Abstract

An NMR method to monitor conformational states of challenging large protein targets is described. The method, which can be used to evaluate distances between two labels and to measure conformational exchange rates, revealed an unanticipated outward-facing state in a glutamate transporter.

Proteins are complex machines, dynamically changing their structures to orchestrate essential biological functions1. For large membrane proteins, the toolbox to investigate these structural dynamics is not yet complete. Here, Huang et al.2 present an NMR-based method for examining structural dynamics of large membrane proteins. This method complements existing spectroscopic techniques, fills an important technical gap, and provides new insights into the dynamics of the large glutamate transporter GltPh.

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is providing a tsunami of new membrane protein structures, including structures showing different conformational states3. But these structures are static. More than ever, tools for investigating conformational dynamics are needed to understand the biophysical mechanisms of membrane proteins. Fluorescence and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopies have been invaluable in this respect4,5, but they have limitations. Although both methods are excellent for quantifying distances for labels separated by ~20–80 Å, they can be near useless for shorter distances. To fill this gap, Huang et al. developed an NMR-based method for measuring distances of probes positioned <20 Å apart on membrane proteins. These probes can be used to measure rates of exchange between protein conformations.

NMR is a well-established tool for measuring protein structure and dynamics. However, for large systems, there are substantial challenges imposed by line broadening and spectral overlap. To overcome this challenge, some investigators have adopted the use of fluorine (19F) as a label6,7. Unlike the more standard nuclei (1H, 13C, or 15N), there is no natural occurrence of 19F in proteins, and therefore no background signal. Moreover, the 19F nucleus yields a strong signal that is exquisitely sensitive to its environment, making it an outstanding reporter of protein conformational change. The 19F NMR method developed by Huang et al. takes advantage of this environmental sensitivity to detect different protein conformations and combines it with the strongly distance-dependent effect of paramagnetic ions on NMR signals. The approach uses an elegant orthogonal labeling scheme involving an engineered cysteine modified with a 19F label and a dihistidine moiety that can coordinate a paramagnetic ion. The distance between the two positions is determined by measuring the NMR signal in the presence and absence of a paramagnetic ion.

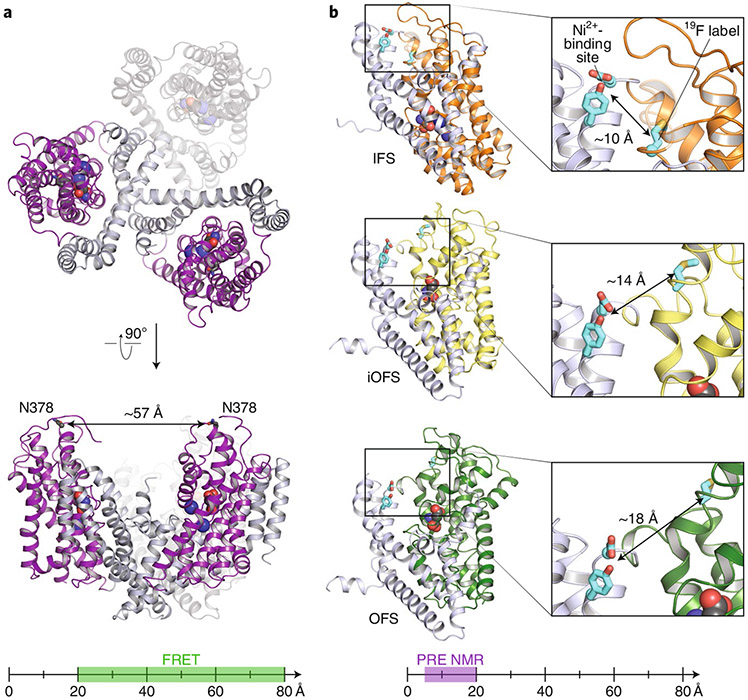

The authors developed this method using the membrane transporter GltPh, a prokaryotic homolog of human glutamate transporters8. As a secondary active transporter, GltPh must operate by ‘alternating access’9, adopting at minimum two conformations: outward facing and inward facing. High-resolution structures of GltPh’s outward- and inward-facing states (OFS and IFS, respectively) are available, and transitions between them have been studied using EPR and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). GltPh is a homotrimer, with each subunit acting as an independent unit within the trimer. With subunits that are ~30 Å in diameter, an optimal FRET signal requires labeling on different subunits (Fig. 1a). By contrast, the ability of NMR paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) to measure distances in the <20 Å range allows design of probes within the functional unit (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1 ∣. 19F PRE NMR as a complement to FRET for evaluating conformational states.

