. 7647-14-5)

UltraPure 1M Tris-HCI, pH 8.0 (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 15568025)

Tween20 (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. P1379-100ML)

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution, pH 8.0, ~0.5 M in H2O (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. 03690-100ML)

CAUTION: Causes serious eye irritation. Wear eye protection.

-

Ethanol solution 70% (Fisher BioReagents, cat. no. BP8201500)

CAUTION: Ethanol is flammable. Keep away from heat and open flames.

-

Ethidium bromide solution (MilliporeSigma, cat. No. E1510-10ML)

CAUTION: Toxic if inhaled. Suspected of causing genetic defects. Wear protective equipment.

QX DNA Fast Analysis Kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 929008)

Purple (6X) Gel Loading Dye (New England BioLabs, cat. no. B7024S)

QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 28704)

MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 28004)

Plasmids, plasmid libraries, and oligonucleotides

Plasmids required for cloning or ready-to-use plasmids and plasmid libraries (listed in Table 3, available from Addgene)

Custom oligonucleotides for cloning and library preparation (listed in Table 4). All oligonucleotides were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies at the 25 nmol scale as standard desalted oligonucleotides. Higher synthesis scales might improve oligonucleotide purity. For the randomized bases of the PAM libraries, the hand-mixed base option was used.

Table 3.

Plasmids.

| Plasmid | Description | Purpose | Step(s) | Addgene ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p11-LacY-wtx1 | Randomized substrate library entry vector. | For cloning randomized PAM substrate libraries. Other plasmid backbones are acceptable substitutes. | 1 | 69056 |

| RTW554 | p11-Cas9_random_PAM-site1 | Randomized 3’ PAM substrate library – site 1 | 25 | 160132 |

| RTW555 | p11-Cas9_random_PAM-site2 | Randomized 3’ PAM substrate library – site 2 | 25 | 160133 |

| RTW572 | p11-Cas12_random_PAM-site3 | Randomized 5’ PAM substrate library – site 3 | 25 | 160134 |

| RTW574 | p11-Cas12_random_PAM-site4 | Randomized 5’ PAM substrate library – site 4 | 25 | 160135 |

| MSP3485 | pT7-BsaI_cassette-SpCas9_sgRNA | Entry vector for T7 promoter in vitro transcription of SpCas9 sgRNAs | 56* | 140082 |

| BPK1520 | pUC19-U6-BsmBI_cassette-SpCas9_sgRNA | Entry vector for U6 promoter expression of SpCas9 sgRNAs | 56* | 65777 |

| MSP3491 | pT7-AsCas12a_crRNA-BsaI_cassette | Entry vector for T7 promoter in vitro transcription of AsCas12a crRNAs. | 67* | 114067 |

| BPK3079 | pUC19-U6-AsCas12a_crRNA-BsmBI_cassette | Entry vector for U6 promoter expression of AsCas12a crRNAs | 67* | 78741 |

| RTW443 | pT7-SpCas9_sgRNA-site1 | in vitro transcription template for SpCas9 sgRNA targeting 3’ PAM substrate library - site 3 (RTW554) | 56 | 160136 |

| RTW448 | pT7-SpCas9_sgRNA-site2 | in vitro transcription template for SpCas9 sgRNA targeting 3’ PAM substrate library - site 4 (RTW555) | 56 | 160137 |

| RTW549 | pT7-AsCas12a_crRNA-site3 | in vitro transcription template for AsCas12a cRNA targeting 5’ PAM substrate library - site 3 (RTW572) | 56 | 160138 |

| MSP3511 | pT7-AsCas12a_crRNA-site4 | in vitro transcription template for AsCas12a cRNA targeting 5’ PAM substrate library - site 4 (RTW574 | 56 | 160139 |

| RTW3027 | pCMV-T7-SpCas9-P2A-EGFP | Human expression plasmid for wild-type SpCas9-P2A-EGFP that can serve as a positive control for 3’ PAM libraries. Can also be used to clone other Cas nuclease coding sequences into the NotI and BamHI sites. | 67 | 139987 |

| RTW2861 | pCMV-T7-AsCas12a-P2A-EGFP | Human expression plasmid for wild-type AsCas12a-P2A-EGFP that can serve as a positive control for 5’ PAM libraries. | 67 | 160140 |

Can be used to clone SpCas9 or AsCas12a gRNAs with custom spacer sequences for T7 in vitro transcription of gRNAs (T7 promoter, Step 56) or for co-transfection into cells (U6 promoter, Step 67).

Table 4.

Oligonucleotides.

| oligonucleotide ID | oligonucleotide description | oligonucleotide sequence* |

|---|---|---|

| oBK984 | reverse primer to fill in the bottom strand of top strand library oligos | /5Phos/CCTCGTGACCTGCGC |

| oBK1948 | top strand library oligo for 3’ PAM library - spacer 1 with 8xN 3’ PAM | GCAGgaattcGGGAGGGGCACGGGCAGCTTGCCGGNNNNNNNNCTNNNGCGCAGGTCACGAGGCATG |

| oBK1949 | top strand library oligo for 3’ PAM library - spacer 2 with 8xN 3’ PAM | GCAGgaattcGGAGGGTCGCCCTCGAACTTCACCTNNNNNNNNCTNNNGCGCAGGTCACGAGGCATG |

| custom_3prime | top strand library oligo for 3’ PAM library - custom spacer (20x ‘X’) with 8xN 3’ PAM. Here, the intended target site sequence is indicated by the “X” bases. | GCAGgaattcGGAGGXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXNNNNNNNNCTNNNGCGCAGGTCACGAGGCATG |

| oBK5962 | top strand library oligo for 5’ PAM library - spacer 3 with 10xN 5’ PAM | AGACCGGAATTCNNNGTNNNNNNNNNNGGAATCCCTTCTGCAGCACCTGGGCGCAGGTCACGAGGCATG |

| oBK5964 | top strand library oligo for 5’ PAM library - spacer 4 with 10xN 5’ PAM | AGACCGGAATTCNNNGTNNNNNNNNNNCTGATGGTCCATGTCTGTTACTCGCGCAGGTCACGAGGCATG |

| custom_5prime | top strand library oligo for 5’ PAM library - custom spacer (20x ‘X’) with 10xN 5’ PAM. Here, the intended target site sequence is indicated by the “X” bases. | AGACCGGAATTCNNNGTNNNNNNNNNNXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXGCGCAGGTCACGAGGCATG |

| oRW53 | top strand oligo to clone SpCas9 IVT sgRNA with spacer 1 into MSP3485 | atagGGCACGGGCAGCTTGCCGG |

| oRW55 | bottom strand oligo to clone SpCas9 IVT sgRNA with spacer 1 into MSP3485 | aaacCCGGCAAGCTGCCCGTGCC |

| oRW54 | top strand oligo to clone SpCas9 IVT sgRNA with spacer 2 into MSP3485 | atagTCGCCCTCGAACTTCACCT |

| oRW56 | bottom strand oligo to clone SpCas9 IVT sgRNA with spacer 2 into MSP3485 | aaacAGGTGAAGTTCGAGGGCGA |

| custom_Sp_top | top strand oligo to clone SpCas9 IVT sgRNA with a custom spacer into MSP3485. Here, the intended spacer sequence is indicated by the “X” bases. | atagXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX |

| custom_Sp_bot | bottom strand oligo to clone SpCas9 IVT sgRNA with a custom spacer into MSP3485. Here, the reverse complement of the intended spacer sequence is indicated by the “X” bases. | aaacXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX |

| oRW188 | top strand oligo to clone AsCas12a IVT crRNA with spacer 3 into MSP3491 | agatCTGATGGTCCATGTCTGTTACTC |

| oRW189 | bottom strand oligo to clone AsCas12a IVT crRNA with spacer 3 into MSP3491 | taaaGAGTAACAGACATGGACCATCAG |

| oRW121 | top strand oligo to clone AsCas12a IVT crRNA with spacer 4 into MSP3491 | agatGGAATCCCTTCTGCAGCACCTGG |

| oRW124 | bottom strand oligo to clone AsCas12a IVT crRNA with spacer 3 into MSP3491 | taaaCCAGGTGCTGCAGAAGGGATTCC |

| custom_As_top | top strand oligo to clone AsCas12a IVT crRNA with a custom spacer into MSP3491. Here, the intended spacer sequence is indicated by the “X” bases. | agatXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX |

| custom_As_bot | bottom strand oligo to clone AsCas12a IVT crRNA with a custom spacer into MSP3491. Here, the reverse complement of the intended spacer sequence is encoded by the “X” bases. | taaaXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX |

| oRW1491 | P5 sample barcode primer 1 with CCTG barcode | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTCCCCTGGCATGCCTCGTGACCTGC |

| oRW1492 | P5 sample barcode primer 2 with CGTT barcode | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTCCCGTTGCATGCCTCGTGACCTGC |

| oRW1493 | P5 sample barcode primer 3 with ATTC barcode | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTCCATTCGCATGCCTCGTGACCTGC |

| oRW1494 | P5 sample barcode primer 4 with CTAC barcode | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTCCCTACGCATGCCTCGTGACCTGC |

| oRW1495 | P5 sample barcode primer 5 with TCTC barcode | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTCCTCTCGCATGCCTCGTGACCTGC |

| oRW1496 | P5 sample barcode primer 6 with CCAT barcode | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTCCCCATGCATGCCTCGTGACCTGC |

| oRW1497 | P5 sample barcode primer 7 with GCAA barcode | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGCAAGCATGCCTCGTGACCTGC |

| oRW1498 | P5 sample barcode primer 8 with ATGC barcode | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTCCATGCGCATGCCTCGTGACCTGC |

| oRW1499 | extra P5 sample barcode primer 9 with GATG barcode | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTCCGATGGCATGCCTCGTGACCTGC |

| oRW1500 | extra P5 sample barcode primer 10 with CGAT barcode | ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTCCCGATGCATGCCTCGTGACCTGC |

| oRW1501 | P7 sample barcode primer 1 with GTCA barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGGTCACGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1502 | P7 sample barcode primer 2 with CATG barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGCATGCGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1503 | P7 sample barcode primer 3 with AGTA barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGAGTACGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1504 | P7 sample barcode primer 4 with TCGC barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGTCGCCGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1505 | P7 sample barcode primer 5 with ACTT barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGACTTCGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1506 | P7 sample barcode primer 6 with ACGG barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGACGGCGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1507 | P7 sample barcode primer 7 with TCCA barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGTCCACGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1508 | P7 sample barcode primer 8 with CGAA barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGCGAACGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1509 | P7 sample barcode primer 9 with ATGT barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGATGTCGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1510 | P7 sample barcode primer 10 with TAGA barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGTAGACGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1511 | P7 sample barcode primer 11 with TTTG barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGTTTGCGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| oRW1512 | P7 sample barcode primer 12 with CGGT barcode | CTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTTGCGGTCGGTATTTCACACCGCATACGTAC |