a, Top: view of the GltPh homotrimer from the extracellular side. The scaffold domains are shown in grey and the transport domains in purple. Substrate aspartate and Na+ are shown in spacefill. Bottom: Side view of two GltPh subunits, indicating one of the labeling positions used in FRET studies. The ruler below indicates the distances between probes suitable for FRET measurements. b, Structures of the three GltPh conformational states observed in this NMR study (PDB IDs 3V8G, 6UWL, and 6UWF for the IFS, iOFS, and OFS, respectively). In the right are expanded views of the labeling positions. (Here, wild-type residues are shown; in the NMR study, residues were mutated to histidine or cysteine to generate the Ni2+-binding or 19F-labeling site, respectively.) The ruler below indicates the distances between probe sites that can be measured PRE NMR.

Based on the previous studies of GltPh, the authors anticipated that a single 19F label on GltPh would generate two NMR signals, representing the different chemical environments of the probe when the transporter adopts the OFS versus the IFS conformation. Instead, they saw three separate and distinct signals! Through PRE distance measurements, complemented by molecular dynamics simulations, they assigned one of the signals to the IFS and the other two to distinct OFS conformations. Motivated by this observation, the authors used cryo-EM to determine two structures, one indistinguishable from the known OFS and the second an ‘intermediate OFS (iOFS) (Fig. 1b). While this intermediate state had previously been observed in the crystal structure of a GltPh mutant (PDB ID 3V8G), the unusual crystal packing left uncertainty as to whether such a conformation could be adopted by the native protein. With this uncertainty allayed, the functional significance of the iOFS warrants further exploration.

The authors further used NMR to measure the exchange rate between different protein conformations. Over the past decades, a variety of clever NMR-based approaches have been developed to study protein conformational dynamics on timescales spanning several orders of magnitude10. Here, Huang et al. add their 19F paramagnetic relaxation-based method to this powerful toolkit. Using GltPh mutants known to undergo conformational exchange more rapidly than the wild-type transporter, they demonstrate that their method can evaluate exchange between the IFS and OFS conformations. This new approach will be of value in studying other membrane proteins that undergo conformational exchange on the subsecond-to-second timescale. Advantages of this method include its rapidity and its suitability to large proteins.

Overall, these results showcase the versatility of NMR as a probe of structure and dynamics. This new method is applicable to a wide range of membrane proteins and should galvanize more researchers to use NMR to identify conformational heterogeneity in protein preparations, to screen for conditions that modulate conformational equilibria, and to monitor protein conformational exchange. For those studying glutamate transporters, the identification of the GltPh iOFS motivates future kinetic experiments to understand how conformational states are connected. Ultimately, the continued leveraging of complementary approaches will enable a complete understanding of how GltPh protein conformational dynamics are coordinated to achieve secondary active transport.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Henzler-Wildman K & Kern D Nature 450,964–972 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Y et al. Nat. Chem. Biol 10.1038/s41589-020-0561-6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng Y Science 361,876–880 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahu ID & Lorigan GA Biomolecules 10, 763–788 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazal H & Haran G Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng 12, 8–17 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Di Pietrantonio C, Pandey A, Gould J, Hasabnis A & Prosser RS Methods Enzymol. 615, 103–130 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose-Sperling D, Tran MA, Lauth LM, Goretzki B & Hellmich UA Biol. Chem 400, 1277–1288 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavić A, Holmes AOM, Postis VLG & Goldman A Biochem. Soc. Trans 47,1197–1207 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanford C Annu. Rev. Biochem 52, 379–409 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sekhar A & Kay LE Annu. Rev. Biophys 48, 297–319 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]