| OJA1933 | P5 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 501 with TATAGCCT barcode (AGGCTATA for NextSeq) (P5-1) | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTATAGCCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1934 | P5 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 502 with ATAGAGGC barcode (GCCTCTAT for NextSeq) (P5-2) | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACATAGAGGCACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1935 | P5 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 503 with CCTATCCT barcode (AGGATAGG for NextSeq) (P5-3) | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACCCTATCCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1936 | P5 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 504 with GGCTCTGA barcode (TCAGAGCC for NextSeq) (P5-4) | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACGGCTCTGAACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1937 | P5 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 505 with AGGCGAAG barcode (CTTCGCCT for NextSeq) (P5-5) | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACAGGCGAAGACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1938 | P5 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 506 with TAATCTTA barcode (TAAGATTA for NextSeq) (P5-6) | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTAATCTTAACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1939 | P5 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 507 with CAGGACGT barcode (ACGTCCTG for NextSeq) (P5-7) | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACCAGGACGTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1940 | P5 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 508 with GTACTGAC barcode (GTCAGTAC for NextSeq) (P5-8) | AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACGTACTGACACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1941 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 701 with ATTACTCG barcode (P7-1) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCGAGTAATGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1942 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 702 with TCCGGAGA barcode (P7-2) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTCTCCGGAGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1943 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 703 with CGCTCATT barcode (P7-3) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATAATGAGCGGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1944 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 704 with GAGATTCC barcode (P7-4) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATGGAATCTCGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1945 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 705 with ATTCAGAA barcode (P7-5) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTTCTGAATGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1946 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 706 with GAATTCGT barcode (P7-6) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATACGAATTCGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1947 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 707 with CTGAAGCT barcode (P7-7) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATAGCTTCAGGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1948 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 708 with TAATGCGC barcode (P7-8) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATGCGCATTAGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1949 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 709 with CGGCTATG barcode (P7-9) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCATAGCCGGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1950 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 710 with TCCGCGAA barcode (P7-10) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATTTCGCGGAGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1951 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 711 with TCTCGCGC barcode (P7-11) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATGCGCGAGAGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

| OJA1952 | P7 timepoint barcode primer Illumina 712 with AGCGATAG barcode (P7-12) | CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCTATCGCTGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCT |

Features of oligonucleotides are indicated as follows. ‘N’: any base (randomized nucleotide). ‘X’: nucleotide of the researcher’s choice (for design of custom spacer sequences). Lowercase bases: restriction enzyme site or restriction enzyme overhangs. Underlined bases: sequence of interest (either a spacer sequence or a primer barcode).

Substrate library construction

Klenow Fragment (3’→5’ exo-) (New England BioLabs, cat. no. M0212S)

EcoRI-HF (New England BioLabs, cat. no. R3101S)

SphI-HF (New England BioLabs, cat. no. R3182S)

SpeI-HF (New England BioLabs, cat. no. R3133S)

PvuI-HF (New England BioLabs, cat. no. R3150S)

T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs, cat. no. M0202S)

QIAGEN Plasmid Plus Maxi Kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 12963)

gRNA preparation

RNase ZAP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. no. AM9780)

QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, cat. no. 27104)

BsaI-HFv2 (New England BioLabs, cat. no. R3733S)

HindIII-HF (New England BioLabs, cat. no. R3104S)

T7 RiboMAX express large scale RNA production kit (Promega, cat. no. P1320)

Tissue culture

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), high glucose, GlutaMAX, pyruvate (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 10569069)

PBS, pH 7.4 (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 10010031)

Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), qualified, heat inactivated (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 10438026)

Penicillin-Streptomycin (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 15070063)

Trypsin-EDTA (0.05%), phenol red (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 25300054)

Lysate preparation

TransIT-X2 transfection reagent (Mirus, cat. no. MIR 6000)

Opti-MEM reduced serum medium (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 31985062)

SIGMAFAST protease inhibitor cocktail, EDTA-free (Millipore Sigma, cat. no. S8830)

HEPES buffer solution, pH 7.5 (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. NC0358126)

Sodium chloride solution (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. S6546-1L)

Potassium chloride solution (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. 60142-500ML-F)

Magnesium chloride solution (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. M1028-100ML)

Glycerol (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. G5516-500ML)

-

Dithiothreitol (DTT) solution (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. 646563-10X.5ML)

CAUTION: DTT is toxic and may cause skin, eye, or respiratory irritation. Wear protective equipment.

Triton X-100 (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. T9284-100ML)

-

Fluorescein dye (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. F2456-2.5G)

CAUTION: Causes serious eye irritation. Wear eye protection.

In vitro cleavage reactions

Proteinase K (New England BioLabs, cat. no. P8107S)

Library preparation and sequencing

QuantiFluor dsDNA system (Promega, cat. no. E2670)

Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England BioLabs, cat. no. M0491L)

Betaine solution, 5 M (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. B0300-5VL)

Exonuclease I (New England BioLabs, cat. no. M0293S)

Universal KAPA Illumina Library qPCR Quantification Kit (KAPA Biosystems, cat. no. 7960140001)

-

Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution, 2 N (Honeywell Fluka, cat. no. 352541L)

CAUTION: Causes severe skin burns and eye damage. Wear protective equipment.

PhiX control v3 (Illumina, cat. no. FC-110-3001)

75-cycle NextSeq 500/550 High Output v2.5 kit (Illumina, cat. no. 20024906)

Equipment

Filtered sterile pipette tips

1.7 mL tubes (VWR, cat. no. 87003-294)

Axygen 96-well flat top polypropylene PCR microplate (Corning, cat. no. PCR-96-FLT-C)

Aluminum adhesive plate seal (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. Z721549-100EA)

384-well black/clear polystyrene microplates (Corning, cat. no. 3540)

8-strip tubes with cap (USA Scientific, cat. no. 1402-4708)

Axygen 25mL disposable reagent reservoir, sterile (Corning, cat. no. RES-V-25-S)

Axygen 24-well clear V-bottom 10 mL polypropylene rectangular well deep well plate (Corning, cat. no. P-DW-10ML-24-C)

Petri dishes (VWR, cat. no. 470210-568)

Vacuum filter flask (1 L) (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. S2HVU11RE)

Magnetic stir bar (VWR, cat. no. 76006-402)

Breathe Easier sealing membrane for multiwell plates (MilliporeSigma, cat. no. Z763624-100EA)

Electroporation cuvettes (BTX, cat. no. 45-0124)

Tissue culture dish (150 mm) (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 877224)

Serological pipettes (5 mL) (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 13-678-11D)

Serological pipettes (10 mL) (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 13-678-11E)

Serological pipettes (25 mL) (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 13-678-11)

24-well tissue culture plates (Corning, cat. no. 3526)

INCYTO C-Chip hemocytometers (SKC Inc., cat. no. DHC-N015)

MicroAmp optical 96-well reaction plate (Applied Biosystems, cat. no. N8010560)

MicroAmp optical adhesive film (Applied Biosystems, cat. no. 4360954)

Cell culture CO2 incubator

Magnetic stir plate

Gene Pulser Xcell Microbial System (BioRad, cat. no. 1652662)

Vortexer

Labnet mini plate spinner (Thomas Scientific, cat. no. 1225Z37)

Microcentrifuge (Eppendorf, cat. no. 5420000040)

QIAxcel Advanced Instrument (Qiagen, cat. no. 9001941)

Agarose gel electrophoresis apparatus (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. 09-528-110B)

Gel electrophoresis power source (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. FBEC300XL)

UV transilluminator (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. UV95045201)

Centrifuge (Eppendorf, cat. no. 5804)

Nanodrop spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher, cat. no. ND-2000)

Autoclave

Biological safety cabinet

Light microscope

Standard single-channel pipette set

Heated shaker-incubator for bacterial culture growth

Erlenmeyer flasks, 500 mL (Fisher Scientific, cat. no. S63273)

Serological pipettor

Multichannel pipette: 12-channel 2-20 μL

Multichannel pipette: 12-channel 20-200 μL

DynaMag-96 Side Magnet (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 12331D)

50 ml magnetic separation rack (New England BioLabs, cat. no. S1507S)

Fluorescence microplate reader (BioTek, DTX 880 Multimode Plate Reader)

96-well thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, cat. no. A24811)

qPCR machine (Applied Biosystems, Quant Studio 3)

Illumina sequencing platform (MiSeq, NextSeq, or other)

Software

bcl2fastq2 (Illumina)

Python 3 (https://www.python.org/downloads/)

HT-PAMDA (https://github.com/kleinstiverlab/HT-PAMDA)

Reagent setup

Solutions

-

Glucose solution (1 M)

Dissolve 18 g of glucose in 100 mL of water. Filter or autoclave to sterilize and store aliquots at room temperature (22 °C) or −20 °C indefinitely.

-

Carbenicillin stock (1000X, 100 mg/mL)

Dissolve 1 g of carbenicillin disodium salt in 10 mL of water. Mix to dissolve, aliquot, and store at −20 °C for at least one year.

-

Sodium chloride-tris-EDTA (STE) buffer (10X)

To make 10X STE buffer, combine 1 mL of 1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mL of 5 M NaCl, 200 μL of 0.5 M EDTA pH 8.0, and nuclease-free water to 10 mL (1X STE: 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA). Filter or autoclave to sterilize and store aliquots at room temperature indefinitely.

-

1X TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA)

Combine 5 mL 1M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mL 0.5M EDTA (pH 8.0), and nuclease-free water to 500 mL. To prepare 0.1X TE, diluted 1:10 using nuclease-free water. Filter or autoclave to sterilize and store aliquots at room temperature indefinitely.

-

SPRI buffer

Combine 135 g of PEG-8000, 150 mL of 5 M NaCl, 7.5 mL of 1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1.5 mL of 0.5 M EDTA, 375 μL of Tween20, and sterile-filtered deionized water to a final volume of 750 mL. Add a magnetic stir bar and stir on a magnetic stir plate. The solution may be heated to approximately 50 °C to facilitate dissolving the PEG. When dissolved, the solution should be completely transparent. Sterile filter the buffer and store at room temperature indefinitely. The buffer is highly viscous and will pass slowly through the filter.

CRITICAL: carefully handle the buffer after filtering to avoid contamination.

-

Cleavage buffer (10X)

To make 10X cleavage buffer, combine 10 mL of 1 M Hepes pH 7.5, 30 mL of 5 M NaCl, 5 mL of 1 M MgCl2, and deionized water to a final volume of 100 mL (1X cleavage buffer: 10 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2). Filter or autoclave to sterilize and store aliquots at room temperature indefinitely.

Prior to use in in vitro cleavage reactions, a 1 mL aliquot of 10X cleavage buffer should be supplemented with 10 μL of 1 M DTT (to make 10X cleavage buffer + DTT).

CRITICAL: DTT is a reducing agent and is not stable in solution, therefore the cleavage buffer + DTT solution should be prepared fresh.

-

Lysis buffer (1X)

To make 1X lysis buffer, combine 2 mL of 1 M Hepes pH 7.5, 10 mL of 1 M KCl, 500 μL of 1 M MgCl2, 5 mL of glycerol, SIGMAFAST Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (EDTA-Free), 100 μL of 1 M DTT, 100 μL of Triton X-100, and sterile-filtered deionized water to a final volume of 100 mL. Mix until the protease inhibitor tablet is dissolved. (1X lysis buffer: 20 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor). The lysis buffer without DTT and the protease inhibitor can be filtered or autoclave to sterilize and aliquots can be stored at room temperature indefinitely. Fully reconstituted lysis buffer should be prepared fresh.

CRITICAL: DTT is a reducing agent and is not stable in solution. The protease inhibitor is stable in solution for 2 weeks at 4 °C.

-

Reaction stop buffer (1X)

For stopping in vitro cleavage reactions, prepare a solution of 1X stop buffer by combining 0.5 μL Proteinase K (20mg/ml), 0.5 μL 500 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and 4 μL water for each reaction to be stopped (for final concentrations of 2 mg/mL Proteinase K and 50 mM EDTA).

CRITICAL: Reaction stop buffer should be prepared fresh to maintain optimal Proteinase K activity.

-

Fluorescein dye stock solution

Prepare a stock solution of 2.5 mM fluorescein dye. First, dissolve 1 mg of fluorescein free acid in 1 mL of 1 M NaOH. Next, dilute the 1 mg/mL dye solution to 2.5 mM in 1X cleavage buffer. Store 1 mL aliquots at −20 °C for at least one year.

CAUTION: Fluorescein causes serious eye irritation; wear eye protection.

-

NaOH (0.2 N)

Dilute 10 μL of 2 N NaOH in 90 μL of nuclease-free water.

CRITICAL: Prepare fresh immediately before use.

CAUTION: NaOH causes skin burns and serious eye damage; wear protective equipment.

-

Tris-HCl and Tween 20 solution (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% Tween 20)

Combine 100 μL of 1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 10 μL of Tween 20, and nuclease-free water to 10 mL. Filter or autoclave to sterilize and store aliquots at room temperature indefinitely.

-

Tris-HCl (200 mM)

Combine 200 μL of 1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 800 μL of nuclease-free water. Filter or autoclave to sterilize and store aliquots at room temperature indefinitely.

Media

-

HEK 293T culture medium

In a biological safety cabinet, combine Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS; final 10% v/v), and Penicillin-Streptomycin (100 U/mL). Sterile filter media with a vacuum flask. Media should be stored at 4 °C and warmed to 37 °C before use. Fresh media should be prepared every few months.

-

SOC (1 L)

Reconstitute 28 g of super optimal broth (SOB) powder with distilled water to 1 L. Dissolve powder by swirling. Autoclave at 121 °C for 30 minutes to sterilize. Let the medium cool to room temperature; once cooled, add 20 mL of sterile-filtered 1 M glucose. Prepared SOC can be stored at room temperature indefinitely if kept sterile.

-

LB broth (1 L)

Reconstitute 25 g of lysogeny broth (LB) powder with deionized water to 1 L. Dissolve powder by swirling. Autoclave at 121 °C for 30 minutes to sterilize. Let the medium cool to room temperature before adding antibiotic. For LB with Carbenicillin: Add 1 mL of Carbenicillin at 100 mg/mL to 1 L of LB broth. LB with Carbenicillin can be stored at 4 °C for 2 weeks. For LB with Kanamycin: Add 1 mL of Kanamycin at 50 mg/mL to 1 L of LB broth. LB with Kanamycin can be stored at 4 °C for 2 weeks.

-

LB agar (1 L)

Reconstitute 40 g of LB agar powder with deionized water to 1 L. Dissolve powder by swirling. Add a magnetic stir bar. Autoclave at 121 °C for 30 minutes to sterilize. After autoclaving but while the solution is still hot, stir slowly at room temperature using the magnetic stir bar and a magnetic stir plate. Let the medium cool to approximately 50 °C while stirring before adding antibiotic. For LB with carbenicillin: Add 1 mL of Carbenicillin at 100 mg/mL to 1 L of LB agar and stir for several minutes. For LB with kanamycin: Add 1 mL of Kanamycin at 50 mg/mL to 1 L of LB agar and stir for several minutes. Before the media cools and solidifies, pour approximately 20 mL of LB agar with antibiotic into 100-mm Petri dishes. Cover Petri dishes once poured and store at room temperature until the plates have cooled to room temperature. Store LB agar plates in plastic bags at 4 °C for up to a month.

SPRI bead preparation

-

Prepare SPRI beads as previously described29. Briefly, prepare Sera-Mag SpeedBeads in a 50 mL conical tube using an appropriate magnetic rack. Wash the beads with 0.1X TE buffer (for a total of 5 washes using 40 mL 0.1X TE each) and then resuspend in 750 mL of SPRI buffer. Mix the solution well, aliquot, and store at 4 °C for up to 6 months (longer storage can alter the DNA fragment retention of the beads). The DNA fragment retention of the SPRI bead stock may be tested by performing a cleanup of a DNA ladder at a range of SPRI beads:DNA ladder volume ratios (recommended range of 0.5:1 to 2:1).

CRITICAL: All steps should be performed carefully to avoid contaminating the prepared bead stock.

Preparation of barcoded PCR primer plate for library preparation

There are two sets of primer pairs each used for two separate rounds of PCR: The first set of primers consists of the sample barcoding primers, which bind on the randomized PAM library and add both sample barcodes and Illumina read 1 (P5 end) and read 2 (P7 end) sequencing primer binding sites. The second set of primers consists of the timepoint barcoding primers, which bind to the Illumina read 1 and 2 sequencing primer binding sites (from primer set 1) and append both Illumina indices (which serve as the timepoint barcodes) and P5/P7 grafting regions. Oligos for both sets should be prepared in an arrayed plate layout. For each set of oligos, there are 8x P5 (P5-1 through P5-8) and 12x P7 (P7-1 through P7-12) primers. Lyophilized oligos can be resuspended using 0.1X TE (or other appropriate buffer) to a concentration of 100 μM.

For each set, prepare an arrayed 96-plate of 5 μM each forward and reverse primers as follows: Add 90 μL of 0.1X TE buffer to each well of a 96-well PCR plate. In a separate 8-strip tube, aliquot 70 μL of each 100 μM P5 primer in order P5-1 through P5-8. Using a multichannel, aliquot 5 μL of the primers into each column of the 96-well PCR plate such that row A contains P5-1, row B contains P5-2, etc. In a separate 12-strip tube, aliquot 50 μL of each 100 μM P7 primer in order P7-1 through P7-12. Using a channel multichannel, aliquot 5 μL of the primers into each row of the 96-well PCR plate such that column 1 contains P7-1, column 2 contains P7-2, etc. Seal tightly with an aluminum adhesive plate seal, mix by gently vortexing, spin down, and store at −20 °C. CRITICAL: When aliquoting primers, change tips between rows to avoid cross-contamination.

Procedure

CRITICAL: While the sample throughput of HT-PAMDA is flexible, as an example we will describe experimental steps for the characterization of 96 SpCas9 nucleases on two randomized PAM libraries with distinct spacer sequences. All steps should be performed with care to avoid cross-contamination.

PAM library, gRNA, and lysate preparation

Cloning the randomized PAM substrate library

CRITICAL: The following library construction steps should be performed for each PAM library. Multiple libraries can be constructed in parallel. The steps are described specifically for the construction of a library harboring a randomized 3’ PAM encoded by the primer oBK1948 (Table 4). Until analysis of the PAM representation within the library (Step 55), the steps are otherwise identical for constructing other libraries bearing different spacers or randomized PAMs on the 5’ end of the spacer (e.g. those encoded by oligos oBK1949, oBK5962, oBK5964, or user-defined oligo designs following the same cloning strategy; Table 4). The following steps include cloning of the randomized PAM libraries, however four ready-to-use libraries are available on Addgene (two spacer sequences each for 3’ and 5’ randomized PAM libraries; Table 3). To skip cloning, proceed directly to NGS validation of the library (Step 29).

-

1.

Cloning the substrate library. Digest approximately 10 μg of the entry cassette plasmid (p11-lacY-wtx1, see Table 2) with EcoRI-HF, SpeI-HF, and SphI-HF for 1-4 hour(s) at 37 °C using the following reaction mix:

Reagent Stock concentration Volume (μL) p11-lacY-wtx1 Variable x CutSmart buffer 10X 4 EcoRI-HF 20,000 units/mL 1 SpeI-HF 20,000 units/mL 1 SphI-HF 20,000 units/mL 1 Nuclease-free water 33-x Total 40 -

2.

CRITICAL STEP: Cloning the library into a plasmid backbone other than p11-lacY-wtx1 with a higher copy origin of replication will improve yield during DNA preparations. If using a different plasmid backbone, adjust oligo design and cloning strategy accordingly. Gel purify the reaction. Run the entire digestion reaction in gel loading dye on a 1% agarose gel with 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide for 45 minutes at 100 V. Excise the backbone from the gel and transfer it to a 1.7 mL tube. Purify the DNA using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (or equivalent) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Elute the solution in 30 μL of nuclease-free water. Quantify the purified plasmid on a NanoDrop and dilute in nuclease-free water to 40 ng/μL.

-

3.

Resuspend the oligos oBK1948 and oBK984 to 100 μM using 0.1X TE and mix them in preparation for annealing in a 0.2 mL tube as follows:

Reagent Stock concentration Volume (μL) Library template oligo (e.g. oBK1948) 100 μM 2 Bottom extension oligo (oBK984) 100 μM 4 STE buffer 10X 3.4 Nuclease-free water 24.6 Total 34 -

4.

Anneal the oligos with the following annealing program in a thermal cycler: 95 °C for 5 min, then decrease 0.1 °C per second for 70 cycles, transfer to 4 °C or ice.

-

5.

After the annealing program completes, add the following reagents to the annealing reaction to make the extension reaction. Mix the solution and incubate the reaction at 37 °C for 30 minutes.

Reagent Stock concentration Volume (μL) Annealing reaction from Step 3 34 Nuclease-free water 8 NEB buffer 2 10x 5 dNTPs 10 mM 2 Klenow Fragment (3’→5’ exo-) 5,000 units/mL 1 Total 48 -

6.

Purify the extension reaction using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (or equivalent kit) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Elute the oligo duplex in 20 μL of nuclease-free water.

-

7.

Digest the oligo duplex with EcoRI-HF for 1-4 hour(s) at 37 °C using the following reaction mix:

Reagent Stock concentration Volume (μL) Purified oligo duplex from Step 6 19 CutSmart buffer 10X 2.2 EcoRI-HF 20,000 units/mL 1 Total 22.2 -

8.

Purify the reaction using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Elute the oligo duplex in 20 μL of nuclease-free water.

-

9.

Determine the concentration of the oligo duplex by nanodrop and dilute to 30 ng/μL.

-

10.

Set up a ligation reaction as follows to ligate the oligo duplex into the EcoRI/SpeI/SphI digested p11-lacY-wtx1 backbone. Prepare the reaction in a 1.7 mL tube, mix, and then aliquot the ligation mix into each well of an 8-strip tube with 50 μL per tube. Incubate the ligation reactions at 16 °C for approximately 16 hours.

Reagent Stock concentration Volume (μL) Digested p11-lacY-wtx1 from Step 2 40 ng/μL 10 Digested oligo duplex from Step 9 30 ng/μL 2.5 T4 ligase buffer 10X 40 T4 DNA ligase 400,000 units/mL 20 Nuclease-free water 327.5 Total 400 -

11.

Pool the ligation reactions and purify the solution using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Elute the ligation in 20 μL of nuclease-free water.

PAUSE POINT: purified ligation reaction(s) can be stored at −20 °C for extended periods of time.

-

12.

Thaw 100 μL of electrocompetent XL1-Blue cells on ice and place three electroporation cuvettes on ice. Three separate electroporations of each library will be performed.

CRITICAL STEP: Keep the electrocompetent cells on ice at all times unless otherwise noted to maximize transformation efficiency.

-

13.

In a 24-well (10 mL per well) block, add 3 mL of SOC medium to three wells and warm the medium to 37 °C.

-

14.

On ice in three separate 1.7 mL tubes, add 5 μL of ligation from Step 11 and 33 μL of electrocompetent cells from Step 12, such that a total of 15 μL of ligation are used across the 100 μL of cells. Mix gently by stirring with the pipette tip.

CRITICAL STEP: Handle the cells gently. Do not pipette up and down to mix.

-

15.

Transfer the cells to the pre-chilled electroporation cuvettes from Step 12. Pipette the mixture gently into the bottom of the cuvettes. Each cuvette should contain a mixture of 5 μL of ligation reaction and 33 μL of electrocompetent cells, for a total of three cuvettes per library. Gently tap the cuvettes so that the cells sit on the bottom of the cuvettes without air bubbles.

-

16.

Electroporate the cells in the Gene Pulser Xcell Microbial System with the following settings.

Parameter Setting Voltage 1.75 kV Capacitance 25 μF Resistance 200 Ω -

17.

Immediately following electroporation, transfer the cells in the cuvettes to 3 mL of pre-warmed SOC medium from Step 13.

CRITICAL STEP: Rapid transfer to SOC medium is critical for transformation efficiency. Electroporate cuvettes one at a time so that the cells can be transferred to SOC medium immediately.

-

18.

Seal the 24-well block with a breathable seal and allow the cells to recover for approximately 1 hour at 37 °C, shaking at 900 RPM.

-

19.

Plate dilutions of the electrotransformation to estimate the complexity of the library. Prepare 10- and 100-fold dilutions of the recovered cells from Step 18 by mixing 10 μL of the recovered cells with 90 μL and 990 μL of SOC medium, respectively. Plate 10 μL of each dilution on a pre-warmed LB agar plate with carbenicillin and incubate the plates at 37 °C for 16 hours. CRITICAL STEP: Library complexity for the full 9 mL culture can be estimated from the number of colonies that grow (see Step 22)

-

20.

After 1 hour of growth in SOC medium, pool the recovered cells for a given library and add the full 9 mL to 150 mL of LB medium with carbenicillin.

-

21.

Grow the culture at 37 °C for approximately 12 hours.

-

22.

After approximately 12 hours, pellet the culture by centrifugation at 2500 x g for 15 minutes and discard the supernatant. PAUSE POINT: The pellets can be stored at −20 °C before proceeding with the protocol.

-

23.

Count colonies from the plated dilutions from Step 19 to estimate the library complexity. The library complexity should exceed 100,000.

Dilution Colonies Library complexity 10 μL of a 10-fold dilution x 9,000*x 10 μL of a 100-fold dilution y 90,000*y -

24.

Prepare the plasmid libraries from the cell pellets from Step 22 with the QIAGEN Plasmid Plus Maxi Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions and quantify the library on a NanoDrop.

-

25.

Linearization of the library. Linearize approximately 10 μg of the plasmid library harboring randomized PAMs by digesting for 4 hours at 37 °C with PvuI-HF. Set up the reaction in a PCR tube as follows:.

Reagent Stock concentration Volume (μL) randomized PAM plasmid library (from Step 24) Variable x CutSmart buffer 10X 4 PvuI-HF 20,000 units/mL 2 Nuclease-free water 34-x Total 40 CRITICAL STEP: Cleavage kinetics can differ dramatically for linear and supercoiled substrates. The reaction conditions for HT-PAMDA are optimized for a linear substrate DNA. We do not recommend using the supercoiled plasmid library as the substrate for HT-PAMDA in vitro cleavage reactions.

-

26.

Purify the reaction with SPRI beads. Add 1.5 volumes of SPRI beads to the reaction, mix by pipetting, incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes, then place the tube on a DynaMag-96 Side Magnet (or other magnetic separator for 96-well plates). Incubate for 5 minutes or until the SPRI beads collect on the side of the tube and the solution is clear. Carefully remove the solution without disturbing the SPRI beads and discard. Wash the beads twice while keeping the tube on the DynaMag-96 Side Magnet. For each wash, add 200 μL of 70% ethanol, incubate for at least 30 seconds, and discard all the ethanol, all without disturbing the SPRI beads. After the second wash, carefully remove any residual ethanol and let the sample dry for about 3 minutes. Remove the tube from the magnet and elute by adding 40 μL of nuclease-free water directly onto the SPRI beads. Pipette to mix. Return the tube to the magnet, allow the beads to separate and transfer the eluate to a new tube, carefully avoiding carrying over SPRI beads.

CRITICAL STEP: The incubation times necessary to separate beads will depend on the magnet strength. Ensure that the solution is clear before proceeding.

CRITICAL STEP: Following the wash steps, do not let the SPRI beads dry longer than about 3 minutes as excessive drying may result in a poor recovery of DNA.

-

27.

Quantify the purified linearized substrate library by nanodrop.

PAUSE POINT: the purified linearized substrate library can be stored at −20 °C for extended periods of time.

-

28.

Run approximately 100 ng of both linearized (Step 27) and circular (Step 24) plasmid on a 1% agarose gel with 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide and visualize the gel under UV light to confirm that the digested plasmid is completely linearized.

-

29.

NGS validation of library. Prepare PCRs to amplify the linearized randomized PAM plasmid libraries with a pair of PCR #1 sample barcoding primers, such as oRW1491 and oRW1501. Include a no-template control PCR.

Reagent Stock concentration Volume (μL) linearized randomized PAM plasmid library (Step 27) 5 nM 1.5 Sample barcoding primer pair (see Reagent setup) 5 μM each 2.5 Q5 buffer 5X 5 dNTPs 10 mM each 0.5 Betaine 5 M 2.5 MgCl2 50 mM 1.5 Q5 polymerase 2,000 units/mL 0.25 Nuclease-free water 11.25 Total (per reaction) 25 -

30.

Run the PCRs with the following program.

Cycle number Denature Anneal Extend 1 98 °C, 2 min 2-31 98 °C, 10 s 67 °C, 10 s 72 °C, 10 s 32 72 °C, 1 min -

31.

Purify the reactions with SPRI beads (as described in Step 26) by adding 1.5 volumes of SPRI beads and eluting in 25 μL of nuclease-free water.

-

32.

Confirm amplification by running the purified reactions on a capillary electrophoresis machine or an agarose gel. For example, PCR products can be analyzed using a QIAxcel Fast Analysis cartridge on the QIAxcel Advanced (Qiagen). For all samples, combine 2 μL of PCR with 8 μL of water in a 96-well PCR plate and run the plate on the QIAxcel with the DM150 program and a 10 second injection time. The sample should have a single band with a size of 206 bp.

-

33.

Quantify the purified reactions on a NanoDrop and prepare a dilution with a concentration of approximately 0.125 ng/μL and a volume of at least 2 μL for use as template in the second PCR. The remainder of the undiluted PCR may be stored at −20 °C for up to a year.

-

34.

Prepare PCRs with a pair of PCR #2 timepoint barcoding primers, such as OJA1933 and OJA1941. Include a no-template control.

Reagent Stock concentration Volume (μL) Template amplicon (from Step 33) 0.125 ng/μL 2 Timepoint barcode primers 5 μM each 2 Q5 buffer 5X 4 dNTPs 10 mM each 0.4 Q5 polymerase 2,000 units/mL 0.2 Nuclease-free water 11.4 Total (per reaction) 20 -

35.

Run the PCRs with the following program.

Cycle number Denature Anneal Extend 1 98 °C, 2 min 2-11 98 °C, 10 s 65 °C, 30 s 72 °C, 30 s 12 72 °C, 5 min -

36.

Purify the reactions with SPRI beads as described in Step 26, adding 1.5 volumes of SPRI beads and eluting in 25 μL of nuclease-free water.

-

37.

Confirm amplification by running the purified reactions on a capillary electrophoresis machine (as described in Step 32) or an agarose gel. The sample should have a single band with a size of 279 bp.

-

38.

Thaw reagents for the Universal KAPA Illumina Library qPCR Quantification Kit (or equivalent) to quantify the library.

CRITICAL STEP: Rox dye is light sensitive. Do not leave the reagent exposed to light for extended periods of time.

CRITICAL STEP: While alternative methods of quantification are acceptable, accurate quantification is essential for determining the appropriate loading concentration for sequencing.

-

39.

Generate 10−5 dilutions of each purified PCR from Step 36 by serial 10-fold dilutions in 1X TE buffer. Conduct serial dilutions by diluting 10 μL of library with 90 μL of TE buffer and mixing well. The remainder of the undiluted PCR may be stored at −20 °C for up to a year.

CRITICAL STEP: Library quantification is dependent on accurate dilution of the pools.

-

40.

Add 1 mL of 10X Illumina Primer Premix to the KAPA PCR master mix and mix (both provided in the Universal KAPA Illumina Library qPCR Quantification Kit).

-

41.

Prepare the following qPCR master solution with enough reagent for triplicate reactions for each experimental sample and standard (6 standards), plus a no-template control. Assemble the reaction on ice.

Reagent Stock concentration Volume (μL) KAPA master mix (primer added) 2X 6 Nuclease-free water 1.8 Rox low 50X 0.2 Total (per reaction) 8 -

42.

In a MicroAmp Optical 96-Well Reaction Plate, aliquot 8 μL of the qPCR master solution into each well as needed.

-

43.

Add 2 μL of template to each well. Perform qPCRs for all experimental samples and standards in triplicate. For samples, use 10−5 dilutions of the purified PCR prepared in Step 39. For standards, use the standards as provided in the qPCR kit, with the concentrations shown below. For a no-template control reaction, add 2 μL of nuclease-free water.

Standard Concentration (pM) 1 20 2 2 3 0.2 4 0.02 5 0.002 6 0.0002 -

44.

Seal the plate tightly with a MicroAmp Optical Adhesive Film, vortex gently, and spin down to ensure that the mixture is at the bottom of the well.

-

45.

Run the following program on an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 qPCR machine (adjusting the settings as required for quantification from a standard curve, rox dye, etc.).

Cycle number Denature Anneal/Extend 1 95 °C, 5 min 2-36 95 °C, 30 s 60 °C, 45 s -

46.

Interpreting qPCR results. Create a standard curve with the 6 triplicate standards. Determine the linear relationship between log10(concentration) and cycle threshold value by linear regression. Use this linear relationship to calculate the concentration of the pools by averaging the triplicates.

CRITICAL STEP: Accurate quantification is critical for ensuring appropriate cluster density during sequencing. For samples and standards, if one replicate is inconsistent with the other two, discard the inconsistent replicate. If no two replicates are in close agreement, repeat the qPCR. If the negative control has a signal that would meaningfully alter the quantification, repeat the qPCR.

-

47.

Prepare an equimolar pool of the PCR from Step 36 based on the qPCR quantification.

-

48.